Abstract

Background

Platelet transfusion carries risk of transfusion‐transmitted infection (TTI). Pathogen reduction of platelet components (PRPC) is designed to reduce TTI. Pulmonary adverse events (AEs), including transfusion‐related acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) occur with platelet transfusion.

Study design

An open label, sequential cohort study of transfusion‐dependent hematology‐oncology patients was conducted to compare pulmonary safety of PRPC with conventional PC (CPC). The primary outcome was the incidence of treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation (TEAMV) by non‐inferiority. Secondary outcomes included: time to TEAMV, ARDS, pulmonary AEs, peri‐transfusion AE, hemorrhagic AE, transfusion reactions (TRs), PC and red blood cell (RBC) use, and mortality.

Results

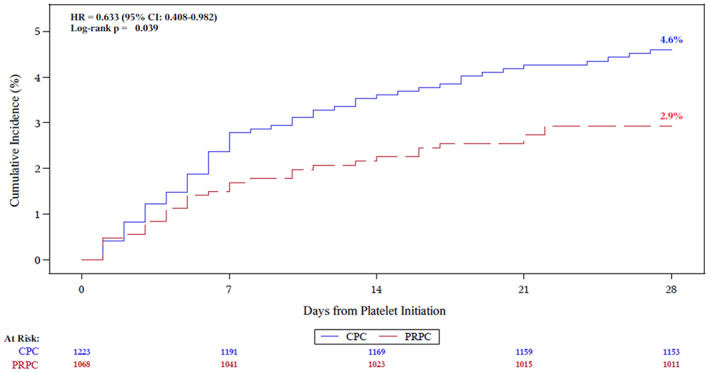

By modified intent‐to‐treat (mITT), 1068 patients received 5277 PRPC and 1223 patients received 5487 CPC. The cohorts had similar demographics, primary disease, and primary therapy. PRPC were non‐inferior to CPC for TEAMV (treatment difference −1.7%, 95% CI: (−3.3% to −0.1%); odds ratio = 0.53, 95% CI: (0.30, 0.94). The cumulative incidence of TEAMV for PRPC (2.9%) was significantly less than CPC (4.6%, p = .039). The incidence of ARDS was less, but not significantly different, for PRPC (1.0% vs. 1.8%, p = .151; odds ratio = 0.57, 95% CI: (0.27, 1.18). AE, pulmonary AE, and mortality were not different between cohorts. TRs were similar for PRPC and CPC (8.3% vs. 9.7%, p = .256); and allergic TR were significantly less with PRPC (p = .006). PC and RBC use were not increased with PRPC.

Discussion

PRPC demonstrated reduced TEAMV with no excess treatment‐related pulmonary morbidity.

Keywords: assisted mechanical ventilation, pathogen reduction, platelet transfusion, pulmonary adverse events

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- AMV

assisted mechanical ventilation by intubation or tight‐fitting mask with positive pressure

- CPC

conventional platelet components

- CSPAE

clinically significant pulmonary adverse events (CTCAE criteria ≥Grade 2)

- mITT

modified intent‐to‐treat

- PP

per protocol

- PRPC

pathogen‐reduced platelet components

- SAE

serious adverse event

- TEAMV

treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation by intubation or tight‐fitting mask with positive pressure

- TEAMV‐PD

treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation with pulmonary dysfunction by blinded adjudication

- TEARDS

treatment‐emergent acute respiratory distress syndrome by Berlin criteria

- TR

transfusion reaction

1. INTRODUCTION

Amotosalen‐UVA pathogen reduction (PR) of platelet components (INTERCEPT Blood System for Platelets®; Cerus Corporation) is licensed to reduce the risk of transfusion‐transmitted infection (TTI) and transfusion‐associated graft versus host disease. The PR process meets the FDA guidance to reduce risk of bacterial contamination. 1

EU and US use of Amotosalen‐UVA PR platelets is expanding. A previous Phase 3 clinical trial of PR of platelet components (PRPCs) detected an increased incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), but not transfusion‐related acute lung injury (TRALI), compared with conventional PC (CPC). 2 , 3 , 4 Hematology‐oncology patients require PC transfusion and are at risk of pulmonary injury including ARDS from primary disease and therapy complications. 5 We conducted a prospective Phase 4 surveillance study as a post marketing FDA commitment, to determine if PRPC potentiated the incidence of clinically significant pulmonary adverse events (AEs) including ARDS and TRALI. Elucidating potential excess treatment related morbidity of PRPC is relevant to the decision process to implement PRPC.

The incidence of pulmonary injury and use of treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation (TEAMV) in association with PC transfusion was previously uncertain in the hematology‐oncology patient population. TEAMV is a clinically significant intervention for patients resulting in substantial patient care and costs. This study presents a large experience of platelet transfusion in hematology‐oncology patients to compare the pulmonary safety of CPC and PRPC platelet transfusions in patients with concurrent comorbidities for pulmonary dysfunction and TTI risk.

2. METHODS

2.1. Overall design

The study evaluated the safety of PC transfusion in routine practice for hematology‐oncology patients, including hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT), according to standard of care. It used a prospective, open‐label, non‐randomized, sequential, two‐cohort design. The first cohort received CPC. After completion of the CPC cohort, each site enrolled a second cohort supported with PRPC. Patients in the first cohort were not re‐enrolled in the second cohort. The PRPC cohort was matched to the first cohort ±10% by four baseline therapy strata (chemotherapy, HCT with myeloablation, HCT without myeloablation, and HCT with reduced intensity conditioning) at each site to adjust for primary therapy impact on pulmonary injury. 6 The proportion of patients within each therapy strata for the first cohort (CPC) set the by‐site distribution for the second cohort (PRPC) at each site. The trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02549222.

2.2. Clinical execution

The study enrolled patients expected to require one or more PC transfusions for thrombocytopenia up to 21‐days of transfusion support with 7 days of follow‐up after the last study PC. Patients were enrolled at 15 clinical sites (Table S1, Data Supplement). Non‐study physicians ordered all PC transfusions according to standard of care. Data were obtained from patient medical records with anonymity in compliance with HIPAA. Sites were requested to enroll 50–100 patients in each cohort. The study protocol was approved by each site's Institutional Research Board and depending on local regulations, written informed consent was required or waived with patient oral consent documented in the medical record. There were no study specific interventions.

