Abstract

Hispanic emerging adults are often exposed to ethnic discrimination, yet little is known about coping resources that may mitigate the effects of ethnic discrimination on psychological stress in this rapidly growing population. As such, this study aims to examine (1) the associations of ethnic discrimination, distress tolerance, and optimism with psychological stress and (2) the moderating effects of distress tolerance and optimism on the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress. Data were drawn from a cross-sectional study of 200 Hispanic adults ages 18–25, recruited from two urban counties in Arizona and Florida. Hierarchical multiple regression and moderation analyses were utilized to examine these associations and moderated effects. Findings indicated that higher optimism was associated with lower psychological stress. Conversely, higher ethnic discrimination was associated with higher psychological stress. Moderation analyses indicated that both distress tolerance and optimism moderated the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress. These study findings add to the limited literature on ethnic discrimination among Hispanic emerging adults and suggest that distress tolerance may be a key intrapersonal factor that can protect Hispanic emerging adults against the psychological stress often resulting from ethnic discrimination.

Keywords: Cultural stressors, Racism, Coping, Stress, Latino

Psychological stress manifests when an individual perceives that the environment or a situation is beyond his or her coping resources (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007; Folkman & Lazarus, 1984). Studies have indicated that exposure to chronic psychological stress is harmful, as it has been identified as a significant determinant of various chronic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, and depression (Cohen et al., 2007; World Health Organization, 2010).

Psychological stress is particularly salient in the years of emerging adulthood (ages 18–25), a distinct period of life characterized by the development of personal identity, greater autonomy, and challenging developmental tasks (Arnett, Žukauskienė, & Sugimura, 2014). These challenging tasks include finding a long-term romantic partner, job, educational pursuits, and taking on new social roles (Shanahan, 2000). The unstable nature of this period can make life difficult and stressful (Arnett, 2000; Arnett et al., 2014). Stressors may be compounded among Hispanic emerging adults, one of the largest and most rapidly growing portions of the U.S. population, because they often report exposure to chronic sociocultural stressors, which may place them at greater risk for experiencing psychological stress (Cano, Schwartz, et al., 2020; Noe-Bustamante & Flores, 2019). One such sociocultural stressor is ethnic discrimination, defined as biased or unfair treatment based on one’s ethnicity (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Research indicates that, compared to older Hispanics, Hispanic emerging adults are more likely to report ethnic discrimination (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/National Public Radio, 2017). Taking all of this into consideration, it is critical to advance our understanding of the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress and to identify malleable factors that can potentially offset this deleterious association. Identifying modifiable factors may serve to inform the creation and modification of evidence-based prevention programs (MacKinnon & Luecken, 2008). Accordingly, the current study was designed to (1) examine the associations of ethnic discrimination, distress tolerance, and optimism with psychological stress among Hispanic emerging adults; and (2) examine the extent to which distress tolerance and optimism may operate as moderators.

Our study is guided by an integrative framework that draws from two conceptual models—the Biopsychosocial Effects of Perceived Racism model and the Coping with Racism model (Clark et al., 1999; Brondolo, Brady Ver Halen, Pencille, Beatty & Contrada, 2009). The Biopsychosocial Effects of Perceived Racism model proposes that higher levels of ethnic discrimination lead to higher levels of stress. In support of the Biopsychosocial Effects of Perceived Racism model, multiple studies (Carter, 2007; May., Cochran, & Barnes, 2007) have found that higher levels of ethnic discrimination are associated with higher psychological distress, characterized by symptoms of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, the Coping with Racism Model posits that coping resources can act as moderators that buffer the adverse effects of ethnic discrimination. In the present study, we focus on intrapersonal factors (i.e., distress tolerance, optimism) that are hypothesized to function as coping resources that buffer the effect of adversity and stressors (e.g., ethnic discrimination; Gallo et al., 2009; Steele, Spencer, & Lynch, 1993). Prior research by Park and colleagues utilized the Coping with Racism model to explore intrapersonal factors as moderators of ethnic discrimination and adjustment link among Hispanic adolescents (Park, Wang, Williams & Alegría, 2017).

Distress tolerance

Distress tolerance refers to an individual’s capacity to encounter and endure challenging and distressful events and mental states (Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein et al. 2010). Acknowledging the potential function of distress tolerance as an interpersonal coping resource, a comprehensive review (Leyro et al., 2010) recommends examining distress tolerance as a moderator to determine whether it acts as a buffer between stressful exposures and various outcomes. Since then, multiple studies have examined distress tolerance as an intrapersonal coping resource and found it to be a significant moderator of various associations (Ali, Ryan, Beck, & Daughters, 2013; Bartlett et al., 2018; Kyron, Hooke, Bryan, & Page, 2021; Zegel, Rogers, Vujanovic, & Zvolensky, 2021). Furthermore, a review of theories and empirical studies (Leyro et al. 2010; Wegner, 1994) on distress tolerance suggests that individuals with low distress tolerance were less capable of handling difficult circumstances. The review also indicated that these individuals are more likely to utilize maladaptive coping strategies experiencing unpleasant emotional situations, in turn, enhancing negative emotional states. Studies have also found that low distress tolerance is associated with various adverse psychological outcomes, including depressive symptoms, anxiety, and substance use disorders (Allan, Macatee, Norr & Schmidt, 2014; Keough, Riccardi, Timpano, Mitchell & Schmidt, 2010; Richards, Daughters, Bornovalova, Brown & Lejuez, 2011). Conversely, higher distress tolerance has been found to be associated with successful treatment outcomes for conditions such as depressive and anxiety disorders (Banducci, Connolly, Vujanovic, Alvarez & Bonn-Miller, 2017; McHugh, Kertz, Weiss, Baskin-Sommers, Hearon & Björgvinsson, 2014; Williams, Thompson, & Andrewse, 2013). Considering the beneficial role of distress tolerance, several psychological interventions have been designed to enhance distress tolerance in response to stressful situations, and have shown favorable outcomes (Barlow et al., 2004; Orsillo & Roemer, 2005; Orsillo et al., 2003; Roemer & Orsillo, 2002; Williams, Teasdale, Segal & Soulsby, 2000).

