Abstract

The cellulosome of Clostridium cellulovorans consists of three major subunits: CbpA, EngE, and ExgS. The C. cellulovorans scaffolding protein (CbpA) contains nine hydrophobic repeated domains (cohesins) for the binding of enzymatic subunits. Cohesin domains are quite homologous, but there are some questions regarding their binding specificity because some of the domains have regions of low-level sequence similarity. Two cohesins which exhibit 60% sequence similarity were investigated for their ability to bind cellulosomal enzymes. Cohesin 1 (Coh1) was found to contain amino acid residues corresponding to amino acids 312 to 453 of CbpA, which contains a total of 1,848 amino acid residues. Coh6 was determined to contain amino acid residues corresponding to residues 1113 to 1254 of CbpA. By genetic construction, these two cohesins were each fused to MalE, producing MalE-Coh1 and MalE-Coh6. The abilities of two fusion proteins to bind to EngE, ExgS, and CbpA were compared. Although MalE-Coh6 could bind EngE and ExgS, little or no binding of the enzymatic subunits was observed with MalE-Coh1. Significantly, the abilities of the two fusion proteins to bind CbpA were similar. The binding of dockerin-containing enzymes to cohesin-containing proteins was suggested as a model for assembly of cellulosomes. In our examination of the role of dockerins, it was also shown that the binding of endoglucanase B (EngB) to CbpA was dependent on the presence of EngB's dockerin. These results suggest that different cohesins may function with differing efficiency and specificity, that cohesins may play some role in the formation of polycellulosomes through Coh-CbpA interactions, and that dockerins play an important role during the interaction of cellulosomal enzymes and cohesins present in CbpA.

Clostridium cellulovorans (18) produces a cellulase enzyme complex (cellulosome) (1) composed of major subunits CbpA (16, 17), EngE (20), and ExgS (9) as well as other, minor subunits (2). Previously, we reported (11) that the binding of EngE and ExgS to cellulose was dependent on their initially binding to the scaffolding protein CbpA, which then bound the CbpA-EngE, CbpA-ExgS, and CbpA-EngE-ExgS complexes to the cellulose substrate through CbpA's cellulose-binding domain (6). These results suggested that the binding of CbpA to EngE or ExgS was a major mechanism for assembly of the active cellulosome.

Studies (3, 7, 15) with scaffolding protein CipA of Clostridium thermocellum (5) and CipC of Clostridium cellulolyticum (14) showed that only enzymes containing duplicated sequences (dockerins) were able to bind to their cognate cohesins. In the cases of C. thermocellum and C. cellulolyticum, the binding of cellulosomal enzymes appears to occur equally well with all the cohesins present in CipA and CipC, respectively (13, 23). Furthermore, it was shown that there are species-specific interactions between cohesins and dockerins (12).

There is a much higher degree of sequence similarity between the cohesins in both CipA (5) and CipC (14) than that which exists in CbpA. An analysis of the nine C. cellulovorans cohesins indicated that their sequence similarity to Coh6 ranges from 40 to 95% (2, 17). Since the level of sequence similarity of the cohesins in CbpA is much lower than that in CipA and CipC, we thought that the CbpA cohesins might bind cellulosomal enzymes with different degrees of efficiency. In this paper, we report a significant difference in the affinities of binding of Coh1 and Coh6 of CbpA to EngE and ExgS.

Expression of cohesins.

The abilities of Coh1 and Coh6, which have only 60% sequence similarity (Fig. 1), to bind to purified EngE, ExgS, and CbpA were determined. To avoid the low level of expression presumably caused by toxic effects of the highly hydrophobic cohesins (19), expression plasmids MalE-Coh1 and MalE-Coh6 were constructed from plasmid pMAL-c2, as shown in Fig. 2A. (10). For these constructions, restriction enzyme sites and a translation stop codon (Ecl136II, TAG-XbaI, and SnaBI) were prepared for subcloning by site-directed mutagenesis (8). The symmetric oligonucleotide (CATAGGATCCTATGGTAC) linker including a cohesive end for the KpnI site, a translation stop codon (TAG), and a BamHI site was used to obtain a BamHI site for subcloning of coh6 into pMal-c2. MalE-cohesins were expressed after induction with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and purified by affinity chromatography on an amylose resin column.

