Abstract

Objective

Little is known about the scope and role of discriminatory experiences in dentistry. The purpose of this study is to document the experiences that American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), Black, and Hispanic dentists have had with discrimination.

Methods

This study reports data from a 2012 nationally representative study of dentists documenting experiences with discrimination during their dental careers or during dental school by the setting of the discrimination, the providers' education, and geographic location. This study does not differentiate between levels of discrimination and focuses holisticly on the experience of any discrimination.

Results

Seventy‐two percent of surveyed dentists reported any experience with discrimination in a dental setting. The experiences varied by race/ethnicity, with 49% of AI/AN, 86% Black, and 59% of Hispanic dentists reporting any discriminatory experiences. Racial/ethnic discrimination was reported two times greater than any other type.

Conclusions

Experiences with racial/ethnic discrimination are prevalent among AI/AN, Black, and Hispanic dentists, suggesting that as a profession work is needed to end discrimination and foster belonging.

Keywords: African‐Americans, American Indians/Native Alaskan, dentists, Hispanic/Latino, oral health, racial discrimination, racism, survey research, workforce

BACKGROUND

Acts of discrimination, the overt, often systemic, prejudicial treatment of people and groups based on social characteristics such as race, gender, age, religion, or sexual orientation, are profoundly harmful, and the health workforce is not immune to their effects [1, 2]. Recurrent experiences of discrimination negatively affect mental and physical well‐being [3], and the impact is often compounding, contributing to burnout in the health workforce [4]. Individuals with several marginalized, intersectional identities are more likely to experience discrimination [5, 6, 7]. The recent Black Lives Matter movement has led to a greater understanding of the systemic influence of discrimination, most notably racism, in all aspects of life, including in the field of dentistry [8, 9]. Several recent papers clearly and concretely detail the inherently racist systems and policies in dentistry and call for diversifying the workforce as one of many critical components to addressing the issue [10, 11, 12].

To be sure, diversifying the workforce is an antiracist strategy for creating both inclusive professions, such as dentistry, but also an approach for uprooting discriminatory practices [13]. As a structural practice, strategic and intentional recruitment and retention efforts can help to support the institutional and professional changes needed to prevent discrimination. Further, it has been shown that URM dentists have high levels of racial/ethnic concordance with URM patients, and evidence from other fields indicates that concordance may impact health outcomes [14].

In the field of dentistry, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), Black, and Hispanic people have long been underrepresented minorities (URM), despite institutional and policy efforts to address the problem [15, 16]. Little is known about the scope and role of discriminatory experiences in dentistry, with only a few studies documenting discrimination at all [17, 18, 19], and no studies describing the impact of discrimination on practice patterns. This study examines self‐reported discriminatory experiences by setting, type, and frequency using a 2012 nationally representative sample survey of URM dentists in the U.S [20]. While the data reported in this study were collected in 2012, and have been widely reported on previously, [16, 20, 21, 22, 23] the fact that these data on discrimination are only being reported a decade later speak to the urgency of sharing these findings in light of the contemporary moment that the world is experiencing. If ever there was a time to acknowledge the problem of racism and to know the prevalence of experiences with racial/ethnic discrimination are among AI/AN, Black, and Hispanic dentists, the time is now.

METHODS

In 2012, a national sample survey of URM dentists in the United States was conducted by health workforce researchers in collaboration with the National Dental Association, the Hispanic Dental Association and the Society of American Indian Dentists. The survey was mailed with three follow ups, and an online option also was provided. It received a 34% adjusted response rate, and the full methodology has been detailed in a prior publication [20]. The University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

The sample for this study was limited to respondents who answered the following question: “During your career as a dentist or as a dental student, do you feel that you experienced discrimination based on any of the following characteristics?” Respondents could select all that apply (race, ethnicity, or color; gender; language skills; sexual orientation; disability status; and religion; write in other, or respond “I have never experienced discrimination.” The weighted study sample included 10,658 total respondents.

