Abstract

Dual toll‐like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR8 inhibitor enpatoran is under investigation as a treatment for lupus and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pneumonia. Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PopPK/PD) model‐based simulations, using PK and PD (inhibition of ex vivo‐stimulated interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and interferon‐α (IFN‐α) secretion) data from a phase I study of enpatoran in healthy participants, were leveraged to inform dose selection for lupus and repurposed for accelerated development in COVID‐19. A two‐compartment PK model was linked to sigmoidal maximum effect (Emax) models with proportional decrease from baseline characterizing the PD responses across the investigated single and multiple doses, up to 200 mg daily for 14 days (n = 72). Concentrations that maintain 50/60/90% inhibition (IC50/60/90) of cytokine secretion (IL‐6/IFN‐α) over 24 hours were estimated and stochastic simulations performed to assess target coverage under different dosing regimens. Simulations suggested investigating 25, 50, and 100 mg enpatoran twice daily (b.i.d.) to explore the anticipated therapeutic dose range for lupus. With 25 mg b.i.d., > 50% of subjects are expected to achieve 60% inhibition of IL‐6. With 100 mg b.i.d., most subjects are expected to maintain almost complete target coverage for 24 hours (> 80% subjects IC90,IL‐6 = 15.5 ng/mL; > 60% subjects IC90,IFN‐α = 22.1 ng/mL). For COVID‐19, 50 and 100 mg enpatoran b.i.d. were recommended; 50 mg b.i.d. provides shorter IFN‐α inhibition (median time above IC90 = 13 hours/day), which may be beneficial to avoid interference with the antiviral immune response. Utilization of PopPK/PD models initially developed for lupus enabled informed dose selection for the accelerated development of enpatoran in COVID‐19.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

☑ Enpatoran is a novel, highly selective and potent inhibitor of toll‐like receptors 7 and 8, which has demonstrated efficacy in mouse models of lupus, was well‐tolerated in the phase I study in healthy participants and has the potential to be an effective disease‐modifying therapy for patients with lupus.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

☑ Through modeling and simulation, this study informed dose selection for early clinical trials of enpatoran in indications of high unmet medical needs.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

☑ This work provides a quantitative description of the pharmacokinetics (PKs) and PK/pharmacodynamic (PD) relationship of enpatoran using population modeling. Model‐based simulations, combined with preclinical efficacy and clinical safety data, supported investigation of a twice daily dosing regimen in patients with systemic or cutaneous lupus erythematosus (NCT04647708) and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pneumonia (NCT04448756).

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

☑ The study demonstrates how early population PK and PD models can be repurposed to support accelerated clinical development of a novel compound to treat COVID‐19 pneumonia.

Enpatoran is a novel, highly selective and potent dual inhibitor of toll‐like receptor (TLR)7 and TLR8, which is being developed as an oral therapy for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, including systemic and cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SLE/CLE). 1 , 2 The in vitro and in vivo properties of enpatoran suggest that it has the potential to be an effective disease‐modifying therapy, potentially inhibiting the pathologic activity of ribonucleic acid (RNA)‐containing immune complexes and reducing disease progression in patients suffering from SLE, CLE, and other autoimmune diseases. Abundant data in blood and skin biopsies of patients with SLE and CLE have shown how increased cytokine levels (including interferon (IFN), interlekin‐6 (IL‐6), and TNFα) and expression of the type I IFN gene signature, all downstream effects of activating TLR7 and TLR8, correlate with disease activity and play a central role in disease pathogenesis. 3 , 4

TLR7/8 are mediators of the immune response to single‐stranded RNA (ssRNA) viruses and recent studies have shown that TLR7 is essential for type I IFN immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) in the respiratory tract. 5 However, the dysregulated release of cytokines, known as cytokine storm, can trigger an excessive inflammatory and immune response, leading to the life‐threatening complication of acute respiratory distress syndrome in severe cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). 6 , 7 Although not fully understood, it is postulated that one potential mechanism of cytokine storm development is via activation of the inflammation regulator nuclear factor‐kappa B (NF‐κB) following interaction of SARS‐CoV‐2 and pattern recognition receptors 6 (such as TLR7/8). Therefore, inhibition of TLR7/8 has the potential to prevent hyperinflammation and progression to cytokine storm in severe COVID‐19. 7 In response to the global pandemic, a phase II trial of enpatoran in patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 pneumonia was conducted.

Enpatoran was shown to be highly selective and potent against TLR7/8 in a range of in vitro and in vivo assays, blocking both synthetic and endogenous TLR7/8 ligands in vitro, including RNA oligonucleotides derived from Alu transposable elements. 1 Enpatoran was efficacious in both the BXSB‐Yaa and IFN‐α‐accelerated NZB/W mouse models of lupus, suppressing disease development at doses of ≥ 1 mg/kg. 1

