Abstract

Background and purpose

Chronic migraine is a highly disabling primary headache disorder that is the most common diagnosis of patients seen at tertiary headache centres. Typical oral preventive therapies are associated with many limitations that impact their therapeutic utility. Erenumab was the first available calcitonin gene‐related peptide monoclonal antibody in the UK. It had proven efficacy in migraine prevention in clinical trials and limited real‐world data in tertiary settings.

Methods

We audited our first 92 patients (n = 73 females) with severely disabling chronic migraine who were given monthly erenumab 70 mg sc for 6 months between December 2018 and December 2019.

Results

At 3 months, monthly migraine days were significantly reduced by a median of 4 days, and all other variables also showed significant improvement. The improvement was not affected by baseline analgesic use status. More than half of our patients experienced a clinically meaningful improvement in migraine days. No serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusions

Our real‐world data with erenumab demonstrate it is effective and well tolerated in managing patients with chronic migraine in a tertiary care setting.

Keywords: CGRP‐mAB, chronic migraine, erenumab, migraine, real‐world experience

Our real‐world data on the efficacy of erenumab for difficult‐to‐treat chronic migraine confirm a significant reduction in monthly migraine days at 3 months which go hand‐in‐hand with previously published reports.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic migraine (CM) is defined as 15 days or more of headache per month for 3 months, including at least 8 days of migraine per month [1]. CM affects between 0.9% and 2.2% of the population [2]. Those affected score worse on both validated disability measures and quality of life assessment tools, and are subject to significant socioeconomic impact due to inability to attend social functions, work absenteeism, and substantial use of health care resources [3].

Chronic migraine is an underdiagnosed condition, with only approximately 20% of patients having received a correct diagnosis. Of those diagnosed, a significant proportion did not get appropriate migraine preventive treatment [4]. In those who are being treated, common challenges associated with oral therapy include poor tolerance, low efficacy rates among patients, and low therapeutic adherence to preventive medication [5]. These factors combined lead to failure of therapy in CM [6, 7]. Before the calcitonin gene‐related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mABs) only topiramate [8] and onabotulinumtoxinA [9] had specific clinical trial data, and candesartan had limited data [10].

The identification of the role of CGRP in migraine [11, 12] and its subsequent targeting for new therapies [13] have led to the development of treatments directed at the CGRP pathway. This has included small molecule CGRP receptor antagonists, gepants [14], and mABs [15]. Erenumab is a CGRP mAB targeting the canonical CGRP receptor with proven efficacy in migraine prevention through randomized placebo‐controlled trials (RCTs) [16, 17, 18, 19], including data in patients with episodic migraine who have failed two to four previous preventives [18]. At the time of launch in the UK in September 2018, it had not been tested in CM patients who had failed more than two preventives [19].

METHODS

We audited the response of patients with CM treated with erenumab in a free‐of‐charge (FoC) access scheme at our tertiary headache centre at King's College Hospital from December 2018 until December 2019. The scheme was to run until the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence released its appraisal.

Patients

Patients were eligible to take part in the FoC scheme if they were >18 years old (there was no upper limit for age), had CM according to the International Classification for Headache Disorders–third edition (ICHD‐3) [1], and had failed to respond to at least three preventive therapies. Patients with medication overuse were not excluded.

Dosing

Patients were offered monthly (every 4 weeks) erenumab 70 mg sc injection for 3 months (12 weeks). If their monthly migraine days (MMD) did not improve by 50%, they were offered erenumab 140 mg sc monthly for a further 3 months. Collected data were reviewed for monthly headache days (MHD), MMD, rescue medication use days (RxD), Headache Impact Test‐6 (HIT‐6), Migraine Disability Assessment Scale, and adverse events (AEs).

Outcomes

We defined a responder in the FoC scheme as a CM patient whose MMD improved by at least 50% at Month 3 after treatment initiation compared to baseline MMD. MMD assessments were based on monthly diary data that we routinely use for clinical care. Patients who did not achieve at least a 50% migraine day reduction after 3 months of monthly 140‐mg injections were considered nonresponders, and treatment was stopped. Other criteria for stopping treatment were intolerable AEs, pregnancy, patient’s choice, and noncompliance with clinical advice.

Eligible patients had the abovementioned details along with potential AEs explained before taking part in the scheme, and a consent form was signed for the treatment. The primary outcome was a comparison of MMD at the end of the month following the third injection (Weeks 8 to 12) to that of baseline (Weeks −4 to 0). We calculated the proportion of participants who had their MMD reduced by 50% and 30% over the same duration.

We compared change in MMD between participants with medication overuse and those without.

