Abstract

Issue addressed

Prevention approaches specific to prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) and foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) have been identified as urgently needed in Australia, including in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. However, very little work has aimed to describe and evaluate health promotion initiatives, especially those developed in rural and remote areas.

Methods

A series of television commercial scripts (scripts) were developed with health promotion staff at an aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Health Service and piloted with 35 community members across six yarning sessions.

Results

Scripts evoked responses in line with two predominant themes: “Strength” and “Community resonance.” This process led to the development of a four‐part television and radio campaign focusing on a life course approach to prevent prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) – “Vision,” “Future,” “Cycle” and “Effect.”

Conclusions

Intergenerational influences on PAE were key elements of scripts positively received by community members. Strengths of this work included a flexible approach to development, local aboriginal men and women coordinating the yarning sessions, and the use of local actors and familiar settings.

So what?

Preventing PAE is extraordinarily complex. Initiatives that are culturally responsive and focus on collective responsibility and community action may be crucial to shifting prominent alcohol norms. Future work is necessary to determine the impact of this campaign.

Keywords: alcohol drinking, foetal alcohol spectrum disorders, health promotion, indigenous peoples, pregnancy, public health

1. INTRODUCTION

Alcohol exposure at any time during pregnancy may cause harm to the developing foetus, resulting in an increased risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, pre‐term birth, congenital anomalies, low birth weight and foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). 1 FASD is a diagnostic term for severe neurodevelopmental impairments resulting from alcohol exposure before birth. FASD represents a range of cognitive, behavioural and physical impairments and is a leading preventable cause of intellectual disability. 2 , 3 Individuals with a FASD diagnosis display impairments across a wide range of neurocognitive domains, including attention, memory, language, executive function, cognition, motor skills and affect regulation. 4 Current Australian diagnostic criteria for FASD include: (a) FASD with three sentinel facial features and (b) FASD with less than three sentinel facial features. 5 These categories replace the previously used diagnoses of foetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), partial foetal alcohol syndrome (pFAS), and Neurodevelopmental Disorder‐Alcohol Exposed (ND‐AE). 6

Recent data suggest that 35% of Australian women consume alcohol during pregnancy, which has declined from 50% reported in 2010. 7 However, the prevalence of FASD in Australia is currently unknown. A 2008 study using prospective national data on FAS 8 reported rates of 0.06 per 1000 live births. 9 More recent data collected using active case ascertainment methods amongst Australian high‐risk groups has demonstrated some of the highest rates of FASD world‐wide. 10 , 11 Addressing and preventing PAE and FASD has been a priority of the national government 12 since 2011 when a Federal parliamentary inquiry led to the release of two Commonwealth Action plans 12 , 13 supported by funding to progress the plans.

Similarly, in the Northern Territory (NT), the NT government has called for action to address FASD, reporting that many NT children exhibit learning difficulties, have challenges with regulating emotions, and are frequently involved with the juvenile justice system. 14 Data from the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) demonstrates the NT has the highest proportion of developmentally vulnerable children across Australia. 15 However, these behaviours and indicators are not unique to FASD. 6 FASD prevalence in the NT is unknown. An early study conducted via a retrospective review of medical records reported FAS prevalence of 0.68 per 1000 live births in the top end of the NT. For Indigenous children, FASD prevalence was estimated between 1.87 and 4.7 per 1000 live births. 16 Clinic‐reported data from the Child and Youth Assessment and Treatment Service at Central Australian Aboriginal Congress reported providing services to 174 children (aged 0‐18 years) in the 2019/2020 financial year. Of these children 36 were diagnosed with FASD. (Personal commun., 2020).

