Abstract

Aims

In hospital settings, decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatments are often made in a dialogue between a patient and their physician, with a focus on active treatment. Nurses can have a valuable contribution in this process, but it seems they are not always involved. Our aim was to explore how hospital nurses perceive their current role and preferred role in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatment in patients in the last phase of life.

Design

Cross‐sectional quantitative study conducted in the Netherlands in April and May 2019.

Methods

An online survey, using a questionnaire consisting of 12 statements on nurses' opinion about supporting patients in decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatments, and 13 statements on nurses' actual involvement in these decisions.

Results

In total 179 hospital nurses from multiple institutions who care for adult patients in the last phase of life responded. Nurses agreed that they should have a role in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments, indicating greatest agreement with ‘It is my task to speak up for my patient’ and ‘It is important that my role in supporting patients is clear’. However, nurses also said that in practice they were often not involved in shared decision‐making, with least involvement in ‘active participation in communication about treatment decisions’ and ‘supporting a patient with the decision’.

Conclusion

There is a discrepancy between nurses' preferred role in decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatment and their actual role. More effort is needed to increase nurses' involvement.

Impact

Nurses' contribution to decision‐making is increasingly considered to be valuable by the nurses themselves, physicians and patients, though involvement is still not common. Future research should focus on strategies, such as training programs, that empower nurses to take an active role in decision‐making.

Keywords: decision‐making, life‐prolonging treatment, nurses, nursing, palliative care nursing, survey

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients who are in the last phase of life due to advanced diseases or old‐age frailty often face difficult decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatment (Etkind et al., 2017; Pieterse, Stiggelbout, & Montori, 2019). Patients are considered to be in the last phase of life when they have a life‐threatening progressive illness, have a limited life expectancy (<1 year), or have a diagnosis of old‐age‐related frailty (i.e. aged over 70 and with multi‐morbidity). Decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatment concern for instance starting, refraining or withdrawing from chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, intravenous administration of antibiotics or artificial nutrition (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1997; Pieterse et al., 2019). Such treatments may have limited benefit besides prolonging life (Diouf, Menear, Robitaille, Painchaud Guerard, & Legare, 2016; Epstein et al., 2017). However, they may have harmful side effects such as nausea, fatigue or restrictions of movement, and therefore might harm the patient's quality of life (Epstein et al., 2017; Legare & Witteman, 2013; Shrestha et al., 2019). In these specific situations, difficult trade‐offs can be at stake: on the one hand offering a treatment that might result in prolongation of life but could also have harmful side effects that might reduce the quality of life, or on the other hand refraining from or withdrawing treatment and focusing on the quality of life.

2. BACKGROUND

Ideally, choices about potentially life‐prolonging treatments are made after careful consideration of the risks and benefits (Barry & Edgman‐Levitan, 2012; Engel, Brinkman‐Stoppelenburg, Nieboer, & van der Heide, 2018; Epstein et al., 2017; Kaasalainen et al., 2014). Shared decision‐making can be defined as an approach to treatment decisions that involves healthcare professionals' evidence and expertise as well as patients' values and preferences (Elwyn et al., 2017; Stiggelbout, Pieterse, & De Haes, 2015). This is considered important in helping patients, close relatives and healthcare professionals to explicitly determine the patient's preferences and values about the treatment options, including the option of refraining from potentially life‐prolonging treatment (Elwyn et al., 2017; Epstein et al., 2017). To incorporate patient preferences, four steps can be distinguished: (I) informing a patient that a decision is to be made and the patient's opinion is important; (II) explaining the options, including the benefits and disadvantages; (III) exploring the patient's preferences; and (IV) reaching a decision (Stiggelbout et al., 2015).

Decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatments are often made in a dialogue between the patient and their physician. There are indications that nurses are often not involved in shared decision‐making in general (Joseph‐Williams et al., 2017; Tariman et al., 2016), although their role is considered important (Dees et al., 2018). Patients are in close and frequent contact with nurses and therefore often share valuable information about their wishes and preferences with their nurses— information that they do not share with their physician (Engel et al., 2018; Epstein et al., 2017; Kaasalainen et al., 2014). Nurses can act as an intermediary between patients and physicians (Dees et al., 2018). In a qualitative study, Bos‐van den Hoek et al. found that nurses can have a complementary, facilitating or supporting role in shared decision‐making (Bos‐van den Hoek et al., 2021). To be more specific, nurses are able to provide a broader view of the patient's well‐being, to further explain information that has been given to a patient by the physician and to provide patients and their family with emotional support (Bos‐van den Hoek et al., 2021; McCullough, McKinlay, Barthow, Moss, & Wise, 2010; Salanterä, Eriksson, Junnola, Salminen, & Lauri, 2003). Involving nurses in the shared decision‐making process might lead to treatment decisions that are more in accordance with the patient's values and preferences, which might also result in a higher quality of life for both patients and their families (Bos‐van den Hoek et al., 2021; Wright et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009).

