Abstract

Aromatic groups are key mediators of protein–membrane association at cell surfaces, contributing to hydrophobic effects and π‐membrane interactions. Here we show electrostatic and hydrophobic influences of aromatic ring substituents on membrane affinity and cell uptake of helical, cyclic and cell penetrating peptides. Hydrophobicity is important, but subtle changes in electrostatic surface potential, dipoles and polarizability also enhance association with phospholipid membranes and cell uptake. A combination of fluorine and sulfur substituents on an aromatic ring induces microdipoles that enhance cell uptake of 12‐residue peptide inhibitors of p53‐HDM2 interaction and of cell‐penetrating cyclic peptides. These aromatic motifs can be readily inserted into peptide sidechains to enhance their cell uptake.

Keywords: Arylation, Cell-Penetrating Peptide, Fluorine, Sulfur

Substituents that increase hydrophobicity, electrostatic surface potential, polarizability and dipole moment of aromatic rings enhance binding to phospholipid bilayers and cell membranes, and increase peptide uptake into cells.

A major limitation to exploiting peptides and proteins is their high polarity, which impedes cell uptake. [1] A clue to enhancing cell uptake is the prevalence of aromatic amino acids (Trp, Tyr, Phe) in proteins at lipid–water and protein–membrane interfaces.[ 2 , 3 ] Such amino acids confer favourable free energy for insertion into lipid bilayers, Trp having the highest affinity on the Wimley–White interfacial hydrophobicity scale. [2a] Membrane association of aromatic groups is influenced by multiple factors, with hydrophobicity driving them from water into lipid and electrostatics possibly promoting membrane contact.[ 2 , 3 ] Trp has the largest dipole and interacts more strongly with lipid bilayers.[ 2 , 3 , 4 ] Cation–π interactions in proteins are also more common for Trp than Phe. [5] Aromatic sidechains can increase peptide uptake into cells. [6] Here we investigate influences of aromatic substituents on electrostatic vs hydrophobic surfaces. We then show if their presence in an amino acid of helical, cyclic and cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) enhances phospholipid bilayer association and cell uptake.

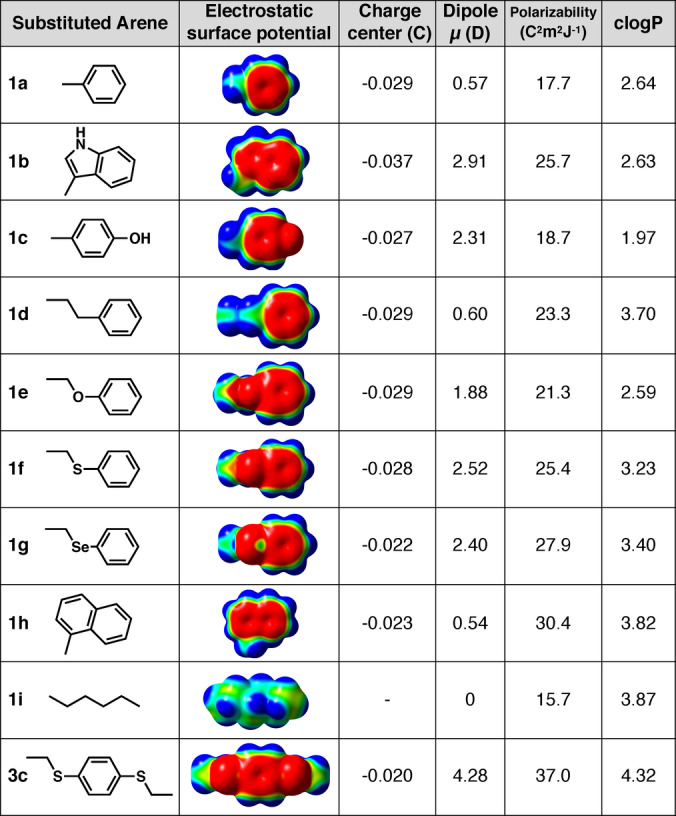

We performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate how substituents alter the electrostatic and hydrophobic surface of an aromatic ring (Figures 1 and 2). Arenes 1 a and 1 b, corresponding to Phe and Trp sidechains, have the same hydrophobicity (clogP). However, 1 b has greater negative charge at the center of the π‐cloud of indole, a larger dipole moment, and greater polarizability than 1 a (Figure 1). Introducing an O‐, S‐ or Se‐heteroatom, with an electron lone pair that can alter the π‐cloud, does not substantially vary negative charge at the centre of the aromatic ring (1 a, 1 d vs 1 c, 1 e–g), but does increase the electric dipole and decrease hydrophobicity especially for O‐aryl (1 c, 1 e). Similar to 1 a, the naphthyl arene 1 h has a smaller dipole, but is more polarizable and hydrophobic due to its enlarged π‐face. A S/Se‐arene (1 f, 1 g) is more polarizable, a property that can increase van der Waals dispersion forces and dipole‐dipole interactions with membranes. [5a] For comparison, hexane (1 i) has greater hydrophobicity but negligible electrostatic properties.