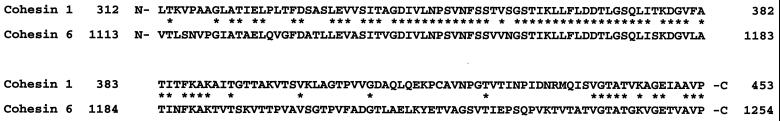

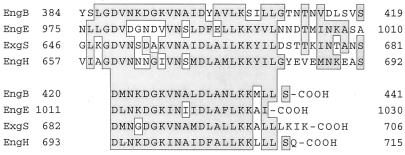

FIG. 1.

Sequence similarity between Coh1 and Coh6. Identical amino acid residues are indicated by stars. The numbers refer to amino acid residues of cellulose-binding protein A (CbpA) (17).

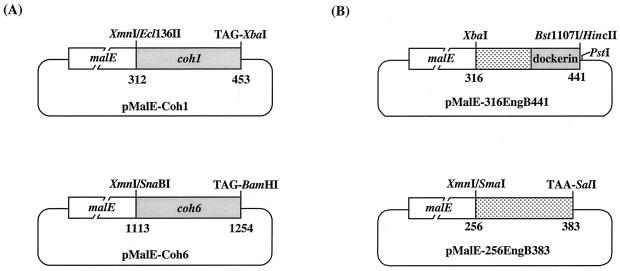

FIG. 2.

Plasmids used in these studies. (A) Construction of plasmids pMalE-Coh1 and pMalE-Coh6 to investigate the function of different cohesins. The MalE-Coh1 fusion protein contains the peptide from amino acids 312 to the 453 of CbpA (17). The MalE-Coh6 fusion protein contains residues corresponding to amino acids 1113 to 1254 of CbpA (17). (B) Construction of MalE fusion proteins for investigation of binding by the dockerin from EngB. Plasmid pMalE-316EngB441 was constructed for the production of a fusion protein that contained MalE fused with the peptide corresponding to amino acids 316 to 441 in the dockerin of EngB (4). Plasmid pMalE-256-EngB383 was constructed for the production of a fusion protein comprising MalE and a peptide corresponding to amino acids 265 to 383 of CbpA but lacking the dockerin of EngB (4). The XbaI site was from the engB gene. To obtain the PstI site used for subcloning into pMal-c2, the XbaI-BstI107I fragment of pC2-engB (4) was subcloned into the XbaI and HincII sites of M13mp18 (22). The SmaI site and TAA (translation stop codon)-SalI site were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis.

Effect of SDS concentration on binding of MalE-Coh6 to ExgS and EngE.

The use of a low concentration (0.003%) of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in the buffer was necessary in all our interaction Western blot experiments, since in the absence of SDS there was spontaneous aggregation of fusion proteins such as MalE-Coh1 and MalE-Coh6. Therefore, slot blotting was performed to determine the effect of SDS concentration on the binding of MalE-Coh6 to ExgS and EngE. Three-microgram portions of ExgS or EngE were blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane disks held by a slot blot apparatus. The disks were placed into 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, soaked with blocking buffer (3% gelatin in Tris-buffered saline [TBS; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 500 mM NaCl]), washed with washing buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in TBS), and soaked in washing buffers containing MalE-Coh6 (0.1 mg/ml) and different SDS concentrations (0, 0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, or 0.5%). The membrane disks were agitated for 2 h and then washed with washing buffer. The signals were detected as described elsewhere for interaction Western blotting (19) (Fig. 3). We found that MalE-Coh6 had the ability to bind ExgS and EngE even if the binding buffer contained 0.1% SDS. MalE-Coh6 finally lost its binding ability when 0.5% SDS binding buffer was used. In all subsequent binding studies, 0.003% SDS was used in the buffer.

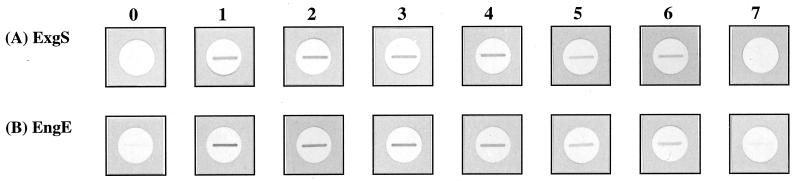

FIG. 3.

