Abstract

Background

The European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) Guidelines were revised in 2021 for the 17th time with updates on all aspects of HIV care.

Key points of the Guidelines update

Version 11.0 of the Guidelines recommend six first‐line treatment options for antiretroviral treatment (ART)‐naïve adults: tenofovir‐based backbone plus an unboosted integrase inhibitor or plus doravirine; abacavir/lamivudine plus dolutegravir; or dual therapy with lamivudine or emtricitabine plus dolutegravir. Recommendations on preferred and alternative first‐line combinations from birth to adolescence were included in the new paediatric section made with Penta. Long‐acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine was included as a switch option and, along with fostemsavir, was added to all drug–drug interaction (DDI) tables. Four new DDI tables for anti‐tuberculosis drugs, anxiolytics, hormone replacement therapy and COVID‐19 therapies were introduced, as well as guidance on screening and management of anxiety disorders, transgender health, sexual health for women and menopause. The sections on frailty, obesity and cancer were expanded, and recommendations for the management of people with diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk were revised extensively. Treatment of recently acquired hepatitis C is recommended with ongoing risk behaviour to reduce transmission. Bulevirtide was included as a treatment option for the hepatitis Delta virus. Drug‐resistant tuberculosis guidance was adjusted in accordance with the 2020 World Health Organization recommendations. Finally, there is new guidance on COVID‐19 management with a focus on continuance of HIV care.

Conclusions

In 2021, the EACS Guidelines were updated extensively and broadened to include new sections. The recommendations are available as a free app, in interactive web format and as an online pdf.

Keywords: antiretroviral treatment, children, comorbidities, COVID‐19, drug–drug interactions, European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) Guidelines, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, HIV, opportunistic infections, Penta

INTRODUCTION

In 2021 the European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) Guidelines were published for the 17th time. Version 11.0 comes at a time when the clinical management of people with HIV has been under substantial pressure due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. To acknowledge the many challenges brought by the pandemic, the Guidelines were expanded in 2021 with recommendations underlining the importance of avoiding disruption to HIV care, ensuring close contact with other healthcare professionals, such as the primary care physician, and maintenance of current antiretroviral treatment (ART) regimens. To meet the current needs of everyone involved with HIV care, a separate COVID‐19 sub‐section with recommendations on key COVID‐19 aspects in the context of HIV was introduced, as part of the opportunistic infection (OI) section, along with a new drug–drug interaction (DDI) table including COVID‐19 therapeutics.

The EACS Guidelines continue to aim to provide easily accessible, systematic and comprehensive recommendations across wide geographical settings. Based on a request to expand the Guidelines from an adult focus only, the 2021 revision includes recommendations on ART in children and adolescents made in collaboration with Penta (formerly the Paediatric European Network for the Treatment of AIDS). Future updates will expand this section to include other key perspectives of HIV management in children and adolescents.

Version 11.0 of the Guidelines consists of an overview table covering major aspects of HIV management and six main sections with more detailed recommendations on ART in adults and children, DDIs, drug dosage, prescribing in older individuals, diagnosis, monitoring and treatment of comorbidities, coinfections, COVID‐19 and opportunistic diseases. All sections have undergone major revisions.

Previous EACS Guidelines were published both electronically and in print as a booklet. From 2021, the Guidelines are exclusively available electronically, but in several different formats including a free app for mobile devices, an interactive website and an online pdf (https://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs‐guidelines/). Comments on the Guidelines can be directed to guidelines@eacsociety.org.

METHODS

All recommendations in the EACS Guidelines are continuously revised to ensure they remain up to date and cover the most relevant questions from everyday clinical practice.

As previously described, the Guidelines are developed based on evidence, and on expert opinion in any instances, where this is not available [1]. The Guidelines are reviewed by six panels of European HIV experts and governed by a leadership group consisting of a Chair, a VICE‐Chair and a Young Scientist. Community representatives are included at all stages. The Guidelines process is managed by the EACS Guidelines Chair and Coordinator working closely with the EACS Secretariat; details have previously been published [1].

Formal revisions are made annually with major revisions every other year and minor revisions in the years in between. The Guidelines are published in the autumn and translated into several additional languages. Interim updates can be carried out in real time if new essential information is released in‐between formal revisions.

The main changes for version 11.0 in each section of the Guidelines are summarized below.