Figure 1.

Electrostatic and hydrophobic properties of arenes. DFT‐calculated (Gaussian: B3LYP/6‐311+ +G(2d,2p) level of theory) electrostatic surface potentials (−7.0 kcal mol−1 (red) to +7.0 kcal mol−1 (blue)) and clogP (ChemDraw 20.0).

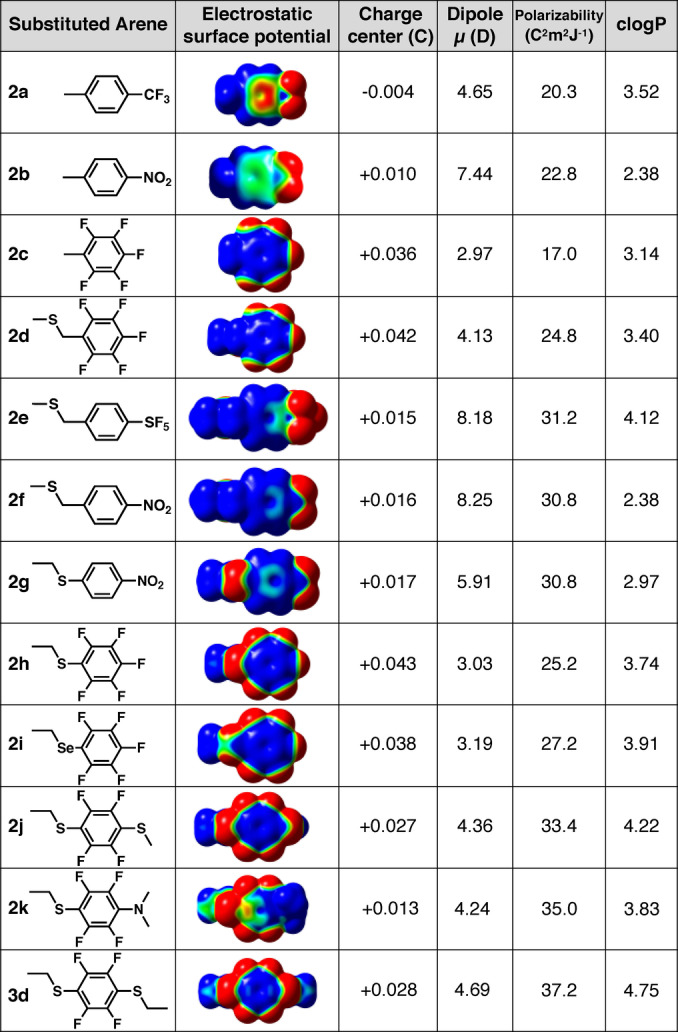

Figure 2.

Electrostatic and hydrophobic properties of arenes. DFT‐calculated (Gaussian: B3LYP/6‐311+ +G(2d,2p) level of theory) electrostatic surface potentials (−7.0 kcal mol−1 (red) to +7.0 kcal mol−1 (blue)) and clogP (Chemdraw 20.0).

Electron withdrawing trifluoromethyl, nitro, pentafluoro‐sulfanyl (SF5) or fluoro (2 a–k) substituents switch the electrostatic surface potential to positive at the centre of the aromatic ring (Figure 2). Nitro and SF5 groups induce a strong dipole but different hydrophobicity, with nitro almost two logP units less hydrophobic than SF5 (2 f vs 2 e). Relative to 1 a, perfluorination (2 c) also increases dipole moment (μ) and hydrophobicity (clogP), but has little effect on polarizability. Combining perfluorination and S‐arylation gives an electron‐deficient arene (2 h–k) with high hydrophobicity, polarizability, dipole and a positive electrostatic centre (Figure 2) that may disfavour cation–π interactions but favour association with negatively charged membrane phospholipids.

