Abstract

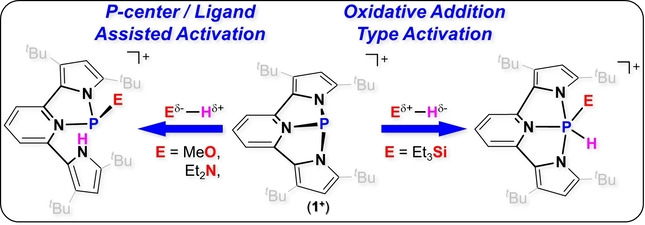

A geometrically constrained phosphenium cation in bis(pyrrolyl)pyridine based NNN pincer type ligand (1+ ) was synthesized, isolated and its preliminary reactivity was studied with small molecules. 1+ reacts with MeOH and Et2NH, activating the O−H and N−H bonds via a P‐center/ligand assisted path. The reaction of 1+ with one equiv. of H3NBH3 leads to its dehydrogenation producing 5. Interestingly, reaction of 1+ with an excess H3NBH3 leads to phosphinidene (PI) species coordinating to two BH3 molecules (6). In contrast, [1+ ][OTf] reacts with Et3SiH by hydride abstraction yielding 1‐H and Et3SiOTf, while [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] reacts with Et3SiH via an oxidative addition type reaction of Si−H bond to P‐center, affording a new PV compound (8). However, 8 is not stable over time and degrades to a complex mixture of compounds in matter of minutes. Despite this, the ability of [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] to activate Si−H bond could still be tested in catalytic hydrosilylation of benzaldehyde, where 1+ closely mimics transition metal behaviour.

Keywords: Phosphenium Cation, Phosphinidene, Phosphorus, Silane, Small Molecule Activation

Geometrically constrained phosphenium cation 1+ was synthesized and its reactivity was studied. While 1+ reacts with MeOH and Et2NH via P‐center/ligand assisted path, its reaction with Et3SiH proceeds via oxidative addition type reaction affording new PV intermediate. The ability of 1+ to activate Si−H bond was tested in catalytic hydrosilylation of benzaldehyde, where 1+ closely mimics transition metal behaviour.

Introduction

Constraining the geometry of p‐block elements through their inclusion in rigid pincer type ligands allows the formation of new compounds with non‐VSEPR geometries. Such alterations in geometry bring about a reorganization in their molecular orbitals, in particular in frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs), which as a result has a significant impact on the reactivity of these geometrically distorted centers. [1] Such as, decreasing the energetic gap between the HOMO and LUMO results in both more nucleophilic and electrophilic (i.e., ambiphilic) reactivity, thus unlocking new modes of activation of small molecules via oxidative addition type reactions usually associated with transition metal complexes. [2] For this reason, this method is increasingly utilized by the chemical community in order to expand the capabilities of p‐block elements beyond their traditional reactivity.

Recently, a number of geometrically constrained σ3PIII based compounds have been synthesized and used in activation of small molecules. Indeed, phosphorus and its heavier congeners have been identified as privileged for transition metal mimetic chemistry due to their readily available E n /E n+2 redox couples.[ 3 , 4 ] Radosevich reported that a “T”‐shaped PIII center in an ONO platform [5] facilitates the catalytic transfer hydrogenation from H3NBH3 to diazabenzene, [6] as well as it reacts with RNH2 via an oxidative addition type reaction of the N−H bond to P‐center giving PV species. [7] Aldridge and Goicoechea introduced a geometrically constrained PIII center in an ONO platform, which activates HO−H, H2N−H bonds, [8] and various X2 (X=Cl, Br, I) [9] via an oxidative addition type reaction. Kinjo and co‐workers synthesized a diazadiphosphapentalene with a geometrically constrained P‐center capable of activating the H2N−H bond and dehydrogenating H3NBH3 via a unique σ‐bond metathesis pathway.[ 10 , 11 ] Later, Radosevich introduced a PIII center in an NNN platform, which was shown to activate RO−H, [12] R2N−H, [12] H−Bpin, [13] and Ar−F bonds. [14] We endeavored to increase the ambiphilicity of PIII compounds by geometrically constricting a positively charged PIII center in a rigid ONO platform, thus synthesizing the first geometrically constrained phosphenium cation, [15] that activated HO−H, RO−H, and H2N−H bonds via an oxidative addition type reaction to a PIII center producing new phosphonium cations (PV). [15]

Herein we report the synthesis, structure, and preliminary reactivity of a geometrically constrained phosphenium cation (1+ ) in bis(pyrrolyl)pyridine based NNN pincer type ligand. 1+ has a dual reactivity, and activates small molecules by two different pathways i.e., P‐center/ligand assisted pathway in activation of MeOH, Et2NH and H3NBH3 or by an oxidative addition type reaction to P‐center in activation of Et3SiH. The mechanisms of both pathways were studied experimentally and by density functional theory (DFT) computations. The activation of Et3SiH was tested in a catalytic hydrosilylation reaction of benzaldehyde and closely mimics the mechanism of catalytic hydrosilylation with precious transition metals.[ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]