The outcome variables of interest were the setting of the experienced discrimination. Study participants were asked: “During your career as a dentist or as a dental student, have you experienced discrimination, been prevented from doing something, or been harassed or made to feel inferior in any of the following situations? In dental school, dental employment, the patient‐provider relationship, dealing with dental vendors in sales or in service, contracting with dental insurance networks, in the community where you practice, in seeking bank loans or credit for your practice, in interactions with medical/dental colleagues.” Respondents could respond: one time, two times, three times, four plus times, or never to each of the situations. To assess experiences with discrimination: responses of one, two, three or four plus times were included in the analysis as “any” discrimination. Additionally, a scale was constructed from 0 to 32 to rank the number of experiences with discrimination that study participants reported in a dental setting.

The following covariates were included in the analysis: type of dental school attended (categorized as private, public, historically Black college or university [HBCU], and outside of the United States); region (categorized as East North Central, East South Central, Middle Atlantic, Mountain, New England, Pacific, South Atlantic, West North Cental, and West South Central); and dental residency type (categorized as: I did not complete a dental residency; Advanced Education in General Dentistry (AEGD); General Practice Residency (GPR); a dental specialty (Pediatrics, Public Health, etc.), and level of concordance self‐reported with patients of the same race. Descriptive analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between geographic location and type of discrimination, between provider race and specific settings where it occurred, and finally among those who reported occurrence in dental training, the type of dental school setting. Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 14 [24].

RESULTS

The weighted study sample included 386 AI/AN, 5338 Black, and 4934 Hispanic dentists. From this sample, 72.4% of URM dentists reported any experience with discrimination. Specifically, 49.2% of AI/AN dentists, 86.4% of Black dentists, and 59.1% of Hispanic dentists reported experiences with discrimination. Overall, 62.9% of dentists reported experience with discrimination based on race and 26.9% reported discrimination by gender.

For AI/AN respondents, 50.8% reported never experiencing discrimination, 28.6% discrimination by gender, and 22.0% discrimination by race. For Black respondents, 81.4% reported discrimination by race, 31.8% discrimination by gender, and 13.6% reported never experiencing discrimination. For Hispanic respondents, 46.1% reported discrimination by race, 40.9% never experiencing discrimination, 21.5% discrimination by gender, and 15.6% discrimination by language.

Figures 1 and 2 show experiences with discrimination by their current location and by setting, respectively. The experiences with any discrimination by geographic variation. Individuals located in the east south central region of the country (Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama) reported the most racial/ethnic (78.7%) and gender (46.4%) discrimination experiences, while individuals located in the New England region reported the least racial/ethnic discrimination (49.2%) and individuals in the Mountain region reported the least gender discrimination (18.8%) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 1.

Type of reported discrimination experienced by underrepresented minority dentists' race and geographic location at the time of the survey (2012)

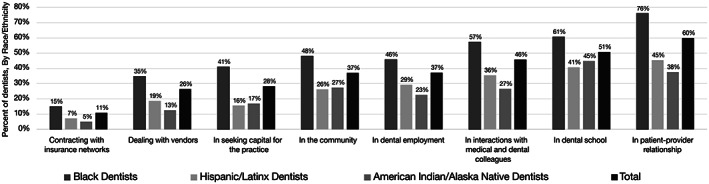

FIGURE 2.

Percent of underrepresented minority dentists reporting any discrimination experiences in dental settings (2012)

FIGURE 4.

Race and gender discrimination experienced by underrepresented minority dentists' race and geographic location at the time of the survey (2012) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Among all dentists who experienced discrimination, 60.0% of them reported any discrimination in patient‐provider relationships, 50.8% in dental school, and 46.9% in interactions with medical and dental colleagues. Black and Hispanic dentists followed the patterns for all dentists: 76.1% of Black dentists reported any discrimination in patient‐provider relationships, 60.8% in dental school, and 57.4% in interactions with medical and dental colleagues; 45.4% of Hispanic dentists reported any discrimination in patient‐provider relationships, 40.8% in dental school, and 35.5% in interactions with medical and dental colleagues. AI/AN dentists reported a different pattern: 44.9% reported any discrimination in dental school, 37.7% in patient‐provider relationships, and 26.6% in interactions with medical and dental colleagues. Conversely, experiences with no discrimination in settings were similar for the sample with 89.1% of all dentists reporting no experiences with discrimination in contracting with insurance companies, 73.9% in contracting with vendors, and 71.8% in seeking bank loans or credit for practice. This pattern was consistent for AI/AN, Black, and Hispanic dentist respondents.