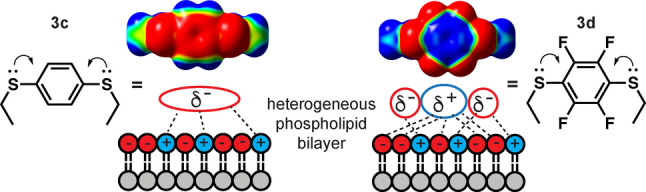

To understand how combinations of fluorine and sulfur substituents might affect interactions with membranes and influence cell uptake, we first computationally studied the electronic properties of arenes 3 a–d (Figure 3), featuring symmetrical para‐substituents in configurations where a sulfur electron lone pair projects into the same face of the aromatic ring.

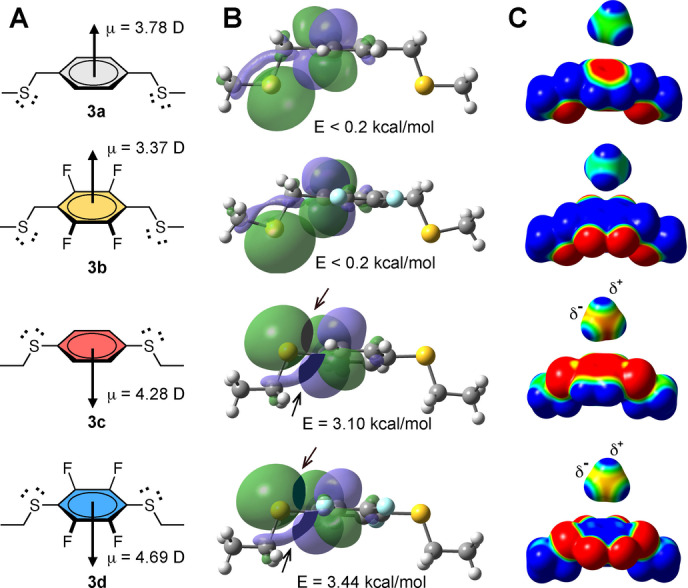

Figure 3.

Effect of sulfur substituents. A) Structures 3 a–d and calculated dipole moments (μ). B) Calculated Natural Bond Orbitals (NBO7) and overlap energies (E) between sulfur lone pair orbital (3p) and π* (antibonding) orbital of arene in 3 a–3 d. C) Electrostatic surface potential map of 3 a–d showing greater induced polarization of an approaching CH4 molecule by aryl sulfides (3 c, 3 d) than alkyl sulfides (3 a, 3 b). Surface potential −7.0 kcal mol−1 (red) to +7.0 kcal mol−1 (blue).

S‐substituted arenes 3 c and 3 d have stronger and opposite dipoles to C‐substituted arenes 3 a and 3 b (Figure 3A). Natural bond orbital (NBO) calculations support orbital overlap between electron pairs on sulfur (3p orbitals) and the π‐system (π* and σ* orbitals) in 3 c and 3 d, but not in 3 a or 3 b (Figures 3B, S1). DFT calculations reveal that 3 c and 3 d, with two sulfur atoms adjacent to the arene, are more effective in polarizing a methane molecule, approximating the smallest lipid. They induce a weak dipole in methane resulting in a small attraction to the arene (Figure 3C).

Next, we systematically investigated the arenes (Figures 1–3) incorporated into side chains of peptides (Figures 4 and 6) or in crosslinkers of cyclic peptides (Figure 7). The motif 3 d has been used to staple peptides where two cysteines crosslink via hexafluorobenzene and reportedly increases cell uptake, but only in cyclic peptides created by S‐aryl stapling. [7] Figures 4, 5, 6, 7 provide new insights on the influences of electrostatic and hydrophobic surfaces on membrane association and cell uptake of peptides.

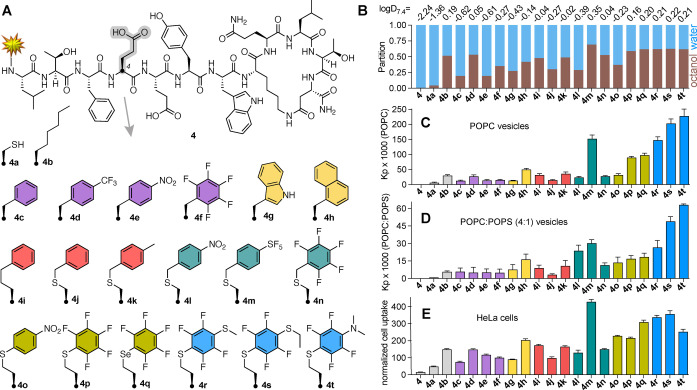

Figure 4.

