Abstract

Objective: Sesame allergy is the most prevalent allergy to seeds. Oral immunotherapy (OIT) is defined as continuous consumption of an allergen at special doses and time. Omalizumab (Anti-IgE) increases tolerance to allergens used in OIT. This study evaluated the effectiveness of a new sesame OIT protocol in patients with sesame anaphylaxis in combination with omalizumab.

Methods: In this prospective open-label interventional trial study, 11 patients with a history of sesame anaphylaxis were enrolled after confirmation by oral food challenge (OFC) test. At baseline, skin prick test (SPT) and skin prick to prick (SPP) test were performed. Serum sesame-specific IgE (sIgE) levels were measured. The maintenance phase was continued at home with daily sesame intake for 4 months. At the end of month 4, the OFC and above-mentioned tests were repeated to evaluate the treatment effectiveness.

Results: All 11 patients who underwent sesame OIT after 4 months could tolerate a dietary challenge of 22 ml tahini (natural sesame seed, equal to 5,000 mg of sesame protein and higher) and the average of wheal diameter in the SPT and SPP tests significantly decreased after desensitization.

Conclusion: This OIT protocol may be a promising desensitization strategy for patients with sesame anaphylaxis. Also, omalizumab appears to have reduced the severity of reactions.

Keywords: Oral Immunotherapy, Desensitization, Sesame anaphylaxis, Oral food challenge, Omalizumab

Sesame allergy is the most common allergy to seeds and its prevalence is increasing worldwide.1 It has been recently estimated that sesame allergy affects 0.23% of US children and adults. A smaller, population-based study performed more than a decade ago introduced sesame as a food allergen, influencing about 0.1% of US children and adults. It shows the prevalence of sesame allergy is increasing.2 Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening systemic, rapid onset reaction that its management is a clinical emergency, especially in sesame allergy.3 Although double-blind placebo oral food challenge (OFC) is the gold standard test for sesame allergy diagnosis,1 on the basis of our previous study, other diagnostic methods such as prick test (SPT), skin prick to prick (SPP), specific IgE (sIgE), and finally, SPP may be suggested for diagnosis of those patients who cannot perform OFC.4 Owing to the lack of a confirmed protocol and the increased sesame consumption in recent years, the true rate of sesame allergy may be higher in Iran.5,6 Clinical manifestations range from mucosal, respiratory, and gastrointestinal to systemic life-threatening symptoms such as anaphylaxis. Therefore, correct diagnosis of sesame allergy is very difficult and OFC is recommended eventually.7

Complete avoidance of allergens was recommended as the only treatment for allergic reactions.8 However, it is difficult to do; thus, oral or sublingual allergen-specific immunotherapy has been proposed as an alternative to food avoidance in food allergies because patients usually try to avoid the culprit food. Oral immunotherapy (OIT) is a type of allergen-specific immunotherapy in which the culprit allergen is continuously administered at a specified dose and is increased according to the prescribed schedule of allergenic food supplementation to induce desensitization over a short period. If desensitization successfully occurs, allergic patients can tolerate higher amounts of allergens without reaction. However, they should consume the allergen to reach the maintenance phase.9 For the first time, an OIT study was conducted on 9 patients aged 6 to 18 years old with sesame allergy. Four patients completed the study and it was shown that OIT was very successful in patients with sesame allergy.10

Nowadays, several ways can be used to improve the safety and effectiveness of OIT, which is the use of omalizumab (a recombinant, humanized, monoclonal antibody against human immunoglobulin E (IgE)).11,12 Omalizumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized IgG1 antibody that binds to the Cϵ3 domain of IgE at the site of FcϵR1 binding, thereby blocking attachment of IgE to basophils and mast cells.13,14 Omalizumab can decrease free serum IgE levels, while the absolute value even may increase. In addition, it reduces the expression of its receptor on primary immune cells, including basophils and dendritic cells; consequently, it may cause immunological changes that increase the chance of tolerance to allergens used in OIT.15 Combining omalizumab with allergen immunotherapy may markedly increase clinical and safety benefits of the treatment.8 This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a new protocol of OIT in patients with sesame anaphylaxis in combination with omalizumab.

