Abstract

Mental health inpatient units are complex and challenging environments for care and treatment. Two imperatives in these settings are to minimize restrictive practices such as seclusion and restraint and to provide recovery‐oriented care. Safewards is a model and a set of ten interventions aiming to improve safety by understanding the relationship between conflict and containment as a means of reducing restrictive practices. To date, the research into Safewards has largely focused on its impact on measures of restrictive practices with limited exploration of consumer perspectives. There is a need to review the current knowledge and understanding around Safewards and its impact on consumer safety. This paper describes a mixed‐methods integrative literature review of Safewards within inpatient and forensic mental health units. The aim of this review was to synthesize the current knowledge and understanding about Safewards in terms of its implementation, acceptability, effectiveness and how it meets the needs of consumers. A systematic database search using Medline, CINAHL, Embase and PsychInfo databases was followed by screening and data extraction of findings from 19 articles. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the quality of empirical articles, and the Johanna Brigg’s Institute (JBI’s) Narrative, Opinion, Text‐Assessment and Review Instrument (NOTARI) was used to undertake a critical appraisal of discussion articles. A constant comparative approach was taken to analysing the data and six key categories were identified: training, implementation strategy, staff acceptability, fidelity, effectiveness and consumer perspectives. The success of implementing Safewards was variously determined by a measured reduction of restrictive practices and conflict events, high fidelity and staff acceptability. The results highlighted that Safewards can be effective in reducing containment and conflict within inpatient mental health and forensic mental health units, although this outcome varied across the literature. This review also revealed the limitations of fidelity measures and the importance of involving staff in the implementation. A major gap in the literature to date is the lack of consumer perspectives on the Safewards model, with only two papers to date focusing on the consumers point of view. This is an important area that requires more research to align the Safewards model with the consumer experience and improved recovery orientation.

Keywords: consumers, mental health nursing, recovery, safety, Safewards

Introduction

Maintaining a safe environment for consumers and staff has been an important consideration for inpatient mental health units for some time (Bowers et al. 2014; Cutler et al. 2020; Duxbury et al. 2019). In an attempt to ensure safety, coercive measures such as seclusion or restraint, also known as restrictive practices or containment measures, are commonly used throughout the world (Tingleff et al. 2017). Restrictive practices are however problematic because of the significant adverse impacts on consumers to both physical and mental health (Tingleff et al. 2017), and they can lead to further consumer distress, conflict and traumatization (Bowers 2014; Cutcliffe et al. 2015; Kennedy et al. 2019).

Subsequently, the importance of reducing restrictive practices such as seclusion and restraint is well recognized (Muir‐Cochrane et al. 2018; Wilson et al. 2018) and best achieved by using multifaceted models that consider a range of individual and organizational factors (Duxbury et al. 2019; Fletcher et al. 2019b). Safewards is a model and set of interventions recognized as a strategy not only for reducing restrictive practices (Bowers et al. 2015; Fletcher et al. 2017) but also for facilitating staff–consumer engagement and improving the level of safety within inpatient mental health units (Fletcher et al. 2019b). A recognition that Safewards could reduce restrictive practices was demonstrated in the original cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Bowers et al. 2015). This led to an increased level of interest in the model internationally (Baumgardt et al. 2019; Dickens et al. 2020; Kipping et al. 2019). Despite this increased level of interest, at the time of undertaking this review a database search found no reviews of the literature on Safewards to date. This paper presents an integrative literature review of Safewards within inpatient mental health and forensic units.

Background

Safewards is a model and a set of ten interventions that aims to improve safety through preventing conflict and containment (Bowers 2014). The explanatory model behind Safewards consists of six originating domains: Staff Team, Patient Community, Patient Characteristics, Outside Hospital, Regulatory Framework and Physical Environment (Bowers et al. 2014). These domains recognize a range of contributing factors around unit safety. These include the importance of how staff work together and how staff interpret the unit structure (Staff Team), that interactions between consumers are a significant part of safety (Patient Community) and that individual consumer characteristics have the potential to contribute to conflict within the unit (Patient Characteristics) (Bowers et al. 2014). The domains also recognize the impact of personal matters taking place in the consumers life outside the unit (Outside Hospital), the responsibilities connected with legal parameters and restrictions (Regulatory Framework), as well as the layout and design of the unit and how this can influence levels of conflict (Physical Environment) (Bowers et al. 2014). The model also has a set of 10 discrete interventions that seek to improve safety and reduce the use of restrictive practices by identifying and targeting the sources of conflict (Bowers 2014). A brief explanation of each intervention is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Safewards interventions

| Intervention | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Mutual Help Meeting | Patients offer and receive mutual help and support through a daily, shared meeting | Strengthens patient community, opportunity to give and receive help |

| Know Each Other | Patients and staff share some personal interests and ideas with each other, displayed in unit common areas | Builds rapport, connection and sense of common humanity |

| Clear Mutual Expectations | Patients and staff work together to create mutually agreed aspirations that apply to both groups equally | Counters some power imbalances, creates a stronger sense of shared community |

| Calm Down Methods | Staff support patients to draw on their strengths and use/learn coping skills before the use of PRN medication or containment | Strengthen patient confidence and skills to cope with distress |

| Discharge Messages | Before discharge, patients leave messages of hope for other patients on a display in the unit | Strengthens patient community, generates hope |

| Soft Words | Staff take great care with their tone and use of collaborative language. Staff reduce the limits faced by patients, create flexible options and use respect if limit setting is unavoidable | Reduces a common flashpoint. Builds respect, choice and dignity. |

| Talk Down | De‐escalation process focuses on clarifying issues and finding solutions together. Staff maintain self‐control, respect and empathy | Increases respect, collaboration and mutually positive outcomes |

| Positive Words | Staff say something positive in handover about each patient. Staff use psychological explanations to describe challenging actions | Increases positive appreciation and helpful information for colleagues to work with patients |

| Bad News Mitigation | Staff understand, proactively plan for and mitigate the effects of bad news received by patients | Reduces impact of common flashpoints, offers extra support |

| Reassurance | Staff touch base with every patient after every conflict on the unit and debrief as required. | Reduces a common flashpoint, increases patients’ sense of safety and security |

From: Fletcher et al. (2019b) page 3.

Safewards has been used primarily to reduce the use of restrictive practices within inpatient settings (Bowers et al. 2015; Fletcher et al. 2017) by addressing the incidence and escalation of conflict events (Dickens et al. 2020) and breaking the vicious cycle between conflict and coercion (Bowers 2014; Fletcher et al. 2019b). There is also however an imperative for any model to be responsive to consumer involvement (Cutcliffe et al. 2015; Olasoji et al. 2018) and to utilize recovery‐oriented and consumer‐focused practices (Lim et al. 2019; McKenna et al. 2014; McLoughlin et al. 2013; Santangelo et al. 2018).

The uptake of Safewards since the initial trial (Bowers et al. 2015) is widespread, yet many implementation programs may not be informed by learnings pooled from diverse international studies since that time. Furthermore, as consumer‐focused and recovery‐oriented service delivery is essential in supporting individualized outcomes, Safewards needs to align with this imperative. Therefore, it is important to synthesize the current knowledge and understanding of Safewards in determining how it can best inform mental health nursing practice and guide future research to best meet the therapeutic needs and safety of mental health consumers.

Aims

The aim of this mixed‐methods integrative literature review, therefore, is to synthesize the current knowledge and understanding about the implementation, effectiveness, acceptability of Safewards and how it meets the needs of consumers within inpatient and forensic mental health units.

The specific questions that this literature review is seeking to answer are as follows:

What are the current perspectives from mental health nurses about adopting and implementing the Safewards model and its ten interventions?

