Abstract

Background

An increasing number of children have complex care needs (CCN) that impact their health and cause limitations in their lives. More of these youth are transitioning from paediatric to adult healthcare due to complex conditions being increasingly associated with survival into adulthood. Typically, the transition process is plagued by barriers, which can lead to adverse health consequences. There is an increased need for transitional care interventions when moving from paediatric to adult healthcare. To date, literature associated with this process for youth with CCN and their families has not been systematically examined.

Objectives

The objective of this scoping review is to map the range of programmes in the literature that support youth with CCN and their families as they transition from paediatric to adult healthcare.

Methods

The review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute's methodology for scoping reviews. A search, last run in April 2021, located published articles in PubMed, CINAHL, ERIC, PsycINFO and Social Work Abstracts databases.

Results

The search yielded 1523 citations, of which 47 articles met the eligibility criteria. A summary of the article characteristics, programme characteristics and programme barriers and enablers is provided. Overall, articles reported on a variety of programmes that focused on supporting youth with various conditions, beginning in the early or late teenage years. Financial support and lack of training for care providers were the most common transition program barriers, whereas a dedicated transition coordinator, collaborative care, transition tools and interpersonal support were the most common enablers. The most common patient‐level outcome reported was satisfaction.

Discussion

This review consolidates available information about interventions designed to support youth with CCN transitioning from paediatric to adult healthcare. The results will help to inform further research, as well as transition policy and practice advancement.

Key messages.

The transition from paediatric to adult care is a critical period for youth with complex care needs (CCN).

Literature on transition interventions have not been systematically examined as a whole across different conditions or with a focus on programme characteristics.

This review maps a range of programmes in the literature that support youth with CCN and their families transition to adult care.

Findings from this review generate recommendations for practice, education and research advancement.

1. BACKGROUND

In North America, approximately 20% of children and youth with complex care needs (CCN) have substantial needs that require significant medical, cognitive, and/or educational assistance beyond what is generally required by their peers (Berry et al., 2011; Canadian Association of Pediatric Health Centres [CAPHC] & National Transitions Community of Practice, 2016; Dewan & Cohen, 2013; Kaufman & Pinzon, 2007; United States Census Bureau, 2018). Advances in healthcare and technology have increased the lifespan and quality of life of youth with CCN, allowing more children to live into adulthood (Dewan & Cohen, 2013). As a result, there is an increased need for transitional care interventions for these youth when moving from paediatric to adult healthcare.

The process of transitional care is complex and addresses psychosocial, medical, educational, vocational, and recreational needs, with the aim to improve continuity of care (Levy et al., 2020; Shaw & DeLaet, 2010). Although many youth experience healthcare transitions in some form, the transition from paediatric to adult healthcare is a critical concern for youth with CCN (Fernandes‐Alcantara, 2010; Fernandes‐Alcantara, 2014; McManus et al., 2008; National Research Council, 2015; Wang et al., 2010). The transition process is fraught with barriers due to the maze of health systems and myriad of care providers and specialists (National Research Council, 2015). This transition is often disjointed, which can further result in adverse health consequences and increased morbidity and mortality (Crowley et al., 2011; Park et al., 2006; Park et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2018; Stroud et al., 2015). Failure to successfully transition to needed services in the adult sector has been shown to lead to (1) higher utilization of emergency rooms (National Research Council, 2015); (2) negative experiences of care for patients, caregivers and health professionals (Heath et al., 2017; McManus et al., 2008; National Research Council, 2015; Rutishauser et al., 2014; van Staa et al., 2011); 3) poor access to care, including dental health and mental healthcare (McManus et al., 2008; National Research Council, 2015; Rutishauser et al., 2014; van Staa et al., 2011); (4) fragmentation of care (Gauvin et al., 2014; Kodner, 2009; National Research Council, 2015; Rich et al., 2012); and (5) deterioration of health due to lack of follow‐up visits or the emergence of mental health conditions (Lee et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011; National Research Council, 2015).

A preliminary literature search showed numerous studies published on transition programs for youth with CCN moving to adult healthcare, which continues to be a growing field (Breneol et al., 2017; Canadian Association of Pediatric Health Centres [CAPHC] & National Transitions Community of Practice, 2016; Crowley et al., 2011; Dewan & Cohen, 2013; Fernandes‐Alcantara, 2010; Fernandes‐Alcantara, 2014; Levy et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2018; Stroud et al., 2015; United States Census Bureau, 2018). However, to our knowledge, there has yet to be an overarching systematic examination of transition programmes for this population as a whole. To date, previous reviews primarily concentrated on specific conditions (e.g. diabetes and cystic fibrosis) and focused on the barriers, needs, facilitators, and/or outcomes of transition programs, interventions or innovations (Bhawra et al., 2018; Blum et al., 1993; Campbell et al., 2016; Colver et al., 2013; Coyne et al., 2017; Crowley et al., 2011; Gabriel et al., 2017; Hart, Patel‐Nguyen, et al., 2019; Mora et al., 2016; Naert et al., 2017; Rutishauser et al., 2014). Although there are several reviews that examine the area of transition (Fernandes‐Alcantara, 2014; Kutcher et al., 2010; Mulvale et al., 2015; Paul et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2018; Stroud et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2010), generalizable findings have been difficult to extract, as the focus was narrowed to specific populations; the interventions and outcome measures were heterogeneous; or the descriptions of context limited. The current review focuses more broadly by synthesizing evidence that can be used to inform future research by a wider array of scholars. By looking more broadly, this review is able to identify common findings across populations with differing conditions, which adds further support to the evidentiary base.

This scoping review reports on the second of two objectives outlined in a larger project exploring all transitional care programs for youth with CCN (Doucet et al., 2020), specifically, transitions in care from paediatric to adult healthcare. Findings from the first objective are reported in a separate (forthcoming) publication, which is focused on transitions in care from hospital to home and/or between community settings for children and youth with CCN up to the age of 19 years old.

2. REVIEW OBJECTIVES AND QUESTIONS

The objective of this scoping review was to map the range of programs in the literature that support youth with CCN and their families as they transition from paediatric to adult healthcare. The following research questions were addressed:

What programmes are reported in the literature to support youth with CCN and their families during the transition from paediatric to adult healthcare?

What are the reported key components and/or characteristics of the transitional care programs for youth and their families?

What are the reported barriers and enablers to the implementation of transitional programmes for youth with CCN and their families?

What are the reported outcome measures and evaluation methods of transitional programmes for youth with CNN and their families?

3. METHODS

Scoping reviews, a type of knowledge synthesis, can help address exploratory research questions aimed at mapping and organizing what is known about a specific phenomenon (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015; McGowan et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2015; Tricco et al., 2018). As such, our research team conducted a scoping review to provide a better understanding of the range of transition programs described in the literature and to report on the characteristics and components of these programmes, including any barriers and facilitators to their implementation.

Conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2015; Peters et al., 2015), we followed the nine steps within this framework. Before starting the review, a local advisory council was established, composed of key stakeholders, such as researchers, patients, caregivers, and librarians, to oversee project milestones. For additional information on the review methods, refer to the published protocol (Doucet et al., 2020). Ethics approval was not necessary given that this synthesis is a review of published and publicly reported literature.