Statistical analysis

Monthly headache days, MMD, and RxD were treated as discrete variables (natural numbers), whereas disability scores were treated as ordinal scales and presence of aura was reported using a categorical binary scale. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were used as summary measures. Differences were examined using Mann–Whitney tests. Proportions between groups were examined using the χ2 test. Spearman rho was used to examine correlations between baseline characteristics and outcomes. Participation in the FoC scheme was fixed and limited to patients who were eligible and during the time frame while it was active. Therefore, no power calculation was performed prior to the inclusion of patients. Significant was evaluated at p < 0.05, with Bonferroni adjustment as appropriate. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac (v27.0). Violin plots were constructed using GraphPad Prism (v9.3.1).

RESULTS

Demographics and baseline characteristics

Ninety‐two patients were started on erenumab 70 mg sc monthly injections between December 2018 and December 2019, 73 (79%) of them were females, and the median age of migraine onset was 11 years (IQR = 11–21). The patients had suffered with CM for a median of 10 years (IQR = 6–17). They had used a median of eight (IQR = 6–10) previous preventive treatments. Slightly more than half (52%, n = 48) of our patients had CM without aura, whereas 22 (24%) had CM with aura, 13 (14%) had new daily persistent headache, and the type was not available in nine (10%) patients.

Half of our cohort participants (51%, n = 47) fulfilled ICHD‐3 criteria for medication overuse [1]. Forty‐three patients (47%) had tried and failed to respond to onabotulinumtoxinA.

Three‐month and 6‐month MMD data were available for 72 and 41 patients, respectively.

Primary outcome

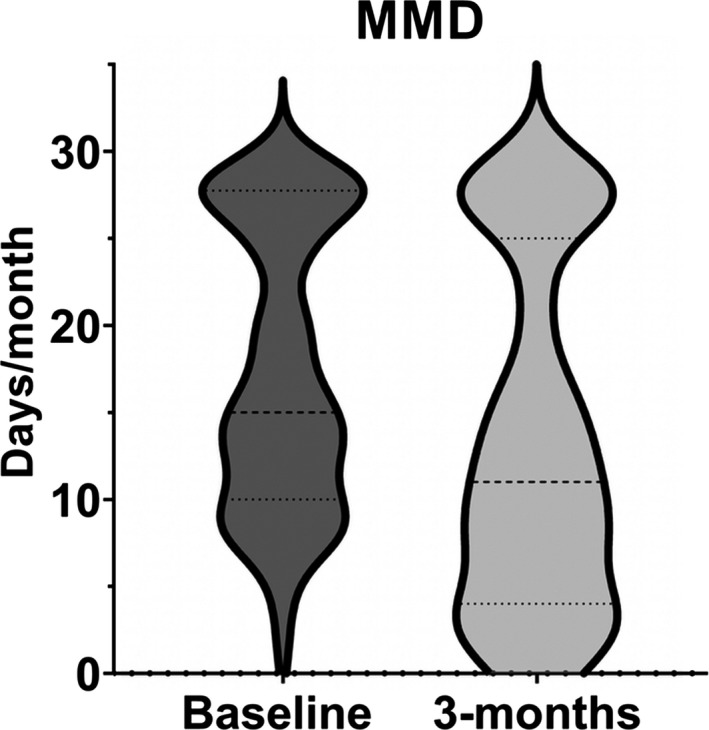

Baseline headache days, migraine days, analgesic use, and disability data are presented in Table 1. As expected for a tertiary headache centre, HIT‐6 scores were >60. Median MMD were significantly improved at 3 (Figure 1) and 6 months (−4 days and −9 days, respectively, p < 0.001). The MMD 30% and 50% responder rates at 3 months were 53% (n = 38) and 36% (n = 26), respectively (

TABLE 1.

Baseline data for the audited cohort

| Outcome | Patients, n | Median | IQR (Q1‐Q3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headache days | 92 | 28 | 26–28 |

| Migraine days | 92 | 15 | 10–28 |

| Analgesic days | 92 | 12 | 1–17 |

| HIT‐6 | 92 | 67 | 64–71 |

| MIDAS | 89 | 89 | 51–170 |

Abbreviations: HIT‐6, Headache Impact Test‐6; IQR, interquartile range; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment Scale.

FIGURE 1.

Violin plot showing shift in distribution after 3 months of treatment with erenumab in monthly migraine days (MMD)

Table 1).

