Abstract

Introduction

Harboring two copies of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε2 allele strongly protects against Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, the effect of this genotype on gray matter (GM) volume in cognitively unimpaired individuals has not yet been described.

Methods

Multicenter brain magnetic resonance images (MRIs) from cognitively unimpaired ε2 homozygotes were matched (1:1) against all other APOE genotypes for relevant confounders (n = 223). GM volumes of ε2 genotypic groups were compared to each other and to the reference group (APOE ε3/ε3).

Results

Carrying at least one ε2 allele was associated with larger GM volumes in brain areas typically affected by AD and also in areas associated with cognitive resilience. APOE ε2 homozygotes, but not APOE ε2 heterozygotes, showed larger GM volumes in areas related to successful aging.

Discussion

In addition to the known resistance against amyloid‐β deposition, the larger GM volumes in key brain regions may confer APOE ε2 homozygotes additional protection against AD‐related cognitive decline.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Alzheimer's disease signature, apolipoprotein E ε2 carrier, brain maintenance, brain morphology, brain reserve, cognitive reserve, magnetic resonance, multi‐site, resilience signature

1. BACKGROUND

The apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene is the major genetic risk‐modifying factor for sporadic Alzheimer's disease (AD). Carrying one or two copies of the ɛ4 allele confers higher risk for AD (allelic dose odds ratio [OR]: 6), whereas carrying the ɛ2 allele confers lower risk for AD (allelic dose OR: 0.38). 1 , 2 , 3 The increased AD risk as a consequence of carrying at least one ɛ4 allele has been primarily related to a higher amyloid‐β (Aβ) burden in the brain, in a dose dependent manner (i.e., number of ɛ4 alleles). 4 However, neuroimaging studies have shown a relationship between ɛ4 gene dose and lower brain glucose hypometabolism and smaller gray matter (GM) volumes in AD‐related brain areas, 5 , 6 even in cognitively unimpaired individuals. These findings suggest an ɛ4 gene dose reduced capacity to maintain brain health. 7

On the other hand, the ε2 allele has received much less attention, presumably due to the low frequency of this polymorphism in the general population (8.4%). 8 APOE ɛ2 carriers have lower Aβ burden among non‐demented participants. 9 , 10 However, multiple studies suggest that the ɛ2 allele may reduce the risk of AD through Aβ‐independent pathways. 11 One of these pathways may be through maintained GM volumes across the lifespan. In healthy adolescents no differences between ɛ2 and ɛ4 carriers or dose dependent effects of these alleles were found in hippocampal volumes. 12 However, potential gene dose effects of the ɛ2 allele in adults remain to be described. Previous literature on adults has only reported differences between ɛ2 carriers and non‐carriers, or against ε4 carriers, all showing larger GM volumes or cortical thickness in association with the ε2 allele, in AD‐sensitive regions such as the entorhinal cortex. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 These results suggest that ɛ2 carriers may have higher brain reserve, 7 which might allow them to better cope with aging and pathology. In line with this, it has been reported that ɛ2 carriers remain cognitively unimpaired for a longer period even in the rare case of developing AD pathology (i.e., Aβ and tau). 17 , 18 Studying the brain properties in late‐/middle‐aged cognitively unimpaired ɛ2 carriers may increase our understanding of the biological mechanisms associated with this protective allele.

Importantly, to better clarify the mechanisms related to the APOE ɛ2 allele, it would be necessary to test its impact both on brain areas that are the target of incipient degeneration, and on those related to cognitive resilience. The thinning of specific areas such as the entorhinal cortex or temporal areas has shown a tight association with the progression of AD. 19 , 20 On the other hand, the maintenance of metabolism in other areas, such as the anterior cingulate or the temporal pole, has been related to preserved cognitive function. 21 These facts suggest that metabolic and volumetric measures in these regions are of particular interest when studying characteristics related to AD.

This study aimed to investigate the association between the APOE ɛ2 genotype and brain morphology in late‐/middle‐aged cognitively unimpaired individuals, with a focus on ɛ2/ɛ2 individuals and ɛ2 allele dose effects. We performed two sets of analyses: a hypothesis‐driven analysis in which we studied the ɛ2 allele effects on areas related to AD (i.e., AD signature and resilience signature); and a hypothesis‐free approach in which we expanded these analyses to the whole brain. For both sets of analyses, GM volumes of all ε2 genotypic groups (i.e., ɛ2/ɛ2, ɛ2/ɛ3, and ɛ2/ɛ4) were compared to the reference ε3/ε3 group, as well as to one another. The genotypic dose‐dependent effects (i.e., dominant, additive, and recessive) of the ε2 allele were also investigated. Finally, we computed a continuous measure to capture the risk of AD related to the APOE genotype (i.e., APOE genotype‐related AD risk). Effects of this measure on GM volumes were explored and compared to those of the ε2 allele. We hypothesized that (1) APOE ε2 carriership would be associated to larger GM volumes in areas known to be affected in AD 19 and areas related to successful aging, 21 (2) a higher dose of ε2 allele would be related to larger GM volumes, and (3) these effects would contribute to the global APOE genotype‐related AD risk effect on GM volumes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Leveraging a previous multi‐cohort study, 22 we checked the cohorts for cognitively unimpaired APOE ε2/ε2 individuals and extended our search to new cohorts. The final selection included: the ALFA (Alzheimer's and Families) study from Barcelona, Spain; 23 the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort (ADC) from the Netherlands; 24 , 25 the Gothenburg H70 Birth cohort study (H70) from Sweden; 26 the BioFINDER (www.biofinder.se) from Sweden; the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI; http://adni.loni.usc.edu/) from the United States and Canada; and the Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS; http://www.oasis‐brains.org/) from the United States 27 (see supporting information for a description of each cohort). The search in AIBL (Australian Imaging, Biomarker & Lifestyle Study of Ageing; https://aibl.csiro.au/) and in Japanese ADNI (https://humandbs.biosciencedbc.jp/en/hum0043‐v1) cohorts did not return any APOE ε2/ε2 individual in their magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) arms. The search in AddNeuroMed 28 and the CBAS (Czech Brain Aging Study) 29 cohorts only identified APOE ε2/ε2 individuals with cognitive impairment, and so were not included in this study.

