Key Points

Question

How does the distribution of race and ethnicity in randomized clinical trials of diabetic macular edema (DME) and macular edema from retinal vein occlusions (RVO) compare to the 2010 US Census data?

Findings

This cross-sectional study of 9924 participants found that the demographic distribution of race and ethnicity in most trials did not reflect that of the US population according to the 2010 US Census. Participants identifying as White tended to be overrepresented.

Meaning

These findings suggest that more work is needed to recruit and better represent racial and ethnic minority groups in DME and RVO randomized clinical trials.

This cross-sectional study evaluates the representation of racial and ethnic minority groups in randomized clinical trials of diabetic macular edema and retinal vein occlusion compared with US Census data.

Abstract

Importance

Diverse enrollment and adequate representation of racial and ethnic minority groups in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are valuable to ensure external validity and applicability of results.

Objective

To compare the distribution of race and ethnicity in RCTs of diabetic macular edema (DME) and macular edema from retinal vein occlusion (RVO) to that of US Census data.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a cross-sectional retrospective analysis comparing racial and ethnic demographic characteristics of US-based RCTs of DME and RVO between 2004 and 2020 with 2010 US Census data. PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched to screen for completed phase 3 RCTs with published results. Of 169 trials screened, 146 were excluded because they were incomplete, did not report race and ethnicity, or were not based in the US, and 23 trials were included (15 DME and 8 RVO). The number and percentage of American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and White participants was recorded in each RCT. The demographic distribution and proportion was compared to the reported distribution and proportion in the 2010 US Census using the χ2 test.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Overrepresentation, underrepresentation, or representation commensurate with 2010 US Census data in the racial and ethnic populations of RCTs of retinal vascular disease.

Results

In 23 included RCTs of DME and RVO, there were a total of 38 participants (0.4%) who identified as American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (groups combined owing to small numbers), 415 Asian participants (4.4%), 904 Black participants (9.6%), 954 Hispanic participants (10.1%), and 7613 White participants (80.4%). By comparison, the 2010 US Census data indicated that 1.1% of the US population self-reported as American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (groups combined for comparison in this study), 4.8% self-reported as Asian, 12.6% as Black or African American, 16.3% as Hispanic, and 63.7% as White. American Indian or Alaska Native and Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander participants were underrepresented in 2 trials, neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 20, and not overrepresented in any of the included trials. Asian participants were underrepresented in 10 trials, overrepresented in 4, and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 8. Black participants were underrepresented in 9 trials, overrepresented in 2, and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 11. Hispanic participants were underrepresented in 15 trials, overrepresented in 2, and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 5. White participants were underrepresented in 2 trials, overrepresented in 14, and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 7. The χ2 values comparing RCT demographic distribution to US 2010 Census data were significantly different in 22 of 23 included RCTs.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings in this study indicated a discrepancy between racial and ethnic demographic data in RCTs of DME and RVO and the US population according to the 2010 Census. White study participants were most frequently overrepresented, and Hispanic study participants were most frequently underrepresented. These findings support the need for more efforts to recruit underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities to improve external validity in trial findings.

Introduction

Based on 2020 US Census data, the US population has continued to increase in racial and ethnic diversity.1 As health care professionals, and as ophthalmologists, we are charged with providing optimal care for this increasingly diverse population.2 Diverse populations have diverse needs, and numerous epidemiological studies have demonstrated racial and ethnic differences in eye disease prevalence and course of progression.3,4 Unfortunately, despite the availability of newer treatments and modalities, disparities in outcomes persist.

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs), which can minimize bias and provide strong clinical evidence that can change clinical practice, often represent a high standard of evidence-based medicine. To provide evidence-based care, it is important that RCTs strive to represent real-world populations. Poor representation may affect the external validity of studies and limit applications to underrepresented sociodemographic minorities.5 In fact, the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) and the American College of Physicians remarked that underrepresentation in clinical trials serves to deepen preexisting disparities, and the National Institutes of Health has enacted policies in an effort to stymie this effect.6,7,8 However, the persistence of underrepresentation of minority groups continues to be well described across the medical literature, and ophthalmology has been no exception.9,10,11,12,13 A study examining the representation of race and ethnicity in studies for new ocular molecular entities between 2006 and 2016 found no change in the composition of participants in RCTs and concluded that most participants were female individuals who identified as White.14

