Abstract

Objective

In Alzheimer disease (AD) animal models, synaptic dysfunction has recently been linked to a disorder of high‐frequency neuronal activity. In patients, a clear relation between AD and oscillatory activity remains elusive. Here, we attempt to shed light on this relation by using a novel approach combining transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroencephalography (TMS‐EEG) to probe oscillatory activity in specific hubs of the frontoparietal network in a sample of 60 mild‐to‐moderate AD patients.

Methods

Sixty mild‐to‐moderate AD patients and 21 age‐matched healthy volunteers (HVs) underwent 3 TMS‐EEG sessions to assess cortical oscillations over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the precuneus, and the left posterior parietal cortex. To investigate the relations between oscillatory activity, cortical plasticity, and cognitive decline, AD patients underwent a TMS‐based neurophysiological characterization and a cognitive evaluation at baseline. The latter was repeated after 24 weeks to monitor clinical evolution.

Results

AD patients showed a significant reduction of frontal gamma activity as compared to age‐matched HVs. In addition, AD patients with a more prominent decrease of frontal gamma activity showed a stronger impairment of long‐term potentiation–like plasticity and a more pronounced cognitive decline at subsequent follow‐up evaluation at 24 weeks.

Interpretation

Our data provide novel evidence that frontal lobe gamma activity is dampened in AD patients. The current results point to the TMS‐EEG approach as a promising technique to measure individual frontal gamma activity in patients with AD. This index could represent a useful biomarker to predict disease progression and to evaluate response to novel pharmacological therapies. ANN NEUROL 2022;92:464–475

In recent years, a growing body of evidence has supported the concept that loss of synaptic density could be an early event that precedes neuronal degeneration, suggesting that the impairment of synaptic mechanisms plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease (AD). 1 , 2 In animal models, AD‐related synaptic dysfunction has recently been linked to a disorder of high‐frequency neuronal activity. 3 , 4 Specifically, local changes in the activation of excitatory and fast‐spiking inhibitory neurons (FSNs) that resonate in the gamma frequency modulate the activity of multiple brain centers critical for learning and memory, such as the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. 3 , 4 Along the same lines, recent findings showed the key role of gamma activity in ruling synaptic plasticity. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 In animal models of AD, for instance, gamma oscillations decrease before the onset of plaque formation and the occurrence of cognitive decline, whereas the induction of fast‐spiking activity at 40Hz reduces the level of amyloid‐beta (Aβ) isoforms. 3 In addition, soluble Aβ oligomers have consistently been found to block long‐term hippocampal potentiation (LTP), an electrophysiological correlate of learning and memory, in vivo and in vitro. 9 In patients with AD, a similar impairment of LTP‐like cortical plasticity has been consistently observed. 10 , 11 Taken together, these findings suggest a strong link between brain gamma rhythms, synaptic plasticity dysfunction, and underlying AD pathology.

In humans, investigations on the relation between AD and gamma oscillations have reported contradictory results. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 One potential reason for this discrepancy is due to the limitations of standard electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings. Here, we use a novel approach optimally tuned to detect local oscillatory activity in specific areas, 16 provided by the combination of EEG recordings and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Thus far, only a few studies have used TMS‐EEG in AD, suggesting a potential link between altered cortical excitability and cognitive impairment. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 However, the potential of TMS‐EEG in clarifying the role of gamma oscillations has not been exploited.

Here, we hypothesized that combined TMS‐EEG would reveal altered local gamma oscillatory activity in AD patients by measuring TMS‐related spectral perturbation (TRSP) over 3 hubs of the frontoparietal network: the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (l‐DLPFC) the left posterior parietal cortex (l‐PPC), and the precuneus (PC). Hence, we tested the hypothesis that TRSP in the gamma range would be reduced in AD patients as compared to healthy subjects. Given the strong relationship between brain gamma rhythm activity and synaptic plasticity dysfunction in AD, 10 , 11 we also hypothesized that impairment of gamma activity would be associated with an LTP‐like cortical plasticity impairment, as measured with intermittent theta‐burst stimulation (LTP‐iTBS). Finally, for each area, we measured the most expressed frequency (ie, the natural frequency [NF]) with the hypothesis that evoked oscillatory activity could also predict subsequent cognitive decline, measured 24 weeks after from the initial neurophysiological evaluation.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

A total of 126 AD patients, admitted to the memory clinic of the Santa Lucia Foundation (Rome, Italy) between January 2014 and June 2020 for memory symptoms, were screened for the current study. Here, we included the first 60 AD patients who completed the initial evaluation and the clinical follow‐up after 24 weeks. The study was approved by the review board and ethics committee of the Santa Lucia Foundation and was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients or their relatives or legal representatives provided written informed consent. Patients could withdraw at any point without prejudice.

Patients were eligible if they had an established diagnosis of probable mild‐to‐moderate AD according to the International Working Group recommendations. 21 Inclusion criteria included: (1) AD patients aged >50 ≤ 85 years, (2) Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes (CDR‐SB) score of 0.5–1, (3) Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 18–26 at screening, (4) one caregiver, and (5) patient had been treated with acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for at least 6 months. Patients were excluded if they had extrapyramidal signs, history of stroke, other neurodegenerative disorders, or psychotic disorders or if they had been treated 6 months before enrollment with antipsychotic, antiparkinsonian, anticholinergic, or antiepileptic drugs. Signs of concomitant cerebrovascular disease on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were carefully investigated and excluded in all patients. Patients who agreed to participate underwent a clinical evaluation to evaluate the cognitive and functional state, and a TMS‐EEG evaluation to assess cortical oscillatory activity. TMS–electromyographic (EMG) evaluation to assess LTP‐like cortical plasticity was also performed in 38 patients. Cognitive evaluation was repeated after 24 weeks to evaluate disease progression. Twenty‐one age‐matched healthy volunteers (HVs) were recruited after informed consent and underwent the same TMS‐EEG evaluation.

