Abstract

Background

Once‐daily abrocitinib treatment provided meaningful improvements in signs and symptoms of moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in randomized controlled studies.

Objective

To evaluate proportions of patients with responses meeting higher threshold efficacy responses than commonly used efficacy end points and to determine if these responses were associated with quality‐of‐life (QoL) benefits.

Methods

Data from a phase 2b (NCT02780167) and two phase 3 studies (NCT03349060/JADE MONO‐1; NCT03575871/JADE MONO‐2) in adult and adolescent patients (N = 942) with moderate‐to‐severe AD receiving once‐daily abrocitinib 200 mg, abrocitinib 100 mg or placebo were pooled. Commonly used (Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI]‐75 and ≥4‐point improvement in Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale [PP‐NRS4]) and higher threshold efficacy end points (EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100, EASI‐100 or PP‐NRS0/1 response) were evaluated. Proportions of patients across Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index/Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI/DLQI) band descriptors who achieved various efficacy end points were analysed.

Results

More abrocitinib‐treated patients achieved commonly used or higher threshold efficacy end points at week 12 vs. placebo. More abrocitinib‐treated patients who achieved higher threshold efficacy end points reported ‘no effect’ of AD on QoL (by CDLQI/DLQI) at week 12 vs. those who achieved commonly used but not higher threshold efficacy end points (PP‐NRS0/1 vs. PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS0/1 responders [200 mg: 66.3% vs. 17.5%; 100 mg: 62.1% vs. 20.0%]; EASI‐100, EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 vs. EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 responders [200 mg: 67.6%, 48.9% vs. 28.8%; 100 mg: 63.2%, 48.1% vs. 36.7%]).

Conclusions

Substantial proportions of patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD receiving abrocitinib met higher threshold efficacy end points, and this was associated with meaningful additional QoL benefits compared with those who did not meet these higher efficacy thresholds. Not only do a substantial proportion of abrocitinib‐treated patients achieve higher threshold efficacy end points but they also do so in a similar timeframe as the more commonly used thresholds for efficacy end points.

Clinical trials

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory skin condition characterized by pruritus, eczematous lesions and dry skin that affects up to 25% of children and 5% to 10% of adults worldwide. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 The signs and symptoms of AD, especially pruritus, are severely burdensome and can lead to the development of depressive symptoms, 8 , 9 , 10 psychological distress and sleep disturbance, 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 which impact patient quality of life (QoL). 10 , 14 , 15 , 16 Abrocitinib, an oral, once‐daily, Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) inhibitor, was recently approved for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe AD in adults and adolescents in Great Britain 17 and Japan 18 and in adults in the European Union 19 and the United States. 20 Inhibition of JAK1 modulates various cytokines relevant to the pathophysiology of AD, including interleukin (IL)‐4, IL‐13, IL‐31 and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP). 21 , 22 , 23 Additionally, inhibition of the JAK1 pathway ameliorates the sensation of pruritus through direct neuronal JAK1 inhibition. 24 Hence, selective inhibition of JAK1 modulates multiple downstream signalling pathways critical to the pathogenesis and symptoms of AD.

Abrocitinib monotherapy was effective and well tolerated in clinical studies in patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD. 25 , 26 , 27 In JADE MONO‐1 and JADE MONO‐2, identical phase 3 studies in adult and adolescent patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD, significantly greater proportions of patients treated with abrocitinib (200 mg or 100 mg) achieved commonly used efficacy threshold responses defined as Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) 0/1 response (clear [0] or almost clear [1] with ≥2‐grade improvement), ≥75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index score (EASI‐75) response and/or ≥4‐point improvement from baseline in Peak Pruritus Numerical rating scale (PP‐NRS4) response compared with patients treated with placebo, and with a manageable safety profile. 26 , 27 Among the responders fulfilling these commonly used efficacy thresholds, a subset met higher threshold efficacy responses; for example, among those reaching EASI‐75 response, some had attained EASI‐90 or EASI‐100, and among those reaching PP‐NRS4 response, some achieved PP‐NRS0/1 (the latter reflecting profound itch control). Attaining these higher threshold efficacy responses may be associated with additional, clinically meaningful improvement in QoL. The objectives of these post hoc analyses were to determine the proportion of patients in the phase 2b and phase 3 abrocitinib monotherapy trials, who achieved higher threshold efficacy end points (90% improvement in EASI to <100% improvement in EASI [EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 response], EASI‐100 and PP‐NRS0/1), if the time to onset of these higher efficacy threshold responses differed from that observed for commonly used efficacy end points (EASI‐75 and PP‐NRS4), and to determine if these higher threshold efficacy responses were associated with additional and clinically meaningful improvement in QoL vs. commonly used efficacy responses.