As noted above, emerging adulthood is a transitional period of life, and these transitions can lead to higher levels of distress (Lane, 2015; Lane et al., 2017). Considering this developmental context, distress tolerance can represent a potential intrapersonal coping resource that may help emerging adults cope with sociocultural stressors. Yet, few studies have assessed the role of distress tolerance on adverse outcomes among this population. A study involving Australian emerging adults (Slabbert, Hasking, Notebaert & Boyes, 2020) found that improving distress tolerance may reduce the possibility of engaging in non-suicidal self-injury. Another study involving college students (Perez, Nicholson, Dahlen & Leuty, 2019) found a significant mediating role of distress tolerance in the association between overparenting and poor mental health. To our knowledge, no prior studies have assessed the relationship between distress tolerance and psychological stress among Hispanic emerging adults. As such, it is necessary to examine whether distress tolerance may mitigate the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress among Hispanic emerging adults.

Optimism

Optimism is defined as a general predisposition for expecting positive rather than negative events in the future (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Literature indicates that optimism can function as an intrapersonal coping resource that can offset the adverse effects of sociocultural stressors. For example, in a study involving young adults, optimism was found to moderate the relationship between race-related stress and anxiety symptoms (Lee et al., 2015). Another study involving young African American mothers found optimism to buffer the effects of perceived ethnic discrimination, resulting in lower depressive symptoms (Odom & Vernon-Feagans, 2010). Individuals with higher optimism often confront life’s challenges with a positive attitude, resulting in higher determination and higher success in achieving goals (Avvenuti et al., 2016). Individuals with higher levels of optimism also report better health, characterized by higher levels of antioxidants, lower levels of inflammation markers, and more favorable lipid profiles (Carver & Scheier, 2014; Segerstrom, 2005). Furthermore, a review (Smith & MacKenzie, 2006) found optimism to act as a protective factor of psychological well-being for those experiencing elevated stress. Studies have indicated that higher optimism is associated with lower depressive symptoms and anxiety disorders (Chang & Sanna, 2001; Hart et al., 2008;).

The unstable nature and challenging developmental tasks of emerging adulthood are associated with psychological stress, and optimism has been hypothesized to serve as an intrapersonal coping resource during this developmental period (Arnett, 2000; Arnett et al., 2014; Masten, Obradović, & Burt, 2006). However, only a limited number of studies have examined the effect of optimism among emerging adults. Research among French college students (Saleh, Camart, & Romo, 2017) found optimism to be inversely related to stress. Another study involving Chinese emerging adults (Li, Wang, Zhou, Ren & Gao, 2020) reported the beneficial role of optimism in the improvement of stress-related growth. To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the association between optimism and psychological stress, or the moderating effect of optimism on the relationship between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress among Hispanic emerging adults. As such, among this population, it is imperative to assess whether optimism may mitigate the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress.

The present study

Based on the review of the existing literature, the following hypotheses were proposed. Hypothesis one, higher levels of distress tolerance and optimism will be associated with lower levels of psychological stress, and by contrast, higher levels of ethnic discrimination will be associated with higher levels of psychological stress. Hypothesis two, distress tolerance and optimism will function as moderators that will weaken the adverse association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress.

Methods

Procedure and participants

The present study consisted of 200 participants from the Project on Health among Emerging Adult Latinos (Project HEAL) that was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Florida International University. Participants were recruited utilizing a quota sampling technique from Maricopa County, Arizona and Miami-Dade County, Florida. Various recruitment strategies (e.g., in-person invitations, posting flyers, targeted emails) were employed to recruit potential participants. Interested potential participants contacted the project coordinator for screening. Based on meeting the eligibility criteria, access was given to the online survey. Inclusion criteria were being ages 18–25, self-identifying as Hispanic or Latina/o, able to read English, and currently living in Maricopa County, Arizona or Miami-Dade County, Florida. The mean participant age was 21.30 (SD = 2.09), and approximately half the sample was composed of women (n = 102, 51.0%) and participants from Arizona (n = 99, 49.5%). The following Hispanic heritage groups were represented: Mexican (n = 88, 44.0%), Cuban (n = 33, 16.5%), Colombian (n = 24, 12.0%), other South American (n = 21, 10.5%), Central American (n = 20, 10.0%), and Puerto Rican (n = 9, 4.5%). Participants provided consent through an electronic informed consent form. The survey was conducted in English and took approximately 50 min to complete. Participants were compensated for their time with a $30 electronic Amazon gift card. More details on the procedures for Project HEAL are published elsewhere (Cano, Sanchez et al., 2020).

Study measures

Demographic questionnaire:

Sociodemographic variables assessed and included as covariates were: age (continuous, in years), gender, (0 = male, 1 = female), study site (0 = Florida, 1 = Arizona), partner status (0 = single, 1 = has a partner), nativity (0 = immigrant, 1 = non-immigrant), Hispanic heritage group (0 = other Hispanic heritage, 1 = Mexican heritage), student status (0 = current college student, 1 = non-college student), employment status (0 = unemployed, 1 = employed), and financial strain (1 = has more money than needed, 2 = just enough money for needs, 3 = not enough money to meet needs).

Psychological stress:

Self-reported psychological stress was measured with the four-item Perceived Stress Scale Short Form (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983; Warttig, Forshaw, South, & White, 2013). A sample item from this measure is, “How often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?” Participants responded to items in this measure using a five-point Likert-type scale (0 = never, 4 = very often). Higher sum scores are indicative of higher psychological stress. In our sample, Cronbach’s reliability coefficient for psychological stress was α = 0.70. This is a measure of psychological stress that has been validated among Hispanics (Vallejo, Vallejo-Slocker, Fernández-Abascal & Mañanes, 2018).

