Abstract

Aim

Globally, type 2 diabetes care is often fragmented and still organised in a provider‐centred way, resulting in suboptimal care for many individuals. As healthcare systems seek to implement digital care innovations, it is timely to reassess stakeholders' priorities to guide the redesign of diabetes care. This study aimed to identify the needs and wishes of people with type 2 diabetes, and specialist and primary care teams regarding optimal diabetes care to explore how to better support people with diabetes in a metropolitan healthcare service in Australia.

Methods

Our project was guided by a Participatory Design approach and this paper reports part of the first step, identification of needs. We conducted four focus groups and 16 interviews (November 2019–January 2020) with 17 adults with type 2 diabetes and seven specialist clinicians from a diabetes outpatient clinic in Brisbane, Australia, and seven primary care professionals from different clinics in Brisbane. Data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis, building on the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour model.

Results

People with diabetes expressed the wish to be equipped, supported and recognised for their efforts in a holistic way, receive personalised care at the right time and improved access to connected services. Healthcare professionals agreed and expressed their own burden regarding their challenging work. Overall, both groups desired holistic, personalised, supportive, proactive and coordinated care pathways.

Conclusions

We conclude that there is an alignment of the perceived needs and wishes for improved diabetes care among key stakeholders, however, important gaps remain in the healthcare system.

Keywords: care pathways, healthcare delivery, participatory design, qualitative research, self‐management, type 2 diabetes mellitus

NOVELTY STATEMENT.

What is already known? What this study has found? What are the clinical implications of the study?

The importance of person‐centred and integrated diabetes care is well recognised. However, diabetes care is often fragmented, resulting in suboptimal support. As healthcare systems and consumers embark on digitalisation, we believe it is timely to reassess stakeholders' priorities to guide the redesign of diabetes care.

This Participatory Design study found there is an alignment of the perceived needs and wishes for improved type 2 diabetes care among people with diabetes and healthcare professionals, however, important healthcare system gaps remain.

Healthcare pathways could be improved most if holistic, personalised, proactive and coordinated support for people with type 2 diabetes was implemented.

1. INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus care can be complex and requires, among other components, continuous self‐management, multidisciplinary team input and community support. 1 However, its steeply rising prevalence increases pressure on the healthcare system and brings challenges relating to optimising diabetes care. Self‐management of diabetes has been widely recognised as key to achieving better health outcomes. 2 Research also demonstrates that many people with type 2 diabetes (PWD) wish to be more actively engaged in their own care and live their life as independently as possible. 3 , 4

A scoping review by the World Health Organization (2016) on integrated care models proposed an explicit focus on the needs of the individuals and self‐management. 5 It defined integrated care as an approach to support person‐centred healthcare systems by the delivery of services designed according to the multidimensional needs of the individuals and delivered by a coordinated multidisciplinary team working across different settings and levels of care.

There has been a gradual, albeit slow, shift in medical approach over the years leading organisations to implement person‐centred models, that are respectful and trusting and take into consideration PWD values and preferences as well as shared decision making, including models developed in Australia. 6 , 7 These have shown to be clinically effective with enhanced PWD satisfaction and self‐management engagement and decreased health service utilisation.

Despite all recent efforts, worldwide, models of diabetes care are still considered fragmented and provider‐centred, with many PWD not meeting diabetes management targets. 8 In Australia, non‐coordinated contributions from primary and specialist healthcare professionals (HCPs) are common, leading to duplication, resource wastage and PWD dissatisfaction. 9 , 10 More than half of Australians living with type 2 diabetes still do not meet management targets and only half achieve recommended glycaemic targets. 11

New technologies offer the opportunity to facilitate a redesign of the fragmented diabetes care by improving linkages between main stakeholders and access to services. 1 PWD also recognise their potential to assist diabetes self‐management. 12 As healthcare systems and stakeholders, including health consumers, embrace digitalisation, we believe it is important and timely to review stakeholders' priorities.

Stakeholder involvement is fundamental in redesigning diabetes care to promote PWD and provider activation for sustainable change. Growing evidence suggests that involving PWD leads to better care, improved quality of life and reduced health service utilisation by developing strategies aligned with their needs. 13 Furthermore, HCPs must also guide and be willing to implement new care pathways, since a revision of workflows may be needed. Consequently, this study undertook essential stakeholders' consultation to redesign type 2 diabetes care using Participatory Design. This method has been proven valuable in healthcare redesign and development of sustainable practical solutions 14 by actively involving stakeholders in the design process. The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour (COM‐B) model describes behaviours, in this case the management of type 2 diabetes, as the result of interactions between: knowledge and skills (Capability); social and physical environment (Opportunity) and emotions and plans (Motivation). COM‐B was used to organise the data collection and analysis 15 as optimising type 2 diabetes management requires individual and collective behaviour change in the complex environmental context of healthcare services. 16

1.1. Aim

This study aimed to identify the needs and wishes of PWD, and specialist and primary care teams regarding optimal type 2 diabetes care to explore how to better support PWD in a metropolitan healthcare service in Australia.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participatory Design

This project was guided by a Participatory Design approach, a user‐centred methodology originated from action research, which provides concerned parties the opportunity to contribute to the definition of a problem, its source and solutions. 3

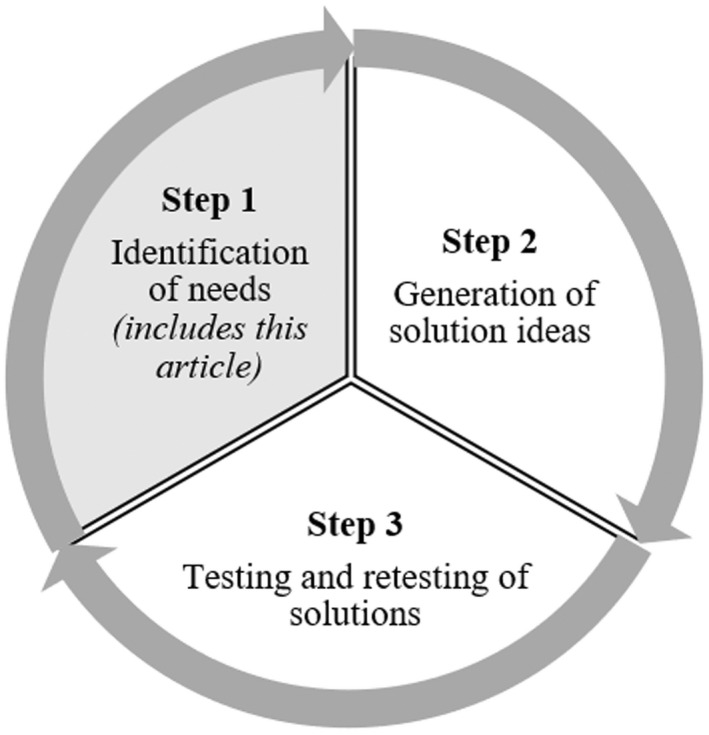

The project involved a three‐step iterative process: (1) identification of needs, (2) generation of solution ideas and (3) testing and retesting of solutions (Figure 1). All steps were guided by key stakeholders' contributions, and information uncovered at each step influenced the next until a solution was designed and endorsed by all. Step 1 included a literature review, published separately as a systematic review, 17 and review of grey literature. This article reports the subsequent part of step 1—focus groups and interviews with stakeholders. The solutions and care pathways generated in steps 2 and 3 will be reported separately.

FIGURE 1.

Participatory Design steps

2.2. Recruitment of participants

All PWD participants resided in Southeast Queensland, Australia, and were recruited at the Princess Alexandra Hospital (PAH) specialist diabetes outpatient clinic in Brisbane. Participants were 18 years or older, able to understand spoken and written English, and physically and mentally capable of participating in the study. The diabetes educators at the clinic informed PWD attending an appointment of the study and one researcher (DB) regularly visited the clinic to provide more information to those interested and manage consent and enrolment.

