Abstract

Rhamnose is an essential component of the insect control agent spinosad. However, the genes coding for the four enzymes involved in rhamnose biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora spinosa are located in three different regions of the genome, all unlinked to the cluster of other genes that are required for spinosyn biosynthesis. Disruption of any of the rhamnose genes resulted in mutants with highly fragmented mycelia that could survive only in media supplemented with an osmotic stabilizer. It appears that this single set of genes provides rhamnose for cell wall synthesis as well as for secondary metabolite production. Duplicating the first two genes of the pathway caused a significant improvement in the yield of spinosyn fermentation products.

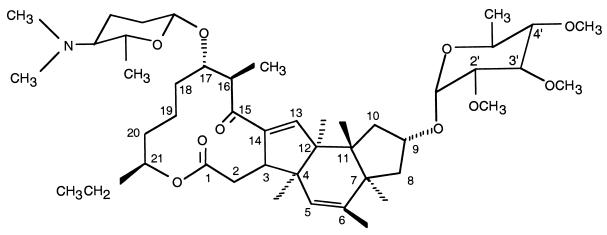

Spinosyns, the active ingredients in Dow AgroSciences' new Naturalyte line of insect control products, are produced by fermentation of the actinomycete Saccharopolyspora spinosa. Spinosyns are macrolides (Fig. 1) consisting of a 21-carbon tetracyclic lactone to which are attached two deoxysugars: tri-O-methylated rhamnose and forosamine (6). The most active components of the spinosyn family of compounds are spinosyns A and D, which differ from each other by a single methyl substituent at position 6 of the polyketide. Other factors in this family have different levels of methylation and are significantly less active. Both the rhamnose and forosamine moieties are essential for the insecticidal activity of spinosyns (2). Spinosad is highly effective against target insects and has an excellent environmental and mammalian toxicological profile (2, 13, 14).

FIG. 1.

Structure of spinosyn A.

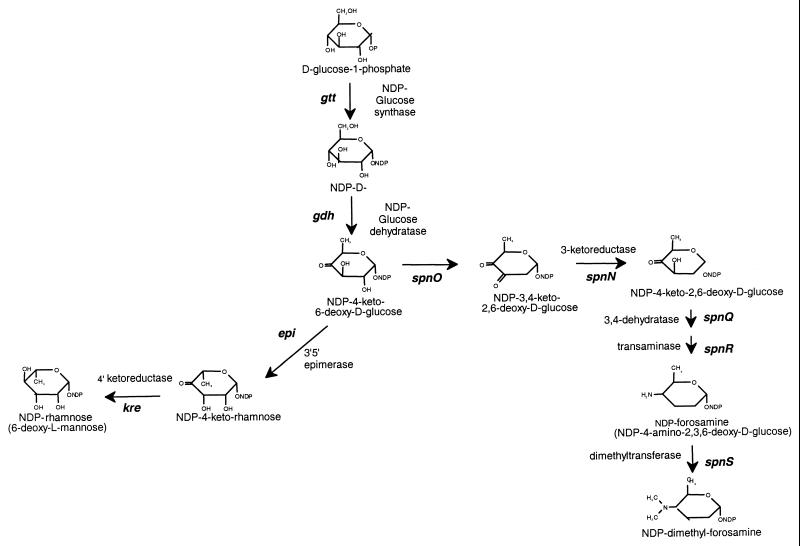

Spinosyn biosynthesis occurs via the nonglycosylated intermediate, the aglycone (AGL). Rhamnose is the first sugar attached and is tri-O-methylated to yield the intermediate pseudoaglycone. Only after the rhamnose is attached can the forosamine sugar be incorporated (M. C. Broughton, M. L. B. Huber, L. C. Creemer, H. A. Kirst, and J. R. Turner, Abstr. 91st Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1991, abstr. K-58, p. 224, 1991). Both trimethyl rhamnose and forosamine are believed to be synthesized from glucose-1-phosphate via the common intermediate 4-keto-6-deoxy-d-glucose (Fig. 2). The biosynthetic pathway for rhamnose (Fig. 2) has been elucidated in enteric bacteria, where the deoxysugar is an element of surface antigens (8, 18). The first step, activation of glucose by addition of a nucleotidyl diphosphate (NDP), is catalyzed by an NDP-glucose synthase (the gtt gene product). The second step, dehydration to NDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose, is catalyzed by glucose dehydratase (the gdh gene product). 4-Keto-6-deoxy-d-glucose is the common intermediate to many deoxysugar biosynthetic pathways, and the enzymes encoded by the gtt and gdh genes may supply the precursors for all of them. Rhamnose synthesis requires two additional enzymes, a 3′5′ epimerase (encoded by epi) and a 4′ ketoreductase (encoded by kre), that are unique to the pathway. They convert the NDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose to NDP-l-rhamnose, the activated sugar that is the substrate of the transferase which adds rhamnose to the AGL.

