Abstract

Objectives

Specialist stop smoking services can be effective for supporting women with smoking cessation during pregnancy, but uptake of these services is low. A novel theoretical approach was used for this research, aiming to identify barriers to and facilitators of engaging with specialist smoking cessation support using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).

Methods

Semi‐structured interviews and a focus group (n = 28) were carried out with pregnant women who smoke/recently quit smoking, midwives and Stop Smoking in Pregnancy advisors from two local authority commissioned services in the UK. Inductive thematic analysis was used to code interview transcripts and deductive thematic analysis used to match emerging themes to TDF domains.

Results

Themes corresponded to seven domains of the TDF: Knowledge: Knowledge of available services for pregnant smokers; Environmental context and resources: Uptake of referral to cessation services by pregnant smokers; Social Influences: Smoking norms and role of others on addressing smoking in pregnancy; Beliefs about Capabilities: Confidence in delivering and accepting pregnancy smoking cessation support; Beliefs about Consequences: Beliefs about risks of smoking in pregnancy and role of cessation services; Intentions: Intentions to quit smoking during pregnancy; Emotions: Fear of judgement from healthcare professionals for smoking in pregnancy.

Conclusions

These novel findings help to specify factors associated with pregnant women’s engagement, which are useful for underpinning service specification and design by public health commissioners and service providers. Addressing these factors could help to increase uptake of cessation services and reduce rates of smoking in pregnancy.

Keywords: pregnancy, smoking cessation, stop smoking services, theoretical domains framework

Statement of contribution.

What is already known on this subject?

Stop smoking services can help pregnant women to quit smoking, providing specialist behavioural advice and psychosocial support.

Where stop smoking services are available, engagement by pregnant women is low; the number of pregnant women setting a quit date has been in decline since 2011.

The Theoretical Domains Framework can be applied to research involving pregnant smokers and health care professionals for a thorough understanding of the examined behaviour.

What does this study add?

This is the first known study to use the Theoretical Domains Framework to explore the uptake of stop smoking services from three key viewpoints: pregnant women, midwives, and stop smoking advisors.

Pregnant smokers often disengage with services after initial appointments and reconsider their decision to quit smoking when they face difficulties. Midwives may lack knowledge of service availability and can be influenced by their own smoking habits, those of their colleagues, and social norms.

Intervention co‐production with health care professionals and pregnant smokers or ex service users would be beneficial, focusing on the service engagement and ensuring that the content is as appealing as possible to the pregnant women.

Background

Smoking during pregnancy is associated with increased rates of spontaneous abortion, placental complications, still birth, reduced birthweight, and preterm birth (Einarson & O’Riordan, 2009; Hackshaw, Rodeck, & Boniface, 2011). It is also a major risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and increased likelihood of children developing respiratory problems, behavioural disorders, such as attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and nicotine dependence in adulthood (Anderson et al., 2019; Kovess et al., 2014; Shenassa, Papandonatos, Rogers, & Buka, 2015; Silvestri, Franchi, Pistorio, Petecchia, & Rusconi, 2015). Global rates of smoking in pregnancy have been estimated at 21% (Jafari et al., 2021), although there is a wide regional variation between 1.7 and 38.4% (Lange, Probst, Rehm, & Popova, 2018). The prevalence of smoking in pregnancy has fallen considerably in high‐income countries, although not across all populations (Chamberlain et al., 2017). In England, a steady decline in the rates of smoking in pregnancy has stalled in recent years with an estimated 9.6% of pregnant women reporting smoking at time of delivery (SATOD) in England in 2020–21 (NHS Digital, 2021). Government ambitions are to reduce the rate of smoking in pregnancy to 6% or under by 2022 (Department of Health & Social Care, 2017). However, only 24 of 135 regional clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in England reached this target in Q3 2020–21 (NHS Digital, 2021).

While a global requirement for accessible and cost‐effective smoking cessation interventions has been recognised, only 23 countries provided adequate access to cessation support in 2018 (World Health Organization (WHO), 2019). Higher income countries tend to have the most resources, utilising helplines, face‐to‐face support, and internet support, while lower income countries have fewer contacts with health care professionals for smoking cessation and less access to cessation medications (Borland et al., 2012). Within the United Kingdom, the provision of effective smoking cessation support in pregnancy and referral to services are part of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standard for smoking (NICE, 2010). Stop Smoking Services (SSS) are free to attend through the National Health Service (NHS). They deliver one‐to‐one specialist behavioural stop smoking advice to smokers who wish to quit, with staff training provided by the National Centre for Smoking Cessation Training (NCSCT). The SSS offer psychosocial support which has been found to be effective for increasing smoking cessation during pregnancy, focussing on areas including problem‐solving, coping skills, and increasing motivation (Chamberlain et al., 2017). However, cuts in central government funding have had an impact on the commissioning of numerous SSS (Iacobucci, 2018). This has led to a ‘postcode lottery’ in the availability of SSS for pregnant women, which is reflected in the reduction of pregnant women setting a quit date through the SSS since 2011/12 (NHS Digital, 2021).

Where services exist, uptake is often low, with engagement as low as 2% in some areas (Bennett et al., 2014). Several studies have identified barriers to accessing the SSS among pregnant women, including the fear of stigmatisation by health care professionals, expectation of disappointment if they are unable to stop smoking, and difficulty accessing services due to work commitments and childcare issues (Bryce, Butler, Gnich, Sheehy, & Tappin, 2009; Ussher, Etter, & West, 2006). While some pregnant women may show an interest in engaging with cessation support, this does not always lead to the actual uptake of services (Naughton et al., 2020). The SSS need to be more widely available to pregnant women, but other barriers to engagement with these services must also be addressed. There is, however, only limited research on the uptake of services by pregnant women (Naughton et al., 2020), with much of the current literature focussed on the barriers to, and facilitators of, pregnancy smoking cessation (e.g. Campbell et al., 2018; Fergie, Campbell, et al., 2019; Fergie, Coleman, Ussher, Cooper, & Campbell, 2019; Flemming et al., 2016; Naughton et al., 2018).

