Abstract

Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E is able to grow with glucose as the carbon source in liquid medium with 1% (vol/vol) toluene or 17 g of (123 mM) p-hydroxybenzoate (4HBA) per liter. After random mini-Tn5′phoA-Km mutagenesis, we isolated the mutant DOT-T1E-PhoA5, which was more sensitive than the wild type to 4HBA (growth was prevented at 6 g/liter) and toluene (the mutant did not withstand sudden toluene shock). Susceptibility to toluene and 4HBA resulted from the reduced efflux of these compounds from the cell, as revealed by accumulation assays with 14C-labeled substrates. The mutant was also more susceptible to a number of antibiotics, and its growth in iron-deficient minimal medium was inhibited in the presence of ethylenediamine-di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (EDDHA). Cloning the mutation in the PhoA5 strain and sequencing the region adjacent showed that the mini-Tn5 transposor interrupted the exbD gene, which forms part of the exbBD tonB operon. Complementation by the exbBD and tonB genes cloned in pJB3-Tc restored the wild-type characteristics to the PhoA5 strain.

Toxic compounds are part of the natural environment, and resistance to a wide range of cytotoxic compounds is a common phenomenon in most organisms (37, 38, 58, 59). One strategy for resistance is the use of multidrug transport systems to remove a variety of deleterious compounds in an energy-dependent process which decreases their concentrations inside the cell (50, 58, 59).

Several families of multidrug efflux pumps can be distinguished on the basis of their structure and properties (50, 59). One of them is the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family, found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and other microorganisms (15, 23, 27, 30–33, 39, 48, 50, 59). These efflux pumps contribute to clinically relevant antibiotic resistance and to the removal of organic solvents, dyes, detergents, and heavy metals (50, 59). They consist of three components: an inner membrane translocase efflux protein, an inner membrane-anchored periplasmic lipoprotein, and an outer membrane protein that spans the periplasm and forms a channel (18, 24). Examples of such pumps are AcrAB-TolC in E. coli (31, 32), MexAB-OprM in P. aeruginosa (39, 55, 56), and TtgABC in Pseudomonas putida (43).

P. putida DOT-T1E is characterized by its innate resistance to toluene (it can grow in the presence of 1% [vol/vol] toluene) and p-hydroxybenzoate (4HBA) (it tolerates up to 30 g/liter). Although tolerance to these compounds also involves changes that reduce permeability to the drugs (19, 51), it is now clear that several RND efflux pumps play a critical role in tolerance to these chemicals. For example, three efflux pumps of the RND family contribute to tolerance to toluene (35, 43, 44, 47). Two of these pumps also expel antibiotics (27).

The ionophore carbonylcyanide 4-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) compromises the removal of drugs by RND efflux pumps, which suggests that the energy required for the process is provided by coupling with the proton motive force across the inner membrane (45, 50, 57). However, the molecular basis for this coupling is unknown. To shed light on this process, we searched for mutants with increased susceptibility to different drugs and which were affected in a gene that codes for a protein that was not a component of the efflux machinery. After mini-Tn5 mutagenesis, we isolated a P. putida DOT-T1E mutant susceptible to 4HBA and antibiotics as well as to toluene. The mutation affects the energy-transducing TonB system of the solvent-tolerant strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. putida | ||

| DOT-T1E | Rifr Tolr 4HBAr | 42 |

| DOT-T1E-PhoA5 | DOT-T1E exbD::mini-Tn5-′phoA 4HBAs Tols | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5αF′ | F−hsdR17 thi-1 recA1 | 49 |

| CC118λpir | Lysogenized with λpir phage | 11 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUT/mini-Tn5phoA | Apr KmroriR6K oriTRP4, promoter-probe transposon containing the ′phoA gene | 11 |

| pUC18 | AproriColE1 rop, MCS, Plac promoter fused to the α peptide of LacZ | 49 |

| pJB3Tc19 | Apr TcroriVRK2 oriTRK2, α complementation, MCS | 5 |

| pPAT2 | Apr, pUC18 carrying the Kmr gene plus a 4.5-kb NotI/SphI chromosomal fragment from P. putida DOT-T1E (′exbD/tonB) | This study |

| pPAT5 | Apr, pUC18 carrying a 4-kb PstI chromosomal fragment from P. putida DOT-T1E bearing the exbBD and tonB genes | This study |

| pPAT7 | Apr Tcr, the 4-kb PstI fragment of pPAT5 was cloned at the same site in pJB3Tc19 | This study |

| pRK600 | Cmr, helper plasmid, oriColE1 mobRK2 traRK2 | 11 |

Apr, Cmr, Rifr, and Tcr, resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, rifampin, and tetracycline, respectively; MCS, multicloning sites; 4HBAs and 4HBAr, strains unable (s) or able (r) to grow in the presence of 10 g of 4HBA per liter; Tolr and Tols, toluene-tolerant and toluene-sensitive strains, respectively.

Culture media and growth conditions.

E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. P. putida cells were grown on LB medium or on modified M9 minimal medium (1) with glucose (0.5%, wt/vol). When iron-limited conditions were required, MB2 minimal iron-deficient medium (13) was used. To limit the amount of available iron, we added 3 μg of the iron chelator ethylenediamine-di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (EDDHA) per ml. Cultures of P. putida and E. coli were incubated at 30 and at 37°C, respectively, with shaking at 200 strokes per min in a Kühner rotary incubator.

The antibiotics used were as follows: ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), piperacillin (100 μg/ml), rifampin (20 μg/ml), and tetracycline (10 μg/ml).

Assays to test the susceptibilities of P. putida DOT-T1E and its mutants to drugs.