Results and Discussion

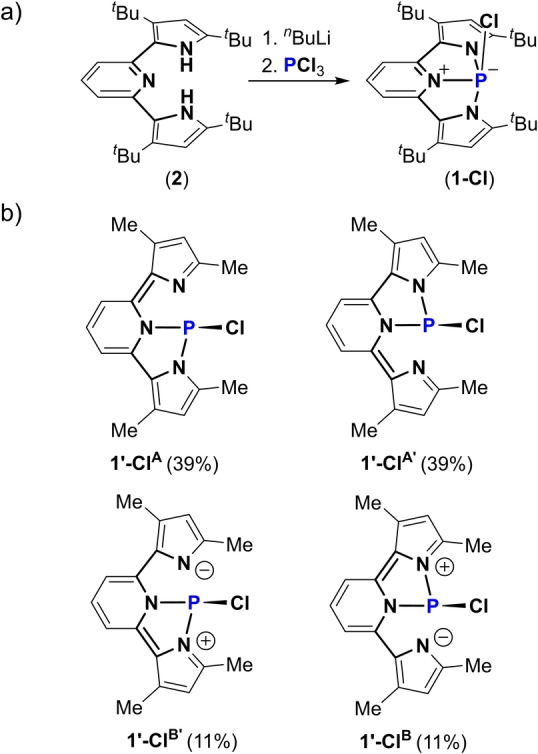

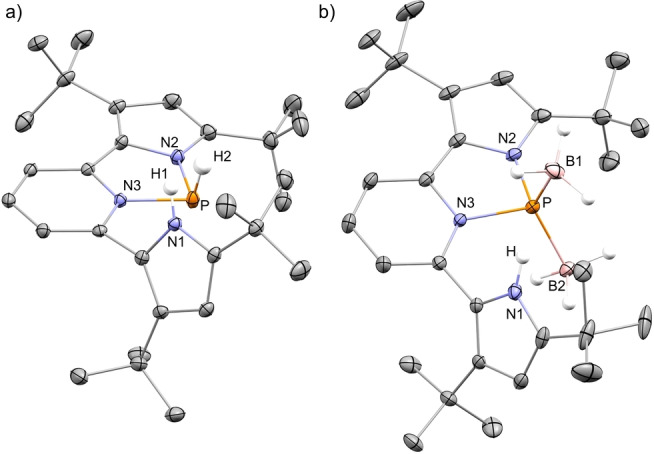

First the chlorophosphine in NNN pincer type ligand (1‐Cl) was prepared by the double deprotonation of bis(pyrrolyl)pyridine (2) with 2 equiv of n BuLi followed by the addition of PCl3 at −78 °C (Scheme 1a). 1‐Cl was crystallized from hexane by slow evaporation, affording dark purple crystalline needles. The molecular structure of 1‐Cl was determined by X‐ray crystallography and shown in Figure 1a. [20] Interestingly, 1‐Cl exhibits a tetracoordinated P‐center in which the P and all N atoms are located on the same plane and the Cl atom is positioned above the P atom with a slight deviation from perpendicularity to this plane (∠N1−P−Cl=90.4, ∠N2−P−Cl=89.4, and ∠N3−P−Cl=97.2°). The N−P bonds in 1‐Cl are all of different lengths, N3−P bond length of 1.806(2) Å is in the range of N−P single bonds[ 8 , 10 , 12 ] and shorter than N1−P of 1.949(2) Å and N2−P of 1.915(1) Å, which both are longer than a typical N−P single bond. [21] To understand the obtained solid state structure of 1‐Cl, we DFT calculated its model system, 1′‐Cl (with Me substituents), using B3LYP−D3(BJ)/def2TZVP level of theory[ 22 , 23 , 24 ] and analyzed its resonance structures (RS) using natural resonance theory (NRT). [25] Thus, the structure of 1′‐Cl is best described by four RSs: 1′‐ClA , 1′‐ClA′ , 1′‐ClB and 1′‐ClB′ (Scheme 1b). This analysis explains the elongation of the N1−P and N2−P bonds in 1‐Cl. Noteworthy, these resonance structures are consistent with previously reported compounds in similar ligand scaffolds.[ 26 , 27 ]

Scheme 1.

a) Synthesis of 1‐Cl; b) RSs of 1′‐Cl obtained from NRT analysis.

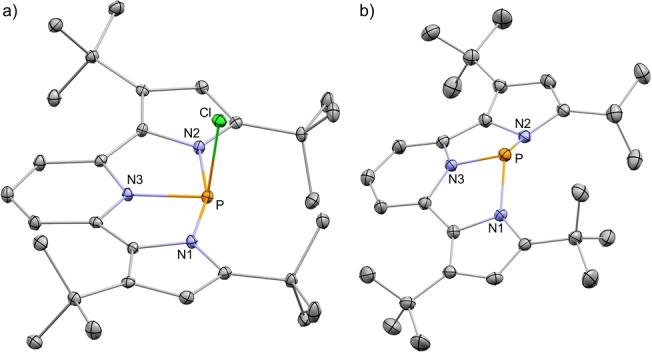

Figure 1.

a) POV‐ray depiction of 1‐Cl; b) POV‐ray depiction of 1+ . Thermal ellipsoids at 30 % probability, hydrogen atoms and TfO− were omitted for clarity.

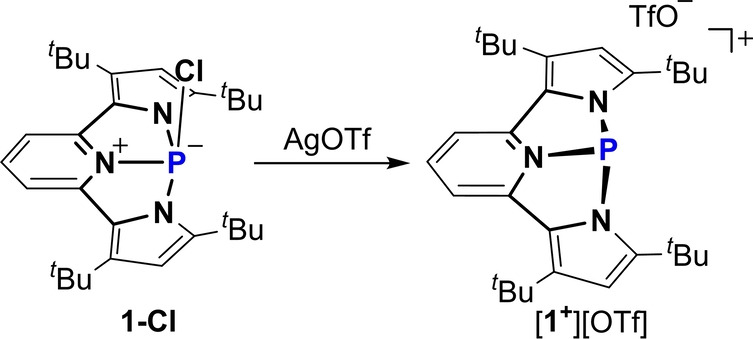

In order to obtain the desired 1+ , 1‐Cl was reacted with AgOTf in CH2Cl2 at r.t., which produced the desired 1+ with TfO− counteranion, [1+ ][OTf] (Scheme 2). The 31P NMR chemical shift of [1+ ][OTf] at 112.05 ppm (compared to 15.69 ppm for 1‐Cl) supported the formation of this salt as a separated ion pair in solution. Crystalline [1+ ][OTf] was obtained by slow precipitation from a saturated toluene solution at −33 °C, and its structure determined by X‐ray crystallography (Figure 1b). [20] Similarly to the observed separated ion pair [1+ ][OTf] in solution, also in solid state there is no P−O bond between the P atom and TfO− anion with the shortest P⋅⋅⋅O distance being 2.99 Å. The structural analysis of 1+ shows that, in contrast to 1‐Cl, all three N−P bonds (N3−P 1.752(3), N1−P 1.781(2), and N2−P 1.786(3) Å) are in the range of a typical N−P single bond.[ 8 , 10 , 12 ] The P‐center in 1+ is pyramidalized with bond angles around the phosphorus atom being ∠N1−P−N3=84.6, ∠N2−P−N3=85.2 and ∠N1−P−N2=123.4°, which shows a strong deviation from a local C3v symmetry, which is typical to trigonal pyramidal σ3P centers. Thus, the NNN ligand in 1+ enforces a distorted trigonal pyramid geometry with C s symmetry.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of [1 +][OTf].