ART section

Version 11.0 of the Guidelines has only two ART categories – recommended and alternative – which are shown in Table 1. EACS includes six recommended treatment options for first‐line regimens for ART‐naïve adults which include triple drug regimens consisting of tenofovir [either tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)] with either lamivudine or emtricitabine (XTC) plus dolutegravir (DTG), raltegravir (RAL), bictegravir (BIC) or doravirine (DOR); abacavir (ABC)/lamivudine (3TC) plus DTG; or dual therapy with XTC plus DTG. These drug combinations are also recommended when available in single‐tablet regimens. The alternative regimens, consisting of triple‐drug tenofovir‐based regimens in association with efavirenz (EFV), rilpivirine (RPV) or boosted darunavir (DRV/b), are to be used when none of the recommended regimens are feasible. Cobicistat‐boosted elvitegravir (EVG/c) and boosted atazanavir (ATV/b)‐based regimens, DRV/b + RAL, and ABC combinations with EFV, DRV/b or RAL are no longer considered as alternative treatment options because of either lower genetic barrier to resistance, higher toxicity or lower efficacy.

TABLE 1.

Initial combination regimen for antiretroviral therapy (ART)‐naïve adults

| Regimen | Main requirements | Additional guidance (see footnotes) |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended regimens | ||

| 2 NRTIs + INSTI | ||

|

ABC/3TC + DTG ABC/3TC/DTG |

HLA‐B*57:01‐negative HBsAg‐negative |

(I) ABC: HLA‐B*57:01, cardiovascular risk (II) Weight increase (DTG) |

| TAF/FTC/BIC | (II) Weight increase (BIC, TAF) | |

|

TAF/FTC or TDF/XTC + DTG |

(II) Weight increase (DTG, TAF) (III) TDF: prodrug types. Renal and bone toxicity. TAF dosing*** |

|

|

TAF/FTC or TDF/XTC + RAL qd or bid |

(II) Weight increase (RAL, TAF) (III) TDF: prodrug types. Renal and bone toxicity. TAF dosing*** (IV) RAL dosing |

|

| 1 NRTI + INSTI | ||

| XTC + DTG or 3TC/DTG |

HBsAg‐negative HIV viral load < 500 000 copies/mL Not recommended after PrEP failure |

(II) Weight increase (DTG) (V) 3TC/DTG not after PrEP failure |

| 2 NRTIs + NNRTI | ||

|

TAF/FTC or TDF/XTC + DOR or TDF/3TC/DOR |

(II) Weight increase (TAF) (III) TDF: prodrug types. Renal and bone toxicity. TAF dosing*** (VI) DOR: caveats, HIV‐2 |

|

| Alternative regimens | ||

| 2 NRTIs + NNRTI | ||

|

TAF/FTC or TDF/XTC + EFV or TDF/FTC/EFV |

At bedtime or 2 h before dinner |

(II) Weight increase (TAF) (III) TDF: prodrug types. Renal and bone toxicity. TAF dosing*** (VII) EFV: neuropsychiatric adverse events. HIV‐2 or HIV‐1 group 0 |

|

TAF/FTC or TDF/XTC + RPV or TAF/FTC/RPV or TDF/FTC/RPV |

CD4 count > 200 cells/µL, HIV viral load < 100 000 copies/mL Not on gastric pH‐increasing agents With food |

(II) Weight increase (TAF) (III) TDF: prodrug types. Renal and bone toxicity. TAF dosing*** (VIII) RPV: HIV‐2 |

| 2 NRTIs + PI/r or PI/c | ||

|

TAF/FTC or TDF/XTC + DRV/c or DRV/r or TAF/FTC/DRV/c |

With food |

(II) Weight increase (TAF) (III) TDF: prodrug types. Renal and bone toxicity. TAF dosing*** (IX) DRV/r: cardiovascular risk (X) Boosted regimens and drug–drug interactions**** |

(I) ABC contraindicated if HLA‐B*57:01‐positive. Even if HLA‐B*57:01‐negative, counselling on HSR risk is still mandatory. ABC should be used with caution in people with a high CVD risk (>10%).

(II) Treatment with INSTIs or TAF may be associated with weight increase.

(III) In certain countries, TDF is labelled as 245 mg rather than 300 mg to reflect the amount of the prodrug (tenofovir disoproxil) rather than the fumarate salt (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate). There are available generic forms of TDF, which instead of fumarate use phosphate, maleate and succinate salts. They can be used interchangeably.

