Abstract

Context

Botulinum Toxin type A (BTX-A) has historically been used as a treatment to reduce spasticity. However, its potential to treat neuropathic pain is increasingly being recognized in the literature. This clinical review examines the evidence regarding the use of BTX-A in directly treating neuropathic pain in the spinal cord injured population.

Methods

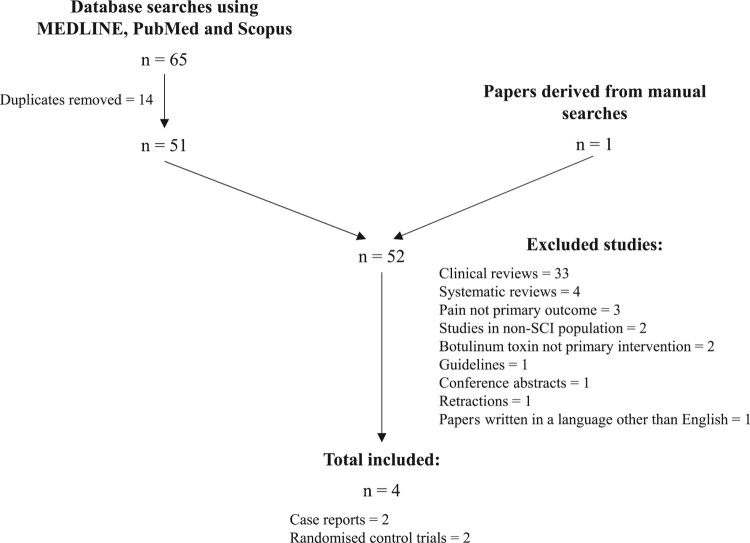

An electronic literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, PubMed and Scopus from inception to May 2020. The key words ‘spinal cord injury’ AND ‘neuropathic pain’ AND ‘botulinum toxin’ AND ‘human’ were used. The literature search produced a total of 65 results of which 14 duplicates were removed. There was 1 additional paper included following a manual search, providing a total of 52 papers. Taking into account inclusion and exclusion criteria, 2 case reports and 2 randomized control trials were reviewed.

Results

While there are multiple studies published on the use of BTX-A to manage neuropathic pain in other patient populations, there is very little published on its potential to treat spinal cord injury-related neuropathic pain. The provisional data provides some evidence that subcutaneous injection of BTX-A may benefit this patient group, although dosing and application schedules remain untested, and information on longer-term complications has yet to be been collected.

Conclusion

While early results are interesting, the quality and quantity of research published is not yet high enough to provide formal guidance on the use of BTX-A in treating central neuropathic pain in the spinal cord injury population. Further high-quality research is therefore recommended going forward.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Neuropathic pain, botulinum toxin

Context

BTX-A has predominantly been used as a treatment to reduce spasticity in the rehabilitation setting;1 however its potential to treat neuropathic pain is increasingly being recognized in the literature.2–4 Its analgesic properties have previously been attributed to an indirect effect caused by treating focal spasticity, whereby the toxin inhibits Acetylcholine release at the neuro-muscular junction via the cleavage of transporter protein SNAP-25.5,6 However, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that BTX-A has a separate effect on treating pain that is distinct from this mechanism. This review examines the evidence regarding the use of BTX-A in directly treating central neuropathic pain in the spinal cord injured population.

Neuropathic pain is defined as pain caused by injury or insult to the somatosensory nervous system.7 It is often characterized as burning, stabbing or electric-shock-like in nature. A disruption to the spinal cord through injury is thought to cause sensitivity to normal nociceptive processing, i.e. stimuli that were not painful before the injury may now become painful (allodynia), or those that were previously painful become even more so (hyperalgesia).8 Neuropathic pain can occur at the level of (described as ‘band-like) or below the level of a spinal cord lesion, with an incidence of 41% and 34%, respectively.9