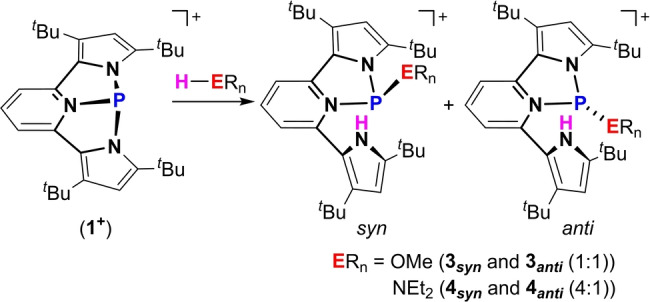

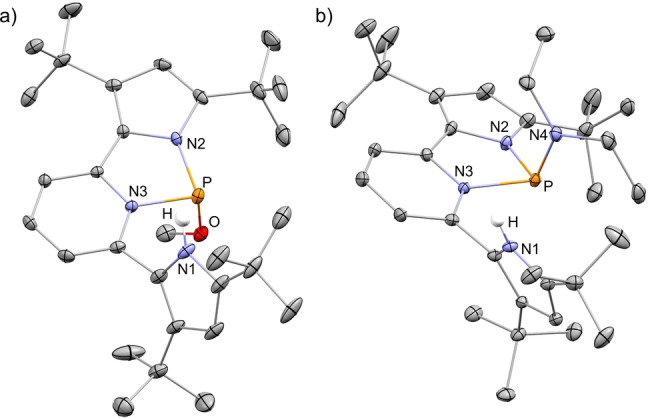

Having synthesized the desired geometrically constrained 1+ , we proceeded to screen its reactivity with small molecules. First [1+ ][OTf] was reacted with MeOH that led to a mixture of two isomers in 1 : 1 ratio (Scheme 3) as was measured by 31P NMR signaling at 95.53 and 101.14 ppm. Multinuclear NMR experiments revealed that both isomers are products of MeO−H bond activation via a P‐center/ligand assisted pathway, in which the proton resides on the pyrrole‘s nitrogen and the methoxy‐ group is attached to the P‐center (3 anti and 3 syn ). Crystallization from a saturated toluene solution containing the mixture of 3 anti and 3 syn at −33 °C led to the precipitation of crystalline 3 anti , as was determined using X‐ray crystallography (Figure 2a). [20]

Scheme 3.

Activation of MeO−H and Et2N−H bonds by [1+ ][OTf] producing 3 anti , 3 syn and 4 anti , 4 syn , respectively.

Figure 2.

a) POV‐ray depiction of 3 anti ; b) POV‐ray depiction of 4 syn . Thermal ellipsoids at the 30 % probability level, non‐relevant hydrogen atoms and TfO− were omitted for clarity.

The reaction with Et2NH proceeded in a similar fashion to the one with MeOH i.e., by activation of the Et2N−H bond, through a P‐center/ligand assisted pathway producing two isomers, 4 anti and 4 syn (Scheme 3). However, in contrast to the activation of MeOH, in this case the ratio between 4 anti and 4 syn was 1 : 4, respectively, as was determined from the integration of the corresponding signals in 31P NMR (96.23 ppm for 4 anti and 97.42 ppm for 4 syn ). The different ratios of products in the reaction of 1+ with MeOH (3 anti : 3 syn (1 : 1)) in comparison to the reaction with Et2NH (4 anti : 4 syn (1 : 4)) could be explained by a higher steric bulk of the Et2N‐ group compared to MeO‐ group, which precludes easy rotational isomerization from 4 syn to 4 anti . The crystals of 4 syn were obtained by slow evaporation of a saturated benzene solution containing both 4 anti and 4 syn at r.t. The molecular structure of 4 syn was determined by X‐ray crystallography (Figure 2b). [20]