In ophthalmology, the greatest number of RCTs have been conducted on diseases of the retina, which include diabetic and hypertensive eye disease as among the most prevalent disorders.15 These disorders are no exception to disparities in care. Diabetes remains more prevalent in African American and Hispanic populations than in White populations, and these groups experience visual impairment from diabetes-related complications at 1.4-fold and 1.5-fold the rate among White individuals in the US, respectively.16,17,18,19 Incidence of retinal vein occlusions (RVOs) and hypertension are at least as or more prevalent in Hispanic and Black populations than White populations, respectively.20,21,22 However, the extent of population-based representation of racial and ethnic groups in RCTs is unknown. This study sought to explore the distribution of race and ethnicity in RCTs of diabetic macular edema (DME) and macular edema from RVO compared to 2010 US Census data.

Methods

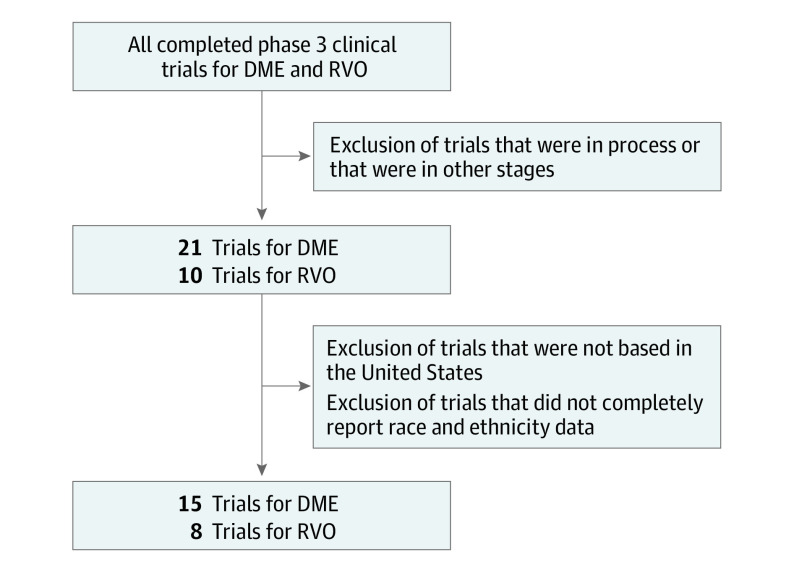

Institutional review board approval was not required for this study because no protected patient information was accessed. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. We performed a retrospective cross-sectional study of the racial and ethnic demographic data of all completed phase 3 RCTs for DME and RVO as of May 2021 and compared them to 2010 US Census data. We initially identified 21 trials for DME and 10 for RVO. Trials that had no study centers in the US were removed from analysis, as well as trials that did not completely report race and ethnicity data. This process was undertaken to prevent bias in the selection of included studies and is summarized in Figure 1. eTable 1 in the Supplement provides a list of trials screened and the specific reason for exclusion for each trial. Indication, years of study activity, number of enrolled and randomized study participants, and race and ethnicity breakdown of all trials were recorded. When these data were not reported in the main methods section of the paper, appendices and supplemental information sections were used. Additionally, the number and percentage of American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and White participants were recorded. If the data were not available, the value was indicated as unreported. For statistical evaluation, unreported values were treated as null, with the assumption that if not explicitly mentioned, the study did not recruit any study participants of that racial or ethnic category. Study participants who were identified as other, unknown, or more than 1 race were recorded for the purpose of data analysis but the data were treated as null values in both the numerator and denominator to avoid skewing the analysis. This was most salient in 1 RVO trial, as only the number of White study participants and number of total study participants in the study were reported.23

Figure 1. Flow Diagram for Inclusion of Identified Studies.

DME indicates diabetic macular edema; RVO, retinal vein occlusions.

Publicly available 2010 US Census data were used. We chose to compare demographic characteristics to US 2010 Census data as 2010 reflected the closest proximity in time, on average, to the RCTs examined. In addition, the 2020 data were still in collection and unavailable at the time of data analysis. The demographic distribution of each RCT was compared to the reported distribution of the 2010 US Census demographic data using the χ2 test. We were unable to perform a χ2 test for the 1 RCT that only provided racial demographic data for White study participants.23 The proportion of each race or ethnicity was compared to its reported proportion from the 2010 Census data using 1-sample z test. These values were calculated in Excel version 2207 (Microsoft). A more stringent significance threshold of P < .01 was used given the multiple analyses performed. P values were 2-sided but were not adjusted for multiple analyses.