While there is a need for research to explore engagement with smoking cessation services by pregnant women, such research can be more easily translated into practice if it is built on a theoretical framework, which aims to understand the context of behaviour (Michie et al., 2018). One such framework is the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) – an integrative framework that synthesizes behaviour change theories and key constructs into 14 theoretical domains (Cane, O'Connor, & Michie, 2012; Michie et al., 2005). These constructs map on to the three central components of the capability, opportunity, and motivation model of behaviour (COM‐B) – a broad system that guides the understanding of behaviour in the context within which it occurs, which is linked to the behaviour change wheel (BCW) for guiding the intervention design (Michie, Atkins, & West, 2014, p. 59). The TDF has demonstrated utility for investigating midwives’ communication with pregnant women about stopping smoking (Beenstock et al., 2012) and for categorizing barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy (Campbell et al., 2018). However, it has not yet been applied to the issues of engaging with support to stop smoking during pregnancy.

The current study focusses on exploring barriers to and facilitators of engaging with cessation support by pregnant women from the perspectives of the three most relevant stakeholder groups; pregnant women who smoke or recently stopped smoking, midwives, and stop smoking in pregnancy advisors. The TDF was chosen as the framework for this work, alongside the COM‐B, due to its potential for gaining a thorough understanding of the issue.

Method

Study design

This was a qualitative study, consisting of semistructured interviews and a focus group. This study is reported using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research framework (SRQR) (O’Brien, Harris, Beckman, Reed, & Cook, 2014) (see Table S1). The lead researcher (SG) was undertaking a PhD at the time of the study and holds an MSc in Health Psychology. SG had also previously carried out research around the smoking behaviour of young people and had also worked as a stop smoking advisor, including work with pregnant women. One study author is a never smoker and two are ex‐smokers, demonstrating understanding of the complexities of stopping smoking on both personal and professional levels.

Ethics

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the university sponsoring the research, the local authority that commissioned services involved, and the Health Research Authority – Camden and Kings Cross REC (IRAS ID: 196050). Local permission was also granted by four NHS trusts covering the region where all data were collected.

Participants

For data triangulation, participants were recruited across three groups: pregnant women, midwives, and stop smoking in pregnancy advisors. To be eligible for participation, women had to be pregnant (at any stage of pregnancy) or to have been pregnant with in the last six months, and had to be a smoker or recent ex‐smoker (smoked within the last six months and to have smoked during any point of their current pregnancy). They also had to be over the age of 18 years, able to give informed consent to participate, and be fluent in spoken and written English. Pregnant women were given £10‐£15 in shopping vouchers as a than you for their time, depending on the length of the interview.

Midwives working in community settings – including GP surgeries, children’s centres and in women’s homes – and three hospital settings were recruited to capture experiences across all areas of midwifery practice. All stop smoking advisors worked in the community only, predominantly visiting women within their own home. The sample sizes for each recruitment pool were to be determined by data saturation, whereby no new themes were emerging from the data. A combination of convenience and purposive sampling was used for recruiting pregnant women and midwives across different hospital settings and NHS trusts. As there were fewer SSiPS staff in the area, all were approached and all agreed to participate.

Procedure

The study took place in two local authorities in the UK Midlands between September 2016 and March 2017. Pregnant women were first approached by their midwife or stop smoking in pregnancy advisor and asked if they would be happy to talk to a researcher about their experiences of smoking in pregnancy and then provided with further information. The researcher then contacted the participant directly to confirm consent and arrange an interview. Social media recruitment involved advertising for pregnant women via a poster placed on various pregnancy‐specific Facebook and Twitter pages. Pregnant women were either interviewed face‐to‐face in their own home or by phone.

Midwives and stop smoking advisors were recruited across four local NHS trusts through their co‐ordinator, maternity matron, or head of midwifery. The lead researcher (SG) met once with stop smoking advisors from one of the local authorities before the interviews to discuss the study and their participation. All midwives and pregnant women participants were not known to the researcher before the study. The majority of health care professionals were interviewed at their work base, with two midwives interviewed by telephone. Semi‐structured interview schedules were developed for midwives, stop smoking advisors, and pregnant women. Questions about smoking in pregnancy were focussed on the three core components of the COM‐B (physical and psychological capability, social and physical opportunity, reflective and automatic motivation) and further broken down into twenty‐nine questions relating to the 14 domains of the TDF (see Table S2). For example, for the TDF domain ‘Environmental context and resources’, SSiPS advisors were asked ‘What do you think stops women from attending the SSiPS? What do you think would make them more likely to attend?’ (see Appendix S1). A risk perception intervention had recently been introduced in two NHS trusts involved in this study at the time it was undertaken. Questions about this were therefore asked of the midwives and stop smoking advisors. The risk perception intervention is part of the BabyClear enhanced treatment and referral pathway, where women who decline referral or who withdraw from the SSiPS attend an appointment with a trained midwife, who provides powerful information about the risks of smoking in the pregnancy, and are then referred back to the SSiPS (Bell et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2019).

As one of the SSiPS teams (n = 4) requested a focus group, a shortened interview schedule was provided with ten similar questions to those asked in interviews based around the TDF (see Appendix S1). This was to allow time for more open discussion to develop around each key question. The remaining advisors and midwives participated in individual face‐to‐face interviews. Interviews lasted between 20 and 125 minutes, with a mean of 50 minutes. The focus group lasted 60 minutes. Data saturation was achieved from each recruitment pool, with no new data emerging.

Analysis

Interviews were audio‐recorded, transcribed verbatim by the researchers, and then checked against the original audio. Pseudonyms were assigned to all participant data to anonymise the content. Transcripts were then analysed in NVivo v12 software using thematic analysis in line with Braun and Clarke (2006). Interaction data from the focus group were not considered, and the interview and focus group data were analysed collectively. Data were analysed by recruitment pool and inductively organised into themes, which were then deductively matched to TDF domains and COM‐B components. Any themes that did not appear to fit TDF domains were further analysed to ascertain whether additional codes could be added to those from the TDF. Secondary coding was performed on 10% of interview transcripts (n = 3) by a member of the research team (KB) who was experienced with use of the TDF. A high level of agreement was seen in the coding, although some discrepancies arose where data/themes could be mapped to more than one TDF theme. Any issues were discussed to determine the most appropriate domain for the data/theme.

