Abstract

Background

Chronic low back pain (LBP), neck pain (NP), and sleep quality (SQ) are genetically influenced. All three conditions frequently co‐occur and shared genetic aetiology on a pairwise base has been reported. However, to our knowledge, no study has yet investigated if these three conditions are influenced by the same genetic and environmental factors and the extent and pattern of genetic overlap between them, hence the current research.

Methods

The sample included 2134 participants. Lifetime prevalence of NP and LBP were assessed through a dichotomous self‐reported question derived from the Spanish National Health Survey. SQ was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Questionnaire. A common pathway model with sleep quality and back pain as latent factors was fitted.

Results

Our results highlight that a latent back pain factor, including both NP and LBP, is explained by both genetic (41%) and environmental (59%) factors. There are also significant unique environmental factors for NP (33%) and LBP (37%) respectively. Yet, specific genetic factors were scant (9%) for NP and negligible for LBP (0%). Genetic and environmental factors affecting SQ only contribute with 3% and 5% of the variance, respectively, to the common latent back pain variable.

Conclusions

NP and LBP share most of their genetic variance, while environmental effects show greater specificity for each of the back pain locations. Associations with SQ were of a limited magnitude.

Significance

Our results confirm a significant association between both chronic NP and LBP and sleep quality. Such relationship comprises both genetic and environmental factors, with a greater relative weight of the latter. A large part of the individual variance for chronic LBP and chronic NP can be accounted for by a latent common factor of ‘back pain’. Genetic influences for LBP and NP were mainly shared. However, environmental influences were common for both problems and specific for each of them in similar magnitudes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is common, with a 9% and 5% life‐time prevalence estimate for chronic low back pain (LBP) and chronic neck pain (NP) (Reid et al., 2011) respectively. LBP and NP frequently co‐occur (Nyman et al., 2011) in both older and young individuals (Hartvigsen et al., 2004; Nyman et al., 2009), and this co‐occurrence is associated with poorer health (Hartvigsen et al., 2004). LBP and NP also have a significant impact in terms of economic costs and healthcare utilization (Henschke et al., 2015), and rank first and sixth among the global leading causes in terms of years‐lived with disability respectively (Vos et al., 2017).

A co‐morbidity associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain is the presence of sleep problems (McBeth et al., 2015), with evidence compatible with a bidirectional relationship (Andreucci et al., 2020; Finan et al., 2013; McBeth et al., 2015; Pinheiro et al., 2018). In this model, a worsening in sleep or chronic musculoskeletal pain would occur with a parallel worsening of the other condition, although it has been proposed that sleep difficulties may be more likely to precede pain in contrast to pain preceding sleep difficulties (Finan et al., 2013; McBeth et al., 2015). It is acknowledged that sleep (Tafti, 2009), NP (Hogg‐Johnson et al., 2008; Nielsen et al., 2012) and LBP (Nielsen et al., 2012) are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. A recent meta‐analysis found that genetic factors account for 31% of the variance on sleep quality (Madrid‐Valero et al., 2020). The heritability of LBP has been estimated as 26%–68% (Nielsen et al., 2012) in adult populations from Denmark (Hartvigsen et al., 2009; Hestbaek et al., 2004), Spain (Pinheiro et al., 2018), Sweden (Nyman et al., 2011), Norway (Reichborn‐Kjennerud et al., 2002) and the UK (Livshits et al., 2011; MacGregor et al., 2004). Figures range from 24 to 58% for NP, as observed in adult populations from the UK, Sweden and Denmark (Hogg‐Johnson et al., 2008; Nielsen et al., 2012), although no heritability in Danish elderly subjects was reported in one study (Hartvigsen et al., 2005). In addition, a study showed a stronger influence of genetic factors for the co‐occurrence of LBP and NP (60%) compared to LBP (30%) or NP (24%) alone (Nyman et al., 2011). The association between sleep and pain is also affected by genetic and environmental factors, with differences observed between studies (Gasperi et al., 2017; Pinheiro et al., 2018).

Despite the knowledge that sleep difficulties, chronic LBP and chronic NP are genetically influenced and co‐occur, no study has reported if these three conditions are influenced by the same genetic and environmental factors and the extent and pattern of genetic overlap between them. However, research about the aetiology of chronic pain is instrumental to understanding its origin and development and could also help us to tackle the progression to more severe forms of the condition, such as disabling back pain. Therefore, our aim was to evaluate the aetiology of the association between sleep quality, chronic LBP and chronic NP in a representative sample of adult Spanish twins.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

The sample was composed of 2134 participants (1176 twin pairs) of the Murcia Twin Registry (MTR), which is a population‐based registry of adult twins born between 1940 and 1976 in the region of Murcia, South East Spain. Twin pairs were distributed as follows: 157 MZMale (28 incomplete); 198 DZMale (35 incomplete); 213 MZFemale (17 incomplete); 217 DZFemale (29 incomplete) and 391 DZOpposite‐sex (109 incomplete). The MTR main objectives, composition, data collection waves and research procedures have been described extensively elsewhere (Ordoñana et al., 2013, 2019), and the representativeness of the sample has been previously proven (Ordoñana et al., 2018). All registry and data collection procedures involved in this study were approved by the Murcia University Ethics Committee, and informed consent was obtained from all twins. Data for this study include monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins interviewed in 2009/2010, who provided information on the main variables.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Neck and low back pain