FIG. 2.

A hypothetical pathway for deoxysugar biosynthesis in S. spinosa. The first two steps are common to both sugar biosynthesis pathways. NDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose serves as a branch point intermediate. The pathway on the right is involved in forosamine biosynthesis, and the pathway on the left is involved in rhamnose biosynthesis. Gene designations are set in bold italics.

This report describes the cloning of four genes that have the DNA sequences expected of the rhamnose biosynthetic genes. The effects of duplicating and disrupting these genes are reported, and their involvement in cell wall biosynthesis is demonstrated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions.

Escherichia coli cells were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). When required, ampicillin was added to 100 μg/ml, and kanamycin was added to 50 μg/ml. S. spinosa strains were grown routinely at 29°C in CSM broth (10). S. spinosa transconjugants were selected on R6 medium (10) and then maintained on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar (Difco) when possible. Osmotically sensitive strains were grown on R6 agar and in CSM broth supplemented with sucrose at 200 g/liter. Apramycin (obtained from K. Merkel, Eli Lilly & Co.) was used as a selection agent at 100 μg/ml for E. coli and at 50 μg/ml for S. spinosa. The starting strains and plasmids are described in Table 1, as are the plasmids generated in this study.

TABLE 1.

Parental strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli XLOLR | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 recA1 deoR thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 lac[F′ proAB ΔlacIqZ M15 Tn10 (Tetr)]c Su− λr | Stratagene |

| E. coli DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 deoR thi-1 supE44 λ−gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.) |

| E. coli S17-1 | RP4 derivative integrated in chromosome | 12 |

| S. spinosaA83543.300 | Wild-type derivative with increased yield | NRRL18538 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pESC1 | Saccharopolyspora erythraea gtt and gdh genes | C. R. Hutchinson (University of Wisconsin Madison) |

| pBK-CMV | KanrrepColE1; present in λ ZAPII phage | Stratagene |

| pBluescript (SK−) | AmprrepColE1 | Stratagene |

| pCRII | Ampr KanrrepColE1; linearized with T overhangs | Invitrogen (San Diego, Calif.) |

| pOJ260 | AprarrepColE1oriT | 1 |

| pDAB1620 | Fragment including gdh + kre in pBK-CMV | This study |

| pDAB1621 | Fragment including gtt in pBK-CMV | This study |

| pDAB1622 | Fragment including epi in pBK-CMV | This study |

| pDAB1632 | Fragment including gtt in pOJ260 | This study |

| pDAB1633 | Fragment including epi in pOJ260 | This study |

| pDAB1634 | Fragment including gdh + kre in pOJ260 | This study |

| pDAB1635 | Internal fragment of gtt in pOJ260 | This study |

| pDAB1636 | Internal fragment of gdh in pOJ260 | This study |

| pDAB1637 | Internal fragment of epi in pOJ260 | This study |

| pDAB1639 | Internal fragment of kre in pOJ260 | This study |

| pDAB1654 | Inserts from pDAB1620 and pDAB1621 combined into a single pOJ260 plasmid | This study |

| pDAB1655 | Inserts from pDAB1620 and pDAB1621 combined into a single pOJ260 plasmid | This study |

DNA isolation and manipulation.

Standard methods for DNA isolation and manipulation were used (5, 9). A genomic library of S. spinosa was constructed from DNA partially digested with SauIIIA1. Fragments of 7 to 12 kb were purified from SeaKem GTG agarose (FMC, Rockland, Maine) gels using Qiaex II resin (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). The purified DNA was cloned into the lambda vector ZAP Express (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). 32P-labeled probes were prepared by random primer extension (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). Plaque hybridizations were performed with a stringent wash of 0.5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 65°C for 1 h. Southern hybridizations of genomic DNA included stringent washes in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C for 1 h (with gtt or gdh probes) or 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C for 1 h (with epi probes). PCRs were performed in a GeneAmp 9600 Thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) using 30 or 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 45 s at 72°C.

