Abstract

Introduction

People who inject drugs are at high risk of blood‐borne infections. We describe the epidemiology of HIV among people who inject drugs in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland (EW&NI) since 1981.

Methods

National HIV surveillance data were used to describe trends in diagnoses (1981–2019), prevalence (1990–2019), and behaviours (1990–2019) among people who inject drugs aged ≥15 years in EW&NI. HIV care and treatment uptake were assessed among those attending in 2019.

Results

Over the past four decades, the prevalence of HIV among people who inject drugs in EW&NI remained low (range: 0.64%–1.81%). Overall, 4978 people who inject drugs were diagnosed with HIV (3.2% of cases). Diagnoses peaked at 234 in 1987, decreasing to 78 in 2019; the majority were among white men born in the UK/Europe (90%), though the epidemic diversified over time. Late diagnosis (CD4 <350 cells/µl) was common (2010–2019: 52% [429/832]). Of those who last attended for HIV care in 2019, 97% (1503/1550) were receiving HIV treatment and 90% (1375/1520) had a suppressed viral load (<200 copies/ml).

HIV testing uptake has steadily increased among people who inject drugs (32% since 1990). However, in 2019, 18% (246/1404) of those currently injecting reported never testing. The proportion of people currently injecting reporting sharing needles/syringes decreased from 1999 to 2012, before increasing to 20% (288/1426) in 2019, with sharing of any injecting equipment at 37% (523/1429).

Conclusion

The HIV epidemic among people who inject drugs in EW&NI has remained relatively contained compared with in other countries, most likely because of the prompt implementation of an effective national harm reduction programme. However, risk behaviours and varied access to preventive interventions among people who inject drugs indicate the potential for HIV outbreaks.

Keywords: HIV infection/diagnosis, HIV infection/epidemiology, injecting drug use, patient care, United Kingdom

INTRODUCTION

In 2019–2020, an estimated 1 in 11 adults in England and Wales aged 16–59 years reported using an illicit drug in the last year, equal to approximately 3.2 million people [1]. The size of the population of people who inject drugs in England is unknown; however, the number of people aged 15–64 years injecting heroin or crack was last estimated in 2011–2012 at 87 302 (95% credible interval: 85 307–90 353) [2]. This does not include the range of other drugs that can be injected, such as amphetamines and powder cocaine.

People who inject drugs are vulnerable to a wide range of infections, including skin and soft tissue infections, bacterial sepsis, and blood‐borne viruses (BBVs), resulting in high levels of morbidity and mortality if untreated [3, 4]. BBVs, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV), are of particular concern, as exposure can lead to chronic infection with long asymptomatic periods. Public health monitoring of infectious diseases and the associated behaviours among the injecting population is essential to better understand disease burden and risk factors for acquisition and for assessing the effectiveness of prevention measures.

In the United Kingdom (UK), national surveillance for new HIV and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) diagnoses was introduced in 1981 and, over the past 40 years, has allowed for monitoring of the epidemic among people acquiring HIV through injecting drug use (IDU) as well as through other exposures. In response to concerns in the late 1980s about the potential for rapid transmission of HIV through IDU, enhanced surveillance among people who inject drugs in England and Wales was introduced in 1990 through the Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring (UAM) Survey. The UAM Survey, which expanded to Northern Ireland in 2002, allows for the monitoring of HIV prevalence and estimation of undiagnosed infection and risk and protective behaviours.

In this article, we describe trends in HIV and changes in behaviours among people who inject drugs in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland (EW&NI) over the past four decades in an effort to inform prevention efforts and care delivery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources

National surveillance data of people diagnosed with HIV across EW&NI are held at the UK Health Security Agency [5]. HIV diagnoses data have been reported by clinicians and local laboratories since 1981. Follow‐up information on people who subsequently access HIV care has been reported by NHS specialist HIV outpatient services since 1995. Data items include gender, age, ethnicity, route of HIV exposure, AIDS diagnosis, antiretroviral therapy (ART) uptake, and clinical biomarkers. Data on all‐cause mortality among people with HIV are obtained through clinician reports and by linking with the Office of National Statistics national death register.

The UAM Survey is a repeated cross‐sectional survey of people who inject drugs across EW&NI, that has been running annually since 1990 (London Research Ethics Committee: MREC/98/2/51) [3]. People who have ever injected psychoactive drugs are recruited through specialised agencies providing drug‐ and alcohol‐related services (e.g. addiction and harm reduction) and asked to complete a brief questionnaire and provide a biological sample, which is tested for HIV, HBV, and HCV. The survey questionnaire covers topics including sexual and injecting risk behaviours and experiences of homelessness, imprisonment, and service use. The survey has evolved over time in terms of the biological sample collected (dried‐blood spot since 2009/10, previously oral fluid) and the questions included, with relevant additions including age at last injection (to calculate injecting duration) in 1993; self‐reported HIV status in 1995; year of last HIV test and sharing of injecting equipment other than needles and syringes, including cottons, spoons, and filters, in 1996; and sexualised drug use (gamma hydroxybutyrate/butyrolactone, mephedrone, cocaine, methamphetamine, crack, amphetamine) in 2018.

Inclusion criteria and definitions

For HIV surveillance data, people who inject drugs were defined as those acquiring HIV through IDU. Analyses were limited to adults (aged ≥15 years) resident in EW&NI using data collected to the end of December 2019. Region of death was used where region of residence was missing (n = 14).

Late HIV diagnosis was defined as having a first CD4 count <350 cells/µl within 3 months (91 days) of diagnosis and AIDS as a presentation with an AIDS‐defining illness. Newly diagnosed people who inject drugs were considered linked to HIV care if they had evidence of either a CD4 count taken after diagnosis or HIV clinic attendance. ART coverage was used to describe the proportion of people who inject drugs on treatment regardless of CD4 count, not including those missing treatment status (0.19%). The proportion virally suppressed was the number of people who inject drugs on treatment with a viral load <200 copies/ml, not including those missing a viral load measurement (2.1%).

