Abstract

dear editor, Dermatological diseases continue to contribute significantly to the burden of disease worldwide, affecting all populations and age groups. Skin disease has been considered the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease globally. 1 Low‐socioeconomic settings reflect a high prevalence of dermatological disease, ranging from 50% to 80% of the population. 2 Despite this high burden of disease in low‐ and middle‐income countries, a shortage of dermatologists is reported for most African countries (Namibia 0·8, Ghana 1·1, South Africa 3, Botswana 3·3 dermatologists per million population) in comparison with the rest of the world (UK 10, USA 36, Germany 65 dermatologists per million population). In Africa, < 1 dermatologist is available per million population, with the majority practising in urban areas. 3 The paucity of dermatologists is concerning, as dermatological disease has substantial impact on long‐term morbidity. 2

This analysis utilized the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) database (from 2000 to 2019) with the variables: (i) category of health personnel (specialty – dermatology); (ii) geographical location; (iii) population category; and (iv) sex. In this article, we have used the term ‘population group’ in line with the definitions in the Population Registration Act (Act No. 30 of 1950), 4 which previously classified South African citizens into four major population categories: ‘white’, ‘coloured’, ‘Indian’ and ‘black’. Although the legislation was repealed in 1991, population categories are still used in reporting in sectors such as the Department of Higher Education. Racialized data continue to be used in monitoring the redress in the education and training of dermatologists who were previously denied access to such training due to legislation. National databases such as Statistics South Africa and the HPCSA also segregate their data based on these same population groups.

Assessment of privatization of dermatology practices was undertaken by geographically mapping each dermatology private practice based on their area codes. This was compared with province‐wide HPCSA registrations and with data procured from the General Household Survey regarding the medically insured population per province in 2019. 5 Ethical approval was obtained from the Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee (reference no. X21/05/010).

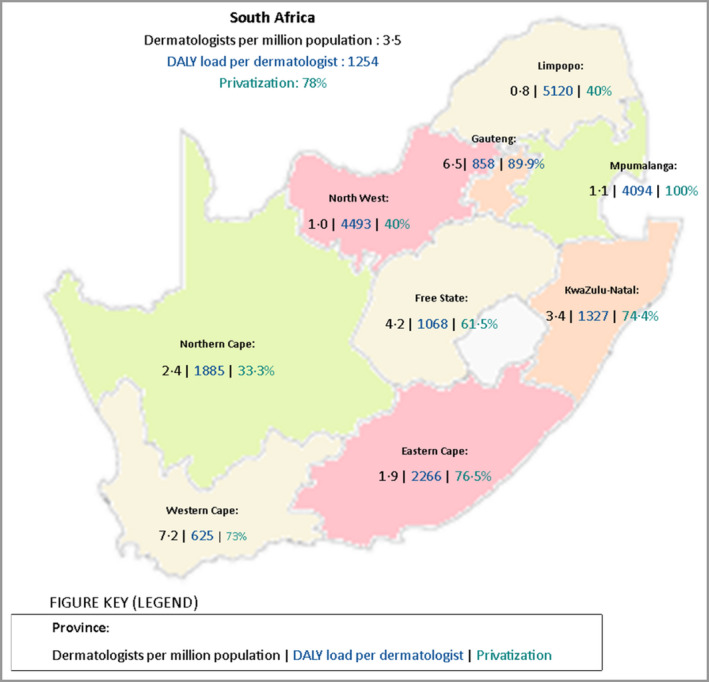

The data were analysed using the SPSS version 22·0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). For the analysis of training capacity and the supply pipeline, data were collected from the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa and the academic heads of dermatology divisions across South African universities. The deficit of dermatologists was forecasted using the disability‐adjusted life‐year (DALY). 6 A DALY represents a lost year of ‘healthy’ life, thus measuring burden of disease. The DALY load per dermatologist was 1254 for SA (2019) (Figure 1), which is lower than in other African countries such as 1313 for Botswana (2021) and 6085 for Namibia (2021), but higher than in developed countries, such as 814 for the UK (2012) and 211 for the USA (2015).

