Abstract

Background

As many people relied on information from the Internet for official scientific or academically affiliated information during the COVID‐19 pandemic, the quality of information on those websites should be good.

Objective

The main purpose of this study was to evaluate a selection of COVID‐19‐related websites for the quality of health information provided.

Method

Using Google and Yahoo, 36 English language websites were selected, in accordance with the inclusion criteria. The two tools were selected for evaluation were the Health on the Net (HON) Code and the 16‐item DISCERN tool.

Results

Most websites (39%) were related to information for the public, and a small number of them (3%) concerned screening websites in which people could be informed of their possible condition by entering their symptoms. The result of the evaluation by the HON tool showed that most websites were reliable (53%), and 44% of them were very reliable. Based on the assessment results of the Likert‐based 16‐item DISCERN tool, the maximum and minimum values for the average scores of each website were calculated as 2.44 and 4.25, respectively.

Conclusion

Evaluation using two widely accepted tools shows that most websites related to COVID‐19 are reliable and useful for physicians, researchers and the public.

Keywords: content analysis, evaluation, pandemic, patient information, web sites

Key Messages.

Both the Health on the Net and 16‐item DISCERN website evaluation tools gave comparable findings for the quality of information provided by scientific/institutional COVID‐19 websites.

COVID‐19 websites provide a variety of functions: information about the progress of the pandemic, symptom screening, public information and information about research projects and trials.

The scientific/institutional COVID‐19 websites were generally reliable sources for a variety of audiences.

INTRODUCTION

Followed by the emergence of the Internet and the World Wide Web, the world is faced with various websites which are related to health information (Khachfe et al., 2021). The Internet has currently become an essential source of health information because of the revolution in the Information, Communications and Technologies domain. By searching diverse health‐related websites and blogs, every kind of information is now accessible by clicking on different buttons (Halboub et al., 2021). Therefore, many patients incline to browse websites to clarify their health‐related concerns, even before consulting with general physicians or specialists (Caria et al., 2020). The web is not responsible for its content, so controlling its information in this regard is not possible; hence, the growth of websites does not guarantee their information quality (Clarke et al., 2016; Gürtin & Tiemann, 2021). Some of the information available on the websites is not only useless, but may also be inaccurate or misleading (Chen et al., 2018; Misra et al., 2021). Trusting online health information has lately been a matter of great importance due to insufficiencies in people's ability to judge the quality of this information (Seven et al., 2021). Significantly, the presence of incorrect information on medical websites seems more worrying, as many users may use the Internet as a source of information for themselves, and their family and friends (El Sherif et al., 2018). This is especially important when facing unknown and dangerous diseases like the current pandemic of COVID‐19. Recently, a new series of Coronavirus (COVID‐19) was identified in Wuhan, China, in 2019 (Paul et al., 2020); the prevalence of this unknown type of Coronavirus that has not been found in human beings before, has been increasing dramatically (Mohammadzadeh et al., 2020; Paul et al., 2020). According to the latest figures from the world meter databases, 491,826,957 people have been infected with COVID‐19 worldwide (Lu et al., 2020). Given the conditions associated with the breakdown of COVID‐19, people should have access to accurate and reliable information on the nature of COVID‐19 (Al‐Benna & Gohritz, 2020). As well, most countries, governments and academic organisations have made helpful information and knowledge available to the public through websites in this situation (Cuan‐Baltazar et al., 2020; Valizadeh‐Haghi et al., 2017). People's awareness of the latest news in the countries, the way that the disease is transmitted between individuals, its treatment options, and its diagnosis in different phases are known as fundamental issues; therefore, online access to accurate and valuable information is essential (Forbat et al., 2018; Sumner et al., 2020). The available information on COVID‐19 should be understandable, and it must be easier to comprehend by the public without applying any special unclear terminologies or vocabularies. The quality and accuracy of such information can widely vary, and there is a demand for using tools capable of objectively evaluating and filtering the content of COVID‐19‐related websites. Therefore, considering that different websites have been launched worldwide to increase public awareness of the COVID‐19 pandemic, there is a need to evaluate and investigate these COVID‐19‐related websites with reliable tools (Abdekhoda et al., 2022). Therefore, our study's main objective was to evaluate the quality of provided health information on websites about COVID‐19. Thus, the specific aims of this paper were the followings: (1) selection of COVID‐19‐related websites, (2) selection of appropriate tools for evaluation and (3) evaluation of the included websites using the selected tools.

METHODS

Search strategy

This cross‐sectional study was performed on 7 February 2021. In the first phase, we searched some databases, including Medline (through PubMed), Scopus and Google scholar by the following keyword: ‘website evaluation tool’. The purpose of this review was to identify practical tools for evaluating websites. In this phase, the evaluation tools were identified based on our reviewed studies, and then Health on the Net (HON) Code for health‐related websites and the 16‐items DISCERN tool were selected. Meanwhile, convenience sampling was used to obtain a sample of websites reflected in the range of information provided on COVID‐19 disease. In the second phase, we searched the two most popular search engines, including Google and Yahoo. We searched ‘COVID‐19 disease’ in each one of these search engines: Google.com (four separate searches with preferences set to Iran), and Yahoo.com. ‘COVID‐19 disease’ is a term commonly used by people in their website searches. Of note, most people mainly tend to browse search results presented on the first pages (Yi et al., 2012). Therefore, we expected that websites appearing on the first pages of the search results would be more relevant compared to those presented on the last pages. The 10 pages from each search engine were browsed within 24 h to avoid any changes. Consequently, the first 100 consecutive websites identified from each engine were browsed by the ‘COVID‐19 disease’ keyword.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for selecting websites

At this stage, first, the duplicate websites were omitted. Thereafter, only English‐language websites were entered into our study. Some websites were excluded from the study; those websites that had non‐functional or inactive links and required a subscription to access the content. Moreover, discussion forums, articles, blogs or scholarly journals were excluded. The research team decided to evaluate only organisational or academically affiliated websites. So, the included websites were entirely dedicated to COVID‐19 disease, affiliated to scientific or academic institutions, and approved by scientific institutes. Because COVID‐19 has an unknown identity and may cause severe problems for people worldwide, we decided to evaluate those websites affiliated with reputable institutions. It is noteworthy that users living all around the world prefer to obtain their required information from those websites affiliated to scientific, governmental and reputable institutions. One of the main reasons for restricting websites was that people often sought information from reputable sites during the time of the new Coronavirus pandemic, especially in 2 years from the beginning of the breakdown. Fake and misleading information was often seen on unscientific websites, which misled people. Relying on this misinformation and unscientific basis also increased people's stress and encouraged them to act not in accordance with scientific findings.

