Abstract

Recent knowledge on the key role of interleukin (IL) 23/17 axis in psoriasis pathogenesis, led to development of new biologic drugs. Risankizumab is a humanized immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody specifically targeting IL23. Its efficacy and safety were showed by both clinical trials and real‐life experiences. However, real‐life data on effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17 are scant. To assess the efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17. A 52‐week real‐life retrospective study was performed to assess the long‐term efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17. A total of 39 patients (26 male, 66.7%; mean age 50.5 ± 13.7 years) were enrolled. A statistically significant reduction of psoriasis area severity index (PASI) and body surface area (BSA) was assessed at each follow‐up (PASI at baseline vs. week 52: 13.7 ± 5.8 vs. 0.9 ± 0.8, p < 0.0001; BSA 21.9 ± 14.6 vs. 1.9 ± 1.7, p < 0.0001). Nail psoriasis severity index improved as well, being statistically significative only at week 16 and thereafter [9.3 ± 4.7 at baseline, 4.1 ± 2.4 (p < 0.01) at week 16, 1.4 ± 0.8 (p < 0.0001) at week 52]. Treatment was discontinued for primary and secondary inefficacy in 1(2.6%) and 3(7.7%) patients, respectively. No cases of serious adverse events were assessed. Our real‐life study confirmed the efficacy and safety of risankizumab, suggesting it as a valuable therapeutic weapon among the armamentarium of biologics, also in psoriasis patients who previously failed anti‐IL17 treatments.

Keywords: anti‐IL23, psoriasis, real life, risankizumab

1. INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune‐mediated inflammatory skin condition, with a worldwide prevalence of 2%–3%. 1 The high impact on quality of life and the possibility of serious comorbidities associated to psoriasis led to the need for effective and targeted therapies. 2

In this scenario, recent progress in psoriasis pathogenesis allowed the development of new treatment options, particularly small‐molecules and biologic drugs. 3 Among the cytokines involved in psoriasis, the axis of the interleukins (IL) 17 and 23 seems to play a key role. 3 Indeed, the production of IL‐23 causes the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into highly pathogenic helper T cells (Th17/ThIL‐17) which sustaining the inflammation by producing IL‐17, IL‐17F, IL‐6, and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)‐α. 3 Thus, drugs specifically targeting IL23 such as risankizumab, tildrakizumab and guselkumab as well as biologics acting against IL17 (ixekizumab, brodalumab and secukinumab) have been approved for psoriasis management, showing promising results and superiority to anti‐tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α and anti‐IL12/23. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

However, the availability of 11 different biologics, the need for a tailored treatment as well as the importance of comorbidities and possible biologic drug related events [e.g., paradoxical psoriatic arthritis (PsA) or paradoxical eczematous eruptions], 11 , 12 , 13 may still provide therapeutical challenges. 14 This is particularly true in real‐life settings which deal with more complicated (numerous comorbidities, polypharmacy and frequent previous failure of biologics) subjects compared to trials. Thus, real‐life studies are needed in order to help clinicians to choose the right treatment at the right moment for the right patient.

Risankizumab is a humanized immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody specifically targeting IL23 by binding its p19 subunit. 15 It has been approved by European Medicines Agency in April 2019 for the management of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis and in 2021 for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Its efficacy and safety were showed by several clinical trials. 16 , 17 Particularly, risankizumab has been showed to be more effective than adalimumab, secukinumab and ustekinumab. 18 , 19 , 20 Promising results have been showed in real‐life settings as well. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 However, studies regarding the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17 are scant, and existing data are limited to few cases, studies with limited follow‐up and/or not specifically investigating the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab after IL17 failure. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 However, anti‐IL23 and anti‐IL17 drugs partially share their therapeutic target on IL23/Th17 pro‐inflammatory axis which guide psoriasis pathogenesis. Hence, more data are needed to understand if previous failure of anti‐IL17 may reduce the efficacy of anti‐IL23 in short and long term. Thus, the aim of our study is assessing the efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17 up to 52 weeks of treatment.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