All specialist HCPs were staff members of the PAH diabetes clinic. Specialist diabetes teams include endocrinologists, diabetes educators and dietitians, among others. PWD who have complex diabetes beyond the perceived management capacity of the primary care practitioner are commonly referred to such services for additional support. The principal investigator and clinic director (AR) informed all team members about the study and a researcher (DB) approached them when visiting the clinic, outlining project details and managing consent and enrolment if interested. Primary HCPs were recruited at an external primary care network seminar and via snowball from various clinics in Brisbane.

Recruitment ceased when the sample held enough information power and new insights about the topic, considering the study aim, the use of an established framework and quality of information obtained. 18 This was assessed continuously along the data collection process and initial data analysis.

2.3. Ethical considerations

All participants gave informed consent prior to participation. The project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Metro South Hospital and Health Service and The University of Queensland (reference number: HREC/2018/QMS/48462).

2.4. Data collection

We first identified reported needs of PWD and HCPs through a literature review, 17 which supported the preparation of the semi‐structured focus group and interview guide (Appendix A). Two researchers (DB and MJ) trained in qualitative research conducted and audio‐recorded the interviews and focus groups between November 2019 and January 2020. They had no personal or professional clinical relationship with the participants. Focus groups with PWD were conducted in a casual university space and interviews and focus groups with HCPs were conducted in hospital campus meeting rooms. Individual interviews by phone or videoconference were used with participants not willing or able to participate in group discussions, due to time availability, distance, mobility or a dislike for sharing ideas in groups.

Participants completed a short questionnaire: basic demographics, diabetes duration and treatment for PWD, and professional role and experience working with PWD for HCPs. Participants were offered reimbursement of their travel cost and a grocery voucher to thank them for their time.

2.5. Data analysis

Audio‐recordings were transcribed verbatim and de‐identified transcripts were analysed using NVivo 12 software applying the six phases of reflexive thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke, by following a process of analysing text for recurring patterns. 19 , 20 This method was used because we wanted to critically engage with the data in an organic and iterative way and be able to identify unexpected patterns, without the use of fixed coding frames, apart from the use of a theory of behaviour change to organise the initial coding. 20 We, therefore, applied both deductive and inductive thematic analysis to interpret and describe the data by two researchers (CS and DB). DB has many years of experience in diabetes self‐management research and case management and CS has training in health promotion. When needed, themes and subthemes were discussed with a third researcher experienced in qualitative analysis (MJ).

Before the initial coding, transcripts were read thoroughly to capture an overall impression of the data (Phase 1—‘familiarisation’).

In the coding process, the first coder (CS) initially deductively analysed the transcripts using the COM‐B model to organise the data 15 and later used an inductive approach to explore latent content of the result of the first step. Here, sections of the text were labelled with codes to describe their meaning (Phase 2—‘generating codes’). In a final step, codes were then organised and categorised into main themes and subthemes according to similar patterns (Phase 3–5—‘searching, reviewing and defining themes’).

The second coder (DB) performed independently the steps previously described using 10% of the data to identify and discuss possible personal assumptions and omissions. Both coders then reviewed together all themes, subthemes and quotes and summarised them in tables (Phase 6—‘producing the report’). Data from PWD and HCPs were analysed separately. One participant with diabetes reviewed the wording to report the themes and sub‐themes to check if it was still representative of PWD's views.

2.6. Participants

In total, 17 participants with diabetes contributed to our study. Seven participated in two focus groups (three to four participants each) and 10 participated in individual phone or videoconference interviews (Table 1 and Appendix B). The median age was 61 years (range 34–74) and there was gender balance. Most of the participants had completed a trade, technical certificate, diploma or less (94%, n = 16/17). The time since the participants' diagnosis varied from 5 to 45 years (median 19 years). All participants took antihyperglycaemic medications (71% oral medications, 77% insulin, 6% injectables—non‐insulin).

TABLE 1.

PWD demographics and diabetes duration and treatment

| Demographics and diabetes diagnosis and treatment | n (%) or median (range) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61 (34–74) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 8 (47%) |

| Male | 9 (53%) |

| Education | |

| Year 8–10 | 2 (12%) |

| High school | 5 (29%) |

| Trade or technical certificate or diploma | 9 (53%) |

| Undergraduate degree | 1 (6%) |

| Living arrangements | |

| Alone | 6 (35%) |

| Spouse/partner/other family members/friends | 11 (65%) |

| Employment | |

| Employed, full‐time or part‐time | 7 (41%) |

| Unemployed | 5 (30%) |

| Retired | 5 (29%) |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity | |

| Yes | 1 (6%) |

| No | 16 (94%) |

| Years since diagnosis | 19 (5–45) |

| Treatment | |

| Any medication | 17 (100%) |

| Oral antihyperglycaemic | 12 (71%) |

| Injectables—non‐insulin | 1 (6%) |

| Insulin | 13 (76%) |

Fourteen HCPs from primary (n = 7) and specialised care (n = 7) took part (Table 2 and Appendix B). One focus group included three GPs and one practice nurse and the other included three specialist HCPs (two endocrinologists and one allied health), and one primary care diabetes educator. The latter participant also took part in a follow‐up individual interview as she had arrived late for the focus group. Two specialist diabetes educators participated in an interview together. The remaining HCPs (n = 4) took part in single interviews. The HCPs' median number of years of experience working with diabetes was 10.5 (range 5–26) and on average they saw 15 PWD per week (range 1–90).

TABLE 2.

HCPs' demographics, professional role and experience

| Demographics, professional role and experience | n (%) or median (range) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 25–34 | 3 (21%) |

| 35–64 | 11 (79%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 9 (64%) |

| Male | 5 (36%) |

| Role | |

| Primary care | 7 (50%) |

| General practitioner | 5 (36%) |

| Diabetes educator | 1 (7%) |

| General practice nurse | 1 (7%) |

| Specialised care | 7 (50%) |

| Endocrinologist | 2 (14%) |

| Diabetes educator | 3 (21%) |

| Allied healthcare professional | 2 (14%) |

| Setting | |

| General practice clinic | 6 (43%) |

| Hospital | 7 (50%) |

| Hospital and general practice clinic | 1 (7%) |

| Primary care clinics with multidisciplinary focus | 3 (43%) |

| Years working with type 2 diabetes patients | 10.5 (5–26) |

| Type 2 diabetes patient consultations per week | 15 (1–90) |

3. RESULTS

Views about diabetes management from HCPs and PWD are presented in three tables according to components of the COM‐B model: Capability (Table 3), Opportunity (Table 4) and Motivation (Table 5). Main themes from both groups often overlapped and are presented combined reporting the PWD sub‐themes (views about their situation and how diabetes care and HCPs could better support them) and HCP sub‐themes (views about PWD situation and how diabetes care and HCPs' activity could better support PWD). One separate theme was identified in the HCPs analysis in relation to their own needs and this is reported separately. Illustrative quotes representative of each main theme are presented in Appendix C.

TABLE 3.

Themes and sub‐themes pertaining to knowledge and skills (COM‐B header Capability)

| Main themes | PWD sub‐themes | HCPs sub‐themes (views about PWD situation and how HCPs' activity could better support PWD) |

|---|---|---|

| Capability | ||

| More knowledge, information and skills | More knowledge about diabetes and long‐term impact—early and individualised way | More PWD's knowledge about diabetes and complications—newly diagnosed |

| More knowledge about food choices and preparation, medication, and blood glucose monitoring | More PWD's knowledge about self‐management | |

| More access to tailored, comprehensive, clear and up to date information including via online and mobile resources | More access to tailored, comprehensive, clear and up to date information for PWD using technology | |

| Skills to apply knowledge and make more complex decisions | ||

TABLE 4.