Nurses could make a valuable contribution in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments. However, previous research, mainly from Europe and North America, described that hospital nurses seem to be less involved than they would prefer (Bos‐van den Hoek et al., 2021; Lewis, Stacey, Squires, & Carroll, 2016; Stacey et al., 2011; Tariman & Szubski, 2015). Additionally, nurses have reported their wish to be more involved than they currently are in decision‐making towards the end of life (Albers et al., 2014; de Veer, Francke, & Poortvliet, 2008; Inghelbrecht, Bilsen, Mortier, & Deliens, 2009). In general, shared decision‐making is a topic of interest in countries around the world, that is in Europe, North America, South America, Australia and Asia (Alden, Merz, & Akashi, 2012; Diouf et al., 2016; Härter et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2013). At the same time, this interest is mainly limited to involvement of both patients and physicians in shared decision‐making. Unfortunately, despite this worldwide interest in shared decision‐making, little is known about the discrepancy between nurses' actual and preferred involvement, and their need for support to enable them to fulfil their preferred role in shared decision‐making.

2.1. THE STUDY

2.2. Aims

The following questions have been addressed in this study:

1. How do hospital nurses perceive their present role and preferred role in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments in patients in the last phase of life, due to advanced disease or old‐age frailty?

2. What support do hospital nurses need to fulfil their preferred role and to support patients who are in the last phase of life in decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments?

2.3. Design

In spring 2019, we conducted a cross‐sectional quantitative study among hospital nurses in the Netherlands, using an online survey.

2.4. Participants

Nurses working in hospitals were selected from a pre‐existing nationwide research sample, the Nursing Staff Panel (de Veer, 2021). This panel consists of a nationwide representative sample of nursing staff from multiple institutions in various healthcare sectors. Nurses in this panel are mainly recruited via Dutch employee insurance agencies. This recruitment method ensures a diverse composition of the Panel in terms of age, gender, region and employer.

All members of the Nursing Staff Panel previously agreed to complete questionnaires about issues in nursing on a regular basis. For this study, only members of the Nursing Staff Panel who worked as a registered nurse in a general or university hospital (n = 502) received an e‐mail with information about the aim and content of the survey and a unique link to the questionnaire. The internet link remained active for a period of 1 month, between 26 April and 26 May 2019. To improve the response rate, up to two e‐mail reminders were sent to non‐responders 1 week and 3 weeks after the first invitation. Respondents could enter a draw for 10 gift vouchers of €20 each.

2.5. Data collection

Data were collected using a self‐developed questionnaire. This questionnaire was partly based on findings from interviews in a previous study, in which nurses described their role in decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatment as checking, complementing and facilitating the decision‐making process (Bos‐van den Hoek et al., 2021). In addition to these items influenced by the interviews, we added a selection of items from the Role Competency Scale on Shared Decision‐Making––Nurses (SDM‐N; Tariman et al., 2018). The SDM‐N identifies the role competency of oncology nurses in decision‐making and consists of 20 statements on knowledge, attitude, communication skills and adaptability (Tariman et al., 2018). Since no Dutch version of the SDM‐N was available, a senior researcher translated all 20 statements from the original English version into Dutch. Backward translation was performed by an independent, bilingual Clinical Nurse Specialist who did not have access to the original version. There were few discrepancies in the wording of the translation compared with the original English version (such as ‘joint’ instead of ‘shared’ decision‐making), and these were resolved through discussion. Subsequently, in consultation with the research team we selected the items that covered our research focus, that is what nurses consider important (preferred role) and how they appraise their involvement (actual role) in decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatment. We initially selected 10 of the 20 items from the SDM‐N scale (see ‘Supporting Information’), and rephrased these through discussion to match our research focus and population (e.g. we changed the words ‘cancer treatment decision‐making process’ to ‘decision‐making about treatments in the last phase of life’). We subsequently added three statements that concerned the supportive role of nurses.

The questionnaire started with items on background characteristics, namely age, gender, work experience, work setting, highest level of nursing education and how often the nurse provides care for adult patients in the last phase of life (‘never’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’). Nurses who stated that they provided care for this patient group were invited to fill in the questionnaire. The questionnaire had two sections: one section about preferred and one about actual involvement. The section on preferred involvement consisted of 12 statements, starting with ‘I think that, considering decision‐making about life‐prolonging treatment, it is important that I…’, to be rated on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘totally disagree’), 2 (‘disagree’), 3 (‘neither disagree nor agree’), 4 (‘agree’) to 5 (‘totally agree’).

The second section concerned the actual involvement, which was assessed in 13 statements starting with ‘Considering decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatment, I…’, rated on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘never’), 2 (‘rarely’), 3 (‘occasionally’), 4 (‘frequently’) to 5 (‘always’). At the end of each section, nurses could add free‐text comments on their preferred role or their actual involvement.

In a final section, nurses were asked what they need for themselves and their team to support patients in the last phase of life in decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatment. These questions had multiple‐choice answer options, based on the interviews that were held previously (Bos‐van den Hoek et al., 2021). In addition, nurses could supplement these answers with free‐text comments.

2.6. Ethical considerations

For this questionnaire study no formal ethics approval was required, since the relevant Dutch act (Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act) only requires ethics approval from a Medical‐Ethical Review Board if the research concerns medical research in which participants are subjected to procedures or are required to follow rules of behaviour.

