Abstract

Very few empirical evaluations have been conducted on the impact of furniture on the lives of those who have transitioned from homelessness into permanent housing, especially within the United States. Our study contributes to this limited body of research by exploring the impact of furniture on the lives of 20 recently housed individuals residing in the Detroit Metropolitan Area. In partnership with the Furniture Bank of Southeast Michigan, we conducted semi‐structured interviews with recently housed individuals that lived for a period of time in an un‐ or under‐furnished house before receiving furniture support. Given the study's exploratory nature, interview questions were purposefully broad to allow themes to naturally emerge and were analyzed using a qualitative data analysis software package, NVivo (release 1.0). We present a conceptual model that outlines our findings and conclude with a discussion of the limitations of our approach, avenues for future research, and policy implications.

Keywords: furniture, health, homelessness, place attachment, restorative environment, qualitative research, un‐furnished homes

1. INTRODUCTION

The positive impact of furniture among those transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing has been readily acknowledged by service providers but has received little empirical consideration, especially within the United States (US). Despite its reported benefits (Ambrose et al., 2016; End Furniture Poverty, 2021; Richards, 2007; Shelter Scotland, 2010), furniture has yet to be recognized as a basic need by any official US source. Given its unique social and economic landscape (Culhane et al., 2020; Fitzpatrick & Christian, 2006), we argue that there is a clear need to better understand the impact of furniture on underserved, low‐income populations within the United States. Such an evaluation can raise awareness on the importance of furniture among those transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing and support its recognition as a basic need. It can also address gaps in our understanding of how furniture impacts the lives of the recently housed. To this end, we conducted 20 semi‐structured interviews with recently housed individuals who received furniture from the Furniture Bank of Southeast Michigan, a nonprofit organization that provides furniture at little to no cost to individuals and families. Interview questions were informed by a review of the literature. Although limited, this review informed our decision to explore the impact of furniture on place attachments, a relationship that has not been explicitly considered by earlier research. Furthermore, we applied a qualitative data analysis approach to identify and explore themes across participants' responses. Our review highlights the importance of furniture in enhancing physical, mental, and social health, as well as its role in facilitating place attachments and achieving goals. Based upon these findings, we offer policy‐relevant recommendations in an effort to improve and expand the breadth and scope of community‐based programs and services aimed at improving the overall functional health and wellbeing of the recently housed, as well as the health of communities. Our study concludes with a discussion of opportunities to advance this underdeveloped area of research.

1.1. The benefits of furniture: Transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing

A limited body of research considers the role of furniture among those transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing. In the most recent peer‐reviewed study to date, Hartwig and Mohamed (2020) conducted semi‐structured interviews with 20 recipients of furniture and other household items from a charitable organization in the United States. Based upon a qualitative assessment of participant responses, they identified an array of benefits associated with living in a furnished house, as captured by four themes: respect, creating a home, physical comfort, and emotional well‐being. In summary, participants associated the quality of the furniture and cost savings with safeguarding their dignity. Furthermore, participants indicated that furniture helped them secure a sense of normalcy and afforded them the ability to host visitors, components associated with creating a home. Participants also noted fewer pains and aches upon receiving the furniture, as well as reduced levels of stress, anxiety, and depression.

To varying degrees, evidence of these benefits are found in similar evaluations, the bulk of which were conducted in the United Kingdom (UK) (Ambrose et al., 2016; End Furniture Poverty, 2021; Richards, 2007; Shelter Scotland, 2010). Of particular interest, End Furniture Poverty (2021), a campaign led by a charitable organization in Liverpool, England, UK, facilitated 25 interviews of recipients of furniture support in an effort to capture its social return. These interviews revealed that recipients worried less about money and were better able to provide for their families. Similar to Hartwig and Mohamed (2020), recipients associated the receipt of furniture with improvements in their physical and mental health, as well as in creating an environment that felt more like home.

The End Furniture Poverty (2021) study further revealed that recipients of furniture support were more likely to invite visitors over to their homes and felt less isolated. By encouraging social interactions through which trust and shared expectations for informal social controls can develop, these benefits may encourage the development of collective efficacy. Defined as the ability of residents to leverage social ties to achieve common goals (Sampson et al., 1997; Sampson, 2006); collective efficacy has been found to mediate the relationship between traditionally understood antecedents of crime, including concentrated disadvantage and residential stability (Burchfield & Silver, 2013; Maxwell et al., 2018; Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999).

Adding to these findings, an earlier analysis conducted by Richards (2007) in Liverpool found that the financial gains afforded by furniture allowed recipients to be able to spend more time to pursue other goals, such as gaining employment. Although not focused explicitly on furniture, a larger body of evidence supports the impact of housing quality on physical, mental, and social health (Baker et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2003; Gifford & Lacombe, 2006). When considered together, these studies strongly support the value of living in a furnished home, especially among the recently housed.

While research supports the value of furniture in creating a home, this theme has only been loosely connected to place attachment and its related benefits. Williams et al. (1992, p. 4) were among the first to suggest the importance of furniture for place attachment theories: “Physical space becomes place when we attach meaning to a particular geographic locale, be it a chair in the living room; one's home, neighborhood, city, or nation; or a variety of spaces in between.” Place attachment theories consider the emotional and symbolic ties that are manifested from one's attachment to home, neighborhood, and community (Williams et al., 1992). Environmental psychologists have added two dimensions: place‐dependence and place‐identity. Place‐dependence is related to the functional attribute of a particular place that allows individuals to achieve their goals (Stokols & Shumaker, 1981), while place‐identity captures how individuals' identities are linked to qualities of the physical environment that impact their memories, feelings, or attitudes (Proshansky, 1978).

The place attachment model has recently undergone further adaptation. Scannell and Gifford (2010) have proposed a tripartite model that is based on three dimensions: person, process, and place. The person dimension captures the symbolic meaning a place holds to an individual or a group. These experiences are important in forming the basis of attachment (Manzo, 2005; Scannell & Gifford, 2010). The process dimension highlights the role affect (love, hate, fear, etc.), cognition (thoughts, beliefs, memories, etc.), and behavior (or action) play in forming place attachments. For place attachment to occur, the affective and cognitive components must be positive (Hinds & Sparks, 2008; Scannell & Gifford, 2010). Finally, the place dimension captures the social interactions afforded by a place and its physical aspects that are of value to an individual or group, with the strength of attachment varying by spatial level (home, neighborhood, city, etc.).

