Abstract

As developmental scholars increasingly study ethnic and racial identity among white youth, careful reflection is needed regarding its framing, implementation, and interpretation. In this three‐part conceptual paper, we offer a foundation for such reflection. First, we discuss the sociocultural context of white supremacy that shapes U.S. society, psychology, and adolescent development, and situate the study of ethnic and racial identity among white youth within this context. Second, we consider Janet Helms’s White Racial Identity Development model, reviewing theory and research building on her argument that race—and whiteness, specifically—must be centered to achieve racial justice‐oriented scholarship on white identity. We conclude by offering four guiding insights for conducting critical research on racial identity development among white youth.

Keywords: racial identity, white racial identity development, ethnic‐racial identity, whiteness, white supremacy, racism

White youth—like all youth in the United States—grow up in a sociocultural context of systemic racial inequity (Kendi, 2019; Tatum, 2017). This racist structure shapes their daily experiences, with particular relevance for ethnic and racial identity development (Rivas‐Drake & Umaña‐Taylor, 2019; Williams et al., 2020). Yet, most white youth downplay or reject the importance of race altogether (Dottolo & Stewart, 2013; Moffitt et al., 2021; Rogers & Meltzoff, 2017). This disconnect reflects the prevalence of racial colorblindness (Neville et al., 2013), a perspective that minimizes or denies the existence and impact of race and racism. Racial colorblindness is dominant in U.S. schools (Aldana & Byrd, 2015) and shapes how white parents talk, or do not talk, to their children about race (Hagerman, 2018; Perry et al., 2019; Sullivan et al., 2021). Thus, white youth are explicitly and implicitly taught that race does not matter, while simultaneously experiencing systematic privilege on the basis of race (Rogers, Moffitt, & Foo, 2021; Spencer, 2006, 2021; Sue, 2006; Tatum, 2017). How white youth make sense of their racial identities in the context of racial privilege, however, is rarely conceptualized as focal or relevant to their normative development.

The dearth of research on white youths’ racial identity development reflects long‐standing racist ideologies, specifically white normativity and supremacy, that shape U.S. society (Feagin & Ducey, 2019) and the field of psychology (Dupree & Kraus, 2021; Guthrie, 1998; Yee et al., 1993). White normativity assumes whiteness to be the objective standard of development, while white supremacy asserts that white people are innately superior to all other people (Lesko, 2012; Perry, 2002). White supremacy is more than racial violence or far‐right ideology; it encompasses a system of practices, beliefs, and policies that privilege whiteness and center the interests and experiences of white people (Hooks, 1992). Both white supremacy and normativity shape who and what is studied in developmental science (Causadias et al., 2018; Rogers, Niwa et al., 2021; Spencer, 2021). While there have been multiple calls for more thorough investigations of power and privilege in child and adolescent development (Kornbluh et al., 2021), particularly in relation to white youth (Hazelbaker et al., 2022; Rogers, 2019; Seaton et al., 2018; Spencer, 2017), developmental research in this area remains limited.

In the current conceptual paper, we respond to these calls, presenting a three‐part case for studying racial identity development among white youth. First, we articulate what developmental research in a white supremacist society can and should entail, offering sociocultural and historical context to the relative dearth of research on white adolescents’ racial identity development. We link this discussion to the broader literature on racial and ethnic identity, highlighting the pitfalls of applying constructs and measures designed for use among racially minoritized populations to white samples. Second, we turn to Helms’s (1990, 2020) model of White Racial Identity Development (WRID), reviewing qualitative applications of this model to illustrate its relevance for developmental research, including among white adolescents. Third, we present four guiding insights for conducting developmental scholarship on white racial identity.

Part I: Conceptualizing Adolescent Development in a Society Shaped by White Supremacy

The systemic privileging of whiteness shapes individuals’ opportunities and experiences across the lifespan. Incorporating this reality into developmental theory requires an intentional engagement with white supremacy as a macro‐level process that is reinforced and resisted at the micro‐level of interactions and individual beliefs, behaviors, and identities, including during adolescence (Helms, 1990, 2020; Rogers, Niwa et al., 2021; Rogers & Way, 2021; Spencer, 2021; Sue, 2006). White youth are socialized into a society that rewards both whiteness and silence on whiteness—denial about, ignorance of, and self‐distancing from the racist status quo (Knowles et al., 2014; Spanierman & Cabrera, 2014). Sociologist Joe Feagin calls this the white racial frame, a collective denial of the vast racial inequity shaping U.S. society, coupled with, “a broad and persisting set of racial” ideologies and narratives, including racial colorblindness, that uphold the very inequity being denied (Feagin, 2020, p. 11). Shifting this frame requires naming and understanding it, including in developmental science.

For example, in Quintana’s (1998, 2007) racial perspective taking model, he highlights cognition and social experience as two necessary components for the development of novel and nuanced understandings of race and racism. As children move into adolescence, their cognitive capacity for abstract thinking increases (Quintana, 2007). Yet, without explicit input from sources including teachers, peers, parents, and social media, white youth are unlikely to engage in meaningful interrogation of the ways in which race shapes their environment and development, including in relation to their experiences of racial privilege (Moffitt et al., 2021; Quintana, 2007).

A white adolescent, for instance, who attends a racially segregated school (like the majority of youth in the United States; Geiger, 2017) and grows up in a racially segregated neighborhood (as most white youth in the United States do; Frey, 2020), is unlikely to connect their circumstances with centuries of oppressive policies and practices privileging whiteness, unless they are intentionally and actively socialized to do so (Perry, 2002; Tatum, 2017; Thomann & Suyemoto, 2018). Yet, even if explicit anti‐racist socialization occurs, the status quo of white normativity is fortified throughout the adolescent’s ecosystem by white‐dominated media (Arana, 2018), white‐centric school curriculum (Aldana & Byrd, 2015), and the overrepresentation of white people (and white men in particular) in politics (Bialik, 2019), just to name a few examples. Ensconced in this sociocultural context, white supremacist inequity is reinforced as normal; just how it is. This perspective is learned and internalized by many white youth, often taking the form of racial colorblindness (Moffitt et al., 2021; Rogers, Moffitt, & Foo, 2021). Moreover, the normativity of whiteness is reflected in developmental theory. Identity is a core development process during adolescence (Erikson, 1968)—so we must ask ourselves, why is it that theoretical and empirical research on racial identity development among white adolescents is so limited?

White parents, teachers, and other white adults often claim that white youth in childhood and early adolescence are too young to learn about the harms of racism (Garlen, 2018). Yet, their same‐age peers of color are experiencing such racism firsthand (Brown et al., 2011), and are more likely to name it and make meaning about it than white youth (Rogers, Moffitt, & Foo, 2021). Thus, the shielding of white youth from learning about the very systems of oppression from which they are benefitting is not related to developmental capacity, but to white normativity. Because racially colorblind perspectives are dominant among many white adolescents (Pauker et al., 2015), racial identity development can seem stagnant among this population. However, learning to negate race is itself highly relevant for youth development, both as a process and as an outcome, and with implications at the individual and societal levels (Apfelbaum et al., 2010). A critical study of adolescent development thus requires research questions, methods, and measures that move beyond pure age‐related differences (McLean & Riggs, 2022) to center the realities of growing up in a society shaped by white supremacy.

