Abstract

Despite two decades of declining crime rates, the United States continues to incarcerate a historically and comparatively large segment of the population. Moreover, incarceration and other forms of criminal justice contact ranging from police stops to community supervision are disproportionately concentrated among African American and Latino men. Mass incarceration, and other ways in which the criminal justice system infiltrates the lives of families, has critical implications for inequality. Differential rates of incarceration damage the social and emotional development of children whose parents are in custody or under community supervision. The removal through incarceration of a large segment of earners reinforces existing income and wealth disparities. Patterns of incarceration and felony convictions have devastating effects on the level of voting, political engagement, and overall trust in the legal system within communities. Incarceration also has damaging effects on the health of families and communities. In short, the costs of mass incarceration are not simply collateral consequences for individuals but are borne collectively, most notably by African Americans living in acutely disadvantaged communities that experience high levels of policing and surveillance. In this article, we review racial and ethnic differences in exposure to the criminal justice system and its collective consequences.

Introduction

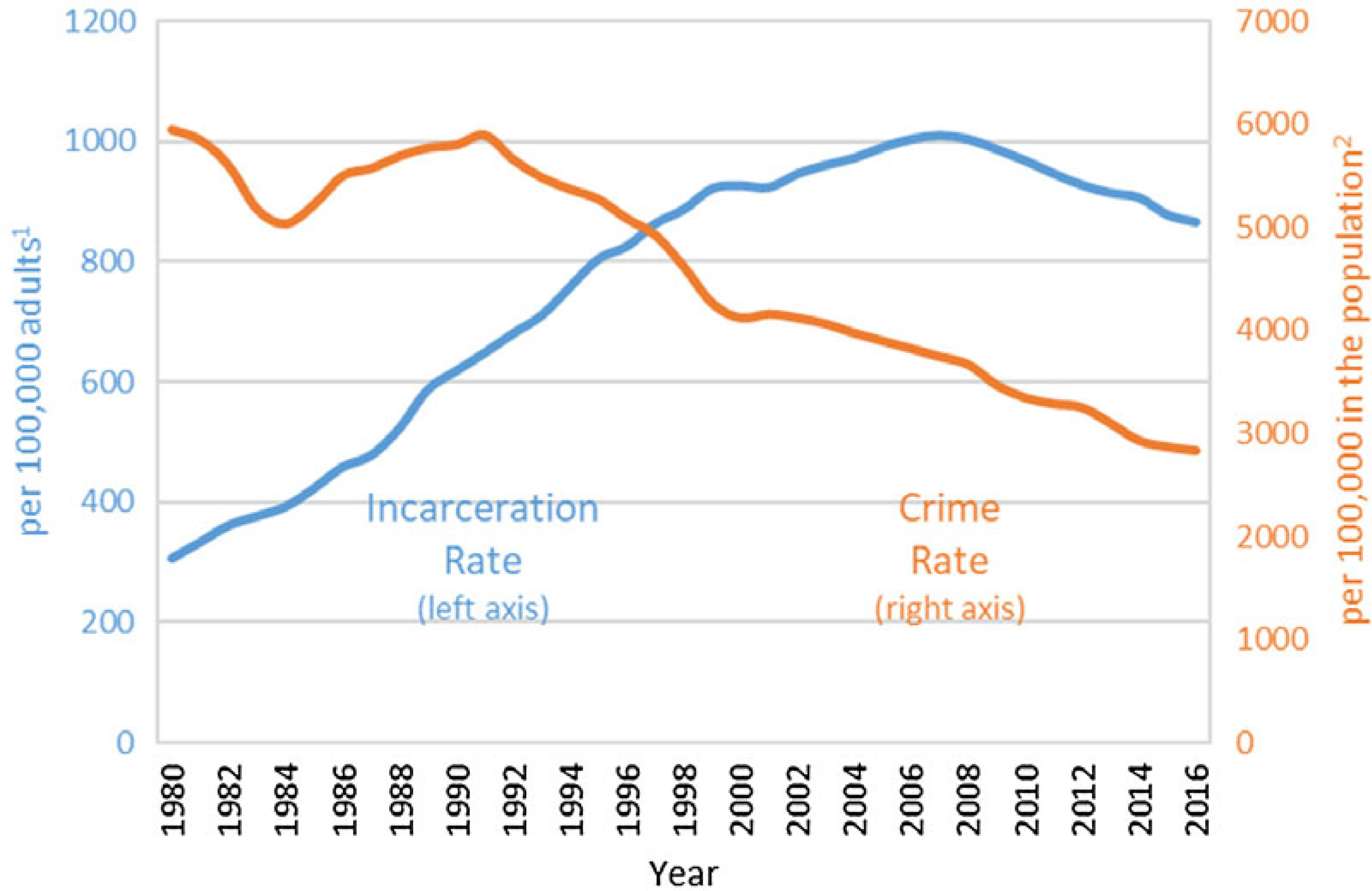

Despite two decades of declining crime rates and significant and sustained policy attention to criminal justice reform, the United States continues to incarcerate a comparatively large segment of the population. (For a discussion of some recent policy initiatives, see Obama (2017).) The United States experienced unprecedented increases in the volume and rate of incarceration between the mid-1970s and the first decade of the 2000s. The number of individuals incarcerated in America’s prisons and jails peaked in 2008, when just over 2.3 million people, or 1 in 100 adults, were behind bars. Recent estimates suggest that close to 2.2 million people are incarcerated in the United States on any given day (Carson 2018). Figure 1 shows that although crime rates hover near their lowest level in decades, the incarceration rate is three times higher than the rate in 1980.

Figure 1.

Incarceration and crime trends in the U.S., 1980–2016.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (1980–2016) for incarceration rates. U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (1980–2016) for crime rates. U.S. National Cancer Institute (1969–2017) for resident population of the United States.

Note: The incarceration rate includes prison and jail inmates.

1The adult population includes all U.S. residents ages 18 and older.

2The population includes all U.S. residents of all ages.

High rates of incarceration in the contemporary United States are also unique in comparison to incarceration rates in other countries. Even after recent declines in the total number of people held in prisons and jails, the United States continues to incarcerate a much higher fraction of its population than any other wealthy nation in the world. People living in the United States are more than 10 times as likely to be in prison or jail as people living in Denmark, Sweden, or the Netherlands and four times as likely compared to residents of the United Kingdom (Aebi, Mélanie, and Burkhardt 2016; Coyle et al. 2016; Hartney 2006; Kaeble and Cowhig 2018).

Mass incarceration, or the widespread incapacitation of people in prisons and jails, does not randomly or equally affect all subgroups in the population. Rather, mass incarceration is characterized by its systematic targeting of particular segments of the population (Garland 2001). Indeed, like other forms of criminal justice contact, incarceration is disproportionately concentrated among men, African Americans, and those with low levels of formal schooling. No other group suffers the overwhelming likelihood of imprisonment experienced by young black males in the United States who do not complete high school (Pettit and Western 2004); Western and Wildeman 2009; Pettit 2012; Travis et al. 2014: ch. 2).

