Abstract

Aims

The aim of this study was to explore the level of agreement on drug–drug interaction (DDI) information listed in three major online drug information resources (DIRs) in terms of: (1) interacting drug pairs; (2) severity rating; (3) evidence rating; and (4) clinical management recommendations.

Methods

We extracted information from the British National Formulary (BNF), Thesaurus and Micromedex. Following drug name normalisation, we estimated the overlap of the DIRs in terms of DDI. We annotated clinical management recommendations either manually, where possible, or through application of a machine learning algorithm.

Results

The DIRs contained 51 481 (BNF), 38 037 (Thesaurus) and 65 446 (Micromedex) drug pairs involved in DDIs. The number of common DDIs across the three DIRs was 6970 (13.54% of BNF, 18.32% of Thesaurus and 10.65% of Micromedex). Micromedex and Thesaurus overall showed higher levels of similarity in their severity ratings, while the BNF agreed more with Micromedex on the critical severity ratings and with Thesaurus on the least significant ones. Evidence rating agreement between BNF and Micromedex was generally poor. Variation in clinical management recommendations was also identified, with some categories (i.e., Monitor and Adjust dose) showing higher levels of agreement compared to others (i.e., Use with caution, Wash‐out, Modify administration).

Conclusions

There is considerable variation in the DDIs included in the examined DIRs, together with variability in categorisation of severity and clinical advice given. DDIs labelled as critical were more likely to appear in multiple DIRs. Such variability in information could have deleterious consequences for patient safety, and there is a need for harmonisation and standardisation.

Keywords: clinical decision support, clinical management of drug interactions, drug information, drug–drug interaction, drug–drug interaction software

What is already known about this subject

There is a variety of online DIRs, which differ in coverage, content and inclusion criteria, that are available to clinicians and other prescribers, mainly for prescribing decision support purposes.

Previous studies have described major discrepancies between widely used DIRs on inclusion of critical DDIs or interactions of specific therapeutic categories, along with discordance in their severity and evidence ratings.

What this study adds

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to concurrently compare the similarity among complete datasets from DIRs in terms of inclusion of drug pairs, recommendations for clinical management, severity and evidence of DDIs.

Considerable variation was identified in all types of information for DDIs, which has important clinical implications for patient safety and requires efforts towards harmonisation and standardisation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coadministration of multiple drugs increases the risk of drug–drug interactions (DDIs). A DDI can be defined as the modification in the therapeutic effect of one or more medications due to the presence of concomitant medications, and can lead to clinically significant events, caused by either an increase in the effect of the interacting drug leading to an adverse drug reaction (ADR), or a decrease in its effect that results in lack of efficacy. Previous studies have reported that DDIs are a significant cause of hospitalisation, being responsible for 16.6% of cases where the cause was an ADR and around 1% of all hospital admissions. 1 The risk for DDIs increases during hospitalisation and after discharge, as there is a high prevalence of administration of potentially interacting drug combinations. 2

As new medicines gain approval each year, the volume of possible drug combinations is constantly growing. At the same time, the rising numbers of people with multimorbidity together with increasing life expectancy around the world are associated with the phenomenon of polypharmacy, which aggravates the impact of DDIs in clinical practice. According to a recent review, more than one in three people in England aged 60 and older are exposed to at least five medicines at the same time, with more than a third of all people above 80 being on eight or more medicines. 3

The clinical manifestation of DDIs depends on several factors. Potential DDIs, based on pharmacological knowledge, far outnumber those which lead to clinically significant adverse effects. 4 Despite the theoretical potential for an ADR to occur due to a DDI, there are several factors that can affect the actual behaviour of drug molecules inside the human body, including dosage and patient characteristics (e.g., age, number and type of morbidities, etc). Also, genetic polymorphisms of drug‐metabolising enzymes, drug transporters or drug receptors may be responsible for the appearance of some DDIs. 5 Therefore, it is difficult to accurately predict the occurrence of a clinically significant DDI in an individual patient. To overcome this problem, clinicians are commonly aided by drug information resources (DIRs) to assess the risk–benefit ratio of each drug added to the treatment schedule. DIRs can be either open source or commercial, and they are often incorporated in computerised clinical decision support (CDS) tools.

The availability of DIR information related to severity, evidence availability and clinical options for management of DDIs (e.g., entirely avoid the combination, monitor, adjust dose, etc.) are central to the development of CDS. 6 Inconsistencies between DIRs may confuse clinicians and impact clinical decisions. 7 Previous studies have assessed the level of agreement of DIRs, mainly in terms of listing of DDIs and severity ratings. However, most of them were restricted to only DDI listing for a limited number of drugs, specific therapeutic categories, or did not focus solely on clinical resources. 8 , 9 , 10 Moreover, the ability of a DIR to identify clinically relevant DDIs or capture critical DDIs (e.g., FDA black box warnings, ONC [Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology] high priority list 11 ) has also been explored. 12 , 13 , 14 However, it remains unclear to what extent DIRs from different geographic locations agree on their DDI listings as well as DDI‐related information.