Distress tolerance:

Self-reported distress tolerance was measured using the three-item tolerance subscale from Distress Tolerance Scale (Simons & Gaher, 2005). A sample item from this measure is, “Feeling distressed or upset is unbearable to me” Participants responded to items from this measure using a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). All items were reverse-scored so that higher mean scores would be indicative of higher distress tolerance. Cronbach’s reliability coefficient for this measure was α = 0.83 in our sample. This measure has been validated among Hispanics (Sandín, Simons, Valiente, Simons, & Chorot, 2017).

Optimism:

The Life Orientation Test-Revised was utilized to measure dispositional optimism. This test includes two factors, one with positive phrasing and one with negative phrasing that is reverse-scored (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). The present study only used the factor with the three negatively phrased items, as this factor is associated with the highest factor loadings and internal consistency (Scheier et al., 1994; Segerstrom, Evans, & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2011). A sample item from this measure is, “I rarely count on good things happening to me.” Participants responded to items in this measure using a five-point scale (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). All the items were reversed scored so that higher sum scores would be indicative of higher optimism. In the study sample, Cronbach’s reliability coefficient for this measure was α = 0.87. This measure has been validated among Hispanics (Cano-García et al., 2015).

Ethnic discrimination:

The nine-item ethnic discrimination subscale from the Scale of Ethnic Experience was utilized to measure perceived ethnic discrimination (Malcarne, Chavira, Fernandez & Liu, 2006). A sample item from this measure is, “In my life, I have experienced prejudice because of my ethnicity.” Participants responded to items in the measure using a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Higher mean scores are indicative of higher perceived ethnic discrimination. In the study’s sample, Cronbach’s reliability coefficient for this measure was α = 0.90.

Statistical analysis plan

SPSS Version 25 was utilized to conduct all analyses. There were no missing data for the covariates, and missing data for the multi-item scales did not exceed 2%. Scores were not artificially lowered; the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm was utilized at the item level, prior to computing subscale scores. Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were computed for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions were generated for categorical variables. Correlations between continuous study variables were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficients. Multicollinearity was assessed using two diagnostic indicators, tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF). It is recommended that the tolerance value be higher than.10 and the VIF value be lower than 10 (Cohen, Cohen, West & Aiken, 2003).

A hierarchical multiple regression (HMR) model was used to estimate the main effects of the predictor variables on psychological stress. Predictor variables were entered into the HMR model in a specified order so that each block of predictors contributed explanatory variance to the outcome variable (i.e., psychological stress) after controlling for the variance explained by the previous block of variables (Cohen et al., 2003). Predictor variables were grouped and entered into the HMR model in the following order: (1) demographic variables were entered in the first block, (2) distress tolerance and optimism were entered in the second block, and (3) ethnic discrimination was entered in the third and final block to determine the extent to which it uniquely predicted psychological stress above and beyond the other predictors.

Using PROCESS v3.2 for SPSS (Hayes, 2017), moderation analyses were conducted to examine the extent to which potential moderating variables may have changed the direction and/or strength of the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress. PROCESS tests moderation by (1) performing a multiple regression to replicate the variance explained by all the predictor variables included in the HMR model, (2) estimating interaction terms between the focal predictor (e.g., ethnic discrimination) and the moderating variable (e.g., distress tolerance), and (3) estimating conditional effects in relation to psychological stress. To estimate standardized regression coefficients in PROCESS, variables were standardized. The moderation analyses controlled for all the associations in the HMR model.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Frequencies, proportions, means, and standard deviations for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Correlations for all study variables are presented in Table 2. Assumptions of multicollinearity were met because all tolerance values were higher than.10 and all VIF values were lower than 10.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study variables (n = 200).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 102 (51.0) |

| Male | 98 (49.0) |

| Study Site | |

| Arizona | 99 (49.5) |

| Florida | 101 (50.5) |

| Nativity | |

| Immigrant | 60 (30.0) |

| Non-immigrant | 140 (70.0) |

| Hispanic Heritage | |

| Mexican | 88 (44.0) |

| Other Hispanic Heritage | 112 (56.0) |

| Partner Status | |

| Single | 142 (71.0) |

| Has Partner | 58 (29.0) |

| Student Status | |

| Current College Student | 139 (69.5) |

| Non-College Student | 61 (30.5) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 157 (78.5) |

| Unemployed | 43 (21.5) |

| M (SD) | |

| Age | 21.30 (2.09) |

| Financial Strain | 2.30 (0.60) |

| Distress Tolerance | 2.89 (1.08) |

| Optimism | 7.20 (2.79) |

| Ethnic Discrimination | 3.31 (0.88) |

| Psychological Stress | 6.83 (2.96) |

Table 2.