3.1. Searching and selecting the evidence

An experienced library scientist undertook an initial limited search of PubMed and CINAHL to identify index terms and keywords to develop a comprehensive search strategy in each database. To ensure that the search strategy was optimally designed to capture all relevant literature, a second library scientist reviewed the search strategy using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) Guideline Statement (McGowan et al., 2018). The search strategy was then adapted for each relevant database, and a final strategy was implemented into five electronic databases: PubMed, CINAHL, ERIC, PsycINFO and Social Work Abstracts. Given the broad scope of this review, grey literature was not included and will be a focus for future work. The last search of the literature was conducted 29 April 2021, and the search strategy for PubMed is included in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Search strategy for PubMed

| # | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | (‘health transition’ OR ‘transition care’[All Fields] OR ‘transitional care’[All Fields] OR ‘transitional services’[All Fields] OR ‘transition planning’[All Fields] OR ‘continuity of patient care’[All Fields] OR ‘continuity of care’[All Fields] OR ‘care coordination’[All Fields] OR ‘transition to adult’ OR ‘transitional program’ OR ‘Transition to Adult Care’[Mesh] OR ‘transition’[title/abstract]) |

| #2 | ((‘complex’[All Fields] OR ‘comprehensive’[All Fields] OR ‘complexity’[All Fields] OR ‘medically fragile’[All Fields] OR ‘multiple chronic’[All Fields] OR ‘Multiple Chronic Conditions’[Mesh]) AND (‘intervention’[All Fields] OR ‘programs’[All Fields] OR ‘patient care planning’[All Fields] OR ‘community integration’[All Fields] OR ‘models of care’[All Fields] OR ‘disease management’ OR ‘transition services’ OR ‘care coordination’)) |

| #3 | (‘adolescent’[All Fields] OR ‘youth’[All Fields] OR ‘pediatric’[All Fields] OR ‘adolescence’ OR ‘juvenile’ OR ‘youth’ OR ‘teen’ OR ‘teenager’ OR ‘pubescent’ OR pediatrics[mh] OR ‘paediatric’ OR ‘minors’ OR ‘boy’ OR ‘boys’ OR ‘girl’ OR ‘kid’ OR ‘kids’ OR ‘child’ OR ‘children’ OR ‘schoolchildren’) |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 and #3 |

3.2. Inclusion criteria

3.2.1. Participants

This review considered literature on youth with CCN and/or their families (e.g. parents, guardians, or others caring for a child/youth) engaged in programmes to support their transition from paediatric to adult healthcare. CCN was defined as health and social care needs in the presence of a recognized condition, with or without a diagnosis (Brenner et al., 2018).

3.2.2. Concept

This review's concept of interest was transitional care programs. Transitional care programmes included any intervention, service(s), or set of activities with a goal to support the movement of youth and their families from paediatric to adult healthcare services. These programs could be delivered in person or remotely, by professional or lay individual(s) (e.g. peer navigators) that targeted youth, and/or their families with the goal of improving transitions in care. Articles that did not explicitly state their intent to support this transition process were excluded.

3.2.3. Context

The review considered articles where transition programmes were delivered in any setting in the youth's community (e.g. home and school), neighbouring communities or healthcare institution (e.g. primary care and tertiary care). Articles describing transitional care programmes delivered by a range of approaches (e.g. e‐health and clinic‐based) were included. However, literature describing programmes that were delivered to support transitions exclusively within a hospital setting with no community component were excluded, as were programmes for individuals residing in long‐term care facilities. An intrafacility handover is an example of a transition exclusively in a hospital setting involving individuals who are institutionalized, for example a youth transitioning from a paediatric to adult hospital unit. There were no geographic or temporal limitations placed on the review to allow for the examination of any potential trends in transitional care programmes across time.

3.3. Types of sources

This scoping review considered all published article types (excluding reviews), including quantitative studies, qualitative studies, mixed methods studies, descriptive reports, and study protocols if sufficient information was provided to discern programme characteristics. Systematic, scoping, and literature reviews were not considered for inclusion in this review; however, the reference lists of relevant reviews were screened for additional articles. This review included articles published in the English and French languages.

3.4. Article selection

Screening for study selection occurred in two stages: (1) title and abstract and (2) full text. All citations identified by our search strategy were uploaded into Mendeley and duplicates removed. Remaining citations were then imported into Covidence Systematic Review Software and any remaining duplicates removed. Two independent reviewers screened all titles and abstracts for assessment against the eligibility criteria. For the second stage of screening, full texts of all potentially relevant citations were imported into Covidence software (Covidence Systematic Review Software, 2018). Two independent reviewers assessed the full text of each selected citation in detail against the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer. Note that some individuals involved in screening, and data extraction are not authors on the manuscript. Quality appraisals were not conducted as they are not required for scoping reviews.

3.5. Data extraction and analysis

Two independent reviewers extracted data from the articles using a data extraction tool developed a priori by the research team. Extracted data included specific details about the article characteristics, transition programme characteristics, and reported barriers and enablers to implementation. The reviewers resolved any disagreements that arose through discussion to achieve consensus. Qualitative descriptive content analysis was used to code characteristics into overall categories (Mayring, 2000; Vaismoradi et al., 2013). Quantitative content analysis was used to describe article characteristics using frequency counts and percentages. Content analysis is a qualitative and quantitative systematic approach to coding and categorizing text (Mayring, 2000; Vaismoradi et al., 2013).

4. RESULTS

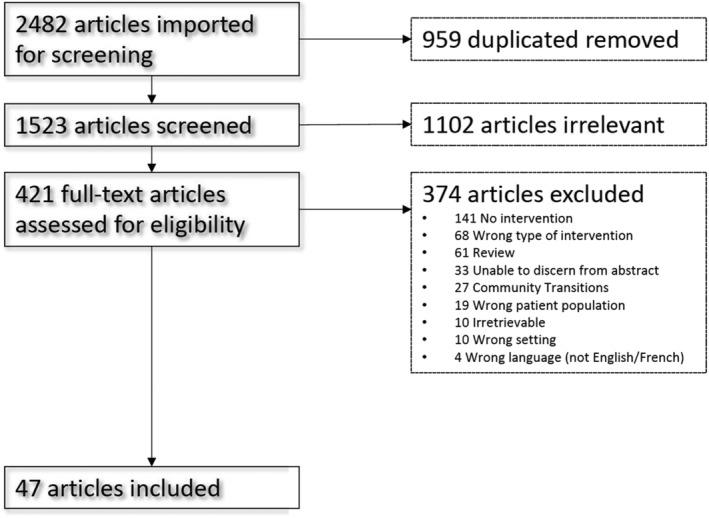

A total of 2482 citations were identified by our search strategy, with 1523 remaining after the removal of 959 duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, 421 citations progressed to full text review. A total of 47 articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review, of which 36 were empirical studies or protocols and 11 descriptive articles. The results of the search were reported in full following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews and presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2015; Tricco et al., 2018) (Figure 1). All included articles were in English, and reasons for exclusion at full text screening are presented in the diagram. The extracted data are summarized in Tables 2 and 3 and presented below, including article characteristics, programme characteristics and barriers and enablers related to implementation.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) diagram

TABLE 2.