Whilst there is no data available for prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE), the NT has the highest reported rates of general alcohol consumption in Australia. 7 Over 8% of people aged 14 years and over reported drinking alcohol daily (compared to 5% Australia wide). In 2019, over 15% of women in the NT reported alcohol consumption in excess of lifetime risk guidelines; and 14% of women reported alcohol consumption in excess of single occasion risk guidelines weekly. For men, these proportions are twofold. 7 For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in the NT, a single occasion risk of harm is especially problematic; 19% for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and 33.7% for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. 17 There have been significant improvements in alcohol consumption noted over the last decade with a package of evidence‐based alcohol reforms. 18 , 19 , 20 This has included a 50% decrease in per capita consumption of cask wine 12 months after the introduction of a minimum unit price on alcohol. 20

Health promotion can offer effective ways to reduce the burden of disease and mortality experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, while also contributing to an increase in health equity and social justice. 21 Prevention approaches specific to PAE and FASD have been identified as urgently needed in Australia, including in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. 10 Targeted initiatives for high‐risk groups are vital and must be culturally responsive, community‐led and informed and consistent with national guidelines. 22

Despite the clear call for action, there is a significant lack of research that adequately describes or evaluates PAE and FASD prevention efforts. 23 , 24 , 25 In their systematic review, Symons et al 24 found little evidence internationally for interventions aiming to reduce PAE or FASD in Indigenous populations. Williams et al 26 reviewed online Australian FASD prevention resources and found over 100 resources relevant to Indigenous Australians with the majority targeting pregnant women or women of child‐bearing age. No resources were designed specifically for men, grandmothers or “aunties” (an Aboriginal term describing a female Elder). This review suggests there is a focus on women as primarily responsible for preventing prenatal alcohol exposure. However, men, grandmothers and aunties are crucial social networks that can have an enormous influence on pregnant women's alcohol consumption. 27

FASD is a social issue with systemic causes; hence, communicating the risks of PAE is complex. Conceptualising prenatal alcohol consumption (and FASD) as an individual choice leads to and perpetuates stigma. 28 Collective responsibility and action are necessary to change prominent norms around alcohol 29 and avoid stigmatising women or other groups. Prevention initiatives that are culturally responsive, reflect the worldviews of the target group and incorporate diverse socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds are, therefore, likely to be most effective in preventing PAE and FASD. 14 , 30

The aim of this project was to develop a health promotion campaign to prevent prenatal alcohol exposure in Alice Springs, NT. Alice Springs is a central Australian hub with a population of almost 25,000 people (17.6% of whom identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander). 31 The partner Aboriginal Medical Service delivers services to more than 17,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in Alice Springs and remote communities across Central Australia. Alcohol is a major presenting problem and is a particularly sensitive and complex issue. Reasons for this include the legacy of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (“The Intervention”), a suite of measures implemented in the NT in 2007 in response to the Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle Report (“Little Children are Sacred Report”). One of the measures implemented as part of “The Intervention” was restricting the sale, consumption, and purchase of alcohol in prescribed areas. This legislation made collection of information compulsory for purchases over a certain amount and the introduction of new penalty provisions. 32 A process of external governance and control led to enormous mistrust in government and left a negative legacy on psychological wellbeing – including the spirituality and cultural integrity of the people it aimed to serve. 33 In recognising the importance of complex factors contributing to the accumulation of risk, 34 , 35 and the significant gap in resources targeting external influences of PAE, 26 a life course approach and participatory methods were employed to develop the campaign. The campaign incorporated the roles of men, health services and the broader community to construct a story about the healthy development of a young man beginning prior to conception. This paper reports on the process of development, piloting of content and implementation of the campaign.

2. METHODS

2.1. Script development

In late 2018, the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service health promotion team developed a series of scripts and production schedules for four health promotion television commercials (TVCs) addressing alcohol use, PAE and FASD. The scripts were designed to portray a life course journey from planning a pregnancy, to conception, birth and the development of a healthy young man (see supplementary information for details on each script). Script concepts were informed by the professional expertise of the team and local understandings of alcohol consumption in the community and used culturally appropriate language and portrayals of relationships and interactions. The original scripts were also reviewed by an expert review panel including researchers working in the FASD field and representatives from the not‐for‐profit sector working with families, carers and people living with FASD. Scripts were reviewed and edited using an iterative approach over a period of approximately nine months. The reviewing process was undertaken to ensure the accuracy, appropriateness and relevance of the script information.