Methods

Study design

These analyses used data pooled from three similarly designed abrocitinib monotherapy trials, including a phase 2b trial (NCT02780167) and two phase 3 trials (NCT03349060, JADE MONO‐1; NCT03575871, JADE MONO‐2) in adult and adolescent patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD treated with once‐daily abrocitinib 200 mg, abrocitinib 100 mg or placebo. 25 , 26 , 27 Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1:1 ratio in the phase 2b study to receive abrocitinib (200 mg, 100 mg, 30 mg or 10 mg) or placebo and in a 2:2:1 ratio in the phase 3 studies to receive abrocitinib (200 mg or 100 mg) or placebo. Details of all three studies along with primary efficacy and safety results were previously reported. 25 , 26 , 27 All study documents and procedures were approved by the appropriate institutional review board/ethics committee at each study site. The studies were conducted in compliance with the ethical principles originating in or derived from the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with all International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. All local regulatory requirements were followed. An internal review committee monitored the safety of patients throughout the studies. All patients provided written informed consent.

Patients

Study participants were patients aged 18–75 years (phase 2b) or ≥ 12 years (phase 3) with a clinical diagnosis of moderate‐to‐severe AD (IGA ≥3, EASI ≥12 [phase 2b] or ≥ 16 [phase 3], percentage of body surface area involvement [%BSA] ≥10, PP‐NRS; [used with permission of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Sanofi 28 ] ≥4 [phase 3 only]), for ≥1 year (phase 2b) and recent (phase 3: within 6 months) history of inadequate response to topical medications (corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors) given for ≥4 weeks or an inability to receive topical treatment because it was medically inadvisable. Previous dupilumab use was permitted in the phase 3 studies if it had been >6 weeks before study initiation. 26 , 27 Patients who previously used JAK inhibitors within 12 weeks (phase 2b) or ever (phase 3) or oral immunosuppressant agents (i.e. cyclosporine, azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil and systemic corticosteroids) within 4 weeks or five half‐lives (whichever was longer) were excluded from the studies. 25 , 26 , 27 Rescue medication (including topical corticosteroids) was prohibited during the studies. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are published elsewhere. 25 , 26 , 27

Post hoc analysis end points

End points assessed in this post hoc analysis included: proportion of patients who achieved commonly used efficacy end points and the proportion of patients who achieved higher threshold efficacy end points (EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 response, EASI‐100 response or PP‐NRS score of 0 or 1 [i.e. baseline score ≥2 achieving score <2; PP‐NRS0/1 response]) from baseline to week 12. Median time to response in patients with EASI‐100 response, EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 response (defined as % improvement in EASI ≥90% to <100%), EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 response (defined as % improvement in EASI ≥75% to <90%), PP‐NRS0/1 response and PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS0/1 response was also analysed. In addition, separate analyses evaluating the association of these end points with QoL improvement at week 12 were conducted. QoL improvement was stratified by (Children's) Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI/DLQI) severity bands, which describe the magnitude of the negative impact on QoL. CDLQI/DLQI scores of 0–1 corresponded to ‘no effect’, scores of 2–5 to ‘small effect’, scores of 6–10 to ‘moderate effect’, scores of 11–20 to ‘very large effect’ and scores of 21–30 to ‘extremely large effect’. 29

Statistical analyses

Binary end points were analysed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, adjusted by randomization strata. Patients who permanently discontinued the study were defined as non‐responders at all visits after the last observation. Continuous end points were analysed using a mixed‐effect model with repeated measures based on all observed data. The model included factors for treatment group, randomization strata, visit, treatment‐by‐visit interaction, and relevant baseline value. Median times to response were analysed with observed responses (not including patients with missing or censored response data) using empirical methods for confidence intervals (CIs) for quantiles. These analyses were not controlled for multiplicity and no statistical hypotheses were tested.