We first selected all cognitively unimpaired APOE ε2/ε2 individuals who had T1‐weighted MRI data available. The criteria for classifying individuals as cognitively unimpaired were similar in all cohorts, including: normal global cognition as reflected by a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 or a Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 25 or higher, and/or normal cognition as decided by a multidisciplinary consensus panel of experts (see supporting information). After selecting the APOE ε2/ε2 individuals as the reference group, we selected one participant of each of the other APOE genotypes to match every APOE ε2/ε2 individual using age, sex, and education as matching variables, within each of the cohorts. Because matching was performed within cohorts, the six APOE genotype groups were also matched for scanner/protocol except for the ADNI, because the ADNI was designed to provide comparable images across scanners and protocols (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/methods/mri‐tool/mri‐analysis/). In the ADC, some individuals did not get a match with exactly the same MRI protocol. For those individuals, we selected the most similar MRI protocol in terms of manufacturer, field strength, and acquisition parameters.

2.2. Image processing

Participants were scanned using T1‐weighted sequences with comparable scanning protocols and image resolution across cohorts (see the supporting information). GM was segmented and warped into Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space following a standard procedure using SPM12 (see supporting information). Images were spatially smoothed with an 8‐mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel. Total intracranial volume (TIV) was computed as the sum of GM, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid volume partitions using the CAT12 toolbox.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: The authors reviewed previous literature related to apolipoprotein E (APOE) effects on Alzheimer's disease (AD)‐related phenotypes, with specific attention to those linked to brain morphology. Although studies focusing on the effects of the APOE ε2 allele, and especially of the ε2 homozygosity, are scarce, we have cited those related to our research.

Interpretation: Our study increases our knowledge about APOE, and especially APOE ε2, effects on gray matter volumes and suggest a mechanism through which APOE ε2 homozygotes may maintain their cognitive function throughout life even in the improbable case of developing AD pathology.

Future directions: In this study, we have proved the value of studying gene dose effects of the ε2 allele over the frequently investigated carriership effects. Future studies about the APOE ε2 allele need to further explore these gene dose effects on other important AD‐related phenotypes. This may help us to understand the exceptional low risk of these subjects to develop AD dementia.

HIGHLIGHTS

Cognitively unimpaired ε2 carriers have larger gray matter (GM) volumes than ε3 homozygotes.

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε2 carriership is associated with larger GM volumes in the Alzheimer's disease signature.

APOE ε2 homozygotes have larger GM volumes in areas related to cognitive resilience.

Genotypic APOE effect on GM volume is not only due to ε4 but also to ε2 effects.

To calculate regional GM volume we used the cortical and subcortical areas from the Desikan‐Killiany 30 atlas. We summed the intensity of the modulated GM images in the MNI space in each region across individuals. We also created two composite regions of interest (ROIs) to specifically investigate the brain areas known to be typically affected in AD, as well as areas known to be associated with successful aging or resilience. Following previous studies, the AD signature ROI was created by combining the entorhinal cortex, inferior and middle temporal and fusiform gyrus 19 ; and the resilience signature ROI was created by combining the anterior cingulate and temporal pole regions. 21 We also performed asymmetry analysis (see the next section), which included a medial‐temporal lobe (MTL) composite ROI that combined hippocampus, amygdala, and parahippocampal ROIs. 16

2.3. Statistical analysis

We compared the demographic characteristics across APOE genotypes using analysis of variance (for continuous variables) and χ2 (for categorical variables). All analyses described below for APOE effects on GM volume were performed in two different sets of analyses. First, we specifically tested for APOE effects on areas related to AD (i.e., AD signature and resilience signature). Second, we expanded the approach to a whole‐brain analysis.

2.3.1. Comparisons between APOE ε2 genotypic groups

We first compared each ε2 genotypic group (i.e., ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, and ε2/ε4) to the reference group (i.e., ε3 homozygotes), and also to each other (i.e., ε2/ε2 vs. ε2/ε3, ε2/ε2 vs. ε2/ε4, and ε2/ε3 vs. ε2/ε4). Generalized linear models were used to compare each pair of groups to GM volume as the dependent variable and the APOE genotype as the variable of interest. Age, sex, education, scanner (as a dummy variable), and TIV were included as covariates. The models used were analogous for both sets of analyses (i.e., AD composites and whole brain).

2.3.2. Dose‐dependent effects of the APOE ε2 allele on GM volume

The second aim of this study was to investigate particular dose‐dependent effects of the ε2 allele on GM volumes. Similar statistical models were used in these analyses but including only ε2 carriers and ε3 homozygotes in this case. APOE ε2/ε4 participants were excluded from this analysis to avoid the influence of the APOE ε4 allele. 31 Contrasts were designed to test for dominant (i.e., APOE ε2 carriers vs. APOE ε3/ε3 individuals), additive (i.e., APOE ε2/ε2 vs. APOE ε2/ε3 vs. APOE ε3/ε3), and recessive (i.e., APOE ε2/ε2 vs. APOE ε2/ε3 plus APOE ε3/ε3) effects of the APOE ε2 allele. 32

As an additional analysis we also investigated right‐left hemispheric asymmetry 16 , 33 on GM volume in the MTL as a composite and each of the ROIs included in the MTL composite (i.e., hippocampus, amygdala, and parahippocampus). We replicated the previous analysis using the asymmetry metrics as dependent variables and the same covariates excluding TIV, as the asymmetry value is already normalized by the total volume of the region itself.

