Abstract

Consumers of mental health services experience poor physical health compared to the general population, leading to long‐term physical illness and premature death. Current research and policy activity prioritizes the physical health of consumers yet few of these recommendations have translated to practice. This implementation gap may be influenced by the paucity of literature exploring consumer perceptions and experiences with physical healthcare and treatment. As a result, little is understood about the views and attitudes of consumers towards interventions designed to improve their physical health. This integrative review aims to explore the literature regarding consumer perspectives of physical healthcare and, interventions to improve their physical health. A systematic search was undertaken using (i) CINAHL, (ii) MEDLINE, (iii) PsycINFO, (iv) Scopus, and (v) Google Scholar between September and December 2021. Sixty‐one papers comprising 3828 consumer participants met the inclusion criteria. This review found that consumers provide invaluable insights into the barriers and enablers of physical healthcare and interventions. When consumers are authentically involved in physical healthcare evaluation, constructive and relevant recommendations to improve physical healthcare services, policy, and future research directions are produced. Consumer evaluation is the cornerstone required to successfully implement tailored physical health services.

Keywords: consumer, experience, physical healthcare, psychiatric

Background

An estimated 20% of the global population is diagnosed with a mental illness (MI) (Steel et al. 2014; World Health Organization 2001) such as anxiety, depression, substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. MI is defined as diagnosable mental, behavioural, or emotional disorders resulting in substantial impairment of social, emotional, and occupational functioning (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics & Quality 2018) and each disorder varies in severity (RANZCP 2016). For the purpose of this review, and consistent with the language of Australian mental health policy, the term ‘consumer’ will be used to reference any person diagnosed with a clinically defined high or low prevalence disorder MI (Lyon & Mortimer‐Jones 2020). Moreover, reflecting the inclusivity of differing perspectives regarding the diagnosis of MI in policy and for consumers, this review will collectively refer to all people diagnosed with a MI rather than a specific diagnosis (Perkins et al. 2018). People diagnosed with MI are at greater risk of experiencing adverse physical health outcomes such as higher morbidity and premature mortality up to 30 years compared to the general population (De Hert et al. 2011; Department of Health 2017; Dickerson et al. 2018; Firth et al. 2019; Lawrence et al. 2013). Although 17% of this early mortality can be attributed to suicide, the majority of premature deaths are consistently attributed to poor physical health (De Hert et al. 2011; Dickerson et al. 2018; Firth et al. 2019). Within the Australian context, up to three‐quarters of premature deaths for people diagnosed with a MI were attributed to physical comorbidities (De Hert et al. 2011; Edmunds 2018; Lawrence et al. 2013; Oakley et al. 2018).

Prevalent physical health comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) (29.9%), respiratory disease (23.6%), and cancer (13.5%) (Dickerson et al. 2018; Lawrence et al. 2013) have consistently been reported as contributors to premature mortality. Metabolic syndrome; the clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors such as hypertension, elevated triglyceride levels, and central adiposity (Alberti et al. 2009; Oakley et al. 2018), account for 50% of the physical health comorbidities present in people diagnosed with MI, specifically schizophrenia (Edmunds 2018). Multimorbidity (the presence of multiple cardiovascular risk factors) is strongly associated with modifiable lifestyle‐related factors including obesity, cigarette smoking, physical inactivity, nutritional inadequacies, and side effects related to pharmacological treatment (De Hert et al. 2011; Morgan et al. 2014; Oakley et al. 2018; Vancampfort et al. 2015).

Complicating the risk factors for developing physical comorbidities are the negative or deficit symptoms of the MI, and adverse drug reactions (ADRs) (Curtis et al. 2012; Department of Health 2017; Firth et al. 2019; Morgan et al. 2012, 2014; Oakley et al. 2018). Negative symptoms deteriorate the consumers' social, occupational, and emotional functioning capacity and impede the physical and mental health recovery process (Department of Health 2017; Morgan et al. 2014). Cardiometabolic, endocrine, and neuromotor complications such as weight gain, hyperprolactinaemia, and extrapyramidal side effects can arise from ADRs (Firth et al. 2019). In combination, the severity of illness and ADRs associated with antipsychotic medications increase the risk of physical health morbidity and early mortality (Edmunds 2018; Firth et al. 2019; Oakley et al. 2018).

Efforts to minimize antipsychotic medication‐related ADRs and modifiable risk factors for metabolic syndrome led to the development of a positive cardiometabolic health algorithm (Curtis et al. 2012). The framework provides a guideline for metabolic screening, prevention, and early interventions, prompting review, and rationalization of polypharmacy, and implementation of healthy lifestyle behaviours to curb weight gain (Curtis et al. 2012). Despite growing evidence supporting the regular physical health monitoring and assessment of people diagnosed with a MI, implementation of these guidelines remains problematic (Clancy et al. 2019; Happell et al. 2013; McKenna et al. 2014; RANZCP 2015, 2016; Taylor & Shiers 2016) and growing concerns remain regarding the projected twofold increase in cardiometabolic risk factors for people diagnosed with MI (Charlson et al. 2018; Firth et al. 2019; Morgan et al. 2014; Oakley et al. 2018).

Compounding the effects of lifestyle factors and ADRs are systemic inadequacies in health service provision directed to improve physical healthcare. Stigma from health professionals, and diagnostic overshadowing contributes to the dismissal of reported physical health concerns as somatic complaints, which potentially leads to the increased withdrawal from accessing services for physical health issues (Duggan et al. 2020; Edmunds 2018; McCloughen et al. 2016). Diagnostic overshadowing occurs when a consumers' diagnosis of MI is prioritized despite presenting with a physical health concern (Ewart et al. 2016; Nash 2013; Oakley et al. 2018). Moreover, a lack of clear allocation of roles and responsibilities among healthcare professionals results in inadequate physical healthcare practices and hinders quality care necessary to address physical health issues for consumers (Clancy et al. 2019; Ewart et al. 2016; Happell et al. 2016a, 2016b, 2016c; Morgan et al. 2012; Oakley et al. 2018). These shortcomings in service provision mean people diagnosed with a MI, such as schizophrenia, experience a disparity in physical healthcare that borders on a violation of human rights (Edmunds 2018).

The physical health of consumers and the healthcare disparities they face is prioritized in current research and policy activity (Clancy et al. 2019; Department of Health 2017; Ewart et al. 2016). Studies consistently suggest the need to move beyond defining the problem to implementing high standard evidence‐based physical healthcare (Clancy et al. 2019; Ewart et al. 2016; McCloughen et al. 2016). To date, few of these recommendations have translated to practice, partly due to the paucity of literature exploring consumer perceptions of the physical healthcare they receive (Ewart et al. 2016; Morse et al. 2019).

Previous reviews synthesized the scarce literature exploring consumer perspectives about their physical health and perceived barriers to optimal physical health and healthcare (Chadwick et al. 2012; Happell et al. 2012a, 2012b). These reviews have provided insight into the barriers consumers experience. For example, consumers reported diagnostic overshadowing, inconsistent approaches to screening or addressing their physical health needs, and poor or stigmatizing attitudes from health professionals (Chadwick et al. 2012; Happell et al. 2012a, 2012b). Understanding the consumers' views on barriers to accessing physical healthcare services, reveals the individual and systemic issues health services need to address.

Less still is understood about the views and attitudes of consumers towards physical health interventions targeted to improve their physical health. It is nearly 10 years since the reviews of Chadwick et al. (2012), Happell et al. (2012a), and Happell et al. (2012b) have been published. Since then, it appears no reviews have been conducted to explore consumers' perceptions about physical health or the physical healthcare they receive. Attention needs to be placed on consumer views about the physical healthcare they receive to enable consumer autonomy, supported decision making and tailoring of services to their needs. Urgent calls to conduct more research providing consumers a voice to generate strategies to improve services and outcomes is warranted (Department of Health 2017; Ewart et al. 2016; Morse et al. 2019; Small et al. 2017).

