ABSTRACT

Maintenance of bone integrity is mediated by the balanced actions of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Because macroautophagy/autophagy regulates osteoblast mineralization, osteoclast differentiation, and their secretion from osteoclast cells, autophagy deficiency in osteoblasts or osteoclasts can disrupt this balance. However, it remains unclear whether upregulation of autophagy becomes beneficial for suppression of bone-associated diseases. In this study, we found that genetic upregulation of autophagy in osteoblasts facilitated bone formation. We generated mice in which autophagy was specifically upregulated in osteoblasts by deleting the gene encoding RUBCN/Rubicon, a negative regulator of autophagy. The rubcnflox/flox;Sp7/Osterix-Cre mice showed progressive skeletal abnormalities in femur bones. Consistent with this, RUBCN deficiency in osteoblasts resulted in elevated differentiation and mineralization, as well as an increase in the elevated expression of key transcription factors involved in osteoblast function such as Runx2 and Bglap/Osteocalcin. Furthermore, RUBCN deficiency in osteoblasts accelerated autophagic degradation of NOTCH intracellular domain (NICD) and downregulated the NOTCH signaling pathway, which negatively regulates osteoblast differentiation. Notably, osteoblast-specific deletion of RUBCN alleviated the phenotype in a mouse model of osteoporosis. We conclude that RUBCN is a key regulator of bone homeostasis. On the basis of these findings, we propose that medications targeting RUBCN or autophagic degradation of NICD could be used to treat age-related osteoporosis and bone fracture.

Abbreviations: ALPL: alkaline phosphatase, liver/bone/kidney; BCIP/NBT: 5-bromo-4-chloro-3ʹ-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium; BMD: bone mineral density; BV/TV: bone volume/total bone volume; MAP1LC3/LC3: microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; MTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase; NICD: NOTCH intracellular domain; RB1CC1/FIP200: RB1-inducible coiled-coil 1; RUBCN/Rubicon: RUN domain and cysteine-rich domain containing, Beclin 1-interacting protein; SERM: selective estrogen receptor modulator; TNFRSF11B/OCIF: tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 11b (osteoprotegerin)

KEYWORDS: Bone remodeling, differentiation, mineralization, NICD, osteoblast, RUBCN, Rubicon

Introduction

A bone is a complex organ in which several cell types act together in a coordinated manner within a mineralized matrix [1]. Bone homeostasis is mediated by bone remodeling, a process maintained by the balanced actions of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, which promote the resorption and formation of bones, respectively. An imbalance in these processes results in loss of skeletal structure/function and diseases such as osteopetrosis and osteoporosis [2].

Autophagy is an intracellular degradation pathway that degrades and recycles cytoplasmic constituents [3,4]. In response to a starvation signal, a cup-shaped double-membrane structure called the phagophore is generated de novo, followed by the formation of an autophagosome engulfing the cytoplasmic constituents. Following fusion with lysosomes, the contents of autophagosomes are digested [5–7]. This provides the cells with backup energy and building blocks that are needed for survival during starvation. In addition to nonselective autophagy, selective forms of autophagy degrade targets such as invading bacteria, damaged organelles, and protein aggregates. Even without exogenous stimuli, basal autophagy constitutively works to maintain cellular homeostasis. Because autophagy maintains homeostasis of tissues, including bone, these activities suppress a wide range of diseases [8–10].

A genome-wide association study of wrist bone mineral density highlighted a significant association between the autophagy pathway and osteoporosis [11]. In fact, osteoblast-specific autophagy deficiency due to osteoblast-specific deletion of Atg5 results in a phenotype that resembles age-related low bone mass [12]. In mice, osteoblast-specific deletion of Rb1cc1/Fip200, a gene essential for autophagy, inhibits the mineralization activity of osteoblasts, resulting in low bone density [13]. Together, these observations show that autophagy plays a significant role in skeletal homeostasis and suggest that reduced autophagic activity in osteocytes during aging is likely a major cause of age-associated bone loss.

Hence, it is reasonable to speculate that induction of autophagy would be beneficial for bone-associated diseases. Indeed, administration of the MTOR inhibitor everolimus results in a reduction in the number of osteoclasts and upregulation of osteoblast functions associated with mineralization, thereby alleviating a symptom of osteoporosis [14]. However, because MTOR has a broad range of functions outside of autophagy, it remains unclear whether the beneficial effect is a result of an increase in bona fide autophagy. In addition, administration of everolimus causes systemic changes in autophagy that are expected to affect both osteoclasts and osteoblasts, masking the contribution of each individual cell type to the symptoms.

In this study, we used a genetic approach to investigate whether upregulation of autophagy promotes bone formation. RUBCN inhibits fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes, which leads to generation of autolysosomes and degradation of autophagic cargo by lysosomal enzymes. Hence, depletion of RUBCN results in upregulation of autophagic flux, and loss of RUBCN in mice causes upregulation of autophagy in vivo. Strikingly, accumulation of RUBCN is a pathological event observed in liver diseases [15]. Moreover, RUBCN levels increase with age, suggesting that pharmacological applications targeting RUBCN have the potential to treat a wide range of age-associated diseases [16]. This raises the question of how RUBCN confers a selective advantage in evolution. One idea is that excessive autophagy is harmful under some conditions. Indeed, recently we showed that adipocyte-specific knockout of Rubcn causes excess autophagy in adipocytes, resulting in decreased adipocyte function and metabolic disorder, suggesting a need for a factor that can limit the rate of autophagy under certain conditions [17].

Here, we show that the increase in autophagy in osteoblasts results in a range of changes that support osteoblast function. Importantly, we found that osteoblast-specific deletion of RUBCN alleviates the symptoms of osteoporosis in a mouse model. This observation is consistent with the idea that inhibition of RUBCN in osteoblasts represents a potential therapeutic target for age-associated bone disease.