There was no statistically significant relationship found between the concordance of providers' and their patient population's racial/ethnic makeup and any experience with discrimination in the patient‐provider relationship. Looking more closely at the top settings for any experiences with discrimination, additional analysis revealed differences by dental school type and the mean number of discrimination experiences (Figure 3). The mean number of experiences with discrimination range from 2.5 for those who attended a public dental school to 2.7 for those who attended a private dental school, 3.0 for those who attended historically Black college or university, and 3.5 for dentists who trained outside of the United States. With regard to interactions with medical and dental colleagues, the mean number of experiences was 2.5. Comparing the level of discriminatory experiences in interactions with medical and dental colleagues by respondents training, the data revealed similar proportions of respondents by training: 51% of respondents with only pre‐doctoral training, 51% of those with specialty training, and 53% of those with a General Practice Residency (GPR) or Advanced Education in General Dentistry Program (AEGD) reported any discrimination with colleagues. The mean number of experiences was higher by training: 2.9 for specialty training and 2.5 for no residency and GPR/AEGD only (See paper on Specialties by Poole et all for more in this issue).

FIGURE 3.

Among underrepresented minority dentists experiencing discrimination in dental school, reported mean frequency (2012) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DISCUSSION

URM dentists experiences with any discrimination varied by setting—with higher levels reported most in relational settings (patient–provider interactions, dental school, interactions with medical and dental colleagues) and least in business settings (contracting with insurance, dealing with vendors, and in seeking bank and loans for practice). These results speak to the degree to which discrimination and bias may show themselves more in interpersonal settings and may be less obvious in formal institutions. This may be in part because laws protect individuals against discrimination in accessing capital and in contracts. While these data suggest that experiences with any discrimination may be more interpersonal, discrimination experienced in systems and structures and expressed in formal practices and policies is a reality, known as systemic and structural racism [25]. Racism has had an impact both on the practice of dentistry and the experiences of dentists and the communities to whom they deliver care [26, 27].To be sure, while AI/AN, Black, and Hispanic dentists reported unacceptable levels of discriminatory experiences, the stark contrast of Black dentist's experiences in particular underscores the pressing need to address anti‐Black racism in all aspects of the dental career experience. Moreover, the experiences that Hispanic dentists reported around language discrimination are equally concerning. Such experience begs the question to what degree Hispanic dentists may be othered in the dental profession facing compounded discrimination because of language. Because Hispanic people account for 51% of the nation's population increase from 2010 to 2020 [28], it is worth considering the degree to which language discrimination reflects larger biases and systems of oppression related to xenophobia and white racial supremacy. From an antiracist lens, the experiences of Hispanic dentists may reflect experiences among populations, especially for immigrant and migrant populations and may suggest the need for health equity‐based solutions [29].

While the data from this survey did not reveal a significant relationship between the demographics of the provider's patient population and any experience with discrimination in patient‐provider relationships, this may have been limited by not knowing the entire history of employment, as we only knew the current practice setting, which may or may not be where the discriminatory incident happened. It is assumed that any discrimination reported at the level of provider's patient population would occur because of patient‐provide discordance. The literature from medicine suggests that patient‐provider racial/ethnic concordance impacts patient outcomes [14]. While studies have yet to be conducted it is worth considering how discriminatory experiences with patients impacts providers training, choice of specialty, and choice of practice setting. It is equally worth exploring from the patient‐provider relationship what impact discrimination in any form has on how providers are treated. There is anecdotal of provider experiences with patient–provider discordance; additionally, data may be needed to quantify and better describe these effects.