Aim

This integrative review aims to explore how consumers view their physical health and experience of the physical healthcare they receive by questioning:

What are the perspectives of mental health consumers regarding:

physical health; and

interventions to improve their physical health?

Findings from this review will contribute to the growing knowledge about consumers' perception of physical healthcare and produce results that will inform the development of consumer centred physical healthcare services, policy, and research directions.

Methods

Literature review method

The Cochrane, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and Prospero databases were searched to identify whether similar reviews regarding consumer views and attitudes on physical health and physical health interventions existed. Three reviews synthesizing literature pre‐2012 were found, however, they only explored the consumer view regarding physical health (Chadwick et al. 2012; Happell et al. 2012a, 2012b). Since 2012, no reviews exploring the consumer perspectives of physical healthcare were identified. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, this will be the first integrative review to summarize the literature on this topic.

An integrative approach was considered appropriate because it allows for the consolidation and comparison of diverse primary research methods (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Integrative reviews provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon through the critical appraisal and analysis of past experimental and non‐experimental research, and theoretical literature (Hopia et al. 2016; Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Guided by methods described by Cooper (1998), the present integrative review (i) formulated a research question, (ii) searched the literature, (iii) evaluated the data, (iv) analysed and integrated the outcomes of the studies, and (v) presents the results (Hopia et al. 2016; Whittemore & Knafl 2005).

Search strategy

The review scope primarily explored the views and attitudes of consumers. However, carers and clinicians were included in the search. Studies on the physical health of people diagnosed with MI tend to explore the views of multiple populations or focus on clinicians with an addition of the consumer and carer population. For this reason, a threefold literature search strategy was developed to ensure consumer views were extracted from studies where they may not be the primary focus. A Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome (PICO) structure was implemented where the Population comprised consumers, carers, and health professionals; the Intervention included any physical health‐related intervention; the Comparator was any or no intervention; and the Outcome was the experience or perception of the included population.

The search was conducted using the following five databases: (i) CINAHL, (ii) MEDLINE, (iii) PsycINFO, (iv) Scopus, and (v) Google Scholar, using keywords and MESH terms, combined using Boolean operators. The search strategy is shown in Table 1. The reference lists of the included studies were hand‐searched for additional relevant studies. The search was conducted between September and December 2021 and date‐limited to include studies published since 2005 because physical healthcare for consumers was increasingly being prioritized in research (Fogarty & Happell 2005; Happell et al. 2012a, 2012b; Oakley et al. 2018). Therefore, to ensure the integrity of this review, studies since 2005 were thoroughly searched and reviewed for inclusion. Search terms were guided by previous literature reviews on physical health and current literature on physical healthcare for people diagnosed with MI.

Table 1.

Search terms

| PICO | Key words | MeSH terms, Search Terms, and Boolean operators |

|---|---|---|

| P |

Mental health consumers Carers Mental health professionals |

psychiatr* AND patient* OR consumer* OR service user OR mental health consumer OR mental health AND (carer* OR family) OR mental health nurs* OR psychiatric nurs* OR mental health AND (nurs* OR clinician OR health professional) |

| I |

Physical health Physical healthcare |

physical healthcare OR physical health intervention OR physical health nurse OR physical health nurse consultant OR cardiometabolic health nurse OR physical health AND (care OR intervention OR nurse) OR physical health nurse consultant OR cardiometabolic health nurse |

| C | C‐any or no intervention | |

| O | Experience or perception | Experience OR perception OR attitude OR view OR feeling OR opinion or qualitative study |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were screened if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) studies exploring physical health‐related interventions for any mental health consumer in a primary, secondary or tertiary settings, (ii) published in the English language, (iii) peer‐reviewed between 2005 and present, and (iv) published original research exploring the perspectives and experiences of consumers. Studies that met the above inclusion criteria were eligible for inclusion in the review. The review excluded publications not written in English, focusing on clinicians or carers only, theoretical and non‐peer‐reviewed literature.

Study quality appraisal

Extracting specific methodological features of primary studies is recommended to evaluate overall study quality (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Depending on the research design, different criteria are applied to report study quality. Eligible qualitative studies were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative tool (see Table 2). The CASP qualitative tool was used because it is a commonly used tool that offers a comprehensive 10‐item checklist for assessing the methodological quality of a qualitative study. This comprehensive appraisal enables the reviewer to determine the relevance of including a paper in the review (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; Hopia et al. 2016). Descriptive quantitative and mixed‐method studies were appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (see Table 3). Historically, appraising the quality of studies of a different design has been challenging (Hong et al. 2018); however, the MMAT offers the flexibility and algorithmic assistance to choose the set(s) of quality criteria to use for multiple study designs (Hong et al. 2019). Mixed methods and quantitative descriptive study criteria were chosen to appraise the quality of quantitative and mixed‐method studies of various designs (Hong et al. 2018).

Table 2.

Qualitative study quality appraisal (CASP)

| Author | Clear statement of the research aims | Qualitative methodology appropriate | Design appropriate to address research aims | Recruitment strategy appropriate research aims | Data collected in a way that addressed the research issue | Researcher and participant relationship adequately considered | Ethical issues considered | Data analysis rigorous | Clear statement of findings | Value of the research | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanner Kristiansen et al. (2015) † | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | U | High |

| Blomqvist et al. (2018) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Bocking et al. (2018) | + | + | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | + | High |

| Butler et al. (2020) † | + | + | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | + | High |

| Carson et al. (2016) † | + | + | + | + | U | ‐ | U | + | + | U | High |

| Chee et al. (2019) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Crone (2007) | + | + | U | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | U | High |

| Cullen and McCann (2015) | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | U | + | + | High |

| Ehrlich and Dannapfel (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | + | High |

| Erdner and Magnusson (2012) | + | + | U | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | U | High |

| Ewart et al. (2016) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Ewart et al. (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Fogarty and Happell (2005) | + | + | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | + | High |

| Gedik et al. (2020) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Glover et al. (2013) | + | + | U | U | + | ‐ | ‐ | U | + | U | Moderate |

| Graham et al. (2013) | U | U | U | U | + | ‐ | U | + | + | + | Moderate |

| Gray and Brown (2017) † | + | + | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | + | High |

| Happell et al. (2016a, 2016b, 2016c) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Happell et al. (2016a, 2016b, 2016c) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Happell et al. (2016a, 2016b, 2016c) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Happell et al. (2019) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Hassan et al. (2020) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Hemmings and Soundy (2020) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Ince and Günüşen (2018) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Ince et al. (2019) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Katakura et al. (2013) | + | + | + | U | + | ‐ | U | + | + | + | High |

| Matthews et al. (2021) † | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| McCloughen et al. (2016) | + | + | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | + | High |

| Nash (2014) | ‐ | + | + | U | + | U | + | + | + | + | High |

| Owens et al. (2010) † | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | + | High |

| Pals and Hempler (2018) | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | + | High |

| Park et al. (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | + | High |

| Patel et al. (2018) | + | + | + | + | U | ‐ | U | U | + | + | High |

| Pickard et al. (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Roberts and Bailey (2013) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Rollins et al. (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | High |

| Rönngren et al. (2018) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Rönngren et al. (2014) | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | + | High |

| Small et al. (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| van Hasselt et al. (2013) † | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Vazin et al. (2016) | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | + | High |

| Verhaeghe et al. (2013) † | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | + | High |

| Wardig et al. (2015) | + | + | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | + | High |

| Watkins et al. (2020) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Wheeler et al. (2018) † | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Wright‐Berryman and Cremering (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | ‐ | + | + | + | + | High |

| Young et al. (2017) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

Legend: + Condition achieved; ‐ Condition not achieved; U = unclear.