The aim of this study was to assess the concordance of leading clinical resources for DDIs from three different countries of origin in terms of: (1) inclusion of interacting drug pairs; (2) severity rating; (3) evidence rating; and (4) clinical management recommendations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study that attempts to compare multiple types of information pertinent to DDIs at the same time across entire DIRs. To ensure clinical utility, only clinically relevant resources were included in the present study (see Figure S1 in the Supporting Information for an overview of online DDI resources). Data sources of potential DDIs (e.g., DrugBank) that are mainly used for scientific research purposes were not taken into consideration.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data sources

DDI data from two open‐source DIRs and one commercial online DIR were included in our evaluation: the British National Formulary 15 (hereafter called BNF), Interactions Thesaurus 16 by the French Medicines Agency (Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des produits de santé, ANSM) (hereafter called Thesaurus) and IBM Micromedex 17 (hereafter called Micromedex). The BNF is extensively used in the UK. 18 , 19 Thesaurus is maintained and updated annually by ANSM, being considered as the official source of information relevant to DDIs for French clinicians. Micromedex is a leading clinical information resource, listed as one of the statutorily named compendia in the Medicaid program and is widely used in the United States. 20 , 21 The BNF and Thesaurus are publicly available online, while Micromedex can only be accessed via subscription.

2.2. Data extraction

Automated web data collection (web scraping) was executed for BNF and Micromedex in Python 3.6 22 with terms of use that permit data collection. Thesaurus is a portable document format (PDF) file that is curated and updated annually. An R package ( IMthesaurusANSM 23 ) enabled the automatic data extraction from the original document (version September 2019). The types of extracted information from each DIR are summarised in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Extracted information from the drug information resources

| DIR | Extracted fields | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| BNF (accessed June 2018) |

|

(a) Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) (e.g., atropine); (b) Drug classes (e.g., combined hormonal contraceptives); (c) Herbs and supplements (e.g., peppermint oil); (d) Foods and beverages (e.g., grapefruit juice). |

|

Thesaurus ‐ September 2019 update (accessed July 2020) |

|

(a) Drug ingredient; (b) Drug classes. |

|

Micromedex In‐depth answers database (detailed evidence‐based information) (accessed August 2018) |

|

(a) Drug ingredients; (b) Combination drugs; (c) Food; (d) Tobacco; (e) Lab tests. |

We mapped DDIs from Thesaurus at the drug class level (e.g., beta blockers) to their constituent individual drug ingredients using a mapping table available on the ANSM website. We also excluded DDIs from Micromedex containing drug combinations (e.g., hydroxyamphetamine/tropicamide), as those simply collated DDIs from the combination's individual ingredients; hence, only single ingredient drug interactions were considered. Also, cases where drug names of an interacting pair were swapped (i.e. [D1, D2] and [D2, D1]) were considered equivalent and duplicate entries were removed from the tables that stored the extracted data (BNF original table, Thesaurus original table and Micromedex original table).

2.3. Drug name normalisation

Initial drug names were normalised to RxNorm Ingredients (for US‐marketed medicines) 24 and RxNorm Extension Ingredients (for medicines not found in RxNorm) 25 using the Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) Usagi tool. 26 Some names were too general to be mapped (e.g., insulins), or were not present in either vocabulary. Thus, interacting pairs containing at least one unmapped drug were excluded from the corresponding DIR table. As the scope of this study was limited to DDIs, only interacting pairs containing drugs were included in the final DIR tables and interactions with herbs, alcohol, food, etc., were excluded. The final tables (BNF final table, Thesaurus final table and Micromedex final table) contained drug interacting pairs and associated information based on normalised drug names. Any duplicate entries based on common normalised names were combined into a single entry. For example, Metoprolol Tartrate and Metoprolol Succinate were both mapped to the RxNorm entity Metoprolol, and their interactions were merged to produce a single set.

2.4. Comparison of resources

2.4.1. Listing of DDIs

The pairwise and three‐way overlaps of the final DIR tables were estimated by calculating counts of common drug pairs across the DIRs as well as coverage rates (i.e., the percentage of a set A covered by B, where B is a subset of A). The directionality of interacting drug pairs was not taken into account (i.e., [D1, D2] and [D2, D1] were considered equivalent). A DIR intersection list containing common interacting drug pairs among all three DIRs with their corresponding text descriptions from each source was generated.

2.4.2. Severity and evidence ratings

All three DIRs included severity ratings (Table 2a), while only the BNF and Micromedex contained separate text fields regarding evidence ratings (Table 2b). Some DDIs from Thesaurus appeared at the drug class level in the original source, which was associated with multiple severity ratings; thus, individual drugs were assigned all applicable ratings from the drug class during the mapping process. Also, some DDIs were linked to multiple severity ratings, based on the clinical circumstances (e.g., route of administration, dose, etc.). In all cases where multiple ratings were available for an individual DDI, the highest one was kept for further analysis.

TABLE 2.

