Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by significant social functioning impairments, including (but not limited to) emotion recognition, mentalizing, and joint attention. Despite extensive investigation into the correlates of social functioning in ASD, only recently has there been focus on the role of low‐level sensory input, particularly visual processing. Extensive gaze deficits have been described in ASD, from basic saccadic function through to social attention and the processing of complex biological motion. Given that social functioning often relies on accurately processing visual information, inefficient visual processing may contribute to the emergence and sustainment of social functioning difficulties in ASD. To explore the association between measures of gaze and social functioning in ASD, a systematic review and meta‐analysis was conducted. A total of 95 studies were identified from a search of CINAHL Plus, Embase, OVID Medline, and psycINFO databases in July 2021. Findings support associations between increased gaze to the face/head and eye regions with improved social functioning and reduced autism symptom severity. However, gaze allocation to the mouth appears dependent on social and emotional content of scenes and the cognitive profile of participants. This review supports the investigation of gaze variables as potential biomarkers of ASD, although future longitudinal studies are required to investigate the developmental progression of this relationship and to explore the influence of heterogeneity in ASD clinical characteristics.

Lay Summary

This review explored how eye gaze (e.g., where a person looks when watching a movie) is associated with social functioning in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We found evidence that better social functioning in ASD was associated with increased eye gaze toward faces/head and eye regions. Individual characteristics (e.g., intelligence) and the complexity of the social scene also influenced eye gaze. Future research including large longitudinal studies and studies investigating the influence of differing presentations of ASD are recommended.

Keywords: attention, autism spectrum disorder, cognition, eye gaze, motivation, social functioning, visual processing

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that involves lifelong difficulties, spanning cognitive, behavioral, and emotional domains. Social cognitive and social communicative difficulties are core features of ASD, and broadly encompass the skills required to engage with the social world (Pallathra et al., 2018; Pallathra et al., 2019). Social difficulties have been extensively mapped across the autism spectrum, resulting in a set of common, albeit not universal, impairments in the following areas: the ability to infer the mental states and intentions of others (i.e., theory of mind [ToM]; Leppanen et al., 2018), the direction of attention to shared social experiences (i.e., joint attention; Franchini et al., 2019; Mundy, 2018), face and emotion recognition (Tang et al., 2015; Uljarevic & Hamilton, 2013), empathy (Song et al., 2019), language (Eigsti et al., 2011), and the “global” processing of visual stimuli (Van der Hallen et al., 2015). Collectively, these features can result in difficulties engaging in one's social environment.

These social functioning difficulties cannot be ascribed to an isolated deficit in a specific neural region. Rather, such widespread difficulties are often characteristic of disruptions within the “social brain”, referring to a network of interconnected neural structures involved in social information processing. Relevant nodes include the medial prefrontal cortex (mentalizing ability; Schurz et al., 2014), temporoparietal junction (prosocial decision‐making; Zanon et al., 2014), posterior superior temporal sulcus (biological motion processing; Deen et al., 2015; Pelphrey & Carter, 2008), and fusiform gyrus (face processing; Furl et al., 2011).

Despite extensive examination of social brain regions and their associated behavioral, cognitive, and emotional disturbances in ASD, these studies often fail to examine the sensory inputs required to initially examine and process social information. Of particular interest is visual information processing, given that adequate processing of social information requires that relevant environmental social stimuli are attended to, perceived, and processed in an accurate manner (Griffin & Scherf, 2020). The disruption of visual processing early in development may lead to differences in how socio‐communicative interactions are perceived and acted upon, resulting in potentially inaccurate perceptions and interactions with the social environment (Hellendoorn et al., 2013; Thye et al., 2018).

Dysfunction across multiple levels of the visual processing pathway has been reported in ASD, from basic saccadic eye movements (Mosconi et al., 2013; Schmitt et al., 2014; Stanley‐Cary et al., 2011) to biological motion processing (part of the aforementioned “social brain” network; Annaz et al., 2010; Klin et al., 2009). Additionally, differences in the way in which social gaze is allocated has been demonstrated in ASD. For example, two meta‐analyses conducted by Chita‐Tegmark found that participants with ASD look less at the eyes, mouth, face, and the entire screen on which stimuli are presented, and more time toward the body and nonsocial regions (Chita‐Tegmark, 2016a), and that greater group differences in attending to social stimuli between ASD and neurotypical groups is seen with social stimuli containing more than one person (Chita‐Tegmark, 2016b). However, Frazier et al. (2017) conducted a more comprehensive meta‐analysis, exploring the contributions of stimulus and methodological factors (including participant characteristics, eyetracking parameters, and stimulus features) on the gaze difficulties experienced in ASD. Although results were consistent with previous findings in that those with ASD had reductions in gaze toward eye and mouth regions and greater gaze allocation toward nonsocial regions, meta‐regression analyses revealed the influence of stimulus and methodological factors (e.g., points of calibration, number of stimuli presented). The analysis further revealed ASD‐specific gaze differences in comparison to other developmental delay conditions, indicating the potential clinical utility of assessing gaze toward social and nonsocial stimuli to aid differential diagnosis. Overall, ASD is associated with a pattern of visual exploration in which attending to aspects of the social environment critical to social understanding is affected. This is likely also underpinned, at least in part, by disrupted saccadic functioning given the role it plays in driving the allocation of gaze toward environmental regions of interest (Ibbotson & Krekelberg, 2011; Wollenberg et al., 2020).

The above findings suggest that it is crucial to consider gaze and visual attention when attempting to understand social difficulties in ASD. To date, empirical studies and meta‐analyses have focused on profiling the gaze differences toward social and nonsocial stimuli between ASD and neurotypical controls. These differences, however, may not necessarily translate into difficulties with social functioning. For example, although increased gaze toward the mouth has been associated with declines in social functioning in ASD (e.g., Hanley et al., 2015), Klin et al. (2002) found that gaze toward the mouth was instead associated with improvements in social functioning in ASD. This was considered to be a possible compensatory strategy whereby focusing on the mouth facilitated a literal understanding of speech, and in turn, social situations. Examining how the allocation of gaze across social and nonsocial scenes is associated with social functioning would provide a novel understanding of how gaze is used by individuals with ASD to engage in their social world.

Therefore, the primary purpose of this systematic review was to clarify the nature of social dysfunction in ASD by examining the relationships between gaze allocation and measures of social functioning in ASD, and to identify the factors that contribute to variation in this relationship. This is important to consider as the development of targeted interventions training the allocation of gaze in the social environment may need to be tailored to specific ASD profiles.

METHOD

Search strategy

Selected databases (CINAHL Plus, Embase, OVID Medline, and psycINFO) were searched for articles in July 2021 using the following search terms: [(autis* OR ASD OR Asperger*) AND (eyetracking OR eye‐tracking OR eye tracking OR gaze OR sacc*) AND (social* OR theory of mind OR ToM OR mentali* OR empath* OR imitati* OR face recog* OR emotion recog*)], where “*” represented truncations.

Study selection and eligibility

In order to be eligible, articles needed to (a) contain an ASD group with or without a comparison control group, (b) use either standardized clinical measures or clinical assessment for the ASD diagnosis, (c) examine the link between gaze and social function, (d) include at least one eyetracking measure or coded measure of gaze and one objective/validated measure of social functioning, (e) contain peer reviewed, empirical data, (f) include a sample size of at least 10 in each group, and (g) be written in English. No limits were placed on the age or gender of the participants. Additionally, results were included that also incorporated other participant groups within analyses (e.g., neurotypical). Cross‐sectional and longitudinal designs were included, in addition to studies that included a baseline measure of the relationship between gaze and social functioning in the context of intervention research.

Studies were initially screened by JR for inclusion based on review of titles and abstracts. Selected studies then proceeded to full‐text review for final inclusion. Reference lists were further reviewed for the inclusion of additional studies. Any uncertainties were resolved via consultation with CG and PE.

Quantitative analysis

To provide a quantitative estimate of the correlation between gaze and social functioning/autism symptom severity, separate meta‐analyses were performed for three core gaze regions (i.e., face, eyes, and mouth). Subgroup analyses and, for eligible regions, meta regressions were performed to identify potential modifiers of the overall combined correlation effect estimate. All analyses were performed in R 4.1.0 (R Core Team, 2017) using rma.mv and metafor functionalities.

Study inclusion/exclusion criteria

A combination approach was employed for all meta‐analyses to (1) minimize and (2) accommodate heterogeneity among studies (e.g., different measures of broad social functioning/autism symptom severity, subgroup versus global measurement of ASD, operationalizations of gaze measure, type of reported summary effect estimate, task conditions, such as emotional images vs. non‐emotional images) and dependence of effect estimates within studies (e.g., one study contributing > 1 estimate to the meta‐analysis).

To minimize heterogeneity, inclusion/exclusion criteria were further applied to studies included in the systematic review. In terms of exclusion for gaze measure, studies were retained that examined fixation duration/looking time (both percentages and absolute values), given that this remains the most commonly reported gaze index consistent with Chita‐Tegmark (2016a). Additionally, studies were limited to those that reported a global autism symptom severity score (e.g., Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule [ADOS] Global score, Social Responsiveness Scale [SRS] Total score). In the case that a study reported a global estimate and subgroup estimate(s), only the global estimate was used in the meta‐analysis. As there were no studies that included global measures of social functioning (i.e., not including restricted/repetitive behavior as part of the total score), analysis was limited to measures of global autism symptom severity. To minimize dependence among effect estimates, for studies that reported > 1 effect estimate of the association between gaze and autism symptom severity due to the use of > 1 different global measure of autism symptom severity (but the same fixation duration/looking time gaze index), only one estimate was retained. Notably, each of the applicable studies included the ADOS Global score, and therefore, given its status as a gold standard approach in the assessment and diagnosis of ASD (Harstad et al., 2015; Kamp‐Becker et al., 2018), this was selected for the meta‐analysis. With respect to inclusion/exclusion criteria associated with the type of effect estimate, statistics listed in Supplementary Materials 1 in Data S1 were retained, with the understanding that some summary statistic types would require conversion into a correlational form (i.e., point biserial correlation or Pearson r) prior to meta‐analysis. Additionally, studies were retained if they examined the relationship between gaze and global measures of autism symptom severity in an ASD only group, in line with the overarching study goal of exploring this association within an ASD population. Remaining inclusion/exclusion criteria and further detail can be seen in Supplementary Materials 1 in Data S1.