The effect of 4HBA on the growth of P. putida DOT-T1E and its mutants was analyzed on double-diffusion plates as follows: M9 minimal medium agar plates containing 0.5%, wt/vol, glucose and a linear gradient (0 to 20 g/liter) of 4HBA were prepared by the double-diffusion technique (52). Two hundred microliters of an exponential-growth-phase culture (turbidity at 660 nm between 0.8 and 1 U) was spread on plates and incubated for 36 h at 30°C. The inhibitory concentration of the test compound was the lowest concentration that prevented cell growth.

To test tolerance of P. putida to 4HBA in liquid medium, 30 ml of M9 minimal medium with glucose containing between 0 and 20 g of 4HBA per liter was inoculated with 0.3 ml of an overnight bacterial culture. Growth was then determined by counting the number of CFU per milliliter of culture.

The halo inhibition test was used to investigate susceptibility to antibiotics. Antibiotics were supplied on 6-mm-diameter disks at the following concentrations: ciprofloxacin (5 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), and imipenem (10 μg). The disks were laid on M9 minimal medium agar plates (with glucose as the C source) that have been spread with 200 μl of an overnight culture. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 30°C, and the inhibition halo was measured.

Sudden toluene shock assays were done as described by Ramos et al. (43). Briefly, P. putida DOT-T1E and its mutants were cultured in LB medium with toluene supplied or not supplied through the gas phase. When the culture reached the mid-log phase (turbidity around 0.8 at 660 nm), toluene to reach 0.3% (vol/vol) was added. The number of CFU per ml before and after addition of toluene was determined.

14C accumulation assays.

The incorporation of [14C]toluene was studied in mid-log-phase cells (turbidity at 660 nm, ∼0.8) grown in LB medium and preexposed or not preexposed to toluene supplied via the gas phase. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed in LB medium, and then suspended in 4 ml of LB medium to a turbidity at 660 nm of about 3. The cells were then incubated for 10 min at 30°C with shaking, and 4 μCi of [14C]-toluene (120 μCi/μmol) was added to reach a sublethal toluene concentration of 0.075% (vol/vol). Aliquots of 400 μl were withdrawn at intervals, filtered through Millipore type HA 0.45-μm-pore-size filters, and washed with 1 ml of LB medium. 14C associated with cell material was measured with a scintillation counter (Packard Radiometer). For study of the incorporation of [14C]4HBA, cells were grown on M9 minimal medium with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose as the C source in the absence and in the presence of 5 mM 4HBA. Cells were treated as described above for toluene assays, except that we added 1.5 μCi of [14C]4HBA (specific activity, 11.5 mCi/mmol) and filters were washed with 5 mM 4HBA-supplemented M9 medium.

Alkaline phosphatase assays.

Alkaline phosphatase activity was determined as described before (19).

Recombinant DNA techniques and analysis.

Preparation of chromosomal and plasmid DNA, DNA digestion with restriction endonucleases, and agarose gel electrophoresis were done by standard methods (3, 49). Electrotransformation of E. coli or P. putida cells, prepared according to the method of Cornish et al. (9), was done with a Gene Pulser apparatus according to the instruction manual. Southern blotting was done as reported by Sambrook et al. (49) using DNA probes amplified by PCR in a Gene Amp PCR 2400 system with appropriate primers and labeled with digoxigenin-dUTP. Both strands of DNA were sequenced by the dideoxy sequencing method, using an ABIPrism dRhodamine terminator kit (Applied Biosystems).

RNA preparation and RT-PCR.

We isolated total RNA from P. putida DOT-T1E according to the RNEasy protocol (Qiagen, GmbH). Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assays were done with the Titan One Tube RT-PCR System. We used the pairs of primers I (5′-AAGGCACAGGTGTCCGAT-3′) and II (5′-CAGCAGCACCAGCATCAC-3′) and III (5′-GATTACGGCGACCTGATG-3′) and IV (5′-TACCGACCAGTTGAGCGT-3′) to determine the contiguity of mRNA that contained the exbB-exbD and exbD-tonB genes.

Isolation of 4HBA-sensitive Tn5′phoA mutants of P. putida DOT-T1E.

Matings involving P. putida DOT-T1E as the recipient, E. coli CC118λpir (pUT/mini-Tn5-′phoA, pRK600) as the donor, and HB101 (pRK600) as the helper strain were done as described previously (11). We obtained about 2,000 Tn5 transconjugants, of which about 15% of the kanamycin-resistant (Kmr) clones appeared as blue colonies on M9 minimal medium plates with glucose and supplemented with 100 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate per ml. This process guaranteed that no auxotrophic mutants were selected. The blue Kmr transconjugants were tested for their ability to grow on the same minimal medium but with 6 g of 4HBA per liter. One of them, which we called P. putida DOT-T1E-PhoA5, failed to grow under such conditions and was selected for further assays.

Cloning of the mutation in P. putida DOT-T1E-PhoA5 and analysis of the surrounding DNA sequence.

To determine the site of insertion of mini-Tn5-′phoA-Kmr in the mutant DOT-T1E-PhoA5, total DNA was digested with SphI. This enzyme cuts 5′ with respect to the Kmr gene within the phoA-Kmr cassette (46), so that DNA downstream from the kanamycin marker can be recovered after ligation to pUC18 DNA as Kmr colonies. Ten micrograms of the SphI-digested total DNA from the P. putida DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant was ligated to the unique SphI site of pUC18. Kmr clones were selected after transformation in E. coli DH5αF′ cells. This yielded plasmid pAT2 containing an SphI insert of about 6 kb (1.7 kb corresponding to the kanamycin cassette and 4.3 kb of Pseudomonas chromosomal DNA). The P. putida DNA was sequenced by using the M13 universal primer and a primer located at the end of the mini-Tn5 transposon. Both strands were subsequently sequenced with primers designed on the basis of the obtained sequence.

Rescue of wild-type P. putida DOT-T1E genes from a gene bank.

A P. putida DOT-T1E chromosomal library prepared in pUC18 after digestion with PstI was used to rescue wild-type genes after colony—screening hybridization with appropriate gene probes as described before (12).