What is the current evidence around the effectiveness of Safewards?

How do consumers report their experience the Safewards model and ten interventions?

Methods

An integrative literature review method was chosen to capture a broad range of publications with varied methodological approaches including empirical, experiential and discussion‐based papers (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). This approach suits the topic of interest and provides the most comprehensive perspective of the emerging Safewards literature.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included articles comprised peer‐reviewed qualitative and quantitative studies, as well as discussion papers. Articles needed to address the central topic of the Safewards model of care within adult inpatient mental health or forensic mental health units. Inclusion was limited to English language papers from the 1st of January 2014 as 2014 is the date of the very first published article on Safewards to the 31st of December 2020. Including papers published in other languages was beyond the capability of the team. The eligibility criteria are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria

|

Peer‐reviewed articles Address the topic of Safewards Adult inpatient mental health or forensic mental health settings English language articles Articles published between 1st of January 2014 and the 31st of December 2020 |

Search strategy/data sources

This integrative review included all peer‐reviewed articles reported on the Safewards model in relation to adult inpatient mental health and forensic mental health units. These parameters were chosen to compare the literature based on mainly homogenous settings, rather than divergent applications of Safewards. Articles included research, theoretical or discussion‐based papers, using the databases Medline, CINAHL, Embase and PsychInfo to conduct the literature search.

The PICO framework was used to guide the research question, inclusion and exclusion criteria and the search terms. PICO stands for Patient/problem (MH inpatient settings), Intervention (Safewards), Comparison (not applicable) and Outcome (Implementation: Staff acceptability, Effectiveness: Reducing conflict and containment, and Consumer experiences of care) (Schardt et al. 2007).

The Johanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for conducting reviews were used to guide the search strategy (Pearson et al. 2014). The first of three steps was to conduct a limited search of the literature on Safewards using Medline and CINAHL databases. The term ‘Safewards’ was entered into these two databases. The titles and abstracts of the articles from this initial search were scanned, and the index terms used for each article were also analysed. This initial search also identified three broad subject headings used to guide the final database search strategy. The second search used the identified key terms and index terms from each article within four databases: Medline, Embase, PsychInfo and CINAHL. Search terms were adjusted to suit each database. Table 3 outlines the search terms used for the Medline database provided as an example. This resulted in a total of 194 articles. 67 duplicates were identified and removed, leaving 127 articles. Titles of articles from this search across the four databases were screened by the lead author for relevance and inclusion according to the criteria, and a further 81 articles were subsequently excluded. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 46 articles were further screened independently by two authors against the criteria with another 29 excluded to produce 17 articles that met the inclusion criteria. The third and final stages involved the lead author scanning the full‐text articles and reference lists of all identified articles for further relevant articles of which a further two were identified resulting in a total of 19 articles.

Table 3.

Included search terms—Medline database

| Concepts | Search Terms | |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | Hospitals, Psychiatric | |

| Psychiatric Department, Hospital | ||

| Mental Health Service | ||

| Mental Health | ||

| AND | Psychiatric | OR |

| Locked | ||

| Acute | ||

| Ward | ||

| Inpatients | ||

| Practice | Conflict, Psychological | |

| Aggression | ||

| Coercion | ||

| Restraint, Physical | ||

| AND | Patient Isolation | OR |

| Patient Safety | ||

| Prevent | ||

| Mitigate | ||

| Seclusion | ||

| Isolation | ||

| Safewards Model | Safeward* | |

| Models, Nursing | ||

| Models, Theoretical | OR | |

| Models, Organizational |

Boolean methods used (AND/OR).

Selection of papers

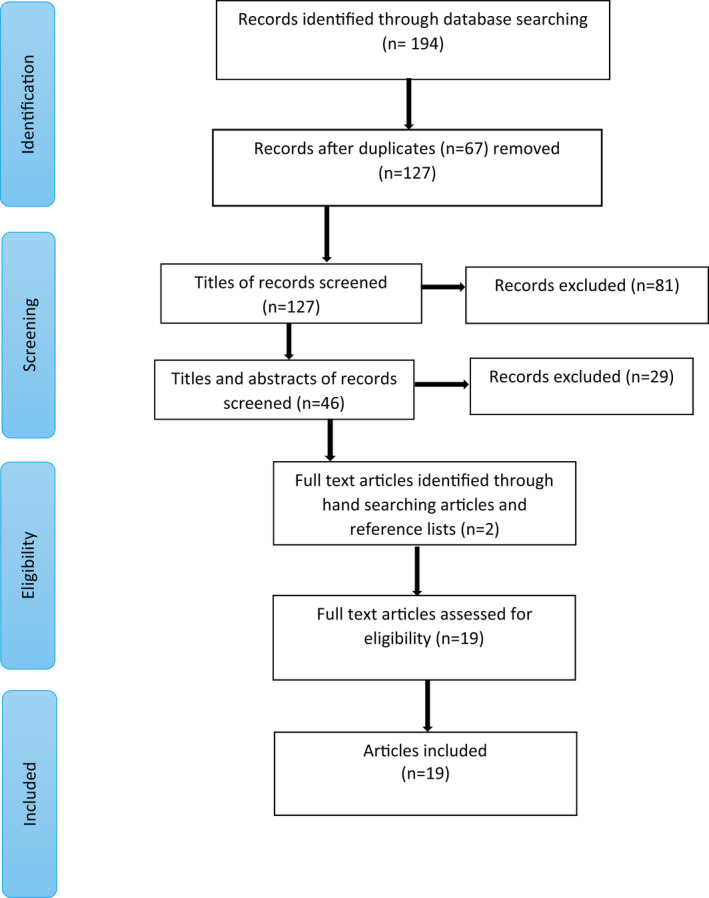

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) Flowchart is used to display the search and screening process of papers for inclusion as illustrated in Fig. 1 (Moher et al. 2009). Each of the 19 papers resulting from the three‐stage database search underwent a full‐text screen independently by two authors to confirm they met the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of search, screening and inclusion of papers.

Data analysis and extraction

Data extraction followed the recommended approach for integrative reviews, and a data extraction process reflecting the research questions was specifically devised for this purpose (Sandelowski et al. 2013; Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Table 4 presents the summary of findings for each of the included articles.

Table 4.

Summary of included papers

| Article & Country | Study design | Study aims | Setting and participants | Data collection methods | Results/Findings | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bowers (2014) UK |

Discussion | Proposes a model to explain the relationship between conflict and containment in inpatient mental health units | N/A | N/A |

Conflict and containment linked to staff violence and harmful consumer events The Safewards model comprises of 6 originating domains that can guide staff in reducing levels of conflict and containment through the use of 10 distinct interventions |

86% |

|

Bowers et al. (2014) UK |

Discussion | Describes the empirical basis behind the Safewards model of care | N/A | N/A |

Provides a description of the theory behind the Safewards model through a critique of the 6 originating domains that make up the model The model is considered to be speculative without a strong evidence base. Based on previous reviews and research into conflict and containment and reasoned thinking |

86% |

|

Bowers et al. (2015) UK |

Randomized cluster controlled trial implementing Safewards over 8 weeks with 8 weeks continuation | Tests the efficacy of the interventions within the Safewards model | Staff and consumers in 31 inpatient mental health units in the UK |

1. Rates of conflict and containment checklist (PCC) 2. Ward atmosphere scale (WAS) 3. Attitude to personality disorder questionnaire (APDQ) 4. Self harm antipathy scale (SHAS) 5. Short form health survey (SF‐36‐V2) 6. Safewards fidelity checklist |

