Abstract

Objective

This study explored relationships between aggressive script rehearsal, rumination, and anger rumination with aggressive behavior.

Method

One hundred and twenty‐nine incarcerated males (M = 33.54, SD = 8.67) completed the Schedule of Imagined Violence, Preservative Thinking Questionnaire, Anger Rumination Scale, and the Life History of Aggression‐Aggression subscale. Correlations were run to examine associations between the variables and a four‐step sequential multiple regression was performed to assess for the unique contribution of rumination, anger rumination, and aggressive script rehearsal to aggressive behavior.

Results

Results revealed moderate‐strong positive associations between aggressive script rehearsal, rumination, and anger rumination. Moderate‐weak associations were found between these three constructs and aggressive behavior. Regression analyses revealed aggressive script rehearsal was uniquely related with aggressive behavior and path analysis demonstrated aggressive script rehearsal mediated the relationship between rumination/anger rumination and aggression.

Conclusion

These results clarify the nature of the relationships between these conceptually connected constructs and suggest that the frequency with which someone rehearses aggressive scripts impacts on the likelihood of aggression more than anger rumination and general ruminative processes. The frequency with which a person rehearses aggressive scripts should be a critical consideration in violence risk assessment and treatment programs for people deemed to be at risk for violent behavior.

Keywords: aggression, fantasy, rumination, scripts, violent offenders

1. INTRODUCTION

Antisocial cognition is a key risk factor for aggressive behavior (Andrews & Bonta, 2010); several theories and models of aggression, including cognitive neoassociation theory (Berkowitz, 2012), social learning theory (Akers & Jennings, 2015), script theory (Huesmann, 1988), social interaction theory (Tedeschi & Felson, 1994), and the general aggression model (GAM; Anderson & Bushman, 2002), all suggest that cognition is critical to the development, activation, and maintenance of aggressive behavior. The GAM (Anderson & Bushman, 2002) incorporates script theory (Huesmann, 1988) and highlights the particularly important role of aggressive script rehearsal to aggressive behavior. Aggressive scripts are stereotyped aggression‐related event sequences (Gilbert & Daffern, 2017) that define social situations, prepare people for action, and guide aggressive behavior (Huesmann, 1988). According to Huesmann (1998), individuals appraise the social situations they find themselves in, retrieve and review scripts to guide their behavior, and act according to the script they decide is most appropriate. Associations between the frequency of aggressive script rehearsal and aggressive behavior have been revealed in numerous studies (Daff et al., 2014; Gilbert et al., 2013; Grisso et al., 2000; Hosie et al., 2021; Nagtegaal et al., 2006; Podubinski et al., 2017).

Aggressive script rehearsal overlaps conceptually with violent fantasy, rumination, and angry rumination, and these terms are often used interchangeably without consideration of their differences (Gilbert & Daffern, 2017). Instruments that purportedly measure these constructs are confounded, and this obscures distinctions between the constructs and hampers elucidation of these constructs' relationships with aggressive behavior. Deconstruction of these instruments and concurrent examination of the associations between these constructs and aggression has not been undertaken. This is important to ensure precise measurement and improved violence risk assessment. This paper clarifies these constructs and examines their relationship with aggression.

2. AGGRESSIVE SCRIPTS, FANTASY, AND RUMINATION

Conceptual ambiguity between aggressive scripts, rumination, and fantasy is unsurprising given key researchers have used the terms together in seemingly unclear ways. For example, Huesmann and Eron (1989) reference the development of aggressive scripts in children in the following manner: “To maintain a script in memory, a child probably has to rehearse it from time to time. The rehearsal may take several different forms from simple recall of the original scene, to fantasizing about it, to play acting. The more elaborative, ruminative type of rehearsal characteristic of children's fantasizing is likely to generate greater connectedness for the script, thereby increasing its accessibility in memory” (p. 102). Here, rumination and fantasizing seem to refer to the process of rehearsal and elaboration of the script, whereas the term script denotes the content or action being considered. This is consistent with Nolen‐Hoeksema et al.'s (2008) multidimensional definition of rumination, and its emphasis on rumination as a nonspecific process, “We define rumination, however, as the process of thinking perseveratively about one's feelings and problems rather than in terms of the specific content of thoughts” (p. 400). Accordingly, rumination and fantasizing represent the process of perseverative thinking and the aggressive script itself is the action being considered. Like the similarity between rumination and fantasizing, Rokach (1990) describes fantasy as a thought process that results in a mental picture of organized events forming a script in which the participant plays a role. Accordingly, the process of “fantasizing” results in what some authors refer to as a “fantasy,” which closely resembles the script construct and describes the action being contemplated or “fantasized” (Gilbert & Daffern, 2010). The process of rehearsing aggressive fantasies, like aggressive scripts, is associated with aggressive behavior (C. E. Smith et al., 2009). In summary, there is considerable overlap between the process of fantasizing/rumination and the product (i.e., the script/fantasy) of these rehearsal and elaboration processes.

