Abstract

Introduction

Teleconsultation education in health care and social work education is under‐reported. However, literature indicates that educating the workforce in teleconsultation skills is essential to continue with safe, high‐quality delivery of services and increases the likelihood of implementing teleconsultations in health care. Training for students should, therefore, be encouraged. This systematic literature review aims to investigate global experiences of teleconsultation training in undergraduate health care and social work education.

Methods

A systematic review of peer‐reviewed literature was undertaken. The review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines. Electronic databases were searched for eligible evidence. Studies were included only if they described and evaluated teleconsultation education for undergraduate health care and social work students.

Results/Discussion

This review shows that mandatory education in teleconsultation is limited in undergraduate health care and social work education. Narrative synthesis and analysis of 14 studies led to the development of two themes: pedagogical aspects, and perspectives on telecommunication and teleconsultation learning and teaching. Practical experiences with simulated patients or during clinical placements with real patients were the most common mode of delivery. Feedback on teleconsultation education was generally positive; overall, health care students felt more confident using teleconsultation and valued safety of learning through simulation.

Conclusion

Teleconsultation education is a legitimate way to expose students to telehealth. High satisfaction rates, increased knowledge and confidence in use indicate the positive impact this learning has on students. Nevertheless, further high‐quality research and guidance for educators are warranted.

1. INTRODUCTION

Teleconsultation is defined as a consultation provided remotely by using information communication technology (ICT) such as telephone and videocommunication platforms. 1 Despite evidence highlighting that teleconsultations are as effective as face‐to‐face interventions in terms of health outcomes and costs, 2 further endeavours to develop and strategically implement digital technologies in health care systems are needed. 3

Literature suggests that teleconsultations are well established in care and management of long‐term conditions. Nonetheless, the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic led to a surging number of teleconsultations via video or telephone worldwide. 4 , 5 National guidelines have been developed to acknowledge the way in which communication with patients has changed. 6 This guidance is necessary as teleconsultations require different skills in digital communication. 7 Teleconsultations must, therefore, be addressed in education and training for health care and social work professionals and students, in the same way that face‐to‐face communication is. 6 , 7

The Topol Review 8 briefly acknowledged the need for training future health care workers and predicted that remote consultations would replace most of the face‐to‐face interactions in the future. Educational initiatives for health care and social work professionals are, however, under‐reported. 9 Furthermore, although universities are responsible for preparing the future health care workforce for a digitalised health care setting, 10 the guidance for delivering this education, especially at undergraduate level, is limited, 11 , 12 focussed on training at post‐graduate level, or is geographically limited. 9 , 13 This limited knowledge and understanding of teleconsultation training in undergraduate education worldwide highlights the need for teleconsultation training in undergraduate education. 14

Limited knowledge and understanding of teleconsultation training in undergraduate education worldwide highlights the need for teleconsultation training in undergraduate education.

This systematic review aims to describe how teleconsultation learning and teaching is delivered to undergraduate health care and social work students in academic and clinical settings and to explore how teleconsultation learning and teaching is received by students and faculty.

The initial question guiding this review is: How is teleconsultation experienced and taught (delivered, implemented, assessed) in undergraduate health care and social work education?

2. METHODS

This mixed‐methods systematic literature review strategy was based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines, 14 and the reporting followed the PRISMA Statement (Supporting Information C).

Guided by the SPICE framework, 15 key terms were identified, and a search was conducted using the databases displayed in Table 1. Key terms were adapted for the requirements of each database. An example PubMed search strategy is provided in Supporting Information A.

TABLE 1.

Searched databases, the SPICE framework and related key words for the search strategy

| Databases |

|---|

| Academic Search Complete, British Education Index, Educational Administration Abstracts, ERIC and MEDLINE (accessed through EBSCOhost), CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. |

| SPICE component | Key terms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S |