2.3. Clinical outcomes

Clinical outcome data were obtained from patient medical records, entered in electronic study case report forms, and monitored against primary source data. The primary outcome was the incidence of TEAMV by intubation or tight‐fitting mask with positive inspiratory pressure for any indication after the first study PC transfusion. All patients with the endpoint of TEAMV were evaluated by a blinded pulmonary expert panel (PEP) for adjudication of the type of pulmonary injury, ARDS by the Berlin criteria, 7 and for causal relation to platelet transfusion. Secondary outcomes of pulmonary injury, peri‐transfusion AEs, and mortality were assessed. Specific secondary outcomes were as follows: time to TEAMV after initiation of PC support, the incidence of treatment‐emergent acute respiratory distress syndrome (TEARDS) according to the Berlin Consensus criteria by PEP adjudication, clinically significant pulmonary adverse events (CSPAE: CTCAE Grade 2 and higher) within 7 days of each transfusion, all AEs within 24 h of each PC transfusion, all AE classified as transfusion reactions (TRs) within 24 h of each PC exposure, all serious adverse events (SAEs) within 7 days of each study PC, and mortality up to 28 days after initiation of study PC. Blinded clinical data for adjudication of TEAMV endpoint patients submitted to the PEP included: PC exposure, all pulmonary imaging studies, respiratory therapy, and a clinical narrative for each patient.

2.4. Study platelet components

CPCs were prepared from whole blood or apheresis collections with leukocyte reduction, suspended in plasma or plasma with platelet additive solution (PAS). CPCs were screened for bacterial contamination using currently available methods. This generally consisted of 8 ml of PC tested by aerobic bacterial culture. CPCs were gamma‐irradiated according to each study site's patient‐specific standard of care.

PRPC were prepared by apheresis with leukocyte reduction and suspended in either plasma (Trima; Terumo US) or plasma with PAS (Amicus, Fenwal US). PRPCs were treated with the INTERCEPT Blood System for Platelets (Cerus) in place of bacterial screening and gamma irradiation. Both CPCs and PRPCs were stored for up to 5 days prior to transfusion. Platelet dose was not measured for individual components, but study sites complied with FDA criteria for PC dose ≥3.0 × 1011 platelets.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The statistical hypothesis, requested by FDA, was based on non‐inferiority analysis for the incidence of TEAMV: H0 (null hypothesis): pPRPC−pCPC ≥ 0.023 versus H1 (alternative hypothesis): pPRPC−pCPC < 0.023, where pPRPC and pCPC are the proportion of patients requiring TEAMV during the study observation period for PRPC and CPC cohorts, respectively. The non‐inferiority margin of 2.3% for TEAMV was based on modeling from a database reporting pulmonary injury in HCT patients (Data Supplement, Methods). The non‐inferiority test was assessed by comparing the upper bound of the two‐sided Miettinen and Nurminen Score 95% confidence interval, controlling for primary disease therapy, for the treatment difference (PRPC−CPC).

The primary analysis included all modified intent‐to‐treat (mITT) patients, defined as patients who received any study PC after enrollment. The per protocol (PP) analysis included all subjects in each study cohort who received all PC transfusions in compliance with the correct cohort assignment (Data Supplement).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted with propensity scores, with covariates considered in the logistic regression including the following: clinical site, age, sex, race, smoking history, alcohol use history, medical histories (e.g., cardiac disease, pulmonary disease, hematologic disease, other relevant disease, TR), primary disease therapy, and baseline primary diagnosis (e.g., lymphoma, leukemia, myeloma). Similar non‐inferiority analysis and sensitivity analyses also were conducted for the proportion of patients requiring TEAMV indicated for pulmonary dysfunction (TEAMV‐PD) determined by the PEP (excluding TEAMV for sleep apnea, transient surgical anesthesia, and airway protection). Furthermore, the proportions of patients with any AE, any TR, any SAE, any ARDS (as reported AE data and as determined by PEP assessment per the Berlin criteria), all‐cause death, and any CSPAE were compared between treatment groups using a stratified Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test (General Association) controlling for the four strata of primary disease therapy. The time to onset of TEAMV from the first study PC transfusion was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the treatment difference was explored by the Cox model Wald test adjusted for primary disease therapy. For continuous variables (e.g., duration of study platelet support), p‐values for treatment difference were based on an ANOVA model including treatment and primary disease therapy as fixed effects. For categorical variables, p‐values for treatment comparison were based on a stratified CMH test (Row Mean Scores Differ for ordinal data and General Association for non‐ordinal data) controlling for primary disease therapy. Unless otherwise stated, statistical significance was set at the two‐sided .05 alpha level.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics, prior medical history, primary disease, and primary therapy factors

Modified ITT analysis included 2291 patients (1068 PRPC and 1223 CPC, Data Supplement, Figure S1). Sex demographics were similar between cohorts, but PRPC cohort mean age was greater (Table 1). The PRPC cohort had significantly higher incidence of prior pulmonary and cardiac disease, and prior TRs (Table 1). The proportional distributions of current hematologic diseases were statistically different between cohorts, but both cohorts had substantial numbers of patients in each disease group (Table 1). The proportions of patients with recurrent disease and refractory disease were not different between cohorts (Table 1). The proportions of patients by primary therapy strata were not statistically different between the mITT cohorts; and were within the ±10% protocol criteria (Table 1). Due to small numbers of patients with RIC and non‐myeloablative therapies, these strata were combined for presentation, but four strata were used for statistical analyses. PRPC cohort subjects received more local radiation, and less total body radiation. The PP data set demonstrated statistical differences between the cohorts with more HCT in the PRPC cohort with less allogeneic HCT and with small differences in use of total body radiation (Table S2, Data Supplement).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics, medical history, primary disease and primary disease therapy for mITT and per protocol populations

| Patient population demographics, medical history, and primary disease history (mITT) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Chemotherapy | HCT myeloablative | HCT non‐ablative + RIC | Total | PRPC‐CPC | ||||