2.2. Piloting and revisions through yarning

Yarning sessions were undertaken to pilot the scripts with community members in Alice Springs, to ensure resonance and acceptability with the target audience. Purposive sampling was used to recruit 35 participants to engage in the groups. To participate individuals had to be 18 years of age or older, identify as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander descent, and not pregnant at the time of the sessions. Pregnant women were excluded from the research due to cultural guidance about the potential for causing harm. Verbal consent was sought, and clear informed consent processes undertaken. There was no incentive for participation.

Six yarning sessions of approximately an hour each took place between June and October of 2019. Yarning is a culturally appropriate and acceptable communication method within health practices and health practice settings. 36 In research yarning, “a topic is introduced in a deliberately open manner, and the yarning participants can then take that topic and respond as they see fit, rather than feeling that they are being interviewed or formally questioned”. 37 Yarning sessions aim to establish a relationship, build trust and make participants feel comfortable and secure. 36 To put participants at ease during the sessions, the team used their personal experiences to demonstrate an understanding of the barriers around talking about grog because they have also experienced the negative impacts of alcohol. The yarning sessions were semi‐structured with staff reading all scripts and yarning with participants about alcohol and how it affects them and their families. A series of semi‐structured questions were initially developed with researchers to prompt conversation (eg, “how does this story make you feel,” “What message/s do you take away from the story,” “Who do you think might be impacted by the ad?”). However, staff found that yarning with participants led to these enquiries in a more comfortable and natural manner. During the yarning sessions, visual aids such as posters were used to constructively tell the campaign story. Groups were separated by gender and sessions were not recorded due to concerns about preserving anonymity. Notes from the yarning sessions were documented and grouped according to general conversation themes. Once this was completed, the broader team workshopped the findings to look for patterns in the data and gain consensus on the findings. Ethics approval for the use of data associated with this research was obtained via the Central Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (#CA‐20‐3637).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Yarning sessions

The results of the yarning sessions are described below, structured under two main themes that emerged following analysis and review; strength; and community resonance.

-

Strength

Most of the yarning group participants described that they felt a sense of strength and determination whilst listening to the TVC scripts and that it gave them a good feeling. There were differences in the ways men and women described how the scripts made them feel. Women tended to provide more descriptive discussion while men provided succinct answers.

“Good. Tell them not to go to the pub.” Male, Group 4)“Happy – young fella strong enough to say no.” (Female, Group 2)

“Powerful and uplifting, seeing them working as a family / family partnership.” (Female, Group 6)

Clear and strong. Makes me feel supported (Female, Group 3)

In particular, the tagline presented at the end of the scripts, “Drinking grog when pregnant can cause Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). Grog during and after pregnancy is No Good for Dad, Mum and Bub,” was received very positively with most participants stating the phrase was clear and strong:

“Clear and strong message – no grog while pregnant. Makes a very good feeling as the last thing in the ad.” (Male, Group 4)

“Clear, strong last message. Creates good feeling, for the young ones.” (Male, Group 4)

“It’s good. Message is clear and strong.” (Female, Group 1)

Many participants felt that alcohol drinking is a problem in and around Alice Springs. However, there was a general sense of strength arising from the whole community working to reduce alcohol‐related harms. Saying no to grog evoked a sense of pride and demonstrated a positive future for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.

“People are proud of you.” (Female, Group 1)

“Proud feelings, because they’re walking away.” (Female, Group 6)

“Aboriginal family being strong and not letting alcohol be part of their lives.” (Female, Group 2)

Similarly, participants commented positively on the characters who said no to grog throughout the scripts. This included strong respect for a female character in one script for not bringing grog into the household. Participants felt that saying no to grog should be supported by older community members. Male participants commented that young couples needed to “take responsibility” for their actions with alcohol.

“Young fella saying no to alcohol and having his parents support him.” (Female, Group 2)

“You can say no to grog.” (Male, Group 5)

“It’s okay to say no.” (Female, Group 1)

“You can’t help someone who don’t help themselves.” (Male, Group 4)

Community Resonance

Participants identified the characters described in the scripts as representative of their own community. Almost all participants stated “Yes” or “Absolutely” when asked if the characters described sounded like people in their families or communities.