2.3.3. Comparison of ε2 and global APOE genotype‐related AD risk effects on GM volume

The third aim of this study was to investigate the APOE genotypic effect on GM volume and compare it to the previous ε2 dose‐dependent effects. We created a new variable that we called “APOE genotype‐related AD risk,” which encoded the risk of AD for each of the genotypes as a continuous variable. Our goal was to create a measure related to the APOE genotype that would capture the related risk of developing AD and investigate whether this was associated to GM volumes. This variable was calculated by log‐transforming previously published odds ratios for developing AD associated to each APOE genotype, with APOE ε3/ε3 individuals as the reference group (Table S1 in supporting information). 3 We repeated the composite‐based and the whole‐brain analyses using the APOE genotype‐related AD risk value as an independent variable (as a continuous variable). In addition, we also performed Spearman's rank correlations between the regional effects of the APOE genotype‐related AD risk and the dose‐dependent effects of the ε2 allele. These correlations aimed to compare global APOE and ε2 standalone effects on GM volumes.

For all three objectives, statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 using the false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment for multiple testing (hypothesis‐free approach), and at uncorrected P < 0.05 for the a priori selected areas related to AD (hypothesis‐driven approach). In addition, supporting information shows the results from uncorrected P < 0.05 in the hypothesis‐free approach, for completeness of information.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

The sample was composed of 223 cognitively unimpaired individuals, including 38 APOE ε2/ε2 individuals and 38 matched individuals for each of the other APOE genotypes (except for the APOE ε2/ε4 group, which included 33 participants due to unavailability of suitable matches for 5 cases). All individuals were matched for age, sex, and education within the center. As shown in Table 1, there were no statistically significant differences in these variables by the APOE group. Moreover, MMSE scores and TIV did not show significant differences among APOE groups.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics

| All (n = 223) | ε2/ε2 (n = 38) | ε2/ε3 (n = 38) | ε3/ε3 (n = 38) | ε2/ε4 (n = 33) | ε3/ε4 (n = 38) | ε4/ε4 (n = 38) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old), mean (SD) [min–max] | 64.6 (8.9) [45.8–88.0] | 65.0 (9.1) [49.8–88.0] | 64.9 (8.8) [47.9–87.0] | 65.0 (9.2) [48.8–88.0] | 64.2 (9.2) [45.8–88.0] | 64.7 (9.2) [50.5–88.0] | 64.0 (8.7) [52.1–81.0] | 0.994 |

| Women, n (%) | 99 (44.4) | 17 (44.7) | 16 (42.1) | 17 (44.7) | 14 (42.7) | 18 (47.4) | 17 (44.7) | 0.998 |

| Education (years), mean (SD) | 14.2 (3.6) | 14.2 (3.8) | 14.3 (3.6) | 14.5 (3.7) | 13.8 (3.2) | 14.1 (3.7) | 14.1 (3.4) | 0.973 |

| MMSE, mean (SD) * | 28.9 (1.2) | 29.2 (1.0) | 29.0 (1.1) | 29.1 (1.0) | 28.8 (1.2) | 28.6 (1.8) | 28.8 (1.0) | 0.417 |

| TIV (cm3), mean (SD) | 1491.4 (146.7) | 1481.3 (1287.1) | 1474.4 (126.7) | 1486.6 (142.9) | 1505.8 (158.9) | 1490.3 (130.0) | 1512.1 (133.7) | 0.878 |

|

Cohort: ADC/ADNI/ALFA/BioFINDER/H70/OASIS |

72/18/42/31/18/42 | 12/3/7/6/3/7 | 12/3/7/6/3/7 | 12/3/7/6/3/7 | 12/3/7/1/3/7 | 12/3/7/6/3/7 | 12/3/7/6/3/7 | – |

*MMSE from one individual is missing.

Abbreviations: ADC, Amsterdam Dementia Cohort; ADNI, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; ALFA, Alzheimer's and Families; H70, Gothenburg H70 Birth cohort study; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; OASIS, Open Access Series of Imaging Studies; SD, standard deviation; TIV, total intracranial volume.

3.2. Comparisons between APOE ε2 genotypic groups

We first investigated whether there were significant differences between groups on two AD‐related GM volume ROI composites: the AD signature and the resilience signature. APOE ε2/ε3 participants had larger GM volume in the AD signature areas compared to ε3 homozygotes (Table 2 and Figure 1). Within the resilience signature, ε2 homozygotes had larger GM volumes than the ε3/ε3 and ε4/ε4 groups.

TABLE 2.

APOE effects on GM volumes in AD‐related areas

| AD signature | Resilience signature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| βstd [95%CI] | P‐value | βstd [95%CI] | P‐value | |

| Comparisons between ε2 genotypic groups | ||||

| ε2/ε2 vs. ε3/ε3 | 1.41 [–0.56, 3.38] | 0.161 | 2.36 [0.39, 4.33] | 0.019 |

| ε2/ε3 vs. ε3/ε3 | 2.71 [0.74, 4.69] | 0.007 | 1.66 [–0.33, 3.63] | 0.101 |

| ε2/ε4 vs. ε3/ε3 | 0.95 [–1.02, 2.92] | 0.342 | 0.62 [–1.36, 2.59] | 0.540 |

| ε2/ε2 vs. ε2/ε3 | –1.22 [–3.19, 0.74] | 0.222 | 0.75 [–1.22, 3.65] | 0.453 |

| ε2/ε2 vs. ε2/ε4 | 0.41 [–1.56, 2.38] | 0.680 | 1.67 [–0.31, 3.64] | 0.098 |

| ε2/ε3 vs. ε2/ε4 | 1.61 [–0.36, 3.58] | 0.109 | 0.95 [–1.03, 2.93] | 0.347 |

| Dose‐dependent effects | ||||

| Dominant ε2 | 2.64 [0.66, 4.62] | 0.010 | 2.07 [0.09, 4.05] | 0.041 |

| Additive ε2 | 1.60 [–0.39, 3.58] | 0.114 | 1.92 [–0.07, 3.87] | 0.058 |

| Recessive ε2 | 0.09 [–1.88, 2.07] | 0.926 | 0.21 [–0.02, 0.47] | 0.239 |

| APOE genotype‐related AD risk | –2.15 [–4.11, –0.17] | 0.033 | –1.67 [–3.63, 0.30] | 0.096 |