Contrasting with the somewhat limited empirical research base on aggressive scripts, which has focused almost exclusively on the relationship between the frequency of script rehearsal and aggression, some attention has been given to the relationship between rumination and aggression (e.g., Denson, 2013). Rumination is a multidimensional cognitive process involving repetitive thinking. It occupies mental capacity, sustains uncomfortable emotions, and inhibits an individual's ability to problem‐solve and act (Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., 2008). The content of ruminative thinking is generally focused on issues of self‐worth, meaning, and themes of loss, and it is typically intrusive and perceived as distressing (Nolen‐Hoeksema, 1991; Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., 2008). Research has demonstrated that rumination is associated with depression and anxiety (McLaughlin & Nolen‐Hoeksema, 2011) and that it also mediates the relationship between internalized disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression) and aggression (McLaughlin et al., 2014). However, rumination is a cognitive process that is not content‐specific (Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., 2008). Research exploring the specific content that relates to aggression has found that anger rumination (Bushman, 2002; Denson, 2013; Sukhodolsky et al., 2001) or provocation‐focused rumination (Pedersen et al., 2011) is associated with aggression (DeWall et al., 2007), but rumination focusing on other content, such as sadness rumination, is not (Peled & Moretti, 2010).

Anger rumination has been described as the repetitive thoughts that an individual has about the experience of anger, with such thoughts believed to sustain and amplify anger (Bushman, 2002; Sukhodolsky et al., 2001). Bushman et al. (2005) proposed that ruminating about a past anger‐provoking event increases the likelihood of aggressive behavior, surmising that rumination maintains a person's feelings of anger and primes aggression‐related thoughts, which in turn can increase the likelihood of an aggressive behavioral response. Pedersen et al. (2011) elaborates the concept of anger rumination by drawing attention to differences between self‐focused and provocation‐focused rumination. With self‐focused rumination attention is directed inward to one's own negative emotions. Negative affect resulting from this type of rumination can generate frustration and result in displaced aggression. This contrasts with provocation‐focused rumination, which is rumination that follows provocation where there is a focus on anger and the development of plans to retaliate. These plans for retaliation are in our opinion best referred to as aggressive scripts and are consistent with Denson's (2013) suggestion that “angry rumination allows one to mentally 'practice revenge.' Mental stimulation of vengeance may create a cognitive script whereby it becomes easier to harm others when the moment is right. Thus, creating violent scripts through mental stimulation may lower barriers to aggression” (p. 114). This definition separates scripts from the past‐oriented process of rumination about the perceived provocation, specifies their content (plans for retaliatory action), and their function (preparing for retaliation, and potentially downregulation of negative emotions, Sheldon & Patel, 2009). Critically, not all anger‐rumination leads to aggressive script rehearsal; according to Sukhodolsky et al. (2001), with reference to anger‐rumination, “memories of past anger episodes can trigger new episodes of state‐anger, attention to anger experience can lead to amplification of its intensity and duration, and counterfactual thoughts may be [emphasis added] related to action tendencies towards resolution or retaliation” (p. 690).” This suggests that it is only when there are thoughts of revenge, in the form of aggressive cognitive scripts, that anger rumination increases aggression propensity.

3. MEASURING AGGRESSIVE SCRIPTS, RUMINATION, AND ANGER RUMINATION

The complex and overlapping nature of scripts, rumination, and fantasy has resulted in confounded measurement instruments. Since rumination and fantasizing are processes involving repetitive thoughts that are not content‐specific (Nolen‐Hoeksema et al., 2008), measurement instruments that focus exclusively on these generic processes may be related to aggression, particularly when used in studies of aggressive populations, because these generic processes will be common to people who rehearse aggressive scripts (which are common in offender populations, Hosie et al., 2021); however, the strength of the relationship between these generic measures of rumination and aggression is likely to be weak when compared to measures comprising aggression specific content. For example, the Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ, Ehring et al., 2011), includes general rumination‐focused statements such as “My thoughts repeat themselves” and “My thoughts take up all of my attention”; these thoughts are not necessarily related to the rehearsal of aggressive scripts or to aggressive behavior (e.g., “My [violent] thoughts repeat themselves” would relate to aggression but “My [sad] thoughts repeat themselves” is unlikely to relate to aggressive behavior). Similarly, measures assessing the frequency of ruminative thought that are entrenched in content that is specific to a particular disorder that is unrelated to aggression (e.g., depression) may not capture the thought processes and content that is pertinent to aggressive behavior. For example, the Ruminative Response Scale (Nolen‐Hoeksema, 1991) measures rumination of depressed mood and the Rumination Interview (Michael et al., 2007) measures repeated thoughts that are relevant to post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, measurement instruments that capture content concerning retaliation and aggressive scripts are likely to be more strongly related to aggressive behavior (Peled & Moretti, 2010).

Sukhodolsky et al.'s (2001) Anger Rumination Scale (ARS) measures a person's propensity to think about the emotion of anger, to recall experiences of anger, and to examine the etiology, significance, and outcomes of anger. It includes questions associated with four anger rumination facets, (1) angry afterthoughts (e.g., “I re‐enact the anger episode in my mind after it happens”), (2) angry memories (e.g., “I keep thinking about events that angered me for a long time”), (3) understanding of causes (e.g., “I analyze events that make me angry”), and (4) thoughts of revenge (e.g., “When someone makes me angry I can't stop thinking about how to get back at this person”). The ARS appears to assess the key features of provocation‐focused rumination with aggressive retaliatory scripts measured by the “thoughts of revenge” subscale. In adult student samples, the ARS has been found to correlate strongly with self‐reported trait aggression (Anestis et al., 2009; Maxwell et al., 2007), and aggression in child and gang‐affiliated male youth samples (S. D. Smith et al., 2016; Vasquez et al., 2012).

