Abstract

NMR is a very powerful tool for identifying and quantifying compounds within complex mixtures without the need for individual standards or chromatographic separation. Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (or SIRM) is an approach to following the fate of individual atoms from precursors through metabolic transformation, producing an atom-resolved metabolic fate map. However, extracts of cells or tissue give rise to very complex NMR spectra. While multidimensional NMR experiments may partially overcome the spectral overlap problem, additional tools may be needed to determine site-specific isotopomer distributions. NMR is especially powerful by virtue of its isotope editing capabilities using NMR active nuclei such as 13C, 15N, 19F and 31P to select molecules containing just these atoms in a complex mixture, and provide direct information about which atoms are present in identified compounds and their relative abundances. The isotope-editing capability of NMR can also be employed to select for those compounds that have been selectively derivatized with an NMR-active stable isotope at particular functional groups, leading to considerable spectral simplification. Here we review isotope analysis by NMR, and methods of chemoselection both for spectral simplification, and for enhanced isotopomer analysis.

Keywords: Stable isotope resolved metabolomics, Isotopomer distribution analysis, chemoselection

1. Introduction

Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM) is designed to determine the position and enrichment of specific isotopes in metabolites following labeling with isotope-enriched precursors (1–3). Mass spectrometry and NMR via isotope distributions provide direct information about metabolic transformations of the precursors, and therefore about the specific pathways that are involved or impacted by treatment (3–5) and as a prerequisite for flux analysis (6). Different labeled precursors can be chosen to focus on particular pathways in the metabolic network, for example glucose utilization in glycolysis (7,8) and glycogen synthesis (9), the pentose phosphate pathway and the Krebs cycles, versus glutamine utilization (both carbon and nitrogen) in the Krebs cycle and nucleobase synthesis (10). Extracts of cells or tissues give rise to very complex NMR spectra, that are only partially alleviated by two or three dimensional experiments. However, NMR is especially powerful by virtue of its editing capabilities using NMR active nuclei such as 13C, 15N, 2H and 31P to select molecule containing just these atoms in a complex mixture, and provide direct information about which atoms are present and their relative abundances.

The isotope-editing capability of NMR can be further exploited to select molecules that have been derivatized with a compound containing a specific NMR active stable isotope. Derivatization of organic molecules to enable analysis has a long history (11–14). There have been many metabolomics studies using GC-MS where derivatization with silyl groups is required to make the metabolites sufficiently volatile (15,16). Most of these derivatizations have been used to maximize coverage, and rely on the presence of so-called active hydrogen (15). Derivatization has also been used for chemoselection, in which only molecules bearing particular functional groups are derivatized. If isotope-enriched derivatizing reagents are used, it is possible to detect just those derivatized compounds in a highly complex mixture (3,17). Functional groups that have been targeted for this chemoselection approach include amino groups (18,19), aldehydes and ketones (20,21), carboxylate (22–24), hydroxyls (25–27) (Lin et al., unpublished), thiols (28), amino lipids (29) and even phosphates (18).

Derivatization for NMR applications has been less widespread, in part because NMR does not require chromatography, and 1H NMR detects essentially all non-labile protons in molecules, if present at sufficient abundance (typically > 1 nmol, (30)). Even readily exchangeable protons can be detected under specialized conditions (pH, low temperature) (31) or using non-aqueous solvents (32). The sensitivity of other common biologically relevant isotopes is very much lower than for 1H, making 1H detection preferred. Even where a molecule is 13C or 15N enriched, 1H detection via scalar coupling is still superior compared to direct detection of these isotopes. It usually provides the same information at the same time with a much stronger signal due to the large gyromagnetic ratio of the proton. Further, recent studies have demonstrated the value of 2H NMR because of its low background, and rapid acquisition (7) (9). Nevertheless, the isotope-editing capabilities of NMR make derivatization attractive for specific classes of compounds, and can be compatible with isotopomer distribution analysis (or SIRM) (24,33,34). Here we focus on isotope-editing and derivatization approaches used with NMR-based metabolomics with a particular emphasis on determining positional stable isotope enrichment.

2. Positional isotopic enrichment via isotope editing

2.1. Effect of stable isotopes on NMR spectra

A 1H NMR spectrum of a complex mixture such as an extract from cells or tissues contains signals from every proton in each molecule present above the detection limit of the spectrometer. With modern spectrometers, this is of the order 1 nmol to achieve an SNR of 10:1 in 15 minutes of acquisition (34). For mammalian cells, this amount of compound would correspond to approximately to 106 cells at a concentration of 1 fmol/cell, or of the order mM, which encompasses most of the intermediates of central metabolism including glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, amino acids, nucleotides, dinucleotides and nucleotide sugars and several other abundant compounds. The resulting 1H NMR spectrum is therefore very complex and overlapping, making identification and quantification of many metabolites problematic. This problem is exacerbated in the presence of NMR-active stable isotopes, which leads to further splitting of the 1H resonances.

Multidimensional NMR improves resolution at the cost of absolute quantitative precision and increased experimental time. NMR is unique in its ability to edit complex spectra by selecting for particular NMR-active isotopes or combinations of isotopes (3,35,36). As NMR detects only certain isotopes such as 13C (but not 12C), 15N, 31P, 19F, compounds that are enriched in these isotopes can be specifically selected for by NMR editing, which leads to considerable spectral simplification and ease of compound identification. A suite of experiments can be applied to provide a complete isotopomer distribution pattern even in multiplexed labeling schemes, such as 13C, 15N-Gln (3).

Detection and quantification of positional labeling of metabolites following administration of a stable-isotope enriched precursor to cells or organisms can be achieved using a variety of NMR methods, either by indirect detection of protons interacting with the labeled atom via scalar coupling (e.g. 13C, 15N) or by direct detection (e.g. 13C).

Resonances of protons directly attached to 13C are split by the 1JCH coupling into a doublet ± 1JCH (i.e. satellite peaks) on either side of the proton resonance when attached to 12C. Resolution permitting, this provides the simplest method for determining site specific labeling, F, as:

where A is the peak area. This assumes either a sufficiently long relaxation delay such that all resonances are relaxed, or corrections are made for differential T1 relaxation (33,34). The precision of value of F which ranges between 0.011 and 1.0 if no natural abundance correction is made, is determined by the reliability of the integration method which is probably best achieved using line fitting function with least squares and local baseline correction, as is common in commercial NMR software packages.

