Abstract

A 27,690-bp gene cluster involved in the degradation of the plant alkaloid nicotine was characterized from the plasmid pAO1 of Arthrobacter nicotinovorans. The genes of the heterotrimeric, molybdopterin cofactor (MoCo)-, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-, and [Fe-S] cluster-dependent 6-hydroxypseudooxynicotine (ketone) dehydrogenase (KDH) were identified within this cluster. The gene of the large MoCo subunit of KDH was located 4,266 bp from the FAD and [Fe-S] cluster subunit genes. Deduced functions of proteins encoded by open reading frames (ORFs) of the cluster were correlated to individual steps in nicotine degradation. The gene for 2,6-dihydroxypyridine 3-hydroxylase was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. The purified homodimeric enzyme of 90 kDa contained 2 mol of tightly bound FAD per mol of dimer. Enzyme activity was strictly NADH-dependent and specific for 2,6-dihydroxypyridine. 2,3-Dihydroxypyridine and 2,6-dimethoxypyridine acted as irreversible inhibitors. Additional ORFs were shown to encode hypothetical proteins presumably required for holoenzyme assembly, interaction with the cell membrane, and transcriptional regulation, including a MobA homologue predicted to be specific for the synthesis of the molybdopterin cytidine dinucleotide cofactor.

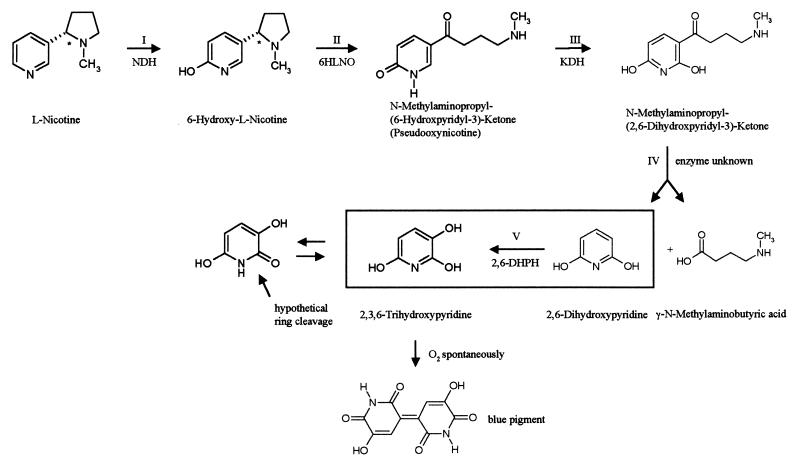

The gram-positive soil bacterium Arthrobacter nicotinovorans (formerly known as Arthrobacter oxidans and reclassified by Kodama et al. [22]) has the ability to use nicotine as its sole carbon and energy source (8, 10, 15, 17). Nicotine, the alkaloid of the tobacco plant, is synthesized as the l-isomer, and the first enzyme to attack l-nicotine is a trimeric, molybdopterin cofactor (MoCo) (most probably in its dinucleotide form [18])-, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-, and [Fe-S] cluster-containing nicotine dehydrogenase (NDH), which hydroxylates the pyridine ring at position 6 (Fig. 1, step I). The pyrrolidine ring of 6-hydroxy-l-nicotine is then oxidized by 6-hydroxy-l-nicotine oxidase (6HLNO) (7) (Fig. 1, step II), and the 6-hydroxypseudooxynicotine formed is once more hydroxylated at position 2 of the pyridine ring by ketone dehydrogenase (KDH) (8, 30) (Fig. 1, step III), an enzyme structured similarly to NDH. The side chain of N-methylaminopropyl-(2,6-dihydroxypyridyl-3)-ketone is cleaved off, resulting in 2,6-dihydroxypyridine and γ-methylaminobutyrate (Fig. 1, step IV). These two compounds have been identified as degradation products of nicotine by A. nicotinovorans (15), but no corresponding enzyme has been identified as yet. 2,6-Dihydroxypyridine is transformed into 2,3,6-trihydroxypyridine by 2,6-dihydroxypyridine 3-hydroxylase (2,6-DHPH) (Fig. 1, step V), an FAD-dependent enzyme that had been partially purified before (19). In the presence of oxygen, 2,3,6-trihydroxypyridine spontaneously forms a blue pigment (20) (Fig. 1), and liquid cultures of A. nicotinovorans grown on nicotine turn dark blue because of the nicotine blue secreted by the bacteria. The genes encoding these enzymes are located on the 160-kb catabolic plasmid pAO1, and the ability to degrade and grow on nicotine is lost when the plasmid is cured from the bacterium (5). The genes ndh and 6hlno have been cloned and sequenced (16, 31). Of the kdh genes, the gene of the small [Fe-S] subunit and of the medium FAD subunit have been cloned and sequenced (30). The gene of the large MoCo subunit, however, could not be established unequivocally, and the organization of the genes on pAO1 has not been identified. It has been shown before that adjacent to the ndh and 6hlno genes, and separated by the insertion sequence IS1473 (26), is a gene cluster consisting of a molybdate ABC transporter and genes involved in MoCo biosynthesis (27).