The Schedule of Imagined Violence (SIV, Grisso et al., 2000) is the dominant measure for assessing aggressive script rehearsal. It comprises questions about thoughts of hurting or injuring other people. Typically, the SIV has been used to measure the frequency of aggressive script rehearsal (i.e., “How often do you have thoughts about hurting or injuring other people?”). Research in clinical and nonclinical populations has demonstrated associations between the frequency of aggressive script rehearsal and aggression (Daff et al., 2014; Gilbert et al., 2013; Grisso et al., 2000; Nagtegaal et al., 2006; Podubinski et al., 2017).

4. THE PRESENT STUDY

The aim of this study is to examine associations between aggressive script rehearsal, rumination, and angry rumination in adult male incarcerated offenders using extant measurement instruments. Fantasy is not included since we regard “fantasy” (not the process of fantasizing, which is comparable to rumination, although more typically associated with positive rather than negative emotions) and “script” as interchangeable (Gilbert & Daffern, 2017). Further, this study aims to examine how rumination, anger rumination, and aggressive script rehearsal relate to aggression. Based upon a review of the questions incorporated in extant measurement instruments that are used to measure aggression‐related scripts, rumination (PTQ), and angry rumination (ARS, Sukhodolsky et al., 2001), we hypothesized (H1) that aggressive script rehearsal, rumination, and angry rumination would be positively associated but that the strongest association would exist between aggressive script rehearsal and anger rumination since these measures incorporate aggressive content. The ARS Thoughts of Revenge subscale was expected to be more strongly associated with aggressive script rehearsal than other ARS subscales because this subscale includes questions about planned (retaliatory) aggressive behavior.

It was also hypothesized (H2) that aggressive script rehearsal, rumination, and anger rumination would be positively associated with aggression, with the strongest associations being between aggression and aggressive script rehearsal and the ARS Thoughts of Revenge subscale, because these scales focus on aggressive content. It was also hypothesized (H3) that more frequent aggressive script rehearsal would be associated with aggressive behavior even after controlling for age (since age is inversely associated with the frequency of aggressive script rehearsal; Hosie et al., 2021), rumination, and anger rumination. Finally, it was hypothesized (H4) that aggressive script rehearsal would mediate the relationship between rumination/anger rumination and aggressive behavior when controlling for age. This is because rumination and anger rumination are only related to violence if they are followed by retaliatory thoughts (i.e., aggressive scripts), consistent with Sukhodolsky et al. (2001) who posit retaliatory thoughts occur only following some episodes of anger rumination.

5. METHOD

5.1. Participants

Participants were drawn from a sample of 145 male inmates aged between 18 and 62 years (Mage = 33.54, SD = 8.67) who were recruited from a high‐security correctional facility in Melbourne, Australia. Data from 12 participants were excluded due to incomplete questionnaire data and four additional participants were excluded as they were identified as “faking good” (a score greater than 12) according to their results on the Paulhus Deception Scale—Impression Management (PDS‐IM, Paulhus, 1999) subscale. The final sample comprised 129 participants. Most of these 129 participants identified as Australian (not including those identifying as Aboriginal Australian) (69.0%), with 10.9% identifying as Australian Aboriginal, Southern European (3.9%), New Zealand (2.3%), Melanesian/Polynesian (2.3%), and “other” (11.6%).

6. PROCEDURE

Participants were informed about the study at new inmate orientation meetings. Inmates who expressed interest in participation were given an explanatory statement outlining the purpose and nature of the study. Those inmates who were willing to participate then attended a meeting with JH where surveys were completed in groups of up to 10.

7. MATERIALS

7.1. Life History of Aggression‐Self‐Report‐Aggression Scale (LHA‐S‐A, Coccaro et al., 1997)

The LHA (Coccaro et al., 1997), is a structured interview schedule that assesses the frequency of aggressive acts a person has engaged in since adolescence. It consists of three subscales, including Aggression (LHA‐A; which measures overt displays of aggressive behavior), Consequences and Antisocial Behaviour (LHA‐C; which measures the extent to which the person has experienced significant social consequences due to aggressive behaviors and/or engaged in antisocial behaviors), and Self‐Directed Aggression (LHA‐S; which measures aggression directed toward the self). The five‐item self‐report version of the LHA‐A (i.e., LHA‐S‐A), was used in this study to measure the number of overt aggressive acts (i.e., verbal, indirect, nonspecific fighting, physical assault, and temper tantrums) that participants had engaged in since age 13. For this measure participants responded on a six‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 “never happened” to 5 “happened so many times that I couldn't give a number,” with higher scores reflecting greater engagement in aggressive acts over the lifetime. The LHA‐A has good internal consistency (α = 0.87), test–retest reliability (r = 0.80), and construct validity (r = 0.69) (Coccaro et al., 1997).

7.2. SIV (Grisso et al., 2000)

The SIV was designed to examine the prevalence of “violent thoughts” and their relationship to subsequent violent acts amongst people discharged from mental health units (MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study; Steadman, et al., 1998). Only the frequency item of the SIV (“How often do you have thoughts about hurting or injuring other people?”) was used for this study. Participants were required to rate their responses on a seven‐point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “several times a day.” This question has been used by numerous authors to measure the frequency of aggressive script rehearsal (Daff et al., 2014; Gilbert et al., 2013; Podubinski et al., 2017).