Website screening

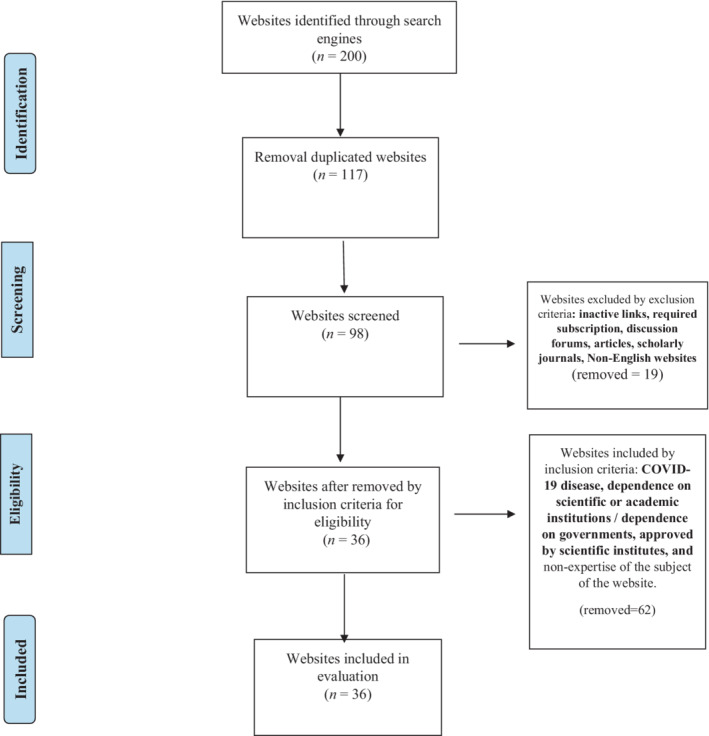

Four reviewers (SR, MG, SS and MT) independently searched and screened the websites for inclusion in February 2021. Websites were included if four reviewers agreed on their inclusion, and any conflict or uncertainty, it was resolved by discussing and involving a fifth reviewer (RS). In the last phase, 36 websites remained as eligible items. Researchers independently explored and then screened the websites. Figure 1 displays the diagram of selecting the eligible websites in terms of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Therefore, 36 websites were first identified and then analysed based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligible and selected websites were recorded for further assessments, and the selected websites evaluated for quality assessment in the study (arranged in alphabetical order) are presented below:

https://www.cms.gov/outreach-education/partner-resources/coronavirus-covid-19-partner-resources

https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert

https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus

https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/03/06/905436/best-worst-coronavirus-dashboards/

FIGURE 1.

Diagram for the screening and selecting websites

Selecting the proper evaluation tool

The HON certification and DISCERN tool (http://www.discern.org.uk), which were designed to be applied by consumers of online health information without requiring any previous knowledge of the subject, were selected (based on the literature review and expert consultation) as the validated tools in order to evaluate the quality of the included websites related to COVID‐19 disease. HON is a non‐profit foundation with the aim of assessing and evaluating the transparency and quality of web‐based health information. HON includes the following eight criteria: complementarity, confidentiality, authority, financial disclosure, attribution, transparency, justifiability and advertising policy (Portillo et al., 2021). In previous studies, the HON tool was used to assess and evaluate health‐related websites. Correspondingly, this tool is a beneficial scale that offers health information with high quality. It demonstrates the intent of a website to publish transparent information (Flint et al., 2021; Jasem et al., 2022; Smekal et al., 2019; St John et al., 2021).

The meaning of each component in HON is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

HON components description

| HON principles concept | Questions |

|---|---|

| Authority |

First question. Medical or health advice provided and hosted on the site will be given only by medically trained and qualified professionals unless a clear statement is made that a piece of advice offered is from a medically qualified individual or organisation. |

| Attribution |

Second question and Third question. When appropriate, information contained on the site will be supported by clear references to source data and, when possible, have specific HyperText Markup Language (HTML) links to those data. The data when a clinical page was last modified will be clearly displayed. (References given, Last modified date provided.) |

| Complementarity |

Fourth question and Fifth question. Information provided on the site is designed to support, not replace, the relationship that exists between a patient/site visitor and his or her existing physician. |

| Transparency of sponsorship |

Sixth question. Support for this website will be clearly identified, including the identities of commercial and noncommercial organisations that have contributed funding, services, or material for the site. |

| Honesty in advertising and editorial policy |

Seventh question. If advertising is a source of funding, it will be clearly stated. A brief description of the advertising policy adopted by the website owners will be displayed on the site. |

| Justifiability |

Eighth question and Ninth question. Any claims relating to the benefits/performance of a specific treatment, commercial product, or service will be supported by appropriate, balanced evidence in the manner. |

| Confidentiality |

Tenth question. Confidentiality of data relating to individual patients and visitors to a medical/health website, including their identity, is respected by this Web site. The Web site owners undertake to honour or exceed the legal requirements of medical/health information privacy that apply in the country and state where the website and mirror sites are located. |

| Transparency of authorship |

Eleventh question. The designers of this website will seek to provide information in the clearest possible manner and provide contact addresses for visitors who seek further information or support. The webmaster will display his/her E‐mail address clearly throughout the website. |

| All of the principles met | Twelfth question. |

Abbreviation: HON, Health on the Net.

For performing the evaluation, after answering various HON questions on the level of origin and transparency of the selected websites, a percentage was gained related to the level of satisfaction of principles and components (automatically by the HON tool). The HON tool helps evaluators in assessing the transparency, credibility and the quality of a health‐related website by guiding them to ask questions related to the HON code ideologies (Fullard et al., 2021; Moore & Harrison, 2018; Raj et al., 2016). The DISCERN tool is a 16‐item questionnaire applied to assess the quality of health information on a website and helps healthcare providers and consumers to evaluate any website containing health information. Each question is scored on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (‘very poor’, ‘poor’, ‘fair’, ‘good’, or ‘excellent’). In this regard, a higher score (score = 5: Excellent) indicated that the website comprises more valuable and appropriate information, while a lower score (score = 1: very poor) shows a lack of information in the identified categories. DISCERN is an instrument or tool designed to help users of consumer health information judging the quality of written information on various websites. This tool is the first standardised quality index of consumer health information that can be used by producers, health professionals and patients to appraise written information on the available treatment choices. There are different studies in which the DISCERN tool has been used to assess many health‐related websites (Alpaydın et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Misra et al., 2021; Portillo et al., 2021; Venosa et al., 2021). In the assessment phase, four authors (SR, SS, MT and MG) analysed and evaluated the websites independently, and then they extracted the rate of each component. The next evaluator (RS) validated all the obtained results in a focus group negotiation.

RESULTS

Among 200 results obtained from our searches, 36 websites met our inclusion criteria, so they were evaluated. The included websites and their characteristics are listed in Table 2. In this table, website name, address, type and custodian are presented. In addition, the HON principles for websites, the website's sponsorship and the average score of each website by the DISCERN tool are shown in Table 3. Considering that the websites were evaluated by four voters and each principle was examined in the HON, the final evaluation was performed by the study supervisor (RS) in a focus group and negotiation based on four evaluators' answers and the last value was placed in Table 3. In fact, using the HON tool, each component or principle is answered with two options, ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. Any website that meets a principle obtains the answer ‘Yes’, and if it does not follow the principle, the answer is ‘No’.

TABLE 2.