Article characteristics

| Author/year | Country | Design | Article objectives | Outcomes | Outcome measures | Comparators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berens & Peacock (2015) | US | Retrospective analysis of health records |

Describe the development and implementation of the transition clinic. Describe how the clinic addresses the lack of suitable healthcare for young adults with significant chronic childhood conditions when ready to transition from paediatric to adult healthcare. |

No outcome specifically stated in methods but mentions description of programme with compilation of patient population demographics and the resources they require. | Retrospective tabulation of descriptive data: demographics, health conditions, resource use of patients who had attended a transition clinic. | NA |

| Betz and Redcay (2003) | US | Description of a transition programme | Describe the development and implementation of the Creating Healthy Futures clinic. | NA | NA | NA |

| Betz et al. (2003) | US | Retrospective review pilot study |

Describe self‐reported healthcare self‐care needs and level of healthcare self‐sufficiency of adolescents and young adults with special healthcare needs. Demonstrate relationships among self‐reported healthcare self‐care needs, level of healthcare self‐sufficiency, and selected demographics. Establish further validity of the California Healthy and Ready to Work Transition Health Care Assessment tool. Test this tool with a sample of adults and young adults with special healthcare needs |

NR | California Healthy and Ready to Work Transition Health Care Assessment tool. | NA |

| Betz et al. (2016) | US | Description of a transition programme | Describe the Movin' On Up Health Care Transition Model and lessons learned with plans for future evaluation. | NR | NR | NA |

| Betz et al. (2018) | US | Retrospective descriptive analysis |

Analyse healthcare transition services provided to adolescents and emerging young adults with spina bifida through the Movin' On Up transition programme. Investigate associations among selected variables and transition services provided. |

NR | 41‐item Spina Bifida Extraction Tool | NA |

| Breakey et al. (2014) | Canada | Pilot non‐blinded randomized controlled trial | Determine the feasibility of using a randomized control trial design on an online self‐management programme for patients with haemophilia. | Measure accrual and attrition; participant willingness to be randomized; compliance with the programme and completion of the outcome measures; and satisfaction. |

Primary outcome measure: Haemophilia Knowledge Questionnaire Secondary outcome measures: 1) Haemophilia Outcomes‐Kids’ Life Assessment Tool; 2) Generalized Self‐Efficacy‐Sherer Scale; 3) Self‐Management Skills Assessment Guide; and 4) programme satisfaction using an 11‐item questionnaire. |

Intervention group (Teens Taking Charge: Managing Hemophilia Online, a 8‐week programme with telephone coaching) vs. control (no access to the website, weekly telephone call as attention‐strategy) |

| Bundock et al. (2011) | UK | Comparison study (qualitative service evaluation) | Compare the healthcare experiences and preferences of young people with paediatric acquired HIV attending a new U.K. outpatient transition service called the 900 Clinic with young people attending a well‐established Australian transition service for young adults with diabetes. | NR | A semi‐structured questionnaire for use in both the United Kingdom and Australia, assessing the transition preferences and care satisfaction of young people attending the services. | U.K. transition service for young people with PaHIV (900 Clinic) vs. Australian transition service for young adults with diabetes |

| Cadogan et al. (2018) | US | Programme evaluation with a cross‐sectional descriptive design using a multiple methods approach | Evaluate compliance of and satisfaction with the Duke Complex Care Clinic with the seven core domains of the social‐ecological model of adolescent and young adult readiness for transition. | Measure quality of care and patient/family experience and satisfaction and perception of the clinic's compliance with the Social–ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness for Transition (SMART) model. | Patient and parent surveys were developed from a modified version of the Mind the Gap scale, with additional questions to measure patient and parent perceptions of clinic implementation of SMART and patient/parent satisfaction. | NA |

| Chouteau and Allen (2019) | US | Quality improvement |

Implement a process to increase the weekly completion of a portable medical summary (PMS) for use in transition to adult care in adolescents and young adults, who have Tier 2 and 3 medical complexities. Assess feasibility of the process by using balancing measures to evaluate whether other problems were created within the system with the initiation of the PMS. |

Improvement of the intervention delivery process. | Percent increase in weekly completion rates of portable medical summaries for AYA who met inclusion criteria. | Pre‐post |

| Ciccarelli et al. (2014) | US | Implementation science approach using prospectively collected data | Describe development of an ambulatory consultative transition support service using an implementation science approach. | NR | Intake survey of met and unmet needs. | NA |

| Ciccarelli et al. (2015) | US | Qualitative programme evaluation with a case study approach | Describe operations during Year 7 of implementation of a transition programme for children and youth with special healthcare needs. | NR | Annual programme satisfaction survey administered to primary care practices and families of children in the programme. | NA |

| Croteau et al. (2016) | US | Longitudinal design with pre‐post intervention comparison using a quality improvement model | Describe an approach to a transition process for patients with bleeding disorders using a quality improvement model. | Primary outcome measure: rate per clinic of completed patient competency assessment documentation and rate of completed patient skill development plan documentation. Secondary outcome measure: global‐ and age‐specific deficiency rates for each transition goal. | HEMO‐milestones Tool | Pre‐intervention group (patients seen during the 3 months immediately prior) vs. intervention group |

| de Hosson et al. (2021) | Belgium | Description of a transition programme | Describe the development, design, and content of a transition programme dedicated to adolescents with CHD (transition with a heart). | NA | NA | NA |

| Dogba et al. (2014) | Canada | Qualitative programme evaluation with a case study approach | Conduct a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats analysis of a programme for transitioning youth with osteogenesis imperfecta at a Shriners Hospital. | Achieve optimal levels of health, independence and self‐determination; live independently inclusively in their homes, schools and the community; and prepare for the future. | Face‐to‐face semi‐structured interviews with a sample of patients and parents of patients and with healthcare professionals and hospital managers. | NA |

| Doulton (2010) | US | Description of a transition programme |

Describe new transition process for adolescents and adults over 18 years of age with sickle cell disease. Present plans for a future transition programme. |

NA | NA | NA |

| Foster and Holmes (2007) | England | Description of a transition programme | Describe the transitional care arrangements established at Great Ormond Street Hospital to address the needs of children with severe epidermolysis bullosa as they from paediatric to adult care. | NA | NA | NA |

| Fremion et al. (2017) | US | Commentary on a chronic care model |

Highlight adolescent and young adults with spina bifida (AYASB) transition programme needs identified in the literature and within the local community. Analyse advantages and limitations of published AYASB transition care models. Demonstrate how the Texas Children's Hospital clinic used the Chronic Care Model to develop a comprehensive AYASB transition programme. Examine the potential feasibility in adapting this model to other spina bifida clinics. |

NA | NA | NA |

| Gaydos et al. (2020) | US | Retrospective case–control design | Determine the impact of an institutional CHD Transition Clinic intervention on patient follow‐up rates and transition readiness self‐assessments. | Primary outcome: participants ‘lost to follow‐up’ rate. Secondary outcome: Transition Clinic participant self‐questionnaire scores, self‐rated health‐related quality of life, trends in Transition Clinic patient transfer to adult CHD care. | 1) Chart review and defined as a persistent absence from cardiac care for at least 6 months beyond the recommended follow‐up time. 2) Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire and Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 3.0 Cardiac Module | Intervention group (transition programme) vs. control group (standard care) |

| Gravelle et al. (2015) | Canada | Quality improvement process description and evaluation | Describe the evolution of a transition clinic for patients with cystic fibrosis into a quality improvement transition initiative. | NR | 1) Evaluation of the workshop using a pilot questionnaire developed by the authors to address aspects of the transition process, 2) Cystic Fibrosis Readiness to Graduate Questionnaire also developed by the authors. | NA |

| Griffin et al. (2013) | US | Description of the developmental‐ecological framework and preliminary data (pre‐post assessment) |

Present early preliminary data from two programme components from the Sickle Cell Disease Age Based Curriculum (SCD‐ABC) Transition programme. Discuss challenges with implementation and offer suggestions for applicability of this framework to the challenge of SCD transition. |