FIG. 1.

Overview of the steps in nicotine degradation to blue pigment by A. nicotinovorans pAO1. The reaction catalyzed by 2,6-DHPH, cloned and purified in this work, is framed. NDH, nicotine dehydrogenase; 6HLNO, 6-hydroxy-l-nicotine oxidase; KDH, ketone dehydrogenase.

Here we present the organization of the genes on pAO1 involved in the degradation of nicotine, the identification and cloning of the 2,6-DHPH gene in Escherichia coli, and the purification and characterization of the enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA sequencing and sequence analysis.

pAO1 of A. nicotinovorans was isolated according to published methods (5) and partially digested with the restriction enzyme Sau3A. The digest was electrophoresed on a 0.8% agarose gel, and DNA fragments of 2.5 to 10 kb were isolated and cloned into pBlueScript SK (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). In addition, a pAO1 library constructed in the lambda Zap Express vector (Stratagene) was kindly provided by K. Decker (30). Starting from a 10-kb pAO1 fragment in pBlueScript SK (27), overlapping clones were identified by sequencing individual clones and gaps were filled by sequencing PCR products obtained with pAO1 DNA as a template and the Expand Long Template PCR system of Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Mannheim, Germany). Contigs were assembled and edited using the Staden software package (3). Comparisons of DNA sequences and their derived amino acid sequences were performed with the BLAST family of programs (1).

Cloning and purification of 2,6-DHPH.

The DNA fragment bearing the 2,6-dhph gene was amplified with Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) from the pAO1 DNA template, digested with XmaI and KpnI, ligated into the XmaI-KpnI sites of pH6EX3 (2), and transformed into E. coli XL-1 blue bacteria. His6-tagged 2,6-DHPH was purified from bacterial lysates by Ni2+-chelating Sepharose chromatography as recommended by the supplier (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany).

Enzyme assays.

2,6-DHPH activity was assayed photometrically at 25°C in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.1) in the presence of 0.2 mM NADH and 0.1 mM 2,6-dihydroxypyridine using a digital photometer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Enzyme activity was recorded either at 334 nm as the decrease in NADH consumed in the reaction or as the increase in absorption at 578 nm due to the formation of the blue pigment, which was generated from the reaction product 2,3,6-trihydroxypyridine. One unit of enzyme was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the oxidation of 1 μmol of NADH per min under the assay conditions. The Km of the enzyme for 2,6-dihydroxypyridine was determined in assays recorded at 334 nm at seven substrate concentrations ranging from 100 μM to 500 nM. The Kd of the enzyme for NADH was determined at a substrate concentration of 100 μM and at seven NADH concentrations ranging from 200 to 10 μM. The substrate specificity of 2,6-DHPH was tested with various compounds obtained from Sigma (Munich, Germany) (Table 1) at a concentration of 100 μM in the enzyme assay with NADH. The pH optimum of 2,6-DHPH was determined at pH values from 10.0 to 5.0 in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer.

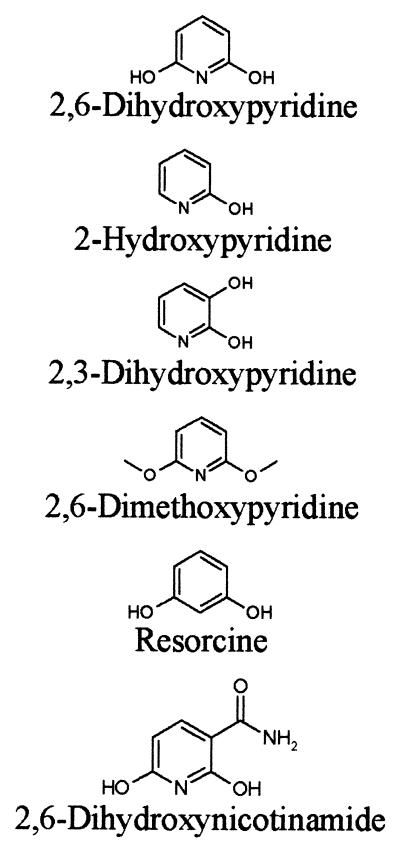

TABLE 1.