The characteristics of evaluated websites

| # | Website name | Website address | Website type | Website custodian |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | COVID‐19 Screening Tool | https://cv.nmhealth.org/ | More than one | New Mexico Department of Health |

| 2 | Self‐Assessment Tool (British Columbia) | https://bc.thrive.health/covid19/en | Screening website | British Columbia Ministry of Health |

| 3 | COVID‐19 Tracker | https://bing.com/covid/local | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | Microsoft Bing team |

| 4 | Government of Canada | https://www.canada.ca/en/institutes‐health‐research/news/2020/03/government‐of‐canada‐funds‐49‐additional‐covid‐19‐research‐projects‐details‐of‐the‐funded‐projects.html | Project Informative websites | Canadian Institutes of Health Research |

| 5 | Coronavirus (COVID‐19) | https://www.coronavirus.gov/ | More than one | CDC and FEMA |

| 6 | COVID‐19 Projections | https://covid19.healthdata.org/italy | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | IHME‐University of Washington |

| 7 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) | https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/cases‐in‐us.html | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | CDC |

| 8 | WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) Dashboard | https://covid19.who.int/ | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | WHO |

| 9 | The EGI call for COVID‐19 research projects is now open | https://www.egi.eu/egi‐call‐for‐covid‐19‐research‐projects/ | Project Informative websites | EGI |

| 10 | COVID‐19 Information and Updates | https://www.usa.gov/coronavirus | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | USA Gov |

| 11 | Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Information and Updates | https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/coronavirus | More than one | The Johns Hopkins University/Hospital/Health System Corporation |

| 12 | Mental health and wellbeing during the Coronavirus COVID‐19 outbreak | https://www.lifeline.org.au/get‐help/topics/mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐during‐the‐coronavirus‐covid‐19‐outbreak | Public information | Lifeline Australia |

| 13 | COVID‐19 | https://www.mayoclinic.org/coronavirus‐covid‐19 | More than one | Mayo Clinic |

| 14 | Coronavirus (COVID‐19) | https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus‐covid‐19/ | More than one | NHS |

| 15 | Ottawa Public Health | https://www.ottawapublichealth.ca/en/index.aspx | Public information | Ottawa Public Health |

| 16 | COVID‐19 Research Projects | https://www.phpc.cam.ac.uk/covid‐19‐research‐projects/ | Project Informative websites | University of Cambridge |

| 17 | COVID‐19 funding opportunities | https://reacting.inserm.fr/covid‐19‐funding‐opportunities/ | Project Informative websites | Reacting – Inserm |

| 18 | COVID‐19 Open Research Dataset | https://www.semanticscholar.org/cord19 | Project Informative websites | Semantic Scholar and Allen Institute for AI |

| 19 | The best, and the worst, of the coronavirus dashboards | https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/03/06/905436/best‐worst‐coronavirus‐dashboards/ | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | MIT Technology Review |

| 20 | UNICEF for every child | https://www.unicef.org/results | Public information | UNICEF |

| 21 | Coronavirus (COVID‐19) | https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/coronavirus.aspx | Public information | University of Rochester Medical Center |

| 22 | COVID‐19 Coronavirus Pandemic | https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | Worldometers |

| 23 | Global research on coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) | https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/global‐research‐on‐novel‐coronavirus‐2019‐ncov | More than one | WHO |

| 24 | Team Kentucky | https://govstatus.egov.com/kycovid19 | More than one | Kentucky public health |

| 25 | Nextstrain | https://nextstrain.org/ | Screening website | Multiple health institutions |

| 26 | WebMD | https://www.webmd.com/coronavirus | More than one | Health Organisation |

| 27 | ASCO | https://www.asco.org/asco‐coronavirus‐information | Public information | ASCO |

| 28 | Ministry of Health | https://www.health.govt.nz/our‐work/diseases‐and‐conditions/covid‐19‐novel‐coronavirus | Public information | The Ministry of Manatu Hauora |

| 29 | Gov.UK | https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus | More than one | UK government |

| 30 | Coronavirus (COVID‐19) | https://www.australia.gov.au/ | Public information | Australian government |

| 31 | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control | https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/COVID‐19/national‐sources | More than one | An agency of the European Union |

| 32 | Coronavirus (COVID‐19) health alert | https://www.health.gov.au/news/health‐alerts/novel‐coronavirus‐2019‐ncov‐health‐alert | More than one | Australian government |

| 33 | COVID‐19 | https://www.nsw.gov.au/covid‐19 | More than one | NSW government |

| 34 | COVID‐19 | https://www.cms.gov/outreach‐education/partner‐resources/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐partner‐resources | Public information | CMS |

| 35 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) | https://dshs.state.tx.us/coronavirus/ | Public information | DSHS |

| 36 | Coronavirus (COVID‐19) | https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/coronavirus | Public information | Victoria State government |

Abbreviations: ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CMS, The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; DSHS, The Texas Department of State Health Services; FEMA, Federal Emergency Management Agency; IHME, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; MIT, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; NHS, National Health Service; UNICEF, United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund; WHO, World Health Organisation.

TABLE 3.

Websites with satisfied HON principle and mean scores (each website) for DISCERN tool by raters

| HON principles for websites (the URL of websites) | Website sponsorship | Type of website | Website audience | Question 1 (authority) | Question 2 (attribution) | Question 3 (attribution) | Question 4 (complementarity) | Question 5 (complementarity) | Question 6 (transparency) | Question 7 (honesty) | Question 8 (justifiability) | Question 9 (justifiability) | Question 10 (confidentiality) | Question 11 (transparency of authorship) | Mean scores of DISCERN tool assessment by raters | Quality based on HON and DISCERN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/03/06/905436/best‐worst‐coronavirus‐dashboards/ | Healthcare organisation | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3.312 | Acceptable |

| https://bing.com/covid/local/iran | Government | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | Public | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2.101 | Weak |

| https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ | Healthcare organisation | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | 3.010 | Acceptable |

| https://covid19.healthdata.org/italy | Government | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3.563 | Acceptable |

| https://covid19.who.int/ | Healthcare organisation | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2.937 | Weak |

| https://www.usa.gov/coronavirus | Government | Informative dashboard (Epidemic meter) | Public | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | 2.401 | Weak |

| https://www.phpc.cam.ac.uk/covid‐19‐research‐projects/ | Government and Education | Project Informative websites | Researcher | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 2.126 | Weak |

| https://reacting.inserm.fr/covid‐19‐funding‐opportunities/ | Government and Education | Project Informative websites | Researcher | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2.250 | Weak |

| https://www.egi.eu/egi‐call‐for‐covid‐19‐research‐projects/ | Government and Education | Project Informative websites | Researcher | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2.213 | Weak |

| https://www.canada.ca/en/institutes‐health‐research/news/2020/03/government‐of‐canada‐funds‐49‐additional‐covid‐19‐research‐projects‐details‐of‐the‐funded‐projects.html | Government and Education | Project Informative websites | Researcher | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 2.942 | Weak |

| https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/coronavirus.aspx | Education | Public information | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.250 | Good |

| https://www.ottawapublichealth.ca/en/index.aspx | Government and Education | Public information | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 4.250 | Good |