Increased disease knowledge and self‐efficacy for adolescents and young adults. | 1) 10‐item SCD Knowledge Quiz at enrolment and after at least 1 clinic visit; 2) attendees and the Teen Scene Transition Day Event were asked to complete a satisfaction survey. | Pre‐post |

| Griffith et al. (2019) | US | Retrospective cohort design | Assess the impact of the comprehensive retention strategy programmes at two large urban ambulatory adult HIV programmes. | Successful retention at 1 year after transfer and successful transition. Viral load suppression (HIV RNA ≤ 400 copies/mL) after transfer was included as a secondary outcome. | Successful retention was defined as ≥2 provider visits in the adult clinic ≥90 days apart within 1 year of transfer. Successful transition, a composite outcome, was defined as successful retention, plus a stable HIV viral load (VL). | NA |

| Hergenroeder et al. (2016) | US | Description of lessons learned from a transition programme | Describe nine lessons learned in developing and implementing a healthcare transition planning programme that serves patients regardless of disease or disability within a large paediatric teaching hospital. | NA | NA | NA |

| Jurasek et al. (2010) | Canada | Process evaluation with patient and caregiver questionnaires | Describe the collaborative development of a nurse‐led transition clinic within the Comprehensive Epilepsy Programme at the Stollery Children's Hospital and at the University of Alberta Hospital. | NR | 1) Self‐assessment intake questionnaire that assesses adolescents' level of independence; 2) programme evaluation survey at the time of first transition clinic visit and 3 months after first adult neurologist clinic visit. | NA |

| Ladouceur et al. (2017) | France | Descriptive cross‐sectional design | Determine educational needs and impact of a structured education programme on knowledge and self‐management in a population of youth with congenital heart disease (CHD). | Primary outcomes: impact of a structured education programme at transition on improving health knowledge (CHD and general lifestyle and medical care knowledge) as well as self‐management skills in this population. Secondary outcome: identify patient‐specific factors associated with general health knowledge in adolescents and young adults with CHD. | Specific knowledge questionnaire developed by the investigators. | Education group (previous educational programme + standard care) vs. comparison group (standard care) |

| Lemke et al. (2018) | US | Randomized control trial | Evaluation of a healthcare transitions care coordination programme. | Perceptions of chronic illness care quality and care coordination in control and intervention patients. | 1) Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care questionnaire; and 2) Client Perceptions of Coordination Questionnaire, measured at baseline and 6 and 12 months after enrolment. | Intervention group (intervention + enhanced usual care) vs. control group (enhanced usual care) |

| Lindsay and Hoffman (2015) | Canada | Qualitative descriptive design | Describe the experiences, barriers, and enablers of three young adults with complex care needs transitioning from an institutional paediatric hospital setting to an adult community residence. | NR | 1) Semi‐structured interviews with clinicians, community partners and young adults with complex care needs; and 2) review of minutes from ‘Think Tank’ meetings. | NA |

| Mackie et al. (2014) | Canada | Clinical trial | Determine impact of a transition intervention for youth with CHD. | Primary outcome: change in transition self‐management score. Secondary outcome: change in knowledge of the heart condition. | 1) Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) at enrolment and 6 months and 2) MyHeart scale at enrolment, 1 and 6 months. | Intervention + usual care vs. usual care alone |

| Mackie et al. (2018) | Canada | Cluster randomized clinical trial |

Evaluate the impact of a nurse‐led transition intervention for children with CHD on lapses between paediatric and adult care. Describe the change in participants' knowledge, self‐management, and self‐advocacy skills and incidence of cardiac procedures post‐enrolment. |

Primary outcome: excess time between paediatric and adult CHD care. Secondary outcome: change in the CHD knowledge; transition readiness; and incidence of cardiac re‐intervention (surgery or interventional catheterization) post enrolment. | 1) Time interval between the final paediatric visit and the first adult visit, minus the recommended time interval between these visits; 2) Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire at 1, 6, 12 and 18 months; 3) Williams' self‐management scale at 1, 6, 12 and 18 months; 4) MyHeart CHD knowledge survey at baseline, 1, 6, 12 and 18 months; 5) cardiologist perception of patient readiness for transition measured at transition; and 6) incidence of cardiac surgery or catheterization measured at 12 and 24 months post enrolment. | Intervention + usual care vs. usual care alone |

| McManus et al. (2015) | US | Prospective pilot study | Describe the process and results of incorporating six core elements of Health Care Transition (2.0) into a Medicaid managed care plan. | The primary question that this project was designed to address was can the Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition be incorporated into a Medicaid managed care plan. | 1) Current Assessment of Health Care Transition Activities tool, used to assess transition implementation, at the start and after 6 months in the pilot project participants; 2) transition readiness/self‐care knowledge and skills were also measured among the pilot group; and 3) Transition Feedback Survey, used to elicit consumer feedback at the end of the transition to adult care. | NA |

| Mitchell (2012) | Scotland | Participatory stakeholder approach utilizing realistic evaluation (a framework for programme evaluation) | Describe the early implementation stage of a pilot project in a Scottish local authority introducing self‐directed support (SDS) in transitions for disabled children and young people moving from children to adult services. | NR | Focus groups and semi‐structured interviews. | NA |

| Moosa and Sandhu (2015) | UK | Descriptive analysis of a quality improvement project (pre‐post outcome comparison) | Design, implement, and evaluate an ADHD transition pathway from adolescence to adulthood from Children's Mental Health Services to Adult Mental Health Services. | Reduce the number of steps in the transition process; reduce waiting times; increase the rate of successful handover; and to reduce the rate of disengagement and those lost to follow‐up. | 1) Pre‐post descriptive statistics at the beginning and 1 year into the project and 2) outcomes (% who transitioned to adult care, referral rate, discharge from paediatric care, non‐attendance rate, discontinuation/disengagement rate). | Pre‐post |

| Razon et al. (2019) | US | Description of a transition programme |

Describe the Adult Consult Team at a children's hospital to coordinate transition planning and transfer to adult‐oriented care. Review patient healthcare utilization. Estimate expected healthcare utilization for following year. |

Measure inpatient admission days and outpatient clinic visits. Predict healthcare utilization. |

Reports of healthcare utilization. | NA |

| Saarijärvi et al. (2019) | Sweden | Protocol for a randomized control trial longitudinal study | Protocol aims to describe the process evaluation of the STEPSTONES transition programme. | Measure patient empowerment; transition readiness; disease‐related knowledge; health behaviours, patient‐reported health; quality of life; healthcare usage; and parental uncertainty towards transfer to adult care. | Gothenburg Young Persons Empowerment Scale. | Intervention group (transition programme) vs. control group (standard care) |

| Samuel et al. (2019) | Canada | Protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial parallel group study |

Evaluate the impact of a personalized transition to adult care intervention (access to a patient navigator) compared with usual care for individuals aged 16–21 years living with chronic health conditions who are transferring to adult care. Determine the net healthcare cost impact attributable to the patient navigator intervention. Obtain perceptions of stakeholders regarding the role of patient navigators in reducing barriers to adult‐oriented ambulatory care. |

Primary outcome is to measure emergency room (ER)/urgent care visits. Secondary outcomes is to measure inpatient and ambulatory care utilization; transition readiness scores; and patient‐reported health status. |

1) Use of PHN to link with health service utilization data; 2) evaluate ambulatory and inpatient care utilization measures as rate of events; 3) Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ); and 4) patient reported health status as measured by the 12‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐12). | Intervention group (transition programme) vs. control group (standard care) |

| Seeley and Lindeke (2017) | US | Quality improvement pilot study (pre‐post questionnaire comparison) | Develop readiness for transition to adulthood in youth with spina bifida and their parents through a quality improvement pilot study. | Readiness for transition. | Transition readiness assessment questionnaire at baseline and 4–6 months after starting the transition care coordination programme. | Pre‐post |

| Spaic et al. (2013) | Canada | Multicentre randomized parallel‐group controlled trial | Determine if a structured transition programme for young adults with type 1 diabetes improves health outcomes. |

Primary outcome to measure compare the proportion of young adult type 1 diabetes patients who fail to attend regular diabetes care with those receiving standard care. Secondary outcomes to compare the frequency of routine diabetes testing as well as rates of hospitalizations for diabetes related problems; and patient satisfaction with the transition process between the groups. |