Univariate correlations for study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | – | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −.05 | – | |||||||||||

| Study Site | .17* | .05 | – | ||||||||||

| Partner Status | .24** | .10 | .07 | – | |||||||||

| Nativity | .08 | .14* | .34** | −.01 | – | ||||||||

| Hispanic Heritage | .23** | .02 | .86** | .06 | .32** | – | |||||||

| Student Status | .30** | −.00 | .02 | .01 | −0.11 | .00 | – | ||||||

| Employment Status | .27** | .05 | .40** | .09 | .16* | .37** | .24** | – | |||||

| Financial Strain | −.02 | .09 | .07 | .03 | .02 | .06 | −0.19** | .02 | – | ||||

| Distress Tolerance | .05 | −0.14 | .08 | .09 | −0.14 | .10 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.02 | – | |||

| Optimism | .03 | −0.05 | −0.22** | .01 | −0.21** | −.18** | .16* | .02 | −0.22** | .08 | – | ||

| Ethnic Discrimination | .10 | .26** | .43** | .15* | .30** | .43** | −.21** | .12 | .16* | −0.08 | −0.36** | – | |

| Psychological Stress | −.06 | .20** | .13 | −0.09 | .22** | .10 | −0.26** | −.15* | .22** | −.11 | −0.63** | .41** | – |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Hierarchical multiple regression

Table 3 presents all regression coefficients from the HMR model. Results indicate that 50.7% of the variance in psychological stress was explained by all predictor variables entered in the HMR model (Model 3). The first predictor block included demographic variables and explained 20.8% of the variance in psychological stress, R2 = .208, F(9, 190) = 5.54, p < .001. The second block added distress tolerance and optimism, which explained 27.9% of the variance in psychological stress ΔR2 = .279, F(2, 188) = 51.02, p < .001. The third and final block added ethnic discrimination, which explained 2.0% of the variance in psychological stress, ΔR2 = .020, F(1, 187) = 7.75, p = .006. Our first hypothesis was that higher levels of distress tolerance and optimism would be associated with lower levels of psychological stress, and by contrast, higher levels of ethnic discrimination would be associated with higher levels of psychological stress. Standardized regression coefficients from the final regression model indicate that being unemployed (β = −0.14, p = .02) and higher optimism (β = −0.52, p < .001) were associated with lower psychological stress. Conversely, being male (β = 0.12, p = .03) and perceiving greater ethnic discrimination (β = 0.18, p = .006) were associated with higher psychological stress. The association between distress tolerance and psychological stress was not statistically significant (β = −0.04, p = .51).

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Model Predicting Psychological Stress.

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | b | SE | β | b | SE | β | |

| Block 1 | |||||||||

| Age | .07 | .10 | .05 | .09 | .08 | .06 | .07 | .08 | .05 |

| Gender | 1.01 | .39 | .17 * * | .96 | .32 | .16 * * | .73 | .32 | .12 * |

| Study Site | .91 | .76 | .15 | .24 | .62 | .04 | .11 | .61 | .02 |

| Partner Status | −0.61 | .44 | −0.09 | −0.52 | .35 | −0.08 | −0.67 | .35 | −0.10 |

| Nativity | 1.01 | .45 | .16 * | .43 | .38 | .07 | .34 | .37 | .05 |

| Hispanic Heritage | −0.15 | .75 | −0.03 | −0.06 | .61 | −0.01 | −0.34 | .61 | −0.06 |

| Student Status | −1.18 | .46 | −0.18 * * | −0.89 | .37 | −0.14 * | −0.69 | .37 | −0.11 |

| Employment Status | −1.42 | .53 | −0.20 * * | −1.07 | .44 | −0.15 * | −1.02 | .43 | −0.14 * |

| Financial Strain | .84 | .33 | .17 * * | .31 | .27 | .06 | .29 | .27 | .06 |

| Block 2 | |||||||||

| Distress Tolerance | −0.14 | .15 | −0.05 | −0.10 | .15 | −0.04 | |||

| Optimism | −0.59 | .06 | −0.56 * ** | −0.55 | .06 | −0.52 * ** | |||

| Block 3 | |||||||||

| Ethnic Discrimination | .62 | .22 | .18 * * | ||||||

Note: b = unstandardized coefficient, SE = standard error, β = standardized coefficient;

p ≤ .05,

p≤ .01,

p ≤ .001;

R2 = 20.8% for Block 1, ΔR2 change = 27.9% for Block 2, ΔR2 change = 2.0% for Block 3.