The rates of conflict events reduced by 15% in the intervention group relative to the control The rate of containment events for the intervention group reduced by 26.4%. No differences were found for the WAS, APDQ or SHAS The SF‐36‐V2 showed some difference in physical health fir experimental group Mean fidelity via the fidelity checklist was 36% Staff rated fidelity post implementation was 89% |

**** |

|

Price et al. (2016) UK |

Mixed‐methods service evaluation | Evaluates the effectiveness of the Safewards model over 10 weeks | Staff and consumers in 6 forensic units in the UK comprising of 3 control units and 3 intervention units |

1. Patient–staff conflict checklist (PCC‐SR) collected for 2 weeks prior to implementation 2. Safewards fidelity checklist 3. Data analysis between and within the six participating units 4. Informal staff feedback session |

A 71% return rate of PCC‐SR checklist No statistically significant benefits for both the between and within group analysis Fidelity result: 27.2% Inconsistent implementation Varying acceptability of Safewards among staff Staff critical of implementation process Staff attitudinal barriers observed |

** |

|

Cabral and Carthy (2017) UK |

Mixed‐methodsservice evaluation | Evaluates a 6 month implementation of Safewards and its impact on a forensic service | 89 patients and 102 staff across 6 forensic wards in the UK |

1. Essen climate scale (Forensic measure) 2. Safewards implementation audit checklist 2. Focus groups for implementation leaders 3. Developing recovery‐enhancing environments measure (DREEM) 4. Ward community meetings between patients and staff |

Safewards found to minimize restrictive practices Three themes: 1. Benefits experienced 2. Resistance 3. Knowledge and skills: Essen Ward climate scale showed improved patient cohesion, therapeutic hold and experience of safety Positive results from the DREEM measure High degree of implementation |

** |

|

Fletcher et al. (2017) Australia |

Quantitative before and after with comparison group study design | Compare the rates of seclusion between trial sites and comparison sites after a 12‐week trial of Safewards | 44 mental health units across Victoria with 31 controls and 13 intervention units who ‘opted in’ |

1. Seclusion rates per 1000 occupied bed days 2. Fidelity checklist Two trial collection points, one post‐ and one follow‐up |

Seclusion rates reduced by 36% at 12 months of follow‐up | ***** |

|

Maguire et al. (2018) Australia |

Quantitative evaluation of Safewards implementation | Measure impact of Safewards on conflict and containment events and fidelity of Safewards implementation | The staff and patients of a 20‐bed forensic unit in Victoria |

1. Essen Climate scale for ward atmosphere 2. Fidelity checklist which included direct feedback from staff 3. Seclusion and restraint events via an incident management system |

65 fewer conflict events in the year Containment events did not change Fidelity averaged 94.75% Three themes 1. Positive changes in language and communication 2. Enhanced safety 3. Respectful relationships Ward climate showed improved patient cohesion and experience of safety Safewards helpful for responding to verbal aggression |

*** |

|

Stensgaard et al. (2018) Denmark |

Quantitative retrospective before and after study | Does the implementation of Safewards reduce coercive measures? | Staff and consumers of adult psychiatric inpatient units in Southern region of Denmark | Register of coercive measures including episodes of restraint and forced sedation |

No change in episodes of restraint Forced sedation was reducing by 8% after implementation |

**** |

|

Higgins et al. (2018) Australia |

Qualitative phenomenological study using Michie’s framework for behavioural change | Staff perceptions of Safewards 12 months postimplementation | 15 staff from 3 acute mental health inpatient units in South‐east Queensland | Semi‐structured staff interviews |

Implementation challenges Variable staff acceptance and engagement Need to adopt training materials to fit local context Maintaining fidelity difficult Peer influence among staff Variable management support |

**** |

|

Baumgardt et al. (2019) Germany |

Quantitative before and after implementation study | To evaluate the 10‐month implementation of Safewards and its impact on coercive interventions | Staff and consumers of 2 locked psychiatric wards in Germany | Rates of coercive interventions including mechanical restraint, forced medication and limitation of freedom of movement | Rates of coercive interventions reduced following implementation High fidelity in both wards | **** |

|

Kennedy et al. (2019) Australia |

Discursive paper | Critique the Safewards model from the lived experience perspective | N/A | N/A |

Identified that the role of trauma, power differential and the legitimization of state power still need addressing in the Safewards model. The role of hospital as a sanctuary and the concepts of ‘sanctuary trauma and ‘sanctuary harm’ are discussed. Consumer experience of safety needs to be considered Expansions to the model are proposed |

86% |

|

Fletcher et al. (2019a) Australia |

Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional postintervention survey design | Describe the impact of Safewards on consumer experiences | 72 Consumers from 11 inpatient mental health units in Victoria |

5 quantitative questions 1. Recall of model 2. How worthwhile 3. How frequently they saw or were involved 4. Impact on atmosphere of ward 5. Impact on 4 conflict events Further questions about the consumers involvement in Safewards interventions |

Consumers felt safer and more positive about being on ward, and more connected with staff Six themes 1. Recognition and respect: 2. Sense of community 3. Hope 4. Safety and sense of calm 5. Patronizing language and intention 6. Implementation in practice |

*** |

|

Fletcher et al. (2019b) Australia |

Quantitative descriptive cross‐sectional postintervention survey design | Gain staff perspectives about the implementation of the Safewards model and compare these with consumer perspectives | 103 staff from 14 inpatient mental health units across Victoria | Purpose designed survey investigating acceptability, applicability and impact using quantitative and qualitative questions |

Staff believed Safewards reduced conflict events and felt more positive, safer and more connected with consumers Safewards was seen an acceptable intervention Four Themes: 1. Structured and relevant 2. Conflict prevention and reducing restrictive practices 3. Positive ward culture change 4. Promotes recovery principles Staff perceptions concur with consumers |

*** |

|

Kipping et al. (2019) Canada |

Mixed‐methods effectiveness study | Examine the effectiveness of implementing Safewards over 10 weeks using a co‐creation method | 6 forensic inpatient units in Canada |

Phased in implementation strategy Co‐creation principle Safewards champions help design the implementation strategy Organizational fidelity measure Evaluation feedback tool that measured perceptions of training and co‐creation principles 3 months predata collection period |

92% completed training Co‐creation strategy perceived to be positive by staff and contributed to successful implementation and high engagement from staff High fidelity scores |

** |

|

Lickiewicz et al. (2020) Poland |

Quantitative non randomized study |

Translate Safewards into Polish Measure how effective the implementation of 3 Safewards interventions is in reducing mechanical restraint |

Psychiatric hospital in Poland with 50 beds | The number of restraints were recorded and compared across two 8‐month periods one with Safewards interventions and the other without | A reduction of 24% for restraints used. The number of patients restrained reduced by 34% | *** |

|

Whitmore (2017) Canada |

Discursive paper | Describes the implementation of Safewards in forensic units over a period of 12 months | 2 general and 2 forensic psychiatry units in Canada |

Description of the implementation of Safewards Comparison with previous forensic implementation study Recommendations for future implementation |

Recommendations re role modelling from senior staff Training to include information about factors contributing to conflict and containment |

43% |

|

Dickens et al. (2020) Australia |

Quantitative non‐randomized longitudinal pre‐/post‐test design | Describes the evaluation of Safewards implementation | 16‐week implementation in 8 mental health wards |

Conflict and containment measures The violence prevention climate within the social climate scale Fidelity checklist |

Conflict events reduced by 23% and containment events by 12%. Violence prevention climate ratings did not change Fidelity measured at 73.7% |

***** |

|

James et al. (2017) UK |

Qualitative Observational | Explore the quality of implementation of Safewards during a cluster randomized control trial | 16 mental health wards in England | Participant observational data and qualitative exploratory data |