2.2. Isotopomer distributions by indirect detection NMR

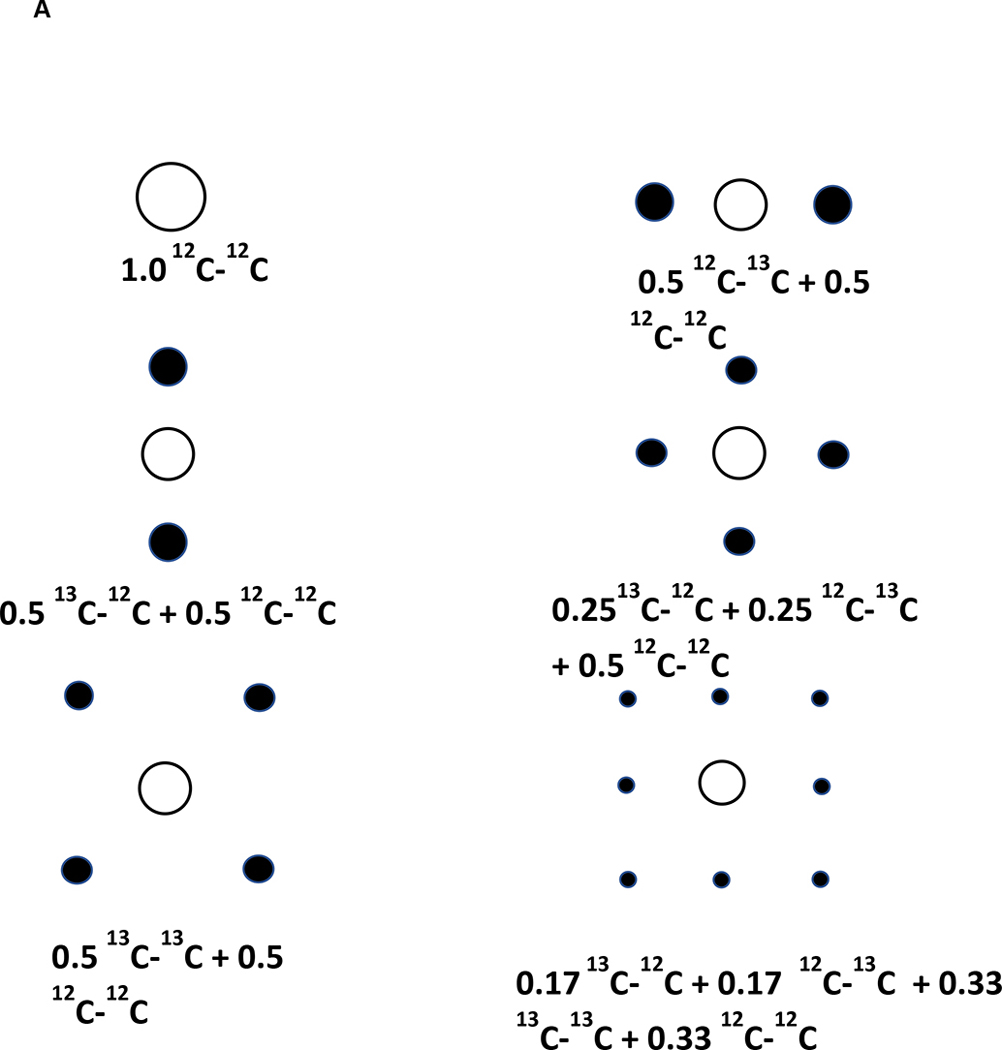

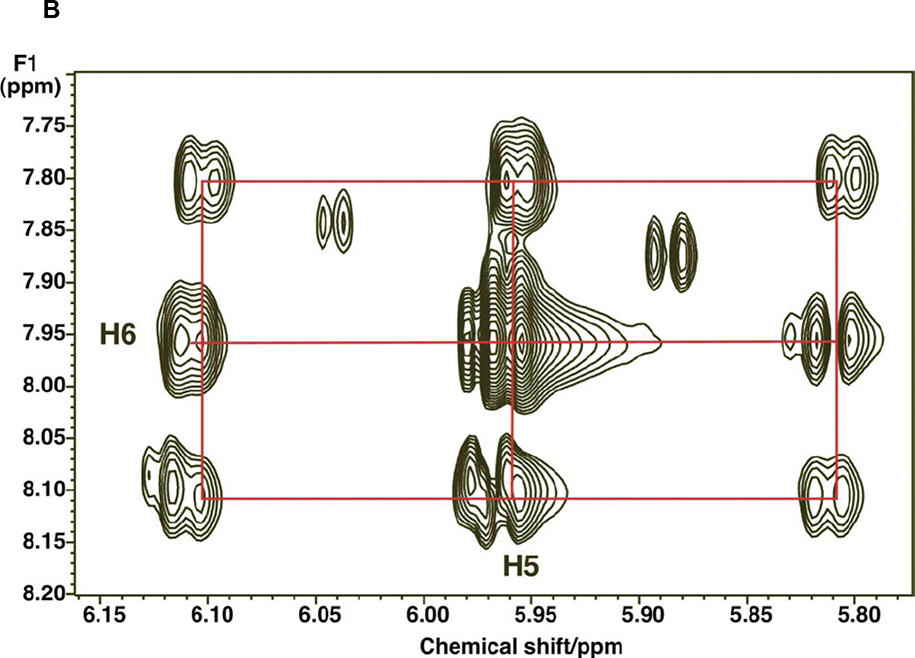

Absolute site-specific fractional enrichment can be determined using indirect detection, as the proton attached to 13C is split into satellite peaks which can be quantified. Using TOCSY, it is possible to determine from the satellite splitting patterns the isotopomer distributions and site specific enrichments in metabolites in complex mixtures, including multiple isotopomers which generate distinguishable patterns as shown in Fig. 1A (3,33). Site specific quantification is carried out as in 1D, except that now volume integration must be carried out, which requires careful adjustment of the phases in both dimensions and base-plane correction, and adequate digitization. We usually record TOCSY spectra of extracts using an acquisition time in t2 of 1 sec, and at least 50 ms in t1. With care, the 13C isotopomer fractions can be accurately determined even at natural abundance (33). The experimental spectrum in Fig. 1B shows a detail of a TOCSY experiment performed on an extract of cell grown in the presence of [U-13C]-glucose. Glycolysis converts the glucose to 13C3 pyruvate, which is then decarboxylated by PDH to produce 13C2 acetyl CoA, which condenses with unlabeled oxaloacetate to produce 13C2 citrate. Oxidation of the citrate through the Krebs cycle produces 13C2 fumarate, at both C1C2 and C3C4, in equal amounts (as fumarate is a symmetric molecule. Addition of water across the double bond of fumarate by fumarate hydrates produces two distinguishable isotopomers of malate, namely 13C113C212C312C4, and 12C112C213C313C4 in equimolar amounts. Malate can be oxidized and transaminated to aspartate which is the immediate precursor of uracil, producing an equimolar mixture of 13C612C5 and 12C613C513C4 uracil, which account for the two singly labeled species of UXP observed. The doubly labeled species, 13C613C5, can be created either by a second turn of the Krebs cycle, or by pyruvate carboxylation. The distinction between these possibilities can be made by isotopomer analysis of citrate and glutamate, as the isotopic labeling patterns for these compounds are quite distinct for these mechanisms (17,37). This serves as an example of the power of isotopomer distribution analysis for determining the relative importance of different pathways in complex metabolic networks.

Figure 1.

Simulated and experimental splitting patterns in TOCSY and HCCH-TOCSY for a HCCH fragment

A. TOCSY cross peak patterns expected for HCCH with different isotopomers as displayed on the figure. The area of each satellite is proportional to the fraction of each isotopomer present.

Open circle is 12C, filled circles are 13C. [Adapted from Lane et al. (81)

B. TOCSY spectrum showing 13C satellites at C5 and C6 in the uracil ring of UXP in an extract of LnCap cells grown in the presence of [U-13C]-glucose for 24 h. The pattern corresponds to a mixture of unlabeled 12C512C6, 13C512C6, 12C513C6 and 13C513C6 isotopomers. From Figure 4B of (82) licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),

C. HCCH-TOCSY cross peak patterns expected for HC1-C2H-C3H with different isotopomers as displayed on the figure. Cross-peaks are observed only when adjacent carbons are both 13C, i.e. have a significant 13C-13C coupling (typically 35–50 Hz). Open circles represent diagonal peaks, filled circles cross peaks.

