Abstract

Lactobacillus brevis is a major contaminant of spoiled beer. The organism can grow in beer in spite of the presence of antibacterial hop compounds that give the beer a bitter taste. The hop resistance in L. brevis is, at least in part, dependent on the expression of the horA gene. The deduced amino acid sequence of HorA is 53% identical to that of LmrA, an ATP-binding cassette multidrug transporter in Lactococcus lactis. To study the role of HorA in hop resistance, HorA was functionally expressed in L. lactis as a hexa-histidine-tagged protein using the nisin-controlled gene expression system. HorA expression increased the resistance of L. lactis to hop compounds and cytotoxic drugs. Drug transport studies with L. lactis cells and membrane vesicles and with proteoliposomes containing purified HorA protein identified HorA as a new member of the ABC family of multidrug transporters.

Bacterial spoilage of beer products causes a serious problem in the brewing industry. The iso-α-acids, derived from the flowers of the hop plant (Humulus lupulus L.), give beer a bitter taste and exert bacteriostatic effects on most gram-positive bacteria due to their ability to dissipate the proton motive force (13, 16, 17). A few lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus spp., are tolerant towards iso-α-acids and are able to grow in hopped beer (14, 15). At present, the molecular mechanisms that underlie the hop resistance in lactic acid bacteria are not well understood.

Previously, Sami and colleagues have isolated a hop-tolerant Lactobacillus brevis strain, ABBC45, in which the plasmid pRH45 confers hop resistance on the cells (10). pRH45 harbors the horA gene, whose corresponding deduced amino acid sequence is 53% identical to that of the multidrug transporter LmrA in Lactococcus lactis (11, 18). LmrA is a multidrug transporter able to transport a wide variety of amphiphilic compounds, including antibiotics and anticancer drugs, from the inner leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane (1, 9, 12). Unlike other known bacterial multidrug resistance proteins, LmrA is an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter (4, 21). The protein contains an N-terminal membrane domain with six transmembrane segments followed by the ABC domain. Surprisingly, LmrA is a structural and functional homologue of the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein, overexpression of which is one of the principal causes of resistance of human cancer cells to chemotherapy, and can even complement P-glycoprotein in human lung fibroblast cells (19).

In this work, HorA was functionally overexpressed in L. lactis as a hexa-histidine-tagged protein. The hop resistance of L. lactis cells was increased significantly as a result of HorA expression. The protein was purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity chromatography and functionally reconstituted into proteoliposomes prepared from L. lactis lipids. Transport studies with cells, membrane vesicles, and proteoliposomes identified HorA as a multidrug transporter which mediates the extrusion of structurally unrelated compounds, including iso-α-acids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Lactobacillus brevis ABBC45 (10) was grown aerobically at 30°C in MRS broth (Merck). Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NZ9000 was used as a host for the nisin-controlled gene expression (NICE) vector pNZ8048 (3) and its horA-containing derivatives. L. lactis was grown at 30°C in M17 broth (Difco) supplemented with 5 μg of chloramphenicol/ml and with 0.5% glucose (wt/vol) when appropriate.

Genetic manipulations.

The horA gene was amplified from pRH45 by PCR using the oligonucleotide 5′-GGG ATA CTG CAG CCA TGG GGC ATC ACC ATC ACC ATC ACG ATG ACG ATG ACA AAG CCC AAG CTC AGT CCA AGA ACA ATA CCA AG-3′ to introduce a PstI site, NcoI site, and hexa-histidine tag at the 5′ end of horA and the oligonucleotide 5′-GTA CCC TTA TCT AGA TTA TCA CCC GTT GCT C-3′ to introduce an XbaI site at the 3′ end of horA. The PCR product was cloned as a PstI-XbaI fragment into pAlter-1 (Promega) using Escherichia coli JM109 as a host. After the internal NcoI site in horA was removed silently by site-directed mutagenesis using the Altered Sites II in vitro Mutagenesis System (Promega) and the mutagenic oligonucleotide 5′-CCA GGA CCA TCG CCA TCA TGA CC-3′, the horA gene was cloned as an NcoI-XbaI fragment into pNZ8048, giving pNZHHorA. Finally, horA was sequenced to ensure that only the intended changes had been introduced.