7.3. The PTQ (Ehring et al., 2011)

The PTQ is a 15‐item self‐report measure of repetitive negative thinking (RNT). Factor analyses suggest three lower‐order RNT factors, including (1) core features (e.g., “thoughts intrude into my mind”), (2) unproductiveness (e.g., “My thoughts are not much help to me”), and (3) mental capacity (e.g., “My thoughts take up all my attention”) (Ehring et al., 2011). Participants are required to rate how they typically think about negative experiences or problems using a five‐point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “almost always.” The full scale of the PTQ has good internal consistency (α = 0.94–0.95), as have the subscales: core characteristics (α = 0.92–0.94), unproductiveness (α = 0.77–0.87), and mental capacity (α = 0.82–0.90) (Ehring et al., 2011). The PTQ has shown good convergent validity with the Response Style Questionnaire (Nolen‐Hoeksema, 1991), the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (Meyer et al., 1990), and the Rumination Scale (McIntosh et al., 1995).

7.4. ARS (Sukhodolsky et al., 2001)

The ARS is a 19‐item self‐report measure of an individual's tendency to focus attention on angry moods, recall prior experiences of anger, and think about the causes and consequences of anger episodes. The measure comprises four factors, including (1) angry afterthoughts (e.g., “after an argument is over I keep fighting with this person in my imagination,” (2) thoughts of revenge (e.g., “I have difficulty forgiving people who have hurt me”), (3) angry memories (e.g., “I ponder the injustices that have been done to me”), and (4) understanding of causes (e.g., “I analyze the events that make me angry”). Participants are required to rate their responses on a four‐point scale ranging from “almost never” to “almost always.” The ARS full scale (α = 0.93) and subscales (α range = 0.72 [thoughts of revenge] to 0.86 [angry afterthoughts]) have demonstrated good test–retest reliability. Convergent and discriminant validity have been established (Sukhodolsky et al., 2001).

7.5. PDS‐IM subscale (Paulhus, 1999)

The PDS‐IM subscale is a 20‐item questionnaire that assesses socially desirable responding and was used in this study to exclude participants with invalid responses. Invalid responses are indicated by either a score greater than 12 (i.e., “faking good,” responding as excessively socially desirable or favorable) or a score less than 1 (i.e., “faking bad', responding as less socially desirable or favorable than reality). The PDS‐IM has demonstrated good internal consistency in prisoner populations (α = 0.84) and good concurrent validity with similar measures of social desirability (r > 0.50) (Lanyon & Carle, 2007; Paulhus, 1999).

8. DATA ANALYSIS

Raw data were entered into SPSS version 25 by two independent researchers to form two equivalent datasets. These datasets were then compared against each other, and the original surveys amended for any human input errors. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 25 and Amos 25.0.0. In the entire data set of 5031 individual responses, only 0.0007% were missing. Little's missing completely at randon test results demonstrated that data was missing at random with no identifiable pattern (χ 2 = 159.16, degree of freedom (df = 156, p = 0.41). Accordingly, expectation‐maximization was used to impute missing variables (Little, 1988; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Data were tested for violation in assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity, homoscedasticity, and independence of residuals. No multicollinearity was identified between total scale scores for the PTQ, SIV, and ARQ (no correlation was above 0.60) (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Strong correlations were found between the sub‐scales and total score of the PTQ, and the subscales of the ARS with total ARS (see Table 1). As such, regression analyses were undertaken using the total scale scores rather than subscales. No univariate or multivariate outliers were found. Other assumptions were satisfactory.

Table 1.

Summary of intercorrelations, means, standard deviations, range and Cronbach's α coefficient of internal consistency for aggressive scripts, life history of aggression, age, rumination, and anger rumination

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Aggressive scripts | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2. Age | −0.26*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3. LHA | 0.44*** | −0.23** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4. PTQ total | 0.48*** | −0.02 | 0.24 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 5. PTQ core features | 0.48*** | −0.02 | 0.25** | 0.98*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 6. PTQ unproductiveness | 0.39*** | 0.05 | 0.22* | 0.89*** | 0.81*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 7. PTQ mental capacity | 0.43*** | −0.05 | 0.16 | 0.90*** | 0.81*** | 0.80*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. ARS total | 0.58*** | −0.12 | 0.34*** | 0.60*** | 0.62*** | 0.48*** | 0.50*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 9. ARS angry afterthoughts | 0.49*** | −0.06 | 0.28*** | 0.58*** | 0.59*** | 0.49*** | 0.48*** | 0.91*** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. ARS thoughts of revenge | 0.65*** | −0.22* | 0.35*** | 0.46*** | 0.47*** | 0.36*** | 0.38*** | 0.84*** | 0.71*** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. ARS angry memories | 0.50*** | −0.14 | 0.28*** | 0.53*** | 0.53*** | 0.41*** | 0.46*** | 0.88*** | 0.71*** | 0.66*** | 1.00 | |

| 12. ARS understanding causes | 0.37*** | 0.00 | 0.27*** | 0.47*** | 0.50*** | 0.36*** | 0.38*** | 0.81*** | 0.65*** | 0.55*** | 0.66*** | 1.00 |