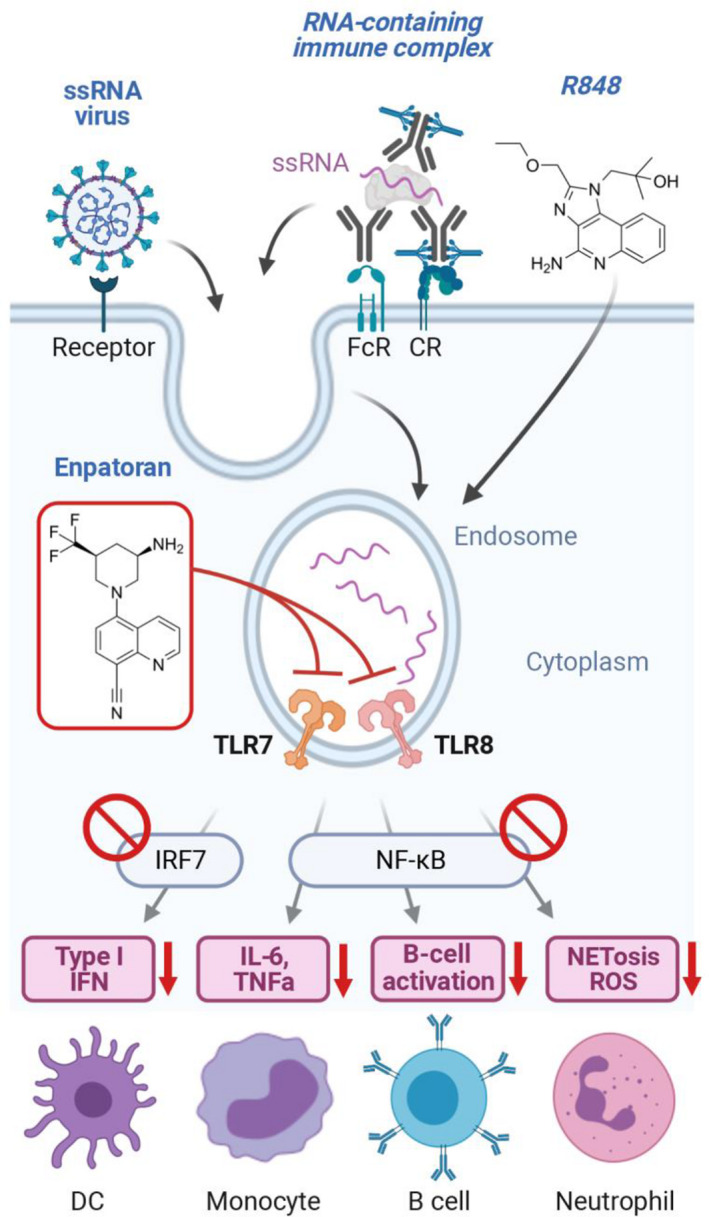

To assess the extent and duration of target engagement required for efficacy, pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) experiments were performed in mice. Activation of TLR7 and TLR8 leads to type I IFN regulatory factor‐ and NF‐kB‐dependent signaling, resulting in the secretion of pro‐inflammatory cytokines including IFN‐α and IL‐6. These cytokines were used as PD biomarkers to quantify the inhibitory activity of enpatoran on TLR7/8 (Figure 1 ). As TLR7/8 are not active under normal healthy conditions, the TLR7/8 agonist R848 (resiquimod) 8 , 9 was used to stimulate the production of IL‐6 and IFN‐α ex vivo. The lowest efficacious dose in mice of 1 mg/kg enpatoran was associated with at least 60% inhibition of IL‐6 secretion throughout 24 hours.

Figure 1.

Activation of the TLR7/8 pathway by ssRNA viruses (such as SARS‐CoV‐2), RNA‐containing immune complexes, or the dual TLR7/8 agonist R848 is blocked by enpatoran. Downstream cytokines IL‐6 and IFN‐α were used in PD assessments to indirectly assess TLR7/8 occupancy by enpatoran. CR, complement receptor; DC, dendritic cell; FcR, Fc receptor; IFN, interferon; IRF7, interferon regulatory factor 7; IRAK1/4, interleukin receptor‐associated kinases 1 and 4; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; mDCs, MYD88, myeloid differentiation primary response 88; NETosis, neutrophil extracellular trap death; NF‐κB, nuclear factor‐kappa B; PD, pharmacodynamic; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome‐coronavirus 2; ssRNA, single‐stranded RNA; TLR7/8, toll‐like receptor 7/8; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

A phase I, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, first‐in‐human, single and multiple ascending dose clinical study that assessed the safety, tolerability, PKs, and PDs of enpatoran in healthy participants was completed (NCT03676322). 2 During the study, preliminary population PK (PopPK) and PK/PD (PopPK/PD) models were developed from emerging enpatoran PK and PD data and updated in real‐time to evaluate safety margins and guide dosing regimen adaptations during the study. Moreover, by integrating the PK and PD data across the investigated subjects and dose levels, the models captured and derived informative PK and PD characteristics of enpatoran in humans to support further clinical development.

In this work, we present the model‐derived PK and PD characteristics of enpatoran in humans and describe how the developed PopPK and PopPK/PD models were further leveraged to guide rapid and informed dose selection for clinical trials in lupus and COVID‐19 pneumonia.

METHODS

Clinical data used to develop the PopPK and PopPK/PD models

PopPK and PopPK/PD models were developed using data from the phase I healthy participant study (NCT03676322) 2 by applying nonlinear mixed effects modeling methods. 10

The final dataset included 72 healthy participants who received either a single dose (range: 1–200 mg) or multiple daily doses (range: 9–200 mg) of enpatoran for 14 days, contributing a total of 1,223 PK and 814 PD (IL‐6 and IFN‐α) measurements. PK and PD sample collections are described in the Supplementary Materials S1 . The population consisted of 72 White adults, 2 of whom were women, with a geometric mean age of 32 (range: 20–45) years and geometric mean body mass index of 25 (range: 20–29) kg/m2. The study was performed in accordance with international guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki and Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Bavarian Chamber of Physicians, Munich, Germany. 2 All participants gave informed consent. 2

The lower limits of quantification (LLOQ) of the PK, IL‐6, and IFN‐α assays were 20 pg/mL, 14 ng/mL, and 0.66 pg/mL, respectively. Nine percent of PK measurements were below the LLOQ. Because most of these samples were late postdose samples (e.g., 120 hours postdose), their impact on PK model estimates and future PK predictions were considered negligible and they were excluded from the analysis. Stimulated and unstimulated (negative control) cytokine values that were below the LLOQ were set to half of the LLOQ. For the PD model analyses, normalized cytokine values were used (derived by subtracting the negative control from the stimulated values).