Study participation was voluntary. Participant consent was assumed on return of a completed questionnaire. The questionnaire data were stored and analysed anonymously, in accordance with the Dutch General Data Protection Regulation. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of good clinical practice.

2.7. Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed on the background characteristics of nurses' age, gender and work experience (in years).

To make the scores for the preferred and actual involvement easier to understand, they were computed in line with the rescaling procedures for the nine‐item Shared Decision‐Making Questionnaire (SDM‐9) and the shared decision‐making questionnaire from the perspective of the physician (SDM‐Q‐doc; Kriston et al., 2010; Rodenburg‐Vandenbussche et al., 2015). The scores are presented as percentages, with 100% representing the highest level of preferred or actual involvement and 0% the lowest level of preferred or actual involvement. To rescale the score, raw scores were multiplied by 20/12 (preferred involvement) or 20/13 (actual involvement; Kriston et al., 2010). Tests of normality showed that only the scores for the preferred role were normally distributed. Since scores on actual involvement were not normally distributed, nonparametric analysis (median scores with interquartile ranges) were used to present all scores. Descriptive analyses were used for the results. Open comments were only used to further illustrate the results; no further analysis was performed on the open comments. The questions on nurses' needs for support were also analysed using descriptive analysis.

The Wilcoxon Signed‐Rank test was used to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between the scores for the preferred role and the actual role.

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corporation). A p‐value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.8. Validity and reliability/rigour

The SDM‐N was previously found to be reliable and valid (Tariman et al., 2018). Since we translated and rephrased the items and also added self‐developed items, we pilot‐tested face validity with two hospital nurses using the ‘think aloud’ principle (Ramey et al., 2006). The items appeared to be easily understandable, and no adjustments were needed after pilot testing. Furthermore, we assessed internal consistency by calculating Cronbach's alpha, thereby evaluating the extent to which the different items of the questionnaire measure the same concept. In our study, overall Cronbach's alpha was .91. For the ‘preferred involvement’ and ‘actual involvement’ sections, Cronbach's alpha was .79 and .90, respectively.

3. RESULTS

A total of 233 members of the Nursing Staff Panel (response rate 46%) returned the online questionnaire (Figure 2). Of these respondents, 183 stated that they cared for adult patients in the last phase of life due to life‐threatening advanced diseases or old‐age frailty. Four questionnaires were excluded from the analysis since none of the statements were answered. Hence, 179 questionnaires were included in the analysis. Most respondents were female nurses, with a median age of 50 and median work experience of 25 years (Table 1).

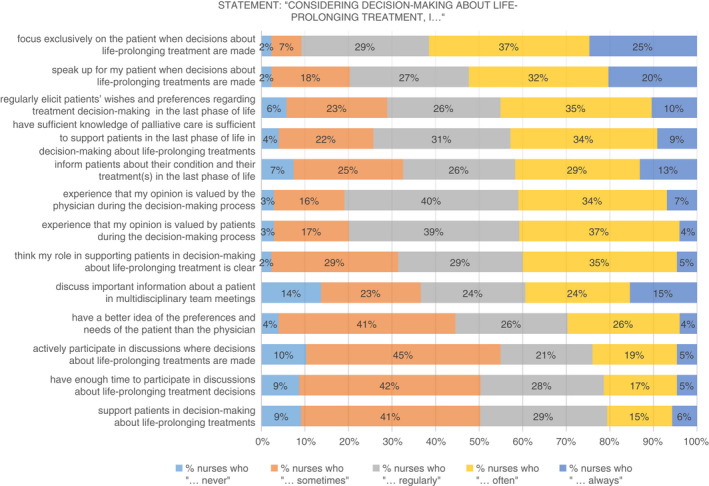

FIGURE 2.

Overview from answers in questioning nurses' actual role in shared decision‐making towards life‐prolonging treatments

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics, N = 179

| Gender | |

| Female – n (%) | 155 (86.6) |

| Age – median (min‐max) | 50 (22–64) |

| Work experience in years | |

| Median – min‐max | 25 (1–46) |

| Hospital type – n (%) | |

| General hospital | 142 (79.3) |

| Academic hospital | 37 (20.7) |

| Working with patient population – n (%) a | |

| Adults with incurable cancer | 169 (94.4) |

| Adults with other life‐limiting conditions | 160 (89.3) |

| Vulnerable elderly | 171 (95.5) |

| Working as – n (%) | |

| Nurse | 87 (48.6) |

| Clinical nurse specialist | 11 (6.1) |

| Specialized nurse | 70 (39.1) |

| Other | 11 (6.1) |

| Working in – n (%) a | |

| Inpatient clinic | 122 (52.4) |

| Outpatient clinic | 24 (10.3) |

| Day care | 24 (10.3) |

| Other b | 28 (12.0) |

| Specialism – n (%) a | |

| Oncology | 48 (26.8) |

| Pulmonology | 36 (20.1) |

| Cardiology | 41 (22.9) |

| Neurology | 28 (15.6) |

| Geriatrics | 18 (10.1) |

| Internal medicine | 40 (22.3) |

| Surgery | 47 (26.3) |

| Other c | 79 (44.1) |

Multiple answers possible.

Such as emergency or supporting specialism.