1) The proportion of subjects who fail to attend at least one outpatient adult diabetes specialist visit during the second year after transition; 2) frequency of A1C testing; 3) mean A1C levels; 4) frequency of testing for microalbuminuria, lipid profile, foot and retinal examinations; 5) rates of diabetes related emergency room visits and hospitalizations for DKA and hypoglycemia; and 6) patient satisfaction and perception of the care during the transition period using self‐administered questionnaires. | Intervention group (transition programme) vs. control group (standard care) |

| Spaic et al. (2019) | Canada | Multicenter, randomized, parallel‐group, controlled trial | Determine if a structured transition programme for young adults with type 1 diabetes improves health outcomes. |

Primary outcome to measure the proportion of participants who failed to attend at least one adult diabetes clinic visit during the 12‐month follow‐up period. Secondary outcomes to measure the frequency of HbA1c testing; mean HbA1c level; frequency of complication screening; diabetes‐related emergency room visits and hospitalizations for diabetic ketoacidosis and hypoglycemia; patient satisfaction with the transition process; and diabetes distress; and impact of diabetes on quality of life. |

1) Mean HbA1c calculated separately for the central and local measurements collected during the designated periods; 2) Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ), 3) Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS); 3) Diabetes Quality of Life (DQL); and 4) a transition intervention evaluation questionnaire at completion of follow‐up. | Intervention group (additional support by the TC) vs. control group (diabetes care as per Diabetes Canada clinical practice guidelines) |

| Steinbeck et al. (2012) | Australia | Pilot randomized controlled trial | Determine if transition in type 1 diabetes is more effective with a comprehensive transition programme compared with standard clinical practice. | Primary outcome to measure engagement and retention in the adult service. Secondary outcomes to measure haemoglobin A1c; diabetes related hospitalizations; microvascular complication appearance; and global self‐worth. | 1) Measure of engagement by looking at (a) successful transfer involving at least one visit to an adult diabetes service post‐discharge from paediatric care, (b) frequency of visits to the adult service and (c) time interval between the last paediatric diabetes service visit and first adult diabetes service visit; 2) HbA1c, diabetes‐related hospitalizations, microvascular complication; and 3) global self‐worth measured by Harter self‐perception profile. | Intervention group (comprehensive transition programme) vs. control group (standard clinical practice) |

| Szalda et al. (2019) | US | Description of a transition programme and quantitative survey. | Assess the feasibility and acceptability of a multidisciplinary team using a population health‐based framework for comprehensive paediatric to adult healthcare transfers at a large free‐standing academic children's hospital. | Reported measures include comfort with discussing transition, time spent with care coordination, satisfaction with programme, and time from referral to adult care. | Healthcare provider survey | NA |

| Tan and Klimach (2004) | UK | Prospective semi‐quantitative design | Obtain feedback from parents and young people regarding the value and usefulness of a transition portfolio and evaluate satisfaction with the process and the final portfolio. | Evaluation of parent and patient's degree of satisfaction with the transition portfolio. | Questionnaire developed by investigators. | NA |

| Tsybina et al. (2012) | Canada | Protocol for a prospective, longitudinal, mixed‐method process and outcome evaluation | Describe the study design, choice of outcome measures and methodological challenges for the Longitudinal Evaluation of Transition Services study. | Primary outcome to measure post transition continuity of care. Secondary outcomes to measure health and well‐being; activities and social participation; transition readiness; and healthcare utilization. | 1) Health Care utilization data, chart audit, and self‐reports; 2) Allied Care Form (study specific questionnaire); 3) self‐ Arc's self‐determination scale; 4) community involvement form (study specific questionnaire; 5) self‐rated health scale from the National Health Interview Survey; 6) assessment of health related quality of life (the Health Utilities Index); 7) demographic information form; 8) youth and parent interviews. | NA |

| Werner et al. (2019) | France | Prospective observational, cross‐sectional, multicentre |

Describe the structure of the regional transition education programme. Describe the factors which influence the participation of adolescents and young adults with CHD in this programme. |

Measure level of knowledge; level of physical activity; health related QoL; and severity of CHD. | 1) Level of knowledge assessed by transition readiness assessment; 2) level of physical activity by Ricci and Gagnon score; 3) health related quality of life assessed by PedsQL questionnaire; 4) CHD severity by cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET); and 5) exposure to comorbidity risk factors | Intervention group (transition programme) vs. control group (standard care) |

| Wiener et al. (2007) | US | Prospective cohort design | Examine the association between transition readiness, specific barriers to transition and level of state anxiety in a population of youth with HIV whose clinic was closing. | Poor transition readiness scores and state anxiety levels. | Measured at enrolment and after at least another clinic visit: 1) A Transition Readiness Scale developed by investigators, and 2) State/Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults. | Pre‐post |

| Wills et al. (2010) | US | Description of a transition programme | Describe the experience of families with the Sickle Cell Disease Program for Learning and Neuropsychological Evaluation (SCD‐PLANE) at the Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota. | NA | NA | NA |

| Woodward et al. (2012) | US | Self‐administered survey design with results compared with a national survey | Describe development, implementation and initial results of an assessment of the health status and service needs of youth with special healthcare needs attending a non‐categorical transition support programme. | Measure patient‐ and parent‐reported needs of youth attending a non‐categorical transition support programme. | Single response from parents of youth with special healthcare needs to a self‐administered questionnaire. | Compared against the 2005–2006 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs |

| Wu et al. (2018) | US | Qualitative case report on patient and provider experiences | Describe how a Children's Hospital of Philadelphia clinic embedded a patient perspective into a multidisciplinary team tasked with addressing transition to adulthood. | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

TABLE 3.

Programme enablers and barriers to transition

| Author/year | Enablers | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Berens and Peacock (2015) | Full‐time social worker on staff; large amount of care coordination; extended office visits | Lack of sustainable programme funding; low availability of community physicians to co‐manage care; inadequate training with community physicians due to lack of familiarity in managing complex disease; lack of curriculum during training around transition healthcare |

| Betz and Redcay (2003) | Leveraging community resources to avoid service duplication and costs; use of paediatric nurses/nurse practitioners; assess and identify healthcare needs that affect achievement of goals; youth‐centered and asset‐oriented | NR |

| Betz et al. (2016) | Nurse‐led programme; integrated with other services; interdisciplinary approach; comprehensively addresses health needs around health, education, employment, social relationships and community living; life‐span approach to initiate long‐term planning of transfer; increased understanding of transition readiness among care providers; knowledge of community‐based resources available | Service model adjustments to accommodate practice realities around implementation of the programme; fiscal challenges to ensure clinic sustainability; scheduling changes to accommodate youth and families to minimize number of visits; team availability for meetings; changes in staff assignments/staff turnover; burden of assessing transition readiness; difficulty in measuring success of programme |

| Betz et al. (2018) | NR | Difficulty accessing care and community resources; difficulty accessing resources in native language; difficulty scheduling weekly interdisciplinary team meetings; difficulty scheduling transition at upcoming appointments |

| Breakey et al. (2014) | Use of a telephone‐coach increased compliance | Sustainability around use of a coach in the future; programme attrition |

| Cadogan et al. (2018) | NR | Difficult to ensure consistent use and understanding of the transition tracking tool by all providers over time; difficulties implementing practice change when environment unstable (clinic moved during study); not enough patient and parent transition education; workflow challenges that enable incorporation of transition tool into practice |

| Chouteau and Allen (2019) | Using plan‐do‐study act cycles; the use of a portable medical summary | NR |

| Ciccarelli et al. (2014) | NR | Cost of intervention; primary care providers not yet having high familiarity with transition knowledge and recommendations to provide this service to patients without other education or support |