Results

Eight pregnant women aged between 20 and 38 years (gestation range = 13–39 weeks) were recruited in total: seven through the NHS (one through midwifery and six through the SSiPS) and one through social media recruitment. Approximately 40 midwives were provided with further information about the study and ten agreed to participate (age range = 29–52 years). All ten stop smoking advisors working in the local SSiPS agreed to participate (age range = 24–56 years). Four of these stop smoking advisors took part in a single focus group at their team base, while the remaining six advisors participated in individual face‐to‐face interviews. Further participant characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Participant group | Mean age (SD) | Age range (years) | Gestation weeks, weeks (SD) | Pregnancy status | Ethnicity (%) | Smoking status | Employed | Time in employment, mean years (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | 28.2 years (5.7) | 20–38 | 24.5 weeks (9.1) | Primigravida = 5; Multigravida = 3 | White British = 8 (100%) | 50% smokers; 50% recent ex‐smokers | Employed = 8 (100%) | N/A |

| Midwives | 47.7 years (8.1) | 29–52 | – | – |

White British = 9 (90%); White Irish = 1 (10%) |

100% non‐smokers | – | 13.6 years (6.8) |

| Stop smoking advisors | 48.2 years (10.4) | 24–56 | – | – |

White British = 8 (80%); White Irish = 1 (10%); Mixed ethnicity = 1 (10%) |

100% non‐smokers | – | 7.0 years (3.6) |

Theoretical Domains Framework

Data presented by pregnant women, midwives and stop smoking advisors specifically about engaging with support to stop smoking in pregnancy were collated into 18 subthemes, which were then matched to seven of the 14 TDF domains for either health care professionals or pregnant women (see Table 2). The seven TDF domains where data were matched are likely to represent the most important targets for service specification and design where increasing engagement with services is of concern. Only data relating to the behaviour of engaging with support to stop smoking are presented for this study; data which matched to the remaining seven TDF domains were predominantly related to the behaviour of smoking cessation, and this is reported elsewhere (Griffiths, 2019). An illustration of the TDF with definitions for each domain can be found in Table S2.

Table 2.

TDF themes and subthemes for engaging with support to stop smoking

| TDF Domain: Theme title | HCPs perceptions of the barriers/facilitators to engaging with the support (B/F) | Pregnant women’s perceptions of the barriers/facilitators (B/F) |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge: knowledge of available services for pregnant smokers |

|

|

| Environmental context and resources: uptake of referral to cessation services by pregnant smokers |

|

|

| Social influences: smoking norms and role of others on addressing smoking in pregnancy |

|

|

| Beliefs about capabilities: confidence in delivering and accepting pregnancy smoking cessation support |

|

|

| Beliefs about consequences: beliefs about the risks of smoking in pregnancy and the role of cessation services |

|

|

| Intentions: intentions to stop smoking in pregnancy |

|

|

| Emotion: fear of judgement from health care professionals for smoking in pregnancy |

|

|

Knowledge: Knowledge of available services for pregnant smokers

In order to engage with the SSiPS, pregnant women who smoke need to be aware that services exist, as well as how they can access services and how it can help them to quit. Most women had either not heard of the SSiPS or were not aware of what the SSiPS could offer before they saw the midwife or were referred to the service, often making it more difficult to engage with the service:

I’d heard of (the SSiPS) but I didn’t know what they did … I s’pose if you’re not really looking to quit you’re not really going to look into it. Clare, pregnant woman (recently quit)

In order to address the lack of awareness about the service, midwives need to be able to provide this information during early pregnancy and to repeat this advice throughout pregnancy for those who continue to smoke. However, hospital‐based midwives also appeared to have deficient knowledge of the SSiPS, with uncertainty about who they were and what their role was:

I know we’ve got a smoking cessation midwife but I think we may have more, I don’t know if the nursing side do something as well. Karen, hospital‐based midwife

While community midwives were generally more aware of the SSiPS, some demonstrated a lack of knowledge of what the service offered pregnant women. When asked what she thought about the SSiPS and what it could offer to pregnant women, one midwife replied ‘I’ve only met them once for half an hour, but the girls [pregnant women] say that it’s great’ (Freya, community midwife). All midwives should be given 30 minutes training annually, and this midwife had not had any further direct contact or discussion with them. Another community midwife appeared unaware that the SSiPS can provide 12 weeks or more of support to help pregnant women, and that women can be referred back to the service if they relapse later in pregnancy:

One to one support, which the stop smoking girls can do but only for a limited time, which we’re finding they have their like four weeks or something and they do really well during that time that people are going to visit them and then after that they’re coming back at you know 28, 32 weeks and they’ve started smoking again. Where do we get that support for the women, I don’t know. Hannah, community midwife

Environmental context/resources: Uptake of referral to cessation services by pregnant smokers

Best practice guidelines recommend that pregnant smokers follow an ‘opt‐out’ referral process, whereby they are first identified using exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) testing and then automatically referred for cessation support, unless they decline (NICE, 2010). At the time of interviews, this was a recent introduction locally and was increasing across local midwifery services. These changes, as well as the introduction of the new risk perception intervention, led to increased referrals to the local SSiPS, with one advisor commenting that ‘there were more smokers hiding in there, now we’ve wriggled them out’ (Nina, advisor).

However, in terms of delivery of the risk perception intervention, midwives and advisors discussed how this was in the early stages. Implementation issues in the north of the region meant that appointments had to be made for women to attend for a risk perception appointment, rather than it being given immediately after the dating scan as intended, which the majority did not attend. One community midwife commented that ‘We’ve not been able to get it in practice how it should work’ (Hannah, community midwife). Some pregnant smokers who declined referral to the SSiPS still had no follow‐up regarding smoking in pregnancy above usual midwifery care.