Wide variation in the delivery of Safewards interventions including differences that were both consistent and inconsistent with fidelity measures A typology tool was developed to assist with fidelity during implementation Systemic, interpersonal, individual and consumer factors were all noted to impact on the variations found |

***** |

|

Fletcher et al. (2020) Australia |

Quantitative descriptive non‐matched pre‐ and post‐survey design |

To evaluate whether staff knowledge, confidence and motivation around implementing Safewards improved following two types of training: ‘1 day plus in‐service’ and ‘in‐service’ To investigate the translation of training into practice |

245 staff from across 18 inpatient mental health units involved in a 12‐week trial of Safewards |

1. Pre and post on line surveys measuring knowledge, confidence and motivation across of 5‐point Likert scale (1 = none; 5 = excellent) 2. Fidelity Checklist |

The average pre training level of knowledge and confidence was considered to be ‘good’ The postsurvey average was ‘very good’ The mean motivation to implement Safewards changed from very good (pre) to excellent (post). Both groups reported satisfaction with the two training methods. The ‘1 day plus in‐service training’ reported higher levels of satisfaction No significant difference in fidelity scores between the two training groups |

*** |

A constant comparative approach was taken to analysing the data identifying patterns across the selected articles (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Categories were grouped together before further comparison was undertaken to code the initial categories identified in the data. An iterative process was used to compare codes resulting in the final categories (Bazeley 2013; Whittemore & Knafl 2005).

Quality assessment

Consistent with an integrative literature review method, a quality assessment of included articles was undertaken (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) is considered suitable for assessing the quality of empirical papers using different methods (Hong et al. 2018).

Empirical papers were rated on the criteria provided by the MMAT, with (*) indicating the article had met one criterion, and (*****) indicating five criterion were met (Hong et al. 2018). The JBI’s Narrative, Opinion, Text, Assessment and Review Instrument (NOTARI) was used to assess the quality of discussion papers (McArthur et al. 2015). A percentage score was used based on seven criteria, with the score reflecting the number of criteria that the paper had met (McArthur et al. 2015).

All papers were independently rated by two authors and differences discussed until agreement was reached. Quality scores and percentages are included in Table 4.

Results

Article descriptions

Nineteen articles were included in this review with ten quantitative studies, and six mixed‐methods studies and three were discussion papers. Eight articles were from Australia (Dickens et al. 2020; Fletcher et al. 2017, 2019a, 2019b, 2020; Higgins et al. 2018; Kennedy et al. 2019; Maguire et al. 2018), six from the United Kingdom (Bowers 2014; Bowers et al. 2014, 2015; Cabral & Carthy 2017; James et al. 2017; Price et al. 2016) two from Canada (Kipping et al. 2019; Whitmore 2017) and one each from Germany (Baumgardt et al. 2019), Denmark (Stensgaard et al. 2018) and Poland (Lickiewicz et al. 2020). Articles reflected diversely sized studies that involved stand‐alone mental health or forensic mental health units to studies involving up to 41 units. Safewards was evaluated using a range of outcome measures including rates of conflict and containment rates, coercive practice, seclusion rates and unit atmosphere. Several studies investigated staff perceptions around the implementation and overall views of the Safewards model, while another presented a consumer’s perspective about the model. Two papers described the rationale and theory behind the model. Further information about the nineteen papers is presented in Table 4.

Categories

Six key categories were identified in the findings of the reviewed studies: training, implementation strategy, staff acceptability, fidelity, effectiveness and consumer perspectives. Three related to the process of implementing Safewards, and three related to outcomes of implementation.

Training

Training was a major focus of six papers and a component reported in three papers. The training approach used in the original Cluster RCT utilized external trainers to train clinical staff (James et al. 2017), which has subsequently been adopted by other studies (Fletcher et al. 2017, 2020). The duration and extent of training provided to front‐line staff varied. In one study, 75% of frontline staff received either a one day of training or several in‐service sessions with similar content up to 1 h in duration (Fletcher et al. 2017, 2020). This study found training was able to improve the knowledge, confidence and motivation for implementing Safewards and emphasized the benefits of training staff as a team (Fletcher et al. 2020). Studies where the majority of staff were trained showed higher levels of implementation and effectiveness (Fletcher et al. 2017, 2020; Maguire et al. 2018) compared to those studies where 50% or less of staff received face to face training (Higgins et al. 2018; Price et al. 2016). This suggests specific Safewards training needs to be provided for the majority of frontline staff for this to translate into successful implementation, demonstrated by higher fidelity scores and reductions in conflict and containment (Bowers et al. 2015; Fletcher et al. 2017).

Implementation strategy

The implementation strategy was the focus of six papers and an element reported in eight papers. Reported duration of implementation varied widely, as did the method or implementation strategies employed. A common approach to implementation was to identify leaders or intervention champions/leads (Bowers et al. 2015; Fletcher et al. 2017). However, there was a need to select staff for those for roles that had sufficient seniority or influence over their colleagues to facilitate change (Higgins et al. 2018). The optimal duration for the implementation of Safewards is unclear as a 12‐week implementation period was successful in terms of fidelity, effectiveness and staff acceptance (Fletcher et al. 2017); however, another study conducted a similar 10‐week implementation period with limited success (Price et al. 2016). Other studies with implementation over longer periods such as 12 months (Maguire et al. 2018) and 10 months (Baumgardt et al. 2019) were still successful. Involving consumers in implementation planning was linked to successful implementation and subsequently staff acceptability (Maguire et al. 2018). By contrast, involving a group of staff from a range of roles within the organization in the planning and implementation of Safewards did not translate into successful implementation (Higgins et al. 2018).

A factor in successful implementation was choice. Successful implementation occurred where leaders and/or staff opted in to local implementation of Safewards (Baumgardt et al. 2019; Fletcher et al. 2017). These two studies in Australia and Germany, respectively, had high‐level executive support, including the heads of a large psychiatric service, nursing directors and the chief psychiatrist or chief mental health nurses driving the implementation (Baumgardt et al. 2019; Fletcher et al. 2017).

Co‐creation principles (i.e. between external team and local staff) where front‐line staff lead the design and implementation were utilized in a Canadian study by Kipping et al. (2019). This study also consulted the relevant industrial body for approval, thus removing one potential obstacle to successful implementation (Kipping et al. 2019). The co‐creation approach was said to enhance staff engagement in the implementation of Safewards, as staff felt listened to and more involved in the process (Kipping et al. 2019).

Fidelity

Fidelity has been measured by a standardized audit tool and used to gauge how well the Safewards interventions are implemented (Bowers et al. 2015; Fletcher et al. 2017). Seven articles used the Safewards fidelity checklist generated for the original study by Bowers et al. (2015) to measure the degree of implementation across the 10 interventions. High fidelity or a high degree of implementation was reported in five of these studies, with scores ranging from a percentage score of between 73.7% and 95% (Baumgardt et al. 2019; Dickens et al. 2020; Fletcher et al. 2017; Kipping et al. 2019; Maguire et al. 2018). Interestingly, the original study used both the independently rated fidelity checklist that returned a relatively low overall score of 38%, as well as a staff questionnaire completed post implementation resulting in a score of 90% (Bowers et al. 2015).

One study reported poor overall fidelity, estimated across the six participating units to be 27%, when measured on a weekly basis throughout a 20‐week period (Price et al. 2016). This poor result was explained by high‐acuity, high staffing demands and poor staff engagement. The timing of fidelity measures also varied greatly and included 4 to 8 months postimplementation (Baumgardt et al. 2019), measures collected 2‐3 times per week during an 8‐week implementation (Bowers et al. 2015), weekly fidelity checks for the first three months postimplementation (Kipping et al. 2019) and four times over a 12‐month implementation period (Maguire et al. 2018). Four fidelity measures over 12 months were undertaken in one paper to assess the longer‐term effects, with an increase reported from the first measure of 48% to the fourth measure of 90% across the units (Fletcher et al. 2017).