Such as emergency, nephrology, ICU, urology or multiple specialisms.

3.1. Nurses' preferred role in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments

The overall median score for the preferred role was 76.7% (interquartile range [IQR] 73.3%–83.3%; Figure 1). This means that nurses agreed that they prefer to have a role in supporting the patient's treatment decision, based on the categories from 1 (0%–20%, totally disagree) to 5 (80%–100%, totally agree).

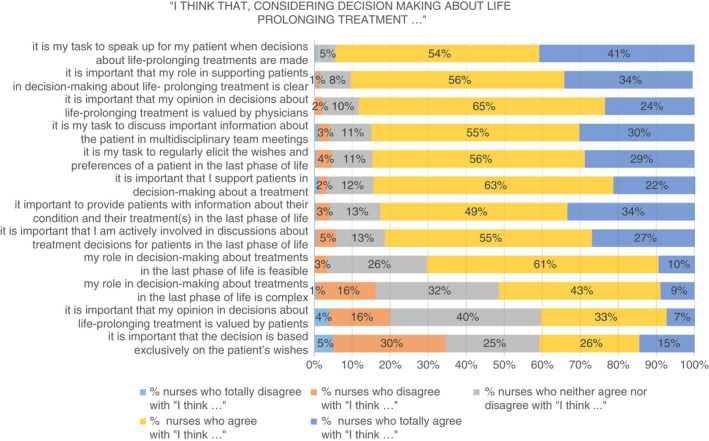

FIGURE 1.

Overview from answers in questioning nurses' preferred role in shared decision‐making towards life‐prolonging treatment

The greatest agreement was found with the following statements: ‘it is my task to speak up for my patient when decisions about life‐prolonging treatments are made’ (95% totally agree or agree) and ‘it is important that my role in supporting patients in decision‐making about life‐prolonging treatment is clear’ (90% totally agree or agree). Additionally, nurses say that they think it is important to support patients in decision‐making about a treatment (85% totally agree or agree). Nurses reported least agreement with ‘it is important that my opinion in decisions about life‐prolonging treatment is valued by patients’ (40% totally agree or agree) and ‘it is important that the decision is based exclusively on the patient's wishes' (41% totally agree or agree). Although nurses consider their preferred role as feasible (71% totally agree or agree with this), they also see this role as complex (52% totally agree or agree). In the open comments, some nurses added that it is important that the patient is well informed about the treatment options and outcomes before making the final choice based on their own values.

3.2. Nurses' actual role in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments

For their actual role, nurses reported an overall median score of 61.5% (IQR = 52.3%–70.8%; Figure 2), meaning that they are involved sometimes or regularly in decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments.

Considering the individual statements, the greatest agreement was found with the following statements: ‘focus exclusively on the patient when decisions about life‐prolonging treatment are made’ (62% always or often) and ‘I speak up for my patient when decisions about life‐prolonging treatments are made’ (52% always or often). Least agreement was reported by nurses with the following statements: ‘I support patients in decision‐making about life‐prolonging treatments’ (21% always or often) and ‘I have enough time to participate in discussions about life‐prolonging treatment decisions’ (22% always or often).

3.3. Differences between the actual role and preferred role

Nurses' scores on their actual role were significantly lower compared with their scores for the preferred role in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments (median scores 61.5% and 76.7%, respectively; p < .001). On an individual level, differences between nurses' preferred role and actual role varied from minus 19.2% to plus 50.1%, with a median difference of 16.1% (IQR = 8.8%–22.7%). Eleven nurses reported a negative difference between their preferred role and their actual role (−0.3% to −19.2%).

3.4. Need for support to fulfil the preferred role

To fulfil the preferred role in shared decision‐making, nurses reported a need for ‘time’ (mentioned by 51.4% of nurses) and ‘clear information transfer’ by direct colleagues (33.1%) and physicians (32.6%; Table 2). As for themselves, nurses mentioned the need for more knowledge about palliative care (44.7% of respondents), more clarity about their role in decision‐making (32.4%) and more skills in guiding patients at the end of life (31.8%; Table 3). In open comments, nurses added good communication, acknowledgement of their expertise and equivalence in roles as important factors to help them fulfil their preferred role in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments.

TABLE 2.

What nurses need most from ward management to support adult patients in decision‐making during the last phase of life, N = 175

| N (%) a | |

|---|---|

| Time to start a conversation with the patient about treatment decisions | 90 (51.4) |

| Clear information transfer about the patient from my direct colleagues | 58 (33.1) |

| Clear information transfer about the patient from the physician | 57 (32.6) |

| Training or education | 42 (24.0) |

| Shared vision from the department about palliative care | 41 (23.4) |

| Acknowledgement of my role in decision‐making by physicians | 37 (21.1) |

| Organized meetings to learn from each other's experiences | 36 (20.6) |

| Good coordination in EPD | 35 (20.0) |

| Clarity about my role in treatment decision‐making | 30 (17.1) |

| Space for autonomy in my work | 15 (8.6) |

| Acknowledgement of my role in decision‐making by other disciplines | 9 (5.1) |

| Nothing | 6 (3.4) |

| Other | 3 (1.7) |

| Guidance from my manager to guide patients in their last phase of life | 2 (1.1) |

Multiple answers possible.