Notes: Results of the analysis of the comparisons between ε2 genotypic groups; dose‐dependent (additive, recessive, and dominant) effects of the ε2 allele and APOE genotype‐related AD risk effect on GM volume in areas related to AD. 19 , 21 The first column of each effect shows the βstd (calculated as the estimate divided by SE) and 95%CI, the second the respective P‐value. A negative value of the last row shows a negative correlation between GM volume and the APOE genotype‐related AD risk, meaning more GM volume for a lower AD risk related to APOE genotype. Significant results (P < 0.05) are shown in bold and those that showed a trend to significance (P < 0.100) are shown in italics

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CI, confidence interval; GM, gray matter; ROI, region of interest; SE, standard error; βstd, standardized β.

FIGURE 1.

Association between APOE genotype and GM volume in AD‐related areas. Adjusted GM volume in areas affected in AD (AD signature; 19 left) and in areas known to be associated with successful aging or resilience (resilience signature; right) 21 by APOE genotype. GM volumes were adjusted by age, sex, education, scan, and TIV. *P < 0.05; · P < 0.10. AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; GM, gray matter; TIV, total intracranial volume

In the whole‐brain analysis, ε2/ε2 and ε2/ε3 APOE groups showed larger GM volumes than ε3 homozygotes (Figure 2A). Differences between ε2/ε2 and ε3 homozygotes and between ε2/ε3 and ε3 homozygotes were widespread across the brain. On the other hand, ε2/ε4 participants only showed larger volumes in the inferior parietal and in the inferior temporal gyri, although these differences did not survive the FDR adjustment (Figure S1A in supporting information).

FIGURE 2.

Comparisons between APOE ε2 genotypic groups. Comparisons between APOE ε2 genotypic groups and APOE‐ε3 homozygotes as the reference group (A); and between each pair of APOE ε2 genotypic groups (B). Colors indicate the effect size of each effect in regions that were statistically significant (P < 0.05 FDR‐adjusted). AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; FDR, false discovery rate; GM, gray matter; LH, left hemisphere; RH, right hemisphere

When studying differences between ε2 genotypic groups, we found the largest differences between ε2/ε2 and ε2/ε4 groups, including bilateral postcentral gyri, and right parahippocampal and posterior cingulate gyri (Figure 2B). APOE ε2 homozygotes only showed larger volumes than ε2/ε3 participants in the right precentral gyrus, but this difference did not survive the FDR adjustment (Figure S1B). In addition, ε2/ε3 had larger volumes than ε2/ε4 participants in bilateral postcentral gyri.

3.3. Dose‐dependent effects of the APOE ε2 allele on GM volume

In the ROI analyses, we found a significant dominant effect of higher GM volume associated with the ε2 allele on both AD‐related composites (Table 2). The additive effect also showed a trend to significance in the same direction for the resilience signature, but no other significant effects were observed.

Figure 3 shows the significant areas that had a positive association between GM volume and each of the gene‐dose effects of the ε2 allele in whole‐brain analyses, after the FDR adjustment for multiple testing. Uncorrected results can be found in the supporting information for completeness of information (Figure S2). The dominant effect was the most widespread including multiple AD‐related areas such as the fusiform gyrus, precuneus, or the posterior cingulate. Additive effect was also widespread, although less so than the dominant effect. Finally, the recessive effect was only significant in the paracentral and the pars opercularis of the right hemisphere. Negative associations were not observed for any of the three effects (i.e., the ε2 allele was not associated with a smaller GM volume in any brain region).

FIGURE 3.

Dose‐dependent effects of the APOE ε2 allele. Dose‐dependent effects of the ε2 allele on GM volume (from left to right: dominant, additive, and recessive). APOE ε2/ε4 participants were not included in this analysis. Colors indicate the effect size of each effect in regions that were statistically significant (P < 0.05 FDR‐adjusted). AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; FDR, false discovery rate; GM, gray matter; LH, left hemisphere; RH, right hemisphere

Additional analyses for asymmetry effects in the subregions of MTL showed that the ε2 recessive, dominant, and additive effects were stronger in the right hemisphere only in the parahippocampal gyrus (Figure S3 in supporting information). More specifically, ε2 homozygotes had greater right–left asymmetry (R > L) than ε3 homozygotes.

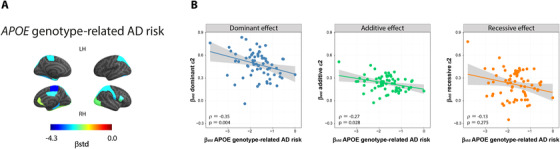

3.4. Comparison of ε2 and global APOE genotype‐related AD risk effects on GM volume

In the composite‐based analysis, the APOE genotype‐related AD risk showed a negative association with GM volume in the AD signature (F = 4.61, P = 0.033) and a trend in the resilience signature, in the same direction (F = 2.81, P = 0.096). Both results indicate lower GM volumes for a higher risk of AD, which is related to the APOE genotype in these areas (Table 2). Figure 4A shows the specific regions of this negative correlation for the APOE genotype‐related AD risk with GM volume. In particular, the increased risk of AD dementia related to APOE genotype correlated with less GM volume in brain areas overlapping with parts of the AD signature such as the entorhinal and the fusiform, as well as with parts of the resilience signature such as the anterior cingulate. Results uncorrected for multiple comparisons can be found in Figure S4 in supporting information.