Hop resistance.

To test the hop resistance of L. lactis NZ9000 harboring pNZ8048 or pNZHHorA, overnight cultures were diluted into fresh medium and grown to mid-exponential growth phase. Subsequently the cells were diluted to an optical density at 690 nm (OD690) of 0.1 in M17 medium containing 5 μg of chloramphenicol/ml, about 63 pg of nisin A/ml (through a 1-in-160,000 dilution of the supernatant of the nisin A-producing L. lactis strain NZ9700 [3]), and hop compounds (11) at various final concentrations (see Fig. 2). Aliquots of 200 μl of the cell suspensions were dispensed into a sterile low-protein-binding microplate (Greiner). Sterile silicon oil (50 μl) was pipetted on top of the sample to prevent evaporation. Growth was monitored at 15°C by measuring the OD690 every 40 min with a multiscan photometer (Titertek multiskan MCC/340 MKII; Flow Laboratories).

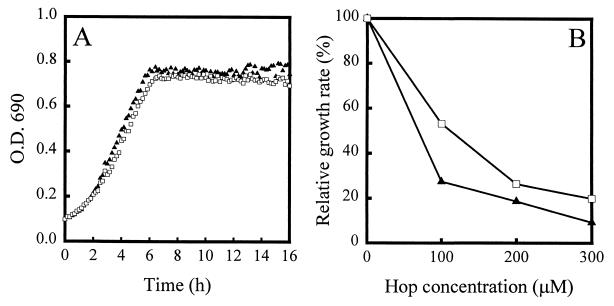

FIG. 2.

(A) Growth of control L. lactis harboring pNZ8048 (triangles) and of HorA-expressing L. lactis harboring pNZHHorA (squares) in the absence of iso-α-acids. (B) Inhibition of growth by iso-α-acids of control L. lactis (triangles) and of HorA-expressing L. lactis (squares). Cells were grown at 15°C in the absence or presence of a 50, 100, 200, or 300 μM concentration of iso-α-acids. The OD690 was measured every 10 min. The growth rates were determined at the mid-exponential phase.

Solubilization, purification, and reconstitution of histidine-tagged HorA.

L. lactis NZ9000 cells harboring pNZ8048 or pNZHhorA were grown at 30°C to an OD690 of about 0.5. Subsequently, about 10 ng of nisin A/ml was added to the culture through a 1-in-1,000 dilution of the supernatant of the nisin A-producing L. lactis strain NZ9700 (3). The cell suspensions were further incubated at 30°C for 2 h, after which the cells were collected by centrifugation. The inside-out membrane vesicles of HorA-expressing L. lactis cells were prepared using a French pressure cell, as described (5, 8, 20), and stored in liquid nitrogen. His-tagged HorA was solubilized with 1% n-dodecyl-β-maltoside as described previously (5). Insoluble components were removed by ultracentrifugation at 280,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The soluble fraction was mixed with Ni-NTA-agarose (Qiagen Inc.) (20 μl of resin/mg of protein) which was equilibrated with buffer A (50 mM KPi [pH 8.0] supplemented with 100 mM NaCl, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol and 0.05% n-dodecyl-β-maltoside). The agarose suspension was shaken gently at 4°C for 1 h. The resin was transferred to a Bio-spin column (Bio-Rad) and washed with 20 column volumes of buffer A containing 20 mM imidazole and subsequently with 10 column volumes of buffer A containing 40 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted with buffer A, adjusted to pH 7.0, and supplemented with 250 mM imidazole. For reconstitition of purified HorA in proteoliposomes of L. lactis lipids, total lipids of L. lactis were extracted and purified as described previously (5). Unilamellar liposomes with a relatively homogeneous size were prepared by freezing in liquid nitrogen, slow thawing at room temperature, and extrusion of the liposomes 11 times through a 400-nm-pore-size polycarbonate filter. The liposomes were diluted to 1 mg of phospholipid/ml, and dodecyl maltoside was added to a final concentration of 4 μmol/ml to destabilize the liposomes. The purified HorA was mixed with dodecyl maltoside-destabilized liposomes at a protein/lipid ratio of 1:100 (wt/wt), after which the suspension was incubated for 30 min at room temperature under gentle agitation. The detergent was removed by absorption to polystyrene beads (Bio-Beads SM-2; Bio-Rad) as described previously (5). Finally, the proteoliposomes were collected by ultracentrifugation at 280,000 × g for 15 min at 10°C, resuspended in 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0), and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Transport assays. (i) Ethidium transport.