Despite the concentrated incarceration of young black men, the effects of mass incarceration extend well beyond the individuals living behind bars. Mass incarceration has generated not only direct implications for inequality through the systematic removal of young black men from free society but also indirect consequences for inequality as a result of its impacts on children, families, and communities that simultaneously suffer. Mass incarceration, and other forms of criminal justice contact, from police stops to community-based supervision, generate consequences related to employment, wages, political engagement, health, neighborhood stability, and a host of other considerations (Clear 2007; Kling 2006; Lee, Porter, and Comfort 2014; Massoglia, Firebaugh, and Warner 2013; Massoglia and Pridemore 2015; Pager 2003, Pager 2007; Sampson and Loeffler 2010; Schnittker and John 2007; Uggen and Manza 2002; Weaver and Lerman 2010; Western 2002, 2006; Western and Pettit 2000). In this article, we discuss research on the consequences of incarceration and the other ways the criminal justice system disrupts people’s lives and how exposure to the system and its effects collectively impact social equality.

Trends in Exposure to Mass Incarceration and Criminal Justice Contact

After steadily rising for nearly 40 years, the number of people incarcerated in the United States has hovered close to 2.2 million throughout the last decade (Kaeble and Cowhig 2018). Other forms of criminal justice supervision such as probation and parole have also grown to the extent that an additional 4.7 million people are under the surveillance of probation or parole agencies (Kaeble 2018). Far more commonly than either incarceration or community supervision, however, people encounter the criminal justice system for misdemeanor, or other relatively minor, infractions. Estimates suggest that nearly 20 million people have a felony conviction (Shannon et al. 2012). Around 70 million Americans, or slightly more than one-third of adults, have a criminal record (Sentencing Project 2014a). Nearly 25 million people are pulled over each year for routine traffic stops that can carry criminal sanctions, like fines and fees, which may widen the net of criminal justice involvement (Langton and Matthew 2013). A growing body of research considers how misdemeanor offenses, or other relatively minor infractions against the law, shape the way people interact with the police and the judicial system even in the absence of spending time in prison or jail (Comfort 2016; Kohler-Hausmann 2013, 2018; Lageson 2016; Napatoff 2015; Uggen et al. 2014). Excessive and unnecessary traffic stops uniquely concentrated among African Americans can fuel racial inequality in experiences with a maze of criminal justice procedures and their consequences (Baumgartener et al. 2018).

Simple counts of the number of people incarcerated, under criminal justice supervision, arrested, or stopped by the police do not fully reveal the extent to which different forms of contact with the criminal justice system are stratified by gender, race, ethnicity, or education and thus represent a critical axis of inequality. Table 1 presents estimates of adult men’s exposure to the criminal justice system by race and ethnicity. Consistent with accounts that emphasize racial differences in surveillance, policing, prosecution, and sentencing, racial disproportionality in exposure to the criminal justice system varies in relation to types of contact.

Table 1.

Criminal activity among men (by race/ethnicity) and points of contact with the criminal justice system (arrest, conviction, incarceration, and probation)

| Race/Ethnicity | Magnitude Differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Whitea | Blacka | Latino | Black: White | Latino: White | Black: Latino | |

| Criminal offending1 | ||||||

| Sold drugs1a | 22.0 | 16.6 | 19.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Committed violence1b | 8.4 | 9.8 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 3.6 |

| Risk of arrest2 | 37.9 | 48.9 | 43.8 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Felony conviction3 | 12.8 | 33.0 | - | 2.6 | - | - |

| Risk of incarceration4 | 5.4 | 26.8 | 12.2 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| Imprisonment rates | ||||||

| Jail5a | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 7.5 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Prison5b | 1.6 | 9.1 | 3.9 | 5.7 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| Community supervision | ||||||

| Probation | 2.4 | 8.3 | - | 3.5 | - | - |

Not of Hispanic of Latin origin.

Self-reported estimates.

Percent of youth ages 12–29 who reported ever having sold illicit drugs (Mitchell and Caudy 2017).

Rate of simple assault incidents per 1,000 persons age 12 and older from 2012 to 2015 (Morgan 2017).

Percent of men ever arrested by age 23, born 1980–1984 (Brame et al. 2014).

Percent of voting-age men in the population with a felony conviction in 2010 (Shannon et al. 2012).

Percent of men ever incarcerated in state or federal prison by age 30–34, born 1975–1979 (Western and Wildeman 2009).

Percent of adult men age 18 and older in jail at midyear in 2005 (Harrison and Beck 2006).

Rate of incarceration for adult men ages 20–34 in 2015 (Pettit and Sykes 2017).

Low-level forms of engagement with the police and judicial system are more evenly distributed by race and ethnicity than are more intensive forms of contact and supervision. Self-reports of criminal offending are relatively similar between young black and white men. According to recent estimates of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 and the National Crime Victimization Survey, whites are slightly more likely to report having ever sold illicit drugs (Mitchell and Caudy 2017). By contrast, blacks are slightly more likely to report having been involved in violence (Morgan 2017). While there are no national estimates on the prevalence of police stops and surveillance across socio-demographic groups, local studies show that despite similarities in rates of offending, African Americans, and black men in particular, are disproportionately surveilled and stopped by the police (Beckett et al. 2005; Fagan and Davis 2000; Fagan et al. 2010; Kohler-Hausmann 2013; Stuart 2016).

Table 1 also shows that engagement with the police and judicial system that does not involve spending time in jail or prison—from arrests to community-based supervision—are disproportionately concentrated among racial and ethnic minority groups, though the extent of that disproportionality varies widely. Brame et al. (2012, 2014) estimate that fully one-quarter (25.3 percent) of young adults are arrested by age 23 and further show that nearly half (48.9 percent) of black men are arrested by the time they reach age 23, compared to 37.9 percent of white men. One in 55 adults is under criminal justice supervision through probation or parole (Kaeble 2018). Although disproportionality in exposure to this type of supervision is less severe than inequalities in incarceration rates, black men are 3.4 times as likely as white men to be under supervision (Phelps 2017). Fully 8 percent of all adults, 13 percent of male adults, and 33 percent of adult males who are African American have a felony conviction (Shannon et al. 2012). Among men between 20 and 40, the share of those with a felony conviction is over seven times greater for blacks and almost three times greater for Latinos, relative to the felony conviction rate among whites (Wakefield and Uggen 2010).

In the United States, incarceration is even more acutely concentrated among African American and Latino men than most other forms of criminal justice contact. By the end of 2015, approximately 1.6, 9.1, and 3.9 percent of young white, black, and Hispanic men, ages 20 to 34, were incarcerated on any given day, respectively. These numbers are substantially higher among those without a high school diploma (Travis et al. 2014: ch. 2). Table 1 also shows that lifetime risks of spending at least a year in prison are significantly higher than point-in-time estimates of the incarceration rate: over one-quarter of black men born in the late-1970s experienced incarceration by the time they reached their 30s. For black men born in the late-1970s who did not complete high school, the odds of imprisonment for at least a year by the time they reached their 30s increased to over 60 percent (Pettit 2012; Pettit and Western 2004; Travis et al. 2014: ch. 2; Western and Wildeman 2009).

Socio-demographic differences in punishment among adults translates into disproportionality in exposure to the criminal justice system and its consequences for partners, family members, children, and communities. Black women, in particular, face extraordinarily high chances of having a partner or family member incarcerated. They can expect to have almost two family members incarcerated, on average, whereas the average number of family members that white women can expect to have incarcerated is 0.14 (see Table 2). Even highly educated black women face a disproportionate risk of having one or more family members incarcerated, thus drawing attention to how the criminal justice system uniquely disadvantages African Americans, including those without criminal records (Lee and Wildeman 2013; Lee et al. 2014, 2015; Foster and Hagan 2007).

Table 2.