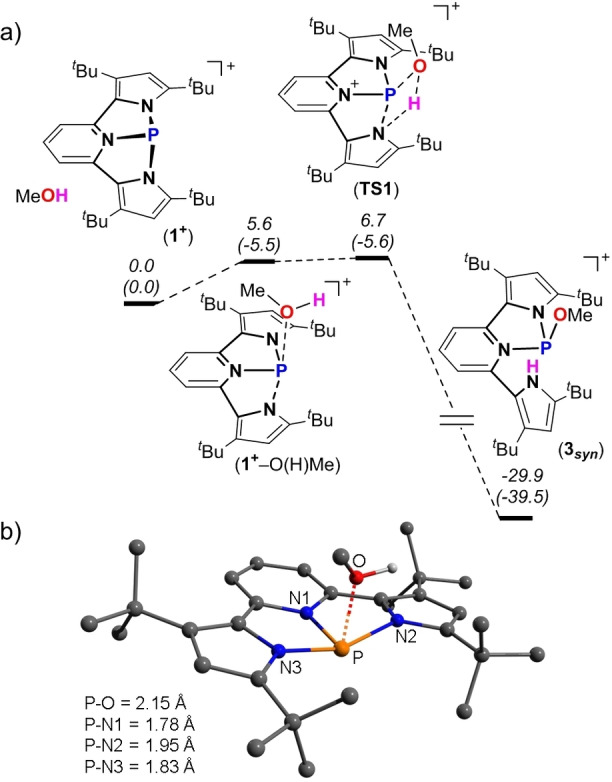

The mechanism of activation of MeO−H bond by 1+ was investigated using a DFT calculation at the BP86‐D3/def2TZVP level of theory.[ 22 , 23 , 24 ] Based on these calculations, the first step of this reaction is the formation of 1+ −O(H)Me adduct, which is exothermic (ΔH=−5.5 kcal mol−1) and slightly endergonic (ΔG=5.6 kcal mol−1) (Figure 3a). Interestingly, the optimized structure of 1+ −O(H)Me (Figure 3b) resembles that of 1‐Cl in its different P−N bond lengths with a shorter (1.78 Å) single P−N1 bond, slightly elongated P−N3 bond (1.83 Å), and a long (1.95 Å) P−N2 bond. This indicated that the longest P−N2 bond in 1+ −O(H)Me is the one that will dissociate and assist in proton abstraction to give the final product 3 syn . This final step is strongly exothermic and exergonic (ΔH=−39.5 and ΔG=−29.9 kcal mol−1), with a very low lying transition state (TS1) of ΔG ≠=1.1 kcal mol−1 (Figure 3a). Similar activation of O−H and N−H bonds by PIII in NNN ligand platform was previously observed. [12] However, in contrast to our result the anti and syn isomers were found to be in equilibrium with the PV phosphorane species, [12] while in our case no PV species were observed experimentally (see Figure S25 for VT NMR experiment).

Figure 3.

a) DFT calculated potential energy surface (PES) for the activation of MeO−H bond by 1+ . Free Gibbs energies (enthalpies) are given relative to the starting materials; b) DFT optimized structure of 1+ ‐O(H)Me and bond lengths around P atom.

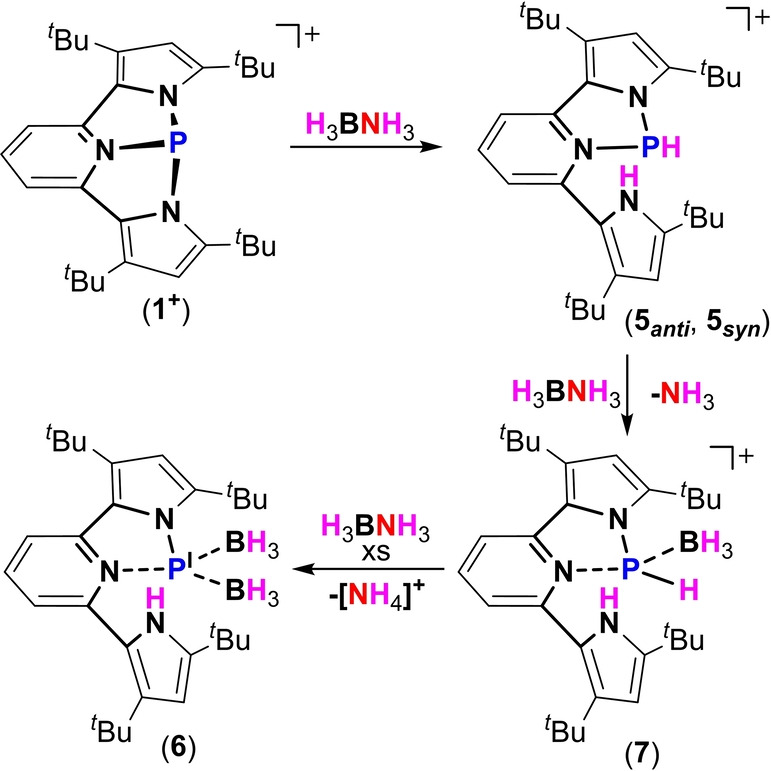

Although [1+ ][OTf] does not react with H2 even under forcing conditions (4 atm. at 100 °C), it readily reacts with H3NBH3 (1 equiv) at ambient temperature to give a mixture of two isomers 5 anti and 5 syn (1 : 3) (Scheme 4). The 31P NMR spectrum of 5 anti and 5 syn shows two doublets at δ=59.36 ( 1 J (PH)=216 Hz) and 60.01 ( 1 J (PH)=178 Hz) ppm. This activation is again a result of a P‐center/ligand assisted process similarly to the activation of MeOH and Et2NH (Scheme 3). Crystals of 5 syn were obtained by slow evaporation of a C6H6/hexane (1 : 1) solution containing both 5 anti and 5 syn and its molecular structure was determined by X‐ray crystallography (Figure 4a). [20]

Scheme 4.

Reaction of [1+ ][OTf] with one equiv. of H3BNH3 producing 5 anti and 5 syn and with an excess of H3BNH3 producing phosphinidene 6 via stable intermediate 7.

Figure 4.

a) POV‐ray depiction of 5 syn ; b) POV‐ray depiction of 6. Thermal ellipsoids at the 30 % probability level, non‐relevant hydrogen atoms and TfO− were omitted for clarity.

Interestingly, while attempting a catalytic hydrogen transfer from H3NBH3 to a 1,1‐diphenylethylene, we realized that while the olefin remains unchanged, the excess of H3NBH3 reacts with [1+ ][OTf] to produce a new formally PI phosphinidene specie 6 (Scheme 4). To study this reaction in detail, we performed a stepwise reaction of [1+ ][OTf] with H3NBH3. The reaction of [1+ ][OTf] with 1 equiv of H3NBH3 consistently gives 5 anti and 5 syn , while 3 equiv of H3NBH3 give 6 after stirring for 4 days at r.t. 6 was crystallized from hexane by slow evaporation and its molecular structure was determined by X‐ray crystallography (Figure 4b). [20] In 6, the phosphorus center is bound to an anionic pyrrole arm, to a neutral Lewis basic pyridine and to two neutral Lewis acidic BH3 molecules, thus confirming its formal PI oxidation state. The two BH3 groups in 6 are inequivalent with respect to the detached pyrrole arm (Figure 4b). The 31P NMR of 6 resonates as a singlet at 216.40 ppm, indicating the sole possible isomer, since the BH3 groups render all possible isomers equivalent. The 11B NMR of 6 shows two broad singlet resonances at −34.46 ppm and −25.75 ppm, consistent with two inequivalent BH3 groups. The loss of symmetry in 6, i.e. two different pyrrole groups, is clearly seen in the 1H NMR, where two sets of signals corresponding to t Bu‐ groups as well as five distinct signals for pyridine were measured (see Supporting Information for NMR spectra). Notably, the transformation of mixture of isomers 5 anti and 5 syn to 6 proceeds through intermediate 7 (Scheme 4). 7 was observed and characterized by multinuclear NMR experiments in the reaction of [1+ ][OTf] with 3 equiv of H3NBH3 as well as independently obtained by reaction of [1+ ][OTf] with two equiv. of H3NBH3 (see Supporting Information for details). Unfortunately, all attempts to crystallize 7, led to its decomposition and therefore, a complete structural elucidation could not be made. The transformation of 5 anti and 5 syn to 7 probably proceeds via an addition of BH3 to the P‐center with concomitant liberation of NH3. Noteworthy, H3NBH3 usually reacts with main‐group compounds by dehydrogenation, [28] while B−N bond dissociation in H3NBH3, although rare, was previously reported.[ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ] Then, a similar reaction possibly occurs between 7 and another equiv. of H3NBH3 providing a second molecule of BH3 along with elimination of [NH4][OTf], giving phosphinidene 6 as the final product (Scheme 4). It is important to mention that the reduction of PIII to PI species using ammonia‐borane was not previously known, and usually requires harsh reducing conditions. In this respect, it is worth mentioning that the opposite reaction in which phosphinidenes (PI) activate NH3, producing new aminophosphines (PIII), was recently reported. [34]

