Abstract

Older people living in squalor present healthcare providers with a set of complex issues because squalor occurs alongside a variety of medical and psychiatric conditions, and older people living in squalor frequently decline intervention. To synthesise empirical evidence on squalor to inform ethical decision‐making in the management of squalor using the bioethical framework of principlism. A systematic literature search was conducted using Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL databases for empirical research on squalor in older people. Given the limited evidence base to date, an interpretive approach to synthesis was used. Sixty‐seven articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in the review. Our synthesis of the research evidence indicates that: (i) older people living in squalor have a high prevalence of frontal executive dysfunction, medical comorbidities and premature deaths; (ii) interventions are complex and require interagency involvement, with further evaluations needed to determine the effectiveness and potential harm of interventions; and (iii) older people living in squalor utilise more medical and social resources, and may negatively impact others around them. These results suggest that autonomous decision‐making capacity should be determined rather than assumed. The harm associated with squalid living for the older person, and for others around them, means a non‐interventional approach is likely to contravene the principles of non‐maleficence, beneficence and justice. Adequate assessment of decision‐making capacity is of particular importance. To be ethical, any intervention undertaken must balance benefits, harms, resource utilisation and impact on others.

Keywords: squalor, hoarding, self‐neglect, Diogenes syndrome, principlism, ethics

Introduction

Squalor is defined as a living environment that is so cluttered and unhygienic that people of similar culture and background would consider extensive cleaning to be essential. 1 Past research has described squalor as a senile breakdown in standards of personal and environmental cleanliness. 2 Relatedly, Diogenes syndrome 3 defines a condition whereby older people exhibit symptoms of extreme self‐neglect, domestic squalor, hoarding, social isolation and indifference to their situation. 4 While squalor is not regarded as a distinct disorder in current classification systems, it occurs as an epiphenomenon alongside other medical and psychiatric conditions, 5 and overlaps with self‐neglect and hoarding. 6

Squalor does not occur exclusively in older people, 7 , 8 , 9 but squalor among older people is of particular importance because they have more complex care requirements and intrinsic vulnerabilities. 10 It is estimated that 1 in 700 community‐dwelling older people live in squalor. 1 The absolute numbers may rise as older Australians opt to age‐in‐place in their own homes, 11 and long‐term care policies increasingly emphasise ageing‐in‐place at home. 12

Service providers are frequently faced with complex ethical dilemmas when responding to squalor among older adults, who often lack insight and refuse interventions. 5 , 6 , 13 , 14 Some clinicians feel obliged to intervene, 15 , 16 while others are reluctant to act against a patient's wishes, or may argue that squalor is an issue of people's living environment and not their health. 17 In addition, there is uncertainty around the effectiveness of healthcare interventions, as prognosis can be poor for those who are hospitalised 3 and precipitous clean‐ups can be traumatising. 18 A lack of ethical and evidence‐based guidance on the management of squalor can lead to inconsistent management practices and preclude older adults living in squalor from receiving supportive and appropriate interventions that would optimise their health outcomes.

Methods

This review sought to answer the following question: How can research evidence guide ethical health management of older people living in squalor?

In seeking to answer this question, we used the framework of principlism developed by Beauchamp and Childress 19 to explore whether interventional or non‐interventional approaches respect or violate the guiding principles of autonomy, non‐maleficence, beneficence and justice. The moral principle of autonomy is the obligation to respect the decision‐making capacity of autonomous agents. 19 Non‐maleficence and beneficence are closely linked yet distinct, as non‐maleficence is a negative principle that requires one to refrain from causing harm while beneficence is an active principle that requires action to promote good, remove harm or prevent harm. 19 Justice is the obligation to ensure fairness in the distribution of benefits and risks. 19

Given the limited research on ethics in the field of squalor management, a narrative review was used to interconnect and combine concepts from methodologically and ontologically diverse research with ethical reflections.

Literature search and selection

A systematic search of the literature was performed using Medline, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL databases. The search terms used were squalor, hoarding and Diogenes syndrome, and keywords that relate to management and intervention (Table 1). The electronic search was performed in September 2021, limited to humans, the English language, title and abstract. Citation searching was performed to identify additional reports.

Table 1.