Lifetime prevalence of both NP and LBP were assessed through a dichotomous self‐reported question derived from the Spanish National Health Survey (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica, 2012). Participants were required to answer the following questions: ‘Have you ever suffered from chronic neck/low back pain’? Participants were classified, according to their answers to these questions, into two categories, yes = 1; or no = 2, for both NP and LBP. Chronic NP/LBP was explained to participants as pain in the neck or in the low back that lasted for at least 6 months (including seasonal or recurrent episodes).

2.2.2. Sleep quality assessment

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al., 1989) was used to assess sleep quality. The PSQI is a widely used questionnaire for the assessment of sleep quality referencing the previous month. It provides a global score, which ranges from 0 to 21 (a higher score represents poorer sleep quality) and allows to distinguish between subjects with poor sleep quality (>5 points) and subjects with adequate sleep quality (≤5 points). This global score is built based on the score of 7 sub‐scales (i.e., (1) subjective sleep quality; (2) sleep latency; (3) sleep duration; (4) habitual sleep efficiency; (5) sleep disturbances; (6) use of sleeping medication and (7) day time dysfunction) that are used to calculate the global score.

The questionnaire has been validated in its Spanish version (Royuela‐Rico & Macías‐Fernández, 1997) and has also adequate psychometric properties, high correlations with objective measures. Previous studies have also validated the single‐factor scoring structure (Boudebesse et al., 2014; Carpenter & Andrykowski, 1998; Raniti et al., 2018). In this sample, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.73.

2.2.3. Psychological distress

Psychological distress was assessed by self‐report, using the ‘depression or anxiety’ domain of the Spanish version of the EQ5D (EuroQol five‐dimensions questionnaire) (Rabin & De Charro, 2001; Ramos‐Goñi et al., 2018). Participants had to choose among three different options selecting the one that best describes themselves at the present day. (‘I am not anxious or depressed’; ‘I am moderately anxious or depressed’; and ‘I am extremely anxious or depressed’. Since the third category was infrequent (4.3%), it was collapsed with the second category. This variable was added to the model in order to control for the effect of this phenotype on both chronic pain and sleep quality.

2.2.4. Zygosity assessment

The zygosity of the twins was established by means of DNA test (338 pairs) or by questionnaire, when this was not possible. A 12‐item questionnaire focused in the degree on similarity and mistaken identity between twins was used for zygosity ascertainment. This questionnaire‐based zygosity corresponds well with DNA testing, with an agreement in nearly 96% of participants (Ordoñana et al., 2013).

2.3. Statistical analyses

In this study, we applied a classical twin design. The basic logic of a twin design can be summarized as follows: the variance of one trait can be decomposed into variance attributable to genetic and environmental factors. For this purpose, we make use of the difference between MZ twins (who are genetically identical) and DZ twins (who share on average 50% of their segregating DNA) (Knopik et al., 2017).

In a classical twin design, the variance can be described as the sum of different parameters: additive genetic effects (A; the sum of allelic effects across all loci), non‐additive genetic effects (D; the effects of genetic dominance and, possibly, epistasis); shared‐environmental effects (C; influences that make twin pairs raised in the same family similar to each other); and non‐shared environmental effects (E, effects that make family members less alike such as accidents or individual experiences. This parameter also includes measurement error) (Rijsdijk & Sham, 2002; Verweij et al., 2012).

As it is not possible to estimate C and D simultaneously in the same model using only data from twins reared together, we chose between an ACE or ADE model based on the pattern of correlations between MZ and DZ twins. Typically, an ACE model is selected when the DZ twin correlation is greater than half of the MZ twin correlation, and an ADE model is selected when the DZ twin correlation is less than half of the MZ correlation (Neale & Cardon, 1992; Verweij et al., 2012).

Nonetheless, both ACE/ADE models were fitted initially for all outcome variables in order to check the assumption based on correlation patterns. Nested models (i.e., AE, CE and E) were also fitted to check if one (or two) components of the variance could be dropped, following the criterion of parsimony, without a significant deterioration of the model fit. The fit of the different models and sub‐models was checked using the likelihood‐ratio chi‐square test and the Akaike's information criterion (AIC) (Akaike, 1987). Assumptions of twin models (i.e., no differences in variance or mean levels between different groups) were checked in the saturated models.