Quality 3 point scale: Low = 0–3.5 Moderate = 3.6–7 High = 7.1–10.

Study contains consumer and carer population.

Table 3.

MMAT Quality Appraisal – Qualitative, Quantitative Survey and Mixed Methods Study criteria

| Author | Are there clear research questions? | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | Is the sample representative of the target population? | Are the measurements appropriate? | Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed‐methods design to address the research question? | Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartlem et al. (2018) | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | + | + | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | High |

| Brimblecombe et al. (2019) † | + | + | U | U | U | + | U | + | U | U | ‐ | U | ‐ | + | ‐ | + | U | Moderate |

| Brown and O’Donoghue (2021) | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | + | + | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | High |

| Browne et al. (2016) † | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | `+ | + | + | U | ‐ | + | + | ‐ | + | High |

| Brunero and Lamont (2009) | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | + | + | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | High |

| Edmonds and Bremner (2007) | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | + | U | + | U | ‐ | + | + | + | + | U | High |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | U | + | U | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | High |

| Furness et al. (2020) | + | U | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Happell et al. (2014a, 2014b, 2014c) | ‐ | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | + | + | ‐ | U | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Moderate |

| Henning Cruickshank et al. (2020) | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | + | + | U | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | High |

| Kern et al. (2020) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | U | + | + | + | + | + | + | High |

| Mateo‐Urdiales et al. (2020) | + | + | + | U | U | U | U | + | + | U | U | U | + | + | + | U | U | High |

| Stanton et al. (2016) | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | + | + | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | High |

| Wheeler et al. (2018) | + | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | + | U | + | U | + | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | High |

Legend: + Condition achieved; ‐ Condition not achieved; U = unclear.

Quality 3 point scale: Quantitative descriptive studies: low = 0–2.32, moderate = 2.33–4.66, high = 4.67–7; Mixed methods studies: Low = 0–5.6 Moderate = 5.7–11.4 High = 11.5–17.

Study contains consumer and carer population.

A diverse presentation of primary studies may require quality assessment using various appraisal tools with different criteria. A 2‐point scale (low and high) to indicate the quality of a study and a discussion of the methodological limitations and strengths are recommended (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). During the quality appraisal, no studies were identified to be of low quality thus posing a challenge to determine moderate from high‐quality studies. Consistent with other flexible integrative review approaches to quality scoring, this review will use a 3‐point scale to distinguish moderate and high‐quality studies (Hopia et al. 2016).

Data extraction and analysis

The creation of a data matrix enables structured analysis of primary sources and supports the writing of a narrative synthesis (Toronto & Remington 2020). Eligible studies underwent an inductive process of ordering, coding similar phrases or patterns, and categorizing these codes (Toronto & Remington 2020; Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Information about the author, publication year, location (country), research setting, design, sample characteristics, aim, and study findings were extracted from full‐text papers.

Findings

Study characteristics

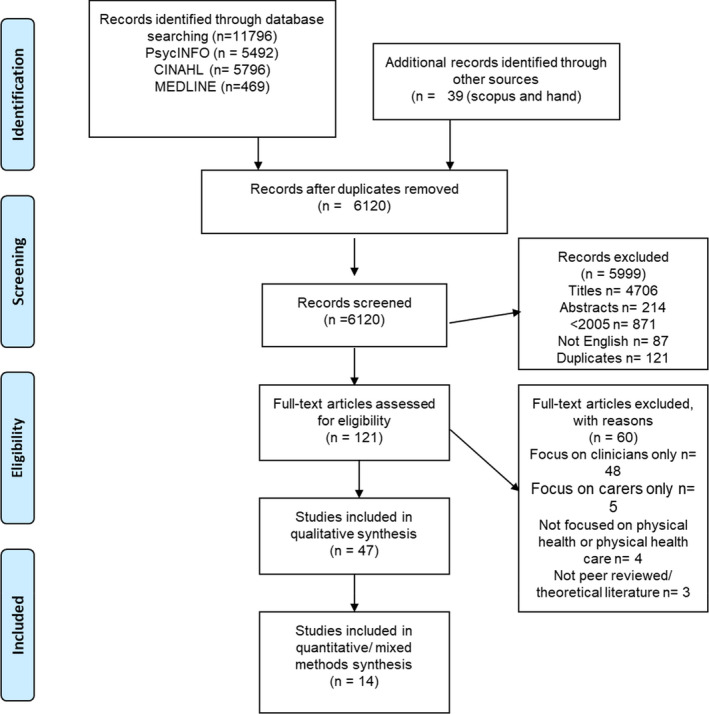

The literature search resulted in the inclusion of 61 papers comprising 3828 consumer participants (see Fig. 1). From the 61 papers, 46 focused on the consumer voice whilst 15 explored the dual perspectives of consumers and carers (n = 3), and consumers and clinicians (n = 12). Most papers were from Australasia (n = 25), followed by European (n = 14), United Kingdom (n = 14), and North American (n = 8) regions.

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram of literature search.

Study design, quality and synthesis

Most papers (n = 47) were qualitative studies, using exploratory, descriptive, and phenomenological approaches. Quantitative (n = 8) and mixed‐methods papers (n = 6) mainly comprised cross‐sectional surveys. Mostly high‐quality papers (n = 57) were included in this review, with only four papers assessed as moderate quality. Methodological strengths for all studies included clear articulation of research aims, methodology, and findings. Common omissions included lacking discussion regarding non‐response bias (n = 10), confounders (n = 9), relationship bias (n = 17), justification of recruitment strategy (n = 5), and information about the representativeness of included samples (n = 5). Despite these limitations and except for two qualitative studies, one cross‐sectional survey and a mixed‐methods study that were assessed as moderate quality, the overall quality of studies chosen for this integrative review was high. Table 4 presents a summary of the studies reviewed, the country and region where the study took place, study focus, setting, research design, sample characteristics, quality rating, and findings.

Table 4.

Study characteristics

| Authors | Country/region | Focus | Setting | Research design (data collection) | Sample characteristics | Quality rating | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartlem et al. (2018) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer interest in improving health risk behaviours and acceptance of advice on behaviour change |

Inpatient Six Acute Clinical Units (20–25 beds each) |

Cross‐sectional survey examining patient characteristics, health behaviour risk status, interest in changing health risk behaviours, and acceptability of clinical staff providing risk reduction advice Surveys administered as 15 min interviews by researchers |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 2075), 57% completion rate Men 55.8% Mean age: 41.5 |

High |

Almost all participants engaged in at least one health risk behaviour. 50% of participants self‐reported being at risk of all four behaviours Risk for inadequate nutrition prevalent Majority of participants at risk considered making a change to improve that behaviour Two‐thirds of smokers seriously consider reduction/cessation 80% indicated ‘agreed to strongly agree’ that it is acceptable to receive advice and support from inpatient staff |

| Blanner Kristiansen et al. (2015) | Denmark, Europe | Consumer and clinician view of physical health problems, causes, and prevention and treatment strategies | Three psychiatric out‐patient clinics |

Qualitative study Six focus groups (two at each site) |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 14) Women (n = 7) Clinicians (n = 19) |

High |

Physical health problems included weight issues; cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, poor physical shape, liver diseases, lung diseases, and dental issues Causes: lifestyle, mental illness and organizational issues Consumers were often very specific about the strategies to prevent and treat certain problems and causes to their poor health Clinicians were broader Consumer strategies: binding communities, engagement in physical activity |

| Blomqvist et al. (2018) | Sweden, Europe | Consumer experiences of enablers for healthy living | Three psychiatric community services |

Qualitative descriptive study Individual interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 18) Women (n = 18) Mean age: 50 |

