Abstract

There is a dearth of research on how negative religious attitudes towards LGBTQ people inform professional practice. This paper reports on a scoping review of 70 selected studies from 25 different countries. It explores key issues and knowledge gaps regarding the delivery of services to LGBTQ adults by religious healthcare, social care and social work organisations and/or practitioners with faith‐based objections to LGBTQ people and their lives. The review identified four main themes: (1) a close connection between religious affiliation and negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people, among both students and professionals; (2) a heightening effect of religiosity, particularly among Christian and Muslim practitioners/students; (3) educators’ religious attitudes informing curriculum design and delivery, and some highly religious students resisting and/or feeling oppressed by LGBTQ‐inclusivity, if present; (4) examples of practice concerns raised by professionals and lay LGBTQ people. The article considers the ethical, practical, educational and professional standards implications, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

Keywords: attitudes, healthcare, LGBTQ, practice, religion, social care, social work

What is known about this topic

Most of the major religions, especially the more orthodox elements, are doctrinally opposed to LGBTQ people.

There are concerns about whether religious practitioners can work effectively with LGBTQ patients/clients if they are opposed to them on religious grounds.

There are concerns about whether religious organisations can deliver LGBTQ affirmative care/social welfare services.

What this paper adds to this topic

Religious affiliation and religiosity can inform negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people among healthcare, social care and social work students, practitioners, and educators.

Christian students and practitioners who take a literal interpretation of the bible are more likely to be resistant to reflective discussions and to moderating their beliefs and attitudes.

There is a need to better understand whether/how negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people affect practice.

1. INTRODUCTION

This article reports on a United Kingdom (UK) scoping review of the international literature on religious attitudes towards lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and queer (LGBTQ) people among healthcare, social care and social work students and professionals. There remain enduring tensions between the traditional doctrine of the major world religions and LGBTQ rights (Campbell et al., 2019; Janssen & Scheepers, 2019). While many religious individuals mediate traditional doctrine with real‐life pragmatics to take a more inclusive approach to marginalised groups (Valentine & Waite, 2012), not all do. Some religious individuals take a more literal approach to sacred texts and are also more likely to adhere to negative views about LGBTQ people and/or be opposed to their rights (Acker, 2017; Fisher et al., 2017). How this translates into the delivery of healthcare, social care and social work provision to LGBTQ people is not yet clear.

There is a growing body of literature suggesting that some healthcare, social care and social work practitioners with negative views towards LGBTQ people are informed by their religious beliefs (Balik et al., 2020; Bradbury‐Jones et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2018; Chonody & Smith, 2013; Dessel & Bolen, 2014; Dorsen, 2012; Hodge, 2005, 2011; Lim & Hsu, 2016; Stewart & O’Reilly, 2017). Despite the decline in religious affiliation in the UK (National Centre for Social Research, 2019), religion still plays an important role in health and social care: a quarter of charity sector funding in England and Wales is received by religious charities (Bull et al., 2016); 2000 of the 11,000 care homes for older people the UK are run by religious organisations (Collinge, 2020), many of whom also run day and community care services; 42% of all social workers in England identify as Christian (Social Work England, 2021a); and 5000 doctors, 900 medical/nursing students and 300 nurses and midwives belong to the evangelical UK and Ireland Christian Medical Fellowship (CMF, 2022).

Additionally, the UK relies extensively upon migrant workers to staff its social care provision (Turnpenny & Hussein, 2021), many originating from countries where LGBTQ people have few, if any, rights and where religious‐based homophobia and transphobia (in which British imperialism and colonialism are often implicated, Lalor, 2021) prevail (Human Rights Watch, 2021). In 2019/20, the ‘top ten’ non‐UK nationalities of the UK care workforce were from Romania, Poland, Nigeria, the Philippines, India, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Portugal, Italy and Jamaica (Skills for Care, 2020). Migrant workers from these countries can experience a profound culture clash when working in more liberal UK health, care and social work contexts (Carr, 2008; Carr & Pezzella, 2017; Hafford‐Letchfield et al., 2018; Westwood, 2022; Willis et al., 2018), while at the same time also experiencing racialised prejudice and discrimination themselves (Allan, 2021; Allan & Westwood, 2016; Ranci et al., 2021; Stevens et al., 2012).

There is a significant debate, presently in the United States, as to whether providers with religious objections to LGBTQ people can deliver affirmative care which ‘validates and supports’ those people and their lives (Mendoza et al., 2020, p.31). However, there has not yet been a literature review that focuses on the place of religion in relation to the delivery of healthcare, social care and social work services to LGBTQ people. This article addresses this knowledge gap. It reports on a scoping review of 70 selected studies from 25 countries, identifying key issues and knowledge gaps. Ethical, practical, educational and professional standards are considered and the need for further research is discussed.

2. BACKGROUND

Recent reviews of the literature have suggested that healthcare, social care and social work practitioners with negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people can be informed by their religious beliefs. Reviews of the literature on nursing attitudes towards LGBTQ people reported that religious affiliation and religiosity were associated with negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people (Balik et al., 2020; Dorsen, 2012; Lim & Hsu, 2016; Stewart & O’Reilly, 2017). In a systematic review of the literature on mental health practitioners’ attitudes towards trans people, Brown et al. (2018, 14) reported a connection between increased religiosity and negative attitudes.

A systematic review of LGBTQ educational initiatives with health and social care practitioners reported that some studies found a ‘conflict of values, especially related to religion’ (Jurček et al., 2021, p.54). Other authors have also identified that some educators, pedagogies and/or curricula are silent and/or negatively disposed towards LGBT + people, based on religion, while there can be a reluctance to challenge/engage with students ‘who have religious or cultural beliefs that consider LGBT + identities as pathological, deviant and sinful’ (Higgins et al., 2019, p.10). A review of the literature on professional practice learning in medicine, nursing and social work (Bradbury‐Jones et al., 2020, p.1629) observed that ‘Eleven studies highlighted the influence of gender, ethnicity and religion on creating discriminatory [learning] environments, with religion playing an important and… predominantly negative role’. A review of the impact on healthcare students and staff of education and training on LGBT + health issues was conducted by researchers in Nigeria. They found that the impact was mediated by ‘Pre‐existing cultural and religious prejudice against LGBT people (in USA and Africa) or specifically MSM (men who have sex with men) in African communities’ (Sekoni et al., 2017, 21,630).

Negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people have potential equality implications, if those attitudes affect the equitable delivery of services. The UK Equality Act 2010 prohibits discrimination on the grounds of nine protected characteristics, including religion, sexual orientation and gender reassignment (expanded by case law to include transgender identities more broadly). UK professional standards also mandate non‐discriminatory practice (General Medical Council, 2013; Nursing & Midwifery Council, NMC, 2018; Scottish Social Services Council, 2016; Skills for Care, 2022; Social Care Wales, 2017; Social Work England, 2021b), as too do international standards/regulations. For example, Principle 1 of the Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles (International Federation of Social Workers, 2018), states that.

Social workers recognize and respect the inherent dignity and worth of all human beings in attitude, word, and deed. We respect all persons, but we challenge beliefs and actions of those persons who devalue or stigmatize themselves or other persons.

Additionally, Principle 3 states that social workers will have ‘respect for diversity’ and will ‘challenge discrimination and institutional oppression’, including relating to gender identity and sexual orientation.

Such anti‐oppressive standards can pose challenges for social workers who adhere to religious beliefs which support LGBTQ oppression, such as those who are opposed to same sex marriage (Ngole, 2016). There have been three recent relevant court cases in the UK. In the first, a doctor unsuccessfully claimed unfair dismissal for refusing, on the grounds of his religious beliefs, to refer to trans people by the pronouns with which they identified. 1 In the second case, 2 a conservative Christian social work student from Cameroon who made homophobic comments on his Facebook page, quoting from religious texts which described people who engage in same‐sex relations as ‘an abomination’, successfully appealed expulsion from his course because of them (Mason et al., 2020). In the third case, 3 an evangelical Christian fostering and adoption agency challenged a UK regulatory requirement that it ceases its policy to only employ staff and volunteers who are evangelical Christians and who ‘refrain from “homosexual behaviour”’ 4 and to only recruit carers who are ‘evangelical married heterosexual couples of the opposite sex’. 5 The court ruled that the agency could recruit evangelical Christians but could not exclude LGBTQ people.