We next proceeded to study the reactivity of [1+ ][OTf] with Et3SiH and HBpin. Noteworthy, in contrast to activation of MeO−H and Et2N−H with a protic hydrogen, in Et3Si−H and H−Bpin the hydrogen is hydridic and therefore a possibility for a different activation path was expected. Interestingly, while [1+ ][OTf] does not react with HBpin, it reacts fast with Et3SiH with concomitant change in color from dark purple to deep red. Monitoring the reaction with 31P NMR reveals that the starting material 1+ , a singlet at 112.05 ppm is consumed, and a new doublet with 1 J(PH)=324 Hz appears at −53.95 ppm, complementary coupling was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum with a doublet resonance at δ=7.96 ppm. This signal, however, disappears within ≈12 h, generating a complex mixture of products. We assumed that the initial signal that we observe in 31P NMR (δ=−53.95 ppm with 1 J(PH)=324 Hz) corresponds to the product of Et3Si−H bond cleavage by [1+ ][OTf] producing 1‐H and Et3SiOTf (Scheme 5). While further reaction between 1‐H and Et3SiOTf leads to a variety of products (see Figure S45).

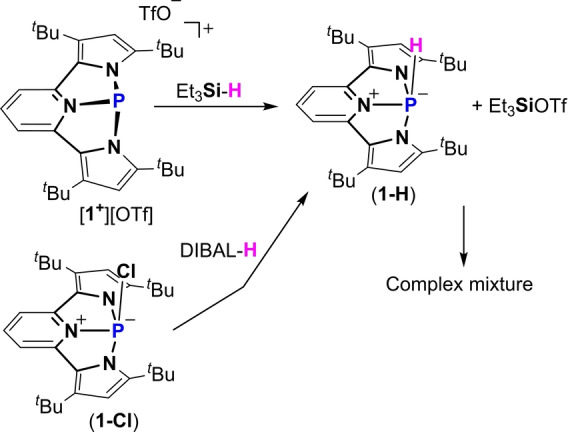

Scheme 5.

Reaction of [1+ ][OTf] with Et3SiH producing 1‐H and Et3SiOTf reaction, and independent synthesis of 1‐H by reduction of 1‐Cl with DIBAL−H.

Noteworthy, the abstraction of a hydride from hydrosilane by a free phosphenium mono‐cation, such as a typical N‐heterocyclic phosphenium cation (NHP), was not previously shown to the best of our knowledge. This points to the high Lewis acidity of 1+ , which in synergy with the TfO− anion leads to the cleavage of Et3Si−H bond (see Supporting Information for DFT calculated mechanism of Et3Si−H bond cleavage by [1+ ][OTf] and for the fluoride ion affinity (FIA) studies of 1+ ). Noteworthy, hydride abstraction from hydrosilane by Mo‐phosphenium complex [35] and by phosphenium dications [36] were reported before.

To support this, we independently synthesized 1‐H, by reacting 1‐Cl with DIBAL‐H in THF at r.t. Importantly, the NMR spectra of independently synthesized 1‐H and the non‐stable one obtained from the reaction of [1+ ][OTf] with Et3SiH were nearly identical (see Supporting Information). 1‐H was crystallized by slow precipitation from a saturated solution of hexane/toluene (1 : 1) at −33 °C, and its molecular structure was determined using X‐ray crystallography (Figure 5). Noteworthy, 1‐H is stable for weeks, however, upon reaction with Me3SiOTf, a picture similar to the activation of Et3SiH by [1+ ][OTF] is observed in 31P NMR spectrum (see Figure S44 and S45).

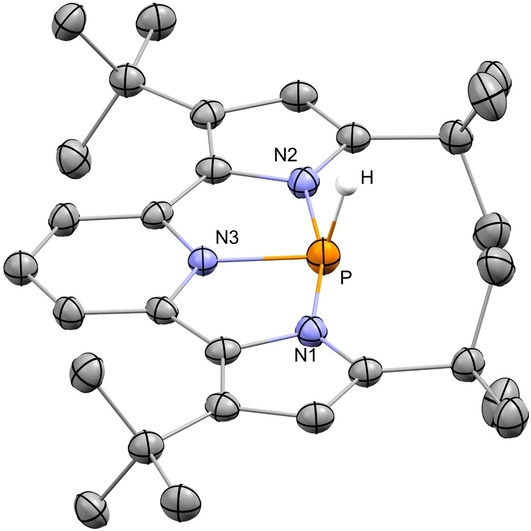

Figure 5.

POV‐ray depiction of 1‐H. Thermal ellipsoids at the 30 % probability level, non‐relevant hydrogens were omitted for clarity.

