Summary

Bacteriophage (phage) therapy is re‐emerging a century after it began.

Activity against antibiotic‐resistant pathogens and a lack of serious side effects make phage therapy an attractive treatment option in refractory bacterial infections.

Phages are highly specific for their bacterial targets, but the relationship between in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy remains to be rigorously evaluated.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles of phage therapy are generally based on the classic predator–prey relationship, but numerous other factors contribute to phage clearance and optimal dosing strategies remain unclear.

Combinations of fully characterised, exclusively lytic phages prepared under good manufacturing practice are limited in their availability.

Safety has been demonstrated but randomised controlled trials are needed to evaluate efficacy.

Keywords: Bacterial infections, Infection control

The bactericidal properties of the waters of the Ganges and the Jumna were first described at the end of the 19th century by British bacteriologist Ernest Hankin.1 Countryman and fellow microbiologist Frederick Twort's subsequent studies2 were interrupted by the First World War, but he is often credited as the discoverer of what was later termed the “Twort–d'Herelle phenomenon”.3 It was the French Canadian Felix d'Herelle who first proposed the term “bacteriophage” (phage) (ie, bacterium eater)4 and pioneered its therapeutic application using oral concentrates to treat Shigella enteritis (bacillary dysentery) in 1919, in the first recorded description of phage therapy. In the years that followed, phages were used with varying success by d'Herelle and others for a variety of serious infections, including staphylococcal bacteraemia, typhoid fever and osteomyelitis,5 and d'Herelle was awarded the Leeuwenhoek Medal in 1925 for his contributions to applied microbiology. Bacteriophages were visualised for the first time in 1939, when electron microscopy was developed, and a morphotypic classification was subsequently proposed by Helmut Ruska in 1943.6 Such classifications are not well aligned with genetic relatedness7 and a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this review, but for our purposes, the most commonly used therapeutic phages are the double‐stranded DNA viruses (often ~ 100–200 kbp) that are grouped together as “tailed viruses” (order Caudovirales) (Box 1). Phages are now understood to be the most diverse and abundant life form on Earth, probably outnumbering bacteria by ten to one.8

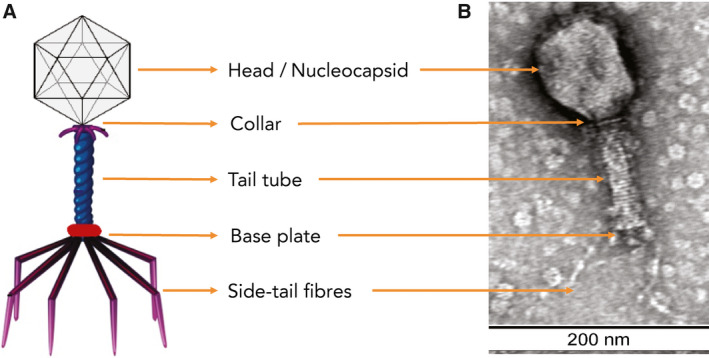

Box 1. Bacteriophage morphology.

Schematic (A) and electron micrograph of bacteriophage (Myoviridae) with 1% uranyl acetate negative staining, with size marker (B). Bacteriophage preparations were dialysed against 0.1 M ammonium acetate in dialysis cassettes with a 10 000 membrane molecular weight cut‐off (Pierce Biotechnology), negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate, and visualised using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). TEM was conducted at the Westmead Scientific Platforms (Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia) on a Philips CM120 BioTWIN (Thermo Fisher Scientific) transmission electron microscope at 100 kV. Images were recorded with a SIS Morada digital camera using iTEM software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions).

