Abstract

Background

The long‐term increase in survival from cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) is generally attributed to the decreasing trend in tumour thickness, the single most important prognostic factor.

Objectives

To determine the relative contribution of decreased tumour thickness to the favourable trend in survival from CMM in Italy.

Methods

Eleven local cancer registries covering a population of 8 056 608 (13.4% of the Italian population in 2010) provided records for people with primary CMM registered between 2003 and 2017. Age‐standardized 5‐year net survival was calculated. Multivariate analysis of 5‐year net survival was undertaken by calculating the relative excess risk (RER) of death. The relative contribution of the decrease in tumour thickness to the RER of death was evaluated using a forward stepwise flexible parametric survival model including the available prognostic factors.

Results

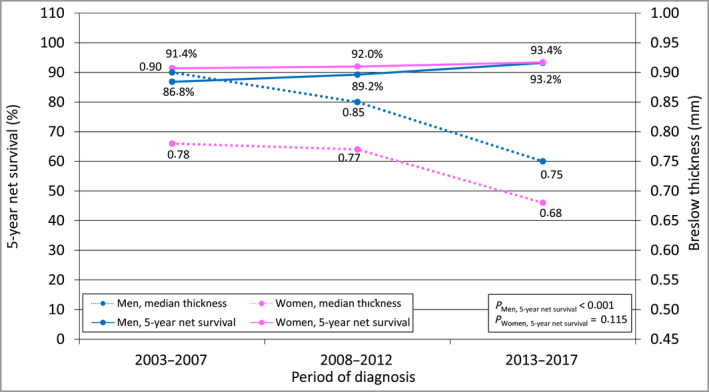

Over the study period, tumour thickness was inversely associated with 5‐year net survival and multivariate RER in both sexes. The median thickness was 0.90 mm in 2003–2007, 0.85 mm in 2008–2012 and 0.75 mm in 2013–2017 among male patients, and 0.78 mm, 0.77 mm and 0.68 mm among female patients, respectively. The 5‐year net survival was 86.8%, 89.2% and 93.2% in male patients, and 91.4%, 92.0% and 93.4% in female patients, respectively. In 2013–2017, male patients exhibited the same survival as female patients despite having thicker lesions. For them, the increasing survival trend was more pronounced with increasing thickness, and the inclusion of thickness in the forward stepwise model made the RER in 2013–2017 vs. 2003–2007 increase from 0.64 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51–0.80] to 0.70 (95% CI 0.57–0.86). This indicates that the thickness trend accounted for less than 20% of the survival increase. For female patients, the results were not significant but, with multiple imputation of missing thickness values, the RER rose from 0.74 (95% CI 0.58–0.93) to 0.82 (95% CI 0.66–1.02) in 2013–2017.

Conclusions

For male patients in particular, decrease in tumour thickness accounted for a small part of the improvement in survival observed in 2013–2017. The introduction of targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors in 2013 is most likely to account for the remaining improvement.

What is already known about this topic?

Long‐term increase in survival from cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) is generally attributed to the decreasing trend in tumour thickness, the single most important prognostic factor.

Targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors, introduced during the past decade, were shown in phase III trials to improve the prognosis of patients with unresectable and metastatic CMM, but their contribution to the persistent upward trend in overall survival at the population level in Europe is ill‐defined.

What does this study add?

In Italy, the 5‐year net survival from CMM in 2013–2017 improved vs. 2003–2007, especially among male patients and in the two highest tumour thickness categories.

Male patients, for the first time, exhibited the same survival as female patients despite having still thicker lesions. The decrease in median tumour thickness accounted for a small part of the improvement.

Novel therapies, approved in 2013, are the factor most likely to account for the remaining improvement.

In Italy, the 5‐year net survival from melanoma in 2013–2017 improved vs. 2003–2007, especially among male patients and in the two highest tumour thickness categories. Male patients, for the first time, exhibited the same survival as female patients despite having still thicker lesions. The decrease in median tumour thickness accounted for a small part of the improvement. Novel therapies, approved in 2013, are the factor most likely to account for the remaining improvement.

Linked Comment: I.T. Harvima and R.J. Harvima. Br J Dermatol 2022; 187:6–7.

Plain language summary available online

Since approximately the end of World War II, the incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma (CMM) has steeply increased in white populations all over the world. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 This has been the result of a critical change in sunbathing habits with more intermittent and intense ultraviolet radiation exposure 9 , 10 coupled with an increased use of artificial ultraviolet radiation‐emitting indoor tanning beds.

The incidence increase has been primarily driven by patients with early cases of CMM, defined as having a low Breslow tumour thickness. The incidence of thick CMM has also increased, but to a lesser extent. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 This pattern is compatible with the following three explanations, which are not mutually exclusive: increased public awareness of the signs of the disease, resulting in earlier detection; decreased biological aggressiveness of sun‐related CMM, which would be suggested by the positive association between the level of ultraviolet radiation exposure before diagnosis and survival from the disease; 16 , 17 and increased sensitivity of dermatological screening for early CMM, 18 possibly associated with a risk of overdiagnosis. 18 , 19

Whatever its cause, the tumour‐thickness‐specific incidence trends have been generally paralleled by an increase in survival. 20 , 21 As a low tumour thickness is the single major prognostic factor for the outcome of patients with CMM, 22 the most important epidemiological studies have related the upward survival trend to the rise in incidence of thin lesions. 23 , 24

This temporal correlation, however, is not necessarily evidence for a causal and exclusive link. According to studies from Germany 25 and Australia, 26 the increase in survival occurring in the last two decades of the last century was only partially attributable to early detection. 25 More recent data from the USA have shown a survival improvement in all tumour stage categories, 13 including thick and metastatic disease and, thus, independently of changes in tumour thickness. 27 This is interpreted as the result of the introduction of molecular targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors during the past decade. 28

In view of their potential implications on policies for secondary prevention and treatment of CMM on a public health scale, these important observations need to be confirmed in other populations. We report a multicentre cancer registry‐based study exploring in a formal fashion the relationship between the trend in tumour‐thickness‐specific incidence and the trend in survival from CMM in Italy.

Materials and methods

Rationale and objectives

Over the past three decades, the incidence of CMM in Italy has constantly increased. 29 Several local studies have already suggested that this trend has been more pronounced for thin CMM. 30 , 31 As found elsewhere, the reduction in tumour thickness has been accompanied by a consistent increase in 5‐year survival rates. 32

The present study was designed to gain a better understanding of the relationship between these parallel trends. The primary objective was to quantify the relative role that the lowering of tumour thickness has played in the favourable survival trend in the Italian adult population (age ≥ 15 years). In order to corroborate the study rationale, we identified all significant prognostic factors among the available registration variables, we assessed their time trends, and we studied in detail the trend in survival.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Romagna Cancer Institute (ID: IRST100.37; IRST identifier codes: L1P1572, wfn.75L1).