Exposure to the criminal justice system among children and women by race and ethnicity

| Race/Ethnicity |

Magnitude Differences |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whitea | Blacka | Latino | Black: White | Latino: White | Black: Latino | |

| CHILDREN | ||||||

| Parent currently incarcerated1 | 1.8 | 11.4 | 3.5 | 6.3 | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| Parent ever incarcerated2 | 3.9 | 24.2 | 10.7 | 6.2 | 2.7 | 2.3 |

| WOMEN | ||||||

| Family member incarcerated3 | 11.6 | 43.8 | – | 3.8 | – | – |

| Number of family members incarcerated4 | 1.6 | 0.1 | – | 0.1 | – | – |

Percent of children under age 18 with a parent in prison or jail in 2008 (Pew Charitable Trusts 2010).

Percent of children ages 0–17 expected to have a parent imprisoned at some point during their childhood (Sykes and Pettit 2014).

Percent of women ages 18 and older with at least one family member incarcerated in state or federal prison in 2005 (Lee et al. 2015).

Average number of family members incarcerated in state or federal prison among women ages 18 and older (Lee et al. 2015).

An increase in children’s exposure to parental incarceration over time and socio-demographic differences in children’s exposure to parental incarceration, both over time and over the life course, have important implications for social inequality (Wakefield and Wildeman 2013). Data from Surveys of Inmates of State and Federal Correctional Facilities show that nearly 1.5 million minor children in the United States had a parent in state or federal prison in 1999 (Mumola 2000). Estimates that include children of parents housed in local jails find that close to 2.1 million children had a biological parent incarcerated at the turn of the century (Sykes and Pettit 2014). Recent estimates show that at the end of 2015, 2.5 million children had a parent housed in a federal, state, or local correctional facility (Pettit and Sykes 2017). Accordingly, 1 in 14 children can expect to have a parent incarcerated at some point before their 18th birthday (Murphey and Cooper 2015). Nearly 1 in 4 black children can expect to have a parent imprisoned (Wildeman 2009). Estimates of parental exposure to the criminal justice system more generally are even higher: one recent study suggests that nearly half of American children have a parent who has been arrested (Vallas et al. 2015).

Exposure to the criminal justice system is not only deeply concentrated in certain socio-demographic groups but it is also disproportionately distributed within some of America’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods (Clear 2007; Sampson and Loeffler 2010). In communities with high levels of incarceration, as many as 15 percent of the adult male population cycles back and forth to prison (Clear 2007). As a result, the criminal justice system is now estimated to affect nearly as many people as the education system or the labor market in poor, urban communities marked by high rates of incarceration (Morenoff and Harding 2014).

Contemporary patterns of inequality in both direct and indirect exposure to the criminal justice system are not simply a reflection of racial and ethnic disparities in crime or victimization. The concentration of incarceration and, more generally, of system involvement is due to shifts in policing, prosecution, and sentencing that disproportionately affect historically disadvantaged groups. (Travis et al. (2014: ch. 4) provide a recent overview of this issue.) Existing patterns of stratification—from racial homogamy in family formation, racial segregation in housing, and racially divided schooling—further concentrate the exposure of people of color to the criminal justice system.

Effects of Incarceration and Other Forms of Criminal Justice Contact

Incarceration and other forms of criminal justice contact have both short- and long-term consequences for a host of measureable outcomes for people who are justice-involved, their families, and their communities. Research has shown that spending time in prison has negative effects on 1) employment, earnings, and wage growth; 2) political engagement; and 3) health and well-being. Other measures of justice involvement also affect these and related outcomes, although the evidence is less definitive. Nonetheless, the criminal justice system has become an important and pervasive axis of stratification in the United States.

Economic Self-Sufficiency

Diminished employment opportunities, bouts of unemployment, and lost wages influence economic security and self-sufficiency for individuals who have been incarcerated as well as for their families and children. Having been incarcerated significantly decreases the likelihood that applicants receive call-backs for potential jobs (Pager 2003), 2007). Similar effects are found for having a felony conviction even in the absence of spending time in prison or jail (Uggen et al. 2014). Incarceration significantly depresses employment after release and is also associated with extended periods of unemployment, especially among low-skilled black men (Apel and Sweeten 2010; Western 2002, 2006). Evidence on the effects of other types of interaction with police and the courts are more mixed, yet recent research shows that even minor contacts with the criminal justice system can have important negative consequences because of inconsistencies between routines of work and demands of the court, including repeated court appearances (Kohler-Hausman 2018).

Incarceration has been shown to depress wages and wage growth even among former inmates who find work upon their release (Apel and Sweeten 2010; Lageson and Uggen 2013; Loeffler 2013; Mueller-Smith 2014; Ramakers et al. 2014; Western 2002, 2006). Even relatively short stints in jail can have long-term implications for wage growth and wealth (Sykes and Maroto 2016; Western 2006). Incarceration is associated with time out of the labor force, lost work experience, and skill depreciation (Kling 2006; Raphael 2011). However, there are also direct wage penalties associated with spending time in prison that result from the stigmatizing effects of any contact with the criminal justice system (Mueller-Smith 2014; Pager 2003, 2007; Western 2006). More than 90 percent of employers in the United States are estimated to obtain background checks on at least some of their potential hires (Jacobs 2015). Employers express much less enthusiasm about hiring a person with a criminal record than hiring a person with a spotty work history or a history of unemployment (Holzer et al. 2006).

The economic consequences of incarceration and other forms of engagement with the criminal justice system extend well beyond people who are justice-involved. Incarceration diminishes contributions to families (Geller et al. 2011). It also increases household financial burdens associated with livelihood, such as childcare expenses (Braman 2004; Grinstead et al. 2001). Family members, especially mothers and partners, bear excess financial burdens—from posting bail, to paying legal fines and fees, to visitation and related costs (Comfort 2007; Harris, Evans, and Beckett 2010, 2011; Harris 2016; Maroto 2015). Financial obligations associated with criminal convictions, transferred to family members, can fuel a cycle of debt and obligation that spans across generations (Harris 2016).

Economic insecurity associated with incarceration critically affects families and children through increased household instability. Having a criminal record affects the ability to secure and sustain housing (Lee, Tyler, and Wright 2010). Children of recently incarcerated fathers are three times more likely to experience homelessness than children without incarcerated fathers. Even after adjusting for many of the preexisting family and household differences between children with and without incarcerated parents—such as welfare receipt, eviction history, public housing history, alcohol and drug abuse among parents, and family violence—paternal incarceration is found to increase the risk of childhood homelessness by 94 to 97 percent (Wakefield and Wildeman 2013). Parental incarceration pushes even formerly non-poor children into poverty and entrenches their dependence on state and federal assistance programs (Sykes and Pettit 2015).

Politics

Incarceration has widespread consequences for civic engagement. Having a felony record, even in the absence of spending time in prison or jail, can prohibit people from political participation. Forty-eight states prohibit people who are currently imprisoned from voting. Thus, incapacitation alone excludes over a million people each year from the franchise; having a felony record precludes millions more from voting long after they complete their custodial sentence (Manza and Uggen 2008; Uggen, Larson, and Shannon 2016). Whether, and for whom, formerly incarcerated individuals would vote is a matter of some debate (Burch 2011,; Gerber et al. 2017; Miles 2004; Uggen and Manza 2002; Uggen, Manza, and Thompson 2006).