Information contained in drug information resources on drug–drug interactions relating to (a) the severity ratings (in descending order as displayed in the original source); and (b) the evidence ratings

| DIR | Level | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| BNF | 1 – Severe a | The result may be a life‐threatening event or have a permanent detrimental effect. |

| 2 – Moderate | The result could cause considerable distress or partially incapacitate a patient; they are unlikely to be life‐threatening or result in long‐term effects. | |

| 3 – Mild | The result is unlikely to cause concern or incapacitate the majority of patients. | |

| 4 – Unknown | Used for those interactions that are predicted, but there is insufficient evidence to hazard a guess at the outcome. | |

| Thesaurus | 1 – Contraindicated a | |

| 2 – Not recommended a | ||

| 3 – Precautions for use | ||

| 4 – Take into consideration | ||

| Micromedex | 1 – Contraindicated a | The drugs are contraindicated for concurrent use. |

| 2 – Major a | The interaction may be life‐threatening and/or require medical intervention to minimise or prevent serious adverse effects. | |

| 3 – Moderate | The interaction may result in exacerbation of the patient's condition and/or require an alteration in therapy. | |

| 4 – Minor | The interaction would have limited clinical effects. Manifestations may include an increase in the frequency or severity of the side effects but generally would not require a major alteration in therapy. | |

| ||

| BNF | Study | For interactions where the information is based on formal study including those for other drugs with same mechanism (e.g., known inducers, inhibitors or substrates of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes or P‐glycoprotein). |

| Anecdotal | Interactions based on either a single case report or a limited number of case reports. | |

| Theoretical | Interactions that are predicted based on sound theoretical considerations. The information may have been derived from in vitro studies or based on the way other members in the same class act. | |

| Micromedex | Established (excellent) | Controlled studies have clearly established the existence of the interaction. |

| Theoretical (good) | Documentation strongly suggests the interactions exists, but well‐controlled studies are lacking. | |

| Probable (poor) | Available documentation is poor, but pharmacologic considerations lead clinicians to suspect the interaction exists; or, documentation is good for a pharmacologically similar drug. | |

Critical severity ratings.

To explore discrepancies among DIRs related to severity and evidence ratings for DDIs, we calculated the subset size, pairwise coverage rates and Jaccard indices for all possible pairs of DIR ratings.

2.4.3. Clinical management recommendations

We aimed to explore the consistency among the clinical management recommendations provided by the DIRs by analysing text descriptions from the DIR intersection list. The BNF provided a succinct description for each drug pair containing all types of available DDI information in a text field, while Thesaurus and Micromedex contained separate text fields (Conduite à tenir and Clinical Management, respectively) under each drug pair related to clinical management options.

Basic pre‐processing involved text conversion to lowercase, drug name blinding (i.e., replacement of all drug names with a common string), and sentence tokenisation using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) in Python 3.6. 27

The following advice categories were initially considered:

Avoid;

Use with caution;

Space dosing times;

Wash‐out;

Monitor;

Adjust dose;

Modify administration;

Use alternative;

Discontinue.

Cases that recommended clinicians to refer to literature or other resources, without mentioning any concrete clinical advice, were excluded.

The limited number of unique sentences sourced from BNF (n = 305) and Thesaurus (n = 387) following drug name blinding enabled manual sentence labelling, with each sentence being classified into one or multiple advice categories.

To annotate Clinical Management text descriptions in Micromedex (n = 4507), we developed a bespoke text classification process in Python using a methodology that has been widely implemented in similar tasks and provided the desired functionality while keeping the level of complexity low (Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). First, we annotated a subset of randomly selected unique sentences (n = 200) by considering the above‐mentioned categories. Then, each labelled sentence was tokenised into its constituent tokens (i.e., words) and stemming (i.e., reducing words to their word roots) was applied. We used term frequency‐inverse document frequency (tf‐idf) to calculate weights for each word in the annotated sentences. The goal of tf‐idf is to reduce the impact of very commonly occurring words in a corpus, assuming that they are less informative. Term frequencies are calculated by counting the relative frequency of each word appearing in each of the annotated sentences. Inverse document frequencies of each word (in its root form) are estimates of the overall presence of the word across all sentences (i.e., how commonly or rarely it appears). The formula for calculation of a word's tf‐idf is the following:

| (1) |

where represents the term frequency of the word, w, in the sentence, s (i.e., the number of times the word appears in the sentence divided by the total number of words in the sentence); is the total number of sentences in the corpus; and is the “document” frequency of the word, w (i.e., the number of sentences that contain the specific word). Weights were applied for sentence encoding to feed classifiers that used a supervised machine learning model called linear kernel Support Vector Machine (SVM) for binary text classification (i.e., each sentence was classified as to whether it belongs to each of the advice categories under consideration). We applied class weights to account for the imbalanced training sets (i.e., disproportion between the number of positive and negative instances) and used leave‐one‐out cross validation to evaluate performance of the difference classifiers through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. By estimating the positive predictive value (PPV) for the different thresholds, we excluded sentence classifiers with a PPV below 80% due to poor performance; the remaining, unannotated sentences from Micromedex were automatically labelled by the classifiers using the threshold with maximum sensitivity for PPVs above 80%. A subset (n = 100) of the automatically annotated sentences (validation set) was also manually annotated to independently estimate the classifiers' performance in the total set of Micromedex sentences.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Comparative assessment in terms of listing