These cases are, of course, extreme examples, and not indicative of practice in general. There is a need then to understand how religious beliefs inform professional attitudes towards LGBTQ people, and their equality, education and practice implications. The literature review reported here contributes to developing such an understanding.

3. METHODOLOGY

The research question was: ‘What are the key issues and knowledge gaps in relation to religious healthcare, social care and social work organisations and/or practitioners with faith‐based objections to LGBTQ lives and lifestyles, providing services to LGBTQ adults?’ The methodology deployed was a scoping literature review, conducted by a single experienced researcher. Scoping studies are useful to map an emerging area of research, identify its range and extent, clarify key concepts, identify gaps in the literature and refine future research inquiries (Levac et al., 2010). Unlike systematic reviews, the quality of included studies is not assessed. However, scoping studies go further than narrative reviews, in that there is an analysis of the findings. This scoping review used Arksey and O’Malley's (2005) six‐stage methodology:

Stage 1: identifying the research question

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Stage 3: study selection

Stage 4: charting the data

Stage 5: collating, summarising, and reporting the results

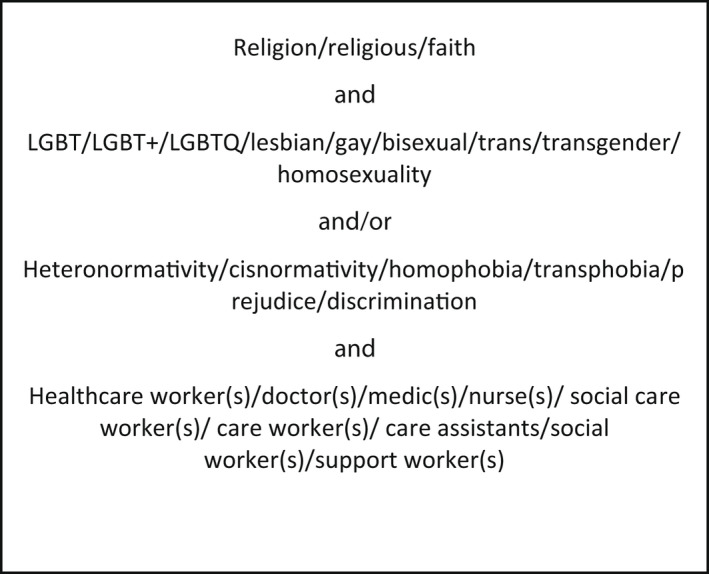

This review is part of a seed‐funded research project, which also includes stakeholder consultation (to be reported elsewhere), which is Arksey and O’Malley's sixth stage. The search terms used are listed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Search terms

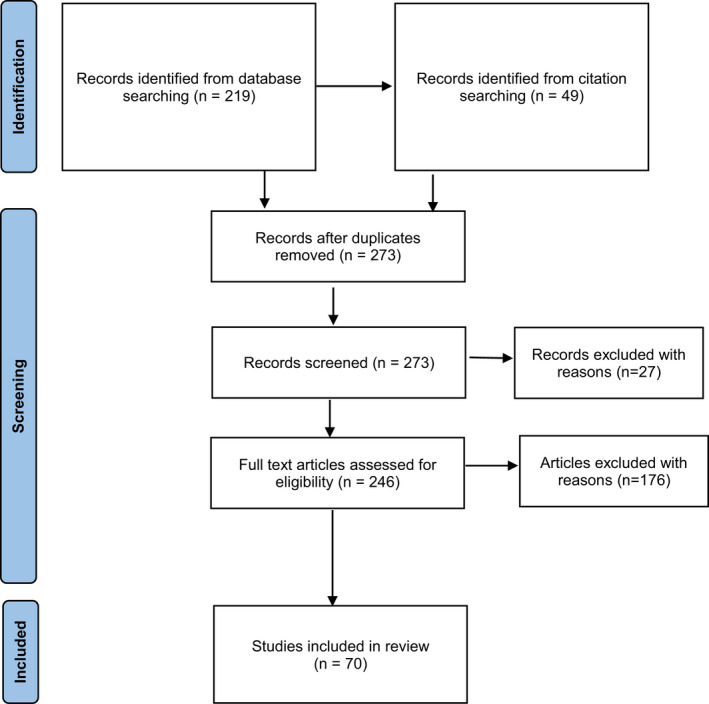

The databases searched were: CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Medline, PsycNet, PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, and Google Scholar. Literature was limited to English language publications, between January 2010 and March 2021. Both academic and grey literature were included. This was supplemented by citation searching, that is, crosschecking references in selected literature. The full search process is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram for search and selection process for scoping review

This larger body of literature, comprising 246 items, was then sifted. Literature on faith‐based care in healthcare, social care and social work contexts which did not refer to both LGBTQ/minority sexuality/minority gender identity and religion/religiousness/religiosity in the findings was excluded. Systematic, scoping, narrative and literature reviews without original data were excluded. Two pairs of articles which described the same data were analysed together (to avoid data repetition). In all, 176 items were excluded, and 70 items were included in the final selection.

The overarching themes of the data were identified using thematic analysis. This approach was chosen with the aim of making an interpretive analysis (Boyatzis, 1998) without developing it into new theory, as in grounded theory, for example. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) staged approach was used to identify themes for their frequency, significance placed upon them by authors, any tensions/contradictions and saliency (Buetow, 2010). Four main themes were identified: religious affiliation and negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people; magnifying effects of religiosity; education and training; practice concerns.

This literature review was ethically compliant (Wager & Wiffen, 2011), in that it: followed a specific methodology; avoided redundant duplications, acknowledging when the same data set was used in more than one publication; avoided plagiarism (i.e. either used its own language or explicitly quoted original authors); identified funding sources; identified that it was conducted by a single researcher; ensured accuracy; and was conducted from an anti‐oppressive stance (Rogers, 2012).

3.1. Results: Characteristics of selected studies

Table 1 summarises the 70 selected studies, which were based on empirical research (quantitative and/or qualitative) conducted in 25 different countries (some in multiple countries), namely: Australia; Canada; Crete, Greece; Cyprus; Denmark; Germany; Hong Kong; Hungary; India; Italy; Malaysia; New Zealand; Peru; Portugal; Romania; Serbia; South Africa; Spain; South Korea; Switzerland; Taiwan; Turkey; the UK; and the United States.

TABLE 1.

Summary characteristics of studies included in the scoping literature review

| Name | Country | Aim(s) | Method(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acker (2017) | USA | Transphobia among students majoring in the helping professions. | Questionnaire completed by 600 undergraduate students (social work, nursing, psychology, occupational therapy). Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 2 | Ahrendt et al. (2017) | USA | Ageism & heterosexism re. older adult sexual activity among care providers in long‐term care facilities. | Vignette‐based questionnaire completed by 153 residential care staff (one religious‐based home, one public). Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 3 | Almack et al. (2010) | UK | Impact of sexual orientation on end‐of‐life care & bereavement within same‐sex relationships. | 4 focus groups with 15 lesbian & gay older people. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ narrative analysis. |

| 4 | Atteberry‐Ash et al. (2019) | USA | LGBTQ social work students’ experiences of ‘harmful discourse’. | Interviews with 12 students: Data analysis – qualitative (phenomenological analysis). |

| 5 | Austin et al. (2016) | USA | Trans social work students’ experiences at multiple universities. | Questionnaire completed by 97 trans social work students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis; qualitative ‐ thematic analysis; |

| 6 | Aynur et al. (2020) | Turkey | Nurse attitudes to LGBT people & demographics that influence them. | Questionnaire completed by 192 nurses working in a university hospital. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 7 | Barker (2013) | USA | Christian students’ experiences of social work educational programs. | Four focus groups with Christian social workers (total n = 30). Data analysis: qualitative ‐ thematic, no model described. |

| 8 | Baiocco et al. (2021) | 7 countries | LGBT+training needs of health/social care staff in UK, Denmark, Spain, Germany, Cyprus, Italy & Romania. | Questionnaire completed by 412 health & social care academics & workers. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 9 | Banwari et al. (2015) | India | Medical students & interns’ knowledge about & attitude towards ‘homosexuality’ | Questionnaire completed by 339 medical students & interns. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 10 | Bennett et al. (2017) [Same dataset as Chapman et al. (2012)] | Australia | Nurse attitudes towards LGBT+parents seeking health care for their children. | Questionnaire completed by 51 nurses & allied professionals. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis; qualitative ‐ thematic analysis. |