“Sounds like people in our community…” (Male, Group 4)

“Can relate. First scene is good – because I’ve seen family drinking.” (Female, Group 3)

“It’s everyday life in Alice Springs.” (Male, Group 4)

Participants yarned about who would receive the most benefit from the advertisements. Responses included pregnant women, young kids, men, family members, grandparents, young parents and everyone. Reasons for this were as follows:

“Grandparents and young people, because they support each other.” (Male, Group 5)

“Women (particularly pregnant women) – because they will understand the benefits. But also families – family support is important when pregnant. And kids ‐ Because they will understand that parents do what they do for them and their futures!” (Female, Group 2)

“Older men – everyone!” (Female, Group 6)

For female participants, the benefits for family were consistently emphasised and the link to pregnancy was openly discussed. Male participants referenced the benefits of no grog for families but discussed the role of alcohol in other areas of life.

“… it causes fights.” (Male, Group 4)

“Grog makes you not fit especially if you play sports.” (Male, Group 5)

“Family support is important when pregnant… parents do what they do for them (kids) and their futures.” (Female, Group 2)

“Yes – family because we don’t normally plan (pregnancy) and this would show what a healthy relationship is.” (Female, Group 3)

Yarning participants recognised the role of men in the scripts as crucial to the campaign. The male characters were described as respectful, strong and supportive. It was noted that the involvement of men saying no to grog was positive.

“Excited. It shows good men in the limelight.” (Female, Group 1)

“Clear strong lasting message [at the end]. Dad should say it.” (Female, Group 1)

Good, because it targets young fellas and because he playing football not drinking (Male, Group 4).

“Men can support wives when they are pregnant.” (Male, Group 5)

One group of female participants specifically commented on how the actors should look in the campaign. This included having women with light skin and coloured eyes. Participants wanted it to be clear that FASD does not discriminate and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people “can look different.” There were also references to cultural indicators of having strong Aboriginal men from Central Australia in the campaign.

3.2. Development and implementation of TVCs and radio advertisements

Filming of the TVCs occurred in the local community during November 2019 at recognisable settings including a sports oval, and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service premises. Local community members were contracted as talent. The project team were present at each filming session to monitor the process and to ensure that scripts were followed according to the results of the yarns. Filming took four days to complete and was finalised in early 2020.