Result

To determine whether osteoblast-specific upregulation of autophagy can increase osteoblast function, we used Sp7/Osterix-Cre mice, in which expression of Cre-recombinase expression is activated before osteoblast differentiation [18]. Considering the previous study showing that Sp7-Cre transgenic mice exhibit severe hypomineralization from an early stage of development [19], we tested whether the mice might show any changes in the bone phenotype even in our experimental condition. We also tested Rubcnflox/flox or Atg5flox/flox mice for the phenotype as well. We found that the Sp7-Cre,Rubcnflox/flox, or Atg5flox/flox did not show significant changes in the bone mineral density, BV/TV (bone mineral density and bone volume), and bone mineral contents from C53BL6J wild-type mice except for the slight reduction in bone mineral contents of the Sp7-Cre mice (Figure S1A, S1B and S1C). Moreover, to eliminate the possibility that hormonal status affects bone phenotypes [20], we used male mice except in the ovary removal experiments described below. We used young mice (12 weeks of age) because aged mice exhibit bone abnormalities such as osteoporosis. We crossed the Sp7-Cre mice with Rubcnflox/flox mice and then analyzed bone formation in the resultant rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice. Immunoblotting confirmed that RUBCN was conditionally deleted in this model (Figure S1D). We also conducted PCR genotyping in osteoblasts purified from 12-week-old mice of control, rubcnflox/floxSp7-Cre,atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre, and rubcnflox/flox;atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice. We confirmed genomic deletion of Rubcn in osteoblasts of rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre and rubcnflox/flox;atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice and deletion of Atg5 in osteoblasts of atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre and rubcnflox/flox;atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice (Figure S1E).

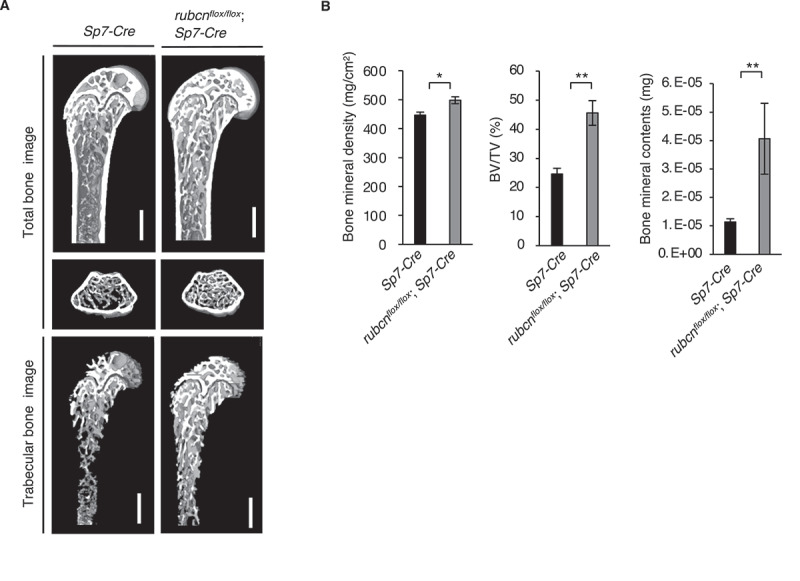

Micro computed tomography (CT) revealed that rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice had higher BV/TV than control Sp7-Cre littermates at the age of 12 weeks (Figure 1A and B). To eliminate the possibility rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice had larger bones, we measured the femur bone length and weight of 12 Sp7-Cre background mice and 12 rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice; we observed no significant difference between them (Figure S1F).

Figure 1.

Bone mineral density, bone volume (BV/TV), and bone mineral contents are significantly elevated in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice. (A) Representative images of total bone and trabecular bone of control male mice in Sp7-Cre background and rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre male mice on normal chow. Bone images were acquired by micro computed tomography and analyzed using the TRI/3D-Bone software (RATOC Systems). Scale bars: 500 μm. (B) Bone mineral density (left), bone volume (middle), and bone mineral contents (right) of control and rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice on normal chow. Rubcn+/+;Sp7-Cre (n = 18). rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre (n = 12). Three of these indexes were significantly elevated in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice. All data are expressed as means ± SD. Data were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. P values from left to right: 0.019, 0.002, 0.006. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; N.S. not significant.

Autophagy flux assay confirmed a significant increase in basal autophagy in primary osteoblasts from rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice, suggesting that the bone phenotypes were due to upregulation of autophagy (Figure S2A and S2B). To obtain direct evidence that autophagy is upregulated in the model system, we performed electron microscopy. Autophagosome formation was significantly increased in primary cultured rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre osteoblasts that had been starved for 2 h to induce autophagy (Figure S2C and S2D), indicating that autophagy is upregulated in rubcn-deleted osteoblasts.