Pregnant women discussed how the process of being referred to the SSiPS was easy and facilitated their engagement with the service. The following quote highlights how some women only engaged because the SSiPS contacted them:

I think if the midwife hadn’t got (my advisor) to phone me I wouldn’t have contacted her. It was only because she phoned me and she was like right this is what’s going to happen… I wouldn’t have phoned up myself… I think I would have been like I don’t need it or I’m just wasting somebody’s time because I’m not ready to stop. Faye, pregnant woman (smoker)

While referral processes helped to get some women to engage with the SSiPS, the issues with women accepting their referrals was a common theme and a considerable barrier to the provision of support by the SSiPS. Once a referral is made from midwifery, the SSiPS attempt to contact women to arrange an appointment. It was repeated by all advisors that once women engaged, they had overcome the biggest barrier of ‘getting through the door’:

I know amongst the team that once we’re in we tend to get quite a good [quit] rate but getting in is another thing, if they don’t answer the phone, they don’t return your calls or your texts, they’re not in for their appointments, er that’s the biggest barriers really. Jane, advisor

Also repeated by several advisors was the issue of women who had engaged with the service then dropped out after one or more sessions:

Probably my most common one is where you have seen somebody for the first time and they’ve signed up and said yes I’m gonna quit and then they don’t or they change their mind and then they don’t want to tell you… And they’re the difficult ones… Somehow we’ve lost them so there’s something there isn’t there. Sam, advisor

Most women who had engaged with the SSiPS found the support they were given beneficial. One participant described it as ‘ absolutely brilliant… I just think I couldn’t say a bad thing really’ (Clare, pregnant woman – recently quit). These positive experiences with the SSiPS helped to keep some women engaged and to continue with their quit attempts. However, not all women who had engaged with the SSiPS had a positive experience. One pregnant woman had managed to cut down using NRT but was told that her advisor could not support her unless she stopped completely. For another woman, the focus of the SSiPS to support women to completely abstain from smoking, rather than cutting down, made her drop out of the service:

I was down to smoking one in the morning and one at night and then not smoking any in the day, and then she said it was all or nothing kind of thing and I just kind of like left it, stopped talking to her, and had a really good Christmas [laughs]. That was it. Jennifer, pregnant woman (smoker)

Social influences: Smoking norms and role of others on addressing smoking in pregnancy

Pregnant women are most likely to first hear about the SSiPS from their midwife at their booking appointment. As such, SSiPS advisors discussed the influential role of midwives and how they could help to ‘sell’ the service to pregnant smokers, making it feel like part of routine care:

I think maybe if the midwives could sell us a bit better… to make it sort of sound more like we’re part of the same service… sometimes I s’pose they think oh it’s something I don’t need to access. So it would be good if they thought it was a routine thing that they had to access you know. Alison, advisor

Some midwives expressed reluctance to talk about smoking with pregnant women as they had colleagues who smoked, or they used to smoke themselves and knew how hard it was to stop. Other midwives discussed their colleagues’ smoking behaviour as influential over their confidence in delivering advice to pregnant smokers. When asked whether she thought her colleagues were happy to discuss smoking in pregnancy with pregnant women, one midwife responded:

I think some midwives are uncomfortable about doing that particularly if those midwives smoke as well. Hannah, community midwife

Smoking in pregnancy was also described as so common in one hospital that it was seen as normal behaviour that did not need addressing, leading midwives to overlook the risks involved:

I think you can develop a little bit of, oh yeah that’s just what [name of area]’s like and we can expect a lot of smokers, that’s not ideal. You kind of just accept the status quo… from my own point of view because smoking is so common you kind of just get used to it and you forget what a damaging impact it really does have. Louise, hospital midwife

Beliefs about capabilities: Confidence in delivering and accepting smoking cessation support

As talking to women about smoking in pregnancy is a high priority for midwives, it is important that they feel confident in having conversations about the issue and highlighting the risks to the mother and unborn baby and the advantages of quitting. While attending risk perception training gave some midwives increased knowledge and confidence in talking to women about the risks of smoking in pregnancy, a number of midwives expressed a general lack of confidence in delivering the risk perception intervention due to the direct approach required and perceived confrontation:

I think to become confrontational in that way is quite difficult, it’s something I would really find quite difficult, and I think women that we deal with can be quite defensive as well as to the choices they’ve made so, and it’s just arguing with people. Kate, hospital‐based midwife

In order to engage with the SSiPS, women also need to feel confident that the service can help them to quit smoking. Advisors talked about the initial barriers they faced with women who did not think the service would be able to help them:

Some people probably just don’t think they need it… they might just think well not believe that we’re gonna do anything for them and think that they’re just as likely to do it on their own. Alison, advisor

Similarly, some pregnant women assumed that health care professionals, including advisors, had never smoked, believing that they could not understand how difficult it was to stop smoking:

They haven’t got the knowledge or the personal experience of trying to quit smoking, they just think oh it should be easy, and that’s the impression that pregnant women get. Vicky, pregnant woman (smoker)

Beliefs about consequences: Beliefs about the risks of smoking in pregnancy and the role of cessation services

In order to engage with support to stop smoking, pregnant women need to believe that smoking during pregnancy comes with the increased risks of prenatal birth, and postnatal complications, and that quitting is a necessity. While giving advice about the consequences of smoking to women is part of the role of both midwives and the SSiPS, advisors talked about the difficulties of trying to support women who did not believe that smoking in pregnancy is harmful. This highlights the importance of women being able to apply knowledge of the risks to themselves and their baby:

But it was just obvious that she did not want to engage, and there were ashtrays in the room, she obviously smoked in the room with these babies in it, she had 6 kids and… she told me she smoked through all of her pregnancies … she just did not accept that smoking was bad in pregnancy. Jane, advisor

As well as not fully accepting the risks of smoking during pregnancy, some women who had engaged with the SSiPS felt that their advisor was taking something away from them, which created a barrier to a successful quit. This led to some women withdrawing from the service after initial engagement:

To have a fag that was my thing you know… the cigarette was my thing and it’s kind of the only thing I did do. So it’s kind of, let’s says it’s my hobby, so well she was taking it away from me and saying you know I thought that getting down to 1‐2 was really good but to her it wasn’t. So that’s probably the main reason why I didn’t message her back. Jennifer, pregnant woman (smoker)

Intentions: Intentions to stop smoking in pregnancy

To engage with support to stop smoking, pregnant women need to have the intention to quit. After engaging with the SSiPS and trying to quit, as all interviewed women did, difficult quitting experiences led some of them to change their mind about quitting. Two of the pregnant women who had wanted to quit smoking at the start of their pregnancies decided that they no longer wanted to. This led to them withdrawing from the SSiPS:

To be honest, when I first found out (I was pregnant) I was like yeh I’m gonna quit, and I did try but I also found it very difficult and then I realised that actually I didn’t want to quit. Vicky, pregnant woman (smoker)

Emotions: Fear of judgement from health care professionals for smoking in pregnancy