How white youth talk about and make meaning about race—even if they are downplaying its importance—is developmentally relevant. For instance, a white 12‐year‐old may interpret race‐related societal messaging and interpersonal experience differently than a white 16‐year‐old, but if the impact of their reasoning at both time points supports racially colorblind ideology, that is not a neutral or irrelevant finding. We therefore need more developmental research examining if, when, and how white adolescents learn to justify or resist the deeply engrained societal norms of white supremacy, including through racially colorblind perspectives. Thus, we might ask, how are white youth making meaning about their racialized experiences and interactions as they grow up? What kind of logic is being engaged, and when, why, and how does this change over time? In which ways do white youth make identity‐related meaning that aligns with or contradicts racial colorblindness and white supremacy? Adequately engaging such research questions requires an anchor in sociocultural and historical context.

An Historical Perspective: Racism, Whiteness, and Psychology

The United States and the field of psychology have a long and intertwined history with racism and preoccupation with the superiority of whiteness (Guthrie, 1998). While the boundaries of whiteness have shifted over the centuries, it has consistently been upheld as normative, desirable, and powerful (Feagin & Ducey, 2019). In the first U.S. census in 1790, individuals were not asked to report their ethnicity or heritage, but were divided into “free white males (separated by age), free white females, other free persons, and slaves” (Loyd & Gaither, 2018, pp. 64–65). The category “white” has remained a constant with each subsequent census, though all additional racial and ethnic groups have changed over time, as who is and is not included in the “white” group has shifted in relation to sociopolitical interests and immigration flows. Decisions regarding the boundaries of whiteness are political, but empirical research, and psychological research in particular, has played a pivotal role in legitimizing white supremacy through science. Indeed, a key aim of psychology when it was established as a discipline in the 19th century was to offer so‐called scientific evidence of racial hierarchy, specifically through the use of intelligence and aptitude testing designed to elevate white people as superior to all others (Guthrie, 1998). Intelligence testing remained common through the 1930s, when many of the pseudo‐scientific arguments for biology‐based racial hierarchies, known as eugenics, were adopted by the Nazis and subsequently lost favor in the United States (Guthrie, 1998; Winston, 2004).

Following WWII, there was a boom of psychological inquiry into bias, prejudice, and intergroup relations, largely situated as an attempt to understand how and why the horrors of the Holocaust had been carried out in Nazi Germany. Much of this work focused on the formation and maintenance of ingroups and outgroups, often in laboratory settings (Hornsey, 2008). Notable to the historical through lines of race in psychology, no such research boom occurred in relation to the racialized justification for centuries of chattel slavery, the thousands of racial terror murders of Black Americans through the 1960s, or the white supremacist cultural doctrine of Manifest Destiny and related genocide and forced assimilation of millions of Native Americans. On the contrary, the Holocaust was situated as a great aberration, reinforcing the fallacy of the United States as a free, equal, and just society. This false framing has been foundational in the quest among many researchers to understand and root out malevolent behavior at the individual level, often without acknowledging the ever‐present history of white supremacy in U.S. society (Feagin, 2020) and in psychology (Dupree & Kraus, 2021).

Many psychological frameworks still assess prejudice, bias, and racism at the individual level (Dovidio et al., 2017), with the bulk of this research conducted among predominantly white participants (Roberts et al., 2020). While it is unquestionably important to understand the roots, development, and impact of white individuals’ racial attitudes, doing so has often situated the concept of race, and relatedly racial identity, as something “other” people have (Salter et al., 2017). The race‐related beliefs and behaviors white people have about Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) are centered, but the experience of being white in a society structured by white supremacy is not often taken into consideration. This has two key consequences. First, it holds whiteness as normative and largely invisible, reinforcing the existing racial hierarchy. Second, it situates racism in the minds and actions of individuals, while structural systems of power and oppression, even when named, are pushed to the margins (Salter & Adams, 2013; Syed, 2021). Because individuals are embedded in systems, however, the links between individual beliefs and behaviors and societal norms, policies, and narratives are mutually reinforcing (Galliher et al., 2017; Rogers, 2018). Recent research has examined, for instance, how individual racist microaggressions reinforce and legitimize societal systems of oppression (Skinner‐Dorkenoo et al., 2021). Recognizing racism as “a system of advantage based on race” therefore situates the study of race in sociocultural context (Tatum, 2017, p. 87; italics added).

The Emergence of Racial and Ethnic Identity Development

Situating individuals within sociocultural context was at the heart of early work on racial identity development. In the decades after legalized racial segregation was overturned, research on racial identity as a construct distinct from race and racial differences began to take hold. Rather than studying negative attitudes about racial outgroups or conceptualizing preference for one’s own racial group as a form of ingroup bias (Sellers, 1993), early racial identity scholars argued for the need to investigate how Black people understand the personal, social, and political meaning of Blackness and the value of ingroup identification; that is, to understand how Black people form a racial identity in the context of white supremacy (Cross, 1971; Sellers, 1993).

Psychologists situated primarily in the clinical, counseling, and social subfields, namely, Cross (1971), Helms (1990), and Sellers et al. (1998), put forth models of Black racial identity that assessed individual engagement with power, privilege, and oppression. These models were conceptualized for use among Black adults and were not linked to socio‐cognitive maturation across developmental periods. Instead, they focus squarely on the sociocultural context (Cross, 1971) and on elements such as racial pride and centrality (Sellers et al., 1998), or what is now labeled identity content (Hudley & Irving, 2012). In response to Black racial identity models, Phinney (1992), a developmental psychologist, introduced the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM). The MEIM builds on Erikson’s (1968) theory to examine the process of identity development, with a specific focus on adolescence. Phinney centered ethnicity rather than race, assessing the ways in which youth learn about (exploration) and feel attached to (commitment) their ethnic heritage. A decade later, Adriana Umaña‐Taylor et al. (2004) developed another Eriksonian measure, the Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS), assessing ethnic identity exploration, affirmation, and resolution. Both the MEIM and EIS were designed to be universal measures, adaptable and equivalent across ethnic groups.

As research using each of each of these measures and models increased, the expanding bodies of literature on racial and ethnic identity were brought together, with scholars finding links between their various facets and adaptive and protective psychosocial outcomes across diverse BIPOC youth (Rivas‐Drake et al., 2014). The Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group (Umaña‐Taylor et al., 2014) therefore put forth the meta‐construct of ethnic‐racial identity (ERI), which encompasses the content‐oriented aspects of racial identity (e.g., racial pride and centrality) and the process‐oriented aspects of ethnic identity (e.g., exploration and commitment). Importantly, in their conceptual paper arguing for the merging of these identity constructs, both their review of existing research and recommendations for the future focused exclusively on BIPOC youth (Williams et al., 2020), as none of the aforementioned ERI models were developed with white youth in mind.