Results

Patients

Demographics and baseline characteristics were similar among pooled monotherapy patients treated with abrocitinib or placebo (Table 1). Mean (standard deviation) baseline EASI, PP‐NRS, DLQI and CDLQI scores were 28.8 (12.7), 7.0 (1.9), 14.6 (6.9) and 12.7 (6.0) respectively. These baseline values indicate moderate‐to‐severe AD at baseline, and that the disease had a ‘very large effect’ on QoL.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Pooled treatment group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 210) | Abrocitinib | All (N = 942) | ||

| 100 mg (n = 369) | 200 mg (n = 363) | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 35.0 (15.0) | 35.9 (15.8) | 34.1(16.4) | 35.0 (15.9) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| 12–17 years | 25 (11.9) | 51 (13.8) | 48 (13.2) | 124 (13.2) |

| 18–64 years | 178 (84.8) | 297 (80.5) | 289 (79.6) | 764 (81.1) |

| ≥65 years | 7 (3.3) | 21 (5.7) | 26 (7.2) | 54 (5.7) |

| Male, n (%) | 117 (55.7) | 215 (58.3) | 197 (54.3) | 529 (56.2) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 141 (67.1) | 253 (68.6) | 231 (63.6) | 625 (66.3) |

| Black or African American | 22 (10.5) | 31 (8.4) | 30 (8.3) | 83 (8.8) |

| Asian | 39 (18.6) | 80 (21.7) | 85 (23.4) | 204 (21.7) |

| Other | 3 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (1.4) | 10 (1.1) |

| Multiracial | 2 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 8 (2.2) | 12 (1.3) |

| Not reported | 3 (1.4) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.1) | 8 (0.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 11 (5.2) | 14 (3.8) | 12 (3.3) | 37 (3.9) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 196 (93.3) | 352 (95.4) | 349 (96.1) | 897 (95.2) |

| Not reported | 3 (1.4) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.6) | 8 (0.8) |

| Disease duration (years), mean (SD) | 23.5 (15.2) | 23.7 (16.1) | 22.0 (15.1) | 23.0 (15.5) |

| EASI score (%), mean (SD) | 27.6 (11.8) | 29.4 (12.4) | 29.0 (13.4) | 28.8 (12.7) |

| BSA affected (%), mean (SD) | 45.8 (22.1) | 48.6 (22.5) | 47.2 (23.6) | 47.4 (22.8) |

| PP‐NRS | ||||

| No. of patients | 207 | 368 | 362 | 937 |

| Mean (SD) score | 7.0 (1.9) | 7.1 (1.9) | 7.0 (1.9) | 7.0 (1.9) |

| DLQI † | ||||

| No. of patients | 184 | 315 | 311 | 810 |

| Mean (SD) total score | 14.3 (7.2) | 15.1 (7.1) | 14.4 (6.6) | 14.6 (6.9) |

| CDLQI | ||||

| No. of patients | 24 | 48 | 47 | 119 |

| Mean (SD) total score | 12.5 (6.3) | 12.4 (6.4) | 13.1 (5.5) | 12.7 (6.0) |

For patients aged 18 years or more.

AD, atopic dermatitis; BSA, body surface area; CDLQI, Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; PP‐NRS, Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale; SD, standard deviation.

Depth of response to abrocitinib

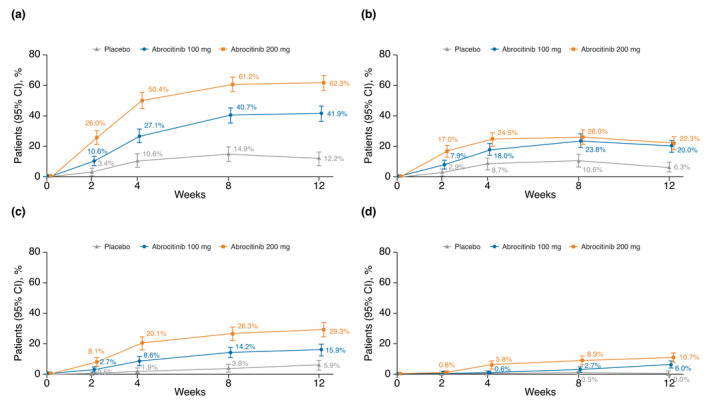

In the pooled analysis, patients treated with abrocitinib had marked improvement in EASI scores compared with placebo. At week 12, the proportions of patients (95% CI) who achieved EASI‐75 response were 62.3% (57.2–67.3), 41.9% (36.9–47.0) and 12.2% (7.7–16.7) for the abrocitinib 200 mg, abrocitinib 100 mg and placebo groups respectively (Fig. 1). At week 12, greater proportions of patients treated with abrocitinib achieved EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 response (22.3% [17.9–26.6], 20.0% [15.9–24.1] and 6.3% [3.0–9.7]) than patients treated with placebo (Fig. 1). Similar trends were found at higher thresholds for EASI response. At week 12, greater proportions of abrocitinib‐treated patients achieved EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 (29.3% [24.6–34.0], 15.9% [12.1–19.6] and 5.9% [2.6–9.1]) (Fig. 1) and EASI‐100 response (10.7% [7.5–13.9], 6.0% [3.6–8.5] and 0% [0–1.8]) compared with placebo for the abrocitinib 200 mg, 100 mg and placebo groups respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD who achieved (a) EASI‐75 response, (b) EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 response, (c) EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 response and (d) EASI‐100 response at weeks 2, 4, 8 and 12. AD, atopic dermatitis; CI, confidence interval; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index.