Effect of SDS concentration on binding of MalE-Coh6 to ExgS and EngE, as tested by slot blotting. Purified ExgS (A) and EngE (B) were blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane disks. Binding ability was monitored by using binding buffer containing MalE-Coh6 and different concentrations of SDS. The interaction Western blot assay (19) was employed to measure the interaction of Coh6 with ExgS and EngE, which is evidenced by dark bands on the disks. The disks blotted with ExgS and EngE were treated with anti-MalE to confirm that the proteins were not recognized by antibody alone (no. 0) but required the binding of Coh6. The numbers above the blots indicate the concentration of SDS: 1, 0%; 2, 0.001%; 3, 0.005%; 4, 0.01%; 5, 0.05%; 6, 0.1%; and 7, 0.5% SDS.

Ability of C. cellulovorans Coh1 and Coh6 to bind cellulosomal enzymes EngE and ExgS.

The binding of cellulosomal enzymes to cohesins was tested by using EngE and ExgS as well as Coh1 and Coh6. Coh6 has very high level of amino acid sequence similarity to Coh3, Coh4, Coh5, Coh7, and Coh8 (2, 17). It has a lower level of sequence similarity to Coh1, Coh2, and Coh9. Thus, our choice of using Coh6 was based on it being highly similar to most of the Coh subunits of CbpA. Coh1 was chosen because it has only 60% amino acid sequence similarity to Coh6 and because differences in binding ability of these two Cohs might be observed.

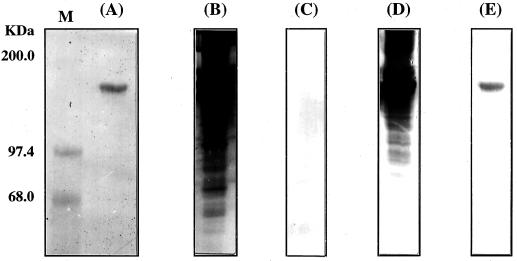

Figure 4A shows SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) patterns of purified ExgS (lane 1), EngE (lane 2), and CbpA (lane 3) used in the binding studies. The interaction Western blotting technique developed in our laboratory (19) was used to illustrate the interaction between the cohesins and the enzymes. In this technique, purified EngE, ExgS, and CbpA were first subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, washed with blocking buffer (3% gelatin in TBS), washed with washing buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in TBS), and then treated with washing buffer containing 0.1 mg of MalE fusion protein/ml for 2 h. The membranes were then washed with TBS and treated with washing buffer containing 1% gelatin and anti-MalE. Signals were detected by using a secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G) conjugated with alkaline phosphatase. SDS (0.003% final concentration) was added to all buffers to prevent aggregation of cohesin.

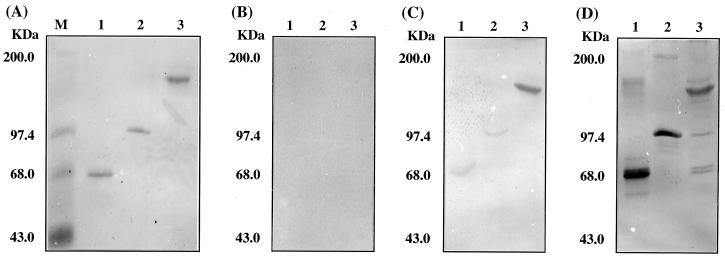

FIG. 4.

Interaction of ExgS, EngE, and CbpA with Coh1 and Coh6. (A) Coomassie blue staining of SDS-PAGE gel of CbpA. (B) Interaction Western blot prepared using MalE. (C) Interaction Western blot prepared using MalE-Coh1. (D) Interaction Western blot prepared using MalE-Coh6. Lanes: M, molecular mass markers; 1, ExgS; 2, EngE; 3, CbpA.