| M | 1.88 | 33.54 | 14.14 | 28.56 | 17.89 | 5.62 | 5.05 | 41.1 | 12.39 | 7.9 | 11.78 | 9.01 |

| SD | 1.91 | 8.7 | 6.78 | 14.01 | 8.69 | 2.98 | 3.19 | 11.54 | 4.16 | 3.04 | 3.37 | 2.76 |

| Range | 0.00–6.00 | 18.00–62.00 | 0.00–25.00 | 0.00–60.00 | 0.00–36.00 | 0.00–12.00 | 0.00–12.00 | 21.00–76.00 | 6.00–24.00 | 4.00–16.00 | 5.00–25.00 | 4.00–16.00 |

| ‐ | ‐ | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.8 | 0.81 | 0.75 |

Abbreviations: ARS, Anger Rumination Scale; LHA, Life History of Aggression; PTQ, Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Pearson's correlations were run to examine associations between rumination, anger rumination, and aggressive script rehearsal, and a four‐step sequential multiple regression was performed to assess for the unique contribution of each variable to aggressive behavior. This enabled the regression to control for age as a covariate (since age is inversely associated with aggression) and to enter the frequency of aggressive script rehearsal as the final variable to determine the contribution of aggressive script rehearsal to an aggressive behavior after allowing for rumination and anger rumination. Entering rumination (PTQ) in the second step permitted exploration of the relationship between general rumination and aggression, with subsequent steps determining whether these general processes were important when aggression‐specific content was also considered. The results of the multiple regression were more clearly conceptualized using Structural equation modeling with IBM AMOS version 25 software, thus enabling mediating effects of aggressive script rehearsal on aggressive behavior to be tested with consideration for error and testing for the goodness of fit. Sobel test (Soper, 2019) was used to test whether the indirect effect of general rumination (PTQ) and anger rumination (ARS) on aggression (LHA) through aggressive script rehearsal was significant. This test enabled mediation to be observed by dividing the indirect effects estimate by the standard error, which was then compared to a standard normal distribution.

9. RESULTS

Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and bivariate correlations are displayed in Table 1. Rumination, anger rumination, and aggressive script rehearsal were positively correlated with the strongest correlation being the significant, strong, positive correlation between aggressive script rehearsal and anger rumination (ARS) Thoughts of Revenge subscale. Aggressive script rehearsal and anger rumination (ARS total) had moderate positive correlations with LHA; however, there was only a weak nonsignificant correlation between general rumination (PTQ total) and LHA.

Table 2 displays the unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients (B, β), and the R 2, semi partial ΔR², and F values at each step of the sequential multiple regression. R was significantly different from 0 at the end of each step. In Model 2 a significant relationship between general rumination and aggression was found, however, in Model 3 the addition of anger rumination diluted that relationship, revealing a weak positive relationship between anger rumination and aggression. In Model 4, with all predictors in the model, at 99% confidence, the R 2 revealed that 22% of the variability in aggression history was predicted by age, rumination, anger rumination, and aggressive script rehearsal. In the final model, aggressive script rehearsal significantly and uniquely contributed to change in aggressive behavior, while age, rumination, and anger rumination were no longer significant predictors.

Table 2.

Multiple regression of LHA on predictor variables

| Life history of aggression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| Variable | B | β | B | β | B | β | B | β |

| Constant | 20.22** | 16.88** | 11.73** | 12.12** | ||||

| Age | −1.8** | −0.23 | −0.18** | −0.23 | −0.16* | −0.20 | −0.1 | −0.13 |

| PTQ | 0.11** | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ARS | 0.16** | 0.27 | 0.08 | 1.30 | ||||

| Agg script | 1.17** | 0.33 | ||||||

| R² | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.22 | ||||

| Change in R² | ||||||||

| df | 127 | 126 | 125 | 124 | ||||

| F(1,df) | 7.26** | 7.78** | 7.05** | 10.26** | ||||

| ΔR² | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||||

Note: N = 129.

Abbreviations: ARS, Anger Rumination Scale; LHA, Life History of Aggression; PTQ, Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

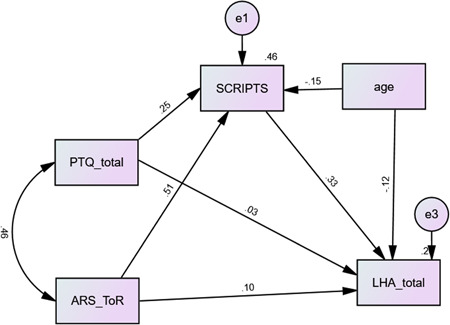

Table 3 Path modelling, using Amos (version 25), assessed whether the relationships between rumination (PTQ) and anger rumination (ARS) with aggression (LHA) was mediated by aggressive scripts rehearsal when controlling for the effects of age (see Figure 1). The model had good fit, with 129 participants χ 2 = 2.44, df = 2, minimum discrepancy per degree of freedom = 1.22, p = 0.30, root mean squared error approximation = 0.041, Tucker‐Lewis index = 0.99, comparative fit index = 0.99, adjusted goodness‐of‐fit index = 0.94. There were significant indirect effects found for both anger rumination (ARS) (η 2 = 0.14) and general rumination (PTQ) (0.07), as predictors of aggression (LHA) with the frequency of aggressive scripts rehearsal (SIV) as the mediator. Anger rumination (ARS) through aggressive script rehearsal to aggression (LHA), Sobel (2.73, two tailed), identified a significant indirect effect (z = 2.73, p = 0.006). Similarly, general rumination (PTQ) through aggressive script rehearsal to aggression (LHA) also identified a significant indirect effect (z = 1.98, p = 0.047).