| 11 | BMA (2016) | UK | Attitudes towards LGB doctors & medical students in the workplace or place of study. | Questionnaire completed by 803 doctors/students identifying as LGB/ ‘prefer not to say’/did not respond. Methodology not described. Reporting = descriptive statistics & themed analysis. |

| 12 | Butler (2017) | USA | Older lesbians' experiences of home care. | Interviews with 20 lesbians aged 65 & over who had received home care services within the preceding 10 years. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ grounded theory. |

| 13 | Byers et al. (2020) | USA & Canada | Social work students' experiences of homophobic & transphobic microaggressions. | Questionnaire completed by 824 social work students. Data analysis = mixed methods: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis; qualitative ‐ thematic analysis. |

| 14 | Carabez et al. (2015) | USA | Nursing students' knowledge of LGBT healthcare needs & evaluate of effects of a teaching intervention. | Questionnaire completed by 120 students completed a survey. Data analysis: methods not described. Reporting comprised descriptive statistics & themed analysis. |

| 15 | Cartwright et al. (2012) | Australia | LGBT issues re. end‐of‐life care & advance care planning. | Telephone consultations (quasi‐interview) with 19 service providers & 6 members of LGBT community organisations. Data analysis ‐ qualitative, grounded theory. |

| 16 | Cele et al. (2015) | South Africa | ‘Homosexual’ patients’ experiences of primary health care | 12 semi‐structured interviews. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ content analysis. |

| 17 | Chapman et al. (2012) Same dataset as Bennett et al. (2017)] | Australia | Nursing & medical students’ knowledge & attitudes re. LGBT parents | Questionnaire completed by 150 nursing students & 171 medical students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 18 | Chaze et al. (2019) | Canada | Long‐term care homes’ websites’ inclusion of ethnoculturally diverse & LGBTQ older adults. | Content analysis of 103 long‐term care homes' websites. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ content analysis. |

| 19 | Chonody et al. (2014) | USA | Sexual prejudice separately toward gay men & lesbians among heterosexual social work faculty. | Questionnaire completed by 303 faculty staff. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 20 | Chonody et al. (2013) | USA | Catholic & Protestant social work students’ attitudes towards lesbians and gay men. | Questionnaire completed by 383 “completely heterosexual” students from four universities. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 21 | Cloyes et al. (2020) | USA | Hospice interdisciplinary teams’ attitudes toward sexual & gender minority patients & caregivers. | Questionnaire completed by 122 hospice team members across multiple hospices. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 22 | Coolhart and Brown (2017) | USA | Homeless LGBTQ teenagers and young adults’ experiences in in homeless shelters. | Semi‐structured interviews with young adults (14–21) (n = 7) who have used homeless services & providers of homeless services (n−9). Data analysis: qualitative ‐ grounded theory. |

| 23 | Cornelius and Carrick (2015) | USA | Nursing students’ knowledge of & attitudes toward LGBT healthcare concerns | Questionnaire completed by 190 nursing students. Data analysis not described. Reporting comprised descriptive statistics & themed analysis. |

| 24 | Corrêa‐Ribeiro et al. (2018) | Brazil | Adapt questionnaire to evaluate the knowledge of ‘homosexuality’ among heterosexual physicians in Brazil. | Questionnaire completed by 22 physicians. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 25 | de Jong (2017) | USA | Christian social work faculty members' attitudes towards transgender & gender‐variant people. | Questionnaire completed by 41 faculty members, across multiple social work schools. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive statistics. |

| 26 | Dessel et al. (2012) | USA & Canada | Social work faculty's attitudes re 'people of Color’, women, lesbian & gay people, their religious affiliation & religiosity. | Questionnaire completed by 327 faculty members. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 27 | Dunjić‐Kostić et al. (2012) | Serbia | Medical students’ knowledge about & attitudes towards ‘homosexuality’. | Questionnaire completed by 177 physicians & students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 28 | Fisher et al. (2017) | Italy | Compare attitudes toward LGBT people among 'gender dysphoric individuals', controls & healthcare providers. | Questionnaire completed by 310 respondents. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 29 | Fredriksen‐Goldsen et al. (2011) | USA & Canada | Social work faculty's attitudes towards LGBT people. | Analysis of survey data subset (n = 327). Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 30 | Guasp (2011) | UK | Surveys of 1050 heterosexual & 1036 LGB older people re. experiences & expectations of ageing | Not described. Questionnaire data. Reporting comprised descriptive statistics & themed analysis. |

| 31 | Hafford‐Letchfield et al. (2018) [Shared dataset with Willis et al. (2018)] | UK | LGBT+action research project with six care homes for older people to assess & develop services. | 35 semi‐structured telephone interviews pre‐& post‐interventions with 18 care home managers (CHMs), Community Advisors (CAs) & senior managers & a single focus group. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ thematic analysis. |

| 32 | Hatiboğlu et al. (2019) | Turkey | Social work students’ strategies for resolving conflicts between their personal & professional values. | ‘Reflections of 34 students’ attending a creative drama‐based group. Data were notes & memos, reflective diaries, group discussions. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ grounded theory. |

| 33 | Henrickson et al. (2021) | New Zealand | Older age residential care staff's, residents’ & family members’ attitudes towards 'sexually diverse' people. | Interviews with 77 participants including staff, residents & family members. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ thematic. |

| 34 | Holman et al. (2020) | USA | Efficacy of LGBT‐diversity training with senior housing facility staff | Pre‐ & post‐test surveys of 59 staff. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 35 | Howard et al. (2020) | Canada | How managers navigate resident sexual expression in care homes. | 28 in‐depth interviews with managers, clinical ethicists, geriatric specialists, & social workers. Data analysis: qualitative thematic analysis. |

| 36 | Jaffee et al. (2016) | Canada & USA | Incoming social work students’ attitudes toward sexual minorities | Questionnaire completed by 376 social work students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 37 | Johnston and Shearer (2017) | USA | Medical residents' attitudes, prior education, comfort, & knowledge re. transgender primary care. | Questionnaire completed by 67 internal medicine residents. Data analysis not described. Reporting comprised descriptive statistics. |

| 38 | Joslin et al. (2016) | USA | Social work students’ experiences in a Christianity & sexual minority intergroup dialogue. | Retrospective interviews with Christian‐LGB (n = 2) secular‐LGB (n = 3) & Christian heterosexual (n = 5) social work students. Data analysis: qualitative ‘constant coding method’. |

| 39 | Knocker (2012) | UK | Older LGB people's views and experiences of getting older & expectations of support services | Eight in‐depth interviews. Data analysis not described. |

| 40 | Kwak and Kim (2019) | South Korea | Homophobia among nursing students | Survey of 265 nursing students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive and complex statistics. |

| 41 | Lennon‐Dearing and Delavega (2016) | USA | Social workers’ & future social workers’ attitudes towards LGBT people | Questionnaire completed by 215 social workers & social work students. Data analysis methodology not detailed. Reporting comprised descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 42 | Leung (2016) | Hong Kong | Barriers to lesbian & gay people obtaining social services’ help after same‐sex partner abuse | Nine interviews with lesbians & gay men who had been abused by their same‐sex partners. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ grounded theory. |

| 43 | Lim et al. (2015) | USA | Baccalaureate nursing program faculty's knowledge about & readiness to teach re. LGBT health. | Questionnaire completed by over 1000 nursing faculty. Data analysis: quantitative – descriptive statistics; qualitative ‐ themed analysis |

| 44 | Lopes et al. (2016) | Portugal | Medical students’ knowledge & attitudes towards homosexuality | Questionnaire completed by 489 medical students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 45 | McCarty‐Caplan (2018) | USA | Organizational LGBT‐competence of social work program and its students. | Two‐stage survey. Full details not provided. Original thesis cited as source of more detailed methodology. Quantitative ‐ statistical analysis. |

| 46 | Messinger et al.(2020) | USA & Canada | Social work students’ experiences in field placement related to their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. | Qualitative thematic analysis of 207 survey responses from a larger study (Craig et al., 2015). |