Micromedex contained the largest number of DDI drug pairs (n = 65 446), as well as normalised ingredients involved in DDIs (n = 1967), followed by BNF (n = 51 481) and Thesaurus (n = 38 037) that covered 984 and 1001 normalised ingredients, respectively, in their DDI section. The collation of the three final DDI tables included 121 351 DDI drug pairs. The counts of initial drug names, normalised drug ingredients and unique DDIs in each DIR are summarised in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Number of initial drug names, normalised ingredients, and drug–drug interaction counts per drug information resource

| DIR | Initial drug names | Normalised ingredients | DDI counts |

|---|---|---|---|

| BNF | 1004 | 984 | 51 481 |

| Thesaurus | 1049 | 1001 | 38 037 |

| Micromedex | 2602 | 1967 | 65 446 |

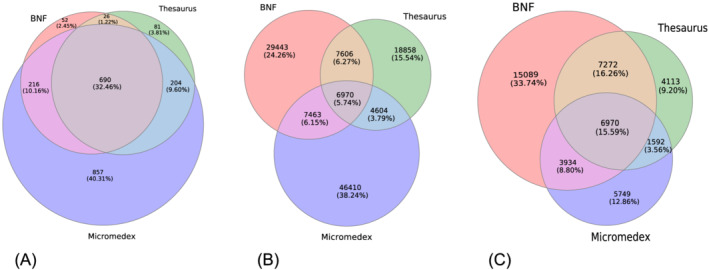

There were 690 common normalised ingredients involved in DDIs across all examined DIRs, with BNF and Micromedex sharing the largest number (n = 906), followed by Thesaurus and Micromedex (n = 894) and, lastly, the BNF and Thesaurus (n = 716) (Figure 1A). Almost four out of five DDI drug pairs (78.04%, n = 94 708) in the collated list were only mentioned by a single DIR, with 57.19% of BNF, 49.58% of Thesaurus and 70.91% of Micromedex DDI entries missing from the other two DIRs.

FIGURE 1.

Venn diagrams illustrating the intersections in terms of: (A) drug ingredients; (B) unique drug–drug interaction pairs included in the drug information resources; and (C) drug–drug interaction pairs included in the drug information resources only for the ingredient intersection subset. Each circle represents a drug information resource and their intersections show the number of ingredients/drug–drug interactions they share with each one of the other drug information resources

The percentage of DDIs mentioned in exactly two out of three DIRs was lower (16.21%, n = 19 673). BNF shared 14 576 DDIs with Thesaurus (28.31% of BNF; 38.32% of Thesaurus) and 14 433 DDIs with Micromedex (28.04% of BNF; 22.05% of Micromedex), while Thesaurus and Micromedex had 11 574 common DDIs (30.43% of Thesaurus; 17.68% of Micromedex). The intersection of the three DIRs in terms of DDIs (n = 6970) represented only 5.74% of the collated list, 13.54% of BNF, 18.32% of Thesaurus and 10.65% of Micromedex (Figure 1B).

In terms of DDIs restricted to common ingredients across the three DIRs (n = 44 719), more than half (n = 24 951) were only found in a single DIR (33.74% in the BNF alone, in comparison to 12.86% and 9.20% in Micromedex and Thesaurus, respectively), while 28.62% were present in two out of three DIRs. In the setting of ingredient‐restricted DDIs, the BNF intersected with large proportions of both Thesaurus (71.40%) and Micromedex (59.76%), while Thesaurus overlapped with less than half of BNF (42.81%). Finally, the intersection of the three DIRs represented 15.59% of the restricted DDIs (Figure 1C).

3.2. Comparative assessment of severity rating

The categorisation of DDIs in each DIR in terms of severity rating is outlined in Table 4. Regarding critical severity rating categories, almost one quarter (24.56%) of unique DDIs in the BNF were labelled as Severe, compared to 7.75% from Thesaurus characterised as Contraindicated, and 33.60% as Not recommended. In Micromedex, 8.76% of unique DDIs were mentioned as Contraindicated, while Major was the most frequent category (63.73%).

TABLE 4.