Secondary outcomes

Response at 3 months

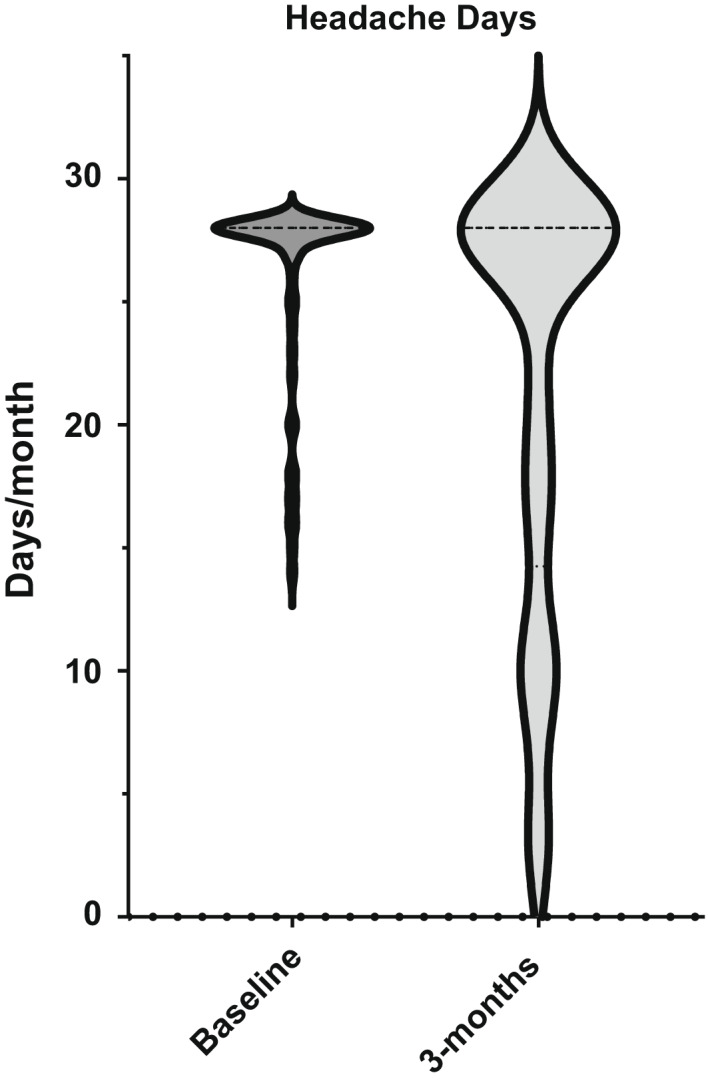

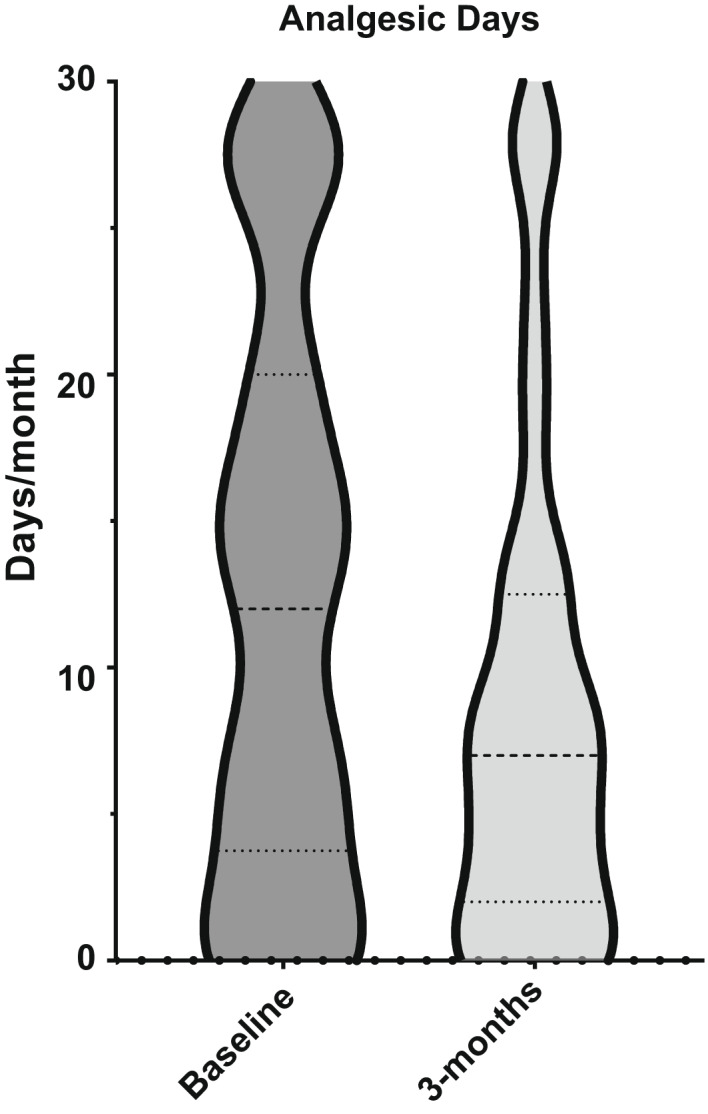

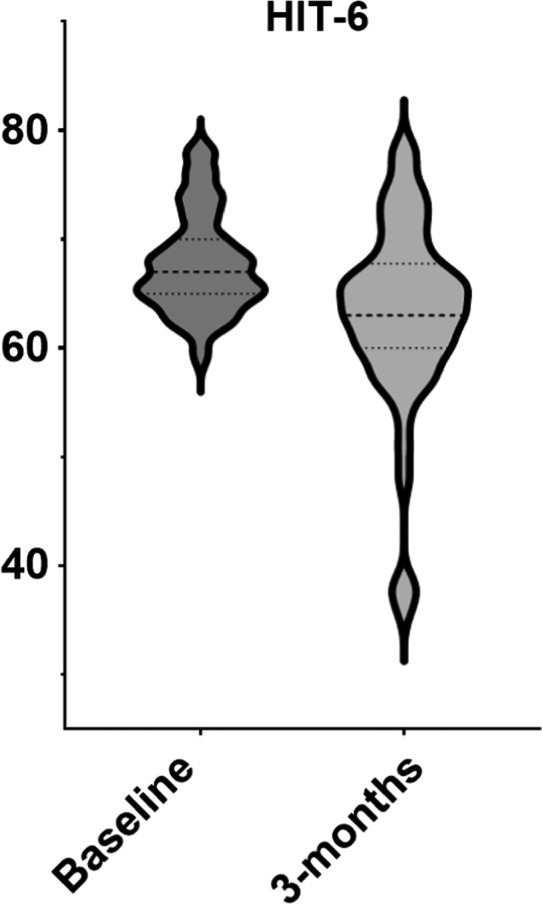

The analysis shows that MHD, monthly analgesic days (RxD), and HIT‐6 score significantly improved (Table 2 and Figures 2, 3, 4).

TABLE 2.

Outcomes at 3 months, n = 72

| Outcome | Baseline, median, IQR (Q1‐Q3) | Third month, median, IQR (Q1‐Q3) | Change, median, IQR (Q1‐Q3) | p a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHD | 28, 26‐28 | 28, 16‐28 | 0, −7‐0 | <0.001* |

| MMD | 15, 10‐28 | 11, 4‐25 | −4, −10‐0 | <0.001* , b |

| RxD | 12, 1‐17 | 7, 2‐12 | −1, −7‐0 | <0.001* |

| HIT‐6 | 67, 64‐71 | 64, 60‐68 | −3, −7‐0 | <0.001* |

| MIDAS | 90, 51‐170 | 60, 23‐162 | −7, −52‐22 | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: HIT‐6, Headache Impact Test‐6; IQR, interquartile range; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; MHD, monthly headache days; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment Scale; MMD, monthly migraine days; RxD, acute treatment days.

Wilcoxon signed‐rank test.

Primary outcome.

Statistically significant: p < 0.01.

FIGURE 2.

Violin plot showing shift in distribution after 3 months of treatment with erenumab in headache days

FIGURE 3.

Violin plot showing shift in distribution after 3 months of treatment with erenumab in days using analgesics

FIGURE 4.

Violin plot showing shift in distribution after 3 months of treatment with erenumab in Headache Impact Test‐6 (HIT‐6) score

Of the baseline characteristics in our cohort, only the number of previous preventive classes was correlated (inversely) with improvement in MMD at 3 months (r s = −0.33, p = 0.004; Table 3). After testing assumptions for simple linear regression with a P‐P plot and scatterplot, the clinical value (r 2 = 0.106) of that relationship is minimal.

TABLE 3.

Correlation of baseline characteristics of cohort with outcome at 3 months

| Measure | Age | CM duration | Preventive classes, n | MHD | RxD | HIT‐6 | MIDAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman rho correlation co efficient | −0.87 | 0.166 | −0.33 | −0.209 | 0.123 | 0.109 | −0.08 |

| Significance (two‐tailed) | 0.47 | 0.4 | 0.004* | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.51 |

| n | 72 | 28 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 71 | 71 |

Abbreviations: CM, chronic migraine; HIT‐6, Headache Impact Test‐6; MHD, monthly headache days; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment Scale; RxD, acute treatment days.

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level.