Yet, this history is very rarely mentioned in contemporary research. As the number of studies using these measures to assess ERI among white youth increases, recognizing the origins and trajectories of these constructs is important. When scales such as the MEIM and EIS are employed, white youth consistently report lower ERI than their BIPOC peers (Phinney, 1992; Walker & Syed, 2013), regardless of which aspect is measured. Multiple scholars have assessed the psychometric properties of ERI scales, including to investigate their functionality among white youth. In a recent study (Sladek et al., 2020), the authors found that white adolescents reported systematically lower ERI than BIPOC adolescents, though the factor structure of multiple ERI measures was equivalent across groups. Similarly, Syed and Juang (2014) found that white college students reported lower ERI than Students of Color, but links between ERI and psychological functioning were consistent across groups. In the latter study, the authors found that ERI was significantly higher among students who reported a specific ethnicity in their surveys, as compared to those who wrote “white” or “Caucasian” when asked to provide their ethnic group (Syed & Juang, 2014).

The findings from these psychometric evaluations highlight a key tension in using scales designed for racially minoritized youth to study ERI among white youth. While some white youth may learn about and feel pride in their ethnic heritage, many write “white” when prompted to provide their ethnic group (Grossman & Charmaraman, 2009; Syed & Juang, 2014). Can white pride carry the same meaning as Black or Latinx pride? Does a sense of belonging to whiteness signify positive ethnic group belonging? Based on the long history of white supremacy shaping U.S. society, as well as the writings of early ERI scholars (Phinney, 1996; Sellers, 1993), the answer to these questions is clearly “no.” Existing ERI scales cannot assess how white youth understand the consequences of white supremacy because they were not designed to do so. By focusing on ethnic or cultural ancestry, scales such as the MEIM and EIS obfuscate the ways in which white youth develop racial identity, failing to capture meaning making related to whiteness and racial inequity.

Although some ERI measures may be psychometrically sound across ethnic and racial groups, we have strong reservations about the external validity and conceptual underpinnings of these constructs for use among white youth, particularly if authors focus solely on individual‐level constructs (attitudes and behaviors) without situating their research in sociopolitical context (racial privilege and white supremacy) (Rogers, Niwa et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2020). Thus, to move toward anti‐racist scholarship, we need to examine racial identity development among white youth, rather than ERI or ethnic identity. Doing so requires different models, measures, and research questions, ones designed to assess racial identity among white individuals within a white supremacist society.

Part II: Helms’s White Racial Identity Development Model

Helms’s (1990, 2020) White Racial Identity Development (WRID) model offers one framework for a contextualized study of white identity. Additional frameworks assessing whiteness have been put forth (for reviews, see Hays et al., 2021; Schooley et al., 2019), including models focusing on white racial consciousness (Rowe et al., 1994), white identity centrality (Knowles & Peng, 2005), white guilt (Grzanka et al., 2020), and the psychosocial costs of racism to whites (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004). Some of these models were developed in response to Helms, based in particular on psychometric critique of the scales used to measure WRID quantitatively (Behrens & Rowe, 1997; Rowe, 2006). We acknowledge this critique and agree with previous assessment (Spanierman & Soble, 2010) that the problems relate to condensing a highly complex theoretical model into quantifiable items, meaning it does not negate the value of the theory itself, but instead demands greater phenomenological inquiry to understand its real‐world applicability. Furthermore, despite the critique, most subsequent frameworks have drawn on Helms’s work, and the WRID model integrates many elements of subsequent models, offering a cohesive toolkit for understanding their interconnectedness. We therefore argue that, even if scholars studying racial identity among white youth do not directly apply the WRID model, they can and should recognize Helms’s (1990, 2020) work as a theoretical foundation for the psychological study of white racial identity development.

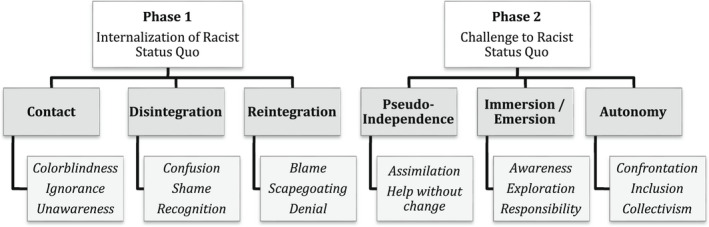

Initially conceptualized as a stage model and offered as a counterpart to her model of Black racial identity development (Helms, 1984, 1990), the WRID framework drew on Cross’s (1971) early work to understand the identities of white adults. Thus, it was not conceptually tied to developmental milestones based on socio‐cognitive maturation; age‐related change is neither assumed nor theorized. It is presumed, however, that individual growth combined with societal events prompts change, and that progression through the model requires learning and reflection (Helms, 1990, 2020). In recent years, Helms (2017, 2020) has moved away from the language of stages, making clear that what she now calls the six schemas comprising the WRID model (see Figure 1) are neither mutually exclusive nor rigidly linear; both progression and regression can occur, and individuals often hold perspectives that fit within multiple schemas. Drawing on this model to study adolescent identity development, WRID offers a framework for articulating if, when, and how white adolescents learn to justify or resist the norms of white supremacy—not purely as a function of their age or cognitive stage, but their ongoing development within and negotiation of the sociocultural context of racism. In the following, we offer an overview of the WRID phases and schemas, before discussing qualitative applications of this model and related implications for adolescent development.

Figure 1.

Overview of WRID phases, schemas, and primary characteristics. Note. This flowchart is adapted from the theoretical WRID model as described by Helms (2020).

WRID Phase 1

Phase 1 of the WRID model is comprised of three schemas, which are characterized by internalization and maintenance of the racist societal status quo. Helms (1990, 2020) notes that many white adults remain in Phase 1 of racial identity development indefinitely, meaning they do not explicitly recognize the ways in which whiteness has shaped their lives. Thus, it is neither surprising nor insignificant if white adolescents are also clustered here. The initial schema in Phase 1, Contact, is primarily typified by “innocence, ignorance, or neutrality about race and racial issues” (Helms, 2020, p. 27). Individuals primarily situated in Contact tend to employ a colorblind racial ideology, downplaying the importance of race and remaining in denial or oblivion regarding the impact of racism. Disintegration, the second WRID schema, is primarily characterized by confusion, guilt, and shame. In this schema, the white person becomes aware of race and racism, but feels caught in a quandary because the new information they are faced with clashes with the racially colorblind perspectives they had internalized (Helms, 2020). If white individuals navigate this tension by placing blame for racial inequity on racially minoritized populations, and engage in scapegoating or overt racism, then they can be situated in the third WRID schema, Reintegration. Here, the person acknowledges racism but has fully reintegrated into the status quo, embracing whiteness as normal and superior and using racial inequity as “proof” of the inferiority of BIPOC individuals (Helms, 2020).