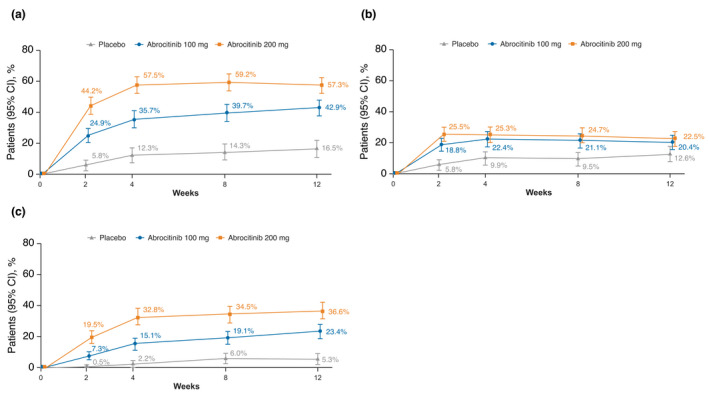

Greater proportions of patients treated with abrocitinib achieved PP‐NRS4 response at week 12 compared with placebo; PP‐NRS4 responder proportions at week 12 were 57.3% (51.8–62.7), 42.9% (37.4–48.3) and 16.5% (11.2–21.8) for the abrocitinib 200 mg, abrocitinib 100 mg and placebo groups respectively (Fig. 2). Among PP‐NRS4 responders at week 12, greater proportions of patients treated with abrocitinib achieved PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS0/1 response (22.5% [17.8–27.2], 20.4% [15.9–24.9] and 12.6% [7.8–17.4]; Fig. 2) and the higher threshold efficacy end point of PP‐NRS0/1 response (36.6% [31.3–42.0], 23.4% [18.7–28.1] and 5.3% [2.1–8.5]; Fig. 2) compared with placebo for the abrocitinib 200 mg, 100 mg and placebo groups respectively.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD who achieved (a) PP‐NRS4 response (≥4‐point improvement from baseline), (b) PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS0/1 response and (c) PP‐NRS0/1 response (baseline score ≥ 2; achieving score < 2) at weeks 2, 4, 8 and 12. AD, atopic dermatitis; CI, confidence interval; PP‐NRS, Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale.

The efficacy of abrocitinib (200 mg and 100 mg) was better than that of placebo for all response thresholds evaluated from week 2 through week 12 (Figs. 1 and 2).

Time to response to abrocitinib

To assess the onset of observed response at the various efficacy thresholds, without overlap with higher threshold efficacy responses, analyses were performed that ‘windowed’ the efficacy responses for EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90, EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100, EASI‐100, PP‐NRS 4 but not PP‐NRS0/1, and PP‐NRS0/1 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Median time (days) to first response based on various efficacy end points

| Days (95% CI) | Pooled treatment group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 211) | Abrocitinib | ||

| 100 mg (n = 370) | 200 mg (n = 364) | ||

| EASI responses | |||

| EASI‐75 | 31.0 (29–57) | 30.0 (29–56) | 29.0 (29–29) |

| EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 | 57.0 (29–85) | 56.0 (30–57) | 56.0 (30–57) |

| EASI‐90 | 79.5 (56–85) | 57.0 (56–58) | 47.0 (30–57) |

| EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 | 79.5 (56–85) | 58.0 (56–85) | 56.0 (31–57) |

| EASI‐100 | 0 | 84.5 (57–86) | 84.0 (56–85) |

| PP‐NRS responses | |||

| PP‐NRS4 | 29.0 (13–58) | 15.0 (11–29) | 10.0 (8–12) |

| PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS0/1 | 29.0 (10–58) | 29.0 (13–57) | 13.5 (9–29) |

| PP‐NRS0/1 | 83.0 (11–85) | 29.0 (28–56) | 14.5 (12–29) |

Median time to response was calculated only among subjects with an observed time of event.

In the pooled analysis for observed EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 responders, median time to onset of response was 56 days for both abrocitinib treatment arms. For the higher threshold efficacy end point of those observed to reach EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100, a similar time to onset of response was observed: 56 and 58 days for abrocitinib 200 mg and abrocitinib 100 mg groups respectively. For the still higher threshold efficacy end point of EASI‐100 response; however, median time to response for observed responders was greater at approximately 84 days for both abrocitinib groups.