Methods and Materials

This prospective single-center, single-arm, open-label interventional trial study was performed on 11 patients whose anaphylaxis to sesame was confirmed by OFC and met all of the inclusion criteria of the study. These patients were recruited to this clinical trial study (IRCT20181002041210N1) from January 2018 to February 2019 to the referral allergy clinic of Rasool-e-Akram Hospital, Tehran, Iran. According to the OFC dosage table4 at the Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, these patients were selected by convenience sampling from more than 50 patients suspected of sesame allergy whose anaphylaxis history was confirmed. The age of all participants ranged from 25 to 55 years and the age of onset of the first anaphylactic reaction to sesame was between 24.4 ± 5.2 years, all of whom had a previous history of trouble-free use of sesame. The inclusion criteria were positive OFC in patients with a history of anaphylactic reaction with or without one of the positive SPT, SPP, or S-IgE tests.4 The exclusion criteria were: age less than 5 years; having a history of cardiovascular diseases (due to the inability to tolerate desensitization and the risk of anaphylaxis); the use of beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors; having severe or uncontrolled asthma; concomitant infectious disease or immunodeficiency and patient’s unwillingness to continue the study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS. FMD.REC1396.9511568001). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and the information remained confidential and anonymous.

Study Design

The severity of the reactions was classified according to the Ring and Messmer classification.16 At the beginning of the study, SPT was performed against sesame and other three important food allergens with the possibility of cross-reactivity, including soybeans, peanuts, and walnuts. After taking a history, each food or aero-allergen was evaluated for patients with standard extract of Greer Laboratories (Lenoir, NC).17 Positive and negative controls were histamine (10 mg/mL) and saline, respectively, and a test was considered positive when wheal diameter ≥ 3 mm compared to negative control.4,18 Also, SPP with tahini (natural sesame seed) and sIgE using ImmunoCAP were performed for all patients.4 Baseline serum levels for specific IgE were also measured by ImmunoCAP assay, so a positive test was defined as IgE ≥ 0.35 KU/L. All positive tests were repeated 4 months after the maintenance of OIT. To enhance the safety and efficacy of immunotherapy, protocol was done with omalizumab in two doses of 150 mg, including one month before OIT and at the beginning of OIT.10 Necessary precautions were strictly considered prior to subcutaneous administration of two doses of omalizumab, including ensuring that the patient is in good health by examining vital signs, evaluating pulmonary and cardiac functions, and examining the liver and kidney tests under physician supervision. The patients were monitored for at least 2 hours after omalizumab administration.

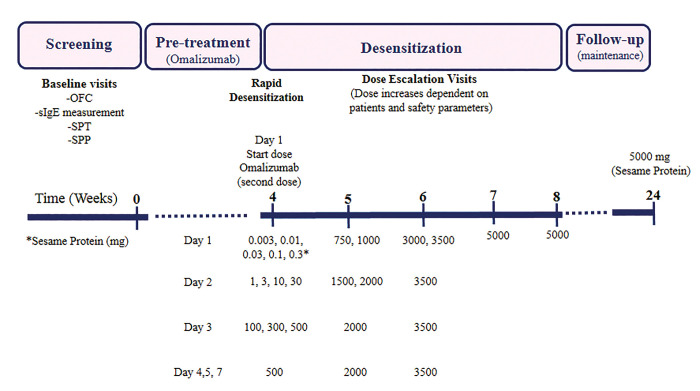

The immunotherapy was performed in two phases: first, induction phase for a total of 4 weeks, including three consecutive days in the first week to reach the initial dose of 500 mg sesame protein, and two consecutive days in the second week to reach the dose of 2,000 mg sesame protein (Figure 1). Subsequently, the process was continued at home and increased, weekly, so that it reached the target dose of 5,000 mg sesame protein over the next two weeks according to the OIT protocol. The interval between increasing doses was at least 30 min. The second phase, known as maintenance, was continued for 4 months at home using a regular daily target dose of sesame tahini (Oghab Halva Company). Since tahini is an oily liquid derived from milled sesame seeds (no change in its allergenicity occurred) and easy to use, it was used in OFC and OIT. Antihistamines and montelukast (an anti-leukotriene receptor antagonist) were also administered as premedication for the safety of the patients.

