Abstract

Brucella strains possess an operon encoding type IV secretion machinery very similar to that coded by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens virB operon. Here we describe cloning of the Brucella suis homologue of the chvE-gguA-gguB operon of A. tumefaciens and characterize the sugar binding protein ChvE (78% identity), which in A. tumefaciens is involved in virulence gene expression. B. suis chvE is upstream of the putative sugar transporter-encoding genes gguA and gguB, also present in A. tumefaciens, but not adjacent to that of a LysR-type transcription regulator. Although results of Southern hybridization experiments suggested that the gene is present in all Brucella strains, the ChvE protein was detected only in B. suis and Brucella canis with A. tumefaciens ChvE-specific antisera, suggesting that chvE genes are differently expressed in different Brucella species. Analysis of cell growth of B. suis and of its chvE or gguA mutants in different media revealed that ChvE exhibited a sugar specificity similar to that of its A. tumefaciens homologue and that both ChvE and GguA were necessary for utilization of these sugars. Murine or human macrophage infections with B. suis chvE and gguA mutants resulted in multiplication similar to that of the wild-type strain, suggesting that virB expression was unaffected. These data indicate that the ChvE and GguA homologous proteins of B. suis are essential for the utilization of certain sugars but are not necessary for survival and replication inside macrophages.

Bacteria of the genus Brucella are gram-negative facultative intracellular pathogens of various wild and domestic mammals and can cause severe zoonotic infections in humans. Traditionally, three major species are distinguished by their preference for certain animal hosts: Brucella abortus for cattle, B. melitensis for caprines, and B. suis for hogs. B. melitensis and B. suis account for the majority of clinical cases in humans (12, 38).

To evade host defenses, Brucella can inhibit neutrophil degranulation and block tumor necrosis factor alpha production by macrophages (8). Acidification of the phagosome is required for survival and multiplication of B. suis in macrophages (35). Secreted factors, which may be released when Brucella is either extracellular or in the acidic phagosome, could possibly play a role in macrophage survival. In this regard, the transposon mutagenesis study of O'Callaghan et al. (31) indicated that Brucella possesses an operon similar to the virB operon of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which encodes a type IV secretion machinery. The integrity of the virB operon is required for the intracellular multiplication of Brucella, as recently confirmed by signature-tagged mutagenesis both in vitro in a human macrophage infection model (18) and in vivo using mice (21).

The A. tumefaciens plasmid-encoded secretory apparatus presumably forms a multicomponent pore which spans both bacterial membranes and allows for transport of a single-stranded DNA-protein complex into a recipient plant or bacterial cell. Brucella exhibits the highest sequence similarity of mammalian pathogens to the secretory type IV machinery of A. tumefaciens (13). However, this does not necessarily infer that Brucella transfers DNA through its VirB-like complex, because type IV secretion machineries from Bordetella pertussis (11) and Helicobacter pylori (32) are known to translocate proteins. It is interesting to speculate that type IV secretion machineries present in other intracellular pathogens, such as Rickettsia prowazekii, Legionella pneumophila (13), and Bartonella henselae (42), may exert similar functions in intracellular survival.

The virulence regulon of A. tumefaciens is induced in response to chemical signals at the plant wound site by a two-component system composed of VirA, the sensor component, and VirG, the regulator which activates virulence gene transcription (7). Plant signals include low pH, phenolic compounds like acetosyringone, and monosaccharides (2; for a review, see references 4 and 5). Recent genetic data suggest that the receptor for phenolic compounds may be encoded by the A. tumefaciens chromosome rather than by its virulence Ti plasmid (6, 29). Monosaccharides such as galactose or arabinose bind to the periplasmic sugar binding protein ChvE. The gene encoding ChvE is part of an operon composed of chvE, gguA, and gguB, encoding transporter proteins, and gguC, encoding a protein of unknown function. Once a specific sugar binds to ChvE, the complex then interacts with the periplasmic domain of the transmembrane VirA protein and potentiates the response to phenolic molecules (34, 43). While acetosyringone induces maximal transcription of the virB operon at a 200 μM concentration, it only requires 1/100 of this concentration when sugars like galactose or arabinose are present in the medium. These plant sugars are able to enhance the level of chvE expression through the galactose binding protein regulator (GbpR), which is situated upstream of the chvE operon (15). Therefore, A. tumefaciens can sensitively and precisely trigger the production of virulence proteins encoded by its Ti plasmid by integrating, through its VirA sensor, several types of compounds present in plant wound exudate.

Although Brucella is a mammalian pathogen, it is phylogenetically closely related to A. tumefaciens. The presence of similar type IV secretion machineries involved in their virulence suggested that there might also be similarities in the activation by two-component sensor-regulator systems. Indeed, it is known that acidic conditions (35) as well as expression of a complete B. suis virB operon are required in macrophages (31; M. L. Boschiroli, S. Ouahrani-Bettache, S. Michaux-Charachon, V. Foulongne, A. Allardet-Servent, C. Cazevieille, G. Bourg, J.-P. Liautard, M. Ramuz, and D. O'Callaghan, unpublished data) and in epithelial cells (10). Recently, we microsequenced the N termini of the proteins contained in an acidic B. suis supernatant and identified a protein similar to A. tumefaciens ChvE (R.-A. Boigegrain, J. Machold, C. Weise, and B. Rouot, unpublished data).

These findings prompted us to analyze ChvE function in B. suis 1330 with regards to its sugar binding capacity and its possible involvement in bacterial intracellular survival. For this report, we kept (because of the high similarities of B. suis genes to those of A. tumefaciens) the same nomenclature, i.e., chvE, gguA, and gguB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Characteristics of bacterial strains and plasmids used are described in Table 1. Escherichia coli strains were routinely grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium, whereas B. suis strains were grown in tryptic soy (TS) medium and the strains of A. tumefaciens were grown at 21°C in YEB medium (41). Minimal medium A (3) was supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM carbon source, 0.1% yeast extract, 2 μg of vitamin B6/ml, 2 μg of vitamin B1/ml, and 0.5 ng of biotin/ml for Brucella strains and with 1 mM MgSO4 and 10 mM carbon source for Agrobacterium strains. Solid AB minimal medium (1.5% agar) supplemented with or without acetosyringone was used for virB induction experiments (41). Antibiotics were added to the media in the following concentrations: ampicillin, 50 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 50 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 25 μg ml−1; and gentamicin, 15 μg ml−1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype and/or description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5αF′ | F′ endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA relA1 φ80d lacZΔM15 (lacZYA-argF)U169 | Life Technologies |

