Abstract

The objective of this study was to understand the existing practices and attitudes regarding inpatient sleep at the 2020 US News and World Report (USNWR) Honor Roll pediatric (n = 10) and adult (n = 20) hospitals. Section chiefs of Hospital Medicine from these institutions were surveyed and interviewed between June and August 2021. Among 23 of 30 surveyed physician leaders (response rate = 77%), 96% (n = 22) rated patient sleep as important, but only 43% (n = 10) were satisfied with their institutions' efforts. A total of 96% (n = 22) of institutions lack sleep equity practices. Fewer than half (48%) of top hospitals have sleep‐friendly practices, with the most common practices including reducing overnight vital sign monitoring (43%), decreasing ambient light in the wards (43%), adjusting lab and medication schedules (35%), and implementing quiet hours (30%). Major themes from qualitative interviews included: importance of universal sleep‐friendly cultures, environmental changes, and external incentives to improve patient sleep.

INTRODUCTION

Though sleep is an integral part of health and recovery, hospitalized patients do not get quality sleep. 1 , 2 , 3 Reduced sleep contributes to adverse health outcomes, impaired recovery, and comorbidities, such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, delirium, and post‐hospitalization syndrome. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Ensuring patients have equitable sleep is an increasing priority. 8 Reduced sleep perpetuates existing health disparities in marginalized ethnic populations. Sleep health equity has not been studied in the hospital setting previously (e.g., improving sleep for racial/ethnic minorities, patients with pre‐existing risk factors, communication barriers, or limited familiarity with hospital services). 9 , 10 , 11

The American Academy of Nursing recommends that patients not be woken up unless required by their condition. 12 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services distributes a national survey inquiring about “quietness of the hospital environment” to patients through the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey. 13 , 14 As of 2018, implementing inpatient sleep‐promoting programs is the top “to‐do” hospital practice on the Right Care Recommendations list. 15 The National Sleep Foundation advocates for improved equitable access to clinical sleep healthcare and for health equity to be addressed throughout sleep healthcare delivery. 8

Despite current recommendations, there are no previous efforts to describe the practices used to improve inpatient sleep. In this study, hospitalist leaders from the 2020 US News and World Report (USNWR) Honor Roll adult and pediatric hospitals were surveyed and interviewed to better understand existing practices and attitudes regarding inpatient sleep.

METHODS

Study design

From June 2021 to August 2021, a national mixed‐methods study was conducted with the section chiefs of Hospital Medicine at the 2020 USNWR Honor Roll pediatric (n = 10) and adult (n = 20) hospitals. Section chiefs of Hospital Medicine were invited to participate in this study as accessible and knowledgeable leaders at each institution. An anonymous, 20‐item quantitative survey was developed and piloted using an iterative process with a group of high‐value care physicians. Hospitalist leaders were emailed invitations to participate in the quantitative survey. Three follow‐up emails were distributed to encourage study participation. Participants were asked to report any existing sleep‐friendly practices at their institutions. They were asked to answer a 5‐point Likert‐type scale survey (where “1” is most important or satisfied, “5” is least important or satisfied) that inquired about the importance of hospitalized patient sleep, satisfaction with their institutions' efforts to improve patient sleep, their perceived importance of sleep health equity, and whether their institution addressed sleep equity within the hospital. See Supporting Information for additional study details (Supplemental Figure 1), survey questions (Supplemental Figure 2), and interview questionnaire (Supplemental Figure 3).

All participants were invited to structured, qualitative interviews. Applying grounded theory principles, the interview questionnaire was designed using the 4D framework of appreciative inquiry. 16 Interviewed hospitalist leaders were asked to describe current sleep‐friendly institutionalized practices, successes and barriers encountered, methods to track practices, and whether they addressed patient sleep from a health equity perspective. Interviewed hospitalist leaders also suggested how to further improve patient sleep. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board deemed this study as exempt (Protocol #21‐0146).

Data collection

Survey data was securely stored within REDCap. Structured interviews were conducted, audio‐recorded, and transcribed using Zoom.

Data analysis

Stored data was imported into STATA 17.0 for descriptive analysis. Institution satisfaction survey response scores were dichotomized by defining a score of “1” or “2” as “Satisfied” and “3,” “4,” or “5” as “Not Satisfied.”