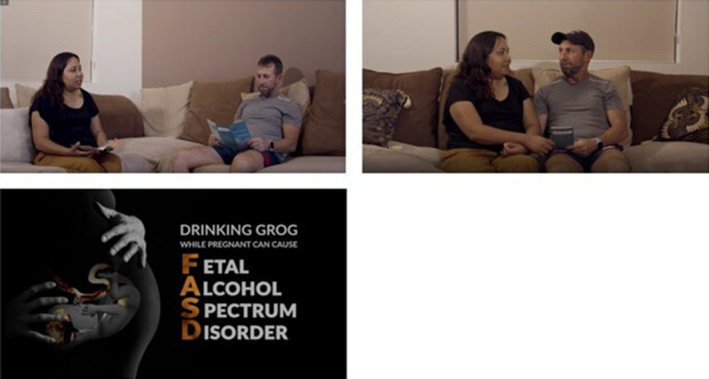

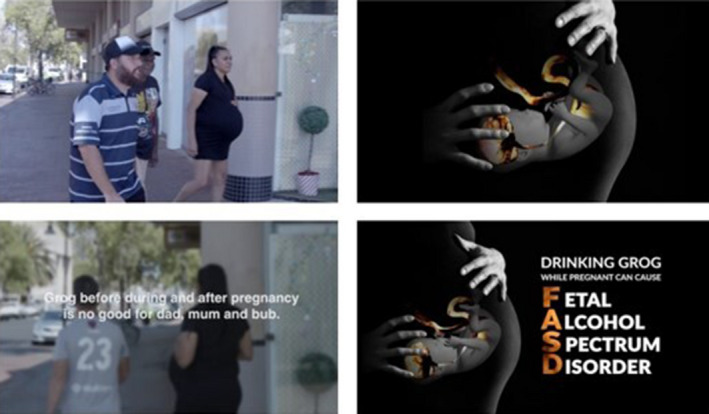

The TVCs were launched in late March 2020, appearing on three local television stations. All TVCs appeared on the television between 6 PM and 10 PM and were shown during the broadcast of popular commercial television programs and news programs. The TVCs were shown a total of 73 times during an initial 10‐week run. Radio advertisements were developed with the same talent team and launched in June 2020. Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 illustrate stills from the four TVCs which were named: The Vision – (planning), The Future – (conception), The Cycle – (born) and The Effect – (grown up).

FIGURE 1.

Television commercial 1 (The Vision – Planning)

FIGURE 2.

Television commercial 2 (The Future – Conception)

FIGURE 3.

Television commercial 3 (The Cycle – Born)

FIGURE 4.

Television commercial 4 (The Effect – Grown Up)

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this project was to develop a health promotion campaign for the prevention of alcohol use in pregnancy.

Yarns revealed that scripts were positively received, suggesting that the life course approach developed by the team was relevant in this setting. Drawing on community strengths and having the pride to say no to grog resonated with community participants. Local talent and familiar and recognisable settings increased the acceptability of scripts, in line with culturally appropriate ways of working in health promotion in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. 39 Descriptions of men playing positive and leading roles in preventing alcohol use during pregnancy were seen as a key element of the scripts, and a positive feature of the stories. Participants felt the scripts had a strong community focus and the potential to resonate with many community members who can influence prenatal alcohol exposure. These findings demonstrate the importance of targeting influential others at different life stages for PAE and FASD health promotion efforts. Yarns also revealed that participants found it easy to identify the characters and scenarios portrayed in the scripts as representative of those from their own communities.

There were clear differences in the ways men and women responded to the scripts. Women articulated the importance of social support during pregnancy and the benefits of a healthy pregnancy for their families. Men acknowledged the benefits of no grog for pregnancies but tended to describe the impacts of grog generally. This finding is likely due to the differences between men's and women's business in traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, 38 and the direct benefits of alcohol‐free pregnancies for women. However, there was a consistent message that the entire community are responsible for alcohol‐free pregnancies with clear benefits for families.

As a result of the focus groups, minor modifications were made to wording and taglines in the TVCs, and considerations were made for the talent sourced. The results also reinforced the choice of scenes and the scope of the campaign. For example, participants’ comments that the story could be demonstrated through a particularly relatable BBQ scene were employed. The pitfalls of alcohol drinking discussed by male participants were demonstrated in TVC One “The vision” and reinforced the grog‐free choices made by the leading couple planning a pregnancy. Positive commentary received about couples planning healthy pregnancies reinforced the scope of the campaign. Strengths of this process that are key to the successful development and implementation of this project include oversight and guidance by the local Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service. The structure of the research and project teams and the use of culturally sensitive methods to engage community members is a further strength of the development process. Flexibility and willingness of all team members to adapt their ways of working enabled the sharing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge and ways of doing.

There are some limitations to the methodology employed in this research. The sessions were not recorded and relied heavily on note‐taking, with notes consolidated upon completion. At times, this approach may have resulted in the recording of shortened answers. Local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women coordinating the research provided a secure and comfortable environment for participants to speak freely and openly about how they felt about grog. However, in some cases, this may have influenced the questions asked of participants. Prioritising the comfort of participants was critical to obtaining feedback with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers noting there may be a reluctance to talk about grog in the community, for fear of being judged and reported. This was understood to be due to the adverse implications of government policies, interventions and research.