Setting Where? |

Higher education, academic, placement, undergraduate stud*, college, institute, center/centre | ||

| P |

Perspective For whom? |

Undergraduate med* student Preregistered med* student Prequalified med* student |

health professional student*, allied health student* nursing students |

Social work student* |

| teachers, professors, trainers, educators, tutors, facilitators, faculty | ||||

| I |

Intervention What? |

curriculum, learning, teaching, education | ||

| Telehealth, teleconsultation, telemedicine, video consultation, telecommunication, information communication technology, digital health, e‐health | ||||

| C |

Comparison Compared with what? |

face to face communication, face to face consultation, in person communication, in person consultation | ||

| E |

Evaluation With what result? |

Skill acquisition, skill development, knowledge acquisition, knowledge development eHealth literacy |

||

| attitude, experience, perceptions, feedback, recommendations | ||||

The results of all searches were collected, uploaded to and stored in the literature management software EndNote. Three authors (AOM, LCW and VOC) independently screened the literature against the a priori defined eligibility criteria (Supporting Information D) and discussed below. Disagreements were resolved through discussion among the authors. Quality appraisal was undertaken using the JBI appraisal checklists (Supporting Information B).

To find underlying themes and concepts across the included studies, a thematic synthesis approach 16 was used. Quantitative and qualitative data from each study were compared, contrasted and summarised qualitatively.

3. RESULTS

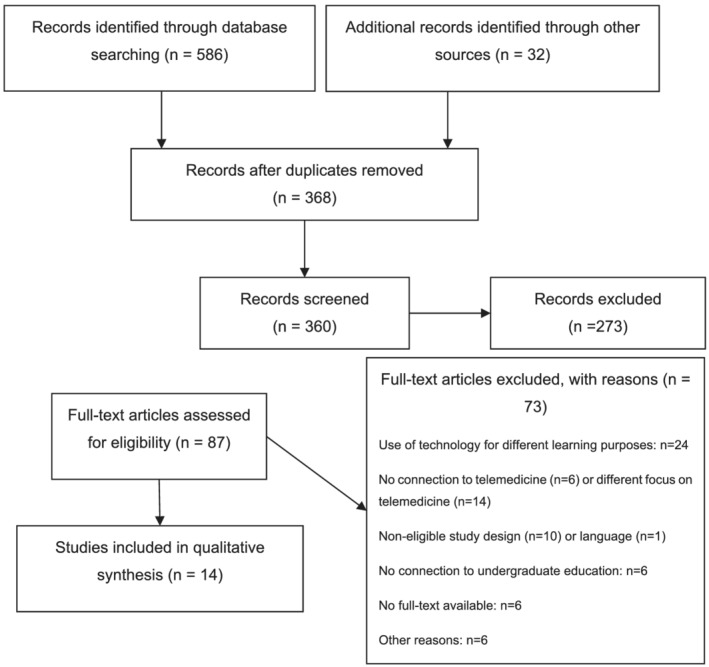

A total of 586 records were identified by the database search. An additional 32 records were identified from screening the reference list of relevant papers. After removing duplicate records, the title and abstract of 360 records were screened, which resulted in 87 studies being identified for full‐text evaluation. Of these, a total of 14 studies matched the eligibility criteria (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow chart: Eligibility criteria were applied at all stages of article screening and assessment. Full texts were excluded with reasons

The study characteristics and main results are summarised in Table 2. Eight studies were conducted in the USA, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 two in Australia 25 , 26 and the UK 27 , 28 and one each in Germany 29 and Spain. 30 The studies were published in 12 different journals between 2010 and 2020.

TABLE 2.

Study characteristics and main results. Critical appraisals for mixed‐methods studies mention the quantitative methods first. The results are displayed in the number of items answered with yes (Y)/no (N)/unsure (U)/not applicable (NA)

| Author(s), year | Journal | Country | Study aim | Target group | n | Setting (mode, length) | Study type, type of evaluation | Results | Critical appraisal Y/N/U/NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al., 2020 | Cureus | USA | To evaluate a telemedicine experience during the COVID‐19 pandemic | 3rd year medical students | 20 | Theoretical online course and seminar, telephone screening with patients, shadowing teleconsultations between physicians and patients | Mixed methods | Learning about telemedicine would be an asset to students' education as students were not familiar with the concept of telemedicine. Students value the different patient scenarios and the immediate feedback from the practitioners after the consultation. This form of learning was an appreciated possibility for students to have contacts with patients during the pandemic. |