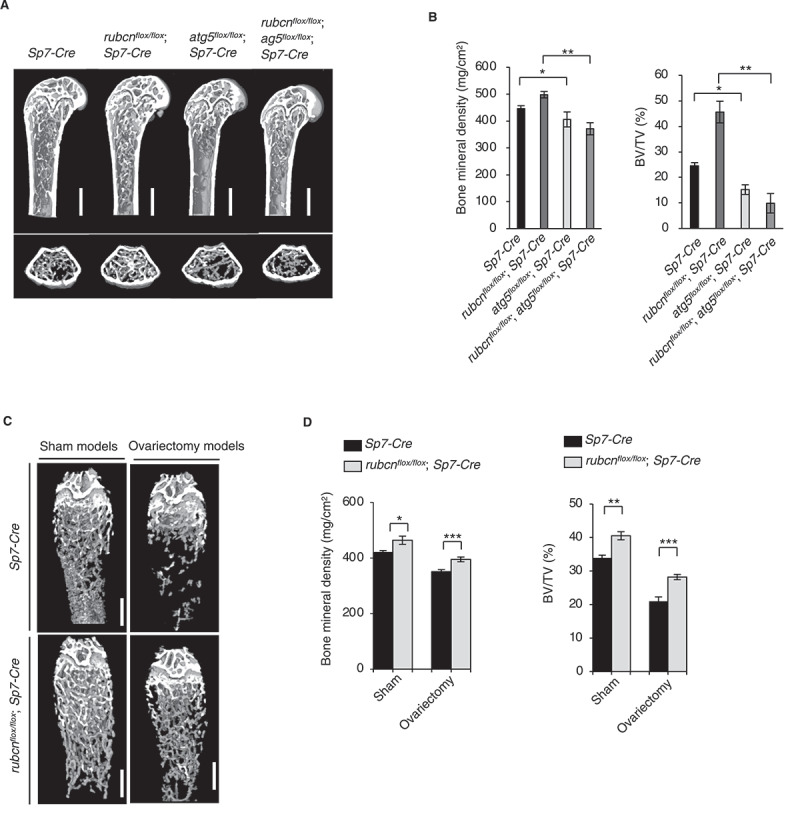

To confirm the autophagy dependency of the phenotype in vivo, we investigated whether simultaneous genetic ablation of Atg5 and Rubcn would abolish the phenotype. A previous study showed that atg5flox/flox;Col1a-Cre mice, in which Cre is driven by a promoter that functions with high efficiency in osteoblasts, exhibit significantly underdeveloped trabecular formation [12]. Consistent with this, atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice had significantly reduced bone mineral density and BV/TV (Figure 2A and B). Notably, we observed a similar phenotype even in rubcnflox/flox;atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice (Figure 2A and B), suggesting an epistatic relationship of Atg5 to Rubcn with regard to this phenotype. Therefore, we conclude that the increased bone formation in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice was autophagy-dependent. Supporting these CT data, we assessed other histomorphometric parameters. In the histomorphometric data, Tb.N, Tb.Sp., and mineral apposition rate revealed similar dynamic effects of RUBCN inactivation on bone morphology (Figure S3A, S3B and S3C).

Figure 2.

Bone volume in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre male mice increased in an autophagy-dependent manner relative to that in Sp7/Osterix-Cre male mice. Bone mineral density and BV/TV in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice were significantly higher in an experimental estrogen-deprived osteoporosis model. (A) Representative images of Rubcn+/+;Sp7-Cre (n = 18), rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre (n = 12), atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre (n = 6), and rubcnflox/flox;atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre (n = 6) mice. Scale bars: 500 μm. (B) Bone mineral density (left) and bone volume (right) of Rubcn+/+;Sp7-Cre,rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre,atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre, and rubcnflox/flox;atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice. (C) Representative cancellous bone images of control and rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre in ovariectomy models; sham-operated mice were used as controls. Scale bars: 500 μm. (D) Bone mineral density (upper) and bone volume (lower) of control and rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice in sham and ovariectomy models. n = 6. Both indexes were significantly elevated in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre and significantly reduced in atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre and rubcnflox/flox;atg5flox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice relative to controls. All data are expressed as means ± SD. Data were analyzed by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. P values from left to right: 0.001, 0.001, 0.027, 0.001. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; N.S. not significant.

Next, we sought to determine whether the osteoblast-specific increase in autophagy could improve the symptoms of bone diseases. To this end, we used an estrogen-deprived osteoporosis model created by surgical removal of both ovaries. Four weeks after ovary resection, we measured the bone density of the distal femur. Initially, nine wild-type mice were bilaterally ovariectomized, and nine sham models were incised and sutured as a control. Bone mineral density and BV/TV of the ovariectomized model decreased by 15.2% (sham model: 419.7 ± 6.8 mg/cm3, ovariectomy model: 350.8 ± 7.1 mg/cm3) and 38.8% (sham model: 33.9 ± 0.8%, ovariectomy model: 21.0 ± 1.3%), respectively, confirming that the model was suitable for the subsequent experiments. Next, the same ovariectomy method was performed in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice to induce osteoporosis. Bone mineral density and BV/TV in ovariectomized rubcnflox/floxSp7-Cre mice were higher those in ovariectomized wild-type mice by 9.8% (wild type: 350.8 ± 7.1 mg/cm3, rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre: 394.9 ± 8.5 mg/cm3) and 30.4% (wild type: 21.0 ± 1.3%, rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre: 28.2 ± 0.8%), respectively (Figure 2C and 2D). These results indicate that upregulation of autophagy in osteoblasts ameliorates osteoporosis in vivo.

To determine the mechanism by which upregulation of autophagy in the absence of RUBCN increases osteoblast function, we performed an osteoblast differentiation assay. To this end, we generated rubcn−/− MC3T3-E1 cells (mouse calvaria–derived cell line used for assessment ALPL activity) using the CRISPR-Cas9 system and tested the capability of the cell line to undergo osteoblast differentiation. RUBCN protein was undetectable in immunoblots of rubcn−/− MC3T3-E1 cells (Figure S3D).