Figure 1.

Timeline of OIT and sesame protein tolerance in this study.

All procedure steps were carried out in a highly controlled clinical setting under experienced supervision. In case of mild reactions, such as pruritus, urticaria, flushing or rhinoconjunctivitis, antihistamine treatment was prescribed and in case of moderate reactions, including angioedema, sore throat, gastrointestinal symptoms or difficulty breathing (except for wheezing) antihistamines, corticosteroids and salbutamol spray were used, respectively. In case of severe reactions such as cough and shortness of breath with wheezing, or collapse, or hypotension, muscle epinephrine was added to the treatment. At month 4 of the follow-up, the patients were evaluated for SPT and SPP tests and reassessment of specific IgE (in positive cases). The timeline of the study design is summarized in Figure 1.

Statistical Analysis

The normal distribution of variables was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and quantitative variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) and for the qualitative variables, frequency and percentages were used. Quantitative variables were compared by Mann-Whitney U test.19 Comparison between qualitative variables was done by Chi-square test. The results were expressed as odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Data were analyzed by SPSS software version 21 and GraphPad prism version 6. Also, a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 11 patients, 8 patients (72.7%) were male and 3 patients (27.3%) were female aged 25 to 55 years (mean age: 41 years) and age onset of symptoms was 15 to 32 years. The median (IQR) age of the participants was 26 years (range: 23-30 years) and the onset of the first reaction of sesame anaphylaxis was 24 years (range: 22-30 years) without a previous history of reaction following sesame consumption. Demographic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. A family history of sesame allergy was observed in the two patients (15%). Concomitant sensitivity to other food allergens was observed in 30% of the patients that none of which was relevant. Concomitant sensitivity to aeroallergens was also observed in 15% of the patients because of concomitant allergic rhinitis. The most common symptoms were skin pruritus and urticaria in all 11 patients (100%). The rest of the clinical manifestations were cardiac, gastrointestinal, and respiratory appearances, respectively (Table 2). Allergic and non-allergic comorbidity were as follows: rhinitis (36.3%), atopic dermatitis (9%), Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (27.2%), hypertension (18.2%), hypothyroidism (18.2%), and migraine (9%). All patients showed symptoms of allergy to sesame products less than 20 minutes after OFC. The severity of reactions during the OFC ranged from grade I to IV, and most patients were in grade II or higher, and 5 out of 11 patients required epinephrine injection during OFC.

Table 1.

Age of patients at the time of admission, onset, diagnosis and final confirmation of anaphylaxis to sesame

| Cases | Age (years) | Eosinophil /μL |

Total serum IgE (IU/mL) |

Treatment during | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset of symptoms |

Diagnosis | Confirmation | OFC | OIT | |||

| Case 1 | 30 | 30 | 55 | 642 | 381 | Anti-Histamine / GC | Anti-Histamine / GC |

| Case 2 | 25 | 28 | 37 | 161 | 32 | Anti-Histamine / GC/Epinephrine | Anti-Histamine |

| Case 3 | 24 | 25 | 54 | 324 | 189 | Anti-Histamine / GC | Anti-Histamine |

| Case 4 | 15 | 16 | 44 | 120 | 24 | Anti-Histamine / GC/Epinephrine | Anti-Histamine / GC |

| Case 5 | 32 | 32 | 42 | 124 | 280 | Anti-Histamine / GC/Epinephrine | Anti-Histamine / GC |

| Case 6 | 31 | 31 | 40 | 75 | 141 | Anti-Histamine / GC | Anti-Histamine |

| Case 7 | 26 | 27 | 50 | 65 | 136 | Anti-Histamine | Anti-Histamine |

| Case 8 | 23 | 24 | 32 | 138 | 117 | Anti-Histamine / GC | Anti-Histamine |

| Case 9 | 23 | 23 | 28 | 116 | 145 | Anti-Histamine / GC/Epinephrine | Anti-Histamine / GC |

| Case 10 | 18 | 19 | 23 | 85 | 300 | Anti-Histamine / GC | Anti-Histamine |

| Case 11 | 22 | 26 | 38 | 198 | 31 | Anti-Histamine / GC/Epinephrine | Anti-Histamine |

| Range (Min-Max) | 17 (15-32) | 16 (16-32) | 32 (23-55) | 65-642 | 24-381 | - | - |

| Median (IQR) | 24 (22-30) | 26 (23-30) | 40 (32-50) | 124 (85-198) | 141 (32-280) | - | - |

* Initial escalation phase

Abbreviation: GC, Glucocorticoid; IQR, interquartile range; OFC, oral food challenge; OIT, oral immunotherapy; SD, Standard deviation

Table 2.

