Abstract

Aim

Scientific evidence underpins dietetics practice; however, evidence of how the therapeutic relationship influences outcomes is limited. This integrative review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the topic of the therapeutic relationship between clients and dietitians in the individual counselling context by summarising empirical literature into qualitative themes.

Methods

An electronic literature search of the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsychInfo, Scopus and Web of Science databases was conducted in October 2018 and repeated in February 2021. Studies were included if they explicitly referred to the therapeutic relationship (or associated terms), were based on study data and available in full text. Extracted data were checked by a second researcher and the methodological quality was evaluated independently by two researchers using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. An iterative process of qualitatively coding, categorising and comparing data to examine recurring themes was applied.

Results

Seventy‐six studies met the inclusion criteria. Five themes were identified which showed the extent and nature of research in this area. Studies revealed the therapeutic relationship: (i) is valued within clinical dietetic practice, (ii) involves complex and multifactorial interactions, (iii) is perceived as having a positive influence, (iv) requires skills training and (v) is embedded in practice models and tools.

Conclusion

Studies show the therapeutic relationship is a valued and multifactorial component of clinical dietetic practice and is perceived to positively influence the client and dietitian. Observational data are needed to assess the extent to which the strength of the therapeutic relationship might contribute to clients' health outcomes.

Keywords: systematic review, patient‐centered care, professional‐patient relations, qualitative research, therapeutic relationship

1. INTRODUCTION

Dietetics is an evidence‐based profession where peer‐reviewed, scientific research underpins practice. The International Confederation of Dietetic Associations describes evidence‐based practice as a skill for dietitians to guide their decision‐making. They describe dietitians having to combine an assessment of how valid, applicable and important evidence is with their own expertise and the client's values and circumstances. 1 Hence, an evidence‐based approach requires critical skills of the dietitian in understanding, evaluating and applying scientific knowledge in a meaningful way for the client. In Australia, dietitians are required to practise within an evidence‐based approach as outlined by the Statement of Ethical Practice 2 and National Competency Standards, 3 a requirement that is supported by the International Code of Good Practice published by the International Confederation of Dietetic Associations. 4 Thus, practising in a way that is built upon credible, scientific evidence is fundamental to the dietetic profession. This evidence should also relate to how effective practice is conducted, including consideration of the therapeutic relationship with clients.

Although governing documents depict the therapeutic relationship as crucial for clinical dietetic practice, comprehensive descriptions of its key components are scarce. 3 , 5 For example, the competency standards for dietitians in Australia state dietitians must ‘build an effective relationship’ with little articulation of what an effective relationship might look like. 3 In earlier research, the authors have shown that meaningful therapeutic relationship development is a complex and multi‐faceted process. 6 However, prior to this, many studies simply identified stand‐alone qualities (such as ‘trust’) as important for relationship development without detailed descriptions of the process of meaningful relationship development as a whole. 7 , 8 , 9 The limited descriptions of important relationship components may in part be due to the heavy influence of biomedical and nutritional sciences as sources of evidence for practice. A qualitative study that explored dietitians' perceptions of evidence‐based practice reported that dietitians did not perceive knowledge about communication skills to be ‘evidence‐based’. 10 In contrast to biomedical and nutritional information, dietitians did not feel they needed to retrieve information from the scientific literature to understand the evidence‐base around communication skills. These skills were instead considered as ‘know‐how’, gained through professional development opportunities rather than scientific literature. 10 The therapeutic relationship is integral to communication and counselling practices, as they are pivotal to how effectively the client and dietitian engage and are able to work together. 11 However, these findings suggest dietitians may also not consider knowledge and skills in the development of therapeutic relationships as part of the ‘evidence‐based’ reference framework. This suggests a need for more scientific knowledge of therapeutic relationships, particularly as it can indeed provide evidence that informs practice.

Exploratory research may be required in the first instance. Integrative literature reviews are appropriate as they can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a specific healthcare phenomenon by summarising relevant literature and allowing various methodologies to be included. 12 Integrative reviews on therapeutic relationships can be found in other disciplines such as nursing, physiotherapy and occupational therapy, but are limited in dietetics. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 One integrative review of published studies from 1997 to 2016, focused on patient‐centred care in dietetics. 18 It highlighted the significance of the therapeutic relationship and noted this relationship as an important dimension in delivering patient‐centred healthcare. Although patient‐centred care and the therapeutic relationship are related concepts, the integrative review on patient‐centred care did not comprehensively focus on the therapeutic relationship. The inclusion criteria specified ‘relationship’ only and did not include other terms known to represent the phenomenon of the therapeutic relationship, for example, ‘alliance’, ‘connection’ and ‘rapport’. Dietetic students were also excluded and hence the review on patient‐centred care did not capture literature describing how students might be trained in therapeutic relationship development. There remains a need to review research that comprehensively focuses on the concept of the therapeutic relationship (including other like terms), particularly those published prior to 1997 and since 2016.

The integrative review reported here addresses the broad question ‘What does research on the therapeutic relationship tell us about the phenomenon in clinical dietetic practice?’. The aim of this study was to provide a comprehensive overview of the topic of the therapeutic relationship between clients and dietitians in the individual counselling context by summarising empirical literature into qualitative themes. The term ‘therapeutic relationship’ is widely used across healthcare literature and hence is used throughout to refer to the purposeful relationship between a client and dietitian for the client's therapeutic benefit. 19 ‘Therapeutic alliance’ is also used, as it is a term used within the psychology discipline that refers to a component of the therapeutic relationship. 20

2. METHODS

This integrative review was written in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 21 The integrative review methodology was guided by the work of Whittemore and Knafl who specify five key stages: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and data presentation. 12 The approach has been applied previously by Sladdin et al. in a study of patient‐centred care in the dietetic context. 18

A systematic electronic literature search was conducted in October 2018 and repeated in February 2021 to account for studies published after the original search date. The terms ‘dietitian’, ‘client’ and ‘relationship’ were used as a foundation to identify other relevant search terms. To ensure a comprehensive list of terms was achieved a health sciences librarian was consulted and the online version of the Oxford thesaurus was used in addition to the first author's knowledge of terminology expressed in the literature. 22 Medical subject headings (MeSH) were also utilised to ensure key terms were included and truncated appropriately, for example, searching for ‘relation*’ rather than ‘relationship’. Search terms corresponding to the dietitian and client included: ‘dietitian’, ‘dietician’, ‘nutritionist’, ‘client’ and ‘patient’. Search terms corresponding to ‘relationship’ included: ‘relation*’, ‘alliance’, ‘partner*’, ‘collaborat*’, ‘connect*’, ‘rapport’, ‘bond*’ and ‘interaction*’. Boolean connectors ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ were used. Four electronic databases were searched: Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsychInfo, Scopus and Web of Science. Research shows electronic database searches may yield only half of the eligible studies and therefore other strategies were applied, including ancestry searching and hand searching of key dietetic journals. 23 Google Scholar and Scopus databases were used to attain articles identified through ancestry and hand searching. All citations obtained through searching were imported into EndNote for data management purposes. 24

One researcher screened the titles and abstracts of articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were included if they: (i) explicitly referred to the relationship, alliance, partnership, collaboration, connection, rapport, bond or interaction between a client and dietitian, nutritionist or nutrition and/or dietetic student concerning the study being reported, (ii) were empirical (that is based on data collected for a study), and (iii) were available as full text. Studies were excluded if they referred to the relationship (as outlined in the inclusion criteria above) but only with regard to group‐based interventions, or described a multidisciplinary context but it was unclear if the relationship was between a client and dietitian, nutritionist or nutrition and/or dietetic student specifically. No exclusion criteria for study language or year was applied to maximise the opportunity for relevant data to be captured. English translations of the full‐text version of published articles were requested from authors via email. Articles were obtained and each full‐text article was read by the researcher to determine if they met the inclusion criteria.