Place attachments generally grow stronger the longer an individual spends in a place (Bailey et al., 2012; Moore & Graefe, 1994; Vorkinn & Riese, 2001). Given this finding, research on tenancy sustainment can offer insight into the role of furniture in cultivating attachments. Studies showed that lack of furniture has been identified as a key reason for not sustaining tenancy as evidenced in individuals and families spending more time living in shelters (Pawson et al., 2006; Pawson & Monroe, 2010; Shelter Scotland, 2010; Simiriglia, 2019). In a review of UK tenancy programs facilitated by End Furniture Poverty (2021), programs that provided furnished accommodations retained tenants for a longer period of time than their counterparts. Contrary to these findings, Warnes et al. (2013) longitudinal assessment of 400 recently housed individuals failed to find evidence connecting furniture with sustained tenancy. As supported by Tsai et al. (2012), lack of control was found to play a leading role in tenancy sustainment. This finding suggests that the ability to administer control through the selection of furniture may play an important role in tenancy sustainment (Ambrose et al., 2016).

In addition, furniture may contribute to place attachments by creating restorative environments (Liu et al., 2020; Ratcliffe & Korpela, 2016, 2018; Ulrich, 1983), defined broadly as an environment that triggers physical, mental, and/or social process/es of recovery (Joye & van den Berg, 2018). In addition to these benefits, studies have demonstrated a strong link between an individual's attachment to place and community participation (Mesch & Manor, 1998), goal attainment (Shumaker & Taylor, 1983), and overall well‐being (Harris et al., 1995). These attachments have been found to vary across lived experiences, with individuals who have experienced hardship, such as the recently housed, developing stronger place attachments (Relph, 1976; Taylor & Townsend, 1976). Furthermore, individuals who have negative attachments to their home, which may occur if they have little to no furniture, are more likely to experience adverse health outcomes (Stokols & Shumaker, 1981). They are also more likely to move out of their neighborhoods and contribute to residential instability, a factor linked to the disruption of social support and elevated crime levels (Boggess & Hipp, 2010; Riina et al., 2016; Twigger‐Ross & Uzzell, 1996). Since furniture contributes to meeting Maslow's (1943) physiological, physical, social, and esteem needs, we propose in this paper that there is an explicit relationship between the receipt of furniture and place attachment through meeting basic, psychological, and self‐fulfillment needs.

By strengthening attachments to place, the receipt of furniture also stands to have significant economic value. To this point, the impact of homelessness on government expenditures is severe and far‐reaching. A recent assessment conducted by the National Alliance to End Homelessness (2017) estimated a cost of $35,578 per unhoused person per year, a figure that considers the cost of crisis services (e.g., shelters, jails, and hospitals). When coupled with permanent housing and other supportive services, furniture provisions may help secure cost savings through their positive influence on tenancy sustainment (Culhane & Byrne, 2010; Culhane et al., 2002; Kenway & Palmer, 2003; National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2017; Pleace, 2015).

1.2. Furniture banks: A source of furniture

Based in the United States and Canada, Furniture Banks are charitable organizations that provide gently used household furnishings to individuals and families in need. One way in which Furniture Banks identify those in need of furniture support is through referrals from housing service providers. In this way, those transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing can leverage the benefits afforded by Furniture Banks. In addition to providing furniture at little to no cost, this method of obtaining furniture for the recently housed has four key benefits. First, the furniture available for selection at Furniture Banks is vetted to be of good quality. Furniture items found on the curbside for trash pickup, for example, are unlikely to meet the same standards. Second, it is common practice for Furniture Banks to provide recipients the opportunity to select their own furniture items. This opportunity helps ensure that the selected items meet recipients' needs and preferences, benefits that are less certain when obtaining furniture from the trash. Third, it is also common practice for Furniture Banks to deliver furniture to recipients' houses, saving them the cost associated with transportation and the hassle of moving heavy items. Fourth, Furniture Banks help protect the environment by diverting gently used household furnishings from landfills. This environmental benefit is incentivized through tax‐deductions for furniture donations.

While Furniture Banks have helped ease the transition from homelessness for thousands of individuals and families, furniture has yet to be recognized as a basic need by any official US source. Often seen as the standard for assessing self‐sufficiency, the Arizona Self‐Sufficiency Matrix identifies 18 domains that gauge the ability of an individual or family to live without the need for various supports and human services (Culhane et al., 2008). It is reasoned that the absence or presence of furniture has implications for half of these domains, including housing, employment, income, family/social relations, community involvement, parenting skills, mental health, safety, and disabilities. However, none of these domains make a direct reference to furniture. The absence or presence of furniture also has implications for maintaining a Continuum of Care (CoC) for homeless individuals and families. The CoC is a comprehensive program through the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that focuses on ending homelessness, easing the transition from homelessness into permanent housing, and optimizing self‐sufficiency (HUD Exchange, 2022). Like the Arizona Self‐Sufficiency Matrix, the CoC makes no direct reference to furniture.

1.3. Current study

This study aims to identify the benefits associated with furniture among those transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing in an effort to inform policy and practice on the care of the recently housed. Albeit limited, our review of the literature informed four research questions: (1) How does furniture impact the physical, mental and social health of recipients?; (2) What role does furniture play in forming place attachments?; (3) What role does furniture play in the achievement of goals?; and more broadly, what are the experiences of living in an un‐ or under‐furnished house? Our study contributes to research on the challenges facing vulnerable individuals and families living with little or no furniture in two notable ways. First, our focus on a predominantly African American population living in the United States helps broaden the scope of the current state of the research, which predominately consists of evaluations that are conducted in dissimilar contexts. Second, our study takes a more focused look at the role of furniture in forming place attachments. Third, in our review of literature, we found that furniture was loosely connected to place attachment and its related benefits. And lastly, the bulk of research evaluating the benefits of furniture was performed in the United Kingdom.

To conduct our evaluation, we partnered with the Furniture Bank of Southeastern Michigan (FBSM). The FBSM was founded in 1968 by a group of local churches and volunteers seeking to help vulnerable individuals and families in Wayne County, including the city of Detroit. The FBSM provides furniture to individuals transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing through referrals from the Community Housing Network (CHN), a nonprofit organization that helps transition individuals and families experiencing homelessness into permanent housing. In 2019, the FBSM provided over 2100 families with furniture. While this figure is astonishing, the FBSM suspects—based upon estimates of those living in poverty in the communities it serves—that the need for furniture is far greater. Although the FBSM routinely collects information on program outputs, the organization has never conducted a formal evaluation on the impact of furniture on the population it serves.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study description

The study was conducted in December 2019 and was funded by the home university of the lead author. In an effort to obtain rich data, we adopted a purposive sampling strategy, identifying study participants through the CHN. This sampling strategy resembles a homogenous sampling method; the sample population was identified based upon their membership to a particular subgroup with shared characteristics (Patton, 2015). To this point, all participants had experienced homelessness before receiving housing assistance through the CHN and are members of vulnerable populations.