As a control for the interaction Western blotting experiment (19), MalE alone was incubated with the nitrocellulose membrane-bound enzymes (Fig. 4B); no bands were seen for ExgS, EngE, or CbpA. MalE-Coh6 bound efficiently to ExgS, EngE, and CbpA (Fig. 4D), whereas MalE-Coh1 was bound very poorly by ExgS and EngE but did bind to CbpA (Fig. 4C). The very poor binding of Coh1 to ExgS and EngE (Fig. 4C) strongly suggests that Coh1 and Coh6 have different binding abilities. Since this study was limited to the binding of EngE and ExgS, it is possible that Coh1 binds more efficiently to other, untested cellulosomal enzymes.

The binding of Coh6 to ExgS and EngE was not surprising, but the binding of both Coh6 and Coh1 to CbpA (Fig. 4C and D) was unexpected. This observation raises the interesting possibility that CbpA-CbpA interactions can occur through Coh-Coh binding, Coh-SLH (surface layer homology) domain binding, or interactions of Coh with other sites present on CbpA. The presence of a complex larger than CbpA, revealed by Western blotting (see Fig. 6B), suggests that CbpA-CbpA interactions are occurring, and this may be a mechanism for the formation of polycellulosomes.

FIG. 6.

Interactions between CbpA and the dockerin of EngB. (A) Coomassie blue staining of CbpA on an SDS-PAGE gel. The CbpA band is located at the position corresponding to 190 kDa. (B) Ordinary Western blot prepared using anti-CbpA immunoglobulin G. (C) Interaction Western blot with MalE as a control and without dockerin. (D) MalE-EngB with dockerin. (E) MalE-EngB without dockerin. Lane M, molecular mass markers.

Binding of CbpA to the dockerin from endoglucanase B.

A study was also carried out to determine whether the dockerin of EngB (4), which is similar to the dockerin in ExgS, EngE, and EngH (Fig. 5), has a function similar to that of the dockerins in several endo- and exoglucanases cloned from other Clostridium species (21). To investigate the binding of dockerin to CbpA, fusion proteins either containing a dockerin (MalE-316EngB441) or lacking a dockerin (MalE-265EngB383) were constructed (Fig. 2B) and used for binding assays. Figure 6A shows the electrophoretic pattern of the CbpA that was used for these experiments. Figure 6B is a typical Western blot prepared by using anti-CbpA. The results in Fig. 6B indicate that CbpA may aggregate into larger complexes and that there are degradation products present in the preparation. This has been observed previously with all CbpA proteins prepared in Escherichia coli (16). The presence or absence of a dockerin significantly affected the binding of the fusion proteins (Fig. 6D and E), as determined by interaction Western blotting; a positive result was obtained only when CbpA was bound to the EngB dockerin. MalE-316EngB441, which contains a dockerin, was shown to bind to CbpA (Fig. 6D), whereas in the absence of EngB dockerin only a faint band corresponding to the size of CbpA was present (Fig. 6E). This band was probably caused by a nonspecific hydrophobic interaction between CbpA and 265EngB383, as reported by Takagi et al. (19). These results indicate the importance of the dockerin in the binding of the enzyme to CbpA and support the results of previous studies with CipA and its cognate enzymes (14, 15).

FIG. 5.

Alignment of the duplicated segments of EngB, EngE, ExgS, and EngH of C. cellulovorans. Shaded-boxed amino acids are identical or have similar chemical properties. The numbers refer to amino acid residues of each enzyme; all sequences are numbered from Met-1 of the peptide. Similar residues are as follows: V, L, I, M, and F; R and K; D and E; N and Q; Y, F, and W; and S and T.