A monocentric retrospective study was carried out enrolling patients affected by moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis undergoing treatment with risankizumab and attending the Psoriasis Care Centre of Dermatology at the University Federico II of Naples from May 2019 to January 2022. Inclusion criteria were: presence of moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis assessed by a dermatologist for at least 12 months; risankizumab treatment for at least 16 weeks; previous failure (primary or secondary failure) of one or more anti‐IL17 drugs (brodalumab, ixekizumab and/or secukinumab). Exclusion criteria were: patients <18 years old; palmoplantar or generalized pustular psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, concomitant systemic treatment for psoriasis. Demographic (age, sex) and clinical features [psoriasis duration, duration of PsA (if present), psoriasis severity through body surface area (BSA) and psoriasis activity severity index (PASI), nail psoriasis severity index (NAPSI) (if applicable), comorbidities, previous and current psoriasis treatment] were collected for each patient at baseline. Moreover, psoriasis severity (PASI, BSA and NAPSI) was assessed at each follow‐up visit (week 4, week 16, week 28, week 40, week 52) as well as routine blood tests [blood count with formula, transaminases, creatinine, azotemia, glycaemia, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum protein electrophoresis, C reactive protein, total cholesterol and triglycerides], and adverse events (AEs). Risankizumab was administered at labeled dosage for psoriasis (150 mg as a subcutaneous injection at week 0, week 4, and every 12 weeks thereafter).

Regarding the efficacy, primary lack of efficacy was considered as a clinical response less than a PASI75 after 16 weeks of treatment whereas secondary inefficacy was defined as the assessment of an inadequate improvement <PASI75 after an initial clinical response at 16 weeks. Effectiveness data were analyzed using a last observation carried forward method, where if a patient dropped out of the study the last available value was “carried forward” until the end of the treatment. Safety was assessed by treatment‐emergent AEs, physical examinations and laboratory monitoring. The present study was conducted respecting the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients signed an informed consent before starting the study.

3. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Clinical and demographic data were analyzed through descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD while number and proportion of patients were used for categorical ones. Statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was carried out in order to assess the statistically significance of clinical response. Chi‐square test and Student's t test were used to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences in values obtained at the different time points of therapy for categorical variables and continuous ones, respectively. p values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

4. RESULTS

Eighty‐nine patients treated with risankizumab attending our clinic were screened. Forty‐two (47.2%) subjects respected the inclusion criteria. However, only 39 (43.8%) patients (26 male, 66.7%; mean age 50.5 ± 13.7 years, range 20–73 years, mean psoriasis duration 17.2 ± 9.7 years) completed the follow‐up period (Table 1). Fifteen (38.5%) patients were also affected by PsA and nail involvement was observed in nine subjects (23.1%). Hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity (17, 43.6%), followed by obesity (16, 41.0%), diabetes (13, 33.3%) and dyslipidemia (9, 23.1%) (Table 1). As regards previous treatment, all subjects have been previously treated with one or more conventional systemic treatments, with methotrexate as the main one (29, 74.4%) followed by cyclosporine (26, 66.7%) and Nb‐UVB Phototherapy (11, 28.2%) (Table 1). Notably, almost all subjects (37, 94.9%) patients failed an anti‐TNFα and 17 (43.6%) ustekinumab (Table 1). All of the patients experienced a treatment failure with at least one anti‐IL17; particularly 26 (66.7%) failed ixekizumab (average duration of treatment: 14.7 ± 8.9 months), 24 (61.5%) secukinumab (average duration of treatment: 12.8 ± 10.8), 7 (17.9%) both secukinumab and ixekizumab and 2 (5.1%) brodalumab (average duration of treatment: 4.3 ± 2.6) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patients' feature at baseline (week 0)

| Number of patients | 39 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 26 (66.7%) |

| Female | 13 (33.3%) |

| Mean age (years) | 50.5 ± 13.7 |

| Mean duration of psoriasis (years) | 17.2 ± 9.7 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 15 (38.5%) |

| Nail psoriasis | 9 (23.1%) |

| Psoriasis activity | |

| PASI | 13.7 ± 5.8 |

| BSA | 21.9 ± 14.6 |

| NAPSI | 9.3 ± 4.7 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 17 (43.6%) |