Substrate specificity of 2,6 DHPHa

| Substrate | Specific activity (U/mg of protein) | % Activity in presence of 2,6-DHP |

|---|---|---|

|

90 | 100 |

| 0 | 52 | |

| 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 49 | |

| 0 | 45 |

One unit is defined as the conversion of 1 μmol of 2,6-dihydroxypyridine (2,6-DHP) to 1 μmol of 2,3,6-trihydroxypyridine per min.

Preparation of apo-His6-tagged 2,6-DHPH.

To estimate the Kd for FAD, apo-His6-tagged 2,6-DHPH was prepared by precipitation with 50% (NH4)2SO4 at pH 2.0 for 30 min on ice. The precipitated apoenzyme was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and resuspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.1). This preparation was employed to reconstitute 2,6-DHPH holoenzyme by incubation of the apoenzyme for 1 h on ice with FAD concentrations ranging from 500 nM to 500 μM.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 27,690-bp sequence of pAO1 DNA was deposited at GenBank with accession number AF373840.

RESULTS

A gene cluster on pAO1 of A. nicotinovorans is involved in nicotine degradation

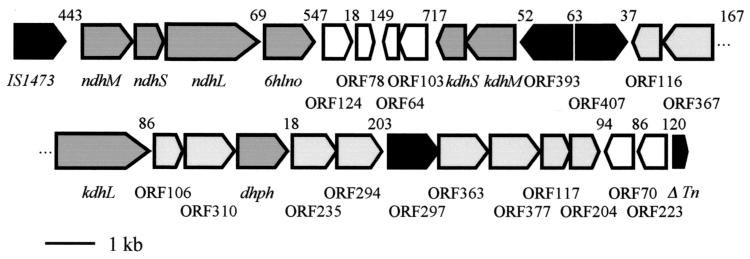

The genes and open reading frames (ORFs) identified on the 27,690-bp pAO1 DNA fragment are presented in Fig. 2. The gene cluster starts with the ndhM, ndhS, ndhL, and 6hlno genes (16). For more clarity, we have used the terms large (L), medium (M), and small (S) instead of C, A, and B for the nomenclature of the subunits of the trimeric MoCo, FAD, [Fe-S] cluster enzymes. The ORFs of kdhS and kdhM were identified further downstream as being transcribed in the opposite direction to the ndh and 6hlno genes. The deduced amino-terminal sequences of KDHS and KDHM correspond to the experimentally determined amino acid sequences XAFRLTVEVNGVTH and MKPPSFDYVVADSVEHALRLLADG, respectively (29). X in the sequence of the small subunit stands for asparagine. The start of KDHM is extended from the previously assumed start site by 43 amino acid residues and contains the experimentally determined amino-terminal sequence MKPPSFDYVVADSVEHALRLLADG (29), which results in a protein with a calculated Mr of 31,429. The ndh and 6hlno genes are separated from the kdhS and kdhM genes by small, hypothetical ORFs (Fig. 2). Contrary to expectations, kdhM was not preceded by an ORF encoding a protein with similarity to known large subunits of MoCo enzymes. However, a corresponding ORF (Fig. 2, kdhL) was located 4,266 bp downstream from kdhM and transcribed in the opposite direction. The deduced amino acid sequence starts with MMAKAKALIPDNGRA and contains the sequence ALIPDNXXA, which had been experimentally deduced previously by amino-terminal sequencing of KDHL (29). Thus, we have the unique situation that the small [Fe-S] cluster subunit and the middle-sized FAD subunit of a trimeric molybdenum enzyme are expressed by genes located at a great distance from the gene of the large MoCo subunit. The deduced amino acid sequence of KDHL shows significant degrees of similarity (64.76%) and identity (32.16%) to the amino acid sequence of NDHL and related large subunits of trimeric MoCo enzymes.

FIG. 2.