Number and percentage of drug–drug interactions by severity rating in each drug information resource

| Severity rating | BNF | Thesaurus | Micromedex |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 644 (24.56%) | 2949 (7.75%) | 5730 (8.76%) |

| 2 | 4997 (9.46%) | 12 779 (33.60%) | 41 713 (63.73%) |

| 3 | 273 (0.51%) | 8195 (21.54%) | 15 890 (24.28%) |

| 4 | 33 705 (65.47%) | 14 114 (37.11%) | 2113 (3.23%) |

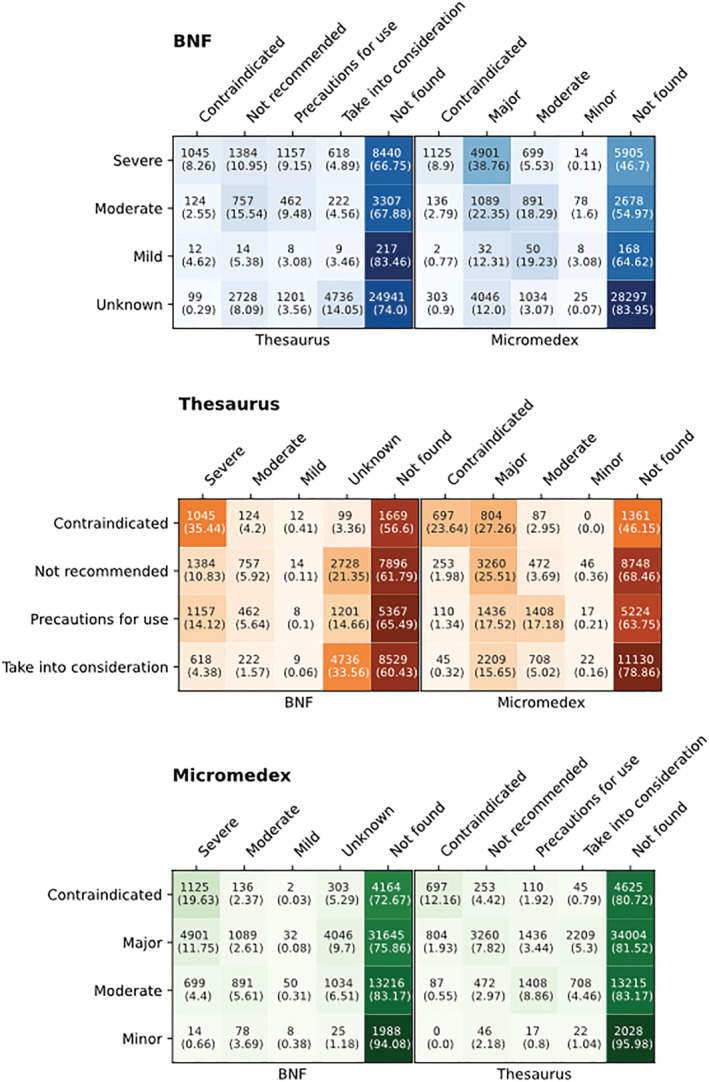

When considering the pairwise DIR overlap using coverage rates (Figure 2), the number of DDIs jointly rated as critical was:

2429 between BNF and Thesaurus, representing 19.21% of the BNF and 15.44% of Thesaurus critical DDIs;

6026 between the BNF and Micromedex (47.66% of BNF and 31.38% of Micromedex critical DDIs);

5014 between Thesaurus and Micromedex, covering 78.39% of Thesaurus and 26.33% of Micromedex critical DDIs);

1768 among all three DIRs (25.37% of the DIR intersection list).

FIGURE 2.

Pairwise comparison tables for the different drug–drug interaction severity levels. For tables (A)–(C), row labels contain the severity ratings of the drug information resource under consideration, while column labels represent the severity ratings of the remaining two drug information resources. A separate column has been added to include the numbers of unique drug–drug interactions missing from each of the other drug information resources. Each row contains the number of unique drug–drug interactions per severity rating of the drug information resource under consideration, subcategorised by the severity ratings of the other drug information resources. The numbers in parentheses represent the corresponding percentages of the various sets per severity rating of the drug information resource under consideration. Colour gradient shows the relative differences in the percentages mentioned among the various overlapping sets

The percentage of DDIs from the DIR intersection list that were considered critical by BNF, Thesaurus and Micromedex was 43.39% (n = 3024), 52.32% (n = 3647) and 81.51% (n = 5681), respectively.

A similarity matrix of the Jaccard index for all DIR severity rating combinations is included in Figure S3 in the Supporting Information.

3.3. Comparative assessment of evidence rating

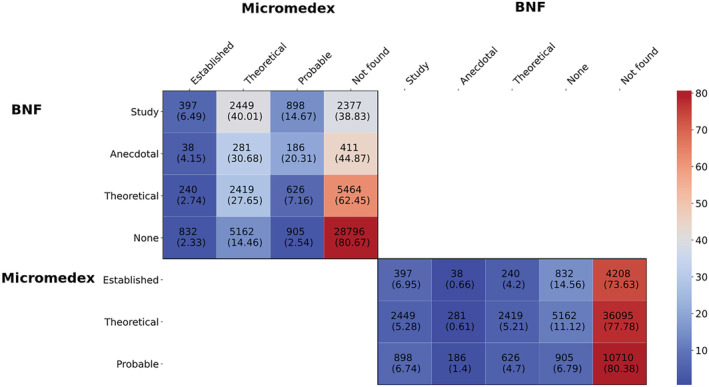

The BNF included evidence ratings in just around one third (30.66%) of its DDIs, with the majority being flagged as Theoretical (16.99%), followed by Study (11.89%) and Anecdotal (1.78%). In Micromedex, evidence ratings were consistently present under each DDI description. Theoretical was the most common category (70.91%), while Probable and Established included 20.36% and 8.73% of the DDIs mentioned in Micromedex.