Several other 2D experiments can be used to edit for specific isotopomer distributions, for example HCCH-TOCSY which provides direct evidence of adjacent 13C sites in the same molecule (Figure 1C), or HACACO for detection of simultaneous 13C labeling at the carbonyl and adjacent carbon via the attached proton (38) (3), and HMBC for carbonyls via long range coupling (2JCH, 3JCH), which has lower sensitivity.

Similar heteronuclear experiments can be applied to 15N detection. As the γ(15N) is only 0.1 γ(1H), indirect detection is in practice necessary. The 1JNH≈90 Hz in amides making the 1H{15N} experiment very sensitive, though exchange for 2H in D2O solvent greatly attenuates the signal. Amides are kinetically most stable at around pH 4.5 and can be readily observed in 1H2O using modern methods of water suppression. The nucleobases are synthesized using the amido and amino N for Gln. If 15N Gln is used as the precursor, incorporation into purine rings can be detected simply using 1H{15N} HSQC with the 1/2J delay tuned to the modest (≈10 Hz) 2-bond coupling between H8/N9 and (for Ade) H2/N1 as well as H2/N3 which derives from the amino group of Asp. Indirect detection of 15N using 15N2Gln as the source at N1 implies that Asp received its amino group by transamination of Glu (17).

Detection of amino groups is more challenging. However, at low pH and reduced temperature (5–10°C), the ammonium protons of amino acids have sufficiently slow exchange to by observed in 1H{15N}-HSQC. In an early example of a dual labeling using 15NH4+ and 13C-acetate precursors in rice coleoptiles, the 1H{15N}-HSQC-TOCSY experiment selected for molecules 1-bond N-H coupling (ca. 80–90 Hz). Incorporation of 13C at the 3 position of GABA showed 13C satellites in the proton dimension, equivalent to >50% 13C enrichment in the 15N labeled molecule (39).

2.3. Isotopomer distributions by direct detection NMR

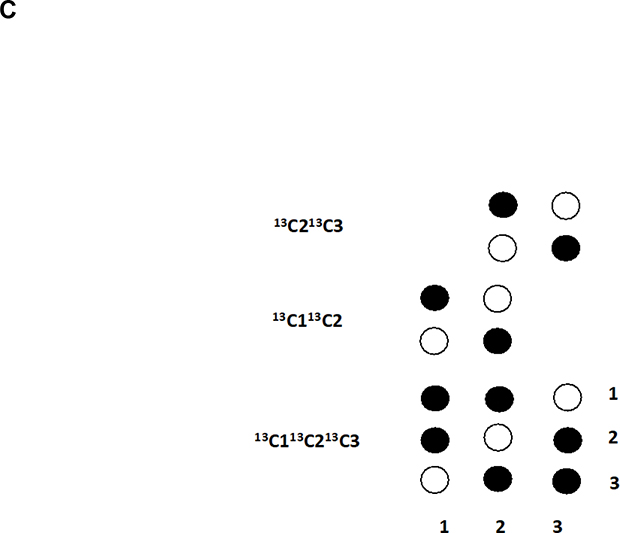

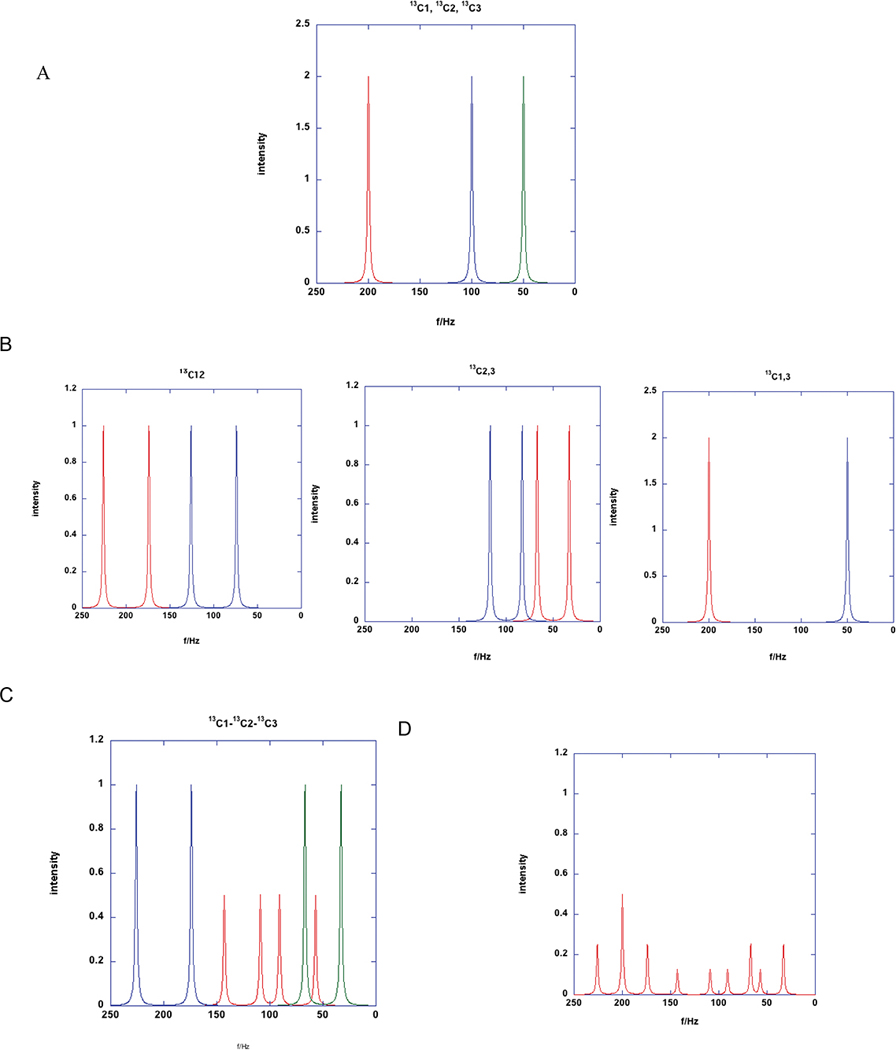

Direct detection of 13C relies on the chemical shift and scalar 13C-13C coupling patterns (in multiply labeled compounds) to determine the isotopomer distribution. Figure 2 shows expected patterns in 13C spectra of a 3-carbon molecule such as Alanine or lactate. In the absence of metabolic labeling, the spectrum simply shows the natural abundance (1.1%) of 13C and is thus very insensitive. Such a spectrum shows three singlet resonance corresponding to each carbon, assuming proton decoupling was applied, as is commonly the case. If the molecule becomes isotope-labeled by metabolic transformation of the precursor compound, one or more of the individual resonances increases in intensity, proportional to the enrichment. If there is more than one 13C atom, then in addition to the chemical shift (position) information, there may be scalar coupling between adjacent 13C atoms, causes a splitting of 35–55 Hz. This additional splitting can be analyzed to determine the isotopomer distribution (but not the absolute fractional enrichment at each position), as shown in Figure 2. Where multiple isotopomers are present, the resulting spectrum is the superposition of the spectrum of each isotope, which can be analyzed to determine the relative abundance of each one (40–42). Because of the variable NOEs from the attached protons, and often long T1 values of carbonyls or quaternary carbons, care has to be taken to account for these effects on signal intensity quantification, such as using a gated decoupler experiment (no NOE) and a long relaxation delay with a further compromise in sensitivity.