DNA sequencing, analysis, and synthesis.

Plasmids were sequenced using ABI Prism Ready Reaction Cycle Sequencing kits and were analyzed on an ABI 373 Automated DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, Calif.). Both strands of DNA were sequenced at least once. DNA sequences were analyzed using the Genetics Computer Group (Madison, Wis.) suite of programs (3). Similarities with known DNA and protein sequences were determined using the BLAST program of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (Washington, D.C.). Primers for DNA sequencing and PCR amplifications were synthesized on a model 394 DNA/RNA Synthesizer (Applied Biosystems Inc.).

Conjugation and metabolite analysis.

Plasmids were conjugated from E. coli S17–1 into S. spinosa 300 according to a previously published protocol (10). Transconjugants were grown in 10 ml of CSM broth (with sucrose at 200 g/liter if necessary) in 125-ml Erlenmeyer flasks for 3 days at 29°C and 300 rpm. From this seed culture, 0.3 ml was inoculated into 25 ml of INF112 fermentation medium (similar to that described in reference 15) in 250-ml baffled flasks and was grown for another 10 days at 29°C and 300 rpm. Cultures were extracted with 3 volumes of acetonitrile, followed by centrifugation at 3,500 rpm (IEC clinical centrifuge; Damon/IEC Division, Needham Heights, Mass.) for 10 min. The liquid phase was passed through a 0.20-μm-pore-size filter and analyzed by isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography in a Beckman Gold system (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, Calif.) using a C18 reverse-phase column (Waters Radial-Pak Cartridge, type 8NVC184m) with a Waters RCM 8 by 10 Module (Millipore Corp., Milford, Mass.). The column was developed at a flow rate of 2 ml/min for 30 min with acetonitrile–methanol–2% ammonium acetate (42.5:42.5:15), and metabolites were monitored at a wavelength of 250 nm.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences reported here have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF355466 (for the epi gene), AF355467 (for the gtt gene), and AF355468 (for the gdh and kre genes).

RESULTS

Cloning of the gtt, gdh, and kre genes.

The first two steps in rhamnose and forosamine biosynthesis are catalyzed by an NDP-glucose synthase and an NDP-glucose dehydratase and are likely to be shared by both pathways. Rhamnose synthesis requires two additional enzymes, an epimerase and a ketoreductase. Even though we did not find any rhamnose genes within the spinosyn gene cluster (19), we did find genes that likely code for rhamnose methylation and transfer as well as the remaining forosamine genes. Therefore, to locate the rhamnose genes and to identify their function in S. spinosa cellular metabolism, we probed regions outside the spinosyn gene cluster for the presence of rhamnose genes.

An EcoRI-BamHI fragment of pESC1 (kindly provided by C. R. Hutchinson, University of Wisconsin—Madison), containing the Saccharopolyspora erythraea gtt and gdh genes involved in erythromycin biosynthesis, was used as a heterologous probe for the S. spinosa genes. When hybridized to genomic DNA from S. spinosa, this probe bound to 7.5- and 1.5-kb EcoRI fragments and to 4-, 2.8-, and 1.2-kb BamHI fragments (data not shown). When the gdh gene alone was used as a probe, it hybridized strongly only to the 1.5-kb EcoRI fragment and the 1.2-kb BamHI fragment. This suggests that S. spinosa contains a single homologue of each of the gtt and gdh genes. Neither of the genes is linked to the major cluster of spinosyn biosynthetic genes (19), because the gtt-plus-gdh probe failed to hybridize to any of the cosmids that span the cluster (data not shown).