| 47 | Ng et al. (2015) | Malaysia | Nursing students’ attitudes toward homosexuality. | Questionnaires completed by 495 nursing students in Malaysia. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 48 | Nieto‐Gutierrez et al. (2019) | Peru | Social, educational & cultural factors associated with homophobia among medical students. | Questionnaire completed by 883 medical students at 11 universities. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 49 | Papadaki et al. (2013) | Crete, Greece | Social work students’ attitudes towards lesbians & gay men | Questionnaire completed by 281 social work students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 50 | Pelts and Galambos (2017) | USA | Responses of 60 LTC staff who participated in a storytelling event involving older lesbian & older gay man | Questionnaire completed by 60 LTC staff, pre‐/post‐ storytelling intervention. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 51 | Prairie et al. (2019) | USA | Religiosity, geographic areas & healthcare professionals' attitudes toward ‘LGB & asexual’ people | Data from 1376 healthcare professionals (MDs & dentists) via public database. Data analysis not described. Reporting comprised descriptive & complex statistics /themed analysis. |

| 52 | Prairie et al. (2018) | USA | Healthcare providers’ perceived autonomy, religious faith & medical practice re. providing care for LGBT+people. | Questionnaire completed by 42 physicians & medical residents. Open ended questions, free‐text answers Data analysis: qualitative ‐ thematic. |

| 53 | Robinson (2016) | 5 countries | Aspects of ageing concerning older gay men in USA, Australia, New Zealand, UK. | Interviews with 25 men aged 60 & older who were recruited in Auckl&, London, Manchester, Melbourne, & New York. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ narrative analysis. |

| 54 | Schaub et al. (2017) | UK | Social workers’ beliefs & values about sexuality in relation to everyday professional interactions | Questionnaire completed by 112 social workers. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 55 | Simpson et al. (2016) | UK | Care home staff's attitudes, knowledge/policies & practices re LGBT residents. | Questionnaire completed by 187 individuals, including service managers & direct care staff. Data analysis (not described): descriptive statistics |

| 56 | Sirota (2013) | USA | Attitudes of nurse educators toward 'homosexuality' | Survey of 1282 nurse educators. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive and complex statistics. |

| 57 | Somerville (2015) | UK | LGBT staff's experiences in health & social care settings. | Stonewall‐commissioned survey of LGBT+staff in health & social care settings. Data analysis: not described. Reporting comprised descriptive statistics & themed analysis. |

| 58 | Sutter et al. (2020) | USA | Oncologists’ experiences of caring for LGBTQ cancer patients. | Questionnaire completed by 149 oncologists. Open ended questions, free‐text answers. Data analysis: qualitative ‐ inductive content analysis & 'constant comparison' method. |

| 59 | Swank and Raiz (2010) | USA | Social work students’ attitudes toward lesbian & gay individuals. | Questionnaire completed by 575 "completely heterosexual" students at 12 institutions. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 60 | Szél et al. (2020) | Hungary | Medical students' knowledge about 'homosexuality’ and attitudes toward LGBTQ people. | Questionnaire completed by 568 medical students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 61 | Unlu et al. (2016) | Turkey | Nursing students’ attitudes re gay men & lesbians | Questionnaire completed by 964 nursing students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 62 | Vinjamuri (2017) | USA | Social work students’ experiences of semester‐long course on social work with LGBT individuals & families. | Externally facilitated focus groups (13 participants). Recorded & transcribed data were analysed using grounded theory. |

| 63 | Wahlen et al. (2020) | Switzerland | Medical students’ attitudes towards/knowledge re. LGBT people and impact of training event. | Pre‐/post‐test surveys of 96 students who attended a lecture on sexual orientation & gender identity health issues. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 64 | Wang et al. (2020) | Taiwan | Nurses’ attitudes toward & knowledge about sexual minorities and providing them with care. | Questionnaire completed by 323 Taiwanese nurses. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 65 | Westwood (2017) | 4 countries | How older lesbian, gay, & bisexual (LGB) people engage with religion in later life. | Data subset of interviews with 60 UK LGB older people & 20 activists in Canada, USA, Australia & UK. Data analysis: thematic (Braun & Clarke, 2006). |

| 66 |

Willis et al. (2018) [Same dataset, Hafford‐Letchfield et al. (2018)] |

UK | LGBT+action research project with six care homes for older people to assess & develop services. | Evaluation, via telephone interviews, of action‐research intervention conducted by Data analysis: qualitative, methodology, not described. |

| 67 | Willis et al. (2017) | UK | Gauge the views, attitudes & knowledge levels of care & nursing staff, in relation to LGBT people. | Mixed methods: (1) Questionnaire 121 staff; 9 focus groups (practitioner/ policy stakeholders). Data analysis: questionnaire = quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis.; focus groups = qualitative ‐ themed analysis (type(s) not specified). |

| 68 | Wilson et al. (2014) | USA | Professional, demographic & training characteristics & health professions student attitudes toward LGBT patients. | Questionnaire completed by 475 healthcare students (mental health, medicine, nursing, dentistry, allied health sciences, e.g., dental hygiene, occupational therapy, physical therapy, & physician assistant). Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 69 | Woodford et al. (2021) | USA | Association between social work students’ LGB attitudes, religious teaching, own beliefs & religiosity. | Questionnaire completed by 253 incoming MSW students. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

| 70 | Woodford et al. (2013) | USA | Social work faculty's attitudes towards LGBT+people & associated sociodemographic factors. | Questionnaire completed by 161 social work faculty. Data analysis: quantitative ‐ descriptive & complex statistical analysis. |

The studies covered a range of professions, listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Professions/occupations included in the selected studies and staff/student status

| Professions/Occupations | Staff only | Students only | Staff & Students |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care home (‘long‐term care facility’) managers/staff | (2) (31) (33) (35) (50) (55) (66) | ||

| Medicine | (21) (24) (28)(37) (51) (52) (57) (58) | (27) (44) (48) (60) (63) | (9) (11) |

| Nursing | (6) (10) (17) (21) (28) (57) (64) | (1) (14) (23) (40) (47) (61) | |

| Nursing educators (‘faculty’) | (56) | (43) | |

| Occupational therapy | (1) (68) | ||

| Psychology | (1) | ||

| Social work | (21) (54) | (1) (4) (5) (7) (13) (20) (32) (36) (38) (46) (49) (59) (62) (69) | (41) |

| Social work educators (‘faculty’) | (19) (25) (26) (29) (70) | (45) | |

| Supported housing staff | (34) | ||

| Other (chaplain, counselling, dentistry, dental hygiene, laboratory technicians, physical therapy, physician assistant, ‘end‐of‐life service providers’ and/or other non‐specified health and social care workers ) | (8) (15) (21) (28) (51) (57) | (68) |

Of the 70 studies, over half (n = 38, 54%) were quantitative, applying descriptive and complex statistical analysis to questionnaire data from sample sizes ranging from n = 22 to n = >1000 participants. N = 10 (14%) studies employed a mixed methodology. Of these, n = 9 comprised questionnaire data which were both quantitative (analysed using descriptive and complex statistics) and qualitative (analysed using thematic analysis). One study comprised a questionnaire and focus groups. The remaining n = 22 (31%) studies were qualitative. N = 14 involved interviews with sample sizes between n = 8 and n = 77. N = 3 of the qualitative studies comprised focus groups, the total numbers of participants being n = 13, n = 30 and n = 15 respectively. A further study comprised reflective materials linked to a drama group (notes, memos, reflective diaries, in‐group discussions). N = 2 studies used free‐text response questionnaires. Another study involved secondary data analysis of a data set from a previous study. One of the qualitative studies involved website content analysis. The selected studies which analysed qualitative data using a range of thematic methodologies.

