Abstract

Background

Post‐mastectomy radiation therapy (PMRT) in women with pathologic stage T1‐2N1M0 breast cancer is controversial.

Methods

Data from five North American institutions including women undergoing mastectomy without neoadjuvant therapy with pT1‐2N1M0 breast cancer treated from 2006 to 2015 were pooled for analysis. Competing‐risks regression was performed to identify factors associated with locoregional recurrence (LRR), distant metastasis (DM), overall recurrence (OR), and breast cancer mortality (BCM).

Results

A total of 3532 patients were included for analysis with a median follow‐up time among survivors of 6.8 years (interquartile range [IQR], 4.5–9.5 years). The 2154 (61%) patients who received PMRT had significantly more adverse risk factors than those patients not receiving PMRT: younger age, larger tumors, more positive lymph nodes, lymphovascular invasion, extracapsular extension, and positive margins (p < .05 for all). On competing risk regression analysis, receipt of PMRT was significantly associated with a decreased risk of LRR (hazard ratio [HR], 0.21; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14–0.31; p < .001) and OR (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62–0.94; p = .011). Model performance metrics for each end point showed good discrimination and calibration. An online prediction model to estimate predicted risks for each outcome based on individual patient and tumor characteristics was created from the model.

Conclusions

In a large multi‐institutional cohort of patients, PMRT for T1‐2N1 breast cancer was associated with a significant reduction in locoregional and overall recurrence after accounting for known prognostic factors. An online calculator was developed to aid in personalized decision‐making regarding PMRT in this population.

Keywords: breast cancer, mastectomy, post‐mastectomy radiation, risk prediction, T1‐2N1 breast cancer

Short abstract

In a large multi‐institutional cohort of patients, post‐mastectomy radiation therapy (PMRT) for T1‐2N1 breast cancer was associated with a significant reduction in locoregional and overall recurrence after accounting for known prognostic factors. An online calculator was developed to aid in personalized decision‐making regarding PMRT in this population.

INTRODUCTION

In women with breast cancer involving 1–3 lymph nodes (N1) after a mastectomy, data from older randomized trials demonstrated that post‐mastectomy radiation therapy (PMRT) significantly reduced the risk of locoregional recurrence (LRR). 1 , 2 , 3 As advances in systemic therapy have been made in recent years, modern series have reported significantly lower rates of LRR than these historical controls for patients with pathologic stage T1‐2N1 breast cancer, with 5‐year rates of 4%–11% after mastectomy in the absence of radiotherapy. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Thus, the absolute magnitude of risk reduction by PMRT in this patient population is uncertain in the modern era, and specific indications for PMRT use based on individualized patient risk estimation remain controversial. 11

A number of risk factors are associated with LRR in this population; however, these vary widely across published institutional series. Adverse risk factors have included tumor size, 4 , 5 younger age, 6 , 7 , 10 estrogen receptor (ER)‐negativity, 5 high grade, 5 , 8 , 9 lymphovascular invasion (LVI), 5 , 6 nodal extracapsular extension (ECE), 8 tumor location, 9 and treatment era. 4 Consistently, adjuvant PMRT is associated with a reduced relative risk of LRR, despite patients selected to receive PMRT having more adverse risk features than those not receiving PMRT. However, whether PMRT reduces the risk of distant metastases (DM), overall recurrence (OR), and breast cancer mortality (BCM), is less clear for N1 patients in the modern era.

No contemporary randomized trials have assessed the role of PMRT for N1 breast cancer, and data from the SUPREMO (Selective Use of Postoperative Radiotherapy aftEr MastectOmy) trial are awaited to better counsel patients on adjuvant treatment recommendations. Because of the lack of objective decision‐making tools, clinicians must often make subjective decisions about PMRT utilization. 11 In this multi‐institutional pooled analysis, we aim to provide clinicians and patients with more objective and individualized risk estimates of outcomes with or without PMRT in this diverse patient population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After approval from the institutional review board, retrospective data from five North American institutions were collected and pooled for evaluation. Female patients with invasive breast cancer treated with mastectomy between the years 2006–2015 (after adjuvant trastuzumab was approved for Her2/neu‐positive breast cancer), with pathologic tumor size of 5 cm or less (T1‐2), 1–3 positive lymph nodes (LNs), and no evidence of metastatic disease were eligible for inclusion. Patients undergoing axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) or sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) were included. Patients were excluded if they received preoperative systemic therapy (including chemotherapy [CHT], hormonal therapy, and/or targeted biologic agents), had a previous or synchronous contralateral breast cancer, were treated for recurrent breast cancer, did not return for follow‐up care after surgery, or were missing key pathology information (estrogen receptor [ER] status, Her2/neu status, or tumor size).