There are various hypotheses of how BTX-A acts in the presence of neuropathic pain, although the exact mechanisms of action remain unknown. A key theory suggests that BTX-A may reduce peripheral nervous system sensitization of nociceptive fibers by inhibiting the release of neuropeptides such as Glutamate. Glutamate is understood to play a key role in modulating neuropathic pain: a study in 2019 demonstrated that Glutamate-evoked neuronal excitability is dramatically enhanced following nerve injury and is directly associated with the onset of neuropathic pain. Accelerated neuronal excitability was also seen to decline following recovery from pain.10 A study conducted by McMahon et al. provided in-vitro evidence that the release of Glutamate is inhibited by BTX-A.11 Research in the rat population has revealed that levels of Vesicular Glutamate Transporter 2 (VGluT2), which controls the storage and release of Glutamate, correlate with the upregulation of SNAP-25 in spinal cord injured rats with neuropathic pain. In this study, peripherally injected BTX-A was shown to downregulate the expression of VGluT2, therefore reducing the release of Glutamate and concurrently reducing the experience of neuropathic pain.12

The mechanism of transport of peripherally injected BTX-A to the spinal cord is thought to be due to retrograde transport starting at peripheral nerves endings. Marinelli et al.13 demonstrated the presence of immunostained cleaved SNAP-25 in peripheral nerve endings, the sciatic nerve, the dorsal root ganglion and dorsal horns of the spinal cord following subcutaneous injection of BTX-A in mice with sciatic nerve injury. Therefore, the effect of BTX-A to reduce neuropathic pain may be due to both actions on the central nervous system as well as the peripheral nervous system. Further research is required to pinpoint the exact mechanism of axonal transport and action.

Methods

An electronic literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, PubMed and Scopus from inception to May 2020. The key words; ‘spinal cord injury’ AND ‘neuropathic pain’ AND ‘botulinum toxin’ AND ‘human’ were used. Institutional approval was not required for this study.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the study adopted a clinical design based on human subjects, (2) all participants had a spinal cord injury, (3) the intervention was subcutaneous injection of BTX-A, (3) the primary outcome measure related to assessment of neuropathic pain, and (4) the language was limited to English. If a study did not meet all of the inclusion criteria, it was excluded. To ensure the inclusion of all relevant studies, a manual search of reference lists from all studies examined was also conducted.

The literature search produced a total of 65 results from the 3 databases, where 14 duplicates were removed. There was 1 further paper included following the manual search, providing a total of 52 papers. 48 papers were subsequently excluded for the following reasons; the papers were clinical reviews (33) or systematic reviews (4), pain was not the primary outcome (3), the studies were conducted in a non-SCI population (2), BTX-A subcutaneous injection was not the primary intervention (2), the paper was retracted (1), or a guideline (1), or a conference abstract (1). 1 paper was not available in English. Taking this into account, 2 case reports and 2 randomized control trials were reviewed. The process of inclusion and exclusion is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of inclusion and exclusion of papers for review.

Results

While there have been studies published on the use of BTX-A to manage neuropathic pain in non-spinal cord injury populations,2–4 there is notably very little published on its potential to treat spinal cord injury-related neuropathic pain. In 2003, Jabbari et al.15 published two case reports of subjects with cervical spinal cord injury who developed at-level bilateral neuropathic pain. They were given multiple subcutaneous injections of 5 units BTX-A in the areas of pain on one side (to a total of 80 and 100 units, respectively). Both patients experienced pain relief on the side of the injections starting at 1 week post injection and lasting at least 3 months. The analgesic effect of the injections was sustained over follow-up periods of 2 and 3 years with repeated administrations provided 3 times a year. There were no side effects experienced (including no experience of muscle weakness).

A case report published by Han et al. in 20146 described a case of spinal cord injury-associated refractory neuropathic pain treated with BTX-A subcutaneous injection. Ten units were injected into 10 sites in each foot (to a total of 200 units). The patient was assessed at 4 and 8 weeks and no side effects were noted. The subject experienced a reduction in overall and neuropathic pain at both 4 and 8 weeks, however the results were not statistically significant.