Common outcome measures or effectiveness

Outcomes regarding effectiveness including the measure of conflict and containment and the unit atmosphere were the focus of eight of the papers in this review and an element reported in one paper. Four studies reported no or little difference in coercive practices following the implementation of Safewards (Baumgardt et al. 2019; Maguire et al. 2018; Price et al. 2016; Stensgaard et al. 2018). A reduction in coercive practices was reported in four studies, and Lickiewicz et al. (2020) found a 24% reduction in restraint; however, statistical significance could not be determined due to the absence of a p value. Seclusion rates reduced by 36% (P value = 0.040) in the study by Fletcher et al. (2017), and containment rates reduced by 26.4% (P value = 0.004) in the original trial by Bowers et al. (2015), and by 12% (P value = 0.001) in another study by Dickens et al. (2020).

The rate of conflict events reduced in two studies showing statistically significant reductions of 15% (P value = 0.001) (Bowers et al. 2015) and 23% (P value = 0.001) (Dickens et al. 2020). Both studies used the conflict checklist developed in the original Cluster RCT Safewards study (Bowers et al. 2015). Rates of both conflict and containment did not change in another study with poor intervention fidelity being identified as one explanation for this null result (Price et al. 2016).

The Essen Climate Evaluation Schema (EssenCES) was used to evaluate the effectiveness of Safewards in two studies (Cabral & Carthy 2017; Maguire et al. 2018). The EssenCES measures unit atmosphere in terms of how much support consumers provide each other, known as ‘patient cohesion’, the consumer experience of safety and degree of staff–consumer engagement known as ‘therapeutic hold’ (Maguire et al. 2018). One study found that the unit atmosphere improved in terms of ‘patient cohesion’ and ‘experience of safety’ (Maguire et al. 2018), whereas another study showed improvement across all three areas of the scale (Cabral & Carthy 2017). Bowers et al. (2015), on the other hand, found no difference between the control and intervention groups when using the related Ward Atmosphere Scale (WAS).

Staff acceptance

Staff acceptance was a major focus of five papers and an element reported in a further two. Staff acceptability varied across the literature, from staff considered to be well engaged and enthusiastic and highly accepting of Safewards (Fletcher et al. 2017, 2019b; Maguire et al. 2018) to staff that were poorly engaged or where staff acceptance had been problematic (Higgins et al. 2018; Price et al. 2016). High staff acceptance noted largely in the context where motivated staff volunteered to be involved and were specifically targeted to be part of the implementation without seeking specific details around the views of staff about Safewards provided (Baumgardt et al. 2019; Fletcher et al. 2017). An ‘opt‐in’ basis where implementation was undertaken on a voluntary participation resulted in high staff acceptance (Fletcher et al. 2017, 2019b). Staff in these studies reported that Safewards was able to reduce conflict and enable them to feel safer and more connected with consumers. High levels of acceptability also reflected a belief that Safewards could reduce levels of conflict and containment (Fletcher et al. 2019b) and staff who are optimistic and motivated are keen to accept new ideas (Maguire et al. 2018).

Alternatively, staff in one study interpreted the training they received as being too basic, and subsequently, they felt patronized, which led to a questioning of the potential effectiveness of the Safewards model (Higgins et al. 2018). This adversely impacted the level of overall staff acceptance within the implementation process (Cabral & Carthy 2017; Higgins et al. 2018). This is despite some staff holding positive views about Safewards, recognizing its potential to effect culture change and improve staff/consumer interactions. The authors described those who did not believe in the model as having a negative influence on staff that were motivated to facilitate implementation (Cabral & Carthy 2017; Higgins et al. 2018). Similarly, some staff held pessimistic perceptions around the effectiveness of Safewards (Price et al. 2016). Furthermore, negative perception of Safewards was partly explained by a view that conflict is caused by consumers and a belief that staff could not influence this dynamic (Higgins et al. 2018). At the same time, staff expressed the view that they were already practising in a way that reflected some of the components of Safewards (Cabral & Carthy 2017; Price et al. 2016).

Consumer experience and recovery principles

Of the nineteen articles included in this literature review, two specifically addressed the views of the consumers. One article described a recovery measure called the Developing Recovery Enhancing Environments Measure (DREEM) to evaluate Safewards (Cabral & Carthy 2017), but limited details were reported. The DREEM is a tool designed to evaluate an organization provision of an environment and culture that aligns with recovery (Campbell‐Orde et al. 2005). This study suggested consumers perceived practice to be more aligned with personal recovery as a result of implementing Safewards, in part due to an improvement in the ‘therapeutic milieu’ (Cabral & Carthy 2017).

Fletcher et al. (2019a) identified that consumer perspectives had not been represented in the literature underpinning Safewards. They discussed how Safewards impacted on the experience of consumers within inpatient settings and how it can facilitate a recovery‐based approach. In investigating the views of consumers about Safewards, they found consumers felt safer and more connected with staff, and more positive about the experience of being in an inpatient environment (Fletcher et al. 2019a). Consumers also identified that because of the implementation of Safewards, recovery‐based philosophical approaches were more apparent. Consumers commented on the degree of respect and hope they felt and an improved overall feeling of safety and sense of community within the inpatient unit (Fletcher et al. 2019a). There were however some concerns raised by consumers around the language within some of the interventions in the model. Specifically, some interventions were seen as condescending or patronizing, flagging that staff may still execute the interventions in a way they were not intended or were not consistent with the model (Fletcher et al. 2019a).

Similar concerns are raised in a discursive paper written by Kennedy et al. (2019). They offered a critique of the Safewards model from a lived experience perspective and specifically shed light on the role of trauma in the consumer experience, as well as the ongoing power differentials between staff and consumers (Kennedy et al. 2019). Consumers have suggested improvements to ensure consumer friendly language and to address potentially tokenistic or patronizing interpretations of the model (Fletcher et al. 2019a).

Some limitations of the model are recognized by consumers, such as that Safewards is not explicit in addressing safety concerns that consumers raise regarding inpatient mental health units. However, enhancements to the Safewards model are recommended as potentially addressing some of these limitations, while acknowledging they may be more challenging to implement (Kennedy et al. 2019).

In summary, concerns about Safewards are reflected within three main domains:

Variability in the degree to which Safewards is successfully implemented and the level of staff engagement.

Variable outcomes in studies have examined its effectiveness for reducing containment measures.

How the model is experienced by consumers and how it meets their needs is inconclusive.

Discussion

This review identified Safewards as an evidence‐based approach that can reduce restrictive practices such as containment and conflict events, if implemented with high fidelity (Baumgardt et al. 2019; Bowers et al. 2015; Dickens et al. 2020; Fletcher et al. 2017; Maguire et al. 2018). Poor fidelity results reflect may reflect low staff acceptance, which in turn leads to poorer outcomes in reducing conflict and containment (Higgins et al. 2018; Price et al. 2016). Staff perceptions around the acceptability of the Safewards varied. Some studies reflected a lack of confidence in Safewards, or a view that it lacked sophistication to be effective (Higgins et al. 2018; Price et al. 2016), while others reported that staff were well engaged with the model and its interventions (Fletcher et al. 2019b; Maguire et al. 2018). In relation to the question of how consumers experience Safewards, this review revealed that perspectives of consumers are limited (Fletcher et al. 2019a; Kennedy et al. 2019).