High |

Consumers expressed the importance of holistic and person‐centred view such as having a daily structure for social and physical activity, a healthy diet, sufficient sleep Life events motivated health improvements such as disease in the family, coping with symptoms of mental illness, getting older, and physical illness, positive effects of changed unhealthy habits |

| Bocking et al. (2018) | Australia, Australasia | Consumers views regarding Peer Workers as an intervention improve their physical health | Consumer network, Community |

Qualitative exploratory study Four focus groups |

Convenience sampling Consumers (n = 31) |

High |

Peer worker potential and value can facilitate health promotion, advocacy, and assist with motivation Suggestion to expand the role of consumer organizations to co‐design services and communicate information Consumers preferred and described benefits of segregated activities as a segue to mainstream options |

| Brimblecombe et al. (2019) † | England, UK | Consumer and clinician views regarding the prospective use of eNEWS and to inform plan for implementation | Six inpatient units |

Mixed methods Self‐completed questionnaires Two group discussions |

Consumers (n = 26 surveys, 9 discussion) Clinicians (n = 82 survey, 10 discussion) |

High |

Consumers expressed concern about data confidentiality Staff were neutral or positive about eNEWS implementation however raised safety concerns |

| Brown and O’Donoghue (2021) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer attitudes and knowledge of tobacco smoking behaviours | Headspace and Orygen specialist service, Community | Cross‐sectional survey design administered in the waiting room |

Young people aged between 15 and 25 n = 114 Average age, 19.9 |

High |

56.3% reported ever smoking 75% (n = 36) thought they should quit in the future with only 23.5% planning to do in the next 30 days and 44.4% confident that they could successfully stop smoking |

| Browne et al. (2016) † | USA, North America | Consumer and clinician perspectives on exercise, barriers, incentives, and attitudes about walking groups | Community |

Mixed methods Walking group questionnaire Focus groups (n = 4) |

Consumers (n = 12) Women (n = 5) Mean age: 39.7 Clinicians‐social workers (n = 14) Women (n = 9) |

High |

Consumers recognizes physical health benefits but experience barriers that impede exercise participation, e.g., motivation and safety Walking viewed as the most accessible and favourable form of exercise and identified the potential benefits of exercising in a group for socialization by consumers and clinicians Clients identified enjoyment, positive impact on mood, alleviating symptoms, and associated health benefits as primary reasons for engaging in exercise Questionnaire response: most consumers perceived themselves as physically active compared to clinicians who did not perceive them as active |

| Brunero and Lamont (2009) | Australia, Australasia | Understand the relationship between physical health risk factors and consumer health behaviour beliefs |

Community Clozapine Clinic |

Cross‐sectional survey study European Health and Behaviours Survey and health outcomes |

Convenience sampling Consumers (n = 99), 60% response rate Men (n = 61) |

High |

Consumers had positive attitudes to health‐related behaviours whilst most of their clinical risk factors were well above normal parameters Alcohol consumption decreased with age Whilst there was an overall positive attitude towards their physical health, clearly, education programmes and awareness alone are not enough to affect health behaviours |

| Butler et al. (2020) † | England, UK | Explore the attitudes of Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) clinicians and patients experiencing severe mental illness towards physical healthcare and its provision | Early Intervention in Psychosis service, Community |

Qualitative study Interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 14) Men (n‐10) Clinicians (n = 15) |

High |

Patients were motivated to engage with the physical health check, but their awareness of physical health varied with some linking mental and physical health Patients engaged with the physical health checks because it was offered, they were proactive or motivated by the knowledge of CVD, therapeutic relationship Uncertainty in how physical healthcare should be provided |

| Carson et al. (2016) † | USA, North America | Clinician and consumers on the meaning of physical symptoms | Community |

Qualitative 30 video recordings of a series of mental health intake sessions and audio‐recorded post‐diagnostic research interviews |

Consumers (n = 30) Women (n = 15) Main physical health condition: long‐term pain (n = 11) |

High |

Consumers view physical illness in terms of what is at stake for them in their lives, e.g., existential loss, loss of agency, and embodiment of fragmentation affecting their lives due to illness Consumers were concerned about losing the capacity to work which affected engagement with mental health services Consumer expression and meaning‐making are influenced by the clinician's willingness to engage |

| Chee et al. (2019) | Australia, Australasia | Explore young consumers' level of knowledge and understanding of the impact of their psychosis on their overall health and well‐being and their physical health need, including interest in physical healthcare | Community |

Qualitative study Individual interviews |

Purposive and theoretical sampling Consumers (n = 24) Mean age: 26 Men (n = 22) |

High |

Initial response to dx of psychosis: low levels of health literacy and understanding on the linkage of mental and physical health, self‐stigma Focus of care: need medical treatment and support, physical issues low in priority as most viewed themselves as fit and healthy Needs: Lacking education about & adverse effects, antipsychotic medications, increasing awareness about the need for good physical health, social support in the community |

| Crone (2007) | England, UK | Consumers' perceived benefits and experience of participating in a walking group | Community |

Qualitative participatory research Individual interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 4) Women (n = 2) |

High |

Consumers were apprehensive and perceived the project prior to starting as a new and positive opportunity Factors affecting participation included benefits to be gained and challenges to be overcome The project was commended as being contemporary, intelligent, and flexible Perceived benefits and outcomes were enjoyment, socialization, knowledge, and appreciation of nature, purposeful activity, and sleep hygiene Experiences were mainly positive, memorable, and enjoyable |

| Cullen and McCann (2015) | Ireland, Europe | Consumer views of physical activity in relation to mental illness, recovery, quality of life | Community |

Qualitative exploratory and descriptive study Individual interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 10) Mean age: 44 |

High |

Physical activity viewed as an enjoyable, fun, and meaningful activity, with benefits such as endorphins Physical activity as a mental distraction, expanding social networks, and structured activities Quality of life and recovery: enjoying daily life, physical activity as part of recovery Challenges: being supported, trained gym instructors, mental health nurses, and barriers to physical activity |

| Edmonds and Bremner (2007) | England, UK | Evaluation of a smoking cessation training and views of consumers on one to one (1:1) support‐access, benefits, NRT, concerns about quitting, other support options | Community |

Stop smoking service training evaluation form Telephone interviews with staff 9 months after training Semi‐structured interviews with consumers |

Consumers (n = 12) Clinicians (n = 40) |

High |

10 out of 12 consumers quit smoking following the one‐to‐one stop smoking support at 4 weeks (verified by carbon monoxide reading) Two did not finish the course 7 consumers interviewed: ‐found the service accessible ‐individualized, personalized, and flexible support, personal qualities and interpersonal skills of advisor such as listening and positive approach, were useful ‐consumers had used at least 1 form of NRT, e.g., patches, inhaler |

| Ehrlich and Dannapfel (2017) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer's current experience with physical health and regarding professionals engaging them about their physical health | Community |

Qualitative Face‐to‐face individual semi‐structured interviews |

Consumers (n = 32) Women (n = 15) |

High |

Varying levels of inclusion and autonomy influenced consumers' ability to be active co‐producers of their physical health. Influences included: (1) the healthcare systems' fragmentation and continuity of care, relationship with the doctor and support from NGOs; (2) medication use, (3) being partners in care, (4) having control over life situations and managing health, and (5) self‐mastery and self‐management via a balance between mental and physical health |

| Erdner and Magnusson (2012) | Sweden, Europe |

Consumers' descriptions of their needs regarding activity and its importance for their health |

Community | Qualitative (inductive approach) | Consumers (n = 6) | High |

Consumers preferred getting control over one's life via creating structure and routine in their everyday life. Everyday activities included smoking, having a coffee, cleaning their home, jogging several times a week to walking daily. Exhaustion after activity was considered liberation and reduced anxiety Consumers expressed a need for contact with family and friends |

| Ewart et al. (2016) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer experience with physical healthcare systems | Community |