| Cohort | PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | |

| Patients in cohort (n) | 524 | 717 | 405 | 374 | 139 | 132 | 1068 | 1223 | |

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 57.1 ± 18.7 | 50.5 ± 23.8 | 56.1 ± 13.4 | 51.4 ± 17.9 | 58.8 ± 14.7 | 53.2 ± 18.3 | 57.0 ± 16.4 | 50.8 ± 21.6 | <0.001* |

| Male sex: (%) | 58.6 | 55.2 | 59.5 | 61.0 | 64.7 | 58.3 | 59.7 | 57.3 | 0.310 |

| medical history | |||||||||

| Prior pulmonary disease | 257 (49.0) | 316 (44.1) | 159 (39.3) | 124 (33.2) | 69 (49.6) | 59 (44.7) | 485 (45.4) | 499 (40.8) | 0.009* |

| Prior cardiac disease | 336 (64.1) | 411 (57.3) | 247 (61.0) | 195 (52.1) | 91 (65.5) | 81 (61.4) | 674 (63.1) | 687 (56.2) | <0.001* |

| Prior transfusion reaction | 114 (21.8) | 111 (15.5) | 18 (4.4) | 12 (3.2) | 16 (11.5) | 17 (12.9) | 148 (13.9) | 140 (11.4) | 0.008* |

| primary disease prior to study | |||||||||

| Leukemia | 306 (58.4) | 429 (59.8) | 35 (8.6) | 46 (12.3) | 42 (30.2) | 39 (29.5) | 383 (35.9) | 514 (42.0) | <0.001* |

| Lymphoma | 87 (16.6) | 83 (11.6) | 120 (29.6) | 95 (25.4) | 24 (17.3) | 14 (18.2) | 231 (21.6) | 202 (16.5) | |

| Myeloma | 27 (5.2) | 35 (4.9) | 218 (53.8) | 192 (51.3) | 26 (18.7) | 31 (23.5) | 271 (25.4) | 258 (21.1) | |

| MDS/myeloproliferative | 4 (0.8) | 18 (2.5) | 3 (0.7) | 6 (1.6) | 7 (5.0) | 13 (9.8) | 14 (1.3) | 37 (3.0) | |

| Myelodysplastic | 47 (9.0) | 49 (6.8) | 5 (1.2) | 3 (0.8) | 26 (18.7) | 11 (8.3) | 78 (7.3) | 63 (5.2) | |

| Other disease | 53 (10.1) | 103 (14.4) | 24 (5.9) | 32 (8.6) | 14 (10.1) | 14 (10.6) | 91 (8.5) | 149 (12.2) | |

| Recurrent disease | 169 (32.3) | 227 (31.7) | 105 (25.9) | 109 (29.1) | 43 (30.9) | 44 (33.3) | 317 (29.7) | 380 (31.1) | 0.622 |

| Refractory disease | 147 (28.1) | 187 (26.1) | 58 (14.3) | 75 (20.1) | 26 (18.7) | 38 (28.8) | 231 (21.6) | 300 (24.5) | 0.124 |

| Primary therapy on study | |||||||||

| Any HCT 1 | 58 (11.1) | 97 (13.5) | 405 (100) | 374 (100) | 139 (100) | 132 (100) | 602 (56.4) | 603 (49.3) | 0.056 |

| Autologous | 26 (5.0) | 31 (4.3) | 351 (86.7) | 300 (80.2 | 38 (27.3) | 40 (30.3) | 415 (38.9) | 371 (30.2) | |

| Allogeneic | 32 (6.1) | 66 (9.2) | 54 (13.3) | 74 (19.8) | 101 (72.7) | 92 (69.7) | 187 (17.5) | 232 (19.0) | |

| Chemotherapy no HCT | 466 (88.9) | 620 (86.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 466 (43.6) | 624 (50.7) | |

| Local radiation | 68 (13.0) | 86 (12.0) | 74 (18.3) | 57 (15.2) | 17 (12.2) | 14 (10.6) | 159 (14.9)) | 157 (12.8) | 0.010* |

| No local radiation | 453 (86.5) | 626 (87.3) | 329 (81.2) | 306 (81.8) | 122 (87.8) | 114 (86.4) | 904 (84.6) | 1046 (85.5) | |

| Total body radiation | 7 (1.3) | 21 (2.9) | 8 (2.0) | 7 (1.9) | 10 (7.2) | 10 (7.6) | 25 (2.3) | 38 (3.1) | 0.038* |

| No total body Radiation | 512 (97.7) | 690 (96.2) | 396 (97.8) | 357 (95.5) | 129 (92.8) | 119 (90.2) | 1037 (97.1) | 1166 (95.3) | |

*p < 0.05 level of significance.

1HCT = hematopoietic cell transplant.

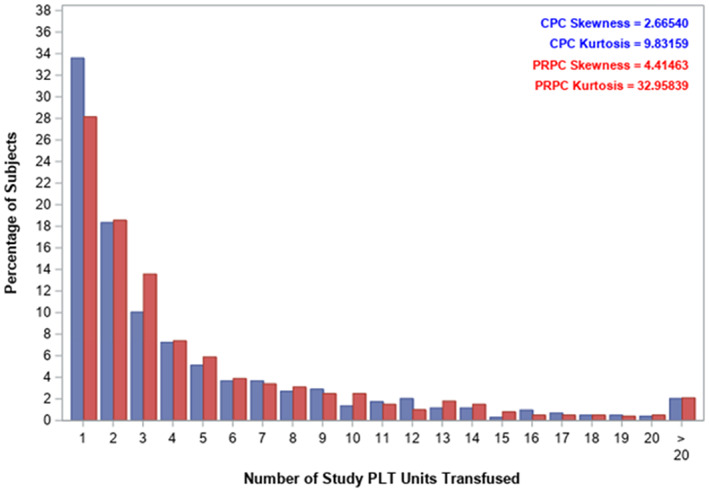

3.2. Platelet transfusion exposure

Mean PC exposure by mITT was statistically larger for PRPC than CPC (4.9 ± 6.1 vs. 4.5 ± 5.1, p = .046) (Table 2), but not significantly different by PP analysis (4.8 ± 6.0 vs. 4.5 ± 5.2, p = .153) (Table 2). The distributions of PC transfused PP were skewed (Figure 1). The mean days of platelet support were not different for PRPC and CPC (6.4 ± 6.3 vs. 6.7 ± 6.8, p = .447) (Table 2). For the PP analysis, 4795 PRPC were transfused of which 78.5% were suspended in plasma‐PAS and 15.2% in plasma. In contrast for the PP analysis 4663 CPC were transfused of which 13.8% were suspended in plasma‐PAS and 81.9% in plasma; and unrecorded for 7.7% PRPC and 2.7% CPC. Patients in each cohort received a mix of PC suspended in plasma‐PAS or 100% plasma depending on PC availability.