Source of data

The data for the study were extracted from the database of the Italian Association of Cancer Registries (AIRTUM) using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, codes C43.0 to C43.9. 33 Although not included in the standard registration items 34 nor reported in routine statistical publications, 35 tumour thickness has been regularly recorded for many years by several Italian registries.

Sixteen cancer registries with available tumour thickness information authorized the use of their records. Their data, pooled together, covered the years 1989–2017. The analysis was restricted to the registries that have been operating for ≥ 10 consecutive years with an annual proportion of cases with missing tumour thickness information ≤ 25%. Eleven registries, with a core registration period of 15 years, met these criteria. On 1 January 2010, they covered a total population of 8 056 608 (13.4% of the Italian population). The population aged ≥ 15 years was 6 904 734.

Case series

The participating registries contributed a total of 17 707 cases of CMM to the study. Among these there were 26 death‐certificate‐only (DCO) cases (a proportion of 0.15%, a measure of incompleteness of cancer registration). DCO cases as well as cases registered based on an autopsy report and those with no follow‐up data (n = 33) were excluded leaving 17 674 cases eligible for analysis. Table S1 (see Supporting Information) shows details of each participating registry.

The 17 674 eligible CMM cases were from 9108 male patients (51.5%) and 8566 female patients (48.5%). The number that could be categorized by tumour thickness according to the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria 36 was 8246 and 7884, respectively, with a total of 16 130 (91.3%).

Tumour thickness categorization

In accordance with the above mentioned AJCC staging criteria, 36 tumour thickness was categorized as < 0.8, 0.8–1.0, > 1.0–2.0, > 2.0‐4.0 and > 4.0 mm. In general, thin CMM is defined as having a thickness ≤ 1.0 mm. 11 , 14 , 15 , 37 In accordance with the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology – 3rd edition, 1st revision, 24 histological subtype was categorized as superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, lentigo maligna melanoma, or other.

Statistical methods

We estimated 5‐year net survival using the Pohar–Perme estimator. 38 The estimates of 5‐year net survival, obtained with the strs Stata command and based on a traditional cohort (or complete) approach, 39 were age‐standardized with the International Cancer Survival Standard‐2 weights. 40 Patients were followed‐up until 31 December 2018. To correct for the background mortality, we constructed registry‐specific life tables.

To assess the trends in the incidence of CMM according to their prognostic features, the average annual per cent change was estimated (EAAPC). For this purpose, a generalized linear regression model for the natural logarithm of the age‐standardized incidence rates, with calendar year as a regressor variable, was fitted.

To assess the statistical significance of the trend in 5‐year net survival, a Poisson regression model for net survival including the period of diagnosis as a continuous regressor was used. Specifically, the statistical significance was assessed with the Wald test for trend [P‐value and the 95% confidence interval (CI)] in the exponential of the period of diagnosis coefficient.

Multivariate analysis of 5‐year net survival was undertaken by calculating the relative excess risk (RER) of death. 41 A flexible parametric survival model using restricted cubic splines (five degrees of freedom for male patients and six for female patients) was fitted on the log cumulative excess hazard scale. 42 Flexible parametric models for net survival were fitted on individual‐level data by using the stpm2 Stata command. 43

The study period was divided into time periods of equal length. In order to increase the robustness of results, three 5‐year periods (2003–2007, 2008–2012, 2013–2017) were preferred to five 3‐year periods. To determine the relative contribution of the decrease in tumour thickness to survival improvement, the years 2003–2007 were used as a reference period. A forward stepwise selection method was used to add variables to the model, with the statistical significance of each predictor being determined by the log‐likelihood ratio test for nested models with a P‐value less than 0.05.

To deal with the problem of participants with CMM where there was missing tumour thickness information, a sensitivity analysis of the multivariate RER of death by time period of diagnosis was performed. Two different methods were used: classifying tumour thickness according to the five AJCC categories plus a category for missing values and performing the multiple imputation of missing values under the ‘missing at random’ assumption. 44 Ten imputations were performed. The variables used included patient age, sex, time period of diagnosis, basis of diagnosis, vital status, histological subtype, tumour subsite and follow‐up time. The statistical significance of age at diagnosis, histological subtype and tumour subsite was determined with the log‐likelihood ratio test for nested models. For tumour thickness, the Wald test was used. 45 Further details are provided in the footnotes to Table S2 (male patients) and Table S3 (female patients) in the Supporting Information.

The cases of the 16 130 patients that could be classified into the five AJCC tumour thickness categories formed the basis for the identification of prognostic factors, the evaluation of time trend in incidence by prognostic characteristics, the evaluation of time trend in 5‐year net survival and the stepwise multivariate analysis of survival. The total series of cases from 17 674 patients was used for the sensitivity analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed by using the Stata statistical package, Release 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Among the cases from the 16 130 patients with available tumour thickness information, the median patient age was 62 years for the 8246 male patients and 55 years for the 7884 female patients. Nearly half of these were diagnosed with a CMM ≤0.8 mm thick (male patients, 46.2%; female patients, 52.0%), and a comparable proportion presented with a superficial spreading melanoma (male patients, 45.9%; female patients, 49.3%).

Prognostic factors

Significant prognostic factors for 5‐year net survival were identified for the study period as a whole. Table 1 shows the association of patient age and disease characteristics with 5‐year net survival by sex. The strong inverse prognostic value of tumour thickness was confirmed both for male and female patients. Five‐year net survival decreased markedly with increasing patient age. There also was significant heterogeneity in survival between histological subtypes and, for male patients, between tumour subsites. Over the whole study period, female patients survived longer than male patients, with a 5‐year net survival of 92.2% (95% CI 91.3–93.1%) vs. 89.7% (95% CI 88.7–90.7%) (Wald test, P < 0.001) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Number of patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma and 5‐year per cent net survival by patient age, tumour thickness, histological subtype and tumour subsite, by sex, Italy, 2003–2017

| Male patients | Female patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | % net survival (95% CI) | P‐value | n (%) | % net survival (95% CI) | P‐value | |

| Age at diagnosis, yearsa | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 15–44 | 1597 (19.4) | 93.5 (92.2–94.8) | 2372 (30.1) | 96.7 (95.9–97.5) | ||

| 45–64 | 2973 (36.1) | 91.4 (90.1–92.7) | 2735 (34.7) | 95.0 (94.0–96.0) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 3676 (44.6) | 83.9 (81.4–86.5) | 2777 (35.2) | 83.9 (81.2–86.8) | ||

| Thickness (mm) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 0.8 | 3812 (46.2) | 102.2 (101.1–103.3) | 4096 (52.0) | 102.5 (101.5–103.5) | ||

| 0.8–1.0 | 853 (10.3) | 99.9 (97.3–102.5) | 915 (11.6) | 100.3 (98.0–102.7) | ||

| > 1.0–2.0 | 1345 (16.3) | 91.7 (89.3–94.2) | 1240 (15.7) | 93.1 (90.8–95.5) | ||