Characterization of the 27,690-bp region of A. nicotinovorans pAO1 involved in nicotine degradation, showing the physical and genetic map of the nic gene cluster. Genes encoding known enzymes of nicotine degradation are shaded dark gray and are indicated by the corresponding abbreviation. ORFs proposed to encode proteins involved in nicotine degradation are shaded light gray, ORFs encoding hypothetical transcription factors are indicated in black, and ORFs with no similarity to known ORFs in data banks are unshaded. Gaps between gene subclusters are indicated in base pairs (bp) above the schematically drawn ORFs. Tn, transposase.

The features of additional ORFs of the gene cluster are presented in Table 2. ORF96 (ΔTn) is without a start methionine and encodes a hypothetical protein with a Mr of 12,838 with similarity to the carboxy-terminal half of a Mycobacterium intracellulare transposase. If it were the second ORF of a transposase with a −1 translational frameshift, one would expect a preceding ORF also with similarity to transposases. However, none of the preceding ORFs show similarity to transposases. The gene cluster is presented as a unit because it may have been generated by a transposition event. Because it contains genes known or supposed to encode enzymes of nicotine degradation, it was designated the nic gene cluster. Other gene products of the cluster, however, are of unknown function and may not be directly related to nicotine degradation.

TABLE 2.

Features associated with ORFs of the nic gene cluster

| Designationa | Basis of comparison | % Similarity/% identity to published sequence (accession no.) in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces | Mycobacterium | Other genus | ||

| ORF124 | Secreted hypothetical protein | 80/39 in 112 aa (Q9KXP7) | ||

| ORF78 | Secreted hypothetical protein | 61/35 in 70 aa (Q9KXP8) | ||

| ORF64 | None | |||

| ORF103 | None | |||

| ORF393 | Putative regulatory protein | 67/37 in 100 aa (Q9XAJ6) | 63/37 in 99 aa (Q06829) | |

| ORF407 | LuxR-type activator | 64/37 in 124 aa (Q9XAJ6) | 60/28 in 261 aa (Q50018) | |

| ORF116 | Hypothetical protein | 61/28 in 99 aa (Q9KZG3) | ||

| ORF367 | Rapamycin resistance | 60/31 in 207 aa (Q54287) | ||

| ORF106 | Putative hydrolase | 74/53 in 19 aa (Q9RK75) | ||

| ORF310 | Polyketide cyclase | 64/31 in 85 aa (Q9RN54) | ||

| ORF235 | CoxG | 78/40 in 151 aa (O53704) | 65/23 in 138 aa b (Q9KX24) | |

| ORF294 | C-N hydrolase | 70/43 in 221 aa (Q9XA70) | ||

| ORF297 | MoxR | 76/47 in 278 aa (O53705) | 82/50 in 273 aac (Q9RWP5) | |

| ORF363 | CoxE | 66/35 in 216 aa (O53703) | 63/31 in 348 aab (QKX26) | |

| ORF377 | CoxI, CoxF | 77/48 in 168 aa (Q9ZBN5) | 76/54 in 155 aa (O53711) | 45/29 in 98 aab (Q9KX25) 53/32 in 94 aab (Q9KX22) |

| ORF117 | None | |||

| ORF204 | MobA | 74/45 in 188 aa (Q9RKU8) | 68/36 in 112 aa (O53706) | |

| ORF70 | None | |||

| ORF223 | None | |||

| ORF96 | Δ Transposase | 66/41 in 53 aa (Q49592) | ||

The locations of the ORFs within the DNA fragment are documented in GenBank, accession no. AF373840. aa, amino acids.

Sequence from Oligotropha carboxidovorans.

Sequence from D. radiodurans.

Of the ORFs with similarity to enzymes of known function, several are of particular interest regarding nicotine degradation. The hypothetical protein with a Mr of 40,994 encoded by ORF367 with highest identity to ORFs of the Streptomyces rapamycin biosynthesis gene clusters (Table 2) shows similarity to members of the endopeptidase enzyme family (Deinococcus radiodurans; accession number Q9RS79). It contains the characteristic amino acid motif L(14X)GXSXGG with the active-site serine. The deduced 33.492-Mr protein of ORF310 shows similarity in the carboxy-terminal half to the amino-terminal half of similarly sized proteins expressed from genes in polyketide cyclase gene clusters of Streptomyces species (SnoAM of S. nogalater [35], ZhuJ of Streptomyces sp. strain R1128 [24], and DpsY of S. peucetius [23]). They all may belong to the family of protein thiol esterases (Prosite accession number PS00639). ORF310 may be translationally coupled to an ORF with a high degree of similarity to salicylate hydroxylase of various sources. As outlined below, the encoded protein represents 2,6-DHPH. ORF294 encodes a hypothetical protein with a Mr of 32,877 and may be identified as a member of the nitrilase or aliphatic amidase family of carbon-nitrogen hydrolases by the exactly matched consensus amino acid sequence G(2X)TCYDLXFP(9X)G of this family (4). ORF204 (MobA; Table 2) encodes a protein with a Mr of 21,536.6 with high similarity to glucose-1-phosphate citidylyl-, thymidylyl-, and uridylyltransferases, in addition to the molybdopterin-guanine dinucleotide biosynthesis protein MobA of E. coli (accession number P32173). Since this ORF shows similarity to pyrimidine transferases, we propose it to represent the MobA enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of the molybdopterin-cytosine dinucleotide cofactor of NDH and KDH.