TABLE 2.

Exposure to study platelet and red blood cell (RBC) components by mITT and per protocol analysis by primary disease therapy strata

| Modified intention‐to‐treat analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Chemotherapy | HCT myeloablative | HCT non‐ablative + RIC | Total | PRPC‐CPC a | ||||

| PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | ||

| Patients (n) | 524 | 717 | 405 | 374 | 139 | 132 | 1068 | 1223 | |

| PC transfused | |||||||||

| Mean | 4.3 ± 4.2 | 4.5 ± 5.0 | 4.6 ± 6.1 | 3.6 ± 4.3 | 8.4 ± 9.8 | 6.8 ± 7.1 | 4.9 ± 6.1 | 4.5 ± 5.1 | 0.046* |

| Median | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| Days of PC support b | |||||||||

| Mean | 6.9 ± 6.7 | 7.2 ± 7.1 | 4.7 ± 4.8 | 5.0 ± 5.3 | 9.2 ± 7.2 | 9.2 ± 7.8 | 6.4 ± 6.3 | 6.7 ± 6.8 | 0.447 |

| Median | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | |

| RBC components transfused | |||||||||

| Patients: n (%) | 357 (68) | 454 (63) | 188 (46) | 184 (49) | 94 (68) | 78 (59) | 639 (60) | 716 (59) | |

| Mean | 3.1 ± 2.8 | 3.5 ± 3.3 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 3.9 ± 3.0 | 4.0 ± 3.2 | 3.0 ± 2.7 | 3.3 ± 3.1 | 0.146 |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Per protocol analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Chemotherapy | HCT myeloablative | HCT non‐ablative + RIC | Total | PRPC‐CPC | ||||

| PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | PRPC | CPC | ||

| Patients: n (%) | 490 | 545 | 385 | 362 | 127 | 129 | 1002 | 1036 | |

| PC transfused | |||||||||

| Mean | 4.3 ± 4.2 | 4.6 ± 5.1 | 4.4 ± 5.9 | 3.6 ± 4.3 | 8.1 ± 10.0 | 6.9 ± 7.1 | 4.8 ± 6.0 | 4.5 ± 5.2 | 0.153 |

| Median | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| Days of PC support | |||||||||

| Mean | 6.7 ± 6.7 | 7.2 ± 7.1 | 4.5 ± 4.5 | 4.8 ± 5.1 | 8.7 ± 7.0 | 9.3 ± 7.7 | 6.1 ± 6.2 | 6.6 ± 6.7 | 0.148 |

| Median | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | |

| RBC components transfused | |||||||||

| Patients: n (%) | 331 (68) | 346 (63) | 176 (46) | 174 (48) | 83 (65) | 77 (60) | 590 (59) | 597 (58) | |

| Mean | 3.0 ± 2.8 | 3.6 ± 3.5 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 3.6 ± 2.5 | 4.0 ± 3.2 | 2.9 ± 2.6 | 3.3 ± 3.2 | 0.016* |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

For continuous variables, p‐values (for treatment difference) are based on an ANOVA model including treatment and 4‐category primary disease therapy (chemotherapy, HCT‐myeloablative, HCT‐non‐myeloablative, and HCT‐RIC) as fixed effects. A point estimate and the corresponding two‐sided 95% CI for the treatment difference in least squares means are also provided. For categorical variables, the p‐values are based on a stratified CMH General Association PRPC controlling for primary disease therapy. A p‐value <.050 is flagged with an asterisk (*).

Days of platelet support period = (date of last study or non‐study platelet transfusion, up to Day 21 or platelet independence, whichever occurred sooner)−(date of first study transfusion) + 1, where platelet independence is defined as more than 5 days elapsed from the previous study or non‐study platelet transfusion.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of the number of platelet components transfused for the per protocol analysis (blue— conventional PC, red—PRPC) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.3. Primary outcome: Incidence of treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation

The incidence of TEAMV in the PRPC cohort was non‐inferior to CPC (mITT treatment difference = −1.7%, 95% CI: [−3.3, −0.1%], Table 3). Sensitivity analyses by mITT using the described baseline covariates confirmed non‐inferiority of TEAMV incidence of PRPC (treatment difference = −1.2%, 95% CI: (−2.8%, 0.4%). Because 34% of CPC patients and 28% of PRPC patients received only one platelet transfusion, a secondary ad hoc mITT analysis for non‐inferiority was performed for CPC (n = 816) and PRPC (773) patients who received two or more PC transfusions. This analysis confirmed non‐inferiority of PRPC for the incidence of TEAMV (treatment difference = −2.4%, 95% CI: (−4.5%, −0.2%).

TABLE 3.