| B. suis | ||

| 1330 | Biotype 1; ATCC 23444 | ATCC |

| 1330 ΔchvEbs | B. suis 1330 ΔchvEbs::kan (chvEbs null mutant) | This work |

| 1330 ΔgguAbs | B. suis 1330 ΔgguAbs::kan (gguAbs null mutant) | This work |

| 1330 ΔnikA | B. suis 1330 Δnika::kan | 23 |

| B. melitensis 16 M | Biotype 1; ATCC 23456 | ATCC |

| B. abortus | ||

| A1 | Biotype 1; ATCC 23448 | ATCC |

| A3 | Biotype 3; ATCC 23450 | ATCC |

| B. canis | ATCC 23365 | ATCC |

| B. ovis | ATCC 25840 | ATCC |

| A. tumefaciens | ||

| C58 | Wild-type, pTiC58 (nopaline) | 22 |

| A348 | Chromosomal C58, pTiA6 NC (octopine) | 41 |

| MX1 | C58; chvE::Tn5 mutant with pSM243cd | 22 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | ColE1 replicon, lacZ (Ampr) | AP Biotech |

| pUC4K | Contains a Kanr cassette flanked by polylinker | AP Biotech |

| pCVD442 | Vector with sacB encoding sucrose sensitivity (Ampr) | 14 |

| pBBRIMCS | Broad-host-range cloning vector (Cmr) | 27 |

| pUC18::chvEbs | pUC18 containing a 2.7-kb HindIII fragment of B. suis encoding the complete chvEbs gene and part of gguAbs (Ampr) | This work |

| pUC18::gguAbs | pUC18 containing a 4.5-kb HincII fragment of B. suis encoding part of chvEbs and the complete gguAbs, gguB, and orf4 genes (Ampr) | This work |

| pUC18 ΔchvEbs::kan | pUC18 derivative with chvEbs null allele in NruI site | This work |

| pUC18 ΔgguAbs::kan | pUC18 derivative with gguAbs null allele in EcoRV site | This work |

| pCVD ΔchvEbs::kan | pCVD442 with chvEbs null allele in NdeI-EcoRV | This work |

| pCVD ΔgguAbs::kan | pCVD442 with gguAbs null allele in NcoI-HindIII | This work |

| pBBR1::chvEbs | pBBR1MCS derivative with the chvEbs gene in HindIII-NcoI | This work |

| pBBR1::chvEbs2 | pBBR1MCS derivative with the chvEbs gene in HindIII-EcoRV | This work |

| pBBR1::gguAbs | pBBR1MCS derivative with the gguAbs, gguB, and orf4 genes in PstI-SacI | This work |

| pBBR1::chvEbsoperon | pBBR1MCS derivative with the chvEbsoperon and orf4 genes in HindIII-SacI | This work |

| pBBR1::gbpR-chvE | pBBR1MCS derivative with the gbpR-chvE gene from A. tumefaciens in EcoRI | This work |

| pSM243cd | virB::Tn3-HoHo1 (virB::lacZ fusion, Cbr) | 44 |

| pTC110 | IncW, derivative of pUCD2 (Kanr; Gmr) | 9 |

| pTC110::chvEbs | pTC110 derivative with the chvEbs gene in HindIII | This work |

| pTC116 | pTC110 derivative with the gbpR-chvE gene in EcoRI | 9 |

DNA isolation, Southern blots, and DNA sequencing.

DNA treatments with restriction and modification enzymes, cloning techniques, Southern blotting, and hybridizations were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions or standard protocols (37). Extraction of genomic DNA from E. coli and B. suis strains was performed as described previously (3). For colony blots and Southern hybridizations, DNA fragments were transferred to a Biodyne B nylon membrane (Pall, Port Washington, N.Y). Probe DNA was labeled using a random prime kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) with digoxigenin for nonradioactive labeling or with [32P]dCTP (NEN; 6,000 Ci mmol−1) for radioactive labeling. DNA sequencing with pUC18-based templates was done by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (39), using universal, reverse, and specific internal primers synthesized by Genome Express (Grenoble, France). Each base was sequenced at least twice.

Cloning of the Brucella homologue of the A. tumefaciens ChvE operon. (i) chvE.

A 1,052-bp DNA fragment was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides derived from the chvE gene sequence of A. tumefaciens C58 (5′-GTCCATTATTTCGCTGATGG-3′ and 5′-CAGCTGGTCTTCCTTGTAG-3′). The PCR product was labeled with digoxigenin and hybridized to genomic DNA of B. suis digested with various restriction enzymes followed by Southern blotting. Under low-stringency conditions, the probe bound to a 2.7-kb HindIII fragment, which was purified and subcloned into pUC18, yielding clone pUC18::chvEbs.

(ii) gguA.

A 279-bp DNA fragment (EcoRV-EcoRV) from the chvE gene of B. suis was labeled with digoxigenin and hybridized to genomic DNA of B. suis digested with various restriction enzymes, followed by Southern blotting. Under high-stringency conditions, the probe bound to a 4.5-kb HincII fragment, which was purified and subcloned into pUC18, yielding clone pUC18::gguAbs.

The gene chvE was recloned into the broad-host-range vector pBBR1MCS (27) by excision from pUC18::chvEbs as a 1.8-kb HindIII/NcoI fragment and insertion into the SmaI polylinker restriction site of pBBR1MCS, resulting in construct pBBR1::chvEbs, or by excision from pUC18::chvEbs as a 2.1-kb HindIII/EcoRV fragment and insertion into the corresponding site of pBBR1MCS, resulting in construct pBBR1::chvEbs2.

The genes gguA and gguB were recloned into the broad-host-range vector pBBR1MCS (27) by excision from pUC18::gguAbs as a 4.2-kb PstI/SacI fragment and insertion into the corresponding polylinker restriction sites of pBBR1MCS, resulting in construct pBBR1::gguAbs. The whole B. suis operon chvE-gguA-gguB was recloned by excision from pBBR1::chvEbs2 of a 2.28-kb NcoI fragment (one NcoI site is in pBBR1MCS) and insertion into the corresponding sites of pBBR1::gguAbs, resulting in construct pBBR1::chvEbsoperon.