TABLE 3.

What nurses themselves need most to support adult patients in decision‐making during the last phase of life, N = 170

| N (%) a | |

|---|---|

| More knowledge about palliative care | 76 (44.7) |

| More clarity about my role in decision‐making | 55 (32.4) |

| More skills in guiding patients at the end of life | 54 (31.8) |

| More skills in conversation techniques | 35 (20.6) |

| More knowledge about medical treatment(s) | 34 (20.0) |

| More skills in nursing leadership | 32 (18.8) |

| Nothing | 29 (17.1) |

| Other | 3 (1.8) |

Multiple answers possible.

4. DISCUSSION

The results of our study showed a significant difference between nurses' actual role and preferred role in decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments in patients who are in the last phase of life due to advanced diseases or old‐age frailty. Overall, nurses gave higher scores for their preferred role in decision‐making as compared with their actual role (15% difference). To be more involved in decisions about potentially life‐prolonging treatment, nurses report a need for the organization to arrange more time and education, and clearer information transfer; they also reported a personal need for knowledge and skills concerning end of life care, and more clarity about their role in the decision‐making process.

In our study, there is a huge gap between the importance that nurses attach to supporting a patient in decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments (85% of nurses agree or totally agree), and the actual support they report providing (21% say that they often or always provide support). Previous research found that nurses are able to fulfil a supportive role for patients, family and physicians by building trusting relationships, showing empathy and providing emotional support (Adams, Bailey, Anderson, & Docherty, 2011; Bos‐van den Hoek et al., 2021). Also, it was found that nurses might not always be aware of their contribution to shared decision‐making, given the difficulties that they experience in describing their role (Bos‐van den Hoek et al., 2021). Nevertheless, our findings confirm previous indications that nurses are less involved than they would prefer. If nurses are not as involved, this can result in patients feeling less supported (McAndrew, Leske, & Schroeter, 2018), but it might also cause distress among nurses (Mehlis et al., 2018). This confirms the importance of supporting nurses in fulfilling their role.

The fact that nurses reported a willingness to be involved in shared decision‐making is in agreement with other studies on end of life decision‐making (Albers et al., 2014; de Veer et al., 2008; Inghelbrecht et al., 2009). Previously, nurses said they should have an important role in decision‐making given their frequent contact with patients (de Veer et al., 2008; Inghelbrecht et al., 2009). In our study, most nurses agreed that this preferred role is feasible (71%), though complex (52%). To increase their involvement, both individual and organizational prerequisites must be satisfied. One could consider the concept of decision coaches, whose role is to assess decisional conflicts, address decisional needs and provide understanding and support (Stacey et al., 2008). Nurses are well positioned to adopt the role of decision coach, especially after being trained in knowledge and skills (Stacey et al., 2011; Stacey et al., 2008). As an organizational prerequisite, support from managers is important in enabling nurses to become more involved in the decision‐making (Peter, Lunardi, & Macfarlane, 2004). This support could, for example, involve promoting an interdisciplinary approach in which professionals initiate conversations in good time about the patient's wishes and preferences about potentially life‐prolonging treatment (Dees et al., 2018). Advance care planning, including advance directives, can be considered as part of a timely, proactive approach. Nurses can proactively discuss patients' values and preferences for future potentially life‐prolonging treatment, including the use of advance directives to express these preferences (Dowling, Kennedy, & Foran, 2020).

Surprisingly, some nurses reported a higher level of involvement in their actual role as compared with their preferred role. This would indicate that not all nurses prefer to become more involved in shared decision‐making than they are at present. It has been reported previously that certain characteristics of professionals may influence their role in decision‐making processes (de Veer et al., 2008; Inghelbrecht et al., 2009). A greater need for involvement in decision‐making was found for nurses who were female, had a higher level of nursing education and worked in a hospital setting (Albers et al., 2014; Inghelbrecht et al., 2009). Although we did not aim to gain insight into factors that might influence nurses' desire to be involved in decision‐making, we did explore whether gender, level of education or position were associated with the reported difference between actual and preferred involvement. These tests did not show any significant effects.

As prerequisites for attaining their preferred role, nurses reported sufficient training, sufficient time and a clear role and handover. Most nurses agreed that there was a need for training in knowledge and skills concerning palliative care. A lack of knowledge hampers nurses' involvement in shared decision‐making (Lenzen, Daniëls, van Bokhoven, van der Weijden, & Beurskens, 2018; Stacey et al., 2008). Previous studies described the benefits and effectiveness of training in decision‐making for knowledge and skills (Brom et al., 2017; Légaré et al., 2011; Lenzen et al., 2018; Stacey et al., 2008). Preferably, such training should be inter‐professional, given the inter‐professional nature of shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments (Légaré et al., 2011). Also, inter‐professional training can be helpful in practising communication and clinical leadership skills and with a preferred role in a team (Légaré et al., 2011). The reported lack of time seems to thwart the need to be involved in decision‐making. A lack of time for discussing patients' needs and for the handover of information between healthcare professionals was previously found to be a bottleneck for shared decision‐making (Dobler et al., 2019; Joseph‐Williams et al., 2017). In our study, only 22% of the nurses reported that they have enough time to participate in discussions about life‐prolonging treatment decisions. Nowadays, nurses need to perform their daily routines under tremendous time pressure. Therefore, training should focus on integrating shared decision‐making in daily routines and supporting tools for discussion (8).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