Clinical Evaluation

Patients underwent the following cognitive and behavioral scales at enrollment and at 24 weeks follow‐up: CDR‐SB score, 22 Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS‐Cog), 23 Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS‐ADL), 24 and Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). 25

Cortical Oscillation Evaluation

Cortical oscillations were assessed by means of single‐pulse TMS during concomitant EEG recordings. During all the TMS‐EEG recordings, participants sat in a comfortable armchair in a soundproof room in front of a computer screen. They were instructed to fixate on a white cross (6 × 6cm) in the middle of the screen and to keep their arms rested in a relaxed position. In the cortical oscillations evaluation, participants wore in‐ear plugs that continuously played a white noise that reproduced the specific time‐varying frequencies of the TMS click, to mask the click and avoid possible auditory event‐related potential (ERP) responses. 26 The intensity of the white noise was adjusted for each individual by increasing the volume (always <90dB) until the participant was sure that s/he could no longer hear the TMS‐induced click. TMS for EEG recordings was carried out using a Magstim Rapid 2 magnetic stimulator, which produces a biphasic waveform with a pulse width of ∼0.1 milliseconds, connected to a figure‐of‐eight coil with a 70mm diameter (Magstim Company, Whitland, UK) that generates 2.2T as maximum output. The coil was differently oriented for the 3 areas of stimulation so that the direction of current flow in the most effective (second) phase was in a posterior–anterior direction. The 3 areas of stimulation were l‐DLPFC, PC, and l‐PPC. The order of stimulation of either area was counterbalanced across patients. Individual T1‐weighted MRI volumes were used as an anatomical reference. To target the l‐DLPFC, the coil was positioned over the junction of the middle and anterior thirds of the middle frontal gyrus, corresponding to an area between the center of Brodmann area (BA) 9 and the border of BA 9 and BA 46 junctions, with an orientation of 45° laterally; this positioning was based on previous studies using MRI‐based neuronavigated TMS and TMS‐EEG on this area. 20 To target the PC, the coil was positioned along the medial superior parietal cortex, with an orientation parallel to the midline; this positioning was based on previous studies conducted using MRI‐based neuronavigated TMS. 19 To target the l‐PPC, the coil was positioned over the angular gyrus, close to a posterior part of the adjoining caudal intraparietal sulcus, with an orientation of 15° from the midline. This positioning was based on previous investigations adopting MRI‐based neuronavigated TMS. 27 Stimulation intensity for the 3 areas was based on a distance‐adjusted motor threshold considering the individual coil‐to‐cortex distance (adjMT). 28 The intensity of stimulation of single‐pulse TMS was set at 90% of the adjMT. To ensure that this intensity was sufficient to evoke a reliable response in the AD patients (ie, >40V/m), 16 we computed the scalp‐to‐cortex distance (SCD) and the induced E‐field over the TMS targets with SimNIBS v3.2, an open‐source simulation package that integrates segmentation of MRI scans, mesh generation, and FEM E‐field computations. 29 For the HV group, we used Montreal Neurological Institute mapping of the standard brain provided in SimNIBS software as an anatomical reference. 30 To ensure a high degree of reproducibility across neurophysiological assessments, the coil position was constantly monitored using the Softaxic neuronavigation system. TMS was delivered in blocks of 120 single pulses with a randomized interstimulus interval between 2 and 4 seconds. EEG was recorded with a TMS‐compatible DC amplifier (BrainAmp; BrainProducts, Munich, Germany) from 29 TMS‐compatible Ag/AgCl pellet electrodes mounted on an elastic cap. Additional electrodes were used as a ground and reference. The ground electrode was positioned in AFz, whereas the reference electrode was positioned on the tip of the nose. EEG signals were digitized at a sampling rate of 5kHz. Skin/electrode impedance was maintained at <5kΩ. TMS‐EEG data were preprocessed offline with Brain Vision Analyzer (Brain Products) following the standard procedure reported in previous works. 26 , 31 , 32 After preprocessing, the signal was rereferenced to the average signal of all the electrodes. EEG analysis was performed with MATLAB (v2020, MathWorks, Natick, MA). Analysis consisted of the evaluation of TRSP for the theta, alpha, beta, and gamma bands. Significant TRSP values from baseline power were assessed using a bootstrap method. 33 Using this approach, we avoided any a priori assumption on TRSP data while correcting for multiple comparisons. A realistic sham condition was also performed to ensure that possible between‐group measures in TMS‐EEG signals evoked from the l‐DLPFC were not driven by the processing of auditory and somatosensory input. The procedure was a modified version of a protocol used previously 26 and involved simultaneous auditory and somatosensory stimulation.

LTP‐Like Cortical Plasticity

In the cortical plasticity evaluation, AD patients received 20 TMS single pulses over the left M1 to record 1mV motor‐evoked potentials (MEPs) before and after 10 minutes of the iTBS protocol. 34 Single‐pulse TMS for EMG recordings was carried out using a Magstim 200 magnetic monophasic stimulator connected to the same coil as TMS‐EEG recordings. iTBS was carried out using a Magstim Rapid 2 magnetic biphasic stimulator. For M1 stimulation, the coil was placed tangentially to the scalp at an approximately 45° angle away from the midline, thus inducing a posterior–anterior current in the brain. The intensity of stimulation was adjusted to evoke an MEP of ~1mV peak‐to‐peak amplitude. To ensure the same coil positioning was applied throughout the intervention, we used a neuronavigation system, as in the TMS‐EEG recording session. EMG was recorded from the first dorsal interosseous muscle contralateral to the stimulation using 9mm‐diameter Ag/AgCl surface cup electrodes. The active electrode was placed over the belly muscle, whereas the reference electrode was located over the metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger. Responses were amplified using a Digitimer D360 amplifier through filters set at 5Hz and 2kHz, with a sampling rate of 5kHz, and then recorded by a computer using SIGNAL (Cambridge Electronic Devices, Cambridge, MA). EMG analysis was performed with SIGNAL. To evaluate cortical plasticity, we measured for each individual the percentage ratio in the peak‐to‐peak amplitude between post‐iTBS MEPs and pre‐iTBS MEPs.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS v22 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Prior to undergoing parametric or nonparametric statistical procedures, assumption of normality distribution of data residuals was assessed with Shapiro–Wilk test; assumption of homoscedasticity was assessed with Levene test. For regression analyses, assumption of multicollinearity among predictors was assessed by utilizing the variance inflation factor. Assumption of independence of residuals was assessed with Durbin–Watson test. Level of significance was set at α = 0.05. All the tests were 2‐tailed.