Figure 2. 13C coupling patterns in a 3-carbon fragment.

The expected splitting patterns in 13C NMR for a molecules such as alanine were calculated for 1JC1C2 = 52 Hz and 1JC2C3= 34 Hz. The small 2JC1C3 ≈2 Hz was ignored. C1 was at f = 200 Hz, C2 at f=100 Hz and C3 at f=50 Hz. The line width was set to 2 Hz.

A. Singlets corresponding to only one 13C at position 1 (red), 2 (blue) or 3 (green)

B. Two 13C at C1C2, C2C3 and C1C3

C. All three 13C atoms simultaneously labeled

D. Mixture of isotopomers. 25% 13C1+ 25% 13C113C2 +25% 13C213C3 + 25% 13C113C213C3

Similar information can be obtained using the large 1JCH in HMQC or HSQC experiments, which substantially increases sensitivity owing to the much higher γ of the detected proton, at the expense of not detecting non-protiated carbons. If sufficient resolution is obtained in the 13C dimension, the 13C-13C splitting patterns can be determined (3,43), providing the same information as the directly observed 13C spectrum, with the additional information about biochemical identity from the 1H chemical shift. However, quantification is complex owing to the non-uniform 1JCH values and spectral distortions in F1. Therefore for quantitative analysis, additional experiments may be required (44). However, the splitting patterns in F1 can provide information about relative enrichment if both the carbonyl and the adjacent carbon are 13C enriched, and by careful analysis, the relative proportion of 13C-13C versus 12C-13C can be determined.

2.4. 31P selection

A substantial fraction of metabolites of central metabolism are phosphorylated (cf the intermediates of glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, nucleotides, nucleotide hexoses and the redox dinucleotides) and are therefore crucial to determining the energy status of cells. 31P is essentially 100% abundant, and has a gyromagnetic ratio approximately 40% of that of 1H. It is straightforward to select based on 31P, either by direct detection, or indirect direction by the (usually) three bond couplings to the phosphorylated carbon. The chemical shift of 31P alone is often inadequate for rigorous assignments, so techniques that correlate 31P and 1H chemical shifts, with magnetization transfer along the protiated carbon backbone are used (45,46). If these carbons are also enriched, then the protons will be split by the passive 1JCH coupling, from which site-specific enrichment can be determined in just the phosphorylated compounds present in a mixture, as for the 15N-1H experiments described above.

2.5. Lipid analysis by NMR

With isotope labeling, not only the specific functioning groups information can be extracted, but also the overall profile of integration from a specific source. We demonstrated the flow of 13C from uniformly labeled glucose as well as glutamine into lipids de novo synthesis and overall profile of the lipids composition after 24 hours of culture of the in two different cell lines (PC3 and UMUC3) (47). This new approach provides a bird-eye like view for the whole lipid groups. Instead of identifying and quantifying individual lipid species, it focused on the enrichment of certain types of carbons in the whole lipid family, such as terminal methyl groups, double bonds in the lipid chain, glycerol backbone, etc. By acquiring both 2D TOCSY and 1H-13C HSQC data, referencing to the choline which is at natural abundance, quantification of low levels of 13C enrichments at multiple lipid sites was achieved.

3. Chemoselective derivatization strategies for NMR

Chemoselection seeks to derivatize specific functional groups, and use the resulting adducts for selection, either physically as in LC-MS, or magnetically by NMR. Functional groups commonly found in metabolites are amino, amido, aldehyde and ketone, carboxylates, thiol, hydroxyl and phosphoryl groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Target functional groups and derivatization products

| Functional group | Derivatizating Agent | product | Detection Method | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acetic anhydride |

|

HSQC by 2JCH | (51) |

Formic acid |

|

HSQC by 1JCH | (52) | |

|

|

19F NMR | (53) | |

|

|

19F NMR | (54) | |

|

|

19F NMR | (54) | |

|

QDA |

|

HSQC by 2JNH, 3JNH | (20,83) |

|

2-chloro-4,4,5,5-tetramethyldioxaphospholane |

|

1H, 31P HSQC | (75) |

|

ethanolamine |

|

HSQC by 1JNH | (59) |

cholamine |

|

HSQC by 1JNH, (2JCH, 1JNCO, 2JNCA) | (84,85) | |

2-chloro-4,4,5,5-tetramethyldioxaphospholane |

|

(75) | ||

|

|

DATAN |

|

1H | Lin et al. unpublished |

2-chloro-4,4,5,5-tetramethyldioxaphospholane |

|

31P HSQC | (75) | |

|

|

N-ethylmaleimide |

|

1H | (74) |

3.1. Applications of amino derivatization

Amino acids are not only the building blocks of proteins, but also play important roles in signaling processes that regulate important physiological activities such as protein synthesis (mTOR, (48)) or neural activity (GAB, Glu etc. (49)). They are also alternative energy resources and nitrogen sources in many key metabolomic processes. The presence and changes in the concentrations of amino acids in certain biofluids are indicators of many vital physiological activities and pathological conditions (50). However, traditional 1H NMR of these amino acids in biofluids often suffers from severe signal overlap due to structural similarities as well as huge dynamic range differences, hindering their identification and quantification. Several methods have been reported using derivatization agents to enhance the amino acid detection and quantification as alternatives to direct 1H NMR analysis.

3.1.1. Acetylation with 13C acetic anhydride

The amine groups can be directly acetylated in aqueous media with 1,1 −13C2 acetic anhydride that creates a high sensitivity and quantitative label in complex biofluids such as serum and urine with minimal sample preparation requirements (51). Upon 13C labeling on the specific groups on the amino acids, both 1D or 2D 13C NMR experiments can now be readily applied for producing highly resolved spectra with improved sensitivity. By applying this method, the authors successfully acquired the amino acid profiles of the urine from patients having different metabolomic disorders, facilitating the diagnosis of these diseases. Note that this method acetylates not only the amino group in the amino acids, but also reacts with hydroxyl groups in various metabolites, further broadening the application horizon of metabolites identification but at the same time, introducing spectral complexity. A similar strategy was also proposed by utilizing 13C-formic acid (52), which was first activated by conversion to NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimidyl) ester and then reacted with the amino group to form the peptide R-N-13C(O)H. The large 1JCH is then suited for detection by 1H-13C HSQC detection. This one bond coupling provides a substantial sensitivity advantage over the small three bond H-N-CO-C coupling available in the acetic anhydride. Volume integration of these spectra can be used to quantify the amino acid by comparing with an internal amino group bearing standard at known concentration.