Model development and evaluation

Several structural and statistical PK models were investigated: one‐ to three‐compartments, exploring including/excluding absorption lag time and random‐effects terms with or without correlations. Enpatoran PK was best described with a two‐compartment PopPK model with first order absorption including an absorption lag time and first order elimination processes. The choice of a two‐compartment model over a one‐compartment model was guided by improved model performance with respect to statistical and graphical criteria (model convergence, reduction in objective function value, and goodness‐of‐fit plots), which allowed representation of relevant exposure metrics (e.g., maximum and minimum concentrations of enpatoran). The model was further refined by considering correlations (i.e., covariances, also referred to as off‐diagonal elements of the OMEGA matrix) between the random‐effects terms (interindividual variability (variance) (IIV)) among apparent oral clearance (CL/F), peripheral volume of distribution, and intercompartmental flow, which may be partly attributed to variability in bioavailability (F) after oral absorption. Moreover, performing simulations with a model that considers the variance‐covariance matrix of random effects allows the sampling of more realistic individual parameters sets, as compared with assuming that no correlations exist. The structural PK parameter estimates were in line with the parameters derived using noncompartmental analysis. 2

For both PD biomarkers (ex vivo‐stimulated IL‐6 and IFN‐α), the developed PopPK model was linked to a direct response PopPD model by integrating individual PK and PD data from single and multiple dosing cohorts into the model. A direct response modeling approach was applied as the TLR7/8‐dependent PD response was stimulated ex vivo, and prior graphical explorations of the PK/PD relationship displayed no hysteresis loop. Specifically, model‐predicted enpatoran concentrations from individual PK parameter estimates were used to drive the respective PD biomarker effect and modeled applying an inhibitory direct response sigmoidal Emax model with proportional decrease from baseline and combined residual error model. Several structural and statistical PD submodels were initially explored: inhibitory Emax models with and without baseline or Hill factor, unfixed/fixed maximum inhibition (IMAX) parameter, including IIVs with and without estimating correlations, investigating proportional and combined additive and proportional residual error models. IL‐6 and IFN‐α release was completely inhibited at high enpatoran concentrations and thus, the IMAX was set to 1 (i.e., 100%) in both models. IIV on IMAX was negligible (< 5%) and therefore excluded. IC60 and IC90 (60% and 90% inhibitory concentrations) values were derived for both cytokines based on estimated IC50 and Hill factors, both > 1.5, using the re‐arranged Emax model equation:

Model evaluations were based on goodness‐of‐fit plots and visual predictive checks (n replicates = 1,000), 11 as well as statistical criteria (e.g., precision of parameter estimates).

Due to the homogeneity of the healthy participant study population (see demographics above), explorations of covariate submodels will be assessed at a later stage with data integrated across studies (larger sample size and covariate distribution). Because the developed population models captured both the typical PK/PD behavior as well as the distribution/range of individual behaviors, they fulfill their purpose for subsequent simulations to compare several dosing scenarios at the population level.

Dose selection criteria and simulations

To determine the dosing regimens for clinical studies, stochastic simulations (1,000 simulated subjects) were performed using the developed models considering interindividual and residual unexplained variability. For both indications, the percentage of simulated subjects with minimum concentrations at steady‐state (Cmin,ss) above IC50 and IC90 of ex vivo‐stimulated IL‐6 and IFN‐α release, and maximum concentrations at steady‐state (Cmax,ss) were evaluated. The highest dose evaluated in the simulations was 200 mg daily, corresponding to the highest dose used in clinical studies to date.

Preclinical data in mouse models of lupus showed that enpatoran exposure at the minimally efficacious dose (1 mg/kg) was associated with 60% inhibition of IL‐6 release over 24 hours. 1 Based on this, 60% inhibition of ex vivo‐stimulated IL‐6 secretion at Cmin,ss in > 50% of human subjects over 24 hours was set as the minimum target for PD modulation and formed the basis for the lowest recommended dose in lupus clinical trials. Therefore, IC60 coverage was also assessed for lupus.

No preclinical data for in vivo efficacy of enpatoran treatment in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection models were available to guide indication‐specific dose selection for COVID‐19. However, it was hypothesized that strong TLR7/8 inhibition (i.e., achieving IC90) would be required for at least a couple of hours per day to prevent patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia developing an aggressive hyperinflammation. The optimum dose should inhibit NF‐κB‐driven cytokine production (e.g., IL‐6) while allowing an antiviral immune response (e.g., IFN) sufficient to combat the infection. Therefore, simulations were performed for both IL‐6 and IFN‐α, and IC90 and IC50 were assessed.

Software

Model parameter estimations (first‐order conditional estimation method with interaction algorithm) and simulations were performed using NONMEM (version 7.3.0; ICON Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA) and organized by Perl‐speaks‐NONMEM (PsN version 4.4.8; Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden). For organization of runs and run reporting, Pirana software (version 2.9.2; Pirana Software & Consulting, Denekamp, The Netherlands) was used. Pre‐ and postprocessing modeling and simulation activities, exploratory analysis, and graphical model diagnostics were carried out in R (version 3.5.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using RStudio (version 1.0.153; RStudio Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

RESULTS

Developed models and PK and PD properties

The PK of enpatoran was best described with a two‐compartment PopPK model with first order absorption, including an absorption lag time and first order elimination processes (Table S1 ). PK parameters were estimated with appropriate precision with the most relevant PK parameter CL/F and its IIV being estimated with high precision (relative standard error 3.3% and 16.5%, respectively). Variability in CL/F across subjects was 27.5% coefficient of variation (CV). In general, the PopPK model appeared to perform well, capturing the typical behavior and the variability across subjects and cohorts, as apparent from the diagnostic plots (top row of Figure 2 , and Figures S1 – S6 ).