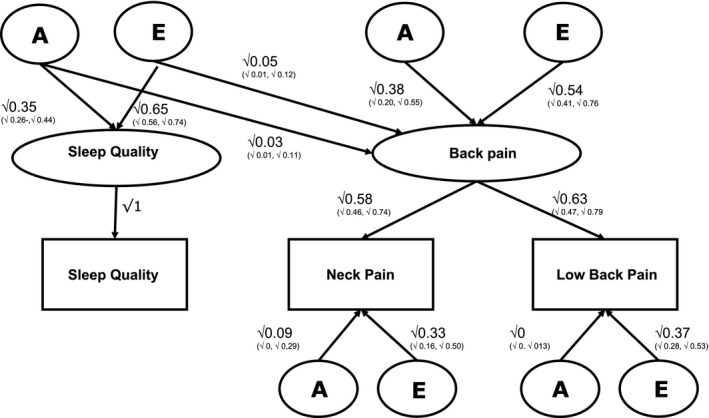

A common pathway model (Rijsdijk, 2005) with two latent factors was fitted (Figure 1) in order to explore the genetic and environmental relationships between sleep quality and musculoskeletal pain. This model had one latent factor, which included both back pain phenotypes (i.e., NP and LBP) and one latent factor for sleep quality alone. This allowed us to obtain estimates for: (1) the genetic and environmental influences for each of the latent factors (i.e., a common structure for back pain and sleep quality itself); (2) the specific genetic and environmental factors on LBP and NP separately and (3) the genetic and environmental paths for the covariance between sleep quality and the latent factor for back pain.

FIGURE 1.

Common pathway model for sleep quality, neck pain and low back pain

Additionally, a multivariate Cholesky model was also fitted (transformed into a correlated factor solution) (Figure S1) in order to estimate the aetiological correlations (i.e., rA, rC, rD, rE), which inform us about the overlap between the traits' sources of variance, and the bivariate heritability, which is the proportion of the phenotypic covariance explained by genetic factors.

Binary variables were analysed under a liability threshold assumption. This assumes that the categories reflect an imprecise measurement of an underlying distribution of liability. The liability is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean value of 0 and a variance of 1. Thresholds divide the underlying liability scale in regions or categories that are associated with specific observed phenotypes. The trait is expressed when the liability exceeds a certain threshold value. Using information from the MZ and DZ ratio in twin similarity—called polychoric correlations—this liability can be further modelled to be influenced by genetic and environmental factors (Rijsdijk & Sham, 2002). We included age and sex as covariates in all models. Both same‐sex and opposite‐sex dizygotic twins were modelled as DZ pairs, since no sex difference in the variance distribution of NP and LBP was observed in previous testing in this sample (Table S1), while results for sleep quality were reported elsewhere (Madrid‐Valero et al., 2018). Sleep quality was +1 log transformed to reduce the skewness (from 0.94 transformation to −0.38). All twin analyses were performed using the package OpenMx in R. (Neale et al., 2016).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive statistics

In Table 1 descriptive statistics are displayed. Females had a higher score in poor sleep quality compared to males (t[1920] = 7.74; p < 0.001; female = 5.79; male = 4.42; Cohen's d = 0.35) and they were more likely to report NP (39.5 vs 15.1; p < 0.001) and LBP (40.9 vs 21.9, p < 0.001). No differences were found between MZ and DZ twins for the key variables of this study (i.e., sleep quality, NP and LBP) (Table 1). Regarding NP, 116 pairs were concordant, whereas 313 pairs were discordant for this condition. As for LBP 127 pairs were concordant and 368 discordant for chronic LBP.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Male | Female | MZ | DZSS | DZOS | Total sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N (%) | 969 (45.4) | 1165 (54.6) | 695 (32.6) | 766 (35.9) | 673 (31.5) | 2134 (100) |

| Age mean (SD) | 53.77 (7.18) | 53.67 (7.46) | 52.20 (6.96) | 52.92 (7.44) | 56.18 (6,97) | 53.71 (7.34) |

| Mean PSQI (SD) | 4.42 (3.59) | 5.79 (4.16) | 5.23 (3.94) | 5.22 (4.00) | 5.09 (3.99) | 5.19 (3.97) |

| Subjects with low back pain N (%) | 212 (21.9) | 477 (40.9) | 236 (34.0) | 265 (34.6) | 158 (23.2) | 689 (32.3) |

| Subjects with neck pain N (%) | 146 (15.1) | 460 (39.5) | 217 (31.2) | 233 (30.4) | 188 (28.0) | 606 (28.4) |

3.2. Results from the univariate twin models

Table 2 presents all the results from the univariate models. All the intrapair correlations were higher for MZ (0.27 to 0.35) than DZ (0.14 to 0.19) twins. These patterns of correlations indicate that genetic factors are playing a substantial role in these three phenotypes. As the correlation patterns also suggest, ACE models fitted better than ADE models for pain variables, while the contrary was true for sleep quality.

TABLE 2.