Antibiotic resistance is widely recognised as a fundamental threat to human health, development and security,9 but new antimicrobial drug development is largely unprofitable. Therefore, it is unsurprising that phage therapy is under scrutiny again. Phages have antimicrobial efficacy that correlates with their in vitro activity10 and are generally regarded as safe. The first review of intravenous phage for sepsis in 1931 described hundreds of successes,5 but enthusiasm waned as antibiotics arrived, especially in booming post‐war capitalist economies, remaining popular only in the Eastern bloc, where it was well supported.11

Clinical implementation via current drug development and clinical practice guidelines is problematic.12, 13 Much of the older literature suffered from experimental and technical problems,14 and most clinicians believe that phage therapy has “not yet been [rigorously] investigated”.15 However, after a century of use, there is increasing demand for rigorous evaluation of phage therapy, including in the most severe infections.16 There are case series with generally good outcomes, particularly in osteoarticular infections,17 diabetic foot infections,18 and chronic prostatitis.19, 20, 21 Two reviews22, 23 detail the history of phage therapy in Russia and Eastern European countries and its application in specific human infections, a 2012 article24 provides a historical review of phage therapy over the years, and comprehensive up‐to‐date reviews are now also available.25

However, randomised controlled trial (RCT) experience in humans is less impressive (Box 2). The largest reported RCT was conducted in Russia in 1963–64.23 Tens of thousands of children received either anti‐Shigella phage or placebo. The incidence of persisting clinical and culture‐confirmed Shigella dysentery was 3.8‐fold and 2.6‐fold higher, respectively, in the placebo group. In contrast, a case–control trial (n = 8) in the 1970s of high dose phage for the treatment of cholera found tetracyclines to be more effective.26 A recent RCT of a well characterised phage cocktail demonstrated safety but not efficacy for the treatment of diarrhoeal illnesses in Bangladeshi children,27, 29 but only 60% of enrolled patients had proven Escherichia coli infection, and only half of these were phage‐susceptible in vitro. More recently, a phase 1 double‐blind RCT of a topical bacteriophage cocktail in chronic venous leg ulcers found no safety concerns,30 and the much‐anticipated PhagoBurn trial (phase 1/2 RCT),10 comparing topical application of a cocktail of phages against Pseudomonas with standard care with silver sulfadiazine, found that significant reductions in bacterial counts took longer in the phage group and that the silver sulfadiazine group had higher treatment success than the phage group. The PhagoBurn trial suffered from instability of the phage preparation, but showed that phage‐susceptibility of Pseudomonas isolates in vitro is crucial to eventual clinical success, with susceptibility rates of 89% in successful cases compared with 24% in clinical failures in the phage therapy arm (Box 2).

Box 2. Randomised controlled trials on phage therapy.

| Year | Number of participants | Study design and follow‐up | Intervention and duration of therapy | Main outcome | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963–64 | 30 769 | Prospective placebo‐controlled RCT of Shigella dysentery; follow‐up 109 days24 | Phage preparation peroral once a week; therapy 109 days |

|

|

| 1970 | 8 | Case–control study of Vibrio cholerae; no follow‐up26 | High dose of phage (1013 PFU), half‐hourly to hourly, until diarrhoea resolved; therapy 5–6 days |

|

|

| 2009 | 39 | Prospective double‐blind RCT of chronic venous leg ulcers; no follow‐up27 | Phage application via ultrasonic debridement device, followed by wound dressing and bandage; therapy 12 weeks |

|

|

| 2009 | 24 | Prospective double‐blind RCT of chronic otitis externa; Pseudomonas aeruginosa; follow‐up 6 weeks28 | 105 PFU phage application plus meticulous ear cleaning; single application |

|

|

| 2016 | 120 | Prospective double‐blind RCT of acute diarrhoea in children; follow‐up 21 days29 | T4 phage cocktail or Microgen ColiProteus phage cocktail; therapy 4 days |

|

|

| 2019 | 27 | Prospective double‐blind RCT of clinically infected burn wounds (P. aeruginosa); follow‐up 14 days10 | Alginate template soaked in PP1131 at ~ 1 × 106 PFU/mL, applied topically to wounds daily; therapy 7 days |

|

|

HR = hazard ratio; NR = not reached; PFU = plaque‐forming unit; PP1131 = cocktail of 12 natural lytic anti‐P. aeruginosa bacteriophages; RCT = randomised controlled trial.

Determining bacterial susceptibility to phage infection

Phages usually exhibit a high degree of host specificity and are most easily sourced from the habitat of their usual bacterial hosts. Phages specific for clinically relevant bacteria may be readily sourced from human and animal sources, hospital wastewater, and environmental soil and water. Their reproduction is dependent on the bacterial host, either integrated into the bacterial genome as a prophage or acting in a purely parasitic manner (Box 3), the latter characteristic being exploited in phage therapy.