In the UAM Survey, participants were defined as injecting drugs if they had ever injected a psychoactive drug (i.e. both current and former IDU). Those who reported injecting in the month (28 days) prior to survey participation were considered to be currently injecting and at ongoing risk of HIV infection. Data on adults (aged ≥15 years) participating in any survey year up to the end of 2019 were included in these analyses.

Data analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed to characterise people who inject drugs. Pearson χ 2 tests were used to assess differences in proportions (statistical significance p < 0.05). Unless otherwise stated, all proportions presented are where data are known. Analyses were performed using STATA v15.1 (College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

HIV diagnoses

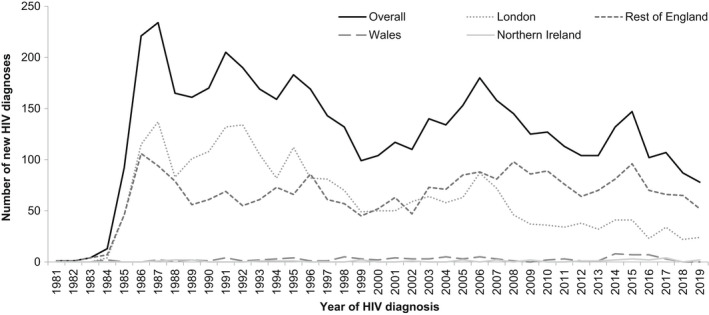

Between 1981 and 2019, there were 4978 reports of HIV diagnoses among people who inject drugs in EW&NI, equivalent to 3.2% of all adults diagnosed. Annual diagnoses declined from a high of 234 in 1987 to 78 in 2019, with small peaks in diagnoses in 1991, 1995, and 2006, driven by an increase in cases in London and—in 2015—by an increase in cases in England, outside of London (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

New HIV diagnoses among people who inject drugs by region of residence: England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1981–2019

Overall, most people who inject drugs diagnosed with HIV were men (73%; 3619), aged 25–34 years (49%; 2435), and of white ethnicity (85%; 3864). The majority were resident in London (47%; 2352) or the rest of England (50%; 2501). Where country of birth was reported (59% complete), half of all newly diagnosed people who inject drugs were born in the UK (48%; 1389), whereas 42% (1230) originated from other European countries. The majority of people who inject drugs diagnosed with HIV born outside the UK were from Portugal (21%; 319/1529), Poland (11%; 171), Latvia (10%; 159), Italy (10%; 157), and Spain (6.9%; 106).

Over the four decades, the ratio of HIV diagnoses made among men compared with women increased from 2:1 in 1981–1989 to 4:1 in 2010–2019 (p < 0.001) (Table 1; Figure S1a). Diagnoses among older age groups also increased, with 11% (123/1101) of those diagnosed in 2010–2019 aged ≥50 years, compared with <1% (4/856) of those diagnosed in 1981–1989 (p < 0.001) (Table 1; Figure S1b). Median age at HIV diagnosis increased steadily from 27 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 23–31) in 1981–1989 to 37 years (IQR: 31–44) in 2010–2019 (p < 0.001) (Table 1). People diagnosed with HIV became more ethnically diverse, with the proportion of people categorized as of “other” ethnicities increasing from 3.4% (23/674) in 1981–1989 to 12% (123/1068) in 2010–2019 (Table 1; Figure S1c). Completeness of country of birth has improved drastically over time, especially since follow‐up of missing data was introduced in the late 1990s (Table 1). The proportion of people born outside the UK increased from 20% (36/177) in 1981–1989 to 59% (618/1048) in 2010–2019 (p < 0.001) (Table 1; Figure S1d).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of HIV diagnoses among people who inject drugs: England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1981–2019

| Variables | Total | 1981–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2019 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Total | 4978 | 892 | 1619 | 1366 | 1101 | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Men | 3619 | 73% | 593 | 66% | 1133 | 70% | 1015 | 74% | 878 | 80% |

| Women | 1359 | 27% | 299 | 34% | 486 | 30% | 351 | 26% | 223 | 20% |

| Median age at diagnosis (IQR) | 32 (27–38) | 27 (23–31) | 31 (27–36) | 33 (28–39) | 37 (31–44) | |||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||||||

| 15–24 | 634 | 13% | 268 | 31% | 168 | 10% | 135 | 9.9% | 63 | 5.7% |

| 25–34 | 2435 | 49% | 483 | 56% | 961 | 60% | 611 | 45% | 380 | 35% |

| 35–49 | 1662 | 34% | 101 | 12% | 464 | 29% | 562 | 41% | 535 | 49% |

| ≥50 | 206 | 4.2% | 4 | 0.47% | 21 | 1.3% | 58 | 4.2% | 123 | 11% |

| Not reported | 41 | ‐ | 36 | ‐ | 5 | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | 0 | ‐ |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White | 3864 | 85% | 582 | 86% | 1278 | 87% | 1117 | 83% | 887 | 83% |

| Black | 354 | 7.8% | 69 | 10% | 117 | 8.0% | 110 | 8.2% | 58 | 5.4% |

| Other | 337 | 7.4% | 23 | 3.4% | 73 | 5.0% | 118 | 8.8% | 123 | 12% |

| Not reported | 423 | ‐ | 218 | ‐ | 151 | ‐ | 21 | ‐ | 33 | ‐ |

| Region of birth | ||||||||||

| UK | 1389 | 48% | 141 | 80% | 245 | 50% | 573 | 48% | 430 | 41% |

| Other Europe | 1230 | 42% | 32 | 18% | 200 | 41% | 491 | 41% | 507 | 48% |

| Elsewhere | 299 | 10% | 4 | 2.3% | 42 | 8.6% | 142 | 12% | 111 | 11% |

| Not reported | 2060 | ‐ | 715 | ‐ | 1132 | ‐ | 160 | ‐ | 53 | ‐ |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||