3.1.2. Incorporation of 19F for selective detection.

19F is essentially 100% abundant and has gyromagnetic ratio 0.94 of a proton, so that it is a relatively cheaper option for tagging compounds, albeit potentially having greater effects on metabolism than isotopic substitution. In one study (53), o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) was used in combination with CF3 bearing thiols as derivatization agents to produce 2-(trifluoromethyl)-benzenethiol labeled amino acid where the R group from the amino acids is spatially close to the CF3 group, resulting a small chemical shift effect on the 19F resonances for different derivatized amino acids. Amino acid mixtures of 17 different types were derivatized using three different types of CF3-benzenethiols (2-, 3-, and 4-) to evaluate the effect of amino acid on the chemical shift and it was found that all CF3-labeled amino acids were distinguishable in the 19F spectra except Pro. By comparing the derivatized mixture spectrum with the spectrum of each individual amino acid derivatized with 3-CF3-benzenethiol, the peaks could be assigned and quantified, and showed good linearity in the 0.1 to >10 mM range for glycine. In a similar study (54), two different 19F containing tags (CF and CF3), both of which contain the N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (NHS) unit, were reported for amino group labeling. The chemical environment surrounding the 19F reporter group in the product depends on the side chain of the amino acid reacted with the tag. Thus the chemical shift of the 19F was finely tuned by each individual amino acid bearing a slightly different side group. The two reporter F groups resonance at very distinct frequency ranges so that they also compensate each other in occasional cases where the F resonances from two different amino acids overlap in one spectrum. The peak heights in the F spectra with both tags also showed excellent linearity versus the concentration of the amino acids. The 19F tags were applied in two biological samples, FBS and E. coli lysates, both of which yielded good identification and quantification data.

3.2. Applications of carbonyl derivatization

Carbonyl (aldehydes and ketones) are common in numerous classes of metabolites, including ketone bodies, carbohydrates and lipid oxidation products. Another method targeting tertiary carbons was developed by reacting with an aminooxy probe (QDA) which specifically reacts with carbonyl groups (keto and aldehydes) but not carboxylates (55,56). The aminooxy group binds to the free keto or the aldehyde to produce ketoxime and aldoxime, respectively. The 2-bond and 3-bond scalar coupling between the 15N from the aminooxy probe and proton from the aldehyde or keto group could be detected by the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum, which results in a unique cross peak for each aldehyde or keto carbon (21). The H-N coupling constants of aldehydes 2-bond and ketones 3-bond were determined to be around 2.1± 0.2 Hz and 2.6 ± 1.1 Hz, respectively. Due to the structural differences of the QDA adducts of aldehydes and ketones, the chemical shifts of the 1H and 15N showed strong correlations and can be readily distinguished by either characteristic chemical shift (21).

3.3. Applications of carboxylate derivatization

Carboxylates are essentially present in all major metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, TCA cycle, pentose phosphate pathway, urea cycle, β-oxidation, gluconeogenesis, etc. Some of those are considered biomarkers for smoker identification (57), hazardous material exposure history (47) as well as cancer diagnosis (58). However, due to the lack of protons in the carboxylate group, it was a group of forgotten metabolites by traditional NMR methods in the metabolomics studies. Even with 13C isotope labeling, the long relaxation time (usually in minutes) and small range of chemical shifts make it hard to be directly studied by 13C NMR. However, with isotope labeling tag reacting with the carboxylate, the more sensitive tag signal can be accessed due to the connecting group from the carboxylate, which indirectly reports the chemical environment of the carboxylate group. One such study is using 15N-ethanolamine as the derivatization agent (59) where all carboxylate groups are chemically linked to the agent to form a peptide bond structure. The proton on the 15N amide group can be assessed by NMR through one bond heteronuclear coupling which eliminates all other proton species, resulting in a cleaner spectrum. The large one-bond coupling constant recruited in this experiment ensures a more efficient polarization transfer comparing to long-range coupling used in the 13C acetylation of amino groups, where non-specific noises arise. By comparing the 1H-{15N} HSQC spectrum of the derivatized biological sample extracts with those of derivatized standards, the cross peaks in the spectrum can be readily assigned. Using this methods, the author successfully detected nearly 200 different species of carboxyl group bearing metabolites, of which 22 were identified by comparing to the standard spectrum.

A similar approach was also reported to tag carboxylates utilizing 15N-Cholamine as the tagging agent (22). Cholamine shares structure similarity with ethanolamine where the hydroxyl group was replaced with a tertiary amine with three methyl groups. This structure provides good solubility of the tagging product in aqueous NMR solution and retains wide chemical shift dispersion of the tagged metabolites. The positive charge that the tertiary amine possessed also facilitates MS detection. Using similar strategies, the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the derivatized biological samples can be assigned against the spectrum of derivatized carboxylates standards. Based on these, Vicente et al. (60) took a step further and applied this method into 13C stable isotope tracer labeled biological samples to demonstrate its application of identifying and quantify 12C and 13C carboxylate species. By analyzing the 2D cross peak patterns formed in the 1H-{15N} HSQC spectrum, the different combination of nature abundance 12C and isotope labeled 13C species of certain metabolites can be deconvoluted and quantified separately. By acquiring the two different 2D planes of the 3D spectrum HN(CO) and H(N)CO, only the metabolites with 13C label on the carboxyl groups can be revealed, further simplified the spectrum for metabolites identification.

3.4. Applications of hydroxyl derivatization

Hydroxyl groups are present in a wide range of compounds including carbohydrates (Fig. 2), amino acids (e.g. Thr, Ser, Tyr), steroids and α-hydroxycarboxylates such as lactate, malate and 2-hydroxyglutarate. The latter exist as enantiomers, which are produced by different enzymes with different stereospecificities. 2-hydroxyglutarate is known as an oncometabolite (61,62), and the R,S forms are created by different enzymes (63–67). L-lactate is synthesized from pyruvate by LDH in lactic fermentation whereas D-lactate is a bacterial product associated with short bowel syndrome (68). Thus both detection and quantitation of the enantiomeric form is desirable. The hydroxyl group of 2HG can be derivatized using chiral reagents generating the corresponding diastereomers which can be separated by chromatography (25,26,69,70), or directly by NMR (Lin et al. submitted) used DATAN derivatization with 1H NMR detection to determine the enantiomeric purity of lactate, malate and 2HG under various conditions. The compounds were readily quantified, and diastereomers resolved by COSY including in an IDH2 variant renal cell carcinoma that produces high quantities of 2HG (71) that showed predominantly the D enantiomer, consistent with that expected for variant IDH2.

3.5. Applications of thiol derivatization

Numerous important metabolites contain a free sulfhydryl functional group including free cysteine (Fig 1), cysteine containing compounds such as glutathione and proteins, homocysteine and S-adenosyl homocysteine and Coenzyme A. Free thiols readily react with numerous reagents such as iodoacetamide, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), p-chloromercuribenzoic acid (PCMB) and QDE (72) forming adducts that have favorable properties for detection and quantification.

The absolute concentrations and the GSH/GSSG ratio is an important readout of the redox state of cells, especially for oxidative stress (73). However, GSH can be easily oxidized to GSSG and many of the 1H resonances of GSH and GSSG are coincident, making it difficult to accurately determine the GSH/GSSG ratio by 1H NMR. Gowda et al. (74) used the thiol-reactive compound N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to derivatize GSH, which does not react with GSSG. The derivatization of the free sulfhydryl group prevents the oxidization of GSH to GSSG, thus providing a means for more accurate quantification of GSH and GSH/GSSG ratio. However, this derivatization also created two equimolar diastereomers of GSH-NEM, of which the distinct ethyl-methyl group chemical shifts (around 1.132 ppm) are well separated from those of GSSG, making it easily quantifiable. The derivatization and quantification were demonstrated in human whole blood extracts, showing that without derivatization, one could easily overestimate the abundance of oxidized GSSG. However, in a more crowded NMR spectra of cell or tissue extracts, this peak might still overlap with other methyl peaks. A solution might be to derivatize the cysteine thiol of GSH with a 13C-containing derivatizing agent, and select by HSQC.