In the dental school setting, although the majority of respondents attended public dental schools, the number of incidents those individuals reported on average was the lowest (2.5) among training settings—it was foreign educated dentists that reported the highest average numbers of discriminatory events in the United States dental school setting. Most foreign educated dentists must attend further training in US schools either pre‐ or post‐graduate level to gain US licensure. From a workforce perspective, foreign educated dentists have the potential to add to the dentist workforce, which makes addressing experiences with discrimination an important issue [30].

The findings from this study are equally interesting with regard to AI/AN respondents who reported dental school as the setting for their experiences with discrimination and not interactions with patients or with medical or dental colleagues. This is striking because comparing first‐year dental students in 2013–2018, the percentage of AI/AN remained the same at 0.2% [31]. During these same periods of time, the percentage of Black and Hispanic first‐year dental students increased (for Black from 4.6% to 5.4% and for Hispanic from 8.1% to 10.1%). Because AI/AN comprised less than 1% of the first‐year dental students, the number are too small to be reported in reports about the dentist workforce where data re reported by race [32]. It can be presumed that AI/AN dentists are included in the category of “Other,” but this leaves the true burden of the problem—lack of entry into the dentist workforce a hidden problem. Concerted efforts are needed to address the findings reported here, if AI/AN dental students have the greatest share of their experiences with discrimination not in practice with patients or working with vendors, but in their training as dental students. Particularly as the share has not increased in the dentist workforce, and it may be these negative training experiences are being shared to dissuade applicants. Dental schools may want to include be intentional in their pathway programs for pre‐doctoral students, provide support and resources for students, and cultivate a culture of belonging among faculty, staff, and students [17, 33, 34, 35]. Partnership and collaboration with the Society of American Indian Dentists may also be support programmatic efforts to address these issues.

In addition to the impact on foreign educated dentists and AI/AN dentists, addressing discrimination and racism in dental education has critical implications for the Black, Hispanic, and AI/AN dentist workforce [21, 22, 23]. These dentists have larger shares of underrepresented minorities in their patient panels and serve as role models for individuals to join the dental workforce [16]. Dental education should be infused with anti‐racist practices from admissions through specialty training to ensure a safe environment for all students.

To address the experiences with discrimination respondents reported in interprofessional settings with medical and dental colleagues, medical and dental providers may need focused training on implicit bias [36]. The states of Maryland and Michigan, for example, have included implicit bias training as part of the continuing education requirement for health care providers license renewal. Other states may want to consider similar requirements and resources for provider continued learning. Based on these findings, for those states where dentists reported experiencing high levels of discrimination by race and gender (Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama), specific interventions may be needed (Figure 4).

As the first study to report the experiences that dentists who identify as AI/AN, Black, and Hispanic have faced with discrimination based on the color of their skin, country of origin, or accent, these results reflect experiences that members of these communities face in many fields [37], which suggests that solutions to ending discrimination and by extension racism, xenophobia, sexism, and all forms of oppression require comprehensive and robust strategies and interventions. At the systems‐level, ensuring that dental and medical providers are aware of their bias and are not contributing to professional intersections that lend themselves to discrimination is key. This system‐level approach requires individuals having the awareness of White privilege [38]. Within dental schools for predoctoral and postdoctoral training to not be a place where individuals experience discrimination, curricula can embrace antiracism pedagogy as well as knowledge building. Professional organizations can also make commitments to antiracist practices, whether that includes being intentional with leadership appointments and pathways to be both equitable and inclusive in who receives a seat at decision‐making tables. “Discrimination” does not appear in the ADA Principles of Ethics and Code of Conduct [39]. As part of professional practice, the anti‐discrimination and anti‐bias language could be explicitly stated to support both patient and population‐level care as well as how providers treat one another and other professionals.