WRID Phase 2

When white individuals are pushed toward greater reflection on the reality of systemic racism, they may then engage Phase 2 schemas. The three schemas that comprise Phase 2 are characterized, to varying degrees, by a rejection of the status quo and internalization of an anti‐racist white identity. Helms (2020) argues that the shift to Phase 2, “probably requires a catastrophic event or a series of personal encounters that the person can no longer ignore” (p. 28). Thus, it is intentional or explicit acts or events that prompt the white person to develop from a colorblind racial identity to an anti‐racist racial identity. Gaining a better understanding of such events and how white youth make sense of them will greatly strengthen developmental research in this area (Hazelbaker et al., 2022).

In the Pseudo‐Independence schema, the first of Phase 2, a view of white superiority is replaced with a perspective of white normativity. Helms (2020) describes the beliefs adopted in this schema as white liberalist, in which white people try to help BIPOC individuals without interrogating the white supremacist roots of racial inequity. Helms (2020) argues that this schema is relatively stable, as white people promote the assimilation of BIPOC individuals into existing norms and structures rather than pushing for fundamental change to the system. If the white person gains greater awareness of the problematic implications of assimilation, they may shift into the second Phase 2 schema, Immersion‐Emersion, which includes active exploration of race and racism on a personal and societal level. This means that the white person reflects on how whiteness has shaped their own experiences, thinks critically about interpersonal and structural racism, and seeks ways to confront it. In the final WRID schema, Autonomy, white individuals are involved in ongoing personal reflection and societal engagement with the aim of dismantling systemic oppression (Helms, 2020). Importantly, racial identity is not viewed as static within the WRID model, meaning that maintaining the beliefs, actions, and behaviors characteristic of Autonomy, for instance, requires ongoing learning and engagement, as anti‐racist white identity runs counter to the norms of our white supremacist society.

Given that adolescence is a time of significant identity exploration, self‐curiosity, and discovery, it may be a prime opportunity for white adolescents to move into Phase 2 schemas, questioning established norms and exploring the meaning and significance of race and whiteness for themselves (Thomann & Suyemoto, 2018). At the same time, because awareness of social expectations and pressures to fulfill social roles also intensify during the teenage years, white youth may assume their role in the racial hierarchy, reinforcing white supremacist norms and remaining in the Phase 1 schemas.

Applying the WRID Model to Study White Racial Identity

Numerous researchers have employed the WRID model. Because we are focusing on the theory and its application, rather than the quantitative measurement model, we reference only qualitative work. Tatum (1992) offered an early application, using the WRID model as a lens to interpret and situate her white students’ engagement and growth over the course of an undergraduate seminar on racism in psychology. Tatum discusses how her framing of the course material helped to push students toward critical reflection, although many went slowly through the WRID schemas, expressing anger, guilt, and shame before coming to terms with the reality of racism and their role within a racist system (Tatum, 1992). In a similar study examining white graduate students’ reflective writing, the authors found that, over the course of a semester‐long class on multicultural counseling psychology, the scope and depth of students’ reflections shifted from aligning primarily with Phase 1 to primarily Phase 2 (Dass‐Brailsford, 2007), indicating that critical education may act as a racial identity development intervention. In a phenomenological study of white adults self‐identified as anti‐racist activists (Malott et al., 2015), the authors found that many participants felt alienated from other white people who were less reflective about race and whiteness, many centered a critical perspective on whiteness as a central aspect of their racial identities, and many discussed being anti‐racist as a practice rather than a static identity. Each of these aspects aligns with Helms’s (2020) conceptualization of the latter schemas of white racial identity, underscoring the multifaceted and dynamic nature of racial identity development as embedded in the sociocultural context.

Our own recent study (Moffitt et al., 2021) marked the first application of the conceptual WRID model among a youth sample, as far as we are aware. Based on analysis of qualitative interviews conducted at two time points with white youth in middle childhood (M age at T1 = 9.00, SD = 1.73) and early adolescence (M age at T1 = 11.62, SD = 0.50), we found that most participants primarily made statements that reflected Phase 1 schemas. There was a shift over time toward Phase 2, however, particularly among participants in early adolescence. This suggests that white racial identity development may be undergirded by socio‐cognitive development. Yet, we also found high variability across our sample, with nearly all participants making statements coded across multiple schemas, making clear that age alone does not predict anti‐racist white identity.

Our findings with white youth (9–11 years old; Moffitt et al., 2021) align with Quintana’s (1998, 2007) racial perspective taking model, which suggests that children are aware of racial groups and their own racial identities from a very early age, but how they make sense of race and race related experiences changes as they gain both experiential knowledge and greater cognitive ability to process it. Our findings also align with Helms’s (2020) theorizing that many white adults remain situated in Phase 1, and those who do progress to Phase 2 primarily engage the Pseudo‐Independence schema, which was indeed what we found in our youth sample. This underscores that socio‐cognitive skills should not be understood as the cause of critical, anti‐racist disruption and identity, but rather as a developmental prerequisite. As Helms (1990, 2020) notes, interpersonal and societal events and experiences catalyze white racial identity development. For white youth, the socialization received from teachers, parents, peers, social media, and other sources, all represent such catalysts, presenting opportunities for both progression and regression across the WRID schemas.

Part III: Implications for Adolescent Research

In our adaptation of the WRID model to white youth, we aimed to interpret their individual reflection and meaning making in relation to race, racism, and whiteness within a socioculturally situated framework (Rogers, Moffitt, & Jones, 2021). That youth listen to, internalize, and make personal meaning from the messages they hear from parents, teachers, and broader society is well established. Among BIPOC youth, messages specifically in relation to ethnicity and race have long been examined within the paradigm of ethnic‐racial socialization (Priest et al., 2014). Fewer researchers have studied the parallel messaging white youth receive (or do not receive), although research in this area is increasing (Hagerman, 2018; Hughes et al., 2008; Loyd & Gaither, 2018; Perry, 2002; Perry et al., 2019; Sullivan et al., 2021). A recent study (Ferguson et al., 2021) examined parental white racial socialization through the lens of the WRID model, finding that white mothers who espoused perspectives aligned with Phase 2 schemas were more likely to engage in race‐conscious parenting, whereas white mothers situated in Phase 1 schemas (who represented the majority of the sample) tended to engage racial colorblindness or remain silent on race‐related topics with their children. The socialization of racial colorblindness has clear implications for youth development.