Results

After selecting for completed US-based RCTs that included race and ethnicity information, 15 DME and 8 RVO trials were available for analysis (Table). These trials ranged from opening as early as 2004 to ending as recent as 2020. There were a total of 38 participants (0.4%) who identified as American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (groups combined owing to small numbers), 415 Asian participants (4.4%), 904 Black participants (9.6%%), 954 Hispanic participants (10.1%), and 7613 White participants (80.4%) in the included RCTs. By comparison, the 2010 US Census data indicated that 1.1% of the US population self-reported as American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (groups combined for comparison in this study), 4.8% self-reported as Asian, 12.6% as Black or African American, 16.3% as Hispanic, and 63.7% as White.

Table. Randomized Clinical Trials of Diabetic Macular Edema and Retinal Vein Occlusion Reviewed for Analysis.

| Trial | Trial short code | Study completion year | Participant enrollment, No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic macular edema | |||

| Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network,24 2008 | DRCR Retina Network Protocol B | 2008 | 840 |

| Massin et al,25 2010 | RESOLVE | 2008 | 151 |

| Do et al, 26 2012 | Da Vinci | 2010 | 219 |

| Googe et al,27 2011 | DRCR Retina Network Protocol J | 2010 | 345 |

| Sultan et al,28 2011 | Macugen (NCT00605280) | 2011 | 260 |

| Nguyen et al,29 2012 | RISE | 2012 | 377 |

| Nguyen et al,29 2012 | RIDE | 2012 | 382 |

| Do et al,30 2015 | READ-3 | 2013 | 152 |

| Prünte et al,31 2016 | RETAIN | 2013 | 372 |

| Elman et al,32 2010 | DRCR Retina Network Protocol I | 2013 | 854 |

| Korobelnik et al,33 2014 | VIVID | 2015 | 403 |

| Korobelnik et al,33 2014 | VISTA | 2015 | 459 |

| Wells et al,34 2015 | DRCR Retina Network Protocol T | 2018 | 660 |

| Baker et al,35 2019 | DRCR Retina Network Protocol V | 2018 | 702 |

| Antoszyk et al,36 2020 | DRCR Retina Network Protocol AB | 2020 | 205 |

| Retinal vein occlusion | |||

| Haller et al,37 2010 | GENEVA | 2008 | 1267 |

| Ip et al,23 2009 | SCORE 1 | 2009 | 682 |

| Campochiaro et al,38 2010 | BRAVO | 2009 | 397 |

| Brown et al,39 2010 | CRUISE | 2009 | 392 |

| Campochiaro et al,40 2014 | SHORE | 2012 | 202 |

| Boyer et al,41 2012 | COPERNICUS | 2012 | 188 |

| Holz et al,42 2013 | GALILEO | 2012 | 172 |

| Scott et al,43 2017 | SCORE 2 | 2016 | 362 |

DME

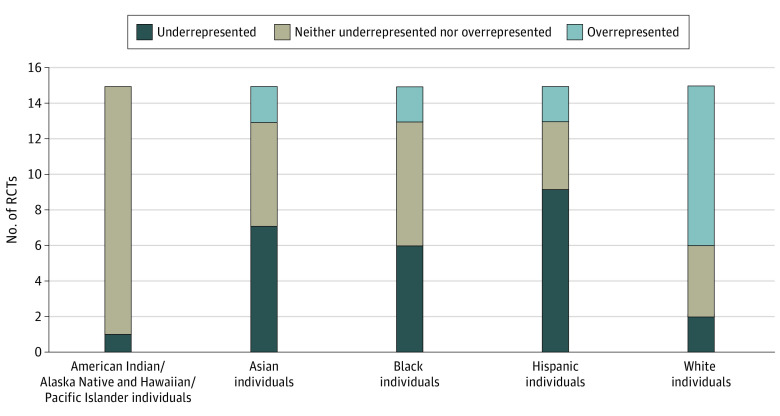

Compared to the 2010 US Census data, in the 15 RCTs for DME treatment, the American Indian or Alaska Native and Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander study participant cohort (groups combined owing to small numbers) was underrepresented in 1 RCT32 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 14. The Asian study participant cohort was underrepresented in 7 trials,24,27,31,32,33,34,35 overrepresented in 2,28,33 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 6.25,26,29,30,36 The Black study participant cohort was underrepresented in 6 RCTs,24,25,26,28,31,33 overrepresented in 2,32,35 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 7.24,29,30,33,34,36 The Hispanic study participant cohort was underrepresented in 9 trials,23,25,26,28,31,32,33 overrepresented in 2,27,29 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 4.29,30,34,35 The White study participant cohort was underrepresented in 2 RCTs,30,36 