In the pooled analysis for observed PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS0/1 response, median time to onset was 13.5 and 29.0 days for the abrocitinib 200 mg and abrocitinib 100 mg groups respectively. For the higher threshold efficacy end point of those observed to reach PP‐NRS0/1 response, median time to onset was similar at 14.5 and 29 days for the abrocitinib 200 mg and abrocitinib 100 mg groups respectively.

Relationship of quality of life with depth of response

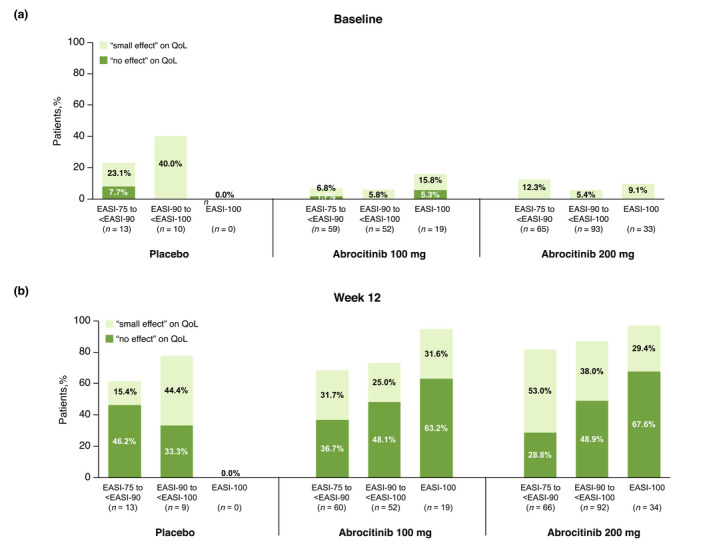

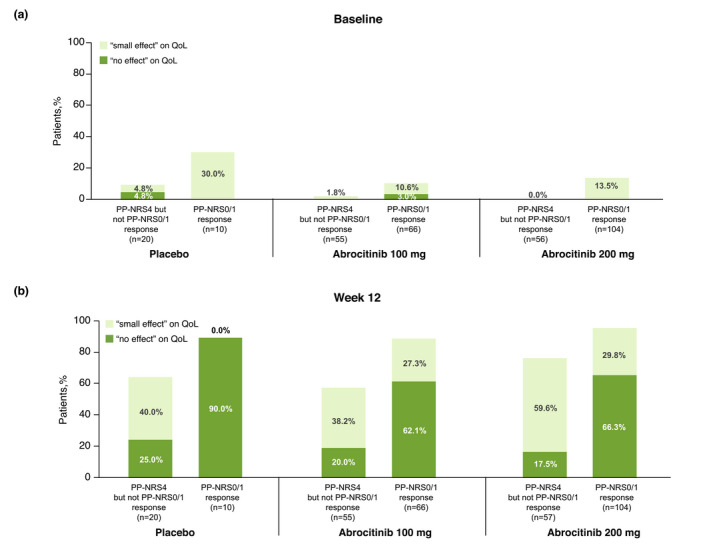

To assess association with QoL outcomes at the various efficacy thresholds, without overlap with higher threshold efficacy responses, analyses were performed that ‘windowed’ the efficacy responses: EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90, EASI‐90‐to <EASI‐100, EASI‐100, PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS0/1, and PP‐NRS0/1 (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Distribution of CDLQI/DLQI severity bands at (a) baseline and (b) week 12 of patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD who achieved EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 response, EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 response and EASI‐100 response at week 12 in the placebo, abrocitinib 100 mg and abrocitinib 200 mg treatment groups. AD, atopic dermatitis; CDLQI, Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index.

Figure 4.

Distribution of CDLQI/DLQI severity bands at (a) baseline and (b) week 12 of patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD who achieved PP‐NRS4 response but not PP‐NRS0/1 response and PP‐NRS0/1 response at week 12 in the placebo, abrocitinib 100 mg and abrocitinib 200 mg treatment groups. AD, atopic dermatitis; CDLQI, Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PP‐NRS, Peak Pruritus Numerical Scale.