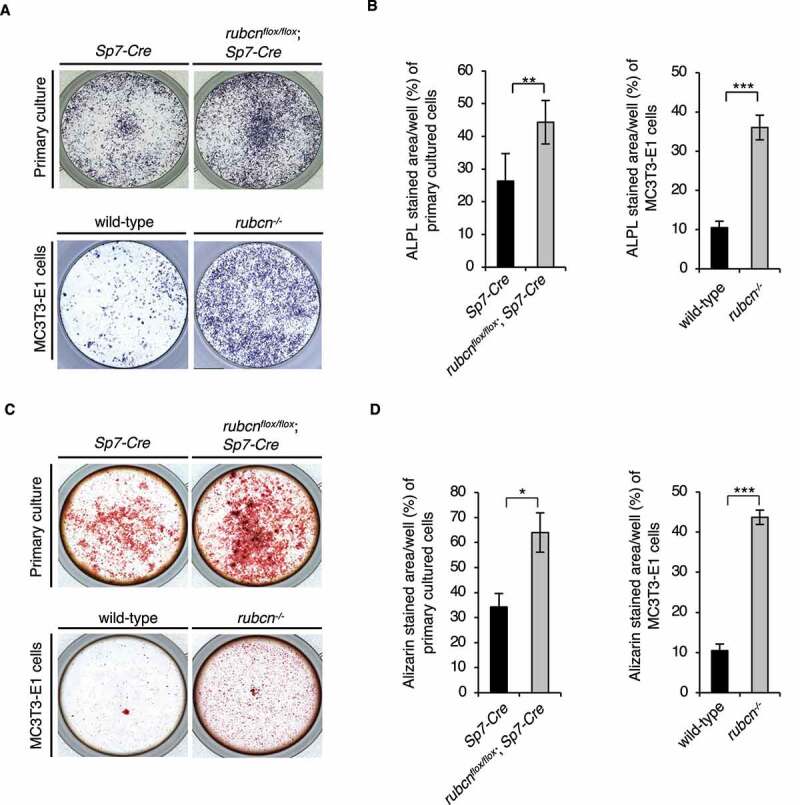

Differentiated osteoblasts were detected by expression of ALPL, which was visualized using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3ʹ-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) as a substrate. rubcn−/− MC3T3-E1 cells exhibited a 3-fold increase in osteoblast differentiation relative to control cells. In a primary cell culture of osteoblasts obtained from the rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice, we also observed a significant increase in osteoblast differentiation. The data suggested that loss of RUBCN accelerates osteoblast differentiation (Figure 3A and B). To determine whether differentiated osteoblasts formed in the absence of RUBCN are functional, we monitored mineralization. Osteoblasts produce large extracellular calcium deposits that can be visualized by Alizarin Red S staining in vitro; in vivo, this process is referred to as mineralization and bone formation in vivo. We observed a significant increase in mineralization in the rubcn−/− MC3T3-E1 cells and primary osteoblasts from rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice relative to control counterparts (Figure 3C and D), suggesting that loss of RUBCN increases osteoblast activity. To clarify the potential involvement of osteoclasts in any unexpected effect of rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre, we conducted histomorphometric analysis to monitor osteoclast dynamics (Figure S3E and S3F). In rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice, the levels of osteoclast surface/bone surface (%; Oc.S/BS) and osteoclast number/bone surface (mm2; N.Oc/BS) were comparable to those of Sp7-Cre background control mice. Thus, it is most likely that Rubcn deficiency in osteoblasts has no significant effect on osteoclast number in vivo, eliminating the possibility that an indirect effect on osteoclasts caused the phenotype observed in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice. Furthermore, we found that levels of the osteocyte marker PDPN/E11 were significantly elevated in primary osteoblasts from rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice (Figure S4A and S4B), suggesting that osteocyte differentiation is also promoted by rubcn deletion. Because we previously showed that RUBCN in several tissues accumulates with age [16], we examined RUBCN levels in osteoblasts from aged mice. However, RUBCN levels were not elevated in aged osteoblasts (Figure S4C and S4D), indicating that age-related regulation of RUBCN is dependent on tissue type.

Figure 3.

Rubcn-knockout osteoblasts exhibit greater differentiation and functional upregulation. (A) Representative ALPL staining images of control and rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre in primary cultured cells and MC3T3-E1 cells. (B) ALPL stained area/well (%) of primary cultured cells and MC3T3-E1 cells was significantly higher in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre cells. (C) Representative Alizarin staining images of control and rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre in primary cultured cells and MC3T3-E1 cells. (D) Alizarin stained area/well (%) of primary cultured cells and MC3T3-E1 cells was significantly higher in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre cells. All data are expressed as means ± SD. Data were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. P values from left to right: 0.003, <0.001, 0.021, <0.001. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; N.S. not significant.