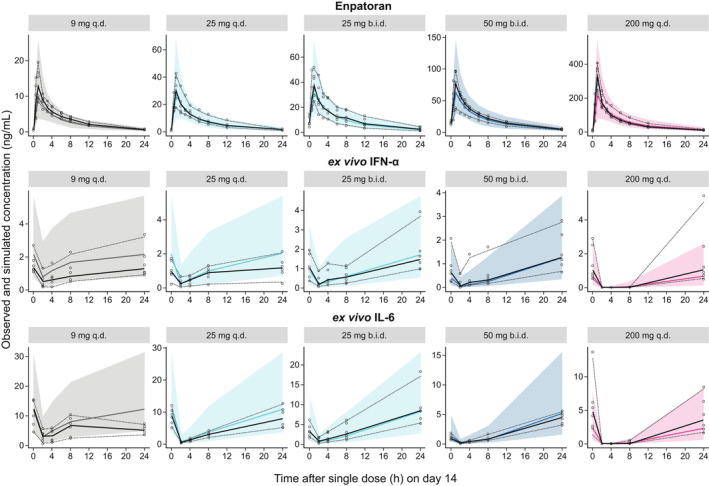

Figure 2.

Visual predictive check for plasma enpatoran PK and PD profiles following multiple dosing. Observed (n = 72) and PopPK/PD model simulated (n = 1,000 subjects per dosing scenario) plasma concentrations of enpatoran and ex vivo‐stimulated IL‐6 and IFN‐α over time on day 14 of multiple oral dose administration (9, 25, and 200 mg q.d., and 25 mg and 50 mg b.i.d.). The b.i.d. dosing cohorts received only the morning dose of 25 or 50 mg on day 14. Solid colored line = simulated median value; shaded colored area = simulated 2.5–97.5th percentiles; circles = observed data; solid black line = observed median value; dotted lines = observed 2.5–97.5th percentiles. b.i.d., twice daily; IFN‐α, interferon alpha; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; PD, pharmacodynamic; PK, pharmacokinetic; PopPK, population pharmacokinetic; PopPK/PD, population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic; q.d., once daily. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The relationship between enpatoran PK and longitudinal PD biomarker data was appropriately described by an inhibitory direct response sigmoidal Emax model with proportional decrease from baseline and combined residual error model, with continuous enpatoran concentrations directly driving the PD effect (Table S2 ). The PopPK/PD models for IL‐6 and IFN‐α adequately described the underlying cytokine release data, as apparent from the diagnostic plots (middle and bottom row of Figure 2 , and Figures S2 – S7 ).

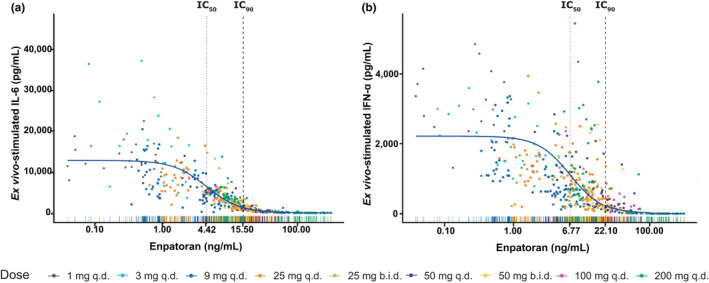

As anticipated from exploratory graphical analysis, the estimated variability in PD values at baseline across subjects was large (50–55% CV; Figure S7 ) and decreased proportionally with increasing enpatoran concentrations resulting in complete inhibition (100%) of cytokine release (Figure 3 ). The PopPK/PD model determined slightly lower IC50 and IC90 for IL‐6 compared with IFN‐α. The IIV in IC50 was larger for IFN‐α compared with IL‐6 (50% vs. 30% CV, respectively; Figure S7 ). Corresponding IC60 and IC90 values were 5.59 and 15.5 ng/mL for IL‐6, and 8.43, and 22.1 ng/mL for IFN‐α, respectively. The steepness of the response vs. concentration slopes, as described by the Hill factors, were comparable for IL‐6 (1.75) and IFN‐α (1.86). Based on these observed exposure–response relationships, slightly higher enpatoran concentrations were required to inhibit IFN‐α release compared with IL‐6.

Figure 3.

Exposure–response relationship between enpatoran plasma concentrations and ex vivo‐stimulated IL‐6 (a) and IFN‐α (b) release from 72 healthy subjects across single and multiple dose cohorts of the phase I study. Solid blue slope = typical profile applying PK/PD models; Rugs on x‐axis = distribution of enpatoran concentrations colored by dosing regimen. b.i.d., twice daily; IC, inhibitory concentration; IFN‐α, interferon alpha; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; PD, pharmacodynamic; PK, pharmacokinetic; q.d., once daily.