Qualitative exploratory study Four focus groups |

Consumers (n = 31) | High |

Consumers perceived there being a scarcity of physical healthcare, characterized by physical health problems being undetected and provider non‐responsiveness to those detected problems. Scarcity led to disempowerment that included the undermining of consumer self‐determination where they felt a sense of nowhere to turn to, and over time, worsening physical illness and worsening mental illness that could, and did, translate into physical health crises |

| Ewart et al. (2017) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer views of mental health services regarding their physical health and experiences of accessing physical healthcare services | Community |

Qualitative exploratory study Four focus groups |

Consumers (n = 31) | High |

Salience of social and economic and discriminatory conditions in mental health consumers' lives that had a considerable impact on both their physical and overall health Participants described the health system as contributing to worse health outcomes—where lack of communication about the side effects of psychiatric drugs, negative staff attitudes, and an overall lack of support were all concerns of consumers |

| Fogarty and Happell (2005) | Australia, Australasia | Determine the impact of a structured exercise program on the physical and psychological well‐being of consumers | Community | Three focus groups with consumers and clinicians (nursing and exercise physiologists) | Consumers (n = 6) | High |

Consumers preferred the individual nature of the program because it was positive, individually, and gradually increased exercises Consumers noticed a physical improvement in fitness and physical capacity Group dynamics where there was a team approach benefited consumers as they had a training partner for support and encouragement Consumers were keen to continue regular exercise, e.g., regular walks, playing squash to team sports |

| Fraser et al. (2015) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer attitudes towards physical activity and preferences | Inpatient, private hospital |

Cross‐sectional study Self‐administered written survey regarding interest in physical activity, reasons to do physical activity, general knowledge regarding the benefits of physical activity, preferences for type, context, and sources of support |

Consumers (n = 101, 57% response rate) | High |

77% of participants expressed a high interest in physical activity A high proportion of participants (≥95%) endorsed weight control, maintaining good health, managing stress, and improving emotional well‐being. The least endorsed reason was the social aspect A high proportion of participants (≥90%) agreed that physical activity was beneficial for managing psychological well‐being, heart disease, stress, diabetes, and quality of life Two‐thirds of the participants preferred physical activity that can be done alone, at a fixed time, and with a set routine and format The most commonly preferred physical activity type was walking Lack of energy, feeling too tired, and lack of motivation were the most commonly reported barriers to physical activity |

| Furness et al. (2020) | Australia, Australasia | Explore consumer perspectives on physical health‐focused NPC practices | Community |

Proof of concept mixed methods study (part of a larger study investigating physical health‐focused NPS roles in CMHS settings) Qualitative: Individual interviews Quantitative: eMR file review for socio‐demographic and clinical information |

Qualitative: Purposive sample Consumers (n = 10) Mean age: 41 Women (n = 6) Quantitative: NPC referred consumers (n = 15) |

High |

Consumers perceived the relationship with the NPC to be important and found them to be positive, helpful, and supportive Health promotion advice provided by the NPC was perceived as positive and helpful. Improvements in physical and mental health included weight loss; improved physical health symptoms such as lowered blood pressure, blood glucose levels, and cholesterol; and improved mood and social relationships |

| Gedik et al. (2020) | Turkey Europe | Consumers' ideas and experiences regarding their access to physical healthcare services | 30‐bed, adult psychiatric clinic in a university hospital in western Turkey |

Qualitative descriptive study Individual interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 14) Women (n‐9) Mean age: 41.78 |

High |

Barriers to access of physical healthcare: individual and illness, health workers rude attitudes, harsh response; health system (waiting times, crowded environment, economic difficulties) Facilitators: healthcare system facilitated the acquisition of disability card, family support Expectations for the healthcare system included faster and easier access and health workers to be accommodating, effective with communication, e.g., empathy and listening |

| Glover et al. (2013) | USA, North America | To document, analyse, and understand self‐identified barriers to exercise for consumers |

Community Psychiatric Rehabilitation Centres |

Qualitative Individual interviews |

Consumers (n = 31) | High | Barriers: side effects of psychiatric medications (lethargy), a focus on dealing with the symptoms of their mental illnesses, and the role of existing physical comorbidities |

| Graham et al. (2013) | Canada, North America | Explore the meaning of a healthy lifestyle for consumers and the barriers they experience to healthy living | Community |

Qualitative Focus groups |

Consumers (n = 23) Women (n = 14) Mean age: 44 |

High |

Consumer definition of healthy living included social support, e.g., friendship, secure affordable housing, voluntary or paid employment, social determinants of health (healthy eating, exercise, spiritual, and emotional health) Barriers to a healthy lifestyle included: mental and physical ill‐health, structural, social, and self‐stigma Proposed solutions included: innovative ideas for organizing peer support around cooking, food preparation, shopping, and exercise to help with motivation |

| Gray and Brown (2017) † | Scotland, UK | Examine and contrast, from both the consumer and clinician perspectives, the practice of MHN in promoting physical health in consumers | Community and inpatient |

Qualitative Individual interviews |

Convenience sampling Consumers (n = 15) Mental health nurses (n = 18) |

High |

Mental health nurses increasingly emphasized the importance of physical health for consumers however consumers believed it was not always a high priority, e.g., nurses too busy Physical health was included in care plans however consumers had low expectations that their physical health needs would be addressed Consumers complained that general hospital clinicians and GPs were circumspect towards them Medication side‐effects were common which impacted their sense of physical well‐being, and were frequently ignored by nurses Consumers valued physical and recreational activities because it kept them connected with ‘normal life’ and busy on the ward and in the community |

| Happell et al. (2014a, 2014b, 2014c) | Australia, Australasia | Investigate the knowledge and attitudes towards health behaviours of consumers | Community |

Quantitative descriptive Self‐report questionnaires on health status (1) Centres for Disease Control Health‐Related Quality of Life Questionnaire 4 (2) Australian Health Behaviour Knowledge and Attitudes Questionnaire |

Consumers (n = 21) Men (61.9%) |

High |

Majority (61.9%) of participants report their overall quality of life as either ‘Poor’ or ‘Fair’ with less than 5% of participants rating their health as ‘Very good.’ Prevalent physical health disorders: respiratory disorder (47.6%), hypercholesterolemia (38.1%), and hypertension (23.8%). 61.9% reported two or more physical health disorders. Screening: 62% had their blood pressure taken, 28.6% reported undergoing tests for cholesterol, and 19% reported having their blood glucose checked |

| Happell et al. (2016a, 2016b, 2016c) | Australia, Australasia | Consumers' perceptions and experiences regarding the availability and quality of care and treatment provided in response to physical health needs and issues. | Community |

Qualitative exploratory methods Four focus groups |

Consumers (n = 31) | High |

Consumers experienced symptomizing by providers where physical symptoms were attributed to the consumers' mental illness, without consideration of a possible physical illness healthcare providers were viewed as dismissive of consumer concerns, the result was reluctance or failure to act by the providers Consumers felt very vulnerable in terms of their physical health, and by implication, were more alert to prejudice in the healthcare system |

| Happell et al. (2016a, 2016b, 2016c) | Australia, Australasia | To seek the views and opinions of consumers regarding the introduction and implementation of a physical health‐care nursing position within the mental health clinical team. | Community |

Qualitative exploratory methods Four focus groups |

Consumers (n = 31) | High |

A specialist PHNC is perceived to play an important role in addressing the physical health inequities, albeit with some logistical concerns Consumers expressed potential capacity for this new nursing role to facilitate the integration of physical healthcare into mental health services Consumers hoped the role will assist to change the focus from the more clinical aspects of care to those that would enhance health and well‐being at a more psychosocial level |

| Happell et al. (2016a, 2016b, 2016c) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer view regarding the meaning of physical health | Community |