As racial identity scholars aiming to conduct a racial justice‐oriented analysis, we also grappled with the convenience and ease of colorblind reasoning. As we coded our own data of white youths’ race related statements, we found ourselves questioning the implications of what they told us, thinking: they’re just repeating what their parents have said, he just heard his teacher say that, she’s just telling you what she thinks you want to hear. Yet, anchoring our analysis within the WRID model allowed us to recognize that the messages these white youth were conveying, even if (or particularly if) repeated from others, are meaningful, at both the individual and societal levels. A white 6th grader saying, for instance, that race, “just really doesn’t matter,” (Moffitt et al., 2021) tells us something about her own racial identity, about the socialization she is receiving, and about the society she lives in. To assert that race “really doesn’t matter” in a society wherein one’s racial positionality predicts life outcomes and longevity is meaningful. Thus, bringing together our own research experience with the conceptual, historical, and empirical work we have outlined thus far in this paper, we offer four guiding insights for research on racial identity development among white adolescents.

First, We Should Use Models Designed to Assess Whiteness in Context

Much of the existing research on ERI among white youth reinforces the narrative that ethnic and racial identity are of limited importance to this population. Scales designed to measure the process and content of ERI development among racially minoritized individuals focus on constructs such as group belonging, importance, and understanding (Phinney, 1992; Sellers et al., 1998; Umaña‐Taylor et al., 2004). Due to the nature of white supremacy and normativity in our society, these constructs cannot offer a racial justice‐oriented, socioculturally relevant assessment of how white youth develop their identities as racialized beings (Helms, 1996, 2007; Helms & Talleyrand, 1997; Spencer, 2021). ERI development cannot be measured as a universal process, as it is shaped by one’s positionality within a white supremacist system.

Thus, we encourage researchers to disentangle ethnic and racial identity development when studying white youth, and to center the latter. In our own research, drawing on a framework designed to investigate how white individuals develop a racial identity in the context of white supremacy allowed us to go beyond the “race does not matter” finding to investigate if, when, and how white youth resist or reiterate racial inequity. Such person‐in‐context analysis demonstrates the nuanced identity work white youth are engaged in, even in early adolescence, and even when many simultaneously reiterate racially colorblind claims (Rogers, Moffitt, & Foo, 2021). The WRID model offers one framework to make sense of these seemingly contradictory identity narratives, offering a lens through which to interpret the complexities of navigating racialized experiences and colorblind racial socialization.

Second, We Should Move Beyond Relying on Age‐Related Change to Explain Development

Age‐related models are attractive and informative in some ways, but also limited in their capacity to center the macro‐system in developmental processes (McLean & Riggs, 2022; Rogers, Niwa et al., 2021). Although the WRID model is not developmental in terms of outlining anticipated age‐related change over time, situating participants’ statements across the six schemas allows developmental researchers to examine changes in response type and topic across participants and interview time points. Yet, we are not familiar with any research engaging the WRID model that assesses change in the complexity or content of participants’ statements coded into a single schema, a task we encourage scholars to take up in the future. Because many white individuals maintain racially colorblind perspectives across the life course (Helms, 2020), we need more developmental scholarship examining both the content and process of micro‐level maintenance and perpetuation of the macro‐level ideology of white supremacy. We need to shift our science to recognize that for white youth, development into a white supremacist system necessarily entails some level of learning to discount, downplay, and ignore that system, while simultaneously benefitting from it (Sue, 2006). Understanding this process, as well as its implications, can only occur if we name and center systemic inequity within our science.

Furthermore, recognizing the status quo of inequality, we encourage scholars to study resistance to oppressive systems as part of normative development, including among white youth (Rogers & Way, 2021). Numerous theoretical models put forth over the past decades (Diemer et al., 2017; Garcia‐Coll et al., 1996; Spencer, 2006) have offered foundations for studying resistance to oppression among BIPOC youth, highlighting the ways in which this developmental construct can be adaptive and protective, and is incorporated into one’s identity. Parallel processes among white youth remain under studied. Resistance to racial and other forms of societal oppression and inequity is not the responsibility of People of Color alone. By expanding our science to better understand if, how, and when white youth resist the white supremacist status quo, we can shift the field toward greater equity.

Third, We Should Reflect on How Our Own Identities Shape our Work

Fundamental to meaningful and impactful change, researchers need to (a) engage in critical interrogation of their own identities, particularly in the case of white researchers, and (b) name the ways in which whiteness, race, and structural racism shape and show up in their research. Just like the youth we study, we are living in a white supremacist society, and our research either works to uphold or disrupt this reality. If (white) scholars conduct research on adolescent development without engaging in a critical examination of their own racial identities, they may reinforce white supremacist norms. Engaging in critical reflection of one’s racial identity goes beyond including a reflexivity or positionality statement in one’s research, although we certainly advocate for this practice. White scholars can consult Helms’s framework, particularly as outlined in her recent book A Race is a Nice Thing to Have (2020), in an effort to examine how whiteness informs their own identities and how they conduct research.

Scholars including Helms have encouraged (white) researchers to undertake this type of identity work for decades (Helms, 1993), and numerous papers in recent years have outlined steps for greater researcher reflexivity on race, racism, and whiteness (Boykin et al., 2020; Dottolo & Kaschak, 2015; Spanierman et al., 2017). Shifting the conversation to speak with developmental psychologists in particular, we hope to spur reflection on the intertwined implications of researcher identity and what and who are centered when we study what is often called normative development. If white scholars critically interrogate the ways in which whiteness has benefitted them personally, if they recognize that much of what they have been taught and have internalized is white centered and white supremacist, if they acknowledge their own racialized identity as a white person and what that means for their lived experience, they will be better equipped to conduct research that moves, “beyond discovering Whiteness once again to the more difficult challenge of deconstructing it” (Helms, 2017, p. 724).

Fourth, We Should Apply an Anti‐Racist Lens to the Terms and Constructs in our Work

Doing such work may necessitate resistance even to the official standards in our field. The current American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines outlined in the 7th edition of the style manual explicitly advocate for “bias free” language, yet state that either “White” or “European American” is acceptable for describing “people of European origin” (APA, 2019). The term “European American,” when used interchangeably with “White,” not only erases the multitudinous ethnic and racial diversity within historical and contemporary Europe, thereby reinforcing white normativity across national contexts, but also situates whiteness as a matter of heritage, as though it were a neutral and natural construct. Researching “European American” ERI is not equivalent to researching white racial identity; treating these terms interchangeably bolsters the invisibility of white supremacy and whiteness as a construct of power.