A first set of analyses was aimed at comparing TRSP between the 2 groups (AD patients vs HVs) both at the global level (ie, comparing TRSP over all the scalp) and at the local level (ie, comparing TRSP over the site of stimulation). Global analysis was performed with a nonparametric, cluster‐based permutation method comparing the 2 groups at each electrode and at each frequency band (theta, alpha, beta, gamma). 33 To reduce the occurrence of type I errors, this method calculates Monte Carlo estimates of the significance probabilities from 2 surrogate distributions constructed by randomly permuting the data for the 2 original conditions 3,000 times. The clusters for permutation analysis were defined as the 2 (or more) neighboring electrodes for which the statistical value at a given time point exceeded the significance threshold. 33 Local analysis was performed with multiple independent t tests comparing the TRSP values at each frequency (from 4 to 50Hz) recorded at the closest electrode to the stimulation (F3 for l‐DLPFC, Pz for PC, P3 for l‐PPC) in the 2 groups (AD and HVs). To avoid the occurrence of type I errors, this analysis was performed by permuting the original distributions 3,000 times and correcting the t values with the false discovery rate method. Both the global analysis and the local analysis were conducted in a large time window ranging from 1 to 1 seconds after TMS. This analysis allowed us to monitor possible differences even in a “resting” part of the EEG, that is, before the TMS pulse and after the TMS perturbation. The frequency layer with the highest TRSP values was taken as the NF of each stimulated area. To assess whether there was any difference in the TMS‐evoked activity after sham stimulation between the 2 groups (AD patients vs HVs), we compared the global mean field power (GMFP) waveform, because this measure takes into account the TMS‐evoked EEG response recorder over all the electrodes. This is important because possible auditory or somatosensory responses are usually centered over a wide cluster of bilateral central electrodes. 26

A second set of analyses was aimed at testing the sensibility of TRSP in predicting the probability of being classified as an AD patient or an HV for each case. This analysis was conducted using a logistic regression model with the group as dependent variable and TRSP in the theta, alpha, beta, and gamma ranges as predictor variables. This analysis was first performed using the entire sample of AD (n = 60) against the HVs (n = 21). To avoid any possible bias due to the unbalanced size of the groups, we repeated the analysis using 10 random samples of 40 AD patients and 10 random samples of 20 AD patients against the 21 HVs. Selection of the significant predictor was performed using a stepwise backward algorithm.

A third set of analyses was aimed at testing the predictive value of gamma TRSP and the NF of the DLPFC (l‐DLPFC‐NF) in the cognitive/behavioral progression of the patients. This analysis was conducted using a multivariate general linear model with dependent variables the change in CDR‐SB, ADCS‐ADL, NPI, ADAS‐Cog, and Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) scores 24 weeks after the baseline evaluation, and with l‐DLPFC‐NF or the gamma TRSP as predictor. Finally, to test whether gamma TRSP and l‐DLPFC‐NF were linearly related to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers and to cortical plasticity, we used the Pearson or the Spearman coefficient to correlate gamma TRSP and l‐DLPFC‐NF with the MEP changes following LTP‐like plasticity induced by the iTBS protocol.

Results

A total of 60 patients completed the clinical follow‐up at 24 weeks. The baseline AD patients' and HVs' characteristics are shown in the Table 1. The mean age of the total sample of AD patients was 74.11 years (standard deviation [SD] = 6.13, ranging from 60 to 88), of whom 63% were female (n = 38), whereas the mean age of the HV group was 71.21 years (SD = 6.32, ranging from 60 to 82). No differences in sex, age, or education years were found (all ps > 0.05). Mean MMSE raw score at baseline was 22.1 (SD = 3.11) for the AD patients and 28.81 (SD = 1.86) for the HVs. The mean resting motor threshold (RMT; % maximal stimulator output) was 51.52 (SD = 8.82) in the AD group and 58.25 (SD = 5.70) in the HV group. As expected, both MMSE and RMT values were lower in the AD patients compared to the HV group (both ps < 0.05). A total of 31 patients screened positive as carriers for at least 1 APOE ε4 allele; these patients did not differ from the rest of the group in any of the neurophysiological measures we tested (all ps > 0.05). The entire procedure was well tolerated, with no reports of adverse effects.

Table 1.

AD Patient and HV Demographics and Clinical Characteristics at Baseline

| AD Patients, n = 60 | HV, n = 21 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 74.11 (6.12) | 71.19 (6.31) | p > 0.05 |

| Sex, females, n (%) | 38 (63%) | 12 (57%) | p > 0.05 |

| Education, years, mean (SD) | 8.52 (4.11) | 10.04 (4.98) | p > 0.05 |

| RMT, % stimulator output, mean (SD) | 51.52 (8.82) | 58.25 (5.70) | p < 0.05 |

| Proportion of patients taking cholinesterase inhibitors, n (%) | 46 (76%) | ||

| Proportion of patients taking memantine, n (%) | 12 (20%) | ||

| APOE e4 carrier, n (%) | 31 (52%) | – | ‐ |

| MMSE raw score, mean (SD) | 22.10 (3.11) | 28.81 (1.86) | p < 0.05 |

| CDR‐SB raw score, mean (SD) | 3.99 (1.64) | – | – |

| ADAS‐Cog raw score, mean (SD) | 21.95 (6.91) | – | – |

| ADCS‐ADL score, mean (SD) | 60.85 (10.85) | – | – |

| NPI score, mean (SD) | 11.98 (11.22) | – | – |

| FAB raw score, mean (SD) | 11.42 (3.29) | – | – |

AD = Alzheimer disease; ADAS‐Cog = Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale; ADCS‐ADL = Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living; CDR‐SB = Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes; FAB = Frontal Assessment Battery; HV = healthy volunteer; MMSE = Mini‐Mental State Examination; NPI = Neuropsychiatric Inventory; RMT = resting motor threshold; SD = standard deviation.

Cortical Activity in AD Patients and HVs

A first analysis was conducted to ensure that the 3 TMS targets received the same stimulation in terms of efficacy and intensity. Thus, we first computed the SCD for the 3 areas obtaining the following results: 18.93 ± 2.1mm for the l‐DLPFC, 25.4 ± 1.9mm for the PC, and 21.1 ± 4.5mm for the l‐PPC. We then computed the difference between the SCD in the AD group and the standard SCD values used for the HV group in the 3 areas (l‐DLPFC SCD difference, 5.41 ± 2.17mm; PC SCD difference, 5.45 ± 1.98mm; l‐PPC SCD difference, 5.86 ± 3.44mm) without observing any difference among the 3 SCDs (l‐DLPFC vs PC, p = 0.93; l‐DLPFC vs l‐PPC, p = 0.61; PC vs l‐PPC, p = 0.67). All of our participants received a stimulation of at least 45V/m (mean = 60 ± 8.22V/m) with no differences in the e‐field induced in the 3 TMS spots (all ps > 0.05) and no differences compared to the e‐fields estimated for the HV group using the standard brain (all ps > 0.05).