Model‐based evaluation of once daily and twice daily dosing scenarios

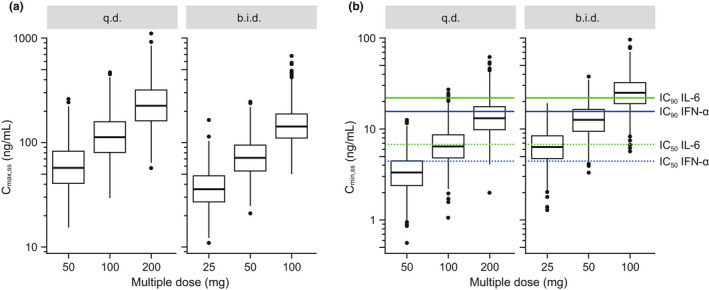

The PopPK model was used to simulate and compare q.d. and b.i.d. dosing regimens. This was motivated by the high apparent clearance of enpatoran in humans, with an estimated typical CL/F of 144 L/hour. Therefore, it was hypothesized that TLR7/8 inhibition might not be sufficiently maintained throughout the day despite achieving high Cmax,ss from q.d. dosing (Figure 4a ).

Figure 4.

Simulated Cmax,ss (a) and Cmin,ss (b) across q.d. and b.i.d. dosing regimens using the PopPK model (n = 1,000 subjects per dosing scenario). For boxplots, boxes represent interquartile ranges, horizontal lines are medians, whiskers extend to the most extreme value, which is no more than 1.5 times the box length, and points are outliers. b.i.d., twice daily; Cmax,ss, maximum concentration at steady‐state; Cmin,ss, minimum concentration at steady‐state; IC50/90, 50/90% inhibitory concentrations; IFN‐α, interferon alpha; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; PopPK, population pharmacokinetic; q.d., once daily. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

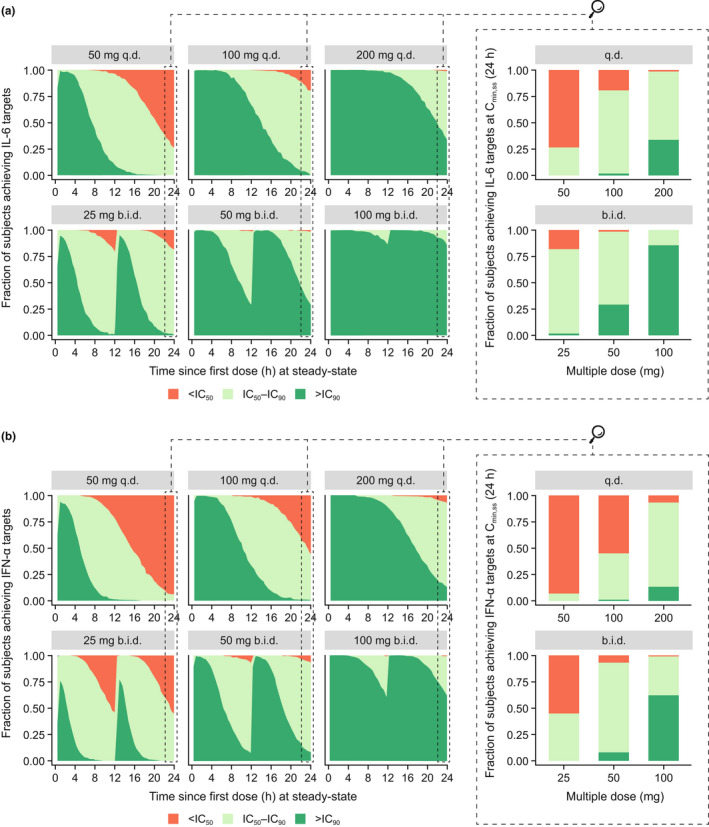

Simulation results supported the b.i.d. over q.d. dosing regimen when comparing the fraction of subjects achieving IL‐6 and IFN‐α targets at Cmin,ss (Table 1 , Figure 4b ). In general, IL‐6 and IFN‐α target coverage for IC50 and IC90 was maintained for longer duration over 24 hours with increasing daily dose (Figure 5 , panels from left to right), and more frequently under b.i.d. compared to q.d. dosing scenarios (Figure 5 , top vs. bottom). For example, 86% and 35% of simulated subjects achieved 90% inhibition of IL‐6 release at Cmin,ss with 100 mg b.i.d. and 200 mg q.d., respectively (Table 1 , Figure 5a ).

Table 1.

Percent of simulated subjects with Cmin,ss above IC50, IC60, and IC90 for ex vivo‐stimulated IL‐6 and IFN‐α with enpatoran q.d. or b.i.d. dosing

| IL‐6 | IFN‐α | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enpatoran dose | q.d. | b.i.d. | q.d. | b.i.d. | ||||||||

| 50 mg | 100 mg | 200 mg | 25 mg | 50 mg | 100 mg | 50 mg | 100 mg | 200 mg | 25 mg | 50 mg | 100 mg | |

| Percentage above IC90 over 24 hours | 0 | 2.3 | 34.8 | 1.0 | 29.2 | 86.0 | 0 | 0.4 | 13 | 0 | 8.1 | 62.5 |

| Percentage above IC60 over 24 hours | 11.7 | 62.5 | 97.0 | 63.1 | 97.1 | 100 | 2.4 | 26.9 | 83.9 | 24.7 | 83.5 | 98.9 |

| Percentage above IC50 over 24 hours | 25.7 | 81.1 | 98.8 | 80.8 | 98.9 | 100 | 6.3 | 44.3 | 93.3 | 44.3 | 92.8 | 99.6 |

b.i.d., twice daily; Cmin,ss, minimum concentration at steady state; IC50/60/90, 50/60/90% inhibitory concentrations; IFN‐α, interferon alpha; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; q.d., once daily.

Figure 5.