Electronic search strategy

| Search terms | Medline (Ovid) | EMBASE (Ovid) | PsycINFO (Ovid) | CINAHL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Map term to subject heading | Hoarding Disorder, Hoarding | exp hoarding disorder, hoarding, obsessive hoarding, Diogenes syndrome | exp Hoarding Behaviour, Animal Hoarding Behaviour, exp. Hoarding Disorder | exp ‘Obsessive Hoarding’, ‘Diogenes Syndrome’ |

| exp Therapeutics Case Management, exp Patient Care Management | exp therapy, case management, exp patient care, intervention study | exp Treatment, exp Case Management | ‘Behaviour Therapy+’, ‘Case Management’ | |

| Keyword search in abstract and title | hoard*, ‘Diogenes Syndrome*’, squalor*, clutter*, elder*, senile*, old*, ‘older people’, ‘older adult*’, ‘older person*’, self‐neglect*, ‘self‐neglect’ | hoard*, ‘Diogenes Syndrome*’, squalor*, clutter*, elder*, senile*, old*, ‘older people’, ‘older adult*’, ‘older person*’, self‐neglect*, ‘self‐neglect’ | hoard*, ‘Diogenes Syndrome*’, squalor*, clutter*, elder*, senile*, old*, ‘older people’, ‘older adult*’, ‘older person*’, self‐neglect*, ‘self‐neglect’ | hoard*, ‘Diogenes Syndrome*’, squalor*, clutter*, elder*, senile*, old*, ‘older people’, ‘older adult*’, ‘older person*’, self‐neglect*, ‘self‐neglect’ |

| therap*, manag*, interven*, declutter*, de‐clutter* | therap*, manag*, interven*, declutter*, de‐clutter* | therap*, manag*, interven*, declutter*, de‐clutter* | therap*, manag*, interven*, declutter*, de‐clutter* |

Key search terms were mapped to subject headings in each database and searched as a keyword in Medline (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), psycINFO (Ovid) and CINAHL. The term ‘exp’ (Medline, EMBASE and PsycINFO) and the sign ‘+’ (CINAHL) indicate that the term was exploded in the MeSH (Medical subject heading) vocabulary to capture narrower terms associated with the broader concept. The asterisk * is a wildcard symbol used to broaden the search by finding words that start with the same letters. Quotation marks indicates phrase searching where words must appear as an exact phrase. All searches were limited to English language, humans and abstract.

The inclusion criteria were intentionally broad to capture diverse research across many disciplines. Reports were included if the mean age of adults living in squalor in the studies was ≥60 years. Conference abstracts, case reports with three or less participants, expert opinions and review articles were excluded. The process of selection was performed by a single author (SML).

Analysis framework and synthesis

The literature was coded inductively to map domain‐specific themes, with codes subsequently grouped based on the principlism framework. Such a coding approach allowed for a context‐specific assessment of the research evidence in relation to each of the four ethical principles.

As such, the analysis and synthesis focussed on four areas:

Cognitive profile of older people living in squalor, and the implications for their ability to make decisions with autonomy.

The natural trajectory of squalid living, and the implications for non‐interventional approaches respecting or violating the principle of non‐maleficence.

The positive and negative outcomes of interventions, and the implications for interventional approaches respecting or violating the principle of beneficence.

The utilisation of resources by older people living in squalor and their impact on others, and the implications for the principle of justice.

Results

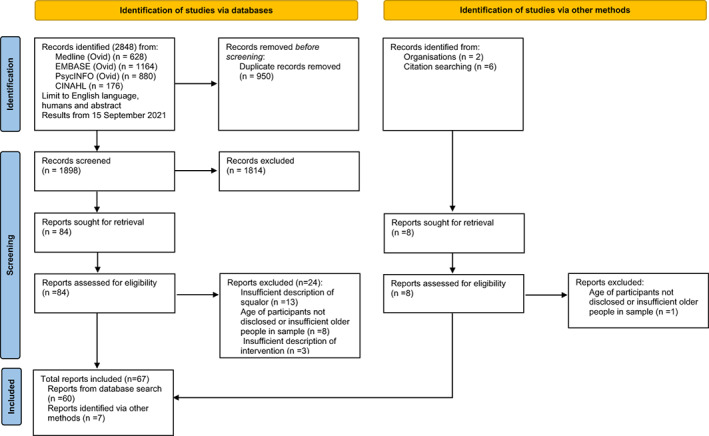

The systematic search generated 2848 records (Fig. 1). Following the removal of duplicates and screening, 67 reports published between 1966 and 2021 that met the review criteria were included in the review. Reports were excluded if they did not describe the living environment aligning with squalor, did not disclose the age of participants, if there were insufficient older people in the sample or they did not contain descriptions of the interventions employed.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy and identification of articles included in the review.