overrepresented in 9,24,25,26,28,29,31,32,33 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 4.27,29,34,35 These data are summarized in Figure 2. eTable 2 in the Supplement summarizes the proportions of each demographic cohort recruited in each study compared to the expected proportions as per the 2010 US Census, with P values for the 1-sample z test and 99% CIs listed for each clinical trial used in this study for analysis. The χ2 values comparing RCT demographic distribution to US 2010 Census data were significantly different in 15 of 15 RCTs.

Figure 2. Underrepresentation and Overrepresentation of Race and Ethnicity in Diabetic Macular Edema Trials Compared to US 2010 Census Data.

Macular Edema From RVO

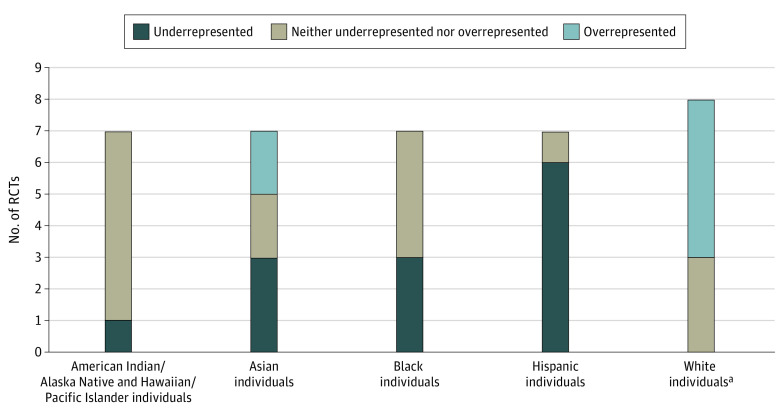

In the 8 RCTs for RVO treatment, 1 trial23 only included data for White participants. The White study participant cohort was overrepresented in 5 of these 8 RCTs,23,37,38,39,40 neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 3,41,42,43 and not underrepresented in any of the RVO trials. Of the remaining 7 RVO trials, the American Indian or Alaska Native and Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander study participant cohort was underrepresented in 1 RCT37 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 6.38,39,40,41,42,43 The Asian study participant cohort was underrepresented in 3 trials,38,39,43 overrepresented in 2,37,42 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 2.40,41 The Black study participant cohort was underrepresented in 3 RCTs37,41,42 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 4 trials.38,39,40,43 The Hispanic study participant cohort was underrepresented in 6 RCTs37,38,39,40,42,43 and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 1.41 These data are summarized in Figure 3. The χ2 values comparing RCT demographic distribution to US 2010 Census data were significantly different in 6 of 6 RCTs for which χ2 tests could be performed. We could not perform a χ2 test for the SCORE 1 trial,23 which only included racial data for White study participants. eTable 3 in the Supplement summarizes the proportions of each demographic cohort recruited in each study compared to the expected proportions as per the 2010 US Census, with the 99% CIs listed for each clinical trial used in this study.

Figure 3. Underrepresentation and Overrepresentation of Race and Ethnicity in Retinal Vein Occlusion Trials Compared to US 2010 Census Data.

aWhite demographic included 1 additional randomized clinical trial, as 1 trial only provided racial and ethnic data for White participants.

Results Summary

In the 23 RCTs for DME and RVO, American Indian or Alaska Native and Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander study participants were underrepresented in 2 RCTs, neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 20, and not overrepresented in any of the included trials. Asian participants were underrepresented in 10 trials, overrepresented in 4, and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 8. Black participants were underrepresented in 9 trials, overrepresented in 2, and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 11. Hispanic participants were underrepresented in 15 trials, overrepresented in 2, and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 5. White participants were underrepresented in 2 trials, overrepresented in 14, and neither overrepresented nor underrepresented in 7.