Demographic, pathologic, and treatment information were obtained from each institution, including age at diagnosis, laterality, tumor location, histology, grade, pathologic tumor size, presence of multicentricity, date of mastectomy, extent of axillary dissection, number of LNs positive, nodal ratio (number of LNs positive divided by number of LNs dissected), LVI, ECE, surgical margin status, ER status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, Her2/neu gene amplification, receipt of PMRT, and receipt of adjuvant CHT, hormonal therapy, or trastuzumab. Patients with ER‐positive and/or PR‐positive tumors were categorized as ER/PR‐positive; those with both ER‐ and PR‐negativity were categorized as ER/PR‐negative. Optimal systemic therapy was defined as receiving endocrine therapy if ER‐ or PR‐positive, trastuzumab if Her2‐positive, and CHT if ER‐ and PR‐negative. Patients with macroscopic nodal involvement were categorized as N1; those with microscopic nodal involvement were categorized as N1mic; and those with undocumented nodal size were categorized as N1‐not otherwise specified (NOS).

Medical records were reviewed to evaluate for LRR, DM, OR, and BCM. LRR was defined as recurrent breast cancer in the ipsilateral chest wall, axilla, supraclavicular, or internal mammary LNs. All other sites of disease recurrence were considered DM. OR was defined as either LRR or DM, whichever occurred first. At last known follow‐up, vital status was recorded as alive with no evidence of disease, alive with recurrent disease, deceased from breast cancer, or deceased from other causes.

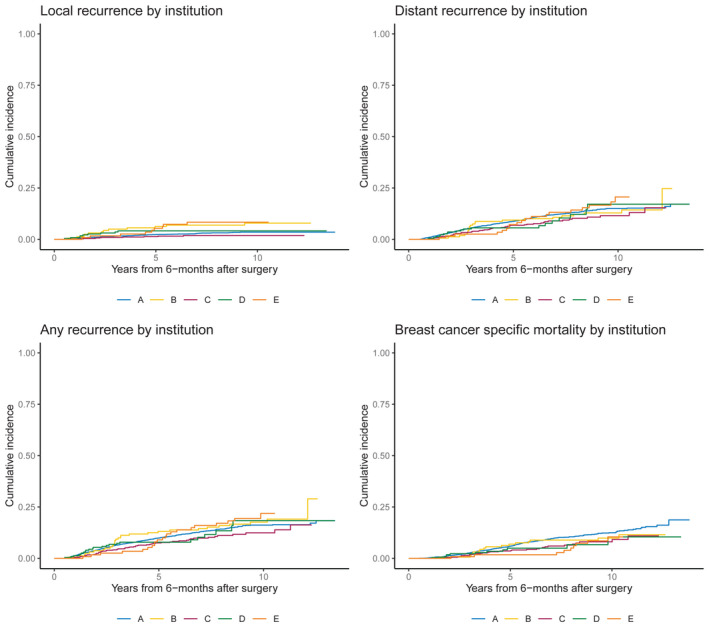

To ensure the multi‐institution data sets were appropriate for pooling, the primary outcomes of LRR, DM, OR, and BCM were compared by institution using cumulative incidence plots. Additionally, cross‐validation by institution was performed where data from four of the five institutions were used to build the model, then the discrimination was calculated on data from the fifth institution then repeated. Institution was anonymized and numbers at risk were suppressed for anonymity, as the goal was not to make inference based on these institution‐specific results.

Patient and disease characteristics were compared according to PMRT status using Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test for continuous variables. A landmark analysis approach was used for survival analysis, with follow‐up time beginning 6 months after the date of mastectomy to account for the standard time to receive adjuvant CHT and/or PMRT. The Fine‐Gray method was used to estimate cumulative incidence rates of LRR, DM, OR, and BCM, with deaths without the event of interest treated as a competing event. Competing risks regression models for each primary end point included predictors defined a priori including age, tumor size, grade, number of positive LNs, ratio of positive LNs to sampled LNs, LVI, ER/PR status, Her2 status, tumor location, PMRT, and use of optimal adjuvant systemic therapy. Tests for interactions between PMRT and each of ER‐status, Her2‐status, number of positive LNs, and tumor size were conducted, and any significant interaction effects were incorporated into the primary model.