The Sentencing Project (2010) estimates that 13 percent of black men are disenfranchised from voting as a result of their criminal justice involvement. Although some formerly incarcerated individuals remain eligible to vote, voter turnout rates in this group are exceptionally low (Burch 2012, 2013, Gerber et al. 2017; Weaver and Lerman 2010). Despite claims of growing political participation among young blacks, evidence suggests that the exclusionary effects of mass incarceration depressed voter turnout rates among young black men during the historic 2008 election to the extent that they mirrored the low voter participation rates among this group in the 1980 presidential contest (Pettit 2012). If current rates of incarceration and racial disproportionality persist in the future, 30 percent of black men in the next generation can expect to be disenfranchised at some point in their lifetime, and as many as 40 percent of black men may permanently lose their right to vote in states that disenfranchise ex-offenders (Sentencing Project 2012).

The negative effects of mass incarceration on civic engagement extend well beyond voting. Spending time in prison and other forms of criminal justice contact affect civic engagement, trust in institutions, and cynicism about the legal system itself (Baumgartner et al. 2018; Mueller and Schrage 2014; Weaver and Lerman 2010, 2014). Growth over time in incarceration and racial disproportionality in exposure to surveillance is linked to heightened levels of distrust in the law among African Americans (Mueller and Schrage 2014). Racial disproportionality in police stops and the outcomes of those stops fuel race differences in perceptions of the police and their legitimacy. African Americans are much more likely than whites to be stopped by police, yet a disproportionate number of cases where whites are stopped do not generate a citation, further reinforcing beliefs in an unjust system designed to subjugate people of color (Baumgartner et al. 2018).

Trust and engagement in the political system is similarly precarious for family members and romantic partners of incarcerated people as it is for those in, or recently released from, punitive confinement (Lee, Porter, and Comfort 2014; White 2018). The criminal justice system is an important institution in the political socialization of people connected to currently or formerly incarcerated individuals, especially as their relationship with the carceral state alienates them from other mainstream socializing institutions (Flanagan 2003). Accordingly, the political and civil behaviors of individuals connected to the criminal justice system may diminish as a result of the general influence that parents and romantic partners have on shaping these outcomes.

Indeed, individuals with an incarcerated parent or romantic partner are less likely to vote, more likely to feel discriminated against in their daily lives, and less likely to participate in community service (Lee, Porter, and Comfort 2014). While family members are not the primary targets for political disenfranchisement, their propensity for engaging in the political process declines as they experience negative interactions with correctional authorities that erode their beliefs in the fairness of the government as a whole. The spillover consequences of mass incarceration on trust in government and on political engagement more broadly are profound. Children who have experienced the incarceration of a parent exhibit significantly more legal cynicism than other children (White 2018). Being stopped by police depresses trust in the law, especially among African Americans (Baumgartener et al. 2018; Tyler, Fagan, and Geller 2014). In neighborhoods where police surveillance is high and interactions with the police are the result of unsolicited contact initiated by the police, policing is often viewed as racially biased or unfair on other grounds (Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Tyler and Huo 2002; Tyler and Wakslak 2004). When positive views of the police are weakened among individuals within a community, the legitimacy of the police in that area is diminished.

Illegitimate and negative views of the criminal justice system have cascading consequences for inequality within a community, in part by making areas less safe. When individuals experience or perceive unfair treatment from legal authorities, their propensity to cooperate with and follow the law diminishes (Tyler 2003). This process, however, is not unique to individuals. Through social interactions, distrust of the police and negative views of the law more generally become part of the neighborhood milieu (Kirk and Papachristos 2011). Because the police rely on local residents to report crime, to participate in criminal investigations, and to assist in the informal control of crime, the reduction of police legitimacy often puts neighborhoods at risk for growing levels of crime and violence (Carr, Napolitano, and Keating 2007; Kirk et al. 2012; Tyler and Huo).

Health and Well-Being

By and large, incarceration negatively affects health. Incarceration is considered a chronic stressor (Pearlin 1989). It introduces acute shocks to inmates’ immune systems during their time spent behind bars and also throughout their lives. These acute shocks accumulate, causing dysfunction to the immune system that can last for long periods and result in early death (Pridemore 2014). Spending time in jail and prison therefore affects health both during and after incarceration, and the health effects of incarceration manifest in both the short and long term. Because the stress related to incarceration persists beyond the confines of correctional facilities, having spent any amount of time behind bars is considered more consequential for health than the length of incarceration itself (Massoglia 2008a; Schnittker and John 2007).

The negative health effects of incarceration are often most dangerous in the short term, as the period immediately following release from prison and jail is associated with a severely heightened risk of death (Binswanger et al. 2007; Krinsky et al. 2009; Lim et al. 2012; Merrall et al. 2010). In the first two weeks after being released from prison, the rate of death among formerly incarcerated individuals is 13 times higher than the rate for the general population (Binswanger et al. 2007). The leading cause of death during this post-release period is overwhelmingly drug overdose, resulting from the combination of exacerbated stress and poor continuity of healthcare and other forms of support for former inmates on the outside (Binswanger et al. 2011).

The heightened risk of death following release from prison and jail is also observed in the longer term, as incarceration harms the health of former inmates in multiple ways long after their formal sentences are served. In terms of physical health, spending time in prison or jail increases the occurrence of chronic health problems (Schnittker and John 2007). Incarceration also adds to susceptibility to infectious diseases and stress-related illness, such as hypertension and heart disease (Massoglia 2008b). Having spent time in prison during young adulthood is also found to deteriorate physical health functioning for people at middle age (Massoglia 2008b). In terms of mental health, the stress associated with imprisonment also puts formerly incarcerated individuals at higher risk for psychological problems and depression (Massoglia 2008a; Schnittker and John 2007).

Measuring the impact of incarceration as a mechanism of health inequality is complicated by the fact that the negative effects of incarceration on health are uniquely absent among black men (Patterson 2010). Black and white men display similarly poor health upon their entry into prisons and jails (Nowotny, Rogerts, and Boardman 2017). However, incarceration lowers the risk of mortality for black males both during and after their time spent behind bars. The lower mortality among black males could result from increased protection from acute stressors and risks like exposure to violence and drug overdoses. Prison conditions may provide a safer environment than what black males on the outside otherwise encounter. Removing firearm and motor vehicle deaths from the mortality rate of the general population, however, does not fully explain the improved life expectancies of incarcerated black men (Patterson 2010). Lower than expected rates of death among black males in prison are also observed for chronic causes of death, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes (Rosen et al. 2011). Improvements in these cause-specific mortality rates of black men in prison even extends to the period following the first five years after their release (Rosen et al. 2008).

The health benefits of incarceration experienced by black men may therefore be attributed to the constitutionally mandated requirement to make healthcare available in jails and prisons that is otherwise largely inaccessible or unused for this segment of the population. As improvements in the mortality rate of incarcerated black men remain uniquely steady for deaths caused by chronic conditions but not for those caused by external injuries, the treatment and services provided to inmates may generate health benefits that extend well beyond the confines of correctional facilities. Nevertheless, racial disproportionality in exposure to incarceration means that aggregate effects of the criminal justice system fuel racial inequality in health. One way to see this is by measuring the years of life lost associated with incarceration.

Public health scholars and epidemiologists often employ demographic life-table techniques to measure the years of life lost to uncover the impact of large-scale events that adversely impact a population. Drucker (2002) applied this method to incarceration rates during the prison boom in New York, a state that implemented its own legislation to increase the length of prison sentences for non-violent drug offenses under the Rockefeller drug laws (RDL). Using data from the New York State Department of Corrections merged with population estimates and vital statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau, Drucker found that RDL-related offenses accounted for over 325,000 person-years of life lost in New York from 1973 to 2002. With a median age of 35 and a life expectancy of 68 years, this figure is equivalent to the years of life lost associated with nearly 10,000 deaths in a population with the same age, racial, and ethnic composition. Drucker (2002) finds that the magnitude of these years of life lost to incarceration for nonviolent drug offenses is similar to the death toll associated with the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York, especially for young black men. According to Drucker, approximately 242 black men ages 20–45 died in New York City during 2001, accounting for 7,986 years of life lost. In this same population group, the estimated years of life lost due to nonviolent drug incarceration is 8,805, a figure equivalent to 245 deaths.