3.6. Non-polar metabolite derivatization

These isotope labeling schemes are not limited to only polar metabolites. DeSilva et al. (75) reported a 31P labeling on the lipids containing hydroxyl, aldehyde and carboxyl groups via CTMDP (2-chloro-4,4,5,5-tetramethyldioxaphospholane). It is shown that the derivatized lipophilic compounds are well resolved in the 31P spectrum with unique resonances. The identification of different species of lipid molecules from the 31P spectrum is comparable to those from the traditional 1H spectrum. The quantification from triplicate samples showed good consistency in the 31P spectra. The advantage of applying 2D 1H-31P experiment is that it provides better resolution in highly overlapped regions in the proton spectrum.

4. Conclusions and Future developments

Because of the isotope editing capabilities, and the wide range of experiments that can be applied to extract specific kinds of isotopomers (3), NMR is well suited for quantitative isotope analysis of complex mixtures. Nevertheless, spectral overlap, particularly for carbohydrates, limits the metabolic coverage attainable. Chemoselection is one approach to overcoming this limitation, by selecting for one kind of functional group. There are now derivatizing agents for most the common functional groups present in metabolites (cf Table 1). Further effort in producing 13C or 15N enriched version for isotope-editing of the derivatized molecules.

For example, derivatization of amino groups with 13C formic acid (Table 1) produces a peptide with sensitive detection via the 1JCH. If the amino group is enriched in 15N, for example by transamination of 15N glutamate via, then the 13C will be split in F1 by the 1JNC coupling of 8–10 Hz. Similarly, DATAN derivatization of hydroxyls could be made selective by incorporation of 13C at one of the protiated carbons. Iodoacetamide is an efficient and selective thiol reagent and using 13C at C2 would allow selection of thiol compounds using the 1JCH.

It is also important to choose the site(s) of enrichment so that isotopomer distributions can be determined in an isotope-edited chemoselection experiment, as described for cholamine (60) and QDA (21). The sensitivity of the cholamine derivatized compounds would be further enhanced by deuteration at C1, which would remove the 3-bond coupling to the detected amide proton in the adduct (Table 1).

Although L-amino acids dominate in mammalian systems, the D enantiomers are also found in blood and urine (76), and in the case of serine, at high concentrations in the brain (77,78). Chiral derivatizations combined with resolution of the resulting diastereomers by LC and MS detection (78,79) or enzymatically (80) are well established but the application of chromatography-free NMR to this analysis has not been developed. In the future, a similar strategy to the DATAN-derivatized 2HG could be applied to distinguishing the amino acid enantiomers without the requirements of chromatography.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 5P20GM121327, and Edith D. Gardner (TWMF) and Carmen L. Buck (ANL) endowment funds.

Abbreviations:

- DATAN (+) O,O’

diacetyl-L-tartaric anhydride, GSH, GSSG reduced and oxidized glutathione, 2HG 2-hydroxyglutarate

- IDH2

isocitrate dehydrogenase 2

- NHS N

hydroxysuccinimide ester

- QDA N

(2-15Naminooxyethyl)-N,N-dimethyl-1-dodecylammonium, QDE Dodecyl-N-[2-(2-iodo-acetylamino)-ethyl]-N,N-dimethylammonium iodide