A genomic library of S. spinosa DNA in the lambda ZAP Express vector was screened with the S. erythraea gtt-plus-gdh probe. Three hybridizing clones were purified, and plasmids containing the inserts were excised from them (Table 1). Analysis of two of the plasmids with a variety of restriction enzymes suggested that their inserts did not overlap, implying that the gtt and gdh genes in S. spinosa are not linked. A 4-kb BamHI fragment from plasmid pDAB1621 was subcloned into pBluescript SK(−) and sequenced. It contained the 5′ end of a gtt-like gene. The remainder of the gene was sequenced by primer walking into the adjacent DNA in pDAB1621 and was found to be very similar to other nucleotidyltransferases (see Table 3). Adjacent 1.2-kb BamHI fragments from plasmid pDAB1620 were also subcloned into pBluescript SK(−) and sequenced. Together they span a gdh and a kre gene that are similar to known homologues (see Table 3). The gdh and kre genes may be translationally coupled, as the translational stop codon (TGA) of gdh overlaps the initiation codon (ATG) of the kre gene. There is a GTG codon downstream of the ATG codon in the kre gene with a good ribosomal binding site (GGACG) that could serve as a translational start site. However, we favor the ATG codon because the homology between kre genes from S. spinosa and S. erythraea extends up to the ATG codon. In addition, the arrangement of gdh and kre genes in S. erythraea is similar to that in S. spinosa.

TABLE 3.

Similarities between the translational products of putative rhamnose genes from S. spinosa and known homologues

| S. spinosa product (gene) | Total no. of amino acids | % Identity to:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharopolyspor erythraea | Salmonella enterica | ||

| Nucleotidyltransferase (gtt) | 293 | 82.6 | 56.4 |

| Dehydratase (gdh) | 329 | 81.5 | 47.7 |

| Ketoreductase (kre) | 305 | 72.0 | 39.2 |

| Epimerase (epi) | 202 | 56.5 | 35.2 |

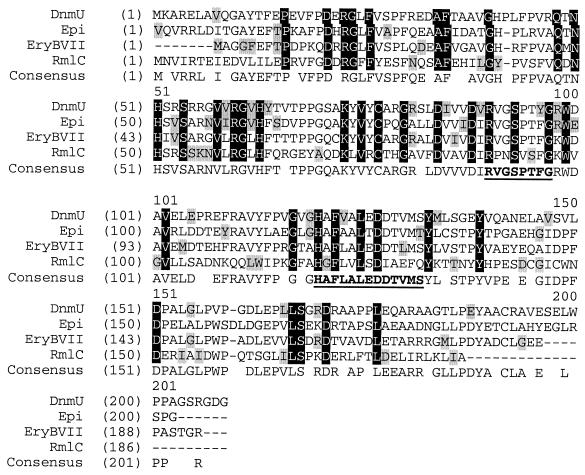

Cloning of the epi gene.

DNA sequences of genes coding for epimerases specifically involved in deoxysugar biosynthesis pathways were not available at the time of this investigation. However, the amino acid sequences of a number of these enzymes had been deposited in the public databases at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. These were compared to identify highly conserved regions (Fig. 3). Degenerate oligonucleotide primers (Table 2) corresponding to these sequences were synthesized and used in PCR experiments to amplify an internal fragment of the epi gene from S. spinosa genomic DNA. PCR amplification using these oligonucleotide primers (Table 2) gave PCR products, one of which was the expected size of 135 to 140 bp. This was cloned into the pCRII vector and sequenced. Its translation product was very similar to the known epimerase proteins. The insert hybridized to 5.2-kb EcoRI and 4.5-kb BamHI fragments of S. spinosa genomic DNA, indicating that the epi gene is not contiguous to the gtt, gdh, or kre gene. It also hybridized to one clone in the lambda ZAP Express library of S. spinosa DNA. The plasmid excised from this phage (pDAB1622) was partially sequenced by primer walking, starting with the same degenerate primers that were used to obtain the internal PCR product. The complete double-stranded sequence of the epi gene encoded a polypeptide with end-to-end similarity to epimerases from other deoxysugar biosynthesis pathways (Table 3).

FIG. 3.