Cognition

Research identified a high prevalence of frontal executive dysfunction in older people living in squalor regardless of whether the pathway to squalor is one of neglect or hoarding. Studies of older adults with hoarding disorder found that most had executive dysfunction even if they did not meet the criteria for dementia, 20 , 21 and many had poor insight and delusional thinking. 22 In a case–control study of psychiatric outpatients, the presence of frontal executive dysfunction was significantly higher in the group in which self‐neglect and squalor were reported. 23 Moreover, older people living in squalor without hoarding were found to be more cognitively impaired and more likely to have a history of alcohol use compared with controls. 24

Another finding was that the widely used screening cognitive test, the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) may lack the sensitivity to detect frontal executive dysfunction. For example, clinical samples of older people living in squalor and self‐neglect associated with squalor recorded mean MMSE scores that fell within the normal range, despite the presence of frontal executive dysfunction detected on neuropsychological tests. 6 , 13 , 25

The natural trajectory of squalor

Health prognosis without intervention is poor. Symptoms of hoarding can begin early in childhood or adolescence, or as a reaction to stress in later life. 26 Research suggests that older people may hoard to allay anxiety and fear, and to provide a sense of control. 27 For some, a squalid lifestyle may reflect an active rejection of societal standards, 2 and hence constitute a form of self‐expression. 27 , 28

Several studies reported negative functional and health outcomes associated with squalor in older people. Excessive clutter can impede movement around the house, food preparation and ability to attend to one's hygiene. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 In addition, individuals have a higher risk of falls, 33 elder abuse 34 and institutionalisation. 3 , 35 Older people living in squalor frequently have medical comorbidities that require medical attention such as mental health conditions, 9 , 36 chronic pain, 37 , 38 alcoholism, 6 , 9 diabetes and sleep apnoea. 39

Critically, studies on the association between hoarding and mortality found a higher likelihood of premature death, 3 , 35 , 40 estimated to represent 16.1 years of potential life lost. 40 Similarly, a Melbourne study of fire fatalities found an overrepresentation of older people in hoarded households, whose safe evacuation was likely prevented by poor decision‐making, falls, cluttered egresses and difficulties containing fires due to high fuel loads. 41

Interventions

Intervention options for squalor include case‐management, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), compassion focused therapy, cognitive remediation and public sector responses. Case management can be helpful in facilitating access to medical care and social support, 42 but can be insufficient as a sole intervention in eliminating the risk of eviction for older individuals with hoarding. 43 Currently, case management is the main intervention for older people whose squalid living conditions that have arisen from passive neglect.

Psychological treatments aimed at changing behaviour have only been trialled in people who live in squalor that have resulted from hoarding. CBT on its own produces minimal improvement in older people, 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 but CBT with practical in‐home support can reduce depression and hoarding severity. 49 A more effective intervention is Cognitive Rehabilitation and Exposure/Sorting Therapy (CREST), which is a manualised treatment protocol that targets memory, executive functioning, exposure challenge and relapse prevention strategies. 42 , 50 , 51 , 52 CREST is more effective in reducing hoarding severity compared with case management immediately post‐intervention (78% vs 28% responder rate respectively), 50 yet showed little difference after 12 months. 42

Alternatively, compassion‐focussed therapy (CFT), which emphasises emotion regulation through mindfulness and compassion imagery, treats individuals by physiologically activating the parasympathetic nervous system to achieve settling and soothing states during de‐cluttering efforts. 53 In a small CFT study (N = 18) without a control group, 62% of older hoarders achieved a clinically significant reduction in hoarding severity. 53 Other interventions such as cognitive remediation which use computerised programmes to target cognitive function can improve attention; however, it does not reduce hoarding severity or improve executive function. 54 Interventions that require further evaluation include the use of occupational therapists for training in planning and organisational skills, 55 and the use of volunteers, who compared with clinicians, can be less resource intensive, more flexible and able to promote relationships that lead to improvements in other aspects of life. 56

Public sector responses to hoarding have primarily focussed on reducing the risk of harm to the individual, and mitigating the impact on others through environmental interventions. Clean‐ups can be effective in reducing clutter and preserving tenancy, 57 and are more tolerable if the older adult is engaged in the process. 58 Fire authorities have shown success in raising awareness of fire risks of hoarding households through education campaigns along with the free installation of smoke alarms, leading to higher success in containing fires to the room of origin and less property damage. 59 A novel programme offering neutering of female cats in animal hoarding households showed a 40% reduction in cat numbers at 12 months. 60

Several barriers to successful interventions were identified. Multidisciplinary teams have highlighted the lack of standardised responses, and inadequate funding and in‐home mental health services as significant barriers to achieving positive outcomes. 61 In addition, public sector providers who conduct expensive cleans identified the need for more training and improvement in multi‐agency service coordination. 57 , 58