Incidence of treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation and treatment‐emergent acute respiratory distress syndrome

| Modified intention‐to‐treat analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | PRPC n = 1068 | CPC n = 1223 | PRPC versus CPC a |

| Treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation and platelet component exposure | |||

| Patients with TEAMV: n (%) b | 31 (2.9) | 56 (4.6) | −1.7% (−3.3%, −0.1%) |

| Median days to TEAMV c | >30 | >30 | 0.076 |

| Patients with TEAMV‐PD: n (%) d | 18 (1.7) | 38 (3.1) | −1.5% (−2.7%, −0.2%) |

| LS mean days to TEAMV after PC for 56 patients with TEAMV‐PD e | 10.7 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 1.2 | 4.6 (0.3, 8.9) |

| Treatment‐emergent ARDS for TEAMV‐PD: n (%) f | 11 (1.0) | 22 (1.8) | 0.151 |

| PC exposure in patients with TEAMV‐PD (n ± SD) g | 22.6 ± 22.1 | 13.6 ± 9.2 | 0.493 |

| Days of PC support in patients with TEAMV‐PD (n ± SD) h | 14.8 ± 7.0 | 14.1 ± 7.2 | 0.632 |

| Per protocol analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation and platelet component exposure | |||

| Parameter | PRPC n = 1002 | CPC n = 1036 | PRPC versus CPC a |

| Patients with TEAMV: n (%) b | 26 (2.6) | 39 (3.8) | −1.3% (−2.9%, 0.3%) |

| Median days to TEAMV c | >30 | >30 | 0.199 |

| Patients with TEAMV ‐PD: n (%) d | 14 (1.4) | 25 (2.4) | −1.2% (−2.5%, 0.0%) |

| LS Mean Days to TEAMV after PC for 39 Patients with TEAMV‐PD e | 9.1 | 6.8 | 2.2 (−1.7, 6.2) |

| Treatment‐emergent ARDS for TEAMV‐PD: n (%) f | 8 (0.8) | 16 (1.5) | 0.132 |

| PC exposure in patients with TEAMV‐PD (n ± SD) g | 26.1 ± 23.4 | 15.7 ± 9.8 | 0.278 |

| Days of PC support in patients with TEAMV‐PD (n ± SD) h | 15.9 ± 6.4 | 14.4 ± 7.4 | 0.977 |

For non‐inferiority analysis the treatment difference (T‐C) and the 95% confidence interval is presented. For continuous variables, p‐values (for treatment difference) are based on an ANOVA model including treatment and 4‐category primary disease therapy (chemotherapy, HCT‐myelo, HCT‐non‐myelo, and HCT‐RIC) as fixed effects. A point estimate and the corresponding two‐sided 95% CI for the treatment difference in LS‐means are also provided. For categorical variables, p‐values are based on a stratified CMH PRPC (General Association), controlling for primary disease therapy. A p‐value <.050 is flagged with an asterisk (*).

Time in days from first study PC transfusion to the initiation of TEAMV for pulmonary injury evaluated by the PEP. Least‐squares (LS) means were derived from a negative binomial model with transfusion history as a covariate.

Protocol defined treatment‐emergent assisted mechanical ventilation (TEAMV) is defined as any patient with ventilation by tight‐fitting mask or intubation with positive end expiratory pressure ≥5 cmH2O initiated after the first exposure to study PC.

Median days to protocol defined TEAMV by Kaplan Meier method.

Patients with TEAMV‐PD indicated for pulmonary disease evaluated by the blinded PEP based on review of clinical records, respiratory therapy, and all chest imaging studies in the medical record. Based on review of 93 patients with protocol defined or deviant TEAMV.

Treatment‐emergent acute respiratory syndrome (TEARDS) in patients with TEAMV to treat pulmonary injury assessed by the PEAP was evaluated according to the Berlin Criteria for ARDS.

Number of platelet components (PCs) transfused to patients during the active transfusion period of up to 21 days.

Days of platelet support period = (date of last study or non‐study platelet transfusion, up to day 21 or platelet independence, whichever sooner)−(date of first study transfusion) + 1, where platelet independence is defined as more than 5 days elapsed from the previous study or non‐study platelet transfusion.

The PP analysis for all patients confirmed non‐inferiority of PRPC (treatment difference = −1.3%, 95% CI: (−2.9, 0.3%). The ad hoc PP analysis for patients who received two or more PC transfusions also confirmed TEAMV incidence non‐inferiority for PRPC (n = 720) to CPC (n = 688), treatment difference = −2.0%, 95% CI: (−4.2%, 0.3%).

The cumulative incidence of TEAMV by mITT was significantly less for PRPC (p = .039) (Figure 2). Similarly, for patients in each cohort who received two or more PC transfusions the cumulative incidence of TEAMV was significantly less for PRPC (3.7%) compared with CPC (6.0%, p = .030). Median time to initiation of TEAMV by mITT and PP analyses from initiation of PC transfusion support to requirement for TEAMV was >30 days (Data Supplement Figure S2). PRPC patients had a longer interval to TEAMV after initiation of study transfusions, but not significantly different (p = .076).

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative incidence of TEAMV for conventional PC and PRPC. HR and 95% CIs were estimated from Cox proportional hazards regression. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.4. Secondary outcomes