The data in our study reflect nurses' self‐reported perceptions of preferred and actual involvement in decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatment in a nationwide sample. The use of a nationwide sample of nursing staff improved generalizability since this sample is representative, at least for the Netherlands. We also think that our results are relevant for researchers and practitioners in other countries. There is interest around the world in integrating shared decision‐making in daily practice, including with a substantial role for nurses. Our results create awareness of the gap between nurses' actual role and their preferred role, and underline the importance of taking nurses' preferences into account when integrating shared decision‐making.

The response rate of 46% was fair, and the sample was relatively old (median age of 50). Therefore, we cannot eliminate the risk of selection bias. It is suggested that people are more likely to respond when having strong feelings about a topic, either positive or negative (Saleh & Bista, 2017). In our study, it is possible that nurses who are not involved in end of life care did not respond, thereby giving an underestimate of the response rate. As a second limitation, the self‐reported perceptions of nurses might not reflect the actual situation. Additional observations might give a better presentation of actual involvement. Since no extreme scores were found in our data, we do not expect these limitations to have influenced our outcomes positively or negatively.

4.2. Implications for nursing

The findings of our study demonstrate the importance of improving nurses' involvement in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments. Not only do nurses agree in their need for a clear role in decision‐making, they also agree that this role should be attainable. Nurses need to be supported in positioning themselves in the process of shared decision‐making.

For future research it is recommended to focus on strategies to support nurses in their role in decision‐making. Moreover, future research should further examine nurses' preferences for their involvement in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments.

5. CONCLUSION

There is a discrepancy between nurses' preferred role and their perceived actual role in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments in patients in the last phase of life. Nurses prefer to be more involved than they are in practice. More effort is needed to support hospital nurses in achieving their preferred involvement in shared decision‐making about potentially life‐prolonging treatments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SA, MT, AV, RP, AF, IJ: Made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; SA, MT, AV, RP, AF, IJ: Involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; SA, MT, AV, RP, AF, IJ: Given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; SA, MT, AV, RP, AF, IJ: Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15223.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the nurses who participated in our study.

Arends, S. A. , Thodé, M. , De Veer, A. J. , Pasman, H. R. , Francke, A. L. & Jongerden, I. P. (2022). Nurses' perspective on their involvement in decision‐making about life‐prolonging treatments: A quantitative survey study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 2884–2893. 10.1111/jan.15223

Funding informationThis work was financially supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (project number 844001513).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Authors do not wish to share the data.

REFERENCES

- Adams, J. A. , Bailey, D. E., Jr. , Anderson, R. A. , & Docherty, S. L. (2011). Nursing roles and strategies in end‐of‐life decision making in acute care: A systematic review of the literature. Nursing Research & Practice, 2011, 527834. 10.1155/2011/527834, 1, 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers, G. , Francke, A. L. , de Veer, A. J. , Bilsen, J. , & Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. D. (2014). Attitudes of nursing staff towards involvement in medical end‐of‐life decisions: A national survey study. Patient Education and Counseling, 94(1), 4–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alden, D. L. , Merz, M. Y. , & Akashi, J. (2012). Young adult preferences for physician decision‐making style in Japan and the United States. Asia‐Pacific Journal of Public Health, 24(1), 173–184. 10.1177/1010539510365098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M. J. , & Edgman‐Levitan, S. (2012). Shared decision making‐‐pinnacle of patient‐centered care. The New England Journal of Medicine, 366(9), 780–781. 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos‐van den Hoek, D. W. , Thodé, M. , Jongerden, I. P. , Van Laarhoven, H. W. M. , Smets, E. M. A. , Tange, D. , & Pasman, H. R. (2021). The role of hospital nurses in shared decision‐making about life‐prolonging treatment: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(1), 296–307. 10.1111/jan.14549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brom, L. , De Snoo‐Trimp, J. C. , Onwuteaka‐Philipsen, B. D. , Widdershoven, G. A. , Stiggelbout, A. M. , & Pasman, H. R. (2017). Challenges in shared decision making in advanced cancer care: A qualitative longitudinal observational and interview study. Health Expectations, 20(1), 69–84. 10.1111/hex.12434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles, C. , Gafni, A. , & Whelan, T. (1997). Shared decision‐making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science & Medicine, 44(5), 681–692. 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Veer, A. (15 April 2021). Nursing staff panel . Retrieved from https://www.nivel.nl/en/panel‐verpleging‐verzorging/nursing‐staff‐panel