Qualitative exploratory methods Four focus groups |

Consumers (n = 31) | High |

(1) ‘tied up together’ with mental health (2) ‘absence’ of physical disease, injury, or pain (3) being able to move one's body (4) engaging in struggles to eat a healthy diet (5) everyday functioning and participation in life |

| Happell et al. (2019) | Australia, Australasia | Explore consumers' views of how their physical health needs are addressed within mental health services; and strategies that have or could be used to improve the current situation | Community |

Qualitative exploratory methods Four focus groups |

Consumers (n = 31) | High |

Consumers reported seeking diverse services to support physical health well‐being, e.g., GP and allied health Consumers expressed a desire to be at the centre of the interprofessional team communication/collaboration for holistic care Consumers advocated for more gateways to physical healthcare, e.g., access to GPs and less gatekeeping, referring to a preference for more holistic/interprofessional care |

| Hassan et al. (2020) | England, UK | Explore the barriers and facilitators of implementing the PRIM ROSE intervention into primary care across England, applying NPT to facilitate a deeper understanding of the factors that affected implementation. | Community |

Qualitative Individual interview |

Consumers (n = 15) Clinicians (n = 15 nurses and HCAs) |

High |

The aim of the intervention to focus on health improvement and reduce CVD risk was mostly perceived as clear and coherent The intervention was perceived as valuable Consumers reported staff making substantial efforts to encourage them to engage with the intervention by making it accessible, e.g., appointments suited to their preference Consumers expressed mixed views about the use of health plans due to being problematic to use (repetitive and difficult) and time‐consuming Positive relationships with staff were considered important and encouraged engagement |

| Hemmings and Soundy (2020) | England, UK | Consumers' experiences of physiotherapy intervention‐ barriers and facilitators to care | Inpatient |

Interpretive‐phenomenological approach (IPA) Individual interviews |

Convenience sampling Consumers (n = 8) Women (n = 3) |

High |

Communication and therapeutic relationships with healthcare providers are considered important because they could feel at ease and be motivated Consumers experienced the integration of physical and mental healthcare Benefits of physiotherapy: improved mental and physical health Barriers: healthcare politics, silo effect, detached processes (discharge following non‐attendance), amotivation |

| Henning Cruickshank et al. (2020) | Australia, Australasia | Investigate whether consumers considered their physical health and if limiting sugar‐sweetened beverages (SSB) at facility outlets influenced dietary behaviours and knowledge |

Community Residential rehabilitation facility |

Cross‐sectional survey study Pre and post |

Consumers (n = 26) | Moderate |

31% (n = 8) reported modifying their beverage choices when offsite post‐intervention Vast majority reported good physical health was important to them (96% n = 25) and 46% (n = 11) stated the intervention made them consider how SSB consumption affected their health 81% (n = 21) noticed changes to beverages available for purchase and 62% (n = 17) reported purchasing on‐site beverages once weekly or more |

| Ince and Günüşen (2018) | Turkey, Europe | Consumer views on barriers, enablers/facilitators, needs and habits towards physical activity and nutrition | Community |

Descriptive qualitative study Socio‐demographic information form Semi‐structured in‐depth individual interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 15) Mean age: 41.13 Men (n = 12) |

High |

Physical health barriers included: adverse effects of the psychiatric drugs, psychiatric symptoms, fear, unwillingness, physical problems, being alone Nutrition barriers included: paranoid delusions, lack of information on healthy cooking and eating, living alone, economical insufficiencies Facilitators for a healthy lifestyle: regular attendance to the community centre, dislike being overweight, care about outer appearance, and social support Unhealthy habits: lacking awareness of health importance, walking frequently performed, non‐engagement in regular sporting activities, eating carbohydrates mostly, takeaway and eating at night or irregularly Support needs for a healthy lifestyle: information about physical activity and healthy eating, social, and economic support |

| Ince et al. (2019) | Turkey, Europe | Perception of consumers and carers regarding the physical health status of consumers |

Inpatient 30‐bed adult clinic |

Descriptive qualitative study Individual interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 11) Mean age: 42.54 Men (n = 6) Carers (n = 12) Women (n = 11) |

High |

Barriers to physical wellness included: no one cooks for them at home, side effects of psychiatric drugs, e.g., balance, mental illness, lacking knowledge on the importance of breast screening, dental check‐ups, and financial difficulties Motivators for better physical health included: knowledge of physical health practices, social support, concerns about future physical health issues, the expectation of clinicians providing information about protective practices, and coping with mental illness |

| Katakura et al. (2013) | Japan, Australasia | Explore the psychological and physical self‐management behaviours of consumers; to identify their motivations for their self‐management behaviours; and develop a framework to understand the generative processes of healthy vs unhealthy conditions |

Community Rehabilitation centres |

Inductive qualitative approach Individual interviews |

Consumers (n = 8) Women (n = 4) |

High |

Self‐management behaviours included: control of psychological symptoms with expectations of warning signs, resting to control psychological conditions, self‐taught approaches to control physical complications, attending a rehabilitation centre to keep a regular schedule, acquisition of support and information to maintain health, and effort to gain the understanding of an attending psychiatrist Motivators included: getting a job in the near future or ‘maintaining my current level of living’ Some consumers recognized that the use of their own methods caused unhealthy conditions, e.g., when health management was excessively strict |

| Kern et al. (2020) | France, Europe | To evaluate the impact of this Adapted Physical Activity program (APA) on physical and psychological dimensions in consumers hospitalized with Anorexia Nervosa (AN) and to evaluate narratives of consumers hospitalized with AN on perceived effect of APA program using a qualitative method. | Inpatient Eating Disorder Centre |

Mixed methods BMI Survey: physical activity perception, dependence to physical exercise, ED symptoms, quality of life Individual interviews using the Narrative Evaluation of Intervention |

Consumers (n = 10/41) interviewed All women Mean age: 16.35 |

High |

Consumers perceived the AN program positively and that it matched its intent, e.g., balancing the use of physical activity (not only for weight loss) APA session is a place where they can let off steam and learn to feel body sensations PA practice shifted to pleasure from automatic routine or unconscious practice |

| Mateo‐Urdiales et al. (2020) | England, UK | Describe the feasibility of a programme aimed to help consumers to eat healthily and be physically active | Two inpatient units |

Mixed methods Survey Four individual interviews Two focus groups |

Consumers (n = 18) Women (n = 10) |

High |

Female patients were satisfied with the opportunities offered to increase physical activity but were less satisfied with the opportunities to eat healthier food Staff engagement is key especially if they show enthusiasm, initiative, and motivation because it fosters participation in activities Careful planning is needed for the interventions to be effectively implemented Healthy weight interventions should be part of a continuous process |

| Matthews et al. (2021) † | Ireland, UK | Consumer and clinician experiences of structured and unstructured physical activity |

Community Outpatient rehabilitation and recovery mental health services |

Qualitative exploratory study Individual interviews Visual methods via autography (participant takes photos for use) Photo elicitation (visual material use to create discussion) |

Stratified convenience sampling Consumers (n‐6) Peer support worker (n = 1) Carer (n = 1) Clinicians (n = 6) |

High |

The challenges of being physically active (PA) in recovery included: stigma because sometimes consumers had to obtain permission from clinicians to engage in PA in their supported residence, sedentary behaviour is routine, limitations of current knowledge, access and transport barrier, psychiatric symptoms, and medications Physical activity enabled recovery through social interactions, conversations, and therapeutic interactions during PA, on‐site resources and facilities for PA, partnership with community‐orientated initiatives PA was well‐received if it is engaging and achievable |

| McCloughen et al. (2016) | Australia, Australasia | Distinguish particular meanings and understandings influencing attitudes and behaviours related to physical health and well‐being by young consumers |