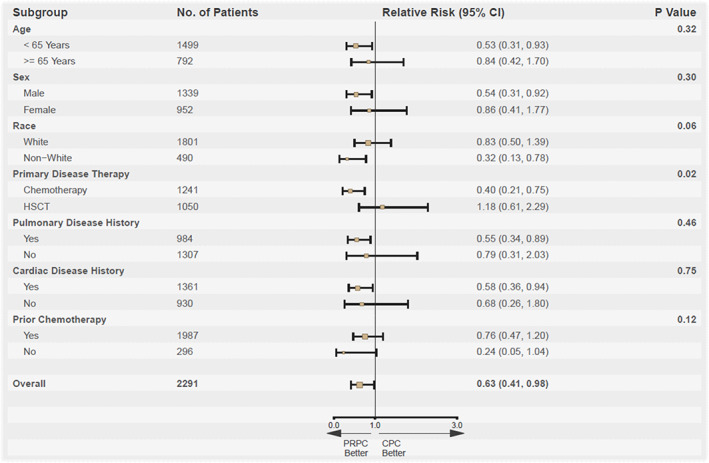

Clinical data for patients with TEAMV (n = 93) were submitted to the PEP to determine the incidence of TEAMV initiated for pulmonary dysfunction (TEAMV‐PD) and TEARDS. The subset of patients with TEAMV‐PD had substantial PC exposure (Table 3). For the mITT population, the incidence of TEAMV‐PD for PRPC by the PEP was less compared with CPC (treatment difference = −1.5%, 95% CI: (−2.7%, −0.2%). For the 56 mITT patients with TEAMV‐PD, 33 (11 PRPC and 22 CPC) met the criteria for ARDS. The incidence of adjudicated ARDS for PRPC was not statistically different (1.0% vs. 1.8%, p = .151; odds ratio = 0.57, 95% CI: (0.27, 1.18). No PRPC patient had ARDS related to PC transfusion, and one CPC case of ARDS was adjudicated as related to PC. One CPC patient met the definition for TRALI. PEP assessment of ARDS for the PP analysis was consistent with the mITT analysis (p = .132) (Table 3). Days from first PC exposure to initiation of TEAMV in patients with TEAMV‐PD by the least‐squares mean from first PC exposure to initiation to TEAMV were longer for PRPC (10.7) versus CPC (6.0). The PP analysis for time of first PC exposure to TEAMV‐PD was consistent with the mITT analysis (Table 3). The relative risk of TEAMV by baseline subgroup covariates was less for PRPC recipients with the following: age <65 years, male sex, non‐white race, primary therapy of chemotherapy without HCT, history of pulmonary disease, and history of cardiac disease (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The relative risk of TEAMV for recipients of PRPC compared with conventional PC. Risk of TEAMV was reduced for recipients of PRPC <65 years of age, male sex, non‐white race, primary therapy with chemotherapy without HCT, history of pulmonary disease, and history of cardiac disease. p‐values were based on the Breslow–day test for homogeneous odds ratios across subgroups [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Treatment‐emergent respiratory therapy (Table 4) was required for 17.7% of PRPC and 21.3% of CPC patients in the mITT data set (p = .064). By PP analysis, less respiratory therapy was received by PRPC patients (p = .016). The incidence of treatment‐emergent CSPAE was not different between PRPC and CPC and was similar for the mITT and PP analyses (Table 4). An exploratory multivariate analysis (mITT) for the probability of CSPAE or transfusion‐associated circulatory overload (TACO) showed PC type had no effect. The odds ratio (OR) of CSPAE or TACO during PC support was significantly increased in both cohorts for patients with a baseline history of cardiac disease (OR = 1.35, p = .028), pulmonary disease (OR = 2.57, p < .001), and for patients with a diagnosis of myelodysplasia (OR = 1.88, p = .006), and myelodysplasia/myeloproliferative disease (OR = 2.27, p = .026). There was a significant treatment interaction (p = .043) between PC type and acute myelogenous leukemia with an increased risk of CSPAE and TACO for patients supported with CPC (OR = 1.49).

TABLE 4.

Respiratory therapy, incidence of clinically significant pulmonary adverse events and platelet component exposure

| Modified intention‐to‐treat analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory therapy | |||

| Parameter | PRPC n = 1068 | CPC n = 1223 | PRPC versus CPC a |

| Patients with treatment‐emergent respiratory therapy of any type: n (%) | 189 (17.7) | 260 (21.3) | 0.064 |

| Intubation | 13 (1.2) | 40 (3.3) | |

| Tight‐fitting mask | 25 (2.3) | 30 (2.5) | |

| Loose‐fitting mask | 29 (2.7) | 47 (3.8) | |

| Nasal oxygen | 179 (16.8) | 240 (19.6) | |

| High‐flow oxygen or EzPAP | 14 (1.3) | 32 (2.6) | |

| No respiratory therapy required | 879 (82.3) | 963 (78.7) | |

| Clinically significant pulmonary adverse events | |||

| Patients with clinically significant pulmonary adverse events (CSPAE): n (%) b | 151 (14.1) | 180 (14.7) | 0.810 |

| Patients with Serious CSPAE: n (%) c | 67 (6.3) | 85 (7.0) | 0.705 |

| PC exposure in patients with CSPAE (n ± SD) d | 9.8 ± 10.0 | 9.9 ± 7.9 | 0.746 |

| Days of PC support in patients with CSPAE (n ± SD) e | 11.0 ± 7.3 | 12.8 ± 7.5 | 0.029* |

| per protocol analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory therapy | |||

| Parameter | PRPC n = 1002 | CPC n = 1036 | PRPC versus CPC a |

| Patients with treatment‐emergent respiratory therapy of any type: n (%) | 166 (16.6) | 218 (21.0) | 0.016* |

| Intubation | 11(1.1) | 30 (2.9) | |

| Tight‐fitting mask | 21 (2.1) | 20 (1.9) | |

| Loose‐fitting mask | 28 (2.8) | 42 (4.1) | |

| Nasal oxygen | 156 (15.6) | 202 (19.5) | |

| High‐flow oxygen or EzPAP | 12 (1.2) | 21(2.0) | |

| No respiratory therapy required | 836 (83.4) | 818 (79.0) | |

| Clinically significant pulmonary adverse events | |||

| Patients with CSPAEs: n (%) b | 135 (13.5) | 146 (14.1) | 0.795 |

| Patients with serious CSPAE: n (%) c | 59 (5.9) | 64 (6.2) | 0.889 |

| PC exposure in patients with CSPAE (n ± SD) d | 9.7 ± 10.3 | 10.2 ± 8.2 | 0.649 |

| Days of PC support in patients with CSPAE (n ± SD) e | 10.6 ± 7.2 | 12.8 ± 7.5 | 0.015* |

p‐values are based on a stratified CMH PRPC (General Association), controlling for four‐category primary disease therapy (Chemotherapy, HCT‐Myelo, HCT‐Non‐Myelo, and HCT‐RIC). A p‐value <.050 is flagged with an asterisk (*).

Clinically significant pulmonary adverse events (CSPAEs) are adverse events ≥ CTCAE Grade 2. CSPAEs are treatment‐emergent AEs, defined as AEs with an onset on or after the start of the first study‐platelet transfusion. By default, AEs with missing onset date are treatment emergent. AEs with missing relationship/severity/seriousness are categorized as related/severe/serious AEs. MedDRA version 18.0 is used.

Serious CSPAE are those events that meet the criteria for Serious (death, life‐threatening event, inpatient hospitalization, persistent or significant disability/incapacitation, congenital anomaly/birth defect, or another significant medical event).

The number of PC transfused during the active transfusion period of up to 21 days after enrollment.