CLUSTAL W (17) analysis of four epimerases involved in deoxysugar biosynthesis. Blocks of similar regions are shaded, and identical amino acids are shown as white letters on a solid background. The conserved regions for which primers were designed are underlined and boldfaced. DnmU, daunorubicin biosynthesis pathway epimerase; Epi, rhamnose biosynthesis pathway epimerase from S. spinosa; EryBVII, erythromycin biosynthesis pathway epimerase; RmlC, rhamnose biosynthesis pathway epimerase.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Target gene | Primer sequence | Location | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| epi | 5′-IG(C/G) GT(C/G) GG(C/G) I(C/G)(C/G) CC(C/G) ACC TTC GG-3′ | 5′ end | Amplification of internal fragment of ept gene |

| epi | 5′-IG(C/G) GT(C/G) GG(C/G) I(C/G)(C/G) CC(C/G) ACG TTC GG-3′ | 5′ end | Amplification of internal fragment of epi gene |

| epi | 5′-IG(C/G) GT(C/G) GG(C/G) I(C/G)(C/G) CC(C/G) ACC TAC GG-3′ | 5′ end | Amplification of internal fragment of epi gene |

| epi | 5′-IG(C/G) GT(C/G) GG(C/G) I(C/G)(C/G) CC(C/G) ACG TAC GG-3′ | 5′ end | Amplification of internal fragment of epi gene |

| epi | 5′-CAT (C/G)AI GTC GTC (C/T)TC (C/G)AI (C/G)GC (C/G)AC GAA CGC GTG-3′ | 3′ end | Amplification of internal fragment of epi gene |

| epi | 5′-CAT (C/G)AI GTC GTC (C/T)TC (C/G)AI (C/G)GC (C/G)AC GAA GGC GTG-3′ | 3′ end | Amplification of internal fragment of epi gene |

| gtt | 5′-CCCGAATTCCTCCAGGCAGGCGATCCGCA-3′ | 5′ end | Gene disruption |

| gtt | 5′-GGGAAGCTTAGTTCGGCATTCGGATCGAG-3′ | 3′ end | Gene disruption |

| gdh | 5′-CCCGAATTCGTGGTCCACCGAGTAGCGGC-3′ | 5′ end | Gene disruption |

| gdh | 5′-GGGAAGCTTCGTGATCACCAACGTGGTCG-3′ | 3′ end | Gene disruption |

| epi | 5′-CCCGAATTCCGGTCCTTTTCGGACAGGAC-3′ | 5′ end | Gene disruption |

| epi | 5′-GGGAAGCTTGACGCCACGGGGCACCCG-3′ | 3′ end | Gene disruption |

Disruption of rhamnose genes.

Disrupting the rhamnose biosynthesis genes should prevent S. spinosa from making rhamnose for spinosyn production and should cause accumulation of the AGL. However, the phenotype may be more complex if rhamnose (or some other deoxysugar derived from the same pathway) has another role in cellular metabolism. This is the case in S. erythraea, where disruption of the gdh gene appears to be lethal (7).

Internal fragments of the gtt, gdh, and epi genes were obtained by PCR-mediated amplification using oligodeoxynucleotide primers (Table 2). An internal fragment of the kre gene was obtained by EcoRI-SstI digestion. The fragments were cloned into plasmid pOJ260 and conjugated into S. spinosa (Table 1). Transconjugants were obtained in all cases on the usual selective medium based on R6 agar, but they failed to grow when subsequently patched onto BHI plates. They were able to grow when repatched onto R6 agar and when inoculated into R6 broth. We presumed that a component of R6 medium is critical for the survival of the mutants and compared the components of the R6 medium with those of other vegetative growth media we routinely employ in the propagation of S. spinosa. Since rhamnose is a component of cell walls of other gram-positive bacteria (11), we reasoned that the sucrose component of the R6 medium might be the key ingredient allowing the mutants to grow only on R6 medium.