Almost half (48.13%) of the DDIs from the DIR intersection list contained no evidence rating in the BNF; the remainder belonged to Study (28.05%), Theoretical (19.94%) and, lastly, Anecdotal (3.87%) evidence categories. According to Micromedex, most of them (64.51%) were Theoretical, with 19.94% and 15.55% being considered as Probable and Established, respectively.

Figure 3 shows the overlap of the different evidence categories between the two DIRs as a two‐by‐two grid with subset counts and coverage rates. Probable DDIs from Micromedex and DDIs with no evidence rating from BNF were absent in higher percentages in the other resource. In both DIRs, the percentage of missing DDIs increased as one moved towards DDIs with a “poorer” or no evidence rating in the other resource. Using the Jaccard index, agreement between ratings was generally low in all cases, with the BNF Study and Micromedex Theoretical categories being the most similar (0.04662), while the BNF Anecdotal and Micromedex Established had the lowest concordance (0.00573).

FIGURE 3.

Heatmap for evidence rating comparison between BNF and Micromedex, including counts and coverage rates

3.4. Comparative assessment of clinical management advice

In the BNF, no instances of the Discontinue advice category were identified in the DIR intersection list, while in Micromedex, counts for seven out of the nine advice categories are provided, as no sentence classifier was applied to extrapolate the remaining labels (i.e., Space dosing times and Modify administration) due to poor classifier performance (see Tables S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information for associated metrics). The subset of Micromedex descriptions associated with BNF cases that belonged to either of those two advice categories were manually annotated as a surrogate measure of concordance.

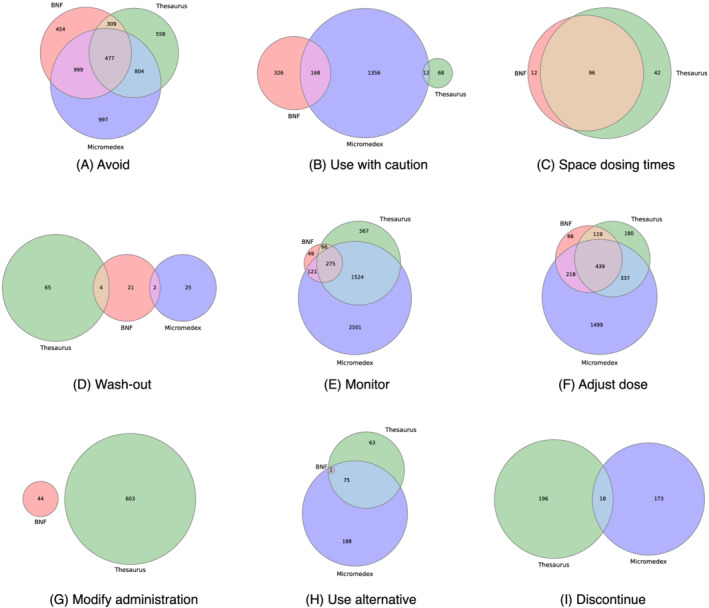

The classification of DIR intersection list entries in each DIR in terms of clinical management advice is shown in Table S3 in the Supporting Information. In the BNF, no advice was available in over half (56.41%) of the DDIs under consideration. The most common advice category was Avoid (32.12%) and the least frequently mentioned was Use alternative (0.01%). In Thesaurus, Monitor and Avoid jointly covered more than half of the total DDIs (34.89% and 30.82%, respectively), while recommendations related to Space dosing times, Use with caution and Wash‐out were only found in small percentages (1.98%, 1.15% and 0.99%, respectively). In Micromedex, the labelling process that was facilitated by sentence classifiers provided the following results: 63.43% of the DDIs were characterised as containing advice related to Monitor, 47.02% related to Avoid and 35.77% related to Adjust dose; low percentages represented Use alternative (3.79%), Discontinue (2.74%) and Wash‐out (0.39%) categories. In 5.38% of the Micromedex DDIs, no advice label was assigned.

The overlap in terms of the DDI‐related advice labels for the DDIs found in the DIR intersection list is illustrated using Venn diagrams (Figure 4). The BNF and Thesaurus did not share any DDIs in their Modify Administration and Use with caution categories, as opposed to the DDIs found in their Space dosing times and Adjust dose categories, which showed extensive overlap. Thesaurus and Micromedex did not have any common DDIs classified into their Wash‐out advice categories. Also, for Wash‐out and Use with caution advice categories, there was little agreement between any two DIRs. The three DIRs overlapped to a high degree in the Monitor category. In the majority of Space dosing times BNF cases (87.96%), Micromedex also contained the respective advice. For Modify administration, Micromedex included this advice for less than half (43.18%) of the BNF cases.

FIGURE 4.