Computer analysis.

Open reading frames (ORFs) in the DNA sequences were predicted using the DNA Strider 1.1 program. To detect amino acid sequence similarities in sequences deposited at GenBank, we used the BLAST program (2).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence corresponding to the P. putida DOT-T1E chromosomal fragment that contained the exbBD tonB operon has been deposited in GenBank under accession number AF315582.

RESULTS

Isolation and physiological characterization of a phoA mutant of P. putida DOT-T1E with altered sensitivity to 4HBA.

We generated mini-Tn5-′phoA insertion mutants of P. putida DOT-T1E. About 300 Kmr PhoA+ transconjugants were tested for increased sensitivity to 4HBA, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, imipenem, and toluene. A single mutant, DOT-T1E-PhoA5, consistently showed increased sensitivity to these drugs.

For example, on double-diffusion solid M9 minimal medium with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose and a 4HBA gradient between 0 and 20 g/liter, the mutant strain grew only at a concentration of 4HBA below 6 g/liter, in contrast with the wild type, which grew well up to concentrations of about 15 to 17 g/liter.

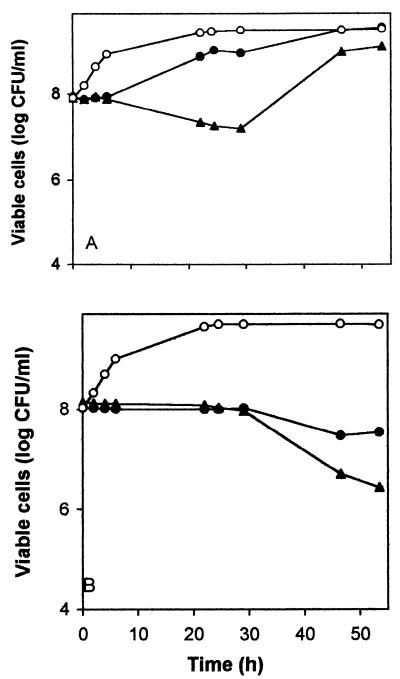

We also tested the effect of 4HBA on cells growing exponentially in liquid M9 minimal medium with glucose. When the cell density of the culture was around 8 ± 1 × 107 CFU/ml, the culture was split into three aliquots to which 4HBA was added to 0, 9, and 12 g/liter. For the wild-type strain (Fig. 1A), 9 g of 4HBA per liter delayed growth by about 5 h, after which growth ensued and the cultures reached a high cell density. With 12 g of 4HBA per liter, the number of CFU per milliliter initially decreased and only after 24 h did growth resume. For the mutant strain (Fig. 1B), 9 and 12 g of 4HBA per liter blocked growth and viability declined after 30 h of incubation (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Response of P. putida DOT-T1E and DOT-T1E-PhoA5 to sudden 4HBA shock. Wild-type (A) and mutant (B) cells were pregrown overnight on M9 minimal medium with glucose and then diluted 50-fold in the same medium. Four hours later the cultures were split into three aliquots to which 0 (○), 9 (●), or 12 (▴) g of 4HBA per liter was added. At the indicated times, the number of viable cells was determined by spreading serial dilutions on M9 minimal medium with glucose as the sole C source. The figure shows the results of a representative assay chosen from among five independent assays.

We tested the susceptibility of P. putida DOT-T1E and DOT-T1E-PhoA5 to cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, and imipenem. Both strains were sensitive to these antibiotics; however, the inhibition halo produced by the mutant strain was about twofold larger than that for the wild type (12, 14, and 26 mm for ciprofloxacine, cefotaxime, and imipenem, respectively).

We studied the tolerance of P. putida DOT-T1E and its mutant DOT-T1E-PhoA5 to organic solvents in liquid LB medium. Exponentially growing cells were exposed to the following solvents (partition coefficient in an octanol-water mixture [log Pow]) at 0.3% (vol/vol): propylbenzene (log Pow = 3.6), p-xylene (log Pow = 3.0), and toluene (log Pow = 2.5). Except for toluene, to which the mutant was sensitive, both strains tolerated these solvents, as shown by a turbidity above 1.5 in all cases after 24 h of incubation (data not shown).

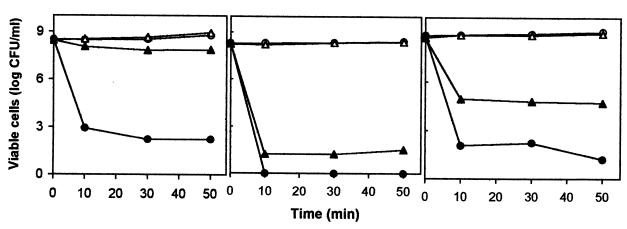

Previous studies have shown that preadaptation to toluene supplied via the vapor phase plays a key role in toluene tolerance in P. putida DOT-T1E (43, 45). Sudden exposure of (nonpreexposed) wild-type cells to toluene led to a marked loss of viability (5 orders of magnitude), whereas about 50 to 90% of the preexposed cells tolerated the shock (Fig. 2A). The DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant strain was more sensitive than the wild type to toluene shock, and the number of CFU per milliliter after the toluene shock was below our detection limit (10 CFU/ml) (Fig. 2B). Because we saw no growth after incubation overnight, we surmised that no viable cells were left after the shock. The viability of cells of P. putida DOT-T1E-PhoA5 preexposed to toluene was seriously compromised upon sudden toluene shock, and only about 1 in 106 cells survived (Fig. 2B). The survival of the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant following toluene shock was similar to that reported for mutants of this strain lacking either the ttgABC or the ttgGHI toluene efflux pump (43, 47).

FIG. 2.