| Obesity | 16 (41.0%) |

| Diabetes | 13 (33.3%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 9 (23.1%) |

| Cardiopathy | 5 (12.8%) |

| Depression | 3 (7.7%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (5.1%) |

| Previous systemic treatments (conventional and small‐molecules) | |

| Methotrexate | 29 (74.4%) |

| Cyclosporine | 26 (66.7%) |

| Nb‐UVB phototherapy | 11 (28.2%) |

| Acitretin | 5 (12.8%) |

| Apremilast | 3 (7.7%) |

| Previous biologic treatments | |

| Anti‐TNFα | |

| Adalimumab | 12 (30.8%) |

| Etanercept | 9 (23.1%) |

| Infliximab | 7 (17.9%) |

| Golimumab | 5 (12.8%) |

| Certolizumab | 4 (10.3%) |

| Anti‐IL12/23 | 17 (43.6%) |

| Anti‐IL17 | |

| Ixekizumab | 26 (66.7%) |

| Secukinumab | 24 (61.5%) |

| Brodalumab | 2 (5.1%) |

| Average duration of treatment (months) | |

| Anti‐TNFα | |

| Adalimumab | 7.5 ± 6.4 |

| Etanercept | 10.7 ± 11.8 |

| Infliximab | 5.3 ± 4.8 |

| Golimumab | 11.0 ± 11.2 |

| Certolizumab | 6.1 ± 2.9 |

| Anti‐IL12/23 | 27.8 ± 18.1 |

| Anti‐IL17 | |

| Ixekizumab | 14.7 ± 8.9 |

| Secukinumab | 12.8 ± 10.8 |

| Brodalumab | 4.3 ± 2.6 |

Note: PASI 90 and PASI 100 were achieved at week 16 by 24 (61.5%) and 14 (35.9%) patients, respectively and by 33 (84.6%) and 25 (64.1%) patients at week 52.

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; NAPSI, nail psoriasis severity index (NAPSI); Nb‐UVB, narrow band – ultraviolet B; PASI, psoriasis activity severity index.

Baseline clinical evaluation showed a mean PASI of 13.7 ± 5.8, mean BSA of 21.9 ± 14.6 and a mean NAPSI of 9.3 ± 4.7.

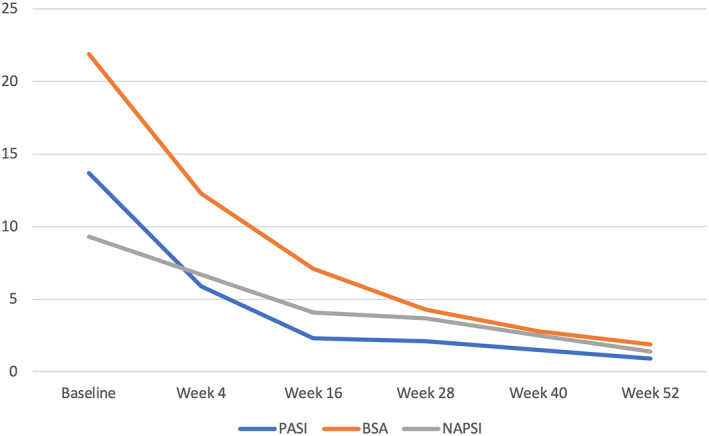

Both PASI and BSA revealed a statistically significant improvement since week 4 [PASI: 5.9 ± 2.9 (p < 0.0001); BSA: 12.3 ± 6.9 (p < 0.001)], with 6 (15.4%) patients achieving PASI 90 response and 3 (7.7%) patients reaching PASI100, respectively. Then, PASI and BSA reduction was confirmed at week 16 [PASI: 2.3 ± 1.9 (p < 0.0001); BSA: 7.1 ± 4.1 (p < 0.0001)] and at each follow‐up visit up to week 52 [PASI: 0.9 ± 0.8 (p < 0.0001), BSA: 1.9 ± 1.7 (p < 0.0001)]. Similarly, PASI 90 and PASI 100 were achieved at week 16 by 24 (61.5%) and 14 (35.9%) patients, respectively, and by 33 (84.6%) and 25 (64.1%) patients at week 52. As regards NAPSI, clinical improvement was already assessed at week 4 (6.7 ± 4.6), being statistically significant for the first time at week 16 (4.1 ± 2.4, p < 0.01) and then up to week 52 (1.4 ± 0.8, p < 0.0001).