Effects of appended aromatic amino acids on membrane and cell uptake of helix‐constrained peptides. A) Structure of 4 and analogues 4 a–h with Cys/Hcy aryl‐substitutions at position 4. Yellow star represents N‐terminal derivatization with FITC‐βAla‐. B) Fractional partition in 1‐octanol/10 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (1 : 1, v/v), used to determine logD 7.4 (top, mean of n ≥ 2). C), D) Partition coefficient (K p) for peptides 4 and 4 a–h in C) POPC or D) POPC : POPS (4 : 1) determined by fluorescence polarization after titration of peptides with vesicles in 10 mM HEPES/10 mM NaCl (pH 7.4). Error bars=mean±SD. E) Uptake of peptides (5 μM, 37 °C, 1 h) into HeLa cells measured (flow cytometry) as median fluorescence intensity normalized to 100 % for TAT. One‐way ANOVA, P values =ns (4 a), 0.011 * (4 c, 4 g), 0.0017 ** (4 j), < 0.0001 **** (all others). Error bars=mean±SEM.

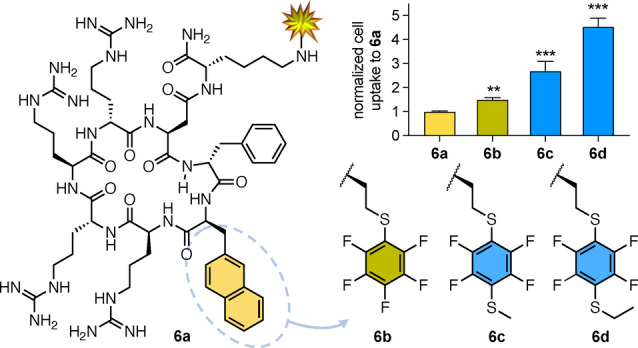

Figure 6.

Uptake of cyclic hexapeptides 6 a–d (5 μM) by HeLa cells (37 °C, 1 h) measured by median fluorescence intensity, normalized to uptake of 6 a [12]. Error bars=mean±SEM. One‐way ANOVA, ** P value =0.004, *** P value <0.001.

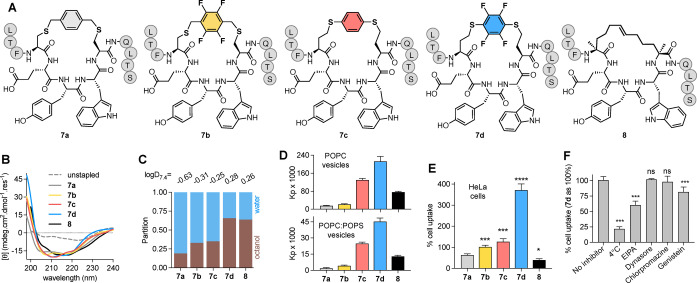

Figure 7.

Effects of arene crosslink on membrane and cell uptake of helix‐constrained peptides. A) Stapled pDI peptides 7 a–d and 8, modified at the N‐terminus with FITC‐βAla‐. B) CD spectra of peptides (20 μM) in 0.5 mM POPC vesicles, 10 mM HEPES/10 mM NaCl buffer pH 7.4. C) Fractional partition in 1‐octanol/10 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (1 : 1, v/v) used to determine logD7.4 (top row, mean n≥2). D) Partition coefficients (K p) from binding curves of titration with POPC or POPC : POPS (4 : 1) vesicles in 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl pH 7.4 buffer followed by FP. Error bars=mean±SD. E) Percent (mean±SEM) uptake of peptides 7 a–d vs 8 (5 μM, 1 h) into HeLa cells measured by flow cytometry. Fluorescence normalized to TAT (5 μM) as 100 % uptake, 37 °C. F) Uptake of 7 d in presence of endocytosis inhibitors: 4 °C (active endocytosis); 50 μM EIPA (macropinocytosis); 50 μM Dynasore or 10 μM Chlorpromazine (clathrin‐mediated endocytosis); or 500 μM Genistein (caveolin‐mediated endocytosis). One‐way ANOVA, P values: * (P=0.01), *** (P<0.001), **** (P<0.0001), ns (not significant) vs 7 a (E) or vs no inhibitor (F).

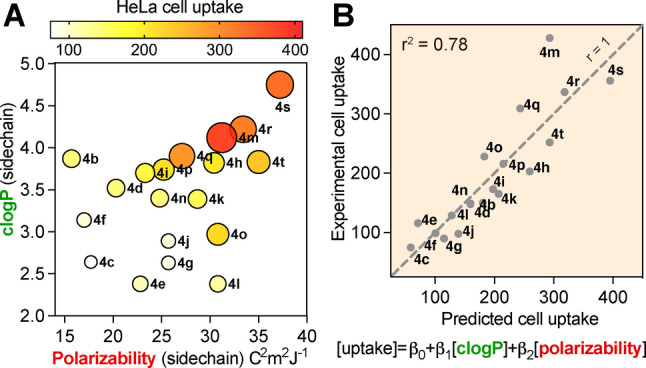

Figure 5.