| London | 2352 | 47% | 486 | 54% | 955 | 59% | 586 | 43% | 325 | 30% |

| Rest of England | 2501 | 50% | 394 | 44% | 634 | 39% | 744 | 54% | 729 | 66% |

| Wales | 93 | 1.9% | 7 | 0.78% | 25 | 1.5% | 29 | 2.1% | 32 | 2.9% |

| Northern Ireland | 32 | 0.64% | 5 | 0.56% | 5 | 0.31% | 7 | 0.51% | 15 | 1.4% |

| Median CD4 at diagnosis (cells/µl) (IQR) | 320 (137–544) | a | 308 (150–540) | 314 (125–550) | 332 (141–550) | |||||

| Diagnosed late (CD4 <350 cells/µl) | 1306 | 53% | a | 340 | 56% | 531 | 53% | 429 | 52% | |

| Diagnosed very late (CD4 <200 cells/µl) | 818 | 33% | a | 204 | 33% | 339 | 34% | 273 | 33% | |

| AIDS‐defining illnesses at HIV diagnosis | 555 | 11% | 52 | 6.0% | 278 | 17% | 144 | 11% | 81 | 7.4% |

| Ever linked to HIV care after diagnosis | 3849 | 77% | 292 | 33% | 1173 | 72% | 1307 | 96% | 1083 | 98% |

| Death following HIV diagnosis | 1430 | 29% | 374 | 42% | 651 | 40% | 324 | 24% | 81 | 7.4% |

| Death within a year of HIV diagnosis | 288 | 5.8% | 41 | 4.6% | 139 | 8.6% | 77 | 5.6% | 31 | 2.8% |

Proportions may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Completeness: gender 100%, age at diagnosis 99%, ethnicity 92% (1980–1989: 76%; 1990–1999: 91%; 2000–2009: 98%; 2010–2019: 97%), region of birth 59% (1980–1989: 20%; 1990–1999: 30%; 2000–2009: 88%; 2010–2019: 95%), region of residence 100%, CD4 count at diagnosis 53% (1980–1989: 1.2%; 1990–1999: 38%; 2000–2009: 73%; 2010–2019: 76%), AIDS at diagnosis 100%.

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Data not presented because of low completeness.

Late diagnosis, AIDS, and deaths

Of people who inject drugs diagnosed with HIV, half (49%; 2447) had a CD4 count taken within 3 months of diagnosis; this improved over time to 76% (832/1101) among those diagnosed in 2010–2019 (Table 2). Over half (53%; 1306/2447) of people who inject drugs diagnosed each year were diagnosed late. Overall, the median CD4 count at diagnosis was 320 cells/µl (IQR: 137–544), which did not change significantly over time (p = 0.216). Late diagnosis was more common among men (57% [1019/1801]) than among women (44% [287/646]) and more common among older people (15–24 years: 28% [54/192]; 25–34 years: 51% [559/1091]; 35–49 years: 58% [594/1021], ≥50 years: 69% [99/143]). Late diagnosis remained high and stable across the 39 years (p = 0.366) (Figure S1e). In total, 11% (555/4978) of people who inject drugs presented with an AIDS‐defining illness at HIV diagnosis between 1981 and 2019. The proportion of those with AIDS at HIV diagnosis dropped drastically in the mid‐1990s and continued to decline to 7.4% (81/1101) in 2010–2019 (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Quality of HIV care indicators among people who inject drugs by demographic factors: England, Wales, and Northern Ireland

| Variables | Year last seen for HIV care if no death reported a | Last CD4 count (cells/µl) b , c | ART status b , d | Last viral load (copies/ml) b , e | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2010–2018 | <2010 | <200 | 200–349 | 350–499 | ≥500 | On treatment | <200 | ||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 1553 | 55% | 603 | 21% | 655 | 23% | 182 | 12% | 214 | 14% | 312 | 20% | 822 | 54% | 1503 | 97% | 1375 | 90% |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| Men | 1159 | 56% | 453 | 22% | 443 | 22% | 140 | 12% | 160 | 14% | 240 | 21% | 598 | 53% | 1121 | 97% | 1018 | 90% |

| Women | 394 | 52% | 150 | 20% | 212 | 28% | 42 | 11% | 54 | 14% | 72 | 18% | 224 | 57% | 382 | 97% | 357 | 92% |

| Age at last attendance for care (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 15–24 | 13 | 23% | 8 | 14% | 36 | 63% | 1 | 10% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 20% | 7 | 70% | 10 | 83% | 7 | 88% |

| 25–34 | 117 | 21% | 145 | 26% | 298 | 53% | 12 | 11% | 12 | 11% | 20 | 18% | 68 | 61% | 109 | 94% | 93 | 83% |

| 35–49 | 759 | 55% | 328 | 24% | 303 | 22% | 92 | 12% | 110 | 15% | 151 | 20% | 394 | 53% | 734 | 97% | 661 | 89% |

| ≥50 | 664 | 83% | 122 | 15% | 18 | 2.2% | 77 | 12% | 92 | 14% | 139 | 21% | 353 | 53% | 650 | 98% | 614 | 93% |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| White | 1273 | 56% | 488 | 21% | 515 | 23% | 151 | 12% | 175 | 14% | 268 | 21% | 667 | 53% | 1232 | 97% | 1135 | 91% |

| Black | 121 | 58% | 41 | 20% | 45 | 22% | 18 | 15% | 18 | 15% | 21 | 18% | 63 | 53% | 118 | 98% | 110 | 91% |

| Other | 145 | 58% | 58 | 23% | 47 | 19% | 13 | 9.2% | 18 | 13% | 22 | 16% | 88 | 62% | 140 | 97% | 123 | 88% |

| Region of birth | ||||||||||||||||||

| UK | 737 | 75% | 203 | 21% | 40 | 4.1% | 97 | 13% | 99 | 14% | 156 | 21% | 378 | 52% | 715 | 97% | 652 | 90% |

| Other Europe | 577 | 57% | 282 | 28% | 160 | 16% | 62 | 11% | 82 | 14% | 123 | 22% | 299 | 53% | 557 | 97% | 509 | 91% |

| Elsewhere | 167 | 65% | 63 | 24% | 28 | 11% | 18 | 11% | 22 | 13% | 27 | 16% | 99 | 60% | 163 | 98% | 153 | 93% |