Before receiving furniture from the FBSM, all participants had recently transitioned from homelessness into permanent housing and lived for a period of time (from 2 weeks up to 3 months) in an un‐ or under‐furnished house. We define an un‐furnished house as a house or apartment unit with no furnishings or a meager set of substitute items, such as sleeping bags or card chairs, that have limited function and comfort. An individual who lives in an un‐furnished house is sleeping, eating, and living either exclusively or functionally on the floor. In contrast, an under‐furnished house is a house or apartment with some furniture and possibly substitute items, but not enough for an individual to live functionally or comfortably. Examples include a family of six living with three beds, or an individual who only has a desk and chair in their house.

We used a semi‐structured interview approach to explore the experience of receiving furniture and its associated benefits. At the start of an interview, each participant was provided a brief description of our research objectives and asked to sign a consent form approved by the home university's Institutional Review Board. All participants received a $40 gift card in return for their participation. Participants were interviewed for approximately a half‐hour and responded to eight sets of questions (see Table 1). Given our study's exploratory nature, interview questions were purposefully broad to allow themes to naturally emerge and develop throughout the course of each interview. Researchers were encouraged—when appropriate—to ask follow‐up and probing questions to help reveal emerging themes, as well as to gain a better understanding of participants' responses.

Table 1.

Questionnaire for recipients of furniture from the Furniture Bank of Southeast Michigan (FBSM)

| 1. Tell me about the experience you had getting furniture from the FBSM. |

|

| 2. What was the most difficult thing about living in your home before you received your furniture? |

|

| 3. Did your quality of life improve after receiving assistance from the FBSM? |

|

| 4. Do you think you have more attachment to your home now that it's furnished? |

|

| 5. Besides furniture, are there things that you think added to your feelings of attachment to your home? |

|

| 6. Besides furniture, are there things that take away from your feelings of attachment to your home? |

|

| 7. Is your home the place where you feel most relaxed and content? |

|

| 8. What achievements have you made since receiving furniture from the FBSM? |

|

Note: Bullet points proceed probes and related follow‐up questions used to facilitate richer responses.

Interviews were conducted at the FBSM and a local community center by the research team, which consisted of five subject‐matter experts in the fields of restorative environments, community health, criminology, and human development. Four members belonged to a university and one member was an employee of the FBSM. To help prevent biased responses, each interview was attended by at least two members of the research team. These locations were selected because of their proximity to participants' home addresses. A total of 136 individuals were contacted and invited to participate in the interview. Interviews were suspended after reaching theoretical saturation, resulting in a final sample size of 20 (see Table 2). Although this sample size may seem small, it is larger than the recommended number of data sources for homogenous populations and what is thought to be sufficient to achieve a rich understanding of experiences (see Kuzel, 1992; Morse, 1994). The majority of participants were between the ages of 47 and 57 (35%) and identified as female (75%) and African American (70%). They also had an annual income of under $10,000 (80%), were not in the labor force (50%), and did not receive disability benefits (55%). All but one participant lived in a household in which they were the only adult (95%) and a little over half of the participants had children (55%).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics

| Variable | N |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 25–35 | 6 |

| 36–46 | 6 |

| 47–57 | 7 |

| 58–68 | 1 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 15 |

| Male | 5 |

| Annual income level | |

| Under $10,000 | 16 |

| Over $10,000 | 4 |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 14 |

| Hispanic | 1 |

| White | 4 |

| Other | 1 |

| Adults in household | |

| One | 19 |

| More than one | 1 |

| Children in household | |

| None | 9 |

| 1–3 | 7 |

| 4–6 | 4 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 2 |

| Unemployed | 8 |

| Not in labor force | 10 |

| Disability | |

| Yes | 9 |

| No | 11 |

After each interview, the research team convened in a small meeting room to review their research notes and observations in an effort to identify themes and meaning units to be used for coding purposes. A thorough reading of the interview transcripts later accompanied this process. At the study's completion, the research team met to review and discuss the data collected before proceeding with deeper analysis. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed by a certified court reporter using CaseViewer software.

Data analysis was approached using an initial coding technique in NVivo (release 1.0). The goal of initial coding is to allow themes and concepts to naturally emerge, building a theoretical framework for further exploration (Glaser, 1992). To start, a single researcher developed a codebook, which was later refined through an iterative, dual coding process. Using this codebook, two researchers independently performed all data coding to ensure internal reliability and consistency of the analysis. Interview transcripts were read multiple times, during which recurring themes and subcategories were identified and coded. The researchers then met to compare codes and discuss discrepancies until an agreement could be reached (Glaser, 1992). Importantly, the researchers took great care to ensure that the themes and subcategories that were identified were representatives of the common experiences of participants. Grounded theory methods, such as the identification of deviant cases, were also used to ensure representation (Strauss, 1987).

3. RESULTS

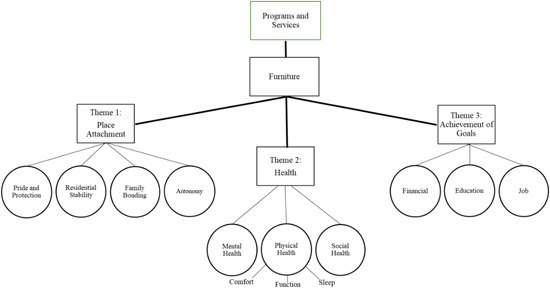

All participants identified living in an un‐ or under‐furnished house as a condition that negatively impacted their lives and attributed the receipt of furniture with positive improvements. To demonstrate this point, Figure 1 summarizes the experiences and milestones of John, a 35‐year‐old African American male. John lived at various shelters before transitioning to permanent housing. Upon receiving housing, he was dismayed to find that his house was un‐furnished. According to John, Living in a shelter [with furniture] was better than having my own place without furniture. Confined to sleeping on the floor, John often went to a friend's house to be able to sleep more comfortably on a sofa. Without furniture to accommodate visitors, John was reluctant to invite anyone over to visit. After receiving furniture, John's quality of life greatly improved. He socialized more often with friends and family at his home where he felt the most comfortable. The receipt of furniture also allowed John the ability to focus more on other goals, including working toward receiving his high school diploma.

Figure 1.

John's summary of experiences with receiving furniture

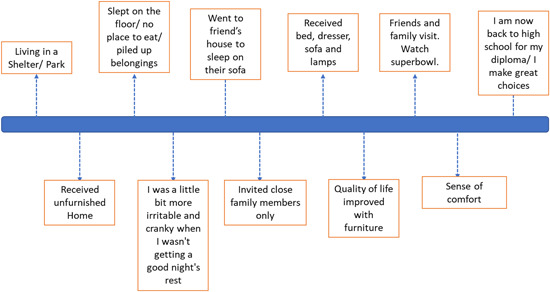

While John's story is just one of many, it captures the key themes and related subcategories that emerged throughout our interviews. It also showcases the distinction between living in an un‐ or under‐furnished house versus a furnished house, with the receipt of furniture serving as a “turning point.” In the discussion that follows, this distinction is evaluated across three related themes, capturing the dimensions of participants' lives that were affected by the receipt of furniture: place attachment (pride and protection, autonomy, family bonding, residential stability), health (mental health, physical health, and social health), and achievement of goals (financial, education, and job). Figure 2 displays a conceptual model—an organizing framework—that illustrates the connections between these themes and related subcategories.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework showing the connections between furniture and other dimensions

3.1. Theme 1: Place attachment

All participants recognized the transition from homelessness into housing as a life‐changing event that improved their quality of life. However, this milestone brought with it a new set of challenges. Participants described having no beds in which to sleep, chairs or sofas on which to sit or rest, and tables on which to share family meals. Their experiences living in an un‐ or under‐furnished house gave them a new perspective from which to reflect upon their experiences living in a homeless shelter. Jason remarked:

…[e]ven when I was staying in the shelter I still was able to have a bed, you know, still had sofas and stuff we could sit on. So then when I had my own place and I still didn't have that type of stuff it was like, oh, you were kind of living better in the shelter than in your own place.