Correlations, variance distribution and fitting statistics from univariate models

| Model | Model for comparison | A (95% CI) | C/D (95% CI) | E (95% CI) | Df | ‐2LL | AIC | DiffLL | Diffdf | P | rMZ | rDZ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low back pain | 0.27 (0.08, 0.43) | 0.15 (0.01, 0.28) | |||||||||||

| ADE | 0.27 (0, 0.41) | 0 (0,0) | 0.73 (0.57,0.88) | 2127 | 2580.40 | −1673.70 | |||||||

| ACE | 0.22 (0, 0.41) | 0.04 (0, 0.28) | 0.74 (0.59, 0.91) | 2127 | 2580.34 | −1673.66 | |||||||

| AE | ACE | 0.27 (0.11, 0.41) | / | 0.73 (0.59, 0.88) | 2128 | 2580.40 | −1675.60 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.80 | |||

| CE | ACE | / | 0.19 (0.08, 0.29) | 0.81 (0.71, 0.92) | 2128 | 2581.23 | −1674.77 | 0.89 | 1 | 0.35 | |||

| E | AE | / | / | 1 (1, 1) | 2129 | 2592.49 | −1665.51 | 12.08 | 1 | <0.001 | |||

| Neck pain | 0.33 (0.14, 0.50) | 0.19 (0.04, 0.33) | |||||||||||

| ADE | 0.34 (0.0, 0.48) | 0 (0,0) | 0.66 (0.50, 0.82) | 2127 | 2364.49 | −1889.51 | |||||||

| ACE | 0.29 (0, 0.48) | 0.04 (0, 0.32) | 0.67 (0.52, 0.87) | 2127 | 2364.44 | −1889.56 | |||||||

| AE | ACE | 0.34 (0.18, 0.48) | / | 0.66 (0.52, 0.82) | 2128 | 2364.49 | −1891.51 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.82 | |||

| CE | ACE | / | 0.24 (0.12, 0.35) | 0.76 (0.65, 0.88) | 2128 | 2365.97 | −1890.03 | 1.53 | 1 | 0.22 | |||

| E | AE | / | / | 1 (1, 1) | 2129 | 2382.30 | −1875.70 | 17.81 | 1 | <0.001 | |||

| Sleep quality | 0.35 (0.24, 0.45) | 0.14 (0.05, 0.23) | |||||||||||

| ACE | 0.34 (0.15, 0.43) | 0 (0,0) | 0.66 (0.57, 0.76) | 1930 | 5396.81 | 1536.81 | |||||||

| ADE | 0.19 (0, 0.42) | 0.18 (0, 0.45) | 0.64 (0.54, 0.74) | 1930 | 5396.08 | 1536.08 | |||||||

| AE | ADE | 0.34 (0.25, 0.43) | / | 0.66 (0.57, 0.75) | 1931 | 5396.81 | 1534.81 | 0.73 | 1 | 0.39 | |||

| E | AE | / | / | 1 (1, 1) | 1932 | 5440.17 | 1576.17 | 43.36 | 1 | <0.001 |

A, additive genetic influence; C, shared environmental influence; D, dominant genetic influence; E, non‐shared environmental influence; ‐2LL, negative 2 log‐likelihood; AIC, Akaike’s information criterion; CI, confidence interval; Df, degrees of freedom; P‐value, significance value of the likelihood‐ratio chi‐square test; rDZ, dizygotic correlations; rMZ, monozygotic correlations. Bold text indicates best fitting models.

The best fit was finally provided by an AE model for each of the pain phenotypes. The heritability value (variance explained by genetic factors) was 27% (95% CI: 11 –41%) for LBP and 34% (95% CI: 18 –48%) for NP while the rest of the variance was attributable to non‐shared environmental factors. Likewise, in the case of sleep quality, the non‐additive genetic component could be dropped and the best fit was provided by an AE model. For this phenotype 34% (95% CI: 25–43%) of the variance was explained by genetic factors and 66% (95% CI: 57–75%) by non‐shared environmental factors. Sensitivity analyses including psychological distress (depression/anxiety) as a covariate showed highly similar heritability estimates (23%, 31% and 32% for LBP, NP and sleep quality respectively).

3.3. Associations between back pain and sleep quality

Phenotypic correlations between sleep quality and back pain traits were similarly low but significant (r = 0.22; 95% CI: 0.16, 0.28; and r = 0.23; 95% CI: 0.17, 0.29 for NP and LBP respectively). As expected, however, correlation between NP and LBP was high (r = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.55, 0.66) (Table S2).

Figure 1 summarizes the results for the common pathway model with two latent factors that were fitted in order to explore the association between traits. First of all, the variance of the latent back pain factor encompassing NP and LBP is explained by both genetic (41% [38% + 3%]) and environmental (59% [54% + 5%]) factors. However, these results also show that such influences are barely related to sleep quality. Genes affecting sleep quality only contribute with a 3% of the variance to the common latent back pain variable. Similarly, only 5% of the variance on the latent pain factor is shared with environmental factors related to sleep quality. Regarding the specific pain outcomes, our model shows that less than 2% of the variance in NP or LBP is accounted for genetic factors shared with sleep quality [this result is calculated by multiplying the path by the latent factor loading; 0.03*0.58 (NP) and 0.03*0.63 (LBP)]. Likewise, only about 3% [0.05*0.58 (NP) and 0.05*0.63 (LBP)] of the variance in the back pain outcomes is explained by environmental factors shared with sleep quality. Finally, the model shows that there are significant unique environmental factors specific for NP (33%) and LBP (37%). Yet, specific genetic factors were scant (9%) for NP and negligible for LBP (0%).