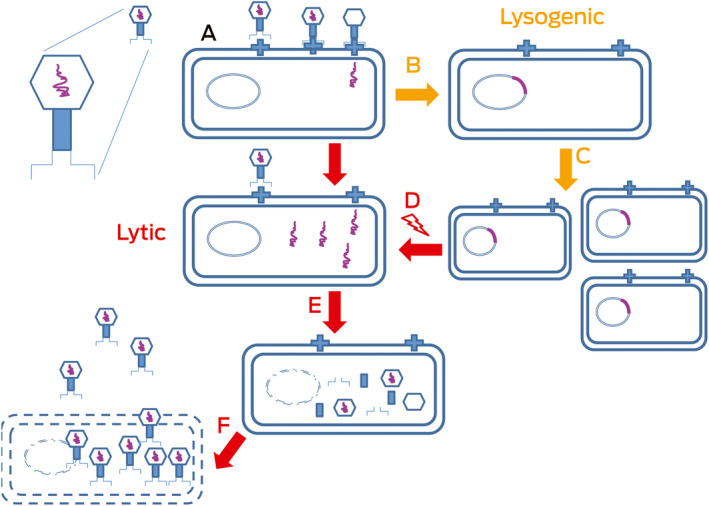

Box 3. Bacteriophage life cycles.

After infection (A), the phage DNA (purple) is classically either reproduced and packaged as new virions at the expense of the cell (a virulent phage in a lytic cycle; left, A, E and F) or reproduces with the host DNA (a temperate phage in a lysogenic cycle; right, B, C and D).

Phages bind specific receptors and adsorb onto bacterial surfaces before injecting DNA to start viral, and alter bacterial, processes (Box 3, A); their relationships range from parasitic to mutualistic.31, 32 Some integrate into bacterial chromosomes (Box 3, B) and reproduce normally (Box 3, C); lytic infection occurs (eg, when the host is stressed) (Box 3, D), then production and liberation of new virions occur (Box 3, E): lysogenised bacteria with integrated prophage (Box 3, D, red line) are protected from superinfecting phages of the same type. However, surface receptor variation, blocking of phage DNA injection, restriction or modification systems, and adaptive immunity (CRISPRs) are also protective. The ideal therapeutic phage is probably exclusively parasitic (it is virulent in the lytic cycle) and does not enter into the other common phage lifestyle, in which it integrates into and replicates with the host bacterial genome (ie, is temperate in the lysogenic cycle — a temperate phage results in a lysogenic state in the bacterial host because it may cause lysis) (Box 3, F, red arrow).

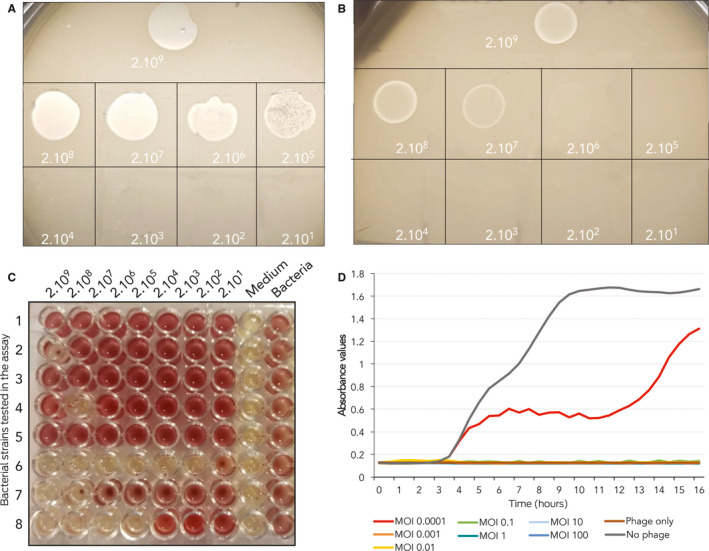

The conventional method of measuring the lytic activity of bacteriophages is by mixing target bacteria into soft agar overlaid onto a standard nutritious agar surface.33 Tenfold serial dilutions of candidate phage are then spotted onto the soft agar. The development of plaques after overnight incubation indicates productive phage infection and bacterial lysis to release progeny (Box 4, A). The productivity of a given infection (eg, as estimated in a plaque assay) is often referred to as the “burst size”, and the relationship between the inoculum required to generate productive infection in the original propagating host in vitro and the target organism (intended prey) is referred to as the “efficiency of plating”.