Response at 6 months

Data were available on 42 patients at 6 months; 50% (n = 21) of that cohort had their monthly erenumab escalated to 140 mg, as they did not fulfil our criteria for initial response.

The improvement in headache variables was still sustained at 6 months, and the change in disability measures was equally significant (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Outcomes at 6 months, n = 42

| Outcome | Baseline, median, IQR (Q1‐Q3) | Sixth month, median, IQR (Q1‐Q3) | Change, median, IQR | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHD | 28, 26‐28 | 20, 11‐28 | −5, 11‐ | <0.001* , a |

| MMD | 15, 10‐28 | 5, 2‐12 | −10, 7.1 | <0.001* , a |

| RxD | 12, 1‐17 | 6, 2‐8 | −5, 6.5 | <0.001* , a |

| HIT‐6 | 67, 64‐71 | 63, 58‐68 | −5, 7.5 | 0.002* , a |

| MIDAS | 90, 51‐170 | 53, 9‐106 | −39, 72.7 | 0.004* , a |

Abbreviations: HIT‐6, Headache Impact Test‐6; IQR, interquartile range; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; MHD, monthly headache days; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment Scale; MMD, monthly migraine days; RxD, acute treatment days.

Statistically significant: p < 0.01.

Wilcoxon signed‐rank test.

Effect of medication overuse on responses at 3 months

We compared 10 baseline characteristics between the medication overuse group and the nonoveruse group. After correction for multiple comparisons, apart from RxD, the only difference was that the medication overuse group had CM for a longer period of time (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Comparison of medication overuse and nonoveruse groups

| Characteristic/outcome |

Medication overuse group, n = 47, median, IQR (Q1‐Q3) |

Nonoveruse group, n = 45, median, IQR (Q1‐Q3) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Sex, F:M | 38:7 | 35:12 | 0.24 a |

| Age | 47, 38 to 59 | 40, 29 to 52 | 0.007 b |

| Migraine onset | 13, 10 to 18 | 14, 10 to 21 | 0.75 b |

| Duration of CM | 15, 9 to 20 | 6, 5 to 10 | 0.004 b , * |

| Previous preventives | 8, 7 to 10 | 8, 5 to 10 | 0.55 b |

| Baseline MHD | 28, 22 to 28 | 28, 28 to 28 | 0.11 b |

| Baseline MMD | 14, 10 to 23 | 17, 10 to 28 | 0.35 b |

| Baseline RxD | 17, 15‐28 | 2, 0‐7 | <0.001 b , * |

| Baseline HIT‐6 | 67, 65‐70 | 67, 64‐72 | 0.9 b |

| Baseline MIDAS | 90, 50‐150 | 99, 52‐196 | 0.42 b |

| Outcome at 3 months | n = 37 | n = 35 | |

| MMD change | −6, −9‐−1 | −1, −10‐0 | 0.2 b |

| 30% MMD; n (%) | 23 (62) | 15 (42) | 0.1 a |

| MHD change | 0, 0‐0 | −1, 9‐0 | 0.2 b |

| HIT‐6 change | −2, −5‐1 | −5, −9‐0 | 0.14 b |

| MIDAS change | −18 | −15 | 0.71 b |

Abbreviations: CM, chronic migraine; F, female; HIT‐6, Headache Impact Test‐6; IQR, interquartile range; M, male; MHD, monthly headache days; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment Scale; MMD, monthly migraine days; RxD, acute treatment days.

Pearson χ2 test.

Mann–Whitney test.

p < 0.005 (corrected).

