Summary

Objective

To synthesize peer‐reviewed literature that utilize co‐creation principles in healthy food retail initiatives.

Methods

Systematic review of six databases from inception to September 2021. Screening and quality assessment were carried out by two authors independently. Studies were included if they were conducted in food retail stores, used a collaborative model, and aimed to improve the healthiness of the food retail environment. Studies excluded were implemented in restaurants, fast food chains, or similar or did not utilize some form of collaboration. Extracted data included the type of stakeholders engaged, level of engagement, stakeholder motivation, and barriers and enablers of the co‐creation process.

Findings

After screening 6951 articles by title and abstract, 131 by full text, 23 manuscripts that describe 20 separate studies from six countries were included. Six were implemented in low‐income communities and eight among Indigenous people groups. A common aim was to increase access to, and availability of, healthy products. A diverse range of co‐creation approaches, theoretical perspectives, and study designs were observed. The three most common stakeholders involved were researchers, corporate representatives or store owners, and governments.

Conclusions

Some evidence exists of the benefits of co‐creation to improve the healthiness of food retail environments. The field may benefit from structured guidance on the theory and practice of co‐creation.

Keywords: co‐creation, food outlets, food retail environments, participatory research

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization's (WHO) target to halt the global rise in diabetes, overweight, and obesity in adolescents and adults by 2020 1 was not achieved and so was extended to 2030. 2 Progress toward these targets is being hampered by the complex interplay of individual, environmental, and societal factors that drive overweight and obesity 3 ; and the food environment represents key drivers. Food environments can be conceived as complex systems, comprising dynamic interrelations between retail sources, retail actors, and business models influencing what, where, how, and when food is consumed or purchased. 4 , 5 Actively addressing food environments 6 , 7 to create opportunities to achieve healthy, accessible, and affordable diets represents a critical field in population health. 8 Food environment interventions to date have focused toward food reformulation, taxes on sugary drinks and health‐oriented food labeling on packaged foods. 9 , 10 Globally, more than half of foods are purchased from supermarkets and grocery stores (e.g., in Europe 70%–80%, 11 in the United States 74%, 12 and in Australia 66% 13 ), which highlights their influence on food provision 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 and makes them strategic settings for health‐enabling initiatives. 4 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21

There is evidence to suggest multifaceted interventions within supermarket and grocery stores can improve the nutritional quality of food purchases, improving population health. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 These interventions typically seek to improve dietary behavior at the point of choice in food stores 25 , 26 , 27 though are not always sustainable over the long term. 25 , 26 , 28 Key factors underpinning the success of healthy food outlet initiatives include the interplay of store owners and managers, 22 , 28 consumers, 22 and the support of retailers in the implementation. 28 Though landmark statements like the UN's Sustainable Development Goals 29 set out principles of multisectoral action to maximize prevention, little less is known about best practices in achieving collaboration between multiple stakeholders for designing, implementing, and measuring health‐enabling initiatives in supermarkets and grocery stores. Co‐creation may provide a means to understand and optimize these initiatives as it is participatory, collaborative, context‐sensitive, and knowledge‐based practice, 30 , 31 where actors collaborate with different kinds of knowledge, resources, and competencies to solve a shared problem. 32

1.1. Co‐creation

Co‐creation, co‐design, and co‐production have been used interchangeably to describe initiative development involving multiple stakeholders. 31 Each of these terms has emerged from different fields and holds nuance in meaning and application depending on the area in which the concept is applied. 30 Co‐creation can be considered an overarching guiding principle encompassing co‐design and co‐production, as co‐creation engages stakeholders in the co‐design and co‐production processes. 33 , 34 , 35 Co‐creation represents an approach that allows stakeholders to interact and find shared values 33 , 36 to create change. 31 , 34 It has been described as a participatory method for collaborative design of initiatives between academic and nonacademic stakeholders. 37 In this paper, we define co‐creation as “the collaborative approach of creative problem solving between diverse stakeholders at all stages of an initiative, from the problem identification and solution generation through to implementation and evaluation.” 38 Co‐creation has shown positive influences in education, 39 , 40 interorganizational cooperation, 41 creativity studies, 34 , 42 planning and development studies, 43 community‐based research, 31 , 44 sustainability of healthcare services 31 , 45 and health promotion. 30 The power of co‐creation includes the flexibility to adapt interventions to context including shared visions, plans, policies, initiatives, and regulatory frameworks. 45 , 46

For the food retail setting, co‐creation provides a way to systematically understand the collaboration between diverse stakeholders to improve the healthiness of food retail environments. Some studies report parallel benefits of collaboration between diverse stakeholders (i.e., suppliers, retailers, community, and government) with co‐created and tailored interventions that target specific participants and settings. 37 , 47 Yet discussion continues about who should be involved, when, and what role should be played by stakeholders in the co‐creation process. 48 Because supermarkets and grocery stores have diverse business models, mostly driven by profit and providing a service, 4 stakeholders could be anyone concerned with improving the healthiness of the food retail outlet. Identifying the type of stakeholders that are concerned to make healthy changes, their motivations and level of involvement is central to finding new shared solutions and opportunities for mutual benefit, which translate into the creation of value and could help to improve the sustainability of initiatives.

This study systematically reviewed the peer‐reviewed literature on the design, implementation, and barriers and enablers of co‐created initiatives to improve the healthiness of food retail outlets. It provides a focus on the roles of stakeholders in healthy food retail co‐creation research and their involvement and motivation for conducting or participating in a co‐created process. The review set out to answer the following research questions:

Which stakeholders are engaged in healthy food retail co‐creation research?

How do stakeholders understand and participate in the healthy food retail co‐creation research?

What are the motivations of stakeholders to engage in healthy food retail co‐creation research?

What are the identified enablers and barriers in healthy food retail‐co‐creation research?

2. METHODS

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 49 and registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021226566; January 16, 2021). The current review deviates from the registered protocol by extending the study search to include all languages (not restricted to English and Spanish).

2.1. Search strategy

Searches were conducted in (MEDLINE complete [Ebsco Host], Global Health [Ebsco Host], CINAHL [Ebsco Host], Scopus [Elsevier], and Embase [Elsevier]). The strategy was developed between authors and a research librarian trained in conducting systematic reviews. The strategy was informed by previous systematic reviews that examined the food retail environment 23 , 28 , 50 and principles of co‐creation 44 , 51 (Table 1). The search strategy was adapted to each database for original research involving human participants and published from inception of each database to the 21st of September 2021. An additional hand search was undertaken of reference lists from included studies.

TABLE 1.