Inactivation of B. suis chvE and gguA by homologous recombination.

From pUC18::chvEbs an internal fragment of 840 bp flanked by two NruI sites was deleted and replaced by the 1.2-kb blunted kanamycin resistance gene from plasmid pUC4k (Pharmacia Biotech). The plasmid pUC18ΔchvEbs::kan, in which transcription of the kanamycin cassette was oriented in the opposite direction of chvE, was selected. The chvE-kan insert was excised as a 2.7-kb NdeI/EcoRV fragment and recloned into pCVD442 (14) containing the gene sacB determining sucrose sensitivity (19, 20). B. suis was transformed with this suicide vector, named pCVDΔchvEbs::kan, by electroporation as described previously (26). Inactivation of the gguA gene was carried out in a similar manner by replacing the EcoRV fragment with the kanamycin resistance gene in the same transcriptional orientation as gguA and gguB, leading to pUC18ΔgguAbs::kan and pCVΔgguAbs::kan. Inactivation of the genes was verified by Southern blot analysis for chvE and gguA and for the former by immunoblotting with A. tumefaciens ChvE-specific antiserum.

Western blot analysis.

For preparation of cell lysates equal numbers of bacteria (4 × 108) were harvested from cultures, washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer, and heated to 100°C for 15 min. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described by Laemmli (28), using a 12 or 15% (wt/vol) separating gel. The proteins were transferred onto Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore) using a semidry transfer procedure and stained with Coomassie blue. Immunodetection in total cell lysates was performed with polyclonal antisera raised against ChvE and VirB8 from A. tumefaciens diluted 3,000- and 10,000-fold, respectively (41, 43). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) were used in combination with the ECL system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France) to develop the blot for chemiluminescence before visualization on films (Kodak X-AR) or quantification (Image station 440 CF; Kodak).

Bacterial growth experiments.

Brucella strains were grown in TS at 37°C in the presence of antibiotics to stationary phase and diluted, without antibiotics, in TS or minimal medium supplemented with a single carbon source to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.04 to 0.06. Cultures were incubated with shaking at 37°C. At intervals, the OD600 was measured in a spectrophotometer.

Complementation studies with an A. tumefaciens chvE mutant and vir gene induction assays.

The gene chvE was recloned into the broad-host-range vector pTC110 (9) by excision from pUC18::chvEbs as a 1.8-kb HindIII/NcoI fragment and insertion into the polylinker EcoRI restriction site of pTC110, resulting in construct pTCchvEbs. A. tumefaciens MX1 (ΔchvE) was transformed by electroporation. Induction of virB::lacZ reporter gene expression was followed after growth on solid induction medium as described previously (41, 44).

Infection and intracellular survival assay of B. suis strains in murine J774A.1 macrophage-like cells and human monocytes.

Experiments were essentially done as described earlier (8, 16). Briefly, murine J774.1 macrophage-like cells were seeded in 24-well plates (Falcon; Becton Dickinson, Meylan, France) and resuspended at 2 × 105 cells/well in 1 ml of the same medium. Alternatively, monocytes were seeded into Falcon Primaria 24-well tissue culture plates at a density of 5 × 105 monocytes/well in 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Life Technologies) and allowed to adhere for 16 h. Both types of adherent cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 prior to infection at a multiplicity of infection of 20 with stationary-phase B. suis grown in the presence of the corresponding antibiotics. After washings with PBS, 0.5 ml of bacteria in the appropriate incubation medium were added to each well. After 30 min, the wells were rinsed thoroughly with PBS and filled with 1 ml of RPMI 1640–10% fetal calf serum with gentamicin (30 μg ml−1) for least 1 h. At 1.5, 7, 24, and 48 h postinfection, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in 0.2% Triton X-100. The number of surviving bacteria in duplicate wells was determined after plating serial dilutions on TS agar, incubation for 3 days at 37°C, and counting of CFU.

Computer-based sequence analysis.

The DNA sequence obtained was translated into the six reading frames and compared to the polypeptides in the Swissprot database (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Geneva, Switzerland) by using the programs FASTA (33) and BLAST (1) to identify similar sequences. Multiple sequence alignment of ChvE amino acid sequences was carried out with GeneBee (30) or Clustal W, 1.60 (45). The free energy was calculated with DNA mfold (SantaLucia et al., unpublished data; 40). Sequence data from B. suis were from The Institute for Genomic Research (http://www.tigr.org), and preliminary sequence data from B. melitensis was obtained from The Institute of Molecular Biology and Medicine, The University of Scranton, Scranton, Pa.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The EMBL accession number of the sequence reported in this paper is AJ305234.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the chvE gene of B. suis.

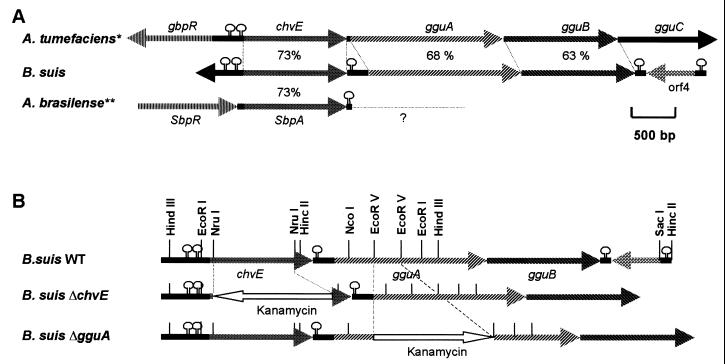

To clone the B. suis chvE gene, a PCR probe was prepared from genomic A. tumefaciens C58 DNA using A. tumefaciens chvE primers. Hybridization at low stringency to B. suis DNA digested with HindIII revealed a single hybridizing band of about 2.75 kb which was cloned into pUC18. DNA sequencing analysis revealed the presence of two open reading frames (ORFs) in the same orientation. The first complete ORF (chvE) displayed nucleotide sequence identity of 73 and 72% with A. tumefaciens strains C58 and D10B/87 chvE genes, respectively (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Physical and genetic map of the B. suis region similar to the A. tumefaciens chvE operon. (A) B. suis DNA sequence with genes similar to A. tumefaciens chvE, gguA, and gguB and to A. brasilense sbpA. Percentage values indicate DNA sequence identity. The differences in the B. suis operon include (i) the absence of genes encoding the regulator GbpR and GguC and (ii) an additional intergenic palindromic sequence preceded by the putative RNase E cleavage site. ∗, gene organization from reference 24; ∗∗, gene organization from reference 46. (B) Mapping of the main restriction sites of the B. suis chvE operon and schematic representation of the deletion or insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene into the chvE and gguA genes. The loops along the lines representing gene organization symbolize the presence of palindromic sequences which might adopt hairpin loop structures. WT, wild type.