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||||||||

| London | 596 | 51% | 229 | 19% | 354 | 30% | 84 | 14% | 89 | 15% | 103 | 18% | 304 | 52% | 573 | 96% | 519 | 90% |

| Rest of England | 904 | 58% | 359 | 23% | 286 | 18% | 95 | 11% | 118 | 13% | 197 | 22% | 487 | 54% | 877 | 97% | 805 | 90% |

| Wales/Northern Ireland | 53 | 64% | 15 | 18% | 15 | 18% | 3 | 5.7% | 7 | 13% | 12 | 23% | 31 | 58% | 53 | 100% | 51 | 96% |

Completeness: last CD4 count 99%, ART status 99%, last viral load measurement 98%; proportions may not add up to 100% because of rounding.

Ever linked to care with no death reported: 2811.

Among those with no death reported and seen for care in 2019.

No significant difference in last CD4 count by gender (p = 0.417), age at last attendance (p = 0.833), ethnicity (p = 0.344), region of birth (p = 0.484) or region of residence (p = 0.083).

No significant difference in ART uptake by gender (p = 0.986), ethnicity (p = 0.900), region of birth (p = 0.830) or region of residence (p = 0.177).

No significant difference in viral suppression by gender (p = 0.401), ethnicity (p = 0.524), region of birth (p = 0.430) or region of residence (p = 0.343).

Overall, 77% (n = 3849) of people who inject drugs were linked to HIV outpatient care post‐diagnosis. Of the 1430 deaths among people who inject drugs with HIV, nearly three‐quarters (72%; 1025) occurred before 2000 and one‐fifth within a year of HIV diagnosis (20%; 288) (Table 1). The median age of death increased from 36 years (IQR: 32–44) among those diagnosed in 1981–1989 to 42 years (IQR: 37–51) among those diagnosed in 2010–2019 (p < 0.001).

Quality of HIV care

Of the 3548 people who inject drugs diagnosed with HIV not reported as having died by the end of 2019, 21% (737) had no evidence of attending for HIV care following diagnosis, and 35% (1258) last attended prior to 2019 (Table 2). Of those who last attended for HIV care in 2019, 74% (1134/1530) had a last CD4 count of ≥350 cells/µl, 97% (1503/1550) were reported as being on ART, and 90% (1375/1520) had a suppressed viral load (92% [1360/1479] among those on ART) (Table 2). There was no difference in last CD4 count by gender, age at last attendance, ethnicity, region of birth, or residence (Table 2). A lower proportion of people who inject drugs who were of younger age at last care attendance were on treatment and/or virally suppressed compared with older people who inject drugs (p = 0.003 and p = 0.002, respectively) (Table 2). In sensitivity analysis, when people who inject drugs last seen for care between 2010 and 2018 (no further follow‐up or death reported) were included and assumed to not be on treatment or virally suppressed, ART coverage in the injecting population was 70% (1503/2153), and overall viral suppression was 65% (1375/2123).

Risk and protective behaviours

From 1990 to 2019, an average of 2947 people who inject drugs participated in the UAM Survey annually, with 3208 participants in 2019 (demographic profile Figure S2a–e). Similar to previous years, the majority of people who inject drugs taking part in 2019 were men (71%; 2264/3201), born in the UK (93%; 2865/3067), and recruited in England, outside of London (76%; 2426/3208). In 2019, 17% (533/3208) of those recruited were aged ≥50 years compared with <1.0% (4/1515) in 1990 (p < 0.001) (Figure S2b). The median age of participation increased steadily from 26 years (IQR: 23–31) in 1990 to 40 years (IQR: 35–47) in 2019 (p < 0.001), as did the median injecting duration (6 years [IQR: 2–12] to 15 years [IQR: 7–22]; p < 0.001). The proportion of survey participants that reported currently injecting increased from 58% (874/1499) in 1990 to a peak of 77% (2020/2628) in 2001, then declined over the last two decades to 48% (1475/3103) in 2019 (Figure S2e).

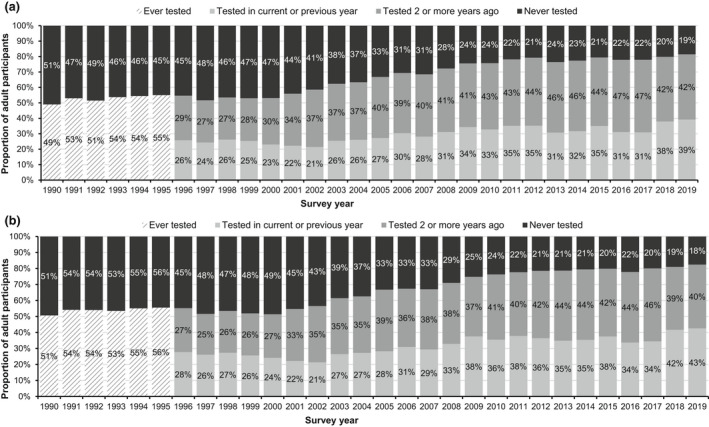

Over time, the proportion that reported ever testing for HIV increased steadily among all participating people who inject drugs, from 49% (740/1510) in 1990 to 81% (2455/3014) in 2019 (p < 0.001), as well as among those currently injecting, from 51% (442/873) in 1990 to 82% (1158/1404) in 2019 (p < 0.001). The proportion of those currently injecting who reported being tested for HIV in the current or previous year increased from 28% (646/2325) in 1996 to 43% (598/1404) in 2019 (p < 0.001) (Figure 2). However, in the most recent survey year, 18% (246) of those currently injecting reported never being tested for HIV.

FIGURE 2.