With the addition of furniture, participants' living conditions were elevated far beyond those afforded by a homeless shelter. Furniture helped establish a sense of permanency not experienced since before being homeless. As discussed by Anita, nearly all participants attributed receiving furniture to a greater level of attachment to their homes: “It's okay to just relax and know that this is your home. You're not leaving. You don't have to go anywhere.”

3.1.1. Pride and protection

Participants remarked that the joy and relief of having a space to call their own was diminished by the fact that it did not contain much, if any, furniture. Participants equated an un‐ or under‐furnished home with vulnerability, epitomized as the inability to provide for themselves and their families. To this point, Barbara described how she was affected when her and her children lived without beds: “… as a mom, that hurts your whole pride…because it's like no matter what I can sleep on the floor, they're not supposed to be sleeping on the floor.” With the receipt of furniture, participants not only took pride in the space that they had cultivated for themselves, but also became more protective of them. As emphasized by Sara, protection of their homes was seen as vital to preserve the stability and success they had achieved since experiencing homelessness: “…the wrong vibe in your home, it don't matter how nice and pretty it is, it could all disappear. So, I protect my home.”

3.1.2. Autonomy

Personalization of their homes through the selection and arrangement of furniture allowed participants to exercise their autonomy, which was previously stifled by the rules that accompanied living in a homeless shelter. Janet discussed how she enhanced the appearance and feel of her home to create a more welcoming environment: “I started… doing more things, decorating the house more. It just made it more welcoming to have furniture in your house.” While all participants noted that the receipt of furniture helped improve the functionality and comfort of their homes, participants who selected their furniture from the Furniture Bank expressed a stronger attachment to the selected pieces, as compared to those who were unable or did not care to select their furniture. The condition of the furniture also played a similar role. Participants expressed a stronger attachment to furniture they perceived to be in good condition as compared to furniture they perceived to be of lesser quality.

3.1.3. Family bonding

Participants with children were keen to discuss how living in an un‐ or under‐furnished house detracted from the time they spent together as a family. With no place to comfortably gather, their children spent more time away from home and outside of the view of their watchful eyes. To this point, Vanessa described how not having furniture affects families:…it's the glue to help keep families sticking together because that can be a frustrating situation [living without furniture]. Like, I've seen some of my other friends [that have] teenagers, and they didn't have beds and [the] teenager is like, well, I ain't coming home today.

By providing function and comfort, furniture transformed participants' living conditions into meaningful spaces that they and their children could enjoy and take pride in. Their homes now contained everything that they needed: a bed in which to sleep, chairs and sofas on which to sit or rest, and tables on which to share family meals. As a result, participants and their children spent more time at home.

3.1.4. Residential stability

Furniture created a restorative environment that provided a respite from the adverse effects of neighborhood conditions that impact residential stability. While not the majority, several participants expressed a desire to relocate. “Once I walk in my door, it's just. it's mine. This is my home,” Mark exclaimed. “Outside of my door, I don't like it. I'm ready to move, it's that—it's just where I'm at.” Participants identified high crime rates and poor access to high‐quality services as leading factors influencing their desire to find new housing elsewhere. These participants viewed their current living arrangements as temporary until they could find housing in a more desirable neighborhood. Conversely, a low crime rate, a desirable school system, and close proximity to family, friends, and services underlaid participants' attachments to their homes, promoting residential stability. For example, Martha described her preference to remain in a certain neighborhood when working with CHN to find housing: “I was desperate to stay in [neighborhood name redacted]. It is the school system my daughter started out in. It was a Godsend that we found a place.” When asked what contributed to her feelings of attachment to her home, Donna replied that her neighborhood played a lead role and identified several of its positive qualities:

Since I've been here [in my neighborhood] my quality of life has improved a lot. I've met friends actually, um, because of my location. [E]verything's close around me. Everything. The grocery stores are close. It's like right down the street we have like a little mini mall. Parks are around here.

Regardless of neighborhood conditions, all participants attributed furniture as playing a lead role in creating a restorative environment; an environment in which they felt insulated from the outside world, and the most relaxed and content. Like many others, Ada attributed furniture to these feelings, further remarking “[I] can go home and actually relax. You know, it's wonderful that you can go home and you feel safe. Whatever may be going on around me, this is my place.” Participants who did express a desire to move all agreed that they would bring their furniture with them, allowing them to transform their new spaces into restorative environments.

3.2. Theme 2: Health

An un‐ or under‐furnished house created an environment in which participants were unable to adequately restore depleted resources required for the maintenance and promotion of their health. These resources span across mental, physical, and social health domains, with the receipt of furniture attributed to positive improvements.

3.2.1. Mental health

Participants attributed moving into permanent housing as alleviating many sources of stress that they experienced while homeless. Nonetheless, these experiences left an impact on participants' mental health. The transition to permanent housing marked the beginning of participants' recovery process. Before receiving furniture, however, participants struggled to find comfort in homes that lacked functionality, a condition that delayed their recovery process and contributed to negative emotions. Janet expressed that “…it was depressing. It was depressing because you can't get comfortable.” The receipt of furniture provided participants both the comfort and function needed to create a restorative environment to the benefit of their mental health.

3.2.2. Physical health

Sleeping on the floor is far from comfortable. The physical discomfort experienced by participants prevented them from achieving restful sleep, which in turn negatively affected their mental health. A participant expressed, "I have fibromyalgia, arthritis, and sciatica—so sleeping on the floor was not fun, at all.” Contributing to matters, the majority of female participants in our sample identified as the sole providers of their households. As such, their health is especially of importance; their families' well‐beings depend on it. The physical discomfort associated with sleeping on a hard surface also had adverse effects for participants' children. Unable to sleep comfortably, their children struggled to stay attentive during school, which negatively affected their school performance. In light of these findings, it is unsurprising that participants identified beds as the most impactful item of furniture they received from the FBSM, followed by sofas, tables, and chairs.