As stated above, a three‐variate model was also fitted in order to better characterize associations between traits and obtain complementary additional information (Table S2). As expected, low to moderate genetic correlations were found between sleep quality and NP (r A = 0.21; 95% CI: 0.0, 0.47) and LBP (r A = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.12, 0.65), while a large one was found between NP and LBP (r A = 0.88; 95% CI: 0.80, 1). Analogously, the environmental correlations between sleep and pain were small and barely significant (0.19 and 0.22 between sleep quality and NP and LBP respectively) but of moderate magnitude between NP and LBP (r E = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.36, 62).

4. DISCUSSION

Our results corroborated that the phenotypic correlations between poor sleep quality and chronic back pain, albeit low, were both significant, for NP and LBP. Likewise, as expected, LBP, NP and sleep quality were moderately, yet significantly, heritable. Beyond those previously reported aspects, the global pattern that emerges from our analyses indicates that most of the genetic effects over NP and LBP come from the same set of genes, whereas environmental factors are shared to a lesser extent. Actually, LBP did not show any genetic influence outside the ‘back pain’ latent factor, while NP still keep some specificity since 27.3% of its genetic variance comes from individual genetic factors. The picture for genetic influences on the pain variables is completed by a residual part, similar in both cases, which is shared with sleep quality (NP: 5.3% and LBP 7.3% of their genetic variance).

On the other hand, environmental factors present a somewhat different scenario. Both NP and LBP appear to behave similarly in that about half of their environmental influences are specific; that is both pain locations keep considerable differences regarding what behaviours and environmental conditions are affected by (e.g., type of work, lifestyle, etc.). Nonetheless, the other half is largely due to common factors (e.g., postural hygiene) and, hence circumstances involved in both kinds of pain should also be taken into account. Lastly, again, less than 5% of the environmental variance appears to be shared with sleep quality.

4.1. Comparison with previous studies

Although it is not directly comparable, a previous twin study (Gasperi et al., 2017) reported a higher genetic correlation (r A = −0.69) between poor sleep and pain (assessed with the Brief Pain Inventory) as compared to the ones reported in this study of r A = 0.21 for NP and r A = 0.32 for LBP. They found that approximately 60% of the phenotypic correlation between sleep quality and pain was attributable to genetic effects, in contrast with the low magnitude found in our study. However, our respective results are similar for the other estimated parameters. The aforementioned discrepancy may arise from several compatible explanations. Among them, the pain location assessed, assessment method, age of participants, modelling architecture or power issues.

Consistent with previous reports, the relevant role of genetic factors on the co‐occurrence of NP and LBP was expected (Nyman et al., 2011). Our results are also in line with the hypothesis of a common genetic factor accounting for the occurrence of musculoskeletal pain at multiple body sites (Williams et al., 2010). Although we found a lesser proportion of the phenotypic correlation accounted for by genetic factors (42%), most of the genetic variance for NP (72.5%) and LBP (100%) had a common origin.

With regard to the association between sleep and pain, this was not substantial, yet significant. Given the robustness of the sleep‐pain relationship across a number of studies (Finan et al., 2013), common mechanisms that might underpin this association have been suggested. Those include a modification of the systems involved in the regulation of sleep and pain (opiodergic or dopaminergic neurotransmission systems) (Bonvanie et al., 2016; Finan et al., 2013), known environmental factors such as smoking (Hogg‐Johnson et al., 2008; Manchikanti et al., 2009) or low levels of physical activity (Bonvanie et al., 2016; Simpson et al., 2015) and also the possible contribution of genetic pleiotropy. A possible role of anxiety and depressive symptoms in this association has also been suggested (Bonvanie et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2012), but our analysis including this factor as a covariate did not produce any meaningful change in our estimates, invalidating this explanation for our sample. Recent GWAS have also reported genetic correlations between pain and sleep phenotypes (Bortsov et al., 2020; Freidin et al., 2019; Meng et al., 2020) and have pointed towards a molecular axe of chronic pain perception and processing (Freidin et al., 2019; Johnston et al., 2019) with predominant expression in the central nervous system for genes overlapping with sleep disorders (Bortsov et al., 2020; Freidin et al., 2019). Additionally, the possible influence of altered expression of circadian rythm genes (e.g., CLOCK or BMAL1) on chronic pain has also been postulated (Palada et al., 2020).

4.2. Limitations

This study presents some limitations that should be taken into consideration. Mainly, recall bias cannot be excluded, since outcome variables were assessed by self‐report (Delgado‐Rodriguez & Llorca, 2004), and the cross‐sectional nature of the study precludes the possibility of establishing causation or direction of the relationships between sleep quality, chronic LBP and chronic NP. Furthermore, our measures of NP and LBP are dichotomous and may have difficulties in adequately capture the population variability. Future studies using more precise measures of pain may offer additional perspectives on this question. Finally, as it is common in twin studies, it is necessary to bear in mind that the unique environment estimate (i.e., E) also includes measurement error. Obviously, the smaller this measurement error, the more accurate the estimate of non‐shared environmental variance will be.