- de Veer, A. J. , Francke, A. L. , & Poortvliet, E. P. (2008). Nurses' involvement in end‐of‐life decisions. Cancer Nursing, 31(3), 222–228. 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305724.83271.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dees, M. K. , Geijteman, E. C. T. , Dekkers, W. J. M. , Huisman, B. A. A. , Perez, R. , van Zuylen, L. , van der Heide, A. , & van Leeuwen, E. (2018). Perspectives of patients, close relatives, nurses, and physicians on end‐of‐life medication management. Palliative & Supportive Care, 16(5), 580–589. 10.1017/s1478951517000761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diouf, N. T. , Menear, M. , Robitaille, H. , Painchaud Guerard, G. , & Legare, F. (2016). Training health professionals in shared decision making: Update of an international environmental scan. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(11), 1753–1758. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobler, C. C. , Sanchez, M. , Gionfriddo, M. R. , Alvarez‐Villalobos, N. A. , Singh Ospina, N. , Spencer‐Bonilla, G. , Thorsteinsdottir, B. , Benkhadra, R. , Erwin, P. J. , West, C. P. , Brito, J. P. , Murad, M. H. , & Montori, V. M. (2019). Impact of decision aids used during clinical encounters on clinician outcomes and consultation length: A systematic review. BMJ Quality and Safety, 28(6), 499–510. 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, T. , Kennedy, S. , & Foran, S. (2020). Implementing advance directives – An international literature review of important considerations for nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(6), 1177–1190. 10.1111/jonm.13097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn, G. , Durand, M. A. , Song, J. , Aarts, J. , Barr, P. J. , Berger, Z. , Cochran, N. , Frosch, D. , Galasiński, D. , Gulbrandsen, P. , Han, P. K. J. , Härter, M. , Kinnersley, P. , Lloyd, A. , Mishra, M , Perestelo‐Perez, L. , Scholl, I. , Tomori, K. , Trevena, L. , … Van der Weijden, T. (2017). A three‐talk model for shared decision making: Multistage consultation process. BMJ, 359, j4891. 10.1136/bmj.j4891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel, M. , Brinkman‐Stoppelenburg, A. , Nieboer, D. , & van der Heide, A. (2018). Satisfaction with care of hospitalised patients with advanced cancer in The Netherlands. European Journal of Cancer Care, 27(5), e12874. 10.1111/ecc.12874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, R. M. , Duberstein, P. R. , Fenton, J. J. , Fiscella, K. , Hoerger, M. , Tancredi, D. J. , Xing, G. , Gramling, R. , Mohile, S. , Franks, P. , Kaesberg, P. , Plumb, S. , Cipri, C. S. , Street Jr, R. L. , Shields, C. G. , Back, A. L. , Butow, P. , Walczak, A. , Tattersall, M. , … Kravitz, R. L. (2017). Effect of a patient‐centered communication intervention on oncologist‐patient communication, quality of life, and health care utilization in advanced cancer: The VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncology, 3(1), 92–100. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkind, S. N. , Bone, A. E. , Gomes, B. , Lovell, N. , Evans, C. J. , Higginson, I. J. , & Murtagh, F. E. M. (2017). How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Medicine, 15(1), 102. 10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härter, M. , Moumjid, N. , Cornuz, J. , Elwyn, G. , & van der Weijden, T. (2017). Shared decision making in 2017: International accomplishments in policy, research and implementation. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen, 123–124, 1–5. 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inghelbrecht, E. , Bilsen, J. , Mortier, F. , & Deliens, L. (2009). Nurses' attitudes towards end‐of‐life decisions in medical practice: A nationwide study in Flanders, Belgium. Palliative Medicine, 23(7), 649–658. 10.1177/0269216309106810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph‐Williams, N. , Lloyd, A. , Edwards, A. , Stobbart, L. , Tomson, D. , Macphail, S. , Dodd, C. , Brain, K. , Elwyn, G. , & Thomson, R. (2017). Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: Lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ, 357, j1744. 10.1136/bmj.j1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasalainen, S. , Brazil, K. , Williams, A. , Wilson, D. , Willison, K. , Marshall, D. , Taniguchi, A. , & Phillips, C. (2014). Nurses' experiences providing palliative care to individuals living in rural communities: Aspects of the physical residential setting. Rural and Remote Health, 14(2), 2728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriston, L. , Scholl, I. , Hölzel, L. , Simon, D. , Loh, A. , & Härter, M. (2010). The 9‐item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM‐Q‐9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Education and Counseling, 80(1), 94–99. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré, F. , Stacey, D. , Pouliot, S. , Gauvin, F. P. , Desroches, S. , Kryworuchko, J. , Dunn, S. , Elwyn, G. , Frosch, D. , Gagnon, M. P. , Harrison, M. B. , Pluye, P. , & Graham, I. D. (2011). Interprofessionalism and shared decision‐making in primary care: A stepwise approach towards a new model. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 25(1), 18–25. 10.3109/13561820.2010.490502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare, F. , & Witteman, H. O. (2013). Shared decision making: Examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Affairs, 32(2), 276–284. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen, S. A. , Daniëls, R. , van Bokhoven, M. A. , van der Weijden, T. , & Beurskens, A. (2018). Development of a conversation approach for practice nurses aimed at making shared decisions on goals and action plans with primary care patients. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 891. 10.1186/s12913-018-3734-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K. B. , Stacey, D. , Squires, J. E. , & Carroll, S. (2016). Shared decision‐making models acknowledging an interprofessional approach: A theory analysis to inform nursing practice. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 30(1), 26–43. 10.1891/1541-6577.30.1.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, N. S. , Leske, J. , & Schroeter, K. (2018). Moral distress in critical care nursing: The state of the science. Nursing Ethics, 25(5), 552–570. 10.1177/0969733016664975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, L. , McKinlay, E. , Barthow, C. , Moss, C. , & Wise, D. (2010). A model of treatment decision making when patients have advanced cancer: How do cancer treatment doctors and nurses contribute to the process? European Journal of Cancer Care (Engl), 19(4), 482–491. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01074.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlis, K. , Bierwirth, E. , Laryionava, K. , Mumm, F. H. A. , Hiddemann, W. , Heußner, P. , & Winkler, E. C. (2018). High prevalence of moral distress reported by oncologists and oncology nurses in end‐of‐life decision making. Psychooncology, 27(12), 2733–2739. 10.1002/pon.4868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C. J. , Lee, P. Y. , Lee, Y. K. , Chew, B. H. , Engkasan, J. P. , Irmi, Z. I. , Hanafi, N. S. , & Tong, S. F. (2013). An overview of patient involvement in healthcare decision‐making: A situational analysis of the Malaysian context. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 408. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter, E. , Lunardi, V. L. , & Macfarlane, A. (2004). Nursing resistance as ethical action: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 46(4), 403–416. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, A. H. , Stiggelbout, A. M. , & Montori, V. M. (2019). Shared decision making and the importance of time. JAMA, 322(1), 25–26. 10.1001/jama.2019.3785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey, J. , Boren, T. , Cuddihy, E. , Dumas, J. , Guan, Z. , Haak, M. J. v. d. , & Jong, M. D. T. D. (2006). Does think aloud work? How do we know? Paper presented at the CHI '06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, Québec, Canada. 10.1145/1125451.1125464 [DOI]