The stigma surrounding smoking in pregnancy could prevent women from requesting help to stop smoking, fearing judgement from health care professionals. Denial and guilt were identified by health care professionals as barriers to seeking support for smoking cessation in pregnancy. Health care professionals also talked about women believing that the SSiPS would be judgemental and would tell them they had to stop smoking:

You know they’ll think ok you’re gonna come along tell them what to do, which isn’t the case, and judge them and look down on them aren’t they a terrible person aren’t they a terrible mum for smoking when they know that they shouldn’t. Sam, advisor

This concern was reflected by pregnant women who discussed initial worries that the SSiPS would make judgements about their continued smoking or force them to stop smoking. Vicky, a pregnant woman, was apprehensive about engaging with the SSiPS at first, but her experiences were generally positive:

When I’ve tried to quit before and I’ve gone through the doctors with the no smoking stuff, not the pregnancy one they’re quite judgemental sometimes … so I was a little bit hesitant about them coming round, (my advisor) coming round like, but she was lovely and she was not pressurising you into doing anything and all that sort of thing. Vicky, pregnant woman (smoker)

Discussion

This study provides unique insight into engagement with cessation support among pregnant women from three key perspectives: pregnant women, midwives, and stop smoking in pregnancy advisors. Triangulated data identified seven of the Theoretical Domains Framework domains as barriers and/or facilitators to engagement behaviour by pregnant smokers: knowledge: awareness of services for pregnant smokers; environmental context and resources: uptake of referral to cessation services by pregnant smokers; social influences: smoking norms and role of others in addressing smoking in pregnancy; beliefs about capabilities: confidence in delivering and accepting pregnancy smoking cessation support; beliefs about consequences: beliefs about the risks of smoking in pregnancy and role of cessation services; intentions: intentions to quit smoking during pregnancy; emotions: fear of judgement from health care professionals for smoking in pregnancy. These domains represent factors likely to be important in influencing service uptake that can be targeted in future stop smoking in pregnancy service specification and design.

Despite the existence of the SSiPS for over 20 years, pregnant women and midwives are still not well informed about their availability and what they can offer. There is a need for additional public health messages to raise awareness of the availability and benefits of cessation services (Butterworth, Sparkes, Trout, & Brown, 2014; Kwah, Fulton, & Brown, 2019), and to highlight both the professionalism, expertise and also non‐judgemental approach of those working in these services. The health care professionals interviewed for the current study also discussed how pregnant women need to be aware of the risks of smoking in pregnancy in order to engage with support to stop smoking. However, the provision of risk information alone is unlikely to encourage women into specialist cessation services if they have already developed their own perceptions of risk from their own environment, such as living with other smokers or having a family history of smoking in pregnancy (Wigginton & Lafrance, 2014). This is a particular barrier for health care professionals as pregnant women have been shown to be more likely to trust personal experience, and the experiences of others close to them, over medical information about the risks of smoking in pregnancy (Ingall & Cropley, 2010).

This may also contribute to pregnant women’s apparent change of intentions to stop smoking as seen in the current study, where women who intended to stop smoking faced problems with quitting, leading to continued smoking and withdrawal from SSiPS. Work around cognitive dissonance has found that difficulties with smoking cessation can lead pregnant women to resolve discrepancies between wanting to protect their baby and their desire to smoke by endorsing beliefs that allow for continued smoking (Naughton, Eborall, & Sutton, 2013). Further research with pregnant women who smoke is required to identify ways to address these complex and deep‐routed beliefs, which have been identified as long‐standing barriers to smoking cessation in pregnancy (Campbell et al., 2018; Riaz, Lewis, Naughton, & Ussher, 2018).

Referrals to SSiPS from maternity services had improved as a result of increased CO monitoring at booking‐in appointments and opt‐out referral processes. This is consistent with published research demonstrating the effectiveness of the opt‐out referral pathway for pregnant smokers and CO testing all pregnant women at booking (Bell et al., 2017; Campbell et al., 2016). However, also highlighted by existing research is a corresponding increase in the number of women being referred for support who are not motivated to fully engage with the SSiPS (Bauld et al., 2012; Sloan et al., 2016). This issue was apparent in the current study, with SSiPS advisors expressing difficulties with women withdrawing from the service after their first appointment or accepting the initial referral but being uncontactable by the service. The introduction of the risk perception intervention was also reported by advisors in the current study to have led to an increase in referrals (e.g., Bell et al., 2017). However, a lack of available staffing and resources locally meant that the programme was not being delivered as intended, resulting in very few women engaging with the SSiPS. One of the issues identified with the BabyClear programme, which risk perception is part of, is in implementation into local contexts, which vary across NHS Trusts, highlighting a need for both staff commitment to programme implementation and for the provision of resources to enable this (Jones et al., 2019).

A striking finding from this study is the role of midwives’ own smoking behaviour on approaching the issue of smoking with pregnant women. Some midwives discussed how being an ex‐smoker themselves meant that they did not want to make women feel judged by discussing smoking with them, or they did not want to offend colleagues who smoked. The normality of smoking in specific areas also made some midwives less inclined to discuss smoking with pregnant women. Pregnant women are often influenced by the views of their midwife; if the midwife does not discuss smoking or does not place enough emphasis on the need for complete abstinence, they may inadvertently pass on the message that continued smoking is acceptable (Naughton et al., 2013). This can then affect the pregnant smoker’s decision to engage with support services. Research using the social ecological framework on health care professionals’ perspectives of smoking cessation in pregnancy has also highlighted how non‐SSiPS staff often lack confidence in discussing smoking in pregnancy (Naughton et al., 2018). These issues need addressing to ensure that all maternity staff are equipped with knowledge and confidence to discuss smoking with pregnant women, so they can give brief advice and refer pregnant smokers to specialist support, as recommended by NICE guidelines (NICE, 2010).

Strengths and limitations

This study has highlighted the key areas where barriers to and facilitators of engaging with support to stop smoking in pregnancy exist. Exploring the views of the health care professionals who work most closely with pregnant women who smoke, as well as those of pregnant women, provides unique triangulation of the issues of engaging with smoking cessation support. Application of the TDF framework to the study design and analysis provides insight that is both rich and diverse, with HCPs and pregnant women responding openly and honestly in interviews and the focus group. These insights can also be directly linked to evidence‐based strategies to support better future service engagement because of the framework’s synthesis with the BCW approach to intervention development (Michie et al., 2014). In addition, the application of the TDF ensured that a diverse range of determinants of service uptake were considered due to the framework’s synthesis of theoretical approaches. This can be considered advantageous over selecting one theoretical perspective to drive the study design (McGowan, Powell, & French, 2020).