Moderation analyses

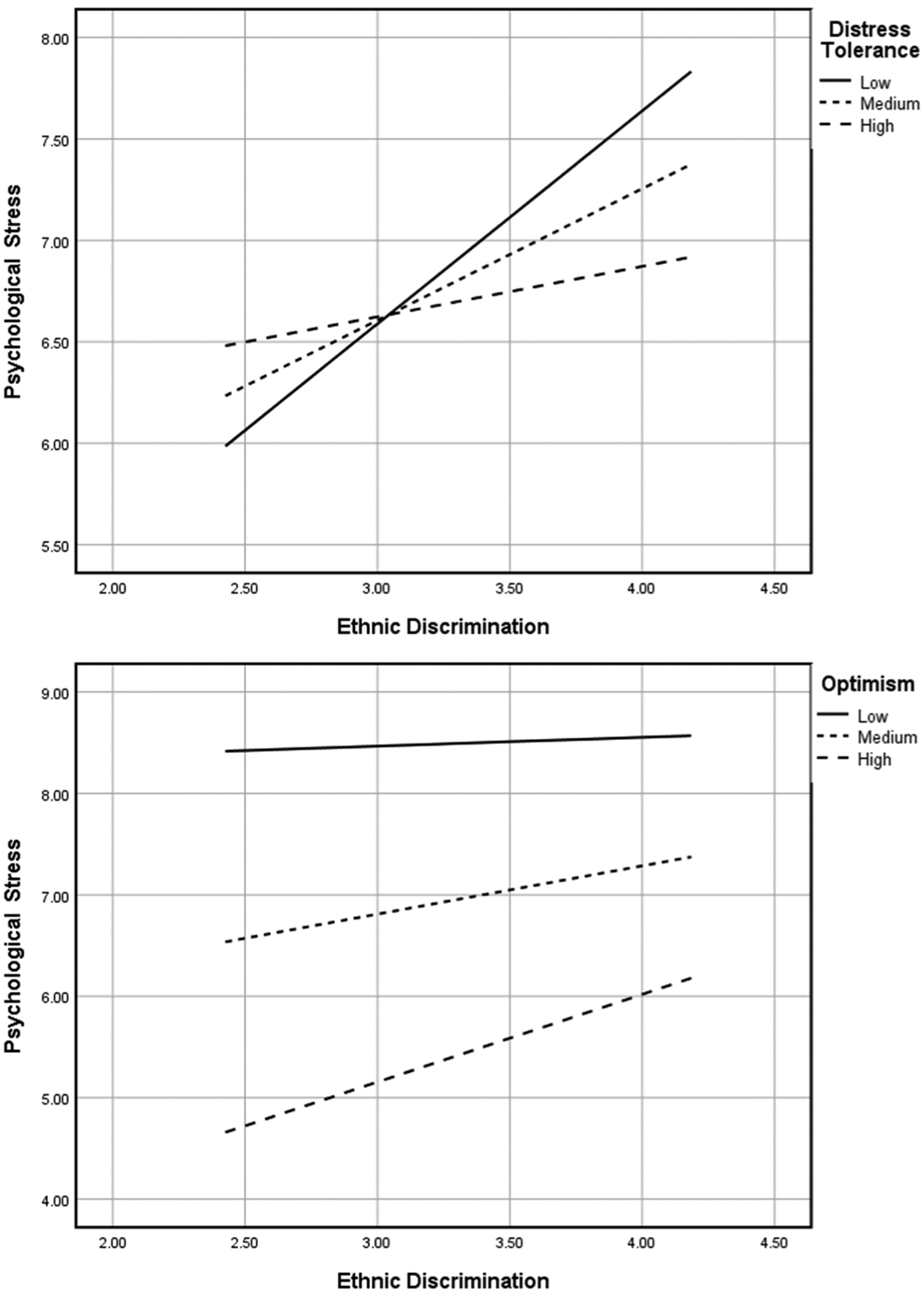

Our second hypothesis was that distress tolerance and optimism would function as moderators that will weaken the adverse association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress. The first moderation analysis indicated that distress tolerance exerted a statistically significant moderating effect on the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress (β = −0.12, p = .02). Conditional effects indicated that ethnic discrimination had the strongest association with psychological stress for those reporting low levels of distress tolerance (1 SD below the mean; β = 0.32, p < .001), and the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress was also statistically significant but weaker for those reporting average levels of distress tolerance (β = 0.18, p = .01). The conditional effect of ethnic discrimination on psychological stress was not statistically significant at high levels of distress tolerance (1 SD above the mean; β = 0.07, p = .34).

The second moderation analysis indicated that optimism also had a statistically significant moderating effect on the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress (β = 0.12, p = .03). Conditional effects showed that ethnic discrimination had the strongest association with psychological stress for those reporting high levels of optimism (1 SD above the mean; β = 0.26, p < .001), and the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress was also statistically significant but weaker for those reporting average levels of optimism (β = 0.13, p = .05). The conditional effect of ethnic discrimination on psychological stress was not statistically significant at low levels of optimism (1 SD below the mean; β = 0.04, p = .64). Both moderating effects are depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Two-way interactions with distress tolerance and optimism moderating the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress.

Discussion

The key findings of this study can be outlined as follows. Our first hypothesis was partially supported. Findings indicate that higher levels of ethnic discrimination were significantly associated with higher levels of psychological stress among Hispanic emerging adults. By contrast, higher levels of optimism were associated with lower levels of psychological stress; however, the association between distress tolerance and psychological stress was not statistically significant. Our second hypothesis was also partially supported. Findings indicate that both distress tolerance and optimism had moderating effects on the association between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress. However, the moderating effect of optimism was not in the direction we hypothesized.

Stress has substantial adverse effects on mental and physical health (Thoits, 2010). In addition to experiencing a significant amount of stress, considerable changes in social roles occur during emerging adulthood, which may have long-term health effects (Bell & Lee, 2008). Furthermore, Hispanic emerging adults face additional sociocultural stressors in addition to normative developmental stressors, putting them at higher risk of experiencing adverse psychological outcomes (Cano, Schwartz, et al., 2020). Taking all these factors into consideration, it is imperative to identify modifiable and protective factors that can help this vulnerable population with psychological stress. As expected, higher levels of ethnic discrimination were found to be significantly associated with higher levels of psychological stress in the present study. This finding can be explained through the conceptual frameworks of social determinants of health, which propose that experiencing actual or perceived ethnic discrimination, or unjust or wrong treatment, based on one’s ethnic/racial background enhances the risk of poor mental health (Clark et al., 1999; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). This conclusion has been supported by various studies involving various groups of emerging adults. For example, a study among African American emerging adults found higher levels of ethnic discrimination to be associated with higher negative emotions and lower psychological or coping resources (Joseph, Peterson, Gordon & Kamarck, 2020). Additionally, multiple studies with Hispanic and multiethnic emerging adult samples found higher levels of ethnic discrimination to be related to symptoms of depression, anxiety, lower self-esteem, and suicidal ideation (Cano et al., 2016; Cheref, Talavera, & Walker, 2019).

Findings from the present study also indicate that higher optimism was associated with lower psychological stress. This finding is in line with other studies that examined optimism and psychological stress among emerging adults. For example, a study among French college students (Saleh et al., 2017) found optimism to be negatively associated with psychological stress. Similarly, another study involving first-year college students (Mazé & Verlhiac, 2013) found an inverse relationship between optimism and stress. This finding is expected, as literature shows higher optimism to be associated with a wide range of positive factors, including life satisfaction, sense of coherence, hope, and psychological well-being (Chang & Sanna, 2001; Krok, 2015, Liu et al., 2018).