Venn diagrams of the overlap in clinical management advice relating to drug–drug interactions in the drug information resources

4. DISCUSSION

This study reports on the consistency of DDI‐related information included in three major clinical DIRs from different geographic locations, namely the British National Formulary (BNF), Thesaurus and Micromedex. The DIRs differed in size and number of ingredients mentioned in the DDI sections. The number of ingredients in Micromedex was almost twice that found in the other two DIRs. This is most likely to have been due to the fact that the BNF and Thesaurus only include medicines licensed in their countries of origin (i.e., UK and France, respectively), while Micromedex includes a broader set of medicines. Although DIR ingredients overlapped to a significant extent, especially between BNF and Thesaurus, this overlap was not reflected on the DDI sets, which generally showed poor agreement. The BNF and Thesaurus shared the largest number of DDIs, in contrast to Thesaurus and Micromedex, which had the fewest DDIs in common.

Our study represents the most comprehensive assessment of the overlap in content and advice provided by different DIRs. However, our findings are consistent with previous studies. For instance, a study that analysed DDIs of fewer than 100 medicines reported less than 7% overall agreement among the examined sources. 8 , 9 A more recent analysis that compared three commercial DIRs in terms of listing and severity ranking of DDIs also identified very poor overlap (5%), although DDIs flagged as minor were not considered. 14

Severity ratings were not consistently reported in the BNF, as opposed to Thesaurus and Micromedex, where ratings were available in all cases. DDIs labelled as critical comprised approximately one fourth of BNF and more than 70% of Micromedex, in contrast to Thesaurus, where the least significant category was the most populous. Micromedex and Thesaurus showed similarity in their ratings across the different levels of severity. Between BNF and Thesaurus, their least significant categories (i.e., Unknown and Take into consideration, respectively) appeared to have a higher level of agreement. However, there was less concordance between BNF and Thesaurus on the classifications of DDIs in the high severity ratings, with the DDIs classified as Severe in the BNF being spread across the different Thesaurus categories. In terms of BNF and Micromedex, there was generally better agreement between their critical ratings than with the less severe ones. Apart from the BNF‐Thesaurus pair, the percentage of DDIs missing from a DIR increased as one moved to DDIs characterised as less severe by another DIR (i.e., increasing trend in the Not found column percentages as we go from top to bottom in the tables from Figure 2). Micromedex categorised the largest proportion from the DIR intersection list as being critical compared to the other DIRs, while around one fourth of the DDIs in the DIR intersection list were simultaneously labelled as critical by all three DIRs. Also, the pairwise intersections of DIRs covered larger proportions of the DDIs from the critical severity levels compared to the corresponding proportions from lower severity categories.

Although early studies concluded that significant discrepancies exist in severity ratings between DIRs, Fung et al.’s study advocated the presence of higher levels of agreement than previously reported, especially for the most severe DDIs. 8 , 9 , 14 Our results, suggesting better agreement between critical severity ratings between BNF and Micromedex, are partially in line with this observation.

Evidence categorisation was not available in Thesaurus, thus preventing a comprehensive assessment of the concordance of evidence rating amongst all the DIRs. In the BNF, evidence ratings were available for around one third of the DDIs, while they were consistently reported in Micromedex. In both DIRs, Theoretical was the most frequent category. However, the study revealed a lack of consistency between BNF and Micromedex, with no cases of strong agreement between any pairs of evidence ratings. An interesting observation was related to the DDIs included in one but missing from the other DIR, as the percentage of Not found DDIs in both cases increased as the evidence rating in the other DIR decreased. A study by Vitry that performed a similarity assessment of evidence ratings also highlighting inconsistencies in the grading system for evidence among the different sources. 8 In terms of clinical management recommendations, there was significant disagreement among the DIRs related to some types of advice, such as Use with caution, Wash‐out, Discontinue and Modify administration. Other types (i.e., Avoid and Use alternative) showed a moderate level of agreement, while Space dosing time, Monitor and Adjust dose demonstrated higher levels of concordance.

4.1. Impact on clinical decision support

Examples of missed medicines and DDIs from the different DIRs can be found in Table 5. Some ingredients were surprisingly missing from the DDI section of some of the DIRs, such as levetiracetam from Thesaurus and rupatadine from Micromedex. A few ingredients were not licensed in the respective countries (e.g., enalaprilat, an intravenous formulation of enalapril, is not available in the UK or France) or had been discontinued (e.g., ketorolac in France or maprotiline in the UK) at the time of data collection. Micromedex, however, contained drugs that were discontinued or not approved in the US.

TABLE 5.