The selected studies used a range of validated and non‐validated measures for their empirical data collection. The validated measures are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Validated measures used in the selected studies

| Measure | Studies |

|---|---|

| Ageing Sexuality Knowledge and Attitude Scale (ASKAS) (Henrickson et al., 2021; White, 1982) | (33) (67) |

| Attitudes Toward Lesbian and Gay Men Scale (Herek, 1984; Herek & McLemore, 1998) | (8) (10) (17) (19) (49) (56) (59) (61) (64) |

| Attitudes Toward Transgendered Individuals Scale (ATTI) (Walch et al., 2012). | (28) |

| Discrimination and Stigma Scale (DISC−12) (Brohan et al., 2013) | (28) |

| Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) (religiosity) (Koenig & Büssing, 2010) | (47) |

| Francis−5 scale (Christian religiosity) (Cogollo et al., 2012) | (48) |

| Gay Affirmative Practice Scale (Crisp, 2006) | (10) (17) |

| Heteronormative Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (HABS) (Habarth, 2015) | (54) |

| Homophobia Scale (HS−7) (Bouton et al., 1987), Spanish version (Campo‐Arias et al., 2012). | (48) |

| Homophobic Attitudes Scale (Hudson & Ricketts, 1980), Turkish version (Sakallı & Ugurlu, 2001). | (6) |

| Homosexual Attitude Scale (Kite & Deaux, 1986), Malay version (Malay Version of the Homosexual Attitude Scale (MVHAS)) (Ng et al., 2015). | (47) |

| Index of Homophobia (Hudson & Ricketts, 1980), Korean version (Korean Index of Homophobia) (Kim & Bahn, 2005). | (40) |

| Knowledge about Homosexuality Scale (Harris, 1995) | (10) (17) (24) |

| Knowledge, Experience, and Readiness to Teach LGBT Health questionnaire (Lim et al., 2015) | (43) |

| Lesbian Gay Bisexual‐Knowledge Scale for Heterosexuals (LGBKASH) (Worthington et al., 2005). | (67) |

| Modern Homophobia Scale (Raja & Stokes, 1998). | (28) |

| MSATLG: Multidimensional scale of attitudes toward lesbians and gay men (Portuguese) (Gato et al., 2012). | (44) |

| Religious Fundamentalism Scale (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 2004), Italian version (Carlucci et al., 2013). | (28) |

| Sexual Prejudice Scale (SPS) (Chonody, 2013). | (20) |

| Sexual Male Chauvinism scale (Spanish) (Rodríguez et al., 2010) | (48) |

| Transphobia Scale (Nagoshi et al., 2008) | (1) |

4. ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS

4.1. Religious affiliation and negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people

Healthcare, social care and social work professionals and students affiliated with a religion are more likely, than those who are not, to have negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people, their lives and lifestyles. (1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 17, 19, 20, 21, 24, 26, 27, 28, 32. 34. 36, 40, 41, 44,45,46,47,48,49, 51, 55,56, 58, 59, 60, 61, 63, 67, 68, 70).

4.1.1. Qualified staff

Baiocco et al. (2021) compared the LGBTQ training needs of health and social care (staff in Cyprus, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Spain, Romania, and the UK), concluding, ‘The common elements that bind the countries with the lower tolerance and acceptance of LGBTQ people and the most negative attitudes about them are religion and patriarchy’ (p.11). Bennett et al. (2017), reporting on a study of nurse and allied health professionals’ attitudes towards “LGBTQ parents” seeking healthcare for their children in Australia, found a ‘significant association between knowledge scores and professional group, marital status, highest qualification, race, political voting behaviour [and] religious beliefs’ (p.1024).

Prairie et al. (2018), reporting on a survey of US physicians (and medical students), noted that physicians who identified circumstances when there might be a right to refuse treatment to LGBTQ people were informed by religious beliefs. However, ‘while some physicians cite religious freedom as a reason to deny medical treatment, other physicians speak to their religion as prohibitive of discrimination’ (p.548). Cloyes et al. (2020), in a US study of 122 hospice team members, observed that ‘being religious is associated with more negative attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities’ (p.2189). Ahrendt et al. (2017) , in the US, found that long‐term care staff working in a religious organisation had a “higher amount of stigmatization” (p.1513) towards a gay sexual relationship vignette than staff from a non‐religious organisation.

By contrast, Johnston and Shearer (2017), in a US study of 67 internal medicine residents, found an openness and willingness to treat trans patients among all but two of them. They suggested that this might reflect ‘cultural and legal shifts currently ongoing toward greater transgender awareness and advocacy’ (p.93). However, the authors also observed that only 57% of all the internal medicine residents participated in the study, and that there may have been a self‐selection process involved, with those residents with less accepting attitudes not participating in the study.

4.1.2. Students

Lopes et al. (2016) reported on a Portuguese study of 489 medical students. They found a correlation between religious students and negative attitudes towards ‘homosexuals’. Reporting on a study conducted with medical students in Serbia, Dunjić‐Kostić et al. (2012, p.148) observed that ‘the religious participants showed a lower level of knowledge … [and] more negative attitude towards homosexuals’. A study by Kwak and Kim (2019), of nursing students in South Korea, found ‘higher rates of homophobia in participants who were male, religious, did not have a family member or acquaintance who identified as a sexual minority, and who had low self‐esteem’ (p.4692). In the United States, Acker (2017), in a study of 600 undergraduate students majoring in social work, nursing, psychology, and occupational therapy, reported increased levels of transphobia among participants with a religious affiliation.

By contrast, Cornelius and Carrick (2015), again in the United States, reported that knowledge of and attitudes toward LGBTQ healthcare concerns among nursing students were not affected by religion. However, the authors noted that this might have been because they asked about LGBTQ healthcare concerns, not attitudes towards LGBTQ people themselves.

4.1.3. Type of religion

Many studies did not distinguish between religions or religious denominations. However, the religion most studied and/or present was Christianity. In the United States, Chonody et al. (2013) reported higher levels of ‘antigay bias’ among ‘completely heterosexual’ (p.217) Christian social work students compared with non‐religious social work students. Another US study of 215 social workers and social work students, conducted by Lennon‐Dearing and Delavega (2016), found ‘Christian religious affiliation to be associated with less accepting attitudes toward LGBTQ people when compared to non‐Christian faiths and people who are agnostic, atheist, or no religion’ (p.1183). Corrêa‐Ribeiro et al. (2018) reported from Brazil that Catholic and evangelical physicians ‘gave a significant lower number of correct answers (to an adapted version of the validated “Knowledge about Homosexuality” Questionnaire) compared with those who believed in other religions or who did not believe in any religion’ (p.1).

There were similar findings among studies in predominantly Muslim countries. Hatiboğlu et al. (2019) reported that religious Turkish social work students were more likely to prioritise religious beliefs over professional values, with some refusing to work with LGBTQ people on the grounds of religious objections. Two other Turkish studies whose respective samples were primarily Muslim, also reported higher levels of ‘homophobia’ (Aynur et al., 2020) and negative attitudes towards lesbians and gay men (Unlu et al., 2016) among Muslim nurses with religious affiliations. A study of nursing students in Malaysia (Ng et al., 2015) comprising a sample which was 95% Muslim, reported a high correlation between religious affiliation and ‘homophobia’.

Banwari et al. (2015), reporting from India on a study which aimed to assess medical students’ and interns’ knowledge about, and attitudes towards, ‘homosexuality’, observed that in their findings ‘religion affects knowledge, but not attitudes’ (p.11). However, 90% of their sample was Hindu, a religion which is not entirely negatively predisposed towards LGBTQ people. 6 Similarly, Wang et al. (2020), reporting from Taiwan, did not find a correlation between religious affiliation and negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people. The dominant religions in this study were Buddhism and Daoism, with only 9% of the participants identifying as Christian and none as Muslim.

4.2. Magnifying effects of religiosity

Religiosity – the frequency of religious participation (such as attendance of faith groups, reading religious texts and prayer) and depth of involvement in/identification with one's religion (Aksoy et al., 2022) – is reportedly a magnifier of negative attitudes towards, or what some studies described as ‘disapproval’ of, LGBTQ people. (1, 6, 10, 17, 20, 21, 26, 27, 28, 36, 44, 45, 47, 48, 49, 50, 56, 59, 60, 61, 63, 68).

Fisher et al. (2017), reporting on findings from an Italian study of healthcare providers, found that both homophobia and transphobia were associated with religious fundamentalism. Reporting on their study of 489 medical students in Portugal, Lopes et al. (2016) found that ‘religiosity correlated significantly with more negative attitudes toward lesbian and gay men’ (p.690). Wahlen et al. (2020), reporting on the attitudes of medical students in Switzerland, found that ‘students with active religious practice have less favorable scores’ (p.5) for knowledge about and attitudes towards LGBTQ people. A relationship between heightened religiosity and increased negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people was also reported by: Papadaki et al. (2013), in a study of 281 social work students in Crete; Ng et al. (2015), in a study of 495 Malaysian nursing students; Nieto‐Gutierrez et al. (2019), in study of 883 medical students in Peru; Prairie et al. (2019) in a study of 1376 US healthcare professionals; Jaffee et al. (2016) in their study of Canadian and US social work students; Dessel et al. (2012) and Chonody et al. (2014) in their respective studies of Canadian and/or US social work faculty.