The health and well-being of partners, children, and communities are also impacted by mass incarceration. For example, people who spend time in jails and prisons face greater risks of sexually transmitted infections and diseases, which may eventually translate to their partners on the outside when they return to society. The concentration of incarceration within communities gravely shapes the disproportionate risk of HIV among black men and women. Through the late 1980s and mid-1990s, the rate of infection was nearly 20 times greater among black women than among white women. After accounting for racial differences in incarceration, however, the infection rate of black women would have been lower than that of white women (Johnson and Raphael 2009; Schnittker, Massoglia, and Uggen 2011). Along with potential detriments to their sexual health, individuals with incarcerated romantic partners experience elevated levels of stress as a result of their partner’s incarceration, exposing them to greater risks of health problems throughout the life course, such as depression in the short term and heart disease in the long term (Lee and Wildeman 2013; Lee et al. 2014).

Children conceived by recently incarcerated men also suffer negative effects to their health in utero, threatening their chance of survival. Wakefield and Wildeman (2013) use data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) to investigate the association between infant mortality (death of a newborn before the first birthday) and paternal incarceration. Among children born to women who did not complete high school, infants with an incarcerated father are 75 percent more likely to die within the first year of their lives than those infants whose fathers are not imprisoned. Controlling for risk factors associated with infant mortality, however, the authors find that paternal incarceration increases the odds of infant death by 49 percent. Nevertheless, the risk of paternal incarceration on infant mortality remains similar to other factors that have long received attention in public health and medical research, such as the effect of maternal smoking, which increases the odds of infant mortality by 46 percent.

It is hard to identify the direct effects of incarceration on a variety of outcomes because families of incarcerated parents experience conditions such as lower educational attainment of parents, greater levels of public assistance utilization, more single-parent households, and greater risks of domestic violence between parents. Nonetheless, incarceration has been shown to negatively impact children’s mental and behavioral well-being, as well as their residential stability, which cumulatively relate to enduring physical health disadvantages (Wakefield and Wildeman 2013).

Collective Consequences of Mass Incarceration

Mass incarceration is a historically novel, uniquely American, mechanism of inequality. In the context of existing patterns of stratification in the labor market, family structure, and neighborhoods, high rates of incarceration and high levels of exposure to the criminal justice system more generally, exact damaging consequences that endure over lifetimes. Mass incarceration is thus a key determinant of racial inequality. At the same time, high concentrations of exposure to partners, parents, and community members who are justice-involved reinforces inequality across geographies, groups, and generations. Thus, while spending time in prison or jail can be a remarkably solitary experience, the costs of mass incarceration are not simply collateral consequences for individuals but are borne collectively, most notably by African Americans living in acutely disadvantaged communities.

Individuals returning home from prison move to a relatively small number of cities, counties, and even neighborhoods, which concentrates the costs of mass incarceration (Clear 2007; Harding et al. 2013; La Vigne and Parthasarathy 2005; Pew Charitable Trusts 2010; Sampson and Loeffler 2010; Visher and Travis 2011). In a longitudinal study of Michigan prisoners paroled in 2003, Morenoff and Harding (2011) find that half of all returning parolees were concentrated in 12 percent of Michigan’s census tracts, and one-quarter of the parolees were concentrated in just 2 percent of the tracts.

Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls (1997) have developed a composite measure of concentrated disadvantage in which a high score represents a greater degree of disadvantage. The average score in the communities where parolees lived was almost one standard deviation higher than the state-wide average, suggesting that the communities where individuals return from prison have considerably higher levels of poverty, unemployment, and residential instability. The disadvantaged conditions of neighborhoods to which individuals return home from prison negatively impact labor market outcomes, including employment, wages, and income. In their study of Michigan parolees, Morenoff and Harding (2011) found that, at most, 20 percent of individuals who returned from prison in the previous year earned sufficient income in the formal labor market to meet the basic material needs of a single person.

Given that mass incarceration is characterized by extraordinarily high rates of criminal justice contact among impoverished black men, and that poor blacks largely reside in racially and economically segregated communities, the effects of mass incarceration are further concentrated by race and ethnicity. Fagan and colleagues (2002) found that incarceration disproportionately affects New York’s poorest neighborhoods, and that these areas received more intense and punitive policing and surveillance even during periods of general declines in crime. Despite a drastic reduction in the number of those at risk of criminal involvement in those neighborhoods, police persistently monitor these communities, perpetuating disadvantage and harm and leading to “the first genuine prison society of history” (Wacquant 2001). By removing large numbers of young men from concentrated areas, incarceration reduces neighborhood stability (Petersilia 2003). The cycling of men between correctional facilities and communities may even begin to trigger higher crime rates within a neighborhood, a process Clear (2007: 73) describes as “coercive mobility.” Contemporary research suggests that high rates of incarceration increase policing and surveillance in local areas in ways that reinforce further punishment.

Other research confirms that prison admissions predominately come from select counties and urban neighborhoods, and that returns from prison are concentrated in many of those very same neighborhoods. Lynch and Sabol (2001) found that a mere 3 percent of the census block groups in Cuyahoga County, Ohio (Cleveland) account for more than 20 percent of the state’s prison population, with an expected 350–700 formerly incarcerated individuals returning to those very same block groups each year following release. Lynch and Sabol further found that, in 1984, approximately 50 percent of prison releases returned to urban counties. By 1996, this figure had increased to 66 percent. For those rearrested after release, the trend was even more dramatic: 42 percent returned to urban counties in 1984 and 75 percent by 1996. For neighborhoods that witness such widespread police surveillance, criminal justice involvement has become an integral component of the collective experience (Weaver and Lerman 2010). Yet, absent perceptible improvements in public safety, heightened surveillance in already disadvantaged neighborhoods leads to repudiation of legal authorities and a reduced willingness to comply with the law (Tyler 2003; Weaver and Lerman 2010).

Mass incarceration produces widespread detrimental outcomes for people who are incarcerated or face other forms of legal punishment, their children and families, and neighborhoods and communities already characterized by crime and disadvantage. Moreover, the legal effects of mass incarceration produce consequences for the nation’s representativeness and participation in democracy and society across generations. The greater disadvantages suffered by single parents in raising children are detailed in the literature on the collateral consequences of mass incarceration on children and families. In addition, children with parents involved in the criminal justice system endure worse mental health and behavioral issues. However, studies of these collateral effects have two drawbacks. The first is a strong male bias. They largely focus on the ways mass incarceration perpetuates future inequality by examining how males in the next generation become caught up in the criminal justice system through the repeated cycle of incarceration within their families and communities. Measuring inequality through the perpetuation of crime and punishment, however, largely ignores the experience of daughters of incarcerated parents since most females never engage in crime to the extent that they face incarceration. The second problem with research on multi-generational impacts is that it does not adequately address how disproportionality in surveillance, policing, prosecution, and sentencing contribute to disproportionality in engagement with legal authorities, quite distinctly from engagement in criminal activities.