At baseline, limited numbers of patients reported small or no effect of AD on QoL (Fig. 3a and Fig. 4a). By week 12, greater proportions of patients reported fewer effects of AD on their QoL, with the greatest benefit on QoL observed among patients experiencing higher threshold EASI and PP‐NRS efficacy responses (Fig. 3b and Fig. 4b). For example, at 12 weeks, 28.8%, 36.7% and 46.2% of patients with EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 for abrocitinib 200 mg, abrocitinib 100 mg and placebo, respectively, reported ‘no effect’ of AD on QoL, compared with 48.9%, 48.1% and 33.3% of patients with EASI‐90‐to <EASI‐100, and with 67.6%, 63.2% and 0% in patients with EASI‐100 (Fig. 3b). Thus, the proportion of patients reporting ‘no effect’ on their QoL by week 12 was more than double (2.34 times) among those achieving EASI‐100 compared with those achieving only EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90.

The difference regarding QoL outcomes was even more marked between patients reaching different PP‐NRS efficacy response thresholds. Approximately four times the proportion of PP‐NRS0/1 responders treated with abrocitinib 200 mg (3.79 times the proportion of responders) reported that their AD had ‘no effect’ on their QoL at week 12, compared with PP‐NRS4 responders who did not achieve PP‐NRS0/1 treated with the same dose (66.3% vs. 17.5%; (Fig. 4b). Similarly, approximately three times the proportion of PP‐NRS0/1 responders treated with abrocitinib 100 mg (3.11 times the proportion of responders) reported that their AD had ‘no effect’ on their QoL at week 12, compared with PP‐NRS4 responders who did not achieve PP‐NRS0/1 treated with the same dose (62.1% vs. 20.0%; Fig. 4b).

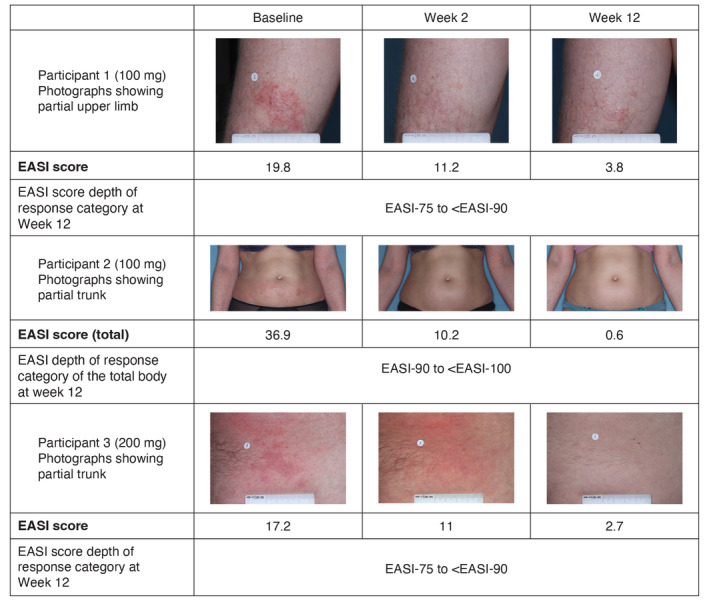

Representative patient cases

Changes in skin involvement in abrocitinib‐treated patients from baseline to week 12 are shown in Fig. 5. One patient who received abrocitinib 100 mg had an EASI score of 19.8 and 3.8 at baseline and week 12, respectively, that qualified as an EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 response. A second patient, who also received abrocitinib 100 mg had an EASI score of 36.9 and 0.6 at baseline and week 12, respectively, that qualified as an EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100 response. A third patient who received abrocitinib 200 mg had an EASI score of 17.2 and 2.7 at baseline and week 12, respectively, that qualified as an EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 response.

Figure 5.

Photographs of patients who received abrocitinib 100 mg at baseline, week 2 and week 12. EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index.

Discussion

The results of these post hoc pooled analyses indicate that substantial proportions of patients with moderate‐to‐severe AD achieve higher threshold efficacy end points (EASI‐90 to <EASI‐100, EASI‐100, or PP‐NRS0/1) with treatment consisting of once‐daily oral abrocitinib (200 mg or 100 mg) monotherapy for 12 weeks. The median time to onset of these higher threshold efficacy responses was similar to that of the commonly used threshold efficacy end points in all treatment arms. The only exception was the highest‐efficacy threshold for EASI (i.e. EASI‐100), which took 1.5 times longer than the commonly used threshold efficacy end point (84 days vs. 56 days). Thus, not only do a substantial proportion of abrocitinib‐treated patients achieve higher threshold efficacy end points but they do so in a similar timeframe as for more commonly used thresholds for efficacy end points. The rapid onset of higher threshold efficacy responses is an important consideration for patients as well as healthcare providers regarding the management of the signs and symptoms of AD, particularly for itch relief.