Fraction of simulated subjects achieving IL‐6 (a) and IFN‐α (b) targets throughout the day following continuous enpatoran q.d. and b.i.d. dosing. Enpatoran q.d. and b.i.d. PK profiles over 24 hours at PK steady‐state were simulated (n = 1,000 per dosing scenario) using the PopPK model and the proportion of simulated subjects achieving IL‐6 and IFN‐α inhibition was evaluated across 24 hours. The magnified panels show the fraction of subjects achieving IL‐6 and IFN‐α targets at Cmin,ss at 24 hours. The dark green area represents the proportion of simulated subjects achieving at least 90% inhibition of IL‐6 or IFN‐α release over time. The light green area represents the proportion of simulated subjects achieving between 50 and 90% inhibition of IL‐6 or IFN‐α release, and the orange area represents those achieving < 50% inhibition, over time. b.i.d., twice daily; Cmin,ss, minimum concentration at steady state; IC50/90, 50/90% inhibitory concentrations; IFN‐α, interferon alpha; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; PK, pharmacokinetic; PopPK, population pharmacokinetic; q.d., once daily. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

IL‐6 vs. IFN‐α target inhibition

The simulations underlined the differential inhibitory effect of enpatoran on ex vivo‐stimulated cytokine release. Across all dosing regimens, fewer simulated subjects achieved 90% inhibition of IFN‐α over 24 hours compared with IL‐6 (Figure 5 , a vs. b). With 100 mg b.i.d., 63% of subjects were expected to maintain 90% inhibition of IFN‐α release over 24 hours (compared with 86% of subjects for IL‐6; Table 1 ).

Dose selection

At the lowest investigated dose of 25 mg b.i.d., IL‐6 coverage of IC50 was maintained in 81% of simulated subjects throughout the day. The minimum efficacious dose in lupus mice was associated with 60% inhibition of IL‐6 secretion throughout 24 hours. Similarly, with 25 mg b.i.d., 63% of subjects are expected to achieve enpatoran exposures sufficient to maintain IC60 of IL‐6 for the entire day (Table 1 ). Under the assumption that 60% PD target attainment is required for efficacy and that preclinical results are translatable to humans, the simulations suggested evaluation of 25 mg b.i.d. as the minimum dose in future lupus trials.

With 50 mg b.i.d., almost all subjects (> 97%) maintained IC50 for IL‐6 for 24 hours, whereas 29% of subjects were expected to maintain IC90 for IL‐6. For IFN‐α with 50 mg b.i.d. dosing, 93% and 8% of subjects are expected to achieve IC50 and IC90, respectively, for 24 hours (Table 1 ). With 100 mg b.i.d., almost all subjects (> 99%) maintained enpatoran concentrations above IC50 of IL‐6 and IFN‐α.

To maximize the number of subjects achieving IC60 IL‐6 coverage and due to uncertainties in the translation of preclinical lupus model results to human patients with lupus, it was proposed to investigate additional higher doses. With 50 mg and 100 mg b.i.d., the number of subjects maintaining IC50 for IFN‐α for 24 hours is maximized (93% and > 99%, respectively) and almost complete target coverage of IL‐6 (IC90) is expected to be maintained with 100 mg b.i.d. in 86% of subjects.

For COVID‐19, 100 and 50 mg enpatoran b.i.d. were recommended; the majority of subjects are expected to achieve IC90 for IL‐6 throughout the day with 100 mg b.i.d., whereas 50 mg b.i.d. provides shorter IFN‐α inhibition (median time above IC90 = 13 hours/day), which may be beneficial to avoid interference with the antiviral immune response.

DISCUSSION

Under normal physiologic conditions, activation of the TLR7 and TLR8 pathways by ssRNA results in a protective antiviral response. Although TLR7/8 have evolved as sensors of viral ssRNA, their aberrant activation by endogenous RNA may drive inflammation and autoimmunity, and as such TLR7/8 are postulated to be involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, such as SLE. 12 , 13 , 14 Additionally, TLR7/8 may play an important role in the hyperinflammation associated with ssRNA viruses, such as COVID‐19. 15 Therefore, enpatoran, a highly selective and potent TLR7/8 inhibitor, is currently under investigation for the treatment of SLE/CLE and COVID‐19 pneumonia, and may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for these indications of high and urgent unmet medical need.

To inform the dose selection in early clinical development programs, PopPK and PopPK/PD models were successfully developed from phase I PK and PD data. The models generated a quantitative description of the PK and PK/PD relationship of enpatoran and, importantly, provided a tool to compare alternative dosing scenarios for investigation in future clinical trials. The PopPK and PopPK/PD models were based on data from healthy volunteers that may underestimate PK and PD variability in patients. To mitigate this, a conservative PK/PD metric of Cmin,ss above IC90 for the entire day was chosen, and target attainment was based on a large simulated population (n = 1,000).