- Rodenburg‐Vandenbussche, S. , Pieterse, A. H. , Kroonenberg, P. M. , Scholl, I. , van der Weijden, T. , Luyten, G. P. M. , Kruitwagen, R. F. P. M. , den Ouden, H. , Carlier, I. V. E. , van Vliet, I. M. , Zitman, F. G. , & Stiggelbout, A. M. (2015). Dutch translation and psychometric testing of the 9‐item shared decision making questionnaire (SDM‐Q‐9) and shared decision making questionnaire‐physician version (SDM‐Q‐Doc) in primary and secondary care. PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0132158. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanterä, S. , Eriksson, E. , Junnola, T. , Salminen, E. K. , & Lauri, S. (2003). Clinical judgement and information seeking by nurses and physicians working with cancer patients. Psychooncology, 12(3), 280–290. 10.1002/pon.643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A. , & Bista, K. (2017). Examining factors impacting online survey response rates in educational research: Perceptions of graduate students. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 13(29), 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, A. , Martin, C. , Burton, M. , Walters, S. , Collins, K. , & Wyld, L. (2019). Quality of life versus length of life considerations in cancer patients: A systematic literature review. Psychooncology, 28(7), 1367–1380. 10.1002/pon.5054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D. , Bennett, C. L. , Barry, M. J. , Col, N. F. , Eden, K. B. , Holmes‐Rovner, M. , Llewellyn‐Thomas, H. , Lyddiatt, A. , Légaré, F. , & Thomson, R. (2011). Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD001431. 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D. , Murray, M. A. , Légaré, F. , Sandy, D. , Menard, P. , & O'Connor, A. (2008). Decision coaching to support shared decision making: A framework, evidence, and implications for nursing practice, education, and policy. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 5(1), 25–35. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2007.00108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiggelbout, A. M. , Pieterse, A. H. , & De Haes, J. C. (2015). Shared decision making: Concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(10), 1172–1179. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariman, J. D. , Katz, P. , Bishop‐Royse, J. , Hartle, L. , Szubski, K. L. , Enecio, T. , Garcia, I. , Spawn, N. , & Masterton, K. J. (2018). Role competency scale on shared decision‐making nurses: Development and psychometric properties. SAGE Open Medicine, 6, 2050312118807614. 10.1177/2050312118807614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariman, J. D. , Mehmeti, E. , Spawn, N. , McCarter, S. P. , Bishop‐Royse, J. , Garcia, I. , Hartle, L. , & Szubski, K. (2016). Oncology nursing and shared decision making for cancer treatment. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20(5), 560–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariman, J. D. , & Szubski, K. L. (2015). The evolving role of the nurse during the cancer treatment decision‐making process: A literature review. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(5), 548–556. 10.1188/15.CJON.548-556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A. A. , Zhang, B. , Ray, A. , Mack, J. W. , Trice, E. , Balboni, T. , Mitchell, S. L. , Jackson, V. A. , Block, S. D. , Maciejewski, P. K. , & Prigerson, H. G. (2008). Associations between end‐of‐life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA, 300(14), 1665–1673. 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. , Wright, A. A. , Huskamp, H. A. , Nilsson, M. E. , Maciejewski, M. L. , Earle, C. C. , Block, S. D. , Maciejewski, P. K. , & Prigerson, H. G. (2009). Health care costs in the last week of life: Associations with end‐of‐life conversations. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(5), 480–488. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Data Availability Statement

Authors do not wish to share the data.