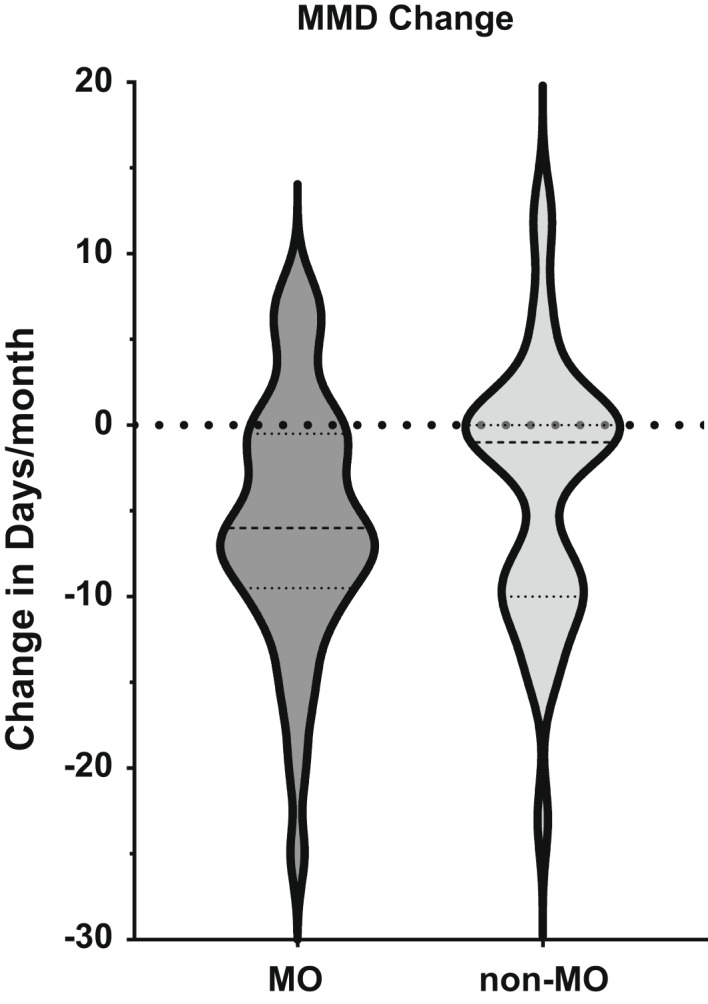

Three‐month response data were available for 72 patients, of whom 37 (51%) patients fulfilled criteria for medication overuse. There was no significant difference in the primary audit outcome, MMD change and 30% responder rate, or any of the secondary outcomes between the groups at 3 months (Table 5; Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Violin plot contrasting change in monthly migraine days (MMD) after 3 months of treatment with erenumab in patients who had had medication overuse (MO) or not (non‐MO) at baseline

Adverse events

Thirty‐eight (41%) patients reported AEs (Table 6). No new AEs were reported in our audit compared to what had been previously described in clinical trials and real‐life data. The most common side effect reported was constipation, affecting half of those who reported AEs. Of those who reported constipation, 21% had already reported constipation prior to erenumab treatment. In total, seven (8%) patients stopped their treatment due to lack of efficacy; of them, four stopped the treatment after three injections, whereas three others stopped it after six injections.

TABLE 6.

Adverse events

| Adverse event | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Constipation | 50 |

| Worsened headache | 19 |

| Skin reaction | 14 |

| Dizziness | 14 |

| Cramps | 10 |

| Bloating | 7 |

| Nausea | 7 |

| Fatigue | 7 |

| Others | 19 |

No serious AEs were reported.

DISCUSSION

Our cohort of patients is a real‐world representation of CM sufferers commonly seen in other tertiary headache centres, representing patients often excluded from RCTs for various reasons. These patients have significant disability, and a number of classes of preventive therapies have failed them. Our audit and real‐world experience that has been published (Table 7) broadly support a consistent message that erenumab reduces MMD in patients with CM in whom a range of previous preventive classes have not been effective. Tolerability has been largely good, with side effects that patients accept when present given that they are usually mild and significantly outweighed by the efficacy benefits. These data are well reflected in a recent direct head‐to‐head comparison with topiramate, where both dropout rates with side effects and efficacy favoured erenumab [20]. Our clinical experience is this efficacy and side effect advantage is likely a class effect of preventives targeting the CGRP pathway.

TABLE 7.

Comparison with previously published real‐world studies

| Characteristic | Tepper [19] | Ornello [23] | Raffaelli [24] | Lambru [21] | Scheffler [25] | Ranieri [26] | Robblee [27] | This audit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM patients at baseline, n | 381 | 84 | 139 | 162 | 74 | 21 | 95 | 92 |

| F, % | 87 | 88 | 84 | 83 | 80 | 90 | 89 | 79 |

| Completed analysis, n | 375 | 76 | 45 | 100 | na | 21 | 39 | 72 |

| Follow‐up duration, months | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Age, years | 42 | 47 | 54 | 46 | 46 | 44 | 49 | 46 |

| Aura, % | 40 | 30 | 22 | 33 | na | na | 40 | 24 |

| Medication overuse, % | 41 | 72 | na | 54 | 66 | 29 | 19 | 51 |

| Previous botulinum toxin use, % | 67 | 49 | 100 | 91 | 100 | na | 83 | 47 |

| Previous preventives, n | <3 | 88% tried 2–4 | 5 | 8 | >6 | >2 | 11 | 8 |

| Baseline MHD/MMD/RxD, days | 21/18/9 | na/20/14 | 18/11/7 | 23/20/12 | 21/16/12 | 20/10/10 | 24/18/na | 28/15/12 |

| Change in MHD/MMD/RxD, days | na/‐7/‐4 | na/‐15/‐8 | ‐5/‐5/‐6 | ‐6/‐6/‐3 | ‐6/‐5/‐3 | ‐9/‐6/‐6 | ‐7/‐9/na | 0/‐5/‐1 |

| MMD 50% responder rate | 41 | 74 | na | 35 | 42 | na | 55 | 36 |

| Constipation rate, % | 4 | 14 | 19 | 20 | 24 | 10 | 24 | 50 |

Abbreviations: CM, chronic migraine; F, female; MHD, monthly headache days; MMD, monthly migraine days; na, not available; RxD, acute treatment days.