3.2.3. Social health

Participants' social interactions were greatly restricted as a consequence of the functional limitations of living in an un‐ or under‐furnished home. With little to no furniture, they could not comfortably host family or friends. Lucia remarked, "It was depressing. It was depressing because you can't get comfortable… no way to sit or to lay down. You know, and couldn't invite nobody into your place.” As discussed by Erika, participants also identified their meager living conditions as a source of shame, which reinforced their social isolation: “I mean when you don't have anything you're kind of embarrassed to bring anybody over, you know. What do you have? Yeah, come in and see nothing.” Upon receiving furniture, participants began inviting family and friends over more often to socialize, even making new friends within their neighborhoods. Muriel discussed the benefit of having beds on which her grandchildren could sleep: “I love my grandchildren and they're always over. They're my joy, and if I didn't have anything for them to sleep on we, they probably wouldn't be there. Their moms wouldn't let them stay.”

3.3. Theme 3: Achievement of goals

The receipt of furniture at little to no cost afforded participants the opportunity to pursue and achieve goals in the areas of personal finances and education, while permanent housing played a lead role in their efforts to secure employment.

3.3.1. Financial

Without receiving assistance from the Furniture Bank, participants would have been faced with the full financial cost of furnishing their home. Living in poverty, the expense of a fully furnished house would have required them to make great sacrifices to the determinant of other necessities, such as food, clothing, health care, and education. The added strain to participants' finances would have served to entrench them even further into poverty. While forgoing furniture would have saved participants from this expense and its consequences, it would have deprived them of the associated mental, physical, and social health benefits of a fully furnished home. Providing furniture to participants at little to no cost saved them from the financial burden of furnishing their homes. Together, the financial savings accrued and the benefits of living in a fully furnished home enabled participants to have a better quality of life. To this point, Jack said, “I mean, but you know, you guys helping out, I mean it helped with the expenses and helped me be able to put my money where it needs to go.” Meredith discussed how she used the money that would have been spent on furniture to pay rent and purchase a car that later helped her secure a job:

It helped with the expenses and helped me be able to put my money where it needed to go: rent and getting a car. When you don't have a car you can't get nowhere. And the car absolutely has helped me out and I was able to get that, like I was saying, because I didn't have to worry about spending the money on the furniture. You know, which helped me get my job.

3.3.2. Education

Participants identified how receiving furniture through the Furniture Bank inspired them to set goals for themselves. Foremost among these goals was pursuing further education. Michael exclaimed, “I'm going back to school! So pretty much just gave me a different feeling.” As recounted by Sheryl, a furnished home also created an environment that supported education by providing a comfortable environment in which to sleep, eat, and study:

… because my kids sleep better, they've got a table to sit and eat and do homework. Like we're able to function as a normal family. And not having no furniture, you all really realize how simple a desk or this chair is.

3.3.3. Job

Since receiving furniture, many participants had either attained or expressed a desire to attain employment. Secure housing played a lead role in this regard. For example, Joanna was unable to address her health issues while she was living in a homeless shelter. Since receiving permanent housing, she is now able to do so and expressed a desire to find a job: “I would like to get a job, but I am working on my health issues…. but being in a place has allowed me the room to work on these other things now.”

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our study recounts the experiences of 20 recently housed individuals after they had received permanent housing through the CHN and furniture from the FBSM. Our findings parallel those of early examinations of those transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing, with the added benefit of a more detailed examination of the role of furniture in facilitating place attachments. Overall, our study strongly supports that the receipt of furniture contributes to place attachment and advances participants' overall quality of life as seen through improvements in their mental, physical, and social health, as well as their ability to pursue and achieve goals.

Regarding place attachment, participants experienced a greater level of attachment to their houses after receiving furniture, a finding suggested by tenancy sustainment studies (Pawson et al., 2006; Simiriglia, 2019; Shelter Scotland, 2010). Furthermore, our understanding of the role of furniture in facilitating these attachments conforms to Scannell and Gifford's (2010) tripartite model. To start, the receipt of furniture played an instrumental role in facilitating affective, cognitive, and behavioral attachments, components of the process dimension. In particular, participants attributed the receipt of furniture to creating an environment in which they felt the most relaxed and content, capturing the affective component; furniture helped create an environment that felt more like a home. Comparisons drawn between living in a shelter and living in an un‐ or under‐furnished house highlight the role of cognition in forming attachments. If their house was unfurnished, participants were more likely to express attachment to a place that provided furniture, such as a shelter or a friend's home. Lastly, participants' and their children's behaviors changed after receiving furniture. Most notably, they spent more time at home now that it was made both more comfortable and functional by the addition of furniture. Regarding the person and place dimensions, furniture gave new meaning to participants' homes, symbolizing qualities such as permanency and autonomy that are known to positively contribute to restorative experiences (see von Lindern et al., 2016), with similar themes found by Hartwig and Mohamed (2020) and End Furniture Poverty (2021). Furniture also created functional spaces that participants were proud to share with family and friends, increasing their sociability.

In addition, our findings draw attention to the potential criminological implications of place attachment through the suggested role played by furniture on influencing parental guardianship and collective efficacy. When they lived in an un‐ or under‐furnished house, participants who were parents expressed that their children were less likely to spend time at home and were more likely to spend time unsupervised in the neighborhood. Youth who do not receive consistent parental guardianship are more likely to engage in risk‐taking or deviant behaviors, such as the initiation and use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs (Guo et al., 2002), early engagement in risky sexual behaviors (Longmore et al., 2001), and gang involvement (Hill et al., 1999; McDaniel, 2012). They are also more vulnerable to violent victimization (Ahlin & Lobo Antunes, 2017; Schreck & Fisher, 2004; Schreck et al., 2002; Tillyer et al., 2011; Wilcox et al., 2009). For these reasons, efforts to increase guardianship by creating a home environment where both parents and their children want to spend their time hold great value. Furnishing an otherwise un‐ or under‐furnished home is but one low‐cost and simple method of cultivating such an environment.

By reinforcing social isolation, living in an un‐ or under‐furnished house may reduce opportunities for the development of collective efficacy. It is well‐established that neighborhoods low in collective efficacy are more vulnerable to crime and disorder, defined as physical and social aspects of an environment that symbolize neighborhood decline (Burchfield & Silver, 2013; Maxwell et al., 2018; Mazerolle et al., 2010; Morenoff et al., 2001; Sampson & Raudenbush, 1999; Sampson et al., 1997; Schreck et al., 2009). In light of the potential negative impacts of social isolation, efforts to create a home environment that is functional while also inspiring pride may help remove barriers that impede residents from engaging in social interactions, in turn creating more opportunities for collective efficacy to develop and neighborhoods that are more resilient to crime and disorder. To this point, participants were more likely to invite individuals, including neighbors, over to their homes after they had received furniture, remarking that furniture helped create a comfortable environment that they were proud to share with others. While residential stability also helps promote collective efficacy (Sampson et al., 1997), we found no evidence to suggest that the receipt of furniture plays a role in this relationship. Specifically, the receipt of furniture did not influence recipients' decisions to stay or leave their homes, a decision that stands to affect the development of collective efficacy. Rather, neighborhood conditions (high crime rates and poor access to high‐quality service) rose to the forefront, a finding supported by Warnes et al. (2013).