HIV testing history among (a) people who have ever injected drugs and (b) those reporting currently injecting in the last month by survey year: England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1990–2019. Completeness: ever tested for HIV 97% (year of last test collected from 1996 onwards)

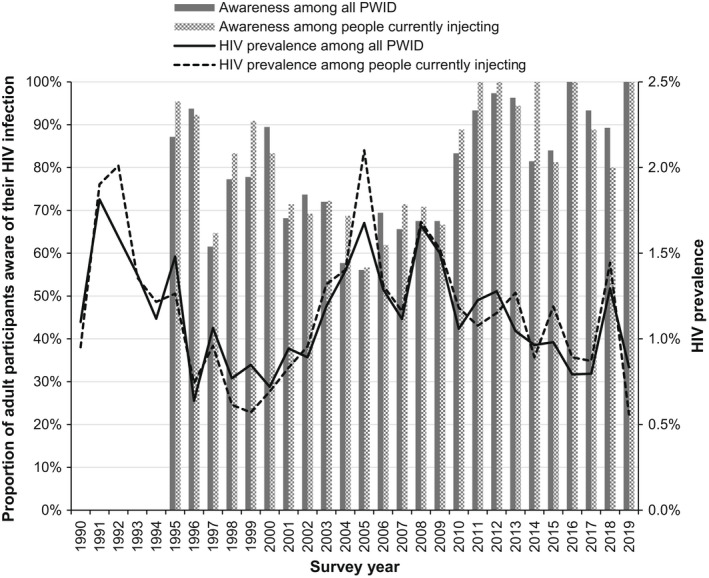

Overall, HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs fluctuated around 1.0% (range: 0.63%–1.8%) over time (Figure 3), with no difference between people reporting currently versus formerly injecting (p = 0.331). In 2019, HIV prevalence was 0.83% (26/3139); in people who inject drugs, HIV was more common among those born outside of the UK than those born in the UK (2.8% [7/250]) vs. 0.68% [19/2806], respectively; p = 0.001) and among those recruited in London than those recruited outside of London (3.6% [16/443] vs. 0.37% [10/2696], respectively; p < 0.001). Awareness of HIV infection has also fluctuated over time, rising from 56% (23/41) in 2005, when awareness was lowest, to 100% (23/23) in 2019, though numbers are small.

FIGURE 3.

HIV prevalence among people who have ever injected drugs participating in the Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring (UAM) Survey and those who reported currently injecting in the last month by survey year: England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1990–2019. Completeness: 98% of UAM Survey samples able to be tested for antibodies to HIV

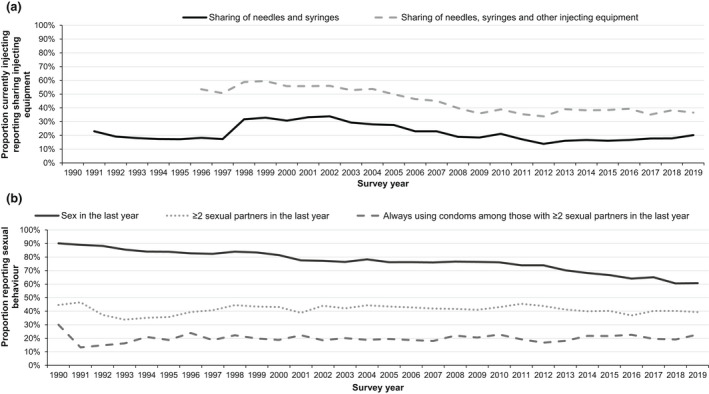

Underlying risk behaviours among people who inject drugs have evolved since the beginning of the HIV epidemic. The proportion of those currently injecting who reported sharing needles/syringes peaked in 2002 at 34% (588/1735) before decreasing to a low of 14% (224/1617) in 2012 (Figure 4a). Since 2012, sharing of needles/syringes has increased by 6% to 20% (288/1426) in 2019 (p = 0.050). In parallel, sharing of needles/syringes and injecting paraphernalia such as spoons and filters declined from a high of 60% (1386/2329) in 1999 to a low of 34% (546/1613) in 2012 (Figure 4a). Since 2012, sharing of needles/syringes and injecting paraphernalia has remained stable and was 37% (523/1429) in 2019 (p = 0.250).

FIGURE 4.

Injecting and sexual risk behaviours among people who inject drugs: England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, 1990–2019. (a) Sharing of injecting equipment among people reporting currently injecting drugs. (b) Sexual behaviour in the last year among people who have ever injected drugs. Completeness: sharing of needles/syringes 94%, sharing of needles/syringes/other equipment 96%, sex in the last year 97%, sexual partners 97%, condom use 90%. Sharing data from 1990 were excluded because only a small sample of participants answered the question as this question was introduced during 1990 (n = 22)

In terms of sexual risk behaviours, the proportion of people who inject drugs reporting vaginal and/or anal sex in the last year steadily declined from 90% (1342/1489) in 1990 to 61% (1851/3050) in 2019 (p < 0.001) (Figure 4b). The proportion of those reporting sex in the past year with two or more partners declined slightly over the 30 years (p < 0.001); in 2019, this figure was 39% (700/1778). Similar trends in consistent condom use among those with two or more sexual partners in the past year can be seen in Figure 4b, with a slight decline since 1990 to 23% (130/571) in 2019 (p < 0.001). In 2019, 69% of people who inject drugs reported sexualised drug use in the last year.

DISCUSSION

The HIV epidemic among people who inject drugs in EW&NI has been relatively contained compared with in other countries [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. New HIV diagnoses among people who inject drugs have declined over the past 30 years since the peak in the mid‐1980s. While HIV prevalence has fluctuated over time, it has remained relatively low at around 1.0%, despite those participating in the UAM Survey having had a long duration of injection risk exposure. The prompt introduction and high coverage of harm reduction measures, such as needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) and opioid substitution therapy, early on in the epidemic dramatically limited the transmission of HIV among people who inject drugs [11, 12]. The diversification of new diagnoses among people who inject drugs, with a higher proportion of older people and those born outside of the UK being diagnosed over time, is likely reflective of changes in the underlying injecting population (e.g. ageing cohort) and of the underlying expansion of HIV testing outside of traditional settings in the UK to reach previously underserved groups [13, 14, 15]. The shift in geography of diagnoses over the last 40 years reflects the increase in IDU outside of London since the early 1990s [13, 14]. The small peaks in diagnoses across regions is likely to reflect local testing patterns and case‐finding efforts.