Table 3.

Rumination and angry rumination thoughts of revenge

| Age | PTQ total | ARS TOR | SIV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std Reg Coeff | ||||

| SIV | −0.15* | 0.25*** | 0.51*** | ‐ |

| LHA | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.33** |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| LHA | (−0.12, −0.01)** | (0.02, 16)*** | (0.06, 32)** | |

| Direct effects | ||||

| LHA | (−0.28, −0.04)** | (−0.15, 21)** | (−0.12, 34)** | |

| Total effects | ||||

| LHA | (−0.32, −0.01)* | (−0.07, 30) | (−0.12, 34)*** | |

Abbreviations: LHA, Life History of Aggression; SIV, Schedule of Imagined Violence; Std Reg Coeff, Standized values for Regression Coefficients.

p = 0.05

p = 0.01

p = 0.001.

Figure 1.

Path model illustrating the mediation of aggressive scripts on the relationship between rumination and anger rumination onto aggressive behavior. Values represent standardized coefficients

10. DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between aggressive script rehearsal, rumination, anger rumination, and aggressive behavior. Results revealed a strong positive association between aggressive script rehearsal and anger rumination, as measured by the ARS, with the strongest correlation being between aggressive script rehearsal and the ARS Thoughts of Revenge subscale. This subscale assesses the retaliatory plans that arise within the context of provocation‐focused rumination; these plans correspond with some aggressive scripts (though not those that do not occur within the context of provocation and anger arousal). Consistent with previous research (Daff et al., 2014; Gilbert et al., 2013; Hosie et al., 2014) and as hypothesized, moderate positive correlations were found between aggressive script rehearsal and aggressive behavior, as well as between anger rumination and aggressive behavior. A weak positive correlation was also found between general rumination and aggressive behavior. In combination, these results suggest that it is the plans to act violently (i.e., cognitive scripts), whether these occur within the context of anger rumination or not, 1 that is most strongly associated with aggressive behavior. Regression analyses showed that aggressive script rehearsal was the only variable to demonstrate a unique relationship with aggression history and path analysis further demonstrated that aggressive script rehearsal mediated the relationship between rumination/anger rumination and aggression. These findings have ramifications for risk assessment and violent offender treatment that will be explored below.

11. STUDY STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

There are several strengths to this study, including the concurrent administration of multiple extant measures of conceptually related constructs to determine the inter‐relationship between these constructs but also their relationship with aggression. Many studies of these constructs have been conducted using nonclinical populations. Since this study was conducted in a clinical (inmate) sample, the results are more readily generalizable and potentially useful for forensic practitioners. Nevertheless, one limitation was the cross‐sectional and retrospective nature of the study, which does not permit assessment of the temporal relationship between rumination, anger rumination, aggressive script rehearsal, and aggression. While directional hypotheses are proposed, these relationships require further testing using longitudinal data. Furthermore, the self‐report design introduces common method variance that may have inflated associations between constructs. This should be considered when interpreting the results. A related limitation was that the data collected was self‐reported and therefore potentially subjective or biased. Attempts were made to minimize this limitation by excluding participants with invalid responses, as assessed by the PDS‐IM (Paulhus, 1999). Limitations related to the use of a single, self‐report measure of aggressive behavior (LHA) could be overcome in future research by using official records of violent behavior. Prospective studies using multiple measurement methods, including self‐ and observer‐rated instruments and official (i.e., court or police data) as well as direct (self‐report) and indirect (simulated or experimental) measures of rumination, anger rumination, and aggressive script rehearsal may address some of the aforementioned limitations and deepen theoretical and practical understandings of the relationships between these variables and aggression and help determine optimal assessment methods for forensic practitioners. Finally, the study was limited in its sample size, and the sample, while diverse in terms of participants' ethnicity sample only included males. Future studies are encouraged to use larger and more diverse populations to increase the generalizability of the results.

12. IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

The strength of the relationship between aggressive script rehearsal and aggression, combined with path analysis revealing script rehearsal as a mediator in the relationship between rumination/anger rumination and aggression, suggests the assessment of aggressive script rehearsal is important for violence risk assessment. The frequency with which a person rehearses aggressive scripts impacts on the likelihood of aggressive behavior beyond that of both general and anger rumination, confirming aggressive script rehearsal as a unique and integral construct in theories of aggression and in violent offender risk assessment. Although other cognitions are important to aggressive behavior (e.g., beliefs about the legitimacy of aggressive behavior, maladaptive schema), scripts are often neglected in aggressive offender evaluations and violent offender treatment programs (Gilbert & Daffern, 2017). In terms of treatment, script rehearsal is an important treatment target, however, methods to address scripts are underdeveloped. Given the demonstrated overlap between script rehearsal and anger rumination, it may be that the established literature examining interventions targeting rumination and anger rumination may be usefully drawn upon to progress treatment work for violent offenders with a tendency towards rumination and script rehearsal (see Morrison et al., 2021).