When available, combinations containing TDF can be replaced by the same combinations containing TAF. TAF is used at 10 mg when co‐administered with drugs that inhibit P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp), and at 25 mg when co‐administered with drugs that do not inhibit P‐gp.

The decision whether to use TDF or TAF depends on individual characteristics as well as availability.

If the ART regimen does not include a booster, TAF and TDF have a similar short‐term risk of renal adverse events leading to discontinuation and bone fractures.

TAF*** should be considered as a first choice**** over TDF in individuals with: established or high risk of CKD; co‐administration of medicines with nephrotoxic drugs or prior TDF toxicity, osteoporosis/progressive osteopenia, high Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) score or risk factors; history of fragility fracture,

(IV) RAL can be given as RAL 400 mg bid (twice daily) or RAL 1200 mg (two, 600 mg tablets) qd (once daily). Note: RAL qd should not be given in presence of an inducer (i.e. TB drugs, antiepileptics) or divalent cations (i.e. calcium, magnesium, iron), in which case RAL should be used bid.

(V) HIV infections occurring in the context of pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) failure may be associated with resistance‐associated mutations. 3TC/DTG may be used in this context only if there is no documented resistance in genotypic test.

(VI) DOR is not active against HIV‐2. DOR has not demonstrated non‐inferiority to INSTI. There is risk of resistance‐associated mutations in case of virological failure. Results of genotypic resistance test are necessary before starting DOR.

(VII) EFV: not to be given if there is a history of suicide attempts or mental illness; not active against HIV‐2 and HIV‐1 group O strains.

(VIII) RPV is not active against HIV‐2.

(IX) A single large study has shown increase in CVD risk with cumulative use of DRV/r, not confirmed in smaller studies.

(X) Boosted regimens with RTV or COBI are at higher risk of drug–drug interactions.

***There are limited data on use of TAF with estimated glomerular filtration rate < 10 mL/min.

****Expert opinion pending clinical data.

Abbreviations: 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; BIC, bictegravir; COBI, cobicistat; /c, boosted by cobicistat; DOR, doravirine; DRV, darunavir; DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PI, protease inhibitor; /r, boosted by ritonavir; RAL, raltegravir; RPV, rilpivirine; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; XTC, lamivudine or emtricitabine.

Adapted from EACS Guidelines v.11.0 [16].

Before initiating ART it is important to consider different instances such as treatment‐limiting comorbidities, DDIs or whether a woman is wishing to conceive or is pregnant – circumstances for which there is specific management guidance. The 2021 update includes recommendations in case of incident HIV in a person receiving pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP); it is proposed to switch to a triple‐drug regimen including two nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and a drug with high barrier to resistance such as a second‐generation integrase inhibitor (INSTI) or DRV/b. Initial treatment in this context should avoid 3TC/DTG and may be adjusted following results of resistance testing.

For virologically suppressed persons, bi‐monthly injections with long‐acting cabotegravir (CAB‐LA) plus RPV have been included as a switch option [2]. Lamivudine plus ATV/b is no longer recommended because of limited data and available alternatives with less toxicity and DDIs.

The section on virological failure has been updated, including more detailed guidance on possible regimen combinations when there are demonstrated resistance mutations.

For treatment of pregnant women living with HIV or women considering pregnancy, the EACS recommends that the ART regimen should be discussed with the person and individualized, taking into account tolerability and possible adherence issues, as well as weighing it up against the potential risk from ART exposure or suboptimal pharmacokinetics in pregnancy. This includes discussing DTG with women considering becoming pregnant or if it is to be used in the first 6 weeks of pregnancy. The 2021 version has included TAF as a drug option among recommended/alternative regimens after 14 weeks of pregnancy [3]. There are four current recommended regimens for ART‐naïve pregnant women, including triple‐drug tenofovir‐based regimens in combination with DTG, RAL twice daily (bid) or DRV/r bid, or ABC/3TC plus DTG. Among these, EACS favours regimens including an INSTI which has a better safety profile.

For those coinfected with tuberculosis (TB), EACS Guidelines are aligned with the updated guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) and therefore it is recommended that ART should be started as soon as possible (within 2 weeks of initiating TB treatment) regardless of CD4 count, with the exception of TB meningitis [4]. There are no significant changes in ART recommended in this context: EFV in combination with two NRTIs remains the preferred option.