| > 2.0–4.0 | 1197 (14.5) | 72.7 (69.5–76.1) | 873 (11.1) | 77.2 (73.8–80.8) | ||

| > 4.0 | 1039 (12.6) | 51.7 (47.5–56.3) | 760 (9.6) | 54.1 (49.0–59.9) | ||

| Histological subtype | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| SSM | 3782 (45.9) | 96.2 (94.9–97.6) | 3887 (49.3) | 96.9 (95.7–98.2) | ||

| NM | 1114 (13.5) | 68.5 (65.0–72.3) | 845 (10.7) | 73.3 (69.8–77.1) | ||

| LMM | 283 (3.4) | 100.7 (97.6–103.8) | 317 (4.0) | 101.4 (98.9–103.9) | ||

| Other subtypes | 2358 (28.6) | 87.0 (85.1–88.9) | 2232 (28.3) | 90.9 (89.2–92.7) | ||

| Melanoma NOS | 709 (8.6) | 94.2 (91.2–97.4) | 603 (7.6) | 93.4 (90.2–96.8) | ||

| Tumour subsite | < 0.001 | 0.293 | ||||

| Head and neck | 1157 (14.0) | 84.1 (80.9–87.4) | 870 (11.0) | 90.2 (87.3–93.2) | ||

| Trunk | 4142 (50.2) | 90.5 (89.1–91.9) | 2310 (29.3) | 92.1 (90.2–94.0) | ||

| Upper limb | 1516 (18.4) | 91.2 (88.9–93.6) | 1446 (18.3) | 93.7 (91.7–95.6) | ||

| Lower limb | 1173 (14.2) | 88.0 (85.3–90.6) | 2951 (37.4) | 92.3 (90.9–93.7) | ||

| Other | 258 (3.1) | 89.3 (83.9–95.0) | 307 (3.9) | 88.7 (83.5–94.2) | ||

CI, confidence interval; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; NM, nodular melanoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma. aFor age at diagnosis, the age‐specific 5‐year per cent net survival is shown. For the remaining variables, 5‐year net survival was age‐standardized using the International Cancer Survival Standard‐2 weights. 40 P‐values, from a Wald test for survival comparison, refer to the variable’s coefficient estimated by fitting a generalized linear model for net survival, with Poisson distribution, including the follow‐up time, the age at diagnosis and the covariate.

As shown in Table 2, multivariate analysis of 5‐year net survival based on the calculation of the RER of death, confirmed the prognostic significance of tumour thickness and patient age for both sexes. The survival gradient across tumour thickness categories was particularly pronounced.

Table 2.

Multivariate relative excess risk (RER) of death from cutaneous malignant melanoma by patient age, tumour thickness, histological subtype and tumour subsite, by sex, Italy, 2003–2017a

| Male patients | Female patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths, n (%) | RER (95% CI) | P‐value | Deaths, n (%) | RER (95% CI) | P‐value | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 15–44 | 99 (6.2) | 1.00 (ref) | 74 (3.1) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 45–64 | 301 (10.1) | 1.08 (0.84–1.39) | 156 (5.7) | 1.15 (0.84–1.57) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 1153 (31.4) | 1.47 (1.16–1.87) | 769 (27.7) | 1.88 (1.40–2.52) | ||

| Thickness (mm) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 0.8 | 239 (6.3) | 0.00 (0.00‐.) | 115 (2.8) | 0.00 (0.00‐.) | ||

| 0.8–1.0 | 79 (9.3) | 0.11 (0.03–0.50) | 36 (3.9) | 0.00 (0.00‐.) | ||

| > 1.0–2.0 | 219 (16.3) | 1.00 (ref) | 148 (11.9) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| > 2.0–4.0 | 435 (36.3) | 3.75 (2.81–4.99) | 269 (30.8) | 3.27 (2.36–4.53) | ||

| > 4.0 | 581 (55.9) | 8.20 (6.17–10.89) | 431 (56.7) | 8.59 (6.22–11.88) | ||

| Histological subtype | 0.643 | 0.530 | ||||

| SSM | 414 (10.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 260 (6.7) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| NM | 466 (41.8) | 0.91 (0.73–1.14) | 326 (38.6) | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) | ||

| LMM | 54 (19.1) | 0.26 (0.03–2.15) | 47 (14.8) | 0.49 (0.18–1.37) | ||

| Other subtypes | 519 (22.0) | 0.94 (0.75–1.17) | 304 (13.6) | 0.85 (0.66–1.11) | ||

| Melanoma NOS | 100 (14.1) | 0.84 (0.59–1.21) | 62 (10.3) | 0.81 (0.52–1.28) | ||

| Tumour subsite | 0.211 | 0.094 | ||||

| Head and neck | 343 (29.6) | 1.00 (ref) | 225 (25.9) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Trunk | 670 (16.2) | 0.88 (0.71–1.09) | 191 (8.3) | 1.08 (0.79–1.48) | ||

| Upper limb | 280 (18.5) | 0.79 (0.61–1.02) | 168 (11.6) | 0.81 (0.58–1.13) | ||

| Lower limb | 211 (18.0) | 0.74 (0.57–0.97) | 364 (12.3) | 0.80 (0.60–1.07) | ||

| Other | 49 (19.0) | 0.89 (0.55–1.44) | 51 (16.6) | 1.08 (0.68–1.73) | ||

CI, confidence interval; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; NM, nodular melanoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; ref, reference; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma. aThe RER of death is from a flexible parametric model for net survival with 5 degrees of freedom for male patients and 6 degrees of freedom for female patients. The number of degrees of freedom corresponds to the number of the model with the lowest Akaike information criterion. The numbers of deaths and the RER of death were calculated for 5 years since diagnosis. Estimates were performed adjusting for all the variables in the table and for the time period of diagnosis. P‐values are for the Wald test.

Time trend in incidence by prognostic characteristics

Table 3 shows that the age‐standardized incidence rate increased significantly over time for many prognostic categories of CMM, but with different increments. In particular, the EAAPC was greater for patients aged ≥ 45 years as well as for superficial spreading melanoma compared with the nodular subtype. The incidence increase was particularly remarkable among CMMs < 0.8 mm thick, the largest tumour thickness category. The EAAPC was less and less pronounced in the three intermediate categories, but rising again for the small subgroup of cases > 4.0 mm thick.

Table 3.