L. lactis NZ9000 cells harboring pNZ8048 or pNZHhorA were grown at 30°C to an OD690 of about 0.5. Subsequently, about 10 ng of nisin A/ml was added to the culture through a 1-in-1,000 dilution of the supernatant of the nisin A-producing L. lactis strain NZ9700 (3). The cell suspensions were further incubated at 30°C for 2 h, after which the cells were collected by centrifugation at 4°C at 8,000 × g for 10 min. The cells were washed with 50 mM KPi (pH 7.0) containing 5 mM MgSO4. The washed cell suspensions (OD690 of 0.5) were incubated for 10 min at 30°C in the presence of 10 μM ethidium bromide to allow the diffusion of ethidium bromide into the cells. The ethidium bromide efflux was initiated by the addition of 25 mM glucose. The fluorescence of ethidium bromide was monitored at 20°C with a Perkin-Elmer LS 50B fluorimeter using excitation and emission wavelengths of 500 and 580 nm, respectively, and slit widths of 5 and 15 nm, respectively (18). To study the effect of ortho-vanadate on the accumulation of ethidium in HorA-expressing and nonexpressing L. lactis cells, cells were grown in medium supplemented with 30 mM arginine rather than glucose (6). After the induction of HorA expression as described above, cells were washed with 50 mM (K)HEPES (pH 7.4) supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4. Washed cells (OD690 of 0.5) were de-energized by incubation for 40 min at 30°C. Subsequently, cells were reenergized for 7.5 min by the addition of 30 mM arginine, in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM ortho-vanadate. Finally, 10 μM ethidium bromide was added to the cell suspensions, and the fluorescence of ethidium bromide was measured at 20°C as described above.

(ii) Hoechst 33342 transport.

For the transport of Hoechst 33342 in inside-out membrane vesicles, membrane vesicles were diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 mg of membrane protein/ml in KPi (pH 7.5) containing 2 mM MgSO4, 5 mM phosphocreatine, and 0.1 mg of creatine kinase/ml. Valinomycin and nigericin were added to a final concentration of 0.4 μM each, to dissipate the membrane potential and transmembrane pH gradient, respectively. After an incubation for 1 min at 20°C, 2.3 μM Hoechst 33342 was added. The fluorescence of Hoechst 33342 was measured at 20°C using a Perkin-Elmer LS 50B fluorimeter with excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 and 457 nm, respectively, and slit widths of 3 nm each. After the Hoechst 33342 fluorescence had reached a steady state, Hoechst 33342 transport was initiated by the addition of 2 mM Mg-ATP. In control experiments, Mg-ATPγS was used rather than Mg-ATP. For the transport of Hoechst 33342, HorA-containing proteoliposomes were thawed slowly and extruded 11 times through a 400-nm-pore-size polycarbonate filter. Subsequently proteoliposomes were washed twice and resuspended in 50 mM KPi (pH 7.5) or (K)HEPES (pH 7.5). The Hoechst 33342 transport assay was performed as described above in the absence of ionophores, using proteoliposomes at a final concentration of 0.01 mg of protein/ml.

RESULTS

Overexpression of hexa-histidine-tagged HorA.