The application of inclusion/exclusion criteria meant that studies only contributed more than one effect estimate of interest as a result of differing task conditions (e.g., White et al., 2015 examined the association separately for happy, disgust, and angry faces). After study level inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied, regions were deemed eligible for meta‐analysis if they had at least 10 estimates (not studies) available. This resulted in three eligible regions: face, eyes, and mouth.

Meta‐analysis: Data preparation and model specification

Prior to performing the meta‐analysis, correlations reported in studies (i.e., partial, Spearman, Pearson, bivariate standardized beta coefficient) were directly converted to Fisher z scores and corresponding sampling variances (escalc function in R). Cohen's d associated with between subjects t tests were converted to point biserial correlation prior to conversion to Fisher z (sampling variance uniquely computed in such case). When studies failed to report group size, equal size was assumed. A square root transformation for partial R 2 or R 2 reported in studies was applied to obtain Pearson r before conversion to Fisher z.

To accommodate dependence of study effect estimates, a multivariate/multilevel, random effects meta‐analysis was performed for each region, with a random effect for each level of the study variable (i.e., for each study). Models were fit using restricted maximum likelihood. A single study reporting R 2 failed to report indication of r directionality (Murias et al., 2018) across the three regions. In lieu of excluding the study, meta‐analyses were conducted for both a positive and negative direction for this study's Pearson r value for each region. Additionally for the face region, given the lack of indication of whether samples used in the two Riby and Hancock studies were the same, our analyses assumed, and thus modeled them, as different samples (Riby & Hancock, 2009a; Riby & Hancock, 2009b). The final combined Fisher z correlation effect estimate and confidence interval produced for each meta‐analysis was then converted to a Pearson correlation coefficient estimate using the following formula:

Cochran's Q test based on the chi‐square distribution was used to evaluate the presence of heterogeneity. Funnel plots provide a means of assessing the presence of publication bias by modeling effect size estimates relative to precision of the estimate. The present study did not employ this method of evaluation given plots do not take into account dependence among multiple effects from the same study and thus papers that provide multiple effects would unduly impact symmetry, negating the value of interpreting symmetry.

Meta‐regression: Participant and task characteristics

If significant heterogeneity was detected for a region in the meta‐analysis model (Cochran's Q test p < 0.05), bivariate meta‐regressions were performed for that region to identify study characteristics that explain heterogeneity in the overall effect size estimate. A total of 10 continuous (*) and categorical (**) explanatory variables (autism symptom severity measure rater**, % females in the sample*, emotional vs. non‐emotional task condition**, number of people in the scene**, points of calibration**, whether the task was static or dynamic**, eyetracker sampling rate**, unique regions of interest in stimuli**, total number of trials**, and age* [in years]) were meta‐regressed for eligible regions, provided that there were 10 or more non‐missing values in the region‐specific predictor (Cochrane Training, n.d.). These counts can be found in Supplementary Table 1 in Data S1. Definitions and region‐level summary statistics for predictors can be found in Supplementary Materials 2 and Supplementary Table 1 in Data S1, respectively. Multiple predictors could not be investigated simultaneously in a model (i.e., multiple meta‐regression) due to an inadequate number of estimates per region (Cochrane Training, n.d.). For bivariate meta‐regression models, a single explanatory variable was added to the basic intercept model with no fixed effect predictors used to perform the meta‐analysis. Only statistics linked to significant predictors are reported (p < 0.05) in main body results.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

A risk of bias assessment was conducted using the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale, adapted for cross‐sectional studies (Modesti et al., 2016). A detailed overview of the risk of bias assessment tailored for the current analysis is in Supplementary Table 2 in Data S1, and an estimate‐level summary of risk of bias levels per region of interest (ROI) is included in Supplementary Table 1 in Data S1. Effect statistics from studies evaluated as possessing different levels of risk of bias were all included in the calculation of the combined effect estimate for each region. Additionally, combined estimates were derived based on a range of different correlation types, in place of restricting to Pearson correlation coefficient. These decisions were made in the interest of maximizing sample size of the meta‐analysis. Analysis results may be impacted by the assumption of comparability among correlation type. Partial correlations which control for covariate(s) are often attenuated relative to Pearson correlations and Spearman correlations are considered a good approximation of Pearson under specific conditions (e.g., large sample size; de Winter et al., 2016). In turn, sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate how conclusions may be impacted when only considering Pearson correlation coefficients. Subgroup analyses were performed to compare the overall effect estimate derived from studies with unsatisfactory levels of bias to studies with satisfactory levels of bias.

RESULTS

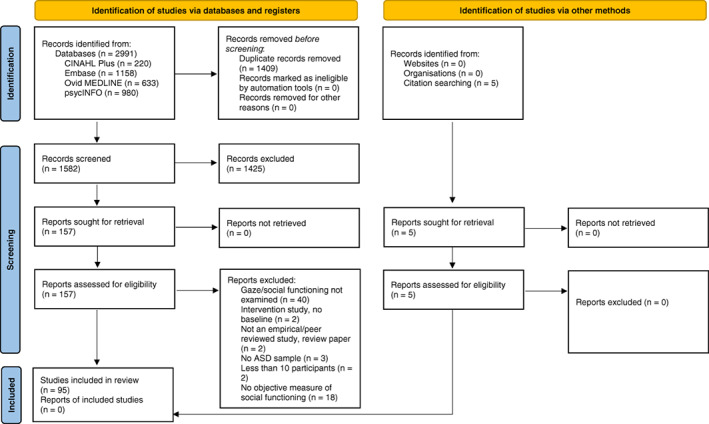

From a total of 2991 articles initially identified, 95 met inclusion criteria and were included (refer to Figure 1 for PRISMA flowchart; Page et al., 2021). To achieve our aim of understanding how gaze allocation is related to social functioning in ASD, results were initially grouped and examined by gaze measure. Gaze measures were coded by the type of eyetracking paradigm employed: free viewing (where participants were not instructed to allocate gaze toward predetermined regions of interest), visual search (where participants were instructed to locate a predetermined target of interest), and saccadic paradigms (where participants were required to shift their gaze in response to visual stimuli). An overview of gaze measures used across studies can be seen in Table 1. For free viewing measures, results were further classified by the ROI in which gaze was allocated (see Table 2), including single ROIs (face, eyes, mouth, nose, hand, head, body, people, object, background, overall stimulus) and multiple ROIs (dual social/nonsocial stimuli, face vs. non‐face, eyes vs. mouth). Studies were further defined by the type of visual stimulus used to assess visual processing function (i.e., dynamic vs. static, social vs. nonsocial). Dynamic stimuli involved a moving sequence of events, while static stimuli involved still images. Social stimuli reflected the presence of at least one human, while nonsocial stimuli involved the presence of nonhuman related activities and images.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

TABLE 1.

List of gaze measures employed across studies by task

| Gaze measure | Studies |

|---|---|

| Free viewing | |

| Eye contact | |

| Duration | Jones et al. (2017). |

| Frequency | Jones et al. (2017). |

| Dwell/looking time | Bacon et al. (2020), Campbell et al. (2014), Chawarska and Shic (2009), Chawarska et al. (2012), Chawarska et al. (2016), Crawford et al. (2015), Crehan and Althoff (2021), Crehan et al. (2020), Cuve et al. (2021), Frazier et al. (2016), Frazier et al. (2018), Groen et al. (2012), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Macari et al. (2021), Murias et al. (2018), Nadig et al. (2010), Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019), Sasson et al. (2007), Sawyer et al. (2012), Shic et al. (2011), Shic et al. (2020). |

| Dynamic scanning index | Wilson et al. (2012). |

| Entropy | |

| Gaze transition entropy | Cuve et al. (2021). |

| Stationary gaze entropy | Cuve et al. (2021). |

| Eye fixation points | Ohya et al. (2014). |

| Gaze allocation | Amso et al. (2014). |

| Gaze following | Sumner et al. (2018). |

| Gaze shifts (no. correct) | Franchini et al. (2017). |

| Gaze similarity | Avni et al. (2020), Tenenbaum et al. (2021), Wang et al. (2018). |

| Fixation | |

| Change | Kliemann et al. (2010). |

| Count/number/percentage/proportion | Bast et al. (2021), Corden et al. (2008), Crehan and Althoff (2021), Cuve et al. (2021), Fedor et al. (2018), Hanley et al. (2015), Kou et al. (2019), McPartland et al. (2011), Rigby et al. (2016), Snow et al. (2011), Unruh et al. (2016), Vivanti et al. (2014). |

| Duration/time | Amestoy et al. (2015), Asberg Johnels et al. (2017), Avni et al. (2020), Bast et al. (2021), Bird et al. (2011), Bradshaw et al. (2019), Chawarska and Shic (2009), Cole et al. (2017), Crehan and Althoff (2021), Crehan et al. (2020), Cuve et al. (2021), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Fedor et al. (2018), Franchini et al. (2016), Frost‐Karlsson et al. (2019), Fujioka et al. (2016), Fujioka et al. (2020), Gillespie‐Smith, Doherty‐Sneddon, et al. (2014), Gillespie‐Smith, Riby, et al. (2014), Greene et al. (2020), Griffin and Scherf (2020), Grynszpan and Nadel (2014), Hanley et al. (2014), Jones et al. (2008), Jones and Klin (2013), Kirchner et al. (2011), Klin et al. (2002), Kou et al. (2019), Moore et al. (2018), Muller et al. (2016), Norbury et al. (2009), Parish‐Morris et al. (2013), Pierce et al. (2011), Pierce et al. (2016), Riby and Hancock (2009a), Riby and Hancock (2009b), Riby et al. (2013), Rice et al. (2012), Rigby et al. (2016), Sasson et al. (2016), Shaffer et al. (2017), Speer et al. (2007), Sumner et al. (2018), Swanson and Siller (2013), Thorup et al. (2017), Unruh et al. (2016), White et al. (2015), Wieckowski and White (2016), Xavier et al. (2015), Zamzow et al. (2014), Zantinge et al. (2017). |