4.3. Implications

Our results suggest that environmental factors that are common to chronic NP and LBP might be targeted for improvement of both conditions. For example preventive interventions might be designed for highly physically demanding jobs, and work‐related factors modified (e.g., work postures, movements and organization) (Jensen & Harms‐Ringdahl, 2007; Nyman et al., 2009). Other effective strategies may be practicing physical activity regularly and strengthening and proprioceptive exercises (Jensen & Harms‐Ringdahl, 2007; Krismer & van Tulder, 2007). However, close to half of the environmental variance is specific for NP and LBP, meaning that particular interventions for each condition should also be studied and designed.

Additionally, although with a limited impact, sleep problems can be targeted for improvement and prevention of both chronic LBP and chronic NP. Effective strategies might be the promotion of a good sleep hygiene, cognitive behavioural therapy for sleep, or modification of lifestyle habits (e.g., physical activity, diet and caffeine use) (McBeth et al., 2015; Redeker et al., 2019). Alternatively, sleep medication might be used, or also pain medication that might consequentially improve sleep quality (McBeth et al., 2015). However, long‐term effects and issues regarding tolerance, addiction and potential side‐effects (McBeth et al., 2015; Sateia et al., 2017) in addition to polypharmacy because of concurrent co‐morbidities (especially in older adults) should be considered (McBeth et al., 2015).

Finally, our results suggest that the same set of genes and, consequently, the same set of pathways and mechanisms appears to affect both LBP and NP. Therefore, uncovering those genetic factors affecting both conditions and the precise identification of such pathways might be an important approach for improving care and adjusting treatments, in particular pharmacological approaches, to individual characteristics.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JRO, JJMV and AA contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was coordinated and supervised by JRO and EC. Analyses were performed by JJMV and JRO. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JJMV and AA under the supervision of JRO, JMS and PF. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Data S1

Madrid‐Valero, J. J. , Andreucci, A. , Carrillo, E. , Ferreira, P. H. , Martínez‐Selva, J. M. , & Ordoñana, J. R. (2022). Nature and nurture. Genetic and environmental factors on the relationship between back pain and sleep quality. European Journal of Pain, 26, 1460–1468. 10.1002/ejp.1973

Juan J. Madrid‐Valero and A. Andreucci have contributed equally.

Funding information

GRANT SUPPORT: Funding: Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades ‐ Spain (RTI2018‐095185‐B‐I00) co‐funded by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER).

Contributor Information

Juan J. Madrid‐Valero, Email: juanjose.madrid@ua.es.

Juan R. Ordoñana, Email: ordonana@um.es.

REFERENCES

- Akaike, H. (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52, 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Andreucci, A. , Madrid Valero, J. J. , Ferreira, P. H. , & Ordonana, J. R. (2020). Sleep quality and chronic neck pain: A co‐twin study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 16, 679–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvanie, I. J. , Oldehinkel, A. J. , Rosmalen, J. G. M. , & Janssens, K. A. M. (2016). Sleep problems and pain: A longitudinal cohort study in emerging adults. Pain, 157, 957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortsov, A. V. , Parisien, M. , Khoury, S. , Zaykin, D. V. , & Amy, E. (2020). Genome‐wide analysis identifies significant contribution of brain‐expressed genes in chronic, but not acute, back pain. MedRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Boudebesse, C. , Geoffroy, P. A. , Bellivier, F. , Henry, C. , Folkard, S. , Leboyer, M. , & Etain, B. (2014). Correlations between objective and subjective sleep and circadian markers in remitted patients with bipolar disorder. Chronobiology International, 31, 698–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D. , Reynolds, C. , Monk, T. , Berman, S. , & Kupfer, D. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28, 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J. S. , & Andrykowski, M. A. (1998). Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 45, 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado‐Rodriguez, M. , & Llorca, J. (2004). Bias. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 635–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan, P. H. , Goodin, B. R. , & Smith, M. T. (2013). The association of sleep and pain: An update and a path forward. The Journal of Pain, 14, 1539–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidin, M. B. , Tsepilov, Y. A. , Palmer, M. , Karssen, L. C. , Suri, P. , Aulchenko, Y. S. , & Williams, F. M. (2019). Insight into the genetic architecture of back pain and its risk factors from a study of 509,000 individuals. Pain, 160, 1361–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasperi, M. , Herbert, M. , Schur, E. , Buchwald, D. , & Afari, N. (2017). Genetic and environmental influences on sleep, pain, and depression symptoms in a community sample of twins. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79, 646–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartvigsen, J. , Christensen, K. , & Frederiksen, H. (2004). Back and neck pain exhibit many common features in old age: A population‐based study of 4,486 Danish twins 70‐102 years of age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 29, 576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartvigsen, J. , Nielsen, J. , Kyvik, K. O. H. M. , Fejer, R. , Vach, W. , Iachine, I. , & Leboeuf‐Yde, C. (2009). Heritability of spinal pain and consequences of spinal pain: A comprehensive genetic epidemiologic analysis using a population‐based sample of 15,328 twins ages 20‐71 years. Arthritis Care and Research, 61, 1343–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartvigsen, J. , Pedersen, H. C. , Frederiksen, H. , & Christensen, K. (2005). Small effect of genetic factors on neck pain in old age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 30, 206–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henschke, N. , Kamper, S. J. , & Maher, C. G. (2015). The epidemiology and economic consequences of pain. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90, 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hestbaek, L. , Iachine, I. A. , Leboeuf‐Yde, C. , Kyvik, K. O. , & Manniche, C. (2004). Heredity of low Back pain in a young population: A classical twin study. Twin Research, 7, 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg‐Johnson, S. , van der Velde, G. , Carroll, L. J. , Holm, L. W. , David Cassidy, J. , Guzman, J. , Pierre Côté, Ʈ. , Haldeman, S. , Ammendolia, C. , Carragee, E. , Hurwitz, E. , Nordin, M. , & Peloso, P. (2008). The burden and determinants of neck pain in the general population results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 33, 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica (2012). Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2011‐2012. Metodología. Madrid: INE