| https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/coronavirus/ | Education | Public information | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.312 | Good |

| https://bc.thrive.health/covid19/en | Government | Screening website | Public | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3.310 | Acceptable |

| https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus‐covid‐19/ | Government | Public information | Public | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3.187 | Acceptable |

| https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/cases‐updates/cases‐in‐us.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/cases‐in‐us.html | Healthcare organisation | Public information | Public | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3.125 | Acceptable |

| https://www.semanticscholar.org/cord19 | Education | Project Informative websites | Researcher | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3.827 | Acceptable |

| https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/covid‐19 | Government | Public information | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.125 | Good |

| https://cv.nmhealth.org/ | Health care organisation | Screening, Public websites | Public | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3.184 | Acceptable |

| https://www.coronavirus.gov/ | Health care organisation | Informative dashboard, Screening, Public website | Public, Researcher, Clinician | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.628 | Good |

| https://www.mayoclinic.org/coronavirus‐covid‐19 | Government and Education | Screening, Public websites | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.437 | Good |

| https://www.lifeline.org.au/get‐help/topics/mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐during‐the‐coronavirus‐covid‐19‐outbreak | Government | Public information | Public | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3.062 | Acceptable |

| https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/global‐research‐on‐novel‐coronavirus‐2019‐ncov | Healthcare organisation | Informative dashboard, Public, Project informative websites | Public, Researcher, Clinician | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.187 | Good |

| https://govstatus.egov.com/kycovid19 | Health care organisation | Informative dashboard, Screening, Public website | Public, Researcher, Clinician | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3.437 | Acceptable |

| https://nextstrain.org/ | Healthcare organisation | Screening website | Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.500 | Good |

| https://www.webmd.com/coronavirus | Healthcare organisation | Informative dashboard, Screening, Public website | Public, Researcher, Clinician | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3.994 | Acceptable |

| https://www.asco.org/asco‐coronavirus‐information | Healthcare organisation | Public information | Researcher, Clinician | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.437 | Good |

| https://www.health.govt.nz/our‐work/diseases‐and‐conditions/covid‐19‐novel‐coronavirus | Government | Public information | Public, Clinician | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.250 | Good |

| https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus | Government | Informative dashboard, Public websites | Public, Researcher | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2.312 | Weak |

| https://www.australia.gov.au/ | Government | Public information | Public | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3.187 | Acceptable |

| https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/COVID‐19/national‐sources | Healthcare organisation | Informative dashboard, Public, Project informative websites | Researcher, Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.562 | Good |

| https://www.health.gov.au/news/health‐alerts/novel‐coronavirus‐2019‐ncov‐health‐alert | Government | Informative dashboard, Public websites | Clinician, Public | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.312 | Good |

| https://www.nsw.gov.au/covid‐19 | Government | Informative dashboard, Screening, Project informative websites | Public | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.750 | Good |

| https://www.cms.gov/outreach‐education/partner‐resources/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐partner‐resources | Healthcare organisation | Public information | Researcher, Clinician | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 3.437 | Acceptable |

| https://dshs.state.tx.us/coronavirus/ | Government | Public information | Public, Researcher, Clinician | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3.998 | Acceptable |

| https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/coronavirus | Government | Public information | Public, Researcher, Clinician | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3.900 | Acceptable |

Abbreviation: HON, Health on the Net.

However, the maximum and minimum values for the average scores of each website were calculated as 2.101 and 4.750 based on the Likert‐based 16‐item DISCERN tool's assessment results, respectively (IQR1: 3.010, IQR2: 3.5, IQR: 4.25). Remarkably, of the 36 websites surveyed in this study, 15 (41.66%) had scores above 3 (an overall quality of the source of information is acceptable), and eight (22.22%) had scores below 3, all of which ranged from 2 to 3 (an overall quality of the source of information is weak). Moreover, 13 websites (36.11%) had an average score above 4, the quality of which was assessed as good.

According to the results presented in Table 3, it can be seen that the results related to the evaluation of the two tools, namely HON and DISCERN, are in line with each other. That is, the high quality of the evaluation of a website that we achieved using the tool HON can be considered as a reason for the high quality of the evaluation of the same website using the tool DISCERN. For example, in HON tool, websites that satisfied two or three components with a ‘No’ answer and the rest of the components with a ‘Yes’ answer were of ‘acceptable’ quality. In addition, according to the results of the DISCERN tool, the average evaluation scores of the same websites were between 3 and 4, indicating the ‘acceptable’ quality of these websites.

As well, websites that had 4 to 11 evaluation components with the answer ‘No’ for the HON tool and a small number of components that had the answer ‘Yes’ were evaluated as ‘weak’ quality; according to the results of the DISCERN tool, the average evaluation scores of the same websites was less than 3 or close to 2, which indicated the ‘weak’ quality of the websites.

Finally, for the HON tool, websites with only one evaluation component with a ‘No’ answer and the other components that answered ‘Yes’ obtained a ‘good’ ranking in terms of quality. In addition, according to the results of the DISCERN tool, the average evaluation scores of the same websites were above 4, which indicated their ‘good’ quality.

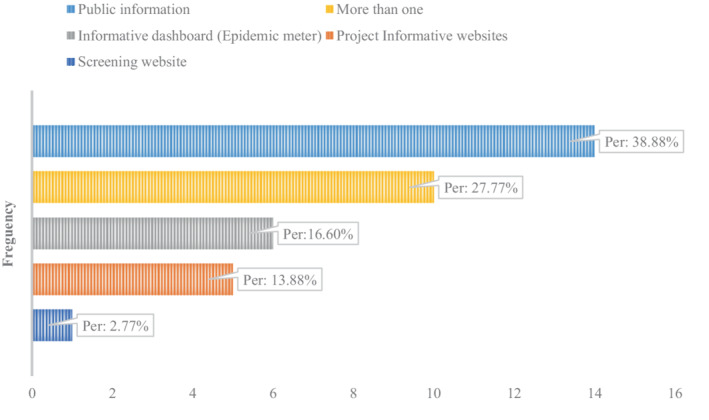

The distribution of websites based on their type

In this study, we classified the websites according to their type in the following four categories; in fact, these categories were developed by the research team: 1 – Informative dashboards (Epidemic Meters), 2 – Screening websites, 3 – Public information websites and 4 – Project informative websites. Correspondingly, informative dashboards mean that these websites represent the summarised and analysed information on statistics related to COVID‐19 disease such as the numbers of Coronavirus cases, recovered cases, and death based on country, daily new cases or death. They also provide some visualised graphs about its epidemiologic parameters like the severity of prevalence in different areas. Screening websites presented some questions that must be answered by users about their health status. Thereafter, according to the users' answers, these websites provided helpful guides and recommendations about self‐care or the necessity of making self‐isolation or referring to an emergency department or general practitioner. Public information websites are considered as websites giving some information on COVID‐19 for the public to better deal with the current epidemic, including reducing stress, how to treat a Coronavirus patient, managing wellbeing, helping children and maintaining a different level of social distance like quarantine, self‐isolation or physical distance. Project informative websites declare governmental, organisational and university project calls and funds for researching COVID‐19 projects. Moreover, they provide helpful information for researchers, including exciting topics, guidelines for preparing a proposal for the applicant institute and some important dates like a deadline for sending their proposal. The reviewed websites based on their type are presented in Figure 2. It was concluded that most websites (38.88%) were related to public information, and the lowest percentage of them (2.77%) were screening websites.