All investigated psoriasis scores are displayed in Figure 1 and Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Mean PASI, BSA and NAPSI assessment at baseline, week 4, week 16, week 28, week 40 and week 52. BSA, body surface area; NAPSI, nail psoriasis severity index; PASI, psoriasis activity severity index.

TABLE 2.

Psoriasis assessment at baseline, week 4, week 16, week 28, week 40 and week 52

| Week | 0 | 4 | 16 | 28 | 40 | 52 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PASI | 13.7 ± 5.8 | 5.9 ± 2.9 | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 0.9 ± 0.8 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| BSA | 21.9 ± 14.6 | 12.3 ± 6.9 | 7.1 ± 4.1 | 4.3 ± 2.3 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ± 1.7 |

| <0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| NAPSI | 9.3 ± 4.7 | 6.7 ± 4.6 | 4.1 ± 2.4 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 0.8 |

| <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; NAPSI, nail psoriasis severity index; PASI, psoriasis activity severity index.

Discontinuation for primary and secondary inefficacy was assessed in 1 (2.6%) and 3 (7.7%) patients, respectively. Particularly, primary inefficacy was recorded in a patient who previously failed secukinumab while 2 (5.1%) patients who previously failed both secukinumab and ixekizumab stopped treatment between week 28–40 and 1 (2.6%) patient, previously treated with ixekizumab, discontinued treatment at week 40. Hence, risankizumab discontinuation for inefficacy was registered in 4/39 (10.2%) subject in our 52‐week real‐life study.

Regarding the safety, no cases of serious AEs, injection site reaction, candida, major cardiovascular events, or malignancy, were collected in our study. However, mild AEs were assessed in 11 (28.2%) subjects: nasopharyngitis (7.7%), upper respiratory tract infections (5.1%), headache (5.1%), fatigue: (5.1%), arthralgia (2.6%), and pruritus: (2.6%), all without requiring treatment discontinuation. Moreover, mild alterations were reported at routine blood tests in 5 (12.8%) patients, with mild transient hyperglycemia, mild liver enzyme elevation and mild leukocytosis in 2 [5.1%: 124 and 121 mg/dl (n.v. 60–100 mg/dl)], 2 [5.1%: GOT: 171 and 133 U/L (n.v. 0–37 U/L), GPT: 123 and 55 U/L (n.v. 0–45 U/L) and γ‐GT: 47 and 38 U/L (n.v. 10–39 U/L)] and 1 [2.6%: total white blood cells count: 13000 (n.v. 4500–11,000 μl)] patients, respectively, all without requiring treatment discontinuation.

Of note, 1 patient (2.6%) developed mild new‐onset PsA, successfully treated adding oral corticosteroids to risankizumab treatment. Finally, 4 (10.3%) patients temporarily suspended risankizumab (range 1–6 weeks) because of SarsCov2 infection or for “at‐risk” contact with a subject affected by Covid‐19.

5. DISCUSSION

Major advancements in psoriasis pathogenesis, particularly on the importance of 17/23 axis, 32 , 33 , 34 allowed the development of new drugs selectively targeting these cytokines, which showed promising results in terms of safety and effectiveness also during the Covid‐19 pandemic period. 35 , 36 In this background, among the jungle of the numerous existing biological therapies, 14 drugs targeting IL17 and IL23 which partially share their therapeutic target, represent the most efficacious available treatment options for moderate‐to‐severe disease. 14 However, primary or secondary lack of efficacy is reported also with these drugs, and biologic switching still remain the main therapeutic option in those cases. 37

In this scenario, more real‐life data are needed in order to offer to psoriasis patients a tailored‐tail treatment and guide treatment choice. 14 Among drugs selectively targeting IL23, risankizumab showed to be more effective than adalimumab, secukinumab and ustekinumab in clinical studies, 18 , 19 , 20 and its high efficacy profile has also been showed in real‐life settings. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 To date, literature data regarding the effectiveness of risankizumab in patients who failed anti‐IL17 are limited to case series, small studies with limited follow‐up and/or not specifically investigating the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab after IL17 failure. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 Hence, we performed a retrospective study in order to evaluate the efficacy and safety or risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17 in a real‐life setting up to 52 weeks.