The section on PrEP has been updated to include on demand (2:1:1 dosing) for cisgender men based on expert opinion. PrEP may be continued during pregnancy and breastfeeding if the risk of acquiring HIV persists.

DDI and other prescribing issues section

The DDI tables, which provide an overview of the interaction potential between individual antiretroviral drugs and the most commonly used comedications within a therapeutic area, have been expanded to include DDIs with anti‐tuberculosis drugs, anxiolytics, hormone replacement therapy and COVID‐19 therapies.

Recently approved antiretrovirals have been added: fostemsavir, oral CAB and intramuscular CAB‐LA plus RPV. Intramuscular administration of CAB and RPV eliminate DDIs occurring at the gastrointestinal level due to changes in gastric pH, chelation with divalent cations or inhibition/induction of drug‐metabolizing enzymes or transporters. However, DDIs can still occur at the hepatic level. Importantly, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract does not mitigate the magnitude of DDIs notably with drugs inducing metabolism [5]. The Guidelines present a list of medications that interact with the oral but not the intramuscular administration of CAB and RPV.

Detailed information on DDIs can be found on the University of Liverpool’s website (www.hiv‐druginteractions.org).

Comorbidity section

The prevention and management of comorbidities remains the largest section of the Guidelines. This update acknowledges the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on routine healthcare, provides broad recommendations and underscores the importance of shared care and consultation when appropriate.

Of particular relevance during the pandemic, the Guidelines have focused on mental health with the addition of a section on the screening and management of anxiety disorders. Given the high prevalence of anxiety disorders in people with HIV, it is recommended to consider screening for anxiety at each clinic attendance, especially in those particularly at risk (e.g. family history of anxiety disorders, alcohol excess and in those with multiple stressful life events). A treatment strategy based on the degree of anxiety details the use of relaxation techniques, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy and lists psychotherapeutic interventions.

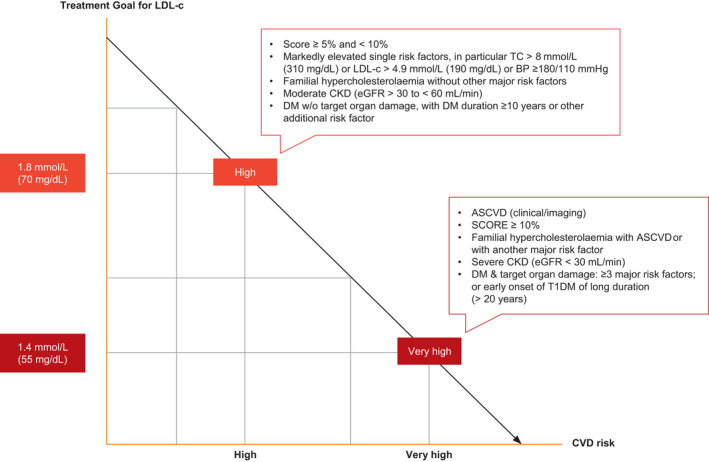

Several sections have undergone a significant revision. An updated approach to the management of diabetes mellitus provides an algorithm for second‐line therapy in those with predominantly atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) versus heart failure or chronic kidney disease. Suggested intensification strategies for those with HbA1C above target are outlined in alignment with current European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) / American Diabetes Association Guidelines [6]. In addition to those with established CVD, primary prevention with aspirin is recommended in those with diabetes mellitus or those at high and very high risk of CVD. Criteria for high and very high risk of CVD are included along with a new figure highlighting treatment goals for low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in these groups, Figure 1 [7]. The drug sequencing for hypertension management has been updated to include the use of dual combination therapy as first‐line management in alignment with the European Society of Hypertension [8].

FIGURE 1.

Treatment goal for low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐c) for people with very high and high cardiovascular disease risk. ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BP, blood pressure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; SCORE, Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation; T1DM, type 1 DM; T2DM, type 2 DM; TC, total cholesterol. Moderate CVD risk: young people (T1DM < 35 years; T2DM < 50 years) with DM duration < 10 years, without other risk factors; calculated SCORE > 1% and < 5% for 10‐year risk of fatal CVD/; LDL‐c goal is 2.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dL). Low CVD risk: calculated SCORE < 1% for 10‐year risk of fatal CVD; LDL‐c goal 3.0 mmol/L (116 mg/dL). Adapted from Mach et al. and EACS Guidelines v.11.0 [7, 16]

The frailty section, introduced in v.10.0 of the Guidelines, was expanded to highlight recommendations for managing older people with HIV. Highlighting the issues of polypharmacy and drug toxicity in older people, this section offers guidance on de‐prescribing medication. Comprehensive information on screening for frailty, falls risk, formal frailty assessment and management is also included. The obesity section was updated with an approach to the management of weight gain as well as obesity. As well as highlighting the impact of ART, clear aims of interventions are detailed. Referral to specialist‐led obesity programmes is recommended, particularly if pharmacological intervention is required.