4.1. Conclusion

Guided by health service staff and community members, this project resulted in a life course approach to the prevention of prenatal alcohol exposure. An evaluation of the TVCs will more broadly assess its reach and impact within the local community. There is a paucity of published research on health promotion approaches to alcohol use in pregnancy and the prevention of FASD (in both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non‐Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contexts). Conducting implementation research in regional and remote areas can present financial and logistical barriers, and health promotion efforts in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander contexts can be hampered by language and cultural differences. 24 A strength of this work has been the direct leadership of community men, women, and health promotion staff. Perhaps best summarised by Dr Carrie Bourassa (2017, p. 7), a first nations researcher who integrates traditional knowledge and cultures into research methods “If you don't have community engagement, if you don't have Indigenous people in the driver's seat, you don't have Indigenous knowledge translation. 40 ”

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the Making FASD History Program Steering Committee for guiding the work of the program and supporting the work associated with this publication. We also wish to gratefully acknowledge and thank the Alice Springs community members who participated in the development of these advertisements, and Ms Annalee Stearne, previous Program Manager and Dr Tania Gavidia, previous Research Officer.

Lemon D, Swan‐Castine J, Connor E, van Dooren F, Pauli J, Boffa J, et al. Vision, future, cycle and effect: A community life course approach to prevent prenatal alcohol exposure in central Australia. Health Promot J Austral. 2022;33:788–796. 10.1002/hpja.547

Handling editor: James Smith

Funding information

This study was supported by the Australian Government Department of Health (grant number H1617G038).

REFERENCES

- 1. Bailey BA, Sokol RJ. Prenatal alcohol exposure and miscarriage, stillbirth, preterm delivery, and sudden infant death syndrome. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34(1):86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mather M, Wiles K, O’Brien P. Should women abstain from alcohol throughout pregnancy? The. BMJ. 2015;h5232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khoury JE, Milligan K, Girard TA. Executive functioning in children and adolescents prenatally exposed to alcohol: a meta‐analytic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2015;25(2):149–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mattson SN, Bernes GA, Doyle LR. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a review of the neurobehavioral deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(6):1046–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bower C, Elliot E. Report to the Australian Government of Health: Australian Guide to the diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). 2016.

- 6. Bower C, Elliott EJ, Zimmet M, Doorey J, Wilkins A, Russell V , et al. Australian guide to the diagnosis of foetal alcohol sprectrum disorder: a summary. J Paediatr Child Health. 2017;53(10):1021–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Canberra: AIHW; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stratton K, Howe C, Battaglia F. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elliott EJ, Payne J, Morris A, Haan E, Bower C. Fetal alcohol syndrome: a prospective national surveillance study. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(9):732–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fitzpatrick JP, Latimer J, Olson HC, Carter M, Oscar J, Lucas BR, et al. Prevalence and profile of Neurodevelopment and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) amongst Australian Aboriginal children living in remote communities. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;65:114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bower C, Watkins RE, Mutch RC, Marriott R, Freeman J, Kippin NR, et al. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study among young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e019605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Commonwealth of Australia Department of Health . National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Strategic Action Plan 2018‐2028. In: Health CDo, editor. Canberra: 2018. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/national‐fasd‐strategic‐action‐plan‐2018‐2028.pdf.

- 13. Australia Co . National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Action Plan. 2014. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/health‐mediarel‐yr2014‐nash031.htm

- 14. NT Department of Health . Addressing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) in the Northern Territory 2018‐2024. NT Department of Health; 2018.

- 15. Commonwealth of Australia . Australian Early Development Census National Report 2018. Canberra: Department of Education and Training; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harris KR, Bucens IK. Prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome in the Top End of the Northern Territory. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39(7):528–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Alcohol, tobacco and other drug use in Australia 2020.

- 18. Symons M, Gray D, Chikritzhs T, Skov SJ, Saggers S, Boffa J, et al. A longitudinal study of influences on alcohol consumption and related harm in Central Australia: with a particular emphasis on the role of price. National Drug Research Institute. 2012.