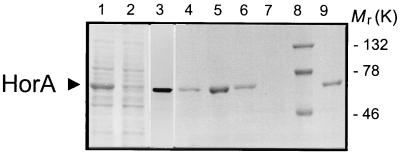

Using the polymerase chain reaction, the horA gene on plasmid pRH45 of L. brevis ABBC45 was cloned into the lactococcal NICE expression vector pNZ8048 under the control of the nisin-inducible nisA promoter. A hexa-histidine tag was added to the amino terminus of HorA to facilitate the purification of the protein by Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography. Induction of HorA expression in L. lactis NZ9000 by the addition of nisin A to exponentially growing cells resulted in the expression of a plasma membrane-associated 66-kDa polypeptide, which could be detected on a Western blot by using an anti-hexa-histidine-tag monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1). HorA expression in cells was maximal after an induction time of 2 h. Quantitative immunoblotting and densitometry analysis revealed a HorA expression level of about 30% of the total membrane protein under these conditions (data not shown). Densitometric analysis of Coomassie-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels of the membrane fraction of HorA-expressing cells and the purified HorA indicated a purity of HorA of more than 95% (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Expression, purification, and functional reconstitution of hexa-histidine-tagged HorA. The HorA protein was overexpressed in L. lactis as a hexa-histidine-tagged protein using the NICE system. A silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel is shown. Lane 1, total membrane protein (20 ug) of L. lactis harboring pNZHHorA; lane 2, soluble fraction (20 μg of protein) of a lysate of HorA-expressing cells; lane 3, Western blot of the membrane fraction (20 μg of protein) of HorA-expressing cells, with anti-hexa-histidine antibody; lane 4, flowthrough fraction of membrane proteins (20 μl of the total fraction of 2 ml) eluted from the Ni2+-NTA resin; lanes 5, 6, and 7, histidine-tagged HorA eluted from the NTA resin (20 μl out of the total fraction of 2 ml) in three consecutive steps with buffer supplemented with 250 mM imidazole; lane 8, molecular mass markers; lane 9, HorA reconstituted into proteoliposomes. Lanes 3 and 9 are Western blots; the other lanes are silver-stained gels. The arrow indicates the position of hexa-histidine-tagged HorA protein.

HorA overexpression confers hop resistance on L. lactis cells.

The hop resistance of L. lactis NZ9000 cells harboring pNZHHorA was compared with the hop resistance of cells harboring the pNZ8048 control vector. In the absence of iso-α-acids the HorA-expressing cells grew slightly more slowly and reached a slightly lower cell density than control cells (Fig. 2A). A similar effect on the growth of L. lactis was observed for LmrA-expressing cells (5). Figure 2B shows the inhibitory effects of various concentrations of the iso-α-acid compounds on the growth of HorA-expressing cells. The inhibition of growth by 100, 200, and 300 μM hop compounds is significantly higher for control cells than for HorA-expressing cells, indicating that HorA expression in L. lactis results in an increased hop resistance of the organism.

HorA is active as a multidrug transporter. (i) Ethidium transport in cells.

HorA is a homologue of the ABC multidrug transporter LmrA in L. lactis (11, 21). Fluorimetric ethidium transport assays were performed to test if HorA can mediate the transport of ethidium, a typical substrate for LmrA. Washed cell suspensions of L. lactis NZ9000 containing pNZHHorA or pNZ8048 were preequilibrated in the presence of 10 μM ethidium bromide. Subsequently the cells were energized through the addition of 20 mM glucose. The energization of cells resulted in an increased rate of ethidium extrusion for the HorA-expressing cells compared to the rate observed for nonexpressing control cells, suggesting that HorA is able to mediate the active extrusion of ethidium bromide (Fig. 3A). HorA is a member of the ABC superfamily and should display an ATP-dependent extrusion activity. To analyze whether ethidium efflux was coupled to ATP hydrolysis, the effect of the ABC transporter inhibitor ortho-vanadate was examined. For this purpose, cells were preenergized with 30 mM l-arginine and preincubated in the presence of 0.5 mM ortho-vanadate. In this way, cells could generate metabolic energy by metabolizing arginine via the arginine-deiminase pathway (6). In contrast to glycolysis, which is inhibited by ortho-vanadate, the arginine-deiminase pathway is not affected by this inhibitor. Ortho-vanadate increased the level of ethidium uptake in HorA-expressing cells, while no increase was observed in control cells. These observations indicate inhibition by ortho-vanadate of HorA-mediated efflux of ethidium (Fig. 3B and C).

FIG. 3.