Han et al.5 went on to produce higher quality evidence in 2016, publishing a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. 40 patients with spinal cord injury-associated neuropathic pain were included. If patients were taking analgesic medication, this was authorized, provided that the dose was stable for at least 1 month prior to and throughout the study. Two hundred units BTX-A were administered in a checkerboard pattern subcutaneously in the area of pain. Forty injections were administered per patient, with at least 1 cm between injection sites.

The primary outcome measure for this research was the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (0 = no pain, 100 = unbearable pain) at 0, 4 and 8 weeks. The authors demonstrated that at 4 and 8 weeks after injection, pain scores reduced in the BTX-A group compared to the placebo group. Specifically, the BTX-A group showed significant reductions of the VAS score at 4 (P = 0.0027) and 8 weeks (P = 0.0053) following injection. The VAS scores of the BTX-A group were 18.6 ± 16.8 lower at 4 weeks and 21.3 ± 26.8 lower at 8 weeks post injection (moving from 85.1 ± 13.6 at baseline, to 66.5 ± 20.7 (P < 0.0001) at 4 weeks, and 63.8 ± 27.5 (P = 0.0012) at 8 weeks). VAS scores of the placebo group were 2.6 ± 14.6 lower at 4 weeks and 0.3 ± 19.5 lower at 8 weeks after the injection (the results of which were not statistically significant).

Fifty-five percent of participants receiving BTX-A reported pain relief of 20% or greater at 4 weeks post injection (P = 0.0132), compared to 15% in the placebo group. It is noted that only the results for the BTX-A group were statistically significant. The authors also noted a higher effect in patients with incomplete SCI compared to complete SCI and found BTX-A was effective at treating below-level (but not at-level) neuropathic pain.

In terms of safety, the authors commented on a risk of the injection itself triggering pain and/or spasticity in either the BTX-A or placebo groups. Spasticity levels between the groups remained similar before and after intervention, suggesting BTX-A acts to reduce neuropathic pain independently of its effects on spasticity. This trial was relatively short in length, following patients up for only 8 weeks in total. Therefore, the longer term effects and risks of treatment were not assessed.

Most recently, in 2019 Chun et al. set to publish a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study.14 Subcutaneous injection of either normal saline (placebo) or BTX-A was delivered to the area of pain and participants were followed up at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-injection. A crossover of participants was then performed after a 12 week break, with further follow up at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. In terms of dosage, 80 injections of 5 units each of BTX-A (to a maximum of 400 units) was delivered per participant.

Results did not reach statistical significance, however the authors found that at 2 and 4 weeks post-BTX-A injection, almost all participants reported some degree of reduced pain compared to none post-placebo (83% vs. 0%). The authors proposed the reason for poor participant retention was due to a lack of accounting and preparing for the time, planning, and costs required for participants to take part. Additionally, they proposed the incentive to continue was reduced following delivery of possible treatment.

While 8 participants proceeded to have injections, 3 were lost to follow up and 1 declined to continue (due to the adverse event of the worsening of pain). As such, the study has been described as a descriptive case series of 4 cases.

Conclusions

A key weakness of the findings by Han et al.6 and Chun et al. is that data from a total of 7 case reports cannot be extrapolated to apply to the spinal cord injured patient group as whole. While the data is informative, it is certainly not conclusive. In the case of Han et al., no control element to the study was included, for example using the non-injected side for comparison or using placebo. Therefore, an expected natural improvement in pain over time could not be ruled out. Chun et al. has provided preliminary evidence that pain may improve when compared to injection with placebo, but their results did not reach significance.

In all cases, the results may have been confounded by co-existing medical or psychiatric conditions, which were not commented on by the authors.

All studies used different maximum doses of BTX-A per participant (80–100 units by Jabarri et al., 200 units by Han et al., and 400 units by Chun et al.). It is unclear how the authors came to the conclusions to administer the doses that were used, as we note maximum recommended doses 400 units per participant for the management of spasticity in the United Kingdom.16

Further research is needed to investigate the onset time, duration, dosage, route and number of injections delivered in this population and for this indication in order to achieve optimum results, whilst limiting the risk of side effects.5 We also recommend that further research is conducted by the wider scientific community, as we note that 2 of the publications reviewed share 3 of the same authors.