FIGURE 2.

The distribution of websites based on their type

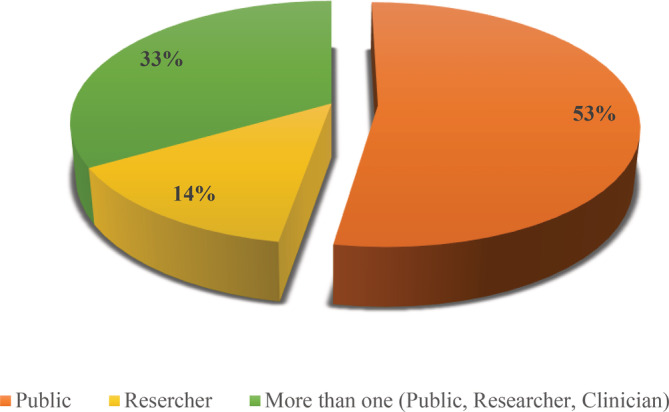

The distribution of websites based on their audience groups

The websites' audiences were three groups of people as follows: Researchers, Clinicians and the Public (Figure 3). Most of the website's audience, as 53%, was the public. None of the websites were created exclusively for clinicians. Of note, 33% of websites had more than one audience and met all the audiences' needs in terms of COVID‐19 disease.

FIGURE 3.

The distribution of websites based on their audience groups

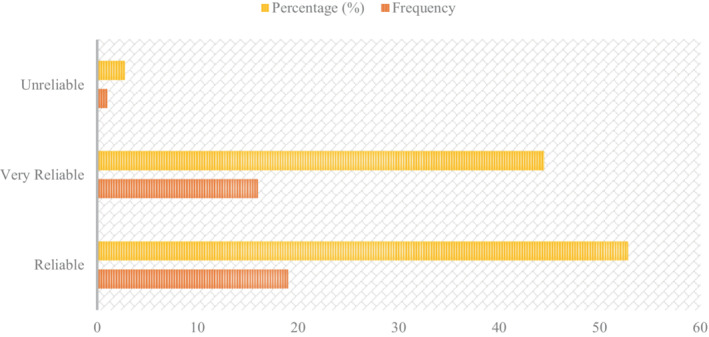

The reliability level of the evaluated websites

There are three main sections in the HON evaluation standard form (https://www.hon.ch/HONsearch/Patients/honselect.html), including ‘quality of the website content production’, ‘ethics’ and ‘reliability’. The ‘reliability’ section in the HON evaluation form is completed based on the general opinions of the evaluators and the answers to main principles (previous sections). Therefore, the reliability of the included websites was assessed based on the ‘opinion’ of each evaluator (Figure 4). Accordingly, reliable websites are transparent about their sources and help the reader gain a deeper understanding of the topic. The reliability of web content is estimated based on the combined scores obtained from three categories included in the HON evaluation tool; this combination of scores is finally used to estimate the level of reliability. Reliability assessment based on this tool means the degrees of reliability and relevance from the perspective of evaluators or experts. However, based on a general conclusion attained from previous questions (quality of the website content production and ethics), how trustworthy are the websites from the viewpoint of evaluators? Consequently, in this study, based on the evaluators' opinions, most websites were found to be reliable (52.77%), and 44.44% of them were very reliable. As shown in Figure 3, the contents of most websites were found to be suitable for the targeted audience.

FIGURE 4.

The reliability level of evaluated websites

Level of adherence to the HON principles by the websites

The websites of COVID‐19 were assessed in terms of the HON principles. Five of the websites met all the HON principles (Table 4). Among 36 COVID‐19 websites, all of them met the HON question, as ‘adhering to the site's mission’ (36 COVID‐19 websites; 100%). Additionally, 32 COVID‐19 websites (88.88%) were evaluated as suitable websites for their targeted audience (the website contents suit the targeted audience or not?). The principle of ‘Reference given’ was met by 52.77% (n = 19) of the websites, and the principle of ‘Providing information on the treatments, medications and diets’, was met by 47.22% of the websites (n = 17).

TABLE 4.

Level of conforming HON principles by evaluated websites

| HON principles | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Authority | 24 (66.66) |

| Attribution | |

| Reference given | 19 (52.77) |

| Last modified date provided | 27 (75) |

| Complementarity | |

| Information about treatments, medications, diets provided | 17 (47.22) |

| Issues supported by scientific knowledge | 33 (91.66) |

| Justifiability | |

| Site's mission supplied | 36 (100) |

| Suited for the targeted audience | 32 (88.88) |

| Transparency of authorship | 29 (80.55) |

| Transparency of sponsorship | 31 (86.11) |

| Honesty in advertising and editorial policy | 26 (72.22) |

| Confidentiality | 22 (61.11) |

| All of the principles met | 5 (13.88) |

Abbreviation: HON, Health on the Net.

Percent of the HON evaluation

The percent of the HON evaluation are shown in Table 5. The percentages obtained for each website are displayed online by the HON tool. In fact, after evaluating the website in the address (https://www.hon.ch/HONcode/Patients/HealthEvaluationTool.html), based on the evaluator's answers, the percentage was displayed online for the quality of the website. As shown in this table, of the COVID‐19 websites, eight websites had an evaluation percent between 50% and 70% with ‘weak’ quality. The evaluation result of the HON was 91%–100% for thirteen websites, so these websites have ‘good’ quality. However, DISCERN tool evaluation result for each question (16 questions) is presented in Table 6. As shown, ‘Is it relevant’ and ‘Is it balanced and unbiased?’ questions have the maximum average scores among 16 items for 36 websites; ‘Does it describe the risks of each treatment?’ question had the minimum mean score. The results show that some websites were excellent in communicating Coronavirus‐related health information; nevertheless, they obtained lower scores in terms of the treatment effect and the treatment options. The quality of information on COVID‐19 medication choices and treatment effects was consistently rated as low by four raters.

TABLE 5.

Percent of the HON evaluation

| HON evaluation range | n (%) | Quality |

|---|---|---|

| 50%–70% | 8 (22.22%) | Weak |

| 71%–90% | 15 (41.66) | Acceptable |

| 91%–100% | 13 (36.11%) | Good |

Abbreviation: HON, Health on the Net.

TABLE 6.