Frequency of symptoms of sesame consumption when performing OFC

| Allergic reaction during OFC | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Skin reactions (Itching, Urticaria, Flushing, Erythema, Angioedema) | 11 | 100 |

| Cardiovascular reactions (Tachycardia, Hypertension, Hypotension) | 5 | 45.5 |

| Gastrointestinal reactions (Abdominal cramps, Vomiting) | 4 | 36.4 |

| Respiratory reactions (Cough, Wheezing, Dyspnea) | 3 | 27.3 |

Treatment Effectiveness after Passing OFC

All of the patients who underwent sesame OIT after 4 months could tolerate 22 g tahini equal to 5,000 mg (All patients easily up to 25 g and some patients up to 30 g and even higher). Comparison of cumulative dose of sesame protein in OFC before and after the OIT is presented in Table 3 and Figure 2A which is statistically significant (P < 0.004).

Table 3.

Comparison of diagnostic methods with OFC (+) regarding the susceptibility to sesame IgE-dependent allergy

| SPT (wheal diameter) |

SPP (wheal diameter) |

specific IgE (KU/L) | OFC Cumulative dose (mg sesame Protein) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Before OIT |

After OIT | Before OIT |

After OIT | Before OIT |

After OIT | Before OIT |

Initial Escalation day (after omalizumab) |

After OIT |

| Case 1 | Negative (2 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (10 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

0.3 | 10 | 5000 |

| Case 2 | Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (8 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

133 | 144 | 5000 |

| Case 3 | Positive (3 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (10 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

33 | 750 | 5000 |

| Case 4 | Positive (3 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (5 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

433 | 500 | 5000 |

| Case 5 | Positive (3 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (8 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

33 | 44 | 5000 |

| Case 6 | Negative (2 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (5 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

133 | 144 | 5000 |

| Case 7 | Positive (5 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (8 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

13 | 30 | 5000 |

| Case 8 | Positive (6 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (10 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

33 | 44 | 5000 |

| Case 9 | Positive (3 mm) |

Positive (3 mm) |

Positive (5 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (0.65) |

Negative (<0.1) |

133 | 144 | 5000 |

| Case 10 | Positive (6 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (3 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

133 | 144 | 5000 |

| Case 11 | Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Positive (4 mm) |

Negative (0 mm) |

Negative (<0.1) |

Negative (<0.1) |

133 | 750 | 5000 |

Figure 2.

(A) Comparison of cumulative dose of sesame protein tolerance protein between OFC and initial escalation day of OIT after omalizumab. Comparison of wheal size in SPT (B) and SPP (C) before and 4 months after immunotherapy, respectively. (D) Comparison of cumulative dose of sesame protein tolerance protein between OFC and OIT. (E) Comparison of reaction intensities at OFC and OIT. (F) Comparison of different treatments between OFC and During OIT. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The Impact of Treatment on Tests

The median wheal size of SPT and SPP in pre-test and post-test decreased to zero after desensitization (P < 0.008 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 3, Figure 2B and 2C). The level of specific IgE by ImmunoCAP, except for one patient who dropped from 0.6 IU/L before desensitization to less than 0.1 after the treatment was negative in other patients before the treatment (P > 0.9) (Table 3).

The Effect of Pretreatment with Omalizumab and Other Drugs on Treatment Outcome

The cumulative dose of sesame protein during OFC varied from 0.3 to 433 mg of sesame protein and the severity of the reactions varied from grades one to four, and 5 patients needed two doses of epinephrine injection because of anaphylaxis. However, the tolerated cumulative dose of sesame protein increased from 10 to 750 mg of sesame protein during the initial rapid dose in induction phase at the onset of OIT (after pretreatment with antihistamine and administration of two doses of omalizumab (150 mg) according to pretreatment protocol), and the severity of reactions was significantly reduced to grade I and no patients required epinephrine injection at any treatment stage. Comparison of these results is summarized in Table 3 and Figure 2D, 2E, 2F (P < 0.01).