The structure of 1‐H closely resembles the structure of 1‐Cl, with all N atoms (N1, N2 and N3) and P atom on the same plane, and the H atom positioned above P atom and slightly tilted from this plane (∠N3−P−H 106.11°). The P−N1 and P−N2 have the same bond lengths and are both elongated (1.916 Å). The P−N3 bond length is in the range of a typical P−N single bond length (1.801 Å). Meaning that a similar picture of resonance forms as the one for 1‐Cl (Scheme 1b) can be described for 1‐H. The P−H bond length in 1‐H of 1.361 Å is in the range of previously reported P−H bonds.[ 37 , 38 ]

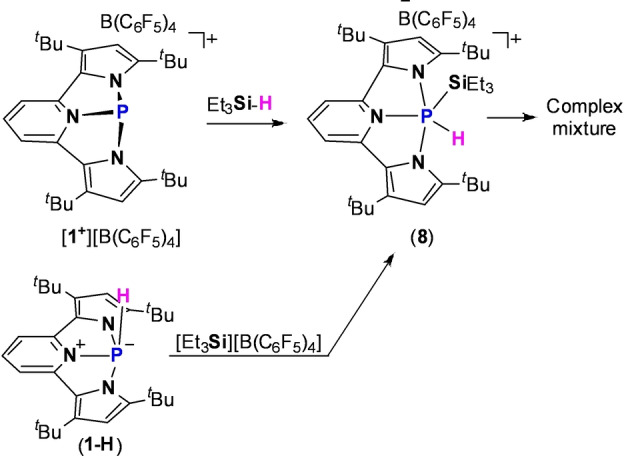

Since the TfO− anion in [1+ ][OTf] salt was not innocent in the activation of Et3Si−H bond, we decided to replace it to the less coordinative anion (C6F5)4B−. Thus, [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] was obtained by reaction of 1‐Cl with [Et3Si][B(C6F5)4]. While the reactivity of [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] with MeOH, Et2NH, H2 and H3NBH3 was similar to [1+ ][OTf], the addition of Et3SiH to [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] did not produce 1‐H, which was evident from 31P NMR, and a new product that signaled at δ=−88.73 ppm with 1 J(PH) coupling constant of 577 Hz was formed, complementary coupling was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum with a doublet resonance at δ=9.56 ppm. Due to the region of the 31P NMR signal, which is typical to PV species, the one bond coupling to 1H nucleus and the symmetry of the obtained system as analyzed from 1H NMR (see Figure S52), we assumed that the obtained product is the product of the oxidative addition type reaction of the Et3Si−H bond to a P‐center in 1+ , product 8 (Scheme 6). Unfortunately, unambiguous determination of 8 was not possible, since 8 is unstable and within minutes produces a complicated mixture of products that expectedly resembles the mixture obtained from the reaction of Et3SiH and [1+ ][OTf] (Scheme 5) as was measured by 31P NMR (see Figure S51).

Scheme 6.

Oxidative addition type reaction of Et3Si−H bond to an ambiphilic P‐center in [1 +][B(C6F5)4] giving intermediate 8, and independently formed 8 by reaction of 1‐H with [Et3Si][B(C6F5)4].

To support the formation of 8, we tried to synthesize it by reacting 1‐H with [Et3Si][B(C6F5)4], which resulted in formation of 8 as was measured by 31P NMR (Scheme 6), and similarly to 8 obtained from Et3SiH activation by 1+ it was not stable and reacted further.

To the best of our knowledge, oxidative addition type reactions of Si−H bonds at PIII centers were not previously reported. To get further support for the formation of 8, we optimized its structure using DFT computations at the BP86‐D3/def2SVP level of theory[ 22 , 23 , 24 ] and calculated its NMR using PBE1PBE/6‐31G(d,p)[ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ] level of theory. As a result, the computed 31P NMR chemical shift of 8 δ=−88.67 ppm (relative to H3PO4 computed at the same level of theory) is in good agreement with the experimentally observed 31P NMR chemical shift (δ=−88.73 ppm) (see Supporting Information for further details).