Since its launch in 2018, there have been a number of articles discussing postmarketing clinical experience with erenumab in CM, with MHD or MMD being the main focus of the reports. Similar to previously published RCTs [19, 21] and real‐life data with erenumab in CM (Table 7), our data confirm the medication is effective in reducing CM burden, as proven by significant improvement in all variables used to account for disability and severity of the condition at 3 months. Importantly, the improvement at 6 months in disability measures was still significant despite the small sample size. Although MMD at baseline in our group are comparable to that of published work, half of our cohort complained of constant daily headache, yet the medication overuse rate was similar. This likely reflects cultural aspects of treatment.

At 3 months, the most pronounced change was in median MMD reduction, which became clearer at 6 months. Broadly, the data imply that a longer duration of exposure to CGRP pathway blockade may be clinically useful. More than half of our patients sustained a clinically meaningful improvement in migraine days at 3 months. The only baseline characteristics we could associate with improvement was the number of previous preventive classes, which was inversely related. However, this accounted for a small amount of variance, approximately 11%, suggesting there is little reason to preclude even the most apparently refractory patients from CGRP pathway mABs. Medication overuse of analgesics, as seen previously [22, 23], does not seem to have any impact in response at 3 months.

Of AEs, constipation was prominent. Importantly, we probed for bowel habits at baseline and reviewed the same question after treatment. In general, the prevalence of constipation in real‐life data is significantly higher than that published in controlled trials. Differences in constipation rate may, in part, be accounted for by baseline differences in dietary habits, with Italian studies [24] reporting a rate almost half that in Northern Europe and North America [25, 26]. This still does not explain fully the difference between the rate in our audit and that reported elsewhere in the UK [23]. Our patients were counselled about risk of constipation during consent, then incidence of that AE was specifically checked for at each follow‐up visit. Perhaps probing for side effects resulted in a measurable difference here.

LIMITATIONS

our prospective analysis summarizes findings of an open‐label audit; hence, nonblinding, lack of placebo or active comparator, expectation bias, and sample size would, certainly, have had an impact on our results. Our effect size is very difficult to account for. An underlying theme is the relative benefit patients ascribe to efficacy in a context of modest and tolerable side effects. Considering ongoing real‐world experience is essential to optimize the use of these new medicines.

In conclusion, our real‐world data confirm the efficacy of erenumab in managing patients with CM in whom a range of previous medicines had not been useful. The new data complement previously published reports, supporting the utility of CGRP pathway mABs in preventive treatment of CM. Although several side effects were recorded in our study, there were no serious side effects, an indication of a good level of tolerability of erenumab.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

David Moreno‐Ajona, María Dollores Villar‐Amrtínez and Fiona Greenwood have do not have any conflict of interest to disclose.Modar Khalil received honoraria for speaking from Allergan and Novartis, all these activities are unrelated to this submitted work. Jan Hoffmann is consulting for and/or serves on advisory boards of Allergan, Autonomic Technologies Inc., Cannovex BV, Chordate Medical AB, Eli Lilly, Hormosan Pharma, Lundbeck, Novartis, Sanofi and Teva. He has received honoraria for speaking from Allergan, Autonomic Technologies Inc., Chordate Medical AB, Novartis and Teva. He received personal fees for Medico‐legal work as well as from Sage publishing, Springer Healthcare and Quintessence Publishing. He receives research support from Bristol‐Myers‐Squibb. All these activities are unrelated to the submitted work. Peter J. Goadsby reports grants and personal fees from Amgen and Eli‐Lilly and company, and personal fees from Alder Biopharmaceuticals, Allergan, Autonomic Technologies Inc., Biohaven Pharmaceuticals Inc., Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, Electrocore LLC, eNeura, Novartis, Teva Pharmaceuticals and Trigemina Inc., and personal fees from Medico‐legal work, Massachusetts Medical Society, Up‐to‐Date, Oxford University Press and Wolters Kluwer; and a patent Magnetic stimulation for headache assigned to eNeura without fee.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Modar Khalil: Conceptualization (lead), data curation (lead), formal analysis (lead), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), project administration (lead), resources (equal), software (equal), visualization (equal), writing–original draft (lead), writing–review and editing (lead). David Moreno‐Ajona : Conceptualization (supporting), data curation (equal), formal analysis (supporting), investigation (equal), methodology (supporting), project administration (equal), visualization (supporting), writing–review and editing (supporting). María Dolores Villar‐Martínez: Formal analysis (equal), project administration (equal), writing–review and editing (equal). Fiona Greenwood: Data curation (equal), project administration (equal), resources (supporting), validation (supporting), visualization (supporting), writing–review and editing (supporting). Jan Hoffmann: Conceptualization (equal), investigation (supporting), methodology (supporting), project administration (equal), supervision (lead), validation (equal), visualization (supporting), writing–review and editing (supporting). Peter J. Goadsby: Conceptualization (equal), data curation (supporting), formal analysis (supporting), investigation (equal), methodology (equal), project administration (equal), resources (supporting), supervision (lead), visualization (equal), writing–review and editing (equal).