A) Plot associating polarizability and clogP of the arene (Figures 1 and 2), incorporated as a sidechain at position 4 of peptides 4 b–t, with the extent of uptake into HeLa cells (as in Figure 4E) shown by colour gradient and also circle size. B) Combined effect of polarizability and hydrophobicity on HeLa cell uptake fits the model: [uptake]=β0+β1[clogP]+β2[polarizability], with r 2 =0.78, P values =0.0002 (β1) and 0.0039 (β2). See Figures S7, S8 for full analysis.

First, we examined a series of helix‐constrained lactam‐stapled peptides based on 4 (Figure 4A), [8a] derived from a peptide called pDI (LTFEHYWAQLTS) [9] known to bind with high affinity to oncogenic proteins HDM2 and HDMX. Peptide 4 does not enter cells so it cannot bind to its intracellular target. Adding positively charged amino acids or cell‐penetrating peptides increases cell uptake, but often also lysis. [8] Using N‐terminal fluorescein‐labelled (FITC) derivatives to compare cell uptake by flow cytometry, we replaced Glu4 in 4 with cysteine (4 a), Aoc (2‐aminooctanoic acid, 4 b), Phe (4 c), 4‐CF3‐Phe (4 d), 4‐NO2‐Phe (4 e), pentafluoro‐Phe (4 f), Trp (4 g), Nal (naphthylalanine, 4 h) and homohomoPhe (4 i). Additionally, peptide 4 a was alkylated with a benzyl (4 j), 4‐Me‐benzyl (4 k), 4‐NO2‐benzyl (4 l), 4‐SF5‐benzyl (4 m) or perfluorobenzyl (4 n) group (Figure 4A). Homocysteine (Hcy) was S‐arylated with 1,4‐dinitrobenzene (4 o) or hexafluorobenzene (4 p). Seleno‐derivative 4 q was prepared from homo‐selenocysteine. Further ring substitution at the para‐position,[ 7 , 10 ] by treating 4 p with NaSMe in DMF, or C2H5SH or NHMe2 in 50 mM Tris in DMF, gave 4 r, 4 s or 4 t. These changes did not alter peptide helicity (circular dichroism analysis, Figure S2). Peptide partition coefficients for octanol/buffer pH 7.4 (logD7.4) (Figure 4B), taking account of N‐terminal hydrophobic fluorescein in all compounds, correlated well with peptide HPLC retention time (r=0.95, r 2 =0.90) and clogP of just the aryl sidechain in amino acid at position 4 (r=0.90, r 2 =0.81) (Figure S3). This supports an influence of the modified aryl sidechain component on the hydrophobicity of peptides 4 a–t.

To understand what drives membrane insertion, we used fluorescence polarization to measure binding of FITC‐labelled peptides to lipid bilayers by titrating into phospholipid large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs, 100 nm diameter), composed of neutral (zwitterionic) POPC (1‐palmitoyl‐2‐oleoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐ phosphocholine) alone (Figure 4C) or enriched with 20 % negatively charged POPS (1‐palmitoyl‐2‐oleoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phospho‐serine) (Figure 4D). Peptide binding to vesicles (Figure S4) was quantitated as the water‐lipid partition coefficient (K p, Figures 4C, D) and plotted against logD 7.4 of the peptide and clogP for the side chain only at position 4 (Figure S5). The data show some correlation between arene hydrophobicity at position 4 and peptide‐membrane association (clogP vs K p: POPC, r=0.74, r 2 =0.55; or POPC : POPS, r=0.55, r 2 =0.30), but also suggest that other factors are involved. Indeed, polarizability of the aryl sidechain at position 4, which is independent of hydrophobicity (Figure S6), also correlated with vesicle partitioning (polarization vs K p: POPC, r=0.72, r 2 =0.52; or POPC : POPS, r=0.78, r 2 =0.62, Figure S5).

S/Se‐arene sidechains promoted partitioning into both vesicles. Electron‐deficient 4 l, 4 o had intermediate POPC : POPS vesicle affinity despite lower hydrophobicity, supporting electrostatic contributions. Higher lipid affinity of 4 p, 4 q over 4 j relates to the location of S/Se adjacent to the ring, an effect amplified in dithioether compounds 4 r and 4 s with higher affinity for both vesicles.