Then we assessed the timing of the significant TRSP and we tested for possible difference in the “resting” EEG activity, that is, before and after the TRSP. Figures 1, 2, and 3 show the spatiotemporal reconstruction of TRSP recorded over all the scalp after stimulation of the l‐DLPFC, PC, and l‐PPC, respectively. Regardless of the site of stimulation, single‐pulse TMS resulted in a sustained oscillatory activity ranging from 4 to 48Hz lasting about 170 milliseconds for the beta and gamma bands (ps < 0.05) and about 250 milliseconds for the alpha and theta bands (p < 0.05).

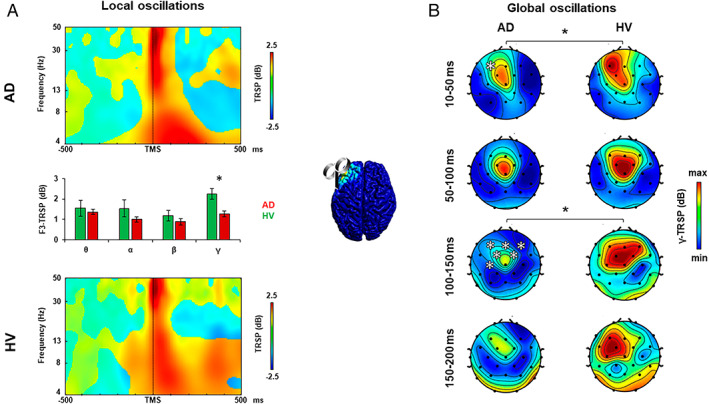

FIGURE 1.

Oscillatory activity analysis after left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). (A) TMS‐related spectral perturbation (TRSP) recorded over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (l‐DLPFC) in the Alzheimer disease (AD) group (upper plot, red bars) and in the healthy volunteer (HV) group (lower plot, green bars). (B) TRSP with scalp maps of gamma activity recorded over all the scalp after stimulation of the l‐DLPFC in the AD group (left maps) and in the HV group (right maps). Error bars indicate standard error. *p < 0.05. [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

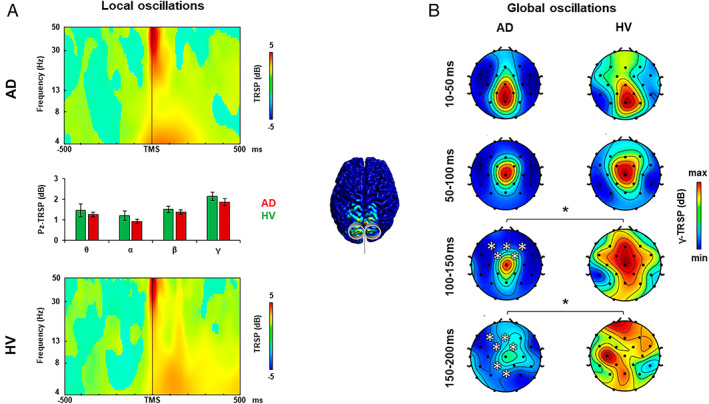

FIGURE 2.

Oscillatory activity analysis after precuneus transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). (A) TMS‐related spectral perturbation (TRSP) recorded over the precuneus (PC) in the Alzheimer disease (AD) group (upper plot, red bars) and in the healthy volunteer (HV) group (lower plot, green bars). (B) TRSP with scalp maps of gamma activity recorded over all the scalp after stimulation of the PC in the AD group (left maps) and in the HV group (right maps). Error bars indicate standard error. *p < 0.05. [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

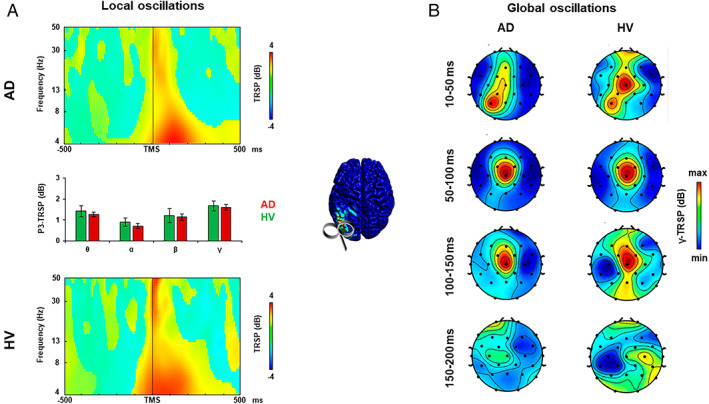

FIGURE 3.

Oscillatory activity analysis after left posterior parietal cortex transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). (A) TMS‐related spectral perturbation (TRSP) recorded over the left posterior parietal cortex (l‐PPC) in the Alzheimer disease (AD) group (upper plot, red bars) and in the healthy volunteer (HV) group (lower plot, green bars). (B) TRSP with scalp maps of gamma activity recorded over all the scalp after stimulation of the l‐PPC in the AD group (left maps) and in the HV group (right maps). Error bars indicate standard error. [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

Analysis of TRSP at the local level was conducted to assess the local oscillatory activity of the stimulated area (see Figs 1A, 2A, and 3A) and to measure the most expressed frequency. When stimulated over the l‐DLPFC (see Fig 1A), AD patients showed a lower local gamma activity compared to the HV group from 10 to 83 milliseconds and from 137 to 170 milliseconds after TMS (mean activity ± standard error: AD, 1.283 ± 0.143dB; HVs, 2.243 ± 0.267dB; t 79 = −2.977, p = 0.004), whereas the other frequency bands did not differ between the 2 groups (all ps > 0.05). When stimulated over the PC (see Fig 2A) and the l‐PPC (see Fig 3A), AD patients did not show any difference in the local oscillatory activity compared to the HV group (all ps > 0.05).

Analysis of TRSP at the global level was conducted to assess differences in cortical oscillatory activity throughout all the scalp between the AD and the HV groups. When stimulated over the l‐DLPFC (see Fig 1B), AD patients showed lower gamma‐frequency (30–50Hz) activity evoked from 10 to 50 milliseconds after TMS in the F3 electrode and from 100 to 150 milliseconds in a cluster of 6 frontal bilateral electrodes, namely, Fz, F3, F4, FC1, FC2, and C3 (Monte Carlo ps < 0.01). When stimulated over the PC (see Fig 2B), AD patients showed lower gamma‐frequency (30–50Hz) activity evoked from 100 to 150 milliseconds after the TMS pulse in a cluster of 5 frontal bilateral electrodes (Monte Carlo ps < 0.01), and from 150 to 200 milliseconds after the TMS pulse in 2 clusters of 4 frontal electrodes and 2 posterior medial electrodes (Monte Carlo ps < 0.01). Stimulation of l‐PPC (see Fig 3B) did not produce any difference in the oscillatory activity of the 2 groups (all ps > 0.05).