Our study also highlights the role of furniture in enhancing participants' mental, physical, and social health. Research has found that stressful life events experienced by those who are homeless are related to the etiology and maintenance of mental disorders (Cutuli et al., 2017; Deck & Platt, 2015; Low et al., 2012; Zugazaga, 2004). For this reason, the benefits of living in a fully furnished house are especially important for those transitioning from homelessness into permanent housing. Before receiving furniture, participants were reluctant to socialize with others due to the lack of functionality of their homes, a source of shame. The receipt of furniture made it feasible for participants to host friends and family. Insofar as research has identified (positive) social interactions to enhance mental wellbeing, the receipt of furniture may serve as a preventative measure (Saxbe & Repetti, 2010).

Furniture was also instrumental in creating a restorative home environment in which participants could begin to address health issues that emerged while they were living without permanent housing and/or were exacerbated by this experience. Perhaps unsurprisingly, beds emerged as the most impactful type of furniture. Beds allowed participants to achieve restful sleep and experience its restorative mental and physical benefits. The connection between insufficient sleep and poor mental and physical health is well‐established in adult samples, with women especially susceptible to its adverse effects (Darnall & Suarez, 2009; Suarez, 2008). For example, research has found women who experienced insufficient sleep to be at greater risk of psychological distress, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes as compared to men (Darnall & Suarez, 2009; Suarez, 2008). Although stress and physical discomfort (e.g., aches and pains from sleeping on a hard surface) were the only symptoms participants attributed to insufficient sleep, this body of research suggests that our majority female sample may have been affected in other ways by insufficient sleep. For participants' children, insufficient sleep was linked to poor school performance. Research has found insufficient sleep to be linked to a host of other negative outcomes for youth, including decreased physical activity, weight gain, as well as depression, suicidal ideation, and risk‐taking behaviors (Lytle et al., 2011; O'Brien & Mindell, 2005; Wheaton et al., 2018).

Lastly, our study suggests that receiving furniture from the FBSM at little to no cost allowed participants to focus their efforts on attaining other goals. As found in earlier research based in the United Kingdom (Pawson et al., 2006; Richards, 2007; Shelter Scotland, 2010), we identified connections between the receipt of furniture, enhanced financial security, and educational attainment, the benefits of which are self‐evident. Over furniture, secure housing played the lead role in the attainment and pursuit of employment. Not captured by our interviews, furniture may have had an indirect effect on employment through its ability to provide an environment that facilitates mental, physical, and social restoration. Research has shown that such environments have the potential to increase task performance and job satisfaction (e.g., Berto, 2005; Korpela et al., 2015; Nejati et al., 2016). In light of these findings, a fully furnished home may help participants retain employment and secure its long‐term benefits.

Our study has three key limitations that future research should address to help further develop this under‐studied area of research. First, our findings suggest that (the presence or absence of) furniture influences the formation of place attachments among the recently housed. That being said, our cross‐sectional study does not permit us to identify the impact of furniture on place attachment in combination with or apart from the length of association, which research suggests positively contributes to place attachments (Bailey et al., 2012; Moore & Graefe, 1994; Vorkinn & Riese, 2001). Future studies should look longitudinally at recently housed individuals who have received furniture. Such an analysis would also be better‐suited for studying the connection between place attachment and residential stability.

Second, we recommend that future studies identify participants from a much broader cross‐section of the organizations that provide permanent housing to individuals and families in need. Our study only interviewed clients referred to the FBSM from the CHN. For this reason, the generalization of our findings should be done so with caution. We believe our study can be easily replicated in other communities, which would only serve to expand our understanding of an under‐studied basic need.

Third, future research should explore in greater depth the theoretical domains and related subcategories we have identified here. As our study is among the first of its kind, its exploratory approach was an appropriate first step toward considering the impact of furniture on those who have recently transitioned from homelessness into permanent housing. Moving forward, however, we recommend a deeper exploration with parents on how living in an un‐ or under‐furnished home influenced their children based on the compelling, but limited, testimony from our interviews.

Despite these limitations, our study has three key policy implications. First, our study strongly supports the amendment of the Arizona Self‐Sufficiency Matrix to include furniture. This amendment could be achieved through either the creation of a new domain or the expansion of existing ones. HUD's CoC program for homeless individuals and families would also be affected, as it draws from the Arizona Self‐Sufficiency Matrix. Second, our study underscores the importance of tracking clients as they receive support services in an effort to better understand their impacts and further program development. Third, the global COVID‐19 pandemic has disproportionately affected minority, economically‐depressed communities. Individuals living without permanent housing are among the most susceptible to contracting the potentially deadly virus (Baggett et al., 2020). In addition to its physical health consequences, the pandemic has contributed to poor mental and social health, and economic hardship (Lima et al., 2020). Organizations that aid unhoused individuals in securing permanent housing are therefore of special importance during these unprecedented times, as well as those that provide furniture at little to no cost (Dzigbede et al., 2020). The restorative benefits offered by a fully furnished home and the financial savings accrued from such services may help buffer the adverse effects of the pandemic on individuals and families.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/jcop.22865

Nubani, L. , De Biasi, A. , Ruemenapp, M. A. , Tams, L. D. , & Boyle, R. (2022). The impact of living in an un‐ or under‐furnished house on individuals who transitioned from homelessness. Journal of Community Psychology, 50, 3681–3699. 10.1002/jcop.22865

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Ahlin, E. M. , & Lobo Antunes, M. J. (2017). Levels of guardianship in protecting youth against exposure to violence in the community. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 15(1), 62–83. 10.1177/1541204015590000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, A. , Batty, E. , Eadson, W. , Hickman, P. , & Quinn, G. (2016). Assessment of the need for furniture provision for new NIHE tenants. CRESR, Sheffield Hallam University.