Next, we measured uptake of the peptides into HeLa cancer cells (Figure 4E). Most arene modifications improved uptake by 10–30 fold compared to 4 (with negatively charged Glu4), but S/Se‐arylated derivatives (4 m, 4 o–t) showed the greatest cell uptake. These minor structural changes caused similar cell uptake compared to a reported CPP‐tagged 4 that was twice the size. [8] HeLa cell uptake correlated to an extent with logD 7.4 of the peptide and clogP of position 4 (both with r=0.77, r 2 =0.59) (Figure S5), but hydrophobicity was clearly not the only contributor to cell uptake. As with POPC LUV binding, there is a significant relationship between cell uptake and aryl sidechain polarizability (r=0.68, r 2 =0.47, Figure S5). The electron‐deficient nitro compound 4 o also entered these cells despite its arene having much lower hydrophobicity than in 4 n or 4 p. Internalization was greater for more polarized S‐aryl (4 p) and Se‐aryl (4 q) than C‐aryl (4 j, 4 k, 4 n) substitution. These findings are consistent with an electrostatic contribution to cell uptake, with stronger electropositive dipoles induced by sulfur and fluorine substituents (4 r, 4 s) or SF5 (4 m) enhancing interaction with anionic phospholipids, which are reportedly [11] more exposed on the outer surface of cancer cells than other cells, although that needs further literature support.

Using multiple linear regression analysis (Figures 5, S7, S8), we found that the combined effect of hydrophobicity (clogP) and polarizability of the aryl sidechain statistically accounted for 78 % of the cell uptake variance for peptides 4 b–t (r=0.88 and r 2 =0.78), which was a much stronger correlation than for each parameter alone (Figure S5). The same trend was observed for phospholipid affinity (Figure S7B, S8). These analyses strongly support important, but independent, contributions from arene polarizability and lipophilicity to cell uptake and membrane binding, and they indicate that these contributions are additive.

An aromatic amino acid was replaced in a cell penetrat‐ing cationic cyclic peptide 6 a, featuring four arginines and two aromatic amino acids (Figure 6), a close analogue of reported CPP9 [12] known at μM concentrations to deliver cargo into cells. Naphthylalanine in 6 a was replaced by homocysteine with thio‐ (6 b) or 1,4‐dithio‐ (6 c, 6 d) fluoroarene substituents to produce CPP analogues with greater cell permeability than 6 a (Figure 6).

Next, cysteines or homocysteines were inserted at positions 4 and 8 and cyclized via a substituted arene to a 12‐mer peptide analogue of pDI. Arenes corresponding to 3 a–d gave size‐matched stapled peptides 7 a–d (Figure 7A) (syntheses in Supporting Information), with benzyl 7 a, tetrafluorobenzyl 7 b, dithioaryl 7 c, or dithiotetrafluoroaryl 7 d linkers. We compared 7 a–d with aliphatic hydrocarbon (i, i+4)‐stapled [13] pDI variant 8 (Figure 7A) for α‐helicity (Figure 7B), hydrophobicity (logD 7.4, Figure 7C), phospho‐lipid vesicle binding (K p, Figure 7D), and HeLa cell uptake (Figure 7E). Peptides had similar volumes (1787–1821 Å3) or helicity (57–61 %, Figure 7B) in POPC vesicles, so changes in membrane binding or cell uptake were not due to structural/steric changes.

Dithiotetrafluoroaryl substitution (7 d, corresponding to 4 s) conferred the highest octanol solubility (logD7.4, Figure 7C). Interestingly, dithioaryl 7 c and dithiotetrafluoroaryl 7 d interacted more strongly with POPC vesicles, compared to 8 or other C‐aryl analogues (7 a, 7 b) even when tetrafluorinated as 7 b (Figure 7D). This agrees with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of 3 a–d associating with POPC lipid bilayers (Figure S9); 3 c and 3 d rapidly associating with lipid whereas 3 a and 3 b inserted more slowly. Given crosslink rigidification and restricted configuration of the aryl group, POPC binding was possibly affected by orientation of the arene dipole, which is in the opposite direction for 3 c and 3 d than 3 a and 3 b (Figure 3A) and can better align with membrane dipoles. MD simulations, used to analyze binding of 7 a–d to POPC bilayer models over 200 ns, revealed that 7 d more frequently interacted with POPC than other peptides (Figure S10), and repeatedly uses the aryl π‐face to contact POPC (Supporting Information movie). Instructively, 7 d with an aromatic macrocycle and 8 with an aliphatic linker have comparable hydrophobicity (logD 7.4, HPLC retention time), helicity (≈60 %, pH 7.4) and HDM2 affinity (Figure S11). However, 7 d associated more strongly with POPC vesicles (Figure 7D) and had nine‐fold higher uptake into HeLa cells (Figure 7E) than 8, consistent with δ+‐δ− contributions to π‐membrane interaction. [14] Of note, helix stabilization and HDM2 affinity were only observed for S‐arylated homocysteines, not cysteines, stapled with hexafluorobenzene, as also reported by Verhook et al. [15]