Themes and sub‐themes pertaining to physical and social environment (COM‐B header Opportunity)

| Main themes | PWD sub‐themes | HCPs sub‐themes (views about PWD situation and how HCPs' activity could better support PWD) |

|---|---|---|

| Opportunity | ||

| Social support—family, friends and other PWD | Include family in diabetes care | PWD making changes as a family |

| Learn from others—successful examples are good motivators | PWD to share experiences | |

| Online social support | ||

| Community resources | ‘Wellness centre’ and community meetings | Available community resources for PWD |

| Themes and sub‐themes focused on diabetes care service provision: | ||

| Holistic approach | ‘Main thing is the wellness aspect’ | PWD's physical and mental wellbeing |

| More than just weight and medication | ‘More than just numbers and glucose’ | |

| More personalisation | HCPs remembering preferences and personal achievements | HCPs remembering personal activities and personal achievements |

| Personalised goals and plans—acknowledge what they can do | HCPs understanding PWD preferences, needs and limitations | |

| Support and encouragement from HCPs | Good relationship with HCPs | PWD and HCPs relationship and rapport |

| Feeling more than just a number | PWD feeling valued and HCPs non‐judgemental language | |

| Shared decision making | Ownership of diabetes care and professional role | |

| More coordination | More communication and collaboration between all HCPs | HCPs team‐based approach (including prompt advice for primary care) |

| Shared health care data | Shared health care data | |

| Care coordinator—one person for all of your diabetes assistance | Case manager—one point of contact, an advocate | |

| ‘Wellness centre’—a casual place with all services under the same roof | ‘Super clinic’—all services under the same roof, always the same HCPs | |

| Proactive assistance | Genuine focus on prevention | More focus on secondary prevention |

| ‘Accountability’—someone watching health data | Monitoring health data, including remotely | |

| Prompt access and someone to contact | Prompt care | |

| Regular support with a long‐term perspective | Regular and long‐term care | |

| Improve access using technology | Increase use of telehealth | |

TABLE 5.

Themes and sub‐themes pertaining to emotions, evaluations and plans (COM‐B header Motivation)

| Main themes | PWD sub‐themes | HCPs sub‐themes (views about PWD situation and how HCPs' activity could better support PWD) |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation | ||

| Emotions and burden of living with diabetes | Shock, denial and fear at diagnosis | PWD's struggle with diagnosis and lifestyle changes |

| Frustration, anger, guilt, stigma | PWD's depression, anxiety, distress, social stigma | |

| ‘It's your fault’—feelings of being judged | Avoid ‘shaming’—HCPs finding the best communication language | |

| Beliefs and motivation to manage diabetes | ‘It's not that serious yet’ | Often only when symptoms appear, PWD realise the seriousness of diabetes |

| Feelings of not being able to manage diabetes or change behaviours | Make PWD believe they can manage their diabetes | |

| It is difficult to get motivated |

Lack of PWD's motivation as main barrier Emphasis on PWD's engagement |

|

| Plans and goals | Monitoring, keeping records and reminders | Monitoring and keeping records |

| Diabetes impacts on daily routine and hard to maintain new routine | ‘No holidays’—PWD's constant self‐management | |

3.1. Knowledge and skills (COM‐B header Capability)

Themes under knowledge and skills impacting ‘Capability’ to best manage diabetes related to obtaining and providing to PWD detailed and tailored information and skills, which were considered essential for good diabetes self‐management and motivation.

PWD expressed the need for individualised information about the seriousness of diabetes early on. One person with diabetes mentioned:

Because I really went untreated with my diabetes for a long time because I didn't realise just how serious it was (aged 46, 6 years since diagnosis)

PWD found it challenging to obtain sufficient information about diabetes management, especially how to make good food choices:

I just found I was hitting my head against the wall sometimes trying to get information (aged 56, 5 years since diagnosis)

For that whole time, I've never been given the tools to control it myself (aged 47, 5 years since diagnosis)

Both groups agreed that there is a clear need for more personalised information and better ways of delivering it. HCPs highlighted the requirement to assess PWD needs before providing information.

3.2. Physical and social environment (COM‐B header Opportunity)

Themes under physical and social environment mainly related to social support, community‐delivered resources and diabetes healthcare service provision preferences.

Both groups mentioned that support from family, friends and other PWD is important and learning from other PWD successful examples is helpful and referred to the importance of community resources to support diabetes management. PWD wished for a place where everything needed for diabetes care would be provided under the same roof, described as a "wellness centre" (aged 60, 30 years since diagnosis), where they can also meet other people to share experiences:

Like community meetings where you can talk to people who have lost weight, got foot issues, GP issues (aged 70, 21 years since diagnosis).

Regarding diabetes care service provision, both groups referred to the importance of a holistic approach, by which individuals in their whole and their well‐being are considered, not just their blood glucose levels, medications or weight. PWD mentioned that “the main thing is the wellness aspect, you want to feel good” (aged 60, 30 years since diagnosis) “rather than, ‘you've got diabetes, give you a bit of script, off you go, we'll have a HbA1c in three months” (aged 60, 20 years since diagnosis).

PWD and HCPs agreed there is a need for more personalisation in service provision. They mentioned that, when working together to set goals, it is important to recognise that each individual has different needs and to “acknowledge the things that you can do” (person with diabetes aged 70, 21 years since diagnosis). One primary HCP highlighted the importance of "understanding your patients, how they live, talking to them about it, but also then also working with them about setting healthy goals" (26 years' experience)

Both groups emphasised the importance of HCPs support, which includes good rapport, non‐judgemental language and encouragement and HCPs making PWD feel valued and more than just a number.

It's like you're in a deli with a ticket, it's like, ‘now serving number 15’ (person with diabetes aged 47, 20 years since diagnosis).

Participants stated the value of shared decision making in diabetes care. One person with diabetes highlighted that HCPs should "treat you as a partner, because it's a shared thing. They've got knowledge that you want, and you've got experience that only you can give them to let them know how to treat your individual case" (aged 61, 19 years since diagnosis)

PWD and HCPs often mentioned the importance of having one HCP responsible for the diabetes care plan, referred to by HCPs as a “case manager”. This should be one person whom PWD can access for all diabetes assistance, someone who knows them well and an advocate. Both groups wished for more coordination, asking for more "logical" and less "disjointed" care. They frequently indicated that a knowledgeable GP is essential for coordinated care and that GP should be able to have prompt access to specialist advice. Participants also revealed the need for shared health care data and negative consequences from their absence, such as PWD frustration about poor acknowledgement of previous efforts.

Both groups stated the value of preventive and readily accessible care—receiving answers promptly and having someone monitoring health data.

I need that accountability. I find it more comfortable and satisfying that I know someone is there and if something suddenly happens then I'm able to get to help immediately. (person with diabetes aged 64, 8 years since diagnosis).

Participants referred to the potential of technology and suggested:

Online social support;

Remote monitoring, prompt care and reminders using technology;

Telehealth consultations to improve access;

Phone hotline and videoconferencing to enable GP access to diabetes specialist teams.

3.3. Emotions, evaluations and plans (COM‐B header Motivation)

Both groups often related to how emotions and beliefs positively or negatively impact on motivation to manage diabetes and the importance of tailored plans and goals. Specifically, PWD and HCPs mentioned that the many barriers PWD experience in their daily life often lead to negative emotions such as frustration and anger and that lack of motivation is common. Several HCPs referred to the importance of encouraging PWD engagement:

I think the missed part of that is still engaging patients. And, encouraging them to change lifestyles. And, I think involving them in their care (primary HCP, 14 years' experience)

However, feelings of not being able to manage diabetes or change behaviours were often expressed by PWD:

Why bother if it's not working (aged 46, 6 years since diagnosis)

One main perceived barrier was the emotional impact of being judged. PWD felt that other people's and HCPs' communication was sometimes judgemental and previous achievements infrequently recognised. One person with diabetes stated:

I thought it is frustrating because you're being given this tag, ‘You're a diabetic’. He [husband with diabetes] was made to feel that he was a bad person because he allowed it to happen (aged 64, 13 years since diagnosis)

HCPs expressed the struggle and the need to find the best language to communicate and avoid shaming.