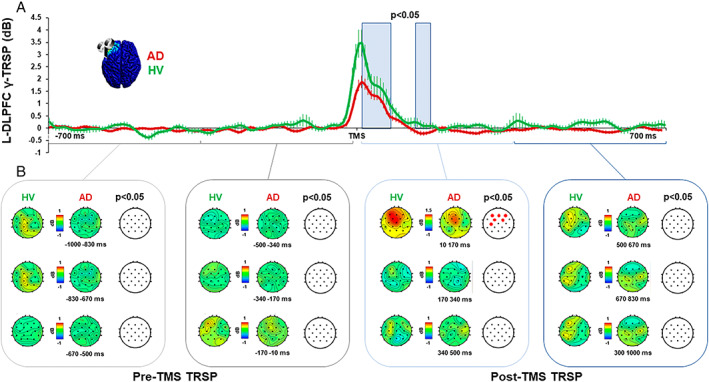

Importantly, we did not observe any difference in the resting EEG activity. This was measured either before the TMS pulse was applied (ie, −1,000 milliseconds to −10 milliseconds from the TMS pulse) or after the TRSP time window (ie, 250 milliseconds after the TMS pulse) in the stimulated areas (all ps > 0.05; Fig 4). No differences were observable in the grand‐averaged GMFP of the 2 groups after sham stimulation (all ps > 0.05).

FIGURE 4.

Gamma oscillatory activity before and after transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (l‐DLPFC). (A) Local gamma activity recorded over the l‐DLPFC in the Alzheimer disease (AD) group (red line) and in the healthy volunteer (HV) group (green line). Blue light squares indicate the time windows in which there is a significant difference between the 2 groups (p < 0.05). (B) Global gamma activity with scalp maps after stimulation of the l‐DLPFC in the AD group (left maps) and in the HV group (right maps). Red dots indicate significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.05). TRSP = TMS‐related spectral perturbation. [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

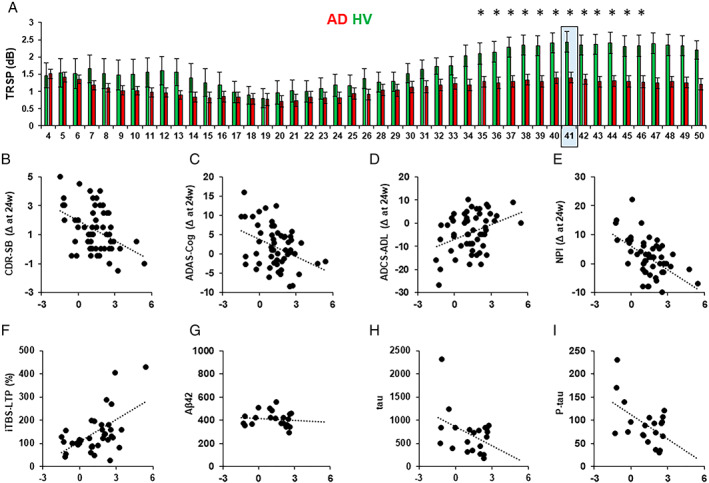

Figure 5A shows the TRSP mean value for each of the 46 frequency layers analyzed after stimulation of the l‐DLPFC. Stimulation of l‐DLPFC resulted in an l‐DLPFC‐NF of 40.8Hz for both groups. When compared with HVs, the AD group showed a lower TRSP in the range of frequency from 35 to 46Hz, with an NF of 40.8Hz (mean p = 0.006).

FIGURE 5.

Natural frequency analysis. (A) TMS‐related spectral perturbation (TRSP) for each frequency layer after stimulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (l‐DLPFC). Red bars depict the TRSP in the Alzheimer disease (AD) group; green bars depict the TRSP in the healthy volunteer (HV) group. Light blue squares indicate the natural frequency. Error bars indicate standard error. *p < 0.05. (B–E) Linear relations between the natural frequency of the l‐DLPFC (l‐DLPFC‐NF) and the clinical scores change after 24 weeks from the first evaluation in the (B) Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes (CDR‐SB; score range: 0–18, higher scores indicate worsening; r = −0.42, p = 0.001), (C) The Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS‐Cog; score range: 0–70, higher scores indicate worsening; r = −0.389, p = 0.003), (D) Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS‐ADL; score range: 0–78, lower scores indicate worsening; r = −0.365, p = 0.006), (E) Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI; score range: 0–144, higher scores indicate worsening; r = −0.414, p = 0.002). (F–I) Linear relations between the natural frequency of the l‐DLPFC and levels of (F) percentage of long‐term potentiation–like plasticity measured with intermittent theta‐burst stimulation (iTBS‐LTP; r = 0.447, p = 0.005), (G) amyloid‐beta (Aβ; r = −0.239, p = 0.148), (H) tau (r = −0.378, p = 0.04), and (I) p‐tau (r = −0.39, p = 0.04). [Color figure can be viewed at www.annalsofneurology.org]

Stimulation of PC and l‐PPC resulted in an NF of respectively 29.8 and 25Hz, with no difference in any of the layers considered as compared to HVs (all ps > 0.05).

Clinical Predictive Value of Cortical Oscillations

Multiple logistic regression analysis using all the 60 AD patients and 21 HVs showed that the model was able to significantly predict the probability of being classified as AD patient or HV when all 4 predictors were included, namely, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma TRSP (Model 1: −2LL = 81.568, p = 0.025 [LL is defined as Log‐likelihood]). Backward selection of coefficients revealed that gamma TRSP was the only significant predictor of the group classification (Model 4: −2LL = 84.368 p = 0.004, exp[B] = 0.555). When we repeated the analysis with 20 random samples of 40 and 20 AD patients versus 21 HVs, the results confirmed the previous observation, with the gamma TRSP as the only significant predictor of the group classification (mean for 10 models with 40 patients: −2LL = 65.273 ± 2.62, p = 0.003 ± 0.005, exp[B] = 0.453 ± 0.111; mean for 10 models with 20 patients: ‐2LL = 46.863 ± 1.77, p = 0.005 ± 0.003, exp[B] = 0.422 ± 0.043).