Data were systematically extracted into a Microsoft Excel 25 table that included study authors, year and country, study design and aim, inclusion criteria, sample, data collection and analysis methods and findings concerning the therapeutic relationship or associated terms. One researcher extracted all data which were checked by a second researcher using a method for source data verification (that is comparing original documents to recorded data). 26 The percentage of errors identified was within the acceptable error rate (≤5%) meaning no further checking of data was required. 26

The methodological quality of each study identified in the initial search was independently scored by two researchers using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). This was performed due to the subjectivity of the MMAT. 27 Researchers discussed differences between scores and an agreed score was decided. Justification for the agreed scores was documented and used to score studies identified in the repeated search.

Following processes outlined by Whittemore and Knafl, the data were ‘ordered, coded, categorised and summarised’ by one researcher and refined through discussions with the interdisciplinary research team (dietetics and psychology). 12 Initially, studies were ordered according to whether they referred to the ‘relationship’ or ‘alliance’, or associated terms such as ‘connection’. Data concerning the terms ‘relationship’ and ‘alliance’ were analysed together because both are established terms in the psychology discipline with evidence‐based constructs (e.g., psychologist Bordin's ‘working alliance’). 20 These terms were initially analysed separately from other terms in anticipation of a possible difference in findings given their link to evidence‐based constructs. Data were then ordered according to study design (either qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods or literature reviews).

Whittemore and Knafl suggest applying the constant comparative method particularly for analysing data from different methodologies. 12 All extracted data were copied directly from the data extraction table for coding by one researcher. Data concerning the relationship and alliance were coded first, followed by data concerning associated terms. The coding process began with assigning initial codes, which were codes that described evidence in the data extract for either ‘relationship’, ‘alliance’ or associated terms. These codes were then compared, where similarities between codes were identified and consequently grouped together to form common themes. 12 This process involved re‐reading codes and adjusting preliminary themes to ensure the themes reflected the codes. Once themes were developed for data within each study design, they were then compared across study designs and merged where similarities were seen (e.g., quantitative and qualitative data showing the relationship is important). Data were collated across study designs to reflect merged themes. 12 This process occurred separately as part of the analyses for both primary terms (‘relationship’ and ‘alliance’) and associated terms (e.g., ‘connection’).

Established themes within both primary and associated terms analyses were compared, with similarities and differences documented. These notes allowed identification of major themes across both analyses, and where appropriate these were adapted to reflect data from both analyses. Following this, data were collated and findings were reviewed to confirm each theme. The final phase of the analysis involved drafting a summation of each theme where its meaning was further crystallised. 12 Meetings were also held with the interdisciplinary research team where the emerging analysis was discussed, critiqued and refined. This team consisted of researchers from both dietetics and psychology and allowed for themes that were developed from a dietetics lens to be challenged from a psychology perspective. Additional notes were kept by the researcher to document the emerging analysis, analytical decisions and possible directions for further analysis. 12

3. RESULTS

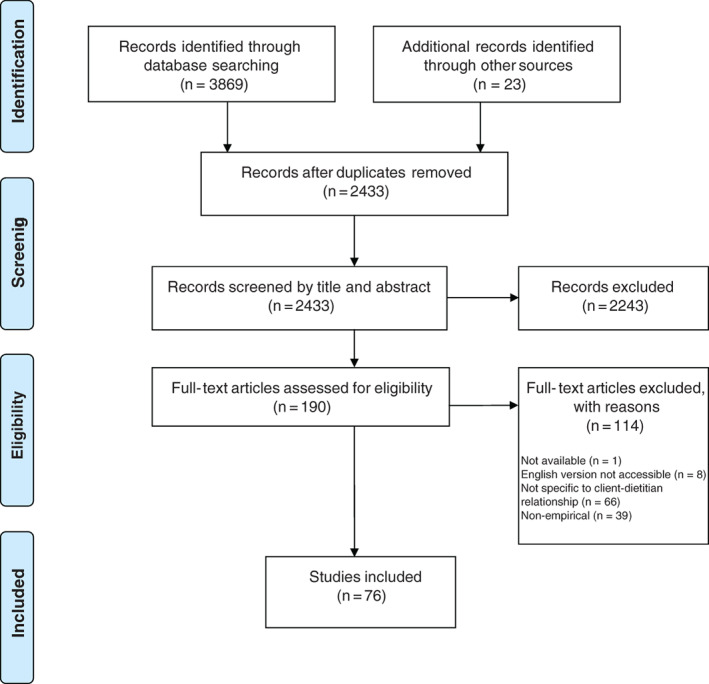

From 2433 studies identified for screening, 76 studies were included (Figure 1). Most quantitative studies were descriptive, and predominantly utilised surveys (n = 21) and ratings of observed practice (n = 7). One study involved a secondary analysis of control and intervention data from a randomised controlled trial. Qualitative study designs mostly utilised interviews (n = 26) and focus groups (n = 9). Most studies were conducted in Australia (n = 27) or the USA (n = 18), and published between 2010 and 2020 (n = 50). Most studies had between 11 and 395 participants (n = 66) which included dietitians or nutritionists (n = 47), clients or patients, and their family or carer (n = 25), or nutrition and dietetic students (n = 11). Dietitians in the studies were working in private practice (n = 12), hospitals and outpatient clinics (n = 13) and community or public health services (n = 6). From the studies that articulated the health conditions of clients, most were described as managing chronic diseases (n = 14). A summary of included studies is provided in Table 1. Studies varied in their methodological quality (Table 2). The number of studies that fulfilled all five design‐specific criteria in the MMAT was 31 (of 76 eligible studies), with most being qualitative (n = 25).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses) flow diagram showing the selection of included studies for the integrative literature review (combined results from all searches)

TABLE 1.

Summary of included studies with key findings referring to primary terms (‘relationship’ or ‘alliance’) and associated terms (e.g., connection) in alphabetical order by first author

| Author, Country | Design | Participants, sample size | Study aim/s | MMAT a | Key findings related to primary terms | Key findings related to associated terms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ash et al., 28 Australia | Qualitative: interviews and guided discussions (secondary analysis) |

Dietitians (1991 interviews n = 26) (1998 interviews n = 23) (2007 interviews n = 19) Dietitians and employers (2014 guided discussions n = 7) |

To explore how a competency‐based education framework influenced competency standards and their application and how this influenced dietetic practice in Australia since 1990 | ***** | Communicating for better care, as part of the therapeutic relationship, remained a central dietetic role (throughout dietetic competency standards in Australia) | Communication skills of dietitians have evolved from educating clients to negotiating with clients. Competency standards have reflected this change, from ‘Interprets and translates nutrition information’ (1993 competency standards) to ‘Collaborates broadly with clients…’ (2015 competency standards) |

| Ball et al., 7 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone) | Clients (n = 10) | To explore the nutrition care needs of newly diagnosed patients over time, as well as their views on how dietitians can best support the long‐term maintenance of dietary change | ***** | Clients value genuine relationships few participants perceive an ongoing relationship with their dietitian to be useful. The importance of the dietitian treating the patient as a person for the relationship | |

| Brody et al., 29 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: Delphi | Dietitians (n = 73) | To describe the practice activities performed by clinical advanced practice registered dietitian nutritionists that reached consensus using the Delphi technique | *** | Dietitians reached a consensus on ‘establishing trust and rapport’ being an essential component of advanced dietetic practice | |

| Brown et al., 30 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (paper) | Dietitians (n = 395) |

1. To identify the motivational strategies used most often by dietitians when counselling individuals with diabetes mellitus 2. To determine those strategies that dietitians perceive as being most effective 3. To identify barriers perceived by dietitians as being the most significant obstructions to dietary adherence experienced by individuals with diabetes 4. To explore the effect of various demographic variables such as level of education, years of experience, setting of practice, and certification as a diabetes educator on the use of motivational strategies |