1/5/0/2 0/10/0/0 |

| Bulik & Shokar, 2010 | Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare | USA | To report on an elective course on telemedicine | 4th year medical students | 7 | Online introduction lectures, site visits and a reflective paper | Mixed methods | All students indicated that it was an effective, inspiring experience and would recommend it to their peers. After the training, students felt they acknowledge pitfalls in telemedicine more and they understood the opportunity for telemedicine for managing chronic diseases. |

1/4/3/0 1/7/2/0 |

| Cantone et al., 2019 | MedEdPORTAL | USA | To expose students to telemedicine and assess videoconsultations | 2nd, 3rd, 4th year medical students | 287 | TeleOSCE during students' clerkship | Qualitative study | The students felt the need for a training in teleconsultations before taking the teleOSCE; however, feedback was generally positive. However, students would prefer to be assessed on single skills rather than the combination of more skills. The immediate feedback after the teleOSCE was perceived useful. | 1/7/2/0 |

| Christner et al., 2010 | Academic Medicine | USA | To assess the effects of training in email communication | Medical students | 89 | Group teaching session, including group discussions regarding email communication | Pre–post design | Knowledge about email communication, communication skills and professionalism improved significantly after the training. | 4/4/0/0 |

| Darnton et al., 2020 | Medical Teacher | UK | To evaluate students' and supervisors' experience of clinical experience during the COVID‐19 lockdown measures | 2nd year medical students | 13 | Teleconsultations supervised by practitioners, consulting from home | Qualitative study | The students were satisfied with the variety of patient cases encountered during the teleconsultations. The immediate feedback from the practitioners was helpful; however, the missing face‐to‐face interactions made the feedback for the supervisors more difficult. Choosing the appropriate patients for the teleconsultations was challenging for the practitioners. Students had to make effort to ensure patients' confidentiality and reported on technical difficulties as being stressful. The missing physical examination reduced the students' perception of educational value in terms of clinical skills. | 6/0/4/0 |

| Dzara et al., 2013 | Academic Psychiatry | USA | To evaluate telepsychiatry training, the perception of supervision and the usefulness for future work | Medical students and residents | 15 | Students conducted teleconsultations and remote examinations while supervised by a clinician | Cross‐sectional study | The training was perceived as relevant for students' future career and enhanced the understanding of clinical responsibilities in telepsychiatry. The communication with patients was perceived more difficult. Even though the supervision was helpful, previous theoretical knowledge about telepsychiatry would have increased the learning outcome. | 1/2/5/0 |

| Edirippulige et al., 2012 | Journal of Medical Internet Research | Australia | To assess students' perceptions of an eHealth practicum | Health science students | 66 | One day, theoretical lectures, practical activities, observations of telecommunications, visits to telehealth centres | Qualitative study | Most students rated the practicum as a relevant activity to gain practical skills in telemedicine for their future career. Students would prefer a stronger focus on high‐quality practical activities rather than lectures in the beginning, which were perceived as a repetition of components learnt in a previous eHealth course. | 1/6/2/1 |

| Fisher et al., 2014 | Clinical Teacher | UK | To develop and evaluate a simulation training in interprofessional telephone communication | 3rd year medical and surgery students | 52 | Previous communication training, lecture, simulation between students, nurses and practitioners | Mixed methods | The self‐rated confidence in interprofessional communication with nurses and physicians increased significantly after the simulation training. The safe learning environment was appreciated, and students wished to have more time to practise telecommunication with other professionals. The training they received prior was perceived insufficient. |

2/4/1/2 0/8/2/0 |

| Jimenez‐Rodriguez & Arrogante, 2020 | Healthcare | Spain | To analyse the perception and satisfaction with video consulting simulation scenarios | 3rd year nursing students | 93 | Three patient scenarios (lasting 4 hours each), online video conferences, small groups of 12 to 16 students | Mixed methods | Students were satisfied with the simulation scenario; the learning felt real, safe and relevant for their future career. All students agreed on the practical utility of the training regarding gaining clinical and communication skills. However, students did not think that technical skills improved. The opportunity to make consultations from home had a calming factor for students and they felt less nervous. |