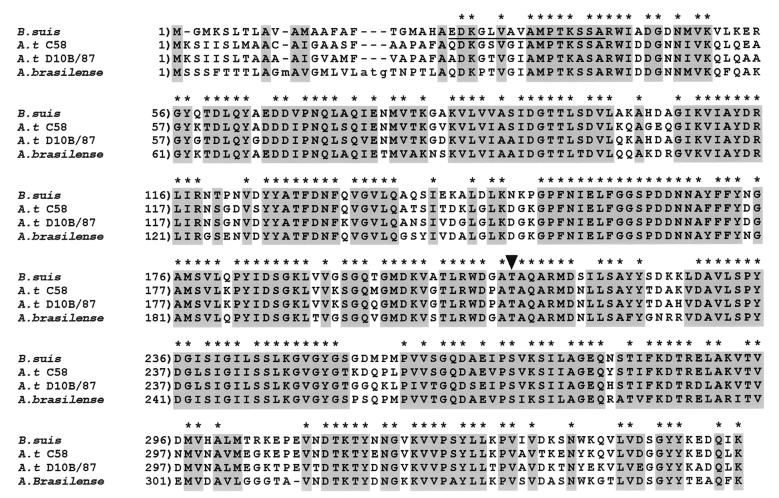

Comparison of the N-terminal amino acid sequence deduced from chvE with that obtained from purified Brucella ChvE protein by microsequencing (underlined letters in Fig. 2, line 1) clearly demonstrated that the ChvE protein is encoded by the cloned gene and that the translation product likely carries a signal sequence of 23 amino acids. Comparison of the amino acid sequences deduced from chvE with the corresponding proteins from A. tumefaciens and Azospirillum brasilense (SbpA) indicated the presence of highly conserved regions, and 216 of 331 amino acids were identical in all the proteins (Fig. 2). Threonine at position 211 of A. tumefaciens ChvE, which is necessary for sugar-potentiated virB expression through interaction with VirA (43), was also present in B. suis ChvE and SbpA.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of amino acid sequences deduced from nucleotide sequences. Sequence alignment between ChvE proteins from B. suis, A. tumefaciens, and A. brasilense reveals a high degree of identity within many regions. The underlined N-terminal amino acids from B. suis ChvE resulted from the microsequencing of the purified protein. The inverted solid triangle points to threonine 211, an amino acid crucial for A. tumefaciens ChvE-VirA interaction, which is conserved in all sequences. Shaded blocks include amino acid identities (∗) and conservative substitutions (no asterisk) (S-T-A, L-V-I-M, K-R, D-E, Q-N, F-Y-W). A. t, A. tumefaciens.

Cloning and sequence analysis of the region adjacent to chvE.

In A. tumefaciens, upstream to but divergent in transcription from chvE is the ORF coding for GbpR (galactose binding protein regulator), which belongs to the LysR family of transcriptional regulators (15) and controls chvE operon expression (see Fig. 1A). Like A. tumefaciens, the B. suis chvE upstream region contains two palindromic sequences [ΔG(25°C) = −17.0 and −10.2 kcal], but in contrast to the plant pathogen, no gbpR-like gene was found in the 0.5-kb upstream region of chvE. Compared to the corresponding A. tumefaciens chvE region, the intergenic sequence downstream of chvE is 55 nucleotides longer and may form a hairpin of higher stability than that described for A. brasilense sbpA [ΔG(25°C) = −18.8 and −13.9 kcal, respectively]. The intergenic stem-loop is preceded by GATTTT, a putative cleavage site for the enzyme RNase E, which in E. coli controls mRNA stability (36). The lack of a string of T residues downstream of the palindromic sequence indicated that this intergenic stem-loop did not function as a Rho-independent terminator. Hence, chvE and downstream genes might be part of an operon.

To further characterize the genes downstream of chvE, a HincII DNA fragment which hybridized with the chvE-gguA previously obtained was cloned and sequenced. In B. suis, gguA and gguB genes (Fig. 1A) encoding proteins similar to the ATP-binding protein GguA (69% amino acid sequence similarity) and to the permease GguB (66%) of A. tumefaciens were found. Instead of gguC in A. tumefaciens, another ORF divergent in transcription was present in B. suis, but no significant homology to known genes could be found.

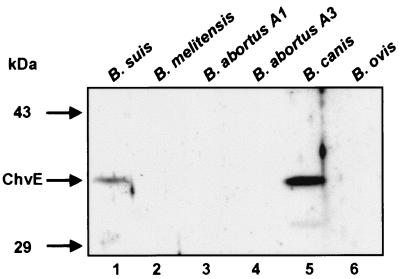

Occurrence in various Brucella spp. of chvE and production of ChvE.

Southern hybridization using the HindIII-NcoI chvE fragment from plasmid pUC18::chvEbs or the EcoRV-HindIII fragment of pUC18::gguAbs as probe was performed on HindIII-digested genomic DNA from B. melitensis, B. abortus A1 and A3, B. canis, and B. ovis. For all species, a fragment of about 2.75 kb hybridized with both B. suis probes, except B. melitensis, for which the fragment was about 3.0 kb long (data not shown). To investigate whether the various Brucella strains produced ChvE, we took advantage of the interspecies conservation of proteins from A. tumefaciens and Brucella and used a polyclonal antiserum raised against A. tumefaciens C58 ChvE (43). Immunoblotting with this serum revealed the presence of the ChvE protein in B. suis and B. canis, with the latter being more intensely labeled (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 5). However, in the other species no ChvE-like immunoreactivity could be detected when brucellae were grown for 24 h in TS (Fig. 3, lanes 2 to 4 and 6) or in minimal medium containing 10 mM galactose at pH 7.0 or 4.5 (data not shown). Together, these observations revealed that the Brucella chvE gene is not equally expressed in various species, suggesting that in certain strains ChvE is either regulated differently than in B. suis or produced at a very low level if at all.

FIG. 3.