Average annual cutaneous malignant melanoma incidence rates per 100 000 persons and estimated average annual per cent change by patient age, tumour thickness, histological subtype and tumour subsite, by sex, Italy, 2003–2017a

| Male patients | Female patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASIR (95% CI) | EAAPC (95% CI) | ASIR (95% CI) | EAAPC (95% CI) | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||||

| 15–44 | 7.3 (6.9 to 7.7) | 3.4* (2.2 to 4.6) | 10.9 (10.5 to 11.4) | 2.5* (1.0 to 4.0) |

| 45–64 | 21.6 (20.8 to 22.4) | 5.0* (4.3 to 5.6) | 18.8 (18.1 to 19.5) | 4.7* (3.7 to 5.7) |

| ≥ 65 | 39.1 (37.9 to 40.4) | 5.7* (4.7 to 6.7) | 21.8 (21.0 to 22.6) | 4.1* (3.2 to 4.9) |

| Thickness, mm | ||||

| < 0.8 | 8.8 (8.5 to 9.0) | 7.3* (6.0 to 8.5) | 8.4 (8.2 to 8.7) | 5.1* (3.7 to 6.5) |

| 0.8–1.0 | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.1) | 4.5* (2.8 to 6.2) | 1.9 (1.8 to 2.0) | 3.0* (0.7 to 5.3) |

| > 1.0–2.0 | 3.1 (3.0 to 3.3) | 2.6* (1.4 to 3.9) | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.7) | 1.2* (0.3 to 2.2) |

| > 2.0–4.0 | 2.8 (2.7 to 3.0) | 2.3* (0.8 to 3.8) | 1.7 (1.6 to 1.8) | 1.5* (0.1 to 3.0) |

| > 4.0 | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.7) | 3.7* (2.5 to 5.0) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.5) | 3.8* (2.3 to 5.4) |

| Histological subtype | ||||

| SSM | 8.7 (8.4 to 9.0) | 3.5* (2.3 to 4.8) | 8.0 (7.8 to 8.3) | 2.3* (1.1 to 3.6) |

| NM | 2.7 (2.5 to 2.8) | 0.0 (–2.1 to 2.1) | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7) | –0.7 (–3.4 to 1.9) |

| LMM | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 1.5 (–2.9 to 5.8) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.6) | 2.1 (–1.7 to 5.9) |

| Other subtypes | 5.5 (5.3 to 5.8) | 9.0* (7.2 to 10.9) | 4.5 (4.3 to 4.7) | 8.1* (5.5 to 10.6) |

| Melanoma NOS | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.8) | 7.1* (5.1 to 9.1) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 4.9* (2.6 to 7.2) |

| Tumour subsite | ||||

| Head and neck | 2.8 (2.6 to 3.0) | 3.5* (2.1 to 5.0) | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7) | 0.3 (–1.5 to 2.1) |

| Trunk | 9.6 (9.3 to 9.9) | 6.0* (4.8 to 7.1) | 4.8 (4.6 to 5.0) | 5.6* (4.4 to 6.9) |

| Upper limb | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.7) | 4.6* (3.1 to 6.0) | 2.9 (2.8 to 3.1) | 3.4* (1.8 to 4.9) |

| Lower limb | 2.7 (2.5 to 2.9) | 3.7* (2.1 to 5.4) | 6.0 (5.8 to 6.2) | 3.1* (2.0 to 4.2) |

| Other | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 7.9* (2.6 to 13.3) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 8.6* (3.3 to 14.0) |

ASIR, age‐standardized incidence rate; CI, confidence interval; EAAPC, estimated average annual per cent change; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; NM, nodular melanoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma. aEstimated average annual per cent change is from a generalized linear model for the natural logarithm of the age‐standardized incidence rates with calendar year as a regressor variable. *Significantly different from zero at the alpha level of 0.05.

As illustrated in Figure 1, these different tumour‐thickness‐specific incidence trends led to an overall decrease in the median tumour thickness of incident CMM cases, which was steeper among cases in male patients. In 2013–2017, however, male patients still had a disadvantage in terms of tumour thickness distribution, even though the difference from that in female patients narrowed.

Figure 1.

Time trend in median Breslow tumour thickness of cutaneous malignant melanoma and in 5‐year per cent net survival from the disease, by sex, Italy, 2003–2017. Median tumour thickness was computed for those cases from patients for whom the numerical value of tumour thickness was found (n = 14 247). Five‐year net survival was computed for the ‘core subset’ of eligible patients (n = 16 130), that is, those whose case could be categorized according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging criteria. 36 Five‐year net survival was age‐standardized using the International Cancer Survival Standard‐2 weights. 40 P‐values for trend are from a Poisson regression model for net survival including the time period of diagnosis as a numeric variable. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Time trend in 5‐year net survival

Also shown in Figure 1, the time period of diagnosis was positively associated with 5‐year net survival. Three important aspects should be noted.

First, the increase in survival was not significant for female patients, because of their high baseline net survival, but the exponential of the period of diagnosis coefficient was 0.89, with a 95% CI 0.77–1.03, slightly over 1. Male patients experienced a more marked and significant improvement. Thanks to this, and despite the fact they were still diagnosed with lesions of higher median tumour thickness, male patients virtually reached, in 2013–2017, the same 5‐year net survival as female patients (93.2% vs. 93.4%).

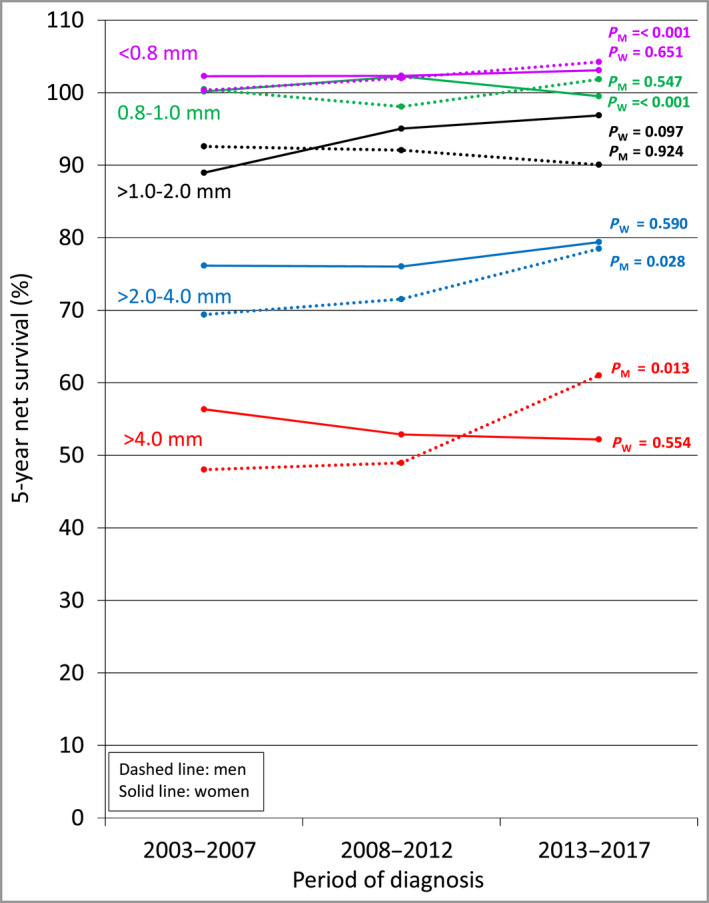

Second, as shown in Figure 2, the improvement in 5‐year net survival for male patients was more pronounced, both in absolute and relative terms, in the tumour thickness categories > 2.0–4.0 mm and > 4.0 mm. Regarding male patients, it is also worthy of note that for the most part the increase in survival occurred from 2013 onwards.