Inpatient Two acute mental health units |

Qualitative follow‐up explanatory phase of a sequential mixed‐methods study |

Convenience sample Consumers (n = 12) Women (n = 7) |

High |

Consumers had unmet ideal of physical health such as (1) aspiring to a particular body type, e.g., someone slim, (2) balance equated to having a good diet, (3) sufficient exercise, (4) good quality sleep, and (5) spending time with friend and family Outward appearance was a key indicator of physical health Consumers thought their ideal standard of physical health was attainable but none believed they were meeting their ideal Consumers felt different and noted things have changed because of differences in how they looked, felt, and acted Physical changes were concerning for participants due to perceived negative impacts and implications Consumers desired to gain control over their physical health but most participants were not actively addressing their health concerns because they were combatting amotivation, increasing understanding, and applying knowledge |

| Nash (2014) | England, UK | Consumer views on diabetes care | Community |

Qualitative descriptive study Individual interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 7) Women (n = 4) Diabetes history ranged from 2‐25 years |

High |

Symptom reports or illness complaints were minimized or not believed because of their mental illness histories Participants experienced physical symptom reports being recast as symptoms of mental illness Consumers noted a split between mental health and physical well‐being: lack of integration in care means that diabetes is regularly unchecked in mental health services Some consumers experienced complications of diabetes such as peripheral neuropathy, one hyperglycaemia, one an opportunistic fungal infection, and one diabetic ketoacidosis Suggested solutions included: practical help, support, and information from their nurses All participants were diagnosed outside mental health services, three by chance by their GP |

| Owens et al. (2010) † | England, UK | Consumer and clinician understanding of well‐being, experiences, and opinions of well‐being promotion and examine ways of enhancing and improving consumers' well‐being through further well‐being promotion | Community |

Qualitative case study methodology Focus groups |

Purposive criterion sampling Consumers (n = 5) Women (n = 4) |

High |

Well‐being is expressed as a holistic concept including a sense of normality Well‐being affected by medication side effects, e.g., weight gain Consumers reported positive (opportunity to participate in a range of enjoyable activities designed to promote their well‐being and socialization, having something to go out for) and negative experiences of well‐being promotion. Debate that although well‐being activities existed, such as sports therapy and weight management, information and awareness of them were not routinely provided |

| Pals and Hempler (2018) | Denmark, Europe | Explore consumer preferences and ideas related to achieving a collaborative approach in health‐related communication | Community |

Participatory design approach Four workshops |

Consumers (n = 15) Women (n = 7) |

High |

Consumers preferred to be involved in deciding agendas and settings for health‐promoting activities, which included being consulted about whether and how to involve their social network in health promotion A narrow concept of health, such as a focus on adherence with national recommendations, undermined a focus on the individual Telling users what to do instead of exploring motivation for change |

| Park et al. (2017) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer experiences with a healthy lifestyle program | Community |

Qualitative exploratory study (part of larger RCT) Individual interviews |

Consumers from the RCT (n = 10) Women (n = 8) |

High |

Consumers reported learning how to make healthy choices; food choices and recognizing the importance of exercise as part of a healthy lifestyle Recognizing the importance of exercise for weight management Accessing support from a health professional Being part of a group |

| Patel et al. (2018) | Canada, North America | Consumer view of the link between consumer participation and physical health | Community | Semi‐structured qualitative and quantitative (demographic data) interviews and tours of participant's community |

Stratified purposeful sampling Consumers (n = 30) Women (n = 15) Mean age: 45 |

High |

A bidirectional process was identified whereby physical health impacted community participation and community participation impacted physical health Physical activity was perceived as beneficial to mobility and having an empowering impact Physical health was described as a means to feel empowered, e.g., feel good but also a source of community involvement Many of the participants engaged in negative health behaviours as a strategy for coping with social isolation and problems with the community |

| Pickard et al. (2017) | England, UK | Consumer experiences of exercise | Community |

Interpretive‐phenomenological design Individual interviews |

Consumers (n = 5) | High |

Consumers identified the interconnectedness of physical and mental health Consumers did not know when they will be well hence limited plans can be made Consumers challenged their self‐image through exercise however physical limitations required adjustment to their self‐image |

| Roberts and Bailey (2013) | England, UK | Consumers perceptions of barriers and incentives to an educational lifestyle intervention | Community |

Ethnographic qualitative study Participant observations Individual interviews |

Opportunistic sample Consumers (n = 8) Women (n = 2) |

High |

Barriers included: weight gain or being overweight, apprehension of meeting new people, lack of information, negative attitudes of healthcare staff, not knowing what the potential benefits were Incentives included: weight loss, social interaction, and peer support, knowledge gain, staff attributes, knowing about physical and mental health benefits of healthy lifestyles, and attending intervention |

| Rollins et al. (2017) | USA, North America | How consumers perceive and manage both mental and physical health conditions and their views of integrated services | Community |

Qualitative study Individual interviews |

Convenience sampling Consumers (n = 39) |

High |

Prevalence and how consumers managed condition Hypertension (68%) is managed by taking medications as prescribed, getting exercise, and being conscientious of what they consume COPD (28%) managed using oxygen, inhalers or nebulizers, and/or quitting smoking Diabetes (16%) is managed by monitoring blood sugar, taking insulin, and being cautious about eating habit Heart disease (7 participants) managed by taking medication, exercising, quitting smoking, and having a healthy diet 54% responded that they do, in fact, approach the management of their physical health and mental health differently Perceptions of integrated care: convenience, friendly and knowledgeable staff, shared information and communication, needed improvement, e.g., resources |

| Rönngren et al. (2018) | Sweden, Europe | Consumer experiences with receiving support from a nurse‐led lifestyle programme, and how this support was related to their life context, including challenges and coping strategies | Community |

Qualitative study Two focus groups Six individual interviews |

Consumers (n = 13) Women (n = 11) |

High |

Challenges in daily life included: draining and pacifying symptoms, limited social understanding and interaction, insufficient coping strategies Benefits and disadvantages of the programme: support for lifestyle changes, social connection and a ‘safe place’, knowledge and understanding of health and illness, and gain coping strategies |

| Rönngren et al. (2014) | Sweden, Europe | Obtain further knowledge for developing a sustainable lifestyle programme by exploring consumers' experiences with Physical activity (PHYS) programmes and lifestyle habits | Community |

Qualitative study Three focus groups |

Four to eight participants in each focus group for the local reference group, community mental health users (CMHU) and community mental health workers (CMHW) | High |

Consumers expressed a wish to and considered a lifestyle intervention programme to be a good idea To increase motivation, they expressed a desire to join group training, and to use aids such as mobile apps and activity diaries, inspired by watching sports on television Structuring the daily schedule was thought to be a good strategy to achieve lifestyle changes Consumers also requested support from the CMHWs Difficulties achieving lifestyle changes: lack of knowledge and support, loneliness, and lack of general resources |

| Small et al. (2017) | England, UK | Explore consumers, carer and professional experiences of and preferences for consumer and carer involvement in physical health discussions within mental healthcare planning, and develop a conceptual framework of effective user‐led involvement in this aspect of service provision | Community |

Qualitative exploratory study Six focus groups Four telephone interviews |

Consumers (n = 12) Consumers with a dual consumer and carer role (n = 2) |

High |

Consumer suggested general care planning requirements: tailoring a collaborative working relationship, maintaining a trusting relationship with the care planning professional, and having access to and being able to contribute to a living document Specific to physical health, consumers preferred: the valuing of physical health equally with mental health, experiencing coordination of care between physical‐mental health professionals, having a physical health discussion that is personalized |

| Stanton et al. (2016) | Australia, Australasia | Examines consumer attendance at, and satisfaction with a group exercise program | Inpatient |

Cross‐sectional survey design Discharge surveys to evaluate group activities |

Consumers (n = 32, 85.6% response rate) | High |

57.1% rated exercise as ‘excellent’ compared with all other activities Nonattendance rates were lowest for cognitive behavioural therapy, (n = 2, 6.3%) and reflection/ discussion (n = 2, 6.3%) groups and highest for the relaxation group (n = 6, 18.8%) |

| van Hasselt et al. (2013) † | Netherlands, Europe | Consumer and carer view on the current barriers and make suggestions on how to improve the logistics of physical healthcare. | Community |