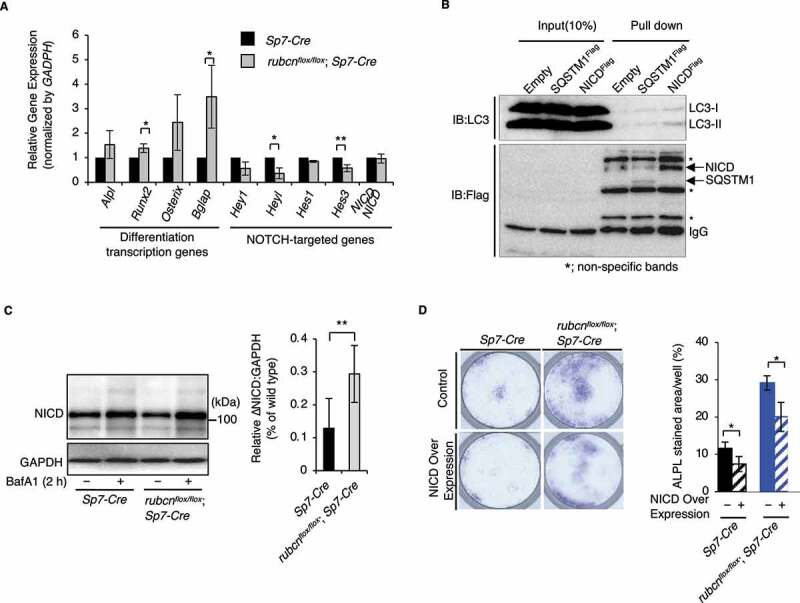

To address the molecular mechanisms underlying increased osteoblast function, we sought to identify the key factor (s) related to osteoblast differentiation. We focused on Notch pathway because Notch receptor and Notch intracellular domain (NICD) were previously shown to be degraded via autophagy [20–23]. NICD is cleaved by gamma-secretase and transported into the nucleus to function as a negative regulator of osteoblast differentiation [24]. We found that NICD was downregulated in osteoblasts from rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice (Figure 4C). This was likely due to increased autophagic degradation of NICD in the rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre osteoblasts, as NICD and LC3 interact directly in murine P19 embryonic carcinoma cells [25]. Immunoprecipitation assays in MC3T3-E1 cells revealed that FLAG-tagged NICD bound to endogenous LC3 as well as the previously known interactor SQSTM1 (Figure 4B). In addition, the autophagic flux of NICD was upregulated in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre osteoblasts, suggesting that Rubcn deficiency results in increased autophagic degradation of NICD in osteoblasts (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Degradation of NICD by autophagy is accelerated under rubcn knockout. NICD signaling is regulated downstream of RUBCN, and NICD directly binds LC3 in osteoblasts. (A) mRNA expression in primary cultured osteoblast cells, as determined by real-time PCR. The NOTCH target genes Hey1, Heyl, Hes1, and Hes3 were downregulated in rubcn-knockout osteoblasts. Bone-forming transcription factors Runx2 and Bglap were significantly upregulated in rubcn-knockout osteoblasts. (B) Immunoprecipitation assay and immunoblotting in cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged NICD. NICD and endogenous LC3 form a complex via direct interaction. (C) Flux assay with bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) revealed that NICD flux was significantly elevated in rubcn-knockout osteoblasts. (D) Representative images of ALPL staining in cells overexpressing NICD (left). Differentiation in rubcn knockout osteoblasts was inhibited by NICD overexpression, as in the controls (right). All data are expressed as means ± SD. Data in (D) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Data in (A) and (C) were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. P values from left to right: 0.034, 0.049, 0.014, 0.008, 0.018, 0.03, 0.029. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; N.S. not significant.

Consistent with this, we found that the Notch targeting genes Hey1, Heyl, Hes1, Hes3, and Hes7, which are downstream targets of NICD, were downregulated in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre osteoblasts (Figure 4A). As expected, transcript levels of NICD did not significantly differ between control and rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre osteoblasts (Figure 4A). These data strongly indicate that the Notch signaling pathway is downregulated at the protein level in the absence of RUBCN due to accelerated degradation of NICD. Notably, downregulation of negative regulators of the osteoblast differentiation in rubcn knockout cells was associated with the upregulation of transcriptional factors involved in differentiation. Runx2 and Bglap/Osteocalcin, which are negatively regulated by NOTCH target genes, were upregulated in the rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre osteoblasts (Figure 4A). Therefore, we conclude that upregulation of autophagic activity promotes osteoblast differentiation through degradation of a negative regulator of differentiation.

To further investigate the idea that NICD degradation is a key event for autophagy upregulation in the absence of RUBCN, we performed an osteoblast differentiation assay by staining for ALPL using BCIP/NBT in cells overexpressing NICD. NICD overexpression decreased osteoblast function even in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre osteoblasts (Figure 4D), suggesting that autophagic degradation of NICD represents a potential therapeutic target for osteoporosis.

Discussion

Because autophagy plays an essential role in maintaining a wide variety of cell types and tissues and suppresses many diseases, including osteoporosis, clinical applications targeting autophagy have attracted attention as novel medications for many diseases. Autophagy inducers such as rapamycin or its analogs have been considered for clinical treatment [26]. Next-generation autophagy inducers may target the autophagy machinery itself, thus avoiding any side effects of the inhibitors of the MTOR pathway, which regulates many other biological pathways. These approaches include activation of BECN1, a mammalian homolog of yeast Vps30/Atg6 [27], or inhibition of RUBCN. Because RUBCN is a negative regulator of autophagy, and pathological accumulation of RUBCN plays a causative role in related diseases [15,16], inhibition of this protein has been studied in order to develop novel medications.

In this report, we showed that the genetic deletion of Rubcn in osteoblasts accelerates osteocytes differentiation and alleviates osteoporosis (Figure S4A and S4B). Accumulation of RUBCN is a pathological feature of liver diseases; accordingly, loss of RUBCN alleviates some of the phenotypes associated with such diseases. By contrast, we observed no significant increase in RUBCN in osteoblasts from 24-month-old (aged) male mice (Figure S4C and S4D), although our previous study showed that RUBCN accumulates with age in diverse tissues [16]. In this in vivo study, we mainly used male mice to eliminate the influence of hormonal status [20]. However, a previous report indicated that the autophagic activity of osteoblasts decreases with age only in female mice [20]. Therefore, it is possible that RUBCN accumulates with age in osteoblasts from female mice. Nonetheless, genetic loss of Rubcn in osteoblasts increases the function of osteoblasts while also upregulating autophagy. Thus, we speculate that any changes in osteoblasts observed in rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice were simply the result of upregulated autophagy.

RUBCN inactivation can lead to increased mineralization not only through increased osteoblast differentiation, but also through increased release of mineralization crystals by autophagic vesicles [28]. Notably, we determined that NICD is a key molecule involved in this phenomenon. The significant effect that we observed on osteoblast differentiation, as well as improvement of osteoporosis by rubcn knockout, suggests that schemes targeting RUBCN in osteoblasts to accelerate autophagic degradation of NICD could be used as precision medicine for autophagy.