Short-term survival after toluene shock in DOT-T1E (A), DOT-T1E-PhoA5 (B), and DOT-T1E-PhoA5(pPAT7) (C) cells. Bacterial cells were pregrown overnight on minimal medium with glucose as the sole C source. The cultures were then diluted 50-fold in the same medium in the absence (circles) and in the presence (triangles) of toluene supplied via the gas phase. When cultures reached a turbidity of about 1, they were split into halves, one of which was challenged with 0.3% (vol/vol) toluene (solid symbols) and the other of which was kept as a control (open symbols). At the indicated times, the numbers of CFU per milliliter were determined. The results are averages of the results of three independent assays, with standard deviations being in the range of 5% of the given values.

The mini-Tn5 insertion in DOT-T1E-PhoA5 did not result in major outer membrane damage but led to nonfunctional efflux pumps.

We previously generated an OprL mutant of P. putida with an altered outer membrane surface that leaked periplasmic proteins and which was more sensitive than the parental strain to toluene and antibiotics (45). To determine if the above phenotypic characteristics of P. putida DOT-T1E-PhoA5 were due to general damage in the outer membrane, we analyzed preparations of wild-type and DOT-T1E-PhoA5 cells under scanning electron microscopy. Both the wild-type and the mutant cells had a smooth surface, and no obvious differences were observed (not shown). We also transformed DOT-T1E and DOT-T1E-PhoA5 with plasmid pJB3-Tc19, which produces periplasmic β-lactamase, and used Western blotting to determine whether β-lactamase was released to the culture medium (30). No β-lactamase was found in the culture supernatants of the wild type or the mutant strains (not shown). These results suggested that the increased sensitivity of DOT-T1E-PhoA5 to certain drugs was not the result of general defects in the outer membrane.

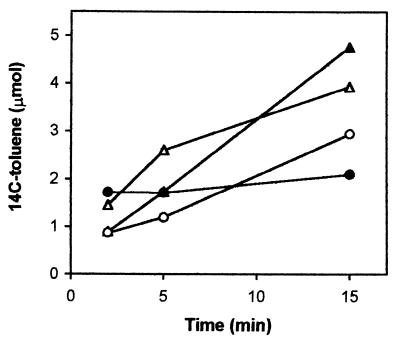

We then tested whether functioning of the efflux pumps for toluene and 4HBA extrusion was compromised in the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 strain. The physiological characterization of DOT-T1E-PhoA5 revealed that this strain cannot use 4HBA as the sole C source. For this reason, in the assays with 4HBA we used as a control strain DOT-T1E-PobA (45), a mutant unable to metabolize 4HBA. In the assays with toluene we used a DOT-T1E derivative, DOT-T1EΔtodC (36), unable to metabolize toluene. P. putida cells were grown in the absence of aromatic compounds or in the presence of sublethal concentrations of 4HBA (5 mM) or toluene (supplied via the gas phase). We found that, regardless of the growth conditions, accumulation of toluene in DOT-T1E-PhoA5 took place at a higher rate than in the control DOT-T1E-ΔtodC strain (Fig. 3). This was particularly evident with preinduced cells: while the level of toluene in control cells remained relatively stable, the toluene concentration in the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 cells increased steadily with time. The DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant also accumulated higher amounts of [14C]4HBA than did the control strain: 200 nmol per U of cell turbidity per min for the mutant strain versus about 15 nmol per U of cell turbidity per min in the control strain. These results suggest that the functioning of the extrusion system was impaired in the mutant DOT-T1E-PhoA5 strain.

FIG. 3.

Accumulation of toluene in P. putida DOT-T1E-ΔtodC and DOT-T1E-PhoA5. P. putida DOT-T1E-ΔtodC (circles) and DOT-T1E-PhoA5 (triangles) cells were grown in LB medium in the absence (open symbols) or presence (filled symbols) of toluene supplied in the gas phase. Cells were then treated as described under Materials and Methods. Shown are the results of a representative assay chosen from among three independent assays.

Site of the mutation in P. putida DOT-T1E-PhoA5.

DNA carrying the mutation in P. putida DOT-T1E-PhoA5 was cloned in pPAT2 as described in Materials and Methods. Plasmid pPAT2 bore a 6-kb insert containing the Kmr gene and a 4.3-kb P. putida sequence downstream from the mini-Tn5 transposon. Sequence analysis revealed that the site of insertion was an ORF that encoded a protein homologous to the ExbD protein of P. putida WCS358 (Table 2). The 4.5-kb NotI/SphI fragment of pPAT2 was used as a probe against total DNA from P. putida DOT-T1E digested with different restriction enzymes. A unique 4-kb PstI fragment that hybridized in Southern blotting was cloned into pUC18 to generate plasmid pPAT5, which was used to sequence the DNA flanking exbD.

TABLE 2.

Identities of P. putida DOT-T1E ExbBD, ExbD, and TonB amino acid sequences with other proteins from the databasesa

| Protein | Organism (accession no.) | % Identitya | Protein length (amino acids) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ExbB | P. putida (X70139) | 90.0 (329) | 329 |

| ExbB | E. coli (M28819) | 62.0 (234) | 244 |

| ExbB | X. campestris (Z95386) | 45.7 (92) | 253 |

| ExbB | P. aeruginosa (AF190125) | 34.8 (181) | 239 |

| ExbD | P. putida (X70139) | 97.9 (142) | 142 |

| ExbD | E. coli (U28377) | 64.8 (142) | 141 |

| ExbD | P. aeruginosa (AF190125) | 39.0 (118) | 133 |

| ExbD1 | X. campestris (Z95386) | 31.8 (129) | 140 |

| TonB | P. putida (X70139) | 93.8 (243) | 243 |

| TonB2 | P. aeruginosa (AF190125) | 36.6 (224) | 270 |

| TonB | X. campestris (Z95386) | 32.5 (154) | 223 |

| TonB1 | P. aeruginosa (U23764) | 32.2 (236) | 342 |

| TonB | E. coli (U24206) | 29.6 (206) | 244 |

Detected with the BLOSUM50 matrix at the ALIGN Query, using sequence data on the GENESTREAM network server, IGH, Montpellier, France (http: //vega.igh.cnrs.fr/bin/lalign-guess.cgi). Numbers in parentheses are the numbers of amino acids that overlap.