**** | Identification of effective strategies for establishing a comfortable relationship with client: using positive external motivators, individualising recommendations and exhibiting organisational management of content | The rapport between a patient and dietitian was not identified as a barrier to dietary adherence for patients managing diabetes |

| Buttenshaw et al., 31 Australia | Quantitative—descriptive: survey |

Dietitians (n = 185) (Study 1) Dietitians (n = 458) (Study 2) |

To develop a reliable instrument to measure generalist dietitians' confidence about working with clients experiencing psychological issues | *** | ‘Build rapport’ was included in the initial confidence scale, however, it was not included in the final scale | |

| Cairns and Milne, 32 Canada | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (mail) | Dietitians (n = 65) | To determine what counselling strategies are being used and identify the educational needs of registered dietitians who work with clients with eating disorders in Canada | *** | ‘Rapport building’ was identified as a common type of strategy used by dietitians. Some dietitians (10% of sample) did not want more training in rapport‐building strategies, with the most common reason being they felt well‐trained in this skill already. The following strategies were listed as rapport‐building strategies: reflective listening, attending to non‐verbal communication, person‐centred approach, humour, immediacy, socratic interview style, self‐disclosure | |

| Cant and Aroni, 33 Australia | Mixed methods: survey (online) | Dietitians (n = 258) | To critically examine practising dietitians' experiences and perceptions of their roles in education of individual clients, both in applying entry level communication skills, and in progressive skill development | *** | Dietitians aim to develop a working alliance with their clients as desired in more collaborative relationships | Dietitians who were trained 30 years before the study date commented on the transition in practice from educating clients, to more modern practice utilising a partnership with the client and skills in nutrition counselling |

| Cant and Aroni, 11 Australia | Mixed methods: focus groups and semi‐structured interviews (face‐to‐face or telephone) (Phase 1) and survey (online) (Phase 2) |

Dietitians (n = 46) clients (n = 34) (Phase 1) Dietitians (n = 258) (Phase 2) |

To examine perceptions of both dietitians and their patients about dietitians' skills and attributes required for nutrition education and individuals | ***** | Understanding the results of the study (as a guide to communication practice) might help enhance dietitian‐patient relations | ‘Partnership’ and ‘collaboration’ identified as part of interpersonal and communication skills in a model of professional performance in communication. Results suggest that collaboration is required in the professional competencies of dietitians in the 21st century |

| Cant and Aroni, 34 Australia | Mixed methods: focus groups and semi‐structured interviews (face‐to‐face or telephone) (Phase 1) and survey (online) (Phase 2) |

Dietitians (n = 46) clients (n = 34) (Phase 1) Dietitians (n = 258) (Phase 2) |

To examine dietitians' perceptions of process in education of individual clients and to validate performance criteria for dietitians' nutrition education and counselling of individuals | ***** | ‘Counselling’ used by 93% of dietitians (where counselling was described as the use of a relationship to problem‐solve with clients). ‘Relationship‐building skills’ identified as the first step of nutrition education in developed model. ‘Relationship‐building skills’ defined as ‘develop rapport through introductions, informality, verbal, non‐verbal communication and own presence’ model for nutrition education suggesting dietitians build a relationship through developing rapport ‘Communication skills’ identified as underpinning nutrition counselling practice, and defined as ‘applies advanced communication skills to counselling to develop a professional relationship with clients' (where client's own experiences and knowledge are central and carry authority within the relationship). |

‘Rapport’ was included in the definition of the first step of the nutrition education model, ‘relationship‐building skills’. The definition read ‘develop rapport through introductions, informality, verbal, non‐verbal communication, own presence’. The developed model suggests dietitians build a relationship with clients through developing rapport ‘Collaboration skill’ was identified as a second step of the developed model, and was partly defined as aiming ‘for partnership with client to problem solve’ The developed model describes collaboration and partnership within a nutrition education and counselling consultation with individual clients |

| Cant, 8 Australia | Qualitative: focus groups and semi‐structured interviews (face‐to‐face or telephone) |

Dietitians (n = 46) Clients (n = 34) |

To explore dietitians' and clients' perceptions of trust and to develop a model to explain trustworthiness and professionalism in a health care setting | ***** |

Dietitians desire to build relationships with patients Building relationships assist the development of the patients' trust Dietitians perceive their own integrity as important in building relationships with patients Dietitians perceive the relationship as depending on openness and the client's assessment of their trustworthiness Use of self‐disclosure by the dietitian enhances the depth of the relationship Emphasis on the need to keep the relationship ‘professional’ Developed model of trust showing trust as being affected by the relationship |

Dietitians aimed to build rapport to gain the trust and respect of the client Clients viewed a desirable communication style as enabling a positive partnership Clients portrayed collaborative partnerships with their dietitian ‘Collaboration’ was included as part of ‘professionals’ verbal and non‐verbal communication’ within the developed model of trust |

| Cant, 35 Australia | Mixed Methods: Focus groups and semi‐structured interviews (face‐to‐face or telephone) (Phase 1) and survey (online) (Phase 2) |

Dietitians (n = 46) clients (n = 34) (Phase 1) Dietitians (n = 258) (Phase 2) |

This study focuses on the dress style of dietitians as part of the verbal and/or nonverbal communications within individual client consultations. The study aimed to describe how dietitians and their clients interpret this dialogue and to explore the implications for practice. | ***** | There was agreement that professionals' dress formed a nonverbal communication relevant to their relationship, however, there was no evidence that this applied universally | |

| Cant, 36 Australia | Mixed methods: survey | Dietitians (n = 365) | To explore patterns of delivery of dietetic care for patients referred under medicare chronic disease management | **** | Dietitians reported allocating patients longer consultation times (predominantly for initial consultations) to build rapport | |

| Chapman et al., 37 Canada | Qualitative: focus groups | Dietitians (n = 104) | To describe Canadian dietitians' approaches to counselling adults seeking weight‐management advice, including how dietitians' approaches differ between clients with and without associated risk factors and long histories of dieting | ** | Dietitians described their strategy of explaining their approach to clients (when perceived to be misaligned with clients' goals) and enabling clients to decide if they wished to continue the counselling relationship | |

| Cotugna and Vickery, 38 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: food diary and survey | Students (n = 11) | To examine the attempted compliance of 11 student dietitians who were assigned to follow calorie‐controlled diabetic diets for 1 week | ** | Students perceived the experience of attempting to comply with a diabetic diet as helping them to demonstrate empathy and build more effective relationships | |

| Danish et al., 39 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: ratings of observed practice | Students (n = 29) | To develop a model whereby the anatomy of a typical dietetic counselling interview can be assessed | * | The length of the ‘relationship‐establishing phase’ (versus ‘problem‐solving phase’) varied among counsellors and interviews |

In developing rapport, the dietitian being able to demonstrate ‘continuing responses’ when engaging with the client is crucial. Results indicated that few verbal responses which facilitate rapport development were used by students in interviews A suggestion was made that the length of the ‘relationship‐establishing phase’ (5 min) would not be sufficient to develop rapport and trust |

| Devine et al., 40 USA | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (face‐to‐face or telephone) | Dietitians and nutrition practitioners (n = 24) | To understand dietetics and nutrition professionals' experiences of their practice roles | ***** | Dietitians perceived clients' unrealistic expectations as having the potential to interfere with effective therapeutic relationships | |

| Endevelt and Gesser‐Edelsberg, 41 Israel | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews and focus groups |

Clinical dietitians (n = 12) Supervisory dietitians (n = 5) Clients (not specified, n = 12 focus groups) |

To ascertain the role of the dietitian‐patient relationship and the counselling approach in influencing individual patients' decisions to adhere to treatment by continuing or not to adhere by terminating their nutritional treatment | ***** | Relationship described in a ‘counselling and therapeutic approach’, versus an ‘educational and therapeutic approach’, as both parties working together rather than the patient being solely responsible |

