Abstract

dear editor, Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a life‐threatening rare disease that has a significant impact on patients’ daily activities. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Owing to a lack of awareness of GPP among doctors, this disease is unsatisfactorily diagnosed and inadequately treated. 1 Evidence for the efficacy of current medications is lacking, and no treatments are approved for GPP in Europe or the USA. 2 , 3 , 4 Despite the rarity of GPP, it remains to be conclusively stated whether this disease fulfils all the criteria for European Medicines Agency (EMA) orphan designation. 5 Achieving EMA orphan designation would help to reshape the medical community’s definition and understanding of GPP, in addition to greatly expediting development of effective treatments. Here, we report the outcomes of roundtable meetings between patient advocacy groups (PAGs) and clinical experts regarding the urgent need to classify GPP as an orphan disease.

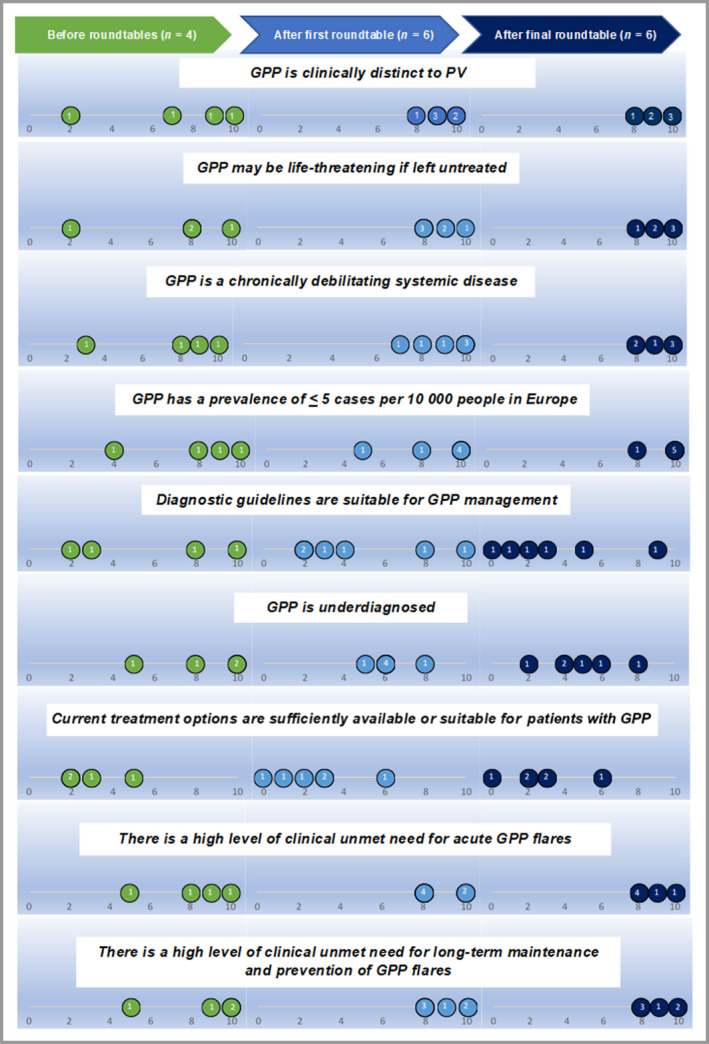

A Delphi approach was used to garner the opinions of participants at three 1‐h virtual roundtable meetings to assess the level of consensus on whether GPP meets the EMA criteria for orphan designation. The meetings were held sequentially on 23 April 2021, 28 April 2021 and 6 May 2021. The initial roundtable meeting was attended by four representatives from three PAGs (European Federation of Psoriasis Patient Associations, Psoriasisforeningen, Denmark and the International Federation of Psoriasis Associations). In addition to the PAG representatives, two clinical experts attended the second and third meetings. During the meetings, participants were asked to provide their opinions verbally on the following prespecified topics, which cover all the EMA criteria that GPP would need to fulfil in order to receive orphan designation: (i) whether GPP is life‐threatening or chronically debilitating; (ii) whether the prevalence of GPP is less than five cases per 10 000 people and (iii) whether the methods of diagnosis, prevention or treatment of GPP are satisfactory. 5 All participants were informed of the topics for discussion in advance by email. To assess the level of consensus on whether GPP meets the EMA criteria for orphan designation, each participant was asked to rate on a scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree) the extent to which they agreed with a series of statements about the three topics listed in Figure 1. Using this methodology, the PAG representatives (before the first meeting and after all three meetings) and the clinical experts (after the second and third meetings) were asked to provide their opinions anonymously in order to determine Delphi consensus on whether GPP meets the EMA orphan criteria.

Figure 1.

Level of agreement with statements regarding generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP).