Qualitative study (part of a larger study) Seven individual interviews Two group interviews of three consumers and carers |

Convenience sample Consumers (n = 10) Women (n = 6) |

High |

Needs of consumers differ from the general population therefore it is necessary to tailor their healthcare to their specific needs Barriers: the sense of inferiority, most of them experience stress before and during the consultation, and while waiting for the results of laboratory assessments, lack of or non‐systematic collaboration between professionals, nil discussion of physical health by the mental healthcare team Suggestions: systematic professional collaboration and clarification of roles, flexible approach from GP, e.g., reassurance and paying attention to mental health, individualized support, monitoring, and supporting a healthy lifestyle |

| Vazin et al. (2016) | USA, North America | Describe perceptions of weight‐loss strategies, benefits, and barriers of consumers who lost weight in the ACHIEVE behavioural weight loss intervention |

Community Six psychiatric rehabilitation program sites |

Qualitative study (part of an RCT) Individual interviews |

Convenience sample Consumers (n = 20) Mean age: 46 Average weight loss: 7.03kg |

High |

Strategies for weight loss: dietary strategies (portion control, reduce consumption of sugary products, drink more water, consume more fruits and vegetables, and prepare food at home), tailored, scheduled exercise sessions, staying active outside of scheduled exercise sessions, social support, hard work, and perseverance Benefits of participating in the interventions: improved physical appearance (fitting into clothes), improved self‐efficacy, improved ability to perform activities of daily living, health‐related benefits (strength, increased endurance, and feeling better overall), attended psychiatric rehabilitation program more frequently, felt proud Barriers to weight loss: giving up snacks and junk food, inability to participate in exercise due to medical conditions, difficulty controlling portion size, eating at night, losing confidence, medication‐related appetite, cost, and attendance |

| Verhaeghe et al. (2013) † | Belgium, Europe | Consumer and clinician view of factors influencing integration of physical activity and healthy eating in sheltered housing | Community |

Qualitative descriptive study Individual interviews Three focus groups with mental health nurses |

Purposive sampling strategy Consumers (n = 15) Women (n = 6) Mean age: 43 |

High |

There was an awareness of the importance of physical activity and healthy eating Benefits: general health, physical shape, distraction, less stress and frustration, and social contacts Health promotion: the importance of support from mental health nurses Majority of consumers were interested in group sessions providing informative and educational sessions targeting PA and healthy eating |

| Wardig et al. (2015) | Sweden, Europe | Consumers experience with a lifestyle intervention | Community |

Qualitative phenomenographic approach Individual interviews |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 40) Women (n = 19) Mean age: 46 |

High |

Consumers preferred everything in moderation: e.g., moderate intervention level without underestimating the participants' ability, group size to enable sharing experiencing, the health coordinator should balance and individualize the content Caring for each other to enable voluntary participation and compared themselves to serve as a point of reference for their own definition of normality Intervention was experienced as a positive event and contributed to new friendships The continued journey to a healthier lifestyle enabled by the intervention providing knowledge of the interconnectedness of physical and mental health Small changes could be motivated by being easier to adhere to overtime One new good behaviour predisposed to further improvements Intervention had an extended effect, as participants could relay information to their families |

| Watkins et al. (2020) | Australia, Australasia | Explore the personal experiences of KBIM participants, in particular the aspects of the programme that they perceived to be helpful in achieving physical health and other improvements. | Community |

Qualitative descriptive study Individual interviews |

Consumers (n = 11) Women (n = 4) |

High |

Physical health aided mental health recovery, e.g., improved self‐esteem, renewed sense of hope, improved mood, and increased motivation) Staff interactions were viewed as important, e.g., support and encouragement via goal setting, metabolic screening Peer support, interaction, and activities led to a reduction in social isolation, shared learning, and reduction in stigma Participants believed that they now had the knowledge to live a healthy lifestyle, that the changes they had made could be sustained, and that their capacity to make lifestyle changes in the future was enhanced |

| Wheeler et al. (2018) | New Zealand, Australasia | Consumer self‐reported beliefs about their health and quality of life | Community |

Cross‐sectional survey Self‐administered Medical Outcomes Study 36‐Item Short Form |

Consumers (n = 404, 28% response rate ) Women (n = 224) Mean age 41.2 |

High |

Mental health service users reported a poorer HQoL than respondents to the NZ Health Survey Respondents aged under 25 years of age scored significantly higher for physical functioning than those 25 years and older Participants who reported their first contact with mental health services below the age of 25 scored significantly higher in role limitations in physical health than those whose first contact was at 25 years or older Males scored significantly higher than females on the social functioning domain |

| Wheeler et al. (2018) † | Australia, Australasia | Consumer and clinician (exercise practitioners) views about barriers and facilitators to engaging in physical activity/ exercise | Community |

Qualitative study Phase 1: 15 individual interviews with consumers Phase 2: two focus groups to cross‐check themes and co‐design understand the barriers and enablers for Australian mental health consumers to participate in physical activity or exercise programmes from the perspectives of consumers and exercise practitioners |

Purposive sampling Consumers (n = 15) Mean age: 38.2 Women (n = 7) |

High |

Barriers to engaging in an exercise in the community: lack of social support, knowledge, and information, of work/life balance; the impact of physical and/or mental health issues (in many cases multiple health issues and medication effects); fear and lack of confidence, and financial cost to participate Enablers to engage in exercise in the community: social support; person‐centred (individualized) options; connection and a sense of belonging; and access to information and education, and raising awareness. Co‐designed recommendations: support and affordability, flexible, person‐centred holistic individualized service provision and exercise plans |

| Wright‐Berryman and Cremering (2017) | USA, North America | Explore consumer and clinician attitudes towards healthcare experiences and preferences for physical health decision making and decision aid | Community |

Qualitative study Two focus groups |

Snowball sampling Consumers (n = 9) |

High |

Consumers desired autonomy and shared decision‐making in physical healthcare decision making however perceived the doctor should make the final decision (viewed as the expert) Consumers were divided equally, with four responding that they do receive enough medical information sharing Decision aid preferences: computerized decision aid because it would have their medical information readily available |

| Young et al. (2017) | Australia, Australasia | Consumer views about how Mental health services manage/attend to their physical health | Inpatient and community |

Qualitative, cross‐sectional study Individual interviews |

Convenience sampling Consumers (n = 40) Women (n = 17) Mean age: 47 |

High |

Nearly all consumers (n = 38) relied heavily on the MHS (mainly case manager) for access to healthcare Majority reported various health‐related concerns (mainly side effects from medications, weight, and body shape), describing a range of detrimental effects these had on daily activities, social interaction, and quality of life A minority reported physical state or health were generally given little thought, considered only in passing, or when prompted, for example, by pain or when the doctor suggested an assessment Participants reported general awareness of physical health, and contemplating and acting to improve health ‘from time to time’ The majority reported at least being ‘measured’ or asked by clinicians at some time about indicators of physical health Most participants recalled being asked about sleep, diet, and alcohol and tobacco use, and having blood pressure, temperature, and weight monitored, but reported frequency varied |

Legend: Dx = diagnosis; eMR = electronic medical record; HQoL = health‐related quality of life.

Study contains consumer and carer population.

Aligning with the review question, studies outlined in Table 4 were categorized according to their main focus which resulted in three main themes, reflecting the consumers: (i) attitude towards physical health, (ii) perception of physical healthcare, and (iii) experiences with a physical health intervention. Within the main themes, sub‐themes were identified and speak to the common perceptions and experiences of consumers regarding physical health and interventions to improve their physical health.

Attitudes towards physical health