Discussion

Although the chance that in the US, 2 individuals chosen at random are 6.2% more likely to be from different racial or ethnic backgrounds in 2020 than in 2010, clinical trials continue to underrepresent minorities and possibly contribute to continued health care disparities. Many racial and ethnic groups continue to be underrepresented in studies of retinal disease as well, even though epidemiologic and demographic studies over the past 30 years have demonstrated that racial and ethnic minority groups and individuals of specific racial status are at greater risk of developing entities such as DME.7,8 Our study demonstrates the need for increased diversity and racial representation in recruiting for trials and in evaluating DME and RVO treatment trials based on the finding that the number of underrepresented minority individuals in retinal vascular RCTs was out of proportion to the racial and ethnic composition of the US population.

Limitations

There have been a few recent studies examining the underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic populations in DME and diabetic retinopathy trials. This study joins the call for improved representation but differs in a few key ways.44,45 RCT populations in this article were compared to corresponding demographic characteristics as reported in the US Census instead of to treatment databases. Further, this study explores the representation of race and ethnicity in treatment for both DME and RVO, an approach that provides a summary of the level of representation of each group across the body of the retinal vascular disease literature. In our initial analysis of 32 trials, we observed that race and ethnicity reporting is inconsistently and heterogeneously gathered and reported, if it is reported at all. This naturally led to a limitation to our study. However, this observation supports a recent publication that found that of articles published in the ophthalmic literature in 2019, 43% reported study participant race and ethnicity.46 When these data were included, 78 distinct categories of race and ethnicity were identified. Clinical trialists are not without guidance on this matter: the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Office of Minority Health produced a document47 in 2016 that explicitly outlines recommendations on how to collect and report race and ethnicity data in a standardized format. At a minimum, the FDA recommends that study participants be offered the choice of self-reporting race as American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and/or White and offered the choice of Hispanic or Latino or not Hispanic or Latino as options for reporting ethnicity. These categories mirror the options offered in the US Census.

Another limitation includes the reference point of our data. We chose to use the 2010 US Census data to analyze studies performed between 2004 and 2020, which could change the determination of underrepresentation or overrepresentation of racial and ethnic groups. However, the US Census is performed and available on a decennial basis, meaning this limitation is unavoidable. Further, as per 2020 Census data, the US population grew more diverse between 2010 and 2020, meaning it is possible that underrepresentation of racial or ethnic groups in our study would be underestimated. To this extent, clinical trial recruiters will need to remain diligent in representing the diversity of the US population.

While our study evaluates RCT demographic data compared to US Census data, we did not statistically adjust for populations in which retinal vascular diseases are more common. Several studies4,48,49 have found that Black individuals and Latino individuals were more likely to experience diabetic retinopathy and associated complications compared with White individuals. Thus, our study likely underestimates the degree of underrepresentation among these groups in the epidemiological framework of retinal vascular diseases in the US. Clinical trial design must often strike a balance between appropriately representing population demographic characteristics and intentionally representing populations experiencing a greater burden of disease. To this extent, clinical trial investigators might consider performing power and sample size calculations for enabling subgroup analysis, particularly for minority groups that are known to have disproportionate burdens of a given condition. This would likely necessitate advance planning in trial design as well as logistical considerations such as enrollment time, funding required, and total study participant recruitment.

Additional studies to identify recruitment barriers for underrepresented racial and ethnic minority groups will need to be performed, but the literature has already identified some barriers that should be considered in future studies by, for example, increasing racial and ethnic representation among investigators and working to rebuild trust with communities that may be fearful of health care researchers due in part to past institutional health care injustices and systemic racism. Sanjiv et al45 indicate that involving anthropologists may be helpful in rebuilding critical trust with these communities, aiding researchers in the direct engagement with the perceived needs of marginalized communities to further garner respect and reduce existing disparities. These challenges are not impossible to surmount, but they will need to be purposefully addressed with an integrated approach among health care professionals and the institutions within which they operate.

The evidence of underrepresentation of minority groups in trials begs another important question: is there a meaningful difference in response to treatment among racial and ethnic groups? One retrospective study found that, after receiving intravitreal bevacizumab for the treatment of DME, Black participants experienced a significantly lower likelihood of improvement in visual acuity.50 No other studies could be found that either validated this finding or evaluated the response of other minority groups to DME or RVO treatment. Future studies should focus on verifying the applicability of large RCT results to cohorts of sociodemographic minority group.