While evidence on mass incarceration and its effects are increasingly clear, questions about the implications of new forms of surveillance and other types of contact with the criminal justice system remain. In the age of big data and hyper-surveillance systems, how are the experiences and consequences of mass incarceration related to other ways in which at-risk groups are identified by criminal justice agencies? Does the linkage of data between criminal and noncriminal justice institutions, like banks and health-care systems, undermine the economic, political, and social engagement of historically disadvantaged and hyper-surveilled groups, especially blacks? Do new data technologies from facial recognition to DNA archiving make some groups uniquely vulnerable to increased scrutiny? How do new forms of noncustodial punishment—from fines and fees to repeated court appearances—influence economic, health, and political outcomes for individuals and communities?

Legal and social institutions in the United States increasingly rely on beliefs of colorblindness (avoidance of racial classification), which ignore the underlying social and political processes that differentiate racial groups above and beyond visual differences. Employing colorblind policies and laws in order to achieve equality between racial and ethnic groups denies the social, cultural, and political phenomena attached to race, maintaining injustices for vulnerable minorities. The American criminal justice system and its effects are not colorblind. A wide range of factors have aligned to shape the laws, policies, and practices currently in place that effectively sustain systematic patterns of incarceration. In turn, those patterns concentrate both the experience of criminal justice contact and its consequences among people of color from a relatively small number of communities. The resulting inequalities stray far from and undermine the stated purposes of most laws aimed at reducing and controlling crime. Future research must more directly consider how contemporary rhetoric surrounding colorblindness influences our collective aspirations for equality, representativeness, and democracy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant P2CHD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Her most recent book, Invisible Men: Mass Incarceration and the Myth of Black Progress (Russell Sage Foundation 2012), investigates how decades of growth in America’s prisons and jails obscures basic accounts of racial inequality.

Her research explores issues at the intersection of stratification, the criminal justice system, and health, with an emphasis on how inequalities arise across race, ethnicity, and citizenship.

References

- Aebi Marcelo F., Tiago Mélanie M., and Burkhardt Christine. (2016). “Survey on Prison Populations (SPACE I-Prison Populations Survey 2015).” Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Apel Robert, and Sweeten Gary. (2010). “The Impact of Incarceration on Employment During the Transition to Adulthood.” Social Problems 57(3): 448–479. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner Frank R., Epp Derek A., and Shoub Kelsey. (2018). Suspect Citizens: What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us About Policing and Race. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett Katherine, Nyrop Kris, and L ori Pfingst. (2005). “Race, Drugs, and Policing: Understanding Disparities in Drug Delivery Arrests.” Criminology 44(1): 105–137. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger Ingrid A., Nowels Carolyn, Corsi Karen F., Long Jeremy, Booth Robert E., Kutner Jean, and Steiner John F.. (2011). “‘From the Prison Door Right to the Sidewalk, Everything Went Downhill,’ A Qualitative Study of the Health Experiences of Recently Released Inmates.” International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 34(4): 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger Ingrid A., Stern Marc F., Deyo Richard A., Heagerty Patrick J., Cheadle Allen, Elmore Joann G., and Koepsell Thomas D.. (2007). “Release from Prison—A High Risk of Death for Former Inmates.” New England Journal of Medicine 356(2): 157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braman Donald. (2004). Doing Time on the Outside: Incarceration and Family Life in Urban America. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brame Robert, Turner Michael G., Paternoster Ray, and Bushway Shawn D.. (2012). “Cumulative Prevalence of Arrest from Ages 8 to 23 in a National Sample.” Pediatrics 129(1): 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brame Robert, Bushway Shawn D., Paternoster Ray, and Turner Michael G.. (2014). “Demographic Patterns of Cumulative Arrest Prevalence by Ages 18 and 23.” Crime & Delinquency 60(3): 471–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch Traci. (2011). “Turnout and Party Registration Among Criminal Offenders in the 2008 General Election.” Law & Society Review 45(3): 699–730. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2013). Trading Democracy for Justice: Criminal Convictions and the Decline of Neighborhood Political Participation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carr Patrick J., Napolitano Laura, and Keating Jessica. (2007). “We Never Call the Cops and Here Is Why: A Qualitative Examination of Legal Cynicism in Three Philadelphia Neighborhoods.” Criminology 45(2): 445–480. [Google Scholar]

- Carson E. Ann. (2018). Prisoners in 2016. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 251149. [Google Scholar]

- Clear Todd R. (2007). Imprisoning Communities: How Mass Incarceration Makes Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Worse. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort Megan. (2007). “Punishment Beyond the Legal Offender.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 3: 271–284. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2016). “‘A Twenty-Hour-a-Day Job’: The Impact of Frequent Low-Level Criminal Justice Involvement on Family Life.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 665(1): 63–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle Andrew, Fair Helen, Jacobson Jessica, and Walmsley Roy. (2016). Imprisonment Worldwide: The Current Situation and an Alternative Future. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker Ernest. (2002). “Population Impact of Mass Incarceration Under New York’s Rockefeller Drug Laws: An Analysis of Years of Life Lost.” Journal of Urban Health Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 79(3): 434–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan Jeffrey, and Davies Garth. (2000). “Street Stops and Broken Windows: Terry, Race, and Disorder in New York City.” Fordham Urban Law Journal 28: 457–504. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan Jeffrey, Geller Amanda, Davies Garth, and West Valerie. (2010). “Street Stops and Broken Windows Revisited.” In Race, Ethnicity, and Policing: New and Essential Readings, ed. Rice Stephen K. and White Michael D., pp. 309–348. New York, NY: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan Jeffrey, West Valerie, and Hollan Jan. (2002). “Reciprocal Effects of Crime and Incarceration in New York City Neighborhoods.” Fordham Urban Law Journal 30: 1551–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan Constance. (2003). “Developmental Roots of Political Engagement.” Political Science & Politics 36(2): 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Foster Holly, and Hagan John. (2007). “Incarceration and Intergenerational Social Exclusion.” Social Problems 54(4): 399–433. [Google Scholar]