In our cohort, 39 out of 89 screened patients completed the follow‐up period respecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The effectiveness of risankizumab was observed since week 4, showing a statistically significant improvement of PASI (5.9 ± 2.9 vs. 13.7 ± 5.8, p < 0.0001) and BSA (12.3 ± 6.9 vs. 21.9 ± 14.6, p < 0.001). PASI and BSA significant improvement was confirmed at each follow‐up visit up to week 52 [PASI: 0.9 ± 0.8 (p < 0.0001); BSA: 1.9 ± 1.7 (p < 0.0001)] (Figure 1, Table 2). This results are similar to those of a previous 16‐week real‐life experience 25 on 8 patients undergoing treatment with risankizumab who previously failed anti‐IL17 which showed a statistically significant psoriasis improvement from baseline to week 4 (PASI: 11.9 vs. 5.5, BSA: 22.9 vs. 10.7, p < 0.05 for both) up to week 16 [PASI: 3.3 (p < 0.001), BSA: 7.5 (p < 0.01). 25 Similarly, a recent real‐life multicenter retrospective study on 44 patients (65.9% male; mean age 52.8 years) showed a PASI reduction from 12.3 to 5.3 and to 1.3 at 1 and 3 months follow‐up, respectively, with 45% of patients achieving PASI 100 at 3 months. 26 Of note 12 (32.4%) subjects in this cohort of patients had previously failed an anti‐IL17. 26 However, detailed sub analysis of antiIL‐17 bio‐experienced vs. anti‐IL17 naïve subjects had not been performed.

In our cohort, at week 4, PASI 90 and PASI100 were achieved by 6 (15.4%) and 3 (7.7%) subjects, respectively increasing to 24 (61.5%) and 14 (35.9%) at week 16 and 33 (84.6%) and 25 (64.1%) at week 52.

Nine (23.1%) patients showed nail psoriasis at baseline (NAPSI: 9.3 ± 4.7). Even if clinical improvement was observed since week 4 (6.7 ± 4.6), NAPSI reduction was firstly statistically significant at week 16 (4.1 ± 2.4, p < 0.01) up to week 52 (1.4 ± 0.8, <0.0001). Instead, in one of our previous real‐life study 25 nail involvement was assessed in 2 (25.0%) patients who previously failed ixekizumab, showing improvement albeit not reaching statistical significance up to week 16 (NAPSI: 18.0 at baseline reducing to 16 at week 4 and 7 at week 16). 25

In our study. Risankizumab discontinuation rate was 10.2% (n = 4) up to 52 weeks of treatment (75% secondary inefficacy). However, possible predictive factors which may increase the risk of inefficacy were not assessed.

As regards safety, no cases of serious AEs were collected and only 11 (28.2%) patients reported mild AEs, with nasopharyngitis (3, 7.7%) and upper respiratory tract infection (2, 5.1%), as the main ones. Moreover, 5 (12.8%) patients showed mild blood chemistry alterations and 1 patient (2.6%) developed new‐onset PsA which did not require treatment switching. No AEs required treatment suspension. These results confirmed data previously showed by our group which did not collect major AEs in their 16‐weeks experience. 25

However, in our experience 4 (10.3%) patients temporarily suspended risankizumab scheduled administration due to SarsCov2 infection or for “at‐risk” contact with a patient affected by Covid‐19.