Box 4. Bacteriophage susceptibility testing.

Phage‐susceptibility testing of bacterial isolates with the standard double‐layer method:33 (A) susceptible isolate — productive infection and formation of individual plaques detectable at serially diluted phage lysate — and (B) resistant isolate — single plaques absent and early bacterial lysis present only at high concertation of phages. Liquid culture‐based system: (C) across a gradient of multiplicity of infections (MOIs) against eight bacteria on a single 96‐well plate. There are seven MOIs tested from highest to lowest (left to right). Column eight and nine are phage‐only and bacteria‐only controls. (D) Bacterial growth kinetics in presence of phage at differing MOIs.

The plaque assay is time‐consuming and operator‐dependent, with automated methods still in their infancy. Liquid culture‐based systems that continuously monitor bacterial growth in the presence of bacteriophage in a standard 96‐well plate format (Box 4, C) may be used to infer bacterial susceptibility to phage and also to study phage–antibiotic synergy. The relationship between various in vitro assays and in vivo outcomes is poorly validated, but most microbiologists would intuit that lack of therapeutic efficacy is predictable if the phage is inactive against the target pathogen in vitro, and there are supportive data from at least one RCT in humans.10 A failure to produce any plaques at all in a bacterial lawn is generally regarded as a negative result (resistant bacteria) in the standard double‐layer method (Box 4, B)

The development of in vitro bacterial resistance was a prominent feature of phage therapy for a high burden multidrug‐resistant Acinetobacter infection when antibiotics were failing.34 However, resistance was not observed in a small cohort of people with severe staphylococcal infection treated intravenously with a good manufacturing practice (GMP)‐quality combination of phages35 when used in conjunction with effective antibiotics.36 The antibiotic–phage synergy issue remains complex and more work needs to be done to understand the best way to use them together.

Phage dosing and kinetics: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and multiplicity of infection

A good understanding of the non‐linear kinetics of bacteriophage distribution in blood and tissues is necessary to maximise efficacy of future therapeutic protocols.37, 38 Usually applied to ecological rather than pharmacological systems, the phage replication cycle is generally held to follow classic Lotka–Volterra dynamics of predator (phage) and prey (bacteria), based on population sizes and interactions between them.39 Classic pharmacokinetic principles, predator–prey, infectious disease model dynamics, and host immune responses must all be considered, but phage pharmacokinetics (phage distribution and clearance), pharmacodynamics (predator–prey dynamics), and ratio of phages to bacteria (multiplicity of infection [MOI], perhaps better described in terms of initial MOIinput)40, 41 are subject to many, often poorly defined, variables that may influence outcomes.42

Numerous methods of bacteriophage delivery have been explored, including topical, inhalational, oral and injectable (intravenous, intramuscular, subcutaneous and direct intralesional). When administering phages orally, concern has been raised regarding recombination between modular phage genomes in the gut, although there has been little evidence from trials to date to resolve this one way or the other.43 Phages generally have poor oral bioavailability,16 but intravenous delivery is efficient to virtually all organs and tissues44 and first‐dose kinetics can be modelled to some extent by standard techniques,45 especially after initial parenteral dosing. Original observations,5 recently repeated overseas34 and in Australian studies of severe sepsis,36 show that intravenous phage is cleared typically in the first 60 minutes. However, phage clearance is also enhanced by the mammalian innate immune responses to infection46 — this may affect (or be affected by) amplification and/or phage dosage (the ratio of phages to bacteria; ie, the MOI). An MOI below 0.1 is effective in mouse models,47 but an optimal MOI to use in humans has been suggested to be ten or over.48 Bacterial concentrations are 101–105 (more usually < 103) colony‐forming units per mL of blood in severe sepsis,49 and thus a dose of 109 plaque‐forming units (PFU) into the human blood volume (~ 5 L) is expected to yield an MOIinput over 200.