- Garland David. (2001). Mass Imprisonment: Social Causes and Consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Geller Amanda, Garfinkel Irwin, and Western Bruce. (2011). “Parental Incarceration and Support for Children in Fragile Families.” Demography 48(1): 25–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber Alan S., Huber Gregroy A., Meredith Marc, Biggers Daniel R., and Hendry David J.. (2017). “Does Incarceration Reduce Voting? Evidence About the Political Consequences of Spending Time in Prison.” Journal of Politics 79(4): 1130–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstead Olga, Faigeles Bonnie, Bancroft Carrie, and Zack Barry. (2001). “The Financial Cost of Maintaining Relationships with Incarcerated African American Men: A Survey of Women Prison Visitors.” Journal of African American Men 6(1): 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Harding David J., Morenoff Jeffrey D., and Herbert Claire W.. (2013). “Home Is Hard to Find: Neighborhoods, Institutions, and the Residential Trajectories of Returning Prisoners.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 647(1): 214–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Alexes. (2016). A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Alexes, Evans Heather, and Beckett Katherine. (2010). “Drawing Blood from Stones: Legal Debt and Social Inequality in the Contemporary United States.” American Journal of Sociology 115(6): 1756–1799. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2011). “Courtesy Stigma and Monetary Sanctions: Toward a Socio-Cultural Theory of Punishment.” American Sociological Review 76(2): 234–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hartney Christopher. (2006). U.S. Rates of Incarceration: A Global Perspective. Oakland, CA: National Council on Crime and Delinquency. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer Harry J., Raphael Steven, and Stoll Michael A.. (2006). “Perceived Criminality, Criminal Background Checks, and the Racial Hiring Practices of Employers.” Journal of Law and Economics 49: 451–480. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs James B. (2015). The Eternal Criminal Record. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett Robin. (1992). “A Family Case Study: An Examination of the Underclass Debate.” In Qualitative Methods in Family Research, ed. Gilgun Jane, Daly Kerry, and Handel Gerald, pp. 173–197. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Rucker C., and Raphael Steven. (2009). “The Effects of Male Incarceration Dynamics on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Infection Rates Among African American Women and Men.” Journal of Law and Economics 52(2): 251–293. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble Danielle. (2018). Probation and Parole in the United States, 2016. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 251148. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble Danielle, and Cowhig Mary. (2018). Correctional Populations in the United States, 2016. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 251211. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk David S., and Papachristos Andrew V.. (2011). “Cultural Mechanisms and the Persistence of Neighborhood Violence.” American Journal of Sociology 116(4): 1190–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk David S., Papachristos Andrew V., Fagan Jeffrey, and Tyler Tom R.. (2012). “The Paradox of Law Enforcement in Immigrant Communities: Does Tough Immigration Enforcement Undermine Public Safety?” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 641(1): 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk David S., and Wakefield Sara. (2018). “Collateral Consequences of Punishment: A Critical Review and Path Forward.” Annual Review of Criminology 1: 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kling Jeffrey R. (2006). “Incarceration Length, Employment, and Earnings.” American Economic Review 96(3): 863–876. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler-Hausmann Issa. (2013). “Misdemeanor Justice: Control Without Conviction.” American Journal of Sociology 119(2): 351–393. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2018). Misdemeanorland: Criminal Courts and Social Control in an Age of Broken Windows Policing. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky Clarissa S., Lathrop Sarah L., Brown Pamela, and Nolte Kurt B.. (2009). “Drugs, Detention, and Death: A Study of the Mortality of Recently Released Prisoners.” American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology 30(1): 6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lageson Sarah E. (2016). “Found Out and Opting Out: The Consequences of Online Criminal Records for Families.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 665(1): 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lageson Sarah E., and Uggen Christopher. (2013). “How Work Affects Crime—And Crime Affects Work—Over the Life Course.” In Handbook of Life-Course Criminology, pp. 201–212. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Langton Lynn, and Durose Matthew R.. (2013). Police Behavior During Traffic and Street Stops, 2011. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 24937. [Google Scholar]

- Vigne La, Nancy G, and Parthasarathy Barbara. (2005). Returning Home Illinois Policy Brief: Prisoner Reentry and Residential Mobility. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Barrett A., Tyler Kimberly A., and Wright James D.. (2010). “The New Homelessness Revisited.” Annual Review of Sociology 36: 501–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Hedwig, Tyler McCormick Margaret T. Hicken, and Wildeman Christopher. (2015). “Racial Inequalities in Connectedness to Imprisoned Individuals in the United States.” Du Bois Review 12(2): 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Hedwig, Porter Lauren C., and Comfort Megan. (2014). “Consequences of Family Member Incarceration: Impacts on Civic Participation and Perceptions of the Legitimacy and Fairness of Government.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 651(1): 44–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Hedwig, and Wildeman Christopher. (2013). “Things Fall Apart: Health Consequences of Mass Imprisonment for African American Women.” Review of Black Political Economy 40(1): 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Hedwig, Wildeman Christopher, Wang Emily A., Matusko Niki, and Jackson James S.. (2014). “A Heavy Burden: The Cardiovascular Health Consequences of Having a Family Member Incarcerated.” American Journal of Public Health 104(3): 421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Sungwoo, Seligson Amber L., Parvez Farah M., Luther Charles W., Mavinkurve Maushumi P., Binswanger Ingrid A., and Kerker Bonnie D.. (2012). “Risks of Drug-Related Death, Suicide, and Homicide During the Immediate Post-Release Period Among People Released from New York City Jails, 2001–2005.” American Journal of Epidemiology 175(6): 519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler Charles E. (2013). “Does Imprisonment Alter the Life Course? Evidence on Crime and Employment from a Natural Experiment.” Criminology 51(1): 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch James P., and Sabol William J.. (2001). Prisoner Reentry in Perspective. Crime Policy Report (Vol. 3). Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Manza Jeff, and Uggen Christopher. (2008). Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maroto Michelle L. (2015). “The Absorbing Status of Incarceration and its Relationship with Wealth Accumulation.” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 31(2): 207–236. [Google Scholar]

- Massoglia Michael. (2008a). “Incarceration as Exposure: The Prison, Infectious Disease, and Other Stress-Related Illnesses.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 49(1): 56–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2008b). “Incarceration, Health, and Racial Disparities in Health.” Law & Society Review 42(2): 275–306. [Google Scholar]

- Massoglia Michael, Firebaugh Glenn, and Warner Cody. (2013). “Racial Variation in the Effect of Incarceration on Neighborhood Attainment.” American Sociological Review 78(1): 142–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoglia Michael, and Pridemore William A.. (2015). “Incarceration and Health.” Annual Review of Sociology 41: 291–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrall Elizabeth L. C., Kariminia Azar, Binswanger Ingrid A., Hobbs Michael S., Farrell Michael, Marsden John, Hutchinson Sharon J., and Bird Sheila M.. (2010). “Meta-Analaysis of Drug-Related Deaths Soon After Release from Prison.” Addiction 105(9): 1545–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles Thomas J. (2004). “Felon Disenfranchisement and Voter Turnout.” Journal of Legal Studies 33(1): 85–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Ojmarrh, and Caudy Michael S.. (2017). “Race Differences in Drug Offending and Drug Distribution Arrests.” Crime & Delinquency 63(2): 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff Jeffrey D., and Harding David J.. (2011). Final Technical Report: Neighborhoods, Recidivism, and Employment Among Returning Prisoners. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2014). “Incarceration, Prisoner Reentry, and Communities.” Annual Review of Sociology 40: 411–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Rachel E. (2017). Race and Hispanic Origin of Victims and Offenders, 2012–15. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 250747. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Smith Michael. (2014). “The Criminal and Labor Market Impacts of Incarceration”. Working Paper. New York, NY: Columbia University, Department of Economics. https://www.columbia.edu/mgm2146/incar.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Muller Christopher, and Schrage Daniel. (2014). “Mass Imprisonment and Trust in the Law.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 651(1): 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mumola Christopher J. (2000). Incarcerated Parents and Their Children. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 182335. [Google Scholar]

- Murphey David, and Mae Cooper P. (2015). Parents Behind Bars: What Happens to Their Children? Washington, DC: Child Trends. [Google Scholar]

- Nagin Daniel S., and Tremblay Richard E.. (2001). “Parental and Early Childhood Predictors of Persistent Physical Aggression in Boys from Kindergarten to High School.” Archives of General Psychiatry 58(4): 389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napatoff Alexandra. (2015). “Misdemeanors.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 11: 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny Kathryn M., Rogers Richard, and Boardman Jason D.. (2017). “Racial Disparities in Health Conditions Among Prisoners Compared with the General Population.” SSM - Population Health 3: 487–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obama Barack. (2017). “The President’s Role in Advancing Criminal Justice Reform.” Harvard Law Review 130(3): 811–865. [Google Scholar]