However, it has also been argued that covering such a broad range of potential influences may lead to difficulties in identifying the key barriers and overlooking important determinants (Lawton et al., 2015). Using a rigid framework may also result in less spontaneous and more forced responses from participants (Debono et al., 2017). While this study used both inductive and deductive data analysis, using the TDF more flexibly for interview schedules and data analysis in future studies could ensure that no key issues are overlooked (McGowan et al., 2020).

Six out of the eight pregnant women who participated in this study had engaged with the SSiPS during their most recent pregnancy. This high engagement with the SSiPS is not representative of the wider population of pregnant smokers. Pregnant women who do not engage with the SSiPS and continue to smoke are likely to have less motivation to stop smoking and therefore may hold different views and beliefs relating to engaging with smoking cessation support. Further work with this population, such as those who have attended the risk perception intervention after declining referral to the SSiPS, may offer additional insight into the barriers to engaging with support to stop smoking in pregnancy. These women, however, are likely to be more difficult to engage in the research process, and their voices and perspectives may remain unheard without concerted effort.

Further limitations are in the homogeneity within pregnant women participants’ ethnicity, with all participants being white British; it would have been beneficial to have a more diverse sample to assess if further barriers to engaging with support exist across different ethnicities. It was also not possible to ascertain levels of socioeconomic status due to the insensitivity of asking questions relating to this in an interview study.

Recruiting midwives working across all settings, and time constraints faced by the local‐community midwives, led to a slightly larger number of hospital midwives participating than community midwives. It would have been beneficial to have a more even balance of hospital and community midwives, although data from hospital midwives regarding their knowledge of available support and confidence in talking to pregnant women about smoking has raised further issues, which may not have been otherwise identified.

Recommendations for practice

Issues with the current care pathway for pregnant smokers exist, as demonstrated by inconsistencies in levels of knowledge about the SSiPS, the risks of smoking in pregnancy, and roll out of the risk perception intervention. Improvements in training provision for midwifery services would help to enhance midwifery knowledge and confidence in approaching difficult conversations with pregnant smokers (Lee, Griffiths, & Barror, 2020), as was demonstrated by the risk perception intervention training in the current study. Staff members, particularly from maternity services and SSiPS, should be involved in service development in order to improve communication and increase awareness of the provision of specialist clinical services (Naughton et al., 2018). While the introduction of the risk perception programme and training had initiated some improvements in relationships between the SSiPS and midwifery, further progress is still required to have more impact on engagement with cessation services. If midwives can promote the need to stop smoking during pregnancy with knowledge and confidence, this will portray a more positive image of the SSiPS and how they are approachable, professional and specialists in their area. An assertive message from midwives concerning the need for smoking abstinence, regardless of their own views, would also make pregnant smokers more likely to understand the need for smoking cessation and for engaging with support.

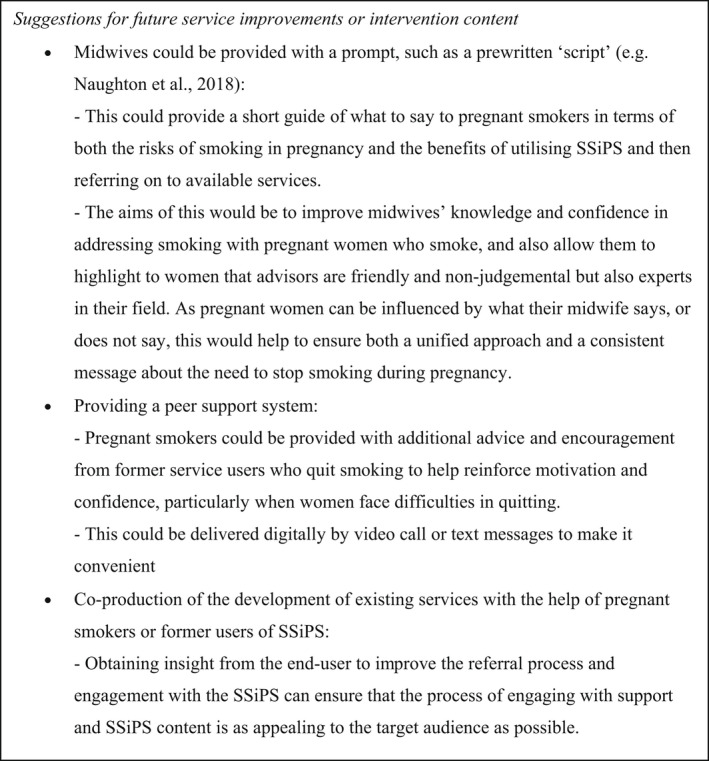

As pregnant women are likely to find quitting smoking challenging, leading to the use of strategies to endorse beliefs that make it easier for them to keep smoking, the SSiPS could also help women to develop counter strategies to stop them endorsing in disengagement beliefs when tempted to smoke (Naughton et al., 2013). Increasing pregnant women’s understanding of the sorts of mechanisms they may subconsciously employ to justify continued smoking while also increasing their motivation and confidence in being able to stop completely, may help to keep them engaged with the SSiPS when faced with difficulties. Given the issues with engaging with pregnant women, exploring other avenues of providing support or enhancing existing support is also required. There are likely to be multiple ways in which the findings from this study can be translated into service or intervention components to increase engagement. Figure 1 provides suggestions of how this could be done.

Figure 1.

Suggestions for service/intervention content.

Conclusion

Enhancing midwifery knowledge regarding the availability of local cessation services and how they can benefit pregnant smokers, as well as helping them to promote services, would play a large part in getting more pregnant smokers into specialist cessation services. In addition, further research with pregnant smokers is required to identify ways to address deep‐routed beliefs about the safety of smoking in pregnancy and ways of combating disengagement beliefs, which promote continued smoking above the risks of harm to the baby. As well as leading to increased engagement with cessation support, this would help to encourage women to persist with the service even if they are struggling to quit smoking.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the local authority where the research was conducted as part of a PhD studentship.