Conclusions

This study found that racial and ethnic demographic data of study participants in most RCTs for treatment of DME and RVO did not reflect that of the US population according to the 2010 US Census. Study participants identifying as White tended to be overrepresented in most RCTs. These findings support the need for more efforts to recruit underrepresented minority groups, which could improve the generalizability of RCT results and in turn help address health care disparities and better serve diverse populations.

eTable 1. Summary listing of the inclusion and exclusion reasons of DME and RVO trials, arranged chronologically by study completion year

eTable 2. Proportion of each racial demographic included in the diabetic macular edema clinical trials, compared to the expected 2010 United State Census

eTable 3. Proportion of each racial demographic included in the retinal vein occlusion clinical trials, compared to the expected 2010 United State Census

References

- 1.Bureau UC. The chance that two people chosen at random are of different race or ethnicity groups has increased since 2010. US Census Bureau . Accessed January 1, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/2020-united-states-population-more-racially-ethnically-diverse-than-2010.html

- 2.Wright PR. Care of culturally diverse patients undergoing ophthalmic surgery. Insight. 2011;36(1):7-10;quiz 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Francis BA, et al. ; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group . Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(8):1439-1448. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varma R, Choudhury F, Klein R, Chung J, Torres M, Azen SP. Four-year incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy and macular edema: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(5):752-761.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee EWJ, Viswanath K. Big data in context: addressing the twin perils of data absenteeism and chauvinism in the context of health disparities research. J Med internet Res. 2020;22(1):e16377. doi: 10.2196/16377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amendment: NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research—October, 2001. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-02-001.html

- 7.Institute of Medicine; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care ; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. The National Academies Press; 2003. doi: 10.17226/12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Physicians . Racial and ethnic disparities in health care, update 2010. Published online 2010. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.acponline.org/acp_policy/policies/racial_ethnic_disparities_2010.pdf

- 9.Loree JM, Anand S, Dasari A, et al. Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10):e191870. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration . Drug trials snapshots: summary report. Published online 2020. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/145718/download

- 11.2015-2016 Global participation in clinical trials report. Published online July 2017. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/106725/download

- 12.2015-2019 Drug Trials Snapshots Summary Report. Published online November 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/143592/download

- 13.Berkowitz ST, Groth SL, Gangaputra S, Patel S. Racial/ethnic disparities in ophthalmology clinical trials resulting in US Food and Drug Administration Drug approvals from 2000 to 2020. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(6):629-637. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.0857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birnbaum FA. Gender and ethnicity of enrolled participants in U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clinical trials for approved ophthalmological new molecular entities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(5):473-479. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AlRyalat SA, Abukahel A, Elubous KA. Randomized controlled trials in ophthalmology: a bibliometric study. F1000Res. 2019;8:1718. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20673.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varma R, Bressler NM, Doan QV, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic macular edema in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(11):1334-1340. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Resources Office of Minority Health . Profile: Black/African Americans. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=61

- 18.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . Disparities overview by race and ethnicity. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data/disparities/summary/Chart/5380/3

- 19.Kempen JH, O’Colmain BJ, Leske MC, et al. ; Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group . The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):552-563. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostchega Y, Fryar CD, Nwankwo T, Nguyen DT; US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Hypertension prevalence among adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2017-2018 (2020). NCHS data brief no. 364. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db364-h.pdf [PubMed]