| Latency | Crawford et al. (2015), Frost‐Karlsson et al. (2019), Gillespie‐Smith, Doherty‐Sneddon, et al. (2014), Gillespie‐Smith, Riby, et al. (2014), Hanley et al. (2014), Sumner et al. (2018), Unruh et al. (2016). |

| Likelihood | Del Bianco et al. (2021). |

| Responsive search score | Ohya et al. (2014). |

| Saccadic indices | |

| Amplitude | Cuve et al. (2021). |

| Amplitude, duration, peak velocity, velocity main sequence | Bast et al. (2021). |

| Number | Xavier et al. (2015). |

| Total eye scanning length | Ohya et al. (2014). |

| Visual exploration | Sasson et al. (2008). |

| Visual search | |

| Fixation duration | Wang et al. (2020). |

| Latency | Glennon et al. (2020). |

| Looking time (target) | Bavin et al. (2014). |

| Saccadic error | Keehn and Joseph (2016). |

| Search asymmetry | Keehn and Joseph (2016). |

| Search intercept | Joseph et al. (2009). |

| Search slope | Joseph et al. (2009). |

| Saccadic paradigms | |

| Antisaccade | |

| Error rate | DiCriscio et al. (2016). |

| Latency | DiCriscio et al. (2016). |

| Distractor task | |

| Accuracy | Lindor et al. (2019). |

| Predictive saccades | |

| Visit count (violation trials) | Greene et al. (2019). |

| Prosaccade | |

| Accuracy | Zalla et al. (2016). |

| Disengagement, gap effect | Keehn et al. (2019), McLaughlin et al. (2021). |

| Facilitation (gap‐baseline) | Glennon et al. (2020). |

| Gaze cueing | Kuhn et al. (2010). |

| Latency | DiCriscio et al. (2016), Zalla et al. (2016). |

| Variability | Zalla et al. (2016). |

| Velocity | Zalla et al. (2016). |

TABLE 2.

List of regions of interest employed by free viewing studies

| Region of interest | Studies |

|---|---|

| Face/head (N = 33) | Avni et al. (2020), Chawarska and Shic (2009), Chawarska et al. (2012), Cole et al. (2017), Del Bianco et al. (2021), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Gillespie‐Smith, Riby, et al. (2014), Greene et al. (2020), Griffin and Scherf (2020), Grynszpan and Nadel (2014), Hanley et al. (2014), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Kirchner et al. (2011), Macari et al. (2021), Murias et al. (2018), Nadig et al. (2010), Parish‐Morris et al. (2013), Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019), Riby and Hancock (2009a), Riby and Hancock (2009b), Rigby et al. (2016), Sasson et al. (2007), Sasson et al. (2016), Shic et al. (2011), Shic et al. (2020), Snow et al. (2011), Sumner et al. (2018), Swanson and Siller (2013), Vivanti et al. (2014), White et al. (2015), Wilson et al. (2012), Xavier et al. (2015), Zantinge et al. (2017). |

| Eyes (N = 32) | Amestoy et al. (2015), Asberg Johnels et al. (2017), Avni et al. (2020), Chawarska and Shic (2009), Corden et al. (2008), Crawford et al. (2015), Crehan and Althoff (2021), Crehan et al. (2020), Cuve et al. (2021), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Fedor et al. (2018), Fujioka et al. (2016), Fujioka et al. (2020), Gillespie‐Smith, Doherty‐Sneddon, et al. (2014), Hanley et al. (2014), Hanley et al. (2015), Jones et al. (2008), Jones and Klin (2013), Jones et al. (2017), Kirchner et al. (2011), Klin et al. (2002), McPartland et al. (2011), Muller et al. (2016), Murias et al. (2018), Norbury et al. (2009), Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019), Rice et al. (2012), Sawyer et al. (2012), Speer et al. (2007), White et al. (2015), Wieckowski and White (2016), Zamzow et al. (2014). |

| Mouth (N = 23) | Amestoy et al. (2015), Asberg Johnels et al. (2017), Chawarska and Shic (2009), Chawarska et al. (2012), Corden et al. (2008), Cuve et al. (2021), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Fedor et al. (2018), Fujioka et al. (2016), Fujioka et al. (2020), Gillespie‐Smith, Doherty‐Sneddon, et al. (2014), Hanley et al. (2015), Jones et al. (2008), Kirchner et al. (2011), Klin et al. (2002), Muller et al. (2016), Murias et al. (2018), Norbury et al. (2009), Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019), Rice et al. (2012), Sawyer et al. (2012), Wieckowski and White (2016), Zamzow et al. (2014). |

| Nose (N = 4) | Chawarska and Shic (2009), Cuve et al. (2021), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Zamzow et al. (2014). |

| Hand (N = 2) | |

| Body (N = 7) | Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Jones et al. (2008), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Klin et al. (2002), Muller et al. (2016), Sasson et al. (2007), Speer et al. (2007). |

| People (N = 4) | Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Frost‐Karlsson et al. (2019), Murias et al. (2018), Shic et al. (2011). |

| Global scene (N = 10) | Avni et al. (2020), Bast et al. (2021), Chawarska et al. (2012), Chawarska et al. (2016), Cuve et al. (2021), Griffin and Scherf (2020), Murias et al. (2018), Shic et al. (2011), Tenenbaum et al. (2021), Wang et al. (2018). |

| Object and nonbiological targets (N = 22) | Cole et al. (2017), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Franchini et al. (2017), Fujioka et al. (2020), Gillespie‐Smith, Riby, et al. (2014), Greene et al. (2020), Griffin and Scherf (2020), Jones et al. (2008), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Klin et al. (2002), Muller et al. (2016), Murias et al. (2018), Ohya et al. (2014), Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019), Riby et al. (2013), Rice et al. (2012), Sasson et al. (2008), Shic et al. (2011), Snow et al. (2011), Swanson and Siller (2013), Thorup et al. (2017), Vivanti et al. (2014). |

| Background (N = 3) | Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Shic et al. (2011). |

| Face versus non‐face (N = 4) | Amso et al. (2014), Bird et al. (2011), Chawarska et al. (2016), Greene et al. (2020). |

| Eyes versus mouth (N = 6) |

Bird et al. (2011), Bradshaw et al. (2019), Chawarska and Shic (2009), Chawarska et al. (2016), Gillespie‐Smith, Doherty‐Sneddon, et al. (2014), Kliemann et al. (2010). |

| Dual social and nonsocial stimuli (N = 18) | Bacon et al. (2020), Bradshaw et al. (2019), Campbell et al. (2014), Chawarska and Shic (2009), Chawarska et al. (2016), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Franchini et al. (2016), Frazier et al. (2016), Frazier et al. (2018), Fujioka et al. (2016), Fujioka et al. (2020), Groen et al. (2012), Kou et al. (2019), Moore et al. (2018), Pierce et al. (2011), Pierce et al. (2016), Shaffer et al. (2017), Unruh et al. (2016). |

| Biological motion displays (N = 4) | Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Fujioka et al. (2016), Fujioka et al. (2020), Kou et al. (2019). |

Social functioning measures included clinical autism measures (social domain and total scores), behavioral functioning (social subscales), social impairment, and performance on social functioning tasks (including emotion recognition, face recognition, gender identification, joint attention, and ToM). Additionally, three studies created composite measures of social functioning from individual tasks/scales. An overview of these can be found in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

List of social functioning and autism symptom severity measures used across studies

| Social functioning/autism symptom severity measure | Studies |

|---|---|

| Autism symptom scales | |

| Autism Behavior Checklist (Volkmar et al., 1988) | |

| Total | Wang et al. (2020). |

| Autism Behavior Inventory (Bangerter et al., 2017, 2019) | |

| Social communication | Kaliukhovich et al. (2020). |

| Core ASD symptom scale | Kaliukhovich et al. (2020). |

| Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised (ADI‐R; Lord et al., 1994; Rutter et al., 2003) | |

| Reciprocal social interaction | Amestoy et al. (2015), Grynszpan and Nadel (2014), Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019), Tenenbaum et al. (2021), Zalla et al. (2016). |

| Social affect | Bast et al. (2021). |

| Social interaction | Keehn and Joseph (2016). |

| Social score | Kirchner et al. (2011), Kliemann et al. (2010), Speer et al. (2007), Zamzow et al. (2014), Zantinge et al. (2017). |

| Total | Kliemann et al. (2010). |

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS, ADOS‐2, ADOS‐G, ADOS‐T; Hus et al., 2011; Lord et al., 1989; Lord et al., 1999; Lord et al., 2000; Lord et al., 2002; Lord, Luyster, et al., 2012; Lord, Rutter, et al., 2012; Luyster et al., 2009) | |

| Communication and social interaction | Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018). |

| Comparison score | Avni et al. (2020). |

| Reciprocal social interaction | Corden et al. (2008), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), DiCriscio et al. (2016), Groen et al. (2012), Zalla et al. (2016). |

| Severity score | Rice et al. (2012), Zantinge et al. (2017). |

| Severity score (calibrated) | Bast et al. (2021), Fedor et al. (2018), Keehn et al. (2019), Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019), Tenenbaum et al. (2021). |

| Social | Joseph et al. (2009), Norbury et al. (2009), Speer et al. (2007). |

| Social affect | Amso et al. (2014), Bast et al. (2021), Frazier et al. (2016), Jones and Klin (2013), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Kou et al. (2019), Macari et al. (2021), Moore et al. (2018), Pierce et al. (2011), Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019), Shic et al. (2011), Wang et al. (2018). |

| Social affect (calibrated severity score) | Bast et al. (2021), Jones et al. (2017). |

| Social affect/communication | Pierce et al. (2016). |

| Social algorithm | Jones et al. (2008), Klin et al. (2002). |

| Social communication | McLaughlin et al. (2021), Unruh et al. (2016), Vivanti et al. (2014). |

| Social interaction | Keehn and Joseph (2016). |

| Symptom severity | Bird et al. (2011), Franchini et al. (2016), Frazier et al. (2016), Frazier et al. (2018), Murias et al. (2018), Unruh et al. (2016). |

| Total algorithm score | Shic et al. (2020). |

| Total score (calibrated severity score) | Bast et al. (2021), Bradshaw et al. (2019), Griffin and Scherf (2020), Shic et al. (2020). |