In other countries in Europe, HIV prevalence in the injecting population has been reported to be much higher [16, 17], such as in Estonia (60%), Spain (48%), and Poland (18%) [10]. In the last decade, HIV diagnoses among people who inject drugs in Europe have increased, with outbreaks in Greece and Romania in 2010–2011 [17, 18, 19, 20, 21], Luxembourg in 2014 [22] and Ireland in 2015 [23]. These outbreaks are thought to be associated with a rise in the injection of stimulant‐based novel psychoactive substances and/or a result of national economic crisis, leading to an increase in homelessness and substantial cuts to harm reduction initiatives targeted to the injecting population [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. Despite high coverage of harm reduction interventions, the high levels of homelessness and incarceration and a shift to the injection of cocaine have contributed to an ongoing outbreak of HIV among people who inject drugs in the Greater Glasgow and Clyde area of Scotland, with high case numbers since 2015 [24, 25]. These outbreaks and the rise in new HIV diagnoses among those born outside the UK emphasise the importance of the continued monitoring of infections and behaviours among people who inject drugs in an effort to maintain the low prevalence of HIV seen in EW&NI, especially as UAM Survey data from the past decade show that stimulant use is on the rise in EW&NI. Injection of crack cocaine in the last month increased by 28% since 2010 to 57% in 2019, and injection of powder cocaine in the last month increased by 10% to 17% in 2019 [3].

Bio‐behavioural data from the UAM Survey indicate there is still room for improvement in the coverage of HIV prevention interventions in EW&NI. Though the uptake of HIV testing has increased over time in EW&NI, there has been no change over the last decade; in 2019, one in five people currently injecting drugs, considered at risk of acquiring HIV, reported never having been tested for HIV, with another two in five not having been tested in the last 2 years. This is despite having been in contact with drug‐ and alcohol‐related and other health care services, demonstrating missed opportunities for testing [26, 27]. UK HIV testing guidelines recommend people who inject drugs be tested for HIV on an annual basis and that drug services offer testing at the first assessment and consider repeat testing with ongoing risk [28, 29]. This is supported by these analyses of HIV surveillance data on late diagnosis of HIV among people who inject drugs. Late diagnosis is the most important predictor of morbidity and mortality, with those diagnosed late having a 10‐fold risk of death in the year following diagnosis [30]. The proportion of people who inject drugs diagnosed late has not declined in the last decade, and—compared with other risk groups—people who inject drugs are disproportionally affected [26]. There has also been no reduction in levels of sharing of injecting equipment in the last 10 years, with one in five of those currently injecting reporting sharing needles/syringes and two in five sharing needles/syringes and other injecting equipment in 2019. Only two‐thirds of people who inject drugs report adequate NSP provision [3, 4]. These data showing suboptimal uptake of testing and NSP, which are key public health interventions for the reduction of HIV transmission among people who inject drugs, highlight the potential for an increase in cases, especially in the context of the ongoing HIV outbreak in Scotland and the rise in stimulant use. This risk is compounded by a significant reduction in funding and accountability for drug treatment in the UK in recent years, as well as restricted access to harm reduction services as a result of the COVID‐19 pandemic [4, 31, 32]. There is also a growing unmet need among people who inject drugs with regard to mental/physical health, housing, and employment [31, 32].

Encouragingly, the majority (98%) of people who inject drugs diagnosed with HIV in EW&NI in the last decade were linked to specialist outpatient care. Overall, 97% of people who inject drugs and were in care in 2019 were on ART, and 92% of those were virally suppressed and non‐infectious. In 2018, 94% of the 2300 (95% credible interval: 2200–2600) people who inject drugs living with HIV were estimated to be diagnosed [26]. These data suggest that the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 90–90–90 targets for the elimination of HIV transmission have likely been met among people who inject drugs in EW&NI [33]. Previous research has shown that people who inject drugs have patient outcomes comparable to those acquiring HIV through sex between men and heterosexual sex [34]. The high standards of care can be attributed to the specialist service delivery in the UK, where care and ART are both free and easily accessible [35]. However, there is some evidence that people who inject drugs in EW&NI experience delays in accessing HIV care in the year after diagnosis, and these analyses show disparities in outcomes among younger individuals [36]. Furthermore, surveillance data indicate that 21% of people who inject drugs who were ever diagnosed with HIV never attended for care, with no further HIV clinical follow‐up. This may be a true reflection of poor engagement with services or due to data issues (such as an under‐reporting of deaths), a lack of reporting of outward migration, or individuals diagnosed in the early years of the epidemic testing under a false name so their patient records cannot be merged. If those people are still alive and not accessing care or ART, then viral suppression in the injecting population is likely much lower. People who inject drugs face significant structural and social barriers to accessing medical services, such as laws criminalising drug use, stigma and discrimination by service providers, psychosocial instability, homelessness, and unemployment [37, 38].

Though HIV prevalence is low in the UK, people who inject drugs are disproportionately affected by other infections, particularly HCV [3, 4], the prevalence of which was high in 2019 in EW&NI, with 54% of people who inject drugs having antibodies to HCV and 23% chronically infected. In total, 65% of people who inject drugs with HIV had HCV co‐infection [3]. HCV incidence has not declined over the last 5 years [4, 39]. In 2019, only 30% of people who inject drugs were aware of their chronic infection and 87% had ever been tested for HCV [3]. HBV prevalence among people who inject drugs in EW&NI was 9.5% in 2019, and 38% of individuals who injected drugs in the last year reported having a sore, open wound, or abscess at an injection site, possible symptoms of a bacterial infection [3, 4]. Comprehensive services for people who inject drugs must be maintained and BBV testing and treatment expanded to reduce transmission.