- Baggett, T. P. , Keyes, H. , Sporn, N. , & Gaeta, J. M. (2020). Prevalence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(21), 2191–2192. 10.1001/jama.2020.6887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, N. , Kearns, A. , & Livingston, M. (2012). Place attachment in deprived neighborhoods: The impacts of population turnover and social mix. Housing Studies, 27(2), 208–231. 10.1080/02673037.2012.632620 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E. , Lester, L. H. , Bentley, R. , & Beer, A. (2016). Poor housing quality: Prevalence and health effects. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 44(4), 219–232. 10.1080/10852352.2016.1197714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berto, R. (2005). Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25(3), 249–259. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boggess, L. N. , & Hipp, J. R. (2010). Violent crime, residential instability, and mobility: Does the relationship differ in minority neighborhoods? Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 26(3), 351–370. 10.1007/s10940-010-9093-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burchfield, K. B. , & Silver, E. (2013). Collective efficacy and crime in Los Angeles neighborhoods: Implications for the Latino paradox. Sociological Inquiry, 83(1), 154–176. 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2012.00429.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane, D. , Fitzpatrick, S. , & Treglia, D. (2020). Contrasting research traditions in the UK and US. In Teixeira L., & Cartwright J. (Eds.), Using evidence to end homelessness (pp. 99–124). Bristol University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Culhane, D. , Gross, K. , Parker, W. , Poppe, B. , & Sykes, E. (2008). Accountability, cost‐effectiveness, and program performance: Progress since 1998 Philadelphia. National Symposium on Homelessness Research. http://repository.upenn.edu/spp_papers/114 [Google Scholar]

- Culhane, D. , Metraux, S. , & Hadley, T. (2002). Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless persons with severe mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate, 13(1), 107–163. 10.1080/10511482.2002.9521437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culhane, D. P. , & Byrne, T. (2010). Ending chronic homelessness: Cost‐effective opportunities for interagency collaboration. Penn School of Social Policy and Practice Working Paper. https://repository.upenn.edu/spp_papers/143

- Cutuli, J. J. , Ahumada, S. M. , Herbers, J. E. , Lafavor, T. L. , Masten, A. S. , & Oberg, C. N. (2017). Adversity and children experiencing family homelessness: Implications for health. Journal of Children and Poverty, 23(1), 41–55. 10.1080/10796126.2016.1198753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnall, B. D. , & Suarez, E. C. (2009). Sex and gender in psychoneuroimmunology research: Past, present and future. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23(5), 595–604. 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deck, S. M. , & Platt, P. A. (2015). Homelessness is traumatic: Abuse, victimization, and trauma histories of homeless men. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 24(9), 1022–1043. 10.1080/10926771.2015.1074134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dzigbede, K. D. , Gehl, S. B. , & Willoughby, K. (2020). Disaster resiliency of U.S. local governments: Insights to Strengthen local response and recovery from the COVID‐19 pandemic. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 634–643. 10.1111/puar.13249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- End Furniture Poverty . (2021). Social return on investment of essential furniture provision. https://endfurniturepoverty.org/research/social-return-on-investment-of-furnitureprovision/

- Evans, G. W. , Wells, N. M. , & Moch, A. (2003). Housing and mental health: A review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. Journal of Social Issues, 59(3), 475–500. 10.1111/1540-4560.00074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, S. , & Christian, J. (2006). Comparing homelessness research in the US and Britain: What lessons can be learned? European Journal of Housing Policy, 6(3), 313–333. 10.1080/14616710600973151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. , & Lacombe, C. (2006). Housing quality and children's socioemotional health. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 21(2), 177–189. 10.1007/s10901-006-9041-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis. Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. , Hill, K. G. , Hawkins, J. D. , Catalano, R. F. , & Abbott, R. D. (2002). A developmental analysis of sociodemographic, family, and peer effects on adolescent illicit drug initiation. Journal of American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(7), 838–845. 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. B. , Werner, C. M. , Brown, B. B. , & Ingebritsen, D. (1995). Relocation and privacy regulation: A cross‐cultural analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(4), 311–320. 10.1006/jevp.1995.0027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, K. A. , & Mohamed, F. (2020). From housing instability to a home: The effects of furniture and household goods on well‐being. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 31(4), 1656–1668. 10.1353/hpu.2020.0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, K. G. , Howell, J. C. , Hawkins, J. D. , & Battin‐Pearson, S. R. (1999). Childhood risk factors for adolescent gang membership: Results from the Seattle Social Development Project. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 36(3), 300–322. 10.1177/0022427899036003003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, J. , & Sparks, P. (2008). Engaging with the natural environment: The role of affective connection and identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(2), 109–120. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HUD Exchange . (2022). Continuum of Care (CoC) Program. https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/coc/

- Joye, Y. , & van den Berg, A. (2018). Restorative environments: An introduction. In Steg, L. & de Groot, J. (Eds.), Environmental psychology (pp. 65–75). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 10.1002/9781119241072.ch7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenway, P. , & Palmer, G. (2003). How many, how much? Single homelessness and the question of numbers and cost. Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K. , De Bloom, J. , & Kinnunen, U. (2015). From restorative environments to restoration in work. Intelligent Buildings International, 7(4), 215–223. 10.1080/17508975.2014.959461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzel, A. J. (1992). Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In Crabtree, B. F. & Miller, W. L. (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (3, pp. 31–44). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, N. N. R. , de Souza, R. I. , Feitosa, P. W. G. , Moreira, J. L. , de, S. , da Silva, C. G. L. , & Neto, M. L. R. (2020). People experiencing homelessness: Their potential exposure to COVID‐19. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112945. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. , Wu, Y. , Xiao, Y. , Fu, W. , Zhuo, Z. , van den Bosch, C. C. K. , Huang, Q. , & Lan, S. (2020). More meaningful, more restorative? Linking local landscape characteristics and place attachment to restorative perceptions of urban park visitors. Landscape and Urban Planning, 197, 103763. 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore, M. A. , Manning, W. D. , & Giordano, P. C. (2001). Preadolescent parenting strategies and teens' dating and sexual initiation: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 322–335. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00322.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low, N. C. , Dugas, E. , O'Loughlin, E. , Rodriguez, D. , Contreras, G. , Chaiton, M. , & O'Loughlin, J. (2012). Common stressful life events and difficulties are associated with mental health symptoms and substance use in young adolescents. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), 116. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, L. A. , Pasch, K. E. , & Farbakhsh, K. (2011). The relationship between sleep and weight in a sample of adolescents. Obesity, 19(2), 324–331. 10.1038/oby.2010.242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L. C. (2005). For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25(1), 67–86. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. 10.1037/h0054346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, C. D. , Garner, J. H. , & Skogan, W. G. (2018). Collective efficacy and violence in chicago neighborhoods: A reproduction. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 3(3), 245–265. 10.1177/1043986218769988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazerolle, L. , Wickes, R. , & McBroom, J. (2010). Community variations in violence: The role of social ties and collective efficacy in comparative context. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(1), 3–30. 10.1177/0022427809348898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, D. D. (2012). Risk and protective factors associated with gang affiliation among high‐risk youth: A public health approach. Injury Prevention, 18(4), 253–258. 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesch, G. S. , & Manor, O. (1998). Social ties, environmental perception, and local attachment. Environment and Behavior, 30(4), 504–519. 10.1177/001391659803000405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R. , & Graefe, A. (1994). Attachments to recreation settings: The case of rail‐trail users. Leisure Sciences, 16(1), 17–31. 10.1080/01490409409513214 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff, J. D. , Sampson, R. J. , & Raudenbush, S. W. (2001). Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology, 39(3), 517–560. 10.1111/J.1745-9125.2001.TB00932.X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. M. (1994). Designing funded qualitative research. In Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 220–235). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness . (2017). Ending chronic homelessness saves taxpayers money. https://endhomelessness.org/resource/ending-chronic-homelessness-saves-taxpayers-money-2/

- Nejati, A. , Shepley, M. , Rodiek, S. , Lee, C. , & Varni, J. (2016). Restorative design features for hospital staff break areas: A multi‐method study. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 9(2), 16–35. 10.1177/1937586715592632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, E. M. , & Mindell, J. A. (2005). Sleep and risk‐taking behavior in adolescents. Behavior Sleep Medicine, 3(3), 113–133. 10.1207/s15402010bsm0303_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, H. , Donohoe, T. , Munro, M. , Netto, G. , & Wager, F. (2006). Investigating tenancy sustainment in glasgow. Report to Glasgow Housing Association and Glasgow City Council, April 2006.