| Total score (module 1) | Campbell et al. (2014). |

| Global/total score | Amestoy et al. (2015), Avni et al. (2020), Bacon et al. (2020), Chawarska et al. (2012), Chawarska et al. (2016), Corden et al. (2008), Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018); Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Kou et al. (2019), McLaughlin et al. (2021), Moore et al. (2018), Nadig et al. (2010), Pierce et al. (2011), Pierce et al. (2016), Thorup et al. (2017). |

| Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ; Ehlers et al., 1999) | |

| Total score (caregiver rated, teacher rated) | Ohya et al. (2014). |

| Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ, AQ28; Baron‐Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, et al., 2001; Baron‐Cohen et al., 2006; Hoekstra et al., 2011) | |

| Total score | Asberg Johnels et al. (2017), Corden et al. (2008), Cuve et al. (2021), Kuhn et al. (2010), Rigby et al. (2016). |

| Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler et al., 1998) | |

| Total | Gillespie‐Smith, Doherty‐Sneddon, et al. (2014), Gillespie‐Smith, Riby, et al. (2014), Grynszpan and Nadel (2014), Riby and Hancock (2009a), Riby and Hancock (2009b), Riby et al. (2013). |

| Pervasive Developmental Disorder Behavior Inventory (PDD‐BI; Cohen et al., 2003) | |

| Expressive/receptive social communication | Murias et al. (2018), Tenenbaum et al. (2021). |

| Autism composite | Murias et al. (2018), Tenenbaum et al. (2021). |

| Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ; Rutter et al., 2003) | |

| Social subscale | Sasson et al. (2008). |

| Total score | Bavin et al. (2014), Crawford et al. (2015), Gillespie‐Smith, Doherty‐Sneddon, et al. (2014), Gillespie‐Smith, Riby, et al. (2014), Greene et al. (2019), Parish‐Morris et al. (2013), Shaffer et al. (2017), Sumner et al. (2018), Vivanti et al. (2014). |

| Behavioral scales | |

| Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC; Aman et al., 1985) | |

| Lethargy/social withdrawal subscale | Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Shaffer et al. (2017), Tenenbaum et al. (2021). |

| Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd Edition (BASC‐2; Goldin et al., 2014) | |

| Social skills | Murias et al. (2018). |

| Five to Fifteen (FTF; Kadesjo et al., 2004) | |

|

Social competence subscale |

Frost‐Karlsson et al. (2019). |

| Composite measures | |

| Autism traits | |

| Principal components analysis of Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS‐2; Lord et al., 2000), Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Constantino et al., 2003 ), The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT; McDonald et al., 2006 ), and Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ; Baron‐Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, et al., 2001 ). | Cole et al. (2017). |

| Face processing accuracy | |

| Composite of Let us Face It! Matching Identity Across Expression and Matchmaker Expression Subtests (Tanaka et al., 2012; Wolf et al., 2008 ) | Parish‐Morris et al. (2013). |

| Theory of Mind Battery | |

| Unexpected contents first‐order false‐belief task (Smarties Task; Wimmer & Hartl, 1991 ), unexpected location first‐order false belief task (Sally and Andy Task; Wimmer & Perner, 1983 ), belief desire reasoning task (Nice Surprise Task; Harris et al., 1989 ), unexpected location second‐order false‐belief task (Grandad Story; Perner & Wimmer, 1985 ) | Hanley et al. (2014). |

| Emotion Recognition Tasks | |

| Dynamic emotional face paradigm | Cuve et al. (2021). |

| Ekman‐Friesen test of facial affect recognition (Ekman & Friesen, 1976) | |

| Happy, sad, angry, surprised, disgusted, fear recognition | Corden et al. (2008). |

| Emotion classification task | |

| Total | Kliemann et al. (2010). |

| Emotions in context task | |

| Accuracy | Sasson et al. (2016). |

| Emotion recognition task/s | |

| Accuracy | Wieckowski and White (2016), Xavier et al. (2015). |

| Accuracy (basic expression, complex expression) | Sawyer et al. (2012). |

| Free choice response expression task | |

| Accuracy | Wieckowski and White (2016). |

| Penn Emotion Recognition Task (ER‐40; Gur et al., 2002) | |

| Composite score | Greene et al. (2020). |

| Social scenes task (emotion recognition) | |

| Accuracy | Sasson et al. (2007). |

| Face recognition tasks | |

| Cambridge Face Memory Test (CFMT; Duchaine & Nakayama, 2006) | |

| Immediate recognition, delayed recognition | Fedor et al. (2018). |

| Total | Kirchner et al. (2011). |

| Face‐fan memory task | |

| Recognition accuracy | Snow et al. (2011). |

| Face recognition test | |

| Accuracy | Wilson et al. (2012). |

| Visual Paired Comparison paradigm (VPC; Fantz, 1964) | |

| Familiar, novel, novelty preference ratio | Chawarska and Shic (2009). |

| Gender identification | |

| Mind in the Eyes: Gender task (Baron‐Cohen, Wheelwright, Scahill, et al., 2001) | |

| Total correct | McPartland et al. (2011). |

| Joint attention tasks | |

| Early Social Communication Scale (ESCS; Mundy et al., 2003) | |

| Total correct | Franchini et al. (2017). |

| Social functioning scales | |

| Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition (MASC; Dziobek et al., 2006) | |

| Total | Muller et al. (2016). |

| Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS; Gresham & Elliott, 2008) | |

| Social skills (parent report) | Griffin and Scherf (2020). |

| Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS, SRS‐2; Constantino & Gruber, 2002, 2005, 2012; Constantino et al., 2003) | |

| Parent/caregiver rated | Bacon et al. (2020). |

| Autistic mannerisms subscale | Hanley et al. (2015), Shaffer et al. (2017). |

| Social awareness subscale | Hanley et al. (2015), Shaffer et al. (2017), Swanson and Siller (2013). |

| Social cognition subscale | Hanley et al. (2015), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Shaffer et al. (2017). |

| Social communication subscale | Hanley et al. (2015), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Shaffer et al. (2017). |

| Social communication and interaction | Kaliukhovich et al. (2020). |

| Social motivation subscale | Hanley et al. (2015), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Shaffer et al. (2017). |

| Total | Bast et al. (2021), Crehan and Althoff (2021), Del Bianco et al. (2021), Frazier et al. (2016), Frazier et al. (2018), Fujioka et al. (2020), Glennon et al. (2020), Greene et al. (2020), Griffin and Scherf (2020), Hanley et al. (2015), Jones et al. (2017), Kaliukhovich et al. (2020), Keehn et al. (2019), Lindor et al. (2019), McLaughlin et al. (2021), Shaffer et al. (2017), Speer et al. (2007), Thorup et al. (2017), Unruh et al. (2016), White et al. (2015). |

| Self‐rated | |

| Total | Bast et al. (2021), Fujioka et al. (2016), Greene et al. (2019), Greene et al. (2020). |

| Theory of mind tasks | |

| Hinting Task (Corcoran et al., 1995) | |

| Total | Greene et al. (2020). |

| Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET; Baron‐Cohen, Wheelwright, Hill, et al., 2001) | |

| Total | Kirchner et al. (2011). |

| Theory of Mind Inventory—Second Edition, self‐report (ToMI‐2‐SR; Hutchins et al., 2014) | |

| Early, basic, advanced | Crehan and Althoff (2021), Crehan et al. (2020). |

| Total | Crehan and Althoff (2021). |

Results are presented by the type of eyetracking paradigm employed, with the free viewing studies further classified by ROI.

Free viewing studies

Individual interest areas

Biological interest areas

Face/head

A total of 33 studies examined the face/head ROI, with 20 identifying significant relationships between gaze toward the face and social functioning/autism symptom severity. Of these, 13 demonstrated significant relationships where reductions in looking time toward the face ROI was associated with decreased social functioning/increased autism symptom severity (refer to Table 4). Three studies found the opposite relationship. Sasson et al. (2007) found that increased gaze duration to the face was associated with reductions in emotion accuracy in ASD. Results indicated that the level of engagement with the face/head stimuli was also relevant to the association between gaze and social functioning/autism symptom severity. Chawarska and Shic (2009) found that increased gaze allocation to the face was associated with poorer face recognition performance (on the Visual Paired Comparison paradigm; Fantz, 1964) in participants with ASD, reflective of restricted scanning of internal facial features, while Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018) found that increased gaze toward the face during a gender discrimination task was associated with higher scores on the ADOS Reciprocal and Social Interaction and ADOS Communication and Social Interaction domains.

TABLE 4.

Summary of findings—Face/head region (N = 33)

| Reference | Visual processing index | Visual stimuli | Interest area | Social function/autism trait measure | Participant characteristics | Other clinical groups in analysis? | Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Diagnosis | Sex | Age M(SD) | IQ/DQ/mental age | Language | |||||||

| Avni et al. (2020) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Face |

ADOS‐2 (Total score) |

71 | ASD | 59 Males, 12 Females |

5.1 years (1.8 years) |

‐ | ‐ | No | ns |

| Chawarska and Shic (2009) | Looking time (familiar, novel preference), fixation duration (novelty preference ratio) | Static, social |

Face (inner) |

VPC (familiar preference) |

14 Age Group 1, 30 Age Group 2 | 27 Autism, 17 PDD‐NOS | 84% Males |

Age Group 1 26.9 months (6.2 months) Age Group 2 46.4 months (6.4 months) |

Age Group 1 VDQ: 61 (37), NVDQ: 85 (24) Age Group 2 VDQ: 66 (36), NVDQ: 76 (25) |

‐ | No |

Positive correlation (controlling for CA, VDQ, NVDQ) |

| VPC (novel preference, novelty preference ratio) |

ns (controlling for CA, VDQ, NVDQ) |

|||||||||||

| Face (outer) |

VPC (familar preference, novel preference, novelty preference ratio) |

ns (controlling for CA, VDQ, NVDQ) |

||||||||||

| Chawarska et al. (2012) | Looking time | Dynamic, social | Face | ADOS‐G (Total score) | 54 | Autism | 85% Males | 21.6 months (2.9 months) |

VMA: 9.1 months (5.8 months) NVMA: 16.6 months (4.5 months) |

EL‐RL Split: 8.1 (23.4) |

No | ns |

| Cole et al. (2017) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social (implicit mentalizing: mentalizing‐action, mentalizing‐either; explicit mentalizing: mentalizing vs. non‐mentalizing) | Head | Autism Traits (principal components analysis of ADOS‐2, AQ, SRS, TASIT) | 17 ASD, 17 NT | ASD (14 Asperger's, 3 ASD), NT |