This is the first national study to describe the last 40 years of the HIV epidemic among people who inject drugs in EW&NI. However, it is important to note the limitations. Importantly, the sample of people who inject drugs recruited to the UAM Survey are those in contact with specialist drug and alcohol services; people who inject drugs not in contact with these services are not captured and represent a small sub‐group of people who are highly marginalised and underserved, at much higher risk of BBV infection [40]. In addition, these analyses do not include men who acquired their HIV through sex between men who also reported IDU; in the routine archiving of HIV surveillance data, probable acquisition route is assigned based on hierarchical likelihood of risk. It is likely these individuals are also under‐represented in the UAM Survey data; given the differences in drugs used, men who have sex with men are possibly less likely to attend drug and alcohol services, which are focussed on heroin and crack cocaine. Risk behaviours are self‐reported by people who inject drugs and may be influenced by both recall and social desirability bias. Nevertheless, self‐reporting of risk has been found to be reliable [41]; social desirability bias was reduced through self‐completion of the questionnaire and limiting the demographic information collected. As identifiers were not collected, participants in the UAM Survey could not be de‐duplicated if they took part across multiple years and could not be followed over time to look at changes in behaviour. The UAM Survey questionnaire does not ask about uptake of HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a key component of any HIV prevention programme. HIV PrEP has been found to be both a feasible and an acceptable prevention approach for people who inject drugs, particularly among those at higher risk of sexual acquisition of HIV [42, 43, 44]. However, barriers to PrEP utilisation among people who inject drugs need to be addressed, including low PrEP knowledge and concerns about side effects [43].

The HIV epidemic among people who inject drugs in EW&NI has remained relatively contained compared with in other European countries, most likely because of the prompt implementation of an effective national harm reduction programme. However, reported risk behaviours among people who inject drugs indicate the potential for outbreaks and for HIV cases to increase. Investment is needed to maintain and strengthen services for people who inject drugs and eliminate gaps in provision [32]. HIV testing must be readily available and offered across a variety of settings, including low‐threshold services, to reach people who inject drugs who are underserved and most vulnerable. Prompt linkage to HIV care and treatment and support for retention in care and ART adherence among people who inject drugs are essential to ensure the elimination of HIV transmission and reduce inequalities.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

EP, RJH, AS, EE, CC, VH, MD, VD, SI, and CE have no conflicts of interest to declare. SC has received consultancy fees from the Centre of Excellence for Health, Immunity, and Infections, Rigshospitalet, outside the submitted work. JS has contracts via Public Health England with two diagnostic manufacturers for the evaluation of hepatitis kits as part of the World Health Organization kit evaluation programme outside the submitted work. CC has received consultancy fees from Watipa outside the submitted work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors critically appraised the manuscript and approved its submission. SC led the study, carried out data analyses, drafted the manuscript, incorporated author comments, and was responsible for the final submitted version. SC and VH conceived this research study. CE led the UAM Survey data collection. CC cleaned, processed, and archived the HIV surveillance data, and EE and CE cleaned, processed, and archived the UAM Survey data. AS, SC, and CC extracted the HIV surveillance data, and EE and SC extracted the UAM Survey data. JS and SI processed all the UAM Survey dried‐blood spot samples and carried out the testing. RJH provided statistical support. MD, RJH, VH, VD, and EP were involved in analysis interpretation and contributed important intellectual content to the discussion and conclusions.

Supporting information

Fig S1‐S2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the continuing collaboration of people living with HIV and the clinicians, microbiologists, immunologists, public health practitioners, occupational health doctors and nurses, and other colleagues who contribute to the surveillance of HIV in the UK. We also thank the drug and alcohol services that have facilitated delivery of the UAM Survey and the participants recruited for giving their time to take part. Thanks also to Katelyn Cullen and Zheng Yin for contributing to early versions of this work. Finally, we acknowledge the large number of epidemiologists, virologists, scientists, and data managers who have contributed to the development, implementation, and analyses of the surveillance systems and surveys over the past 30–40 years; without your hard work and dedication, this article would not be possible.

Croxford S, Emanuel E, Shah A, et al. Epidemiology of HIV infection and associated behaviours among people who inject drugs in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland: Nearly 40 years on. HIV Med. 2022;23:978–989. doi: 10.1111/hiv.13297

Valerie Delpech and Emily Phipps are joint last authors.

Funding information

No funding was received for this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Home Office . Drug Misuse: Findings from the 2019/20 Crime Survey for England and Wales. Home Office; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hay G, Rael dos Santos A, Worsley J. Estimates of the prevalence of opiate use and/or crack cocaine use, 2011/12: Sweep 8 report. Liverpool John Moores University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Public Health England, Public Health Scotland, Public Health Wales, Public Health Agency Northern Ireland . Shooting up: Infections among people who inject drugs in the United Kingdom 2019. PHE; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. UK Health Security Agency, Public Health Scotland, Public Health Wales, Public Health Agency Northern Ireland . Shooting up: Infections and other injecting‐related harm among people who inject drugs in the United Kingdom 2020. UKHSA; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aghaizu A, Brown AE, Nardone A, Gill ON, Delpech VC, contributors . HIV in the United Kingdom 2013 report: data to end 2012. London; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. European Centre for Disease Surveillance and Control , World Health Organization . HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2020 (2019 data). ECDC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jolley E, Rhodes T, Platt L, et al. HIV among people who inject drugs in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia: a systematic review with implications for policy. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):e001465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams LD, Ibragimov U, Tempalski B, et al. Trends over time in HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs in 89 large US metropolitan statistical areas, 1992–2013. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;45:12‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tarasuk J, Zhang J, Lemyre A, Cholette F, Bryson M, Paquette D. National findings from the Tracks Survey of people who inject drugs in Canada, Phase 4, 2017‐2019. Paper presented at the International Conference on Hepatitis Care in Substance Users; Virtual; 2021 Oct 13–15.