Cloning, purification, and characterization of 2,6-DHPH.

The ORF encoding the putative 2,6-DHPH showed various degrees of similarity to salicylate hydroxylases of many organisms. The gene containing this ORF was cloned on pH6EX3 (2) and transformed and expressed in E. coli XL-1 blue. The specific activity of the His6-tagged protein in lysates of E. coli XL-1 blue did not differ from the specific activity of the enzyme expressed from the gene cloned into pBlueScript (Stratagene) under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside-inducible lac promoter. Therefore, we analyzed 2,6-DHPH in its His6-tagged form, which was easily purified to homogeneity (results not shown). The enzyme migrated as a homodimer of approximately 90 kDa on gel filtration chromatography, in accordance with the findings of Holmes and Rittenberg (19), which were obtained with a partially purified enzyme preparation. 2,6-DHPH activity could be recorded, as expected, either as a decrease in absorption at 334 nm due to the consumption of NADH or as an increase in absorption at 578 nm due to formation of the blue pigment generated from 2,3,6-trihydroxypyridine, the product of the 2,6-DHPH reaction. The reaction was strictly NADH dependent and did not proceed with NADPH. The purified protein gave a typical flavoprotein absorption spectrum (data not shown) and contained 2 mol of FAD per 1 mol of dimer. The FAD was tightly bound to the protein, since dialysis against 1.5 M KBr did not remove the cofactor. Dialysis against 1.5 M guanidinium hydrochloride removed the FAD, but the apoenzyme could no longer be reconstituted to the holoenzyme. It was, however, possible to prepare apoenzyme by precipitation with 50% (NH4)2SO4 at pH 2.0 (21). The apoenzyme preparation showed 40% of the activity of the holoenzyme. Incubation of the apoenzyme with 100 μM FAD recovered 90% of the initial holoenzyme activity. Reconstitution of holoenzyme from apoenzyme and various flavins identified the cofactor as FAD, and apparent Kd values of 3 × 10−7 M for FAD and 2 × 10−5 M for NADH were determined. The purified enzyme had a specific activity of 90 U/mg at the pH optimum of 8.0 and at the temperature optimum of 20°C. Under these conditions, the enzyme showed a Km of 8.3 × 10−6 M, a Vmax of 4.7 × 10−5 mol/min, and a kcat of 3.9 × 10−6 s−1. In contrast to what was observed by Holmes and Rittenberg (19) with a partially purified enzyme preparation, the purified enzyme was stable at 4°C and no rapid inactivation at 30°C was observed. The enzyme was inactivated at 52°C. Table 1 summarizes the enzyme activities obtained with substrate analogs. Only the pyridine ring hydroxylated in positions 2 and 6 served as a substrate. 2,3-Dihydroxypyridine and 2,6-dimethoxypyridine acted as irreversible inhibitors.

DISCUSSION

The deduced protein sequences of the ORFs of the gene cluster of pAO1 of A. nicotinovorans show a significant degree of similarity to known or hypothetical proteins of Streptomyces and Mycobacterium species. This finding may reflect the general relatedness of the genus Arthrobacter with Streptomyces and Mycobacterium. It may, however, also reflect gene transfer by catabolic plasmids, like pAO1, between species of these genera of soil bacteria. A gene cluster structured similarly to the nic gene cluster on pAO1 may be found on the Mycobacterium tuberculosis chromosome. It consists of the ORFs Rv0374c, Rv0375c, and Rv0373c, encoding the large, small, and medium-sized subunits, respectively, of a hypothetical molybdenum enzyme, and the ORFs Rv0368c, Rv0369c, Rv0370c, Rv0371c, and Rv0376c (6) with similarity to the pAO1 ORF368, ORF235, ORF363, MobA, and ORF377 (Table 2). The IS1473 element at one end of the gene cluster and the transposase-similar ORF on the other end of the gene cluster make a transposition event in the origin of the gene cluster on pAO1 likely.