Chonody et al. (2013), also in the United States, studied social work students’ attitudes towards lesbians and gay men, reporting a ‘relationship between religiosity and antigay bias’ (p.217). However, in this study, they painted a nuanced picture, in that it was not only religiosity but religiosity and a particular Christian denomination's approach to same‐sex individuals which was significant. Highly religious students whose religion took a positive approach to same‐sex sexualities were more likely to be accepting towards them than highly religious students affiliated with a religion which took a more strongly disapproving stance. The authors concluded that ‘both religious message and religiosity matter in students’ antigay bias’ (p.220).

Woodford et al. (2013), writing from the United States, found a correlation between religion, but not religiosity, and negative attitudes towards/disapproval of LGBTQ people, among social work students. Their sample of 161 students was ‘primarily female, heterosexual, White, and Christian’ (p.56). They were unsure whether this informed their findings, which contradicted both their hypotheses and the wider literature. However, in a more recent study, Woodford et al. (2021) did find religiosity to be of significance: religion affected scores on the ‘Affirming Attitudes Towards Sexual Minorities Scale’ (AATSMS) and this was further compounded by religiosity. Woodford et al. (2021) also differentiated between denominational teachings, reporting that,

…students belonging to denominations teaching that same‐sex sexuality is not a sin tended to report significantly higher AATSMS scores than those belonging to denominations teaching that it is a sin (p.10).

Woodford et al. also noted the mediating role of a student's own belief system, ‘the effect of denominational teachings depends on one's personal endorsement of those teachings and the importance of religion in one's life (and vice versa)’ (p.12).

There have been some suggestions that there is an interaction between race/ethnicity, religiosity and negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people. Chapman et al. (2012), writing from Australia in relation to nursing and medical students, noted that.

Caucasians, supporters of less conservative political parties, those who reported no religious beliefs, those who reported not attending religious services weekly and those who had a friend who is openly LGBT had significantly higher knowledge scores [about LGBT people]. (p.940)

Baiocco et al. (2021), reporting on research in seven European countries, observed that ‘both religion and patriarchy are tightly bound with the collective culture of national identities’ (p.11). Vinjamuri (2017), writing from the United States in relation to social work students, noted that their religious‐based attitudes towards LGBTQ people were informed by the cultural backgrounds, and that this could pose challenges for overseas students. Jaffee et al. (2016), reporting on research with social work students in Canada and the United States, noted ‘the importance of intersections between race/ethnicity and religion’ (p.265), particularly in relation to African American students with negative attitudes towards/disapproval of LGBTQ people. They also observed that.

Racial minorities in religious communities have traditionally been less likely to hold affirming attitudes toward gay and lesbian people; such communities often oppose same‐sex sexuality and reinforce traditional gender norms and procreation… These teachings may shape the views of social work students affiliated with these religious communities. (p.265‐6)

This is not to suggest that race/ethnicity is inherently linked to negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people, many of whom are people of colour themselves (Balsam et al., 2011). The suggestion is, instead, that for some people from certain racial/ethnic backgrounds, their initial cultural/religious reference points may involve negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people (Aihiokhai, 2021; Jaspal, 2016; Standford, 2013; Yip, 2012).

4.3. Education and training

4.3.1. Educators’ attitudes

Concerns were raised in relation to religious attitudes within teaching faculty and/or on placement (11, 19, 25, 26, 29, 36, 38, 43, 70). Dessel et al. (2012), in the United States, reported that Christian social work faculty's views towards lesbians and gay men were ‘significantly less accepting than those with no religious affiliation’ (p.251). Lim et al. (2015), in a US study of nursing faculties’ knowledge and readiness to teach about LGBTQ health, reported that the dean of one school refused permission for his staff to participate in the study because ‘the survey is not congruent with our ethical and religious directives’ (p.251). Investigating the experiences of trainee social workers in Canada and the United States, Messinger et al. (2020) reported that one non‐heterosexual social work student on placement was told to keep their sexual orientation ‘a secret’ (p.713) and another student experienced an internship co‐worker ‘bringing in very derogatory and offensive religious literature for me to read’ (p.714). Austin et al. (2016) reported on widespread trans microaggressions (everyday, often unintentional, negative words or actions and/or omissions) described by US trans social work students. They found no difference between students based at religious educational institutions and those based at public ones. However, the students’ comparative institutional profiles were not described. By contrast, Byers et al. (2020), reporting on a study involving Canada and the United States which examined social work students' experiences of homophobic and transphobic noted the following accounts from social work students in the United States:

I have a professor who, when one student brought in information about a gay marriage (pro) rally, made a point to say that not everyone agrees and that the school isn’t affiliated with the rally. Then basically backed up his side with his religion.

We had an instructor who made it clear that he was uncomfortable with homosexuality because of his religion. He advocated for students to not put themselves in uncomfortable situations if they feel the same way.

Professors hesitate to condemn the opinions of evangelical Christian students. (p.385)

They observed:

Students may interpret instructors’ mixed messages as an invitation to express homophobic and transphobic views. One participant [a Canadian student] was discouraged from filing a grievance about another student because ‘nothing would happen to him based on his freedom of religion.’ (p.385)

Atteberry‐Ash et al. (2019) study of 12 LGBTQ social work students in the United States reported that nine of them described experiences of ‘being excluded, dismissed, or minimized based on other students’ religious identification’ (p.230). By contrast, Barker’s (2013, p.17) study of Christian social work students in the United States reported that they themselves felt excluded by liberal political ideology in social work programmes.

Sirota (2013), reporting on a survey of 1282 US nurse educators’ attitudes towards lesbians and gay men, found that Muslim and evangelical Christian nurse educators had higher than average negative attitudes towards ‘homosexuals’, compared with students from other religious affiliations and no religious affiliations. This was compounded by religiosity.

One study reported a contrary finding. Fredriksen‐Goldsen et al. (2011), reporting on a survey of US and Canadian social work students, did not find a correlation between religious students and negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people. They suggested that some of their respondents might have been ‘affiliated with progressive religious communities’ (p.30).

4.3.2. Supporting reflective dialogue

Several of the studies commented on the importance of promoting reflective dialogue with religious students and practitioners (1, 26, 36, 38, 62, 69). In terms of students, Acker (2017) observed in relation to trans issues that:

Students have to be encouraged to recognize how their attitudes and knowledge about transgender persons may affect their future clinical practice. Small‐group discussions and multimethod teaching such as role playing can be beneficial in dealing with students’ religious beliefs. (p.2024)

Joslin et al. (2016) reported from the United States on a facilitated intergroup dialogue between Christian‐LGB (n = 2), secular‐LGB (n = 3) and Christian heterosexual (n = 5) social work students. The authors observed ‘supportive, facilitated spaces that enable “difficult conversations” about sexuality, religion, and other controversial issues are needed within social work programs’ (p.553). However, their initiative was not wholly successful. The Christian LGB students reported experiencing greater validation from their Christian heterosexual counterparts, who in turn felt that their knowledge and understanding of LGB issues had improved. However, the Christian heterosexual students felt that their experience of religious oppression were not validated by the group, while the secular LGB students, in the minority, felt that the Christian heterosexual students dominated the discussions from which they then withdrew. The authors concluded that there were ‘missed learning opportunities for all students, especially concerning intersectionality’ (p.551).

Vinjamuri (2017), writing in the United States, described how some overseas students went through a process of reviewing their religious cultural norms, particularly in relation to LGBTQ issues, during social work training, and that doing so ‘was a painful process for some students’ (p.154). Holman et al. (2020) reported on the efficacy of LGBTQ‐diversity training designed to improve older age housing staff's cultural competency. They observed that the Christian participants ‘had lower post‐intervention content knowledge and lower post‐intervention supportive attitudes’ (p.11).

Westwood and Knocker (2016), from the UK, quoted trainers who had encountered religious‐based resistance from trainees:

One woman said that if her daughter was lesbian she’d have to “exorcize the demon out of her” and another man just starting from the point of “where does this perversion come from?” on the training and then wanting to go into the whole spiel about how the male and female anatomy are meant for each other. (Joy, UK Activist) (p.18)

It can be hard . . . you know one guy came in and said, “what causes this perversion,” and I’ve been prayed over, and there’s been this uprising in the room with people saying, ‘Oh if my daughter was . . .’ and all this gay conversion stuff, and it’s been pretty, pretty tough, yeah. But… you’ve got to hear the hatred, actually, and sort of expose it, rather than it just staying as subtext. (Sarah, UK activist/ trainer) (p.18)

This quote highlights two key issues: firstly, the importance of facilitating open dialogue and encouraging students and staff to reflect on how their personal (religious) beliefs might impact their practice; secondly, the importance of identifying those students and staff who may hold intransigent negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people likely to undermine equitable service delivery, and the need to address these via professional practice standards and procedures.