If researchers choose to study ERI development across ethnic and racial groups, which can and does offer relevant insights, we recommend explicitly acknowledging the historical through line of white supremacy in the United States and being clear that racism is a structure which denigrates BIPOC and elevates white people, rather than situating racism solely in terms of individual beliefs and behaviors. Furthermore, researchers can include additional measures tapping into elements of white racial identity, such as awareness of white privilege (Hays et al., 2007), the psychosocial costs of racism to whites (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004), or critical reflection and action on inequity (Diemer et al., 2017), to understand the different developmental and societal implications of ethnic versus racial identity among white youth. Counseling psychology, in particular, offers a wealth of research on whiteness, which can be drawn on to expand developmental theory in this area (Grzanka et al., 2020; Schooley et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Studying racial identity among white youth is one way to contribute to disrupting the invisibility of white supremacy and normativity in developmental science. Adolescence is a time of rapid increases in cognitive capacity paired with greater exploration of the self and one’s role in society (Erikson, 1968; Quintana, 1998, 2007). Understanding if, when, and how, white youth internalize and accept or recognize and resist the white supremacy shaping our society will strengthen developmental research broadly and identity research in particular. We thus advocate for more developmental scholarship that resists the racist status quo by naming the structures upholding it and examining the ways in which coming generations may work to dismantle it. Adequately doing so requires specific engagement with white supremacy as a context of development, which cannot be captured using existing ERI measures alone. Instead, we advocate for greater exploratory and phenomenological research drawing on Helms’s (1990, 2020) foundational WRID model, which can push scholars to look beyond age‐related development to interrogate the ways in which white youth alternately reiterate or resist the racist societal structures they are being socialized into throughout childhood and adolescence. Such an approach acknowledges and positions developmental scientists to disrupt the normativity of white supremacy in our science and society.

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding for this manuscript was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship awarded to Dr. Moffitt from the National Science Foundation (NSF) SBE (#2005052), as well as by postdoctoral fellowships awarded to Dr. Rogers from the National Science Foundation (NSF) SBE (#1303753) and the Spencer Foundation/National Academy of Education (NAEd) Postdoctoral Fellowship.

References

- Aldana, A. , & Byrd, C. M. (2015). School ethnic–racial socialization: Learning about race and ethnicity among African American students. The Urban Review, 47(3), 563–576. 10.1007/s11256-014-0319-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2019, September). Racial and ethnic identity. https://apastyle.apa.org/style‐grammar‐guidelines/bias‐free‐language/racial‐ethnic‐minorities [Google Scholar]

- Apfelbaum, E. P. , Pauker, K. , Sommers, S. R. , & Ambady, N. (2010). In blind pursuit of racial equality? Psychological Science, 21(11), 1587–1592. 10.1177/0956797610384741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arana, G. (2018, November 5). Decades of failure. Columbia Journalism Review. https://www.cjr.org/special_report/race‐ethnicity‐newsrooms‐data.php [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, J. T. , & Rowe, W. (1997). Measuring white racial identity: A reply to Helms (1997). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44, 17–19. 10.1037/0022-0167.44.1.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bialik, K. (2019, February 8). For the fifth time in a row, the new Congress is the most racially and ethnically diverse ever. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact‐tank/2019/02/08/for‐the‐fifth‐time‐in‐a‐row‐the‐new‐congress‐is‐the‐most‐racially‐and‐ethnically‐diverse‐ever/ [Google Scholar]

- Boykin, C. M. , Brown, N. D. , Carter, J. T. , Dukes, K. , Green, D. J. , Harrison, T. , Hebl, M. , McCleary‐Gaddy, A. , Membere, A. , McJunkins, C. A. , Simmons, C. , Singletary Walker, S. , Smith, A. N. , & Williams, A. D. (2020). Anti‐racist actions and accountability: Not more empty promises. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(7), 775–786. 10.1108/EDI-06-2020-0158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. , Alabi, B. , Huynh, V. , & Masten, C. (2011). Ethnicity and gender in late childhood and early adolescence: Group identity and awareness of bias. Developmental Psychology, 47, 463–471. 10.1037/a0021819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causadias, J. M. , Vitriol, J. A. , & Atkin, A. L. (2018). Do we overemphasize the role of culture in the behavior of racial/ethnic minorities? Evidence of a cultural (mis) attribution bias in American psychology. American Psychologist, 73(3), 243–255. 10.1037/amp0000099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross, W. E. (1971). The negro‐to‐black conversion experience. Black World, 20(9), 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dass‐Brailsford, P. (2007). Racial identity change among White graduate students. Journal of Transformative Education, 5(1), 59–78. 10.1177/1541344607299210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer, M. A. , Rapa, L. J. , Park, C. J. , & Perry, J. C. (2017). Development and validation of the critical consciousness scale. Youth & Society, 49(4), 461–483. 10.1177/0044118X14538289 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dottolo, A. L. , & Kaschak, E. (2015). Whiteness and white privilege. Women & Therapy, 38(3–4), 179–184. 10.1080/02703149.2015.1059178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dottolo, A. L. , & Stewart, A. J. (2013). “I never think about my race”: Psychological features of White racial identities. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 10(1), 102–117. 10.1080/14780887.2011.586449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, J. F. , Love, A. , Schellhaas, F. M. H. , & Hewstone, M. (2017). Reducing intergroup bias through intergroup contact: Twenty years of progress and future directions. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(5), 606–620. 10.1177/1368430217712052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dupree, C. H. , & Kraus, M. W. (2021). Psychological science is not race neutral. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 270–275. 10.1177/1745691620979820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin, J. R. (2020). The White racial frame: Centuries of racial framing and counter‐framing (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin, J. R. , & Ducey, K. (2019). Racist America: Roots, current realities, and future reparations (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, G. M. , Eales, L. , Gillespie, S. , & Leneman, K. (2021). The Whiteness pandemic behind the racism pandemic: Familial Whiteness socialization in Minneapolis following #GeorgeFloyd’s murder. American Psychologist. 10.1037/amp0000874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey, W. H. (2020, March 23). Even as metropolitan areas diversify, white Americans still live in mostly white neighborhoods. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/even‐as‐metropolitan‐areas‐diversify‐white‐americans‐still‐live‐in‐mostly‐white‐neighborhoods/ [Google Scholar]