| Ciccarelli et al. (2015) | Cross‐communication between primary care and specialty doctors; time spent in arranging complex services; period of acute post‐visit care coordination to last approximately 90 days to decrease initial barriers; open‐access to call in questions around new issues or concerns; call to families at one‐year anniversary to offer annual return visit; self‐management education and activities through additional workshops; consultative transition support programme to help medical homes | Regional access problems for mental health and behavioural resources that have an impact on the frequency of services in the transition programme; cost of sustaining the programme; lack of appropriate billing codes for longer physician appointment times and non‐face‐to‐face activities; lack of familiarity with transition knowledge and recommendations for primary care providers who have less education and support on the topic |

| Croteau et al. (2016) | Diligence around discussing transition issues; identification of knowledge gaps during clinic visits; providing targeted education and anticipatory guidance; collaboration among multidisciplinary team to inform patient support and planning; using developed tool during routine clinic visits | Continual modification of the HEMO‐milestones tool to enable real‐time implementation without redundancy of provider effort or lengthening of patient encounters |

| Dogba et al. (2014) | Closely linked to care coordination; led by an interprofessional team; based on comprehensive definition of transition; allowed time to assess for transition readiness; programme monitored and evaluated; support from a range of stakeholders | New team members with lack of programme motivation; potential conflict between the transition programme and research participation; gaps in implementation (insufficient tools for patient information, education and preparation for the transition, with the main source of information being a single pamphlet) |

| Doulton (2010) | NR | Patients who do not attend their first adult provider appointment; lack of enthusiasm from paediatric providers on transferring patients; lack of miscommunication between adult and paediatric providers; lack of motivation from patients to self‐manage their care |

| Foster and Holmes (2007) | Paediatric and adult providers working together to ensure a smooth transition; flexibility in nursing roles to enable them to transfer care | Difficulty coordinating transfer of patient medical history to adult team |

| Fremion et al. (2017) | Visits every 3 months during the adolescent years facilitate transition care planning; care coordination; regular chronic condition status/self‐management assessment and intervention; rapport between patients and providers; opportunity for patients to practice their care navigation skills; having an adult provider embedded in paediatric clinic allowing for acclimation to adult provider in familiar care setting; having nursing staff for care coordination and self‐management coaching; social workers to facilitate case management at each clinic visit | Lack of adult providers with disease‐specific expertise who can see patients in paediatric setting; lack of staff resources (i.e. nursing staff) to facilitate transition care and planning; travel‐distance that inhibits attending appointments every 3 months |

| Gaydos et al. (2020) | The premise that the clinic's focused education on CHD implications and health‐management skills translates into better continuity of cardiac care; CHD Transition Clinic electronic registry database; face‐to‐face introduction of a member of the Adult CHD care team | Strong patient or family desire to remain with their paediatric cardiologist |

| Gravelle et al. (2015) | Use of paediatric nurses to develop, implement and evaluate transition service models and to assume greater leadership in adolescent transition; orientation to underlying transition framework; professional expertise to assist youth in meeting various indicators; integrate transition teaching in care; transition tool was quick and easy to complete and was a good indicator of readiness to move onto adult clinic | Slow progress in immerse use of a transition tool as a routine standard of care; difficult filling prescriptions; medical insurance considerations; lack of in‐depth medication knowledge; difficulty soliciting feedback on transition from healthcare team members; difficulty getting inclusive multidisciplinary team to chart on the transition readiness; difficulty completing all indicators of transition readiness |

| Griffin et al. (2013) | The ability to actively engage additional stakeholders in the pre‐planning phase | Limited number of adult providers with appropriate training to provide care for young adults with this condition; lack of collaboration between paediatric and adult providers; financial and resource barriers; limited disease‐specific and gender‐specific knowledge among adolescents; fear of the unknown about adult life |

| Griffith et al. (2019) | NR | Persistent significant racial disparities in HIV care and the importance of addressing racial disparities, alongside socioeconomic disparities, as part of the transfer process |

| Hergenroeder et al. (2016) | Having a medical summary at first adult visit; identification of staff whose job is transition planning; greater awareness around the importance of the transition process | Reluctance to refer to adult provider without knowing specific adult providers to whom they could transfer patients; lack of time to adopt programme |

| Jurasek et al. (2010) | Optimizing timing of clinic when adolescents are not preoccupied with school; having paediatric and adult programmes situated on the same site, collaboration (enabled by co‐location) | NR |

| Ladouceur et al. (2017) | Use of nurse coordinators to enable transfer and follow‐up; improved disease knowledge | Low educational attainment (academic and/or cognitive difficulties); emotional attachment of parents and patients to paediatric care providers; reluctance to transition; clinician attachment to parent/family; lack of medical knowledge around life‐long care and health maintenance |

| Lindsay and Hoffman (2015) | Inter‐agency partnerships; addressing client concerns via a family information night; paediatric hospital training to community‐based personal support workers providing adult care; interprofessional teamwork; commitments made by senior leaders in Think Tank meetings; overlap between paediatric and adult care providers; family support; meeting a mentor with similar medical complexity living independently in the community; visiting their new residence prior to the move; feeling a new sense of independence | Duration of transition period (8 months); the use of different funding models across paediatric and adult medical systems; different models of care in paediatric and adult system; concerns around safety and quality of care in adult system provided by personal support workers; clinician concerns around clients' ability to direct their own care in the community; lack of role clarity; balancing clients' wants and needs with family concerns about their care; sense of loss felt by front‐line staff and clients; feeling rushed and overwhelmed around transition; concerns around perception that clients would have difficulty directing personal support workers in their care |

| Mackie et al. (2014) | NR | Asymptomatic patients who are less concerned with transition process |

| Mackie et al. (2018) | Nursing time to deliver 1‐on‐1 meetings with participants; low cost | Time‐intensive nature of intervention |

| McManus et al. (2015) | Having nurse care manager and paediatric and adult focused clinicians involved in care; texting; engaged adult providers; clear delineation of roles among providers; leadership from the organization; electronic information management; offer health education and self‐care skill development in a more intensive and continuous manner; systematically identify and communicate with transitioning youth and young adults; help with vocations and education not just healthcare; begin transition earlier (12–14 years) | Health not the priority for young adults; highly transient population; telephone numbers change often; dependent on parents as caregivers; not enough time to do all the steps and provide the needed care |

| Moosa and Sandhu (2015) | Collaborative effort between paediatric and adult service providers; accurate data and information sharing; standardized and streamlined transition process; reducing wait time; improving continuity of care; better engagement of youth. | Coordination of joint ADHD clinics coordinated by paediatric and adult teams |

| Razon et al. (2019) | Multidisciplinary team with knowledge of young adult health issues; medical and community resources | Identification of and access to appropriate adult providers; insurance |

| Seeley and Lindeke (2017) | Expanding outpatient resource nurses' to include transition care to reduce financial constraints; monthly nurse‐initiated contact with youth and their families; scheduling transition meetings in coordination with other appointments; increasing use of videoconferencing on handheld devices; arranging contacts and sending resources via email, encouraging youth to have their own email address so that both parent and youth receive the same information; start transition preparation at 12 years or sooner; completing a transition readiness assessment questionnaire; encouraging youth to assume responsibility for their own needs; well‐developed programme that used existing resources; front‐end support from influential nurse leaders and administrators; face to face contact with nurses; self‐management activities; support to attain goals | NR |

| Spaic et al. (2013) | Age‐appropriate means of communication (i.e. text‐messaging versus phone/email; long‐term follow up period to better measure outcomes; focus on addressing emotional burden of illness and reducing barriers to access care | NR |

| Spaic et al. (2019) | Length of programme (18‐month structured transition programme) | NR |

| Steinbeck et al. (2012) | Provider making the first appointment with the adult provider; structured transition; transition support; familiarity of environment | Disinterest in transition process/support; parental encouragement as a deterrent to participate; not enough incentive; youth/families too busy |