The patient‐dietitian interaction has a significant impact on the conception of the dietitian's role The patient‐dietitian interaction influences the patient's response to education counselling and the extent of commitment and adherence to their treatment plan A ‘counselling and therapeutic approach’ to practice was described as enabling a partnership between the dietitian and client There are unique barriers at play in the context of the dietitian‐patient interaction |

| Foley and Houston, 42 Australia | Mixed methods: patient referral and attendance data, focus groups and interviews |

General practitioners (n = 6) Practice nurses (n = 7) Receptionist (n = 1) Patients (n = 13) |

1. To ascertain if changes to dietetic services increased referrals and attendance rates 2. To learn from clinical staff and patients what is important to them in a dietetic service |

* |

Patients mentioned the dietitian taking time to make a personal connection as a factor contributing to them feeling safe with the dietitian Dietitians forming a personal connection with their patients facilitates improved attendance at the clinic |

|

| Gesser‐Edelsberg and Birman, 43 Israel | Qualitative: focus groups and interviews | Dietitians (n = 72) | To ascertain the impact of the physical environment on the dynamics and communication between a dietitian and a client in a meeting, based on perceptions of dietitians | ***** |

Recognising dietetics as a constantly changing field, and as moving towards needing to develop deeper therapeutic relationships Dietitians defining success as creating a relationship that motivates change for client |

Dietitians perceived that a change to the spatial environmental design (according to the dynamic model) might positively impact the therapeutic interaction Dietitians perceived that changes in the physical environment might undermine patients' feeling of wellbeing and unsettle the therapeutic interaction Most dietitians commented that they had not received training in managing the emotional aspects of the therapeutic interaction and there was no permanent or supportive arrangement to do so The concept of the organisation of the space in which the dietitian‐patient interaction occurs is neither taught nor addressed in professional or educational frameworks Most dietitians view their profession as a dynamic therapeutic interaction process |

| Gibson and Davidson, 44 Australia | Quantitative—cross‐ sectional analytical: ratings of observed practice | Students (n = 215) | To explore the impact of a student‐simulated patient interview on the development of communication skills during formative and summative objective structured clinical exams | ***** | ‘Building rapport’ listed as an example of a foundation skill targeted before students undertook simulations | |

| Green et al., 45 Canada | Mixed methods: survey and interview |

Dietitians (n = 135) (Phase 1) Dietitians (n = 17) (Phase 2) |

To explore registered dietitians' perceptions about expressive touch as a means to provide client‐centred care | No criteria met |

Majority of dietitians perceived that the use of expressive touch may enhance the therapeutic relationship Less than 5% disagreed Dietitians working in community health centres, hospitals, and long‐term care reported greater agreement with the statement that expressive touch enhances the therapeutic relationship More opportunities existed for expressive touch in lower acuity environments, where dietitians have a physical layout and practice more conducive to meaningful communication (where the relationship is more likely to develop) Dietitians expressed concern that expressive touch would erode trust in therapeutic relationship Dietitians described positive experiences of using expressive touch, including reducing the power differential in the relationship Dietitians are attempting to navigate the complexities of expressive touch to strengthen relationships with clients |

Dietitians described positive experiences with the use of expressive touch, using different forms of touch to communicate empathic concern, kindness, teamwork and gratitude that facilitated building rapport More opportunities existed for expressive touch in lower acuity environments, where dietitians have a physical layout and practice more conducive to meaningful communication (where rapport is more likely to develop) Dietitians who were less comfortable with touch used other techniques to build rapport |

| Gregory et al., 46 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey and ratings of observed practice | Not applicable | To develop an instrument for evaluating dietitians' interviewing skills | * | ‘Rapport’ was included as a subcategory of interviewing skills within the developed scale, including: Opportunity for client questions/concerns, sensitivity to client concerns, feedback and social support and no undue interruptions | |

| Hancock et al., 47 UK | Qualitative: focus groups and semi‐structured interviews (telephone) |

Clients (n = 6) Dietitians (n = 44) |

To explore qualitatively patients' experiences of dietetic consultations, aiming to achieve a better understanding of their perspectives | ***** |

‘Partnership’ and ‘rapport’ were identified as factors affecting participants' experience of dietetic consultations Patients‐reported treating the consultation as a partnership and an important factor in the effectiveness of the consultation Patients described a good rapport between themselves and the dietitian as essential A lack of rapport with the dietitian was listed as contributing to the client's negative experience of dietetic consultations and impacting their outcome achievement and perceived effectiveness of consultations |

|

| Harper and Maher, 48 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (face‐to‐face or telephone) | Dietitians (n = 11) | To develop an explanatory theory of how dietitians in private practice source, utilise and integrate practice philosophies | ***** |

Dietitians described forming collaborative relationships with clients to nurture change The private practice context compels dietitians to develop mutually beneficial therapeutic relationships with patients Intellectual virtues (episteme, techne and phronesis) are fundamental to how dietitians adapt their strategies for developing therapeutic relationships Dietitians recognise the importance of developing a therapeutic relationship, and identified these relationships as vital to clients' wellbeing and dietitians' livelihoods The need to establish a relationship where the client feels comfortable and engaged, before education or the intervention is delivered, was identified Techniques used to develop the relationship vary, and are dependent on the client and dietitian The relationship as a complex interpersonal experience was recognised |

‘Facilitating client autonomy’ was seen as a necessary part of enhancing rapport Techniques used to build rapport vary according to dietitians and clients Dietitians perceived that facilitating follow‐up visits hinged on establishing a rapport and connection from the first consult Building a rapport was shown to be an important aspect of practice The private practice context provided the motivation to establish a rapport with clients and a rich learning environment in which to foster the skills to do so |

| Harris‐Davis and Haughton, 49 USA | Quantitative—cross‐sectional analytical: survey (paper) | Dietitians (n = 343) | To develop and test a model for multicultural nutrition counselling competencies for registered dietitians | *** | The factor ‘believe that cultural differences do not have to negatively affect communication or counselling relationships’ was included under the broader category of ‘multicultural awareness’ within the multicultural nutrition counselling model | |

| Harvey et al., 50 UK | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (paper) | Dietitians (n = 187) |

1. To assess and compare dietitians' views about overweight and obese people 2. To assess and compare dietitians' reported weight management practice of overweight and obese people 3. To explore the associations between dietitians' views and weight management practices |

** |

Results for the item ‘I (would) make sure I spend time developing a good relationship with clients’: overweight questionnaire mean = 5.09 (SD = 0.93), obese questionnaire mean = 4.95 (SD = 1.21) Dietitians reported spending time developing good relationships with clients Reduced acceptance of obese people was associated with a reduction in time spent developing a good relationship with a client |

|

| Hauenstein et al., 51 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (mail) | Dietitians (n = 194) | To explore dietitians' perceptions of various techniques that are known to affect dietary adherence of patients with type II diabetes | *** |

Shared decision making and individualisation of instruction were described as helping to establish a strong rapport between a dietetic educator and client Revealing one's own efforts and problems in achieving dietary adherence was described as a technique used to help build rapport and support behaviour change |

|

| Horacek et al., 52 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey and ratings of observed practice | Students (n = 99) |

1. To assess dietetic students' and interns' use of skills to apply a lifestyle‐oriented nutrition counselling model 2. To assess if differences exist between their self, client or expert evaluations; or by student type: coordinated program, didactic program in dietetics and dietetic intern |