Any missing data were imputed using multiple imputations with chain equation. The number of imputed data sets was increased for each end point of interest so that the absolute maximum prediction difference for any patient was <3%. The model of interest was then fit to each of the imputed data sets, and final estimates of the regression coefficients and their standard errors were obtained using Rubin's approach, 12 with predictions and estimates of the model performance obtained using the guidance of Marshall et al. 13 Model performance was assessed with the time‐dependent area under the receiver operator curve (AUC) to assess discrimination, and calibration plots of the predicted risk against the observed proportion, calculated based on subjects in deciles of the given predicted risk, using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing to assess calibration. Models were built on the full data, and the apparent performance metrics were obtained. Then, 100 bootstrap samples were used to obtain bootstrap cross‐validation performance metrics. The apparent and bootstrap cross‐validation discrimination were combined into a “.632 estimator” 14 of discrimination, with the bootstrap cross‐validation estimator taken as a minimum and the apparent estimator taken as a maximum, to give a range of model discrimination.

The final prediction model was then converted into an online calculator. Individual patient‐level predictions were generated from each of the imputed data sets, averaged after applying a complementary log–log transformation, and then transformed back to the original scale. Smooth adjusted plots according to PMRT status were created by applying a generalized additive model to the predicted risks across a range of time points. All statistical analyses were conducted in R software version 4.0.0 (R Core Development Team, Vienna, Austria), including the “mice” 15 and “riskRegression” 16 packages. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

There were 3532 patients eligible for analysis, of whom 2154 (61%) received PMRT. All outcomes had comparable cumulative incidence for each end point of interest across institutions (Figure 1). Cross‐validated discrimination values were overall similar for each institution for each end point (Table 1). As detailed in Table 2, patients receiving PMRT were significantly younger, had larger tumors, more positive LNs, and more frequently had LVI, ECE, positive margins, and received optimal systemic therapy. For the entire cohort, 814 (23%) underwent SLNB only, 1452 had SLNB followed by ALND (41%), and there was a median of 11 lymph nodes dissected (interquartile range [IQR], 5–16). Overall, 3136 patients (89%) received optimal systemic therapy. There were no significant interaction effects observed between PMRT and tumor size, number of positive nodes, ER/PR‐status, or Her2‐status for each end point of LRR, DM, OR, and BCM (p > .05 for all).

FIGURE 1.

Locoregional recurrence, distant metastasis, breast cancer mortality, and overall recurrence by institution.

TABLE 1.

Cross‐validated discrimination values by institution for LRR, DM, BCM, and OR

| De‐identified institution | LRR | DM | BCM | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.791 | 0.678 | 0.750 | 0.682 |

| B | 0.599 | 0.764 | 0.776 | 0.705 |

| C | 0.762 | 0.738 | 0.870 | 0.716 |

| D | 0.782 | 0.940 | 0.894 | 0.815 |

| E | 0.685 | 0.689 | 0.857 | 0.709 |

Abbreviations: BCM, breast cancer mortality; DM, distant metastasis; LRR, locoregional recurrence; OR, overall recurrence.

TABLE 2.

Patient and disease characteristics stratified by use of PMRT

| Characteristic | No PMRT (n = 1378) | PMRT (n = 2154) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y | <.001 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 59 (49, 70) | 53 (45, 65) | |

| Mean (SD) | 60 (14) | 55 (13) | |

| Pathologic tumor size, cm | <.001 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.5, 2.6) | 2.4 (1.7, 3.1) | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.11 (0.98) | 2.48 (1.07) | |