The findings of this review reveal three broad issues that requires further discussion. Firstly, the degree of staff acceptance and engagement with the Safewards model requires attention, including how this reflects the philosophical underpinnings of mental health nurses (MHN) practice more broadly (Santangelo et al. 2018). Secondly, how can Safewards facilitate contemporary mental health approaches such as recovery‐oriented practice (Lim et al. 2017). Finally, and critically important for the provision of recovery‐based practice, it is the lack of meaningful consumer involvement in undertaking evaluations of Safewards (Kennedy et al. 2019).

Staff acceptance and engagement

The way that aggression may be attributed to consumer factors and the view that consumers are responsible for aggressive incidents requires greater scrutiny, as the evidence behind Safewards suggests that consumer factors only account for a small proportion of overall incidents (Bowers 2014; Bowers et al. 2014; Cutcliffe & Riahi 2013). Factors associated with the unit environment play a significant part in how aggression manifests (Bowers et al. 2014). Furthermore, presenting behaviour is not always a result of a consumers diagnosed mental health condition (Lim et al. 2017) and only 1 in 5 consumers in inpatient mental health units are found to be aggressive (Iozzino et al. 2015). This may provide an explanation as to why some staff question the relevance of Safewards because the consumers may be ‘blamed’ for aggressive incidents (Higgins et al. 2018; Price et al. 2016).

More recently, the discourse has started to shift beyond the idea that consumers are responsible for creating risk, to recognizing ways in which the healthcare system itself may be responsible for harm towards consumers (Muir‐Cochrane & Duxbury 2017). The way in which aggression and violence is perceived can both impact on how aggressive incidents manifest, and the subsequent staff response (Ezeobele et al. 2019). Specifically, ambivalence about the effectiveness of Safewards may reflect a belief that consumer safety cannot be influenced (Higgins et al. 2018) and a lack of confidence in utilizing non‐restrictive practices to manage acute distress (Lim et al. 2019; Maguire et al. 2017). Despite the existing evidence supporting the influence of staff, and specifically MHNs in preventing aggressive incidents (Bowers et al. 2014), more work is needed to understand how this influence manifests in practice. MHNs can significantly influence how consumers experience safety within inpatient units (Cutler et al. 2020) some of which rests on prioritizing engagement and recovery‐oriented practice (Cutler et al. 2021; Lim et al. 2017). While it is a positive outcome that staff felt safer because of Safewards implementation (Fletcher et al. 2019b), this still may perpetuate the idea that aggression is driven by consumers.

Safewards facilitating recovery‐oriented practice

Safewards provides an opportunity to align practice with recovery‐oriented concepts (Fletcher et al. 2019a; Lim et al. 2017). The degree to which Safewards can act as a platform for building recovery‐oriented practice requires further investigation. In fact, Safewards has been identified as an ideal framework from which to launch and utilize recovery‐oriented practice (Lim et al. 2017). Recovery‐oriented practice is directly linked to how consumers experience safety, in that consumers feel safer when MHNs positively interact and engage with them (Cutler et al. 2020). Recovery‐oriented practice can reduce the risk of aggression and limit the use of restrictive practices within inpatient units (Lim et al. 2017).

Recovery‐oriented practice is realized when MHNs are present and available for consumers (Cutler et al. 2020; Pelto‐Piri et al. 2019), which enables trusting therapeutic relationships to be established (Cutler et al. 2020; Henderson 2014). This also involves active listening, showing respect and facilitating consumer choice (Cutler et al. 2020, 2021) all of which are well aligned with the intent of Safewards and many of the interventions (Fletcher et al. 2019b). These attributes are necessary for recovery‐oriented practice (Lim et al. 2019) and clearly stipulated within policy directives, and the broader literature as critical for contemporary service delivery (Isobel 2019; McKenna et al. 2014; NSW Mental Health Commission 2014). Despite this, recovery‐oriented practice has struggled to be established within inpatient mental health units (McKenna et al. 2014; Santangelo et al. 2018) partly due to a lack of understanding about how to apply this approach (Mullen et al. 2020b) and a task‐driven culture that exists within these settings (Terry & Coffey 2019).

The dominance of the medical model is considered to create a barrier to recovery‐oriented practice within inpatient settings (Mullen et al. 2020a). MHNs experience tensions inherent in adopting recovery‐oriented practice in an environment where coercive practices are common, and where consumers are perceived as being ‘too unwell’ to be actively involved (Mullen et al. 2020a).

Safewards provides an opportunity to ‘connect the dots’ and a platform by which to not only minimize restrictive practices (Fletcher et al. 2019a), but to understand how recovery‐oriented practice (Lim et al. 2017) can be achieved to enhance overall consumer safety (Cutler et al. 2020; Kennedy et al. 2019) within inpatient mental health units.

This is significant because recovery‐oriented practice needs to be part of the solution in preventing and responding to the risk of aggression (Lim et al. 2019) and addressing the harm associated with restrictive practices such as seclusion and restraint that are used to manage aggression (Duxbury et al. 2019). Despite efforts to eliminate these harmful practices, they continue to be used within mental health inpatient units (Muir‐Cochrane et al. 2018) and undermine recovery‐oriented practice (Lim et al. 2019).

It is also important to consider the influence of broader workplace factors impacting on the capacity of MHNs within inpatient mental health units to engage with consumers (Cutler et al. 2020). Working in these environments can be stressful and can not only erode the capacity of MHNs to engage effectively (Foster et al. 2020), but can lead to vicarious trauma (Lee et al. 2015). While the role of resilience in mitigating the adverse impact of stressful events has been explored (Foster et al. 2019), the role of recovery‐oriented practice may also be an important consideration because it can reduce the perceived risk of aggression and the risk of conflict (Lim et al. 2019). This makes the need to explore the connection between Safewards and recovery‐oriented practice more urgent and critical for ensuring consumer safety.

Safewards and the consumer experience

There is clearly a need for more consumer‐focused research into Safewards that can explicitly connect the model with not only recovery‐focused practice, but consumer definitions of safety (Kennedy et al. 2019; Lim et al. 2017) that are essential for supporting personal recovery (Cutler et al. 2021). There are also some concerns about the language and execution of some of the interventions in the model that require more discussion with consumers (Fletcher et al. 2019a; Kennedy et al. 2019).

Safewards has been found to facilitate engagement between staff and consumers (Fletcher et al. 2019b; Maguire et al. 2018) and improve the overall level of safety (Cabral & Carthy 2017). While safety is a key objective of the Safewards model, the way consumers experience safety within the model is less clear (Kennedy et al. 2019). A significant limitation of the literature analysed for this review is the underrepresentation of consumer perspectives (Kennedy et al. 2019). Only one study explored consumer experiences of Safewards, revealing recovery‐oriented practices were helpful to the consumer (Fletcher et al. 2019a). While a very encouraging outcome, further investigations are needed from a consumer’s perspective as to how Safewards can facilitate recovery‐oriented practice.

A way of consolidating the consumers experience of safety within inpatient mental health units into Safewards has been proposed (Kennedy et al. 2019) and the key elements of the consumers experience of safety within inpatient units has been articulated (Cutler et al. 2020, 2021). There needs to be more discussion around how these perspectives are embedded in the Safewards model to not only address the ongoing use of restrictive practices (Duxbury et al. 2019) to but also ensure consumer safety and recovery‐oriented practice are both understood and considered in the future. Safewards aims to improve the safety of all those within inpatients environments (Bowers 2014) and so consumers need to be meaningfully involved in all aspects of its design, implementation and evaluation. A co‐design approach with consumers is required consistent with current approaches to practice improvement and is, therefore, preferred (Matthews et al. 2017).