Author Contribution

Sarah Ellen Griffiths: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Resources (equal); Software (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Felix Naughton: Conceptualization (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Katherine E. Brown: Conceptualization (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Supervision (equal); Validation (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal).

Supporting information

Table S1. The Standards for the Reporting of Qualitative Research Guidelines (SRQR) Checklist http://www.equator‐network.org/reporting‐guidelines/srqr/

Table S2. The Theoretical Domains Framework (from Michie, Atkins & West, 2014).

Appendix S1. Sample Interview Questions.

†Where the work was carried out.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Anderson, T. , Lavista Ferres, J. , Ren, S. , Moon, R. , Goldstein, R. , Ramirez, J. , & Mitchell, E. (2019). Maternal smoking before and during pregnancy and the risk of sudden unexpected infant death. Pediatrics, 143(4), e20183325. 10.1542/peds.2018-3325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauld, L. , Hackshaw, L. , Ferguson, J. , Coleman, T. , Taylor, G. , & Salway, R. (2012). Implementation of routine biochemical validation and an ‘opt out’ referral pathway for smoking cessation in pregnancy. Addiction, 107(2), 53–60. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenstock, J. , Sniehotta, F. F. , White, M. , Bell, R. , Milne, E. M. G. , & Araújo‐Soares, V. (2012). What helps and hinders midwives in engaging with pregnant women about stopping smoking? A cross‐sectional survey of perceived difficulties among midwives in the North East of England. Implementation Science, 7, 36. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, R. , Glinianaia, S. , van der Waal, Z. , Close, A. , Moloney, E. , Jones, S. , … Rushton, S. (2017). Evaluation of a complex healthcare intervention to increase smoking cessation in pregnant women: Interrupted time series analysis with economic evaluation. Tobacco Control, 27, 90–98. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, L. , Grant, A. , Jones, S. , Bowley, M. , Heathcote‐Elliott, C. , Ford, C. , … Paranjothy, S. (2014). Models for Access to Maternal Smoking cessation Support (MAMSS): A study protocol of a quasi‐experiment to increase the engagement of pregnant women who smoke in NHS Stop Smoking Services. BMC Public Health, 14, 1041. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32259-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland, R. , Li, L. , Driezen, P. , Wilson, N. , Hammond, D. , Thompson, M. E. , … Cummings, K. M. (2012). Cessation assistance reported by smokers in 15 countries participating in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) policy evaluation surveys. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 107(1), 197–205. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03636.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce, A. , Butler, C. , Gnich, W. , Sheehy, C. , & Tappin, D. M. (2009). CATCH: development of a home‐based midwifery intervention to support young pregnant smokers to quit. Midwifery, 25(5), 473–482. 10.1016/j.midw.2007.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, S. , Sparkes, E. , Trout, A. , & Brown, K. (2014). Pregnant smokers’ perceptions of specialist smoking cessation services. Journal of Smoking Cessation, 9(2), 8597. 10.1017/jsc.2013.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K. A. , Cooper, S. , Fahy, S. , Bowker, K. , Leonardi‐Bee, J. , McEwan, A. , … Coleman, T. (2016). ‘Opt‐out’ referrals after identifying pregnant smokers using exhaled air carbon monoxide: Impact on engagement with smoking cessation support. Tobacco Control, 26, 300–306. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K. A. , Fergie, L. , Coleman‐Haynes, T. , Cooper, S. , Lorencatto, F. , Ussher, M. , … Coleman, T. (2018). Improving behavioral support for smoking cessation in pregnancy: What are the barriers to stopping and which behavior change techniques can influence these? Application of Theoretical Domains Framework. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 359. 10.3390/ijerph15020359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane, J. , O'Connor, D. , & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(37), 1–17. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, C. , O’Mara‐Eves, A. , Porter, J. , Coleman, T. , Perlen, S. M. , Thomas, J. , & McKenzie, J. E. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debono, D. , Taylor, N. , Lipworth, W. , Greenfield, D. , Travaglia, J. , Black, D. , & Braithwaite, J. (2017). Applying the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and targeted interventions to enhance nurses' use of electronic medication management systems in two Australian hospitals. Implementation Science, 12(1), 42. 10.1186/s13012-017-0572-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Social Care . (2017) Towards a Smokefree Generation: A Tobacco Control Plan for England. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/630217/Towards_a_Smoke_free_Generation_‐_A_Tobacco_Control_Plan_for_England_2017‐2022__2_.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Einarson, A. , & Riordan, S. (2009). Smoking in pregnancy and lactation: A review of risks and cessation strategies. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 65(4), 325–330. 10.1007/s00228-008-0609-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergie, L. , Campbell, K. A. , Coleman‐Haynes, T. , Ussher, M. , Cooper, S. , & Coleman, T. (2019). Stop smoking practitioner consensus on barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation in pregnancy and how to address these: A modified Delphi survey. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 9, 100164. 10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergie, L. , Coleman, T. , Ussher, M. , Cooper, S. , & Campbell, K. A. (2019). Pregnant smokers’ experiences and opinions of techniques aimed to address barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 2772. 10.3390/ijerph16152772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming, K. , Graham, H. , McCaughan, D. , Angus, K. , Sinclair, L. , & Bauld, L. (2016). Health professionals’ perception of the barriers and facilitators to providing smoking cessation advice to women in pregnancy and during the post‐partum period: A systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Public Health, 16, 290. 10.1186/s12889-016-2961-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, S. E. (2019). The Design and Development of a Multi‐Component Intervention to Increase Uptake of the Warwickshire Stop Smoking in Pregnancy Service. Retrieved from https://pureportal.coventry.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/the‐design‐and‐development‐of‐a‐multi‐platform‐intervention‐to‐in