5/2/1/0 2/1/7/0 |

| Mulcare et al., 2020 | MedEdPortal | USA | To develop and assess a curriculum to practise telecommunication and teleconsultation communication strategies | Medical students | 98 | Eight‐hour programme for small groups (8 to 16 students), in‐person lecture, practical activities, online assignment | Mixed methods | Students rated their preparedness for teleconsultations higher after the training. Telemedicine was perceived as relevant for the future work. Especially the simulation scenarios were perceived useful; however, students wished for an earlier exposure in their education. The training should focus more on patient management rather than general information about telemedicine. Students wished for seeing and analysing examples of ‘real‐life’ teleconsultations by a physician or health care professionals. |

1/2/3/3 2/6/2/0 |

| Palmer et al., 2015 | Rural Remote Health | USA | To assess the acceptability and feasibility of teleOSCE | Medical students | 9 | Participation in a teleOSCE | Qualitative study | Taking the teleOSCE was a valuable experience, that did not take long, and raised awareness for patients' health needs in rural areas. It was important that students were familiar with the technology to solve technical difficulties during the exam. The teleOSCE gave students a new understanding of what telemedicine is and how teleconsultations can be used. | 2/7/1/0 |

| Palmer et al., 2017 | Journal of Family Medicine & Community Health | USA | To assess the knowledge of, confidence in and attitudes towards telemedicine | Medical students | 172 | TeleOSCE as one out of four OSCE that students completed during their clerkship | Pre–post design | Knowledge and confidence changed significantly between active and inactive groups. The increase in attitude was not significant. | 4/3/2/0 |

| Rienits et al., 2016 | Clinical Teacher | Australia | To rate students' understanding of the issues and their confidence in conducting a teleconsultation | 3rd year medical students | 59 | Two‐hour programme, theoretical in‐person lectures and simulated patient cases | Pre–post design | Students did not feel very confident in conducting teleconsultations before the training, even though they rated their knowledge about technology high. The training in medicolegal aspects of teleconsultations was perceived as most important. |

1/6/2/0 0/10/0/0 |

| Waschkau et al., 2020 | Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen | Germany | To describe and evaluate a course about the digitalisation in health care in Germany | 4th year medical students | 60 | Six 90‐minute courses, mandatory course, students could choose topics, in‐person lecture, group work | Cross‐sectional study | The session enabled students to have a positive attitude towards teleconsultation and telemedicine. Students were mostly concerned about and want to learn about the technological aspects in teleconsultations. |

2/4/1/1 0/9/1/0 |

Out of the 14 studies identified, 12 studies included medical students. 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 One study included nursing students 30 and one other included allied health professional students. 25 None of the studies included social work students. Only one study interviewed educators. 27 The experiences and opinions of telehealth and teleconsultation education were assessed via mixed‐methods study designs in seven studies. 17 , 18 , 22 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 Qualitative research design was adopted by four studies. 19 , 23 , 25 , 27 Two studies evaluated students' experiences after a learning activity. 20 , 21

Two main themes were identified from the thematic synthesis: pedagogical aspects, and perspectives of teleconsultation teaching and learning. The former theme refers to various structures and characteristics in relation to how teleconsultation was delivered. The latter theme refers to students' and educators' subjective meaning of teleconsultation education and their individual experiences with and opinions of teleconsultation.

Two main themes were identified from the thematic synthesis: pedagogical aspects, and perspectives of teleconsultation teaching and learning.

3.1. Pedagogical aspects

Generally, teleconsultation courses were mostly optional or elective for students. 18 , 19 Only one study reported on mandatory training. 29 Where interactive sessions enabling students to practise teleconsultation skills were described, these usually occurred in small groups of 8 to 16 students 22 , 26 , 30 who were in some cases subdivided into groups of two to three students. 27 , 30

The teaching sessions varied in length and lasted between one and a half hours and 1 day. 17 , 22 , 25 , 26 Courses were also split up into two half days 22 or six afternoon sessions. 29 The learning outcomes for the courses focussed on knowing about the importance of telehealth, 22 the limitations and possibilities of telehealth in general, 18 , 25 , 26 knowing the differences between teleconsultations and face‐to‐face consultations and recognising the effect of telehealth on clinician–patient relationships. 18 , 26

Lectures were used at the beginning of a course to introduce the topic and to prepare students for practical sessions. 18 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 28 The content usually included definitions of telehealth 17 , 29 ; information on resources, tools and technologies 18 , 22 , 26 ; best practice examples 18 ; and business‐related information such as reimbursement, data protection, privacy issues and medicolegal aspects. 18 , 22 , 26 The length of the lectures varied between 30 22 and 90 minutes. 17

Lectures were used at the beginning of a course to introduce the topic and to prepare students for practical sessions.