DISCERN tool evaluation results by each question (16‐item)

| DISCERN tool questions | Mean scores for total websites (n = 36) |

|---|---|

| Are the aims clear? | 4.2 |

| Does it achieve its aims? | 4 |

| Is it relevant? | 4.5 |

| Is it clear what sources of information were used to compile the publication | 4 |

| Is it clear when the information used or reported in the publication was produced? | 3.5 |

| Is it balanced and unbiased? | 4.5 |

| Does it provide details of additional sources of support and information? | 3.5 |

| Does it refer to areas of uncertainty? | 3 |

| Does it describe how each treatment works? | 3.5 |

| Does it describe the benefits of each treatment? | 3.5 |

| Does it describe the risks of each treatment? | 2.5 |

| Does it describe what would happen if no treatment is used? | 3 |

| Does it describe how the treatment choices affect overall quality of life? | 3.5 |

| Is it clear that there may be more than one possible treatment choice? | 3 |

| Does it provide support for shared decision‐making? | 3.5 |

| Based on the answers to all of the above questions, rate the overall quality of the publication as a source of information about treatment choices | 3.5 |

Distribution of websites based on their sponsorship

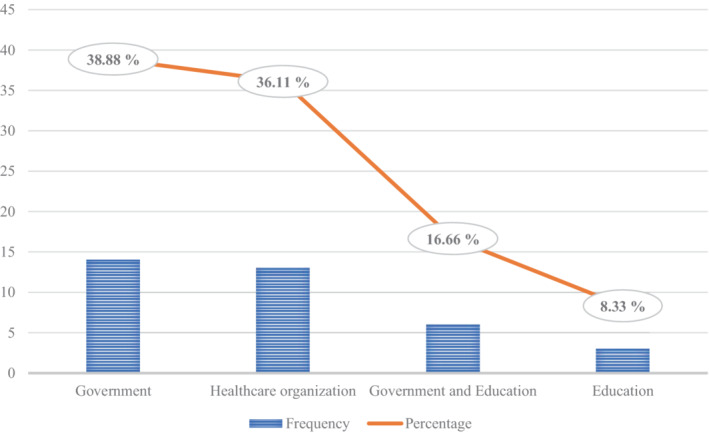

Organisations affiliated to academic and educational institutions are entities whose main purpose is improving the researchers and health professionals' knowledge in regard to science. Health care organisations refer to those institutions whose primary purpose is to enhance the awareness of the community, including researchers, specialists and ordinary people. A health agency or government foundation means a government or official body in a country that describes concepts related to health and various diseases. The sponsorships of these reviewed websites are given in Figure 5. It was found that various governments support 38.88% of these websites.

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of sponsorships of websites

DISCUSSION

According to the popularity and accessibility of the Internet, this study aimed to evaluate websites' quality on COVID‐19. Correspondingly, these websites provide critical health‐oriented information for all people on different social and scientific levels. Since many people have been looking to obtain reliable information during the current pandemic, this study was conducted to evaluate the quality of websites with high traffic. Therefore, 36‐related websites were selected in terms of the inclusion criteria and the retrieved websites were then analysed. Afterward, we classified the selected websites into the following four types: 1 – Informative dashboards (Epidemic Meters), 2 – Screening websites, 3 – Public information websites and 4 – Project Informative websites.

According to the increasing prevalence of COVID‐19, people, clinicians, epidemiologists and researchers need to improve their awareness and information on preventing the infection, COVID‐19's symptoms, its various effective treatments and medications, screening rules, related projects performed by researchers, the infection statistics and figures in different countries. Therefore, most websites in this regard were found to be related to informative dashboards and epidemic meters (Ojo et al., 2020). Some included websites can provide valid information to the public, clinicians and epidemiologists' audiences on how this virus spreads, how it permeates and how it transmits. Policy‐makers and health care providers have been able to provide appropriate and effective public information for ordinary people in the community, so they can meet all their needs regarding having information about COVID‐19 disease (Ojo et al., 2020). The target population in this investigation and in others (Flint et al., 2021; Ojo et al., 2020; Yu, 2021) are all individuals who get benefit from publishing information through the electronic platform and websites. However, the meaning of information in this research refers to a piece of general knowledge that can be provided to different people who are at different scientific levels. Cuan‐Baltazar et al. (2020) have believed that obtaining a thorough understanding of COVID‐19 disease depends on the establishment of reputable medical information websites, and in addition to general people, researchers can identify plans and projects in progress in this field. Most of the selected websites in the COVID‐19 domain are designed for the general public and researchers, so they are easy to use and do not require any substantial knowledge. We can conclude that most of the selected websites (approximately 67%) included in this study are used by ordinary users and researchers in the current pandemic. This study is one of the first papers performed on the quality of COVID‐19 websites using HON code principles and DISCERN tool. The DISCERN instrument provides a fundamental explaining on how to categorise content quality as ‘very poor’, ‘poor’, ‘fair’, ‘good’, or ‘excellent’ (Schwarzbach et al., 2021).

Since it is essential to gather up‐to‐date and reliable information to control and combat this pandemic, selected websites were also reviewed and then examined in terms of reliability (Shehata, 2021). Reliability in this context means that all visitors can trust health information on the websites. The reliability and quality levels in this survey were calculated based on the components in the HON tool and DISCERN questionnaire completed by the evaluators. For our websites, the findings indicated that the majority of included websites (n = 28, 77.77%) reached the acceptable and good reliability, relevancy and quality levels. Similar to our study, government websites were assumed to be more readable and relevant than other websites because their central mission is usually to train the general public (American Cancer Society, 2016; Yeung et al., 2022).

We restricted the websites to those developed by scientific and academic institutions based on the study's inclusion criteria. As a result, we suggest that people can trust the health‐related websites regarding COVID‐19 supported by academic institutions. Only one of the websites investigated in the current study did not reach a reliable level, including the dashboard of google for the Coronavirus. In line with our paper, the findings of a previous study (Valizadeh‐Haghi et al., 2021) also indicated that the credibility level of some websites' contents published by international and national health organisations and educational websites such as WHO and CDC was optimal for the general public. As well, the readability of affiliated websites is better than that of non‐affiliate websites, and previous studies reported that governmental websites were more readable and reliable than other types of websites (Garfinkle et al., 2019). The information retrieved from non‐authoritative websites is challenging because people consider these websites as significant sources of reliable health information (Valizadeh‐Haghi & Rahmatizadeh, 2018), especially during health crises such as the current outbreak of COVID‐19.

Due to the importance of validity in the context of health literacy, health promotion and patient's self‐care, we evaluated the reliability of COVID‐19 information available on reputable websites intended for the general public, which were retrieved from Google and Yahoo search engines. It is noteworthy that some of the websites included in this study had a number of weak points. According to the results of the HON and DISCERN tools, the quality of a few websites has been assessed as not very good, and this has been due to the challenging problems caused by COVID‐19 disease, the information about which is inadequate yet (Nazione et al., 2021). The reason or justification that we decided to include only the websites affiliated with reputable institutions was that COVID‐19 disease with an unknown identity caused severe problems for people worldwide, and also, users preferred to obtain their needed information from those websites related to institutions (Arghittu et al., 2021). Reliable and relevant information is constantly retrieved on the first pages of the web, so in this study, we examined the reputable websites on the first pages (first 10 pages). In search engines such as Google and Yahoo, reputed websites affiliated with health organisations are retrieved in the first pages because their information is frequently used (Stroobant, 2019).