The paradoxical persistence of a narrow host range for phages is not fully understood, given the presumed ecological advantages50 of host switching when starved for prey, but phages tend to disappear as their food supply is exhausted. Thus, while clearance after intravenous dosing is primarily by the reticuloendothelial system, liver and spleen, phage populations may follow more classic predator–prey kinetics when directly administered, even in areas such as the bladder.51 There are well recognised limitations to the efficacy of phages in mixed bacterial infections, and infections with low bacterial density.52, 53 Therefore, in theory, antibiotics that dramatically reduce the density of target bacteria may result in phage clearance rates that exceed propagation rates and thereby limit this unique property of phages as antimicrobials,54 adding further to the complexities of phage kinetics.

Urine concentration of bacteriophage may be dose‐dependant,55, 56 and renal clearance of bacteriophages does not appear to be of the same magnitude as clearance by the liver and spleen.46 The biofilm also presents a special case. Experimental data suggest that pre‐treatment of biofilm infections with antibiotics enhances synergistic killing by phages,57 but biofilms can be an impenetrable layer and some bacteria such as E. coli have added additional barriers (curli fibres) as a collective protection.58

Selection of phages for therapy

Optimised preparation of phage combinations (cocktails) for use in humans requires well characterised bacteriophages, a good understanding of the bacterial target population, and highly effective purification protocols to avoid inflammatory responses to contaminating residual bacterial endotoxin and protein.12, 59, 60 Toxins, resistance genes, virulence determinants, and capacity to integrate (temperate phage) are excluded by sequencing.43, 61 In vitro susceptibility testing remains specialised and should be conducted by an accepted method in a laboratory that can demonstrate reliable reproducibility of results.

General recommendations regarding the standardisation of key components of phage therapy have been published,62 and most authorities suggest that therapeutic mixtures include three to five phages at high titre (109–1010 PFU/mL) with unique but overlapping host ranges to guarantee lysis of the bacterial target and clinically relevant variants.52, 63 Each phage component should ideally target different receptors to reduce the likelihood of phage‐resistant mutants arising.37 Phage stocks should be routinely monitored for viability and concentration, and may require ad hoc modification as target bacterial populations change over time.12, 60

Phage therapy may be presented as a discrete quality‐assured formulation either as several phages admixed to provide a broad spectrum of activity in a single medicine for a specific infection (eg, common staphylococci35 or infecting pathogens in a burn wound),10 or even by engineering additional or altered breadth of spectrum into a single optimised phage.64 This concept is similar to the traditional pharmaceutical model presented to regulators such as the Food and Drug Administration in the United States.

At the other extreme, specific linking of a virulent phage to the target pathogen might be done by using a large library of stable high quality preparations that can be matched quickly and efficiently in a standardised susceptibility testing format. Chosen phages can then be prepared for co‐administration by trained staff, like any other medicine, perhaps in a compounding pharmacy such as was once common in most hospitals. This latter concept is gaining prominence in Europe as a pathway to regulation, progressing particularly in Belgium and France, as the “magistral phage” approach.65, 66

Lessons from recent Australian experience

While phages have many of the characteristics of ideal personalised medicines, lack of double‐blind phase 3 (efficacy) clinical trials in humans means that phage therapy still has the status of an old technology based on anecdotal evidence, not much different to traditional medicines. Nevertheless, there are some successful phase 1 and 2 studies, including in Australia, which suggest the potential of phage therapy as an alternative or adjunct to antibiotics.16, 24

Recent studies in Australian centres of both intranasal instillation67 and intravenous injection68 of a high purity preparation of antistaphylococcal phages36 have demonstrated safety and tolerability, but these preparations are not yet generally available. In the largest single uncontrolled, interventional clinical cohort study at Westmead Hospital (Australia), 14 patients with severe S. aureus sepsis and infective endocarditis were treated twice daily for 2 weeks with intravenous AB‐SA01 (Armata Pharmaceuticals) — a GMP‐quality cocktail product with three bacteriophages — as adjunct to standard care.68, 69 While this study is uncontrolled, phage therapy was associated with (or at least did not prevent) reduction in bacterial burden and inflammatory response and was well tolerated with no attributed adverse reactions.36

Natural bacteriophages are defined as investigational drugs by the Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia. The regulatory side of bacteriophage therapy is beyond the scope of this review, but most medical communities are both sceptical and curious.