Terms included in the search strategy

| String 1 | co‐creat* OR cocreat* OR co‐design* OR codesign OR co‐produc* OR coproduc* OR co‐develop* OR codevelop* OR co‐implement* OR coimplement* OR “participat* research” OR “action research” OR “community participation” OR collaborat* OR “shared decision making” OR engagement OR “participatory co‐creation” OR “participatory co‐design” OR “stakeholder‐led research” OR “community‐led research” | Title and abstract |

| AND | ||

| String 2 | “food retail environment” OR “consumer food environment” OR “food retail” OR “food environment” OR store OR supermarket OR “food outlet*” OR “food market” OR “food store” OR “food shop” OR “convenience store” OR “grocer* store” OR “corner store” OR “community store” OR grocer* OR in‐store | Title and abstract |

2.2. Study selection

Studies were included if they (1) were carried out in food stores (comprising supermarkets, community food stores, and convenience stores) and (2) included the use of a collaborative model (e.g., co‐creation, co‐design, co‐production, or participatory research). Because there is a long history of collaborative initiatives and problem‐solving methods that are not referred as co‐creation, 34 studies were included where collaboration of at least two stakeholders occurred in each reported step of the initiative development. (3) Studies were included where the initiative was not predetermined, for example, where the manuscript described the process of the development of the initiative, and (4) have an underlying aim of modifying the healthiness of the food store environment (e.g., sales, purchases, or availability of core [healthy] foods or discretionary [less healthy] foods). Studies were excluded if they (1) did not present primary data, for example, reviews, book chapters, expert opinions, conference reports, unpublished studies, or protocols, or (2) were interventions implemented in food outlets where most of the food is preprepared or ready to eat (e.g., within a school, workplace, hospital setting, fast food chain, café, or restaurant). Google Translate 52 was used to review papers in other languages.

2.3. Data extraction

Search results were imported to Endnote X9 53 where duplicates were removed, and the remaining citations imported into COVIDENCE 54 for screening, data extraction, and quality assessment. Two researchers independently screened titles and abstracts and full text. All conflicts at the titles and abstracts stage were resolved by a third researcher. A data extraction schema was developed in consultation with all authors, based on a combination of commonly reported information from previous systematic reviews 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 and empirical material focusing on principles of co‐creation (Table 2). 55 Where conflicts arose at full‐text extraction, discussions were held between researchers involved in the data extraction until agreement was reached.

TABLE 2.

Extraction schema

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Description of the studies | Author's name, year, country, study design, main aim, program/project name, duration of the study, setting description, and participant food stores |

| Principles that informed co‐creation | Theory, approach, or framework used to support the study design |

| Conception of “healthiness” of the food retail | Study's definition/strategies for the food retail healthiness (e.g., increase availability, prominent placement of healthier products, or a combination of variables) |

| Type of stakeholders | Stakeholders mentioned throughout the publication (e.g., research team, retailers, corporate owners, managers, etc.) |

| Reflection on the co‐creation process | Description of the benefits or barriers to use co‐creation to improve the healthiness of the food retail and its impact on the study outcomes |

| Reflection for future use of co‐creation | Recommendations for future application of co‐creation |

| Motivations to participate in a co‐created initiative |

Motivations for those participating in the study (e.g., intrinsic or extrinsic) Roberts et al's 55 typology was used to classify these motivations. This typology positions individual motivations to co‐create across three types of co‐creation efforts: (1) motivations to innovate, driven by intrinsic motives; (2) motivations to contribute to community innovation activities, driven by altruistic motives; and (3) motivations to collaborate directly with organizations, driven by opportunity or goal‐related motives |

| Motivations of researchers for the use of co‐creation | Clear statement on the underpinning motivation for the study (e.g., testing new strategy, contribute to knowledge) |

| Level of participation of stakeholders engaged in the study |

Time of participation from stakeholders throughout the co‐creation process (initiation, identification [consultation], definition, design, realization, and evaluation) 56 Level of participation was classified and interpreted using the following ranking adopted from service delivery and public administration engagement 57 , 58 : (1) passive, stakeholders considered just to implement or evaluate the study (2) active, consideration of the stakeholder input in the design, and realization of the study (3) very active, multiple interactions throughout the study |

2.4. Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed by two independent researchers using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), a validated tool for quality assessment in systematic reviews of mixed study designs. 56 The tool appraises the methodological quality of five designs: qualitative research, randomized control trials, quantitative non‐randomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed methods studies. After two screening questions, eligible studies were scored against five questions about study design quality as “yes” (scored 1) or “no” (scored 0). In accordance with the MMAT reporting guidelines, 57 mixed methods studies were scored in the same way on a 15 ‐question scale, and this is standardized to score out of 5 to make it comparable within the MMAT. Each study could achieve one of six score categories based on score and (% available score): 5 (100%), 4 (80%), 3 (60%), 2 (40%), 1 (20%), or 0 (0%). Conflicts were resolved by discussion between the two researchers.

2.5. Data synthesis

The narrative and tabular synthesis of the results comprised two steps. First, data were coded based on the attributes listed in Table 2. Subsequently, stakeholders were grouped by type and their level of engagement according to the study's description. We interpreted the studies from our understanding and construction of co‐creation, drawn from a combination of service management, marketing, and public administration, adapted to public health initiatives in supermarkets and grocery stores. To our knowledge, there are no preexisting co‐creation frameworks applicable to these food retail environments. Our perspective on co‐creation considers that stakeholder involvement goes beyond the occasional participation or consultation. Stakeholder engagement is essential for the relevant design of solutions that promote incremental change and transformative innovation and suit the context of the involved parties. In this view, the co‐creation approach is sought as continuum that brings multiple stakeholders together through the research process. 38

3. RESULTS

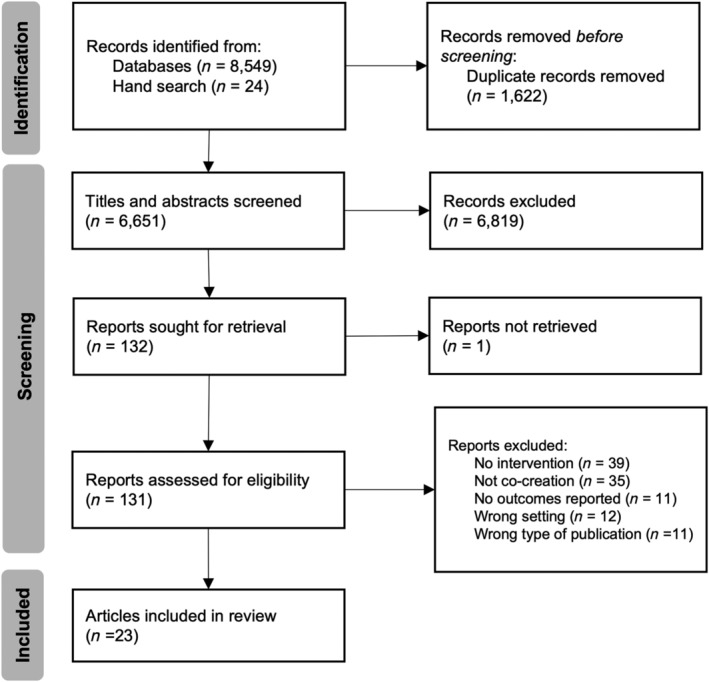

The initial search returned 8549 results, and a further 24 papers were identified from hand searching references of these initial papers. Of these, 6819 records were excluded based on title and abstract; and a further 108 were excluded based on full‐text screening (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA diagram of the systematic review process for this review