Entry of 7 d to HeLa cells was briefly probed using endocytosis inhibitors (Figure 7F). At 5 μM, 7 d translocated via an energy‐dependent process, low temperature (4 °C) inhibiting uptake by ≈80 %. EIPA was the only endocytosis inhibitor to reduce cell uptake of 7 d (Figure 7F), suggesting its cell uptake is driven by macropinocytosis, like some stapled peptides. [16]

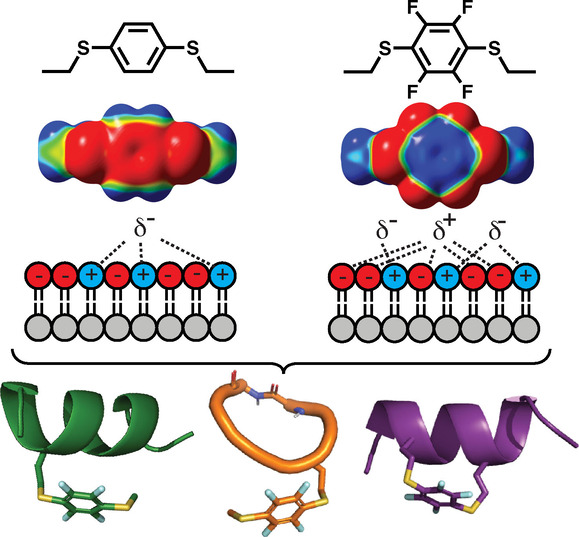

In conclusion, we show that sulfur and electronegative substituents polarize an aromatic ring to alter its electrostatic surface potential and hydrophobicity (Figures 1–3). When appended to helical peptides (Figure 4) or incorporated into cyclic peptides (Figures 6 and 7), they enhance membrane affinity and HeLa cell uptake, without altering peptide structure. Dithiophenyl and dithiotetrafluorophenyl substituents induce microdipoles (Figure 3) that promote binding to phospholipid membranes and internalization into HeLa cells (Figure 4C–E, Figure 6, Figure 7D–F). Tuning both dipole induction and hydrophobicity can increase membrane interactions (Figure 8) and drive membrane insertion. This is important for peptides acting on cell/microbe surfaces and for intracellular delivery, as association with membrane phospholipids or proteins initiates endocytosis. It is unclear whether changes to peptide sidechains promote escape from intracellular liposomes to the cytosol. Endosomal escape is triggered by lysis, pH change, or bursting on endosome maturation, [17] so tuning may alter affinity for endosomal membranes. Limiting polarization/hydrophobicity may minimise peptide retention on/in membranes, membrane disruption, cell lysis and water insolubility. Here, arene substitution showed a non‐lytic balance of these properties up to 5 μM in HeLa cells, while peptide 7 d was non‐toxic up to at least 50 μM (Figures S12, S13).

Figure 8.

Microdipoles in 3 c vs 3 d interact with negatively charged membranes (HeLa, POPC : POPS). Electron delocalisation from sulfur polarizes 3 c,d dispersing negative potential over the arene and sulfur atoms. Electron‐withdrawing fluorines in 3 d further polarize the arene by dispersing negative potential to the circumference, localising positive potential at the arene centre, and enhancing electrostatic interactions with negative charged membranes.

Electron‐deficient aromatic groups find many uses in chemistry, including promoting selective bioconjugation reactions in peptides [18] and improving metabolic stability of drugs, [19] while sulfur and fluorine substituents are common components of pharmaceuticals. [20] However, the electrostatic, polarizing, and dipole‐inducing properties of substituted arenes [21] remain to be fully and rationally exploited in design of membrane‐ and cell‐permeable peptides. An expanding repertoire of late‐stage peptide synthesis modifications[ 18 , 22 , 23 ] including S‐arylation[ 7 , 18 , 23 ] now enables selective incorporation of unnatural aromatic amino acids, finely tuned electronically as here, into peptides and proteins for enhanced cell uptake.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Sonia Henriques and Nicole Lawrence for assisting with vesicle assays, ARC (CE200100012, DP180103244, DP160104442) and NHMRC (SPRF1117017, 1128908, 1145372, 2009551) for funding. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