Days of platelet support period = (date of last study or non‐study platelet transfusion, up to Day 21 or platelet independence, whichever sooner)−(date of first study transfusion) + 1, where platelet independence is defined as more than 5 days elapsed from the previous study or non‐study platelet transfusion.

Peri‐transfusion AE (58.9 vs. 57.8%, p = .909), SAE (25.9 vs. 23.2%, p = .219), and mortality (2.5 vs. 2.4%, p = .469) were not different between cohorts for the mITT analyses (Data Supplement, Table S3). There were no differences in AEs related to study PC. No TR were fatal in either cohort. Allergic TR were significantly lower in the PRPC cohort by mITT (3.0% vs. 5.6%, p = .006). Febrile non‐hemolytic TR were marginally different in the mITT data analysis, but not the PP data analysis (Data Supplement, Table S3). The incidence of TACO and transfusion‐associated dyspnea were not different between cohorts. A single case of TRALI was reported for one Control patient. Four CPC patients had an AE reported by the investigator as possible transfusion‐transmitted bacterial infection compared with none reported in the PRPC cohort. However, none of these cases was confirmed because concurrent culture of PC and the patients were not performed.

3.5. Hemostatic efficacy

The incidence of hemorrhagic AEs was approximately 10% in each cohort by either mITT or PP analyses and not different (Data Supplement, Table S3). Red cell transfusion, a surrogate indicator of severe hemorrhage, was required by approximately 59% of patients in each cohort (Table 2). The numbers of red blood cell (RBC) components per patient were not significantly different between the cohorts for the mITT data set, and significantly less for the PP analysis (Table 2). PC utilization and days of support, indicators of PC transfusion efficacy, were not significantly different by PP analysis (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

PRPC are designed to reduce the risk of TTI without excess treatment related morbidity 8 including TRALI, ARDS, and other pulmonary injuries. 5 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 Platelets have been postulated to play a role in the pathophysiology of TRALI. 13 , 14 As a condition of PRPC licensure, FDA mandated a post marketing clinical surveillance study to evaluate the impact of PRPC on pulmonary injury. This is pertinent to the FDA Guidance on Bacteria Risk Control. 15

TEAMV was the primary outcome in this study as an indicator of significant pulmonary dysfunction. It served as an indicator to identify patients at risk for ARDS who were adjudicated by the PEP using specific criteria. 7 The PEP also determined the incidence of TEAMV implemented for CSPAE. These outcomes provide an integrated assessment of pulmonary injury in patients with disease and therapy related co‐morbidities that could potentiate pulmonary injury. Collection of all peri‐transfusion AE and SAE provided additional information regarding safety. The use of PC, RBC, and the incidence of hemorrhagic AEs were used to assess hemostatic efficacy to supplement data from prior randomized controlled and observational studies. 2 , 3 , 16 , 17 , 18

The cumulative incidence of TEAMV was significantly less for PRPC recipients despite larger proportions with prior history of cardiac and pulmonary disease. The incidence of TEARDS was low; and not increased by exposure to PRPC. For each of the TEARDS patients, there were concurrent clinical factors determined by the PEP resulting in TEAMV not attributed to PC suspension media, and only a single case of TRALI in the CPC cohort. In addition, the proportions of patients with CSPAE were not different between the PRPC and CPC cohorts suggesting that differences in PC suspension media (plasma vs. plasma‐PAS) did not play a significant role in TEAMV. The similar incidence of CSPAE to that of the prior Phase 3 clinical trial suggests that the methods for detection of pulmonary dysfunction in this surveillance study were sensitive. 2 , 4 Despite an increased proportion of PRPC recipients with a baseline history of prior pulmonary disease the PRPC cohort required less respiratory therapy while on study. Subgroup analysis of baseline factors for the relative risk of TEAMV during PC transfusion indicated that the risk of TEAMV was less for PRPC patients with multiple baseline risk factors (Figure 3).

In contrast to the earlier Phase 3 study 2 and a subsequent Phase 4 hemostasis study, 16 the current study utilized hemorrhagic AE and RBC transfusion as surrogate indicators of hemostasis because daily clinical hemostatic assessments were infeasible during routine practice. For the PP analysis of 1002 PRPC patients, there was no increased utilization of PRPC, of RBC components, or increased incidence of hemorrhagic AE compared with 1036 CPC recipients. These observations are consistent with other observations. 2 , 16 Amotosalen‐UVA treated PC have been in widespread use in several European countries for more than 10 years with demonstrated safety and efficacy; 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 and recent studies have confirmed safety for pediatric patients. 17 , 23 However, we note that Amotosalen‐UVA dos not inactivate all pathogens, notably spores and some non‐enveloped viruses such as hepatitis E virus. 24

The major limitation of our study was the open label non‐randomized design. Although there was no randomization for type of primary therapy, the use of four therapy strata to match cohorts within sites provided reasonable balance between the cohorts. The sequential cohort design within each clinical site facilitated the conduct of a large study to determine the incidence of infrequent events such as ARDS. Moreover, the primary outcome used an objective parameter—TEAMV; and a blinded PEP, to avoid bias.

The data from this study indicate that PRPC do not exhibit excess treatment related morbidity and offer an effective means for a bacterial risk control strategy. PR provides a proactive measure during emerging pathogen epidemics 25 , 26 , 27 when transfusion transmission risk is uncertain and when blood donor testing for an emerging pathogen may be limited. Replacement of bacteria culture screening, and gamma irradiation can offset the cost impact of PR.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Edward L. Snyder, Allison P Wheeler, Majed Refaai, Claudia S. Cohn, Jessica Poisson, Magali Fontaine, Mary Sehl, Ajay K. Nooka, Lynne Uhl, Philip Spinella, Maly Fenelus, Darla Liles, Thomas Coyle, Joanne Becker, Michael Jeng, Eric A. Gehrie, Bryan R. Spencer, Pampee Young, Andrew Johnson, Jennifer J. O'Brien, Gary J. Schiller, John D. Roback, Elizabeth Malynn, Ronald Jackups, and Scott T. Avecilla have no personal conflicts of interest. They served as study investigators and were compensated through their respective institutional research contracts with Cerus Corporation. Jin‐Sying Lin, Kathy Liu, Stanley Bentow, and Ho‐Lan Peng are employees of Cerus Corporation, the study sponsor, and received compensation and equity options as part of their employment. Jeanne Varrone, Richard J. Benjamin, and Laurence M. Corash are employees of Cerus Corporation, the study sponsor, and received compensation and equity options as part of their employment.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the substantial contribution to the study by the pulmonary expert panel: Chairman, Ednan Bajwa, MD, MPH, Roy Brower, MD, Todd Rice, MD, MSc, and Boyd Taylor Thompson, MD. Staff at the study site blood centers provided study platelet components to enable the study. Therese Chlebeck provided additional support for the study at the University of Minnesota.