Discussion

Owing to the increasing prevalence, importance, and severity of allergic reactions, lack of self-tolerance with age and even new sensitization in adulthood and, most importantly, complete inability to avoid consumption due to increased use of sesame in food products, it is crucial to provide new therapies, such as oral immunotherapy (OIT), for severe sesame allergy. In this study, we showed that all of the patients who underwent sesame OIT could tolerate 22 g tahini equal to 5,000 mg of sesame protein or higher after 4 months. Moreover, cumulative dose of sesame protein during OFC varied from 0.3 to 433 mg of sesame protein and the severity of reactions varied from grades one to four, while the tolerated cumulative dose of sesame protein increased from 10 to 750 mg of sesame protein during the initial rapid dose at the onset of OIT after pretreatment with omalizumab.

The average sesame anaphylaxis may occur as a new sensitization in adulthood, except for the onset of sesame allergies from childhood. This finding is consistent with the findings of Nabavi et al5 who showed that sesame was one of the three food allergens, leading to anaphylaxis in Iran. Similar studies for example, Dalal et al7 in Israel and Derby et al in England20 have also reported sesame anaphylaxis as de novo.

On the other hand, the interval of about 15 years between the onset of symptoms and anaphylaxis manifestations emphasized that no spontaneous tolerance occurred in most patients with sesame allergy over time. Consistently, Cohen et al21 found that more than 80% of patients with sesame allergy did not tolerate spontaneously. The male to female ratio in this study is 2.6, which may indicate a higher incidence of sesame anaphylaxis in men than women. This finding was also supported by Fazlollahi et al6 who showed the prevalence of sesame allergies in Iran was higher in males. However, in the study of Li et al,22 no significant differences were found regarding age and sex in adult patients with sesame allergy from 2010 to 2016 in the UK. Nevertheless, further epidemiological research is needed in other communities to establish these findings.

In the previous study on diagnostic methods of IgE-mediated sesame allergy, we investigated three important diagnostic methods of SPT, SPP test, and specific IgE level by ImmunoCAP method in comparison to the gold standard (OFC) in patients with a strong history. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the SPP test with natural sesame seed (tahini) might be a good alternative test in cases with a history of sesame anaphylaxis instead of the artificial or commercial extracts of sesame used for SPT. In addition, SPT and sIgE indicated a poor sensitivity, which emphasized poor ability to discriminate between them.4 Nachshon et al23 reported the efficacy and safety of sesame OIT on 60 patients aged over 4 years based on positive OFC. Fifty-three fully desensitized patients (88.4%) continued daily consumption of 1,200 mg sesame protein and were challenged with 4,000 mg after more than 6 months. Four additional patients were desensitized to more than 1,000 mg protein. Reactions were observed in 4.7% of hospital doses and 1.9% of home doses. Epinephrine-treated reactions occurred in 16.7% of patients in hospital and 8.3% in home doses; however, they did not use omalizumab in the pretreatment stage. It is one of the possible reasons for 100% efficacy of the present protocol regarding the development of tolerance for target doses above 5,000 mg. Further, no severe side effects and no need for epinephrine at all stages of the treatment may be attributed to the use of omalizumab as an adjuvant. In another study, Costa-Paschoalini et al24 reported a 48-year-old white woman with anaphylaxis or skin reactions to sesame-rich foods beginning at the age of 27 years. The desensitization process was done in four phases started using diluted crude white sesame extract with 0.0001 mg up to 10 mg, 5 doses per day. Doses were increased weekly. In the fourth and last phase, 1,500 mg tahini was given once a day, for 1 week and then 3,000 mg once a day for 4 weeks. The patient then underwent OFC, which was negative. Our OIT protocol had 2 phases for a total of 4 weeks, including three consecutive days in the first week to reach the daily dose of 500 mg sesame protein (build-up), and two consecutive days in the second week to reach the dose of 2,000 mg sesame protein (maintenance). Subsequently, the process was continued at home and increased weekly so that it reached the target dose of 5,000 mg sesame protein over the next two weeks.