Cancer screening recommendations have updated age thresholds for breast and colorectal cancer screening in line with recommendations in the general population. Information on lung cancer screening where local programmes are in place is provided. Recommendations on opportunistic infection prophylaxis for those undergoing cancer treatment is now included with reference to the OI section.

The section on sexual health emphasizes the importance and effectiveness of 'undetectable = untransmittable' (U=U) in the context of sero‐different partners and reducing HIV transmission, and reinforces the importance of discussing this with all people with HIV. It also includes a new section on women's sexual health, recommending proactive, annual screening for menopausal symptoms in women aged > 40 years and detailing general health risk assessment. Treatment options for menopausal women are summarized and premature ovarian failure is highlighted. The treatment of sexual dysfunction has been updated and expanded. Finally, special considerations for transgender people are now included.

Viral hepatitis coinfection section

No new direct‐acting antivirals (DAAs) have been licensed for the treatment of hepatitis C (HCV) since the publication of the last version of these Guidelines. In line with the updated EASL guidelines, HCV genotype determination is not mandatory if pan‐genotypic regimens are foreseen. The tables on HCV treatment options (Table 2) and DDIs have been updated. The table on ‘HCV treatment options if preferred treatments are not available’ was removed as most of these drugs are no longer in use.

TABLE 2.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment options in HCV/HIV‐coinfected people

| Preferred DAA HCV treatment options (except for people pre‐treated with protease or NS5A inhibitors) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV GT | Treatment regimen | Treatment duration and RBV usage | ||

| Non‐cirrhotic | Compensated cirrhotic | Decompensated cirrhotics CTP class B/C | ||

| 1 and 4 | EBR/GZR | 12 weeksa | Not recommended | |

| GLE/PIB | 8 weeks | 8–12 weeksb | Not recommended | |

| SOF/VEL | 12 weeks | 12 weeks with RBVi | ||

| SOF/LDV +/‐ RBV | 8–12 weeks without RBVc | 12 weeks with RBVd | 12 weeks with RBVi | |

| 2 | GLE/PIB | 8 weeks | 8–12 weeksb | Not recommended |

| SOF/VEL | 12 weeks | 12 weeks with RBVi | ||

| 3 | GLE/PIB | 8 weekse | 8–12 weeksb,e | Not recommended |

| SOF/VEL +/‐ RBV | 12 weeksf | 12 weeks with RBVg | 12 weeks with RBVi | |

| SOF/VEL/VOX | ‐ | 12 weeks | Not recommended | |

| 5 and 6 | GLE/PIB | 8 weeks | 8–12 weeksb | Not recommended |

| SOF/LDV +/‐ RBV | 12 weeks +/‐ RBVh | 12 weeks with RBVd | 12 weeks with RBVi | |

| SOF/VEL | 12 weeks | 12 weeks with RBVi | ||

Adapted from EACS Guidelines v.11.0 [16].

Abbreviations: DAA, direct‐acting antiviral; EBR, elbasvir; GLE, glecaprevir; GZR, grazoprevir; LDV, ledispasvir; PIB, pibrentasvir; RAS, resistance associated substitutions; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir; VEL, velpatasvir; VOX, voxilaprevir.

aIn people with HIV with GT1a with baseline HCV‐RNA < 800 000 IU/mL and/or absence of NS5A RASs, as well as in treatment‐naïve people with HIV with GT4 with HCV‐RNA < 800 000 IU/mL. In GT 1b treatment‐naïve people with HIV with F0–F2 fibrosis, 8 weeks can be considered.

b8 weeks of treatment can be considered in treatment‐naïve people with HIV.

c8 weeks of treatment without RBV only in treatment‐naïve people with HIV with F < 3 and baseline HCV‐RNA < 6 million IU/mL.