In literature, there are five case series or small real‐life studies reporting data on the efficacy and safety of risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31

However, most of these studies show very limited number of patients and/or follow‐up . 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Indeed, our preliminary study conducted did not involve patients who previously failed brodalumab, had a limited follow‐up (16 weeks) period and a limited cohort of patients. 25 The short‐term follow‐up period (3 months) is the major limitation also for Rivera‐Díaz et al experience together with limited sample size. 26 Similarly, only three patients treated with risankizumab after anti IL‐17 failure were included in Bonifati et al. 27 study, showing a significant improvement of psoriasis after 3 months of treatment without AEs reported. A recent case‐series reported by Dawoud et al. showed the effectiveness of risankizumab in two patients affected by plaque psoriasis and pustular psoriasis previously treated with secukinumab and ixekizumab. Indeed, both the patients reached a PASI 100 response at week 28, without reporting serious AEs. 28

Even if not particularly focusing on anti‐IL17 failure, the results of a multicenter real‐life experience involving 166 patients treated with risankizumab up to 52 weeks were recently reported by Mastorino et al. 29 In particular, 165, 103, 30 and 11 subjects completed 16, 28, 40, and 52 weeks of treatment, respectively showing a statistically significative PASI decrease from baseline (12.5) to week 16 (1.9) up to week 52 (0.5) (p = 0.0001). 29 In particular PASI 90 and PASI 100 were achieved by 53% and 32% of patients at week 16, and by 82%, and 73% of patients at week 52, respectively. 29 In their cohort, patients previously treated with secukinumab, ixekizumab and brodalumab were 27 (16.3%), 34 (20.5%) and 10 (6.0%), respectively. 29 However, detailed sub analysis of anti‐IL‐17 bio‐experienced versus anti‐IL17 naïve subjects had not been performed. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first long‐term study specifically investigating the effectiveness of risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17 and with the larger cohort.

Our results confirmed the efficacy and safety of risankizumab, suggesting this biologic drug as a valuable weapon in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis unresponsive to anti‐IL17. Moreover, switching from IL17 does not seem to affect risankizumab effectiveness, confirming the results of Rivera‐Díaz et al. which also recently assessed that prior biologic treatments did not statistically significant affect risankizumab effectiveness comparing biologics‐naïve and non‐biologic‐naïve patients. 26 Hansel et al. 30 showed that previous biologic failure did not affect risankizumab effectiveness as well. In their cohort, among the 57 patients who completed the 16‐week follow‐up period, 41 (71.9%) were previously treated with at least one biologic. Overall, at week 16 49 (86.0%), 36 (63.2%) and 28 (49.1%) of patients achieved PASI75, PASI 90 and PASI 100, respectively. 30

Similarly, Gkalpakiotis et al. suggested that previous biologic therapy did not affect PASI 90 and PASI 100 response in a cohort of 154 patients treated with risankizumab in a 52‐weeks multicenter experience, including 20 patients (13.0%) who previously failed anti‐IL17. 31 On the contrary, in their analysis, only Mastorino et al. showed that previous biological treatment failure showed impact on the response to risankizumab. 29 Indeed, PASI in bio‐naive and bio‐experienced patients at 16 weeks was 1.3 and 2.3 (p = 0.047), with 65% and 44% of patients reaching PASI 90, (p = 0.007), and 83% and 66% PASI 75 (p = 0.020), respectively. 29 At 28 weeks 86% of bio‐naïve patients and 62% of bio‐experienced ones reached PASI 90 (p = 0.008), respectively. 29 Statistically significant differences were also detected at week 40 in the achievement of PASI [90 (100% of bio‐naïve patients vs. 64% in bio‐experienced (p = 0.046)]. 29

Certainly, further studies are required to compare the efficacy of risankizumab in patients who previously failed anti‐IL17 to patients anti IL17 naïve as well as further experiences will allow to improve the knowledge on the biologic armamentarium guiding clinicians in daily practice.

6. LIMITATIONS

The retrospective design, the size of our cohort, the limited number of patients who previously failed brodalumab as well as the limited number of patients with nail involvement may be the main limitations, reducing the generalizability of our results. The fact that 4 (10.3%) patients temporarily delayed risankizumab scheduled administration due to Covid‐19 infection or “at‐risk” contact with a subject affected by Covid‐19 may represent another limitation which could have influenced data.