3.1. Description of included studies

The 23 papers included comprised 20 separate studies, see Appendix 1 (Table S1) for a general description of included articles. Three of the articles were published between 1980 and 2000, 58 , 59 , 60 seven were published between 2010 and 2015, 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 and the majority were between 2016 and 2021 (n = 13). 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 Among the 23 included papers, Healthy Foods North (HFN), 61 , 62 Healthy Foods Hawaii (HFH), 63 , 64 and the Tribal Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments (THRIVE) 73 , 74 were reported in multiple articles. Around half of the studies (n = 11) 59 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 80 were conducted in the United States. The remaining studies were conducted in Australia (n = 4), 72 , 76 , 77 , 79 Canada (n = 2), 58 , 61 , 62 New Zealand (n = 1), 78 Finland (n = 1) 60 and Denmark (n = 1). 71

Eight studies focused on First Nations communities; these represented Australia (n = 3), 72 , 76 , 77 the United States (n = 3), 63 , 64 , 73 , 74 , 75 or Canada (n = 2). 58 , 61 , 62 The rest reported on interventions situated in urban areas (n = 7) 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 78 that targeted communities described as low income or living with poverty. 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 Four studies did not describe the target population. 59 , 60 , 71 , 79 Interventions were carried out in supermarkets (n = 6), 59 , 60 , 68 , 71 , 78 , 79 corner stores (n = 5), 65 , 66 , 67 , 70 , 75 food stores (n = 3), 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 72 community stores (n = 3), 58 , 76 , 77 and convenience stores (n = 2). 69 , 73 , 74

Studies typically focused on one component (n = 13), 58 , 59 , 60 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 71 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 to improve the healthiness of food retail outlets, such as improving the availability of healthy products (n = 6), 63 , 64 , 67 , 71 , 75 , 76 , 77 educating consumers on healthy options (n = 3), 58 , 59 , 60 increasing access to healthy food (n = 2), 65 , 69 or changes to healthy product placement (n = 2). 68 , 78 Some studies considered a combination of two (n = 3) 61 , 62 , 66 , 70 , 80 or three (n = 2) 72 , 73 , 74 components; one study conceived the healthiness of food retail outlets in five components (availability, education, socialization, marketing, and policy). 79

3.2. Quality assessment

After answering “yes” to the two screening questions, the methodological quality of included papers score ranged from 40% (n = 3, 13%), 58 , 59 , 60 60% (n = 6, 26%), 66 , 67 , 68 , 70 , 80 and 80% (n = 9, 39%), 61 , 63 , 68 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 and five papers (22%) 62 , 64 , 70 , 77 , 78 met 100% of the quality criteria. See Appendix 1 (Table S2) for individual study quality scores.

3.3. Methodological characteristics of included co‐creation studies

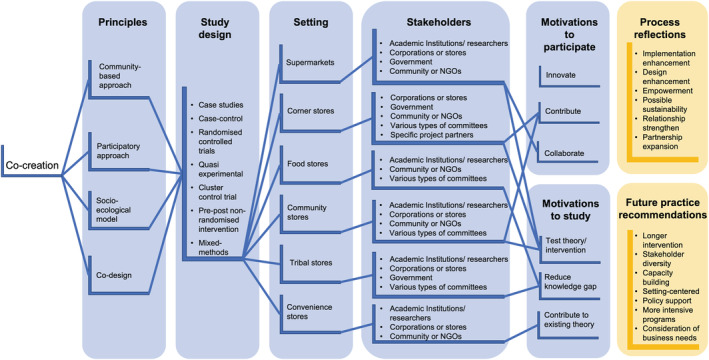

Study designs included case studies (n = 8), 58 , 60 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 72 , 75 , 79 case–control studies (n = 8), 59 , 61 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 71 , 76 , 78 randomized controlled trials (n = 3), 70 , 73 , 77 and one quasi‐experimental study, 62 one cluster control trial, 74 one pre‐post non‐randomized intervention 65 and one mixed methods study (Table 3). 80 Diverse principles, theories, models, and approaches informed the use of co‐creation (Figure 2). Community‐based participatory approaches (n = 7) 62 , 63 , 66 , 70 , 75 , 76 , 80 were the most prominent, followed by diverse forms of participatory methods (n = 4), 64 , 65 , 69 , 72 socioecological models (n = 2), 67 , 68 and co‐design (n = 2). 78 , 79 Four studies combined approaches, being (1) behavioral and environmental initiatives through community‐based activities 61 ; (2) community‐based participatory research principles in the study design 73 and socio‐cognitive theory in the results reporting 74 ; (3) socioecological theory and co‐design 77 ; and (4) ecological and participatory approach. 71 Three studies did not provide explicit theoretical frameworks, two of these were conducted in a supermarket setting, 59 , 60 and one was conducted with Inuit and Native Canadian. 58

TABLE 3.

Summary characteristic of included studies

| Author, year of publication, and country | Principles that informed co‐creation | Conception of healthiness | Stakeholder group | Stakeholders' type | Time of participation of stakeholders | Level of participation 56 | Motivations | Reflection of the co‐creation process | Recommendations for future use of co‐creation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Identification | Definition | Design | Realization | Evaluation | Passive | Active | Very active | Stakeholder 55 | Researcher | |||||||

|

Schurman et al (1983) Canada 61 |

Framework of stages and objectives direct the program | Education | Corporation/stores | Hudson's Bay Company | ✔ | Contribute | NR | Enhance implementation | NR | ||||||||

| HBC Nutritionist | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Store staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Government officials | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Professional health workers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Schools | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Community | Community members | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Provincial or national agencies and organizations | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

|

Light et al (1989) United States 62 |

Previously successful collaborative experiences and on the experience of other researchers who have conducted point‐of‐purchase studies | Education | Academic inst./researchers | National Cancer Institute (NCI) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | NR | Enhance implementation | NR | |||

| Corporation/stores | Giant Food Inc. (regional supermarket chain) | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Technical consultant | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Writer editor | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Advisory/steering panels/groups/committees | NCI review group (program staff and office of cancer communications) | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Consumer Advisory Board (Established by GF) | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| External Advisory Group (federal government agencies, academia, the food industry, and consumer groups) | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

|

Nörhinen et al (1999) 63 Finland |

Education | Academic inst./researchers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Test theory |