*** | Interviewing skills are crucial to establishing the collaborative relationship needed for effective counselling |

‘Establishing rapport’ was included in the developed lifestyle‐oriented nutrition counselling model Students (mean = 4.41, SD = 0.44) rated themselves as significantly higher than their supervisor (mean = 4.26, SD = 0.38) (p < 0.01). Students are more confident in their abilities than the experts assessed, indicating room for improvement Students rated their rapport building skills as improving throughout training (pre‐training: mean = 3.36, SD = 1.19, pre‐counselling: mean = 4.01, SD = 0.79, post‐counselling: mean = 4.39, SD = 0.74) (p < 0.001) |

| Isselmann et al., 53 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey and interviews | Participants from variety of nutrition counselling settings (not further specified) (n = 40) | To develop a continuing education workshop in nutrition counselling | No criteria met |

‘Client‐counsellor relationship’ was included in the workshop outline The enhancement of the value of the patient‐counsellor relationship through the application of skills and techniques from psychological models was recognised |

|

| Jager et al., 54 Netherlands | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews | Clients (n = 12) | To explore experiences and views of ethnic minority type 2 diabetes patients regarding a healthy diet and dietetic care in order to generate information that may be used for the development of training for dietitians in culturally competent dietetic care | ***** | Further research was suggested, in that observations of dietetic consultations may provide information on the ‘actual interaction’ between dietitians and clients who are migrants managing type 2 diabetes | |

| Jager et al., 55 Netherlands | Qualitative: interviews | Dietitians (n = 12) | To explore the experiences of dietitians and the knowledge, skills and attitudes they consider to be important for effective dietetic care in migrant patients | ***** |

Trust identified as an important factor in the relationship Dietitians aware that a trusting relationship facilitates information sharing Small gestures that facilitated a warm interaction were identified as important for the relationship Some dietitians found it difficult to build a trusting relationship with migrant patients due to the language barrier and cultural differences Dietitians wanted to learn how to build a trusting relationship and convey information with migrant patients |

|

| Jakobsen et al., 9 Denmark | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews and observations of counselling sessions |

Dietitians (n = 2) Counselling session observations (n = 15) |

To determine whether narrative dietary counselling applied together with motivational interviewing versus motivational interviewing alone is experienced to strengthen the relationship and collaboration between counsellors, and clients with a chronic disease | ** |

Identification of a particular practice approach ‘narrative dietary counselling’ as improving relationship building between a client and dietitian Dietitians perceive trust as the most important, yet challenging, prerequisite of relationship building The use of whiteboards and narrative learning strategies fosters an equal relationship (as part of ‘narrative dietary counselling’ approach) |

Dietitians indicated that using the whiteboard (as part of narrative dietary counselling) strengthened their collaboration with the client Collaboration is both important and challenging in dietary counselling Challenges to collaboration were identified as the clients' expectations of dietary counselling and the dietitian's role, and the presumed private character of food and eating issues Dietitians experienced the narrative approach to dietary counselling to be a powerful tool in collaborating with clients through specific techniques used |

| Jarman et al., 56 Canada | Mixed methods: ratings of observed practice, survey, interviews and focus groups |

Clients (n = 50) Dietitians (intervention: n = 1, control: not specified) |

1. To compare experiences and perceptions of using healthy conversation skills between the intervention and control registered dietitians 2. To compare perceptions of support received from the registered dietitians by intervention and control women, as well as the acceptability of the intervention |

***** |

The intervention dietitian commented that the healthy conversation skills approach was useful for building relationships with participants by exploring and understanding their barriers and solutions to issues they had ‘building relationships’ identified as a theme |

|

| Jones et al., 57 UK | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (face‐to‐face) | Clients (n = 24) | To obtain views of patients attending community dietetic clinics, on the dietetic service, the outcomes of dietary treatment in terms of lifestyle change and the impact that attending the dietitian had on their lives | ***** |

Half of the clients interviewed reported a positive relationship with their dietitian Clients valued ongoing, supportive and positive relationships with their dietitian Clients reported a link between their levels of motivation and their relationship with their dietitian |

|

| Karupaiah et al., 58 Malaysia | Quantitative—cross sectional analytical: ratings of observed practice | Dietetic interns (n = 27) | This article shares the experience at the National University of Malaysia in assimilating the nutrition care process into the dietetics curriculum. A performance evaluation tool was designed by incorporating the key elements of the nutrition care process and was applied to assess dietetic interns' competencies and skills in identified clinical areas. | ** |

A ‘collaborative counsellor‐patient relationship’ was identified as a learning component of the performance evaluation tool Learning attributes and skills were identified: Demonstrating appropriate bedside manner, eye contact and intonation, listening skills and identification of relevant information, involving family members in counselling process, setting priorities for dietary advice and establishing goals for patient, creating individualised plans, providing practical advice, acknowledging and fostering patient's self efficacy |

|

| Knight et al., 59 UK | Quantitative—descriptive: survey | Nutrition and dietetics students (n = 112) | To measure attitudes of student dietitians with respect to communication skills teaching and how experiential learning using simulated patients impacts confidence in their communication skills | ***** |

Almost all students rated communication skills as important for relationships with patients (99.1%) Significant difference in number of students who were very or extremely confident in ‘building and sustaining a trusting relationship with patient’ before and after communication skills teaching |

|

| Lambert et al., 60 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews | Dietitians (n = 27) |

1. To explore the experience of renal dietitians regarding the process of educating patients with end stage kidney disease 2. To describe the strategies they perceived to help patients understand the renal diet to support adherence |

***** |

Dietitians have a strong desire to form a collaborative relationship with their client, as it contributed to their pride and professional satisfaction Dietitians perceived a trusting relationship as important in optimising patients' ability to self‐manage Dietitians perceived empathy as an important enabler of trusting relationships Dietitians described a discrepancy between ‘ideal’ and actual practice in not having adequate time to effectively develop the dietitian‐patient relationship |

Follow‐up phone reviews were perceived by dietitians to be ‘cutting corners’ and detrimental to maintaining rapport Dietitians perceived layering advice helped to preserve rapport and empower patients which facilitated long‐term professional relationships Findings are consistent with previous research confirming the critical role of developing rapport with patients |

| Lambert et al., 61 Australia | Quantitative—descriptive: ratings of observed practice |

Dietitians (n = 4) Patients (n = 24) Carers (n = 11) |

1. To evaluate the impact of a renal diet question prompt sheet on patient centredness in dietitian outpatient clinics 2. To describe the impact of a renal diet question prompt sheet on the volume and pattern of communication between dietitians and patients/carers |

**** | The proportion of utterances devoted to building a relationship reduced significantly (from 15.7% to 9.8%) (p < 0.0001) | |

| Laquatra and Danish, 62 USA | Quantitative—cross‐sectional analytical: ratings of observed practice | Nutrition and nursing students (n = 30) | To evaluate an attempt to have nutrition counselling students, who were previously trained by the Danish, D'Augelly, and Hauer method through an academic course, transfer helping skills to the nutrition counselling setting | * | Students in the experimental group differed from the control group in their verbal behaviours which facilitated the development of a helping relationship | |

| Lee and Won, 63 Canada | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (paper) | Clients (n = 130) | To examine the patterns of patient‐provider collaboration among patients undergoing radiotherapy | *** |

Client scores for collaboration with dietitians were significantly lower than scores for radiation oncologists, radiation therapists and nurses The level of client‐dietitian collaboration may depend on the level of symptom distress the client is experiencing |

|

| Levey et al., 64 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone) | Dietitians (n = 12) | To explore the barriers and enablers to delivering patient‐centred care from the perspective of primary care dietitians | ***** |