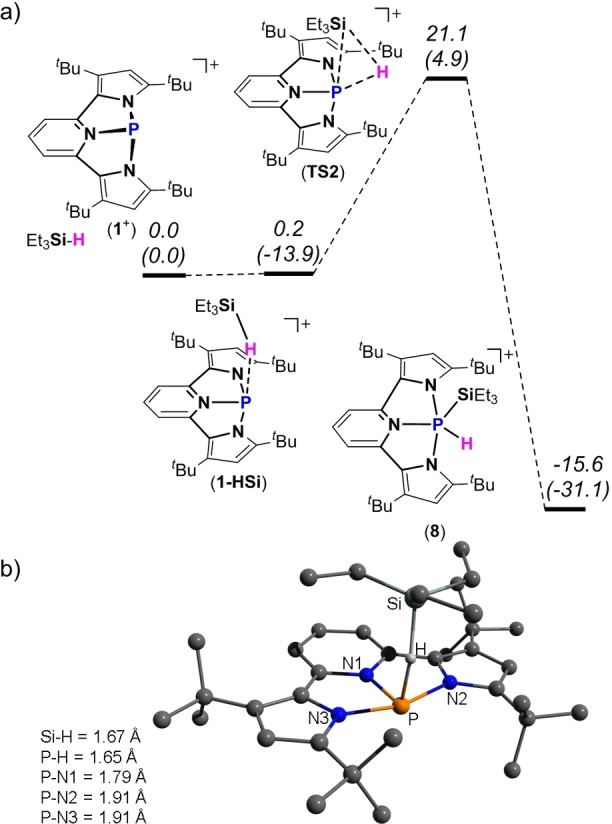

To get further insight into the activation of Et3Si−H bond by oxidative addition type reaction to the PIII center in 1+ leading to 8 as well as to understand the reason for the difference with the P‐center/ligand assisted pathway for activation of MeO−H and Et2N−H bonds, DFT calculation of the possible mechanism for Et3Si−H bond activation by 1+ was calculated at BP86‐D3/def2TZVP level of theory.[ 22 , 23 , 24 ] Thus, the first step of the Si−H bond activation is the formation of ‐HSiEt3 adduct (1‐HSi), which is exothermic and free Gibbs energy neutral (ΔH=−13.9 and ΔG=0.2 kcal mol−1) (Figure 6a). The analysis of the bond lengths around P‐center of the DFT optimized structure of 1‐HSi reveals elongation of the P−pyrrole bonds (P−N2 and P−N3 both of 1.91 Å) and a typical P−pyridine single bond of P−N1=1.79 Å (Figure 6b). These elongations of P‐pyrrole bonds in 1‐HSi are more pronounced but symmetrical i.e., both bonds are elongated to the same extent, in comparison to those calculated for the 1+ ‐O(H)Me adduct in which only one P‐pyrrole bond was significantly elongated (1.95 Å) (see Figure 3b). The calculated P−H bond length in 1‐HSi of 1.65 Å is longer compared to the P−H bond length in 1‐H (1.36 Å), and the Si−H bond length of (1.67 Å) in 1‐HSi is longer than calculated Si−H bond length in Et3SiH (1.50 Å). Thus, it can be concluded from this data that the Si−H bond in 1‐HSi is weakened, but not cleaved. The second step of the activation of Et3Si−H bond by 1+ is its cleavage and formation of the oxidative addition type product 8, which is strongly exothermic and exergonic with ΔH=−31.1 and ΔG=−15.6 kcal mol−1. This last step proceeds through a reasonably high transition state TS2 with Gibbs free energy barrier of ΔG ≠=21.1 kcal mol−1.

Figure 6.

a) DFT calculated PES for the activation of Et3SiH by 1+ . Free Gibbs energies (enthalpies) are given relative to the starting materials; b) DFT optimized structure of 1‐HSi and bond lengths around P atom.

Based on these calculations, we believe that the reason for activation of Si−H bond by 1+ via oxidative addition type pathway, rather than through P‐center/ligand assisted pathway is the result of the geometry of the 1‐HSi intermediate, in which the bulky Et3Si‐ group is located far from the pyrrole's basic nitrogen, and thus prefers to bind to a less sterically encumbered P‐center. In contrast, in case of MeOH and Et2NH activation, the larger MeO‐ and Et2N‐ groups bind to P‐center, while the pyrrole abstracts a proton that does not cause steric congestion.

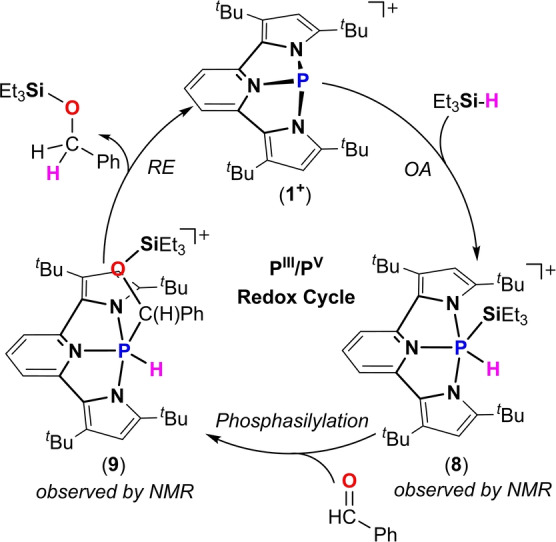

The ability of 1+ to activate the Et3Si−H bond in an oxidative addition type reaction to the P‐center prompted us to test it in a catalytic hydrosilylation reaction of C=O bonds and see how closely 1+ can mimic transition metal complexes in this catalysis. Thus, 5 mol % of [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] were added to a premixed solution of benzaldehyde and Et3SiH (1 : 1.2) in CDCl3. The reaction was monitored by 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopy. A full conversion of benzaldehyde to the corresponding silyl ether (Et3SiO−C(H2)Ph) occurs after 12 h of heating at 50 °C (Scheme 7) as was measured by 1H NMR (see Supporting Information). Right after the addition of [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] to the reaction mixture an oxidative addition product 8 was observed in 31P NMR (δ=−88.73 ppm) (see Figure S54). Then, during the course of the reaction the signal at δ=−88.73 ppm decreases, and a new signal appears at δ=−74.54 (1 J(PH)=648 Hz) ppm, complementary doublet in the 1H NMR was observed at δ=9.12 ppm (see Figures S55). We attributed these signals to the product of phosphasilylation 9 (Scheme 7). Notably, 9 was optimized by DFT computations using BP86‐D3/def2SVP level of theory[ 22 , 23 , 24 ] and its NMR was calculated using PBE1PBE/6‐31(d,p) level of theory.[ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ] As a result the computed 31P NMR chemical shift at δ=−73.32 ppm is in a good agreement with the observed signal of what is believed to be 9. Finally, a reductive elimination type reaction from PV center in 9 of Et3SiO−C(H2)Ph regenerates the active catalyst [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] (Scheme 7). It is important to note here that the catalysis did not work with the complex mixture obtained over time from the reaction of [1 +][B(C6F5)4] with Et3SiH (see Scheme 6). Meaning that 8 is indeed the key intermediate in this catalytic cycle, and no other species obtained in the reaction of [1 +][B(C6F5)4] with Et3SiH (Scheme 6) are responsible for the catalytic reaction. Although a preliminary possible mechanism based on the observed intermediates 8 and 9 was suggested (Scheme 7), to support it further a more thorough experimental and theoretical mechanistic investigation is required (for preliminary DFT calculations see Supporting Information).

Scheme 7.

Proposed catalytic cycle of hydrosilylation of benzaldehyde by [1+ ][B(C6F5)4].

Remarkably, the proposed catalytic cycle described in Scheme 7 with the intermediates observed therein indeed closely mimics the analogous catalysis with precious transition metal complexes.[ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ] Following the same key steps ‐ oxidative addition (OA) of the Si−H bond, silyl‐metallation (phosphasilylation in our case) of the C=O double bond, and finally reductive elimination (RE) to produce the desired silyl ether with concomitant regeneration of the starting metal catalyst.