Presence of ChvE in various Brucella spp. Brucella strains were grown for 16 h in TS and equal amounts of proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using an A. tumefaciens ChvE-specific antiserum. ChvE cross-reactive proteins could only be detected in B. suis and B. canis even when bacteria were grown in minimal medium supplemented with galactose at pH 7.0 or 4.5.

Phenotypic characterization of chvE and gguA Brucella mutants.

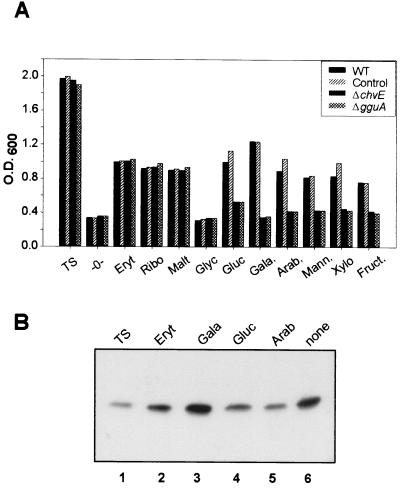

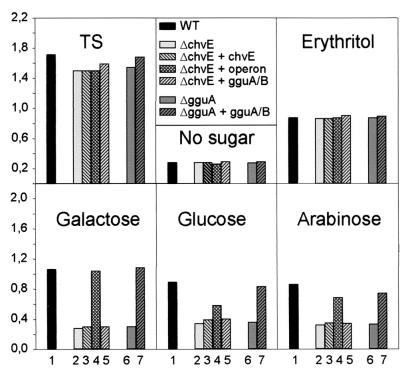

To identify functions of the B. suis proteins encoded by chvE and gguA, we constructed insertion mutants (Fig. 1B) by replacement of an internal gene fragment of chvE or gguA by the kanamycin resistance gene as previously described (23). In the knockout mutants used in this study, the kanamycin resistance gene had the same transcriptional orientation in the case of gguA and the opposite orientation in the case of chvE. As a control strain likely not affected in sugar metabolism, a nikA insertion mutant (defect in nickel uptake) generated as described above was included (23). In TS, the growth of the chvE mutant as well as the gguA mutant was slightly delayed compared to the wild-type and the nikA mutant (data not shown) but reached almost the same OD value (2.0) after 24 h (Fig. 4). After 24 h in minimal medium at pH 7.0 without an additional source of carbon, the B. suis wild type and its mutants reached a final OD value of only 0.2 to 0.4 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Effect of different sugars on B. suis and chvE or gguA mutant growth and ChvE production. (A) B. suis wild type, the nikA control mutant, and the chvE or gguA mutant were grown for 24 h in TS or in minimal medium at pH 7.0 containing no sugar (-0-) or 10 mM meso-erythritol, d-(+)-ribose, d-(+)-maltose, glycerol, d-(+)-glucose, d-(+)-galactose, l-(+)-arabinose, d-(+)-mannose, d-(+)-xylose, or d-(+)-fructose. (B) The level of ChvE immunoreactive protein was assessed by loading about 4 × 108 bacteria of the B. suis wild type onto an SDS-PAGE gel after 24 h of growth in TS (lane 1) or in minimal medium at pH 7.0 in the presence of erythritol (lane 2), galactose (lane 3), glucose (lane 4), or arabinose (lane 5) or without sugar (lane 6). Data shown are from one representative experiment out of the three performed. WT, wild type.

To determine the sugar specificity of ChvE and/or its associated transporter proteins, the chvE and gguA mutants were grown in minimal medium supplemented with 10 mM concentrations of various sugars as the sole source of carbon. Identical growth of the B. suis wild type, the control strain, and both mutants in liquid media containing meso-erythritol, d-(+)-ribose, and d-(+)-maltose was observed (Fig. 4A). When compared to the wild-type strain and the control nikA mutant, growth of the chvE and gguA mutants with either d-(+)-galactose, d-(+)-xylose, l-(+)-arabinose, d-(+)-glucose, or d-(+)-mannose was dramatically reduced (Fig. 4A). It thus appears that the sugar specificity of B. suis ChvE and GguA for growth is very similar to that observed for chemotaxis mediated by SbpA in A. brasilense (46) and for potentiation of virB expression mediated by ChvE in A. tumefaciens (2, 7). Furthermore, in the presence of galactose, the growth of the mutants did not exceed that obtained with the parental strain in minimal medium without sugar or with glycerol, a source of carbon not involved in bacterial growth. This suggested that galactose utilization in B. suis is strictly dependent on the chvE DNA region.

The behavior of the gguA mutant in the presence of the various sugars which perfectly matched that of the chvE knockout mutant suggested two possibilities. First, both chvE and gguA may be evenly required for the utilization of sugars binding to ChvE. The second possibility is that only gguA is important and that the absence of the GguA transporter protein would block utilization of galactose, mannose, and arabinose. In this hypothesis, the absence of growth of the chvE mutant can be explained if the chvE inactivation altered the expression of the gguA and -B genes because they belong to the same operon.

In order to determine if sugars alone exert an effect on the B. suis ChvE production as does A. tumefaciens through the GbpR, the level of ChvE immunoreactive proteins was evaluated in the B. suis wild type grown under various conditions (Fig. 4B). In contrast to the results reported for A. tumefaciens ChvE (15) or A. brasilense SbpA (46), the B. suis ChvE protein could be induced in minimal medium even in the absence of sugar (Fig. 4B, lane 6). Indeed, the level of ChvE immunoreactive protein remained high in minimal medium in the presence of galactose (lane 3), but other sugars linked to ChvE (arabinose, glucose) resulted in lower levels of ChvE similar to that obtained with erythritol (Fig. 4B, lane 2). ChvE production in B. suis thus appeared to be regulated differently from that of A. tumefaciens, where arabinose elevates the ChvE level over that with galactose (15), or that of SbpA of A. brasilense elevated by arabinose, fucose, or galactose (46).

Complementation of B. suis chvE deletion mutants.