Resource allocation and impact on others

Older adults living in squalor can impose a burden on health system resources, and those around them. Findings in a case–control study indicated that compared with other psychiatric inpatients, older patients with squalor utilised more social services, stayed longer in hospital and were more likely to be discharged to dependent accommodations. 62 Moreover, code enforcement and social services report that clean‐ups are expensive and usually involve multiple agencies. 63 In contrast, a case–control study into the healthcare costs by older people found that those with self‐neglect incurred lower costs in the preceding year before coming to the attention of adult protective services, and subsequently incurred similar costs thereafter. 64

Family and caregivers experience negative environmental impacts, family dysfunction and marginalisation, and require support and coping strategies for themselves. 65 , 66 Families often need psychoeducational support to assist in understanding hoarding, 65 , 67 and to be motivators for change. 68 Qualitative studies involving case workers revealed that they were frequently ethically conflicted when trying to initiate change, 69 , 70 and experienced greater rejection and poorer alliances when working with their clients. 71 Volunteers also require additional support as clients can be paranoid and demanding. 56 In a survey of psychiatrists who treated older adults with self‐neglect in Ireland, 93% of them reported that their patients had unsatisfactory outcomes and 72% reported unsatisfactory outcomes for themselves. 72 In addition, all respondents in this study felt their role should be limited to the management of psychiatric issues and 82% felt that social services should provide the care required.

Squalor in older people can be related to hoarding animals, which can be as numerous as 40–50 animals per owner. These animals are usually in poor health, and live in unsanitary and inhumane conditions. 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 Researchers in veterinary medicine who have reported on the negative impacts of animal hoarding on the animals, advocate for greater involvement from mental health services 75 , 76 with at least 30% of animal hoarders known to mental health services reported in one Australian study. 77

Discussion

This review is the first to have scoped empirical research on squalor in older people and appropriate interventions, and synthesise these findings into the principlism framework to support decision‐making by healthcare providers. In doing so, this review found that older people living in squalor have a higher prevalence of frontal executive dysfunction, a higher risk of morbidity and mortality, used more medical and social resources, and negatively impact others around them. More critically, this review highlighted insufficient research on the effectiveness of interventions, recidivism rates and harm caused by intervention in the management of squalor in older people.

A crucial implication for clinical practice is, in seeking to support the principle of autonomy, the cognitive capacity of older people living in severe domestic squalor who have frontal executive dysfunction needs to be carefully considered. This understanding is critical given that those who decline to cooperate with assessments may be even more impaired. 15 In addition, the presence of frontal executive dysfunction has implications for management. While frontal executive dysfunction presents in younger people, its severity increases with age 78 and may impede abstract cognitive strategies. 44 , 78 This may explain why CBT, which is the main treatment for younger people with hoarding disorder, is less effective in older people. 44 It is also likely the reason why older people living in squalor may require assistance to improve their living conditions as their cognitive deficits reduce their ability to formulate intentions, and to develop and execute plans. 79 , 80 , 81

The findings that squalor significantly increases the risk of morbidity and mortality suggests effective interventions may be beneficent, and a non‐interventional approach may violate the principle of beneficence. However, interventions that are likely to cause harm – such as disposing of possessions without supporting or including the older person through the process – may violate the principles of beneficence and non‐maleficence.

Last, the findings that older adults living in squalor can place a burden on families, carers, neighbours, animals and the wider health system have implications for the principle of justice. In circumstances where the burdens or the risks on others are significant, it may be ethically justifiable to intervene against the wishes of an older adult. Thus, it may be appropriate to override a particular principle if competing moral conditions exist; for example, autonomy can be restricted if an individual's choice has the potential to harm others, 19 , 82 particularly if these other individuals are vulnerable and lack autonomous decision‐making capacity themselves including children, dependent adults or animals. 83

These complexities can create challenges within organisations. Effective management can be expensive, time consuming and complicated, so agencies may try to offload their responsibilities. 84 Individual care workers facing this dilemma may either provide services above and beyond their employment descriptions, 10 , 19 , 85 or become detached due to the effects of organisational acculturation. 10 The ethical obligations of organisations that provide in‐home care services to older people would benefit from closer examination.