Enpatoran PK and PD characteristics

As reflected in the plasma PK profiles and confirmed with parameter estimation, enpatoran was rapidly absorbed after oral administration and displayed daily PK fluctuations with Cmax,ss/Cmin,ss ratios of 5.7 and 18 for b.i.d. and q.d., respectively. The initial steep decline, expected to reflect the competing processes of rapid distribution into tissues (intercompartmental flow) and elimination of enpatoran (CL/F), was followed by a less steep decline, representing the terminal elimination phase from the body. Under the assumption that enpatoran is almost exclusively eliminated via metabolism in the liver (other routes are considered negligible) and a large fraction of the oral dose is systemically available (F > 85%), 1 the estimated CL/F should approximately represent the hepatic CL in humans. The relatively high CL/F may be attributed to enpatoran metabolism via the aldehyde oxidase enzyme, which has been shown in vitro. 1

Enpatoran has a relatively large volume of distribution (even if F is low), which is comparable to small molecules with similar physicochemical properties, and hence distributes well from the circulation into tissues. This is consistent with observations of enpatoran tissue distribution in rats based on whole body autoradiography, and its physicochemical properties (i.e., being lipophilic (logP: 2) and highly permeable (Caco‐2 permeability: 26 × 10−6 cm/s)). 1

Notably, TLR7/8 activation by R848 is artificial, and the binding specificity and extent of pathogenic ligands are expected to vary; therefore, the IC50 under R848 stimulation should be considered with care. However, enpatoran has been shown in vitro and in vivo to inhibit synthetic ligands as well as natural endogenous RNA ligands, such as microRNA and Alu RNA, 1 suggesting that enpatoran potently inhibits TLR7/8 irrespective of the stimulatory counterpart.

Simulations of dosing regimens

Based on the simulations reported here, the b.i.d. dosing regimen was superior to the q.d. equivalent daily dose in maximizing time above PD targets (Cmin,ss > IC), but also lowering Cmax values, thereby providing smaller peak‐to‐trough fluctuations and larger safety margins for Cmax (e.g., 200 mg q.d. vs. 100 mg b.i.d.). To date, clinical safety data support exposures up to the highest clinically investigated multiple dose of 200 mg enpatoran daily for 14 days. 2

At the highest proposed dose of 100 mg b.i.d., simulations suggest that most subjects are expected to achieve exposures sufficient for considerable and sustained inhibition of TLR7/8 throughout the day (> 80% of subjects IC90 for IL‐6 = 15.5 ng/mL; > 60% of subjects IC90 for IFN‐α = 22.1 ng/mL). Therefore, enpatoran may represent a valuable treatment option for patients for whom an overactivated TLR7/8 pathway is a significant contributor to their disease progression and/or severity.

Despite the general challenges with adherence to daily or twice‐daily oral drug intake, enpatoran as an oral treatment option with a shorter half‐life may provide certain advantages compared with other treatments with longer half‐lives, especially i.v.‐ or s.c.‐administered monoclonal antibodies: (i) the oral tablet administration is more convenient for patients, (ii) PK steady‐state and target exposure are achieved within a few days of treatment, and (iii) it is possible to make rapid dosing adjustments or withdraw treatment if necessary.

Lupus indications

For the treatment of lupus, simulations supported clinical investigation at 25, 50, and 100 mg enpatoran b.i.d. as the anticipated therapeutic dose range. The fourfold dose range covers a wide range of Cmin,ss across three dose levels, with minimum overlap between the dose groups. Investigating three well‐differentiated dose levels will enable the determination of dose–exposure–response relationships, supporting future safe and efficacious dose selection for lupus trials. Enpatoran is being evaluated for patients with active SLE/CLE (NCT04647708); it is unknown whether the same dose will be effective for different lupus indications.

The lowest dose of 25 mg b.i.d. was selected based on efficacy results from a preclinical lupus disease mouse model and corresponding IL‐6 target coverage. The IFN gene signature is elevated in patients with SLE and blood IFN‐α concentration increases with disease activity. 16 , 17 Therefore, as enpatoran less potently inhibits IFN‐α compared with IL‐6 and due to the uncertainties in preclinical‐to‐clinical translation, if supported by safety data, higher doses may be explored in dose‐ranging studies to increase the number of patients achieving 90% inhibition of IFN‐α throughout 24 hours.

COVID‐19 pneumonia

The global COVID‐19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of applying clinical pharmacology and modeling approaches for the rapid optimization of potential treatments, including the determination of the most appropriate dosage. 18 In contrast to lupus, no preclinical disease model data were available to guide enpatoran dose selection for patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia. To prevent and/or inhibit the aggressive hyperinflammatory immune response (cytokine storm) observed in severe cases of COVID‐19, enpatoran 50 and 100 mg b.i.d. doses were recommended for investigation in the phase II ANEMONE trial (NCT04448756) through modeling and simulation. With b.i.d. dosing, cytokine levels are expected to be largely suppressed throughout the dosing interval. In the acute treatment setting of COVID‐19‐associated cytokine storm, high exposures should be achieved as soon as possible and potentially maintained for a sufficient duration to ensure adequate clearance of infection.

Although interferons seem to play an important role in regulating the immune defense during the first stage of viral infection, it is unclear whether they are protective or harmful in the inflammatory stage of the disease. 19 , 20 , 21 Dual TLR7/8 inhibition by enpatoran leads to slightly differential downstream effects, reflected in relatively stronger inhibition of IL‐6 release than IFN‐α. Consequently, the selection of an appropriate enpatoran dose that allows the immune system to react to foreign pathogens, as well as the timing of TLR7/8 immune modulatory treatment, are important considerations for the successful treatment of severe COVID‐19.

The dynamic and severe nature of COVID‐19 immunopathology is often complicated by a patient’s comorbidities (e.g., obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular complications), co‐medications, and organ support techniques used, and therefore controllable and rapid‐acting treatment options are required. Enpatoran has a short half‐life, penetrates target tissues, and is predicted to have a manageable drug–drug interaction profile. These advantageous PK properties, combined with its novel mode of action as a dual TLR7/8 inhibitor, suggest that enpatoran treatment at a critical point in COVID‐19 progression may have the potential to attenuate hyperinflammation and cytokine storm.