Conclusion

To conclude, we have synthesized new geometrically constrained phosphenium cation in NNN pincer type ligand (1+ ). 1+ activates MeO−H, Et2N−H, and H3NBH3 by a P‐center/ligand assisted pathway. No PV species were observed in the activation of these bonds. Interestingly, 1+ reacts with an excess of H3NBH3 resulting in phosphinidene (PI) species 6. In the case of Et3Si−H bond activation by [1+ ][OTf] the reaction takes a different course and proceeds via H− abstraction leading to 1‐H and Et3SiOTf. However, the reaction of Et3SiH with [1+ ][B(C6F5)4] proceeds through an oxidative addition type reaction of the Si−H bond to the PIII center, in 1+ , producing new unstable PV complex 8. Finally, 1+ catalyzed hydrosilylation of benzaldehyde, while closely mimicking transition metal complexes in similar catalytic reaction following the same steps: oxidative addition, phosphasilylation and reductive elimination. The study of the chemistry of 1+ and other geometrically constrained P‐centers is still ongoing in our laboratory.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Israeli Science Foundation, Grant 237/18 and the Israel Ministry of Science Technology & Space, Grant 65692. D.B. thanks the Planning and Budgeting Committee (PBC), Israel for a fellowship. We thank Dr. A. Kaushansky for the help with NRT calculations.

S. Volodarsky, D. Bawari, R. Dobrovetsky, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202208401; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202208401.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Sigmund L. M., Maiera R., Greb L., Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 510–521; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Ruppert H., Sigmund L. M., Greb L., Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 11751; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Greb L., Ebner F., Ginzburg Y., Sigmund L. M., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 3030–3047; [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Ebner F., Greb L., Chem 2021, 7, 2151–2159; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1e. Ebner F., Wadepohl H., Greb L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18009–18012; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1f. Ben Saida A., Chardon A., Osi A., Tumanov N., Wouters J., Adjieufack A. I., Champagne B., Berionni G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16889–16893; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 17045–17049; [Google Scholar]

- 1g. Ruppert H., Greb L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202116615; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202116615; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1h. Volodarsky S., Malahov I., Bawari D., Diab M., Malik N., Tumanskii B., Dobrovetsky R., Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 5957–5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The organometallic chemistry of the transition metals (Ed.: Crabtree R. H.), Wiley, Hoboken, 2014, pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Abbenseth J., Goicoechea J. M., Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 9728–9740; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Kundu S., Chem. Asian J. 2020, 15, 3209–3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lipshultz J. M., Li G., Radosevich A. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 1699–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arduengo A. J., Stewart C. A., Davidson F., Dixon D. A., Becker J. Y., Culley S. A., Mizen M. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 627–647. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dunn N. L., Ha M., Radosevich A. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11330–11333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCarthy S. M., Lin Y.-C., Devarajan D., Chang J. W., Yennawar H. P., Rioux R. M., Ess D. H., Radosevich A. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4640–4650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robinson T. P., De Rosa D. M., Aldridge S., Goicoechea J. M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13758–13763; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 13962–13967. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robinson T. P., De Rosa D., Aldridge S., Goicoechea J. M., Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 15455–15465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cui J., Li Y., Ganguly R., Inthirarajah A., Hirao H., Kinjo R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16764–16767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cui J., Li Y., Ganguly R., Kinjo R., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 9976–9985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao W., McCarthy S. M., Yi Lai T., Yennawar H. P., Radosevich A. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17634–17644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin Y.-C., Hatzakis E., McCarthy S. M., Reichl K. D., Lai T.-Y., Yennawar H. P., Radosevich A. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6008–6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lim S., Radosevich A. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16188–16193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Volodarsky S., Dobrovetsky R., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 6931–6934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ojima I., Nihonyanagi M., Nagai Y., Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1972, 45, 3722. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ojima I., Kogure T., Kumagai M., Horiuchi S., Sato T., J. Organomet. Chem. 1976, 122, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ojima I. in The chemistry of organic silicon compounds (Eds.: Patai S., Rappoport Z.), Wiley, Chichester, 1989, pp. 1479–1526. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ojima I., Li Z., Zhu J. in The chemistry of organic silicon compounds (Eds.: Rappoport Z., Apeloig Y.), Wiley, Chichester, 1998, pp. 1687–1792. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deposition Numbers 2159230, 2159231, 2159232, 2159233, 2159234, 2159235 and 2159236 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

- 21. Robinson T. P., Lo S.-K., De Rosa D. M., Aldridge S., Goicoechea J. M., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15712–15724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Perdew J. P., Phys. Rev. B 1986, 34, 7406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Becke A. D., Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weigend F., Ahlrichs R., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.

- 25a. Glendening E. D., Weinhold F., J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 593–609; [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Glendening E. D., Badenhoop J. K., Weinhold F., J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 628–646. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flores J. A., Andino J. G., Tsvetkov N. P., Pink M., Wolfe R. J., Head A. R., Lichtenberger D. L., Massa J., Caulton K. G., Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 8121–8131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Komine N., Buell R. W., Chen C.-H., Hui A. K., Pink M., Caulton K. G., Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 1361–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boom D. H. A., Jupp A. R., Slootweg J. C., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 9133–9152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hawthorne M. F., Budde W. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 3147–3150. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Potter R. G., Camaioni D. M., Vasiliu M., Dixon D. A., Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 10512–10521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harder S., Spielmann J., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11945–11947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Veeraraghavan Ramachandran P., Kulkarni A. S., RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 26207–26210. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramachandran P. V., Drolet M. P., Kulkarni A. S., Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 11897–11900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.F. Dankert, J.-E. Siewert, P. Gupta, F. Weigend, C. Hering-Junghans, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202207064; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202207064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35. Belli R. G., Pantazis D. A., McDonald R., Rosenberg L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 2379–2384; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 2409–2414. [Google Scholar]

- 36.N. Đorđević, R. Ganguly, M. Petković, D. Vidović, Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 14671–14681. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37. Burck S., Gudat D., Nieger M., Du Mont W.-W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3946–3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Puntigam O., Förster D., Giffin N. A., Burck S., Bender J., Ehret F., Hendsbee A. D., Nieger M., Masuda J. D., Gudat D., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2041–2050. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hehre W. J., J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perdew J. P., Ernzerhof M., Burke K., J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 9982–9985. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Adamo C., Barone V., Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997, 274, 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Adamo C., Barone V., J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 108, 664–675. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Latypov S. K., Polyancev F. M., Yakhvarov D. G., Sinyashin O. G., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 6976–6987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.