Importantly, patients who met higher threshold efficacy end points reported clinically meaningful benefits to QoL compared with patients who achieved EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90, or PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS0/1. Achieving higher threshold efficacy responses was associated with larger proportions of patients reporting that their AD has ‘no effect’ on their QoL. 30 This is of particular interest because various treatment guidelines have indicated improvement in QoL is one of the main goals of therapy. 6 , 31 , 32 Interestingly, in the small number of patients who happened to achieve high threshold efficacy responses following placebo treatment, a corresponding improvement in QoL was observed. This further supports the notable impact of attaining high threshold efficacy responses; however, they happen to be attained, on patient QoL. It is important to note, however, that high threshold efficacy responses to placebo treatment were only observed in small number of patients. The superiority of abrocitinib over placebo, both as a monotherapy and in combination with medicated topical therapies for AD, was demonstrated across a spectrum of efficacy end points in several completed, randomized, controlled, double‐blind phase 3 studies. 26 , 27 , 33

The reported improvement in QoL among patients achieving higher threshold efficacy responses may, in part, be explained by patient expectations or goals of treatment for AD. For example, patients with AD desire to achieve complete or almost complete skin clearance and report greater overall self‐perceived importance of complete or almost complete skin clearance, as well as control of itch, when compared with patients with psoriasis. 30 In addition to skin clearance, itch control is also an important treatment aim for patients with AD. 34 Alignment on meeting patient goals that enhance the impact of therapy on QoL, especially in the context of attaining higher threshold efficacy responses in terms of skin clearance and itch, should be important considerations in guiding treatment decisions. There remains a need for better insight into the treatment targets that are important to patients, as this should affect management.

Limitations of these analyses include their post hoc nature, the relatively short duration of the studies (12 weeks) and that formal hypothesis testing was not possible. Nonetheless, these data provide robust evidence for treatment with abrocitinib leading to the attainment of higher threshold efficacy responses, and that these outcomes are associated with clinically meaningful improvements in QoL outcomes when compared with EASI‐75 to <EASI‐90 outcomes, or PP‐NRS4 but not PP‐NRS‐0/1 outcomes. Consideration of treatment benefit should account for the proportions of patients who achieve higher threshold efficacy responses, and associated improvements in QoL. In addition, the CDLQI, originally developed and validated for use in patients aged <16 years was used in patients aged <18 years in this study with the agreement of the instrument's developer. This allowed for alignment with other patient‐reported outcome (PRO) measures included in abrocitinib trials, thereby creating an adolescent PRO measure set and an adult PRO measure set. The use of CDLQI in patients aged up to 17 years has since been shown to correlate closely with DLQI. 35 Future research directions could include characterization of factors that may be correlated with the likelihood of attaining these higher threshold responses with a view towards determining subsets of patients who have the highest likelihood of obtaining these higher threshold efficacy responses following abrocitinib treatment.

Acknowledgements

Editorial and medical writing support under the guidance of authors was provided by Susanna Bae, PharmD (ApotheCom, San Francisco, CA, USA), and was funded by Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:461‐464).

Conflicts of interest

SS is an investigator for Dermasence, Galderma, Kiniksa, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Trevi Therapeutics, Sanofi and Vanda; a member of scientific advisory boards for Beiersdorf, Celgene, Galderma, Kiniksa, Menlo Therapeutics, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals and Trevi Therapeutics; and a consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, BELLUS Health, Bionorica, Cara Therapeutics, Clexio, DS Biopharma, Escient, Galderma, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, Sanofi and Vifor. NB has received financial compensation from Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Almirall, Biofrontera, BioPharmX, Dermira, Dr. Reddy's Laboratory, Encore Dermatology, EPI Health, Ferndale Pharma, Foamix, Galderma, IntraDerm, ISDIN, LaRoche‐Posay, LEO Pharma, Mayne Pharma, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pierre Fabre, Regeneron, Sanofi, SkinFix, Soligenix, Sun Pharma, Vidac Pharma and Vyome Therapeutics. MJG has received grants, personal fees, honoraria and/or non‐financial support from Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Amgen, Akros Pharma, Arcutis, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Dermira, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron, Sun Pharma, UCB Pharma and Bausch Health (Valeant). JIS is an investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GSK, Kiniksa, LEO Pharma, Menlo Therapeutics, Realm Therapeutics, Regeneron, Roche and Sanofi; a consultant for Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Anacor, AnaptysBio, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Asana BioSciences, Dermira, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GSK, Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Kiniksa, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Realm Therapeutics, Regeneron and Sanofi; a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi; and is on advisory boards for Pfizer Inc., Dermira, LEO Pharma and Menlo Therapeutics. JPT is an advisor/investigator or speaker for Pfizer Inc., AbbVie, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Regeneron, Almirall and Sanofi‐Genzyme. He has received grants from Regeneron and Sanofi‐Genzyme. PB, MD, WR and SAF are employees and stockholders of Pfizer Inc.