While this review provided some critical insights, it also revealed the limitations of the principlism approach. Clinicians working with an older person may not have the required information or competence to analyse and weigh competing ethical principles. In such situations, the ethics of care may offer a complementary ethical framework that could help to inform decision‐making. This approach emphasises the trustworthiness of the care provider and their willingness to act for the care recipient. 19 Several reports found that interventions for squalor produced better results when clients developed trust in those who were offering assistance. 10 , 28 , 31 , 56 , 61 , 71 , 86 Mcdermott proposed that the care of older people living in squalor may be best addressed using a pluralistic ethical approach. 10

Strengths

This review is the first to synthesise a systematic review of the literature with an ethical framework that includes overlapping conditions of squalor, specifically Diogenes syndrome, self‐neglect and hoarding. It provides practical and research‐informed insights for healthcare professionals to guide ethical decision‐making and exposes significant research gaps related to effective interventions, resource allocation and impact on others.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review. The review was restricted to the English language and included case reports with four or more cases. While case reports and case series are critiqued as lacking comparison groups, they are useful for seminal cases and rare conditions, 87 or where the level of engagement with research is low, such is the case for squalor. 88 , 89 As such, our use of case series allowed for data to be combined, enabling a more systematic and statistical analysis compared to case reports. 87

Most of the participants in empirical studies on squalor consisted of convenience samples of older people who have come to the attention of health or community services. While these findings have immediate relevance to professionals working in aged‐care services, they may not be applicable to older people who are at less advanced stages of squalor, or to younger people living in squalor who do not have age‐related vulnerabilities. Last, there is a notable scarcity of research that examines the perspectives of older people living in squalor, with the vast majority of the qualitative studies conducted on professionals, volunteers and family. Much more can be gained from further research to fully understand squalor, which is a condition that largely occurs behind closed doors.

Conclusion

Within society, people are usually accorded a large degree of autonomy as to how they maintain the interior of their home. The issue of squalor in older people challenges us to make difficult decisions about how and when it is appropriate to intervene against someone's wishes. A principlism approach, informed by current evidence, can support robust and nuanced discussions regarding the ethics of managing older adults living in squalor.

This review found that squalor in older people is not a benign condition, and has serious implications for the individual and those around them. Importantly, in the absence of highly effective treatments, any intervention undertaken must consider a complex matrix of benefits, harms, resource allocation and impact on others to achieve ethical and effective outcomes for older people living in squalor.

Further research is needed, including prospective studies into effective management of squalor among people of different ages, diagnoses, and stages of progression. Evidence‐based tools are needed to help quantify harm for the person living in squalor, risks to others, resource utilisation, and recidivism rates. In addition, a pluralistic approach that combines principlism and with other ethical framework such as care ethics, may help to deepen ethical discourse in this area.

Acknowledgements

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1. Snowdon J, Halliday G, Banerjee S. Severe Domestic Squalor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Macmillan D, Shaw P. Senile breakdown in standards of personal and environmental cleanliness. Br Med J 1966; 2: 1032–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark A, Mankikar G, Gray I. Diogenes syndrome: a clinical study of gross neglect in old age. Lancet 1975; 1: 366–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cybulska E, Rucinski J. Gross self‐neglect in old age. Br J Hosp Med 1986; 36: 21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Snowdon J, Shah A, Halliday G. Severe domestic squalor: a review. Int Psychogeriatr 2007; 19: 37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee SM, Lewis M, Leighton D, Harris B, Long B, Macfarlane S. Neuropsychological characteristics of people living in squalor. Int Psychogeriatrics 2014; 26: 837–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooney AC, Hamid W. Review: Diogenes syndrome. Age Ageing 1995; 24: 451–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drummond L, Turner J, Reid S. Diogenes’ syndrome – a load of old rubbish? Ir J Psychol Med 1997; 14: 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Halliday G, Banerjee S, Philpot M, MacDonald A. Community study of people who live in squalor. Lancet 2000; 355: 882–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mcdermott S. Self Neglect and Squalor Among Older People: The Ethics of Intervention. Sydney: University of New South Wales; 2007. Available from URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228750479_Self_neglect_and_squalor_among_older_people_the_ethics_of_intervention [Google Scholar]

- 11. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) . The desire to age in place among older Australians. AIHW Bulletin no. 114. Cat. no. AUS 169. Canberra: AIHW; 2013. Available from URL: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/69a6b0b9-6f86-411c-b15d-943144296250/15141.pdf.aspx?inline=true#:~:text=Many%20older%20Australians%20say%20that,or%20even%20moving%20at%20all.&text=The%20vast%20majority%20of%20older%20Australians%20own%20their%20home%20outright.