Our study did not find distress tolerance to be significantly associated with psychological stress. Perhaps because optimism is a stronger predictor of psychological stress compared to distress tolerance, the association of distress and psychological stress was not found to be statistically significant. Nonetheless, our study findings suggest that distress tolerance functioned as a moderator between the association of ethnic discrimination and psychological stress. More specifically, individuals who reported low levels of distress tolerance experienced higher levels of psychological stress in the presence of higher levels of ethnic discrimination. This finding can be explained using the stress process model (Pearlin, 1989), which consists of three elements—stressors, moderators, and resultant health outcomes. This model is concerned with the degree to which enhancing or diminishing intrapersonal, interpersonal, and social resources affect levels of stress and, in turn, mental health outcomes (Katerndahl & Parchman, 2002).

Results of the present study suggest that distress tolerance may represent a key intrapersonal factor that can help Hispanic emerging adults with psychological stress resulting from ethnic discrimination. This finding is in line with literature examining the effect of distress tolerance. For example, a longitudinal investigation involving African American college students (Le, Iwamoto, & Burke, 2020) found the beneficial effect of higher distress tolerance on the relationship between ethnic discrimination and psychological well-being. Another study (Perez et al., 2019) examining the effects of overparenting on college students’ mental health found distress tolerance to be a significant factor that may help them during the transition to college. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to examine the moderating effect of distress tolerance on the relationship between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress among Hispanic emerging adults.

Findings from our study also suggest that optimism served as a moderator in the association of ethnic discrimination with psychological stress. First, participants with high levels of optimism reported the lowest levels of psychological stress, and participants with low levels of optimism reported the highest levels of psychological stress. Nonetheless, in the presence of ethnic discrimination, the beneficial effects of optimism appeared to weaken. It is plausible that emerging adults who are highly optimistic experience exposure to ethnic discrimination as being unexpected and/or more threatening, resulting in higher psychological stress. Also, if optimism is not particularly high, Hispanic emerging adults may become overwhelmed by other stressors. Further prospective observational studies should be conducted to clarify the role of optimism in the relationship between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress. A meta-analysis (Malouff & Schutte, 2017) found that optimism can be enhanced through psychological interventions which highlight the practical role of optimism in interventions to prevent and reduce psychological stress.

Interventions have been designed to enhance distress tolerance and optimism (e.g., emotion regulation interventions, positive psychology interventions). These interventions could be applied to address experiences of ethnic discrimination. More qualitative research would be needed to develop a better idea of how to target distress tolerance and optimism effectively in the context of ethnic discrimination. Based on our findings, these two intrapersonal factors may play roles in interacting with the effects of discrimination; however, future studies will be needed to replicate our findings. We believe qualitative research methods will be needed to identify the best approaches to promote distress tolerance and optimism in the context of discrimination and stress.

Limitations

The following limitations need to be considered while interpreting the findings of the study. First, this study used self-reported measures that are subject to participant misrepresentation and measurement error. Gender was classified as male or female only, precluding an examination of gender minority or non-binary subgroups. Second, due to the cross-sectional design of the study, we cannot establish directionality or cause-effect relationships. Third, we focused on intrapersonal coping resources that may place the burden on the victim to cope with ethnic discrimination. Therefore, research on macro-level factors is needed to inform interventions that can target structural or institutional discrimination. Lastly, the study utilized a non-probability sampling technique and relatively small sample size, potentially limiting generalizability and our ability to detect subgroup variations attributable to nativity or different Hispanic heritage groups. Further, most participants were U.S.-born and current college students. It should be noted that Hispanic college students may face more discrimination because most institutions of higher education in the U.S., regardless of their ethnic composition, are rooted in Eurocentric cultural assumptions that may lead Hispanic college students to experience cultural incongruity in academic environments (Castillo, Conoley, & Brossart, 2004; Castillo et al., 2006). We mention this because enrollment of Hispanics in colleges/universities has nearly doubled in the past 20 years (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019); therefore, future studies could focus on experiences of ethnic discrimination among Hispanic emerging adults who are college students. In addition, future studies should also attempt to recruit more diverse samples that are more representative of the broader Hispanic population living in the United States.

Conclusion

The present study adds to the limited literature on modifiable factors that may aid Hispanic emerging adults to mitigate the adverse effects of ethnic discrimination. This study is one of the first to examine the relationship between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress among Hispanic emerging adults. The findings from this study advance our understanding of how enhancing optimism and decreasing ethnic discrimination may aid this population in lowering psychological stress. Furthermore, this study also highlights the roles of distress tolerance and optimism in the relationship between ethnic discrimination and psychological stress. It has been recommended that priority should be given to interventions that address institutional or structural discrimination. However, interventions that target institutional and structural discrimination are difficult to design and implement because they require a great deal of time and multiple stakeholders to initiate and sustain (Bailey et al., 2021). Thus, we believe we should also equip people with practical tools (e.g., coping resources) so that they can overcome the adverse effects of ethnic discrimination. Taken altogether, these findings may have the potential to be translated into intervention programs that can play a vital role in reducing psychological stress among Hispanic emerging adults.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [K01 AA025992, L60 AA028757], and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [U54 MD002266, U54 MD012393]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to acknowledge Carlos Estrada and Irma Beatriz Vega de Luna for their work in recruiting participants.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflicts of interest and do not have any financial disclosures to report.