LIMITATIONS

These data are primarily descriptive and subject to self‐report bias. However, the sheer magnitude of the types and locations of these experiences calls for more investigation, and more importantly action to remediate the unacceptable level of discriminatory events taking place in the dental education and practice setting. The estimates reported by region are at the Census “regions,” so these states fall into one census region. It may not necessarily mean that all four would have fallen into the same category, if they were analyzed separately. Future studies are needed to assess the experiences with discrimination that dentists encounter and to determine the degree to which these experiences impact their practices and perhaps are associated with weathering processes tied to worsen health outcomes and premature death. This study does not differentiate between levels of discrimination and focuses holisticly on the experience of any discrimination. Additional research is needed to explore how AI/AN, Black, and Hispanic dentists experience discrimination at different levels: intentional, explicit discrimination. Subtle, unconscious, automatic discrimination; statistical discrimination and profiling; and organizational processes [40]. Moreover, additional research is needed to understand the effect that discrimination has on dentists. This study was limited to the questions asked in the survey; future workforce survey designers may want to consider measuring the impact of discrimination on dentists and also exploring in qualitative studies, the narratives of experiences that would help support workforce development services or interventions to support AI/AN, Black, and Hispanic dentistry to thrive in the profession and not just survive.

CONCLUSIONS

This study expands on scientific knowledge about the dentist workforce adding insights on experiences with discrimination. Very high rates of both types and settings of discrimination are reported experienced by AI/AN, Black, and Hispanic dentists. Racial/ethnic discrimination was reported two times greater than any other type, with gender and language discrimination second and third most common. Because experiences with discrimination occurred in patient‐provider relationships, at dental schools, and in interactions with medical and dental colleagues in 2012 suggests a need to better understand these experiences in 2021, as well as ways that structural racism works in the field of dentistry. Moreover, because discrimination operates both between individuals and at the level of systems, institutions, and structures suggests that a multi‐pronged approach rooted in antiracism is needed. Policies and practices to address workforce diversity must address racism and discrimination in all its forms if we are to have a truly inclusive oral health system.

Fleming E, Mertz E, Jura M, Kottek A, Gates P. American Indian/Alaska Native, Black, and Hispanic dentists' experiences of discrimination. J Public Health Dent. 2022;82(Suppl. 1):46–52. 10.1111/jphd.12513

REFERENCES

- 1. Nunez‐Smith M, Pilgrim N, Wynia M, Desai MM, Jones BA, Bright C, et al. Race/ethnicity and workplace discrimination: results of a national survey of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaltiso SO, Seitz RM, Zdradzinski MJ, Moran TP, Heron S, Robertson J, et al. The impact of racism on emergency health care workers. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(9):974–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pascoe EA, Smart RL. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta‐analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng S‐JA. A review of “That's so gay! microaggressions and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community” Nadal, KL (2013). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 220 pp. ISBN: 978‐1‐4338‐1280‐4 (hardcover). Taylor & Francis; 2014.