- 12. Pagone T, Briggs L. Royal commission into aged care quality and safety: final report – executive summary. Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety; 2021; 19: 61–175. Available from URL: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-03/final-report-executive-summary.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gregory C, Halliday G, Hodges J, Snowdon J. Living in squalor: neuropsychological function, emotional processing and squalor perception in patients found living in squalor. Int Psychogeriatrics 2011; 23: 724–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shah A. Senile squalor syndrome: what to expect and how to treat it. Geriatr Med 1990; 20: 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Snowdon J. Severe domestic squalor: time to sort out the mess. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014; 48: 682–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sutherland A, Macfarlane S. Domestic squalor: who should take responsibility? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014; 48: 690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mcdermott S. Ethical decision making in situations of self‐neglect and squalor among older people. Ethics Soc Welf 2011; 5: 52–71. [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Psychiatric Association . Obsessive‐compulsive and related disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 8th edn. New York: Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ayers C, Dozier M, Wetherell J, Twamley E, Schiehser D. Executive funcitoning in participants over age of 50 with hoarding disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 24: 342–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ayers C, Wetherell JL, Schiehser D, Almklov E, Golshan S, Saxena S. Executive functioning in older adults with hoarding disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 28: 1175–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tolin DF, Fitch KE, Frost RO, Steketee G. Family informants’ perceptions of insight in compulsive hoarding. Cognit Ther Res 2010; 34: 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schillerstrom JE, Salazar R, Regwan H, Bonugli RJ, Royall DR. Executive function in self‐neglecting adult protective services referrals compared with elder psychiatric outpatients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009; 17: 907–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gleason A, Lewis M, Lee SM, Macfarlane S. A preliminary investigation of domestic squalor in people with a history of alcohol misuse: neuropsychological profile and hoarding behavior – an opportunistic observational study. Int Psychogeriatrics 2015; 27: 1913–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naik AD, Pickens S, Burnett J, Lai JM, Dyer CB. Assessing capacity in the setting of self‐neglect: development of a novel screening tool for decision‐making capacity. J Elder Abus Negl 2006; 18: 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grisham J, Frost RO, Steketee G, Kim HJ, Hood S. Age of onset of compulsive hoarding. J Anxiety Disord 2006; 20: 675–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andersen E, Raffin‐Bouchal S, Marcy‐Edwards D. Reasons to accumulate excess: older adults who hoard possessions. Home Health Care Serv Q 2008; 27: 187–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roster CA. “Help, I have too much stuff!”: extreme possession attachment and professional organizers. J Consum Aff 2015; 49: 303–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ayers C, Ly P, Howard I, Mayes TL, Porter B, Iqbal Y. Hoarding severity predicts functional disability in late‐life hoarding disorder patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014; 29: 741–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ayers C, Schiehser D, Liu L, Wetherell J. Functional impairment in geriatric hoarding participants. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2012; 1: 263–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dong XQ. Elder self‐neglect in a community‐dwelling U.S. Chinese population: findings from the population study of Chinese Elderly in Chicago (PINE) study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62: 2391–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim HJ, Steketee G, Frost RO. Hoarding by elderly people. Heal Soc Work 2001; 26: 176–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arluke A, Patronek G, Lockwood R, Cardona A. Animal hoarding. In: Maher J, Pierpoint H and Beime P, eds The Palgrave International Handbook of Animal Abuse Studies. London, United Kingdom: Macmillan Publishers Ltd; 2017; 107–29. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bartley M, O'Neill D, Knight P, O'Brien J. Self‐neglect and elder abuse: related phenomena? J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59: 2163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Snowdon J, Halliday G. A study of severe domestic squalor: 173 cases referred to an old age psychiatry service. Int Psychogeriatrics 2011; 23: 308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rodriguez CI, Herman D, Alcon J, Chen S, Tannen A, Essock S et al. Prevalence of hoarding disorder in individuals at potential risk of eviction in New York City: a pilot study. J Nerv Ment Dis 2012; 200: 91–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nutley S, Camacho M, Eichenbaum J, Nosheny R, Weiner M, Delucchi K et al. Hoarding disorder is associated with self‐reported cardiovascular/metabolic dysfunction, chronic pain and sleep apnea. J Psychiatr Res 2021; 134: 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pickens S, Burnett J, Naik AD, Holmes HM, Dyer CB. Is pain a significant factor in elder self‐neglect? J Elder Abus Negl 2006; 18: 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ayers C, Iqbal Y, Strickland K. Medical conditions in geriatric hoarding disorder patients. Aging Ment Health 2014; 18: 148–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Darke S, Duflou J. Characteristics, circumstances and pathology of sudden or unnatural deaths of cases with evidence of pathological hoarding. J Forensic Leg Med 2017; 45: 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lucini G, Monk I, Szlatenyi C. An Analysis of Fire Incidents Involving Hoarding Households. Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Massachusetts; 2009. Available from URL: https://web.wpi.edu/Pubs/E-project/Available/E-project-052209-111725/unrestricted/WPI_MFB_Hoarding_IQP_Report_22.5.09.pdf?_ga=2.140462523.960621025.1657003675-1536504298.1657003675. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ayers C, Dozier ME, Taylor CT, Mayes TL, Pittman JOE, Twamley EW. Group cognitive rehabilitation and exposure/sorting therapy: a pilot program. Cognit Ther Res 2017; 42: 315–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Millen AM, Levinson A, Linkovski O, Shuer L, Thaler T, Nick GA et al. Pilot study evaluating critical time intervention for individuals with hoarding disorder at risk for eviction. Psychiatr Serv 2020; 71: 405–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ayers C, Bratiotis C, Saxena S, Wetherell JL. Therapist and patient perspectives on cognitive‐behavioral therapy for older adults with hoarding disorder: a collective case study. Aging Ment Health 2012; 16: 915–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ayers C, Wetherell J, Golshan S, Saxena S. Cognitve‐behavioural therapy for geriatric compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther 2011; 49: 689–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fracalanza K, Raila H, Rodriguez CI. Could written imaginal exposure be helpful for hoarding disorder? A case series. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2021; 29: 100637. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mathews CA, Uhm S, Chan J, Gause M, Franklin J, Plumadore J et al. Treating hoarding disorder in a real‐world setting: results from the Mental Health Association of San Francisco. Psychiatry Res 2016; 30: 331–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Turner K, Steketee G, Nauth L. Treating elders with compulsive hoarding: a pilot program. Cogn Behav Pract 2010; 17: 449–57. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Weiss ER, Landers A, Todman M, Roane DM. Treatment outcomes in older adults with hoarding disorder: the impact of self‐control, boredom and social support. Australas J Ageing 2020; 39: 375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ayers C, Davidson EJ, Dozier ME, Twamley EW. Cognitive rehabilitation and exposure/sorting therapy for late‐life hoarding: effects on neuropsychological performance. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2020; 75: 1193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Davidson EJ, Broadnax DV, Dozier ME, Pittman JOE, Ayers C. Self‐reported helpfulness of cognitive rehabilitation and exposure/sorting therapy (CREST) for hoarding disorder. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2021; 28: 100622. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pittman JOE, Davidson EJ, Dozier ME, Blanco BH, Baer KA, Twamley EW et al. Implementation and evaluation of a community‐based treatment for late‐life hoarding. Int Psychogeriatrics 2021; 33: 977–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chou CY, Tsoh JY, Shumway M, Smith LC, Chan J, Delucchi K et al. Treating hoarding disorder with compassion‐focused therapy: a pilot study examining treatment feasibility, acceptability, and exploring treatment effects. Br J Clin Psychol 2020; 59: 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. DiMauro J, Genova M, Tolin DF, Kurtz MM. Cognitive remediation for neuropsychological impairment in hoarding disorder: a pilot study. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2014; 3: 132–8. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dissanayake S, Barnard E, Willis S. The emerging role of occupational therapists in the assessment and treatment of compulsive hoarding: an exploratory study. N Z J Occup Ther 2017; 64: 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ryninks K, Wallace V, Gregory JD. Older adult hoarders’ experiences of being helped by volunteers and volunteers’ experiences of helping. Behav Cogn Psychother 2019; 47: 697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chapin RK, Sergeant JF, Landry ST, Koenig T, Leiste M, Reynolds K. Hoarding cases involving older adults: the transition from a private matter to the public sector. J Gerontol Soc Work 2010; 53: 723–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kysow K, Bratiotis C, Lauster N, Woody SR. How can cities tackle hoarding? Examining an intervention program bringing together fire and health authorities in Vancouver. Health Soc Care Community 2020; 28: 1160–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Colpas E, De Zulueta J, Pappas D. An Analysis of Hoarding Fire Incidents and MFB Organisational Response. 2012 [cited 2019 Aug 26]. Available from URL: https://web.wpi.edu/Pubs/E-project/Available/E-project-050112-083627/unrestricted/An_Analysis_of_Hoarding_Fire_Incidents_and_MFB_Organisational_Response.pdf