This study advances our understanding of aggressive scripts and shows that the frequency of aggressive script rehearsal is a unique and important indicator of aggression propensity. It defines and differentiates aggressive scripts from aggressive fantasy, rumination, and angry rumination, clarifies conceptual overlap and shows that the tendency to perseverate over negative thoughts is not necessarily related to aggressive behavior; it is the rehearsal of aggressive scripts, that is related to aggression. From a practical perspective, this study has shown that rumination, anger rumination, and aggressive script rehearsal are related but can be parsed using extant measurement instruments and should encourage forensic practitioners and scholars to use these terms more precisely. Finally, it is noteworthy that there was, as hypothesized, a strong positive association between the frequency of aggressive script rehearsal and the ARS Thoughts of Revenge subscale. This subscale measures plans for revenge/retaliation. Although this association was strong and positive, it was imperfect, raising the possibility that aggressive script rehearsal may arise independent of anger arousal, consistent with Hosie et al. (2021); the functions and emotional correlates of aggressive script rehearsal, as well as the nature of the aggressive behavior that is rehearsed, requires greater scrutiny.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the Swinburne University Human Research Ethics Committee and the Victorian Department of Justice Human Research Ethics Committee (CF/13/19800) and the Swinburne University Human Research Ethics Committee (SHR Project 2014/078).

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/jclp.23341

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The first author received funding support from the Australian Government in the form of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and an Australian Postgraduate Award Scholarship. Open access publishing facilitated by Swinburne University of Technology, as part of the Wiley ‐ Swinburne University of Technology agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Hosie, J. , Simpson, K. , Dunne, A. , & Daffern, M. (2022). A study of the relationships between rumination, anger rumination, aggressive script rehearsal, and aggressive behavior in a sample of incarcerated adult males. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78, 1925–1939. 10.1002/jclp.23341

ENDNOTE

Not all aggressive scripts occur within the context of anger rumination; some scripts occur independent of provocation and angry emotions (Hosie et al., 2021), and function to upregulate or sustain a positive emotion, e.g., by planning a provocative violent assault in a predatory or appetitive manner (Ching et al., 2012).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Department of Justice Human Research Ethics Committee. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the author(s) with the permission of the Department of Justice Human Research Ethics Committee.

REFERENCES

- Akers, R. L. , & Jennings, W. G. (2015). Social learning theory, The handbook of criminological theory (Vol. 4, pp. 230–240). 10.1002/9781118512449.ch12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. A. , & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 27–51. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, D. A. , & Bonta, J. (2010). Punishment, The psychology of criminal conduct (5th ed., pp. 442–451). Lexis Nexis, Matthew Bender. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis, M. D. , Anestis, J. C. , Selby, E. A. , & Joiner, T. E. (2009). Anger rumination across forms of aggression. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(2), 192–196. 10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, L. (2012). A cognitive‐neoassociation theory of aggression. In Higgins E. T., Kruglanski A. W., & Lange P. A. M. V. (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 99–117). SAGE. 10.4135/9781446249222.n31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman, B. J. (2002). Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 724–731. 10.1177/0146167202289002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman, B. J. , Bonacci, A. M. , Pedersen, W. C. , Vasquez, E. A. , & Miller, N. (2005). Chewing on it can chew you up: Effects of rumination on triggered displaced aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 969–983. 10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching, H. , Daffern, M. , & Thomas, S. D. M. (2012). Appetitive violence: A new phenomenon? Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 19(5), 745–763. 10.1080/13218719.2011.623338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccaro, E. F. , Berman, M. E. , & Kavoussi, R. J. (1997). Assessment of life‐history of aggression: Development and psychometric characteristics. Psychiatry Research, 73(3), 147–157. 10.1016/S0165-1781(97)00119-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daff, E. S. , Gilbert, F. , & Daffern, M. (2014). The relationship between anger and aggressive script rehearsal in an offender population. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 22(5), 731–739. 10.1080/13218719.2014.986837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denson, T. F. (2013). The multiple systems model of angry rumination. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(2), 103–123. 10.1177/1088868312467086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall, C. N. , Baumeister, R. F. , Stillman, T. F. , & Gailliot, M. T. (2007). Violence restrained: Effects of self‐regulation and its depletion on aggression. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(1), 62–76. 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring, T. , Zetsche, U. , Weidacker, K. , Wahl, K. , Schönfeld, S. , & Ehlers, A. (2011). The Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ): Validation of a content‐independent measure of repetitive negative thinking. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 42(2), 225–232. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, F. , & Daffern, M. (2017). Aggressive scripts, violent fantasy and violent behavior: A conceptual clarification and review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 36, 98–107. 10.1016/j.avb.2017.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, F. , & Daffern, M . (2010). Integrating contemporary aggression theory with violent offender treatment: How thoroughly do interventions target violent behavior? Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 15(3), 167–180. 10.1016/j.avb.2009.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, F. , Daffern, M. , Talevski, D. , & Ogloff, J. (2013). The role of aggression‐related cognition in the aggressive behavior of offenders: A general aggression model perspective. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(2), 119–138. 10.1177/0093854812467943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grisso, T. , Davis, J. , Vesselinov, R. , Appelbaum, P. S. , & Monahan, J. (2000). Violent thoughts and violent behavior following hospitalization for mental disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 388–398. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie, J. , Dunne, A. , Simpson, K. , & Daffern, M. (2021). Aggressive scripts rehearsal in adult offenders: Relationships with emotion regulation difficulties and aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 48(1), 5–16. 10.1002/ab.22000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie, J. , Gilbert, F. , Simpson, K. , & Daffern, M. (2014). An examination of the relationship between personality and aggression using the general aggression and five factor models. Aggressive Behavior, 40(2), 189–196. 10.1002/ab.21510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann, L. R. (1988). An information processing model for the development of aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 14(1), 13–24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann, L. R. (1998). The role of social information processing and cognitive schema in the acquisition and maintenance of habitual aggressive behavior. In Geen R. G., & E. Donnerstein (Eds.), Human aggression: Theories, research, and implications for social policy (pp. 73–109). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann, L. R. , & Eron, L. D. (1989). Individual differences and the trait of aggression. European Journal of Personality, 3, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon, R. I. , & Carle, A. C. (2007). Internal and external validity of scores on the balanced inventory of desirable responding and the Paulhus deception scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 67(5), 859–876. 10.1177/0013164406299104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J. , Moores, E. , & Chow, C. (2007). Anger rumination and self‐reported aggression amongst British and Hong Kong Chinese athletes: A cross cultural comparison. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5(1), 9–27. 10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671810 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, W. D. , Harlow, T. F. , & Martin, L. L. (1995). Linkers and nonlinkers: Goal beliefs as a moderator of the effects of everyday hassles on rumination, depression, and physical complaints 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(14), 1231–1244. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb02616.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, K. A. , Aldao, A. , Wisco, B. E. , & Hilt, L. M. (2014). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor underlying transitions between internalizing symptoms and aggressive behavior in early adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(1), 13–23. 10.1037/a0035358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, K. A. , & Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (2011). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 186–193. 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T. J. , Miller, M. L. , Metzger, R. L. , & Borkovec, T. D. (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495. 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael, T. , Halligan, S. L. , Clark, D. M. , & Ehlers, A. (2007). Rumination in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 24(5), 307–317. 10.1002/da.20228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, F. P. , Fullam, R. , Thomson, K. , & Daffern, M. (2021). Enhancing psychological treatment for violent offenders: A review of treatment approaches to target aggressive script rehearsal. Manuscript under review.