- Pawson, H. , & Monroe, M. (2010). Explaining Tenancy sustainment rates in british social rented housing: The roles of management, vulnerability and choice. Urban Studies, 47(1), 145–168. 10.1177/0042098009346869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pleace, N. (2015). At what cost? An estimation of the financial costs of single homelessness in the UK. Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Proshansky, H. M. (1978). The city and self‐identity. Environment and Behavior, 10(2), 147–169. 10.1177/0013916578102002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, E. , & Korpela, K. M. (2016). Memory and place attachment as predictors of imagined restorative perceptions of favourite places. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 120–130. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, E. , & Korpela, K. M. (2018). Time and self‐related memories predict restorative perceptions of favorite places via place identity. Environment and Behavior, 50(6), 690–720. 10.1177/0013916517712002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and Placelessness. Pion. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, A. (2007). Yorkshire housing group fresh start scheme: social return on investment analysis. Liverpool John Moore's University. [Google Scholar]

- Riina, E. M. , Lippert, A. , & Brooks‐Gunn, J. (2016). Residential instability, family support, and parent–child relationships among ethnically diverse urban families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(4), 855–870. 10.1111/jomf.12317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R. J. (2006). Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In Cullen, F. T. , Wright, J. P. & Blevins, K. R. (Eds.), Taking stock: The status of criminological theory (15, pp. 149–167). Advances in Criminological Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R. J. , & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 603–651. 10.1086/210356 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R. J. , Raudenbush, S. W. , & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924. 10.1126/science.277.5328.918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxbe, D. E. , & Repetti, R. (2010). No place like home: Home tours correlate with daily patterns of mood and cortisol. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(1), 71–81. 10.1177/0146167209352864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L. , & Gifford, R. (2010). Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), 1–10. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck, C. J. , & Fisher, B. (2004). Specifying the influence of family and peers on violent victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(9), 1021–1041. 10.1177/0886260504268002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck, C. J. , McGloin, J. M. , & Kirk, D. S. (2009). On the origins of the violent neighborhood: A study of the nature and predictors of crime‐type differentiation across Chicago neighborhoods. Justice Quarterly, 26(4), 7710794. 10.1080/07418820902763079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck, C. J. , Wright, R. A. , & Miller, J. M. (2002). A study of individual and situational antecedents of violent victimization. Justice Quarterly, 19(1), 159–180. 10.1080/07418820200095201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelter Scotland . (2010). Furniture for the homeless: A house without furniture is not a home. Shelter Scotland and Community Recycling Network for Scotland. http://scotland.shelter.org.uk/data/assets/pdf_file/0009/286281/Furniture_for_the_homeless_FINAL_report.pdf

- Shumaker, S. A. , & Taylor, R. B. (1983). Toward a clarification of people‐place relationships: A model of attachment to place. In Feimer, N. R. & Geller, E. S. (Eds.), Environmental Psychology: Directions and Perspectives. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Simiriglia, C. (2019, April 5). Don't underestimate the importance of furniture. Generosity. https://generocity.org/philly/2019/04/05/dont-underestimate-the-importance-of-furniture

- Stokols, D. , & Shumaker, S. A. (1981). People in places: A transactional view of settings. In Harvey, J. (Ed.), Cognition, social behavior, and the environment (pp. 441–488). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez, E. C. (2008). Self‐reported symptoms of sleep disturbance and inflammation, coagulation, insulin resistance and psychosocial distress: Evidence for gender disparity. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 22(6), 960–968. 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. C. , & Townsend, A. R. (1976). The local ‘sense of place’ as evidenced in North‐East England. Urban Studies, 13(2), 133–146. 10.1080/00420987620080281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tillyer, M. , Tillyer, R. , Ventura Miller, H. , & Pangrac, R. (2011). Reexamining the correlates of adolescent violent victimization: The importance of exposure, guardianship, and target characteristics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(14), 2908–2928. 10.1177/0886260510390958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J. , Mares, A. S. , & Rosenheck, R. A. (2012). Housing satisfaction among chronically homeless adults: Identification of its major domains, changes over time, and relation to subjective well‐being and functional outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal, 48(3), 255–263. 10.1007/s10597-011-9385-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twigger‐Ross, C. , & Uzzell, D. L. (1996). Place and identity processes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 16(3), 205–220. 10.1006/jevp.1996.0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R. S. (1983). Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Altman I., & Wohlwill J. F. (Eds.), Human behavior and environment (advances in theory and research) (Vol. 6, pp. 85–125). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4613-3539-9_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von Lindern, E. , Lymeus, F. , & Hartig, T. (2016). The restorative environment: A complementary concept for salutogenesis studies. In Mittelmark M. B., Sagy S., & Eriksson M. (Eds.), The handbook of Salutogenesis (pp. 181–195). Springer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorkinn, M. , & Riese, H. (2001). Environmental concern in a local context: The significance of place attachment. Environment and Behavior, 33(2), 249–263. 10.1177/00139160121972972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warnes, A. , Crane, M. , & Coward, S. (2013). Factors that influence the outcomes of single homeless people's rehousing. Housing Studies, 28(5), 782–798. 10.1080/02673037.2013.760032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, A. G. , Jones, S. E. , Cooper, A. C. , & Croft, J. B. (2018). Short sleep duration among middle school and high school students—United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(3), 85–90. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6703a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, P. , Tillyer, M. S. , & Fisher, B. S. (2009). Gendered opportunity? School‐based adolescent victimization. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 46(2), 245–269. 10.1177/0022427808330875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. R. , Patterson, M. E. , Roggenbuck, J. W. , & Watson, A. E. (1992). Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leisure Sciences, 14(1), 29–46. 10.1080/01490409209513155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zugazaga, C. (2004). Stressful life event experiences of homeless adults: A comparison of single men, single women, and women with children. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(6), 643–654. 10.1002/jcop.20025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.