Analysis of the DNA revealed three ORFs of 963, 429, and 732 bp. All three ORFs started with an ATG and were preceded by potential ribosome-binding AGGA sequences (36). Hybridization of each of the ORFs (amplified with appropriate primers) against total chromosomal DNA revealed a single band in each case, suggesting that P. putida DOT-T1E has single copies of the exbB, exbD, and tonB genes. Blast analysis of the gene cluster against the genome sequence of P. putida KT2440, a strain closely related to DOT-T1E, revealed a single copy of each of the genes in the genome of this strain. An extra copy of the tonB allele was found in P. aeruginosa (60). However, no homologous sequence to this tonB gene was found in the genome of P. putida KT2440. The data bank sequence that showed the most extensive identity (90 to 98%) with these three ORFs was the exbBD tonB cluster of P. putida WCS358 (4). The ExbB, ExbD, and TonB proteins showed a high degree of identity with the corresponding proteins from P. aeruginosa (40, 61), E. coli K-12 (41), Xanthomonas campestris (54) (Table 2), and all other gram-negative bacteria in the database (not shown).

The deduced P. putida DOT-T1E ExbB, ExbD, and TonB proteins were 33.3, 15.4, and 26.1 kDa, respectively. Of the three, ExbD and TonB were similar in size to the proteins reported for other microorganisms (Table 2). However, the P. putida DOT-T1E ExbB protein, as in P. putida WCS358, had an extra 90 residues at its amino terminus. The functional significance of this N-terminal extension is unknown, and no homology between this domain and known proteins was identified in the GenBank database.

The exbB, exbD, and tonB genes are likely part of an operon.

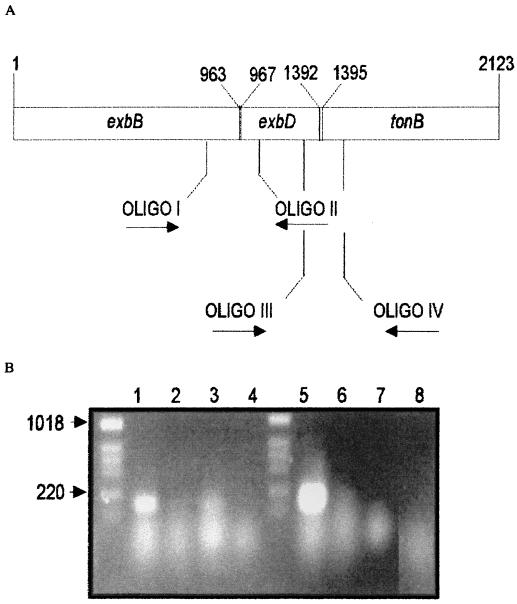

Sequence analysis suggested that the exbB, exbD, and tonB genes may form an operon based on the close proximity of the end of the exbB gene and the start site of the exbD gene (only 3 bp away) and the overlap between exbD and tonB (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Organization of the exbB, exbD, and tonB genes in P. putida DOT-T1E. (A) Localization of the ORFs and positions of the primers used for mRNA amplification in RT-PCR assays. Numbers refer to the first A of the first ATG in each gene (positions 1, 967, and 1395) and the last nucleotide of the corresponding stop codon (positions 963, 1392, and 2123). (B) Gel electrophoresis of the cDNA amplified with oligonucleotides I and II for exbB and exbD genes in P. putida DOT-T1E (lane 1) and the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant (lane 3). Lanes 2 and 4 are negative-control samples. cDNAs amplified with oligonucleotides (OLIGO) III and IV in P. putida DOT-T1E and the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant are shown in lanes 5 and 7, respectively, and negative-control samples are shown in lanes 6 and 8. Negative controls contained the same amounts of RNA, primers, and Taq polymerase as the other samples but no avian myeloblastosis virus-reverse transcriptase.

To determine whether the exbB, exbD, and tonB genes in P. putida DOT-T1E could be cotranscribed in a single transcriptional unit, we did amplification assays using RT-PCR and appropriate primers (Fig. 4B). The results for wild-type P. putida DOT-T1E revealed that exbB and exbD are part of the same transcript as exbD and tonB (Fig. 4B). In the PhoA5 mutant, a transcript coded by the exbB and exbD genes, but not that coded by exbD and tonB, could be amplified, as expected from the location of mini-Tn5′ phoA at the 3′ end of the exbD gene (Fig. 4B).

Growth of DOT-T1E-PhoA5 was impaired in the presence of the EDDHA iron chelator.