7. CONCLUSIONS

Our real‐life monocentric retrospective experience confirmed the effectiveness and safety of risankizumab which do not seem to be reduced by previous anti‐IL‐17 treatments failure. However, further studies are needed to confirm our results as well as to gain data to support the best evidence based biologic selection algorithm.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Matteo Megna acted as a speaker or consultant for Abbvie, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Janssen, UCB, Amgen, Leo Pharma; Gabriella Fabbrocini acted as a speaker or consultant for Abbvie, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Janssen, UCB, Amgen, Leo Pharma, Almirall. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Matteo Megna: Conceptualization, validation, visualization, writing‐original draft preparation, writing—review & editing. Luca Potestio: Data curation, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft preparation. Angelo Ruggiero: Data curation, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft preparation. Elisa Camela: Data curation, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft preparation. Gabriella Fabbrocini: Conceptualization, validation, visualization, writing—review & editing, supervision. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not required.

PATIENT CONSENT

Not required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Napoli Federico II within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

Megna M, Potestio L, Ruggiero A, Camela E, Fabbrocini G. Risankizumab treatment in psoriasis patients who failed anti‐IL17: A 52‐week real‐life study. Dermatologic Therapy. 2022;35(7):e15524. doi: 10.1111/dth.15524

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gisondi P, Geat D, Pizzolato M, Girolomoni G. State of the art and pharmacological pipeline of biologics for chronic plaque psoriasis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;46:90‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):377‐390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gooderham MJ, Papp KA, Lynde CW. Shifting the focus ‐ the primary role of IL‐23 in psoriasis and other inflammatory disorders. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(7):1111‐1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Megna M, Potestio L, Fabbrocini G, Cinelli E. Tildrakizumab: A new therapeutic option for erythrodermic psoriasis? Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:e15030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Colombo D, Bianchi L, Fabbrocini G, et al. Real‐world evidence of biologic treatments in moderate‐severe psoriasis in Italy: results of the CANOVA (EffeCtiveness of biologic treAtmeNts for plaque psOriasis in Italy: an obserVAtional longitudinal study of real‐life clinical practice) study. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(1):e15166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Megna M, Cirillo T, Balato A, Balato N, Gallo L. Real‐life effectiveness of biological drugs on psoriatic difficult‐to‐treat body regions: scalp, palmoplantar area and lower limbs. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol: JEADV Engl. 2019;33:e22‐e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Megna M, Gallo L, Balato N, Balato A. A case of erythrodermic psoriasis successfully treated with ixekizumab. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(2):e12825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Narcisi A, Valenti M, Cortese A, et al. Anti‐IL17 and anti‐IL23 biologic drugs for scalp psoriasis: a single‐center retrospective comparative study. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(2):e15228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Armstrong AW, Puig L, Joshi A, et al. Comparison of biologics and Oral treatments for plaque psoriasis: a meta‐analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(3):258‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Megna M, Potestio L, Ruggiero A, Camela E, Fabbrocini G. Guselkumab is efficacious and safe in psoriasis patients who failed anti‐IL17: a 52‐week real‐life study. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;1–18:1‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Megna M, Ocampo‐Garza SS, Potestio L, et al. New‐onset psoriatic arthritis under biologics in psoriasis patients: An increasing challenge? Biomedicines. 2021;9(10):1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Napolitano M, Megna M, Fabbrocini G, et al. Eczematous eruption during anti‐interleukin 17 treatment of psoriasis: an emerging condition. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:604‐606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Megna M, Ocampo‐Garza SS, Fabbrocini G, Potestio L. Letter to the editor submitted in response to “should the presence of psoriatic arthritis change how we manage psoriasis?”. J Dermatol Treatment. 2022;1‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Megna M, Balato A, Napolitano M, et al. Psoriatic disease treatment nowadays: unmet needs among the “jungle of biologic drugs and small molecules”. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37:1739‐1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, et al. Anti‐IL‐23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single‐rising‐dose, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):116‐124.