Omalizumab was used as an adjuvant treatment to decrease the severity of patients’ reactions in OFC and improve the protocol efficacy and safety, and the effectiveness of OFC treatment. Four months after the maintenance phase, all 11 patients not only succeed in tolerating the total dose prescribed for the initial OFC but also tolerated the total dose prescribed in the OIT and even more easily. Recent studies have shown that the effects of omalizumab on lowering serum IgE levels and decreasing the expression of its receptor on primary immune cells, including basophils and dendritic cells can cause immunological changes that increase tolerance to allergens transmitted by immunotherapy. Combining omalizumab with allergen immunotherapy increases the clinical and safety benefits.24 Accordingly, we also used pretreatment with omalizumab as well as antihistamine in the protocol of this study to enhance the safety of treatment by considering the severity of reactions in the initial history and OFC at baseline. In this study, no patient, despite a history of severe anaphylactic reactions in the history and at OFC, showed anaphylactic reaction at any of the build-up and maintenance phases (without complications) and all treatments were safe. Probably one of the reasons for the increased effectiveness of the present study in achieving the final target dose of all patients compared to the similar treatment conducted on Israeli children in which only 4 of the 9 patients were able to receive complete treatment25 is that this protocol was accompanied by the adjuvant of omalizumab.

The effect of omalizumab therapy in this study was evident through increased safety and implementation of uncomplicated induction therapy. It was shown that grading the severity of patients’ reactions in habitual reactions changed from grades 1 to 4 and in OFC to grade 1 and 2 in the induction phase of the treatment after administration of omalizumab and in the build-up, and maintenance phase reached to grade 0 and 1. In the course of OFC, 5 out of 11 patients needed epinephrine treatment, even one of them required two doses of epinephrine injection due to hypotension (these results indicate the high severity of reactions in sesame anaphylaxis and strongly recommended not to perform diagnostic and therapeutic tests in outpatient clinics without equipment), but after administration of omalizumab and pretreatment, the patients did not have severe reactions requiring epinephrine at any stage of the immunotherapy even in the phase of rapid initial growth. The effectiveness of using omalizumab to improve treatment efficacy and safety in this study was consistent with other studies that have used this method in other immunotherapies of food allergies. For example, Nadeau et al11 used omalizumab in combination with OIT in four children with milk allergy that showed simultaneous administration of omalizumab increased the rate and tolerance of OIT. In another study, omalizumab and OIT were used in three high-risk children with peanut allergy in the United States, where one patient out of 5 failed to complete treatment and reached the target dose, and only one patient had nausea and vomiting.26 This study has several limitations. First, this study was a single-arm study in which treatment bias cannot be absolutely excluded. Second, this is a single-center study and its results should be investigated in other centers. Third, the sample size was small; thus, to better understand the mechanisms of treatment effect, it is necessary to study the diverse populations with a larger sample size. Most studies with the pretreatment with omalizumab in patients with complicated venom immunotherapy showed that omalizumab should be given long-term in order to prevent systemic reactions following allergen injection. So, the explanation that good long-term tolerance was due to omalizumab given before rush phase of OIT is weak.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of oral immunotherapy (OIT) in combination with omalizumab in patients with sesame anaphylaxis, which increases response threshold, protects them against accidental exposure, and promises an appropriate approach for treating this kind of food allergy. All patients could tolerate an oral food challenge with 5,000 mg sesame protein after a 4-month desensitization period. The use of omalizumab adjuvant in this treatment protocol also clearly reduced the severity of reactions during treatment, making this treatment a safe and rapid procedure. Since severe anaphylactic reactions require epinephrine injection, OIT should be performed only under appropriate conditions in specialized centers of Immunology and Allergy. Future prospective double-blind randomized controlled trials on higher sample population may provide new insights into the durability and persistence of OIT. Further studies are also suggested to compare the effectiveness of omalizumab in the treatment protocol of sesame immunotherapy with a control group without the use of omalizumab.