Dietitians explained that it was challenging to build rapport (among other required tasks) in the allocated time Dietitians described rushing in an attempt to meet perceived expectations from clients and consequently neglecting to spend time building rapport with them Dietitians felt pressure from physicians to address clients' concerns immediately rather than spend time building rapport |

|

| Lewis et al., 65 USA | Quantitative—cross sectional analytical: ratings of observed practice | Nutrition students (n = 34) | To evaluate a 3‐hour workshop as a method for teaching relationship‐establishing skills to nutrition students | ** | Some skills that were taught within the workshop were described as ‘initial relationship‐building skills’ | ‘Establishes rapport’ identified as an interviewing skill that was demonstrated by less than half of the experimental group pre‐workshop. Post‐workshop scores of experimental and control group students did not differ significantly |

| Lok et al., 66 China | Mixed methods: ratings of observed practice and interviews |

Nutritionists (n = 4) Clients (n = 24) |

To explore the views of four nutritionists and observe their practice and relationship with patients attending a community‐based lifestyle modification program on lifestyle and behaviour change, and whether this affected the outcomes of the lifestyle modification program in terms of overall weight loss | *** |

Common themes emerged from all four nutritionists on the importance of establishing a good relationship with the patient Some nutritionists had a shared understanding of the importance of the nutritionist‐patient relationship in helping patients find underlying issues and solutions Nutritionists need to be trained to conduct programs in the same way as it can affect their relationships with clients and consequent weight outcomes |

Rapport was identified as a subtheme across multiple themes (attitude towards patients, strategy to tackle weight loss and counselling skills) Common themes emerged on the importance of establishing a good rapport with patient Nutritionists identified establishing rapport as a main counselling strategy Unconditional acceptance, genuineness and empathy were identified as highly important to achieve rapport |

| Lordly and Taper, 67 Canada | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone and face‐to‐face) |

New graduate dietitians (n = 8) Program supervisors (n = 6) |

To examine dietitians and graduate perceptions of the risks and benefits associated with the acquisition of entry‐level clinical competence within a single practice environment | ***** |

Decreased opportunity to establish relationships in acute care versus long‐term care settings was recognised, where greater opportunity to focus on relationship building was identified The long‐term care environment was identified as providing rich opportunity to gain important entry‐level competencies related to relationship‐building |

|

| Lovestam et al., 68 Sweden | Qualitative: analysis of dietitians' documentation of patient consultations | Dietetic entries in patient file (n = 30) | To explore how the dietetic notes contribute to the construction of the dietetic care and patient‐dietitian relationship | ***** |

A lack of representation of the dietitian‐patient relationship within dietetic entries identified A negative effect of the dietitian's picture of the patient (constituted through writing in patient notes using a particular language) on the relationship with a patient was suggested The importance of the relationship in dietetics was identified, and justified through the explanation that dietetic counselling involves sensitive personal issues |

|

| Lovestam et al., 69 Sweden | Qualitative: focus groups | Dietitians (n = 37) | To explore Swedish dietitians' experiences of the nutrition care process terminology in relation to patient record documentation, the patient and the dietitians' professional role | ***** |

Dietitians emphasised the importance of the dietitian‐patient relationship over needing to document according to the nutrition care process terminology Dietitians described postponing and revising their formulation of a diagnosis statement where appropriate, until a stable relationship with their patient was established Dietitians described needing time to develop a relationship in the initial stage of engaging with a client |

|

| Lu and Dollahite, 70 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (online) | Dietitians (n = 612) | To develop a valid and reliable instrument and use it to measure dietitians' nutrition counselling self‐efficacy and reported use of a set of counselling skills. The association between nutrition counselling self‐efficacy and various factors were also examined. | *** |

Some skills generated from the survey were described as those most often employed for ‘relationship‐building purposes’ Self‐efficacy scores for survey item ‘clarify to your clients the roles and responsibilities of the dietitian‐client relationship’: All participants (mean = 7.03, SD = 1.76), those participants who counsel more than 50% of their work week (mean = 7.10, SD = 1.79) and those who counsel for less than 50% of their work week (mean = 6.75, SD = 1.61). The difference between those participants who counsel more than 50% of their work week and those who do not was significant (p < 0.05) |

|

| MacLellan and Berenbaum, 71 Canada | Quantitative—descriptive: Delphi |

Dietitians (n = 57) (Round 1) Dietitians (n = 48) (Round 2) |

To determine the meaning that dietitians ascribe to the client‐centred approach and to identify the important concepts and issues inherent in this approach to practice | *** |

Wording of the survey concerned some participants as it was perceived to suggest an imbalance of power in the client‐dietitian relationship Whether dietitians respect the expertise that clients bring to counselling relationships was questioned |

Whether dietitians are ready to be working in partnership with clients was questioned |

| MacLellan and Berenbaum, 72 Canada | Qualitative: open‐ended interviews (telephone) | Dietitians (n = 25) | To explore dietitians' understanding of the client‐centred approach to nutrition counselling | *** |

‘Building a relationship’ identified as a theme in dietitians' responses as to how they understand client‐centred counselling The importance of understanding how to develop a therapeutic relationship with clients as part of being an effective counsellor was identified |

|

| Madden et al., 73 UK | Qualitative: interviews (telephone or face‐to‐face) and focus groups |

Clients (n = 29) Carers of clients (n = 5) |

To identify the preferences for diet and nutrition‐related outcome measures of patients with coeliac disease and their carers | ***** | Clients preferred to see the same dietitian at each appointment, where an example was given of being able to develop rapport over time | |

| McCarter et al., 74 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone) | Clients (n = 9) | To explore experiences of head and neck cancer patients receiving a novel dietitian‐delivered health behaviour intervention based on motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy as part of a larger investigation examining the effect of this intervention on malnutrition in head and neck cancer patients, undergoing radiotherapy. More specifically, to explore the patient's working relationship with the dietitian, specific components of the eating as treatment interventions and suggestions for improving the intervention. | *** | The importance of the dietitian being empathetic and supportive for the relationship was identified | A supportive partnership was an important part of valued working relationships between patients and their dietitian |

| Milosavljevic et al., 75 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews | Dietitians (n = 32) | To examine how New South Wales public hospital dietitians perceive their workplace and its influence on their ability to function as healthcare professionals | ***** | Relationships were described as a source of value across all career stages, and particularly important for specialist dietitians and mid‐career dietitians | |

| Morley et al., 76 Canada | Qualitative: discussion groups (telephone) | Dietitians (n = 22) | To develop guidelines for client‐centred nutrition education | *** | A model for collaborative client‐centred nutrition education was developed and described in the context of ‘fostering collaborative relationships with clients’ | Collaborative client‐dietitian partnerships are integral to helping clients find ways of eating, feeding or thinking about food that are actionable and consistent with their lives |

| Morris et al., 77 UK | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone) | Patients (n = 20) | To explore and describe the renal patient's perspectives of the dietitians' different communication styles, and to qualitatively evaluate which approaches provide the best level of patient‐satisfaction when engaging with dietetic services | ***** |

The ‘adult‐adult ego state’, experienced as a helpful engagement style, showed evidence of improved relationships when dietitians employed good counselling skills Risks were identified for the relationship if the ‘parent–child dynamic’ dominates the client‐dietitian relationship Relationships were described as building from collaborative power‐sharing between the client and dietitian, and problematic relationships were described when consultations are dietitian‐centred The potential of the client's amount of disposable income, food preparation skills and family commitments was suggested as having the potential to diminish the relationship |

‘Effective partnership’ was identified as a subtheme of the main theme ‘helpful engagement style’ The suggestion was made that prescription interventions should be consciously chosen with caution, awareness and sensitivity by the dietitian to not inhibit further communication and collaboration Good rapport forms part of the foundation needed for a directive message to be well received Higher literacy levels of the client might contribute to a more equal partnership with the dietitian rather than a parent–child dynamic |

| Murray et al., 78 Australia | Quantitative—randomised controlled trial (secondary analysis): ratings of observed practice |

Clients (n = 307) Dietitians (n = 29) |

To explore whether therapeutic alliance improved after dietitians were trained in eating as treatment | **** |