Retailer empowerment Expand partnerships |

NR | |||||||

| Corporation/stores | Store managers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Government | Municipal food control | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Community | Store customers | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Adjoian et al (2017) 71 United States |

Socioecological model | Placement | Academic inst./researchers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Test theory | NR | Capacity building | |||||

| Corporation/stores | Supermarket managers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

|

Gittelsohn et al (2010) 64 Canada |

Combination of behavioral and environmental strategies through community‐based activities |

Availability Promotion |

Academic inst./researchers | Inuit and non‐Inuit project staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Reduce knowledge gap |

Cultural appropriateness Community empowerment |

Setting adaptation | |||||

| Corporation/stores | Store managers and staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

| Government | Health and social service staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Community | Representative of local community organizations: community leaders, community members | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

|

Kolahdooz et al (2014) 65 Canada |

Community participatory research |

Availability Promotion |

Academic inst./researchers | University students | ✔ | NR | NR | NR | Extended stakeholders' diversity | ||||||||

| Corporation/stores | Food stores | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Government | Local community health workers | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Community | Community stakeholders and community | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Community members | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

|

Gittelsohn et al (2010) 66 United States |

Participative process with the community | Availability | Academic inst./researchers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Reduce knowledge gap | NR |

Extended stakeholders' diversity Prolonged time Policy support |

|||||

| Corporation/stores | Producers | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Distributors | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Community | Caregivers and families | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Community | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

|

Novotny et al (2011) 67 United States |

Participatory strategic planning with the Healthy Living in the Pacific Islands Initiative (HLPI) | Availability | Academic inst./researchers | Project staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Test theory |

Enhance implementation Project sustainability |

Setting adaptation | ||||||

| Corporation/stores | Store owners and managers, food distributors, and local food distributors | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Healthy Living in the Pacific Islands Initiative | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Community | Community | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Nonprofit | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Gudzune et al (2015) 68 United States |

Collaborative model | Access | Academic inst./researchers | Study staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Contribute | Test theory | Enhance implementation | Setting adaptation | |||

| Corporation/stores | Store owners | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Farmers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Young et al (2014) 70 United States |

Socioecological approach | Availability | Academic inst./researchers | Ohio State University | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Contribute to existing theory | NR | Setting adaptation | ||||||

| Corporation/stores | Corner stores | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Local F&V distributor | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Government | Municipal health department | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Public health office | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Community | Regional nonprofit | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Nonprofit advocacy group | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Neighborhood community food nonprofit | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Ortega et al (2015) 69 United States |

Community‐engaged approach |

Availability Education |

Academic inst./researchers | Expert corner store operator | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Test theory |

Community empowerment Enhance implementation |

Capacity building Intensive program |

|||||

| University investigators | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Corporation/stores | Store owners | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Produce wholesalers and local farmers markets | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Advisory/steering panels/groups/committees | Community Advisory Board: Community and government | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Scientific Advisory Board: Academics | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Pothukuchi (2016) 72 United States |

Participatory action research methodology | Access | Academic inst./researchers | SEED Wayne | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Contribute | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Project representatives: student employees and volunteers | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Corporation/stores | Store operators | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Wholesale distributors | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Community | Capuchin Soup Kitchen's (CSK) staff and guests | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

|

Thorndike et al (2017) 73 United States |

Community‐based approaches for promoting healthy eating |

Placement Quality |

Academic inst./researchers | Study staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Reduce knowledge gap | NR | Policy support | ||||||

| Produce consultant | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Corporation/stores | Corner store Owners | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Government | Massachusetts state WIC office | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Winkler et al (2016) 74 Denmark |

Ecological and participatory approach (super setting approach) | Availability | Academic inst./researchers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Collaborate | Reduce knowledge gap | Limited control over the intervention | NR | |||||

| Corporation/stores | Store owners and regional sales manager | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Community | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Brimblecombe et al (2017) 75 Australia |

Participatory action learning model for continuous quality improvement |

Availability Affordability Access |

Academic inst./researchers | Research team | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Reduce knowledge gap |

Cultural appropriateness Project sustainability |

Extended stakeholders' diversity Prolonged time Clear roles and responsibilities |

||||

| Community | Community coordinator and members | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| Advisory/steering panels/groups/committees | Good food groups: store board and management, the health service, the school, the aged‐care service, government | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

|

Jernigan et al (2018) 76 United States |

Community‐based participatory research |

Availability Affordability Access |

Academic inst./researchers | University researchers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | NR |

Inform policy work Design multilevel efforts |

Setting adaptation |

|||

| Corporation/stores | Native convenience stores | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Community | Native adults living within the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Advisory/steering panels/groups/committees | Tribal–university partnership: university researchers and tribal health, commerce, and government leaders | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

|

Bird Jernigan et al (2019) 77 United States |

Social cognitive theory |

Availability Affordability Access |

Community | Individuals (ev. process) | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Reduce knowledge gap | Strengthen of cross‐sector relationships | NR | |||||||

| Advisory/steering panels/groups/committees | Tribal–university partnership: university researchers and tribal health, commerce, and government leaders | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Young et al (2018) 78 United States |

Community engaged research | Availability | Corporation/stores | Corner storeowners | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR |

|

|

|

||||||

| Community | Youth and community residents | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Consumers | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Advisory/steering panels/groups/committees | Community‐based liaison | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Infrastructure subcommittee | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Marketing subcommittee | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Distribution subcommittee | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Stakeholder coalition | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

| Project partners | Project partners: Walnut Way Conservation Corp, the Medical College of Wisconsin, and the City of Milwaukee Health Department | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

|

Fehring et al (2019) 79 Australia |

Community‐led action aligned with aligned with key organizational, state, and global health promotion frameworks | Availability | Academic inst./researchers | Project team | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Test theory |

Enhance implementation Cultural appropriateness |

NR | |||

| Corporation/stores | Apunipima staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Government | Aboriginal Shire Councils | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Community | Community members | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Community organizations | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Advisory/steering panels/groups/committees | Community advisory committees | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

|

Young et al (2020) 81 New Zealand |

Co‐design approach | Placement | Academic inst./researchers | Public health nutrition academics | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Test theory |

Project sustainability Strengthen of cross‐sector relationships |

Capacity building | ||||||

| An independent group facilitator | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Corporation/stores | Representatives of health, nutrition, purchasing, and communications | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Store staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Bogomolova et al (2021) 82 Australia |

Design thinking (co‐design) |

Availability Education Policy Marketing Socialization |

Academic inst./researchers | Researchers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Test theory |

Retailer empowerment Enhance implementation Community empowerment |

Intensive program Prolonged time |

||||

| Dietitian | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Design agency | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Corporation/stores | Staff | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| Management | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| Community | Consumers: adult shopping population for the region | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

|

Brimblecombe et al (2020) 80 Australia |

Socioecological theory Co‐design |

Availability | Academic inst./researchers | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Contribute and collaborate | Test theory |

|

NR | |||||

| Corporation/stores | ALPA board of directors | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| ALPA management | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| ALPA store management | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| ALPA nutritionist | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

|

Rollins et al (2021) 83 United States |

Community‐based participatory approach |

Availability Marketing |

Academic inst./researchers | Academic institutions | ✔ | ✔ | NR | Reduce knowledge gap |

|

NR | |||||||

| Corporation/stores | Store owners | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| Community | CCB: Academic institution, residents, and social service agencies | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||

| Community leaders | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||

| Graduate students | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

FIGURE 2.