Although it remains to be determined how much tissue-specific loss of NICD, which is derived from the C-terminals of both NOTCH1 and NOTCH2, would affect osteoblast differentiation in the mice, the effect of reduction of NICD can be estimated from the phenotype of osteoblast-specific notch2-knockout mice, which have elevated osteoblast function. In these mice, the NOTCH-targeting genes Hey2 and Hes7 are reduced because of NICD reduction [29]. This similarity between the phenotype of osteoblast-specific deletion of Notch2 and that of Rubcn, shown here, supports the idea that induction of autophagic degradation of NICD could improve osteoporosis. Altering the Notch signaling pathway could cause fatal biological events related to neural development and cardiac functions, posing a challenge to developing clinical applications targeting NICD. However, systemic rubcn-knockout mice are born at Mendelian ratios and do not exhibit any detectable abnormality at the birth (data not shown), suggesting that autophagic degradation of NICD is regulated at a level with no significant side effects, even in rubcn-knockout mice. Because autophagy plays roles in embryonic development, as demonstrated by the effects of oocyte-specific deletion of Atg5 [30] and other model systems, it is possible that some system limits the autophagic degradation of NICD during development. Consistent with this, autophagic flux of NICD is not evident in the presence of Rubcn, suggesting that autophagic degradation of NICD is limited to a low level relative to known autophagic substrates such as SQSTM1 and LC3. Interestingly, we observed that a loss of RUBCN in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) does not significantly increase the autophagic flux of NICD, in contrast to the situation in osteoblasts harboring a rubcn deletion (Figure 4C and Figure S4E and S4F). Thus, we speculate that an approach targeting RUBCN would not cause undesired side effects, as expected from the functions of the Notch signaling pathway.

We predict that RUBCN inhibition or modulation of the NICD-LC3 interaction would synergize with current treatments for osteoporosis. To counteract osteoporosis, several clinical approaches have been established that promote osteoblast function or downregulate osteoclast activity. For example, compounds called selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) not only directly inhibit osteoclast function by inducing FASL expression via the osteoclast estrogen receptor [31] but also suppress osteoclast differentiation by promoting expression of TNFRSF11B/osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor/OCIF [32]. Osteoprotegerin expression suppresses osteoclast differentiation via inhibition of RANKL–RANK binding [33]. In another approach, parathyroid hormone treatment induces osteoblastic transcription factors and increases osteoblast function by activating the WNT-CTNNB1/beta-catenin pathway [34]. The combination of SERM and parathyroid hormone is effective [35,36]. Given that expression of a constitutively active isomer of beta-catenin in osteoblasts increases osteoprotegerin expression and suppresses osteoclast differentiation, this combined effect may be a result of expression of the additive increase in osteoprotegerin. The downregulation of the Notch signaling pathway by RUBCN inhibition, as shown here, should synergize with existing approaches that modulate the Wnt signaling pathway. Noteworthy, the induction of osteoblast differentiation by inhibition of the Notch pathway may be caused not only by direct changes in the downstream factors in Notch signaling, but also by activation of the beta-catenin pathway and Wnt signaling, which may activate osteoblast function [37]. This may explain the significant phenotype of the rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre mice, which exhibit milder changes in expression of Notch target genes. Targeting of RUBCN or autophagic degradation of NICD could intensify the bone formation by current medication targeting Wnt pathway. Further mechanistic studies should clarify the molecular mechanism underlying the function of such combined treatment.

Taken together, our findings show that targeting RUBCN itself represents a promising approach for treating osteoporosis, and this strategy could be further strengthened by the specific promotion of the NICD–LC3 interaction. Moreover, this idea could be applied to specialized situations such as bone fracture. A drug delivery system that fixed a stabilizer of NICD and LC3 interactions to an intramedullary nail could promote bone formation at the site of fracture, accelerating fracture healing and creating more durable bone. Further mechanistic analysis and understanding of the role of autophagic degradation of NICD may support the development of novel medications for bone diseases and other autophagy-related disorders.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

The following antibodies and dilution were used: rabbit monoclonal anti-RUBCN (Cell Signaling Technology, 8465; 1:1000), rabbit monoclonal anti-Notch (Cell Signaling Technology, 4853; 1:2000), rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3 (MBL, PM036; 1:2000), and mouse monoclonal anti-PDPN/podoplanin, clone8.1.1 (Merck, MABT1512-25UG; 1:1000). Bafilomycin A1 was purchased from Cayman Chemical.

Animals

Sp7/Osterix-Cre mice [38] and Atg5-floxed mice [39] were obtained from Dr. Masaru Ishii (Department of the Development of Immunology and Cell Biology, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University) and Dr. Noboru Mizushima (The University of Tokyo). Sp7-Cre mice were crossed with Rubcn-floxed mice [40] or Atg5-floxed mice to generate mice that harbored a homozygous deletion of Rubcn or Atg5, respectively, specifically in osteoblasts. All mouse lines used in this study were maintained on a C57BL/6 J background. Unless otherwise specified, all the mice used in the experiments were 12-week-old males. The mice were maintained on normal chow with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. For genotyping, osteoblast cells were collected from femur bone and purified by culture in differentiation induction medium, and PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase (a high-fidelity DNA polymerase developed by Takara Bio) was used for PCR. The PCR program was as follows: denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing for 2 min at 55°C, and extension for 3 min at 55°C (25 cycles). The sequences of the primer pairs used for genotyping are available upon request. Experimental procedures involving mice were approved by the Institutional Committee of Osaka University.

Cell culture

MC3T3-E1 cells were purchased from the RIKEN, cell engineering division. The cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, DMEM D6429) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, P4333).