Complementation experiments were carried out to determine whether B. suis genes encoding the sugar binding protein ChvE and transporters are all required for sugar utilization and are part of the same operon. The chvE mutant was complemented in trans with either the intact chvE (pBBR1::chvEbs), the whole set of B. suis chvE-gguA-gguB genes, or only the gguA-gguB transport genes (Fig. 5). The ΔchvE strains complemented with the B. suis chvE gene (column 3) or the gguA-gguB genes (column 5) did not grow better than the mutant itself (column 2) in the presence of glucose, galactose, or arabinose (Fig. 5, lower panels). On the contrary, when the chvE mutant strain was complemented with the whole B. suis chvE region (column 4), growth of the resulting strain was partially (arabinose, glucose) or fully (galactose) restored in sugar-containing medium. These results, which confirmed that the chvE knockout also impaired GguA and GguB production, indicated that chvE, gguA, and gguB are part of the same operon. They also suggested that the lack of GguA production probably occurred through a polar effect due to the insertion of the kanamycin cassette in chvE. These observations agree with the data shown in Fig. 4 indicating that the GguA protein is essential for growth of B. suis in the presence of certain sugars. Accordingly, the ΔgguA strain (Fig. 5, column 6), which grew similarly to the chvE mutant, was fully complemented for sugar utilization by pBBR1::gguAbs (column 7). The fact that this pBBR1::gguAbs construct could not alone complement the ΔchvE strain for growth in these conditions reciprocally implied that the ChvE protein itself was critical for galactose utilization. Altogether these results suggested that both the multiple sugar binding protein ChvE and the gguA and -B genes are required for sugar utilization in B. suis.

FIG. 5.

Effect of cross-complementation of B. suis chvE or gguA mutants on bacterial growth. Comparison of bacterial growth was carried out on B. suis wild type (column 1) and on the chvE mutant itself (column 2) or complemented with chvE alone (pBBR1::chvEbs; column 3), the three genes (chvE, gguA, and gguB) of the chvE operon (pBBR1::chvEbsoperon; column 4), or the transporter genes gguA and gguB (pBBR1::gguAbs; column 5). Growth comparison also included the gguA mutant (column 6) and its complemented form with pBBR1::gguAbs (column 7). The growth of the various strains was assessed after 24 h in TS or in minimal medium alone (pH 7.0) or containing 10 mM erythritol, glucose, galactose, or arabinose. WT, wild type.

Complementation of A. tumefaciens chvE deletion mutants.

Further, we investigated if the B. suis ChvE protein had the capability to interact with VirA to induce virB transcription in A. tumefaciens. For this purpose, several constructs were introduced into the A. tumefaciens chvE deletion mutant MX1, which contained in pSM243cd the reporter gene lacZ fused to the virB promoter (7). After incubation on solid AB minimal medium in the presence or absence of acetosyringone, β-galactosidase activities were compared in strain MX1 carrying empty cloning vector pTC110, pTC110::chvEbs, pTC116, pBBR1MCS, or pBBR1chvEbsoperon. Table 2 shows that virB expression in strain MX1 is strongly stimulated by the production of A. tumefaciens ChvE (pTC116). Under the same conditions, production of B. suis ChvE through expression of chvE or the chvE operon slightly enhanced virB expression over that obtained with the pTC110-carrying control strain. Thus, ChvE from B. suis carries a weak ability for virulence gene induction in A. tumefaciens.

TABLE 2.

Induction of virB::lacZ expression in A. tumefaciens MX1 complemented strainsa

| Plasmid used to transform MX1 strain (ΔchvE) | Protein produced | β-Galactosidase expression (Miller units)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Without acetosyringone | With acetosyringone | ||

| None | None | 0 | 22 |

| pTC110 | None | 12 | 58 |

| pTC116 | ChvE | 0 | 2,400 |

| pTC110::chvEbs | B. suis ChvE | 0 | 225 |

| pBBR1MCS | None | 0 | 160 |

| pBBR1::chvEbsoperon | B. suis ChvE, GguA, and GguB | 0 | 311 |

The A. tumefaciens MX1 chvE mutant strain was transformed with plasmids expressing A. tumefaciens chvE, B. suis chvE, or the whole B. suis chvE operon. The resulting strains were grown for 48 h on solid induction medium in the presence of glucose (0.2%) with or without 200 μM acetosyringone. The induction of virB::lacZ reporter gene was determined as described previously (41, 43) in two experiments carried out in duplicate.

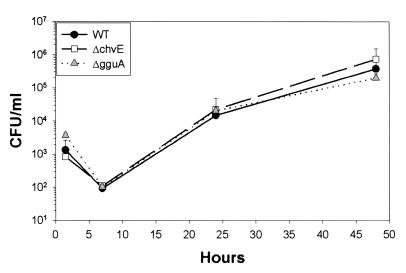

Effect of chvE operon impairment on the survival and multiplication of B. suis in macrophages.

Brucella ChvE may affect virB induction and thereby bacterial virulence, similar to its homologue in the closely related A. tumefaciens. In parallel, a study reported that gguA expression is enhanced during B. suis macrophage infection (25). To assess whether or not the ChvE and GguA proteins have a role in virulence, we infected macrophages with B. suis wild type and its chvE and gguA mutants. Typically, a biphasic curve is observed with B. suis 1330, i.e., an initial decrease in CFU (killing) during the first 7 to 10 h followed by a multiplication phase thereafter. Figure 6 shows that the same biphasic curve of J774 macrophage infection was observed after infection with the wild-type Brucella and both mutants, suggesting that the proteins encoded by the chvE operon do not play any role in the course of in vitro infection. Human monocyte infection (not shown) with the same three B. suis strains led to a similar conclusion, thus supporting the idea that proteins encoded by the chvE operon are not necessary for intracellular maintenance and replication in these in vitro infection models.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of the intracellular growth of B. suis wild type and its mutants during macrophage infection. Mouse J774 cells were infected for 30 min with B. suis wild type or the chvE or gguA mutant at a multiplicity of infection of 20. Cells were then washed and incubated for 1, 7, 24, and 48 h before lysis and analysis of intracellular survival and multiplication. Data shown are expressed as mean values ± standard errors of three experiments performed in duplicate. WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