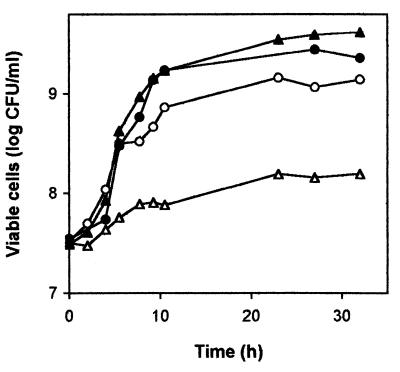

The finding that sensitivity to 4HBA, certain antibiotics, and toluene in P. putida DOT-T1E involved the TonB system prompted us to test whether the mutant DOT-T1E-PhoA5 was impaired in iron uptake (8, 16, 21, 25, 26). We tested whether the presence of the iron chelator EDDHA (used at 8 μM) (4, 53) affected growth in MB2 minimal iron-limited medium with glucose (13). The P. putida DOT-T1E wild-type strain grew under these culture conditions, whereas the growth of the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant strain was severely inhibited in the presence of EDDHA (Fig. 5). Growth was restored when 6 μg of Fe-citrate (Fig. 5) or FeCl3 (not shown) per ml was added to the medium. These results indicated that iron uptake was impaired in the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant strain. We then tested the expression of the exbBD tonB operon by measuring alkaline phosphatase activity in DOT-T1E-PhoA5. In the iron-limited medium, alkaline phosphatase activity was 10-fold higher than in the iron-rich medium (not shown). The response of DOT-T1E-PhoA5 to 4HBA was examined on double-diffusion plates containing 10 times as much iron (60 μg/ml) as in the previous assay. However, the iron surplus had no effect on the 4HBA tolerance of the mutant or the wild-type strain. We also tested tolerance to sudden toluene shocks in liquid medium and sensitivity to ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime, and imipenem in the halo inhibition disk test with the wild-type and the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant strains with 10 times more iron in the medium. The results obtained were not significantly different from those reported above with lower iron in the medium (not shown). We concluded that iron deficiency was not responsible for the sensitivity of the mutant strain to 4HBA, toluene, and antibiotics.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of growth of P. putida DOT-T1E and its derivative DOT-T1E-PhoA5 by the iron chelator EDDHA. P. putida DOT-T1E (circles) and the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant strain (triangles) were grown overnight in MB2 minimal iron-deficient medium. Cultures were diluted 50-fold in the same medium supplemented with 3 μg of EDDHA (open symbols) per ml or with 6 μg of Fe-citrate (filled symbols) per ml. Growth was determined at the indicated times. The figure shows the results of a representative assay chosen from among three independent assays.

Complementation of the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant strain with the exbBD tonB cluster.

The 4-kb PstI insert in pPAT5, carrying the exbBD tonB cluster of DOT-T1E, was subcloned in the broad-host-range plasmid pJB3-Tc (5) to yield pPAT7. The DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant bearing plasmid pPAT7 recovered the ability to tolerate concentrations of 4HBA, ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime, and imipenem similar to those tolerated by the wild type on double—diffusion plates (not shown). The growth rate of the complemented strain in MB2 minimal medium was also similar to that of the wild-type strain (not shown). The pPAT7 plasmid reduced the susceptibility of DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant cells (both cells previously exposed to toluene and noninduced cells) to sudden toluene shock (Fig. 2C).

DISCUSSION

P. putida DOT-T1E has the unusual ability to grow well in the presence of 1% (vol/vol) toluene (42); moreover, it is able to tolerate high concentrations of 4HBA and certain antibiotics. Our study shows that insertion of a mini-Tn5′ phoA transposon within the exbD gene, which probably forms part of an operon with the exbB and tonB genes in this strain, leads to increased susceptibility to these chemicals and deficient iron acquisition. Each of the genes of the exbBD tonB cluster is present in a single copy in the chromosome of P. putida DOT-T1E, which contrasts with the fact that two copies of the tonB gene are present in the genome of P. aeruginosa (60).

The TonB system is an energy transduction complex that consists of the ExbB, ExbD, and TonB proteins, which deliver energy from the cytoplasmic membrane to the outer membrane (7, 20, 22, 28, 34, 50). This system was first identified in E. coli, in which bulky nutrients such as siderophores and vitamin B12, which exceed the diffusion limit of the outer membrane porins, are imported through high-affinity receptors that translocate them into the periplasm. During this process, a 1,000-fold concentration gradient is established across the outer membrane (6, 7, 10). Our results showed that the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant was unable to grow in a low-iron medium when the EDDHA chelator was added. This finding supports the hypothesis that the TonB system also participates in iron uptake by P. putida DOT-T1E. The sensitivity of P. putida DOT-T1E-PhoA5 to 4HBA, toluene, ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime, and imipenem was not compromised by impaired iron acquisition, as shown by the fact that, under conditions of excess iron (which did not limit cell growth), the mutant strain was as sensitive to these antibiotics, 4HBA, and toluene as when the assay was done in a low-iron medium. This finding suggests that the mutation in the TonB system is directly or indirectly responsible for the phenotype we observed.

Increased sensitivity to toluene and 4HBA seems to be the result of the limited removal of these aromatic compounds by specific efflux pumps, as suggested by the accumulation of these drugs in cell membranes. In P. putida DOT-T1E, toluene and certain antibiotics are removed through a series of RND efflux pumps that are highly homologous to the MexAB-OprM pump (about 75% identity) (15, 29, 35, 43 44, 47). Our finding that the mutant strain DOT-T1E-PhoA5 accumulated two- to three-fold as much [14C]-toluene as the solvent-tolerant DOT-T1E-ΔtodC strain (Fig. 3) showed that operation of the RND toluene efflux pumps was compromised. Furthermore, although preinduction of efflux pumps in the wild-type strain with low toluene concentrations led to a lower accumulation of [14C]-toluene in the cells, in agreement with previous observations (44), this did not occur in the mutant strain, indicating impaired operation of the constitutive TtgABC efflux pump and the inducible TtgDEF and TtgGHI pumps. No direct evidence for the involvement of RND efflux pumps in 4HBA tolerance is available at present (45), but the fact that the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant accumulated 20 times as much [14C]4HBA as the control strain DOT-T1E-PobA suggested that at least one efflux system was involved in the exclusion of this aromatic carboxylic acid and that the operation of this system was compromised in the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 mutant strain. Because toluene is more toxic to cells than 4HBA, it was not surprising that only a doubling of the accumulation of toluene was toxic, whereas for 4HBA to become toxic, the increase in accumulation needed to be 1 order of magnitude higher.