| Grade | <.001 | ||

| I | 183 (14%) | 219 (10%) | |

| II | 645 (48%) | 934 (44%) | |

| III | 516 (38%) | 986 (46%) | |

| Unknown | 34 | 15 | |

| Histology | .035 | ||

| Ductal | 1,077 (84%) | 1,604 (85%) | |

| Lobular | 120 (9%) | 187 (10%) | |

| Mixed | 83 (7%) | 79 (4%) | |

| Other | 4 (<1%) | 9 (<1%) | |

| Unknown | 94 | 275 | |

| No. of positive nodes | <.001 | ||

| 1 | 937 (68%) | 1,058 (49%) | |

| 2 | 341 (25%) | 660 (31%) | |

| 3 | 100 (7%) | 436 (20%) | |

| No. of sampled nodes | <.001 | ||

| 1–5 | 331 (24%) | 592 (27%) | |

| 6–10 | 279 (20%) | 559 (26%) | |

| 11–15 | 323 (23%) | 505 (23%) | |

| 16+ | 445 (32%) | 498 (23%) | |

| Axillary surgery type | <.001 | ||

| ALND | 434 (31%) | 832 (39%) | |

| SLN + ALND | 662 (48%) | 790 (37%) | |

| SLN only | 282 (20%) | 532 (25%) | |

| Clinical N stage | .6 | ||

| cN0 | 669 (71%) | 1,135 (70%) | |

| cN1 | 244 (26%) | 435 (27%) | |

| cN2 | 0 (0%) | 4 (<1%) | |

| cNx | 32 (3%) | 54 (3%) | |

| Unknown | 433 | 526 | |

| Pathologic N stage | <.001 | ||

| pN1 | 936 (68%) | 1,677 (78%) | |

| pN1mic | 398 (29%) | 280 (13%) | |

| pN1 NOSa | 44 (3%) | 197 (9%) | |

| Pathologic T stage | <.001 | ||

| pT1 | 734 (53%) | 831 (39%) | |

| pT2 | 637 (46%) | 1,323 (61%) | |

| pTx | 7 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | <.001 | ||

| Absent | 872 (65%) | 1,146 (55%) | |

| Present | 470 (35%) | 954 (45%) | |

| Unknown | 36 | 54 | |

| Extracapsular extension | <.001 | ||

| Present | 232 (17%) | 640 (30%) | |

| Absent/unknown | 1,146 (83%) | 1,514 (70%) | |

| ER/PR status | .060 | ||

| ER‐ and PR‐negative | 161 (12%) | 298 (14%) | |

| ER‐ or PR‐positive | 1,216 (88%) | 1,850 (86%) | |

| Unknownb | 1 | 6 | |

| HER2 status | .2 | ||

| Negative | 1,156 (84%) | 1,769 (82%) | |

| Positive | 222 (16%) | 385 (18%) | |

| Tumor location | <.001 | ||

| Central | 172 (15%) | 193 (11%) | |

| Inner | 184 (17%) | 287 (16%) | |

| Multiple | 220 (20%) | 424 (24%) | |

| Outer | 534 (48%) | 842 (48%) | |

| Unknown | 268 | 408 | |

| Margin status | <.001 | ||

| Negative | 1,351 (99%) | 2,063 (96%) | |

| Positive | 18 (1%) | 84 (4%) | |

| Unknown | 9 | 7 | |

| Optimal systemic therapy | 1,147 (84%) | 1,989 (93%) | <.001 |

| Unknown | 8 | 5 |

Note: Numbers presented are median (IQR) and mean (SD) as indicated for continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical values.

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; ER, estrogen receptor; IQR, interquartile range; PR, progesterone receptor; PRMT, post‐mastectomy radiation therapy; SD, standard deviation; SLN, sentinel lymph node.

pN1 with pN1mic and pN1 combined.

PR‐status only was unknown.

The landmark analysis for LRR excluded seven patients who were censored and eight patients who had LRR or died within 6 months of surgery, for a total sample size of 3517. With a median follow‐up time among those without LRR of 6.4 years (IQR, 4.2–9.2 years), 105 patients experienced LRR and 560 had the competing event of death without LRR. Overall, the 5‐year unadjusted cumulative incidence rates of LRR were 1.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.9–1.8) in the PMRT group and 4.3% (95% CI, 3.2–5.1) in the no PMRT group. On multivariable competing risks regression (Table 3), younger age (hazard ratio [HR], 1.02), larger tumor size (HR, 1.4), grade III (HR, 2.19), and 3 positive LNs (HR, 1.92) were all significantly associated with increased hazard of LRR. Receipt of PMRT (HR, 0.21) and optimal systemic therapy (HR, 0.32) were significantly associated with decreased hazard of LRR.

TABLE 3.

Multivariable competing risks regression for LRR, DM, OR, and BCM

| Variable | LRR | DM | OR | BCM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (per 1 y) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | <.001 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | .43 | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | .10 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | .14 |

| Tumor size (per 1 cm) | 1.40 (1.17–1.69) | <.001 | 1.34 (1.22–1.47) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.21–1.44) | <.001 | 1.37 (1.23–1.52) | <.001 |

| Grade (III vs. I/II) | 2.19 (1.41–3.42) | <.001 | 2.14 (1.70–2.69) | <.001 | 2.00 (1.61–2.49) | <.001 | 2.46 (1.87–3.23) | <.001 |

| No. of positive nodes (3 vs. 1 or 2) | 1.92 (1.20–3.08) | .007 | 1.50 (1.16–1.93) | .002 | 1.56 (1.23–2.00) | <.001 | 1.46 (1.08–1.97) | .013 |

| Nodal ratio | 1.21 (0.55–2.65) | .64 | 0.56 (0.33–0.94) | .029 | 0.64 (0.40–1.04) | .072 | 0.78 (0.43–1.40) | .40 |

| LVI (present vs. absent) | 1.23 (0.81–1.86) | .34 | 1.26 (1.03–1.55) | .026 | 1.26 (1.04–1.54) | .021 | 1.18 (0.93–1.51) | .17 |

| ER/PR+ vs. ER/PR– | 1.01 (0.57–1.79) | .97 | 0.80 (0.60–1.06) | .12 | 0.80 (0.61–1.05) | .11 | 0.58 (0.43–0.78) | <.001 |