Language is very important or dismissive language, saying, ‘you're fat’, or, ‘you're obese and you need to lose weight’, so shaming the patient or confronting the patient negatively I don't think is a healthy option (primary HCP, 26 years' experience)

PWD expressed their difficulty of integrating diabetes self‐management into their everyday routines, citing the burden of blood glucose monitoring and medication. Both groups agreed on the importance of collaborating towards tailored goals and plans, and monitoring them.

3.4. HCPs' own burden and needs

One theme identified in the HCP analysis not mentioned by PWD was the ‘HCPs’ challenging work’. HCPs revealed how their inability ‘to do more’ and motivate PWD also affects their own emotions and motivation, revealing it as "very frustrating" and "not easy". HCPs also reported their own barriers caused by the health services' funding system and diabetes management plans, such as time restrictions. They also raised the challenges to keep up to date with new treatments and guidelines.

We just don't seem to get the time to do it because we're too busy (specialist HCP, 11 years' experience)

4. DISCUSSION

Our team conducted focus groups and interviews with PWD and HCPs to obtain their experiences and views on optimal diabetes care. The growing availability and adoption of new technologies may offer opportunities not available in the past to support unmet needs, thus we believe it is timely to review stakeholders' priorities. Therefore, this study aimed to analyse the needs of stakeholders to later, explore creative solutions in the next steps of this project.

PWD expressed the need to be better equipped, supported and recognised for their efforts in a holistic way, receive personalised care at the right time, including tailored information, and improved access to connected services. HCPs agreed with the needs of PWD and further expressed their own burden regarding their challenging work. Overall, PWD and HCPs wished for holistic, personalised, supportive, proactive and coordinated care pathways.

Similarly to these findings, a systematic review conducted by our team concluded that generally both groups have similar views about components of diabetes care, but HCPs struggle to meet PWD's holistic needs. 17 This demonstrates that there is an alignment of the perceived needs for improved diabetes care among main stakeholders, however, important gaps still remain. Other studies have identified gaps between what stakeholders wish for and what healthcare systems deliver. 21 , 22 Jensen et al. used a lifeworld theoretical perspective to understand the gap in hip fracture management in a Danish hospital and concluded that care was not giving voice to patients' social and subjective worlds and the biomedical discourse was dominating their interactions. 21 Similarly, in our study some participants mentioned that HCPs should focus on overall well‐being and not only on blood glucose levels, medication and weight, indicating a need for a more holistic approach to care.

Both groups often referred to the burden of diabetes and its negative effect on emotional well‐being, highlighting the importance of acknowledging the challenges faced. Poor mental health and diabetes distress affect approximately 40% of Australians living with diabetes, however, they are inadequately accounted for in current models. 23 Another Australian study also found that PWD felt that the psychological impact of living with diabetes was not heard, that care should focus not only on HbA1c levels, and that they were not being involved enough in their care. 24 Accordingly, in our study PWD themselves emphasised the wish to be empowered and HCPs want to support this independence. However, PWD mentioned that they are not being provided with the tools and education to manage their diabetes. Collaboration for the development of personalised care plans and goals is also important to actively involve PWD in their own care 25 and is associated with better outcomes, as they have the lived experience to care for their own individual needs.

Both groups acknowledged the importance of non‐judgmental language, however, language is still being perceived as judgemental by PWD and a challenge by HCPs, who struggled to find the appropriate way to communicate. Language that judges and shames may add to the burden of living with diabetes and undermine current efforts. 26 Recently, the American Diabetes Association called for empowering language that is neutral, fact‐based and stigma‐free. 26

PWD not only mentioned the need to have the knowledge and skills to manage diabetes, they also wished for the skills to apply these to complex decision making, such as balancing efforts towards weight management and good food intake and their impact on blood glucose levels. This was not mentioned by HCPs and there may be a need for HCPs to recognise the importance of supporting PWD in making complex decisions in their individual diabetes management.

PWD engagement also requires providing HCPs with the resources, skills and motivation to empower PWD. 27 Lack of HCPs support may be one of the reasons for the gap between what the stakeholders wish for and what the healthcare system can provide. Reasons expressed by HCPs included lack of time, funding and helpful resources. HCPs often expressed their frustrations about the limitations imposed by the healthcare system. Future care pathways should provide HCPs with the right tools and resources to facilitate person‐centred care, considering their constraints. Medical education and professional development programmes should emphasise this to change HCP culture more broadly.

This study's results provide further evidence of the fragmented care in Australia. Our participants clearly wished for more coordination and communication between HCPs, which per se represent a barrier to person‐centred care, resulting in poor acknowledgment of previous efforts and achievements due to lack of shared health data. Evidence suggests that technology can strengthen coordination between HCPs and shared collaboration between PWD and HCPs. 28 Technology may also support long‐term behaviour change via remote monitoring, regular support and timely feedback 29 and the provision of tailored information to empower PWD. 30 Participants mentioned its advantages, including technology for remote monitoring, and the use of videoconferencing to improve HCPs access to specialised advice, which we believe should be explored further in new diabetes care pathways.

Using the COM‐B model allowed us to explore important components for collective behaviour change to support the management of type 2 diabetes, including, for example, not only PWD's but also HCPs' motivation, which we believe may have been missed without a behaviour change approach. This study gave stakeholders a crucial voice which will guide our design of new care pathways.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our study was reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) checklist. We included HCPs from different settings and roles in diabetes care, to ensure that different perspectives were considered and recruited PWD who had contact with specialist teams and therefore are more likely to have experienced the currently fragmented care.

Individuals who agreed to participate are likely to have a special interest and more awareness about the needs for optimal diabetes care. Therefore, there may be some unaddressed needs. Most of our PWD participants have had type 2 diabetes for many years with more complex diabetes therefore findings may not be representative of the general population, including PWD newly diagnosed or managed by primary care only.

5. CONCLUSION

This paper reports part of the first step of a Participatory Design project to explore stakeholders' needs for optimal type 2 diabetes care. The next steps, including proposed solutions and redesigned care pathways, will be published separately.

We conclude that there is an alignment of the perceived needs for improved diabetes care among PWD and HCPs. Overall, both groups wished for holistic, personalised, supportive, proactive and coordinated care pathways. New care pathways should consider stakeholders' views to address the gaps between their wishes and the healthcare currently provided.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all people with type 2 diabetes and healthcare professionals for participating in our study. This study was supported by the Australian Government's Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) as part of the Rapid Applied Research Translation Program grant through Brisbane Diamantina Health Partners (MRF9100000). MJ is funded by a NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (APP1151021). SCC is funded by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior – Brazil (CAPES), Finance Code 001. FF is supported by the Digital Health Cooperative Research Centre, Australia (DHCRC, Grant No. DHCRC1.1/237886587). AM is funded by a Queensland Advancing Clinical Research Fellowship, Queensland Health. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

APPENDIX A.

Focus group and interview guide—People with type 2 diabetes

Introduction will acknowledge complexity of living with diabetes, requiring daily management tasks, multifaceted management requiring frequent interactions with health services.

Our project is aiming to rethink the way diabetes care is delivered for people living with type 2 diabetes. To this end we are conducting interviews and focus groups (discussion groups) to understand what are the needs of people with type 2 diabetes to best manage this condition. We are speaking with people with type 2 diabetes and with clinicians.

Your diabetes management at present.

What works?

PEOPLE:

Who is of most help to you? (family, peers, healthcare professionals, etc.?) in what way and why.

OTHER RESOURCES:

What supports/support resources do you have?

And what helps?

Any tech tools are of help? If yes: What are they?