Figure 2.

Time trend in tumour thickness category‐specific 5‐year per cent net survival from cutaneous malignant melanoma, by sex, Italy, 2003–2017. Tumour thickness was categorized according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging criteria. 36 Five‐year net survival was computed for the ‘core subset’ of eligible patients (n = 16 130), that is, those whose case could be categorized according to the above criteria. P‐values for trend are from a Poisson regression model for net survival including the time period of diagnosis as a numeric variable. M, men; W, women. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

And third, this increase in survival occurred despite the fact that, among male patients, the median tumour thickness in the category of CMMs > 4.0 mm thick rose from 6.21 mm in 2008–2012 to 6.90 mm in 2013–2017 (data not shown).

Stepwise multivariate analysis of survival

The role of the decrease in tumour thickness in determining the improvement in survival is illustrated in Table 4. Female patients were retained in the analysis considering the P‐value and the 95% CI of the exponential of the period of diagnosis coefficient (0.77–1.03) (Figure 1). The years 2003–2007 were used as a reference period.

Table 4.

Multivariate relative excess risk (RER) of death from cutaneous malignant melanoma by time period of diagnosis, by sex, Italy, 2003–2017a

| Sex and model | LR test | P‐value | RER (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2007 | 2008–2012 | 2013–2017 | |||

| Male patients | |||||

| A, Time period | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.67–1.06) | 0.63 (0.48–0.82) | ||

| B, Model A plus patient age | B vs. A | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.67–1.02) | 0.59 (0.47–0.76) |

| C, Model B plus histological subtype | C vs. B | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) | 0.63 (0.50–0.79) |

| D, Model C plus tumour subsite | D vs. C | 0.031 | 1.00 | 0.82 (0.67–1.00) | 0.64 (0.51–0.80) |

| E, Model D plus tumour thickness | E vs. D | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.76–1.09) | 0.70 (0.57–0.86) |

| Female patients | |||||

| A, Time period | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.69–1.28) | 0.73 (0.50–1.06) | ||

| B, Model A plus patient age | B vs. A | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.71–1.21) | 0.72 (0.52–1.00) |

| C, Model B plus histological subtype | C vs. B | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.77–1.28) | 0.88 (0.65–1.19) |

| D, Model C plus tumour subsite | D vs. C | 0.026 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.75–1.25) | 0.87 (0.65–1.18) |

| E, Model D plus tumour thickness | E vs. D | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) | 0.91 (0.70–1.18) |

CI, confidence interval; LR, log‐likelihood ratio. aThe RER of death is from a flexible parametric model for net survival with 5 degrees of freedom for male patients and 6 degrees of freedom for female patients. The number of degrees of freedom corresponds to the number of the model with the lowest Akaike information criterion. P‐values are for the log‐likelihood ratio test comparing each model with the previous one.

In 2008–2012, male patients had a RER of death nonsignificantly lower than the unity at all steps of the model, although the RER increased from 0.82 to 0.91 when tumour thickness was entered. For the years 2013–2017, the baseline model including the period of diagnosis alone yielded an unadjusted RER of death as low as 0.63. With the simultaneous inclusion of patient age, histological subtype and tumour subsite as explanatory factors, the RER of death was virtually unchanged at 0.64. When entering tumour thickness into the model, the RER raised to 0.70. Thus, the decrease in tumour thickness was sufficient to explain a substantial part of the improvement observed in 2008–2012, while accounting for less than 20% of the improvement occurring in 2013–2017.

For female patients (Table 4), the pattern of RER of death was roughly similar, but their values were all higher. Both in 2008–2012 and 2013–2017, and at all steps of the model, the risk of death was nonsignificantly lower than in 2003–2007.

Stepwise multivariate analysis of survival: sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analysis of the multivariate RER of death the total series of cases from the 17 674 patients was used. The results are shown in Table S2 (male patients) and Table S3 (female patients, see Supporting Information). For male patients, both methods yielded results virtually equal to those of the basic analysis, in particular for the years 2013–2017. With respect to female patients, the RERs obtained after multiple imputation for the years 2013–2017, with an increased statistical power, were nearer to those obtained among male patients with the basic analysis (rose from 0.74, 95% CI 0.58–0.93, to 0.82, 95% CI 0.66–1.02), and had a borderline level of significance. This provided a post hoc confirmation that retaining female patients in the analysis was correct.

Discussion

The principal findings of this study can be summarized as follows. Firstly, we confirmed the strong prognostic significance of tumour thickness in Italian patients diagnosed with CMM in the past 20 years, we provided details of the time trend towards the diagnosis of thinner lesions and we documented the parallel trend towards improved survival. This supported the validity of the study rationale.

Secondly, we found that the decrease in tumour thickness among male patients explained largely the survival gain for patients diagnosed in 2008–2012 vs. those diagnosed in 2003–2007 but not the gain observed in 2013–2017. Both in the basic multivariate analysis (Table 4) and in the sensitivity analysis, the inclusion of tumour thickness in all three models caused the RER of death in the years 2013–2017 to increase from approximately 0.60 to 0.70. This means that the decrease in tumour thickness accounted for a smaller part of the survival improvement occurring in the period. The remaining component was because of another (or more than one) unmeasured correlate of the years 2013–2017 not included in the models.

Thirdly, given their better baseline data, the increasing time trend in survival among female patients did not reach a minimum standard level of significance. In 2013–2017, they had a minimally (nonsignificant) reduced risk of death. For patients diagnosed in this time period, however, the analysis of a dataset in which missing tumour thickness values were multiply imputed, thus increasing the statistical power, yielded a pattern of results comparable with that seen among male patients and with a borderline level of significance.

We believe that the interpretation of these results is straightforward. The marked survival gradient across tumour thickness categories confirmed the value of early detection of CMM, particularly among male patients. A persistent decrease in tumour thickness accounted for a part – albeit a lesser part – of the recent prognostic improvement, reflecting the high levels of sensitivity in CMM screening in Italy. 46 The potential benefit of early detection of the disease is well illustrated by the fact that male and female patients with thin CMM (i.e. < 0.8 mm and 0.8–1.0 mm thick), had a 5‐year net survival varying approximately between 100% and 102% (Table 1), that is, the same life expectancy as the general population or even a better one. This is equivalent to saying that they can be considered cured. 47

The great improvement in treatment strategies for CMM that have taken place in the past decade, with the approval of molecular targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors for unresectable and metastatic disease, 28 is the most likely factor accounting for the remaining – and greater – part of the survival gain achieved in 2013–2017. This is strongly suggested by two key considerations. Firstly, the two drugs that have changed substantially the way patients with advanced CMM are treated (i.e. ipilimumab and the targeted agent vemurafenib) were shown to improve survival in phase III trials of patients with metastatic CMM between 2010 and 2011 48 , 49 , 50 and were approved by the Italian Drug Agency in the first half of 2013. This is shown in Figure S1 (see Supporting Information). And, secondly, not only was the upward trend in survival more pronounced among male patients, but this trend was even more pronounced for lesions in the two highest tumour thickness categories. This is in accordance with findings from basic and clinical research. The biological trait underlying the historical survival disadvantage of male patients with CMM is most likely to be host‐related (with male patients having less resistance to progression) rather than tumour‐related (with male patients having more aggressive CMMs). 51 , 52 Consequently, men with CMM benefit from a larger overall survival increase when treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. 53 , 54 This explains the crucial finding that male patients, for the first time in Italy, exhibited virtually the same net survival as female patients despite still being diagnosed with thicker lesions.