Multivariate linear regression analysis showed that l‐DLPFC‐NF and gamma TRSP both predicted the clinical progression of AD patients (l‐DLPFC‐NF: Λ = 0.674, F 5,48 = 4.636, p = 0.002, ε2 = 0.326; gamma TRSP: Λ = 0.754, F 5,48 = 3.138, p = 0.016, ε2 = 0.246). Regression coefficient analysis showed that l‐DLPFC‐NF and gamma TRSP were significant predictors for the CDR‐SB (l‐DLPFC‐NF: β = −0.460, t = −3.342, p = 0.002; see Fig 4; gamma TRSP: β = −0.384, t = −2.477, p = 0.017), the ADAS‐Cog (l‐DLPFC‐NF: β = −1.491, t = −3.070, p = 0.003; gamma TRSP: β = −1.609, t = −3.067, p = 0.003), the ADCS‐ADL (l‐DLPFC‐NF: β = 2.276, t = 3.097, p = 0.003; gamma TRSP: β = 1.912, t = 2.325, p = 0.024), and the NPI (l‐DLPFC‐NF: β = −2.737, t = −3.283, p = 0.002; gamma TRSP: β = −2.479, t = −2.670, p = 0.010), whereas l‐DLPFC‐NF was a significant predictor of the FAB change (β = 0.503, t = 2.037, p = 0.047) but not gamma TRSP (β = 0.440, t = 1.627, p = 0.110).

Linear Relationships between Gamma Activity, LTP‐Like Plasticity, and CSF Biomarkers

LTP‐like plasticity was tested in 38 AD patients. The mean percentage of MEP change after iTBS was 117.9 ± 49.03. Linear relation analysis between l‐DLPFC‐NF and iTBS‐LTP showed that the 2 measures were directly correlated (r = 0.412, p = 0.01; see Fig 4); this correlation was significant also when considering gamma TRSP and iTBS‐LTP (r = 0.416, p = 0.009). CSF tau, p‐tau, and Aβ42 levels were available in 21 AD patients. Linear relationship analysis between the l‐DLPFC‐NF and the CSF biomarkers (ie, tau, p‐tau, and Aβ42) showed a significant inverse relation with tau (r = −0.409, p = 0.033) and p‐tau levels (r = −0.521, p = 0.008) but not with Aβ42 (r = −0.239, p = 0.148). The same result was obtained when we considered the relation between gamma TRSP and tau (r = −0.422, p = 0.028), p‐tau (r = −0.540, p = 0.006), and Aβ42 (r = −0.365, p = 0.052).

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that AD patients show remarkable reduction of frontal gamma oscillatory activity as compared to age‐matched HVs. This finding was evident by stimulating different hubs of the frontoparietal network and directly recording evoked cortical oscillations in a large sample of mild‐to‐moderate AD patients. Notably, the reduction in frontal gamma activity was evident both when directly assessed by stimulating the l‐DLPFC, when assessed indirectly by stimulating the PC. These results are site‐specific, as there was no difference between the 2 groups when stimulation was administered to the l‐PPC. We also found that l‐DLPFC gamma activity and the predominant TMS‐evoked frequency (l‐DLPFC‐NF) were reliable predictors of subsequent cognitive decline. Specifically, patients with a more prominent decrease of gamma TRSP and l‐DLPFC‐NF are the ones who show a stronger cognitive decline at a subsequent follow‐up evaluation after 24 weeks. In addition, we observed a specific linear relationship between TMS‐evoked gamma activity and other AD‐related physiological measures. Specifically, patients with higher power of frontal gamma activity are better responders to iTBS‐induced LTP‐like cortical plasticity and show lower tau and p‐tau levels, supporting the specificity of gamma activity as an additional biomarker of AD pathology.

Gamma oscillations have been related to many high‐level cognitive functions, such as learning and formation of memory. 35 Additionally, the role of gamma activity in synaptic plasticity has been confirmed throughout the past 2 decades by numerous investigations using electrophysiological recordings. 36 Although the exact physiological mechanism is still a matter of debate, it has been suggested that local FSNs play a role in synchronizing gamma oscillations among large neuronal populations. 37 When depolarized, local FSN populations tend to generate synchronized inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in thousands of cells, inducing gamma oscillation entrainment to both local and distant neurons. This is relevant because gamma‐frequency synchronization between the activity of distant neuronal cells has emerged as a marker of connectivity within large cortical networks during learning or memory processing. 38

In the context of AD, the causal role of gamma oscillations in cellular pathology has largely been demonstrated. Recent findings revealed a reduction in gamma oscillations before the onset of plaque formation and cognitive decline in animal models of AD. Along the same lines, the induction of fast‐spiking activity at 40Hz reduces the level of Aβ isoforms, 3 whereas the disruption of gamma activity has been related to tau accumulation in astrocytes. 39 Furthermore, the presence of Aβ42 can induce a biphasic effect on network connectivity consisting of an initial decrease of gamma oscillations followed by overexcitation. 40 A similar scenario is found for acute Aβ effects in studies on plasticity reporting that it dramatically disturbs LTP and long‐term depression plasticity mechanism, 9 , 41 whereas other studies report that low physiologically relevant concentrations of Aβ promote LTP and memory. 42 At the same time, some forms of cortical LTP‐like cortical plasticity are altered in AD patients, whose dysfunction has been proposed as a central mechanism of AD pathology independently from the age of disease onset. 10 , 11 , 43

In AD patients, such evidence has not been clearly provided so far. Whereas some EEG studies showed a decrease in gamma activity at rest, 12 , 13 other studies described contradictory results. 14 , 15 More recently, this discrepancy has been observed in a large sample of AD patients reporting an inverted U‐shape relationship between amyloid depositions and gamma power. 44 The main advantage of our TMS‐EEG approach is that we could directly “perturb” a specific area with TMS, thus boosting its ongoing frequency of oscillation. 16 This could explain why the differences in oscillatory activity between the AD and HV groups were observable only within the specific TRSP time window and not during the resting EEG activity. Another main advantage of the TMS‐EEG approach is the possibility to reconstruct the gamma activity dynamic in the spatial and temporal domain. Specifically, when stimulating the l‐DLPFC, we observed an early local difference in gamma activity that subsequently spread bilaterally to the entire frontal lobe. Differently, when stimulating the PC, differences were observable in a late time window in the frontal bilateral electrodes (100–150 milliseconds) and the posterior–frontal medial electrodes (150–200 milliseconds), but not in the early local activity. These results indicate that gamma activity is prominently reduced in the frontal lobe of AD patients and is evident both when directly stimulated and when it is indirectly activated through PC stimulation, presumably reflecting default mode network connections. 19 In addition, we found that patients with lower power of gamma activity have an impaired response to the iTBS protocol testing LTP‐like cortical plasticity and a higher level of tau and p‐tau. We argue that the specific decrease of gamma oscillatory activity may relate to the detrimental effects induced by tau pathology, which have been shown to exert a harmful effect on both high‐frequency oscillatory activity 39 , 45 and cortical plasticity. 9 , 46