Summary of included studies outlining relevant principles, design, settings, relevant stakeholders, and motivations, along with reflections and recommendations for future practice

3.4. Type of stakeholders and level of collaboration in the co‐creation process

Six different groups of stakeholders were reported: (1) corporation or store owners (n = 18) 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 80 ; (2) academic Institutions/researchers (n = 18) 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 ; (3) government officers (n = 6) 58 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 67 , 76 ; (4) community or nongovernmental organization representatives (n = 14) 58 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 67 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 79 , 80 (5) members of various types of committees (n = 7) 59 , 66 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 80 ; and (6) specific project partners (n = 1). 75

Each stakeholder group collaborated in different co‐creation stages. Five studies 58 , 69 , 77 , 78 , 80 described the initiation process with members from another stakeholder group such as government officers (n = 4), 58 , 61 , 64 , 67 corporation or store owners (n = 4), 58 , 77 , 78 , 80 or community or nongovernmental organization representatives (n = 2). 69 , 80 Most of the studies reported diverse stakeholder groups participating in the identification, definitions, and design of the initiative in some capacity (e.g., consultation, environmental analysis, and co‐design). Descriptions on the collaboration of corporation or store owners commonly were common in the initiative design (n = 14) 58 , 59 , 61 , 65 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 and realization (n = 18) 58 , 59 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 stages. Academic Institutions/researchers conducted the evaluation of the initiative in collaboration with corporation or store owners (n = 7) 58 , 61 , 65 , 68 , 77 , 78 , 80 when the design required their input (e.g., sales data) and surveys or evaluations directed to the community (n = 10). 60 , 62 , 67 , 68 , 71 , 72 , 74 , 75 , 79 , 80

Participation ranged from passive to active to very active. Each stakeholder group comprised diverse actors (stakeholder type) that collaborated at different stages of the study (Table 3); the level of participation is described by stakeholder group. Participation was ranked depending on the time when a stakeholder group collaborated throughout the co‐creation process (initiation, identification [consultation], definition, design, realization, and evaluation) as described in Table 2. It ranged from passive (i.e., when a group of stakeholders were just considered to implement or evaluate the study) to active (i.e., when the input of a group of stakeholders was considered in the design and realization of the study) and very active (i.e., multiple interactions from a group of stakeholders throughout the study). The studies described academic Institutions/researchers as having a very active role in the study (n = 20); the role of corporations or stores oscillated between active (n = 11) and very active (n = 12); communities were typically very active through membership of various types of committees (n = 7).

3.5. Motivations for conducting or participating in a co‐created process

Of the five studies that described the motivation of participants to engage in co‐creation, these motivations were contributing to community innovation activities (n = 3) 58 , 65 , 69 and collaborating directly with organizations (n = 1). 71 No studies reported innovation as a motivation. A combination of motivations to contribute to community and collaborate with the organizations was identified in one study. 77 Authors' motivations were classified in three categories: (1) test theory/intervention (n = 9) 60 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 68 , 77 , 78 , 79 ; (2) reduce knowledge gap (n = 6) 61 , 63 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 74 , 80 ; and (3) contribute to existing theory (n = 1). 31

3.6. Author reflections on the co‐creation process: Enablers and barriers

Many studies presented author reflections on the co‐creation process and/or study outcomes related to the co‐creation process (n = 17). 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 These related to the enhancement of implementation 58 , 59 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 75 , 76 , 79 or design (e.g., cultural appropriateness), 61 , 72 , 76 empowerment of the community 61 , 66 , 77 , 79 , 80 or retailers, 60 , 79 impacts on project sustainability, 64 , 72 , 78 strength of relationships with community 75 or between sectors, 74 , 77 , 78 and growing partnerships. 60 Recommendations for future use of co‐creation included a prolonged time for the intervention, 63 , 72 , 79 extended stakeholders' diversity, 62 , 63 , 72 , 75 greater capacity building, 66 , 68 , 75 specific conditions of the setting, 63 , 64 , 65 , 67 , 73 policy support, 63 , 70 more intensive programs, 66 , 79 and consideration of business needs. 75 See Appendix 1 (Table S4) for specific examples of each category.

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review and synthesis of co‐creation in health‐enabling initiatives in food retail outlets found studies utilized varying study approaches to co‐creation and different types and involvement of stakeholders. All studies involved at least academics and retailers and used participatory methods, typically working with lower socioeconomic and Indigenous populations. The studies reviewed focused on presenting outcomes of the primary aim of the study rather than processes of co‐creation. We found that the motivations reported by retails extended beyond profit to include health outcomes.

In this review, co‐design was referred to by authors in some studies as an important part of co‐creation but was not described in detail. It was common that the included studies expressed the co‐creation approach as a participatory and problem‐solving method. For example, Gudzune et al's 65 formative research considered views and concerns of farmers and retailers to define the process of implementation through participatory methods. This agrees with the literature, as co‐creation has grown from participatory methods in business research aiming to engage diverse stakeholders to plan, conduct, evaluate, and report change initiatives, 37 including complexity‐informed interventions, 30 and only recently entered public health literature.

The heterogeneity of approaches to co‐creation we identified limits recommendations and the application of co‐creation as a systematic approach for health‐enabling initiatives in supermarkets and grocery stores. Correlation between theoretical approaches, study design, and co‐creation was not clear, as there are differences on the level of detail provided between studies. Research in co‐creation to improve the healthiness of the food retail environment is underdeveloped. 45 Leask et al 37 propose a checklist for reporting co‐creation initiatives more broadly, which will help authors in future to better detail co‐creation processes. This checklist however considers co‐creation as occurring at a point in time as a participatory method, rather than a continuum that brings multiple stakeholders together through the stages of initiation, identification [consultation], definition, design, realization, and evaluation, as we have analyzed it in this review. Leask et al 37 checklist can help to provide consistency in the reporting of co‐creation as a participatory method, in the same way as the PRISMA checklist does for systematic reviews. We consider that approaching co‐creation as a more encompassing approach can provide better understanding to the complexity of food retail environment initiatives and stakeholder collaborations that can sustain these initiatives over time.