Qualitative interview data was imported into Atlas.ti for thematic analysis. Zoom‐generated transcripts were corrected for accuracy by authors M. A., J. G., and N. M. O. Interview recordings and edited transcripts were overlaid and time‐stamped for each interview question. Codes were assigned to discrete transcript quotes that represented participants' ideas. Transcript quotes that represented multiple ideas were assigned codes that corresponded to each idea. All codes were cross‐referenced by M. A., J. G., N. M. O., and A. K. for internal validity. Coding trends between interviews were reviewed by these researchers to identify themes.

RESULTS

Demographics

The total survey response rate was 77% (n = 23). Survey participants were section chiefs of hospital medicine at both pediatric (n = 8, 35%) and adult (n = 15, 65%) hospitals. The majority (n = 18, 78%) of participating institutions were self‐described private, nonprofit hospitals. Most (n = 21, 91%) were based in urban settings and 70% (n = 16) served primarily Caucasian patient populations. Sixty‐five percent (n = 15) of institutions primarily serve patients that use Medicare and/or Medicaid as their primary insurance. Survey responses did not differ based on these demographics.

Survey

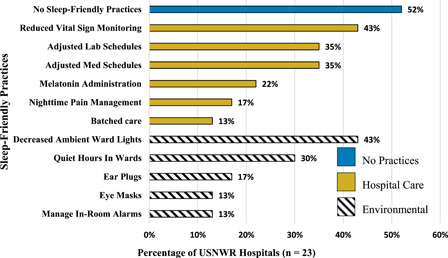

Though 96% (n = 22) of hospitalist leaders at top hospitals rated patient sleep as important, fewer than half (43%, n = 10) were satisfied with their institution's efforts to improve patient sleep. Furthermore, 91% (n = 21) of hospitalist leaders rated sleep equity as important, but only one institution (4%) addressed this disparity. This institution's approach to addressing sleep health equity was not shared. Fifty‐two percent of surveyed institutions (n = 12) report having no sleep‐friendly practices in place. Among the 11 institutions that do, the most common practices included reducing overnight vital sign monitoring (n = 10, 43%), decreasing ambient ward lights (n = 10, 43%), adjusting lab and medication schedules (n = 8, 35%), and implementing quiet hours (n = 7, 30%) (Figure 1). Results were similar between adult and pediatric hospitals, except no pediatric hospitals reported using quiet hours.

Figure 1.

Reported sleep‐friendly hospital practices at USNWR Honor Roll hospitals, n = 23. Eleven of the surveyed institutions reported active practices to improve sleep; 12 reported none. The figure reflects existing practices that are grouped by their type (Hospital Care or Environmental). The one “Other” practice reported was to rubberize floors to minimize noise. Miscellaneous practices that are not associated with typical hospital operations but may be used to improve patient sleep were also surveyed (see Supplementary Material). However, those practices were rarely reported by hospitals and were excluded from this figure.

Interview

Of the surveyed section chiefs, three pediatric and five adult hospitalist leaders also participated in structured interviews (n = 8/30, 27%). Thematic saturation was achieved after analyzing these interviews. The themes synthesized from the interviews are presented in Table 1, which also displays subthemes and associated representative quotes. Participants highlighted buy‐in from hospital staff as a key contributor to successfully improving patient sleep (e.g., providers reduce room entries through batched care, or enforce quiet hours among peers). External initiatives were also important for patient sleep (e.g., patient care initiatives, funded innovation projects). Barriers to success were related to the hospital environment and culture (e.g.,inflexible workflow, time conflicts, noisy alarms) and fixed standards of care, where clinicians often provide the same care to low‐risk and high‐risk patients. 17 , 18 Suggestions for improvement included developing sleep‐friendly practice standards and changing hospital practices (e.g., grouping tasks, decreasing interventions when appropriate) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Qualitative descriptions of existing and potential sleep‐friendly practices, n = 8

| Theme | Subtheme | Representative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Universal culture/shared understanding | Defaulting to more interventions | “I think the culture is often one such that people just do the same [disruptive practices] they would do for the sicker patient for the less sick patient because they're worried, what if that patient gets sick too.” |

| Success defined as a culture change | “I count that as a successful program because it has been long‐standing and I believe it has helped to shift the culture somewhat.” | |