The results and the conclusions of this study are consistent with those of a recent study from the USA reporting data from 34 population‐based cancer registries. 27 A pronounced improvement in short‐term survival has occurred among patients diagnosed with metastatic CMM during the past decade. The authors have attributed this progress to the US Food and Drug Administration approval of targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors.

With respect to Europe, the real‐world effectiveness of novel treatments has been assessed using single‐institution and multicentre hospital‐based CMM, or metastatic CMM, registries. 55 , 56 , 57 These studies have most often compared patients receiving novel treatments with patients undergoing conventional treatments. Except for the Netherlands and Denmark, where these institutions have nationwide coverage, the inclusion of all patients in hospital‐based registries is challenging and the registered case series may be biased. 58 This highlights the importance of a population‐based study like the present one. We used an intention‐to‐treat approach by considering the whole population of patients with CMM, whatever the extent to which they were actually and correctly treated.

This study also has limitations that need careful consideration. Firstly, cancer registration in Italy has been introduced irregularly both in time and space. The implications of, and the potential solutions to, this drawback are discussed in another article. 29 Restricting the analysis to a smaller number of registries with comparable time periods of registration, as we did in this study, is one of the most commonly used approaches. 59

Secondly, we had no information on ulceration – a known adverse prognostic indicator. The main prognostic role of this feature, however, is to subcategorize tumour thickness, which remains the key histopathological determinant of survival. 22 Also, ulceration is a marker of immunogenicity, and has been shown to be the key predictive marker of response to adjuvant interferon. 60 A comparable role in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors has been hypothesized. In a trial of patients with resected stage III CMM, ulceration predicted patients’ sensitivity to ipilimumab. 61 After long‐term follow‐up, however, this finding was not confirmed. 62

Thirdly, we were not able to take account of potential overdiagnosis. However, it is very unlikely that the prevalence of overdiagnosis, which is associated with the intensity of dermatological screening, is greater among male patients, who still present with thicker lesions.

We conclude that, especially among male patients, the marked decrease in tumour thickness accounted for a small part of the recent improvement in survival observed in Italy. The introduction of targeted therapies and immunotherapies in the past decade is most likely to account for a much larger part of the improvement. This demonstrates that these treatments have the potential to have a measurable impact on the survival of patients, especially male patients, at the population level, and that the historical prognostic gap between men and women with CMM can be bridged. By implication, access to novel therapies should be ensured.

Author contributions

Federica Zamagni: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal). Lauro Bucchi: Conceptualization (lead); writing – original draft (lead). Silvia Mancini: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal). Emanuele Crocetti: Conceptualization (equal). Luigino Dal Maso: Conceptualization (equal). Stefano Ferretti: Conceptualization (equal). Annibale Biggeri: Methodology (equal). Simona Villani: Methodology (equal). Flavia Baldacchini: Investigation (equal). Orietta Giuliani: Investigation (equal). Alessandra Ravaioli: Investigation (equal). Rosa Vattiato: Investigation (equal). Angelita Brustolin: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Giuseppa Candela: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Simona Carone: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Giuliano Carrozzi: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Rossella Cavallo: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Ylenia Maria Dinaro: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Margherita Ferrante: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Silvia Iacovacci: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Guido Mazzoleni: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Antonino Musolino: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Roberto Vito Rizzello: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Diego Serraino: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Fabrizio Stracci: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Rosario Tumino: Data curation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Carla Masini: Investigation (equal). Laura Ridolfi: Investigation (equal). Giuseppe Palmieri: Resources (equal). Ignazio Stanganelli: Resources (equal). Fabio Falcini: Project administration (lead).

Supporting information

Table S1 Main characteristics of participating cancer registries, resident adult population, total number of patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma who were entered into the study, number excluded and number eligible. Italy, 2003–2017.

Table S2 Sensitivity analysis of the multivariate relative excess risk of death from cutaneous malignant melanoma by time period of diagnosis. Male patients (n = 9108), Italy, 2003–2017.

Table S3 Sensitivity analysis of the multivariate relative excess risk of death from cutaneous malignant melanoma by time period of diagnosis. Female patients (n = 8566), Italy, 2003–2017.

Figure S1 Time axis presenting the dates of approval of molecular targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of unresectable and metastatic cutaneous malignant melanoma by the US Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Agency and the Italian Drug Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco).

Video S1 Speech transcription.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Veronica Di Carlo (Cancer Survival Group, Department of Non‐Communicable Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK) for her valuable comments.

The AIRTUM Working Group

Chiara Balducci (Romagna Cancer Registry, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) ‘Dino Amadori’, Meldola, Forlì); Francesca Bella (Siracusa Cancer Registry, Health Unit of Siracusa); Rossella Cavallo (Cancer Registry ‐ ASL Salerno, Salerno); Claudia Cirilli (Modena Cancer Registry, Public Health Department, Local Health Authority, Modena); Simonetta Curatella (Latina Cancer Registry, Lazio); Stefano Ferretti (Romagna Cancer Registry, section of Ferrara, Local Health Authority and University of Ferrara, Ferrara); Graziella Frasca (Cancer Registry, Provincial Health Authority (ASP), Ragusa); Claudia Galluzzo (Registro tumori di Taranto, Unità operativa complessa di statistica ed epidemiologia, Azienda sanitaria locale Taranto); Alessio Gili (Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Perugia, Perugia); Antonella Ippolito (Integrated Cancer Registry of Catania‐Messina‐Enna, Azienda Ospedaliero‐Universitaria Policlinico ‘Rodolico‐San Marco’, Catania); Maria Michiara (Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma; Medical Oncology Unit and Cancer Registry, University Hospital of Parma, Parma); Caterina Oriente (UOSD Epidemiologia e Registro Tumori (Dip. di Prevenzione ASL VT) c/o Cittadella della Salute, Viterbo); Silvano Piffer (Trento Province Cancer Registry, Unit of Clinical Epidemiology, Azienda Provinciale per i Servizi Sanitari (APSS) Trento); Tiziana Scuderi (Trapani Cancer Registry, Dipartimento di Prevenzione della Salute, Servizio Sanitario Regionale Sicilia, Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale (ASP), Trapani); Federica Toffolutti (Cancer Epidemiology Unit, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico di Aviano (CRO) IRCCS, Aviano); and Fabio Vittadello (South Tyrol Cancer Registry, Bolzano).