4.4. Practice concerns

4.4.1. Professional concerns

There is a dearth of evidence about how religious‐informed attitudes towards LGBTQ people translate into practice. Carabez et al. (2015), reporting on a US study of nursing students, evaluated an LGBTQ teaching intervention, observing that more than 10% of the 112 participants ‘had religious values that might interfere with quality care’ (p.51). However, how they might interfere was not explained. Similarly, Aynur et al. (2020, p.1918) reported that many religious nurses in Turkey were ‘uncomfortable’ providing care to LGBTQ people, but how this affected practice was not discussed. Johnston and Shearer (2017, p.92), in the United States, noted that two medical residents (3% of the total sample) reported ‘that they would feel uncomfortable treating a transgender patient for personal, moral, or religious reasons’. Again, how this might affect practice was not explored.

Lennon‐Dearing and Delavega (2016, p.1184), reporting on a US study of social workers and student social workers, observed that among religious staff working with LGBTQ people, ‘professional standards may not always be followed, and… words of compassion may not necessarily be followed by similar actions’. They did not elaborate further on this, other than reporting religious participants’ support for proposed laws which would allow conscientious objection to delivering services to LGBTQ people. Support for conscientious objection was also raised by religious participants in US studies conducted by Prairie et al. (2018) and Sutter et al. (2020). Only one study involved explicit statements of conscientious objection: Hatiboğlu et al. (2019, p. 154) described a student stating ‘I can't work with LGBT people because of my religion’.

Pelts and Galambos (2017), again in the United States, reported that long‐term care staff thought ‘…religions that have a history of negative views toward sexual minorities may influence care provision’ including services provided to lesbians and gay men, either through organisational cultures and/or individual staff perspectives’ (p.577). However, how this might influence care provision was not addressed. Willis et al. (2017), reporting from the UK on attitudes towards LGBTQ people among care and nursing staff in long‐term care facilities for older people, found ‘ambivalent attitudes towards sexual diversity on the basis of religious faith’ (p.421). Apart from a reluctance to display gay pride symbols, however, how this might impact practice was not addressed.

By contrast, de Jong (2017) reported mixed findings from a US study which explored Christian social work faculty members' attitudes towards ‘transgender and gender‐variant students’ (p.55). While the authors observed that ‘the data indicate largely positive attitudes and a willingness to engage with trans issues’ (p.65), other aspects of the data were less in alignment with this, notably in relation to conversion therapy suggesting as de Jong observed, there was ‘some reluctance to fully embrace gender diversity’ (p.78). One possible explanation is that Christian social workers may believe in trans equality in principle, but may find it harder to envisage it in practice.

In the UK, Simpson et al. (2016) found that 20% of Christian long‐term care staff expressed disapproval of same‐sex relations compared with 14% per cent of nonbelievers, which is only a small (6%) margin difference. Two‐thirds thought that their beliefs would not affect their ability to accept LGBTQ residents, although many thought that they would have to suppress their beliefs to do so. Again how, and in what way, they would need to suppress their beliefs was not described.

Similarly, Howard et al. (2020), reporting on a Canadian study which explored how managers navigate resident sexual expression in long‐term care homes observed,

One participant noted, “a lot of the discomfort [about sexual expression] comes from minimally trained care workers from very religious backgrounds with conservative views about sexuality and managers have to work through all of that” [Participant 20]. (p.636)

However, again, no examples were given of how this might impact practice, nor what issues managers might have to ‘work through’ with some staff.

4.4.2. LGBTQ people's concerns about faith‐based care

Some LGBTQ people, especially older individuals, are concerned about receiving faith‐based care which may be heteronormative, cisnormative and/or disapproving of them (3, 12, 15, 16, 22, 30, 33, 39, 42, 53, 65). Leung (2016) reported from Hong Kong on a small‐scale study of the barriers experienced by lesbians and gay men who have experienced same‐sex intimate partner violence (SSIPV) in obtaining help from social services. Leung observed that ‘nearly all of the respondents mentioned that social workers were not trusted by LGBT survivors because most social workers have a religious background’ (p.2406). Leung noted that LGBTQ survivors of abuse avoid domestic abuse services because of this.

In the UK, research conducted by the British Medical Association (2016) on attitudes towards LGB doctors and medical students found that although many were ‘openly gay’, they ‘expressed nervousness about the attitudes towards homosexuality that are perceived to be held by the holders of some religious beliefs. This fear was amplified when the person with religious belief was the interviewee's professional superior’ (p.12). Also in the UK, Guasp (2011), reporting on a survey of older LGB people, quoted the following participant,

There is a severe lack of understanding about the particular needs of older lesbian and gay people, especially from some faith‐based organisations that provide care services." (John, 57, London, UK) (p.11)

Similarly, Robinson (2016), reporting on his international study of older gay men, quoted one of the Australian participants who said that:

Nursing homes in Australia are often run by church organisations. Some church organisations, though not all, are not particularly welcoming to gay residents. They are not particularly understanding of the diversity of human relationships and of their needs […] [We need] to make retirement homes more welcoming […] but because of the age of people in nursing homes they will have grown up in Australia in a time when there was not great knowledge and even less sympathy for gay people. (p.11)

Westwood (2017), reporting on a study of UK LGB older people and older LGBTQ activists in Australia, Canada, the UK, and the United States, quoted the following research participants who expressed concerns about long‐term care facilities/care homes:

I think a lot of the care homes are run by faith institutions of some sort who could be very homophobic indeed. (Tim, age 52) (p.20)

[I am frightened] that I would encounter homophobia, because all kinds of people work in care, from like fervent Filipino Catholics to young people who are not particularly educated, you know? So yes, that would make me apprehensive. (Rene, age 63) (p.20)

One of Knocker’s (2012) respondents, in her study of UK older LGB people, commented,

To send a religious fundamentalist care worker to visit a gay man is like sending a member of the BNP 7 to a black person. (Spike, older gay man) (p.10)

Knocker (2012) also quoted the following respondent:

In one doctor’s surgery, there were Jesus posters over the wall. I don’t think it is appropriate to bring religion into the workplace, into a public workplace. I would like these kinds of public places to be neutral places. They can practice what they like at home, but I don’t want to know. (Older lesbian woman) (p.10)

Echoing this, a UK‐based systematic review of the literature on sexual orientation disclosure in healthcare (Brooks et al., 2018) found that ‘military and religious‐affiliated settings were seen as impeding disclosure’ (p.e187). The review also observed that several studies had reported that while pro‐ LGBTQ visual markers (leaflets, stickers, posters, rainbow symbols) in healthcare settings facilitated disclosure, by contrast, religious symbols or icons were barriers to disclosure. Chaze et al. (2019), reporting on their review of the websites of 100 long‐term care homes (‘LTCHs’) in Canada, also observed:

For the most part, information available on the websites of LTCHs reviewed in this study suggested that the homes seemed to provide primarily Christian spiritual services. Older adults of other faiths or those with negative experiences with Christianity may feel marginalized or uncomfortable by this. (p.32)

Data from care home residents themselves are rare. However, Henrickson et al. (2021, p.10), reporting on their study of attitudes of long‐term residential care staff, residents, and family members towards 'sexually diverse' people, described the following conversation with a male resident:

There was an assumption by some resident participants that new settler staff would probably have difficulty with same‐sex couples because of their religious or cultural norms:

Q: Your sense is though, without really knowing, that if there was a gay person or couple, that that would be supported by staff members?

A: Possibly. I don’t know whether that would challenge some of them. Given they’re a very high proportion of people from the Philippines, I don’t know how the Filipinos would deal with it, because it’s a strongly Catholic country […]. (R4M) (p.166)

Again, while there are concerns about faith‐based organisations and/or practitioners potentially being discriminatory towards LGBTQ people, actual practice examples are rare.