| Her2+ vs. Her2– | 0.75 (0.43–1.31) | .31 | 0.60 (0.45–0.81) | <.001 | 0.63 (0.48–0.83) | .001 | 0.57 (0.41–0.79) | <.001 |

| Tumor location (inner vs. other) | 1.51 (0.89–2.54) | .12 | 1.39 (1.06–1.82) | .016 | 1.44 (1.12–1.85) | .005 | 1.48 (1.08–2.02) | .016 |

| Optimal systemic therapy (yes vs. no) | 0.32 (0.20–0.51) | <.001 | 0.45 (0.34–0.60) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.33–0.56) | <.001 | 0.41 (0.30–0.55) | <.001 |

| PMRT (yes vs. no) | 0.21 (0.14–0.31) | <.001 | 0.96 (0.77–1.19) | .69 | 0.76 (0.62–0.94) | .011 | 0.93 (0.72–1.20) | .57 |

Abbreviations: BCM, breast cancer mortality; CI, confidence interval; DM, distant metastasis; ER, estrogen receptor; HR, hazard ratio; LRR, locoregional recurrence; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; OR, overall recurrence; PMRT, post‐mastectomy radiation therapy; PR, progesterone receptor.

The landmark analysis for DM excluded seven patients who were censored and 13 patients who had DM or died within 6 months of surgery, for a total sample size of 3512. With a median follow‐up time among those without DM of 6.6 years (IQR, 4.3–9.3 years), 385 patients experienced a distant recurrence and 334 had the competing event of death without DM. The 5‐year unadjusted cumulative incidence rates of DM were 9.2% (95% CI, 7.9–10.1) in the PMRT group and 6.6% (95% CI, 5.2–7.7) in the no PMRT group. On multivariable competing risks regression (Table 3), larger tumor size (HR, 1.34), grade III (HR, 2.14), 3 positive LNs (HR, 1.50), LVI (HR, 1.26), and inner tumor quadrant (HR, 1.39) were significantly associated with increased hazard of DM. Her‐2‐positive status (HR, 0.60), higher nodal ratio (HR, 0.56), and receipt of optimal systemic therapy (HR, 0.45) were significantly associated with decreased hazard of DM.

The landmark analysis for OR excluded seven patients who were censored and 15 patients who had OR or died within 6 months of surgery, for a total sample size of 3510. With a median follow‐up among those without OR of 6.6 years (IQR, 4.3–9.3 years), 427 patients experienced OR and 319 had the competing event of death without recurrence. The 5‐year unadjusted cumulative incidence rates of OR were 9.6% (95% CI, 8.3–10.5) in the PMRT group and 9.2% (95% CI, 7.6–10.4) in the no PMRT group. On multivariable competing risks regression (Table 2), younger age (HR, 1.01), larger tumor size (HR, 1.32), grade III (HR, 2.00), 3 positive LNs (HR, 1.56), LVI (HR, 1.26), and inner tumor quadrant (HR, 1.44) were significantly associated with increased hazard of OR. Her‐2‐positive status (HR, 0.63), as well as receipt of PMRT (HR, 0.76), and optimal systemic therapy (HR, 0.43) were significantly associated with a decreased hazard of OR.

The landmark analysis for BCM excluded seven patients who were censored and five patients who died from other causes within 6 months of surgery, for a total sample size of 3520. With a median follow‐up among those without BCM of 6.6 years (IQR, 4.3–9.3 years), 293 patients experienced BCM and 328 had the competing event of death from other causes. The 5‐year unadjusted cumulative incidence rates of BCM were 5.8% (95% CI, 4.7–6.5) in the PMRT group and 4.7% (95% CI, 3.5–5.5) in the no PMRT group. On multivariable competing risks regression (Table 3), larger tumor size (HR, 1.37), grade III (HR, 2.46), 3 positive LNs (HR, 1.46), and inner tumor quadrant (HR, 1.48) were significantly associated with increased hazard of BCM. ER/PR‐positive status (HR, 0.58), Her‐2‐positive status (HR, 0.57), and receipt of optimal systemic therapy (HR, 0.41) were significantly associated with decreased hazard of BCM.