References

- Ali B, Ryan JS, Beck KH, & Daughters SB (2013). Trait aggression and problematic alcohol use among college students: The moderating effect of distress tolerance. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(12), 2138–2144. 10.1111/acer.12198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan NP, Macatee RJ, Norr AM, & Schmidt NB (2014). Direct and interactive effects of distress tolerance and anxiety sensitivity on generalized anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(5), 530–540. 10.1007/s10608-014-9623-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. 10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Žukauskienė R, & Sugimura K (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1, 569–576. 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvenuti G, Baiardini I, & Giardini A (2016). Optimism’s explicative role for chronic diseases. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 295. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, & Bassett MT (2021). How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of US racial health inequities. The New England Journal of Medicine, 768–773. 10.1056/NEJMms2025396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banducci AN, Connolly KM, Vujanovic AA, Alvarez J, & Bonn-Miller MO (2017). The impact of changes in distress tolerance on PTSD symptom severity post-treatment among veterans in residential trauma treatment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 47, 99–105. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, & Choate ML (2004). Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy, 35(2), 205–230. 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80036-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett BA, Jardin C, Martin C, Tran JK, Buser S, Anestis MD, & Vujanovic AA (2018). Posttraumatic stress and suicidality among firefighters: The moderating role of distress tolerance. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(4), 483–496. 10.1007/s10608-018-9892-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S, & Lee C (2008). Transitions in emerging adulthood and stress among young Australian women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(4), 280–288. 10.1080/10705500802365482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Brady Ver Halen N, Pencille M, Beatty D, & Contrada RJ (2009). Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 64–88. 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Castro Y, de Dios MA, Schwartz SJ, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Roncancio AM, & Zamboanga BL (2016). Associations of ethnic discrimination with symptoms of anxiety and depression among Hispanic emerging adults: A moderated mediation model. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 29(6), 699–707. 10.1080/10615806.2016.1157170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Sánchez M, De La Rosa M, Rojas P, Ramírez-Ortiz D, Bursac Z, & de Dios MA (2020). Alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining the roles of bicultural self-efficacy and acculturation. Addictive Behaviors, 108, Article 106442. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Schwartz SJ, MacKinnon DP, Keum B, Prado G, Marsiglia FF, & de Dios MA (2020). Exposure to ethnic discrimination in social media and symptoms of anxiety and depression among Hispanic emerging adults: Examining the moderating role of gender. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 571–586. 10.1002/jclp.23050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano-García FJ, Sanduvete-Chaves S, Chacón-Moscoso S, Rodríguez-Franco L, García-Martínez J, Antuña-Bellerín MA, & Pérez-Gil JA (2015). Factor structure of the Spanish version of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R): Testing several models. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 15(2), 139–148. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105. 10.1177/0011000006292033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, & Scheier MF (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(6), 293–299. 10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Conoley CW, & Brossart DF (2004). Acculturation, White marginalization, and family support as predictors of perceived distress in Mexican American female college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(2), 151–157. 10.1037/0022-0167.51.2.151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Conoley CW, Choi-Pearson C, Archuleta DJ, Phoummarath MJ, & Van Landingham A (2006). University environment as a mediator of Latino ethnic identity and persistence attitudes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(2), 267–271. 10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, & Sanna LJ (2001). Optimism, pessimism, and positive and negative affectivity in middle-aged adults: A test of a cognitive-affective model of psychological adjustment. Psychology and Aging, 16(3), 524–531. 10.1037/0882-7974.16.3.524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheref S, Talavera D, & Walker RL (2019). Perceived discrimination and suicide ideation: Moderating roles of anxiety symptoms and ethnic identity among Asian American, African American, and Hispanic emerging adults. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 49(3), 665–677. 10.1111/sltb.12467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, & Williams DR (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54, 805–816. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, & Miller GE (2007). Psychological stress and disease. Journal of the American Medical Association, 298, 1685–1687. 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Lazarus RS (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping (pp. 150–153). New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, de los Monteros KE, Shivpuri S, et al. (2009). Socioeconomic status and health: What is the role of reserve capacity? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci, 18(5), 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467–8721.2009.01650.x. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01650.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart SL, Vella L, & Mohr DC (2008). Relationships among depressive symptoms, benefit-finding, optimism, and positive affect in multiple sclerosis patients after psychotherapy for depression. Health Psychology, 27(2), 230–238. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph NT, Peterson LM, Gordon H, & Kamarck TW (2020). The double burden of racial discrimination in daily-life moments: Increases in negative emotions and depletion of psychosocial resources among emerging adult African Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27, 234–244. 10.1037/cdp0000337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katerndahl DA, & Parchman M (2002). The ability of the stress process model to explain mental health outcomes. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 43(5), 351–360. 10.1053/comp.2002.34626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough ME, Riccardi CJ, Timpano KR, Mitchell MA, & Schmidt NB (2010). Anxiety symptomatology: The association with distress tolerance and anxiety sensitivity. Behavior Therapy, 41(4), 567–574. 10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krok D (2015). The mediating role of optimism in the relations between sense of coherence, subjective and psychological well-being among late adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 134–139. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyron MJ, Hooke GR, Bryan CJ, & Page AC (2021). Distress tolerance as a moderator of the dynamic associations between interpersonal needs and suicidal thoughts. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 1–12. 10.1111/sltb.12814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JA (2015). Counseling emerging adults in transition: Practical applications of attachment and social support research. The Professional Counselor, 5(1), 30–42. 10.15241/jal.5.1.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JA, Leibert TW, & Goka-Dubose E (2017). The impact of life transition on emerging adult attachment, social support, and well-being: A multiple-group comparison. Journal of Counseling & Development, 95(4), 378–388. 10.1002/jcad.12153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le TP, Iwamoto DK, & Burke LA (2020). A longitudinal investigation of racial discrimination, distress intolerance, and psychological well-being in African American college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77. 10.1002/jclp.23054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB, Neblett EW Jr., & Jackson V (2015). The role of optimism and religious involvement in the association between race-related stress and anxiety symptomatology. Journal of Black Psychology, 41(3), 221–246. 10.1177/0095798414522297 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, & Bernstein A (2010). Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin, 136(4), 576–600. 10.1037/a0019712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Wang SW, Zhou JJ, Ren QZ, & Gao YL (2020). The direct and indirect effect of event severity, social support, and optimism on stress-related growth in emerging adults. Psychology Health and Medicine (pp. 1–7). Advance online publication,. 10.1080/13548506.2020.1804066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Cheng Y, Hsu ASC, Chen C, Liu J, & Yu G (2018). Optimism and self-efficacy mediate the association between shyness and subjective well-being among Chinese working adults. PLoS One, 13(4), Article e0194559. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, & Luecken LJ (2008). How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Health Psychology, 27, S99–S100. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2 (Suppl.). S99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne VL, Chavira DA, Fernandez S, & Liu PJ (2006). The scale of ethnic experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86, 150–161. 10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, & Schutte NS (2017). Can psychological interventions increase optimism? A meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(6), 594–604. 10.1080/17439760.2016.1221122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Obradović J, & Burt KB (2006). Resilience in emerging adulthood: developmental perspectives on continuity and transformation. In Arnett JJ, & Tanner JL (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 173–190). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/11381-007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, & Barnes NW (2007). Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 201–225. 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Kertz SJ, Weiss RB, Baskin-Sommers AR, Hearon BA, & Björgvinsson T (2014). Changes in distress intolerance and treatment outcome in a partial hospital setting. Behavior Therapy, 45(2), 232–240. 10.1016/j.beth.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazé C, & Verlhiac J-F (2013). Stress et stratégies de coping d′étudiants en première année universitaire: Rôles distinctifs de facteurs transactionnels et dispositionnels [Stress and coping strategies of first-year students: Distinctive roles of transactional and dispositional factors]. Psychologie Française, 58(2), 89–105. 10.1016/j.psfr.2012.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics (2019). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups. Retrieved from 〈https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_rea.asp〉.