Following the lectures, most students had the opportunity to apply their skills and knowledge in a practical setting. Various activities included role‐plays of telemedical encounters with patients 22 , 25 , 26 or other health care professionals, 28 observations of clinical teleconsultations 25 , 26 and site visits to hospitals and health institutions offering telehealth. 18 , 25 In two studies, students were exposed to real‐life teleconsultations with patients during their practice placements. 17 , 27

Medical students primarily received individual feedback following a teleconsultation activity. 17 , 19 , 23 , 27 , 28 In some cases, feedback was provided to the whole group. 20 , 22 Clinical and communication skills and knowledge were assessed via a virtual objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), the so‐called teleOSCE. 19 , 23 , 24 The assessment duration ranged between 11 24 and 20 minutes. 23 Approximately 5 minutes was allocated to the provision of feedback. 23 , 24 The patient cases included themes and topics previously covered in students' teaching. 20 , 23 , 28 , 30

The perceived preparedness for teleconsultations prior to explicit training was limited. 17 , 22 However, theoretical lectures, clinical and communication knowledge and skills acquired prior to teleconsultation courses positively influenced students' confidence levels, 25 and knowing the technical equipment used in teleconsultations was reassuring to students. 23 Exposing medical students to simulated interprofessional collaboration and communication scenarios increased self‐rated confidence levels, and more interprofessional telecommunication training was requested. 28

The perceived preparedness for teleconsultations prior to explicit training was limited.

3.2. Perspectives of teleconsultation learning and teaching

Students reported positive attitudes and were generally satisfied with their teleconsultation learning experiences, which were described as relevant for future work settings, 17 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 29 , 30 beneficial, cool, effective, enjoyable, great, informative, inspiring, interesting, useful and valuable. 17 , 18 , 22 , 23 , 25 Students reported that the scenarios felt realistic 28 , 30 and would recommend the elective course to their friends. 18 Prior negative attitudes towards telehealth changed to positive attitudes following a teleconsultation course. 19 , 29 Overall, students emphasised that they would use telehealth in their future practice 23 , 25 ; however, students reported that more training would be helpful to fully understand the advantages of telecommunications and teleconsultations. 19

Some students highlighted limitations of teleconsultations such as changes in communication and relationship with patients due to the lack of face‐to‐face interactions 19 and missing cues in non‐verbal communication. 19 , 27 Further concerns were related to the limited possibilities for physical examinations, which caused a shift in the focus to communication and history taking skills. 27 In one study, students received theoretical information on the possibilities and limitations of physical examinations. 17 To practise physical examinations, students were asked to simulate a physical examination via video‐technology. 22 Various other issues impacted on the confidence levels and the experience of students in conducting teleconsultations: encountering technical issues, the dependency on technology and good internet connection 27 , 30 and the relationships with patients. 27 Generally, however, students preferred to focus on technological aspects in designated telehealth courses rather than combining skills with clinical and communication skills. 19 Despite the positive impact of learning and teaching on telecommunication skills, practical experiences with ICT were not associated with an improvement in technical skills. 30 In contrast, some students gained technological knowledge such as setting up a videoconference and taking clinical images. 25

Students highlighted the need for teleconsultation training prior to the assessment as a first exposure to teleconsultations during the teleOSCE was perceived as stressful. 19 Further training in telehealth before practical experiences 21 and more teleconsultation best practice examples 22 were regarded as valuable preparation. 24

Generally, teleconsultation participation allowed students to practise communication skills. However, students also highlighted the importance of applying clinical reasoning, clinical knowledge and technological skills. 19 Even though communication via ICT was reported to be challenging, 21 , 27 students perceived an improvement in clinical and communication skills after practising videoconsultations. 30

Generally, teleconsultation participation allowed students to practise communication skills.