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lebwohl MG, Soliman AM, Yang H, et al. Impact of risankizumab on PASI90 and DLQI0/1 duration in moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: a post hoc analysis of four phase 3 clinical trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;12:407‐418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Augustin M, Lambert J, Zema C, et al. Effect of risankizumab on patient‐reported outcomes in moderate to severe psoriasis: the UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(12):1344‐1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaçi D, et al. Risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double‐blind, active‐comparator‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2019;394(10198):576‐586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2): results from two double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled and ustekinumab‐controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet (London, England). 2018;392(10148):650‐661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crowley JJ, Langley RG, Gordon KB, et al. Efficacy of risankizumab versus secukinumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: subgroup analysis from the IMMerge study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(2):561‐575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G, Cinelli E, Megna M. Guselkumab and risankizumab for psoriasis: a 44‐week indirect real‐life comparison. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1028‐1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Megna M, Cinelli E, Gallo L, Camela E, Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G. Risankizumab in real life: preliminary results of efficacy and safety in psoriasis during a 16‐week period. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G, Cinelli E, Ocampo Garza SS, Camela E, Megna M. Anti‐interleukin‐23 for psoriasis in elderly patients: guselkumab, risankizumab and tildrakizumab in real‐world practice. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;47:561‐567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G, Cinelli E, Megna M. Real world practice indirect comparison between guselkumab and risankizumab: results from an Italian retrospective study. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(1):e15214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Megna M, Fabbrocini G, Ruggiero A, Cinelli E. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in psoriasis patients who failed anti‐IL‐17, anti‐12/23 and/or anti IL‐23: preliminary data of a real‐life 16‐week retrospective study. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e14144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rivera‐Díaz R, LLamas‐Velasco M, Hospital M, et al. Risankizumab in psoriasis: prior biologics failure does not impact on short‐term effectiveness. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22(1):105‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bonifati C, Morrone A, Cristaudo A, Graceffa D. Effectiveness of anti‐interleukin 23 biologic drugs in psoriasis patients who failed anti‐interleukin 17 regimens. A Real‐Life Experience Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(1):e14584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dawoud NM, El Badawy MB, Al Eid HS, Abdel Fattah MM. Risankizumab effectiveness and safety in psoriasis patients who failed other biologics: real‐life case series. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2022;88(2):235‐240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mastorino L, Sara S, Megna M, et al. Risankizumab shows high efficacy and maintainance in improvement of response until week 52. Dermatol Ther. 2022;e15378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hansel K, Zangrilli A, Bianchi L, et al. A multicenter study on effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in psoriasis: an Italian 16‐week real‐life experience during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(3):e169‐e170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gkalpakiotis S, Cetkovska P, Arenberger P, et al. Risankizumab for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: real‐life multicenter experience from the Czech Republic. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(4):1345‐1355. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00556-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Radi G, Campanati A, Diotallevi F, Bianchelli T, Offidani A. Novel therapeutic approaches and targets for treatment of psoriasis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2021;22(1):7‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Girolomoni G, Strohal R, Puig L, et al. The role of IL‐23 and the IL‐23/T(H) 17 immune axis in the pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(10):1616‐1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boutet M‐A, Nerviani A, Gallo Afflitto G, Pitzalis C. Role of the IL‐23/IL‐17 Axis in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: the clinical importance of its divergence in skin and joints. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(2):530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Potestio L, Camela E, Fabbrocini G, Megna M. Letter to the editor regarding article “Yalici‐Armagan B, Tabak GH, Dogan‐Gunaydin S, Gulseren D, Akdogan N, Atakan N. treatment of psoriasis with biologics in the early COVID‐19 pandemic: a study examining patient attitudes toward the treatment and disease course. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;00:1‐5”. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(12):4073‐4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Megna M, Potestio L, Gallo L, Caiazzo G, Ruggiero A, Fabbrocini G. Reply to “psoriasis exacerbation after COVID‐19 vaccination: report of 14 cases from a single Centre” by Sotiriou E et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol: JEADV. 2022;36:e11‐e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tsai Y‐C, Tsai T‐F. Switching biologics in psoriasis ‐ practical guidance and evidence to support. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13(5):493‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.