- Noe-Bustamante L & Flores A (2019). Facts on Latinos in the U.S Retrieved from 〈www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/fact-sheet/latinos-in-the-u-s-fact-sheet/〉.

- Odom EC, & Vernon-Feagans L (2010). Buffers of racial discrimination: Links with depression among rural African American mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(2), 346–359. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00704.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsillo SM, & Roemer L (2005). Series in anxiety and related disorders. Acceptance and mindfulness-based approaches to anxiety: Conceptualization and treatment. Springer Science + Business Media. 10.1007/b136521 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orsillo SM, Roemer L, & Barlow DH (2003). Integrating acceptance and mindfulness into existing cognitive-behavioral treatment for GAD: A case study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10(3), 222–230. 10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80034-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park IJK, Wang L, Williams DR, & Alegría M (2017). Coping with racism: Moderators of the discrimination-adjustment link among Mexican-origin adolescents. Child Development, 89(3), e293–e310. 10.1111/cdev.12856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30(3), 241–256. 10.2307/2136956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CM, Nicholson BC, Dahlen ER, & Leuty ME (2019). Overparenting and emerging adults’ mental health: The mediating role of emotional distress tolerance. Journal of Child and Family Studies. Advance online publication,. 10.1007/s10826-019-01603-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Daughters SB, Bornovalova MA, Brown RA, & Lejuez CW (2011). Substance use disorders. In Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, & Vujanovic AA (Eds.), Distress tolerance: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 171–197). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/National Public Radio. (2017). Discrimination in America: Experiences and views of Latinos. Retrieved from 〈www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2017/10/discrimination-in-america-experiences-and-views.html〉.

- Roemer L, & Orsillo SM (2002). Expanding our conceptualization of and treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: Integrating mindfulness/acceptance-based approaches with existing cognitive-behavioral models. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9(1), 54–68. 10.1093/clipsy/9.1.54 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh D, Camart N, & Romo L (2017). Predictors of stress in college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 19. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandín B, Simons JS, Valiente RM, Simons RM, & Chorot P (2017). Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of The Distress Tolerance Scale and its relationship with personality and psychopathological symptoms. Psicothema, 29(3), 421–428. 10.7334/psicothema2016.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, & Carver CS (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219–247. 10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, & Bridges MW (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078. 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC (2005). Optimism and immunity: Do positive thoughts always lead to positive effects? Brain Behavior and Immunity, 19(3), 195–200. 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Evans DR, & Eisenlohr-Moul TA (2011). Optimism and pessimism dimensions in the Life Orientation Test-Revised: Method and meaning. Journal of Research in Personality, 45, 126–129. 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ (2000). Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 667–692. 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, & Gaher RM (2005). The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion, 29, 83–102. 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slabbert A, Hasking P, Notebaert L, & Boyes M (2020). The role of distress tolerance in the relationship between affect and NSSI. Archives of Suicide Research, 1–15. 10.1080/13811118.2020.1833797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, & MacKenzie J (2006). Personality and risk of physical illness. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 435–467. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Spencer SJ, & Lynch M (1993). Self-image resilience and dissonance: The role of affirmational resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(6), 885–896. 10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(5), S41–S53. 10.1177/0022146510383499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo MA, Vallejo-Slocker L, Fernández-Abascal EG, & Mañanes G (2018). Determining factors for stress perception assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) in Spanish and other European samples. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 37. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA (2007). Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 65, 1524–1535. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner DM (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review, 101(1), 34–52. 10.1037/0033-295x.101.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warttig SL, Forshaw MJ, South J, & White AK (2013). New, normative, English-sample data for the short form perceived stress scale (PSS-4). Journal of Health Psychology, 18, 1617–1628. 10.1177/1359105313508346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AD, Thompson J, & Andrews G (2013). The impact of psychological distress tolerance in the treatment of depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51 (8), 469–475. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2003). Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 200–208. 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, & Soulsby J (2000). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory in formerly depressed patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(1), 150–155. 10.1037/0021-843X.109.1.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Retrieved from 〈www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf〉.

- Zegel M, Rogers AH, Vujanovic AA, & Zvolensky MJ (2021). Alcohol use problems and opioid misuse and dependence among adults with chronic pain: The role of distress tolerance. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35(1), 42–51. 10.1037/adb0000587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]