What does not work?

Which aspects of the management you are not happy with?

- What issues are you facing? What gets in the way?

- Reported barriers often are:

- access to professionals,

- peers,

- resources,

- costs,

- duplication,

- emotional challenges

- How does this .. aspect which does not work… make you feel?

- (People have mentioned feeling: overwhelmed, powerless, less motivated, scared, stressed, etc.)

If it could be different.

PEOPLE:

- Who could help, if there was no restriction, in an ideal situation? In what way and why? Research mentions

- relationship with healthcare professionals is important,

- communication between healthcare professionals,

- timing of support,

- “focus of support relationship” (just on diabetes numbers, whole person, partnership)

Explore what gets in the way at present to access this support currently (barriers to access to professionals, peers, family support ‐ costs, duplication, emotional challenges)

OTHER RESOURCES:

What could help (to feel better/to manage your diabetes)?

Prompts: what sort of resources:

educational information, monitoring [by whom?],

coaching – goal setting…,

emotional support,

information sharing between parties.

Prompts: what format?

Social support,

services,

technologies,

written information

Focus group and interview guide—Healthcare professionals

Our project is aiming to rethink the way diabetes care is delivered for people living with type 2 diabetes. To this end we are conducting interviews and focus groups (discussion groups) to understand what are the needs of people with type 2 diabetes to best manage this condition. We are speaking with people with type 2 diabetes and with clinicians from the primary care and the specialist teams.

What does a person with type 2 diabetes need to best manage their diabetes? (At each time point during their journey)

Why?

What works?

What does not work?

What barriers are you facing when working to support a person with diabetes manage their condition?

Tips from literature: financial and personal practice levels, cost of care, lack of time, lack of information, etc., communication style, establishing relationship, health literacy, continuity of care

What could help?

Tips from literature: Accessible list of resources, step‐by‐step plan, etc. Integration of services.

APPENDIX B.

| Focus groups/interviews | Participants | Duration (min) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual interviews with PWD | D1, 64 years old, 8 years since diagnosis | 39 |

| D2, 74 years old, 45 years since diagnosis | 38 | |

| D3, 73 years old, 30 years since diagnosis | 35 | |

| D4, 46 years old, 6 years since diagnosis | 33 | |

| D5, 56 years old, 5 years since diagnosis | 41 | |

| D10, 34 years old, 15 years since diagnosis | 35 | |

| D11, 62 years old, 10 years since diagnosis | 14 | |

| D12, 52 years old, 13 years since diagnosis | 46 | |

| D13, 61 years old, 19 years since diagnosis | 40 | |

| D17, 47 years old, 20 years since diagnosis | 50 | |

| Focus groups with PWD | D6, 72 years old, 30 years since diagnosis | 83 |

| D7, 60 years old, 20 years since diagnosis | ||

| D8, 66 years old, 21 years since diagnosis | ||

| D9, 64 years old, 13 years since diagnosis | ||

| D14, 60 years old, 30 years since diagnosis | 70 | |

| D15, 47 years old, 5 years since diagnosis | ||

| D16, 70 years old, 21 years since diagnosis | ||

| Individual interviews with HCPs | GP1, general practitioner, primary care | 14 |

| DE1, diabetes educator, specialist care | 39 | |

| AH1, allied healthcare professional, specialist care | 48 | |

| DE2, diabetes educator, primary care* | 33 | |

| GP5, general practitioner, primary care | 31 | |

| Dual interview with HCPs | DE3, diabetes educator, specialist care | 35 |

| DE4, diabetes educator, specialist care | ||

| Focus groups with HCPs | GP2, general practitioner, primary care | 66 |

| GP3, general practitioner, primary care | ||

| GP4, general practitioner, primary care | ||

| PN1, general practice nurse, primary care | ||

| EN1, endocrinologist, specialist care | 48 | |

| EN2, endocrinologist, specialist care | ||

| AH2, allied healthcare professional, specialist care | ||

| DE2, diabetes educator, primary care* |

*The same HCP participated in a focus group and a follow‐up interview.

APPENDIX C.

| Quotes pertaining to knowledge and skills (COM‐B header Capability) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main themes | PWD quotes | HCPs quotes |

| More knowledge, information and skills |

“Because I really went untreated with my diabetes for a long time because I did not realise just how serious it was” (aged 46, 6 years since diagnosis) “Maybe even a short video of something that you can be recommended to watch, maybe somebody who's had amputations, or gangrene in the feet, or something that's going to shock you into action” (aged 52, 13 years since diagnosis) “I just found I was hitting my head against the wall sometimes trying to get information. (…) When your diabetes is a little bit hard to control or is anything other than the norm, there was nowhere to go to get general information” (aged 56, 5 years since diagnosis) “For that whole time, I've never been given the tools to control it myself” (aged 47, 5 years since diagnosis) “Because really, I had no idea of what to avoid. I just thought sugar was sugar. I had no idea that fruit could affect your sugar. I had no idea that carbohydrates turn to sugars. (…) And it all comes back to, like I said, education. I was uneducated on the whole food and the values of food” (aged 46, 6 years since diagnosis) “Information when you need it would be great. It could be phone, it could be in person, it could be chat room” (aged 64, 13 years since diagnosis) “I just think in general, we have got all this new technology and there's got to be better ways to get the information across” (aged 56, 5 years since diagnosis) |

“And, I think that's still lacking, unfortunately, I think there's just not enough information out there for people to say – if you get in early, these are the things that you can achieve” (specialist HCP, 19 years' experience) “If you have got the skills and you can give them those skills and the knowledge to back it all up and to help them make those changes then you can actually get some very good results” (specialist HCP, 11 years' experience).” “A lot of patients would come on who are quite educated people, but they'd essentially been diagnosed with diabetes and put on medications and never been given any of the dietary advice or lifestyle advice (…) no one had ever told them that if they changed their diet and did some exercise, that their diabetes control would be better” (specialist HCP, 12 years' experience) “They do not want to be told what they already know (…) It might almost be useful for the patients to have a little form that they fill in before they see us to say, ‘Which of these things do you think you would like more information about today?’ and tick the box” (specialist HCP, 6 years' experience) “I think, there’s a lot of education we do that you don’t actually have to be a person to do it so I think we could actually get away with a lot more education as videos, like, training videos and stuff which can provide the basics of all the diabetes education and then you come in and see for the specific stuff” (specialist HCP, 11 years’ experience) |

| Quotes pertaining to physical and social environment (COM‐B header Opportunity) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main themes | PWD quotes | HCPs quotes |

| Social support—Family, friends and other PWD |

“I've got support from my family, and my partner, she supports, obviously, my healthiness, she's been through some pretty hard times with me” (aged 34, 15 years since diagnosis) “I have family. I have neighbours. I have friends who all support in one way or another” (aged 64, 8 years since diagnosis) “This might seem a bit intrusive, but somebody that comes and knocks on your door three times a week, or whatever, and says, “Righto, let us go for a walk” (aged 52, 13 years since diagnosis) “It's good to hear other people, not just from medical staff but what's working for them and what's not working, because not all the time what the medical profession give you is useful for you” (aged 46, 6 years since diagnosis) “But, listening to them, motivates you, it helps you think it's possible.” (aged 70, 21 years since diagnosis) |

“Patients have got good supports around them, their family, GPs, good team and they are using those to address what they need to address and make changes that they need to change and having the support to maintain them” (…) So, it's engaging the family in amongst that to say well, if you need to be healthier, we are going to be healthier, we are going to make whole family changes from diet, exercise, lifestyle, all those sorts of stress management plans” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) “Finding out what sort of support they have got around them to help motivate them between because obviously we are only seeing them once every three months, so kind of finding what sources of support they have got at home to help them with their daily motivation or asking them if they want to bring in a partner or children or anything into the consultation to help them remember information that helps when doing those things” (specialist HCP, 8 years' experience) |

| Community resources |

“Like community meetings where you can talk to people who have lost weight, got foot issues, GP issues, with somebody with the authority to say somebody needs attention here, who can take notes and follow up” (aged 70, 21 years since diagnosis) “I actually think that regular group community sessions you can go to that are facilitated where you can get ideas (…) Where you have got professionals who are going to listen, at least somebody representing from the clinic or something, that's going to sit there and prepare to cop it.” (aged 47, 5 years since diagnosis) Another interviewee from the same focus group: “See, that would be part of a wellness centre, too” (aged 60, 30 years since diagnosis) |