FIGURE 4.

APOE genotype‐related AD risk effect on GM volume and association to APOE ε2 effects. APOE genotype‐related AD risk effects on GM volume (A). Colors indicate the effect size of each effect in regions that were statistically significant (P < 0.05 FDR‐adjusted). Associations between dose‐dependent effects of the ε2 allele (βstd) on GM volume (from left to right: dominant, additive, and recessive) and APOE genotype‐related AD risk effect (βstd) on GM volume. Spearman's ρ and P‐values are shown in the left bottom corner of each plot. AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; FDR, false discovery rate; GM, gray matter; LH, left hemisphere; RH, right hemisphere

We then compared these results to those ones from dose‐dependent effect of the ε2 allele, to investigate whether the GM volume effects related to the risk of AD are only due to the ε4 allele or may also be due to the ε2 allele. We found significant negative correlations for the dominant ε2 allele effect (ρ = –0.35, P = 0.004) and the additive ε2 effect (ρ = –0.27, P = 0.028), indicating opposite effects of the ε2 allele (i.e., protective) and the APOE genotype‐related AD risk (i.e., deleterious). No significant correlations were observed for the recessive ε2 effect (ρ = –0.13, P = 0.275, Figure 4B).

4. DISCUSSION

In this multi‐cohort study, we investigated genotypic and dose‐dependent effects of the ε2 allele on GM volumes in late‐/middle‐aged cognitively unimpaired individuals. As hypothesized, we found that the ε2 allele was associated with larger GM volumes in brain areas relevant for AD. However, the dose‐dependent effect of this allele was distinct for different areas. Regions typically affected by AD‐related neurodegeneration were similarly protected by the carriership of at least one ε2 allele, regardless of their load. On the other hand, areas related with cognitive maintenance presented larger volumes in relation with the dose (i.e., number) of this allele. In particular, APOE ε2 homozygotes, but not APOE ε2 heterozygotes, showed larger GM volumes than APOE ε3 homozygotes in the resilience signature. This was further supported by the dose‐dependent effects analyses, in which we found a trend to significance in the additive model for the ε2 allele, in the resilience but not in the AD signature. Finally, the effect of this protective allele seemed to be spatially related to that of an AD risk measure including all APOE genotypes, suggesting that the ε2 allele plays an opposing effect to that of the ε4 allele on GM volumes.

Our findings extend previous studies showing that having at least one ε2 allele confers larger GM volumes in areas known to be affected in AD. 13 , 14 , 15 For instance, the effect of the ε2 carriership on entorhinal volume has previously been observed in cognitively unimpaired individuals, 13 , 15 as well as in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD dementia. 34 A stepwise difference (ɛ2 carriers > ɛ3/ɛ3 individuals > ɛ4 carriers) in cortical thickness in the entorhinal cortex was also found in children and adolescents. 35 Further, our results together with a previous study with Aβ‐positive subjects suggest that this protective effect of the ɛ2 allele in the MTL, and more specifically in the parahippocampus, may be more pronounced in the right hemisphere. 16

In our study we also expand previous findings to regions related with cognitive resilience. 21 , 36 This result suggests that the well‐known low risk of cognitive decline in ε2 carriers may not only be due to a low risk of accumulating Aβ 4 and tau 37 pathologies (i.e., resistance to AD pathology), but also to preserved brain integrity in areas that are associated with greater resilience to, or capacity to cope with AD pathology. 21 A contribution of our study is that we demonstrated that the protective effect on these areas was particularly related to the homozygosity of the ε2 allele. Greater GM volume in areas related to cognitive resilience may also explain why the oldest old ε2 carriers could remain clinically non‐demented even when displaying elevated AD pathology. 17 , 18 With these results in mind, we propose that the increased brain reserve found in ε2 carriers, and especially in ε2 homozygotes, may promote their maintained cognitive functions, even in the rare case of developing AD pathology.

The unique design of our study allowed us to study the ε2 allele effects on GM volume in more detailed ways than previous studies. More specifically, we found that carrying one ε2 allele always seemed to confer an advantage compared to ε3 homozygotes, even when an ε4 allele is also present, although this last result did not survive the adjustment for multiple comparisons. Moreover, our results suggest that having an extra copy of the ε2 allele did not translate into a major gain in areas usually related to neurodegeneration, but it did on resilience areas. Thus, suggesting that carrying one ε2 allele may be sufficient to prevent or decrease AD‐related neurodegeneration, maybe in part through lowering AD pathology levels. However, adding an extra copy of the ε2 allele may not be beneficial for GM integrity in these areas, which may be related to the increased risk of APOE ε2 carriers to having cerebrovascular problems. 16 On the other hand, being ε2 homozygote increased brain reserve in areas related to cognitive resilience, which may in turn delay their cognitive decline and explain their higher survival rate without AD dementia. 3 Altogether, our results highlight that comparing all ε2 genotypic groups is superior to merging all ε2 carriers, when it comes to disentangling the specific effect of the ε2 allele and advance our understanding of its protective effects. 3 This accomplishment was an advantage of our large multi‐cohort design that has not been possible in previous single‐center studies.