Conclusion

To progress, we need at least to guarantee the availability of efficient phage susceptibility testing and of preparations that are safe for intravenous administration, define optimal dosing, and effectively monitor phage–bacteria–human host interactions and any important collateral effects on other members of the microflora.

Realistically, application of therapeutic phages alone may never completely replace chemical antimicrobials as the standard of care. For now, it is reasonable to define phage therapy as a promising rescue therapy that has been associated with some spectacular results34, 64, 70 and is considered an increasingly essential tool with which to manage rising antimicrobial resistance, whether as multiphage cocktail preparations or as individual phages matched to specific pathogens. It is clear, however, that RCTs are needed to define phage efficacy and to deal with the issues we outline in this review before phages find their way into the general pharmacopoeia.

Competing interests

No relevant disclosures.

Provenance

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants (1104232 and 1107322) from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. AmpliPhi Biosciences Corporation partially contributed to the funding of a bacteriophage therapy investigator‐led clinical trial at Westmead Hospital and Westmead Institute for Medical Research.

Podcast with Aleksandra Petrovic Fabijan and Ruby Lin available at https://www.mja.com.au/podcasts

References

- 1. Hankin EH. L'action bactéricide des eaux de la Jumna et du Gange sur le vibrion du choléra. Ann Inst Pasteur (Paris) 1896; 10: 511–523. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Twort FW. An investigation on the nature of ultra‐microscopic viruses. Lancet 1915; 186: 1241–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keen EC. Phage therapy: concept to cure. Front Microbiol 2012; 3: 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. d'Herelle F. Sur un microbe invisible antagoniste des bacilles dysentériques. Comptes Rendus Acad Sci Paris 1917; 165: 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- 5. d'Herelle F. Bacteriophage as a treatment in acute medical and surgical infections. Bull N Y Acad Med 1931; 7: 329–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ruska H. Ergebnisse der Bakteriophagenforschung und ihre Deutung nach morphologischen Befunden. Ergeb Hyg Bakteriol Immunforsch Exp Ther 1943; 25: 437–498. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simmonds P, Aiewsakun P. Virus classification — where do you draw the line? Arch Virol 2018; 163: 2037–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clokie MR, Millard AD, Letarov AV, Heaphy S. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage 2011; 1: 31–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aslam B, Wang W, Arshad MI, et al. Antibiotic resistance: a rundown of a global crisis. Infect Drug Resist 2018; 11: 1645–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jault P, Leclerc T, Jennes S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a cocktail of bacteriophages to treat burn wounds infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PhagoBurn): a randomised, controlled, double‐blind phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19: 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin DM, Koskella B, Lin HC. Phage therapy: an alternative to antibiotics in the age of multi‐drug resistance. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2017; 8: 162–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan BK, Abedon ST, Loc‐Carrillo C. Phage cocktails and the future of phage therapy. Future Microbiol 2013; 8: 769–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Debarbieux L, Pirnay JP, Verbeken G, et al. A bacteriophage journey at the European Medicines Agency. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2016; 363: fnv225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Furfaro LL, Payne MS, Chang BJ. Bacteriophage therapy: clinical trials and regulatory hurdles. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018; 8: 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pelfrene E, Willebrand E, Cavaleiro Sanches A, et al. Bacteriophage therapy: a regulatory perspective. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71: 2071–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gorski A, Jonczyk‐Matysiak E, Lusiak‐Szelachowska M, et al. The potential of phage therapy in sepsis. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patey O, McCallin S, Mazure H, et al. Clinical indications and compassionate use of phage therapy: personal experience and literature review with a focus on osteoarticular infections. Viruses 2018; 11: E18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fish R, Kutter E, Wheat G, et al. Bacteriophage treatment of intransigent diabetic toe ulcers: a case series. J Wound Care 2016; 25: S27–S33.26949862 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Letkiewicz S, Międzybrodzki R, Fortuna W, et al. Eradication of Enterococcus faecalis by phage therapy in chronic bacterial prostatitis — case report. Folia Microbiol 2009; 54: 457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Letkiewicz S, Międzybrodzki R, Kłak M, et al. Pathogen eradication by phage therapy in patients with chronic bacterial prostatitis. Eur Urol Suppl 2010; 9: 140. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Letkiewicz S, Międzybrodzki R, Kłak M, et al. The perspectives of the application of phage therapy in chronic bacterial prostatitis. Fems Immunol Med Mic 2010; 60: 99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abedon ST, Kuhl SJ, Blasdel BG, Kutter EM. Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage 2011; 1: 66–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris JG. Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001; 45: 649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chanishvili N. Phage therapy — history from Twort and d'Herelle through Soviet experience to current approaches. Adv Virus Res 2012; 83: 3–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gordillo‐Altamarino FL, Barr JJ. Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019; 32: e00066–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monsur KA, Rahman MA, Huq F, et al. Effect of massive doses of bacteriophage on excretion of vibrios, duration of diarrhoea and output of stools in acute cases of cholera. Bull World Health Organ 1970; 42: 723–732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sarker SA, McCallin S, Barretto C, et al. Oral T4‐like phage cocktail application to healthy adult volunteers from Bangladesh. Virology 2012; 434: 222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wright A, Hawkins CH, Anggard EE, Harper DR. A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to antibiotic‐resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa; a preliminary report of efficacy. Clinical Otolaryngology 2009; 34: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sarker SA, Sultana S, Reuteler G, et al. Oral phage therapy of acute bacterial diarrhea with two coliphage preparations: a randomized trial in children from Bangladesh. EBioMedicine 2016; 4: 124–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rhoads DD, Wolcott RD, Kuskowski MA, et al. Bacteriophage therapy of venous leg ulcers in humans: results of a phase I safety trial. J Wound Care 2009; 18: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sime‐Ngando T. Environmental bacteriophages: viruses of microbes in aquatic ecosystems. Front Microbiol 2014; 5: 355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weinbauer MG. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2004; 28: 127–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Petrovic A, Kostanjsek R, Rakhely G, Knezevic P. The first Siphoviridae family bacteriophages infecting Bordetella bronchiseptica isolated from environment. Microb Ecol 2017; 73: 368–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schooley RT, Biswas B, Gill JJ, et al. Development and use of personalized bacteriophage‐based therapeutic cocktails to treat a patient with a disseminated resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00954–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lehman SM, Mearns G, Rankin D, et al. Design and preclinical development of a phage product for the treatment of antibiotic‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Viruses 2019; 11: E88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Iredell JR, Aslam S, Gilbey T, et al. Safety and efficacy of bacteriophage therapy. ID Week 2018, Infectious Diseases Society of America; San Francisco (USA): Oct 3–7; 2018. https://idsa.confex.com/idsa/2018/webprogram/Paper72613.html (viewed Sept 2019).