Author Contributions

Fe.Sa conceived the study; MHB, MF, SAM, S.Sh., MN, SA were responsible for the patient care and data collection. Fe.Sa. and MK analyzed and interpreted the data. Fa.Se. drafted the manuscript and revised it for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Adatia A, Clarke A, Yanishevsky Y, Ben-Shoshan M.. Sesame allergy: current perspectives. J Asthma Allergy. 2017;10:141-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren CM, Chadha AS, Sicherer SH, Jiang J, Gupta RS.. Prevalence and severity of sesame allergy in the United States. JAMA network open. 2019;2(8):e199144-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nabavi M, Lavavpour M, Arshi S, et al. Characteristics, etiology and treatment of pediatric and adult anaphylaxis in Iran. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;16(6):480-487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salari F, Bemanian MH, Fallahpour M, et al. Comparison of Diagnostic Tests with Oral Food Challenge in a Clinical Trial for Adult Patients with Sesame Anaphylaxis. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;19(1):27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabavi M, Lavavpour M, Arshi S, et al. Characteristics, etiology and treatment of pediatric and adult anaphylaxis in Iran. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;16(6):480-487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fazlollahi M, Pourpak Z, Yeganeh M, et al. Sesame seed allergy: clinical manifestations and laboratory investigations. Tehran University Medical Journal TUMS Publications. 2007;65(8):85-90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalal I, Goldberg M, Katz Y.. Sesame seed food allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2012;12(4):339-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bégin P, Winterroth LC, Dominguez T, et al. Safety and feasibility of oral immunotherapy to multiple allergens for food allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2014;10(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rekabi M, Arshi S, Bemanian MH, et al. Evaluation of a new protocol for wheat desensitization in patients with wheat-induced anaphylaxis. Immunotherapy. 2017;9(8):637-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg MR, Levy MB, Appel MY, et al. Oral Immunotherapy for Sesame Food Allergy: Interim Analysis [abstract]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(2):AB124. Abstract 408. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadeau KC, Schneider LC, Hoyte L, Borras I, Umetsu DT.. Rapid oral desensitization in combination with omalizumab therapy in patients with cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(6):1622-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ledford DK. Omalizumab: overview of pharmacology and efficacy in asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9(7):933-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vashisht P, Casale T.. Omalizumab for treatment of allergic rhinitis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13(6):933-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babu KS, Polosa R, Morjaria JB.. Anti-IgE – emerging opportunities for Omalizumab. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13(5):765-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliver JM, Tarleton CA, Gilmartin L, et al. Reduced FcepsilonRI-mediated release of asthma-promoting cytokines and chemokines from human basophils during omalizumab therapy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;151(4):275-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ring J, Messmer K.. Incidence and severity of anaphylactoid reactions to colloid volume substitutes. Lancet. 1977;309(8009):466-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Permaul P, Stutius LM, Sheehan WJ, et al., eds. Sesame allergy: role of specific IgE and skin prick testing in predicting food challenge results. Allergy and asthma proceedings; 2009: NIH Public Access. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yousefi A, Nasehi S, Arshi S, et al. Assessment of IgE- and cell-mediated immunity in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;53(2):86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Mousavi M, et al. Interleukin-21 receptor might be a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Clin Med. 2014;6(2):57-61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derby CJ, Gowland MH, Hourihane JOB.. Sesame allergy in Britain: A questionnaire survey of members of the Anaphylaxis Campaign. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16(2):171-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen A, Goldberg M, Levy B, Leshno M, Katz Y.. Sesame food allergy and sensitization in children: the natural history and long-term follow-up. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(3):217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li PH, Gunawardana N, Thomas I, et al. Sesame allergy in adults: Investigation and outcomes of oral food challenges. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(3):285-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nachshon L, Goldberg MR, Levy MB, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Sesame Oral Immunotherapy—A Real-World, Single-Center Study. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2019;7(8):2775-81. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa Paschoalini M, Bernardes AF, Buzolin M, et al. Successful Oral Desensitization in Sesame Allergy in an Adult Woman. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2019;29(6):463-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burbank AJ, Sood P, Vickery BP, Wood RA.. Oral immunotherapy for food allergy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2016;36(1):55-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider LC, Rachid R, LeBovidge J, Blood E, Mittal M, Umetsu DT.. A pilot study of omalizumab to facilitate rapid oral desensitization in high-risk peanut-allergic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(6):1368-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]