- Hackshaw, A. , Rodeck, C. , & Boniface, S. (2011). Maternal smoking in pregnancy and birth defects: A systematic review based on 173,687 malformed cases and 11.7 million controls. Human Reproduction Update, 17(5), 589–604. 10.1093/humupd/dmr022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobucci, G. (2018). Stop Smoking Services: BMJ analysis shows how councils are stubbing them out. BMJ, 362, k3649. 10.1136/bmj.k3649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingall, G. , & Cropley, M. (2010). Exploring the barriers of quitting smoking during pregnancy: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Women and Birth, 23(2), 4552. 10.1016/j.wombi.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, A. , Rajabi, A. , Gholian‐Aval, M. , Peyman, N. , Mahdizadeh, M. , & Tehrani, H. (2021). National, regional, and global prevalence of cigarette smoking among women/females in the general population: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 26, 5. 10.1186/s12199-020-00924-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. , Hamilton, S. , Bell, R. , Araujo‐Soares, V. , Glinianaia, S. V. , Milne, E. M. G. , … Shucksmith, J. (2019). What helped and hindered implementation of an intervention package to reduce smoking in pregnancy: Process evaluation guided by Normalization Process Theory. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 297. 10.1186/s12913-019-4122-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovess, V. , Keyes, K. M. , Hamilton, A. , Pez, O. , Bitfoi, A. , Koç, C. , … Susser, E. (2014). Maternal smoking and offspring inattention and hyperactivity: Results from a cross‐national European survey. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(8), 919–929. 10.1007/s00787-014-0641-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwah, K. L. , Fulton, E. A. , & Brown, K. E. (2019). Accessing National Health Service Stop Smoking Services in the UK: A COM‐B analysis of barriers and facilitators perceived by smokers, ex‐smokers and stop smoking advisors. Public Health, 171, 123–130. 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange, S. , Probst, C. , Rehm, J. , & Popova, S. (2018). National, regional, and global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the general population: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 6(7), e769–e776. 10.1016/s2214-109x(18)30223-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, R. , Heyhoe, J. , Louch, G. , Ingleson, E. , Glidewell, L. , Willis, T. A. , … the ASPIRE programme . (2015). Using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to understand adherence to multiple evidence‐based indicators in primary care: A qualitative study. Implementation Science, 11, 113. 10.1186/s13012-016-0479-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B. , Griffiths, S. E. , & Barror, A. (2020). Coventry and Warwickshire Smoking in Pregnancy Review. Retrieved from https://www.happyhealthylives.uk/our‐priorities/maternity‐and‐paediatrics/pregnancy‐smoking/

- McGowan, L. J. , Powell, R. , & French, D. P. (2020). How can use of the Theoretical Domains Framework be optimized in qualitative research? A rapid systematic review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 25, 677–694. 10.1111/bjhp.12437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S. , Atkins, L. , & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. Sutton, UK: Silverback Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S. , Carey, R. N. , Johnston, M. , Rothman, A. J. , de Bruin, M. , Kelly, M. P. , & Connell, L. E. (2018). From theory‐inspired to theory‐based interventions: A protocol for developing and testing a methodology for linking behaviour change techniques to theoretical mechanisms of action. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(6), 501–512. 10.1007/s12160-016-9816-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S. , Johnston, M. , Abraham, C. , Lawton, R. , Parker, D. , Walker, A. & “Psychological Theory” Group . (2005). Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: A consensus approach. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 14(1), 26–33. 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . (2010). Smoking: Stopping in Pregnancy and After Childbirth [PH26]. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph26 [Google Scholar]

- Naughton, F. , Eborall, H. , & Sutton, S. (2013). Dissonance and disengagement in pregnant smokers: A qualitative study. Journal of Smoking Cessation, 8(1), 24–32. 10.1017/jsc.2013.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton, F. , Hopewell, S. , Sinclair, L. , McCaughan, D. , McKell, J. , & Bauld, L. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation in pregnancy and postpartum: The healthcare professionals’ perspective. British Journal of Health Psychology, 23(3), 41‐757. 10.1111/bjhp.12314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton, F. , Vaz, L. , Coleman, T. , Orton, S. , Bowker, K. , Leonardi‐Bee, J. , … Ussher, M. (2020). Interest in and use of smoking cessation support across pregnancy and postpartum. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 22(7), 1178–1186. 10.1093/ntr/ntz151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHS Digital . (2021). Statistics on NHS Stop Smoking Services in England April 2019 to March 2020. Retrieved from https://digital.nhs.uk/data‐and‐information/publications/statistical/statistics‐on‐nhs‐stop‐smoking‐services‐in‐england/april‐2019‐to‐march‐2020/part‐1‐‐‐stop‐smoking‐services#pregnant‐women [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, B. C. , Harris, I. B. , Beckman, T. J. , Reed, D. A. , & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89, 1245–1251. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, M. , Lewis, S. , Naughton, F. , & Ussher, M. (2018). Predictors of smoking cessation during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Addiction, 113, 610–622. 10.1111/add.14135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenassa, E. D. , Papandonatos, G. D. , Rogers, M. L. , & Buka, S. L. (2015). Elevated risk of nicotine dependence among sib‐pairs discordant for maternal smoking during pregnancy: Evidence from a 40‐year longitudinal study. Epidemiology, 26(3), 441–447. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri, M. , Franchi, S. , Pistorio, A. , Petecchia, L. , & Rusconi, F. (2015). Smoke exposure, wheezing, and asthma development: A systematic review and meta‐analysis in unselected birth cohorts. Pediatric Pulmonology, 50(4), 353–362. 10.1002/ppul.23037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, M. , Campbell, K. A. , Bowker, K. , Coleman, T. , Cooper, S. , Brafman‐Price, B. , & Naughton, F. (2016). Pregnant women’s experiences and views on an ‘opt‐out’ referral pathway to specialist smoking cessation support: A qualitative evaluation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 18(5), 1–6. 10.1093/ntr/ntv273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher, M. , Etter, J.‐F. , & West, R. (2006). Perceived barriers to and benefits of attending a stop smoking course during pregnancy. Patient Education and Counseling, 61(3), 467–472. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton, B. , & Lafrance, M. N. (2014). ‘I think he is immune to all the smoke I gave him’: How women account for the harm of smoking during pregnancy. Health, Risk and Society, 16(6), 530–546. 10.1080/13698575.2014.951317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (2019). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic – offer help to quit tobacco use. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. The Standards for the Reporting of Qualitative Research Guidelines (SRQR) Checklist http://www.equator‐network.org/reporting‐guidelines/srqr/

Table S2. The Theoretical Domains Framework (from Michie, Atkins & West, 2014).

Appendix S1. Sample Interview Questions.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.