No effect of the intervention (eating as treatment) was found on dietitian‐rated alliance (p = 0.237) Patient‐rated alliance was 0.29 points lower after intervention training (p = 0.016) No specific motivational interviewing techniques predicted patient‐rated alliance Dietitian acknowledgement of patient challenges was related to dietitian‐related alliance (β = 0.15, p = 0.035), and described as being worthy of inclusion in future efforts to develop a therapeutic alliance No evidence was identified to suggest therapeutic alliance was improved by training dietitians in motivational interviewing The need to further explore motivational interviewing and its impact on therapeutic alliance was identified, specifically using appropriate and sensitive alliance measures |

|

| Nagy et al., 79 Australia | Quantitative—descriptive: ratings of observed practice |

Health coaches (n = 2) Study participants (n = 50) |

To explore relationships between therapeutic alliance and various contextual factors in health coaching sessions held within a weight loss trial | **** |

The session duration was significantly correlated with ‘Bond’ scores (r = 0.42, p = 0.002). The suggestion that spending more time in a session appears related to increased bonding (a key component of therapeutic alliance) was made Participants who had completed preparatory exercises had significantly higher total alliance (F (2, 47) = 4.88, p = 0.012), ‘Goal’ (F (2, 47) = 6.76, p = 0.003) and ‘Task’ scores (F (2, 47) = 4.88, p = 0.012). The suggestions that preparatory work may help build therapeutic alliance and agreement on goals appears to influence follow‐up completion were made Participants who completed the follow‐up session scored significantly higher for ‘Goal’ compared to no follow‐up’ (t [20.61] = 2.29, p = 0.03) The suggestion that findings from this study provide future directions for research addressing the professional relationship in dietetic consultations for weight loss was made |

|

| Nagy et al., 6 Australia | Qualitative: Semi‐structured interviews (online and telephone) | Dietitians (n = 22) | To explore dietitians’ perspectives of how they develop meaningful relationships with clients in the context of lifestyle‐related chronic disease management | ***** | Conceptual model of relationship development from the dietitians’ perspective was developed. The model shows that from the dietitian's perspective, relationship development appears complex due to the dietitian's role of simultaneously managing both the direct interaction with their client and other influences. The model consisted of three main categories 1. ‘Sensing a Professional Chemistry’ (an apparent natural ‘chemistry’ important for relationship development) 2. ‘Balancing Professional and Social Relationships’ (two relationships existing, one that focuses on the roles of ‘professional’ or ‘client’, the other focuses on ‘humans’ interacting and the importance of humanity) 3. ‘Managing Tension with Competing Influences’ (relationship development can be influenced by factors unrelated to their direction interaction e.g. physical environment) | The category ‘Sensing a Professional Chemistry’ arose from dietitians’ descriptions of good relationships, where ‘gelling’, ‘clicking’, ‘connection’, ‘subconscious aspect’ and ‘vibe’ were used. Dietitians further explained these terms to an extent, which included ‘rapport’ ‘Duality of developing rapport’ was identified as a thematic subcategory of the conceptual model, which refers to dietitians perceiving that developing rapport is both a natural and unnatural skill, both easy and difficult with particular clients, and should be a focus both during initial stages of interacting and throughout all interactions The suggestion was made that the apparent duality of rapport development may depend on the individuals within the interaction |

| Notaras et al., 80 Australia | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (paper) |

Dietitians (n = 17) (pilot) Dietitians (n = 34) (second round) Dietitians (n = 50) (pre and post evaluation) |

To develop, implement and evaluate an education program on improving communication and nutrition counselling skills for dietitians working in both acute inpatient and outpatient settings within the South Western Sydney Local Health District in New South Wales, Australia | **** |

The session outline included ‘therapeutic relationship between patient‐dietitian’ The suggestion that sub‐optimal nutrition counselling skills may hinder the development of an effective dietitian‐patient relationship was made The relationship was identified as the cornerstone of having successful motivating conversations that have the potential to promote patients' intrinsic motivation for eating behaviour change |

|

| Raaff et al., 81 UK | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone) | Dietitians (n = 18) | To explore dietetic views, attitudes and approaches to weight management appointments with preadolescent children | ***** | Dietitians identified the importance of building relationships with paediatric clients | Dietitians identified the importance of building rapport with paediatric clients (as part of subtheme ‘dietitian verbally engages the child in the conversation’). Establishing rapport with the child from the beginning of the consultation was identified as a strategy to include the child in verbal disclosure |

| Russell et al., 82 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey and ratings of observed practice | Students (n = 7) |

1. To assess untrained graduate students in nutrition on their application of a set of 31 specific clinical skills for resolving dietary adherence problems 2. To describe the procedures for and feasibility of the evaluation program |

* |

Very few students demonstrated possession of listening skills These findings were described as ‘concerning’ due to these skills being crucial to establishing the collaborative relationship needed for effective counselling |

Describing interviewing skills identified in the study as being crucial to developing rapport |

| Sharman et al., 83 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone) | Dietitians (n = 14) | To explore in detail dietitians' perceptions of the interviewing process, the degree to which this is challenging and the nature (if at all) of any challenges involved in conducting investigative interviews with children | ***** |

Strategies were identified to overcome disengagement from paediatric clients and build rapport with them Focusing on rapport, rather than in‐depth questioning, was identified as a strategy to ensure paediatric clients' engagement in consultation |

|

| Sladdin et al., 84 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone) | Clients (n = 11) | To explore patients' experiences and perspectives of patient‐centred care in individual dietetic consultations | ***** |

‘Fostering and maintaining caring relationships’ was identified as a main theme involving developing a holistic understanding of the client, being invested in the client's wellbeing and possessing caring qualities Clients who experienced caring relationships with their dietitian suggested a desire to continue their relationship, thus the importance of caring relationships was identified Clients identified dietitians being positive, enthusiastic, supportive, respectful and trustworthy as valuable to their relationship Some clients described their relationship with a dietitian as being instrumental to their healthcare progress Identified themes suggest an integrated approach to fostering caring relationships The need for dietitians to relinquish control during consultations to facilitate improved relationships was suggested |

A participant described having a partnership with their dietitian (forming part of major theme ‘fostering and maintaining caring relationships’) |

| Sladdin et al., 85 Australia | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (mail) |

Clients (n = 133) Dietitians (n = 180) |

To compare patients' and dietitians' perceptions of patient‐centred care in dietetic practice | *** |

Patients reported significantly lower scores compared to dietitians for their perceptions of a caring patient‐dietitian relationship (p = 0.009) The importance of considering strategies for dietitians to foster and maintain good relationships with patients was identified The suggestions were made that patients may be encouraged to engage in ongoing care with their dietitian if a good relationship is developed, and that establishing a shared understanding at the beginning of a consultation may help foster positive relationships |

Establishing a shared understanding at the beginning of the consult may help foster collaboration between patients and dietitians |

| Sladdin et al., Australia 86 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: interviews and survey |

Dietitians (n = 10, interviews) Dietitians (n = 180, survey) |

To develop and test a dietitian‐reported inventory to measure patient‐centred care in dietetic practice | *** |

‘Patient‐dietitian relationship’ identified as component of conceptual model of patient‐centred care, described as ‘a genuine, reciprocal relationship… based on trust, respect, rapport building and mutual understanding’ Fifth factor of developed inventory identified as ‘caring patient‐dietitian relationships’ |

|

| Stetson et al., 87 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: ratings of observed practice |

Dietitians (n = 30) Clients (n = not specified) Complete recordings (n = 29) |

To assess the teaching and adherence promotion skills of dietitians in routine clinical practice | ** | Dietitians were described as using accepted strategies for developing and maintaining good interpersonal rapport with patients | |

| Sullivan et al., 88 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (mail) | Internship directors (n = 66) | To determine internship directors' expectations for preparedness of entering interns and the emphasis given to preparation for both nutrition education and nutrition counselling in internship programs. The directors' perceptions of the need for students to have advanced preparation in these areas after the internship were also addressed. | * |