dRBV can be omitted in treatment‐naïve or treatment‐experienced people with HIV with compensated cirrhosis without baseline NS5A RAS. In those intolerant to RBV, treatment may be prolonged to 24 weeks.

eTreatment duration in HCV GT3 who failed previous treatment with IFN and RBV ± SOF or SOF and RBV should be 16 weeks.

fIn treatment‐experienced people with HIV, RBV should be added unless NS5A RASs are excluded; if these people are intolerant to RBV, treatment may be prolonged to 24 weeks without RBV.

gIf RAS testing is available and demonstrates absence of NS5A RAS Y93H, RBV can be omitted in treatment‐naïve people with HIV with compensated cirrhosis.

hIn treatment‐experienced people (exposure to IFN/RBV/SOF) with HIV, add RBV treatment for 12 weeks or prolong treatment to 24 weeks without RBV.

iIn people intolerant to RBV, treatment may be prolonged to 24 weeks.

In line with the recent ‘Recommendations on recently acquired and early chronic hepatitis C in MSM’ [9], immediate treatment of recently acquired HCV is recommended among people living with HIV with ongoing risk behaviour to reduce onward transmission. If immediate treatment is not indicated, we refer to the algorithm on recently acquired HCV infection displayed in these Guidelines. We added bulevirtide as a treatment option for the hepatitis Delta virus (HDV) as it received a conditional marketing authorization by the European Medicines Agency. Where this drug is available, the treatment should be considered in those with compensated liver disease and replicating HDV. Such treatment should preferably be carried out in large centres by physicians experienced with this treatment.

OI and COVID‐19 section

The major change within the OI section in 2021 was a new sub‐section on the management of HIV and COVID‐19. It covers epidemiology, risk factors for severe COVID‐19, HIV care during a pandemic, management of COVID‐19, management of HIV while on treatment for COVID‐19, management of long‐term symptoms and prophylaxis of COVID‐19 [10]. Consequently, the title of the section was changed to ‘Opportunistic infections and COVID‐19’.

Other minor edits have been made. The table on ‘When to start ART in the presence of OIs’ no longer contains CD4 thresholds and specific recommendations for cytomegalovirus (CMV) end‐organ disease have been removed from this table. A specific remark for ART initiation in those with TB meningitis has been made.

Cryptococcosis prophylaxis with fluconazole at CD4 count < 100 cells/μL and positive cryptococcal serum antigen was added to the table ‘Primary prophylaxis of OIs according to stage of immunodeficiency’, for consistency.

Based on recent evidence, it is now possible to stop secondary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PCP) at CD4 counts > 100 cells/μL, if viral load has been undetectable for > 3 months [11].

Recommendations on management of drug‐resistant TB were adjusted to be consistent with the most recent WHO recommendations (2020) and now includes all‐oral regimes of shorter duration [12]. An alternative 4‐month regimen containing rifapentine for treatment of drug‐susceptible TB was added, based on new evidence [13].

Paediatric HIV treatment section

This new section, developed in collaboration between EACS and Penta aims to align ART guidance in Europe for children and young people with HIV with that for adults. Penta has been the lead organization for European paediatric HIV treatment guidelines for many years and this new combined Penta/EACS guidance is an exciting step towards improved harmonization of paediatric and adult recommendations.

The paediatric section provides updated guidance for selection of preferred and alternative first‐line combinations from birth to adolescence (Table 3). This has taken into account the latest evidence from the multinational ODYSSEY trial which demonstrated superiority of DTG over other third agents for both first‐ and second‐line therapy in children [14]. Alongside licensing of new child‐friendly formulations of DTG down to 4 weeks and 3 kg, these data have supported an increased emphasis on the use of DTG as first‐line preferred agent at all ages beyond the neonatal period. Recommendations for the use of ABC at ages younger than 3 months have also been provided, increasing the NRTI options for very young infants.

TABLE 3.

Preferred and alternative first‐line antiretroviral therapy (ART) options in children and adolescents

| Age | Backbone | Third agent (in alphabetical order) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred | Alternative | Preferred | Alternative | |

| 0–4 weeks | ZDVa + 3TC | ‐ |

LPV/rb,c NVPc RALc |

‐ |

| 4 weeks–3 years | ABCd + 3TCe |

ZDVa + 3TCf TDFg + 3TC |

DTGh |

LPV/r NVP RAL |

| 3–6 years | ABCd +3TCe |

TDF + XTCi ZDV + XTCi |

DTG |

DRV/r EFV LPV/r NVP RAL |

| 6–12 years |

ABCd + 3TCe TAFj + XTCj |

TDF + XTCi | DTG |

DRV/r EFV EVG/c RAL |

| > 12 years |

ABCd +3TCe TAFj + XTCi |

TDF + XTCi |

BICk DTG |

DRV/b EFVl RALl RPVl |

Adapted from EACS Guidelines v.11.0 [16].