- Jensen, I. , & Harms‐Ringdahl, K. (2007). Neck pain. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology, 21, 93–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, K. J. A. , Adams, M. J. , Nicholl, B. I. , Ward, J. , Strawbridge, R. J. , Ferguson, A. , McIntosh, A. M. , Bailey, M. E. S. , & Smith, D. J. (2019). Genome‐wide association study of multisite chronic pain in UKbiobank. PLoS Genetics, 15, 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopik, V. S. , Neiderhiser, J. M. , DeFries, J. C. , & Plomin, R. (2017). Behavioral genetics. Worth Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Krismer, M. , & van Tulder, M. (2007). Low back pain (non‐specific). Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology, 21, 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livshits, G. , Popham, M. , Malkin, I. , Sambrook, P. N. , MacGregor, A. J. , Spector, T. , & Williams, F. M. K. (2011). Lumbar disc degeneration and genetic factors are the main risk factors for low back pain in women: The UKtwin spine study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 70, 1740–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, A. J. , Andrew, T. , Sambrook, P. N. , & Spector, T. D. (2004). Structural, psychological, and genetic influences on low back and neck pain: A study of adult female twins. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 51, 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid‐Valero, J. J. , Rubio‐Aparicio, M. , Gregory, A. M. , Sánchez‐Meca, J. , & Ordoñana, J. R. (2020). Twin studies of subjective sleep quality and sleep duration, and their behavioral correlates: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of heritability estimates. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 109, 78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid‐Valero, J. J. , Sánchez‐Romera, J. F. , Gregory, A. M. , Martínez‐Selva, J. M. , & Ordoñana, J. R. (2018). Heritability of sleep quality in a middle‐aged twin sample from Spain. Sleep, 41, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti, L. , Singh, V. , Datta, S. , Cohen, S.P. , Hirsch, J. a (2009). Comprehensive review of epidemiology, scope, and impact of spinal pain. Pain Physician 12, E35–E70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBeth, J. , Wilkie, R. , Bedson, J. , Chew‐Graham, C. , & Lacey, R. J. (2015). Sleep disturbance and chronic widespread pain. Current Rheumatology Reports, 17, 469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng, A. W. , Chan, B. W. , Harris, C. , Freidin, M. B. , Harry, L. , Adams, M. J. , Campbell, A. , Hayward, C. , Zheng, H. , Colvin, L. A. , Hales, T. G. , Palmer, C. N. A. , Williams, F. M. K. , Mcintosh, A. , & Smith, B. H. (2020). A genome‐wide association study finds genetic variants associated with neck or shoulder pain in UKbiobank. Human Molecular Genetics, 29, 1396–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale, M. C. , & Cardon, L. R. (1992). Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families. Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, M. C. , Hunter, M. D. , Pritikin, J. N. , Zahery, M. , Brick, T. R. , Kirkpatrick, R. M. , Estabrook, R. , Bates, T. C. , Maes, H. H. , & Boker, S. M. (2016). OpenMx 2.0: Extended structural equation and statistical modeling. Psychometrika, 81, 535–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, C. , Knudsen, G. , & Steingrímsdóttir, Ó. (2012). Twin studies of pain. Clinical Genetics, 82, 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman, T. , Mulder, M. , Iliadou, A. , Svartengren, M. , & Wiktorin, C. (2009). Physical workload, low back pain and neck‐shoulder pain: A Swedish twin study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 66, 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman, T. , Mulder, M. , Iliadou, A. , Svartengren, M. , & Wiktorin, C. (2011). High heritability for concurrent low back and neck‐shoulder pain: A study of twins. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 36, 1469–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñana, J. R. , Carrillo, E. , Colodro‐Conde, L. , García‐Palomo, F. J. , González‐Javier, F. , Madrid‐Valero, J. J. , Martínez Selva, J. M. , Monteagudo, O. , Morosoli, J. J. , Pérez‐Riquelme, F. , & Sánchez‐Romera, J. F. (2019). An update of twin research in Spain: The Murcia twin registry. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 22, 667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñana, J. R. , Rebollo‐Mesa, I. , Carrillo, E. , Colodro‐Conde, L. , García‐Palomo, F. J. , González‐Javier, F. , Sánchez‐Romera, J. F. , Aznar Oviedo, J. M. , De Pancorbo, M. M. , & Pérez‐Riquelme, F. (2013). The Murcia twin registry: A population‐based registry of adult multiples in Spain. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 16, 302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñana, J. R. , Sánchez Romera, J. F. , Colodro‐Conde, L. , Carrillo, E. , González‐Javier, F. , Madrid‐Valero, J. J. , Morosoli‐García, J. J. , Pérez‐Riquelme, F. , & Martínez‐Selva, J. M. (2018). The Murcia twin registry. A resource for research on health‐related behaviour. Gaceta Sanitaria, 32, 92–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palada, V. , Gilron, I. , Canlon, B. , Svensson, C. I. , & Kalso, E. (2020). The circadian clock at the intercept of sleep and pain. Pain, 161, 894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, M. B. , Morosoli, J. J. , Ferreira, M. L. , Madrid‐Valero, J. J. , Refshauge, K. , Ferreira, P. H. , & Ordoñana, J. R. (2018). Genetic and environmental contributions to sleep quality and low back pain: A population‐based twin study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 80, 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, R. , & De Charro, F. (2001). EQ‐5D: A measure of health status from the EuroQol group. Annals of Medicine, 33, 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos‐Goñi, J. M. , Craig, B. M. , Oppe, M. , Ramallo‐Fariña, Y. , Pinto‐Prades, J. L. , Luo, N. , & Rivero‐Arias, O. (2018). Handling data quality issues to estimate the Spanish EQ‐5D‐5L value set using a hybrid interval regression approach. Value Health, 21, 596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raniti, M. B. , Waloszek, J. M. , Schwartz, O. , Allen, N. B. , & Trinder, J. (2018). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in community‐based adolescents. Sleep, 41, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redeker, N. S. , Caruso, C. C. , Hashmi, S. D. , Mullington, J. M. , Grandner, M. , & Morgenthaler, T. I. (2019). Workplace interventions to promote sleep health and an alert, healthy workforce. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 15, 649–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichborn‐Kjennerud, T. , Stoltenberg, C. , Tambs, K. , Roysamb, E. , Kringlen, E. , Torgersen, S. , & Harris, J. R. (2002). Back‐neck pain and symptoms of anxiety and depression: A population‐based twin study. Psychological Medicine, 32, 1009–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid, K. J. , Harker, J. , Bala, M. M. , Truyers, C. , Kellen, E. , Bekkering, G. E. , & Kleijnen, J. (2011). Epidemiology of chronic non‐cancer pain in Europe: Narrative review of prevalence, pain treatments and pain impact. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 27, 449–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijsdijk, F. (2005). Common pathway model. In Howell D. C. & Everitt B. S. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science (pp. 330–331). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Rijsdijk, F. V. , & Sham, P. C. (2002). Analytic approaches to twin data using structural equation models. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 3, 119–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royuela‐Rico, A. , & Macías‐Fernández, J. (1997). Propiedades Clinimetricas de la Version Castellana del Cuestionario de Pittsburg. Vigilia‐Sueño, 9, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sateia, M. J. , Buysse, D. J. , Krystal, A. D. , Neubauer, D. N. , & Heald, J. L. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: An American Academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13, 307–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, L. , McArdle, N. , Eastwood, P. R. , Ward, K. L. , Cooper, M. N. , Wilson, A. C. , Hillman, D. R. , Palmer, L. J. , & Mukherjee, S. (2015). Physical inactivity is associated with moderate‐severe obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11, 1091–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafti, M. (2009). Genetic aspects of normal and disturbed sleep. Sleep Medicine, 10, S17–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij, K. J. H. , Mosing, M. A. , Zietsch, B. P. , & Medland, S. E. (2012). Estimating heritability from twin studies. Methods in Molecular Biology, 850, 151–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos, T. , Abajobir, A. A. , Abbafati, C. , Abbas, K. M. , Abate, K. H. , Abd‐Allah, F. , Abdulle, A. M. , Abebo, T. A. , Abera, S. F. , Aboyans, V. , Abu‐Raddad, L. J. , Ackerman, I. N. , Adamu, A. A. , Adetokunboh, O. , Afarideh, M. , Afshin, A. , Agarwal, S. K. , Aggarwal, R. , Agrawal, A. , et al. (2017). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990‐2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet, 390, 1211–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, F. M. K. , Spector, T. D. , & MacGregor, A. J. (2010). Pain reporting at different body sites is explained by a single underlying genetic factor. Rheumatology, 49, 1753–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. , Lam, S. P. , Li, S. X. , Tang, N. L. , Yu, M. W. M. , Li, A. M. , & Wing, Y. K. (2012). Insomnia, sleep quality, pain, and somatic symptoms: Sex differences and shared genetic components. Pain, 153, 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1