Co‐design requires a commitment to consumer‐driven practice development that involves a broader culture shift in the way that staff view co‐design including a more positive view of the role of peer workers (Byrne et al. 2017). The important role that consumers have in informing recovery‐oriented practice has been identified (Byrne et al. 2018), and the emergence of the peer workforce is one tangible example of how this contribution is being formalized and considered valuable (Byrne et al. 2017). For Safewards to realize its potential and align with recovery‐oriented practice, people with a lived experience through roles such as the peer worker need to be actively involved (Byrne et al. 2017). This involvement also needs to be facilitated from a leadership role that incorporates co‐design principles rather than being confined to consultative role only (Byrne et al. 2019).

An opportunity for a co‐design approach also lies within the description of additional Safewards interventions that were part of the original model but later removed (Kennedy et al. 2019). As an example, ‘Random Kindness’ proposes that staff initiate two acts of generosity or kindness towards consumers and staff as a way of illustrating commitment to consumers and to show support for other staff (Kennedy et al. 2019). It has been argued by consumers that these draft interventions should be re‐examined and incorporated into future Safewards research, because they are important to consumers and represent humanistic qualities aligned with safety (Kennedy et al. 2019).

The need for further consumer‐based investigations into Safewards is highlighted by concerns from consumers about the potential for some of the interventions to be executed in a way that is condescending or patronizing, or that perpetuates the power differential (Fletcher et al. 2019a; Kennedy et al. 2019). The basis for this lies within unequal staff–consumer relationships that are still apparent (Kennedy et al. 2019) and that consumers need to be viewed as ‘equals’ to feel safe (Cutler et al. 2021). In other words, a recovery‐oriented approach that is not about power and control over, but about engagement and recognizing that preserving the individual’s autonomy has high value for the consumer (Cutler et al. 2021; Lim et al. 2017). What is needed is a collaborative or co‐design approach that facilitates the sharing of responsibility for Safewards with consumers (Byrne et al. 2019). This also requires staff to share power, which is often invisible and subsequently goes unnoticed (Cutcliffe & Happell 2009).

Limitations

There are some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results of this literature review. While a systematic approach was undertaken in identifying the key search terms, it is conceivable that some relevant terms were not captured in the search. Several Safewards articles were excluded because they involved settings other than adult inpatient mental health or forensic mental health units or were non‐English language articles. Despite this, these excluded articles may provide relevant information to the current understanding of Safewards.

Conclusion

Safewards is a model that has demonstrated evidence in reducing restrictive practices and in reducing conflict events if rigorously implemented (Fletcher et al. 2017). This is important as it serves as a tangible strategy for improving the therapeutic impact of inpatient and forensic mental health units and reducing and eliminating the potentially harmful and traumatic coercive practices. The connection that Safewards may have with recovery‐oriented practice and consumer perspectives of safety is acknowledged, but its significance is not fully understood (Fletcher et al. 2019a).

More work is needed however to engage staff broadly, and specifically MHNs in the model and to ensure it is seen as acceptable and meaningful, and that it is reframed as being in the interests of consumers and their recovery. It is also important to illustrate how Safewards aligns with contemporary mental health nursing practice, helps fulfil a recovery‐oriented and consumer‐focused orientation to practice and contributes to the overall safety within these environments.

A further important consideration is to ensure that Safewards is provided from the perspective of the consumer and that it is valued by consumers (Kennedy et al. 2019). Ultimately, this means that a co‐production approach is required for the implementation of Safewards. There remains a significant gap in the literature around the consumer experience of Safewards and further investigations need to be undertaken to ensure consumer perspectives and their experience of safety are strengthened within the model.

Implications for Practice

This review presents a synthesis of the current literature for the Safewards model of care within inpatient mental health and forensic units. The findings demonstrate evidence for the ability of the model to reduce the incidence of conflict and containment events and to improve the consumer experience. Despite this, there remains uncertainty as to how well the model reflects the consumer experience of safety and supports recovery‐oriented practice. There are still inconsistencies in how MHN identify with the underlying principles of the model. Recommendations from this review include incorporating consumer perspective through a co‐production framework to articulate consumer definitions of safety and consumer‐driven language within the model. There also needs to be a reconnection between Safewards and MHN practice that recognizes the value of recovery‐oriented practice and therapeutic engagement to consumers, as well as and the sharing of power and control within inpatient settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Angela Smith, Research Librarian with the Hunter New England Local Health District for her assistance in undertaking the literature search. No external funding was received for this review. Open access funding provided by The University of Newcastle.

All listed authors meet authorship criteria according to the guidelines of the Internationals Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors are in agreement with the manuscript.

Declaration of interest: The authors have no interests to disclose in relation to this manuscript.

References

- Baumgardt, J. , Jäckel, D. , Helber‐Böhlen, H. et al. (2019). Preventing and reducing coercive measures‐an evaluation of the implementation of the Safewards model in two locked wards in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley, P. (2013). Qualitative Data Analysis. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, L. (2014). Safewards: A new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21, 499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, L. , Alexander, J. , Bilgin, H. et al. (2014). Safewards: The empirical basis of the model and a critical appraisal. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 21, 354–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, L. , James, K. , Quirk, A. , Simpson, A. , Stewart, D. & Hodsoll, J. (2015). Reducing conflict and containment rates on acute psychiatric wards: The Safewards cluster randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52, 1412–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, L. , Happell, B. & Reid‐Searl, K. (2017). Risky business: Lived experience mental health practice, nurses as potential allies. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26, 285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, L. , Roennfeldt, H. , Wang, Y. & O'Shea, P. (2019). 'You don't know what you don't know': The essential role of management exposure, understanding and commitment in peer workforce development. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28, 572–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, L. , Stratford, A. & Davidson, L. (2018). The global need for lived experience leadership. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 41, 76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, A. & Carthy, J. (2017). Can Safewards improve patient care and safety in forensic wards? A pilot study. British Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 6, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell‐Orde, T. , Chamberlin, J. , Carpenter, J. & Leff, S. (2005). Measuring the Promise: A Compendium of Recovery Measures, vol II. Cambridge: Human Services Research Institute Evaluation Center. [Google Scholar]