ASD 10 Males 7 Females NT 10 Males, 7 Females |

ASD 23.71 years (9.24 years) NT 23.71 years (9.07 years) |

ASD WASI IQ: 120.12 (9.32) WASI Verbal Score: 62.88 (6.66) NT WASI IQ: 120.00 (10.09) WASI Verbal Score: 61.61 (7.52) |

‐ | Yes (NT) |

ns |

| Del Bianco et al. (2021) | Fixation likelihood | Static, social | Head | SRS‐2 (T‐score, time 1) |

Cluster 1 294 AUT Cluster 2 25 AUT |

AUT |

Cluster 1 2.87 (Male: Female) Cluster 2 2.00 (Male: Female) |

Cluster 1 16.43 years (5.84 years) Cluster 2 16.03 years (6.43 years) |

Cluster 1 FSIQ: 103.33 (15.92) Cluster 2 FSIQ: 104.14 (10.51) |

‐ | No |

Cluster 1 ns (intercept, slope, quadratic, cubic) Cluster 2 Positive correlation (quadratic component), ns (intercept, slope, cubic) (age corrected correlations) |

| Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018) | Fixation duration |

Static, social (gaze discrimination) Static, social (gender discrimination) |

Inside the face |

ADOS (Total, RSI, CSI), ABC (L/SW) ADOS (RSI, CSI) ADOS (Total), ABC (L/SW) |

38 | ASD | 38 Males | 24.2 years (5.8 years) | FSIQ: 101.1 (14.3), VIQ: 100.5 (16.1), PIQ: 100.6 (12.7) | ‐ | No | ns |

| Positive correlation | ||||||||||||

| ns | ||||||||||||

| Gillespie‐Smith, Riby, et al. (2014) | Fixation duration, first fixation latency | Static social/nonsocial | Face | CARS, SCQ | 21 | ASD | 20 Males, 1 Female | 13 years, 7 months (30 months) |

BPVS‐II VA: 74 (27) RCPM NVA: 27 (7) |

‐ | No | ns |

| Greene et al. (2020) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Face | Hinting Task, ER‐40, SRS‐2 (caregiver/self) |

SCIT‐A: 20 TAU: 21 |

ASD |

SCIT‐A 15 Males, 5 Females TAU 19 Males, 2 Females |

SCIT‐A 17.25 years (3.58 years) TAU 17.90 years (4.1 years) |

SCIT‐A FSIQ: 95.85 (16.53) TAU FSIQ: 114.90 (12.83) |

‐ | No | ns |

| Griffin and Scherf (2020) | Fixation duration |

Dynamic, social (gaze following task) Static, social (gaze perception task) |

Face | ADOS‐2 (Total CSS), SRS‐2 (Total), SSIS‐p (Social Skills). | 35 | ASD | 29 Males, 6 Females | 13.5 years (2.7 years) | VIQ: 96.8 (17.7); PIQ: 102.4 (14.2); FSIQ: 100.1 (15.7) | ‐ | No | ns |

| Grynszpan and Nadel (2014) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Face (gaze contingent) |

ADI‐R (RSI), CARS |

11 | Autism | 9 Males, 2 Females | 21.36 years (4.41 years) |

VIQ: 88.91 (15.33) RPM: 47.03 (10.01) |

‐ | No | Negative correlation |

| Hanley et al. (2014) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Face | ToM composite |

ASD: 17 SLI: 14 NT: 16 |

ASD, SLI, NT |

ASD 11 Males, 6 Females SLI 12 Males, 2 Females NT 6 Males, 10 Females |

ASD 121 months (25 months) SLI 115.2 months (10 months) NT 119.6 months (8 months) |

ASD VA: 84.5 (12.1) NVA: 92.9 (13.764) SLI VA: 84.4 (5.8) NVA: 93.79 (6.852) NT VA: 94.06 (8.621) NVA: 95.56 (7.174) |

‐ | Yes (SLI, NT) |

ns (first order correlation) |

| Fixation latency (anticipatory gaze) |

Negative correlation (controlling for age, verbal ability) |

|||||||||||

| Kaliukhovich et al. (2020) | Looking time | Dynamic, social | Heads (mutual gaze) | ADOS‐2 (Social Affect, Total) | 107 | ASD | 80 Males, 27 Females | 14.6 years (8.0 years) | KBIT‐2 IQ composite: 98.4 (19.9) | ‐ | No |

Negative correlation (controlling for age, sex, IQ) |

| ABC (L/SW), ABI (Symptom Scale, Social Communication), SRS‐2 (Total) |

ns (controlling for age, sex, IQ) |

|||||||||||

| Heads (shared focus) |

ABI, ABC (L/SW), ADOS‐2, SRS‐2 (Total) |

120 | ASD | 91 Males, 29 Females | 14.6 years (8.0 years) | KBIT‐2 IQ Composite: 98.9 (19.9) | ‐ |

ns (controlling for age, sex, IQ) |

||||

| Kirchner et al. (2011) | Fixation duration |

Static, social (MET: emotion recognition and face identity average) |

Face | ADI‐R (Social Score), CFMT, RMET | 20 | ASC | 15 Males, 5 Females | 31.9 years (7.6 years) | W‐IQ: 112.6 (11.6) | ‐ | No | ns |

| Macari et al. (2021) | Looking time | Dynamic, social (dyadic bid/tickle conditions, 6 months) | Face | ADOS‐T SA (18 months, 24 months) |

176 (21 HR‐ASD, 74 HR‐C, 32 HR‐TD, 49 LR‐TD) |

HR‐ASD, HR‐C, HR‐TD, LR‐TD | 81% Males (HR‐ASD), 70.3% Males (HR‐C), 50.0% Males (HR‐TD), 40.8% Males (LR‐TD) | a Age by group/timepoint |

bMSEL VDQ cMSEL NVDQ |

‐ | Yes (HR‐C, HR‐TD, LR‐TD) | ns (controlling for sex) |

| Dynamic, social (dyadic bid condition, 9 months) | ADOS‐T SA (18 months, 24 months) | Negative correlation (controlling for sex) | ||||||||||

| Dynamic, social (tickle condition, 9 months) | ADOS‐T SA (18 months, 24 months) | ns (controlling for sex) | ||||||||||

| Dynamic, social (dyadic bid condition, 12 months) | ADOS‐T SA (18 months) | Negative correlation (controlling for sex) | ||||||||||

| ADOS‐T SA (24 months) | ns (controlling for sex) | |||||||||||

| Dynamic, social (tickle condition, 12 months) | ADOS‐T SA (18 months, 24 months) | Negative correlation (controlling for sex) | ||||||||||

| Murias et al. (2018) | Looking time | Dynamic, social (dyadic bid) | Face | BASC‐2 (Social Skills); PDD‐BI (Expressive/Receptive Social Communication) | 23 | ASD | 19 Males, 4 Females | 53.6 months (13.5 months) | NVIQ: 64.7 (25.2) | ‐ | No | ns (controlling for age and NVIQ, otherwise positive predictive relationship) |

| PDD‐BI (Autism Composite); ADOS‐2 (Severity) |

ns (controlling/not controlling for age, NVIQ) |

|||||||||||

| Nadig et al. (2010) | Looking time | Dynamic, social (generic) | Face | ADOS (Total score, corrected for item B1) | 12 | HFA | 10 Males, 2 Females | 11 years, 4 months | ‐ | ‐ | No | Negative correlation |

| Dynamic, social (interest) | ns | |||||||||||

| Parish‐Morris et al. (2013) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Face | Face processing accuracy (composite of Let's Face It! Matching Identity Across Expression and Matchmaker Expression subtests) | 60 ASD, 50 NT | ASD, NT |

ASD 53 Males, 7 Females NT 38 Males, 12 Females |

ASD 11.28 years (2.89 years) NT 11.34 years (3.04 years) |

ASD GCA: 111.63 (14.61) NT GCA: 113.70 (14.58) |

ASD Verbal: 110.12 (16.61), Nonverbal: 111.07 (15.48) NT Verbal: 116.42 (16.70), Nonverbal: 108.26 (13.71) |

Yes (NT) |

Positive predictive relationship (gaze > face processing skill) (controlling for age) |

|

SCQ |

ns |

|||||||||||

| Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019) | Looking time | Dynamic, social | Face (collapsed across episodes) |

ADI‐R (RSI), ADOS (overall CSS, Social Affect) |

37 MV‐ASD; 34 V‐ASD | ASD |

MV‐ASD 29 Males, 8 Females V‐ASD 26 Males, 8 Females |

MV‐ASD 13.56 years (3.5 years); V‐ASD 14.97 years (3.4 years) |

Nonverbal Reasoning MV‐ASD Leiter‐3: 62.14 (14.7) V‐ASD WASI‐PR: 104.15 (23.2) |

EL MV‐ASD 20.61 (10.8) V‐ASD 109.24 (81.3) RL MV‐ASD 26.88 (14.5) V‐ASD 102.58 (71.6) |

No |

ns (controlling for NVIQ) |

| Face (expected gaze) |

ADI‐R (RSI) |

Negative correlation (controlling for NVIQ) |

||||||||||

| ADOS (overall CSS, Social Affect CSS) |

ns (controlling for NVIQ) |

|||||||||||

| Face (unexpected gaze) | ADI‐R (RSI), ADOS (overall CSS, Social Affect CSS) |

ns (controlling for NVIQ) |

||||||||||

| Riby and Hancock (2009a) | Fixation duration |

Static, social (cartoons); dynamic, social (human actors); dynamic, social (cartoons) |