Ethidium transport in HorA-expressing cells and nonexpressing cells of L. lactis. Panel (A) De-energized HorA-expressing and control cells (0.2 mg of protein/ml; OD690, 0.5) were preequilibrated with 10 μM ethidium bromide at 30°C. The development of fluorescence of the DNA-ethidium complex in the cell suspension was monitored at 20°C over time. At the arrow, 25 mM glucose was added. (B) Effect of ortho-vanadate on the accumulation of ethidium bromide in control cells. Cells were energized with arginine and incubated for 7.5 min in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM ortho-vanadate prior to the addition of 10 μM ethidium bromide (at the arrow). (C) Effect of ortho-vanadate on the accumulation of ethidium bromide in HorA-expressing cells. Cells were treated as described for panel B.

(ii) Hoechst 33342 transport in membrane vesicles.

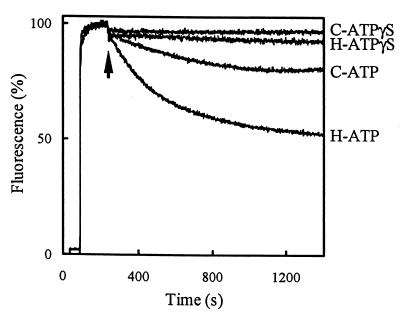

In previous studies, the positively charged bisbenzimide dye Hoechst 33342 proved to be a useful probe to study the activity of multidrug transporters such as LmrA and the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein (5, 8, 20). Hoechst 33342 is highly fluorescent when it is present in the hydrophobic environment of the phospholipid bilayer. The transport of Hoechst 33342 from the membrane into the aqueous phase can be followed as a decrease of Hoechst 33342 fluorescence over time. The ionophores valinomycin and nigericin were included in this fluorescence assay at a concentration of 0.4 μM to dissipate the membrane potential and transmembrane pH gradient, respectively, generated through proton pumping by the F1F0 H+-ATPase. In the presence of ATP, Hoechst 33342 fluorescence decreased in HorA-containing membrane vesicles five-fold faster than in membrane vesicles from control cells. In the presence of the slowly hydrolyzable ATP analog ATPγS, no significant decrease of Hoechst 33342 fluorescence was observed in both types of membrane vesicles (Fig. 4). The ATP-dependent Hoechst 33342 transport in the control cells is most likely due to the presence of low levels of endogenous LmrA, since under the experimental conditions employed the secondary multidrug-transporter LmrP cannot work because a proton motive force is absent. The results demonstrate that in the presence of Mg-ATP, HorA efficiently transports Hoechst 33342 from the membrane into the lumen of inside-out membrane vesicles prepared from HorA-expressing L. lactis.

FIG. 4.

Hoechst 33342 transport in inside-out membrane vesicles of HorA-expressing cells and nonexpressing cells of L. lactis. Membrane vesicles prepared from HorA-expressing cells (H) and control cells (C) were diluted to a concentration of 0.5 mg of membrane protein/ml in buffer containing the ATP regenerating system (see Materials and Methods) and 0.4 μM of each of the ionophores valinomycin and nigericin to dissipate the membrane potential and transmembrane pH gradient, respectively. After incubation for 1 min at 20°C, 2.3 μM Hoechst 33342 was added to the assay mixture. At the arrow, 2 mM Mg-ATP or 2 mM Mg-ATPγS was added. Hoechst 33342 transport was measured at 20°C by fluorimetry.

(iii) Hoechst 33342 transport in proteoliposomes.

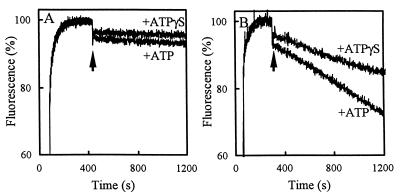

HorA-mediated transport of Hoechst 33342 was also studied using purified and functionally reconstituted protein. The protein was solubilized using 0.05% dodecyl maltoside and purified by nickel chelate affinity chromatography to a high degree of purity (Fig. 1). HorA was reconstituted by mixing the purified protein with preformed dodecyl maltoside-destabilized liposomes, composed of L. lactis lipids, after which the detergent was removed by extraction with polystyrene beads. Transport studies revealed that purified HorA was able to transport Hoechst 33342 into proteoliposomes in the presence of ATP (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Transport of Hoechst 33342 in proteoliposomes. Liposomes without reconstituted HorA protein (A) and proteoliposomes containing reconstituted HorA protein (B) were diluted in buffer containing the ATP regenerating system. After incubation for 1 min at 20°C, 2.3 μM Hoechst 33342 was added to the assay mixture. At the arrow, 2 mM Mg-ATP or 2 mM Mg-ATPγS was added.