‘Uses helping skills and develops a trusting relationship with client’ was listed as a knowledge/skill area questioned in survey Results for internship directors' expectations for intern preparation in nutrition education and counselling knowledge/skills (as percentage): pre‐internship preparation; basic (68) and advanced (21), internship training; none (3), moderate (39) and extensive (56), post‐internship training needs; preparation adequate (73) and needs more (19) |

|

| Sullivan et al., 89 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: survey | Dietitians (n = 40) | To examine overall job satisfaction and specific domains of job satisfaction among renal dietitians | *** | The most commonly named positive aspects of working as a renal dietitian consisted of ‘developing long‐term relationships with patients’ (33% of respondents) | |

| Sussmann, 90 UK | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (face‐to‐face) | Patients' and patients' partners (n = 8) | To examine the difficulties faced by renal dialysis patients on a restricted diet and to ascertain how the dietitian can most effectively help patients deal with these difficulties | ***** |

The suggestion that findings support the argument for mutually cooperative, genuine and personal relationships was made The recommendation that dietitians develop a friendly and supportive relationship to facilitate a trusting relationship was made |

|

| Taylor et al., 91 Canada | Survey (online and mail) | Dietitians (n = 349) | To elicit registered dietitians' beliefs, guided by the theory of planned behaviour, regarding using a nutrition counselling approach in their daily practice and describe variables influencing registered dietitians use of Nutrition Counselling Approach in their practice | ** | The approach used in the study, named as the ‘nutrition counselling approach’ was described as a ‘collaborative counsellor‐client relationship’ | Dietitians perceived improved collaboration between them and their patients as an advantage of a particular counselling approach (nutrition counselling approach) |

| Trudeau and Dube, 92 Canada | Survey (mail) | Clients (n = 49) |

1. To explore the variation in patients' satisfaction and compliance intentions 2. To measure the effect of a series of individual characteristics and contextual factors on patients' overall satisfaction and compliance intentions |

** |

A tested component of dietary counselling was identified as ‘affective communication skills’, and defined as ‘interpersonal qualities of the dietitian (e.g., courtesy, warmth and attentiveness) that help build a positive relationship with the patient’ No significant impact of affective communication skills on patient satisfaction was identified. The suggestion was made that patients would have needed to be either more extremely pleased or disappointed with the dietitian to make a conscious satisfaction judgement based on communication skills |

|

| Warner et al., 93 Australia | Qualitative: semi‐structured interviews (telephone and face‐to‐face) | Clients (n = 21) | To describe the patients' acceptability and experiences of a telehealth coaching intervention using telephone calls and tailored text messages to improve diet quality in patients with stage –4 Chronic Kidney Disease | ***** | ‘Valuing Relationships’ identified as one of five major themes consisting of subthemes: receiving tangible and perceptible support, Building trust and rapport remotely, Motivated by accountability, Readily responding to a personalised approach, Reassured by health professional expertise |

‘Building… rapport remotely’ identified as subtheme of major theme ‘valuing relationships Individualised text messages were found to ‘enhance participant‐clinician interactions’ (between dietitian as telehealth coach and participant) |

| Whitehead et al., 94 UK | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (mail) | Dietitians (n = 1158) |

1. To ascertain dietitians' experiences of, and views on, both pre and post‐registration dietetic training 2. To identify any barriers to incorporating a patient‐centred approach and communication skills for behaviour change within the profession |

** |

Post‐registration training had been undertaken by 73% of respondents, of which 90% perceived had led to improvements in their relationship with patients The suggestion was made that better relationships with patients lead to improved working environment and retention of staff |

|

| Whitehead et al., 95 UK | Mixed methods: ratings of observed practice, survey and interviews |

Dietitians (n = 15) (Face and content validity) Student dietitians and dietitians (n = 113) (Intra‐rater reliability, construct and predictive validity) Dietitians (n = 9) (Inter‐rater reliability) Dietitians (n = 8) (Face validity) |

To develop a short, easy‐to‐use, reliable, valid and discriminatory tool for the assessment of the communication skills of dietitians within the context of a patient consultation | *** | A transition from a ‘relationship‐building’ phase to ‘advice‐giving’ phase in a dietetic consultation was described |

‘Establishes rapport’ was perceived to be important and thus was included in the developed communications tool Observations from interviews suggested that most dietitians established rapport but did not maintain rapport throughout the consultation Rapport was lost when dietitians moved onto the more dietetic‐specific content of the consultation |

| Williamson et al., 96 USA | Quantitative—descriptive: interviews (telephone) | Dietitians (n = 75) |

1. To identify factors that contribute to barriers to dietary adherence in individuals with diabetes identified in a 1998 study 2. To obtain recommendations from registered dietitians for overcoming the barriers |

* | ‘Building rapport’ was identified as a common recommendation for overcoming barriers to dietary adherence in individuals managing diabetes | |

| Yang and Fu 97 Malaysia | Quantitative—descriptive: survey (online and paper) | Dietitians (n = 69) |

1. To determine the clinical dietitians' empathy level in Malaysia 2. To determine the factors associated with the dietitian's level of empathy |

*** | Suggested that the dietitian's capability in expressing empathy will influence the development of ‘good’ therapeutic dietitian‐patient relationships | |

| Yang et al., 98 Malaysia | Quantitative—descriptive: surveys |

Dietetic interns (n = 57) Clients (n = 99) |

1. To investigate the empathy level of dietetic interns at selected primary and tertiary health‐care settings through self‐reported measures and patient perception 2. To determine the association between both measures |

*** | Suggestion that further research should consider the duration of the interaction between clients and dietetic interns as impacting the extent to which dietetic interns can demonstrate empathy |

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Quality evaluation tool applied to quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods study designs. Score ranges from meeting none of the five criteria (as specified in table) to meeting all five criteria (*****).

TABLE 2.

The proportion of quantitative, qualitative or mixed method studies (n = 76) meeting a number of criteria specified within the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool 27

| MMAT a | |

|---|---|

| Number of criteria met | n (%) |

| 0 | 2 (3) |

| 1 | 7 (9) |

| 2 | 10 (13) |

| 3 | 20 (26) |

| 4 | 6 (8) |

| 5 | 31 (41) |

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.

Five themes were identified across both analyses, which pertained to the primary terms (‘relationship’ and ‘alliance’) and associated terms (e.g., ‘connection’). The themes showed that the therapeutic relationship: (i) is valued within clinical dietetic practice, (ii) involves complex and multifactorial interactions, (iii) is perceived as having a positive influence, (iv) requires skills training, and (v) is embedded in practice models and tools. The findings are described below by theme and whether they correspond to primary terms or associated terms.

The first theme reflected the finding that the therapeutic relationship appears important and valued by both parties as a component of the clinical dietetic consultation. This was mostly seen within qualitative findings; however, was also reported from quantitative and mixed methods findings. For example, Sladdin et al. undertook semi‐structured interviews with patients to explore their perspectives of patient‐centred care and concluded that ‘patients want to have caring relationships with dietitians’. 84 Descriptors of the type of relationship valued by dietitians and clients included ‘caring’, ‘genuine’, ‘positive’, ‘supportive’ and ‘ongoing’. However, a qualitative study described few clients perceiving that an ‘ongoing’ relationship would be useful in the context of type 2 diabetes management, based on the content and delivery of initial consultations attended. 7 Authors specified that this was the case for clients who were both satisfied and unsatisfied with their consultation; however, only specified a reason for those that were satisfied. Authors described these clients as perceiving that they had obtained the information they needed and did not perceive the need for an additional consultation. 7 Hence, the majority of data indicated that the client‐dietitian relationship is valued but one study found clients with diabetes did not view an ongoing relationship as being of value.