Face | CARS (Total score) | 20 | Autism | 15 Males, 5 Females | 13 years, 4 months (48 months) | RCPM: 13 (4) | ‐ | No | Negative correlation |

| Riby and Hancock (2009b) | Fixation duration |

Static, social (embedded picture, scrambled picture) |

Face | CARS (Total score) | 24 | Autism | 18 Males, 6 Females | 12 years, 4 months | RCPM: 12 | ‐ | No | Negative correlation |

| Rigby et al. (2016) | Fixation duration |

Static/dynamic, social (single, multiple characters) |

Faces | AQ | 16 ASD, 16 NT | ASD, NT |

ASD 11 Males, 5 Females NT 11 Males, 5 Females |

ASD 27.8 years (7.8 years) NT 27.3 years (7.5 years) |

ASD FSIQ: 106.3 (10.8), VIQ: 107.8 (13.9), PIQ: 103.9 (15.7) NT FSIQ: 113.4 (8.7), VIQ: 110.7 (9.5), PIQ: 113.3 (11.4) |

‐ | Yes (NT) | Negative correlation |

| Fixation duration, no. fixations (per trial) | Static/dynamic, social (multiple characters) | Individual faces | ||||||||||

| Sasson et al. (2007) | Looking time |

Static, social (face present) |

Face | Social scenes task (emotion recognition) | 10 | Autism | 10 Males |

23.0 years (5.27 years) |

IQ: 107.8 (17.15) | ‐ | No | Negative correlation |

| Static, social (face absent) | ns | |||||||||||

| Sasson et al. (2016) | Fixation duration |

Static, social (congruent, incongruent, scene) |

Face | ECT | 21 | ASD | 18 Males, 3 Females |

23.43 years (4.36 years) |

101.48 (16.97) | ‐ | No | ns |

| Shic et al. (2011) | Looking time | Dynamic, social | Heads | ADOS‐G (Social Affect) | 28 | ASD (20 autistic disorder, 8 PDD‐NOS) | 22 Males, 6 Females | 20.7 months (3.0 months) |

VDQ: 59.7 (28.5); NVDQ: 89.9 (17.3); VMA: 12.1 months (5.9 months); NVMA: 18.4 months (4.1 months). |

‐ | No | Negative correlation |

| Shic et al. (2020) | Looking time | Dynamic, social |

△%Face (%Face DG+SP+ minus %Face DG‐SP‐) |

ADOS‐2 (Total algorithm/CSS score, concurrent/prospective measures) | 50 ASD, 47 NT | ASD, NT |

ASD 88% Males NT 51% Males |

ASD 22.6 months (3.1 months) NT 22.1 months (3.2 months) |

ASD VDQ: 51.7 (21.5), NVDQ: 82.8 (15.8) NT VDQ: 117.2 (17.1), NVDQ: 113.0 (14.8) |

‐ | Yes (NT) |

Negative correlation (controlling/not controlling for VDQ/NVDQ) |

| Snow et al. (2011) | No. fixations | Static, social | Face |

Face recognition accuracy (face‐fan task) |

22 | ASD | 21 Males, 1 Female |

15.96 years (2.44 years) |

FSIQ: 111.50 (17.57) | ‐ | No | Positive correlation |

| Sumner et al. (2018) | Fixation duration | Static, social (combined individual and social conditions) | Face | SCQ | 28 ASD, 25 NT, 28 DCD | ASD, DCD, NT |

ASD 24 Males, 4 Females NT 22 Males, 3 Females DCD 21 Males, 7 Females |

ASD 8.58 years (1.18 years) NT 9.10 years (1.07 years) DCD 8.53 years (1.16 years) |

FSIQ: ASD 101.32 (14.32) NT 110.64 (10.07) DCD 95.93 (12.47) |

‐ | Yes (DCD, NT) | Negative correlation (combined ASD, NT, DCD), ns (separate groups) |

| First fixation latency, gaze following | Static, social | nr | ns | |||||||||

| Swanson and Siller (2013) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Face (congruent vs. incongruent) | SRS (Social Awareness) | 21 ASD, 24 NT | ASD, NT |

ASD 18 Males, 3 Females NT 20 Males, 4 Females |

ASD 87.24 months (18.39 months) NT 81.67 months (19.21 months) |

ASD NVMA: 84.67 months (20.28 months), NVDQ: 98.78 (19.08) NT NVMA: 87.29 months (25.15 months), NVDQ: 107.75 (22.18) |

ASD RL standard (PPVT‐4): 97.81 (21.58); EL standard (EOWPVT‐4): 98.43 (18.76) NT RL standard (PPVT‐4): 103.63 (9.15); EL standard (EOWPVT‐4): 99.63 (10.72) |

Yes (NT) | Significant SRS (social awareness) x condition interaction (controlling for EL). Differences in gaze allocation between conditions when SRS < 70.25. |

| Vivanti et al. (2014) | Fixation proportion | Dynamic, social | Face | ADOS (Social Communication), SCQ | 24 | ASD | 21 Males, 3 Females | 46.54 months (10.55 months) | MSEL composite age equivalent score: 30.39 (12.15) |

MSEL RL age equivalent: 26.75 (14.78) MSEL EL age equivalent: 29.75 (35.22) |

No | ns |

| White et al. (2015) | Fixation duration | Static, social | Face (happy, disgust, angry) | SRS (Total, parent‐rated) | 15 | ASD | 8 Males, 7 Females |

14.88 years (1.552 years) |

‐ | ‐ | No | ns |

| Wilson et al. (2012) | Dynamic scanning index | Static, social | Face regions (left/right eye, nose, mouth) | Face recognition | 11 | ASD | 7 Males, 4 Females | 10.21 years (2.00 years) | WASI matrices: 45.72 (11.60) | TROG‐2: 82.55 (20.09) | No |

Positive correlation (controlling for nonverbal IQ, receptive grammar, and social communication, average percentage of time viewing face) |

| Xavier et al. (2015) | Fixation duration | Static, social | Face | Emotion recognition (combined and individual visual unimodal/bimodal) | 19 | ASD | 14 Males, 5 Females | 9.95 years (1.75 years) |

IQ: 78.5 (21.02) Mental age: 7.74 years (2.51 years) |

‐ | Yes (NT) | ns |

| No. saccades | ||||||||||||

| Zantinge et al. (2017) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social (anger clip) | Face | ADI‐R (Social), ADOS (Severity score) | 28 | ASD | 26 Males, 2 Females | 57.96 months (10.06 months) | FSIQ: 83.71 (22.32) | ‐ | No | Negative predictive relationship |

Abbreviations: ABC, Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ABI, Autism Behavior Inventory; ADI‐R, Autism Diagnostic Inventory, Revised; ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; ADOS‐2, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition; ADOS‐G, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Generic; ADOS‐T, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, toddler module; AQ, Autism Spectrum Quotient; ASC, autism spectrum conditions; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AUT, autistic; BASC‐2, Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition; BPVS‐2, British Picture Vocabulary Scale, Second Edition; CA, chronological age; CARS, Childhood Autism Rating Scale; CFMT, Cambridge Face Memory Test; CSI, communication and social interaction; CSS, calibrated severity score; DCD, developmental coordination disorder; DG+SP+, direct gaze and speech; DG+SP+, no direct gaze and no speech; ECT, emotions in context task; EL, expressive language; EOWPVT‐4, Expressive One‐Word Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition; ER‐40, Penn Emotion Recognition Task; FSIQ, full scale intelligence quotient; GCA, general conceptual ability; HFA, high functioning autism; HR‐ASD, high risk autism spectrum disorder; HR‐C, high risk complex; HR‐TD, high risk typically developing; IQ, intelligence quotient; KBIT‐2, Kaufmann Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition; L/SW, lethargy/social withdrawal; LR‐TD, low risk typically developing; MET, Multifaceted Empathy Test; MSEL, Mullen Scales of Early Learning; MV‐ASD, minimally verbal children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder; nr, not reported; ns, not significant; NT, neurotypical; NVA, nonverbal age; NVDQ, nonverbal developmental quotient; NVIQ, nonverbal intelligence quotient; NVMA, nonverbal mental age; PDD‐BI, Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Behavior Inventory; PDD‐NOS, pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified; PIQ, performance intelligence quotient; PPVT‐4, Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition; RCPM, Raven's Colored Progressive Matrices; RL, receptive language; RMET, Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test; RPM, Raven's Progressive Matrices; RSI, reciprocal social interaction; SCIT‐A, Social Cognition and Interaction Training for Autism; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; SLI, specific language impairment; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; SRS‐2, Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition; SSIS‐p, Social Skills Improvement System, parent report; TASIT, The Awareness of Social Inference Test; TAU, treatment as usual; ToM, theory of mind; TROG‐2, Test for Reception of Grammar, Second Edition; VA, verbal age; V‐ASD, verbally fluent children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder; VDQ, verbal developmental quotient; VIQ, verbal intelligence quotient; VMA, verbal mental age; VPC, Visual Paired Comparison paradigm; WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; WASI‐PR, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, perceptual reasoning scale; W‐IQ, Wortschatztest Intelligence Quotient.

6 months: HR‐ASD: 6.4 months (0.6 months); HR‐C: 6.5 months (1.0 months); HR‐TD: 6.4 months (0.6 months); LR‐TD: 6.2 months (0.3 months); 12 months: HR‐ASD: 12.5 months (0.5 months); HR‐C: 12.4 months (0.7 months); HR‐TD: 12.5 months (0.6 months); LR‐TD: 12.3 months (0.6 months); 18 months: HR‐ASD: 18.2 months (0.5 months); HR‐C: 18.5 months (0.8 months); HR‐TD: 18.4 months (0.8 months); LR‐TD: 18.6 months (0.9 months); 24 months: HR‐ASD: 24.5 months (1.1 months); HR‐C: 24.8 months (1.3 months); HR‐TD: 24.7 months (1.6 months); LR‐TD: 24.5 months (1.0 months).

6 months: HR‐ASD: 78.7 (12.2); HR‐C: 77.5 (17.1); HR‐TD: 79.1 (13.2); LR‐TD: 84.3 (13.2); 12 months: HR‐ASD: 75.0 (20.3); HR‐C: 82.3 (16.9); HR‐TD: 96.7 (16.5); LR‐TD: 95.6 (19.1); 18 months: HR‐ASD: 78.8 (30.4); HR‐C: 85.6 (23.6); HR‐TD: 114.2 (19.4); LR‐TD: 115.5 (18.3); 24 months: HR‐ASD: 92.6 (25.7); HR‐C: 103.6 (20.9); HR‐TD: 120.2 (16.5); LR‐TD: 127.1 (18.6).