(iv) Transport of hop compounds by HorA.

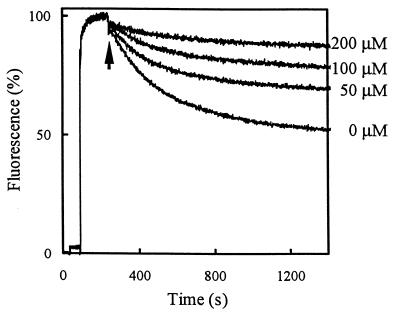

If, as indicated by the above data, HorA functions as a drug transporter with broad drug specificity, then HorA may also be able to extrude hop compounds. The specificity of HorA for hop compounds was analyzed in Hoechst 33342 transport assays in which hop compounds were included as competing substrates (Fig. 6). Because hop compounds are protonophores that act upon the proton motive force, hop compounds may also indirectly affect Hoechst 33342 partitioning in the membrane. Therefore, the ionophores valinomycin and nigericin were included in the Hoechst 33342 transport assays at final concentrations of 0.4 μM. The HorA-mediated transport of Hoechst 33342 in the presence of ionophores was inhibited by hop compounds (Fig. 6). The degree of inhibition was proportional to the concentration of hop compounds used, indicating that hop compounds are transport substrates for HorA.

FIG. 6.

HorA displays specificity for hop compounds. The ATP-dependent transport of Hoechst 33342 in HorA-containing inside-out membrane vesicles was measured as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Hop compounds at indicated concentrations were added to the assay mixture prior to the addition of Hoechst 33342. The hop compounds did not affect the fluorescence of Hoechst 33342 in control membrane vesicles without HorA (data not shown). To dissipate a proton motive force generated by F1F0-ATPase, the ionophores valinomycin (0.4 μM) and nigericin (0.4 μM) were included in the assay medium.

DISCUSSION

Although hop resistance in L. brevis is known to be linked to the increased copy number of the horA-containing plasmid pRH45 (10, 11), the mechanism of hop resistance in this organism has not been studied previously. To analyze the function of HorA in greater detail, hexa-histidine-tagged HorA was expressed in L. lactis. By employing the NICE system (3), high expression levels were obtained of up to 30% of total membrane protein. Cell fractionation studies indicated that the overexpressed HorA protein was associated with the plasma membrane in L. lactis. HorA is a member of the ABC superfamily and is a structural homologue of the multidrug transporter LmrA in L. lactis (21). Therefore, the ability of HorA to act as a drug pump was investigated. Transport experiments with HorA-expressing L. lactis cells, HorA-containing inside-out membrane vesicles, and proteoliposomes containing purified and functionally reconstituted HorA demonstrated that HorA mediated the transport of typical LmrA substrates, such as ethidium bromide and Hoechst 33342. Hence, HorA and LmrA may be functionally equivalent proteins.

Two approaches were used to assess the ability of heterologously expressed HorA to act as an extrusion system for hop compounds: (i) in vivo resistance to growth inhibition by hop compounds and (ii) the competitive inhibition of drug transport by hop compounds. The increased hop resistance in HorA-expressing L. lactis cells and the inhibition of Hoechst 33342 transport by hop compounds both indicate that hop compounds are transport substrates of HorA. Hop compounds are able to dissipate the proton motive force in gram-positive bacteria through a cycling mechanism in which the undissociated iso-α-acids enter the cell by diffusion through the phospholipid bilayer and, after the dissociation of a proton, diffuse back to the extracellular environment as anionic species (13, 14, 16, 17). The HorA-mediated resistance of cells to hop compounds suggests that HorA mediates the extrusion of undissociated iso-α-acids, by analogy with LmrA and the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein, possibly from the phospholipid bilayer.