The included studies that reported retailers' motivations to be involved in the co‐created initiative showed that despite supermarkets and retail stores are driven by profit, the extrinsic motivation to include better health outcomes for communities is also present. Although identification of motivations for value co‐creation is a common practice in marketing, 81 , 82 , 83 there is limited knowledge of retailers' motivations to sell healthy foods. Previous studies have described retailer's willingness to engage in healthy food retail and a desire for greater support to implement healthy food retail initiatives, but mostly in independent food stores where retailers have a higher power of in‐store decision making. 84 Additionally, some food retailers that engage with community‐based institutions tend to create a mix of profit motive and community benefit that can be related to health. 4 The THRIVE study demonstrated that an increase in fruits and vegetables sales did not negatively affect total store sales. 85 The Healthy Stores 2020 study found no adverse impact on business outcomes with a strategy that successfully restricted merchandising of unhealthy food and drinks. 77

4.1. Strengths

This review applied systematic methods across five scientific databases and study inclusion/exclusion criteria assessed by two independent coauthors. Though our review focused on the use of co‐creation, the search terms included a far broader set of design terms including co‐design, co‐production, and participatory research terms. In this way, the initial data corpus was broad enough to include studies that may use principles and techniques from co‐creation without using the specific term to describe them. As such, this review provides a comprehensive summary of the use of co‐creation approaches, in healthy food retail research beyond the limitation of the term “co‐creation.” This review has summarized a broad range of co‐creation attributes for the first time in health‐enabling food retail outlets. It sets the basis to develop principles for co‐creation practice and adds value to practitioners as well as directs future research in stakeholder co‐creation in food retail outlets.

4.2. Limitations

Our research was limited to the academic literature. Gray literature databases were not reviewed, meaning government reports and other. The databases were all health specific, meaning those appearing only in the business or management literature were not observed. Including some search terms such as “process evaluation” may have identified more studies that reported the co‐creation process. Data extraction and interpretation was subjective as it was based on article's reporting and the lack of clear frameworks to guide descriptions of co‐creation at the time of some publications.

4.3. Future research

Further research is warranted to provide deeper insight into how co‐creation can help deliver the WHO 1 and UN's Sustainable Development Goals 29 principles of multisectoral action. 51 , 86 Business services 31 , 87 have recognized the power of co‐creation for creating meaningful change. Business models may provide new directions for co‐creation with retailers, as co‐creation presents a potentially powerful method to engage food retail environments to create healthier purchasing patterns and subsequently diets.

To advance co‐creation as an innovative collaborative approach, more attention should be placed on describing the development process. This way studies can be aligned with the principles of co‐creation, 35 mostly related to elements that could identify motivations, enhance the co‐creation of value, and promote the interaction and engagement between stakeholders. Future research should also investigate the feasibility, impact, and scalability of co‐created interventions in food retail outlets. Identifying the type of motivations of diverse stakeholders as well as the degree of involvement and roles could help to co‐create initiatives that build stronger ties between food retail outlets and communities that tap into corporate social responsibility and identify elements to reproduce and systematize healthy food retail co‐creation research.

5. CONCLUSION

Co‐creation of healthier food retail environments has been used mostly in lower socioeconomic and Indigenous populations. The heterogeneity of evidence and the lack of description limited an assessment of effectiveness of the process of co‐creation. This review provides insight into a knowledge gap related to the degree of stakeholder involvement, roles, and motivations for future development of healthy food retail co‐creation research. Co‐creation in healthy food retail is being used to improve the health of population diets, and the field may benefit from structured guidance on the theory and practice of co‐creation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CV, JW, JBri, and SA together determined the research questions and search strategy. JW, JBri, and SA provided research guidance throughout the study. CV led the study and undertook the search, screening, article selection, data extraction, quality assessment, and data synthesis. JW, JBro, and MC undertook the screening, article selection, data extraction, and quality assessment. CV drafted the manuscript in collaboration with JW and SA. All authors critically revised the manuscript, provided detail editing, and approved the manuscript submitted.

Supporting information

Table S1. General description of included studies

Table S2. Quality appraisal of included studies

Table S2. Quality appraisal of included studies

Table S4. Author's Reflections and recommendations

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CV, JW, and MC are supported by; and JBri and SA; are researchers within the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)‐funded Centre of Research Excellence in Food Retail Environments for Health (RE‐FRESH) (APP1152968). JW is supported by a Deakin University Dean's Postdoctoral Fellowship. The opinions, analysis, and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the NHMRC. Open access publishing facilitated by Deakin University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Deakin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Vargas C, Whelan J, Brimblecombe J, Brock J, Christian M, Allender S. Co‐creation of healthier food retail environments: A systematic review to explore the type of stakeholders and their motivations and stage of engagement. Obesity Reviews. 2022;23(9):e13482. doi: 10.1111/obr.13482

Funding information Deakin University; National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)‐funded Centre of Research Excellence in Food Retail Environments for Health (RE‐FRESH), Grant/Award Number: APP1152968

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO) . Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: WHO 2013.

- 2. World Health Organization . World Health Assembly approves extension of the global coordination mechanism for noncommunicable diseases 2021 [Oct 30, 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2021-world-health-assembly-approves-extension-of-the-global-coordination-mechanism-for-noncommunicable-diseases

- 3. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development [OECD] . Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Winkler M, Zenk S, Baquero B, et al. A model depicting the retail food environment and customer interactions: components, outcomes, and future directions. Int J Environ res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7591. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dharmasena S, Bessler DA, Capps O. Food environment in the United States as a complex economic system. Food Policy. 2016;61:163‐175. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Townshend T, Lake AA. Obesogenic urban form: theory, policy and practice. Health Place. 2009;15(4):909‐916. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lake A, Townshend T. Obesogenic environments: exploring the built and food environments. J R Soc Promot Health. 2006;126:262‐267. doi: 10.1177/1466424006070487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swinburn B, Kraak V, Rutter H, et al. Strengthening of accountability systems to create healthy food environments and reduce global obesity. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2534‐2545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61747-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vandevijvere S, Waterlander W, Molloy J, Nattrass H, Swinburn B. Towards healthier supermarkets: a national study of in‐store food availability, prominence and promotions in New Zealand. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:971‐978. doi: 10.1038/s41430-017-0078-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sacks G, Kwon J, Vandevijvere S, Swinburn B. Benchmarking as a public health strategy for creating healthy food environments: an evaluation of the INFORMAS initiative (2012–2020). Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:345‐362. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-100919-114442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid . Naar een voedselbeleid. Den Haag/Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kunst A. Grocery shopping by type in the U. S 2021 2022. [Mar 17, 2022]. Available from: www.statista.com/forecasts/997202/grocery-shopping-by-type-in-the-us

- 13. Global Agricultural Information Network . Australia: retail food report 2019: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service; 2021. [Mar 17, 2022]. Available from: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Retail%20Foods_Canberra_Australia_06-30-2021.pdf

- 14. Spencer S, Kneebone M. FOODmap: an analysis of the Australian food supply chain. Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Canberra: Australian Government 2012.