The known and the deduced enzymatic functions of the predicted products of the ORFs of the nic gene cluster may be correlated to individual steps in nicotine degradation. The first two hydroxylations of the pyridine ring of nicotine in positions 6 and 2 (Fig. 1, steps I and III) are performed by the related, heterotrimeric, FAD-, [Fe-S] cluster-, and MoCo-dependent enzymes NDH and KDH. Oxidation of the pyrrolidine ring is performed by 6HLNO (Fig. 1, step II). A. nicotinovorans extracts prepared from bacteria grown on d,l-nicotine contain 6-hydroxy-d-nicotine oxidase activity (9). The gene of this enzyme is not part of the gene cluster described here, but it was located on pAO1, 15,738 bp downstream from the IS1473 (G. L. Igloi and R. Brandsch, unpublished results). Since d-nicotine is not synthesized by the plant, the natural substrate of 6-hydroxy-d-nicotine oxidase remains speculative. Cleavage of the side chain of 2,6-dihydroxypseudooxynicotine (Fig. 1, step IV) may be performed by the products of ORF106 and ORF310 preceding the ORF for 2,6-DHPH, with which they may form a translational unit (Fig. 2). γ-Methylaminobutyrate and 2,6-dihydroxypyridine were identified as the products of this reaction (15, 20). Gherna et al. (15) formulated the reaction as a hydrolysis and pointed out that, although the biochemical hydrolytic replacement of the side chain of an aromatic ring is unusual, the reaction has precedence in the thiolysis of β-keto-acyl-coenzyme A compounds. The similarity of the hypothetical protein of ORF310 preceding 2,6-DHPH to thiol esterases fits this assumption. The gene encoding 2,6-DHPH, which performs the third hydroxylation of the pyridine ring (Fig. 1, step V), has been identified during this work, cloned, and overexpressed in E. coli. The purified protein was shown to be 2,6-DHPH. We propose that ring opening of 2,3,6-trihydroxypyridine is performed by the hypothetical protein, similar to endopeptidases (Table 2, ORF367) at the peptide bond of the hydroxylated pyridine ring in its amide resonance form (Fig. 1). Ring opening was proposed to be performed by a dioxygenase, in analogy to 2,5-dihydroxypyridine ring opening by 2,5-dihydroxypyridine oxygenase in the degradation of nicotinic acid (14). However, no ORF encoding a putative dioxygenase was identified in this pAO1 gene cluster. It cannot be excluded that such a dioxygenase is encoded on pAO1, but from the organization of the gene cluster we would expect such a gene to be part of the cluster. The hypothetical nitrilase would then remove the amino group from the linearized compound and the carbon skeleton would enter the general metabolism.

The identification of the kdh gene for the large subunit revealed that it forms a separate transcriptional unit from the kdhM and kdhS genes. To our knowledge, this is the first instance that such a gene arrangement has been found for a bacterial trimeric molybdoenzyme. This finding raises the question of how the coordinated expression of the KDH subunits is regulated. This regulation appears to be complex, given the fact that two divergently transcribed putative transcriptional regulators are positioned within the cluster of genes related to enzymes of nicotine degradation. None of these regulators shows similarity to the molybdenum-dependent transcriptional regulator ModE of E. coli (25, 32), although expression of ndh was shown to be molybdenum dependent (16).

The hypothetical MobA protein for the molybdopterin cytidine dinucleotide cofactor is encoded by an ORF which may form a transcriptional unit with ORFs of no known functions but that are presumed to be involved in the assembly of the MoCo holoenzymes, attachment of the enzymes to the cell membrane, and interaction with the respiratory chain (18, 28). MobA could deliver, in the context of these proteins, the molybdopterin cytidine dinucleotide cofactor efficiently to the membrane-associated KDH and NDH apoenzymes (16).