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review aimed to describe how teleconsultation training in undergraduate health care and social work education is delivered, as well as to report on opinions and experiences associated with teleconsultation education.

In relation to how teleconsultation teaching was delivered, this review showed that it was often taught as an elective course rather than mandatory, meaning that students most interested in telehealth could pursue this as a specific learning opportunity. Mandatory training would ensure that all students have this learning opportunity and would highlight the importance of teleconsultation training within the undergraduate curriculum.

The main findings of this review were that there were a range of delivery methods including theoretical lectures, simulation‐based learning and experiences in placements. The most common method was simulation‐based learning, and few explored the students' experiences in placements. Simulation has been effectively used in health workers' education for several years, 31 , 32 and authentic, realistic case scenarios are appreciated and valued by students. 32 In contrast, a study that evaluated students' learning after working with recorded real‐life general practitioner (GP) consultations found that students prefer to work with real patients rather than with simulated patients. 33 This review highlights the need for further exploration of a range of methods to inform future evidence‐based teleconsultation education and the need for structured guidance for educators. The need for guidelines is reinforced by the desire and need of students to be educated on different technology applications and processes in the health care field (i.e., telehealth). This education should be considered, as telehealth is an emerging field. 1

Although students' perspectives of the teleconsultation learning were generally positive, none of the studies considered the educators' perspectives. This gap in information is crucial because educators are essential stakeholders in medical education and their opinion and perception of telehealth can shape their educational approaches.

The COVID‐19 outbreak limited face‐to‐face encounters with patients, 33 and online learning was often offered as an alternative. While students perceived online learning as insufficient to gain clinical skills, 34 reports on adapted placements to ensure patient encounters during the pandemic were published. 17 , 35 The exposure to teleconsultations increased the perceived likelihood that students would consider using teleconsultation in the future. The extent to which students felt confident in using teleconsultation, however, was not considered by the studies included in this review. As most studies reported that students with an interest in telehealth in general elected to participate in this learning, they may have held prior positive attitudes to the topic of teleconsultation. It is therefore difficult to fully determine the impact on their learning, 17 especially because most studies utilised self‐reported data rather than performance‐based direct measures. Despite recent findings on virtual communication among medical students, which indicated that video consultations with simulated patients reduced nervousness and increased confidence levels in skills required to conduct videoconsultations, 36 early exposure is limited in health care and social work education. Even though ICT are used daily by most people, 37 the use of technology and tools in teleconsultations might be unknown to students. 38

None of the studies described training for social work students, and limited evidence was reported in relation to undergraduate allied health professional programmes. 25 , 30 Therefore, most of the results relate to teleconsultation courses in medical education. This limitation highlights the need for research to explore a wider range of experiences and perspectives within health and social work. Insight into a broader range of health and social work students' perceptions and experiences would illuminate the enablers and barriers to providing teleconsultation courses in those disciplines.

While there were limited reports of educators' perspectives, their opinions on teleconsultation education revealed important insights in their willingness and perceived preparedness to teach and facilitate students' learning. 39 Wentink et al. 40 highlighted the discrepancy between educators who are familiar with and confident in using eHealth tools and educators who did not have these competencies. This can result in barriers, uncertainties and less positive opinions of teaching telehealth 40 and suggests that training for educators could improve confidence and increase student uptake of teleconsultation courses at undergraduate level.

As determined by the results of the critical appraisal, it should be noted that there were some limitations in terms of the quality of some of the studies. The research question, research methodology and results of some of the qualitative studies were often not aligned. Moreover, results often did not represent the participants' opinions adequately, which lead to dissonant conclusions and interpretations of the data. Quantitative research designs rarely used reliable, valid measurement tools to collect data and failed to acknowledge confounding factors.

Three limitations are acknowledged in this systematic review. Firstly, it is limited by the quality of eligible studies. Further research involving changes in knowledge and the educators' perspective are warranted to fully understand the effectiveness of undergraduate education in telehealth. Secondly, the search term ‘allied health students’ might have led to an unintentional exclusion of relevant papers focussing on individual professional groups within the allied health professions. Thirdly, the strict limitations to teleconsultation did not report on education in the broader realm of telehealth. Including general training in telehealth without a necessary connection to teleconsultation could have resulted in a greater number of studies.