Finally, we investigated the effect of a measure capturing the risk of AD due to the APOE genotype (i.e., APOE genotype‐related AD risk) on GM volumes and compared it to dose‐dependent effects of the ε2 allele. As hypothesized, higher APOE genotype‐related AD risk conferred smaller GM volumes both in areas targeted by AD pathology and areas related with brain resilience. 19 , 20 , 21 This finding is important and extends previous reports on the APOE ε4 allele 5 , 38 , 39 to now also incorporate the effect of the APOE ε2 allele. Our results suggest that carrying at least one ε2 allele contributed to this effect. The reason the recessive effects of the ε2 allele are not associated with those of the APOE genotype‐related AD risk may be related to its corresponding upstream mechanisms. While the APOE genotype‐related AD risk may show more important effects on AD‐neurodegeneration areas, 19 which may be partially due to Aβ and tau deposition effects, ε2 homozygotes showed a more pronounced effect on areas of cognitive resilience not typically associated with pathology, which may come from developmental characteristics.

The potential underlying mechanisms for the larger GM volumes in APOE ε2 carriers are unknown and they deserve further research. However, previous studies suggested that these mechanisms may involve both Aβ‐dependent and ‐independent pathways. 11 APOE ε2 carriers produce the APOE ε2 isoform, which is not only beneficial in terms of Aβ production, aggregation, and clearance, 40 , 41 but also protects against Aβ toxicity through a reduction of its oligomerization. 42 Therefore, by avoiding Aβ pathology, late‐/middle‐aged APOE ε2 homozygotes may be relatively spared of Aβ‐related effects on GM volume, particularly compared to ε4 carriers. In addition, the APOE ε2 isoform has also shown Aβ‐independent effects that may explain our current results. For instance, the APOE ε2 isoform promotes synaptic integrity, facilitates anti‐oxidant and anti‐inflammatory activity, and may mediate neuronal growth through a more efficient lipid and cholesterol metabolism (see Liu et al., 2 Li et al., 11 Suri et al., 40 and Yamazaki et al. 41 for detailed reviews). Altogether, these mechanisms may induce better neuronal health throughout the full lifespan and may partially explain the observed larger GM volumes in APOE ε2 carriers.

The multi‐cohort nature of our study is not free from limitations. First, not all participants in this sample had biomarkers of AD pathology available, which prevented us from investigating whether lower GM volume in the AD signature is in fact related to AD pathology. However, the extremely low prevalence of Aβ pathology in cognitively unimpaired APOE ε2 carriers suggests that the impact of this limitation is minor on the observed ε2 effects, which constitute the main focus of our work. 3 , 43 Second, to maximize the number of APOE ε2/ε2 individuals we pooled MRI data from different scanners, which may have introduced bias related to scanner‐specific features such as geometric distortion and tissue contrast. We minimized this issue by a strict control of several factors, at two levels. At the study design level, we strictly matched the six APOE genotype groups in terms of MRI scanner/protocol, in addition to our matching for age, sex, and years of education. In addition to this control at the design level, we conducted another correction at the statistical level, to remove the potential residual confounding effect of all these variables, including the MRI scanner/protocol. Therefore, these variables are unlikely to affect our current results in a significant manner. Third, the criterion for “normal cognition” was similar but varied slightly across cohorts. Nonetheless, all the cohorts used criteria commonly applied in clinical routine and in aging research.

In conclusion, in late‐/middle‐aged cognitively unimpaired individuals, the APOE ε2 allele is associated with larger GM volume in AD‐related brain regions. However, distinct dose‐dependent effects of this allele were observed in different areas of the brain. It is important to note that APOE ε2 homozygotes had a specific protective effect in areas related to cognitive resilience. Furthermore, APOE ε2 effects on GM volumes were similar, but opposed, to those related to the APOE ε4 genotypes. Altogether, our large multi‐cohort data advocates for increased brain reserve in APOE ε2 carriers, especially in ε2 homozygotes, which may in turn confer them additional protection against AD‐related cognitive decline, independent of the well‐known effects of APOE on Aβ.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

JLM is currently a full‐time employee of Lundbeck and priorly has served as a consultant or at advisory boards for the following for‐profit companies, or has given lectures in symposia sponsored by the following for‐profit companies: Roche Diagnostics, Genentech, Novartis, Lundbeck, Oryzon, Biogen, Lilly, Janssen, Green Valley, MSD, Eisai, Alector, BioCross, GE Healthcare, ProMIS Neurosciences. HZ has served on scientific advisory boards for Alector, Denali, Roche Diagnostics, Wave, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Pinteon Therapeutics, and CogRx; has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Alzecure, and Biogen; and is a co‐founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (outside submitted work). KB has served as a consultant, on advisory boards, or on data monitoring committees for Abcam, Axon, Biogen, JOMDD/Shimadzu. Julius Clinical, Lilly, MagQu, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, and Siemens Healthineers, and is a co‐founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program. GK is a full‐time employee of Roche Diagnostics GmbH. IS is a full‐time employee and shareholder of Roche Diagnostics International Ltd. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Gemma Salvadó and Daniel Ferreira contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results, and to the writing of the manuscript. Grégory Operto, Irene Cumplido‐Mayoral, Raffaele Cacciaglia, Carles Falcon, and Colin Groot contributed to analysis of the results. Eider M. Arenaza‐Urquijo, Natàlia Vilor‐Tejedor, Rik Ossenkoppele, and José Luis Molinuevo aided in interpreting the results and worked on the manuscript. Wiesje M. van der Flier, Frederik Barkhof, Philip Scheltens, Rik Ossenkoppele, Silke Kern, Anna Zettergren, Ingmar Skoog, Jakub Hort, Erik Stomrud, Danielle van Westen, Oskar Hansson, José Luis Molinuevo, Lars‐Olof Wahlund, Eric Westman, and Juan Domingo Gispert contributed to sample preparation. Eric Westman and Juan Domingo Gispert contributed to the design and implementation of the research. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication is part of the ALFA study (ALzheimer and FAmilies). The authors would like to express their most sincere gratitude to the ALFA project participants, without whom this research would have not been possible. Collaborators of the ALFA study are: Annabella Beteta, Alba Cañas, Marta Crous‐Bou, Carme Deulofeu, Ruth Dominguez, Maria Emilio, Karine Fauria, José M. González de Echevarri, Oriol Grau‐Rivera, Laura Hernandez, Gema Huesa, Jordi Huguet, Paula Marne, Tania Menchón, Marta Milà‐Alomà, Albina Polo, Sandra Pradas, Aleix Sala‐Vila, Gonzalo Sánchez‐Benavides, Anna Soteras, Marc Suárez‐Calvet, Marc Vilanova.