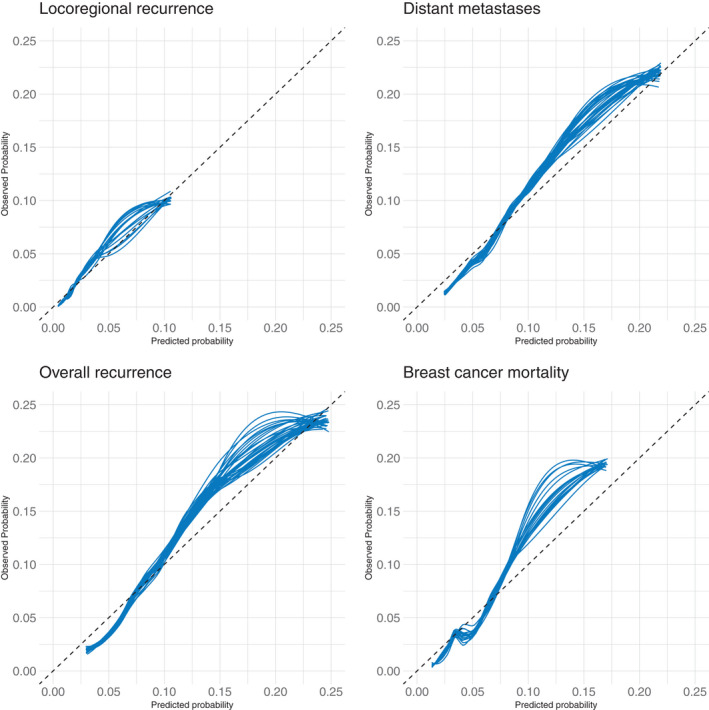

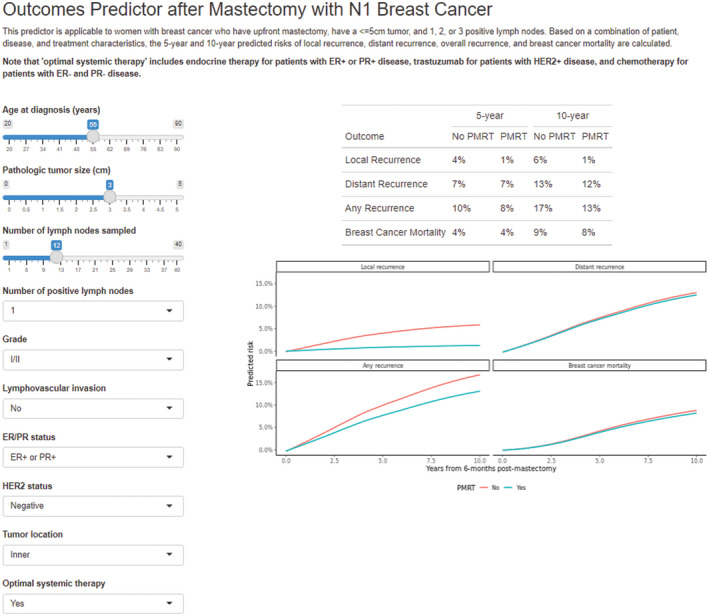

Model performance metrics for each end point showed good discrimination with “0.632 estimators” of 0.78 (95% CI, 0.73–0.83; bootstrap‐validation, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.71–0.82]; apparent, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.76–0.85]), 0.72 (95% CI, 0.67–0.75; bootstrap‐validation, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.66–0.75]; apparent, 0.73 [95% CI, 0.70–0.76]), 0.71 (95% CI, 0.67–0.74; bootstrap‐validation, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.67–0.74]; apparent, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.69–0.75]), 0.77 (95% CI, 0.73–0.81; bootstrap‐validation, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.72–0.81]; apparent, 0.78 [95% CI, 0.75–0.82]) for LRR, DM, OR, and BCM, respectively. Model calibration was good across most of the range of predicted risk, with a pattern of overpredicted risk in the higher range across all end points (Figure 2). An online calculator was created using the model to estimate predicted risks of each outcome with and without the receipt of PMRT and/or optimal systemic therapy based on individual patient and tumor characteristics (https://riskcalc.org/BreastPMRT) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Model calibration for locoregional recurrence, distant metastasis, overall recurrence, and breast cancer mortality.

FIGURE 3.

Example of online personalized risk assessment tool.

DISCUSSION

Because the precise indications for PMRT in pathologic stage T1‐2N1 breast cancer remain controversial, consensus guidelines acknowledge that there is insufficient evidence to endorse specific subpopulations in which PMRT can or should be safely omitted. 11 To our knowledge, this report represents the largest modern cohort examining the role of PMRT in pathologic stage T1‐2N1 breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy, providing a quantifiable estimation of the impact of PMRT on LRR, DM, OR, and BCM in the modern era. The models generated were used to create an online calculator to provide personalized estimates for individual patients regarding potential benefits of PMRT.