- 19. Wright C, McAnulty GR, Secombe PJ. The effect of alcohol policy on intensive care unit admission patterns in Central Australia: a before–after cross‐sectional study. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2021;49(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taylor N, Miller P, Coomber K, Livingston M, Scott D, Buykx P, et al. The impact of a minimum unit price on wholesale alcohol supply trends in the Northern Territory, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2021;45(1):26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCalman J, Tsey K, Bainbridge R, Rowley K, Percival N, O'Donoghue L, et al. The characteristics, implementation and effects of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health promotion tools: a systematic literature search. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elliott EJ. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in Australia – the future is prevention. Public Health Res Pract. 2015;25(2):4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Conigrave K, Freeman B, Caroll T, Simpson L, Kylie Lee KS, Wade V, et al. The Alcohol Awareness project: community education and brief intervention in an urban Aboriginal setting. Health Prom J Austr. 2012;23(3):219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Symons M, Pedruzzi RA, Bruce K, Milne E. A systematic review of prevention interventions to reduce prenatal alcohol exposure and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in indigenous communities. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ospina M, Moga C, Dennett L, Harstall C. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Prevention Approaches for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. In: Clarren S, Salmon A, Jonsson E, editors. Prevention of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder FASD. Hoboken, US: Wiley; 2011. p. 99–335. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williams HM, Percival NA, Hewlett NC, Cassady RBJ, Silburn SR. Online scan of FASD prevention and health promotion resources for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Health Prom J Austr. 2018;29(1):31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McBride N, Johnson S. Fathers’ Role in Alcohol‐Exposed Pregnancies: Systematic Review of Human Studies. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(2):240–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fond M, Kendall‐Taylor N, Volmert A, Gertein Pineau M, L’Hôte E. Seeing the spectrum: Mapping the gaps between expert and public understandings of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in Manitoba. Washington, DC: Frame Works Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gibson S, Nagle C, Paul J, McCarthy L, Muggli E. Influences on drinking choices among Indigenous and non‐Indigenous pregnant women in Australia: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0224719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gould GS, McEwen A, Watters T, Clough AR, van der Zwan R. Should anti‐tobacco media messages be culturally targeted for Indigenous populations? A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Tobacco Control. 2013;22(4):e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2016 Census QuickStats. Australia. 2017. https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/7

- 32. Monash University . What is the Northern Territory Intervention? https://www.monash.edu/law/research/centres/castancentre/our‐areas‐of‐work/indigenous/the‐northern‐territory‐intervention/the‐northern‐territory‐intervention‐an‐evaluation/what‐is‐the‐northern‐territory‐intervention

- 33. The NT ‘Intervention’ led to some changes in Indigenous health, but the social cost may not have been worth it [Internet]. The Conversation 2017. https://theconversation.com/the‐nt‐intervention‐led‐to‐some‐changes‐in‐indigenous‐health‐but‐the‐social‐cost‐may‐not‐have‐been‐worth‐it‐78833.

- 34. Weeramanthri T, Hendy S, Connors C, Ashbridge D, Rae C, Dunn M, et al. The Northern Territory Preventable Chronic Disease Strategy‐promoting an integrated and life course approach to chronic disease in Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2003;26(3):31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Priest N, Mackean T, Waters E, Davis E, Riggs E. Indigenous child health research: a critical analysis of Australian studies. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2009;33(1):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lin I, Green C, Bessarab D. ‘Yarn with me’: applying clinical yarning to improve clinician–patient communication in Aboriginal health care. Austr J Prim Health. 2016;22(5):377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fletcher G, Fredericks B, Adams K, Finlay S, Andy S, Briggs L, et al. Having a yarn about smoking: Using action research to develop a ‘no smoking’policy within an Aboriginal Health Organisation. Health Policy. 2011;103(1):92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dudgeon P, Milroy H, Walker R, Research TIfCH, Network KR, Australia UoW , et al. Working together: aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. [Perth]: [Perth]: Australian Government, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2014.

- 39. Demaio A, Drysdale M, de Courten M. Appropriate health promotion for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: crucial for closing the gap. Global Health Prom. 2012;19(2):58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bourassa C. Research as noojimo mikana: creating pathways to culturally safe care for indigenous people. Australia: Brisbane; 2017. [Google Scholar]