4.4.3. Poor practice with LGBTQ adults by people with fundamental religiosity

There were a small number of anecdotal accounts of poor practice involving religious staff. Almack et al. (2010) and Westwood (2017) described disenfranchised grief experienced by bereaved partners in same‐sex couples, either by hospital‐based clergy or spiritual leaders who had not acknowledged their relationship. Cartwright et al. (2012) described a trans woman with dementia being made to live as a man in an Australian care home run by a religious charity. Coolhart and Brown (2017) reported that homeless LGBTQ young adults were being told by staff in a US shelter to ‘get on their knees and repent’ (p.234). Butler (2017, p.389) reported that an older lesbian couple receiving home care in the United States said that they had ‘a bible tract left on our bed [by a home care worker] that said homosexuality was a sin’. Cele et al. (2015, p.5) described a lesbian in South Africa being told by a nurse that ‘I need to go to church and pray because what I am doing is against God's will’.

A UK study on the treatment of LGBTQ staff within health and social care services quoted a gay nurse in the UK who said, ‘I was told I should be hanging from a tree by a nurse from Nigeria with strong religious beliefs’ (Somerville, 2015, p.6). Knocker (2012, p.10) reported that a disabled lesbian in the UK told her of ‘being given leaflets by religious care workers suggesting that she could be “saved”’. Hafford‐Letchfield et al. (2018) reported the following experience of one of their UK community action researchers [“CA”s] delivering LGBTQ training to staff working in long‐term care:

One staff member declared to a CA that they “knew how to deal with that disease’ and ‘One woman [care staff member] stated she would ban her son from the house if he came out as gay.’ (p.e318)

They commented:

This observation suggests, despite emphasis on person‐centred care, persistence of ingrained homophobia and partial tolerance of LGBT individuals in a setting where care is provided for vulnerable, older individuals. Such anxieties were animated by tensions between religious beliefs and sexuality (p.e318)

Such anecdotal evidence is not necessarily indicative of a large‐scale problem, and, of course, it would be possible to identify poor practice not linked to religious beliefs. However, there is a clear need to understand how negative faith‐based attitudes towards LGBTQ people translate into practice.

5. CONCLUSION

The nature of a scoping study is that selected studies are not reviewed for quality and so the comparative merits of the selected studies were not addressed. However, while they varied in approach, and in the use of validated/non‐validated measures, most of the studies described detailed methodologies of considerable rigour, suggesting that a high standard of empirical procedures was involved. A disproportionate number of studies were conducted in the United States, and in parts of the United States where traditional religious attitudes and high disapproval of LGBTQ people prevail (Lim & Hsu, 2016) which may have skewed the findings to some extent. It should also be borne in mind that LGBTQ people are not a homogenous group (Westwood, 2020) and there may be greater/lesser/different types of religious prejudice towards some sub‐groups compared with others, which most of the selected studies did not explore.

Nevertheless, the literature does suggest, across a wide range of contexts and countries, that there is a key problem concerning fundamentalist expressions of religion in healthcare, social care and social work contexts, with associated implications for the equitable delivery of services to LGBTQ people. Ethically, there are issues of compelled speech (Oleske, 2020) and whether those religious professionals with faith‐based objections to LGBTQ people should be required to deliver affirmative services to them, when they hold beliefs which are not in alignment with an affirmative approach. Practically, there is the crucial question of whether religious practitioners are able to do so, and to comply with relevant professional standards, particularly in relation to anti‐oppressive practice, as is mandated in UK and international social work standards (Cocker & Hafford‐Letchfield, 2014). To require high religious individuals whose religious beliefs cause them to consider LGBTQ people to be sinful and/or to be opposed to LGBTQ rights (Ngole, 2016), to authentically celebrate LGBTQ people, their lives and relationships, and to advocate for those same rights, would seem to be a very big ‘ask’ (Westwood, 2022). It would likely create considerable cognitive dissonance and associated workplace tensions for the practitioner (Crisp, 2017; Dessel et al., 2011; Héliot et al., 2020) while also falling short of proactive LGBTQ‐inclusive service delivery.

This is ‘an “uncomfortable” subject which is often ignored in analyses of social care diversity policies’ (Carr, 2008, 113). However, it is one which must now be addressed in policy and in practice. There are growing calls for the increased inclusion of LGBTQ issues in healthcare, social care and social work education curricula (Burton et al., 2021; Hunt et al., 2019; O’Leary & Kunkel, 2021). Many of the studies recommended promoting reflective dialogue among religious students and practitioners (Acker, 2017; Aihiokhai, 2021; Dessel, 2014; Joslin et al., 2016; Vinjamuri, 2017). Such initiatives would necessitate educators feeling sufficiently skilled and confident to promote reflective dialogue, and to explore issues with those students who may be experiencing tensions between their personal beliefs and professional requirements, including in relation to LGBTQ‐inclusive and affirmative practice (Mason et al., 2020). This is particularly important, given that several studies have suggested that highly religious students/staff can be resistant to taking a critical/reflective approach to their religious beliefs, and to associated training/education initiatives (Dessel et al., 2012; Hardacker et al., 2014; Vinjamuri, 2017; Westwood & Knocker, 2016).

There is presently a lack of research into how beliefs translate into practice, and an urgent need for research which specifically explores how attitudes towards LGBTQ people, including religious attitudes (positive and negative), shape the delivery of care and welfare support to them. Given responses to religious doctrine are highly individualised and open to interpretation (Valentine & Waite, 2012), it will be important to learn from highly religious practitioners who work successfully with LGBTQ people, how they are able to do so. This in turn could help inform training, educational and reflective practice initiatives with other religious students/practitioners.

This scoping study has mapped the terrain of the literature on religious attitudes towards LGBTQ people and has highlighted concerns relating to individuals with highly religious, fundamentalist, beliefs. Much more work needs to be done to fill the outstanding knowledge gaps in this area, particularly in terms of how religious attitudes inform practice, and what needs to be done, within this context, to ensure that the delivery of services to LGBTQ people is equitable, non‐judgemental, affirmative and free from religious censure.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their very helpful feedback on an earlier version of this article, and to Rhiannon Griffiths, for her excellent post‐data selection and analysis research assistance.

Westwood, S. (2022). Religious‐based negative attitudes towards LGBTQ people among healthcare, social care and social work students and professionals: A review of the international literature. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30, e1449–e1470. 10.1111/hsc.13812

ENDNOTES

Dr David Mackereth v The Department for Work and Pensions and Anor [2019] ET 1,304,602/2018.

R (Ngole) v The University of Sheffield [2019] EWCA Civ 1127.

Cornerstone (North East) Adoption And Fostering Service Ltd, R (On the Application Of) v The Office for Standards In Education, Children's Services And Skills [2020] EWHC 1679 (Admin) (07 July 2020) [2021] PTSR 14, [2020] WLR(D) 396.

Cornerstone, Honourable Mr Justice Julian Knowles, Para 2.

Ibid.

Human Rights Campaign (Undated) Stances of Faiths on LGBTQ Issues: Hinduism. (Online) https://www.hrc.org/resources/stances‐of‐faiths‐on‐lgbt‐issues‐hinduism

The BNP is the British Nationalist Party, a far‐right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Acker, G. M. (2017). Transphobia among students majoring in the helping professions. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(14), 2011–2029. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1293404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrendt, A. , Sprankle, E. , Kuka, A. , & McPherson, K. (2017). Staff member reactions to same‐gender, resident‐to‐resident sexual behavior within long‐term care facilities. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(11), 1502–1518. 10.1080/00918369.2016.1247533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aihiokhai, S. A. (2021). Black theology in dialogue with LGBTQ+ persons in the Black Church: Walking in the shoes of James Hall Cone and Katie Geneva Cannon. Theology and Sexuality, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, O. , Bann, D. , Fluharty, M. E. , & Nandi, A. (2022). Religiosity and mental wellbeing among members of majority and minority religions: Findings from understanding society: The UK Household Longitudinal Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 191(1), 20–30. 10.1093/aje/kwab133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan, H. T. (2021). Reflections on whiteness: Racialised identities in nursing. Nursing Inquiry, e12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan, H. , & Westwood, S. (2016). English language skills requirements for internationally educated nurses working in the care industry: Barriers to UK registration or institutionalised discrimination? International Journal of Nursing Studies, 54, 1–4. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almack, K. , Seymour, J. , & Bellamy, G. (2010). Exploring the impact of sexual orientation on experiences and concerns about end of life care and on bereavement for lesbian, gay and bisexual older people. Sociology, 44(5), 908–924. 10.1177/0038038510375739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer, B. , & Hunsberger, B. (2004). A revised religious fundamentalism scale: The short and sweet of it. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 14(1), 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]