Abbreviations: 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; BIC, bictegravir; /c, boosted by cobicistat; DRV, darunavir; DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; EVG, elvitegravir INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; LPV/r, ritonavir nboosted lopinavir; NVP, nevirapine; /r, boosted by ritonavir; RAL, raltegravir; RPV, rilpivirine; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; VL, viral load; XTC, emtricitabine or lamivudine; ZDV, zidovudine.

aIn view of potential long‐term toxicity, any child on ZDV should be switched to ABC or TAF (preferred) or TDF (alternative) once increase in age and/or weight makes licensed formulations available.

bLPV/r should not be administered to neonates before a postmenstrual age of 42 weeks and a postnatal age of at least 14 days, although it may be considered if there is a risk of transmitted NVP resistance and INSTI in appropriate formulations are unavailable. In these circumstances the neonate should be monitored closely for LPV/r‐related toxicity.

cIf starting a non‐DTG third agent in the neonatal period, it is acceptable to continue this option. However, when over 4 weeks and 3 kg, a switch to DTG is recommended if and when an appropriate formulation is available.

dABC should NOT be prescribed to HLA‐B*57:01‐positive individuals (where screening is available). ABC is not licensed under 3 months of age but dosing data for younger children are available from the WHO and DHHS.

eAt HIV VL >100 000 copies/mL ABC + 3TC should not be combined with EFV as third agent.

fIf using NVP as a third agent in children aged 2 weeks to 3 years, consider using a three‐NRTI backbone (ABC + ZDV + 3TC) until VL is consistently < 50 copies/mL.

gTDF is only licensed from 2 years of age.

hDTG is licensed from 4 weeks and 3 kg.

iXTC indicates circumstances when FTC or 3TC may be used interchangeably.

jTAF is only licensed in Europe for treatment of HIV in combination with FTC from 12 years of age and 35 kg in TAF/FTC and from 6 years of age and 25 kg in TAF/FTC/EVG/c.

kBIC is a preferred first‐line option in adult people living with HIV. At the time of writing it is not licensed under 18 years of age but may be considered in those aged 12–18 years following discussion at multidisciplinary team (MDT)/paediatricvirtual clinic (PVC).

lDue to predicted poor adherence in adolescence, boosted protease inhibitor (PI/b) are favoured as alternative first‐line third agent options due their high barrier to resistance.

A table of relevant antiretroviral drug formulations and a link to detailed online paediatric dosing recommendations are included, as well as contact information for an international Paediatric Virtual Clinic (details within the Guidelines) which accepts referrals for complex treatment decisions for children and adolescents worldwide [15]. General principles that should be taken into account when considering switching or simplifying ART as a child ages and gains weight and as more licensed options become available are discussed. Paediatric considerations in relation to coinfection are highlighted with the inclusion of recommendations on ART regimen selection in the context of infectious hepatitis or TB at different ages.