2,6-DHPH is specific for the heterocyclic aromatic compound 2,6-dihydroxypyridine. 3-Hydroxyphenol (resorcine) was not a substrate. In addition, the substrate must be hydroxylated in positions 2 and 6. 2,3-Dihydroxypyridine was not accepted as substrate and acted, as did 2,6-dimethoxypyridine, as an irreversible inhibitor. The monohydroxylated compound 2-hydroxypyridine was found to be a reversible inhibitor of the reaction. Thus, the enzyme showed a narrow substrate specificity. Flavoprotein hydroxylases belong to an enzyme family characterized by three amino acid fingerprint motifs involved in FAD and NAD(P)H binding (11, 12). 2,6-DHPH clearly belongs to the family of flavoprotein hydroxylases. However, some remarkable differences are also evident. The fingerprint motif GXGXXG of FAD- and NAD-dependent enzymes is altered to GXSXXG. In the second characteristic motif of this family, DXXXGXDGXK, which is involved in both FAD and NAD(P)H binding, two charged residues are replaced by uncharged polar (D→N) or uncharged hydrophobic (K→A) residues. It has been shown by chemical modification that the K in salicylate hydroxylase is important for NADH binding (34), and similar results were obtained with mutants of parahydroxybenzoate hydroxylase (13). In the third fingerprint motif of this family GDAAH, the H residue is replaced in 2,6-DHPH by V. Despite these alterations in residues shown to be important for cofactor binding, FAD is nevertheless tightly bound by the enzyme. There are several FAD-dependent hydroxylases known, with a loosely bound flavin cofactor, like 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase (33). However, this enzyme shows the same conserved amino acid sequences as those with tightly bound FAD (11, 12). Apparently, additional amino acid residues other than those of the deduced fingerprint motifs may stabilize the interaction of the apoenzymes with FAD in some enzymes of this family.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Schiefermayr and I. Deuchler for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, GRK 434, to R.B. and, in part, by SFB 388 to G.L.I.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gisg W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthold H, Scanarini M, Abney C C, Frorath B, Northemann W. Purification of recombinant antigenic epitopes on the human 68-kDa (U1) ribonucleoprotein antigen using the expression system pH6EX3 followed by metal chelating affinity chromatography. Protein Expr Purif. 1992;3:50–56. doi: 10.1016/1046-5928(92)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonfield J K, Smith K F, Staden R. A new DNA sequence assembly program. Nucleic Acids Res. 1965;23:4992–4999. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.4992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bork P, Koonin E V. A new family of carbon-nitrogen hydrolases. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1344–1346. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandsch R, Decker K. Isolation and partial characterization of plasmid DNA from Arthrobacter oxydans. Arch Microbiol. 1984;138:15–17. doi: 10.1007/BF00425400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai V D, Decker K, Sund H. Purification and properties of l-6-hydroxynicotine oxidase. Eur J Biochem. 1968;4:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decker K, Gries F A, Brühmüller M. Über den Abbau des Nikotins durch Bakterienenzyme. III. Stoffwechselstudien an Zellfreien Extrakten. Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem. 1961;323:249–263. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1961.323.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decker K, Bleeg H. Induction and purification of stereospecific nicotine oxidizing enzymes from Arthrobacter oxydans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965;105:313–334. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6593(65)80155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberwein H, Gries F A, Decker K. Über den Abbau des Nikotins durch Bakterienenzyme. II. Isolierung und Charakterisierung eines Nikotinabbauenden Bodenbakteriums. Hoppe-Seyler's Z Physiol Chem. 1961;323:236–248. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1961.323.1.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eppink M H M, Schreuder A H, van Berkel W J H. Identification of a novel conserved sequence motif in flavoprotein hydroxylases with a putative dual function in FAD/NAD(P)H binding. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2454–2458. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eppink M H M, Boeren S A, Vervoort J, van Berkel W J H. Purification and properties of 4-hydroxybenzoate 1-hydroxylase (decarboxylating), a novel flavin adenine dinucleotide-dependent monooxygenase from Candida parapsilosis CBS604. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6680–6687. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6680-6687.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eppink M H M, Bunthof C, Schreuder H A, van Berkel W J H. Phe161 and Arg166 variants of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase implications for NADPH recognition and structural stability. FEBS Lett. 1999;443:251–255. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01726-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gauthier J J, Rittenberg S C. The metabolism of nicotinic acid. I. Purification and properties of 2,5-dihydroxypyridine oxygenase from Pseudomonas putida N-9. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:3737–3742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gherna R L, Richardson S H, Rittenberg S C. The bacterial oxidation of nicotine. VI. The metabolism of 2,6-dihydroxypseudooxynicotine. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:3669–3674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grether-Beck S, Igloi G L, Pust S, Schiltz E K, Brandsch R. Structural analysis and molybdenum-dependent expression of the pAO1-encoded nicotine dehydrogenase genes of Arthrobacter nicotinovorans. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:929–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamm H-H, Decker K. Regulation of flavoprotein synthesis in vivo in a riboflavin-requiring mutant of Arthrobacter oxidans. Arch Microbiol. 1978;119:65–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00407929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hänzelmann P, Meyer O. Effect of molybdate and tungstate on the biosynthesis of CO dehydrogenase and the molybdopterin cytosine-dinucleotide-type of molybdenum cofactor in Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava. Eur J Biochem. 1998;255:755–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes P E, Rittenberg S C. The bacterial oxidation of nicotine. VII. Partial purification and properties of 2,6-dihydoxypyridine oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:7622–7627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes P E, Rittenberg S C. The bacterial oxidation of nicotine. VIII. Synthesis of 2,3,6-trihydroxypyridine and accumulation and partial characterization of the product of 2,6-dihydoxypyridine oxidation. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:7628–7633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husain M, Massey V. Reversible resolution and reconstitution of flavoproteins into apoproteins and free flavin. Methods Enzymol. 1978;53:429–437. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)53047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kodama Y, Yamamoto H, Amano N, Amachi T. Reclassification of two strains of Arthrobacter oxydans and proposal of Arthrobacter nicotinovorans sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:234–239. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomovskaya N, Doi-Katayama Y, Filippini S, Nastro C, Fonstain L, Gallo M, Colombo A L, Hutchinson C R. The Streptomyces peucetius dpsY and dnrX genes govern early and late steps of daunorubomycin and doxorubicin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2379–2386. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2379-2386.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marti T, Hu Z, Pohl N L, Shah A N, Khosla C. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and heterologous expression of the biosynthetic gene cluster for R1128, a non-steroidal estrogen receptor antagonist. Insights into an unusual priming mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33443–33448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNicholas P M, Mazotta M M, Reich S A, Gunsalus R P. Functional dissection of the molybdate-responsive transcription regulator, ModE, from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4638–4643. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4638-4643.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menéndez C, Igloi G L, Brandsch R. IS1473, a putative insertion sequence identified in the plasmid pAO1 from Arthrobacter nicotinovorans: isolation, characterization and distribution among Arthrobacter species. Plasmid. 1997;37:35–41. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menéndez C, Otto A, Igloi G L, Nick P, Brandsch R J, Schubach B, Böttcher B, Brandsch R K. Molybdate-uptake genes and molybdopterin-biosynthesis genes on a bacterial plasmid. Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:524–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0524a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santiago B, Schübel U, Egelseer C, Meyer O. Sequence analysis, characterization and CO-specific transcription of the cox gene cluster on the megaplasmid pHCG3 of Oligotropha carboxidovorans. Gene. 1999;236:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schelling U. Ph.D. dissertation. Freiburg, Germany: Albert Ludwig University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schenk S, Hoelz A, Kraus B, Decker K. Gene structure and properties of enzymes of the plasmid-encoded nicotine catabolism of Arthrobacter nicotinovorans. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1323–1339. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schenk S, Decker K. Horizontal gene transfer involved in the convergent evolution of the plasmid-encoded enantioselective 6-hydroxynicotine oxidases. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:178–186. doi: 10.1007/pl00006456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Self W T, Grunden A M, Hasona A, Shanmugam K T. Transcriptional regulation of molybdoenzyme synthesis in Escherichia coli in response to molybdenum: ModE-molybdate, a repressor of the modABCD (molybdate transport) operon is a secondary transcriptional activator for the hyc and nar operons. Microbiology. 1999;145:41–55. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siebold B, Matthes M, Eppink M H M, Lingens F, van Berkel W J H, Müller R. 4-Hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase from Pseudomonas sp. CBS3. Purification, characterization, gene cloning, sequence analysis and assignment of structural features determining the coenzyme specificity. Eur J Biochem. 1996;239:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0469u.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki K, Asao E, Nakamura Y, Ohnishi K, Fukuda S. Overexpression of salicylate hydroxylase and the crucial role of lys(163) as its NADH binding site. J Biochem. 2000;128:293–299. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torkkell S, Ylihonko K, Hakala J, Skurnik M, Mantsala P. Characterization of Streptomyces nogalater genes encoding enzymes involved in glycosylation steps in nogalamycin biosynthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;256:203–209. doi: 10.1007/s004380050562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]