We cloned the B. suis chvE operon and characterized the ChvE protein homologous to A. tumefaciens ChvE. The deduced amino acid sequence of ChvE reveals throughout the protein a high degree of similarity to ChvE from various strains of A. tumefaciens (73 to 72% identity) and to SbpA of A. brasilense (73%). Further, we found that the B. suis chvE operon-encoded proteins exhibit roughly the same sugar specificity as the corresponding A. tumefaciens and A. brasilense proteins. Thus, the integrity of the B. suis chvE operon is required for growth in the presence of d-(+)-galactose, l-(+)-arabinose, d-(+)-glucose, d-(+)-mannose, d-(+)-xylose, and d-(+)-fructose but not for growth in meso-erythritol, d-(+)-ribose, or d-(+)-maltose. However, some differences were noted between the various species. For example, xylose is not a chemoattractant for A. brasilense and the weak chemotactic effect of d-(+)-fructose is SbpA independent (46). Concerning the transport system encoded by the chvE operon, it was shown that impairment of that of A. tumefaciens did not affect growth in the presence of sugars such as l-(+)-arabinose, d-(+)-galactose, or d-(+)-glucose (24). To explain this effect, Kemner et al. (24) suggested that in A. tumefaciens either the transport system encoded by gguA and gguB is not required for transport of these sugars or that it can take up sugars via alternative systems. This differs from our observations in B. suis, since growth in minimal medium containing certain sugars as the carbon source was completely abolished in the gguA mutant. The requirement of the GguA protein was confirmed by the impossibility of restoring the growth of the B. suis chvE mutant complemented with the chvE gene alone, while complementation with the whole operon (i.e., chvE, gguA, and gguB) permitted growth in galactose comparable to that of the parental strain. Together the results of our complementation studies indicate that B. suis growth in the presence of galactose and arabinose requires the simultaneous production of chvE operon proteins, suggesting that no other sugar binding protein or transporters could substitute for the utilization of these sugars.

Expression of ChvE or SbpA is not detectable in A. tumefaciens or A. brasilense in the absence of sugar but is induced by arabinose, galactose, and fucose (15, 46). The regulation occurs through the transcriptional regulator GbpR for A. tumefaciens and by an unknown protein in A. brasilense. In contrast, in B. suis the expression of chvE is constitutive under the tested conditions, since ChvE was immunologically detectable in TS as well as in minimal medium without a carbon source. This finding implies that the regulation of B. suis ChvE does not strictly depend on the presence of certain sugars like galactose and suggests that chvE expression is not under control of the GbpR-like protein as in A. tumefaciens. An interesting finding was that only B. suis and B. canis produced substantial levels of ChvE, despite the fact that a similar gene sequence is present in all the species tested. Because of the high sequence similarity between the ChvE proteins of B. suis and A. tumefaciens and the polyclonal nature of the anti-ChvE antiserum used for immunological detection, it is unlikely that similar amounts of ChvE were produced in other Brucella spp. Two possible explanations for this observation are that ChvE production in other Brucella spp. is differently regulated or impossible due to DNA mutations (see Addendum). In this latter case, B. melitensis, B. abortus, and B. ovis might possess another transport system for sugars that normally bind to ChvE in B. suis. In agreement with this hypothesis, a glucose and galactose transporter-coding gene was cloned from B. abortus 2308 and the gene product shares sequence similarity with the E. coli fucose transporter (17).

Expression of the virB-like genes was reported to be important for the multiplication of B. suis inside macrophages. This does not apply to chvE since in vitro infections with either B. suis wild type or the chvE mutant exhibit similar survival and multiplication profiles. This supports the idea that virB expression does not require ChvE in B. suis in our murine J774 macrophages or human monocytes. Note, however, that in A. tumefaciens ChvE is not the sole activator of virB expression but is mainly an enhancer of plant phenolic signals. As such, it is not required for maximal activation if the concentration of the phenolic compound is sufficient. Our observations could indicate that in macrophages the signal for B. suis virB expression is sufficient for the bacteria to survive even in the absence of ChvE. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that in an in vitro situation or in other cells (epithelial cells), B. suis ChvE could potentiate the expression of type IV secretion system genes and thus participate in bacterial virulence.

Another point which can be deduced from this study concerns the putative role of GguA in the macrophage. It has been reported that during macrophage infection the expression of GguA increases, suggesting that this protein might be involved in virulence (25). From our work, it can be deduced that the GguA protein is likely not synthesized in the both the gguA and chvE deletion mutants. The fact that these mutants and the parental strain similarly multiplied in macrophages infers that not only ChvE but also GguA is not involved in the survival of B. suis in macrophages. Thus, the increased expression of GguA during macrophage infection may only indicate that the chvE operon is upregulated because of acidification or stress conditions in the phagosome, as was recently described for the nikA gene (23).

In summary, this work reveals that the proteins encoded by the chvE operon in B. suis are essential for the utilization of a wide variety of sugars but are not needed for bacterial survival and multiplication in macrophages during in vitro infection. However, to rule out any role of B. suis ChvE in the expression of the virB operon or in bacterial virulence, further infections carried out on the whole animal will be required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. W. Nester and Lishan Chen for the various A. tumefaciens strains and plasmids, Y. Machida for the anti-ChvE antibody, and A. Böck for support and discussions. We also thank S. Köhler for the chvE primers, V. Jubier-Maurin for providing the B. suis nikA mutant, D. O'Callaghan for helpful discussions, and J. Armand for technical assistance. We also thank The Institute of Molecular Biology and Medicine (The University of Scranton, Scranton, Pa.) for preliminary sequence data from B. melitensis.

The protein sequencing (C.W.) was performed in the neurochemistry department of the Freie Universität Berlin (F. Hucho) and was supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. M.-T.A.-M. was supported by the FRM (Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale), by the Languedoc-Roussillon region. This work was supported by INSERM, by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, Ba 1416 2-2), and by an EGIDE/DAAD French-German exchange program (PROCOPE no. 00356UJ).