There are several possible explanations for the efficient binding of Coh6 to ExgS and EngE and the apparent low efficiency of binding of Coh1 to these enzymes. First, there may exist in Coh6 a specific region or sequence that is bound by the dockerins of ExgS and EngE and that is absent from or modified in Coh1 so that Coh1 has a lower affinity for the dockerin of these enzymes. Second, different cohesins may function differently during the assembly process of the C. cellulovorans cellulosome, with some cohesins binding certain enzymatic subunits more efficiently than others; perhaps Coh1 will bind other, untested cellulosomal enzymes, but not ExgS or EngE. Finally, Coh1 may not function as a cohesin, since it has only 60% sequence similarity to Coh6. Further experimentation with various cellulosomal enzymes should answer the many questions remaining concerning the cohesin-dockerin interaction.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant DE-FG03-92ER20069 from the Department of Energy and by grant 94-37308-0399 from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer E A, Setter E, Lamed R. Organization and distribution of the cellulosome in Clostridium thermocellum. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:552–559. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.552-559.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doi R H, Tamaru Y. The Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome: an enzyme complex with plant cell wall degrading activity. Chem Rec. 2001;1:24–32. doi: 10.1002/1528-0691(2001)1:1<24::AID-TCR5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fierobe H-P, Pagès S, Belaich A, Champ S, Lexa D, Belaich J-P. Cellulosome from Clostridium cellulolyticum: molecular study of the dockerin/cohesin interaction. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12822–12832. doi: 10.1021/bi9911740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foong F, Hamamoto T, Shoseyov O, Doi R H. Nucleotide sequence and characteristics of endoglucanase gene engB from Clostridium cellulovorans. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1729–1736. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-7-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerngross U, Romaniec M P M, Kobayashi T, Huskisson N S, Demain A L. Sequencing of a Clostridium thermocellum gene (cipA) encoding the cellulosomal SL-protein reveals an unusual degree of internal homology. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:325–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein M A, Takagi M, Hashida S, Shoseyov O, Doi R H, Segel I H. Characterization of the cellulose-binding domain of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein A. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5762–5768. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5762-5768.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruus K, Lua A C, Demain A L, Wu J H D. The anchorage function of CipA (CeIL), a scaffolding protein of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9254–9258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu C-C, Doi R H. Properties of exgS, a gene for a major subunit of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. Gene. 1998;211:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mania C V, Riggs P D, Grandea A G I, Slatko B E, Moran L S, Tagliamonte J A, McReynolds L A, Guan C. A vector to express and purify foreign proteins in Escherichia coli by fusion to, and separation from, maltose binding protein. Gene. 1988;74:365–373. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matano Y, Park J-S, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Cellulose promotes extracellular assembly of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosomes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6952–6956. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6952-6956.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagès S, Belaich A, Belaich J-P, Morag E, Lamed R, Shoham Y, Bayer E A. Species-specificity of the cohesin-dockerin interaction between Clostridium thermocellum and Clostridium cellulolyticum: prediction of specificity determinants of the dockerin domain. Protein. 1997;29:517–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagès S, Bélaïch A, Fierobe H-P, Tardif C, Gaudin C, Bélaïch J-P. Sequence analysis of scaffolding protein CipC and ORFXp, a new cohesin-containing protein in Clostridium cellulolyticum: comparison of various cohesin domains and subcellular localization of ORFXp. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1801–1810. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1801-1810.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pagès S, Belaich A, Tardif C, Reverbel-Leroy C, Gaudin C, Belaich J-P. Interaction between the endoglucanase CelA and the scaffolding protein CipC of the Clostridium cellulolyticum cellulosome. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2279–2286. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2279-2286.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salamitou S, Raynaud O, Lemaire M, Coughlan M, Béguin P, Aubert J-P. Recognition specificity of the duplicated segments present in Clostridium thermocellum endoglucanase CelD and in the cellulosome-integrating protein CipA. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2822–2827. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2822-2827.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoseyov O, Doi R H. Essential 170 kDa subunit for degradation of crystalline cellulose by Clostridium cellulovorans cellulase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2192–2195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoseyov O, Takagi M, Goldstein M, Doi R H. Primary sequence analysis of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose binding protein A (CbpA) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3483–3487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sleat R, Mah R A, Robinson R. Isolation and characterization of an anaerobic, cellulolytic bacterium, Clostridium cellulovorans sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:88–93. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.1.88-93.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takagi M, Hashida S, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. The hydrophobic repeated domain of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein (CbpA) has specific interactions with endoglucanases. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7119–7122. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.7119-7122.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamaru Y, Doi R H. Three surface layer homology domains at the N terminus of the Clostridium cellulovorans major cellulosomal subunit EngE. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3270–3276. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3270-3276.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W K, Kruus K, Wu J H D. Cloning and DNA sequence of the gene coding for Clostridium thermocellum cellulase SS (CelS), a major cellulosome component. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1293–1302. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1293-1302.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaron S, Morag E, Bayer E A, Lamed R, Shoham Y. Expression, purification and subunit-binding properties of cohesins 2 and 3 of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00074-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]