Although results of the SUPREMO trial are awaited, the present series provides some of the most robust data available in this controversial clinical setting. 17 Given the heterogeneity of this patient population, our risk calculator yields varying degrees of predicted benefit with the addition of PMRT with some women deriving small absolute benefits from radiotherapy, which may differ depending on their ability to receive optimal systemic therapy. In such cases where the expected benefit of PMRT is small, individualized management decisions must be balanced by careful consideration of the potential risks associated with PMRT, including lymphedema, pneumonitis, cardiac disease, and reconstruction complications, as well as the potential life expectancy for each patient. 18 , 19

The association of PMRT with decreased LRR (HR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.14–0.31; p < .001) found in this analysis is consistent with the known relative risk reduction from radiotherapy in prior studies. 3 Although the unadjusted rates of DM, OR, and BCM were similar between women receiving PMRT as those not receiving PMRT, patients selected to receive PMRT had significantly more adverse risk features and would be expected to have higher rates of DM and BCM as compared to more favorable groups. After adjusting for these risk factors, the addition of PMRT was associated with a decreased hazard of OR, predominantly by a reduction in LRR.

The primary strength of this study is the large sample size across multiple institutions thus making the results applicable to a diverse population. There is immense value in providing patients with more objective outcome data in this heterogeneous cohort regarding the absolute benefits of adjuvant PMRT based on individual patient and tumor factors. The calculator can provide an estimated risk of recurrence based on several variables, including receipt of adjuvant PMRT and systemic therapy.

There are limitations to this report, as with any retrospective study with inherent selection biases. First, patients were nonrandomly selected to receive PMRT or not, and although we accounted for factors associated with receipt of PMRT, there still may be unadjusted confounders with respect to treatment selection, including lack of underlying comorbidity data. The calculator may potentially overestimate future risks as outcomes continue to improve in the modern treatment era, in which genomic classifiers (that were not available for this study) will play a greater role. Additionally, many patients underwent complete ALND (36%) or SLNB followed by ALND (41%), and although our model includes both the number of positive LNs as well as nodal ratio, the risk estimates may differ for patients undergoing SLNB only, because only 23% of the cohort underwent SLNB alone. Furthermore, for patients receiving PMRT, information about radiation fields delivered were limited to the inclusion or not of regional nodal radiation and did not include whether or not internal mammary nodes were irradiated. Notably, inner quadrant tumor location was significantly associated with a higher hazard of DM, OR, and BCM—further study is warranted into adjuvant therapy decision‐making for axillary node‐positive disease in the presence of this risk factor.