- 21.Rogers S, McIntosh RL, Cheung N, et al. ; International Eye Disease Consortium . The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion: pooled data from population studies from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(2):313-9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung N, Klein R, Wang JJ, et al. Traditional and novel cardiovascular risk factors for retinal vein occlusion: the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(10):4297-4302. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ip MS, Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, et al. ; the SCORE Study Research Group . A randomized trial comparing the efficacy and safety of intravitreal triamcinolone with observation to treat vision loss associated with macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: the Standard Care vs Corticosteroid for Retinal Vein Occlusion (SCORE) study report 5. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(9):1101-1114. dnoi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . A randomized trial comparing intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide and focal/grid photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(9):1447-1449, 1449.e1-1449.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massin P, Bandello F, Garweg JG, et al. Safety and efficacy of ranibizumab in diabetic macular edema (RESOLVE Study): a 12-month, randomized, controlled, double-masked, multicenter phase II study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2399-2405. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Do DV, Nguyen QD, Boyer D, et al. ; da Vinci Study Group . One-year outcomes of the da Vinci study of VEGF trap-eye in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(8):1658-1665. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Googe J, Brucker AJ, Bressler NM, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Randomized trial evaluating short-term effects of intravitreal ranibizumab or triamcinolone acetonide on macular edema after focal/grid laser for diabetic macular edema in eyes also receiving panretinal photocoagulation. Retina. 2011;31(6):1009-1027. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318217d739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sultan MB, Zhou D, Loftus J, Dombi T, Ice KS; Macugen 1013 Study Group . A phase 2/3, multicenter, randomized, double-masked, 2-year trial of pegaptanib sodium for the treatment of diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(6):1107-1118. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, et al. ; RISE and RIDE Research Group . Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):789-801. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Do DV, Sepah YJ, Boyer D, et al. ; READ-3 Study Group . Month-6 primary outcomes of the READ-3 study (Ranibizumab for Edema of the Macula in Diabetes-Protocol 3 With High Dose). Eye (Lond). 2015;29(12):1538-1544. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prünte C, Fajnkuchen F, Mahmood S, et al. ; RETAIN Study Group . Ranibizumab 0.5 mg treat-and-extend regimen for diabetic macular oedema: the RETAIN study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(6):787-795. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1064-1077.e35. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korobelnik JF, Do DV, Schmidt-Erfurth U, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2247-2254. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker CW, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT, et al. ; DRCR Retina Network . Effect of initial management with aflibercept vs laser photocoagulation vs observation on vision loss among patients with diabetic macular edema involving the center of the macula and good visual acuity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1880-1894. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antoszyk AN, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT, et al. ; DRCR Retina Network . Effect of intravitreous aflibercept vs vitrectomy with panretinal photocoagulation on visual acuity in patients with vitreous hemorrhage from proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(23):2383-2395. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfort R Jr, et al. ; OZURDEX GENEVA Study Group . Randomized, sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema due to retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1134-1146.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campochiaro PA, Heier JS, Feiner L, et al. ; BRAVO Investigators . Ranibizumab for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1102-1112.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown DM, Campochiaro PA, Singh RP, et al. ; CRUISE Investigators . Ranibizumab for macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1124-1133.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campochiaro PA, Wykoff CC, Singer M, et al. Monthly versus as-needed ranibizumab injections in patients with retinal vein occlusion: the SHORE study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(12):2432-2442. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyer D, Heier J, Brown DM, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor trap-eye for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: six-month results of the phase 3 COPERNICUS study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(5):1024-1032. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holz FG, Roider J, Ogura Y, et al. VEGF trap-eye for macular oedema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: 6-month results of the phase III GALILEO study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(3):278-284. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-301504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, Ip MS, et al. ; SCORE2 Investigator Group . Effect of bevacizumab vs aflibercept on visual acuity among patients with macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion: the SCORE2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2072-2087. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowe T, Salabati M, Soares RR, et al. Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in diabetic macular edema clinical trials. Ophthalmol Retina. 2022;6(6):531-533. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2022.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanjiv N, Osathanugrah P, Harrell M, et al. Race and ethnic representation among clinical trials for diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema within the United States: a review. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;114(2):123-140. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore DB. Reporting of race and ethnicity in the ophthalmology literature in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(8):903-906. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.US Food and Drug Administration . Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. Published online October 2016. Accessed September 7, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- 48.Wong TY, Klein R, Islam FMA, et al. Diabetic retinopathy in a multi-ethnic cohort in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(3):446-455. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gange WS, Lopez J, Xu BY, Lung K, Seabury SA, Toy BC. Incidence of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and other neovascular sequelae at 5 years following diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(11):2518-2526. doi: 10.2337/dc21-0228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osathanugrah P, Sanjiv N, Siegel NH, Ness S, Chen X, Subramanian ML. The impact of race on short-term treatment response to bevacizumab in diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;222:310-317. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Summary listing of the inclusion and exclusion reasons of DME and RVO trials, arranged chronologically by study completion year

eTable 2. Proportion of each racial demographic included in the diabetic macular edema clinical trials, compared to the expected 2010 United State Census

eTable 3. Proportion of each racial demographic included in the retinal vein occlusion clinical trials, compared to the expected 2010 United State Census