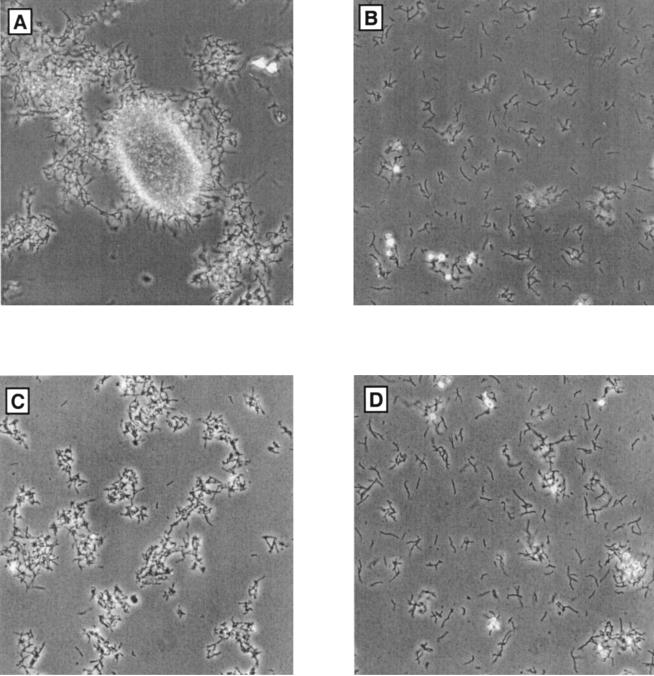

To test the hypothesis that rhamnose gene mutants are conditional for the presence of sucrose, a known osmotic stabilizer, we investigated the growth of the mutants in other vegetative media that were supplemented with sucrose (no other osmoprotectants were evaluated). They grew in CSM broth containing 200 g of sucrose/liter (as present in R6). They also grew on BHI agar supplemented with 200 g of sucrose/liter. However, the mutants never grew as well as the parent strain. Their mycelia were highly fragmented compared to that of the wild type (Fig. 4) and did not survive storage at −70°C. The mutants could not be fermented according to the standard protocol. Therefore, the effect of gene disruption on spinosyn production could not be ascertained.

FIG. 4.

Mycelial morphology in mutants with disrupted rhamnose genes. (A) Strain 300 (parental); (B) strain SS42 (disrupted gdh); (C) strain SS46 (disrupted epi); (D) strain SS44 (disrupted kre).

Rhamnose gene duplications.

Since the impact of the rhamnose pathway on spinosyn production could not be ascertained using this gene disruption strategy, we used an alternate approach to confirm the role of cloned rhamnose genes in spinosyn production. Any impact of rhamnose gene duplication on spinosyn yield would serve as indirect evidence to support the role of these rhamnose genes in spinosyn production. To test this idea, the inserts containing the gdh and kre genes (5.3 kb), the gtt gene (6.3 kb), and the epi gene (5.8 kb) were cloned separately into pOJ260 for conjugation into S. spinosa (Table 1). Two or three transconjugants from each gene duplication experiment were analyzed in a replicated fermentation experiment with 20 flasks per strain.

Some transconjugants were incapable of producing spinosyns, presumably because they had lost the biosynthetic gene cluster (as is routinely observed [10]). In those strains that did produce spinosyns, there was no yield improvement associated with duplication of these fragments. It appears that individual rhamnose enzymes were not rate limiting in spinosyn biosynthesis and that these regions did not contain any trans-acting positive regulatory genes.

Simultaneous duplication of the gtt and gdh genes.

The genes coding for the first common intermediate in deoxysugar biosynthesis leading to NDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose (Fig. 2) are shared by both deoxysugar pathways. To test whether NDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose, a branch point intermediate, is the limiting precursor for spinosyn production, the two genes gtt and gdh were duplicated.

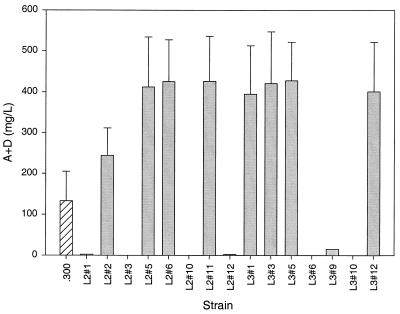

The fragment containing the gtt gene and the fragment containing the gdh and kre genes were combined in a single pOJ260 plasmid. Two independent clones carrying both fragments were selected: pDAB1654 and pDAB1655. They were transformed into E. coli S17-1 and then mated with S. spinosa strain 300 to produce apramycin-resistant transconjugants. Fifteen transconjugants were analyzed in a replicated fermentation experiment with 20 flasks per strain. The experiment was repeated twice to confirm the findings. When fermented, about half of the transconjugants produced no spinosyn, again presumably due to deletion of a large genomic region containing the biosynthetic gene cluster (10). Experimental support for this hypothesis was obtained from two representative strains whose genomic DNA failed to yield a PCR amplification product with primers specific for a gene in the spinosyn cluster, spnO (data not shown). The remaining transconjugants accumulated about threefold more spinosyn than their parent (Fig. 5). Duplication of the gtt and gdh genes in two representative strains was confirmed by PCR amplification with both genome- and vector-specific flanking primers (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Spinosyn accumulation in strain 300 transconjugants. Hatched bar, production in the control parent strain; shaded bars, production in 15 independent transconjugants evaluated in this experiment. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation above the mean.