ADDENDUM

Since submission of this article, sequences of B. suis and B. melitensis genomes became available, thus allowing verification of some of the findings of this study. In the upstream region of B. suis chvE, no gene homologous to gbpR could be found. BLAST analysis using A. tumefaciens amino acid sequences of GbpR as input in the B. suis genome also did not give any hits over 30%, which is quite low compared to the 70% identities between the ChvE proteins of these two species. Finally, the homologous chvE gene found in the B. melitensis genome possesses a nucleotide sequence identical to that of B. suis chvE except for one missing base which, due to a frameshift, blocks the production of the complete ChvE protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ankenbauer R G, Nester E W. Sugar-mediated induction of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence genes: structural specificity and activities of monosaccharides. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6442–6446. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6442-6446.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel S F, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seichman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker B, Zambryski P, Staskawicz B, Dinesh-Kumar S. Signaling in plant-microbe interactions. Science. 1997;276:726–733. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns D L. Biochemistry of type IV secretion. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell A M, Tok J B, Zhang J, Wang Y, Stein M, Lynn D G, Binns A N. Xenognosin sensing in virulence: is there a phenol receptor in Agrobacterium tumefaciens? Chem Biol. 2000;7:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cangelosi G A, Ankenbauer R G, Nester E W. Sugars induce the Agrobacterium virulence genes through a periplasmic binding protein and a transmembrane signal protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6708–6712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caron E, Peyrard T, Köhler S, Cabane S, Liautard J-P, Dornand J. Live Brucella spp. fail to induce tumor necrosis factor alpha excretion upon infection of U937-derived phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5267–5274. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5267-5274.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charles T C, Doty S L, Nester E W. Construction of Agrobacterium strains by electroporation of genomic DNA and its utility in analysis of chromosomal virulence mutations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4192–4194. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.4192-4194.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comerci D J, Martinez-Lorenzo M J, Sieira R, Gorvel J-P, Ugalde R A. Essential role of the VirB machinery in the maturation of the Brucella abortus-containing vacuole. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:159–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook D M, Farzio K M, Burns D L. Identification and characterization of PtlC, an essential component of the pertussis toxin secretion system. Infect Immun. 1999;67:754–759. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.754-759.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbel M. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:213–221. doi: 10.3201/eid0302.970219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covacci A, Telford J L, Del Giudice G, Parsonnet J, Rappuoli R. Helicobacter pylori virulence and genetic geography. Science. 1999;284:1328–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selective suicide vector. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4310–4317. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4310-4317.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doty S L, Chang M, Nester E W. The chromosomal virulence gene, chvE, of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is regulated by a LysR family member. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7880–7886. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7880-7886.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekaza E, Guilloteau L, Teyssier J, Liautard J P, Köhler S. The ClpATPase ClpA of Brucella suis: cloning and characterization of the gene, and analysis of a knockout mutant in macrophages and in BALB/c mice. Microbiology. 2000;146:1605–1616. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-7-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essenberg R C, Candler C, Nida K. Brucella abortus strain 2308 putative glucose and galactose transporter gene: cloning and characterization. Microbiology. 1997;143:1549–1555. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-5-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foulongne V, Bourg G, Cazevieille C, Michaux-Charachon S, O'Callaghan D. Identification of Brucella suis genes affecting intracellular survival in an in vitro human macrophage infection model by signature- tagged mutagenesis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1297–1303. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1297-1303.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gay P, Le Coq D, Steinmetz M, Berkelman T, Kado C I. Positive selection procedure for entrapment of insertion sequence elements in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:918–921. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.918-921.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gay P, Le Coq D, Steinmetz M, Ferrari E, Hoch J. Cloning structural gene sacB, which codes for exoenzyme levansucrase of Bacillus subtilis: expression of the gene in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:1424–1431. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1424-1431.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong P C, Tsolis R M, Ficht T A. Identification of genes required for chronic persistence of Brucella abortus in mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4102–4107. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4102-4107.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang M-L, Cangelosi G A, Halperin W, Nester E W. A chromosomal Agrobacterium tumefaciens gene required for effective plant transduction. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1814–1822. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1814-1822.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jubier-Maurin V, Rodrigue A, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Layssac M, Mandrand-Berthelot M-A, Köhler S, Liautard J-P. Identification of the nik gene cluster of Brucella suis: regulation and contribution to urease activity. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:426–434. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.426-434.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemner J M, Liang X, Nester E W. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence gene chvE is part of a putative ABC-type sugar transport operon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2452–2458. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2452-2458.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Köhler S, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Layssac M, Teyssier J, Liautard J. Constitutive and inducible expression of green fluorescent protein in Brucella suis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6695–6697. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6695-6697.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Köhler S, Teyssier J, Cloeckaert A, Rouot B, Liautard J-P. Participation of the molecular chaperone DnaK in intracellular growth of Brucella suis within U937-derived phagocytes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:701–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovach M E, Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. pBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques. 1994;16:800–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lohrke S M, Nechaev S, Yang H, Severinov K, Jin S J. Transcriptional activation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence gene promoters in Escherichia coli requires the A. tumefaciens rpoA gene, encoding the α subunit of RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4533–4539. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4533-4539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikolaev V K, Leontovich A M, Drachev V A, Brodsky L I. Building multiple alignment using iterative dynamic improvement of the initial motif alignment. Biochemistry (Moscow) 1997;62:578–582. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Callaghan D, Cazevieille C, Allardet-Servent A, Boschiroli M L, Bourg G, Foulongne V, Frutos P, Kulakov Y, Ramuz M. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Ptl type IV secretion systems is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1210–1220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odenbreit S, Püls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng W-T, Lee Y-W, Nester E W. The phenolic recognition profiles of Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirA protein are broadened by high levels of the sugar binding protein ChvE. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5632–5638. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5632-5638.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porte F, Liautard J, Köhler S. Early acidification of phagosomes containing Brucella suis is essential for intracellular survival in macrophages. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4041–4047. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4041-4047.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rauhut R, Klug G. mRNA degradation in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23:353–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sangari F, Aguero J. Molecular basis of Brucella pathogenicity: an update. Microbiologica Semin. 1996;12:207–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.SantaLucia J., Jr A unified view of polymer, dumbbell, and oligonucleotide DNA nearest-neighbor thermodynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1460–1465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt-Eisenlohr H, Domke N, Angerer C, Wanner G, Zambryski P, Baron C. Vir proteins stabilize VirB5 and mediate its association with the T pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7485–7492. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7485-7492.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmiederer M, Anderson B. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of three Bartonella henselae genes homologous to Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB region. DNA Cell Biol. 2000;19:141–147. doi: 10.1089/104454900314528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimoda N, Toyoda-Yamamoto A, Aoki S, Machida Y. Genetic evidence for an interaction between the VirA sensor protein and the ChvE sugar-binding protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26552–26558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stachel S E, Zambryski P C. virA and virG control the plant-induced activation of the T-DNA transfer process of A. tumefaciens. Cell. 1986;46:325–333. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Bastelaere E, Lambrecht M, Vermeiren H, Van Dommlen A, Keijers V, Proost P, Vanderleyden J. Characterization of a sugar binding protein from Azospirillum brasilense mediating chemotaxis to and uptake of sugars. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:703–714. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]