Figure 1.

Status of dermatologists in South Africa, 2019 (dermatologists registered aged ≤65 years). Privatization was assessed by geographically mapping each dermatology private practice based on the area codes of their phone numbers. The numbers of dermatologists operating within the private sector were divided by the total registrations as per the Health Professions Council of South Africa (2019). DALY, disability‐adjusted life‐year.

In total 264 dermatologists were registered (in nine provinces), of whom 208 were aged ≤65 years as registered with the HPCSA in December 2019, amounting to 4·4 practising dermatologists (3·5 for dermatologists aged ≤65 years) per million population. In the public sector the ratio is 1·2 dermatologists and in the private sector 20·1 dermatologists per million population. There is equal distribution of male and female dermatologists (50% each). Most dermatologists are practising in the more densely populated and urbanized areas, with 78% operating in the private sector. The majority (50%) of dermatologists identified themselves as white, followed by black (25%), Asian (18%) and coloured (3%), and 4% were unknown. Of the current trainee dermatologists, 49 are paid registrars who are state funded and 15 are unpaid supernumerary registrars (non‐South African registrars).

The aim in South Africa has been not to increase the number of dermatologists but to provide equitable access to dermatology services in the least performing provinces (high DALY load per dermatologist) and increase the required number of dermatologists to the levels in the better performing provinces (low DALY load per dermatologist) to achieve horizontal equity. The national shortfall for 2030 was projected to be (at least) within the range of 54–95 dermatologists.

The lack of dermatologists affects the public sector and less urbanized provinces to a greater degree. Among medical specialists, a wage differential of up to two times exists, which contributes to the South African dermatology workforce being inequitably distributed across provinces and public and private sectors. Thus, additional rural pay may incentivize retention of dermatologists in rural areas. Additional training of general practitioners and nurses in dermatological care and implementation of teledermatology programmes is also recommended. With enhanced and equitable implementation of human resources for health planning, 7 improved access to dermatological care may be achieved.

Author contributions

Ritika Tiwari: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); methodology (lead); software (lead); validation (lead); visualization (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (supporting). Aqeelah Amien: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); formal analysis (supporting); methodology (supporting); software (supporting); validation (supporting); visualization (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (lead). Willem Izak Visser: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (lead); project administration (supporting); resources (lead); supervision (supporting); validation (supporting); visualization (supporting); writing – review and editing (lead). Usuf Chikte: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (lead); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (lead); project administration (lead); resources (lead); supervision (lead); visualization (supporting); writing – review and editing (lead).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the HPCSA for providing their database for use.

Funding sources: none.

Conflicts of interest: the authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement: The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

Contributor Information

Ritika Tiwari, Email: ritika.t.za@gmail.com.

Aqeelah Amien, Email: aqeelahamien@gmail.com.

Willem I. Visser, Email: wvisser@sun.ac.za.

Usuf Chikte, Email: umec@sun.ac.za.

References

- 1. Flohr C, Hay R. Putting the burden of skin diseases on the global map. Br J Dermatol 2021; 184:189–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hay RJ, Fuller LC. The assessment of dermatological needs in resource‐poor regions. Int J Dermatol 2011; 50:552–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mosam A, Todd G. Dermatology training in Africa: successes and challenges. Dermatol Clin 2021; 39:57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seekings J. The continuing salience of race: discrimination and diversity in South Africa. J Contemp Afr Studies 2008; 26:1–25. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02589000701782612 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Statistics South Africa . General household survey 2019. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182019.pdf (last accessed 5 April 2022).

- 6. Tiwari R, Bhayat A, Chikte U. Forecasting for the need of dentists and specialists in South Africa until 2030. PLOS ONE 2021; 16:e0251238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Department of Health . 2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy: Investing in the Health Workforce for Universal Health Coverage. Pretoria: Government Printers, 2020. [Google Scholar]