‘Authority’ is one of the principles of the HON code, which indicates that the information provided on the websites by an expert in health science must be clearly referenced, and if health professionals have not prepared any material, its source should be mentioned (Qin et al., 2021). This factor can ensure visitors from the accuracy of the content, which was estimated to be 66.6% in our study, showing that the evaluated websites in terms of content were trustworthy. Contrary to our study that most of the evaluated websites have HON certification, researchers found that most websites examined in a previous study were not officially certified by the HON Foundation. Consequently, individuals searching for information on COVID‐19 may confront websites containing misinformation, which could lead to unreliable decision‐making and concern (Elhadad et al., 2020).

Strengths and limitations

The strength of our study was searching the two most popular search engines encompassing results worldwide. Moreover, we applied HON measures and DISCERN tool for quality evaluation, with four reviewers who independently completed the assessment checklist. One of the reviewers also validated the metrics for all websites. Our investigation suffers from some limitations as well; for example, we limited our investigation to English‐language websites and those dependent on scientific or academic institutions. So, we missed some websites that could not meet our inclusion criteria since our main objective was searching and reviewing reputable websites, which is why the authors left out some websites and only kept government websites with educational and research information. Given that the study's main purpose was to examine scientific and affiliated websites, we reviewed only 10 pages of each search engine and then selected the included websites. The purpose of choosing the first 10 pages was to make the popular and relevant websites appear on the first pages. Therefore, it can be said that the entry of scientific‐ and study‐related websites is considered as one of the main limitations of the research.

Implications for practice

Authoritative health information providers of various infectious diseases, including COVID‐19, should pay more attention to improve the quality of information published on their websites to help people better understand it. Furthermore, people in the community often prefer to attain their needed information from reputable websites. It is recommended that future research include an assessment by medical experts of the quality and accuracy of COVID‐19 provided information.

CONCLUSION

Our study was performed to evaluate and assess the quality of the COVID‐19 websites. In this study, we investigated two search engines in order to retrieve scientific websites. These websites can help people update their critical information on COVID‐19. This paper revealed that clinicians, researchers, and the public could potentially enhance their awareness and information about COVID‐19 as well as the related topics by browsing these websites. HON and DISCERN are brief questionnaires or comprehensive tools that could provide Internet users with a valid and reliable way to assess the quality of attained information related to various health problems. Scientifically, these two tools can work together to examine websites and information resources using different vital metrics; in this study, the raters scored the questions of each tool, and the quality of the information was assessed as well. The general public can trust COVID‐19 health‐related websites sponsored by academic institutions; because these websites have scientific origin. These websites are retrieved on the first pages of users' searches because they are used frequently, and people can obtain their needed information from them.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design of study: Reza Safdari and Sorayya Rezayi; Acquisition of data: Soheila Saeedi, Sorayya Rezayi, Mozhgan Tanhapour and Marsa Gholamzadeh; Analysis and/or interpretation of data: Sorayya Rezayi and Reza Safdari; Drafting the manuscript: Sorayya Rezayi, Marsa Gholamzadeh, Soheila Saeedi and Mozhgan Tanhapour; Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: Reza Safdari and Sorayya Rezayi; Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published: Reza Safdari and Sorayya Rezayi.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS).

Safdari, R. , Gholamzadeh, M. , Saeedi, S. , Tanhapour, M. , & Rezayi, S. (2022). An evaluation of the quality of COVID‐19 websites in terms of HON principles and using DISCERN tool. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 1–19. 10.1111/hir.12454

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

REFERENCES

- Abdekhoda, M. , Ranjbaran, F. , & Sattari, A. (2022). Information and information resources in COVID‐19: Awareness, control, and prevention. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 54(3), 363–372. 10.1177/09610006211016519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Benna, S. , & Gohritz, A. (2020). Availability of COVID‐19 information from national and international burn society websites. Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters, 33(3), 177–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alpaydın, M. T. , Buyuk, S. K. , & Canigur Bavbek, N. (2021). Information on the Internet about clear aligner treatment—An assessment of content, quality, and readability. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics/Fortschritte der Kieferorthopädie, 1–12. 10.1007/s00056-021-00331-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society . (2016). https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-basics/cancer-information-on-the-internet.html

- Arghittu, A. , Dettori, M. , Dempsey, E. , Deiana, G. , Angelini, C. , Bechini, A. , Bertoni, C. , Boccalini, S. , Bonanni, P. , Cinquetti, S. , Chiesi, F. , Chironna, M. , Costantino, C. , Ferro, A. , Fiacchini, D. , Icardi, G. , Poscia, A. , Russo, F. , Siddu, A. , … Cinquetti, S. (2021). Health communication in COVID‐19 era: Experiences from the Italian VaccinarSì Network Websites. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caria, S. , Fetzer, T. , Fiorin, S. , Goetz, F. , Gomez, M. , Haushofer, J. , Hensel, L. , Ivchenko, A. , Jachimowicz, J. , Kraft‐Todd, G. T. , Reutskaja, E. , Witte, M. , & Yoeli, E. (2020). Global behaviors and perceptions in the COVID‐19 pandemic. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14631. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3594262