As a second aim of the study, we evaluated the potential clinical impact of the TMS‐EEG measurements in differentiating AD patients from HVs and in predicting subsequent cognitive decline. First, we found that the decrease of gamma activity in AD patients was the only significant predictor able to accurately distinguish AD patients from HVs. This result was robust and confirmed by replication analyses. In addition, we showed that individual level of the frontal natural gamma activity is able to predict the change occurring after 24 weeks in tests used to assess the cognitive/behavioral/functional impairment in randomized clinical trials such as the ADAS‐COG, the CDR‐SB, the ADCS‐ADL, and the NPI.

Although several AD biomarkers are widely applied and considered useful for diagnosis, sufficient accuracy is still lacking to evaluate disease severity and predict disease progression. For instance, the use of a single biomarker does not provide sufficient information to capture the underlying severity of disease across its entire spectrum, from preclinical to clinical stages of AD. This includes evaluating the response to the therapy with CSF and neuroimaging parameters such as hippocampal atrophy/whole brain volume. 47 Moreover, AD biomarkers evaluation is routinely assessed by means of invasive and/or high‐cost procedures, limiting their use in clinical practice. Thus, several efforts are underway to combine multiple biomarkers to predict the severity of AD, with an emphasis on temporally tracking the evolution of distinct biomarkers throughout the disease course. 48 Few imaging biomarkers have been developed to specifically evaluate synaptic dysfunction. One emerging method to detect synaptic loss in neurodegenerative dementias is based on positron emission tomography tracers targeting synaptic vesicle protein 2A, which is expressed ubiquitously in synapses. 49 However, this approach still needs to be further evaluated by future studies. In this context, our data point to TMS‐EEG as a novel approach to measure synaptic dysfunction based on frontal gamma activity in patients with AD. Our data show a strong relationship between individual frontal gamma activity, LTP‐like plasticity, and subsequent cognitive and functional decline. Hence, if confirmed in independent cohorts, this index could represent a useful biomarker to predict disease progression. Moreover, frontal oscillatory activity measured by TMS‐EEG has also been found to be a sensible biomarker to predict patient response to treatment, in the context of both pharmacological and nonpharmacological randomized controlled trials. 19 , 20 Notably, this approach has the clear advantage of being a low‐cost noninvasive procedure that can be performed several times to monitor the effects of a certain therapy.

Despite our results pointing to TMS‐EEG as a powerful method to measure oscillatory activity in AD patients, some technical issues still need to be addressed. TMS can result in nonspecific effects, such as auditory and somatosensory stimulation that can affect the EEG response. 26 In this work, we disentangle TMS‐evoked cortical responses and peripheral activation by using an ad hoc sham stimulation. 26 Our sham stimulation succeed in isolating peripheral evoked responses, which were identical between AD and HV, as previously shown in the ERP literature with AD. 50 This is a critical aspect, as it demonstrates the reliability of the observed differences in cortical oscillatory activity between AD patients and HV. Another limitation of the present study is the unavailability of individual MRI scans for the HV group. Thus, we could not directly assess whether there was a difference in the SCD between the 2 groups that could have influenced our results. However, we tend to exclude this hypothesis for a number of reasons. First, we found a specific decrease in the l‐DLPFC, but not in l‐PPC or PC gamma activity, although there was no difference in the induced e‐field among the 3 areas. In addition, we did not observe any difference in the SCD of the 3 areas as computed relative to the standard values used for the HV group. Another limitation of our study lies is that we measured LTP‐like plasticity from the M1 and not directly from the l‐DLPFC. We preferred to use a well‐known established protocol based on MEPs given the excellent accuracy of this parameter in detecting AD pathology, as demonstrated in a previous investigation conducted in large AD samples, 43 , 51 , 52 whereas TMS‐EEG measures still need to be evaluated to measure specific phenomena, such as iTBS‐induced LTP‐like plasticity.

To conclude, our data reveal that AD patients are characterized by a significant reduction of frontal gamma oscillatory activity, confirming the findings reported in animal models. Hence, our results point to TMS‐EEG as a novel method to measure frontal gamma activity in patients with AD. This index could represent a relevant biomarker to predict disease progression and evaluate response to novel pharmacological therapies.

Author Contributions

G.K., E.P.C., E.S., A.M., C.C., and M.C.P. participated in the study concept and design. S.B., E.P.C., I.B., M.A., M.M., M.C.P., C.M., V.P., A.R., F.P., A.D., L.M., L.R., and M.M. acquired and analyzed data. G.K., E.P.C. and D.A.S. contributed to drafting the text or preparing the figures.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

GK and AM hold patents submitted on precision meuromodulation in patients with Alzheimer's disease partially including the methodology described in the current work.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who took part in this study and their families. This study was partially supported by grants to G.K. from the BrightFocus Foundation, the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, The European Union program Horizon 2020 (Neurotwin) and the Italian Ministry of Health. E.P.C. received “Be‐for‐ERC” funding from La Sapienza University.