| Szalda et al. (2019) | Partnership with hospital leadership and multiple divisions, along with empowering divisional champions; identify current processes and subsequently disseminate best practices; encouraging the adaptation of national resources. | Time intensity of implementing hospital operations‐level change and offering direct patient consults; work needs to be supported on an institutional level |

| Tan and Klimach (2019) | Health portfolio package that provides parents and young adults with health advice | Lack of consultation around development of the contents for the health portfolio; lack of integration of educational and social service perspectives |

| Werner et al. (2019) | NR | Time requirement to run the education programme |

| Wiener et al. (2007) | NR | Poor readiness; having to pay for medications out‐of‐pocket; lack of insurance coverage; paucity of/lack of paediatric community‐based providers; lacks confidence in home physician; the need to transition out of paediatric care; lack of a social worker to provide advocacy and support in the community; lack of pharmacy in home community |

| Wills et al. (2010) | NR | Insurance denials, scheduling issues, and missed clinic appointments |

| Woodward et al. (2012) | More intensive care coordination (increased time per patient, coordination between multiple providers, etc.); standardized approach to addressing multiple complex needs identified; identify opportunities for skill development in mental healthcare; appropriate counselling on health‐risk behaviour, routine preventative care | NR |

| Wu et al. (2018) | Building rapport and trust based on shared experiences; building specific skills to practice (i.e. making phone calls to make appointments); modeling effective problem‐solving strategies; communicating with providers | NR |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CHD, congenital heart disease; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

4.1. Article characteristics

The characteristics of the included articles are summarized in Table 2. Article characteristics included article objectives, design, comparators, outcomes, and outcome measures.

4.1.1. Article objectives

The majority of article objectives, as described by their authors, primarily focused on describing a transition programme (n = 42). A secondary objective of many articles was an evaluation of a described programme, intervention, or innovation (n = 17). Additional article objectives centred around transition readiness (n = 15), satisfaction (n = 12), disease knowledge (n = 11), patient and family needs (n = 6), lessons learned during the development of a programme (n = 5), personnel compliance with performing or documenting the intervention (n = 2), paediatric‐adult system collaboration (n = 2), and future plans to assess intervention impact (n = 2).

4.1.2. Article designs

There were a mix of research studies (n = 33 studies, n = 3 study protocols) and descriptive articles (n = 11) included in the review. Of the included articles that conducted an evaluation, the majority were mixed‐methods studies. Studies also used retrospective analyses (n = 6), prospective cohort designs (n = 6), and pre‐post study (n = 6) designs. Some studies employed randomized controlled trial (RCT; n = 9) or longitudinal (n = 3) designs. Where RCT designs were employed, the studies included a combination of cluster, parallel‐group, and non‐blinded types of randomization.

4.1.3. Article comparators, outcomes, and outcome measures

Comparators were included in studies that comprised pre‐post intervention designs (n = 4) or when a pre‐intervention group was compared with an intervention group (n = 2). The majority of the control groups were described as ‘standard care’ (n = 6), ‘usual care’ (n = 2), or ‘standard clinical practice’ (n = 1). Other comparators included results from a national survey (n = 1) and a transition service from a different country (n = 1). Several studies did not have comparators due to the nature of the study focus.

Although more than half of the articles explored programme‐ or patient‐level outcomes as evidenced by their study design or results (n = 30), only 16 studies explicitly identified study outcomes. Programme‐level outcomes included personnel compliance with intervention delivery (n = 8); programme strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (n = 4); and transition successes in terms of patient health and continuity of care (n = 4). Various papers described transition programmes or interventions without measuring specific outcomes (n = 9). Two articles, one of which was a protocol, described outcomes and outcome measures that could be used to evaluate programmes, but no results were presented. Few articles described patient‐level outcomes in their methods, with many presenting only descriptive patient demographics (n = 16). Of those that reported patient‐level outcomes, the most common were patient, family, or provider satisfaction (n = 8); transition readiness (n = 6); patient knowledge (n = 5); perception of illness, care and care coordination (n = 5); self‐management or efficacy (n = 5); quality of life (n = 4); health service utilization (n = 3); and patient needs (n = 2). Of note, 12 of the reviewed articles described the use of validated survey tools for data collection, such as the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ), the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC).

4.2. Programme characteristics

Several programme characteristics for transition services were described. These included programme services, clients, setting, team composition, and guiding frameworks. A supplemental table (Data S1) is also available upon request that outlines the programme characteristics at the patient, provider, and system/organization level following the Children's Healthcare Canada (CHC) transition guidelines.

4.2.1. Services

Programme services ranged from a specific tool or resource to comprehensive multi/interdisciplinary clinics with a transition framework. A limited number of programmes included full paediatric to adult healthcare provider integration (n = 6), and two articles included ‘stand‐alone’ adolescent medical clinics that bridged the gap between paediatric and adult healthcare. A few articles described quality improvement processes (n = 5), where one paper outlined a multi‐year approach to improving transitions across a health centre. In some articles (n = 10), person‐centred care was a principle in the delivery of transition programmes for youth transitioning from paediatric to adult healthcare.

Very few articles referred specifically to policies that support cross‐sector collaboration or collaboration between health centres or the broader healthcare system. Transition‐focused clinics allowed greater capacity to deliver a multi/interdisciplinary approach and often more comprehensive care (n = 11). Collaboration between clinicians and patients/families was a key element of comprehensive care (n = 6).

Some of the included programmes offered online resources and services (n = 4), such as access to electronic health records and video appointments to ease travel burden. Two articles outlined a novel electronic approach to engagement that included video games aimed at building condition‐specific health knowledge.

The age at which transition planning services began varied greatly. Some described initiating transition care in the early teenage years (n = 9); however, a few programmes took a more long‐term approach with transition planning beginning at birth and/or diagnosis to prepare patients and families for self‐management and transfer of care (n = 3). Some programmes targeted transition preparation later when youth were in their late teens or early 20s (n = 9). Two programmes provided care for patients into and beyond their early 30s.

4.2.2. Clients

Several articles did not report a complete profile of the characteristics of their programme clients. Of the articles that reported on the number of programme clients, these ranged from 10 to 332 clients. The mean ages ranged from a low of 10.2 years to a high of 22.6 years. The reported age ranges were from 1 to 54 years.

Reviewed articles reported programme clients as having a variety of conditions, including physical conditions (n = 19), mental health conditions (n = 7), and intellectual disabilities (n = 4). Some clients had more than one condition and were thus included in more than one category, for example physical and intellectual (n = 5; e.g. Down syndrome and cerebral palsy). Other reported conditions were referred to in more general terms (n = 8; e.g. CCN, developmental delays).

4.2.3. Setting

Included articles reported a variety of different programme settings. Hospitals (n = 14) and medical institutions with an academic focus (n = 7) were the most common programme settings. Articles also reported various types of medical clinics and centres. A few articles simply listed the programme focus as a specific community or service (n = 4).

4.2.4. Team composition

Articles consistently mentioned transition work as being interdisciplinary and often having a multi‐year approach to care. Typically, articles described team composition as including physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers and occupational, physical and speech therapists. A few articles included a broader range of team members (e.g. housing, social services and educational specialists), typically noting the importance of collaboration with other community services (n = 6). Seldom were youth and family supports discussed (n = 4), with only one article listing the patient and parent/guardian as members of the interdisciplinary team. Team composition varied depending on the specific health conditions. Healthcare systems also influenced differences in transition processes and team compositions due to health funding and insurance needs for patients. In some instances, the transition team provided direct referral to a specific specialist (n = 10), whereas others allowed the youth and family to choose their specialist (n = 3). Differences in health systems also posed specific issues when transition involved providers and teams in other provinces or states (n = 3).