As further stratification tools continue to be implemented into clinical practice, including biologic markers and genetic subtyping, 20 future studies are needed and ongoing 21 to further personalize the controversial indications for PMRT in this diverse patient population. Genomic testing has rapidly been incorporated into the decision‐making regarding adjuvant systemic therapy in women with breast cancer, and is now being studied for its value in potentially guiding adjuvant radiation therapy as well. 22 , 23 , 24 The currently enrolling MA.39 trial is incorporating the use of Oncotype Dx Recurrence Score as a stratification tool to hopefully better identify low‐risk patients where adjuvant radiation may be omitted. 21 Although we await the results of these potentially practice‐changing phase 3 studies, we present this large data set as a tool to assist in better stratification of patients and their risk of recurrence with and without PMRT. In this multi‐institutional analysis of over 3500 patients, PMRT for T1‐2N1 breast cancer was associated with a significant reduction in local and overall recurrence after accounting for known prognostic factors. An online calculator was developed (https://riskcalc.org/BreastPMRT) to aid patients and oncologists in estimating individualized predicted risks of recurrence to assist in personalized decision‐making regarding adjuvant therapy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sarah M.C. Sittenfeld: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, data analysis, and writing–original draft. Emily C. Zabor: Methodology, formal analysis, and writing–review and editing. Sarah N. Hamilton: Writing–review and editing, data curation, and resources. Henry M. Kuerer: Writing–review and editing, data curation, and resources. Mahmoud El‐Tamer: Writing–review and editing, data curation, and resources. George E. Naoum: Writing–review and editing and data curation. Pauline T. Truong: Writing–review and editing and resources. Alan Nichol: Writing–review and editing and resources. Benjamin D. Smith: Writing–review and editing and resources. Wendy A. Woodward: Writing–review and editing and resources. Tracy‐Ann Moo: Writing–review and editing and resources. Simon N. Powell: Writing–review and editing and resources. Chirag S. Shah: Writing–review and editing and resources. Alphonse G. Taghian: Writing–review and editing and resources. Ibrahim Abu‐Gheida: Writing–review and editing and data curation. Rahul D. Tendulkar: Conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, supervision, resources, and writing–review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Benjamin D. Smith received research funding from Varian, is a member of the ASTRO Board of Directors, and has current equity and royalty interest in Oncora Medical. Chirag S. Shah received grants from Varian Medical Systems, Vision RT, and PreludeDX and served as a consultant for ImpediMed, Evicore, and PreludeDX. Alan Nichol reported current research funding from Varian Medical Systems, Ltd for a clinical trial. Pauline T. Truongv reported writing fees and royalties from UpToDate, Kluwer Wolster Publishing. Alphonse Taghian reported royalties from UpToDate, payment for expert testimony, the submission of a provisionary patent, and borrowed SOZO equipment to conduct an investigation‐initiated study. Rahul Tendulkar reported honoraria from Varian Medical Systems. The other authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ragaz J, Olivotto IA, Spinelli JJ, et al. Locoregional radiation therapy in patients with high‐risk breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: 20‐year results of the British Columbia randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(2):116–126. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nielsen HM, Overgaard M, Grau C, Jensen AR, Overgaard J. Study of failure pattern among high‐risk breast cancer patients with or without postmastectomy radiotherapy in addition to adjuvant systemic therapy: long‐term results from the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group DBCG 82 b and c randomized studies. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(15):2268–2275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McGale P, Taylor C, Correa C, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10‐year recurrence and 20‐year breast cancer mortality: meta‐analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomized trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9935):2127–2135. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60488-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McBride A, Allen P, Woodward W, et al. Locoregional recurrence risk for patients with T1,2 breast cancer with 1‐3 positive lymph nodes treated with mastectomy and systemic treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;89(2):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luo C, Zhong X, Deng L, Xie Y, Hu K, Zheng H. Nomogram predicting locoregional recurrence to assist decision‐making of postmastectomy radiation therapy in patients with T1‐2N1 breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103(4):905–912. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muhsen S, Moo T‐A, Patil S, et al. Most breast cancer patients with T1‐2 tumors and one to three positive lymph nodes do not need postmastectomy radiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(7):1912–1920. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6422-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tam MM, Wu SP, Perez C, Gerber NK. The effect of post‐mastectomy radiation in women with one to three positive nodes enrolled on the control arm of BCIRG‐005 at ten year follow‐up. Radiother Oncol. 2017;123(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tendulkar RD, Rehman S, Shukla ME, et al. Impact of postmastectomy radiation on locoregional recurrence in breast cancer patients with 1‐3 positive lymph nodes treated with modern systemic therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(5):e577–e581. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Macdonald SM, Abi‐Raad RF, Alm El‐Din MA, et al. Chest wall radiotherapy: middle ground for treatment of patients with one to three positive lymph nodes after mastectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(5):1297–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Truong PT, Olivotto IA, Kader HA, Panades M, Speers CH, Berthelet E. Selecting breast cancer patients with T1‐T2 tumors and one to three positive axillary nodes at high postmastectomy locoregional recurrence risk for adjuvant radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1337–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Recht A, Comen EA, Fine RE, et al. Postmastectomy radiotherapy: an American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology focused guideline update. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2016;6(6):e219‐e234. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91(434):473–489. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1996.10476908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marshall A, Altman DG, Holder RL, Royston P. Combining estimates of interest in prognostic modeling studies after multiple imputation: current practice and guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Efron B, Gong G. A leisurely look at the bootstrap, the jackknife, and cross‐validation. Am Stat. 1983;37(1):36–48. doi: 10.2307/2685844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van Buuren S, Groothuis‐Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gerds T, Ozenne B. riskRegression: risk regression models and prediction scores for survival analysis with competing risks. https://github.com/tagteam/riskRegression. Accessed January 15, 2021.

- 17. Kunkler IH, Canney P, van Tienhoven G, Russell NS. Elucidating the role of chest wall irradiation in “intermediate‐risk” breast cancer: the MRC/EORTC SUPREMO trial. Clin Oncol. 2008;20(1):31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shumway DA, Momoh AO, Sabel MS, Jagsi R. Integration of breast reconstruction and postmastectomy radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(20):2329–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(11):987–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Woodward WA, Barlow WE, Jagsi R, et al. Association between 21‐gene assay recurrence score and locoregional recurrence rates in patients with node‐positive breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(4):505–511. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parulekar WR, Berrang T, Kong I, et al. Cctg MA.39 tailor RT: A randomized trial of regional radiotherapy in biomarker low‐risk node‐positive breast cancer (NCT03488693). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(suppl 15):TPS602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.TPS602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cardoso F, Van't Veer LJ, Bogaerts J, et al. 70‐Gene signature as an aid to treatment decisions in early‐stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):717–729. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nitz U, Gluz O, Christgen M, et al. Reducing chemotherapy use in clinically high‐risk, genomically low‐risk pN0 and pN1 early breast cancer patients: five‐year data from the prospective, randomized phase 3 West German Study Group (WSG) PlanB trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;165(3):573–583. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4358-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalinsky K, Barlow WE, Gralow JR, et al. 21‐Gene assay to inform chemotherapy benefit in node‐positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(25):2336–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]