DISCUSSION

Not surprisingly, S. spinosa contains homologues of the gtt and gdh genes of S. erythraea. The products of these genes catalyze the first two steps in the biosynthesis of many deoxysugars and are highly conserved in several species of bacteria (8, 18). Only one homologue of each was found in the genome of S. spinosa, either by Southern hybridization or by cloning, suggesting that these two genes provide a common precursor used in all deoxysugar biosynthetic pathways (including both rhamnose and forosamine for spinosyn production). An epi gene, encoding the first unique enzyme of rhamnose synthesis, was also identified by sequence conservation, but in this case by cloning the gene based on regions of amino acid similarity. Since there appears to be only one homologue in the S. spinosa genome, the product of this gene must be used to make all the rhamnose in the cell. Ketoreductases are much more divergent, and heterologous probes were unlikely to identify this gene. Fortuitously, a kre gene was found adjacent to the gdh gene by sequencing the cloned DNA fragment. Because this kre open reading frame is translationally coupled to the gdh gene, it is a preferred candidate for the ketoreductase required in rhamnose synthesis. Verification of a role in this pathway could be established only by the effects of gene disruption.

Disruption of any of the gtt, gdh, epi, and kre genes had the same striking effect on S. spinosa cells: disrupted mutants required an osmotic stabilizer for growth, and their mycelia were highly fragmented. All four genes therefore probably participate in the same pathway. Southern hybridizations identified the gtt, gdh, and epi genes as the only close homologues of known rhamnose biosynthetic genes, suggesting that their shared function is the production of this deoxysugar. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that they also contribute to the synthesis of other sugars. The rhamnose they would generate is implicated as a component of S. spinosa cell walls, important for cell integrity and morphology, as well as for spinosyn synthesis. The presence of rhamnose in S. spinosa cell wall polysaccharides was confirmed by sugar analysis (M. R. McNeil, personal communication). It is a minor component of the cell wall (1.6% by weight); the major components are arabinose and galactose (76 and 15.8%, respectively). However, rhamnose is likely to play the same critical role of linker between the arabinogalactan and peptidoglycan layers as it does in mycobacterial cell walls (11). A similar situation may apply in S. erythraea, where disruption of the gdh gene is lethal (7). Disruption of this gene in S. spinosa was achieved only because a very high concentration of sucrose was used to regenerate transconjugants. Even this did not allow the disrupted strains to be fermented for a direct evaluation of the gene's role in spinosyn biosynthesis.

There appears to be only one set of biosynthetic genes to provide the rhamnose for both primary structural components (cell walls) and a secondary metabolite (spinosyns). This dual functionality may explain why the genes are not linked to the other rhamnose-associated genes (rhamnosyltransferase and the O-methyltransferases) that are clustered with spinosyn-specific genes. This cluster is located in a region of the chromosome that is prone to deletion (10). When the genes in the spinosyn cluster are disrupted, spinosyn production is affected but growth is not impaired (19). Therefore, these cluster-associated gene products are used exclusively for spinosyn biosynthesis. Their loss can be tolerated because they are not involved in cell wall synthesis. A similar pattern of dispersion was observed for the homologous genes involved in the early steps of daunorubicin biosynthesis in Streptomyces peucetius (4) and in erythromycin biosynthesis in S. erythraea (7, 16).

Duplication of any one of the three regions containing the gtt, epi, or gdh plus kre genes had no effect on spinosyn biosynthesis, indicating that no single enzyme of rhamnose biosynthesis is limiting for the fermentation. However, when the regions containing the gtt and gdh plus kre genes were duplicated simultaneously, there was a dramatic increase in spinosyn yield (Fig. 5). Our hypothesis is that spinosad production in the parent strain is limited by the supply of NDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose, the common intermediate for both rhamnose and forosamine sugars. The two enzymes that generate this intermediate (the products of the gtt and gdh genes) are presumed to have similar levels of activity, so a significant increase in flux through the pathway is achieved only when both genes are duplicated. If this is correct, it provides indirect evidence that these genes, which are necessary for cell wall synthesis, are also involved in spinosyn production. In fact, it implies that the activities of their products are limiting for spinosyn yield in this strain. When these genes are duplicated, the extra deoxysugar molecules are incorporated into spinosyns because the cells can generate additional AGL. The ability to produce more precursor is not normally manifested because the nonglycosylated macrolactone does not accumulate, even in a mutant with a disrupted rhamnosyltransferase gene (19).