- Pager Devah. (2003). “The Mark of a Criminal Record.” American Journal of Sociology 108(5): 937–975. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2007). Marked: Race, Crime, and Finding Work in an Era of Mass Incarceration. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson Evelyn J. (2010). “Incarcerating Death: Mortality in U.S. State Correctional Facilities, 1985–1998.” Demography 47(3): 587–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I. (1989). “The Sociological Study of Stress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 30(3): 241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersilia Joan. (2003). When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit Becky. (2012). Invisible Men: Mass Incarceration and the Myth of Black Progress. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit Becky, and Sykes Bryan. (2017). “Incarceration.” In The State of the Union: The Poverty and Inequality Report, ed. Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality, special issue, Pathways Magazine. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit Becky, and BruceWestern. (2004). “Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in U.S. Incarceration.” American Sociological Review 69(2): 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Charitable Trusts. (2010). Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility. Washington, DC: Pew Charitable Trusts. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps Michelle S. (2017). “Mass Probation: Toward a More Robust Theory of State Variation in Punishment.” Punishment & Society 19(1): 53–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter Nicole D. (2010). Expanding the Vote: State Felony Disenfranchisement Reform, 1997–2010. Washington, DC: Sentencing Project. [Google Scholar]

- Pridemore William A. (2014). “The Mortality Penalty of Incarceration: Evidence from a Population-Based Case-Control Study.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 55(2): 215–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers Anke, Apel Robert, Nieuwbeerta Paul, Dirkzwager Anja, and Wilsem Johan. (2014). “Imprisonment Length and Post-Prison Employment Prospects.” Criminology 52(3): 499–527. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael Steven. (2011). “Incarceration and Prisoner Reentry in the United States.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 635(1): 192–215. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen David L., Schoenbach Victor J., and D avid A. Wohl. (2008). “All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Among Men Released from State Prison, 1980–2005.” American Journal of Public Health 98(12): 2278–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen David L., Wohl David A., and Schoenbach Victor J.. (2011). “All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Among Black and White North Carolina State Prisoners, 1995–2005.” Annals of Epidemiology 21(10): 719–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J., and Loeffler Charles. (2010). “Punishment’s Place: The Local Concentration of Mass Incarceration.” Daedalus 139(3): 20–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J., Raudenbush Stephen W., and Earls Felton. (1997). “Neighborhoods and Violence Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy.” Science 277(5328): 918–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapiro Virginia. (2004). “Not Your Parents’ Political Socialization: Introduction for a New Generation.” Annual Review of Political Science 7(1): 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker Jason, and John Andrea. (2007). “Enduring Stigma: The Long-Term Effects of Incarceration on Health.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48(2): 115–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentencing Project. (2014a). Poverty and Opportunity Profile: Americans with Criminal Records. Washington, DC: Sentencing Project. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2014b). Felony Disenfranchisement. Washington, DC: Sentencing Project. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon Sarah K. S., Uggen Christopher, Schnittker Jason, Thompson Melissa, Wakefield Sara, and Massoglia Michael. (2017). “The Growth, Scope, and Spatial Distribution of People with Felony Records in the United States, 1948–2010.” Demography 54(5): 1975–1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart Forest. (2016). Down, Out, and Under Arrest: Policing and Everyday Life on Skid Row. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sunshine Jason, and Tyler Tom R.. (2003). “The Role of Procedural Justice and Legitimacy in Shaping Public Support for Policing.” Law & Society Review 37(3): 513–548. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes Bryan L., and Maroto Michelle. (2016). “A Wealth of Inequalities: Mass Incarceration, Employment, and Racial Disparities in U.S. Household Wealth, 1996 to 2011.” Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 2(6): 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes Bryan L., and Pettit Becky. (2014). “Mass Incarceration, Family Complexity, and the Reproduction of Childhood Disadvantage.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 654(1): 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2015). “Severe Deprivation and System Inclusion Among Children of Incarceration Parents in the United States After the Great Recession.” Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 1(2): 108–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jeremy Travis, Western Bruce, and Reburn F. Stephen, eds. (2014). The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler Tom R. (2003). “Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and the Effective Rule of Law.” Crime and Justice 30: 283–357. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler Tom R., Fagan Jeffrey, and Geller Amanda. (2014). “Street Stops and Police Legitimacy: Teachable Moments in Young Urban Men’s Legal Socialization.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 11(4): 751–785. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler Tom R., and Huo Yuen J.. (2002). Trust in the Law: Encouraging Public Cooperation with the Police and Courts. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler Tom R., and Wakslak Cheryl J.. (2004). “Profiling and Police Legitimacy: Procedural Justice, Attributions of Motive, and Acceptance of Police Authority.” Criminology 42(2): 253–282. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen Christopher, Larson Ryan, and Shannon Sarah. (2016). 6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, 2016. Washington, DC: Sentencing Project. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen Christopher, and Manza Jeff. (2002). “Democratic Contraction? Political Consequences of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States.” American Sociological Review 67(6): 777–803. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen Christopher, Manza Jeff, and Thompson Melissa. (2006). “Citizenship, Democracy, and the Civic Reintegration of Criminal Offenders.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 605(1): 281–310. [Google Scholar]

- Uggen Christopher, Vuolo Mike, Lageson Sarah, Ruhland Ebony, and Whitman Hilary. (2014). “The Edge of Stigma: An Experimental Audit of the Effects of Low-Level Criminal Records on Employment.” Criminology 52(4): 627–654. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. (1980–2016). Key Statistic: Total Correctional Population. Data from annual reports: Annual Survey of Jails, Census of Jail Inmates, and National Prisoner Statistics Program. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm/dataonline/content/pub/html/scscf04/index.cfm?ty=kfdetail&iid=487. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. (1980–2016). Crime in the United States. Uniform Crime Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.bjs.gov/ucrdata/Search/Crime/State/StatebyState.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. National Cancer Institute. (1969–2017). Download U.S. Population Data. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/download.html. [Google Scholar]

- Vallas Rebecca, Boteach Melissa, West Rachel, and Odum Jackie. (2015). Removing Barriers to Opportunity for Parents with Criminal Records and Their Children: A Two-Generation Approach. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. [Google Scholar]

- Visher Christy A., and Travis Jeremy. (2011). “Life on the Outside: Returning Home After Incarceration.” U.S. Prison Journal 91(3): 102S–119S. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant Loic. (2001). “Deadly Symbiosis: When Ghetto and Prison Meet and Mesh.” Punishment & Society 3(1): 95–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield Sara, and Uggen Christopher. (2010). “Incarceration and Stratification.” Annual Review of Sociology 36: 387–406. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield Sara, and Wildeman Christopher. (2013). Children of the Prison Boom: Mass Incarceration and the Future of American Inequality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver Vesla M., and Lerman Amy E.. (2010). “Political Consequences of the Carceral State.” American Political Science Review 104(4): 817–833. [Google Scholar]

- Western Bruce. (2002). “The Impact of Incarceration on Wage Mobility and Inequality.” American Sociological Review 67(4): 477–498. [Google Scholar]

- –––. (2006). Punishment and Inequality in America. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Western Bruce, and Pettit Becky. (2000). “Incarceration and Racial Inequality in Men’s Employment.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54(1): 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Western Bruce, and Wildeman Christopher. 2009. “The Black Family and Mass Incarceration.” ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 621(1): 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- White Ariel. (2018). “Family Matters? Voting Behavior in Households with Criminal Justice Contact.” Working Paper. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Political Science. https://arwhite.mit.edu/sites/default/files/images/HHs_shortarticleversion_forweb.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman Christopher. (2009). “Parental Imprisonment, the Prison Boom, and the Concentration of Childhood Disadvantage.” Demography 46(2): 265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]