“Whether or not there's community resources that are available that might help them to tackle some of those lifestyle factors. Ways of engaging their families to support them, so often when we are talking with type 2 diabetes and from my perspective it seems a lot of it is about lifestyle modification.” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) “Some people have discussed with me a wish that there were more social groups to talk with other people with diabetes and share their experiences and feel a bit more normal in their experiences with diabetes (…) Other community groups who might – it's a potential place for support to help people emotionally and peer support to make those changes or work through the frustrations of doing those things initially to look after themselves” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) |

| Quotes pertaining to physical and social environment (COM‐B header Opportunity) (cont.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main Themes | PWD Quotes | HCPs Quotes |

| Holistic approach |

“There was an article on picking GPs and dieticians who supported a holistic way of looking at you with your diabetes, that you do not focus on weight anymore, weight is just a side issue. The main thing is the wellness aspect, you want to feel good” (aged 60, 30 years since diagnosis) “Whether with the newly diagnosed, other services can kick in like, ‘Do you need to talk to somebody about how you are coping with this diagnosis with diabetes?’ Rather than, ‘you have got diabetes, give you a bit of script, off you go, we'll have a HbA1c in three months’. Maybe have access to easy recipes. Give the whole lot over to make that diagnosis a lot easier” (aged 60, 20 years since diagnosis) “Because that's what I found, being a diabetic and going to my GP, she just gives me this tablet and that's it” (aged 64, 13 years since diagnosis) “They should have had a more holistic approach to your care at that time” (aged 60, 20 years since diagnosis) |

“We've got practice systems and employees, etcetera, databases and recall, but once the patient attends then, to listen and understand, I mean that's – living with diabetes is more than just numbers and glucose, it's about understanding how people live and how they apply all their knowledge of their diabetes to their own life and how sometimes it's difficult (…) We're trying to work out where are the patients in the time course of their illness, that is newly diagnosed, have they got complications, etcetera, where are they in their living space, in their psychology, their understanding of diabetes, and then trying to construct a plan, but using practice stuff” (primary HCP, 26 years' experience) “Education that there is something you can do if you make some lifestyle modifications, if you might be engaged in weight loss strategies, if you manage – stress and high sugars is very correlated to look after your mental health, look after stress levels, all those lifestyles and really support them in that” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) |

| More personalisation |

“Obviously there's a lot of people out there, but it wasn't as personalised. Everyone's diabetes is different, and it's very painful or not painful, but just a hard thing to deal, with each case being different, my dad has got diabetes, and he's completely different to me” (aged 34, 15 years since diagnosis) “So different foods do different things to different people. And what people have got to remember and that is everyone from people like myself, right through to doctors that people are not always what is in the book. So, they cannot put everyone, ‘You're a diabetic. This is what you have got to do.’ It's not. Because it does not work for everyone” (aged 61, 19 years since diagnosis) “Exercise physiologists I find have helped me more so than the physios etcetera. You know, that can be helpful, so acknowledge the things that you can do, particularly when you have got joint limitations like I have.” (aged 70, 21 years since diagnosis) |

“They're the ones that – it's about them, so you just – you need to be saying, ‘Well, what do you feel you need to help you get to your goal?’ Because you have to have goals. You have to have outcomes.” (primary HCP, 6 years' experience) “One of the things I noticed over at the hospital, was that, for the first ten minutes or so, they spoke only about what's been going on in your life. Tell us about cricket, you have been playing cricket, how's that going. Often, I'll know people from the last visit or the visit before, and how's it going, I know you were looking at changing your job, did you end up doing it?” (specialist HCP, 19 years' experience) “Having a medication regime that worked for the patient as well as giving them reasonable control of what works for them, I think, is something needs to be considered a little bit more ‘these are your options. You can either have this, this or this. These are the outcomes for all of these, which way would you like to go?’” (specialist HCP, 11 years' experience) |

| Quotes pertaining to physical and social environment (COM‐B header Opportunity) (cont.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main Themes | PWD Quotes | HCPs Quotes |

| Support and encouragement from HCPs |

“When they bring the next patient in, and they'll be like, ‘I forgot what [name deleted]’s problems were’. It's like you are in a deli with a ticket, it's like, ‘now serving number 15″ (aged 47, 20 years since diagnosis) “If we have got a good relationship that means there's good communications; they are keeping an eye on what's happening and they are showing an interest (…) To treat you as a partner, because it's a shared thing. They've got knowledge that you want, and you have got experience that only you can give them to let them know how to treat your individual case” (aged 61, 19 years since diagnosis) “For instance, I saw him this week, and he actually said, ‘You do eat well, it's partially your problems with movement.’ I guess he actually takes some of the guilt (…) We need the people who sort of say, ‘Well yeah, okay. You're doing well. But make sure you stay there.’” (aged 70, 21 years since diagnosis) |

“It's also promoting honesty, making sure they feel honest and comfortable to really tell you what's going on. Because, we are not going to judge, we just want to be able to help them (…) It's not just a quick review of their BGLs, it's reinforcement, they are doing really well. Or, if they say they have lost weight, there's again, that motivational, ‘Keep going, that's fantastic’” (specialist HCP, 6 years' experience) “I'm doing a mini assessment on every single person who comes to clinic and then addressing needs as they arise and so I do get to know the patients a lot better. Then that rapport develops a lot easier, because they do see me at every single clinic, not just if there's a problem” (primary HCP, 5 years' experience) “Also encouraging the patient when positive changes are taken on board or actions, so always encouraging, it's very important to use appropriate language, and engagement” (primary HCP, 26 years' experience) |

| More coordination |

“What would be really good is if we could get the different doctors to talk to each other. I've got a cardiologist, respiratory specialist, gastroenterology, orthopaedics, neurology. I've got so many and none of them speak to the other and consequently you get frustrated.” (aged 64, 8 years since diagnosis) “There's not one person that you go to for all of your diabetes assistance. You go to the GP to be prescribed a medication but your care plan, all your bits and pieces, are handled by the surgery nurse. There just does not seem to be any continuity. I think things are lost in translation. (…) To me, it's not logical” (aged 56, 5 years since diagnosis) “The technology can come into this too, because they do not necessarily have to all get together in one room. So, the fact that your health record is now going up on to the computer for all public hospitals to be able to see, is a really big step in the right direction” (aged 64, 8 years since diagnosis) “They say it's a lifestyle disease, and I hate the way you have to go to a chronic diseases unit with your diabetes. It sort of needs to be away from the hospital I reckon to have all this stuff with all the allied health professionals. I can just see it being more casual, and not a medical approach. A wellness centre.” (aged 60, 30 years since diagnosis) |