In P. aeruginosa, intrinsic antibiotic resistance is afforded in part by a multidrug efflux pump belonging to the RND family and encoded by the mexAB-oprM operon (14, 29, 33, 40, 41). In this operon oprM encodes an outer membrane (14, 29, 33, 41) channel-forming protein which is thought to participate in the export of antibiotics across the outer membrane (24, 56), and the MexA and MexB proteins form part of the translocase complex. A tonB mutant of P. aeruginosa was more susceptible than the wild-type strain to a wide variety of antibiotics (60), a phenotype reminiscent of mutants defective in the mexAB-oprM antibiotic efflux operon. The increased sensitivity of P. putida DOT-T1E to ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime, and imipenem could be ascribed to impaired efflux of these compounds by RND efflux pumps. In fact, the TtgABC and TtgGHI pumps are able to extrude β-lactam antibiotics in addition to solvents (12).

How might the TonB system participate in the efflux of solvents and other drugs?

Studies of the uptake of siderophores have suggested that TonB not only opens the corresponding receptor channel but also helps to dissociate the siderophore receptor complex to allow import (26). Therefore, TonB seems to behave as a regulating protein that influences the conformation of another protein (26). In addition, operation of the system requires proper stoichiometry of the ExbB, ExbD, and TonB proteins (41). Based on these findings several hypotheses might explain the participation of the TonB system in drug exclusion. One is that an imbalance in ExbD production in the DOT-T1E-PhoA5 strain may interfere with the incorporation of inner membrane components of the RND pumps in the cytoplasmic membrane, making the pumps nonfunctional. Another possibility is that members of the RND family of pumps are activated through the TonB system. Any of the elements of the efflux pumps could be the target for the TonB system. Although TonB proteins are generally involved in uptake across the outer membrane, a TonB-like protein identified in Aeromonas hydrophila was suggested to play a role in the energy-dependent export of exotoxin aerolysin (17). The three-dimensional structure of TolC, which forms part of the AcrAB-TolC pump in E. coli, was recently elucidated (24). Three TolC proteins assemble to form a continuous, solvent-accessible conduct that spans both the outer membrane and the periplasmic space. The periplasmic or proximal end of the tunnel is sealed by sets of coiled helices, and it was suggested that they could be untwisted by an allosteric mechanism mediated by protein-protein interactions (24). The TonB system may, directly or indirectly, be involved in this type of allosteric mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from DuPont de Nemours.