- 10. Stengaard AR, Combs L, Supervie V, et al. HIV seroprevalence in five key populations in Europe: a systematic literature review, 2009 to 2019. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(47):2100044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hope VD, Harris RJ, De Angelis D, et al. Two decades of successes and failures in controlling the transmission of HIV through injecting drug use in England and Wales, 1990 to 2011. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(14):20762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stimson GV. AIDS and injecting drug use in the United Kingdom, 1987–1993: the policy response and the prevention of the epidemic. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(5):699‐716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lewer D. The changing population of people who inject drugs: Evidence from 30 years of the Unlinked Anonymous Monitoring Survey of People who Inject Drugs. Presented at the UAM 30th Anniversary Symposium; Virtual; 2021 July 22.

- 14. Lewer D, Croxford S, Desai M, et al. Temporal trends in the population characteristics of people who inject drugs in the United Kingdom 1980‐2019: evidence from repeated cross‐sectional surveys. Accepted to Addiction 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Croxford S, Yin Z, Kall M, et al. Where do we diagnose HIV infection? Monitoring new diagnoses made in nontraditional settings in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. HIV Med. 2018;19(7):465‐474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, European Centre for Disease Surveillance and Control . Joint EMCDDA and ECDC rapid risk assessment: HIV in injecting drug users in the EU/EEA, following a reported increase of cases in Greece and Romania. EMCDDA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pharris A, Wiessing L, Sfetcu O, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus in injecting drug users in Europe following a reported increase of cases in Greece and Romania, 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(48):20032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Niculescu I, Paraschiv S, Paraskevis D, et al. Recent HIV‐1 outbreak among intravenous drug users in Romania: evidence for co‐circulation of CRF14_BG and subtype F1 strains. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2015;31(5):488‐495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oprea C, Ceausu E, Ruta S. Ongoing outbreak of multiple blood‐borne infections in injecting drug users in Romania. Public Health. 2013;127(11):1048‐1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Botescu A, Abagiu A, Mardarescu M, Ursan M. HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users in Romania: Report of a recent outbreak and initial response policies. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sypsa V, Paraskevis D, Malliori M, et al. Homelessness and other risk factors for HIV infection in the current outbreak among injection drug users in Athens, Greece. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):196‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arendt V, Guillorit L, Origer A, et al. Injection of cocaine is associated with a recent HIV outbreak in people who inject drugs in Luxembourg. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0215570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Giese C, Igoe D, Gibbons Z, et al. Injection of new psychoactive substance snow blow associated with recently acquired HIV infections among homeless people who inject drugs in Dublin, Ireland, 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20(40). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ragonnet‐Cronin M, Jackson C, Bradley‐Stewart A, et al. Recent and rapid transmission of HIV among people who inject drugs in Scotland revealed through phylogenetic analysis. J Infect Dis. 2018;217(12):1875‐1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McAuley A, Palmateer NE, Goldberg DJ, et al. Re‐emergence of HIV related to injecting drug use despite a comprehensive harm reduction environment: a cross‐sectional analysis. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(5):e315‐e324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Halloran C, Sun S, Nash S, et al. HIV in the United Kingdom: towards zero HIV transmissions by 2030 ‐ 2019 report London: public health England; 2019.

- 27. Furukawa NW, Blau EF, Reau Z, et al. Missed opportunities for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing during injection drug use‐related healthcare encounters among a cohort of persons who inject drugs with HIV diagnosed during an outbreak‐Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky, 2017–2018. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(11):1961‐1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clinical Guidelines on Drug Misuse and Dependence Update 2017 Independent Expert Working Group . Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management. Department of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Palfreeman A, Sullivan A, Rayment M, et al. British HIV association/British association for sexual health and HIV/British infection association adult HIV testing guidelines 2020. HIV Med. 2020;21(Suppl 6):1‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown AE, Kall MM, Smith RD, Yin Z, Hunter A, Delpech VC. Auditing national HIV guidelines and policies: the United Kingdom CD4 surveillance scheme. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:149‐155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Black C. Review of drugs: phase one report. Home Office; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Black C. Review of drugs part two: prevention, treatment, and recovery. Home Office; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . 90–90‐90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delpech V, Brown AE, Croxford S, et al. Quality of HIV care in the United Kingdom: key indicators for the first 12 months from HIV diagnosis. HIV Med. 2013;14(Suppl 3):19‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. British HIV Association . Standards of care for people living with HIV in 2013. BHIVA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Croxford S, Burns F, Copas A, Yin Z, Delpech V. Trends and predictors of linkage to HIV outpatient care following diagnosis in the era of expanded testing in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: results of a national cohort study. HIV Med. 2021;22(6):491‐501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Joint Action on HIV and Co‐infection Prevention and Harm Reduction, European Commission . Report on PWID barriers to accessing HIV, HCV and TB services and on strategies for overcoming these barriers. EC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Neale J, Tompkins C, Sheard L. Barriers to accessing generic health and social care services: a qualitative study of injecting drug users. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16(2):147‐154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Public Health England . Hepatitis C in the UK 2020: Working to eliminate hepatitis C as a major public health threat. PHE; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hickman M, Hope V, Brady T, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence, and injecting risk behaviour in multiple sites in England in 2004. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14(9):645‐652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Latkin CA, Vlahov D, Anthony JC. Socially desirable responding and self‐reported HIV infection risk behaviors among intravenous drug users. Addiction. 1993;88(4):517‐526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grimshaw C, Boyd L, Smith M, Estcourt CS, Metcalfe R. Evaluation of an inner city HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis service tailored to the needs of people who inject drugs. HIV Med. 2021;22(10):965‐970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Biello KB, Bazzi AR, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Perspectives on HIV pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization and related intervention needs among people who inject drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hershow RB, Gonzalez M, Costenbader E, Zule W, Golin C, Brinkley‐Rubinstein L. Medical providers and harm reduction views on pre‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. AIDS Educ Prev. 2019;31(4):363‐379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1‐S2