- SIRM

Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics

References

- 1.Bruntz RC, Lane AN, Higashi RM and Fan TW (2017) Exploring cancer metabolism using stable isotope-resolved metabolomics (SIRM). J Biol Chem, 292, 11601–11609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lane AN, Higashi RM and Fan TWM (2019) NMR and MS-based Stable Isotope-Resolved Metabolomics and applications in cancer metabolism. Trac-Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 120, 115322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan TW-M and Lane AN (2016) Applications of NMR to Systems Biochemistry. Prog. NMR Spectrosc, 92, 18–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruntz RC, Higashi RM, Lane AN and Fan TW-M (2017) Exploring Cancer Metabolism using Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM). J. Biol. Chem, 292, 11601–11609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong M, Jayaraman A, Marin S, Selivanov V, de Atauri Carulla PR, Tennant DA, Cascante M, Günther UL and Ludwig C (2017) Combined Analysis of NMR and MS Spectra (CANMS). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 56, 4140–4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buescher JM, Antoniewicz MR, Boros LG, Burgess SC, Brunengraber H, Clish CB, DeBerardinis RJ, Feron O, Frezza C, Ghesquiere B et al. (2015) A roadmap for interpreting (13)C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Current opinion in biotechnology, 34, 189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahar R, Donabedian PL and Merritt ME (2020) HDO production from [2H7]glucose Quantitatively Identifies Warburg Metabolism. Sci Rep 10, 8885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Graaf RA, Brown PB, Mason GF, Rothman DL and Behar KL (2003) Detection of 1,6-C-13(2) -glucose metabolism in rat brain by in vivo H-1 C-13 -NMR spectroscopy. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 49, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Feyter HM, Thomas MA, Behar KL and de Graaf RA (2021) NMR visibility of deuterium-labeled liver glycogen in vivo. Magn Reson Med, 86, 62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan TWM and Lane AN (2011) NMR-based stable isotope resolved metabolomics in systems biochemistry. Journal of biomolecular NMR, 49, 267–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore S and Stein WH (1963) Chromatographic determination of amino acids by the use of automatic recording equipment. Methods in Enzymology, 6, 819–831. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez HL and Evans CA (2015) Chemical derivatization in bioanalysis. Bioanalysis, 7, 2435–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenfeld JM (2003) Derivatization in the current practice of analytical chemistry. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 22, 785–798. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence JF (1979) Derivatization in Chromatography Introduction Practical Aspects of Chemical Derivatization in Chromatography Journal of Chromatographic Science, 113–114. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan TWM, Higashi RM, Lane AN and Jardetzky O (1986) Combined use of proton NMR and gas chromatography-mass spectra for metabolite monitoring and in vivo proton NMR assignments. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 882, 154–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moldoveanu SC and David V (2019) In Kusch P (ed.), Gas Chromatography. InTechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane AN and Fan TW-M (2017) NMR-based Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics in systems biochemistry. Arch. Biochem. Biophys, 628, 123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng X, Pang H, Sun F, Jin X, Wang B, Yao K, Yao L, Wang L and Hu Z (2021) A simultaneous 3-nitrophenylhydrazine derivatization strategy of carbonyl, carboxyl and phosphoryl submetabolome for LC-MS/MS-based targeted metabolomics with improved sensitivity and coverage. Anal. Chem., 29, 10075–10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, Fan TWM, Lane AN and Higashi RM (2017) Chloroformate Derivatization for Tracing the Fate of Amino Acids in Cells and Tissues by Multiple Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (mSIRM). Analytica chimica acta, 976, 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattingly SJ, Xu T, Nantz MH, Higashi RM and Fan TWM (2012) A carbonyl capture approach for profiling oxidized metabolites in cell extracts. Metabolomics, 8, 989–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane AN, Arumugam S, Lorkiewicz PK, Higashi RM, Laulhe S, Nantz MH, Moseley HNB and Fan TW-M (2015) Chemoselective detection of carbonyl compounds in metabolite mixtures by NMR. Mag. Res. Chem, 53, 337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tayyari F, Gowda G, Gu H and Raftery D (2013) 15N-cholamine--a smart isotope tag for combining NMR- and MS-based metabolite profiling. Anal Chem, 85, 8715–8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye T, Mo HP, Shanaiah N, Gowda GAN, Zhang SC and Raftery D (2009) Chemoselective 15N tag for sensitive and high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance profiling of the carboxyl-containing metabolome. Analytical Chemistry 81, 4882–4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vicente-Munoz S, Lin P, Fan TW-M and Lane AN (2021) Chemoselection with isotopomer analysis using 15N Cholamine. . Anal. Chem., 93, 6629–6637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalmers RA, Lawson AM, Watts RWE, Tavill AS, Kamerling JP, Hey E and Ogilvie D (1980) D-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria: Case report and biochemical studies. Journal of inherited metabolic disease, 3, 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K-R, Lee J, Ha D, Jeon J, Park H-G and Kim JH (2000) Enantiomeric separation and discrimination of 2-hydroxy acids as O-trifluoroacetylated (S)-(+)-3-methyl-2-butyl esters by achiral dual-capillary column gas chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A, 874, 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oldham WM and Loscalzo J (2016) Quantification of 2-hydroxyglutarate enantiomers by liquid chromatogrpahy-mass spectrometry. Bio-Protoc, 6, e1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gori SS, Lorkiewicz PK, Ehringer DS, Belshoff AC, Higashi RM, Fan TW-M and Nantz MH (2014) Profiling Thiol Metabolites and Quantification of Cellular Glutathione using FT-ICR-MS Spectrometry. Analytical & Bioanalytical Chemistry, 406, 4371–4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan E and Reid GA (2016) Chemical Derivatization and Ultrahigh Resolution and Accurate Mass Spectrometry Strategies for “Shotgun” Lipidome Analysis. Acc. Chem. Res., 49, 1596–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin P, Lane AN and Fan TW-M (2019) Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics by NMR. Methods in Molecular Biology, 2037, 151–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown GD, Bauer J, Osborn HMI and Kuemmerle R (2018) A Solution NMR Approach To Determine the Chemical Structures of Carbohydrates Using the Hydroxyl Groups as Starting Points. ACS Omega 3, 17957–17975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y-Z, Paterson Y and Roder H (1995) Rapid amide proton exchange rates in peptides and proteins measured by solvent quenching and two-dimensional NMR. Protein Science 4, 804–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lane AN and Fan TW (2007) Quantification and identification of isotopomer distributions of metabolites in crude cell extracts using 1H TOCSY. Metabolomics, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lane AN, Fan TW and Higashi RM (2008) Isotopomer-based metabolomic analysis by NMR and mass spectrometry. Biophysical Tools for Biologists., 84, 541–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fesik S (1988) Isotope-edited NMR spectroscopy. Nature 332, 865–866. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikura M and Bax A (1992) ISOTOPE-FILTERED 2D NMR OF A PROTEIN PEPTIDE COMPLEX - STUDY OF A SKELETAL-MUSCLE MYOSIN LIGHT CHAIN KINASE FRAGMENT BOUND TO CALMODULIN. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 114, 2433–2440. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sellers K, Fox MP, Bousamra M, Slone S, Higashi RM, Miller DM, Wang Y, Yan J, Yuneva MO, Deshpande R et al. (2015) Pyruvate carboxylase is critical for non-small-cell lung cancer proliferation. J. Clin. Invest, 125, 687–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lane AN (2012) In Fan TW-M, Lane AN and Higashi RM (eds.), Handbook of Metabolomics. Humana. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan TWM (1996) Metabolite profiling by one- and two-dimensional NMR analysis of complex mixtures. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, 28, 161–219. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu DH, Mulder H, Zhao PY, Burgess SC, Jensen MV, Kamzolova S, Newgard CB and Sherry AD (2002) C-13 NMR isotopomer analysis reveals a connection between pyruvate cycling and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 99, 2708–2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carvalho RA, Babcock EE, Jeffrey FMH, Sherry AD and Malloy CR (1999) Multiple bond C-13-C-13 spin-spin coupling provides complementary information in a C-13 NMR isotopomer analysis of glutamate. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 42, 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carvalho RA, Rodrigues TB, Zhao PY, Jeffrey FMH, Malloy CR and Sherry AD (2004) A C-13 isotopomer kinetic analysis of cardiac metabolism: influence of altered cytosolic redox and [Ca2+](o). American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 287, H889–H895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carvalho RA, Jeffrey FMH, Sherry AD and Malloy CR (1998) C-13 isotopomer analysis of glutamate by heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence total correlation spectroscopy (HMQC-TOCSY). Febs Letters, 440, 382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewis IA, Schommer SC, Hodis B, Robb KA, Tonelli M, Westler WM, Suissman MR and Markley JL (2007) Method for determining molar concentrations of metabolites in complex solutions from two-dimensional H-1-C-13 NMR spectra. Analytical Chemistry, 79, 9385–9390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gradwell MJ, Fan TWM and Lane AN (1998) Analysis of phosphorylated metabolites in crayfish extracts by two-dimensional H-1-P-31 NMR heteronuclear total correlation spectroscopy (heteroTOCSY). Analytical Biochemistry, 263, 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhinderwala F, Evans P, Jones K, Laws BR, Smith TG, Morton M and Powers R (2020) Phosphorus NMR and Its Application to Metabolomics. Anal. Chem, 92, 9536–9545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin P, Dai L, Crooks DR, Neckers LM, Higashi RM, Fan TWM and Lane AN (2021) NMR Methods for Determining Lipid Turnover via Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics. Metabolites, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahara T, Amemiya Y, Sugiyama R, Maki M and Shibata H (2020) Amino acid-dependent control of mTORC1 signaling: a variety of regulatory modes. . J Biomed Sci 27, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyder F, Patel AB, Gjedde A, Rothman DL, Behar KL and Shulman RG (2006) Neuronal-glial glucose oxidation and glutamatergic - GABAergic function. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 26, 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aliu E, Kanungo S and Arnold GL (2018) Amino acid disorders. Ann Transl Med., 6, 471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shanaiah N, Desilva MA, Nagana Gowda GA, Raftery MA, Hainline BE and Raftery D (2007) Class selection of amino acid metabolites in body fluids using chemical derivatization and their enhanced 13C NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104, 11540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ye T, Zhang S, Mo H, Tayyari F, Gowda GAN and Raftery D (2010) 13C-formylation for improved nuclear magnetic resonance profiling of amino metabolites in biofluids. Analytical chemistry, 82, 2303–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sakamoto T, Qiu Z, Inagaki M and Fujimoto K (2020) Simultaneous Amino Acid Analysis Based on 19F NMR Using a Modified OPA-Derivatization Method. Analytical Chemistry, 92, 1669–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen YT, Li B, Li XY, Chen JL, Cui CY, Hu K and Su XC (2021) Simultaneous identification and quantification of amino acids in biofluids by reactive (19)F-tags. Chem Commun (Camb), 57, 13154–13157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fu X, Li M, Biswas S, Nantz MH and Higashi RM (2011) A novel microreactor approach for analysis of ketones and aldehydes in breath Analyst, 136, 4662–4666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mattingly SJ, Xu T, Nantz MH, Higashi RM and Fan TW-M (2012) Carbonyl Capture Approach for Profiling Oxidized Metabolites in Cell Extracts. Metabolomics, 8, 989–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Logue BA, Maserek WK, Rockwood GA, Keebaugh MW and Baskin SI (2009) The analysis of 2-amino-2-thiazoline-4-carboxylic acid in the plasma of smokers and non-smokers. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 19, 202–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bian X, Qian Y, Tan B, Li K, Hong X, Wong CC, Fu L, Zhang J, Li N and Wu JL In-depth mapping carboxylic acid metabolome reveals the potential biomarkers in colorectal cancer through characteristic fragment ions and metabolic flux. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Ye T, Mo H, Shanaiah N, Gowda GAN, Zhang S and Raftery D (2009) Chemoselective 15N Tag for Sensitive and High-Resolution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Profiling of the Carboxyl-Containing Metabolome. Analytical Chemistry, 81, 4882–4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vicente-Munoz S, Lin P, Fan TWM and Lane AN (2021) NMR Analysis of Carboxylate Isotopomers of C-13-Metabolites by Chemoselective Derivatization with N-15-Cholamine. Analytical Chemistry, 93, 6629–6637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lu C, Ward PS, Kapoor GS, Rohle D, Turcan S, Abdel-Wahab O, Edwards CR, Khanin R, Figueroa ME, Melnick A et al. (2012) IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature, 483, 474–U130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tyrakis PA, Palazon A, Macias D, Lee KL, Phan AT, Velica P, You J, Chia GS, Sim J, Doedens A et al. (2016) S-2-hydroxyglutarate regulates CD8(+) T-lymphocyte fate. Nature, 540, 236–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teng X, Emmett MJ, Lazar MA, Goldberg E and Rabinowitz JD (2016) Lactate Dehydrogenase C Produces S-2-Hydroxyglutarate in Mouse Testis. Acs Chemical Biology, 11, 2420–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Intlekofer AM, Wang B, Liu H, Shah H, Carmona-Fontaine C, Rustenburg AS, Salah S, Gunner MR, Chodera JD, Cross JR et al. (2017) L-2-Hydroxyglutarate production arises from noncanonical enzyme function at acidic pH. Nature Chemical Biology, 13, 494–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Intlekofer AM, Dematteo RG, Venneti S, Finley LWS, Lu C, Judkins AR, Rustenburg AS, Grinaway PB, Chodera JD, Cross JR et al. (2015) Hypoxia Induces Production of L-2-Hydroxyglutarate. Cell Metabolism, 22, 304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oldham WM, Clish CB, Yang Y and Loscalzo J (2015) Hypoxia-Mediated Increases in L-2-hydroxyglutarate Coordinate the Metabolic Response to Reductive Stress. Cell Metabolism, 22, 291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fan J, Teng X, Liu L, Mattaini KR, Looper RE, Vander Heiden MG and Rabinowitz JD (2015) Human Phosphoglycerate Dehydrogenase Produces the Oncometabolite D-2-Hydroxyglutarate. Acs Chemical Biology, 10, 510–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kowlgi NG and Chhabra L (2015) D-Lactic Acidosis: An Underrecognized Complication of Short Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheng Q-Y, Xiong J, Huang W, Ma Q, Ci W, Feng Y-Q and Yuan B-F (2015) Sensitive Determination of Onco-metabolites of D- and L-2-hydroxyglutarate Enantiomers by Chiral Derivatization Combined with Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Analysis. Scientific Reports, 5, 15217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Struys EA, Jansen EE, Verhoeven NM and Jakobs C (2004) Measurement of urinary D- and L-2-hydroxyglutarate enantiomers by stable-isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry after derivatization with diacetyl-L-tartaric anhydride. Clin Chem, 50, 1391–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Merino MJ, Ricketts CJ, Moreno V, Yang Y, Fan TWM, Lane AN, Meltzer PS, Vocke CD, Crooks DR and Linehan WM (2021) Multifocal Renal Cell Carcinomas With Somatic IDH2 Mutation: Report of a Previously Undescribed Neoplasm. American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 45, 137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gori SS, Lorkiewicz P, Ehringer DS, Belshoff AC, Higashi RM, Fan TWM and Nantz MH (2014) Profiling thiol metabolites and quantification of cellular glutathione using FT-ICR-MS spectrometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 406, 4371–4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Townsend D, Tew K and Tapiero H (2003) Townsend DM, Tew KD, Tapiero H. The importance of glutathione in human disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2003;57:145–155. Biomed Pharmacother., 57, 145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nagana Gowda GA, Pascua V and Raftery D (2021) Extending the Scope of (1)H NMR-Based Blood Metabolomics for the Analysis of Labile Antioxidants: Reduced and Oxidized Glutathione. Anal Chem, 93, 14844–14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Desilva MA, Shanaiah N, Nagana Gowda GA, Rosa-Pérez K, Hanson BA and Raftery D (2009) Application of31P NMR spectroscopy and chemical derivatization for metabolite profiling of lipophilic compounds in human serum. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 47, S74–S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Suzuki M, Shimizu-Hirota R, Mita M, Hamase K and Sasabe J (2022) Chiral resolution of plasma amino acids reveals enantiomer-selective associations with organ functions. Amino Acids, 54, 421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolosker H, Dumin E, Balan L and Foltyn VN (2008) D-amino acids in the brain: D-serine in neurotransmission and neurodegeneration. FEBS Journal, 275, 3514–3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kimura R, Tsujimura H, Tsuchiya M, Soga S, Ota N, Tanaka A and Kim H (2020) Development of a cognitive function marker based on D-amino acid proportions using new chiral tandem LC-MS/MS systems. Sci Rep 10, 10, 804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ilisz I, Robert Berkecz R and Péter A (2008) Application of chiral derivatizing agents in the high-performance liquid chromatographic separation of amino acid enantiomers: a review. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 47, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maucler C, Pernot P, Vasylieva N, Pollegioni L and Marines S (2013) In Vivo d-Serine Hetero-Exchange through Alanine-Serine-Cysteine (ASC) Transporters Detected by Microelectrode Biosensors. ACS Chem Neurosci., 4, 772–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lane AN and Fan TW-M (2007) Quantification and identification of isotopomer distributions of metabolites in crude cell extracts using 1H TOCSY. Metabolomics, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moseley HN, Lane AN, Belshoff AC, Higashi RM and Fan TW (2011) A novel deconvolution method for modeling UDP-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine biosynthetic pathways based on (13)C mass isotopologue profiles under non-steady-state conditions. BMC Biol, 9, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lane AN, Arumugam S, Lorkiewicz PK, Higashi RM, Laulhé S, Nantz MH, Moseley HNB and Fan TWM (2015) Chemoselective detection and discrimination of carbonyl-containing compounds in metabolite mixtures by 1H-detected 15N nuclear magnetic resonance. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 53, 337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vicente-Muñoz S, Lin P, Fan TWM and Lane AN (2021) NMR Analysis of Carboxylate Isotopomers of 13C-Metabolites by Chemoselective Derivatization with 15N-Cholamine. Analytical Chemistry, 93, 6629–6637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tayyari F, Gowda GAN, Gu H and Raftery D (2013) 15N-cholamine--a smart isotope tag for combining NMR- and MS-based metabolite profiling. Analytical chemistry, 85, 8715–8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]