Primary cultured cells were taken from calvaria of young mice. Calvaria bone of day 1 mice was digested for 15 min at 37°C with osteoblast buffer, which consisted of alpha-MEM (Nacalai tesque, 21,444–05), 0.176% NaHCO3, and 0.008% collagenase (Wako 032–10,534), and fractions were collected after centrifugation at 350 (g) for 5 min, 5 times. Cell suspensions were placed in 10-cm dishes and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Generation of rubcn-deficient MC3T3-E1 cells by CRISPR-Cas9

The Rubcn gene was knocked out in MC3T3-E1 cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. To generate the rubcn−/− MC3T3-E1 cell line, guide RNA for Rubcn exon 5 was inserted into the BbsI restriction site of vector pMRX. The resultant vector was transfected into MC3T3-E1 cells, and GFP-positive cells were sorted by FACS (fluorescence-associated cell sorting) and cultured in 96-well plates with one cell in each well. Four days later, the cells were passaged into 12-well plates, and the rubcn-knockout clones were identified by Western blotting.

Osteoblast differentiation assay

Cell suspensions were incubated with osteoblast differentiation buffer consisting of 50 µM ascorbic acid sodium salt (Wako, 196–01252), 100 nM dexamethasone (Wako, 041–18,861), and 10 mM beta-glycerophosphate (Sigma, G6376). ALPL assay was performed after 7 days, and Alizarin red S (bio medical science, BR-217700041) staining was performed after 21 days.

ALPL staining

Osteoblast cells are incubated for 5 days in osteoblast differentiation buffer. Primary cultures were incubated in 12-well plates, and MC3T3-E1 cells were incubated in 96-well plates. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3). After addition of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3ʹ-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT; Nacalai tesque, 03937–60) and incubation at 37°C for 20 min, the cells were observed by BZ-X700 (All-in-one fluorescence microscope by Keyence).

Alizarin staining

Osteoblast cells are incubated for 4 weeks in osteoblast differentiation buffer. Primary cells were incubated in 12-well plates, and MC3T3-E1 cells were incubated in 96-well plates. Osteoblast differentiation buffer was changed every 2 days, and cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3). Cells in plates were stained with Alizarin Red S (pH 4.0) for 5 min, washed, dried, and observed on a BZ-X700 All-in-one fluorescence microscope (Keyence).

Fluorescence microscope assay

Cells were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde (0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3), and permeabilized with digitonin (100 μg/ml; Nacalai tesque,19,390–91) for 7 min. After staining with primary and secondary antibodies, the cells were observed with a fluorescence microscope (IX83). Microscopy imaging conditions were as follows: microscope, IX83; lens, UIS LANAPO60X/1.42; exposure time, 350 ms; oil, Olympus IMMERSION OIL.

Bone analysis

All mice used in experiments were 12-week-old male mice on a C57BL/6 J background, except that the osteoporosis model mice were 9-week-old females. In the latter experiments, bone images of the distal area of the femur were taken 4 weeks after removal of the ovaries. For scanning bone, the X-ray source set at a voltage of 60 kV, with a current of 120 μA. For accurate images of the trabecular microarchitecture, a voxel size is 10 μm. The scan volume of the femoral midshaft is centered on the point above 750 μm

from growth plate at the distal end of femur, and the depth of the trabecular bone scan area is 300 μm. Bone images were acquired using CT (µCT40, Scanco Medical AG) and analyzed using TRI/3D-Bone software (RATOC Systems). According to the previous report [41], we measured several parameters such as bone mineral density, BV/TV, Tb.N, Tb.Sp, and mineral apposition rate.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR analyses

Mouse tissues were harvested in QIAzol (Qiagen, 79,306) using a Precellys Evolution tissue homogenizer (Bertin). Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, 74,106). cDNA was generated using iScript (Bio-Rad, 1,708,891). qRT-PCR was performed with Power SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems, 4,368,577) on a QuantStudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Four technical replicates were performed for each reaction, with Rplp0/36b4 used as the internal control.

Immunoblotting

Mouse tissues were harvested in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% w:v Triton X-100 [Wako, 04605–250], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.5% sodium deoxycholate [Wako, 190–08313]) using a Precellys Evolution tissue homogenizer (Bertin). The cells were lysed in the same RIPA buffer and quantified by BCA assay (Nacalai Tesque, 06385–00). After addition of 5× SDS buffer, the samples were boiled for 5 min. After centrifugation, protein lysates were separated by 7 or 13% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were stained with Ponceau-S, which were then blocked with 1% skim milk TBS-T (137 mmol Nacl, 68 mmol KCl, 25 mmol Tris, pH7.4, 0.1% w:v Tween 20 (Nacalai Tesque, 23,926–35)) and incubated with specific primary antibodies. Immunoreactive beads were detected using horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, AB_10015289), Luminata Forte (Merck Millipore, WBLUF0500) or ImmunoStar LD (Wako, 290–69,904), and ChemiDoc Touch (Bio-Rad). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Autophagy flux assay

Cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DMEM in the presence or absence of 125 nM bafilomycin A1. The cells were lysed and immunoblotted for LC3. The autophagy flux was calculated by subtracting the densitometry values of LC3-II in samples not treated with bafilomycin A1 from the values in samples treated with bafilomycin A1.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as means ± SD. Data were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism7 (GraphPad Software) or JMP (SAS).

Electron microscopy analysis

Primary cultured rubcnflox/flox;Sp7-Cre osteoblasts were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 h under starvation conditions with 125 nM bafilomycin A1, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide solution at 4°C for 1 h. Cells were embedded in Nissin EM Quetol 812 epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (80-nm thick) were cut with an ultramicrotome. Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed with a Hitachi H-7650 electron microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation) at 80kV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Masaru Ishii (Department of Immunology and Cell Biology, Graduate School of Medicine and Frontier Biosciences, Osaka University) for Sp7/Osterix-Cre mice.

Funding Statement

T.Yo. is supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, HFSP and AMED (Grant Numbers JP18gm0610005 and JP18gm5010001).