Han et al. noted a higher effect in patients with incomplete SCI compared to complete SCI. Further rigorous study is required to investigate, this including considering confounding factors such as mechanism of injury and time following injury.

Lastly, the low retention rate in the study by Chun et al. is noted (only 50% participants continued to the end of the trial). While reasons were provided by the authors, further research is recommended to consider the barriers to delivering treatment, both for participants and providers. 1 participant experienced an increase in pain from all the studies described. Studies from larger populations are required going forward to further assess this and to report the presence or absence of other adverse events.

While these preliminary results are interesting, the quality and quantity of research published is not yet high enough to provide formal guidance on the use of BTX-A in treating central neuropathic pain in the spinal cord injury population. Shortcomings include a lack of studies available for review, and regarding the research data include low participant numbers, and the lack of standardizing the optimum dosage and delivery.17 Further high-quality research is therefore recommended going forward.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Funding None.

Conflicts of interest None.

References

- 1.Intiso D, Basciani M, Santamato A, Intiso M, Di Rienzo F.. Botulinum toxin type A for the treatment of neuropathic pain in neuro-rehabilitation. Toxins (Basel). 2015;7(7):2454–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attal N, de Andrade DC, Adam F, Ranoux D, Teixeira MJ, Galhardoni R, et al. Safety and efficacy of repeated injections of botulinum toxin A in peripheral neuropathic pain (BOTNEP): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(6):555–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salehi H, Moussaei M, Kamiab Z, Vakilian A.. The effects of botulinum toxin type A injection on pain symptoms, quality of life, and sleep quality of patients with diabetic neuropathy: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Iran J Neurol. 2019;18(3):99–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei J, Zhu X, Yang G, Shen J, Xie P, Zuo X, et al. The efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and peripheral neuropathic pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Brain Behav. 2019;9(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han ZA, Song DH, Oh HM, Chung ME.. Botulinum toxin type A for neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(4):569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han ZA, Song DH, Chung ME.. Effect of subcutaneous injection of botulinum toxin A on spinal cord injury-associated neuropathic pain. Spinal Cord. 2014;52(1):S5–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treede R, Jensen T, Campbell J, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky J, Griffin J, et al. Neuropathic pain: Redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70(18):1630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argoff CE. A focused review on the use of botulinum toxins for neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(6):S177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ.. A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain. 2003;103(3):249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong N, Hagopian G, Holmes TC, Luo ZD, Xu X.. Functional reorganization of local circuit connectivity in superficial spinal dorsal horn with neuropathic pain states. eNeuro. 2019;6(5). ENEURO.0272-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMahon HT, Foran P, Dolly JO, Verhage M, Wiegant VM, Nicholls DG.. Tetanus toxin and botulinum toxins type A and B inhibit glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid, aspartate, and met-enkephalin release from synaptosomes. Clues to the locus of action. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(30):21338–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Xu W, Kong Y, Huang J, Ding Z, Deng M, et al. SNAP-25 contributes to neuropathic pain by regulation of VGLuT2 expression in rats. Neuroscience. 2019;423:86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marinelli S, Vacca V, Ricordy R, Uggenti C, Tata AM, Luvisetto S, Pavone F, Premkumar, LS.. The analgesic effect on neuropathic pain of retrogradely transported botulinum neurotoxin A involves Schwann cells and astrocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chun A, Levy I, Yang A, Delgado A, Tsai CY, Leung E, et al. Treatment of at-level spinal cord injury pain with botulinum toxin A. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2019;5:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jabbari B, Maher N, Difazio MP.. Botulinum toxin A improved burning pain and allodynia in two patients with spinal cord pathology. Pain Med. 2003;4(2):206–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royal College of Physicians . British society of rehabilitation medicine, the chartered society of physiotherapy, association of chartered physiotherapists in neurology and the royal college of occupational therapists. Spasticity in adults: management using botulinum toxin. National guidelines. London: RCP; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matak I, Bölcskei K, Bach-Rojecky L, Helyes Z.. Mechanisms of botulinum toxin type A action on pain. Toxins (Basel).2019;11(8):459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]