6 months: HR‐ASD: 94.1 (13.7); HR‐C: 93.1 (23.8); HR‐TD97.9 (23.8); LR‐TD: 97.8 (16.5); 12 months: HR‐ASD: 103.3 (12.0); HR‐C: 112.9 (13.7); HR‐TD: 113.4 (12.0); LR‐TD: 118.9 (11.7); 18 months: HR‐ASD: 97.2 (11.2); HR‐C: 100.9 (10.9); HR‐TD: 109.3 (10.7); LR‐TD: 110.8 (11.7); 24 months: HR‐ASD: 94.7 (17.2); HR‐C: 103.1 (13.4); HR‐TD: 113.8 (14.1); LR‐TD: 116.6 (13.2).

Three studies used joint attention paradigms exploring congruent/expected (where a model's gaze is directed toward a target) and incongruent/unexpected (where a model's gaze is directed away from a target) gaze. Across a combined sample of participants with ASD and neurotypical controls, Swanson and Siller (2013) found a significant moderating effect of social functioning ability. Specifically, differences in fixation duration toward the face between congruent and incongruent conditions were only evident in participants with high levels of social awareness (using the Social Awareness subscale of the SRS). In participants with ASD, Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019) found that reduced looking time to the face was associated with higher scores on the Autism Diagnostic Interview‐Revised (ADI‐R) Reciprocal Social Interaction subscale during the expected gaze shift condition, with no relationship identified for the unexpected gaze shift condition. No significant relationships with the ADOS Overall and Social Affect calibrated severity scores were identified. In participants with ASD, Kaliukhovich et al. (2020) demonstrated that increased looking time to the heads of actors was associated with increased social functioning (ADOS‐2 Social Affect) and reduced autism symptom severity (ADOS‐2 Total) only when actors were gazing at each other, but not when actors' gaze was focused on a shared activity. However, no associations were identified for social domains of the Autism Behavior Inventory or Aberrant Behavior Checklist, and the authors urged caution in interpretation of the results given the number of multiple comparisons performed.

Further evidence linking difficulties prioritizing attention to socially pertinent information with ToM was demonstrated by Hanley et al. (2014). Across participants with ASD, specific language impairment and neurotypical controls, there was an association between longer anticipatory gaze (defined as the delay in gaze toward a social actor to determine their awareness of an unexpected event occurring) and reduced ToM performance (a composite of four false‐belief tasks).

There is also evidence to suggest that gaze allocation to the face in ASD is associated with autism symptom severity in tasks requiring higher levels of social exchange. Nadig et al. (2010) examined gaze duration to the face of the researcher while they engaged in a brief face‐to‐face conversation with participants with ASD relating to either a pre‐identified specific circumscribed interest or a more generic topic (e.g., pets). A significant negative relationship between ADOS Total score (excluding item B1 “unusual eye contact”) and fixations on the face was identified during conversation about the generic topic, although a trend level negative relationship was identified for the circumscribed interest topic.

Overall, there is an indication that the relationship between gaze toward the face and social functioning/autism symptom severity is dependent on the social context relating to the face. Research remains limited and future directions might include further investigation to determine how allocation of gaze toward the face is used to support social functioning.

Eyes

A total of 32 studies investigated gaze directed toward the eyes, with 15 of these identifying significant positive associations between gaze allocation to the eyes and social functioning and inverse associations with autism symptom severity (refer to Table 5). Contrastingly, one study, Chawarska and Shic (2009) found that increased gaze allocation to the eyes was associated with poorer face recognition performance (on the Visual Paired Comparison paradigm; Fantz, 1964) in participants with ASD, reflective of limited scanning of internal facial features.

TABLE 5.

Summary of findings—Eyes (N = 32)

| Reference | Visual processing index | Visual stimuli | Interest area | Social function/autism trait measure | Participant characteristics | Other clinical groups in analysis? | Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Diagnosis | Sex | Age M(SD) | IQ/DQ/mental age | Language | |||||||

| Amestoy et al. (2015) | Fixation time (total) | Static, social | Eyes | ADI‐R (RSI) |

Adults: 13 Children: 14 |

ASD |

Adults: 12 Males, 1 Female Children: 11 Males, 3 Females |

Adults: 23.8 years (3.6 years) Children: 11.3 years (2.1 years) |

Adults: VIQ: 107.2 (18); NVIQ: 102.1 (15) Children: VIQ: 94.5 (17); NVIQ: 89.8 (11) |

‐ | No | Negative correlation |

| Asberg‐Johnels et al. (2017) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social (neutral, fearful, happy, angry) | Eyes | AQ |

ASD Adults: 27 Adolescents: 30 NT Adults: 27 Adolescents: 31 |

ASD Adults: 9 AD, 17 AS, 1 PDD‐NOS Adolescents: 17 AD, 12 AS, 1 PDD‐NOS NT Adults: 27, Adolescents: 27 |

‐ |

ASD Adults: 29.0 years (8.0 years) Adolescents: 15.0 years (2.2 years) NT Adults: 27.0 years (6.4 years) Adolescents: 14.8 years (2.2 years) |

ASD Adults: PIQ: 109.2 (16.5) Adolescents: PIQ: 102.3 (15.8) NT Adults: PIQ: 112.9 (8.6) Adolescents: PIQ: 113.6 (14.8) |

‐ | Yes (NT) |

ns (ASD‐Adult and ASD‐Adolescent separately, full sample, collapsed across diagnosis and age) |

| Avni et al. (2020) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Eyes |

ADOS‐2 (Total score) |

71 | ASD | 59 Males, 12 Females | 5.1 years (1.8 years) | ‐ | ‐ | No | ns |

| Chawarska and Shic (2009) | Looking time (familiar, novel preference), fixation duration (novelty preference ratio) | Static, social | Eyes | VPC (familiar preference) | 14 Age Group 1, 30 Age Group 2 | 27 autism, 17 PDD‐NOS | 84% Males |

Age Group 1 26.9 months (6.2 months) Age Group 2 46.4 months (6.4 months) |

Age Group 1 VDQ: 61 (37), NVDQ: 85 (24) Age Group 2 VDQ: 66 (36), NVDQ: 76 (25) |

‐ | No |

Positive correlation (controlling for CA, VDQ, NVDQ) |

| VPC (novelty preference, novelty preference ratio) |

ns (controlling for CA, VDQ, NVDQ) |

|||||||||||

| Corden et al. (2008) | Percentage total fixations | Static, social | Eyes |

Ekman‐Friesen test of facial affect recognition (fear recognition) |

18 | AS | 13 Males, 5 Females | 32.9 years (13.35 years) | VIQ: 116.3 (9.14), NVIQ: 117.1 (14.56), FSIQ: 119.9 (11.10) | ‐ | No |

Positive correlation Positive prediction |

| Ekman‐Friesen test of facial affect recognition (happy, sad, angry, surprised, disgusted recognition), ADOS, AQ. | ns | |||||||||||

| Eyes (sad, fear, angry, surprised, disgusted) | Ekman‐Friesen test of facial affect recognition (fear recognition) | Positive prediction | ||||||||||

| Eyes (happy) | ns | |||||||||||

| Crawford et al. (2015) | Looking time, fixation latency | Static, social (neutral faces) | Eyes | SCQ | 15 ASD, 13 FXS | ASD (8 autistic disorder, 2 asperger syndrome, 5 PDD‐NOS), FXS |

ASD 80% Males FXS 92.31% Males |

ASD 11.00 years (3.48 years) FXS 19.70 years (9.00 years) |

‐ | ‐ | Yes (FXS) | ns |

|

Crehan and Althoff (2021) |

Dwell time, fixation count, second fixation duration |

Dynamic, static (stable vs. dynamic) | Eyes |

SRS‐A, ToMI‐2‐SR (early, basic, advanced, total) |

15 ASD, 21 NT | ASD, NT |

ASD 33% Females NT 48% Females |

ASD 21.20 years (3.10 years) NT 20.05 years (1.16 years) |

ASD IQ: 117.00 (11.73) NT IQ: 109.71 (14.05) |

‐ | Yes (NT) | ns |

| Dynamic, static (more eye contact vs. less eye contact) | SRS‐A | Negative correlation, ns (regression model, controlling for age, sex and IQ) | ||||||||||

| Dwell time, fixation count | Dynamic, static (more eye contact vs. less eye contact) | ToMI‐2‐SR (early, advanced, total) | Positive correlation, positive prediction (advanced only), ns (regression model—total scale only). Regressions controlling for age, sex, and IQ. | |||||||||

| ToMI‐2‐SR (basic) | ns | |||||||||||

| Second fixation duration | Dynamic, static (more eye contact vs. less eye contact) | ToMI‐2‐SR (advanced) | Positive correlation, ns (regression model, controlling for age, sex, and IQ). | |||||||||

| ToMI‐2‐SR (basic, early, total) | ns | |||||||||||

| Crehan et al. (2020) | Dwell time |

Dynamic, social (catching another staring) |

Eyes | ToMI‐2‐SR (advanced) | 15 ASD, 17 NT | ASD, NT |

ASD 67% Males NT 52% Males |

ASD 21.20 years (3.10 years) NT 20.05 years (1.16 years) |

ASD IQ: 117.00 (11.73) NT IQ: 109.71 (14.05) |

‐ | Yes (NT) | Positive correlation |

| Dynamic, social (getting caught staring); static, social (mutual) | ToMI‐2‐SR (advanced) | Positive correlation | ||||||||||

| ToMI‐2‐SR (early, basic) | ns | |||||||||||

| Static, social (averted) | ToMI‐2‐SR (advanced) | ns | ||||||||||

| Fixation duration (second fixation) | Dynamic, social (getting caught staring) | ToMI‐2‐SR (advanced) | Positive correlation | |||||||||

| Static, social (mutual) | Negative correlation | |||||||||||

| Dynamic, social (catching another staring); static, social (averted) | ToMI‐2‐SR (early, basic, advanced) |

ns |

||||||||||

| Cuve et al. (2021) | Fixation duration, fixation count | Dynamic, social | Eyes | AQ28, emotion recognition | 25 ASD, 45 NT | ASD, NT |

ASD 13 Males, 11 Females NT 16 Males, 29 Females |

ASD 37.68 years (11.86 years) NT 26.13 years (6.66 years) |

ASD IQ: 121.68 (16.49) NT IQ: 117.76 (13.52) |

‐ | nr | ns |

| Del Valle Rubido et al. (2018) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social (complex movies), static, social (gender discrimination) | Eyes | ADOS (Total, RSI, CSI); ABC (L/SW) | 38 | ASD | 38 Males | 24.2 years (5.8 years) |