| Ensure all patients have equal access to improved sleep conditions | “[…] one of the biggest sources of inequity in our healthcare delivery is that some patients are knowledgeable enough to […] ask for things, whereas other patients may not know that they have available earplugs [or] melatonin , because nobody has told them in a way that they understand it […] make sure that messaging is done in a consistent fashion to everybody in a language they understand, and that they're not made to feel like they're being needy for asking for these things.” | |

| Need for education, evidence, and implementation efforts to improve | “So that would require a lot of education and buy‐in. I would want to have data at our organization about how disrupted sleep is for our patients and then also data about the importance of sleep, especially for kids and hospitalized kids […] and then working on putting into practice ways to improve […] it would probably be a pretty lofty quality improvement effort at that point.” | |

| Environmental changes | Universal sound and light timing | “[…] some standard time across most floors where lights would be dim in certain common areas, noise would be reduced […] to let everyone know it's night. That's probably the one I would focus on first.” |

| Medical device noise | “We have incredibly noisy IV pumps that often start beeping in the patient's room. | |

| I am sure that somebody has invented an IV pump somewhere that beeps outside the patient's room so that people can go in quietly but we don't have them.” | ||

| Alternatives to sounded alarms in rooms | "Telemetry alarms, accelerometer alarms, and bell alarms. Are there ways to alert a clinical staff of an event without necessarily just being sound?" | |

| Hospital practices | Grouping tasks/establish standardized and customized practices | “[…] things like grouping tasks for individual patients like vitals, medications, or any other required assessments in the middle of the night. I would do more to make that uniform across the hospital, realizing that there would need to be customization [across units] .” |

| Obstacles with early morning lab draws | “I think the bigger obstacles are just general patient flow and workflow. The biggest thing that I can think of off the top of my head is lab draws at like 4am or 5am that interfere with sleep […] this is the time that we have the most lab technicians, so we'd have to probably change up the lab drawing schedule.” | |

| Select “sleep‐preservation” mode in EMR | “I would say that every routine type of care should be structured […] to have a sleep preservation mode […] the providers should be prompted in a ‘one‐click' kind of fashion to be able to select whether the patient is going to be interrupted for vital signs or interrupted for blood draws if they are sleeping.” | |

| External incentives | Progress through external grant and expert support | “So that's been driving [current efforts]; working with a group of lighting experts and then combining that with the people on the clinical side who really do want patients to sleep better,[….] But that's grant funded. So if it was just internal, I doubt we could have got it going .” |

| External ratings | “one of the biggest factors that drives this is the fact that HCAHPS scores matter […] the patient experience does matter, and I think that concept has gotten traction in recent years and so I think where there are opportunities to just do simple cosmetic things to help the patient experience, I think we've done a pretty good job with it.” |

Note: Section Chiefs of Hospital Medicine at USNWR Honor Roll Hospitals were asked to describe some of the successes and barriers of any patient sleep initiatives at their hospitals. They were also asked to envision the ways that they would improve hospital sleep and name what they would change first.

DISCUSSION

This is the first national study aimed at better understanding the practices used to promote sleep for hospitalized patients. We found a relative lack of institutionalized, standardized efforts to promote patient sleep among nationally recognized hospitals despite the significant adverse effects associated with sleep disruption for hospitalized patients. 12 , 15 The absence of efforts to address sleep in high‐risk patient populations is also concerning, given the concerns of sleep disruption contributing to health disparities in cardiovascular, psychiatric, and age‐related chronic disorders. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11

Similarly, the structured interviews contextualized some reasons for slow progress: (1) the culture is such that providers want to improve patient sleep, but not at the expense of changing standard workflow, and (2) there is a lack of incentives and programs to support changes. Highlighting cases of successfully adjusted hospital practices may encourage improvement among providers, in addition to establishing standards for patient sleep hygiene or creating sleep‐friendly ratings for hospitals.

The USNWR Honor Roll hospitals were our selected sample because they are nationally recognized high achievers in hospital care; however, the study results show that these institutions do not have standardization of sleep‐friendly practices and that national inpatient sleep practices are less standardized than is the case for other healthcare practices (e.g., hand hygiene). Our findings highlight the need for best practice guidelines to support patient sleep during periods of hospitalization. Future work involves understanding the sleep‐friendly practices at CMS Hospital Compare survey's high performers on its “Quiet at night” question and identifying sleep health equity practices during hospitalization.