CONCLUSIONS

The EACS Guidelines underwent major revisions in 2021 of all sections and were expanded with recommendations on COVID‐19 and ART in children and adolescents. The Guidelines are available as a free app, interactive web version and online pdf.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Declarations of interest of all panel members are available upon request. Please contact info@eacsociety.org. LR, CBe, DP, SC, HW and AB report no conflicts of interest. RDM reports personal fees (speaker fee) and non‐financial support from ViiV and Gilead. JRA reports advisory fees and speaker fees for ViiV, Janssen, Gilead, MSD, Alexa, Theranos and grant support from ViiV. JMM has taken part in advisory boards for Gilead, ViiV and Merck, and received research grant from Gilead. AGC has previously received a research grant to her institution from Gilead Sciences Ltd and previous honoraria from Gilead Sciences, MSD and Janssen Cilag. AW has received research grants, speaker honoraria or advisory fees from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen and MSD. PGMM has received honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen and Merck Sharpe and Dohme. JAR reports support to his institution for advisory boards and/or travel grants from MSD, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer and Abbvie, and an investigator‐initiated trial grant from Gilead Sciences. All remuneration went to his home institution and not to AR personally. CB has received honoraria for consulting or educational lectures from Abbvie, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, MSD and ViiV, and research grants from Dt. Leberstiftung, DZIF, Hector Stiftung and NEAT ID. OK reports personal fees and non‐financial support from Gilead, and personal fees from ViiV, Merck and Janssen. PC reports speaker's bureau from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare and consultancy work for Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, Cellevolve, Excision and Exevir, and research support from Gilead Sciences. SW has been part of an advisory board for ViiV with no personal remuneration and have organised training programmes for Penta with financial support from Gilead, ViiV and Janssen, again with no personal financial remuneration. CM has received research funding from Gilead and honoraria for lectures from ViiV and MSD. GG received research supports, honoraria and consultation fees from ViiV, Gilead, Merck and Jansen. JK has been a board member/advisory panel/grant recipient for Gilead Sciences, Glaxo SmithKline, ViiV, Janssen‐Cilag, MSD and Roche. GMNB reports support for advisory boards and/or lectures from MSD, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare or Janssen. His institution received support for interventional trials in HIV therapy from MSD and ViiV Healthcare. All remunerations were provided outside the submitted work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

LR, RDM, AGC, DP, CBe, CM and HW prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Ryom L, De Miguel R, Cotter AG, et al; the EACS Governing Board . Major revision version 11.0 of the European AIDS Clinical Society Guidelines 2021. HIV Med. 2022;23:849–858. doi: 10.1111/hiv.13268

Members of the EACS Guidelines Panels and Governing Board are listed in the Acknowledgements in Appendix 1

REFERENCES

- 1. Ryom L, Cotter A, De Miguel R, et al. 2019 update of the European AIDS clinical society guidelines for treatment of people living with HIV version 10.0. HIV Med. 2020;21(10):617‐624. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Overton ET, Richmond G, Rizzardini G, et al. Long‐acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine dosed every 2 months in adults with HIV‐1 infection (ATLAS‐2M), 48‐week results: a randomised, multicentre, open‐label, phase 3b, non‐inferiority study. Lancet. 2021;396(10267):1994‐2005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32666-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lockman S, Brummel SS, Ziemba L, et al. Efficacy and safety of dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide fumarate or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate HIV antiretroviral therapy regimens started in pregnancy IMPAACT 2. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1276‐1292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00314-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization‐WHO . Hiv prevention, infant diagnosis, antiretroviral initiation and monitoring guidelines. 2021. [PubMed]

- 5. Hodge D, Back DJ, Gibbons S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and drug‐drug interactions of intramuscular cabotegravir and rilpivirine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2021;60(7):835‐853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. 2019 update to: management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American diabetes association (ADA) and the European association for the study of diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2020;63(2):221‐228. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-019-05039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111‐188. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering AL, et al. The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European society of cardiology (ESC) and the European society of hypertension (ESH). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021‐3104. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Recently acquired and early chronic hepatitis C in MSM: recommendations from the European treatment network for HIV, hepatitis and global infectious diseases consensus panel. AIDS. 2020;34(12):1699‐1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ambrosioni J, Blanco JL, Reyes‐Urueña JM, et al. Overview of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in adults living with HIV. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(5):e294‐e305. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00070-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Atkinson A, Miro JM, Mocroft A, et al. No need for secondary Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis in adult people living with HIV from Europe on ART with suppressed viraemia and a CD4 cell count greater than 100 cells/μL. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(6):e25726. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization . WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment ‐ drug‐resistant tuberculosis treatment. World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY‐NC‐SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240007048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dorman SE, Nahid P, Kurbatova EV, et al. Four‐month rifapentine regimens with or without moxifloxacin for tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(18):1705‐1718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2033400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dolutegravir‐based ART is superior to NNRTI/PI‐based ART in children and adolescents. Oral presentation. Conference on Retroviruses and opportunistic Infections 2021. https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/dolutegravir‐based‐art‐is‐superior‐to‐nnrti‐pi‐based‐art‐in‐children‐and‐adolescents/. Accessed September 05, 2021.

- 15. https://penta‐id.org/hiv/treatment‐guidelines/. Accessed September 05, 2021.

- 16. EACS Guidelines V11.0 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material