References

- 1. Scheff SW, Price DA. Synaptic pathology in Alzheimer's disease: a review of ultrastructural studies. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24:1029–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 2004;44:181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iaccarino HF, Singer AC, Martorell AJ, et al. Gamma frequency entrainment attenuates amyloid load and modifies microglia. Nature 2016;540:230–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamamoto J, Suh J, Takeuchi D, Tonegawa S. Successful execution of working memory linked to synchronized high‐frequency gamma oscillations. Cell 2014;157:845–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ribary U, Ioannides AA, Singh KD, et al. Magnetic field tomography of coherent thalamocortical 40‐Hz oscillations in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991;88:11037–11041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007;8:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seeley WW, Crawford RK, Zhou J, et al. Neurodegenerative diseases target large‐scale human brain networks. Neuron 2009;62:42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Byron N, Semenova A, Sakata S. Mutual interactions between brain states and Alzheimer's disease pathology: a focus on gamma and slow oscillations. Biology 2021;10:707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li S, Jin M, Koeglsperger T, et al. Soluble Aβ oligomers inhibit long‐term potentiation through a mechanism involving excessive activation of extrasynaptic NR2B‐containing NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 2011;31:6627–6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koch G, Di Lorenzo F, Loizzo S, et al. CSF tau is associated with impaired cortical plasticity, cognitive decline and astrocyte survival only in APOE4‐positive Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep 2017;7:13728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lorenzo FD, Ponzo V, Bonnì S, et al. Long‐term potentiation–like cortical plasticity is disrupted in Alzheimer's disease patients independently from age of onset. Ann Neurol 2016;80:202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stam CJ, van Cappellen van Walsum AM, Pijnenburg YA, et al. Generalized synchronization of MEG recordings in Alzheimer's disease: evidence for involvement of the gamma band. J Clin Neurophysiol 2002;19:562–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Başar E, Schmiedt‐Fehr C, Mathes B, et al. What does the broken brain say to the neuroscientist? Oscillations and connectivity in schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease, and bipolar disorder. Int J Psychophysiol 2016;103:135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rossini PM, Del Percio C, Pasqualetti P, et al. Conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease is predicted by sources and coherence of brain electroencephalography rhythms. Neuroscience 2006;143:793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Deursen JA, Vuurman E, van Kranen‐Mastenbroek V, et al. 40‐Hz steady state response in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging 2011;32:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rosanova M, Casali A, Bellina V, et al. Natural frequencies of human corticothalamic circuits. J Neurosci 2009;29:7679–7685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferreri F, Vecchio F, Vollero L, et al. Sensorimotor cortex excitability and connectivity in Alzheimer's disease: a TMS‐EEG co‐registration study. Hum Brain Mapp 2016;37:2083–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bagattini C, Mutanen TP, Fracassi C, et al. Predicting Alzheimer's disease severity by means of TMS–EEG coregistration. Neurobiol Aging 2019;80:38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koch G, Bonnì S, Pellicciari MC, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the precuneus enhances memory and neural activity in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage 2018;169:302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koch G, Motta C, Bonnì S, et al. Effect of rotigotine vs placebo on cognitive functions among patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2010372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease: the IWG‐2 criteria. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:614–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr 1997;9:173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fioravanti M, Nacca D, Buckley AE, et al. The Italian version of the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS): psychometric and normative characteristics from a normal aged population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1994;19:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, et al. An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997;11(suppl 2):S33–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology 1994;44:2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rocchi L, Di Santo A, Brown K, et al. Disentangling EEG responses to TMS due to cortical and peripheral activations. Brain Stimul 2021;14:4–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koch G, Olmo MFD, Cheeran B, et al. Focal stimulation of the posterior parietal cortex increases the excitability of the ipsilateral motor cortex. J Neurosci 2007;27:6815–6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stokes MG, Chambers CD, Gould IC, et al. Simple metric for scaling motor threshold based on scalp‐cortex distance: application to studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neurophysiol 2005;94:4520–4527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thielscher A, Antunes A, Saturnino GB. Field modeling for transcranial magnetic stimulation: A useful tool to understand the physiological effects of TMS?. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2015;2015:222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Windhoff M, Opitz A, Thielscher A. Electric field calculations in brain stimulation based on finite elements: an optimized processing pipeline for the generation and usage of accurate individual head models. Hum Brain Mapp 2013;34:923–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Casula EP, Tieri G, Rocchi L, et al. Feeling of ownership over an embodied avatar's hand brings about fast changes of fronto‐parietal cortical dynamics. J Neurosci 2022;42:692–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Casula EP, Pellicciari MC, Bonnì S, et al. Evidence for interhemispheric imbalance in stroke patients as revealed by combining transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroencephalography. Hum Brain Mapp 2021;42:1343–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maris E, Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG‐ and MEG‐data. J Neurosci Methods 2007;164:177–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, et al. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 2005;45:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Başar E, Başar‐Eroğlu C, Karakaş S, Schürmann M. Brain oscillations in perception and memory. Int J Psychophysiol 2000;35:95–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pantev C. Evoked and induced gamma‐band activity of the human cortex. Brain Topogr 1995;7:321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Buzsáki G, Chrobak JJ. Temporal structure in spatially organized neuronal ensembles: a role for interneuronal networks. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1995;5:504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cobb SR, Buhl EH, Halasy K, et al. Synchronization of neuronal activity in hippocampus by individual GABAergic interneurons. Nature 1995;378:75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Richetin K, Steullet P, Pachoud M, et al. Tau accumulation in astrocytes of the dentate gyrus induces neuronal dysfunction and memory deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci 2020;23:1567–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Görtz P, Opatz J, Siebler M, et al. Transient reduction of spontaneous neuronal network activity by sublethal amyloid β (1–42) peptide concentrations. J Neural Transm 2009;116:351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Samidurai M, Ramasamy VS, Jo J. β‐Amyloid inhibits hippocampal LTP through TNFR/IKK/NF‐κB pathway. Neurol Res 2018;40:268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Palmeri A, Ricciarelli R, Gulisano W, et al. Amyloid‐β peptide is needed for cGMP‐induced long‐term potentiation and memory. J Neurosci 2017;37:6926–6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koch G, Di Lorenzo F, Bonnì S, et al. Impaired LTP‐ but not LTD‐like cortical plasticity in Alzheimer's disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis 2012;31:593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gaubert S, Raimondo F, Houot M, et al. EEG evidence of compensatory mechanisms in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2019;142:2096–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andrade‐Talavera Y, Arroyo‐García LE, Chen G, et al. Modulation of Kv3.1/Kv3.2 promotes gamma oscillations by rescuing Aβ‐induced desynchronization of fast‐spiking interneuron firing in an AD mouse model in vitro. J Physiol 2020;598:3711–3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, et al. Amyloid‐β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 2008;14:837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Blennow K, Zetterberg H. Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: current status and prospects for the future. J Intern Med 2018;284:643–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zetterberg H, Bendlin BB. Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease—preparing for a new era of disease‐modifying therapies. Mol Psychiatry 2021;26:296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen MK, Mecca AP, Naganawa M, et al. Assessing synaptic density in Alzheimer disease with synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A positron emission tomographic imaging. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:1215–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Horvath A, Szucs A, Csukly G, et al. EEG and ERP biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease: a critical review. Front Biosci Landmark Ed 2018;23:183–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Motta C, Lorenzo FD, Ponzo V, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation predicts cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2018;89:1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Di Lorenzo F, Motta C, Casula EP, et al. LTP‐like cortical plasticity predicts conversion to dementia in patients with memory impairment. Brain Stimulat 2020;13:1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]