- 37. Levin BR, Bull JJ. Population and evolutionary dynamics of phage therapy. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004; 2: 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abedon ST. Phage therapy: eco‐physiological pharmacology. Scientifica (Cairo) 2014; 2014: 581639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maslov S, Sneppen K. Population cycles and species diversity in dynamic Kill‐the‐Winner model of microbial ecosystem. Scientific Reports 2017; 7: 39642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abedon ST. Kinetics of phage‐mediated biocontrol of bacteria. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2009; 6: 807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abedon ST, Thomas‐Abedon C. Phage therapy pharmacology. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2010; 11: 28–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tsonos J, Vandenheuvel D, Briers Y, et al. Hurdles in bacteriophage therapy: deconstructing the parameters. Vet Microbiol 2014; 171: 460–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brüssow H. Phage therapy: the Escherichia coli experience. Microbiology 2005; 151: 2133–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dąbrowska K. Phage therapy: what factors shape phage pharmacokinetics and bioavailability? Systematic and critical review. Med Res Rev 2019; 39: 2000–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsonos J, Vandenheuvel D, Briers Y, et al. Hurdles in bacteriophage therapy: deconstructing the parameters. Vet Microbiol 2014; 171: 460–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hodyra‐Stefaniak K, Miernikiewicz P, Drapała J, et al. Mammalian host‐versus‐phage immune response determines phage fate in vivo. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 14802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chan BK, Sistrom M, Wertz JE, et al. Phage selection restores antibiotic sensitivity in MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Sci Rep 2016; 6: 26717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jung LS, Ding T, Ahn J. Evaluation of lytic bacteriophages for control of multidrug‐resistant Salmonella Typhimurium . Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2017; 16: 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ginn AN, Hazelton B, Shoma S, et al. Quantitative multiplexed‐tandem PCR for direct detection of bacteraemia in critically ill patients. Pathology 2017; 49: 304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sieber M, Gudelj I. Do‐or‐die life cycles and diverse post‐infection resistance mechanisms limit the evolution of parasite host ranges. Ecol Lett 2014; 17: 491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Khawaldeh A, Morales S, Dillon B, et al. Bacteriophage therapy for refractory Pseudomonas aeruginosa urinary tract infection. J Med Microbiol 2011; 60: 1697–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chan BK, Abedon ST. Chapter 1. Phage therapy pharmacology: phage cocktails. In: Laskin AI, Sariaslani S, Gadd GM, editors. Advances in applied microbiology; volume 78. Salt Lake City, UT: Academic Press, 2012; pp 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nilsson AS. Phage therapy — constraints and possibilities. Ups J Med Sci 2014; 119: 192–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Payne RJH, Jansen VAA. Pharmacokinetic principles of bacteriophage therapy. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003; 42: 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schultz I, Neva FA. Relationship between blood clearance and viruria after intravenous injection of mice and rats with bacteriophage and polioviruses. J Immunol 1965; 94: 833–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nishikawa H, Yasuda M, Uchiyama J, et al. T‐even‐related bacteriophages as candidates for treatment of Escherichia coli urinary tract infections. Arch Virol 2008; 153: 507–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ryan EM, Alkawareek MY, Donnelly RF, Gilmore BF. Synergistic phage‐antibiotic combinations for the control of Escherichia coli biofilms in vitro. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012; 65: 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vidakovic L, Singh PK, Hartmann R, et al. Dynamic biofilm architecture confers individual and collective mechanisms of viral protection. Nat Microbiol 2018; 3: 26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Górski A, Międzybrodzki R, Weber‐Dąbrowska B, et al. Phage therapy: combating infections with potential for evolving from merely a treatment for complications to targeting diseases. Front Microbiol 2016; 7: 1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Merabishvili M, Pirnay JP, Verbeken G, et al. Quality‐controlled small‐scale production of a well‐defined bacteriophage cocktail for use in human clinical trials. PloS One 2009; 4: e4944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McCallin S, Alam Sarker S, Barretto C, et al. Safety analysis of a Russian phage cocktail: from metagenomic analysis to oral application in healthy human subjects. Virology 2013; 443: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fauconnier A. Guidelines for bacteriophage product certification. Methods Mol Biol 2018; 1693: 253–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Carlson K. Appendix: working with bacteriophages: common techniques and methodological approaches. In: Kutter E, Sulakvelidze A, editors. Bacteriophages: biology and applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dedrick RM, Guerrero‐Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug‐resistant Mycobacterium abscessus . Nat Med 2019; 25: 730–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fauconnier A. Phage therapy regulation: from night to dawn. Viruses 2019; 11: 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pirnay JP, Verbeken G, Ceyssens PJ, et al. The magistral phage. Viruses 2018; 10: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ooi ML, Drilling AJ, Morales S, et al. Safety and tolerability of bacteriophage therapy for chronic rhinosinusitis due to Staphylococcus aureus . JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019. 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1191. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gilbey T, Ho J, Cooley L, et al. Adjunctive bacteriophage therapy for prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus . Med J Aust 2019; 211: 142–143. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2019/211/3/adjunctive-bacteriophage-therapy-prosthetic-valve-endocarditis-due [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Petrovic Fabijan A, Lin RCY, Ho J, et al. Safety and tolerability of bacteriophage therapy in severe Staphylococcus aureus infection [preprint]. bioRxiv 619999. 10.1101/619999 (viewed Sept 2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Law N, Logan C, Yung G, et al. Successful adjunctive use of bacteriophage therapy for treatment of multidrug‐resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a cystic fibrosis patient. Infection 2019; 47: 665–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]