The included articles generally did not describe transition related skill sets for providers. In some cases, one member of the team was designated as the transition coordinator (n = 13), but there was little mention of the skills required to ensure the professional in this role had specific transition training.

4.2.5. Guiding frameworks

Some articles reported explicit use of a validated theoretical framework to guide programme development (n = 10). One such theoretical framework was the Socio‐ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness for Transition (SMART). Two articles used implementation science methods to guide the approach to programme development and implementation but did not discuss specific frameworks. Additionally, six studies reported the use of established approaches to the development of transition programmes, such as the Got Transition's 6 core elements of healthcare transition (White et al., 2020) and the Lean approach (Lord et al., 2014).

4.3. Programme barriers and enablers

Barriers and enablers to programme implementation were reported in many articles. Commonly reported barriers and enablers included financial support, training of care providers, transition coordinators, collaborative care, transition tools, and interpersonal support. The following section provides an overview of these barriers and enablers. Please see Table 3 for a comprehensive summary.

4.3.1. Financial support

One barrier to implementing transition programming was related to having different funding models in paediatric and adult care. Some of the reviewed articles reported a lack of sustainable programme funding to cover staff time and associated resources to operate transition programmes (n = 4). Alongside this, articles identified having financial investment in transition care from the institution as being key to the success of transition programmes (n = 2). In addition, there were reports of a lack of healthcare coverage to participate in transition programmes or treatment in adult care (e.g. lack of insurance and having to pay for prescriptions out of pocket). These financial barriers are context and country specific and were not emphasized in most studies.

4.3.2. Training of care providers

A number of articles reported that a lack of knowledge and education around managing complex conditions, as well as a lack of curriculum training around transition care, were barriers to providing appropriate care (n = 6). Care providers themselves were also reported as a barrier to transition if they lacked knowledge of the adult system. This lack of training and/or knowledge was shown to lead to a reluctance of paediatric providers to transition patients, which was often coupled with a lack of care coordination and/or miscommunication with adult providers (Hergenroeder et al., 2016; Ladouceur et al., 2017; Lord et al., 2014).

4.3.3. Transition coordinators

Having access to a transition focused position involved in the care team appeared to be key to having well‐developed, structured, and organized programmes (n = 11). This position was typically filled by a nurse (n = 14) who acted as a transition coordinator allowing for more time to be spent with the patient and family and facilitating a better transition. The absence of a dedicated position to support the transition process was found to be a barrier because clinicians did not have enough time to provide the necessary support. This issue was highlighted when physicians led transition preparation and were unable to balance the many duties required to support a smooth transition to adult care (Hergenroeder et al., 2016).

4.3.4. Collaborative care

A few articles identified interdisciplinary teams as enablers given their ability to address diverse health needs as well as social needs (n = 6). Having a team of care providers with knowledge of a broad range of services reduced duplication, which, in turn, was more cost effective for both the client and the programme (Betz & Redcay, 2003). Improved coordination of appointments, including the arrangement of the first appointment with the new adult care provider, was reported to improve transitions (Steinbeck et al., 2012). Having an adult provider embedded in a paediatric clinic or on the same site allowed patients to acclimatize to their new provider and facilitated collaboration between paediatric and adult care systems (Fremion et al., 2017). Finally, studies identified having strong and supportive administrative leadership as part of the broader team as an important enabler (n = 3).

4.3.5. Transition tools

The development or use of pre‐existing transition tools and technology (e.g. websites and apps) provided support for health education, resource referrals, and virtual care coordination (n = 8). Some programmes also developed a variety of transition materials, for example a medical summary developed with an adult provider's input to facilitate transfer to adult care. Flexible use of communication tools, particularly text message, teleconference, telephone, and email, was also an enabler to improve the transition process. Some transition tools or materials were, however, noted to be barriers due to the time required to develop or adapt the tool or because uptake among providers was slow. Insufficient tools and a lack of physical resources were also reported as barriers to a smooth transition process. Some authors noted that social determinants of health could affect parental access to tools and necessary supports for youth, resulting in a lack of transition readiness.

4.3.6. Interpersonal support

Several enablers were identified around interpersonal support (n = 7). It was reported that peer support—whether promoted through more formalized transition support groups or informally, such as in the waiting room—was very beneficial to youth. A strong relationship with paediatric care providers was identified as an important enabler to a smooth transition, and it was recommended that the transition process includes discussions with youth early on. Access to a primary care provider was reported as essential to support attachment in adult services, where the primary care provider would become the coordinator or ‘quarterback’ for many patients and families after establishment in adult care (Ciccarelli et al., 2015; Schraeder et al., 2020). In terms of barriers, issues arose when youth became too comfortable in the paediatric system and were resistant to the necessary shift to adult care (Hergenroeder et al., 2016). This could occur when youth become too dependent on their parents and/or lack motivation to manage their health.

5. DISCUSSION

This scoping review examined the range and characteristics of programmes in the literature that support youth with CCN and their families as they transition from paediatric to adult healthcare. This review also identified reported barriers and facilitators to the implementation of these initiatives, as well as common outcome/evaluation measures. The findings from this review can help to inform practice, policy, and research directions to improve the transition between paediatric and adult health services for youth with CCN and their families. Whereas the large number of articles (n = 47) included in this review is indicative of the shared concern for the topic of paediatric to adult healthcare transition, our work nonetheless highlights a concerning paucity of information, which must be taken into consideration when informing policy, practice, and further research. Although there are several reviews that have examined the area of transition, generalizable findings have previously been difficult to extract, as the focus was narrowed to specific populations; the interventions and outcome measures were heterogeneous; or the descriptions of context limited. This review has begun to fill this knowledge gap.

In the discussion below, we first examine the strengths of the programmes reviewed and then identify areas for improvement. We discuss these in relation to recommendations by the CHC transition guidelines. While our review has an international focus, we have used this Canadian framework for discussion purposes given its focus on supportive transitions from paediatric to adult healthcare. However, this framework can be applied in other contexts. We conclude our discussion with several policy and guideline recommendations to improve the transition from paediatric to adult healthcare, which draw on our findings about the various programme strengths and areas for improvement reported below.

5.1. Programme strengths

Several strengths were identified in the transition programmes reviewed. Strengths included a commitment to assessing readiness with the use of readiness questionnaires and/or assessment conversations with clinical and transition support personnel. The focus on readiness also included building self‐management skills in youth, which may incorporate general health management and advocacy skills, as well as condition‐specific skills (e.g. insulin management). Self‐efficacy has been found elsewhere to be a feature of transitional healthcare that is associated with better outcomes for young people with long‐term conditions during their transition from child to adult healthcare (Colver et al., 2018). Additionally, there was an emphasis on the importance of developing a plan for the transition to adult healthcare that involved both the youth and their family.

Interdisciplinarity among the transition care team, with emphasis on social services, was also identified as a programme strength. This included at least one professional having a dedicated leadership role in overseeing the entire transition process and supporting transition stages, such as a transition coordinator. Current literature indicates that there remains a lack of clarity regarding which provider is ultimately responsible for the coordination of care (Bishop et al., 2020). In this review, the care coordinator's role was found to incorporate: youth's health knowledge, the parent's role in transition, a specific plan for transfer of care, and support for the social determinants of health that surround transition‐aged youth (e.g. vocation, education, finances, insurance and housing).

A further strength of transition programmes is organizational or institutional support and a multi‐year duration. This approach was found to facilitate the integration of services, coordination of care, and person‐centred support of youth and their families in their transfer to adult care. The strengths of the articles in this review reflect the person‐centred, clinical, and system‐level recommendations by the CHC transition guidelines, which serve as a framework for a supportive process transitioning from paediatric to adult healthcare (Canadian Association of Pediatric Health Centres [CAPHC] & National Transitions Community of Practice, 2016).

5.2. Areas for improvement