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI; National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH‐12‐2‐0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie; Alzheimer's Association; Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Data used in pre‐creation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp‐content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf). The project leading to this study has received funding from “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434), under the agreement LCF/PR/GN17/50300004. Additional support has been received from the Universities and Research Secretariat, Ministry of Business and Knowledge of the Catalan Government under the grant number 2017‐SGR‐892. EMAU is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities–Spanish State Research Agency (RYC2018‐026053‐I). FB is supported by NIHR biomedical research centre at UCLH. IS is supported by the Swedish Research Council (2019‐02075), Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Wellfare, Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils, the ALF‐agreement (ALF 716681, ALFGBG‐81392, ALFGBG‐771071), Alzheimerfonden, and Hjärnfonden. DF, LOW, and EW are supported by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SSF); the Strategic Research Programme in Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet (StratNeuro); the Swedish Research Council (VR, 2016‐02282); the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet; Center for Innovative Medicine (CIMED); the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation; the Swedish Brain Foundation; the Åke Wiberg Foundation; Demensfonden; Stiftelsen Olle Engkvist Byggmästare; and Birgitta och Sten Westerberg; Funding for Research from Karolinska Institutet; Funding for Geriatric Research from Karolinska Institutet; Stiftelsen Loo och Hans Ostermans; Stiftelsen Gun och Bertil Stohnes; and Stiftelsen Sigurd och Elsa Goljes Minne. JDG is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, and Competitiveness (RYC‐2013‐13054). OH and the BioFINDER study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2016‐00906), the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation (2017‐0383), the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg foundation (2015.0125), the Strategic Research Area MultiPark (Multidisciplinary Research in Parkinson's disease) at Lund University, the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (AF‐939932), the Swedish Brain Foundation (FO2019‐0326), The Parkinson foundation of Sweden (1280/20), the Skåne University Hospital Foundation (2020‐O000028), Regionalt Forskningsstöd (2020‐0314), and the Swedish federal government under the ALF agreement (2018‐Projekt0279).

Salvadó G, Ferreira D, Operto G, et al. The protective gene dose effect of the APOE ε2 allele on gray matter volume in cognitively unimpaired individuals. Alzheimer's Dement. 2022;18:1383–1395. 10.1002/alz.12487

Gemma Salvadó and Daniel Ferreira contributed equally to this study.

Eric Westman and Juan Domingo Gispert contributed equally to this study.

The complete list of collaborators of the ALFA Study can be found in the Acknowledgments section.

Contributor Information

Eric Westman, Email: eric.westman@ki.se.