- 15. Cohen DA, Babey SH. Contextual influences on eating behaviours: heuristic processing and dietary choices: Contextual influences on eating behaviours. Obes Rev. 2012;13(9):766‐779. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01001.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glanz K, Bader MDM, Iyer S. Retail grocery store marketing strategies and obesity: an integrative review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:503‐512. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schultz S, Cameron AJ, Grigsby‐Duffy L, et al. Availability and placement of healthy and discretionary food in Australian supermarkets by chain and level of socio‐economic disadvantage. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:203‐212. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020002505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pulker C, Trapp G, Scott J, Pollard C. What are the position and power of supermarkets in the Australian food system, and the implications for public health? A systematic scoping review. Obes Rev. 2018;19:198‐218. doi: 10.1111/obr.12635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gittelsohn J, Rowan M, Gadhoke P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E59‐E74. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gittelsohn J, Laska MN, Karpyn A, Klingler K, Ayala GX. Lessons learned from small store programs to increase healthy food access. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38:307‐315. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.2.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glanz K, Johnson L, Yaroch AL, Phillips M, Ayala GX, Davis EL. Measures of retail food store environments and sales: review and implications for healthy eating initiatives. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48:280‐288. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adam A, Jensen JD. What is the effectiveness of obesity related interventions at retail grocery stores and supermarkets? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1‐18. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3985-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cameron A, Charlton E, Ngan W, Sacks G. A systematic review of the effectiveness of supermarket‐based interventions involving product, promotion, or place on the healthiness of consumer purchases. Curr Nutr Rep. 2016;5:129‐138. doi: 10.1007/s13668-016-0172-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Castro IA, Majmundar A, Williams CB, Baquero B. Customer purchase intentions and choice in food retail environments: a scoping review. Int J Environ res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2493. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hartmann‐Boyce J, Bianchi F, Piernas C, et al. Grocery store interventions to change food purchasing behaviors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(6):1004‐1016. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Houghtaling B, Serrano EL, Kraak VI, Harden SM, Davis GC, Misyak SA. A systematic review of factors that influence food store owner and manager decision making and ability or willingness to use choice architecture and marketing mix strategies to encourage healthy consumer purchases in the United States, 2005‐2017. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0767-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan J, McMahon E, Brimblecombe J. Point‐of‐sale nutrition information interventions in food retail stores to promote healthier food purchase and intake: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2021;22(10):e13311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Middel C, Schuitmaker‐Warnaar T, Mackenbach J, Broerse J. Systematic review: a systems innovation perspective on barriers and facilitators for the implementation of healthy food‐store interventions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16:1‐15. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0867-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. United Nations . Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. General Assembly, Seventieth Session A/RES/70/1 2015 [Oct 30, 2021]. Available from: https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1

- 30. von Heimburg D, Cluley V. Advancing complexity‐informed health promotion: a scoping review to link health promotion and co‐creation. Health Promot Int. 2021;36:581‐600. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaa063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janamian T. Achieving research impact through co‐creation in community‐based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q. 2016;94:392‐429. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramaswamy V, Gouillart F. Build the co‐creative enterprise. Harv Bus Rev. 2010;88:100‐109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramaswamy V, Ozcan K. The Co‐Creation Paradigm. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press; 2014. doi: 10.1515/9780804790758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones P. Contexts of co‐creation: designing with system stakeholders: theory, methods, and practice. In: Jones P, Kijima K, eds. Systemic Design Translational Systems Sciences. Springer: Tokyo; 2018:3‐52. doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-55639-8_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ramaswamy V, Gouillart F. Building the co‐creative enterprise: give all your stakeholders a bigger say, and they'll lead you to better insights, revenues, and profits. Harv Bus Rev. 2010;88:100‐109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ansell C, Torfing J. Public governance as co‐creation: a strategy for revitalizing the public sector and rejuvenating democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leask CF, Sandlund M, Skelton DA, et al. Framework, principles and recommendations for utilising participatory methodologies in the co‐creation and evaluation of public health interventions. Res Involv Engagem. 2019;5(1):1‐16. doi: 10.1186/s40900-018-0136-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vargas C, Whelan J, Brimblecombe J, Allender S. Co‐creation, co‐design, co‐production for public health – a perspective on definition and distinctions. Public Health res Pract. 2022;32:e3222211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bovill C, Felten P. Cultivating student‐staff partnerships through research and practice. Int J Acad Dev. 2016;21:1‐3. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Healey M, Flint, A. , & Harrington, K. (ed). Engagement through partnership: students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. Higher Education Academy: York 2014.

- 41. Smeds R, Lavikka R, Jaatinen M, Hirvensalo A. Interventions for the Co‐creation of Inter‐organizational Business Process Change. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015:11‐18. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22759-7_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sanders EBN, Stappers PJ. Co‐creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign. 2008;4:5‐18. doi: 10.1080/15710880701875068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karnøe P, Garud R. Path creation: co‐creation of heterogeneous resources in the emergence of the Danish wind turbine cluster. European Planning Studies. 2012;20:733‐752. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.667923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Galvagno M, Dalli D. Theory of value co‐creation: a systematic literature review. Manag Serv Qual. 2014;24:643‐683. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Halvorsrud K, Kucharska J, Adlington K, et al. Identifying evidence of effectiveness in the co‐creation of research: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the international healthcare literature. J Public Health. 2021;43:197‐208. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdz126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Torfing J, Sørensen E, Røiseland A. Transforming the public sector into an arena for co‐creation: barriers, drivers, benefits, and ways forward. Adm Soc. 2019;51:795‐825. doi: 10.1177/0095399716680057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Goodyear‐Smith F, Jackson C, Greenhalgh T. Co‐design and implementation research: challenges and solutions for ethics committees. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:1‐15. doi: 10.1186/s12910-015-0072-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Oertzen A‐S, Odekerken‐Schröder G, Brax SA, Mager B. Co‐creating services—conceptual clarification, forms and outcomes. J Serv Manag. 2018;29:641‐679. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-03-2017-0067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mah CL, Luongo G, Hasdell R, Taylor NGA, Lo BK. A systematic review of the effect of retail food environment interventions on diet and health with a focus on the enabling role of public policies. Curr Nutr Rep. 2019;8:411‐428. doi: 10.1007/s13668-019-00295-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Voorberg WH, Bekkers VJJM, Tummers LG. A systematic review of co‐creation and co‐production: embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag Rev. 2015;17(9):1333‐1357. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2014.930505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Google LLC . Google Translate. Mountain View, United States of America, USA.