We thank Arie Ben-Bassat and N. Ornston for illuminating discussions and K. Shashok for checking the use of English in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abril M A, Michán C, Timmis K T, Ramos J L. Regulator and enzyme specificities of the TOL plasmid-encoded upper pathway for degradation of aromatic hydrocarbons and expansion of the substrate range of the pathway. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6782–6790. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.12.6782-6790.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular microbiology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitter W, Tommassen J, Weisbeek P J. Identification and characterization of the exbB, exbD and tonB genes of P. putida WCS358: their involvement in ferric-pseudobactin transport. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:117–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blatny J M, Brautaset T, Winther-Larsen H C, Haugan K, Valla S. Construction and use of a versatile set of broad-host-range cloning and expression vectors based on the RK2 replicon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:370–379. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.370-379.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradbeer C. The proton motive force drives the outer membrane transport of cobalamin in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3146–3150. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.3146-3150.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun V. Energy-coupled transport and signal transduction through the gram-negative outer membrane via TonB-ExbB-ExbD-dependent receptor proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;16:295–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadieux N, Bradbeer C, Kadner R J. Sequence changes in the TonB box region of BtuB affects its transport activities and interactions with TonB protein. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5954–5961. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.5954-5961.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornish E C, Beckham S A, Madox J F. Electroporation of freshly plated Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells. Benchmarks. 1998;25:955–958. doi: 10.2144/98256bm05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crosa J H. Signal transduction and transcriptional and posttranscriptional control of iron-regulated genes in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:319–336. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.319-336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duque E, Segura A, Mosqueda G, Ramos J L. Global and cognate regulators control expression of the organic solvent efflux pumps TtgABC and TtgDEF of pseudomonas putida. Mol Microbiol. 2000;39:1100–1106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilleland H E, Jr, Stinnett J D, Eagon R G. Ultrastructural and chemical alteration of the cell envelope of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, associated with resistance to ethylenediaminetetraacetate resulting from growth in a Mg2+-deficient medium. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:302–311. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.1.302-311.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotoh N, Tsujimoto H, Poole K, Yamagishi J, Nishino T. The outer membrane protein OprM of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is encoded by oprK of the mexA-mexB-oprK multidrug resistance operon. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2567–2569. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagman K E, Pan W, Spratt B G, Balthasar J T, Judd R C, Shafer W M. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to antimicrobial hydrophobic agents is modulated by the mtrRCDE efflux system. Microbiology. 1995;141:611–622. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-3-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgs P I, Myers P S, Postle K. Interactions in the TonB-dependent energy transduction complex: ExbB and ExbD forms homomultimers. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6031–6038. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.6031-6038.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard S P, Meiklejohn H G, Shivak D, Jahagirdar A TonB-like protein and a novel membrane protein containing an ATP-binding cassette function together in exotoxin secretion. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:595–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson J M, Church G M. Alignment and structure prediction of divergent protein families: periplasmic and outer membrane protein of bacterial efflux pumps. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:695–715. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junker F, Ramos J L. Involvement of the cis/trans isomerase Cti in solvent resistance of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5693–5700. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5693-5700.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadner R J. Vitamin B12 transport in Escherichia coli: energy coupling between membranes. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2027–2033. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadner R J, Keller K J. Mutual inhibition of cobalamin and siderophore uptake systems suggests their competition for TonB function. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4829–4835. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4829-4835.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson M, Hannavy K, Higgins C F. ExbB acts as a chaperone-like protein to stabilize TonB in the cytoplasm. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Köhler T, Epp S F, Curty L, Pechère J-C. Characterization of MexT, the regulator of the MexE-MexF-OprN multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6300–6305. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6300-6305.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koronakis V, Sharff A, Koronakis E, Luisi B, Hughes C. Crystal structure of bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature. 2000;405:914–919. doi: 10.1038/35016007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen R A, Foster-Martnett D, McIntosh M A, Postle K. Regions of Escherichia coli TonB and TepA proteins essential for in vivo physical interactions. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3213–3221. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3213-3221.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen R A, Thomas M G, Postle K. Proton motive force, ExbB and ligand-bound FepA drive conformational changes in TonB. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1809–1824. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazdunski C J, Bouveret E, Rigal A, Journet L, Lloubes R, Benedetti H. Colicin import into Escherichia coli cells. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4993–5002. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.4993-5002.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Letain T E, Postle K. TonB protein appears to transduce energy by shuttling between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:271–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3331703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X Z, Nikaido H, Poole K. Role of mexA-mexB-oprM in antibiotic efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1948–1953. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liesegang H, Lemke K, Siddiqui R A, Schlegel H G. Characterization of the inducible nickel and cobalt resistance determinant cnr from pMOL28 of Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:767–778. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.767-778.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma D, Cook D, Alberti M, Pon N G, Nikaido H, Hearst J E. Molecular cloning and characterization of acrA and acrE genes of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6299–6313. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6299-6313.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma D, Cook D, Alberti M, Pon N G, Nikaido H, Hearst J E. Genes acrA and acrB encode a stress-induced efflux system of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:45–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masuda N, Sakagawa E, Ohya S. Outer membrane proteins responsible for multidrug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:645–649. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moeck G S, Coulton J W. TonB-dependent iron acquisition: mechanisms of siderophore-mediated active transport. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:675–681. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosqueda G, Ramos J L. A set of genes encoding a second toluene efflux system in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E is linked to the tod genes for toluene metabolism. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:937–943. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.937-943.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosqueda G, Ramos-González M I, Ramos J L. Toluene metabolism by the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1 strain, and its role in solvent impermeabilization. Gene. 1999;232:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neyfakh A A. Natural functions of bacterial multidrug transporters. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:309–313. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulsen I T, Brown M H, Skurray R A. Proton-dependent multidrug efflux systems. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:575–608. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.575-608.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poole K, Krebes K, McNaily C, Neshat S. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for involvement of an efflux operon. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7363–7372. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7363-7372.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poole K, Treto K, Zhao Q X, Neshat S, Heinrichs D E, Biano N. Expression of the multidrug-resistance operon mexA-mexB-oprM in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: MexR encodes a regulator of operon expression. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2021–2028. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Postle K, Good R F. TonB protein and energy transduction between membranes. J Bioenerg Biomemb. 1993;25:591–601. doi: 10.1007/BF00770246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramos J L, Duque E, Huertas M J, Haïdour A. Isolation and expansion of the catabolic potential of a Pseudomonas putida strain able to grow in the presence of high concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3911–3916. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3911-3916.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramos J L, Duque E, Godoy P, Segura A. Efflux pumps involved in toluene tolerance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3323–3329. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3323-3329.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramos J L, Duque E, Rodríguez-Herva J-J, Godoy P, Haïdour A, Reyes F, Fernández-Barrero A. Mechanisms for solvent tolerance in bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3887–3890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramos-González, M. I., P. Godoy, M. Alaminos, E. Duque, A. Ben-Bassat, and J. L. Ramos. Physiological characterization of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E tolerance to p-hydroxybenzoate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Rodríguez-Herva J J, Ramos-González M I, Ramos J L. The Pseudomonas putida peptidoglycan-associated outer membrane lipoprotein is involved in maintenance of the integrity of the cell envelope. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1699–1706. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1699-1706.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rojas A, Duque E, Mosqueda G, Golden G, Hurtado A, Ramos J L, Segura A. Three efflux pumps are required to provide efficient tolerance to toluene in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3967–3973. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3967-3973.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saier M H, Jr, Paulsen I T, Sliwinski M K, Pao S, Skurray R A, Nikaido H. Evolutionary origins of multidrugs and drug-specific efflux pumps in bacteria. FASEB J. 1998;12:265–274. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Segura A, Duque E, Mosqueda G, Ramos J L, Junker F. Multiple responses of gram-negative bacteria to organic solvents. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:191–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sikkema J, de Bont J A, Poolman B. Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8022–8028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas L V, Wimpenny J W. Investigation of the effect of combined variations in temperature, pH, and NaCl concentration on nisin inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2006–2012. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2006-2012.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watanabe N A, Nagasu T, Katsu K, Kitoh K. E-0702, a new cephalosporin, is incorporated into Escherichia coli cells via the tonB-dependent iron transport system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:497–504. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiggerich H G, Klauke B, Koplin R, Priefer U B, Pühler A. Unusual structure of the tonB-exb DNA region of Xanthomonas compestris pv. campestris: tonB, exbB, and exbD1 are essential for ferric ion uptake, but exbD2 is not. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7103–7110. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7103-7110.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong K K Y, Brinkman F S L, Benz R S, Hancock R E W. Evaluation of a standard model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane protein OprM, an efflux component involved in intrinsic antibiotic resistance. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:367–374. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.367-374.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xian-Zhi L, Poole K. Mutational analysis of the OprM outer membrane component of the MexAB-OprM multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:12–27. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.12-27.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xian-Zhi L, Zhang L, Poole K. Role of the multidrug efflux systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in organic solvent tolerance. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2987–2991. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2987-2991.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yerushalmi H, Lebendiker M, Schuldiner S. EmrE, an Escherichia coli 12-kDa multidrug transporter, exchanges toxic cations and H+ and is soluble in organic solvents. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6856–6862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zgurskaya H I, Nikaido H. Multidrug resistance mechanisms: drug efflux across two membranes. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:219–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao Q, Li X Z, Mistry A, Srikumar R, Zhang L, Lomovskaya O, Poole K. Influence of the TonB energy-coupling protein on efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2225–2231. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao Q, Poole K. A second tonB gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is linked to the exbB and exbD genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;184:127–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]