- Galliher, R. V. , McLean, K. C. , & Syed, M. (2017). An integrated developmental model for studying identity content in context. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2011–2022. 10.1037/dev0000299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia‐Coll, C. , Crnic, K. , Lamberty, G. , Wasik, B. H. , Jenkins, R. , García, H. V. , & McAdoo, H. P. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlen, J. C. (2018). Interrogating innocence: “Childhood” as exclusionary social practice. Childhood, 26(1), 54–67. 10.1177/0907568218811484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A. W. (2017, October 25). Many minority students go to schools where at least half of their peers are their race or ethnicity. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact‐tank/2017/10/25/many‐minority‐students‐go‐to‐schools‐where‐at‐least‐half‐of‐their‐peers‐are‐their‐race‐or‐ethnicity/ [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, J. M. , & Charmaraman, L. (2009). Race, context, and privilege: White adolescents' explanations of racial‐ethnic centrality. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(2), 139–152. 10.1007/s10964-008-9330-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzanka, P. R. , Frantell, K. A. , & Fassinger, R. E. (2020). The White Racial Affect Scale (WRAS): A measure of White guilt, shame, and negation. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(1), 47–77. 10.1177/0011000019878808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, R. V. (1998). Even the rat was white: A historical view of psychology (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman, M. A. (2018). White kids: Growing up with privilege in a racially divided America. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, D. G. , Bayne, H. B. , Gay, J. L. , McNiece, Z. P. , & Park, C. (2021). A systematic review of whiteness assessment properties and assumptions: Implications for counselor training and research. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 1–17. 10.1080/21501378.2021.1891877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hays, D. G. , Chang, C. Y. , & Decker, S. L. (2007). Initial development and psychometric data for the privilege and oppression inventory. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 40(2), 66–79. 10.1080/07481756.2007.11909806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelbaker, T. , Brown, C. S. , Nenadal, L. , & Mistry, R. S. (2022). Fostering anti‐racism in white children and youth: Development within contexts. American Psychologist. 10.1037/amp0000948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. E. (1984). Toward a theoretical explanation of the effects of race on counseling a Black and White Model. The Counseling Psychologist, 12, 153–165. 10.1177/0011000084124013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. E. (1990). Black and White racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. E. (1993). I also said, "White racial identity influences White researchers". The Counseling Psychologist, 21(2), 240–243. 10.1177/0011000093212007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. E. (1996). Toward a methodology for measuring and assessing “racial” as distinguished from “ethnic” identity. In Sodowsky G. R., & Impara J. (Eds.), Multicultural assessment in counseling and clinical psychology (pp. 143–192). Buros Institute of Mental Measurements. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. E. (2007). Some better practices for measuring racial and ethnic identity constructs. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 235. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. E. (2017). The challenge of making Whiteness visible: Reactions to four Whiteness articles. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(5), 717–726. 10.1177/0011000017718943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. E. (2020). A race is a nice thing to have (3rd ed.). Cognella. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. E. , & Talleyrand, R. M. (1997). Race is not ethnicity. American Psychologist, 52, 1246–1247. 10.1037/0003-066X.52.11.1246 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. (1992). Representing whiteness in the black imagination. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hornsey, M. J. (2008). Social identity theory and self‐categorization theory: A historical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 204–222. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudley, C. , & Irving, M. (2012). Ethnic and racial identity in childhood and adolescence. In Harris K. R., Graham S., Urdan T., Graham S., Royer J. M., & Zeidner M. (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook, Vol 2: Individual differences and cultural and contextual factors (pp. 267–292). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/13274-011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. , Rivas, D. , Foust, M. , Hagelskamp, C. , Gersick, S. , & Way, N. (2008). How to catch a moonbeam: A mixed‐methods approach to understanding ethnic socialization processes in ethnically diverse families. In Quintana S. M., & McKown C. (Eds.), Handbook of Race, Racism, and the Developing Child, (pp. 226–277). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. One World. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, E. D. , Lowery, B. S. , Chow, R. M. , & Unzueta, M. M. (2014). Deny, distance, or dismantle? How white Americans manage a privileged identity. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(6), 594–609. 10.1177/1745691614554658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, E. D. , & Peng, K. (2005). White selves: Conceptualizing and measuring a dominant‐group identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 223. 10.1037/0022-3514.89.2.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornbluh, M. , Rogers, L. O. , & Williams, J. (2021). Doing anti‐racist scholarship with adolescents: Empirical examples and lessons learned. In L. O. Rogers, J. Lee Williams, & M. Kornbluh (Eds.), Special Issue: “Critical approaches to adolescent development: Reflections on theories and methods for pursuing anti‐racist developmental science.” Journal of Adolescent Research, 36(5), 427–436. 10.1177/07435584211031450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesko, N. (2012). Act your age: A cultural construction of adolescence. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Loyd, A. B. , & Gaither, S. E. (2018). Racial/ethnic socialization for White youth: What we know and future directions. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 59, 54–64. 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malott, K. M. , Paone, T. R. , Schaefle, S. , Cates, J. , & Haizlip, B. (2015). Expanding White racial identity theory: A qualitative investigation of Whites engaged in antiracist action. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(3), 333–343. 10.1002/jcad.12031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, K. C. , & Riggs, A. E. (2022). No age differences? No problem. Infant and Child Development, 31(1), e2261. 10.1002/icd.2261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, U. , Rogers, L. O. , & Dastrup, K. R. H. (2021). Beyond ethnicity: Applying Helms's White Racial Identity Development model among white youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 10.1111/jora.12645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville, H. A. , Awad, G. H. , Brooks, J. E. , Flores, M. P. , & Bluemel, J. (2013). Color‐blind racial ideology: Theory, training, and measurement implications in psychology. American Psychologist, 68(6), 455. 10.1037/a0033282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauker, K. , Apfelbaum, E. P. , & Spitzer, B. (2015). When societal norms and social identity collide: The race talk dilemma for racial minority children. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(8), 887–895. 10.1177/1948550615598379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, P. (2002). Shades of white. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, S. P. , Skinner, A. L. , & Abaied, J. L. (2019). Bias awareness predicts color conscious racial socialization methods among White parents. Journal of Social Issues, 75, 1035–1056. 10.1111/josi.12348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J. S. (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. 10.1177/074355489272003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, J. S. (1996). When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean? American Psychologist, 51(9), 918. 10.1037/0003-066X.51.9.918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Priest, N. , Walton, J. , White, F. , Kowal, E. , Baker, A. , & Paradies, Y. (2014). Understanding the complexities of ethnic‐racial socialization processes for both minority and majority groups: A 30‐year systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 43, 139–155. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana, S. M. (1998). Children's developmental understanding of ethnicity and race. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 7, 27–45. 10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80020-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana, S. M. (2007). Racial perspective taking ability: Developmental, theoretical, and empirical trends. In Quintana S., & Clark M. (Eds.), Handbook of race, racism, and the developing child (pp. 16–36). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas‐Drake, D. , Syed, M. , Umaña‐Taylor, A. , Markstrom, C. , French, S. , Schwartz, S. J. , & Lee, R. (2014). Feeling good, happy, and proud: A meta‐analysis of positive ethnic–racial affect and adjustment. Child Development, 85, 77–102. 10.1111/cdev.12175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas‐Drake, D. , & Umaña‐Taylor, A. (2019). Below the surface. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. O. , Bareket‐Shavit, C. , Dollins, F. A. , Goldie, P. D. , & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: Trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1295–1309. 10.1177/1745691620927709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, L. O. (2018). Who am I, who are we? Erikson and a transactional approach to identity research. Identity, 18, 284–294. 10.1080/15283488.2018.1523728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, L. O. (2019). Commentary on economic inequality: “What” and “who” constitutes research on social inequality in developmental science? Developmental Psychology, 55(3), 586–591. 10.1037/dev0000640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, L. O. , & Meltzoff, A. (2017). Is gender more important and meaningful than race? An analysis of racial and gender identity among Black, White, and mixed‐race children. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(3), 323. 10.1037/cdp0000125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, L. O. , Moffitt, U. , & Foo, C. (2021). “Martin Luther King fixed it”: Children making sense of racial identity in a colorblind society. Child Development, 92(5), 1817–1835. 10.1111/cdev.13628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, L. O. , Moffitt, U. , & Jones, C. (2021). Listening for culture: Using interviews to understand identity in context. In McLean K. C. (Ed.), Cultural methodologies in psychology: Capturing and transforming cultures. (pp. 45–75). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, L. O. , Niwa, E. Y. , Chung, K. , Yip, T. , & Chae, D. (2021). M(ai)cro: Centering the macrosystem in human development. Human Development, 65(5–6), 270–292. 10.1159/000519630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, L. O. , & Way, N. (2021). Child development in ideological context: Through the lens of resistance and accommodation. Child Development Perspectives, 15, 242–248. 10.1111/cdep.12433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, W. (2006). White racial identity: Science, faith, and pseudoscience. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 34(4), 235–243. 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2006.tb00042.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, W. , Bennett, S. K. , & Atkinson, D. R. (1994). White racial identity models: A critique and alternative proposal. The Counseling Psychologist, 22, 129–146. 10.1177/0011000094221009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salter, P. , & Adams, G. (2013). Toward a critical race psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(11), 781–793. 10.1111/spc3.12068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salter, P. S. , Adams, G. , & Perez, M. J. (2017). Racism in the structure of everyday worlds: A cultural‐psychological perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(3), 150–155. 10.1177/0963721417724239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schooley, R. , Lee, D. L. , & Spanierman, L. B. (2019). Measuring Whiteness: A systematic review of instruments and call to action. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(4), 530–565. 10.1177/0011000019883261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, E. K. , Gee, G. C. , Neblett, E. , & Spanierman, L. (2018). New directions for racial discrimination research as inspired by the integrative model. American Psychologist, 73(6), 768–780. 10.1037/amp0000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, R. M. (1993). A call to arms for researchers studying racial identity. Journal of Black Psychology, 19(3), 327–332. 10.1177/00957984930193008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, R. M. , Smith, M. A. , Shelton, J. N. , Rowley, S. A. , & Chavous, T. M. (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 18–39. 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner‐Dorkenoo, A. L. , Sarmal, A. , André, C. J. , & Rogbeer, K. G. (2021). How microaggressions reinforce and perpetuate systemic racism in the United States. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(5), 903–925. 10.1177/17456916211002543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek, M. R. , Umaña‐Taylor, A. J. , McDermott, E. R. , Rivas‐Drake, D. , & Martinez‐Fuentes, S. (2020). Testing invariance of ethnic‐racial discrimination and identity measures for adolescents across ethnic‐racial groups and contexts. Psychological Assessment, 32, 509–526. 10.1037/pas0000805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman, L. B. , & Cabrera, N. L. (2014). Emotions of white racism. In Watson V., Howard‐Wagner D., & Spanierman L. B. (Eds.), Unveiling whiteness in the twenty‐first century: Global manifestations, transdisciplinary interventions (pp. 345–357). Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman, L. B. , & Heppner, M. J. (2004). Psychosocial costs of racism to whites scale (PCRW): Construction and initial validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(2), 249. 10.1037/0022-0167.51.2.249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman, L. B. , Poteat, V. P. , Whittaker, V. A. , Schlosser, L. Z. , & Arévalo Avalos, M. R. (2017). Allies for life? Lessons from White scholars of multicultural psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(5), 618–650. 10.1177/0011000017719459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman, L. B. , & Soble, J. R. (2010). Understanding Whiteness: Previous approaches and possible directions in the study of White racial attitudes and identity. In Ponterotto J. G., Casas J. F., Suzuki L. A., & Alexander C. M. (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 283–299). Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, M. B. (2006). Phenomenology and ecological systems theory: Development of diverse groups. In Lerner R. M., & Damon W. (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 829–893). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, M. B. (2017). Privilege and critical race perspectives' intersectional contributions to a systems theory of human development. In Budwig N., Turiel E., & Zelazo P. D. (Eds.), New perspectives on human development (pp. 287–312). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9781316282755.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, M. B. (2021). Acknowledging bias and pursuing protections to support anti‐racist developmental science: Critical contributions of phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory. Journal of Adolescent Research, 36(6), 569–583. 10.1177/07435584211045129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sue, D. W. (2006). The invisible whiteness of being: Whiteness, white supremacy, white privilege, and racism. In Constantine M. G., & Sue D. W. (Eds.), Addressing racism: Facilitating cultural competence in mental health and educational settings (pp. 15–30). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, J. N. , Eberhardt, J. L. , & Roberts, S. O. (2021). Conversations about race in Black and White US families: Before and after George Floyd’s death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(38), e2106366118. 10.1073/pnas.2106366118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed, M. (2021). The logic of microaggressions assumes a racist society. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/4ka37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed, M. , & Juang, L. P. (2014). Ethnic identity, identity coherence, and psychological functioning: Testing basic assumptions of the developmental model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 176–190. 10.1037/a0035330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum, B. D. (1992). Talking about race, learning about racism: The application of racial identity development theory in the classroom. Harvard Educational Review, 62(1), 1–25. 10.17763/haer.62.1.146k5v980r703023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum, B. D. (2017). Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria? And other conversations about race (2nd ed.). Basic Books. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomann, C. R. , & Suyemoto, K. L. (2018). Developing an antiracist stance: How White youth understand structural racism. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38, 745–771. 10.1177/0272431617692443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña‐Taylor, A. J. , Quintana, S. M. , Lee, R. M. , Cross, W. E. , Rivas‐Drake, D. , Schwartz, S. J. , Syed, M. , Yip, T. , & Seaton, E. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85, 21–39. 10.1111/cdev.12196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña‐Taylor, A. J. , Yazedjian, A. , & Bámaca‐Gómez, M. (2004). Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: an International Journal of Theory and Research, 4, 9–38. 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L. H. M. , & Syed, M. (2013). Integrating identities: Ethnic and academic identities among diverse college students. Teachers College Record, 115(8), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. D. , Byrd, C. M. , Quintana, S. M. , Anicama, C. , Kiang, L. , Umaña‐Taylor, A. J. , Calzada, E. J. , Pabón Gautier, M. , Ejesi, K. , Tuitt, N. R. , Martinez‐Fuentes, S. , White, L. , Marks, A. , Rogers, L. O. , & Whitesell, N. (2020). A lifespan model of ethnic‐racial identity. Research in Human Development, 17(2–3), 99–129. 10.1080/15427609.2020.1831882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston, A. S. (2004). Introduction: Histories of psychology and race. In Winston A. S. (Ed.), Defining difference: Race and racism in the history of psychology (pp. 3–18). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10625-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yee, A. H. , Fairchild, H. H. , Weizmann, F. , & Wyatt, G. E. (1993). Addressing psychology's problem with race. American Psychologist, 48, 1132–1140. 10.1037/0003-066X.48.11.1132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]