Most known bacterial multidrug transporters use the proton motive force to drive the extrusion of drugs (7). LmrA and HorA represent prokaryotic ABC multidrug transporters that share significant sequence similarity with ABC proteins in Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Helicobacter pylori, Haemophilus influenzae, and Mycoplasma genitalium (21). Studies on the origin of multidrug resistance genes demonstrate the importance of transfer of genetic information between microorganisms in the emergence and spread of multidrug resistance (2). Although the lmrA gene is carried by the genome of L. lactis, horA is carried by a plasmid. Hence, prokaryotic members of the ABC transporter family can potentially be exchanged between pathogenic microorganisms and may be responsible for acquired multidrug resistance in these organisms (9).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Sami and H. Nakagawa for valuable discussions and G. Poelarends for drawing some of the figures.

K.S. received a grant from Asahi Breweries, Ltd., A.M. received a TMR fellowship from the European Community, and H.W.V.V. was a Fellow of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences (KNAW).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bolhuis H, van Veen H W, Molenaar D, Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Multidrug resistance in Lactococcus lactis: evidence for ATP-dependent drug extrusion from the inner leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane. EMBO J. 1996;15:4239–4245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies J. Inactivation of antibiotics and the dissemination of resistance genes. Science. 1994;264:375–382. doi: 10.1126/science.8153624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Ruyter P G G A, Kuipers O P, de Vos W M. Controlled gene expression systems for Lactococcus lactis with the food-grade inducer nisin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3662–3667. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3662-3667.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins C F. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margolles M, Putman M, van Veen H W, Konings W N. The purified and functionally reconstituted multidrug transporter LmrA of Lactococcus lactis mediates the transbilayer movement of specific fluorescent phospholipids. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16298–16306. doi: 10.1021/bi990855s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Regulation of arginine-ornithine exchange and the arginine deiminase pathway in Streptococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2755–2761. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5597-5604.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Putman M, van Veen H W, Konings W N. Molecular properties of bacterial multidrug transporters. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:672–693. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.4.672-693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putman M, van Veen H W, Poolman B, Konings W N. Restrictive use of detergents in the functional reconstitution of the secondary multidrug transporter LmrP. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1002–1008. doi: 10.1021/bi981863w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putman M, van Veen H W, Degener J E, Konings W N. Antibiotic resistance: era of the multidrug pump. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:772–774. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sami M, Suzuki K, Sakamoto K, Kadokura H, Kitamoto K, Yoda K. A plasmid pRH45 of Lactobacillus brevis confers hop resistance. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1998;44:361–363. doi: 10.2323/jgam.44.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sami M, Yamashita H, Hirono T, Kadokura H, Kitamoto K, Yoda K, Yamasaki M. Hop-resistant Lactobacillus brevis contains a novel plasmid harboring a multidrug resistance-like gene. J Ferment Bioeng. 1997;84:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shapiro A B, Ling V. Extraction of Hoechst 33342 from the cytoplasmic leaflet of the plasma membrane by P-glycoprotein. Eur J Biochem. 1999;250:122–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson W J. Ionophoric action of trans-isohumulone on Lactobacillus brevis. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1041–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson W J. Studies on the sensitivity of lactic acid bacteria to hop bitter acids. J Inst Brew. 1993;99:405–411. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson W J, Fernandez J L. Selection of beer spoilage lactic acid bacteria and induction of their ability to grow in beer. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1992;14:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson W J, Fernandez J L. Factors affecting antibacterial activity of hop compounds and their derivatives. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson W J, Fernandez J L. Mechanism of resistance of lactic acid bacteria to trans-isohumulone. J Am Soc Brew Chem. 1994;52:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Veen H W, Venema K, Bolhuis H, Oussenko I, Kok J, Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Multidrug resistance mediated by a bacterial homologue of the human multidrug transporter MDR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10668–10672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Veen H W, Callaghan R, Soceneantu L, Sardini A, Konings W N, Higgins C F. A bacterial antibiotic-resistant gene that complements the human multidrug-resistance P-glycoprotein gene. Nature (London) 1998;391:291–295. doi: 10.1038/34669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Veen H W, Margolles A, Müller M, Higgins C F, Konings W N. The homodimeric ATP-binding cassette transporter LmrA mediated multidrug transport by an alternating two-site (two cylinder engine) mechanism. EMBO J. 2000;19:2503–2514. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Veen H W, Konings W N. The ABC family of multidrug transporters in microorganisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1365:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]