- 6. Huynh VW. Ethnic microaggressions and the depressive and somatic symptoms of Latino and Asian American adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(7):831–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sue DW. Microaggressions and marginality: manifestation, dynamics, and impact. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ioannidou E, Feine JS. Black lives matter is about more than police behavior. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2020;5(4):288–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kadiyo T, Mellish V. Black lives matter: the impact and lessons for the UK dental profession. Br Dent J. 2021;230(3):134–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lala R, Baker SR, Muirhead VE. A critical analysis of underrepresentation of racialised minorities in the UK dental workforce. Community Dent Health. 2021;38(2):142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lala R, Gibson BJ, Jamieson LM. The relevance of power in dentistry. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2021;6(4):458–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jamieson L, Peres MA, Guarnizo‐Herreño CC, Bastos JL. Racism and oral health inequities. An overview. Clin Med. 2021;34:100827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine . Addressing diversity, equity, inclusion, and anti‐racism in 21st century STEMM organizations: proceedings of a workshop–in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician‐patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(35):21194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown RS, Schwartz JL. Minority dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(3):278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mertz EA, Wides CD, Kottek AM, Calvo JM, Gates PE. Underrepresented minority dentists: quantifying their numbers and characterizing the communities they serve. Health Affair. 2016;35(12):2190–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCann AL, Lacy ES, Miller BH. Underrepresented minority students' experiences at Baylor College of Dentistry: perceptions of cultural climate and reasons for choosing to attend. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(3):411–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Criddle TR, Gordon NC, Blakey G, Bell RB. African Americans in oral and maxillofacial surgery: factors affecting career choice, satisfaction, and practice patterns. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75(12):2489–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sandoval RS, Afolabi T, Said J, Dunleavy S, Chatterjee A, Ölveczky D. Building a tool kit for medical and dental students: addressing microaggressions and discrimination on the wards. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mertz E, Wides C, Cooke A, Gates P. Tracking workforce diversity in dentistry: importance, methods and challenges. J Public Health Dent. 2016;76(1):38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mertz E, Calvo J, Wides C, Gates P. The black dentist workforce in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77(2):136–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mertz E, Wides C, Calvo J, Gates P. The Hispanic and Latino dentist workforce in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77(2):163–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mertz E, Wides C, Gates P. The American Indian and Alaska native dentist workforce in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77(2):125–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. StataCorp . Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Braveman PA, Arkin E, Proctor D, Kauh T, Holm N. Systemic and structural racism: definitions, examples, health damages and approaches to dismantling. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(2):171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Evans CA, Smith PD. Effects of racism on oral health in the United States. Community Dent Health. 2021;38(2):138–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith PD, Wright W, Hill B. Structural racism and Oral health inequities of black vs. non‐Hispanic White adults in the U.S. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32(1):50–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones N, Marks R, Ramirez R, Rios‐Vargas M. Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country 2021; 2020. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html.

- 29. Machado S, Goldenberg S. Sharpening our public health lens: advancing im/migrant health equity during COVID‐19 and beyond. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Allukian M. Foreign educated dentists (FEDs)—an untapped National Resource. J Hispanic Dent Assoc. 2021;1(1):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31. American Dental Education Association . Snapshot of Dental Education, 2020‐21. Washington, DC: American Dental Education Association; 2021. Available from: https://www.adea.org/uploadedFiles/ADEA/Content_Conversion_Final/deansbriefing/2019-20_ADEA_Snapshot_of_Dental_Education.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32. American Dental Association Health Policy Institute . Racial and ethnic mix of dental students in the U.S. Washington, DC: American Dental Association; 2020. Available from: https://www.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/ada-org/files/resources/research/hpi/hpigraphic_0421_2.pdf?rev=9842f1f198184ba78d75d2254f695581&hash=24E0F760A7F18B3B04086AF309079103 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andersen RM, Carreon DC, Friedman JA, Baumeister SE, Afifi AA, Nakazono TT, et al. What enhances underrepresented minority recruitment to dental schools? J Dent Educ. 2007;71(8):994–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Camacho A, Zangaro G, White KM. Diversifying the health‐care workforce begins at the pipeline: a 5‐year synthesis of processes and outputs of the scholarships for disadvantaged students program. Eval Health Prof. 2017;40(2):127–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Pipeline programs to improve racial and ethnic diversity in the health professions: an inventory of federal programs, asssessment of evaluation approaches, and critical review of the research literature. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sabin J, Guenther G, Ornelas IJ, Patterson DG, Andrilla CHA, Morales L, et al. Brief online implicit bias education increases bias awareness among clinical teaching faculty. Med Educ Online. 2022;27(1):2025307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee H, Vaid U, Maxton A. Philanthropy always sounds like someone else: a portrait of high net worth donors of color. Redan, GA: Donors of Color Network; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 38. McIntosh P. White privilege: unpacking the invisible knapsack. Peace Freedom Mag. 1989;July/August:10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 39. American Dental Association . Principles of ethics and code of professional conduct. Chicago, IL: American Dental Association; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. National Research Council CoNS, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education . In: Blank RM, Citro CF, editors. Measuring racial discrimination. Panel on methods for assessing discrimination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]