“From a patient point of view, once they are first of all told that they have got diabetes it's very disjointed” (specialist HCP, 6 years' experience) “Of course there is communication issues. If your letter comes after two or three months, that's a communication issue, cause we do not know what the medications are” (primary HCP, 14 years' experience) “If it was well advertised and GPs knew that they could call and not have to wait for someone to get back to them, actually get an answer on the spot. So, if they had someone to call while the patient was with them to say, ‘I've got this patient. What do you think I should do?’ It would be quite useful” (specialist HCP, 12 years' experience) “That true case management I believe is the absolute success of this model of care, because they know that there's someone there and that person will go back to them the next date they are here or they'll deal with their issue on the spot if they can” (primary HCP, 5 years' experience) “We have obviously the same nurse every time. They see the same two GPs that do the diabetes clinic and they seem the same endocrinologist every time. So, I like our model from that perspective because they always see that” (primary HCP, 5 years' experience) |

| Quotes pertaining to physical and social environment (COM‐B header Opportunity) (cont.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main Themes | PWD Quotes | HCPs Quotes |

| Proactive assistance |

“If you say, ‘Well, I think I'm edging the wrong way’, it needs to be addressed then, not later on when you are in trouble, and not when your eyes are gone, do you know what I mean? I mean, I'm listening to what she was saying, and she needs prompt eye care, regular eye care, because she's in trouble on her eyes, and she needs it” (aged 70, 21 years since diagnosis) “Simply be in a better position to contact the specialist and ask the question instead of the patient waiting six or nine months, that would be one good thing” (aged 61, 19 years since diagnosis) “The GP needs to be able to say something like, ‘This person needs to be seen fairly promptly, because she's in trouble’” (aged 70, 21 years since diagnosis) “I need that accountability as well. I think I find it more comfortable and satisfying that I know someone is there and if something suddenly happens then I'm able to get to help immediately (…) I think that's what people would get out of a technology‐based thing, is the comfort of knowing that if something goes wrong someone is there to pick up on it and so consequently, they would get help sooner” (aged 64, 8 years since diagnosis) |

“But we do know that we need to get in early, in the early stages where you can reverse thing. We need to be able to focus on that” (specialist HCP, 19 years' experience) “Where probably at that early point when they are being started on oral medication that changing things like diet and exercise could actually make a bigger difference” (specialist HCP, 12 years' experience) “I could just check it at any time. That technology absolutely makes – and that's the centre obviously, if people own the Accu‐Chek guide, you can go in and they have linked it to their App. You can see their blood sugars whenever you want to look at them and can offer feedback whenever it's needed and people like that” (primary HCP, 5 years' experience) “We try to support the patient as best we can too, because diabetes management likes a bit of regularity and review and try to make sure people do not accidentally fall through the cracks” (primary HCP, 26 years' experience) “I'll give you a face‐to‐face Skype call, we'll have a quick chat ‘cause you still do need the face to face even with the technology because then you are still getting that personal care. No‐one wants to be just a number, so they still want a little bit of face to face but not necessarily having to come in every week” (specialist HCP, 11 years’ experience) |

| Quotes pertaining to emotions, evaluation and plans (COM‐B header Motivation) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main Themes | PWD Quotes | HCPs Quotes |

| Emotions and burden of living with diabetes |

“Because sometimes it felt like you hit a wall. I've got diabetes. I'm terrified (…) It still gets a little bit confusing. The whole diabetes is frightening to start with and then some of the terminology, the way some health professionals talk, it adds to the whole fear of it” (aged 46, 6 years since diagnosis) “Hated in the beginning, pricking the fingers upwards of four times a day. I hate that with an absolute passion” (aged 47, 20 years since diagnosis) “I thought it is frustrating because you are being given this tag, ‘You're a diabetic’. He [husband with diabetes] was made to feel that he was a bad person because he allowed it to happen” (aged 64, 13 years since diagnosis) “’Have you looked at my file?’ Like, I was 153 [kilos] two years ago, so I've lost like 30‐odd kilos, and the first thing they say is, ‘You're obese.’ ‘Yeah. Thanks for that. (…) There's an assumption. There's no discussion about have you lost weight, or what is your diet, nothing. They just assume straight away” (aged 47, 5 years since diagnosis) |

“The ones I meet are the ones who are struggling with accepting they have a new diagnosis, trying to make changes to very long‐standing habits and behaviours” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) “Diabetes distress is something that I see a lot of, the burden and stress and the diabetes type 1 and type 2 is well known to be correlated with depression and anxiety. (…) What's associated with diabetes distress is also the social impacts, the stigmas, the constant reminders that you have a disease” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) “Language is very important or dismissive language, saying, ‘you are fat’, or, ‘you are obese and you need to lose weight’, so shaming the patient or confronting the patient negatively I do not think is a healthy option” (primary HCP, 26 years' experience) “Tt's also promoting honesty, making sure they feel honest and comfortable to really tell you what's going on. Because, we are not going to judge, we just want to be able to help them.” (specialist HCP, 6 years' experience) |

| Beliefs and motivation to manage diabetes |

“Didn't really believe it but then I had some really bad problems in 2007, 2008 and I was actually put in the care of a specialist endocrine doctor, who woke me up to how serious diabetes can be and then I lost a few toes and that really put me back on the straight and narrow” (aged 74, 45 years since diagnosis) “With the whole not understanding the food values and what not and you think you are doing the right thing and my sugars are actually going up, not going down. It comes back to that whole, why bother if it's not working?” (aged 46, 6 years since diagnosis) “I'm one of those people who struggles with discipline and motivation sometimes” (aged 52, 13 years since diagnosis) “I think too motivation – it has not worked with me really, motivation to keep on track” (aged 60, 20 years since diagnosis) |

“They do not believe they can succeed. So, they do not believe there is a path that they can take that is going to do it” (primary HCP, 25 years' experience) “One aspect is giving them hope and opportunity and education early on and it's not death sentences. It's not like a blame situation, but it's treating them with compassion, but giving them hope that there are things they can do and also having the support and the self‐efficacy, that believe that they could do something and actually get a result and make a difference to their diabetes” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) “I think the missed part of that is still engaging patients. And encouraging them to change lifestyles. And I think involving them in their care” (primary HCP, 14 years' experience) “Maybe often trying to find a source of motivation. So, if people have children that they want to grow old for and want to be healthy and be able to do stuff with, a lot of the time that seems to be motivating for patients” (specialist HCP, 12 years' experience) |

| Quotes pertaining to emotions, evaluations and plans (COM‐B header Motivation) (cont.) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main Themes | PWD Quotes | HCPs Quotes |

| Plans and goals |

“What I have trouble with now, because I used to take the insulin before I went to bed because it was ideal. Now I take it with dinner, I keep forgetting it, so I'm used to putting it beside where I have my dinner, so I put it there, so I remember. I forget” (aged 72, 30 years since diagnosis) “I always took my blood sugars each morning and I quite often took my blood pressure as well. Do everything. I've just added in to it, it's the pulse oximeter. But it just means I do the whole lot. Stand on the scales. Have a shower. Come in, get dressed. Take my insulin. Go out, do the other measurements. Take my pills and then go with the day from there. So, it's just part of my normal routine” (aged 64, 8 years since diagnosis) “I'm just looking forward to getting rid of this ulcer so I can actually do something. I used to get up at four o'clock each morning and walk for a couple of kilometres just around my local neighbourhood and I used to really enjoy that” (aged 74, 45 years since diagnosis) “Just quality of life improvements, ease of life, I guess you could say, to make things easier for us. As I said, I started off initially injecting four times a day, I'm now down to two times a day. That's great. If I can get it to once a day, sign me up, I would love that. Just stuff that you are not constantly having to worry, and that you can just be normal” (aged 47, 20 years since diagnosis) |