Khalil M, Moreno‐Ajona D, Villar‐Martínez MD, Greenwood F, Hoffmann J, Goadsby PJ. Erenumab in chronic migraine: Experience from a UK tertiary centre and comparison with other real‐world evidence. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29:2473–2480. doi: 10.1111/ene.15364

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. Our data availability is governed by the UK general data protection regulations.

REFERENCES

- 1. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) . The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38:1‐211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Manack AN, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine: epidemiology and disease burden. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(1):70‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):301‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diener HC, Solbach K, Holle D, Gaul C. Integrated care for chronic migraine patients: epidemiology, burden, diagnosis and treatment options. Clin Med (Lond). 2015;15(4):344‐350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, et al. Assessing barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: Results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache. 2016;56:821‐834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Gillard P, Hansen RN, Devine EB. Adherence to oral migraine‐preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6):478‐488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agostoni EC, Barbanti P, Calabresi P, et al. Current and emerging evidence‐based treatment options in chronic migraine: a narrative review. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate for the treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Headache. 2007;47(2):170‐180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2010;50(6):921‐936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stovner LJ, Linde M, Gravdahl GB, et al. A comparative study of candesartan versus propranolol for migraine prophylaxis: a randomised, triple‐blind, placebo‐controlled, double cross‐over study. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:523‐532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goadsby PJ, et al. Release of vasoactive peptides in the extracerebral circulation of man and the cat during activation of the trigeminovascular system. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:193‐196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R. Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of humans during migraine headache. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:183‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ho TW, Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ. CGRP and its receptors provide new insights into migraine pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:573‐582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moreno‐Ajona D, et al. Gepants, calcitonin‐gene related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists: what could be their role in migraine treatment? Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33:309‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castle D, Robertson NP. Monoclonal antibodies for migraine: an update. J Neurol. 2018;265(6):1491‐1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, et al. A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2123‐2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dodick DW, et al. ARISE: a phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(6):1026‐1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri‐Minet M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two‐to‐four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet. 2018;392:2280‐2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tepper SJ, et al. A phase 2, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of erenumab in chronic migraine prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:425‐434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ashina M, Tepper S, Brandes JL, et al. Efficacy and safety of erenumab (AMG334) in chronic migraine patients with prior preventive treatment failure: a subgroup analysis of a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(10):1611‐1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lambru G, Hill B, Murphy M, Tylova I, Andreou AP. A prospective real‐world analysis of erenumab in refractory chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tepper SJ, Diener H‐C, Ashina M, et al. Erenumab in chronic migraine with medication overuse: subgroup analysis of a randomized trial. Neurology. 2019;92(20):2309‐2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ornello R, Casalena A, Frattale I, et al. Real‐life data on the efficacy and safety of erenumab in the Abruzzo region, central Italy. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Raffaelli B, Kalantzis R, Mecklenburg J, et al. Erenumab in chronic migraine patients who previously failed five first‐line oral prophylactics and onabotulinumtoxinA: a dual‐center retrospective observational study. Front Neurol. 2020;11:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scheffler A, Messel O, Wurthmann S, et al. Erenumab in highly therapy‐refractory migraine patients: first German real‐world evidence. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ranieri A, Alfieri G, Napolitano M, et al. One year experience with erenumab: real‐life data in 30 consecutive patients. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(2):505‐506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robblee J, Devick KL, Mendez N, Potter J, Slonaker J, Starling AJ. Real‐world patient experience with erenumab for the preventive treatment of migraine. Headache. 2020;60(9):2014‐2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions. Our data availability is governed by the UK general data protection regulations.