5. CONCLUSION

As the use of telehealth increases, it has become more important to educate and prepare the future workforce. This review summarised current approaches in teleconsultation education for undergraduate health care and social work students. Attention must be drawn to the limited evidence to guide how this education could be implemented in health care and social work education and how effective this education is and its impact on healthcare practice in general as well as interprofessional collaborative practice. More international, interprofessional research on effective implementation of teleconsultation education in undergraduate health care and social work programmes is warranted. The diverse and emerging nature of teleconsultation education suggests that the development of a standard curriculum, informed by the findings of this review and the views of educators and students, may benefit the sector more broadly.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

An ethics approval is not necessary because it is a literature review only with no animals or humans involved.

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors have no acknowledgement to disclose.

Wetzlmair L‐C, O'Carroll V, O'Malley AS, Murray S. Teleconsultation in health and social care professions education: A systematic review. Clin Teach. 2022;19(5):e13519. 10.1111/tct.13519

Funding information The review was initially funded by the University of St Andrews, School of Medicine.

Funding information University of St Andrews, School of Medicine

REFERENCES

- 1. World Heatlh Organisation . Recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening World Health Organization; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wade V, Karnon J, Elshaug A. A systematic review of economic analyses of telehealth services using real time video communication. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:233. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organisation . WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Car J, Koh GC‐H, Foong PS, Wang CJ. Video consultations in primary and specialist care during the COVID‐19 pandemic and beyond. BMJ. 2020;371:m3945. 10.1136/bmj.m3945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bashshur R, Doarn CR, Frenk JM, Kvedar JC, Woolliscroft JO. Telemedicine and the COVID‐19 pandemic, lessons for the future. Telemed E‐Health. 2020;26:571. 10.1089/tmj.2020.29040.rb-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisk M, Livingstone A, Pit SW. Telehealth in the context of COVID‐19: changing perspectives in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e19264. 10.2196/19264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nazeha N, Pavagadhi D, Kyaw BM, Car J, Jimenez G, Tudor Car L. Digitally competent health workforce: a scoping review of educational frameworks (Preprint). J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e22706. 10.2196/22706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Topol E. The Topol Review: preparing the healthcare workforce to deliver the digital future England: Health Education England; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edirippulige S, Armfield NR. Education and training to support the use of clinical telehealth: a review of the literature. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:273–82. 10.1177/1357633x16632968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chandrashekar P. A digital health preclinical requirement for medical students. Acad Med. 2019;94:749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners . Guide to providing telephone and video consultations in general practice Melbourne; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tudor Car L, Kyaw BM, Nannan Panday RS, van der Kleij R, Chavannes N, Majeed A, et al. Digital health training programs for medical students: scoping review. JMIR Med Educ. 2021;7:e28275. 10.2196/28275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Waseh S, Dicker AP. Telemedicine training in undergraduate medical education: mixed‐methods review. JMIR Med Educ. 2019;5:e12515. 10.2196/12515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lizarondo L, Stern C, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, et al. Chapter 8: mixed methods systematic reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors JBI manual for evidence synthesis JBI; 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Booth A. Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech. 2006;24:355–68. 10.1108/07378830610692127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abraham HN, Opara IN, Dwaihy RL, Acuff C, Brauer B, Nabaty R, et al. Engaging third‐year medical students on their internal medicine clerkship in telehealth during COVID‐19. Cureus. 2020;12:e8791. 10.7759/cureus.8791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bulik RJ, Shokar GS. Integrating telemedicine instruction into the curriculum: expanding student perspectives of the scope of clinical practice. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16:355–8. 10.1258/jtt.2010.090910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cantone RE, Palmer R, Dodson LG, Biagioli FE. Insomnia telemedicine OSCE (TeleOSCE): a simulated standardized patient video‐visit case for clerkship students. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10867. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Christner JG, Stansfield RB, Schiller JH, Madenci A, Keefer PM, Pituch K. Use of simulated electronic mail (e‐mail) to assess medical student knowledge, professionalism, and communication skills. Acad Med. 2010;85:S1–4. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed45f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dzara K, Sarver J, Bennett JI, Basnet P. Resident and medical student viewpoints on their participation in a telepsychiatry rotation. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37:214–6. 10.1176/appi.ap.12050101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mulcare M, Naik N, Greenwald P, Schullstrom K, Gogia K, Clark S, et al. Advanced communication and examination skills in telemedicine: a structured simulation‐based course for medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:11047. 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palmer RT, Biagioli FE, Mujcic J, Schneider BN, Spires L, Dodson LG, et al. The feasibility and acceptability of administering a telemedicine objective structured clinical exam as a solution for providing equivalent education to remote and rural learners. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:3399–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palmer RT, Rdesinski RE, Galper A, Cantone RE, Shaver J, Symkowick M, et al. Assessing the impact of a telemedicine simultation on clinical learners. J Family Med Community Health. 2017;4:1120–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edirippulige S, Smith AC, Armfield NR, Bensink M, Wootton R. Student perceptions of a hands‐on practicum to supplement an online eHealth course. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e182. 10.2196/jmir.2029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rienits H, Teuss G, Bonney A. Teaching telehealth consultation skills. Clin Teach. 2016;13:119–23. 10.1111/tct.12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Darnton R, Lopez T, Anil M, Ferdinand J, Jenkins M. Medical students consulting from home: a qualitative evaluation of a tool for maintaining student exposure to patients during lockdown. Med Teach. 2020:160–7. 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1829576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fisher J, Martin R, Tate D. Hands on + hands free: simulated on‐call interaction. Clin Teach. 2014;11:425–8. 10.1111/tct.12180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waschkau A, Götz K, Steinhäuser J. Fit for the future: development of a seminar on aspects of digitization of healthcare as a contribution of medical sociology. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen. 2020;155:48–53. 10.1016/j.zefq.2020.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jimenez‐Rodriguez D, Arrogante O. Simulated video consultations as a learning tool in undergraduate nursing: students' perceptions. Healthcare. 2020;8:280–92. 10.3390/healthcare8030280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bearman M, Palermo C, Allen LM, Williams B. Learning empathy through simulation: a systematic literature review. Simul Healthc. 2015;10:308–19. 10.1097/sih.0000000000000113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee J, Kim H, Kim KH, Jung D, Jowsey T, Webster CS. Effective virtual patient simulators for medical communication training: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2020;54:786–95. 10.1111/medu.14152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dow N, Wass V, Macleod D, Muirhead L, McKeown J. ‘GP Live’‐recorded general practice consultations as a learning tool for junior medical students faced with the COVID‐19 pandemic restrictions. Educ Prim Care. 2020:1–5. 10.1080/14739879.2020.1812440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dost S, Hossain A, Shehab M, Abdelwahed A, Al‐Nusair L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a national cross‐sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e042378. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cain R, Shafer Klink D, Yunus S. Telemedicine implementation in family medicine: undergraduate clerkship during COVID‐19 pandemic. Med Educ. 2020;54:1064–5. 10.1111/medu.14313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Newcomb AB, Duval M, Bachman SL, Mohess D, Dort J, Kapadia MR. Building rapport and earning the surgical patient's trust in the era of social distancing: teaching patient‐centered communication during video conference encounters to medical students. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:336–41. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sharma R, Nachum S, Davidson KW, Nochomovitz M. It's not just FaceTime: core competencies for the Medical Virtualist. Int J Emerg Med. 2019;12:8. 10.1186/s12245-019-0226-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hills C, Ryan S, Smith DR, Warren‐Forward H, Levett‐Jones T, Lapkin S. Occupational therapy students' technological skills: are ‘generation Y’ ready for 21st century practice? Aust Occup Ther J. 2016;63:391–8. 10.1111/1440-1630.12308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Poncette AS, Glauert DL, Mosch L, Braune K, Balzer F, Back DA. Undergraduate medical competencies in digital health and curricular module development: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e22161. 10.2196/22161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wentink MM, Siemonsma PC, Van Bodegom‐Vos L, de Kloet AJ, Verhoef J, Vlieland TPMV, et al. Teachers' and students' perceptions on barriers and facilitators for eHealth education in the curriculum of functional exercise and physical therapy: a focus groups study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19. 10.1186/s12909-019-1778-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information S1