- 60. Hill K, Yates D, Dean R, Stavisky J. A novel approach to welfare interventions in problem multi‐cat households. BMC Vet Res 2019; 15: 434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Koenig TL, Leiste MR, Spano R, Chapin RK. Multidisciplinary team perspectives on older adult hoarding and mental illness. J Elder Abus Negl 2013; 25: 56–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shaw T, Shah A. Squalor syndrome and psychogeriatric admissions. Int Psychogeriatrics 1996; 8: 669–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. McGuire JF, Kaercher L, Park JM, Storch EA. Hoarding in the community: a code enforcement and social service perspective. J Soc Serv Res 2013; 39: 335–44. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Franzini L, Dyer CB. Healthcare costs and utilization of vulnerable elderly people reported to adult protective services for self‐neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: 667–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Thompson C, Fernández de la Cruz L, Mataix‐Cols D, Onwumere J. Development of a brief psychoeducational group intervention for carers of people with hoarding disorder: a proof‐of‐concept study. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2016; 9: 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wilbram M, Kellett S, Beail N. Compulsive hoarding: a qualitative investigation of partner and carer perspectives. Br J Clin Psychol 2008; 47: 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sampson JM, Yeats JR, Harris SM. An evaluation of an ambiguous loss based psychoeducational support group for family members of persons who hoard: a pilot study. Contemp Fam Ther 2012; 34: 566–81. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chasson GS, Elizabeth Hamilton C, Luxon AM, De Leonardis AJ, Bates S, Jagannathan N. Rendering promise: enhancing motivation for change in hoarding disorder using virtual reality. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2020; 25: 100519. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Day MR, Leahy‐Warren P, McCarthy G. Perceptions and views of self‐neglect: a client‐centered perspective. J Elder Abus Negl. 2013; 25: 76–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Day MR, McCarthy G, Leahy‐Warren P. Professional social workers views on self‐neglect: an exploratory study. Br J Soc Work 2012; 42: 725–43. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. Working with hoarding vs. non‐hoarding clients: a survey of professionals’ attitudes and experiences. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2012; 1: 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 72. O'Brien JG, Cooney C, Bartley M, O'Neill D. Self‐neglect: a survey of old age psychiatrists in Ireland. Int psychogeriatrics 2013; 25: 2088–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Calvo P, Duarte C, Bowen J, Bulbena A, Fatjo J. Characteristics of 24 cases of animal hoarding in Spain. Anim Welf 2014; 23: 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ferreira EA, Paloski LH, Costa DB, Fiametti VS, De Oliveira CR, de Lima Argimon II et al. Animal hoarding disorder: a new psychopathology? Psychiatry Res 2017; 258: 221–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ockenden EM, De Groef B, Marston L. Animal hoarding in Victoria, Australia: an exploratory study. Anthrozoos 2014; 27: 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Patronek GJ. Hoarding of animals: an under‐recognized public health problem in a difficult‐to‐study population. Public Health Rep 1999; 114: 81–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Elliott R, Snowdon J, Halliday G, Hunt GE, Coleman S. Characteristics of animal hoarding cases referred to the RSPCA in New South Wales, Australia. Aust Vet J 2019; 97: 149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Diefenbach GJ, DiMauro J, Frost R, Steketee G, Tolin DF. Characteristics of hoarding in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 21: 1043–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Luria A. The Working Brain: An Introduction to Neuropsychology. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Stuss D. Biological and psychological development of executive functions. Brain Cogn 1992; 20: 8–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Stuss D, Benson D. Neuropsychological studies of the frontal lobes. Psychol Bull 1984; 95: 3–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Beauchamp T. Methods and principles in biomedical ethics. J Med Ethics 2003; 29: 269–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ryan C. The ethics of intervening in cases of severe domestic squalor. In: Snowdon J, Halliday G and Banerjee S, eds Severe Domestic Squalor. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2012; 150–9. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Snowdon J, Halliday G. How and when to intervene in cases of severe domestic squalor. Int Psychogeriatrics 2009; 21: 996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bibus AA III. Supererogation in social work: deciding whether to go beyond the call of duty. J Soc Work Values Ethics 2015; 12: 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hei A, Dong XQ. Association between neighborhood cohesion and self‐neglect in Chinese‐American older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65: 2720–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Abu‐Zidan FM, Abbas AK, Hefny AF. Clinical “case series”: a concept analysis. Afr Health Sci 2012; 12: 557–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fulmer T. Barriers to neglect and self‐neglect research. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: S241–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Roane DM, Landers A, Sherratt J, Wilson GS. Hoarding in the elderly: a critical review of the recent literature. Int Psychogeriatrics 2017; 29: 1077–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]