Participants were asked to what extent they agreed with the statements, which relate to European Medicines Agency criteria for orphan designation. Participants rated their level of agreement from 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). Numbers inside the circles refer to the number of participants who gave each score. Only patient advocacy group representatives rated the statements before the roundtable meetings, whereas clinical experts also rated the statements after the roundtable meetings. PV, psoriasis vulgaris. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

During the roundtable meetings, there was clear consensus that GPP fits all the EMA orphan disease criteria (Figure 1). Participants unanimously agreed that GPP is clinically and pathogenetically distinct from psoriasis vulgaris, being characterized by acute flares of painful, itchy pustules that are often widespread across the body, accompanied by fever. While GPP is rightly recognized as a distinct psoriatic disease, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 11th revision does not differentiate GPP well enough from other forms of psoriasis. All participants agreed that GPP is life‐threatening, with a long‐term debilitating course and unpredictable flares. GPP greatly impacts patients physically and psychologically, adversely affecting performance of everyday tasks, employment, sleep and relationships. The term ‘skin failure’ was proposed to reflect the catastrophic endpoints associated with inflammation of the skin and other organs. All participants agreed that GPP has a prevalence of less than five cases per 10 000 people in Europe, possibly between one and 90 cases per million, 6 , 7 although epidemiological studies are lacking. Current guidelines are unsuitable for diagnosis of GPP, and there are high levels of unmet need for the treatment and prevention of GPP flares. No effective therapies are approved for GPP, and evidence of their efficacy is poor.

In summary, there was clear consensus that GPP fits all the EMA orphan disease criteria, based on published evidence and on professional experience. There is a need to reshape the medical community’s understanding and approach to GPP management. To heighten awareness of GPP, and to emphasize its clinical and pathogenic distinction from other forms of psoriasis, we recommend that future editions of the ICD should provide a better definition of GPP and where it belongs on the spectrum of psoriatic disease. We also recommend the use of the term ‘skin failure’ to help stakeholders (clinicians, PAGs, insurers and medicine licensing authorities) to better understand the potentially catastrophic impact of GPP from the patient’s perspective.

EMA orphan designation for GPP should greatly expedite development of effective treatments for this life‐threatening and debilitating disease. If medical authorities recognize the urgent need to improve access to novel treatments for GPP and provide patients with ongoing specialist support, then we believe that the outlook is hopeful.

Author contributions

Jan Koren: Conceptualization (equal); supervision (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Sicily Mburu: Conceptualization (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). David Trigos: Conceptualization (equal); supervision (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Giovanni Damiani: Conceptualization (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Luigi Naldi: Conceptualization (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); visualization (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Fortis Pharma Communications, UK, with financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim (BI). The opinions expressed are entirely the authors’ own; BI did not review the manuscript. We would like to thank Lars Werner (Psoriasisforeningen, Copenhagen, Denmark) who also participated as a PAG representative in all roundtable meetings and questionnaires.

Funding sources: The organization of the meeting series and editorial support for this manuscript were funded by Boehringer Ingelheim (BI). BI did not participate in the meetings or have sight of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: G.D. has received honoraria from Novartis, Amgen and Galderma for participation on advisory boards, and grants from Almirall for participation as an investigator, and speaker honoraria from Novartis and Sanofi. S.M. holds the position of Scientific Officer at the International Federation of Psoriasis Associations, an international nonprofit organization supported by sponsorships and grants from industry partners. L.N. has received honoraria as a scientific consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Novartis and Sanofi. J.K. and D.T. hold the positions of president and vice‐president, respectively, at the European Federation of Psoriasis Patient Associations.

Data availability: this manuscript is based on discussions between patient advocacy groups and clinical experts. These discussions were based on published evidence and on professional experience.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This manuscript is based on discussions between patient advocacy groups and clinical experts. These discussions were based on published evidence and on professional experience.

References

- 1. Reisner DV, Johnsson FD, Kotowsky N et al. Impact of generalized pustular psoriasis from the perspective of people living with the condition: results of an online survey. Am J Clin Dermatol 2022; 23 (Suppl. 1):65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neuhauser R, Eyerich K, Boehner A. Generalized pustular psoriasis—dawn of a new era in targeted immunotherapy. Exp Dermatol 2020; 29:1088–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morita A, Kotowsky N, Gao R et al. Patient characteristics and burden of disease in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: results from the Medical Data Vision claims database. J Dermatol 2021; 48:1463–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2019; 15:907–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. European Medicines Agency . Orphan designation: overview. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/orphan-designation-overview (last accessed 17 February 2022).

- 6. Orphanet . Generalized pustular psoriasis. Available at: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi‐bin/Disease_Search.php?lng=EN&data_id=19519&Disease_Disease_Search_diseaseGroup=Generalised‐pustular‐psoriasis&Disease_Disease_Search_diseaseType=Pat&Disease(s)/groupofdiseases=Generalized‐pustular‐psoriasis&title=Generalizedpustularpsoriasis&search=Disease_Search_Simple(last accessed 17 February 2022).

- 7. Löfvendahl S, Norlin JM, Schmitt‐Egenolf M. Prevalence and incidence of generalized pustular psoriasis in Sweden: a population‐based register study. Br J Dermatol 2022; DOI: bjd.20966.10.1111/bjd.20966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript is based on discussions between patient advocacy groups and clinical experts. These discussions were based on published evidence and on professional experience.