A. D. de Araujo, H. N. Hoang, J. Lim, J. Y. W. Mak, D. P. Fairlie, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202203995; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202203995.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Craik D. J., Fairlie D. P., Liras S., Price D., Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013, 81, 136–147; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Yang N. J., Hinner M. J., Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1266, 29–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Wimley W. C., White S. H., Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996, 3, 842–848; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Yau W.-M., Wimley W. C., Gawrisch K., White S. H., Biochemistry 1998, 37, 14713–14718; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. White S. H., Wimley W. C., Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 1999, 28, 319–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Sanderson J. M., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 201–212; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Ulmschneider M. B., Sansom M. S. P., Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2001, 1512, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Khemaissa S., Sagan S., Walrant A., Crystals 2021, 11, 1032; [Google Scholar]

- 4b. de Jesus A. J., Allen T. W., Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 864–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Mecozzi S., West A. P., Dougherty D. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 10566–10571; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Gaede H. C., Yau W.-M., Gawrisch K., J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 13014–13023; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Blaser G., Sanderson J. M., Wilson M. R., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 5119–5128; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Petersen F. N. R., Ø Jensen M., Nielsen C. H., Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 3985–3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Kalafatovic D., Giralt E., Molecules 2017, 22, 1929; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Som A., Reuter A., Tew G. N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 980–983; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 1004–1007; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Dom G., Shaw-Jackson C., Matis C., Bouffioux O., Picard J. J., Prochiantz A., Mingeot-Leclercq M.-P., Brasseur R., Rezsohazy R., Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spokoyny A. M., Zou Y., Ling J. J., Yu H., Lin Y.-S., Pentelute B. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 5946–5949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Philippe G., Huang Y. H., Cheneval O., Lawrence N., Zhang Z., Fairlie D. P., Craik D. J., de Araujo A. D., Henriques S. T., Biopolymers 2016, 106, 853–863; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Philippe G. J. B., Mittermeier A., Lawrence N., Huang Y.-H., Condon N. D., Loewer A., Craik D. J., Henriques S. T., ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 414–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hu B., Gilkes D. M., Chen J., Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8810–8817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qian E. A., Wixtrom A. I., Axtell J. C., Saebi A., Jung D., Rehak P., Han Y., Moully E. H., Mosallaei D., Chow S., Messina M. S., Wang J. Y., Royappa A. T., Rheingold A. L., Maynard H. D., Král P., Spokoyny A. M., Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen B., Le W., Wang Y., Li Z., Wang D., Ren L., Lin L., Cui S., Hu J. J., Hu Y., Yang P., Ewing R. C., Shi D., Cui Z., Theranostics 2016, 6, 1887–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Qian Z., Martyna A., Hard R. L., Wang J., Appiah-Kubi G., Coss C., Phelps M. A., Rossman J. S., Pei D., Biochemistry 2016, 55, 2601–2612; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Dougherty P. G., Sahni A., Pei D., Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10241–10287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schafmeister C. E., Po J., Verdine G. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 5891–5892. [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Giese M., Albrecht M., Rissanen K., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8867–8895; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Lucas X., Bauzá A., Frontera A., Quiñonero D., Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 1038–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Verhoork S. J. M., Jennings C. E., Rozatian N., Reeks J., Meng J., Corlett E. K., Bunglawala F., Noble M. E. M., Leach A. G., Coxon C. R., Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Yoo D. Y., Barros S. A., Brown G. C., Rabot C., Bar-Sagi D., Arora P. S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14461–14471; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Sakagami K., Masuda T., Kawano K., Futaki S., Mol. Pharmaceutics 2018, 15, 1332–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Pei D., Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 309–318; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Lönn P., Kacsinta A. D., Cui X.-S., Hamil A. S., Kaulich M., Gogoi K., Dowdy S. F., Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang C., Vinogradova E. V., Spokoyny A. M., Buchwald S. L., Pentelute B. L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4810–4839; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 4860–4892. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson B. M., Shu Y.-Z., Zhuo X., Meanwell N. A., J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 6315–6386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ilardi E. A., Vitaku E., Njardarson J. T., J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2832–2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Zhang C., Welborn M., Zhu T., Yang N. J., Santos M. S., Van Voorhis T., Pentelute B. L., Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 120–128; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Martinez C. R., Iverson B. L., Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2191–2201; [Google Scholar]

- 21c. Mondal S. I., Sen S., Hazra A., Patwari G. N., J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 3383–3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boutureira O., Bernardes G. J., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2174–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rojas A. J., Zhang C., Vinogradova E. V., Buchwald N. H., Reilly J., Pentelute B. L., Buchwald S. L., Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4257–4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.