“Understanding your patients, how they live, talking to them about it, but also then also working with them about setting healthy goals, but that work for them, but some of the goals for patients might include more than just glucose, like weight management, psychological support, it might mean they might need education, and so it's about trying to get inside the patient's realm of living and understanding what is their needs now and in the future, both near and long‐term” (primary HCP, 26 years' experience) “You'd hope so because people know what their plan is and they know what their goals are, and if you have got family onboard, they are hopefully going to be more supportive” (specialist HCP, 8 years' experience) “If we could connect patients with technology that kept them aware of the goals and where they are in relationship to those goals” (primary HCP, 26 years' experience) “Motivational interviewing, you can write the smart goals, you can try and get them to make their own – obviously, it's their goals, they need to reflect and make their own journey, but it is hard” (specialist HCP, 6 years' experience) “As you said, there's no holidays. You have to be caring for yourself and monitoring and injecting if you have to take insulin” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) |

| Quotes pertaining to HCPs’ own burden and needs | |

|---|---|

| Main Themes | HCPs Quotes |

| HCPs' challenging work |

“With some people it's very frustrating, they are trying and trying and trying, but they are not actually getting their sugars and they are not getting the control that they should be getting. So, a lot of that then is expectations and compassion and all that” (specialist HCP, 10 years' experience) “But we just do not seem to get the time to do it because we are too busy – we do not have the resources to be giving those basics when we are not there (…) We're relying on the GPs to provide the information and time constraints are such that they cannot do it. We do not see them. We will not see a new type 2 ‘cause our time constraints on an inpatient basis is there's just too many patients to see. So, they are not getting the education from us. We're saying ‘go to your GP’. GP cannot do it.” (specialist HCP, 11 years’ experience) “But then, the doctor is worried about being audited, and making sure that everything is being done correctly, otherwise Medicare will come in and say, ‘You've got to pay us back’. So, there's also that fear as well, I think, that you have done the plan properly” (primary HCP, 6 years' experience) “Even though we have tried to keep well‐educated, there's just a plethora of new treatment options and changes in the guidelines such that trying to keep up to date, for some patients, someone with diabetes particularly, is quite difficult. And changes in when do you use GLP‐1 versus insulin and what's the dose, what are the names of the agents, all these things. Because there's so many other diseases GPs manage” (primary HCP, 26 years' experience) “Particularly given GPs have to look after every other medical problem as well. The ones that do not have a special interest in diabetes aren't going to have read 130 pages on a diabetes management, I would not think” (specialist HCP, 12 years' experience) “Whereas in some areas I worked at, everyone is overweight, so I tell them, ‘You are overweight’. But, they say, ‘Everyone is like that, so that's normal’. It's a bit difficult” (primary HCP, 10 years' experience) |

Vasconcelos Silva C, Bird D, Clemensen J, et al.. A qualitative analysis of the needs and wishes of people with type 2 diabetes and healthcare professionals for optimal diabetes care. Diabet Med. 2022;39:e14886. doi: 10.1111/dme.14886

REFERENCES

- 1. Fatehi F, Menon A, Bird D. Diabetes care in the digital era: a synoptic overview. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(7):38. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1013-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Captieux M, Pearce G, Parke HL, et al. Supported self‐management for people with type 2 diabetes: a meta‐review of quantitative systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2018;8(12):e024262. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clemensen J, Rothmann MJ, Smith AC, Caffery LJ, Danbjorg DB. Participatory design methods in telemedicine research. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(9):780‐785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schimmer R, Orre C, Oberg U, Danielsson K, Hornsten A. Digital person‐centered self‐management support for people with type 2 diabetes: qualitative study exploring design challenges. JMIR Diabetes. 2019;4(3):e10702. doi: 10.2196/10702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . Integrated care models: an overview. 2016. Internet. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/322475/Integrated‐care‐models‐overview.pdf

- 6. Consumers Health Forum of Australia, RACGP, Menzies Centre for Health Policy, The George Institute . Patient‐centred healthcare homes in Australia: towards successful implementation. 2016. Internet. https://chf.org.au/sites/default/files/patient‐centred‐healthcare‐homes‐in‐australia‐towards‐successful‐implementation.pdf

- 7. Russell AW, Donald M, Borg SJ, et al. Clinical outcomes of an integrated primary‐secondary model of care for individuals with complex type 2 diabetes: a non‐inferiority randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2019;62(1):41‐52. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4740-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. American Diabetes Association . Position statement: strategies for improving care. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl. 1):S6‐S12. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maneze D, Dennis S, Chen HY, et al. Multidisciplinary care: experience of patients with complex needs. Aust J Prim Health. 2014;20(1):20‐26. doi: 10.1071/PY12072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Calder R, Dunkin R, Rochford C, Nichols T. Australian health services: too complex to navigate. A review of the national reviews of Australia's health service arrangements. Australian Health Policy Collaboration, Policy Issues Paper No. 1. 2019. Internet. AHPC. https://apo.org.au/node/223011

- 11. Sainsbury E, Shi Y, Flack J, Colagiuri S. Burden of diabetes in Australia: it's time for more action. 2018. Internet. The University of Sydney. https://www.sydney.edu.au/content/dam/corporate/documents/faculty‐of‐medicine‐and‐health/research/centres‐institutes‐groups/burden‐of‐diabetes‐its‐time‐for‐more‐action‐report.pdf

- 12. Jain SR, Sui Y, Ng CH, Chen ZX, Goh LH, Shorey S. Patients' and healthcare professionals' perspectives towards technology‐assisted diabetes self‐management education. A qualitative systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ravn Jakobsen P, Hermann AP, Sondergaard J, Wiil UK, Clemensen J. Development of an mHealth application for women newly diagnosed with osteoporosis without preceding fractures: a participatory design approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):330. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15020330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O'Toole ML, Shetty G, Anwuri VV, Glasgow RE. Ecological approaches to self‐management: the case of diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1523‐1535. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Catapan S, Nair U, Gray L, et al. Same goals, different challenges: a systematic review of perspectives of people with diabetes and healthcare professionals on type 2 diabetes care. Diabet Med. 2021;38(9):e14625. doi: 10.1111/dme.14625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753‐1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‐101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic analysis. In: Liamputtong P, ed. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer Singapore; 2019:843‐860. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jensen CM, Santy‐Tomlinson J, Overgaard S, et al. Empowerment of whom? The gap between what the system provides and patient needs in hip fracture management: a healthcare professionals' lifeworld perspective. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2020;38:100778. doi: 10.1016/j.ijotn.2020.100778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ravn Jakobsen P, Hermann AP, Soendergaard J, Kock Wiil U, Myhre Jensen C, Clemensen J. The gap between women's needs when diagnosed with asymptomatic osteoporosis and what is provided by the healthcare system: a qualitative study. Chronic Illn. 2021;17(1):3‐16. doi: 10.1177/1742395318815958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shaw J, Tanamas S. Diabetes: the silent pandemic and its impact on Australia. 2012. Internet. Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute. https://static.diabetesaustralia.com.au/s/fileassets/diabetes‐australia/e7282521‐472b‐4313‐b18e‐be84c3d5d907.pdf

- 24. Litterbach E, Holmes‐Truscott E, Pouwer F, Speight J, Hendrieckx C. I wish my health professionals understood that it's not just all about your HbA1c !'. Qualitative responses from the second diabetes MILES – Australia (MILES‐2) study. Diabet Med. 2020;37(6):971‐981. doi: 10.1111/dme.14199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vuohijoki A, Mikkola I, Jokelainen J, et al. Implementation of a personalized care plan for patients with type 2 diabetes is associated with improvements in clinical outcomes: an observational real‐world study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:1‐7. doi: 10.1177/2150132720921700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dickinson JK, Guzman SJ, Maryniuk MD, et al. The use of language in diabetes care and education. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(12):1790‐1799. doi: 10.2337/dci17-0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jensen CM, Overgaard S, Wiil UK, Smith AC, Clemensen J. Bridging the gap: a user‐driven study on new ways to support self‐care and empowerment for patients with hip fracture. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:1‐13. doi: 10.1177/2050312118799121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dixon BE, Embi PJ, Haggstrom DA. Information technologies that facilitate care coordination: provider and patient perspectives. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8(3):522‐525. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brandt CJ, Clemensen J, Nielsen JB, Sondergaard J. Drivers for successful long‐term lifestyle change, the role of e‐health: a qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e017466. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bu D, Pan E, Walker J, et al. Benefits of information technology‐enabled diabetes management. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1137‐1142. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]