- Nagtegaal, M. H. , Rassin, E. , & Muris, P. (2006). Aggressive fantasies, thought control strategies, and their connection to aggressive behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 1397–1407. 10.1037/t10046-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen‐Hoeksema, S. , Wisco, B. E. , & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D. L. (1999). Paulhus deception scales: User manual. Multi‐Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, W. C. , Denson, T. F. , Goss, R. J. , Vasquez, E. A. , Kelly, N. J. , & Miller, N. (2011). The impact of rumination on aggressive thoughts, feelings, arousal, and behavior. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50, 281–301. 10.1348/014466610X515696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled, M. , & Moretti, M. M. (2010). Ruminating on rumination: Are rumination on anger and sadness differentially related to aggression and depressed mood? Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(1), 108–117. 10.1007/s10862-009-9136-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podubinski, T. , Lee, S. , Hollander, Y. , & Daffern, M. (2017). Patient characteristics associated with aggression in mental health units. Psychiatry Research, 250, 141–145. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokach, A. (1990). Content analysis of sexual fantasies of males and females. The Journal of Psychology, 124(4), 427–436. 10.1080/00223980.1990.10543238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, K. , & Patel, G. (2009). Fantasies of a dangerous and severe personality disordered clinical forensic population: An exploratory study. Proceedings of the 6th European Congress on Violence in Clinical Psychiatry. https://www.oudconsultancy.nl/-Resources/Proceedings_6th_Violence_in_Clinical_Psychiatry_2009.pdf

- Smith, C. E. , Fischer, K. W. , & Watson, M. W. (2009). Toward a refined view of aggressive fantasy as a risk factor for aggression: Interaction effects involving cognitive and situational variables. Aggressive Behavior, 35(4), 313–323. 10.1002/ab.20307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. D. , Stephens, H. F. , Repper, K. , & Kistner, J. A. (2016). The relationship between anger rumination and aggression in typically developing children and high‐risk adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(4), 515–527. 10.1007/s10862-016-9542-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soper, D. (2019). Free Statistics Calculators ‐ Home. Danielsoper.com. https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/default.aspx

- Steadman, H. J. , Mulvey, E. P. , Monahan, J. , Robbins, P. , Appelbaum, P. , & Grisso, T. (1998). Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky, D. G. , Golub, A. , & Cromwell, E. N. (2001). Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(5), 689–700. 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00171-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B. G. , & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.‐ International edition). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, J. T. , & Felson, R. B. (1994). Violence, aggression, and coercive actions. American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10160-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez, E. A. , Osman, S. , & Wood, J. L. (2012). Rumination and the displacement of aggression in United Kingdom gang‐affiliated youth. Aggressive Behavior, 38(1), 89–97. 10.1002/ab.20419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Department of Justice Human Research Ethics Committee. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the author(s) with the permission of the Department of Justice Human Research Ethics Committee.