Funding sources

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to publication of their case details.

Data availability statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de‐identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

References

- 1. Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population‐based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132: 1132–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williams H, Robertson C, Stewart A et al. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103: 125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross‐sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139: 583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population‐based cross‐sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 121: 340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thyssen JP, Andersen Y, Halling AS, Williams HC, Egeberg A. Strengths and limitations of the United Kingdom working party criteria for atopic dermatitis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 1764–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Guttman‐Yassky E, Ong PY, Silverberg J, Farrar JR. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 120: 10–22.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 70: 338–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ et al. Symptoms and diagnosis of anxiety and depression in atopic dermatitis in U.S. adults. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181: 554–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng BT, Silverberg JI. Depression and psychological distress in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019; 123: 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Girolomoni G, Luger T, Nosbaum A et al. The economic and psychosocial comorbidity burden among adults with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis in europe: analysis of a cross‐sectional survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021; 11: 117–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu SH, Attarian H, Zee P, Silverberg JI. Burden of sleep and fatigue in US adults with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis 2016; 27: 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, Fishbein AB, Zee PC. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population‐based study. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135: 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li JC, Fishbein A, Singam V et al. Sleep disturbance and sleep‐related impairment in adults with atopic dermatitis: a cross‐sectional study. Dermatitis 2018; 29: 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matterne U, Apfelbacher CJ, Loerbroks A et al. Prevalence, correlates and characteristics of chronic pruritus: a population‐based cross‐sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol 2011; 91: 674–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kini SP, DeLong LK, Veledar E, McKenzie‐Brown AM, Schaufele M, Chen SC. The impact of pruritus on quality of life: the skin equivalent of pain. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147: 1153–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patel KR, Immaneni S, Singam V, Rastogi S, Silverberg JI. Association between atopic dermatitis, depression, and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pfizer . Cibinqo 100 mg film‐coated tablets (summary of product characteristics). URL https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/12873/smpc [updated 09/10/2021] (last accessed 22 February 2022).

- 18. Pfizer . Japan's MHLW approves Pfizer's CIBINQO® (abrocitinib) for adults and adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. URL www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/japans-mhlw-approves-pfizers-cibinqor-abrocitinib-adults [updated 09/30/2021] (last accessed 22 February 2022).

- 19. European Medicines Agency . CIBINQO® (abrocitinib). Summary of product characteristics (SmPC). Pfizer Europe MA EEIG, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pfizer Inc . CIBINQO (Abrocitinib) Tablets, for Oral Use [Prescribing Infromation]. 01/2022. Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bao L, Zhang H, Chan LS. The involvement of the JAK‐STAT signaling pathway in chronic inflammatory skin disease atopic dermatitis. JAKSTAT 2013; 2: e24137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O'Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev 2009; 228: 273–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mollanazar NK, Smith PK, Yosipovitch G. Mediators of chronic pruritus in atopic dermatitis: getting the itch out? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016; 51: 263–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J et al. Sensory neurons co‐opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell 2017; 171: 217–228e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gooderham MJ, Forman SB, Bissonnette R et al. Efficacy and safety of oral janus kinase 1 inhibitor abrocitinib for patients with atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2019; 155: 1371–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2020; 156: 863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO‐1): a multicentre, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020; 396: 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastey V et al. Peak pruritus numerical rating scale: psychometric validation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181: 761–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125: 659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Factors associated with patient‐reported importance of skin clearance among adults with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 81: 943–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014; 71: 327–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simpson EL, Bruin‐Weller M, Flohr C et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the international eczema council. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 77: 623–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eichenfield LF, Flohr C, Sidbury R et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in combination with topical therapy in adolescents with moderate‐to‐severe atopic dermatitis: the JADE TEEN randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2021; 157: 1165–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Augustin M, Langenbruch A, Blome C et al. Characterizing treatment‐related patient needs in atopic eczema: insights for personalized goal orientation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Geel MJ, Maatkamp M, Oostveen AM et al. Comparison of the dermatology life quality index and the Children's dermatology life quality index in assessment of quality of life in patients with psoriasis aged 16‐17 years. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174: 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de‐identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.