Full list of affiliations

1Romagna Cancer Registry, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) ‘Dino Amadori’, Meldola, Forlì, Italy

2Cancer Epidemiology Unit, Centro di Riferimento Oncologico di Aviano (CRO) IRCCS, Aviano, Italy

3Romagna Cancer Registry, Section of Ferrara, Local Health Authority and University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy

4Department of Statistics, Computer Science, Applications G. Parenti, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

5Department of Public Health, Experimental and Forensic Medicine, Unit of Biostatistics and Clinical Epidemiology, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy

6UOSD Epidemiologia e Registro Tumori (Dip. di Prevenzione ASL VT) c/o Cittadella della Salute, Viterbo, Italy

7Trapani Cancer Registry, Dipartimento di Prevenzione della Salute, Servizio Sanitario Regionale Sicilia, Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale (ASP), Trapani, Italy

8Registro tumori di Taranto, Unità operativa complessa di statistica ed epidemiologia, Azienda sanitaria locale Taranto, Italy

9Modena Cancer Registry, Public Health Department, Local Health Authority, Modena, Italy

10Cancer Registry ‐ ASL Salerno, Salerno, Italy

11Siracusa Cancer Registry, Health Unit of Siracusa, Italy

12Integrated Cancer Registry of Catania‐Messina‐Enna, Azienda Ospedaliero‐Universitaria Policlinico ‘Rodolico‐San Marco’, Catania, Italy

13Latina Cancer Registry, Lazio, Italy

14South Tyrol Cancer Registry, Bolzano, Italy

15Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma; Medical Oncology Unit and Cancer Registry, University Hospital of Parma, Parma, Italy

16Trento Province Cancer Registry, Unit of Clinical Epidemiology, Azienda Provinciale per i Servizi Sanitari (APSS) Trento, Italy

17Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

18Former Director Cancer Registry, Provincial Health Authority (ASP), Ragusa, Italy

19Unit of Oncological Pharmacy, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) ‘Dino Amadori’, Meldola, Forlì, Italy

20Immunotherapy, Cell Therapy and Biobank, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) ‘Dino Amadori’, Meldola, Forlì, Italy

21Institute of Research on Genetics and Biomedicine (IRGB), National Research Council (CNR), Sassari, Sardegna, Italy

22Skin Cancer Unit, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) ‘Dino Amadori’, Meldola, Forlì, Italy

23Department of Dermatology, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

24Cancer Prevention Unit, Local Health Authority, Forlì, Italy

Funding sources This work was supported by the Italian Melanoma Intergroup and the Italian Ministry of Health.

Conflicts of interest The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Italian Association of Cancer Registries (AIRTUM). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the corresponding author with the permission of the Italian Association of Cancer Registries (AIRTUM).

Details of the AIRTUM Working Group can be found in Appendix 1.

A full list of affiliations can be found in Appendix 2.

This study was presented at the International Association of Cancer Registries virtual annual conference, 12–14 October 2021, and received the Elvo Tempia Special Prize. The article is based on a thesis submitted to the School of Medicine at the University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy, as part of F.Z.’s Level II Professional Master’s Programme in Biostatistics and Epidemiological Methodology.

Plain language summary available online

References

- 1. Stang A, Stang K, Stegmaier C et al. Skin melanoma in Saarland: incidence, survival and mortality 1970‐1996. Eur J Cancer Prev 2001; 10:407–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacKie RM, Bray CA, Hole DJ et al. Incidence of and survival from malignant melanoma in Scotland: an epidemiological study. Lancet 2002; 360:587–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Månsson‐Brahme E, Johansson H, Larsson O et al. Trends in incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma in a Swedish population 1976‐1994. Acta Oncol 2002; 41:138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Vries E, Bray FI, Coebergh JW, Parkin DM. Changing epidemiology of malignant cutaneous melanoma in Europe 1953‐1997: rising trends in incidence and mortality but recent stabilizations in western Europe and decreases in Scandinavia. Int J Cancer 2003; 107:119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Montella A, Gavin A, Middleton R et al. Cutaneous melanoma mortality starting to change: a study of trends in Northern Ireland. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45:2360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holterhues C, Ed Vries, Louwman MW et al. Incidence and trends of cutaneous malignancies in the Netherlands, 1989‐2005. J Invest Dermatol 2010; 130:1807–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tryggvadóttir L, Gislum M, Hakulinen T et al. Trends in the survival of patients diagnosed with malignant melanoma of the skin in the Nordic countries 1964‐2003 followed up to the end of 2006. Acta Oncol 2010; 49:665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garbe C, Keim U, Gandini S et al. Epidemiology of cutaneous melanoma and keratinocyte cancer in white populations 1943‐2036. Eur J Cancer 2021; 152:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marrett LD, Nguyen HL, Armstrong BK. Trends in the incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma in New South Wales, 1983‐1996. Int J Cancer 2001; 92:457–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Erdmann F, Lortet‐Tieulent J, Schüz J et al. International trends in the incidence of malignant melanoma 1953‐2008 – are recent generations at higher or lower risk? Int J Cancer 2013; 132:385–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crocetti E, Carli P. Unexpected reduction of mortality rates from melanoma in males living in central Italy. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39:818–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coory M, Baade P, Aitken J et al. Trends for in situ and invasive melanoma in Queensland, Australia, 1982‐2002. Cancer Causes Control 2006; 17:21–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shaikh WR, Dusza SW, Weinstock MA et al. Melanoma thickness and survival trends in the United States, 1989 to 2009. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015; 108:djv294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sacchetto L, Zanetti R, Comber H et al. Trends in incidence of thick, thin and in situ melanoma in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2018; 92:108–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiarugi A, Nardini P, Borgognoni L et al. Thick melanoma in Tuscany. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2019; 154:638–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berwick M, Reiner AS, Paine S et al. Sun exposure and melanoma survival: a GEM study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23:2145–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gandini S, Montella M, Ayala F et al. Sun exposure and melanoma prognostic factors. Oncol Lett 2016; 11:2706–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weyers W. The ‘epidemic’ of melanoma between under‐ and overdiagnosis. J Cutan Pathol 2012; 39:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Leest RJ, Zoutendijk J, Nijsten T et al. Increasing time trends of thin melanomas in The Netherlands: what are the explanations of recent accelerations? Eur J Cancer 2015; 51:2833–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Galceran J, Uhry Z, Marcos‐Gragera R et al. Trends in net survival from skin malignant melanoma in six European Latin countries: results from the SUDCAN population‐based study. Eur J Cancer Prev 2017; 26:S77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Che G, Huang B, Xie Z et al. Trends in incidence and survival in patients with melanoma, 1974‐2013. Am J Cancer Res 2019; 9:1396–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wisco OJ, Sober AJ. Prognostic factors for melanoma. Dermatol Clin 2012; 30:469–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith JA, Whatley PM, Redburn JC. Improving survival of melanoma patients in Europe since 1978. EUROCARE Working Group. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34:2197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crocetti E, Mallone S, Robsahm TE et al. Survival of patients with skin melanoma in Europe increases further: results of the EUROCARE‐5 study. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51:2179–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lasithiotakis KG, Leiter U, Eigentler T et al. Improvement of overall survival of patients with cutaneous melanoma in Germany, 1976‐2001: which factors contributed? Cancer 2007; 109:1174–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luke CG, Coventry BJ, Foster‐Smith EJ, Roder DM. A critical analysis of reasons for improved survival from invasive cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Causes Control 2003; 14:871–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Di Carlo V, Estève J, Johnson C et al. Trends in short‐term survival from distant‐stage cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 2001‐2013 (CONCORD‐3). JNCI Cancer Spectr 2020; 4:pkaa078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ugurel S, Röhmel J, Ascierto PA et al. Survival of patients with advanced metastatic melanoma: the impact of novel therapies ‐ update 2017. Eur J Cancer 2017; 83:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bucchi L, Mancini S, Crocetti E et al. Mid‐term trends and recent birth‐cohort‐dependent changes in incidence rates of cutaneous malignant melanoma in Italy. Int J Cancer 2021; 148:835–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chellini E, Crocetti E, Carli P et al. The melanoma epidemic debate: some evidence for a real phenomenon from Tuscany, Italy. Melanoma Res 2007; 17:129–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Crocetti E, Caldarella A, Chiarugi A et al. The thickness of melanomas has decreased in central Italy, but only for thin melanomas, while thick melanomas are as thick as in the past. Melanoma Res 2010; 20:422–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coviello V, Buzzoni C, Fusco M et al. Survival of cancer patients in Italy. Epidemiol Prev 2017; 41 (2 Suppl 1):1–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization . International statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, 5th edn, vol 1. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. AIRTUM Working Group . [Tumour Registration Techniques Manual]. Padova: Piccin, 2021. (in Italian). [Google Scholar]