- 53. The EndNote Team . EndNote. Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA 2013.

- 54. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; 2021. [Electronic tool]. Available from: www.covidence.org

- 55. Prahalad CK, Ramaswamy V. Co‐creation experiences: the next practice in value creation. J Interact Mark. 2004;18(3):5‐14. doi: 10.1002/dir.20015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool: user guide 2018 [Oct 29, 2021]. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

- 57. Mix Methods Appraisal Tool. Reporting the results of the MMAT 2018 [Oct 29, 2021]. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/page/24607821/FrontPage

- 58. Schurman M. Community teamwork in nutrition education: an example in Canada's north. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1983;37:172‐179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Light L, Tenney J, Portnoy B, et al. Eat for health: a nutrition and cancer control supermarket intervention. Public Health Rep. 1989;104(5):443‐450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Närhinen M, Nissinen A, Puska P. Healthier choices in a supermarket: the municipal food control can promote health. Br Food J. 1999;101(2):99‐107. doi: 10.1108/00070709910261909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gittelsohn J, Roache C, Kratzmann M, Reid R, Ogina J, Sharma S. Participatory research for chronic disease prevention in Inuit communities. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:453‐464. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.34.4.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kolahdooz F, Pakseresht M, Mead E, Beck L, Corriveau A, Sharma S. Impact of the Healthy Foods North nutrition intervention program on Inuit and Inuvialuit food consumption and preparation methods in Canadian Arctic communities. Nutr J. 2014;13:68. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gittelsohn J, Vijayadeva V, Davison N, et al. A food store intervention trial improves caregiver psychosocial factors and childrens dietary intake in Hawaii. Obesity. 2010;18:S84‐S90. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Novotny R, Vijayadeva V, Ramirez V, Lee SK, Davison N, Gittelsohn J. Development and implementation of a food system intervention to prevent childhood obesity in rural Hawai'i. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70:42‐46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gudzune KA, Welsh C, Lane E, Chissell Z, Anderson Steeves E, Gittelsohn J. Increasing access to fresh produce by pairing urban farms with corner stores: a case study in a low‐income urban setting. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(15):2770‐2774. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015000051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ortega A, Albert S, Sharif M, et al. Proyecto MercadoFRESCO: a multi‐level, community‐engaged corner store intervention in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights. J Community Health. 2015;40:347‐356. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9941-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Young KA, Clark JK. Examination of the strategy, instruments, and measurements used to evaluate a healthy corner store intervention. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2014;9:449‐470. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2014.929543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Adjoian T, Dannefer R, Willingham C, Brathwaite C, Franklin S. Healthy checkout lines: a study in urban supermarkets. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(8):615‐622. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pothukuchi K. Bringing fresh produce to corner stores in declining neighborhoods: reflections from Detroit FRESH. J Agric Food Syst Community Dev. 2016;7:113‐134. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2016.071.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Thorndike AN, Bright OJM, Dimond MA, Fishman R, Levy DE. Choice architecture to promote fruit and vegetable purchases by families participating in the special supplemental program for women, infants, and children (WIC): randomized corner store pilot study. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:1297‐1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Winkler LL, Christensen U, Glümer C, et al. Substituting sugar confectionery with fruit and healthy snacks at checkout ‐ a win‐win strategy for consumers and food stores? A study on consumer attitudes and sales effects of a healthy supermarket intervention. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1184. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3849-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Brimblecombe J, Bailie R, van den Boogaard C, et al. Feasibility of a novel participatory multi‐sector continuous improvement approach to enhance food security in remote Indigenous Australian communities. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:566‐576. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Jernigan VBB, Williams M, Wetherill M, et al. Using community‐based participatory research to develop healthy retail strategies in Native American‐owned convenience stores: the THRIVE study. Prev Med Rep. 2018;11:148‐153. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bird Jernigan VB, Salvatore AL, Williams M, et al. A healthy retail intervention in Native American convenience stores: the THRIVE community‐based participatory research study. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:132‐139. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Young S, DeNomie M, Sabir J, Gass E, Tobin J. Around the corner to better health: a Milwaukee corner store initiative. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32:1353‐1356. doi: 10.1177/0890117117736970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Fehring E, Ferguson M, Brown C, et al. Supporting healthy drink choices in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: a community‐led supportive environment approach. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2019;43(6):551‐557. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Brimblecombe J, McMahon E, Ferguson M, et al. Effect of restricted retail merchandising of discretionary food and beverages on population diet: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(10):e463‐e473. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30202-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Young L, Rosin M, Jiang Y, et al. The effect of a shelf placement intervention on sales of healthier and less healthy breakfast cereals in supermarkets: a co‐designed pilot study. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113337. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bogomolova S, Carins J, Dietrich T, Bogomolov T, Dollman J. Encouraging healthier choices in supermarkets: a co‐design approach. Eur J Mark. 2021;55(9):2439‐2463. doi: 10.1108/EJM-02-2020-0143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rollins L, Carey T, Proeller A, et al. Community‐based participatory approach to increase African Americans access to healthy foods in Atlanta, GA. J Community Health. 2021;46(1):41‐50. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00840-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Palma FC, Trimi S, Hong S‐G. Motivation triggers for customer participation in value co‐creation. Serv Bus. 2019;13:557‐580. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Roberts D, Hughes M, Kertbo K. Exploring consumers' motivations to engage in innovation through co‐creation activities. Eur J Mark. 2014;48:147‐169. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Holbrook MB. Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: an illustrative photographic essay. J Bus res. 2006;59:714‐725. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Martinez O, Rodriguez N, Mercurio A, Bragg M, Elbel B. Supermarket retailers' perspectives on healthy food retail strategies: in‐depth interviews. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1019. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5917-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Williams MB, Wang W, Taniguchi T, et al. Impact of a healthy retail intervention on fruits and vegetables and total sales in tribally owned convenience stores: findings from the THRIVE study. Health Promot Pract. 2021;22(6):796‐805. doi: 10.1177/1524839920953122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ramaswamy V, Ozcan K. Embracing the co‐creation paradigm. In: Ramaswamy V, Ozcan K, eds. The Co‐Creation Paradigm. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press; 2014:278‐289. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ramaswamy V, Ozcan K. What is co‐creation? An interactional creation framework and its implications for value creation. J Bus res. 2018;84:196‐205. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. General description of included studies

Table S2. Quality appraisal of included studies

Table S2. Quality appraisal of included studies

Table S4. Author's Reflections and recommendations