- Cutcliffe, J. & Happell, B. (2009). Psychiatry, mental health nurses, and invisible power: Exploring a perturbed relationship within contemporary mental health care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 18, 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutcliffe, J. R. & Riahi, S. (2013). Systemic perspective of violence and aggression in mental health care: Towards a more comprehensive understanding and conceptualization: Part 1. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22, 558–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutcliffe, J. R. , Santos, J. C. , Kozel, B. , Taylor, P. & Lees, D. (2015). Raiders of the Lost Art: A review of published evaluations of inpatient mental health care experiences emanating from the United Kingdom, Portugal, Canada, Switzerland, Germany and Australia. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24, 375–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, N. A. , Sim, J. , Halcomb, E. , Moxham, L. & Stephens, M. (2020). Nurses' influence on consumers' experience of safety in acute mental health units: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29, 4379–4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, N. A. , Sim, J. , Halcomb, E. , Stephens, M. & Moxham, L. (2021). Understanding how personhood impacts consumers' feelings of safety in acute mental health units: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30, 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens, G. L. , Tabvuma, T. & Frost, S. A. & Group, S. S. S. (2020). Safewards: Changes in conflict, containment, and violence prevention climate during implementation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 20, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, J. , Thomson, G. , Scholes, A. et al. (2019). Staff experiences and understandings of the REsTRAIN Yourself initiative to minimize the use of physical restraint on mental health wards. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28, 845–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeobele, I. E. , McBride, R. , Engstrom, A. & Lane, S. D. (2019). Aggression in acute inpatient psychiatric care: A survey of staff attitudes. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 51, 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J. , Buchanan‐Hagen, S. , Brophy, L. , Kinner, S. A. & Hamilton, B. (2019a). Consumer perspectives of Safewards impact in acute inpatient mental health wards in Victoria, Australia. Frontiers in Psychiatry Frontiers Research Foundation, 10, 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J. , Hamilton, B. , Kinner, S. A. & Brophy, L. (2019b). Safewards impact in inpatient mental health units in Victoria, Australia: Staff perspectives. Frontiers in Psychiatry Frontiers Research Foundation, 10, 462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J. , Reece, J. , Kinner, S. A. , Brophy, L. & Hamilton, B. (2020). Safewards training in Victoria, Australia: A descriptive analysis of two training methods and subsequent implementation. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 58, 32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J. , Spittal, M. , Brophy, L. et al. (2017). Outcomes of the Victorian Safewards trial in 13 wards: Impact on seclusion rates and fidelity measurement. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26, 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, K. , Roche, M. , Delgado, C. , Cuzzillo, C. , Giandinoto, J. A. & Furness, T. (2019). Resilience and mental health nursing: An integrative review of international literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28, 71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, K. , Roche, M. , Giandinoto, J. A. & Furness, T. (2020). Workplace stressors, psychological well‐being, resilience, and caring behaviours of mental health nurses: A descriptive correlational study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29, 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, K. (2014). The importance of the therapeutic relationship in improving the patient's experience in the in‐patient setting. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23, 97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, N. , Meehan, T. , Dart, N. , Kilshaw, M. & Fawcett, L. (2018). Implementation of the Safewards model in public mental health facilities: A qualitative evaluation of staff perceptions. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 88, 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q. , Pluye, P. , Fabregues, S. et al. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018: User Guide. Montreal, QC: McGill University. Department of Family Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Iozzino, L. , Ferrari, C. , Large, M. , Nielssen, O. & de Girolamo, G. (2015). Prevalence and risk factors of violence by psychiatric acute inpatients: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One, 10, e0128536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isobel, S. (2019). 'In some ways it all helps but in some ways it doesn't': The complexities of service users' experiences of inpatient mental health care in Australia. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28, 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, K. , Quirk, A. , Patterson, S. , Brennan, G. & Stewart, D. (2017). Quality of intervention delivery in a cluster randomised controlled trial: A qualitative observational study with lessons for fidelity. Trials, 18, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, H. , Roper, C. , Randall, R. et al. (2019). Consumer recommendations for enhancing the Safewards model and interventions. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28, 616–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipping, S. M. , De Souza, J. L. & Marshall, L. A. (2019). Co‐creation of the Safewards model in a forensic mental health care facility. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40, 2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. , Daffern, M. , Ogloff, J. R. & Martin, T. (2015). Towards a model for understanding the development of post‐traumatic stress and general distress in mental health nurses. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24, 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickiewicz, J. , Adamczyk, N. , Hughes, P. P. , Jagielski, P. , Stawarz, B. & Makara‐Studzinska, M. (2020). Reducing aggression in psychiatric wards using Safewards‐A Polish study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57, 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, E. , Wynaden, D. & Heslop, K. (2017). Recovery‐focussed care: How it can be utilized to reduce aggression in the acute mental health setting. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26, 445–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, E. , Wynaden, D. & Heslop, K. (2019). Changing practice using recovery‐focused care in acute mental health settings to reduce aggression: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28, 237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, T. , Daffern, M. , Bowe, S. J. & McKenna, B. (2017). Predicting aggressive behaviour in acute forensic mental health units: A re‐examination of the dynamic appraisal of situational aggression's predictive validity. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26, 472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, T. , Ryan, J. , Fullam, R. & McKenna, B. (2018). Evaluating the introduction of the Safewards model to a medium‐ to long‐term forensic mental health ward. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 14, 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, E. , Cowman, M. & Denieffe, S. (2017). Using experience‐based co‐design for the development of physical activity provision in rehabilitation and recovery mental health care. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 24, 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, A. , Klugarova, J. , Yan, H. & Florescu, S. (2015). Innovations in the systematic review of text and opinion. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare, 13, 188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, B. , Furness, T. , Dhital, D. et al. (2014). Recovery‐oriented care in acute inpatient mental health settings: An exploratory study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35, 526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin, K. A. , Du Wick, A. , Collazzi, C. M. & Puntil, C. (2013). Recovery‐oriented practices of psychiatric‐mental health nursing staff in an acute hospital setting. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 19, 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D. & GROUP, T. P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Open Medicine, 3, 123–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir‐Cochrane, E. & Duxbury, J. A. (2017). Violence and aggression in mental health‐care settings. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26, 421–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir‐Cochrane, E. , O'Kane, D. & Oster, C. (2018). Fear and blame in mental health nurses' accounts of restrictive practices: Implications for the elimination of seclusion and restraint. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27, 1511–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, A. , Harman, K. , Flanagan, K. , O'Brien, B. & Isobel, S. (2020a). Involving mental health consumers in nursing handover: A qualitative study of nursing views of the practice and its implementation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29, 1157–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, A. , Isobel, S. , Flanagan, K. et al. (2020b). Motivational interviewing: Reconciling recovery‐focused care and mental health nursing practice. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41, 807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NSW Mental Health Commission (2014). Living Well: A Strategic Plan for Mental Health in NSW. Sydney, NSW: NSW Mental Health Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Olasoji, M. , Plummer, V. , Reed, F. et al. (2018). Views of mental health consumers about being involved in nursing handover on acute inpatient units. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27, 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, A. , White, H. , Bath‐Hestall, F. , Apostolo, J. , Salmond, S. & Kirikpatrick, P. (2014). Methodology for JBI mixed methods systematic reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute Manual, 1, 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pelto‐Piri, V. , Wallsten, T. , Hylen, U. , Nikban, I. & Kjellin, L. (2019). Feeling safe or unsafe in psychiatric inpatient care, a hospital‐based qualitative interview study with inpatients in Sweden. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, O. , Burbery, P. , Leonard, S.‐J. & Doyle, M. (2016). Evaluation of Safewards in forensic mental health. Mental Health Practice, 19, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. , Leeman, J. , Knafl, K. & Crandell, J. L. (2013). Text‐in‐context: A method for extracting findings in mixed‐methods mixed research synthesis studies. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69, 1428–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo, P. , Procter, N. & Fassett, D. (2018). Mental health nursing: Daring to be different, special and leading recovery‐focused care? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27, 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schardt, C. , Adams, M. B. , Owens, T. , Keitz, S. & Fontelo, P. (2007). Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Informatics & Decision Making, 7, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensgaard, L. , Andersen, M. K. , Nordentoft, M. & Hjorthoj, C. (2018). Implementation of the Safewards model to reduce the use of coercive measures in adult psychiatric inpatient units: An interrupted time‐series analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 105, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry, J. & Coffey, M. (2019). Too busy to talk: Examining service user involvement in nursing work. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40, 957–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingleff, E. B. , Bradley, S. K. , Gildberg, F. A. , Munksgaard, G. & Hounsgaard, L. (2017). "Treat me with respect". A systematic review and thematic analysis of psychiatric patients' reported perceptions of the situations associated with the process of coercion. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 24, 681–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore, C. (2017). Evaluation of Safewards in forensic mental health: A response. Mental Health Practice, 20, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, R. & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C. , Rouse, L. , Rae, S. & Kar Ray, M. (2018). Mental health inpatients' and staff members' suggestions for reducing physical restraint: A qualitative study. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing, 25, 188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]