- 35. AIRTUM Working Group. Italian cancer figures . Report 2016. Survival of cancer patients in Italy. Epidemiol Prev 2017; 41 (2 Suppl 1):1–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL FL et al. AJCC cancer staging manual, 8th edn. New York: Springer, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bianconi F, Crocetti E, Grisci C et al. What has changed in the epidemiology of skin melanoma in central Italy during the past 20 years? Melanoma Res 2020; 30:396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Perme MP, Stare J, Estève J. On estimation in relative survival. Biometrics 2012; 68:113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dickman PW, Coviello E. Estimating and modeling relative survival. Stata J 2015; 15:186–215. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Corazziari I, Quinn M, Capocaccia R. Standard cancer patient population for age standardising survival ratios. Eur J Cancer 2004; 40:2307–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu XQ, O’Connell DL, Gibberd RW et al. Trends in survival and excess risk of death after diagnosis of cancer in 1980‐1996 in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Cancer 2006; 119:894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nelson CP, Lambert PC, Squire IB, Jones DR. Flexible parametric models for relative survival, with application in coronary heart disease. Stat Med 2007; 26:5486–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lambert PC, Royston P. Further development of flexible parametric models for survival analysis. Stata J 2009; 9:165–90. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika 1976; 63:581–92. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Breslow NE, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc 1993; 88:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Argenziano G, Moscarella E, Annetta A et al. Melanoma detection in Italian pigmented lesion clinics. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2014; 149:161–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dal Maso L, Panato C, Tavilla A et al. Cancer cure for 32 cancer types: results from the EUROCARE‐5 study. Int J Epidemiol 2020; 49:1517–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:711–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2517–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jain S, Clark JI. Ipilimumab for the treatment of melanoma. Melanoma Manag 2015; 2:33–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Quintero OL, Amador‐Patarroyo MJ, Montoya‐Ortiz G et al. Autoimmune disease and gender: plausible mechanisms for the female predominance of autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 2012; 38:J109–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Joosse A, van der Ploeg AP, Haydu LE et al. Sex differences in melanoma survival are not related to mitotic rate of the primary tumor. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22:1598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Conforti F, Pala L, Bagnardi V et al. Cancer immunotherapy efficacy and patients' sex: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19:737–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bellenghi M, Puglisi R, Pontecorvi G et al. Sex and gender disparities in melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020; 12:1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Forschner A, Eichner F, Amaral T et al. Improvement of overall survival in stage IV melanoma patients during 2011‐2014: analysis of real‐world data in 441 patients of the German Central Malignant Melanoma Registry (CMMR). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017; 143:533–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jochems A, Leeneman B, Franken MG et al. Real‐world use, safety, and survival of ipilimumab in metastatic cutaneous melanoma in The Netherlands. Anticancer Drugs 2018; 29:572–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hellmund P, Schmitt J, Roessler M et al. Targeted and checkpoint inhibitor therapy of metastatic malignant melanoma in Germany, 2000‐2016. Cancers (Basel) 2020; 12:2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ellebaek E, Svane IM, Schmidt H et al. The Danish metastatic melanoma database (DAMMED): a nation‐wide platform for quality assurance and research in real‐world data on medical therapy in Danish melanoma patients. Cancer Epidemiol 2021; 73:101943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dal Maso L, Lise M, Zambon P et al. Incidence of thyroid cancer in Italy, 1991‐2005: time trends and age‐period‐cohort effects. Ann Oncol 2011; 22:957–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Rutkowski P et al. Long term follow up of the EORTC 18952 trial of adjuvant therapy in resected stage IIB‐III cutaneous melanoma patients comparing intermediate doses of interferon‐alpha‐2b (IFN) with observation: ulceration of primary is key determinant for IFN‐sensitivity. Eur J Cancer 2016; 55:111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Eggermont AM, Chiarion‐Sileni V, Grob JJ et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high‐risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double‐blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16:522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Eggermont AM, Chiarion‐Sileni V, Grob JJ et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:1845–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Main characteristics of participating cancer registries, resident adult population, total number of patients with cutaneous malignant melanoma who were entered into the study, number excluded and number eligible. Italy, 2003–2017.

Table S2 Sensitivity analysis of the multivariate relative excess risk of death from cutaneous malignant melanoma by time period of diagnosis. Male patients (n = 9108), Italy, 2003–2017.

Table S3 Sensitivity analysis of the multivariate relative excess risk of death from cutaneous malignant melanoma by time period of diagnosis. Female patients (n = 8566), Italy, 2003–2017.

Figure S1 Time axis presenting the dates of approval of molecular targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of unresectable and metastatic cutaneous malignant melanoma by the US Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Agency and the Italian Drug Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco).

Video S1 Speech transcription.