Juan Domingo Gispert, Email: jdgispert@barcelonabeta.org.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer's disease: pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:333‐344. 10.1038/nrn2620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein e and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:106‐118. 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reiman EM, Arboleda‐Velasquez JF, Quiroz YT, et al. Exceptionally low likelihood of Alzheimer's dementia in APOE2 homozygotes from a 5,000‐person neuropathological study. Nat Commun. 2020;11:667. 10.1038/s41467-019-14279-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reiman EM, Chen K, Liu X, et al. Fibrillar amyloid‐beta burden in cognitively normal people at 3 levels of genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6820‐6825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cacciaglia R, Molinuevo JL, Falcón C, et al. Effects of APOE ‐ε4 allele load on brain morphology in a cohort of middle‐aged healthy individuals with enriched genetic risk for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2018:1‐11. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reiman EM, Chen K, Alexander GE, et al. Correlations between apolipoprotein E ε4 gene dose and brain‐imaging measurements of regional hypometabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8299‐8302. 10.1073/pnas.0500579102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stern Y, Arenaza‐Urquijo EM, Bartrés‐Faz D, et al. Whitepaper: defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimer's Dement. 2018:1305‐1311. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta‐analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;278:1349‐1356. 10.1001/jama.278.16.1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grothe MJ, Villeneuve S, Dyrba M, Bartrés‐Faz D, Wirth M. Multimodal characterization of older APOE2 carriers reveals selective reduction of amyloid load. Neurology. 2017;88:569‐576. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salvadó G, Grothe MJ, Groot C, et al. Differential effects of APOE‐ε2 and APOE‐ε4 alleles on PET‐measured amyloid‐β and tau deposition in older individuals without dementia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(7):2212‐2224. 10.1007/s00259-021-05192-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li Z, Shue F, Zhao N, Shinohara M, Bu G. APOE2: protective mechanism and therapeutic implications for Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2020;15:1‐19. 10.1186/s13024-020-00413-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khan W, Giampietro V, Ginestet C, et al. No differences in hippocampal volume between carriers and non‐carriers of the ApoE ε4 and ε2 alleles in young healthy adolescents. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:37‐43. 10.3233/JAD-131841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fan M, Liu B, Zhou Y, Zhen X, Xu C, Jiang T. Cortical thickness is associated with different apolipoprotein E genotypes in healthy elderly adults. Neurosci Lett. 2010;479:332‐336. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.05.092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alexopoulos P, Richter‐Schmidinger T, Horn M, et al. Hippocampal volume differences between healthy young apolipoprotein e ε2 and ε4 carriers. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2011;26:207‐210. 10.3233/JAD-2011-110356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fennema‐Notestine C, Panizzon MS, Thompson WR, et al. Presence of ApoE ε4 allele associated with thinner frontal cortex in middle age. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2011;2:77‐88. 10.3233/978-1-60750-793-2-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Groot C, Sudre CH, Barkhof F, et al. Clinical phenotype, atrophy, and small vessel disease in APOEε2 carriers with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2018;91:e1851‐9. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berlau DJ, Corrada MM, Head E, Kawas CH. ApoE ε2 is associated with intact cognition but increased Alzheimer pathology in the oldest old. Neurology. 2009;72:829‐834. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343853.00346.a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berlau DJ, Kahle‐Wrobleski K, Head E, Goodus M, Kim R, Kawas C. Dissociation of neuropathologic findings and cognition: case report of an apolipoprotein E epsilon2/epsilon2 genotype. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1193‐1196. 10.1001/archneur.64.8.1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, et al. Different definitions of neurodegeneration produce similar amyloid/neurodegeneration biomarker group findings. Brain. 2015;138:3747‐3759. 10.1093/brain/awv283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dickerson BC, Bakkour A, Salat DH, et al. The cortical signature of Alzheimer's disease: regionally specific cortical thinning relates to symptom severity in very mild to mild AD dementia and is detectable in asymptomatic amyloid‐positive individuals. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:497‐510. 10.1093/cercor/bhn113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arenaza‐Urquijo EM, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TL, et al. The metabolic brain signature of cognitive resilience in the 80+: beyond Alzheimer pathologies. Brain. 2019;142:1134‐1147. 10.1093/brain/awz037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferreira D, Hansson O, Barroso J, et al. The interactive effect of demographic and clinical factors on hippocampal volume: a multicohort study on 1958 cognitively normal individuals. Hippocampus. 2017;27:653‐667. 10.1002/hipo.22721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Molinuevo JL, Gramunt N, Gispert JD, et al. The ALFA project: a research platform to identify early pathophysiological features of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's. Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2016;2:82‐92. 10.1016/j.trci.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Amsterdam dementia cohort: performing research to optimize care. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2018;62:1091‐1111. 10.3233/JAD-170850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Slot RER, Verfaillie SCJ, Overbeek JM, et al. Subjective Cognitive Impairment Cohort (SCIENCe): study design and first results. Alzheimer's Res Ther. 2018;10:1‐13. 10.1186/s13195-018-0390-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rydberg Sterner T, Ahlner F, Blennow K, et al. The Gothenburg H70 Birth cohort study 2014‐16: design, methods and study population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34:191‐209. 10.1007/s10654-018-0459-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marcus DS, Wang TH, Parker J, Csernansky JC, Morris JC, Buckner RL. Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS): longitudinal MRI data in nondemented and demented older adults. J Cogn Neurosci. 2007;19:1498‐1507. 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.9.1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simmons A, Westman E, Muehlboeck S, et al. The AddNeuroMed framework for multi‐centre MRI assessment of Alzheimer's disease: experience from the first 24 months. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:75‐82. 10.1002/gps.2491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sheardova K, Vyhnalek M, Nedelska Z, et al. Czech Brain Aging Study (CBAS): prospective multicentre cohort study on risk and protective factors for dementia in the Czech Republic. BMJ Open. 2019;9:1‐8. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968‐980. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Insel PS, Hansson O, Mattsson‐Carlgren N. Association between apolipoprotein E ε2 vs ε4, age, and β‐Amyloid in adults without cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol. 2020;02:4‐10. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.3780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clarke GM, Anderson CA, Pettersson FH, Cardon LR, Morris AP, Zondervan KT. Basic statistical analysis in genetic case‐control studies. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:121‐133. 10.1038/nprot.2010.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ossenkoppele R, Schonhaut DR, Schöll M, et al. Tau PET patterns mirror clinical and neuroanatomical variability in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2016;139:1551‐1567. 10.1093/brain/aww027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu Y, Paajanen T, Westman E. APOE ε2 allele is associated with larger regional cortical thicknesses and Volumes. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30:229‐237. 10.1159/000320136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shaw P, Lerch JP, Pruessner JC, et al. Cortical morphology in children and adolescents with different apolipoprotein E gene polymorphisms: an observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:494‐500. 10.1016/S1474-4422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sun FW, Stepanovic MR, Andreano J, Barrett LF, Touroutoglou A, Dickerson BC. Youthful brains in older adults: preserved neuroanatomy in the default mode and salience networks contributes to youthful memory in superaging. J Neurosci. 2016;36:9659‐9668. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1492-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shi Y, Yamada K, Liddelow SA, et al. ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau‐mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature. 2017;549:523‐527. 10.1038/nature24016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Honea Ra, Vidoni E, Harsha A, Burns JM. Impact of APOE on the healthy aging brain: a Voxel‐based MRI and DTI study. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2009;18:553‐564. 10.3233/JAD-2009-1163.Impact [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alexander GE, Bergfield KL, Chen K, et al. Gray matter network associated with risk for Alzheimer's disease in young to middle‐aged adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2723‐2732. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Suri S, Heise V, Trachtenberg AJ, Mackay CE. The forgotten APOE allele: a review of the evidence and suggested mechanisms for the protective effect of APOE e2. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:2878‐2886. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yamazaki Y, Zhao N, Caulfield TR, Liu CC, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:501‐518. 10.1038/s41582-019-0228-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hashimoto T, Serrano‐Pozo A, Hori Y, et al. Apolipoprotein E, especially apolipoprotein E4, increases the oligomerization of amyloid β peptide. J Neurosci. 2012;32:15181‐15192. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1542-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jansen WJ, Ossenkoppele R, Knol DL, et al. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta‐analysis. JAMA ‐ J Am Med Assoc. 2015;313:1924‐1938. 10.1001/jama.2015.4668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.