- Chen, A. T. , Taylor‐Swanson, L. , Buie, R. W. , Park, A. , & Conway, M. (2018). Characterizing websites that provide information about complementary and integrative health: Systematic search and evaluation of five domains. Interactive Journal of Medical Research, 7(2), e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, M. A. , Moore, J. L. , Steege, L. M. , Koopman, R. J. , Belden, J. L. , Canfield, S. M. , Meadows, S. E. , Elliott, S. G. , & Kim, M. S. (2016). Health information needs, sources, and barriers of primary care patients to achieve patient‐centered care: A literature review. Health Informatics Journal, 22(4), 992–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuan‐Baltazar, J. Y. , Muñoz‐Perez, M. J. , Robledo‐Vega, C. , Pérez‐Zepeda, M. F. , & Soto‐Vega, E. (2020). Misinformation of COVID‐19 on the internet: Infodemiology study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e18444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Sherif, R. , Pluye, P. , Thoër, C. , & Rodriguez, C. (2018). Reducing negative outcomes of online consumer health information: Qualitative interpretive study with clinicians, librarians, and consumers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(5), e9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhadad, M. K. , Li, K. F. , & Gebali, F. (2020). Detecting misleading information on COVID‐19. IEEE Access, 8, 165201–165215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint, M. , Inglis, G. , Hill, A. , Mair, M. , Hatrick, S. , Tacchi, M. J. , & Scott, J. (2021). A comparative study of strategies for identifying credible sources of mental health information online: Can clinical services deliver a youth‐specific internet prescription? Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 16(6), 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbat, L. , Robinson, R. , Bilton‐Simek, R. , Francois, K. , Lewis, M. , & Haraldsdottir, E. (2018). Distance education methods are useful for delivering education to palliative caregivers: A single‐arm trial of an education package (PalliativE Caregivers Education Package). Palliative Medicine, 32(2), 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullard, A. C. , Johnston, S. M. , & Hehir, D. J. (2021). Quality and reliability evaluation of current Internet information regarding mesh use in inguinal hernia surgery using HONcode and the DISCERN instrument. Hernia, 25(5), 1325–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkle, R. , Wong‐Chong, N. , Petrucci, A. , Sylla, P. , Wexner, S. , Bhatnagar, S. , Morin, N. , & Boutros, M. (2019). Assessing the readability, quality and accuracy of online health information for patients with low anterior resection syndrome following surgery for rectal cancer. Colorectal Disease, 21(5), 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürtin, Z. B. , & Tiemann, E. (2021). The marketing of elective egg freezing: A content, cost and quality analysis of UKfertility clinic websites. Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online, 12, 56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halboub, E. , Al‐Ak'hali, M. S. , Al‐Mekhlafi, H. M. , & Alhajj, M. N. (2021). Quality and readability of web‐based Arabic health information on COVID‐19: An infodemiological study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasem, Z. , AlMeraj, Z. , & Alhuwail, D. (2022). Evaluating breast cancer websites targeting Arabic speakers: Empirical investigation of popularity, availability, accessibility, readability, and quality. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 22(1), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachfe, H. H. , Chahrour, M. A. , Habib, J. R. , Yu, J. , & Jamali, F. R. (2021). A quality assessment of the information accessible to patients on the Internet about the Whipple procedure. World Journal of Surgery, 45(6), 1853–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. , Zhou, X. , Zhou, Y. , Mao, F. , Shen, S. , Lin, Y. , Zhang, X. , Chang, T.‐H. , & Sun, Q. (2021). Evaluation of the quality and readability of online information about breast cancer in China. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(4), 858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F. S. , Nguyen, A. T. , Link, N. B. , Davis, J. T. , Chinazzi, M. , Xiong, X. , Vespignani, A. , Lipsitch, M. , & Santillana, M. (2020). Estimating the prevalence of COVID‐19 in the United States: Three complementary approaches. medRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.04.18.20070821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra, A. R. , Oermann, M. H. , Teague, M. S. , & Ledbetter, L. S. (2021). An evaluation of websites offering caregiver education for tracheostomy and home mechanical ventilation. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 56, 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh, N. , Gholamzadeh, M. , Saeedi, S. , & Rezayi, S. (2020). The application of wearable smart sensors for monitoring the vital signs of patients in epidemics: A systematic literature review. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 1–15. 10.1007/s12652-020-02656-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D. , & Harrison, V. (2018). Advice for health care professionals and users: An evaluation of websites for perinatal anxiety. JMIR Mental Health, 5(4), e11464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazione, S. , Perrault, E. , & Pace, K. (2021). Impact of information exposure on perceived risk, efficacy, and preventative behaviors at the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United States. Health Communication, 36(1), 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, P. M. , Okeowo, T. O. , Thampy, A. M. , & Kabir, Z. (2020). Readability of selected governmental and popular health organization websites on Covid‐19 public health information: A descriptive analysis. medRxiv.

- Paul, R. , Arif, A. A. , Adeyemi, O. , Ghosh, S. , & Han, D. (2020). Progression of COVID‐19 from urban to rural areas in the United States: A spatiotemporal analysis of prevalence rates. The Journal of Rural Health, 36(4), 591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo, I. A. , Johnson, C. V. , & Johnson, S. Y. (2021). Quality evaluation of consumer health information websites found on Google using DISCERN, CRAAP, and HONcode. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 40(4), 396–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Q. , Ke, Q. , Du, J. T. , & Xie, Y. (2021). How Users' gaze behavior is related to their quality evaluation of a health website based on HONcode principles? Data and Information Management, 5(1), 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, S. , Sharma, V. , Singh, A. , & Goel, S. (2016). Evaluation of quality and readability of health information websites identified through India's major search engines. Advances in Preventive Medicine, 2016, 4815285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbach, H. L. , Mady, L. J. , Kaffenberger, T. M. , Duvvuri, U. , & Jabbour, N. (2021). Quality and readability assessment of websites on human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. The Laryngoscope, 131(1), 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seven, Ü. S. , Stoll, M. , Dubbert, D. , Kohls, C. , Werner, P. , & Kalbe, E. (2021). Perception, attitudes, and experiences regarding mental health problems and web based mental health information amongst young people with and without migration background in Germany. A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, A. (2021). Health information behaviour during COVID‐19 outbreak among Egyptian library and information science undergraduate students. Information Development, 37(3), 417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Smekal, M. , Gil, S. , Donald, M. , Beanlands, H. , Straus, S. , Herrington, G. , Sparkes, D. , Harwood, L. , Tong, A. , Grill, A. , Tu, K. , Waldvogel, B. , Large, C. , Large, C. , Novak, M. , James, M. , Elliott, M. , Delgado, M. , Brimble, S. , … Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2019). Content and quality of websites for patients with chronic kidney disease: An environmental scan. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 6, 2054358119863091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John, A. , Carlisle, K. , Kligman, M. , & Kavic, S. M. (2021). What's Nissen on the net? The quality of information regarding Nissen fundoplication on the internet. Surgical Endoscopy, 36, 5198–5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroobant, J. (2019). Finding the news and mapping the links: A case study of hypertextuality in Dutch‐language health news websites. Information, Communication & Society, 22(14), 2138–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, A. , Hoy, C. , & Ortiz‐Juarez, E. (2020). Estimates of the impact of COVID‐19 on global poverty. UNU‐WIDER, April, 800–809.

- Valizadeh‐Haghi, S. , Khazaal, Y. , & Rahmatizadeh, S. (2021). Health websites on COVID‐19: Are they readable and credible enough to help public self‐care? Journal of the Medical Library Association, 109(1), 75–83. 10.5195/jmla.2021.1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valizadeh‐Haghi, S. , Moghaddasi, H. , Rabiei, R. , & Asadi, F. (2017). Health websites visual structure: The necessity of developing a comprehensive design guideline. Archives of Advances in Biosciences, 8(4), 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Valizadeh‐Haghi, S. , & Rahmatizadeh, S. (2018). Evaluation of the quality and accessibility of available websites on kidney transplantation. Urology Journal, 15(5), 261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venosa, M. , Tarantino, A. , Schettini, I. , Padua, R. , Cifone, M. G. , Calvisi, V. , & Romanini, E. (2021). Stem cells in orthopedic web information: An assessment with the DISCERN tool. Cartilage, 13(1_suppl), 519S–525S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, A. W. K. , Wochele‐Thoma, T. , Eibensteiner, F. , Klager, E. , Hribersek, M. , Parvanov, E. D. , Hrg, D. , Völkl‐Kernstock, S. , Kletecka‐Pulker, M. , Schaden, E. , Willschke, H. , & Atanasov, A. G. (2022). Official websites providing information on COVID‐19 vaccination: Readability and content analysis. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 8(3), e34003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y. , Stvilia, B. , & Mon, L. (2012). An understanding of cultural influence on seeking quality health information: A qualitative study. Library & Information Science, 34(1), 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S. Y. (2021). A review of the accessibility of ACT COVID‐19 information portals. Technology in Society, 64, 101467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.