Cloning and characterization of the rhamnose-synthesizing genes of S. spinosa revealed a single set of genes that is apparently used in both primary and secondary metabolism. This observation raises the intriguing question of whether the expression of these genes is constitutive or whether it is controlled independently by two regulatory networks associated with the different physiological states.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Scott Bevan for oligonucleotide synthesis and DNA sequencing. Chris Broughton (Lilly Research Laboratories) provided the highly replicated fermentation analyses necessary to test for quantitative effects on spinosyn yield. We are grateful to Mike McNeil (Colorado State University) for analysis of S. spinosa cell walls and to Dick Hutchinson (University of Wisconsin—Madison) for plasmid pESC1 and for advice. We also appreciate the advice of Patti Matsushima and Dick Baltz (Lilly Research Laboratories).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bierman M, Logan R, O'Brien K, Seno E T, Rao R N, Schoner B E. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crouse G D, Sparks T C. Naturally derived materials as products and leads for insect control: the spinosyns. Rev Tox. 1998;2:133–146. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallo M A, Ward J, Hutchinson C R. The dnrM gene in Streptomyces peucetius contains a naturally occurring frameshift mutation that is suppressed by another locus outside of the daunorubicin-production gene cluster. Microbiology. 1996;142:269–275. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, United Kingdom: John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirst H A, Michel K H, Mynderse J S, Chio E H, Yao R C, Nakatsukasa W M, Boeck L D, Occlowitz J L, Paschal J W, Deeter J B, Thompson G D. Discovery, isolation and structure elucidation of a family of structurally unique, fermentation-derived tetracyclic macrolides. In: Baker D R, et al., editors. Synthesis and chemistry of agrochemicals. III. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society; 1992. pp. 214–225. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linton K J, Jarvis B J, Hutchinson C R. Cloning of the genes encoding thymidine diphosphoglucose 4,6-dehydratase and thymidine diphospho-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose 3,5-epimerase from the erythromycin-producing Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Gene. 1995;153:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu H W, Thorson J S. Pathways and mechanisms in the biogenesis of novel deoxysugars by bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:223–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushima P, Broughton M C, Turner J R, Baltz R H. Conjugal transfer of cosmid DNA from Escherichia coli to Saccharopolyspora spinosa: effects of chromosomal insertion on macrolide A83543 production. Gene. 1994;146:39–45. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeil M R. Arabinogalactan in mycobacteria: structure, biosynthesis, and genetics. In: Goldberg J, editor. Genetics of bacterial polysaccharides. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1999. p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon R, Preifer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparks T C, et al. Biological activity of the spinosyns, new fermentation derived insect control agents, on tobacco budworm (Lepidoptera: Nocuidae) larvae. J Econ Entomol. 1998;91:1277–1283. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparks T C, et al. Fermentation-derived insect control agents: the spinosyns. Methods Biotechnol. 1999;5:171–188. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strobel R J, Nakatsukasa W M. Response surface methods for optimizing Saccharopolyspora spinosa, a novel macrolide producer. J Ind Microbiol. 1993;11:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summers R G, Donadio S, Staver M J, Wedt-Pienkowski E, Hutchinson C R, Katz L. Sequencing and mutagenesis of genes from the erythromycin biosynthesis gene cluster of Saccharopolyspora that are involved in l-mycarose and d-desosamine production. Microbiology. 1997;143:3251–3262. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-10-3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trefzer A, Salas J, Bechthold A. Genes and enzymes involved in deoxysugar biosynthesis in bacteria. Nat Prod Rep. 1999;16:283–299. doi: 10.1039/a804431g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waldron C, Matsushima P, Rosteck P R, Jr, Broughton M C, Turner J, Madduri K, Crawford K P, Merlo D J, Baltz R H. Cloning and analysis of the spinosad biosynthetic gene cluster of Saccharopolyspora spinosa. Chem Biol. 2001;8:487–499. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]