Disclosure statement

We thank Dr. Masaru Ishii (Osaka University) for Sp7/Osterix-Cre mice. T.Yo. is supported by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, HFSP grant and AMED (Grant Numbers JP18gm0610005 and JP18gm5010001).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Chen X, Wang Z, Duan N, et al. Osteoblast-osteoclast interactions. Connect Tissue Res. 2018;59(2):99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Matsuo K, Irie N.. Osteoclast-osteoblast communication. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;473(2):201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Xie Z, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(10):1102–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yoshimori T, Noda T. Toward unraveling membrane biogenesis in mammalian autophagy. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20(4):401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dice JF. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2007;3(4):295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6(4):463–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev. 2007;21(22):2861–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132(1):27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, et al. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451(7182):1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Xing Y, Chenchen Z, Jingtao L, et al. Autophagy in bone homeostasis and the onset of osteoporosis. Bone Res. 2019;7:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang L, Guo YF, Liu YZ, et al. Pathway-based genome-wide association analysis identified the importance of regulation-of-autophagy pathway for ultradistal radius BMD. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(7):1572–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nollet M, Santucci-Darmanin S, Breuil V, et al. Autophagy in osteoblasts is involved in mineralization and bone homeostasis. Autophagy. 2014;10(11):1965–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liu F, Fang F, Yuan H, et al. Suppression of autophagy by FIP200 deletion leads to osteopenia in mice through the inhibition of osteoblast terminal differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(11):2414–2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kneissel M, Luong-Nguyen NH, Baptist M, et al. Everolimus suppresses cancellous bone loss, bone resorption, and cathepsin K expression by osteoclasts. Bone. 2004;35(5):1144–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tanaka S, Hikita H, Tatsumi T, et al. Rubicon inhibits autophagy and accelerates hepatocyte apoptosis and lipid accumulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2016;64(6):1994–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nakamura S, Oba M, Suzuki M, et al. Suppression of autophagic activity by Rubicon is a signature of aging. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yamamuro T, Kawabata T, Fukuhara A, et al. Age-dependent loss of adipose Rubicon promotes metabolic disorders via excess autophagy. Nat Commun. 2020 Aug 18;11(1):4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rodda SJ, McMahon AP. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development. 2006;133(16):3231–3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang L, Mishina Y, Liu F, et al. Osterix-Cre transgene causes craniofacial bone development defect. Calcif Tissue Int. 2015;96(2):129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Camuzard O, Santucci-Darmanin S, Breuil V, et al. Sex-specific autophagy modulation in osteoblastic lineage: a critical function to counteract bone loss in female. Oncotarget. 2016;7(41):66416–66428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Barlet JP, Coxam V, Davicco MJ, et al. Animal models of post-menopausal osteoporosis. Reprod Nutr Dev. 1994;34(3):221–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang C, Inzana JA, Mirando AJ, et al. NOTCH signaling in skeletal progenitors is critical for fracture repair. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(4):1471–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wu X, Fleming A, Ricketts T, et al. Autophagy regulates Notch degradation and modulates stem cell development and neurogenesis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zanotti S, Canalis E. Notch and the skeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(4):886–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jia Z, Wang J, Wang W, et al. Autophagy eliminates cytoplasmic beta-catenin and NICD to promote the cardiac differentiation of P19CL6 cells. Cell Signal. 2014;26(11):2299–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Maiuri L, Villella VR, Piacentini M, et al. Defective proteostasis in celiac disease as a new therapeutic target. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(2):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shoji-Kawata S, Sumpter R, Leveno M, et al. Identification of a candidate therapeutic autophagy-inducing peptide. Nature. 2013;494(7436):201–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shanahan CM. Autophagy and matrix vesicles: new partners in vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 2013;83(6):984–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yorgan T, Vollersen N, Riedel C, et al. Osteoblast-specific Notch2 inactivation causes increased trabecular bone mass at specific sites of the appendicular skeleton. Bone. 2016;87:136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tsukamoto S, Kuma A, Murakami M, et al. Autophagy is essential for preimplantation development of mouse embryos. Science. 2008;321(5885):117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nakamura T, Imai Y, Matsumoto T, et al. Estrogen prevents bone loss via estrogen receptor alpha and induction of Fas ligand in osteoclasts. Cell. 2007;130(5):811–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Viereck V, Grundker C, Blaschke S, et al. Raloxifene concurrently stimulates osteoprotegerin and inhibits interleukin-6 production by human trabecular osteoblasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(9):4206–4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Glass DA 2nd, Bialek P, Ahn JD, et al. Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev Cell. 2005;8(5):751–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tamura Y, Kaji H. Parathyroid hormone and Wnt signaling. Clin Calcium. 2013;23(6):847–852. CliCa1306847852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Deal C, Omizo M, Schwartz EN, et al. Combination teriparatide and raloxifene therapy for postmenopausal osteoporosis: results from a 6-month double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(11):1905–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Leder BZ, Tsai JN, Uihlein AV, et al. Two years of Denosumab and teriparatide administration in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (The DATA Extension Study): a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):1694–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zanotti S, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Stadmeyer L, et al. Notch inhibits osteoblast differentiation and causes osteopenia. Endocrinology. 2008;149(8):3890–3899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yang S, Takahashi N, Yamashita T, et al. Muramyl dipeptide enhances osteoclast formation induced by lipopolysaccharide, IL-1 alpha, and TNF-alpha rhrough nucleotide binding oligomerization domain 2 mediated signaling in osteoblasts. J Iimmunol. 2005;175(3):1956–1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441(7095):885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tanaka S, Hikita H, Tatsumi T, et al. Rubicon inhibits autophagy and accelerates hepatocyte apoptosis and lipid accumulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2016;64(6):1994–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, et al. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(7):1468–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.