FSIQ: 101.1 (14.3), VIQ: 100.5 (16.1), PIQ: 100.6 (12.7) |

‐ | No | ns |

| Fedor et al. (2018) | Fixation duration, fixation count | Static, social (immediate recognition, delayed recognition) | Eyes | ADOS CSS, CFMT | 24 children, 23 adolescents, 19 adults | Autism |

Children: 21 Males, 3 Females Adolescents: 19 Males, 4 Females Adults: 18 Males, 1 Female |

Children: 11.2 years (1.7 years), Adolescents: 15.3 years (1.5 years), Adults: 24.2 years (4.9 years) |

Children VIQ: 108.7 (13.0), PIQ: 114.4 (13.3), FSIQ: 112.8 (12.9) Adolescents VIQ: 106.3 (13.2), PIQ: 107.1 (13.1), FSIQ: 107.7 (13.3) Adults VIQ: 109.8 (13.0), PIQ: 110.3 (15.9), FSIQ: 111.3 (14.6) |

‐ | No |

ns (controlling for FSIQ, age) |

| Fujioka et al. (2016) | Fixation duration |

Dynamic, social (human face, blinking) Static, social (still human face); dynamic, social (human face, mouth moving; human face, silent; human face, talking) |

Eyes | SRS | 21 | ASD | 21 Males | 27.6 years (7.7 years) |

FSIQ: 99.8 (13.5) VIQ: 103.3 (13.3) PIQ: 96.4 (16.0) Note, N = 20 |

‐ | No | ns |

| Fujioka et al. (2020) | Fixation duration | Dynamic/social (face with mouth motion, face without mouth motion) | Eyes | SRS‐2 |

ASD 0–5 years 19 6–11 years 34 12–18 years 30 NT 0–5 years 120 6–11 years 150 12–18 years 37 |

ASD, NT |

ASD 0–5 years 14 Males, 5 Females 6–11 years 28 Males, 6 Females 12–18 years 22 Males, 8 Females NT 0–5 years 58 Males, 62 Females 6–11 years 69 Males, 81 Females 12–18 years 14 Males, 23 Females |

ASD 0–5 years 4.7 years (0.9 years) 6–11 years 9.2 years (1.6 years) 12–18 years 14.5 years (1.6 years) NT 0–5 years 4.6 years (1.0 years) 6–11 years 8.7 years (1.7 years) 12–18 years 14.2 years (1.5 years) |

ASD IQ/DQ > 70 |

‐ | Yes (NT) |

ns (whole group and ASD only, controlling for age, sex) |

| Gillespie‐Smith, Doherty‐Sneddon, et al. (2014) | Fixation duration | Static, social (familiar face) | Eyes | CARS, SCQ | 21 | ASD | 20 Males, 1 Female | 13 years, 7 months (30 months) |

BPVS‐II VA: 74 (27) RCPM NVA: 27 (7) |

‐ | No | ns |

| Static, social (unfamiliar face) | Eyes | CARS | ns | |||||||||

| SCQ | Negative correlation, HSF = LSF | |||||||||||

| Static, social (self‐face) | Eyes |

CARS |

ns | |||||||||

| SCQ | Negative correlation, HSF > LSF | |||||||||||

| First fixation latency | Static, social (familiar, unfamiliar, self‐face) | Eyes | CARS, SCQ | ns | ||||||||

| Hanley et al. (2014) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Eyes | ToM composite |

17 ASD, 14 SLI, 16 NT |

ASD, SLI, NT |

ASD 11 Males, 6 Females SLI 12 Males, 2 Females NT 6 Males, 10 Females |

ASD 121 months (25 months) SLI 115.2 months (10 months) NT 119.6 months (8 months) |

ASD VA: 84.5 (12.1) NVA: 92.9 (13.764) SLI VA: 84.4 (5.8) NVA: 93.79 (6.852) NT VA: 94.06 (8.621) NVA: 95.56 (7.174) |

‐ | Yes (SLI, NT) |

Positive correlation (controlling for age, verbal ability) |

| Hanley et al. (2015) | Percentage fixations | Dynamic, social | Eyes | SRS (Social Awareness domain) | 11 | ASD | 7 Males, 4 Females | 26 years (8.1 years) | VIQ: 120 (14); PIQ: 111 (9) | ‐ | No | Negative correlation |

| SRS (Total score, Social Cognition domain, Social Communication domain, Social Motivation domain, Autistic Mannerisms domain) | ns | |||||||||||

| Jones et al. (2008) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Eyes | ADOS (Social Algorithm total score) | 15 | ASD | 11 Males, 4 Females | 2.28 years (0.58 years) | VF AE (MSEL R/E): 1.17 years (0.66 years); NVF (MSEL VR): 1.77 years (0.47 years). |

‐ |

No | Negative correlation |

| Jones and Klin (2013) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Eyes | ADOS (Social Affect)—24 months | 11 | ASD | 11 Males |

2–24 months |

Mullen NV AE: 23.36 (6.20) |

Mullen RL AE: 22.45 (7.59), Mullen ELV AE: 22.18 (7.56) |

No | Negative correlation |

| 2–6 months, 2–9 months |

ns |

|||||||||||

| 2–12 months, 2–15 months, 2–18 months | Negative correlation | |||||||||||

| Jones et al. (2017) | Eye contact duration | Dynamic, social (conversation) | Eyes | ADOS (CSS Social Affect); SRS‐2 (total T score) |

ASD (Sample 1) 20 ASD (Sample 2) 20 |

ASD |

ASD (Sample 1) 16 Males, 4 Females ASD (Sample 2) 12 Males, 3 Females |

ASD (Sample 1) 7.0 years (2.1 years) ASD (Sample 2) 8 years (2.8 years) |

ASD (Sample 1) VIQ: 105.55 (18), NVIQ: 109.75 (25). ASD (Sample 2) VIQ: 95.07 (26), NVIQ: 99.40 (29). |

‐ | Yes (NT, SRS only) | Negative correlation |

| Dynamic, social (interactive play) | ADOS (CSS Social Affect); SRS‐2 (total T score) | ns | ||||||||||

| Eye contact frequency | Dynamic, social (conversation, interactive play) |

ADOS (CSS Social Affect) |

||||||||||

| Kirchner et al. (2011) | Fixation duration | Static, social (MET: emotion recognition and face identity average) | Eyes |

RMET |

20 | ASC | 15 Males, 5 Females | 31.9 years (7.6 years) | W‐IQ: 112.6 (11.6) | ‐ | No | Positive correlation |

| ADI‐R (Social score), CFMT |

ns |

|||||||||||

| Klin et al. (2002) | Fixation duration |

Dynamic, social |

Eyes |

ADOS (Social Algorithm) |

15 | Autism | 15 Males | 15.4 years (7.3 years) | VIQ: 101.3 (24.9) | ‐ | No | ns |

| McPartland et al. (2011) | Fixations (proportion) | Static, social (upright face stimuli) | Eyes |

Mind in the Eyes: Gender task |

15 | ASD | 13 Males, 2 Females | 14.5 years (1.7 years) | PIQ: 115.1 (11.8) | ‐ | No | ns |

| Muller et al. (2016) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Eyes | MASC |

33 ASD, 23 NT |

ASD, NT |

ASD 27 Males, 6 Females NT 14 Males, 9 Females |

ASD 15.6 years (1.9 years) NT 16.3 years (2.4 years) |

ASD GAI: 101.1 (14.4) NT GAI: 109.8 (15.1) |

‐ | Yes (NT) | Positive prediction |

| Murias et al. (2018) | Looking time | Dynamic, social (dyadic bid) | Eyes | BASC‐2 (Social Skills); PDD‐BI (Expressive/Receptive Social Communication), PDD‐BI (Autism Composite); ADOS‐2 (Severity) | 23 | ASD | 19 Males, 4 Females | 53.6 months (13.5 months) | NVIQ: 64.7 (25.2) | ‐ | No | ns |

| Norbury et al. (2009) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Eyes | ADOS (Social) | 14 ALI, 14 ALN | ASD | 27 Males, 1 Females |

ALI 14.9 years (1.2 years) ALN 14.9 years (1.4 years) |

ALI Verbal: 81.9 (22.8) Nonverbal: 96.6 (15.7) ALN Verbal: 101.9 (16.3) Nonverbal: 99.7 (14.3) |

ALI CELF‐III, Sentence Repetition: 4.1 (1.4). ALN CELF‐III Sentence Repetition: 8.8 (1.8). |

No |

ns (ALI/ALN combined, ALI and ALN separately) |

| Plesa‐Skwerer et al. (2019) | Looking time | Dynamic, social | Eyes (collapsed across episodes) | ADI‐R (RSI), ADOS (overall CSS, Social Affect CSS) | 37 MV‐ASD; 34 V‐ASD | ASD |

MV‐ASD 29 Males, 8 Females V‐ASD 26 Males, 8 Females |

MV‐ASD 13.56 years (3.5 years) V‐ASD 14.97 years (3.4 years) |

MV‐ASD Leiter‐3: 62.14 (14.7) V‐ASD WASI‐PR: 104.15 (23.2) |

MV‐ASD RL: 26.88 (14.5), EL: 20.61 (10.8) V‐ASD RL: 102.58 (71.6), EL: 109.24 (81.3) |

No |

ns (controlling for NVIQ) |

| Eyes (unexpected gaze) |

ADOS (overall CSS) |

Negative correlation (controlling for NVIQ) |

||||||||||

| ADI‐R (RSI), ADOS (Social Affect CSS) |

ns (controlling for NVIQ) |

|||||||||||

| Eyes (expected gaze) |

ADI‐R (RSI), ADOS (overall CSS, Social Affect CSS) |

ns (controlling for NVIQ) |

||||||||||

| Rice et al. (2012) | Fixation duration | Dynamic, social | Eyes | ADOS (Severity) |

ASD (Additional) 72 ASD (Matched) 37 |

37.6% Autism, 12.8% Asperger Syndrome, 49.5% PDD‐NOS |

ASD (Additional) 53 Males, 19 Females ASD (Matched) 30 Males,7 Females |

ASD (Additional) 10.2 years (3.5 years) ASD (Matched) 10.0 years (2.3 years) |