This study has several limitations. While the study queried USNWR hospitals across the United States, its small sample size may limit its generalizability to all US hospitals. Aside from hospital medicine, no other departments or disciplines (e.g., nursing) at USNWR hospitals were surveyed, so these findings may not capture the range of sleep‐friendly hospital practices present at the participating institutions. Hospitalist leaders who completed the survey and interview may be more interested in the topic and would know more about their sleep hygiene practices. Conversely, surveyed hospitalist leaders may not be aware of nighttime initiatives if they are not present at night. In surveying section chiefs, the data may reflect policies rather than practices. As many hospitals had few to no policies, there may be even fewer sleep‐friendly practices than reported. Since survey and interview responses were not validated, the responses (although anonymous) may be affected by response bias.

CONCLUSION

Developing practices to improve hospitalized patient sleep is a top priority because sleep is fundamental to health and recovery. Hospitalist leaders recognize the importance of improving patient sleep, but few have existing sleep‐friendly institutionalized practices. Most institutions have no sleep health equity practices currently despite widespread agreement among hospital leadership on its importance in the hospital. Clinicians and hospital leaders should promote improved sleep quality for hospitalized patients by building sleep‐friendly hospital cultures, addressing sleep health equity within the hospital, and establishing best practices for patient sleep.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have seen and approved this manuscript. Murtala Affini is a 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine Student Hospitalist Scholar Grantee and received funding to perform this investigation.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Affini MI, Arora VM, Gulati J, et al. Defining existing practices to support the sleep of hospitalized patients: A mixed‐methods study of top‐ranked hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2022;17:633‐638. 10.1002/jhm.12917

REFERENCES

- 1. Stewart NH, Arora VM. Let's not sleep on it: hospital sleep is a health issue too. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47(6):337‐339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short‐ and long‐term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;9:151‐161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DuBose JR, Hadi K. Improving inpatient environments to support patient sleep. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(5):540‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daou M, Telias I, Younes M, Brochard L, Wilcox ME. Abnormal sleep, circadian rhythm disruption, and delirium in the ICU: are they related? Front Neurol. 2020;11:549908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DePietro RH, Knutson KL, Spampinato L, et al. Association between inpatient sleep loss and hyperglycemia of hospitalization. Diab Care. 2017;40(2):188‐193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mullington JM, Haack M, Toth M, Serrador JM, Meier‐Ewert HK. Cardiovascular, inflammatory, and metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51(4):294‐302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krumholz HM. Post‐hospital syndrome‐‐an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100‐102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Sleep Foundation. Sleep Health Equity: A Position Statement from the National Sleep Foundation. https://www.thensf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/NSF-Position-Statement_Sleep-Health-Equity.pdf (Published online January 2022).

- 9. Jackson CL, Redline S, Emmons KM. Sleep as a potential fundamental contributor to disparities in cardiovascular health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:417‐440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chattu VK, Chattu SK, Spence DW, Manzar MD, Burman D, Pandi‐Perumal SR. Do disparities in sleep duration among racial and ethnic minorities contribute to differences in disease prevalence? J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(6):1053‐1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laposky AD, Van Cauter E, Diez‐Roux AV. Reducing health disparities: the role of sleep deficiency and sleep disorders. Sleep Med. 2016;18:3‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Nursing Choosing Wisely. Twenty‐Five Things Nurses and Patients Should Question. https://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/AANursing-Choosing-Wisely-List.pdf (Published online July 2018).

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home Page. Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://www.hcahpsonline.org/

- 14. McDaniel LM. Improving hospitalized patient sleep: it is easier than it seems. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(7):e115‐e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cho HJ, Wray CM, Maione S, et al. Right care in hospital medicine: co‐creation of ten opportunities in overuse and underuse for improving value in hospital medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):804‐806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trajkovski S, Schmied V, Vickers M, Jackson D. Implementing the 4D cycle of appreciative inquiry in health care: a methodological review. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(6):1224‐1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tan X, van Egmond L, Partinen M, Lange T, Benedict C. A narrative review of interventions for improving sleep and reducing circadian disruption in medical inpatients. Sleep Med. 2019;59:42‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Orlov NM, Arora VM. Things we do for no reason™: routine overnight vital sign checks. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):272‐274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.