CONCLUSION

The dual TLR7/8 inhibitor enpatoran has the potential to block the pathologic activity of immune complexes in autoimmune diseases, such as lupus, as well as the overt inflammatory response that leads to cytokine storm in severe cases of COVID‐19. 2 The required magnitude of TLR7/8 inhibition must be fine‐tuned in order to ease the progression of diseases driven by this pathway, while maintaining adequate levels of immune protection. In this study, PK and PD data from the phase I first‐in‐human study of enpatoran were used to develop PopPK/PD models and, together with safety data in humans and preclinical efficacy and PK/PD data, informed the rational, data‐driven dose selection for clinical trials in patients with lupus and COVID‐19 pneumonia. Early and continuous population modeling and simulations supported the accelerated clinical development of enpatoran in indications of urgent unmet medical need.

FUNDING

This study was sponsored by the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (CrossRef Funder ID: 10.13039/100009945), who also funded medical writing support by Bioscript Stirling Ltd., Macclesfield, UK.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

L.K.S. and A.K. are employees of the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, and J.V.S., J.Q.D., C.V.M., and K.G. are employees of EMD Serono, Billerica, MA, USA.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors wrote the manuscript. L.K.S., J.V.S., A.K., and K.G. designed the study. L.K.S. performed the research. All authors analyzed the data.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank those who took part in the phase I study of enpatoran, as well as Nuvisan GmBH who conducted the study, and the Medical Monitor Andreas Port (the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The authors would also like to thank Amy Kao (Global Clinical Development, EMD Serono) and Elizabeth Adams (who was employed by Global Clinical Development, EMD Serono at the time of the study) for their valuable clinical and scientific input. Enpatoran clinical development is funded by the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Medical writing support was provided by Bioscript Stirling Ltd., Macclesfield, UK.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Any requests for data by qualified scientific and medical researchers for legitimate research purposes will be subject to the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany’s Data Sharing Policy. All requests should be submitted in writing to the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany’s data sharing portal. When the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, has a co‐research, co‐development, or co‐marketing or co‐promotion agreement, or when the product has been out licensed, the responsibility for disclosure might be dependent on the agreement between parties. Under these circumstances, the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, will endeavor to gain agreement to share data in response to requests.

- 1. Vlach, J. et al. Discovery of M5049: a novel selective TLR7/8 inhibitor for treatment of autoimmunity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 376, 397‐409 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Port, A. et al. Phase 1 study in healthy participants of the safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of enpatoran (M5049), a dual antagonist of toll‐like receptor 7 and 8. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 9, e00842 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dean, G.S. , Tyrrell‐Price, J. , Crawley, E. & Isenberg, D.A. Cytokines and systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 59, 243 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braunstein, I. , Klein, R. , Okawa, J. & Werth, V.P. The interferon‐regulated gene signature is elevated in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus and correlates with the cutaneous lupus area and severity index score. Br. J. Dermatol. 166, 971–975 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asano, T. et al. X‐linked recessive TLR7 deficiency in ~1% of men under 60 years old with life‐threatening COVID‐19. Sci. Immunol. 6, eabl4348 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang, Y. et al. Cytokine storm in COVID‐19: from viral infection to immune responses, diagnosis and therapy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 459–472 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de la Rica, R. , Borges, M. & Gonzalez‐Freire, M. COVID‐19: in the eye of the cytokine storm. Front. Immunol. 11, 558898 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jurk, M. et al. Human TLR7 or TLR8 independently confer responsiveness to the antiviral compound R‐848. Nat. Immunol. 3, 499 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hemmi, H. et al. Small anti‐viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88‐dependent signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 3, 196–200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bauer, R.J. NONMEM Tutorial Part I: description of commands and options, with simple examples of population analysis. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 8, 525–537 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergstrand, M. , Hooker, A.C. , Wallin, J.E. & Karlsson, M.O. Prediction‐corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed‐effects models. AAPS J. 13, 143–151 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mohammad Hosseini, A. , Majidi, J. , Baradaran, B. & Yousefi, M. Toll‐like receptors in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 5, 605–614 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Farrugia, M. & Baron, B. The role of toll‐like receptors in autoimmune diseases through failure of the self‐recognition mechanism. Int. J. Inflamm. 2017, 8391230 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shrivastav, M. & Niewold, T.B. Nucleic acid sensors and type I interferon production in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 4, 319 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khanmohammadi, S. & Rezaei, N. Role of toll‐like receptors in the pathogenesis of COVID‐19. J. Med. Virol. 93, 2735–2739 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Niewold, T.B. Interferon alpha as a primary pathogenic factor in human lupus. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 31, 887–892 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tanaka, Y. State‐of‐the‐art treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 23(4), 465–471 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Venkatakrishnan, K. , Yalkinoglu, O. , Dong, J.Q. & Benincosa, L.J. Challenges in drug development posed by the COVID‐19 pandemic: an opportunity for clinical pharmacology. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 108, 699–702 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee, J.S. & Shin, E.‐C. The type I interferon response in COVID‐19: implications for treatment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 585–586 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin, F. & Shen, K. Type I interferon: from innate response to treatment for COVID‐19. Pediatr. Investig. 4, 275–280 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hadjadj, J. et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID‐19 patients. Science 369, 718–724 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

Any requests for data by qualified scientific and medical researchers for legitimate research purposes will be subject to the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany’s Data Sharing Policy. All requests should be submitted in writing to the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany’s data sharing portal. When the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, has a co‐research, co‐development, or co‐marketing or co‐promotion agreement, or when the product has been out licensed, the responsibility for disclosure might be dependent on the agreement between parties. Under these circumstances, the healthcare business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, will endeavor to gain agreement to share data in response to requests.