Snyder EL, Wheeler AP, Refaai M, Cohn CS, Poisson J, Fontaine M, et al. Comparative risk of pulmonary adverse events with transfusion of pathogen reduced and conventional platelet components. Transfusion. 2022;62(7):1365–1376. 10.1111/trf.16987

Funding information Cerus Corporation

REFERENCES

- 1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration . Bacterial risk control strategies for blood collection establishments and transfusion services to enhance the safety and availability of platelets for transfusion: draft guidance for industry. Center for biologics evaluation and research. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McCullough J, Vesole DH, Benjamin RJ, Slichter SJ, Pineda A, Snyder E, et al. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of platelets treated with a photochemical process for pathogen inactivation: the SPRINT trial. Blood. 2004;104:1534–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Snyder E, McCullough J, Slichter SJ, Strauss RG, Lopez‐Plaza I, Lin JS, et al. Clinical safety of platelets photochemically treated with amotosalen HCl and ultraviolet a light for pathogen inactivation: the SPRINT trial. Transfusion. 2005;45:1864–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corash L, Lin JS, Sherman CD, Eiden J. Determination of acute lung injury after repeated platelet transfusions. Blood. 2011;117:1014–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Giralt S, Lazarus H, Ho V, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1628–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. ARDS Definition Task Force . Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Snyder EL, Stramer SL, Benjamin RJ. The safety of the blood supply — time to raise the Bar. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1882–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Looney MR, Nguyen JX, Hu Y, Van Ziffle JA, Lowell CA, Matthay MA. Platelet depletion and aspirin treatment protect mice in a two‐event model of transfusion‐related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3450–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gelderman MP, Chi X, Zhi L, Vostal JG. Ultraviolet B light‐exposed human platelets mediate acute lung injury in a two‐event mouse model of transfusion. Transfusion. 2011;51:2343–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jia X, Malhotra A, Saeed M, Mark RG, Talmor D. Risk factors for ARDS in patients receiving mechanical ventilation for > 48 h. Chest. 2008;133:853–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Serpa Neto A, Juffermans NP, Hemmes SNT, et al. Interaction between peri‐operative blood transfusion, tidal volume, airway pressure and postoperative ARDS: an individual patient data meta‐analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caudrillier A, Kessenbrock K, Gilliss BM, Nguyen JX, Marques MB, Monestier M, et al. Platelets induce neutrophil extracellular traps in transfusion‐related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2661–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caudrillier A, Mallavia B, Rouse L, Marschner S, Looney MR. Transfusion of human platelets treated with Mirasol pathogen reduction technology does not induce acute lung injury in mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Bacterial risk control strategies for blood collection establishments and transfusion services to enhance the safety and availability of platelets for transfusion – guidance for industry. Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garban F, Guyard A, Labussiere H, et al. Comparison of the hemostatic efficacy of pathogen‐reduced platelets vs untreated platelets in patients with thrombocytopenia and malignant hematologic diseases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:468–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schulz WL, McPadden J, Gehrie EA, Bahar B, Gokhale A, Ross R, et al. Blood utilization and transfusion reactions in pediatric patients transfused with conventional or pathogen reduced platelets. J Pediatr. 2019;209:220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bahar B, Schulz WL, Gokhale A, Spencer BR, Gehrie EA, Snyder EL. Blood utilisation and transfusion reactions in adult patients transfused with conventional or pathogen‐reduced platelets. Br J Haematol. 2020;188:465–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jutzi MP, Ruesch M, Mansouri‐Taleghani B. Comparison of Swiss haemovigilance data for pathogen inactivated and conventional platelet components. Transfusion. 2012;52:48A.21790626 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corash L, Benjamin RJ. The role of hemovigilance and postmarketing studies when introducing innovation into transfusion medicine practice: the amotosalen‐ultraviolet a pathogen reduction treatment model. Transfusion. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mertes PM, Tacquard C, Andreu G, Kientz D, Gross S, Malard L, et al. Hypersensitivity transfusion reactions to platelet concentrate: a retrospective analysis of the French hemovigilance network. Transfusion. 2020;60:507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agence Nationale de Securite du Medicament (ANSM) . 18eme Rapport National D'Hemovigilance. Direction Medicale Medicaments. Saint‐Denis, France: ANSM; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lasky B, Nolasco J, Graff J, Ward DC, Ziman A, McGonigle AM. Pathogen‐reduced platelets in pediatric and neonatal patients: demographics, transfusion rates, and transfusion reactions. Transfusion. 2021;61:2869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hauser L, Roque‐Afonso AM, Beyloune A, et al. Hepatitis E transmission by transfusion of Intercept blood system‐treated plasma (letter). Blood. 2013;123:796–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pinna D, Sampson‐Johannes A, Clementi M, Poli G, Rossini S, Lin L, et al. Amotosalen photochemical inactivation of severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus (SARS‐CoV) in human platelet concentrates. Transfus Med. 2005;15:269–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hashem AM, Hassan AM, Tolah AM, Alsaadi MA, Abunada Q, Damanhouri GA, et al. Amotosalen and ultraviolet a light efficiently inactivate MERS‐coronavirus in human platelet concentrates. Transfus Med. 2019;29:434–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Azhar EI, Hindawi SI, El‐Kafrawy SA, Hassan AM, Tolah AM, Alandijany TA, et al. Amotosalen and ultraviolet a light treatment efficiently inactivates severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) in human plasma. Vox Sang. 2020;116:673–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Supporting Information