Some examples of ingredients and drug–drug interactions not included in the drug–drug interaction sections of the three drug information resources

| Drug information resource | Ingredients | Drug–drug interactions |

|---|---|---|

| BNF |

Aprotinin Dextromethorphan Dibucaine Dimercaprol Filgrastim Flumazenil Goserelin |

Methylphenidate – Bupropion Rasagiline – Metoclopramide Bortezomib – Yellow fever vaccine Ephedrine – Midodrine Midostaurin – Lumacaftor Pentamidine – Domperidone Flecainide ‐ Propafenone |

| Thesaurus |

Abacavir Beclomethasone Dimercaprol Diphenoxylate Filgrastim Levetiracetam |

Ondansetron – Salmeterol Ondansetron – Sunitinib |

| Micromedex |

Adefovir Dalfampridine Daratumumab Mifamurtide Rupatadine Zoledronic acid |

Ephedrine – Moclobemide Tadalafil – Voriconazole |

The difference in size might also be partly related to the nature of the different DIRs. Micromedex is a commercial knowledge base, while BNF and Thesaurus are maintained by professional and regulatory bodies, respectively. Commercial knowledge bases may be overinclusive to minimise potential legal consequences arising from their decision to omit DDIs.

There were a few important DDIs missing from one of the three DIRs (Table 5). Examples include: voriconazole (a CYP3A4 inhibitor) interacting with tadalafil (a PDE‐5 inhibitor) by increasing its systemic exposure 28 ; bupropion and methylphenidate, indirect sympathomimetic agents that lower seizure threshold 29 ; and sunitinib and ondansetron, which both prolong the QT interval which predisposes to torsade de pointes. 30

Severity ratings also varied for DDIs in the three DIRs which may impact patient safety. For example, the combination of paroxetine and tramadol was categorised at the lowest severity level (Take into consideration) in Thesaurus while it was ranked as Severe and Major in the BNF and Micromedex, respectively. This is a complex interaction, which leads to decreased plasma concentrations of the active metabolite of tramadol (M1) because of CYP2D6 inhibition by paroxetine, and also an increased risk of serotonin syndrome. Interestingly, the updated version of Thesaurus (2020) has upgraded the severity level of the drug pair to Not recommended. Other examples include (a) the interaction between cytarabine and flucytosine, which was categorised as Severe in the BNF (because of decreased concentrations of flucytosine), but at the lowest level in both Micromedex and Thesaurus; (b) the interaction between niacin and statins, which increases the risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis, was characterised as Severe in the BNF and Major in Micromedex but was completely missing in Thesaurus; and (c) the combination of non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drugs with thiazide‐type diuretics (e.g., chlorothiazide, chlortalidone) was ranked as Severe in the BNF and Major in Micromedex (but as Precautions for use in Thesaurus) because of the risk of acute renal failure.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

As opposed to multiple previous efforts to assess the level of agreement among DIRs in terms of DDI information, this study examined entire resources, thus revealing the relative size of information in each of the DIRs and exploring the stratification of the included DDIs in terms of severity, evidence and clinical management recommendations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive effort to compare clinical advice for managing DDIs that is provided in multiple DIRs, with a clear focus on clinically oriented sources compared to previous work. 10 While a previous study expanded the comparison of DIRs at multiple levels (i.e., clinical drug, ingredient and drug class), 14 our analysis was limited to the ingredient level. This standardisation of DIRs enabled a “fair” comparison in terms of the volume of information listed. Also, code availability for data extraction and standardisation will enable reproducibility of the analysis.

However, there are limitations to this study. First, no updates have been taken into consideration since the date of data retrieval (i.e., offline data). Therefore, the results and conclusions of this study provide an overview of their similarity and consistency at that specific point in time, although no major updates usually occur. Second, Thesaurus contained a few DDIs originally reported at the drug class level, which were associated with multiple severity ratings. Hence, some standardised DDIs at the ingredient level were assigned more than one severity rating. In the BNF, there was a limited number of DDIs having multiple severity levels depending on the described clinical outcome. In both cases, the highest severity rating was considered for further analysis. Another limitation could be related to the different countries of origin for the DIRs that were considered in this study, which might have contributed to a small extent to the discrepancies observed. Other limitations include the comparison of clinical management options only for the DDIs present in the intersection of the DIRs and the custom‐made labelling process applied to Micromedex. Additionally, in the BNF, there were referrals to the guidance section of the website for various drug categories that were left unmapped during the annotation process, e.g., “For FSRH guidance, see contraceptives, interactions”, or “See ‘serotonin syndrome’ and ‘monoamine‐oxidase inhibitor’ under antidepressant drugs for more information and for specific advice on avoiding monoamine‐oxidase inhibitors during and after administration of other serotonergic drugs”. In this way, the overall advice support provided by the BNF might have been underestimated, although no concrete clinical advice was provided.

For future work, it would be interesting to evaluate a larger number of DIRs and include DIRs (e.g., Medscape, Lexicomp, Stockley's Drug Interactions) which could not be accessed in this instance due to lack of a subscription or due to terms and conditions that currently prohibit the type of analysis we have conducted. It would also be interesting to explore the completeness of generic DIRs as opposed to resources tailored to specific drug categories (e.g., the Liverpool Drug Interaction Checkers for anticancer drugs, etc.) that would be expected to provide more complete information. The evaluation of agreement on various types of DDI‐related information among DIRs from the same country of origin would be another relevant topic for future research, although significant levels of discordance would not be surprising, similar to previous studies. 14 Additionally, more comprehensive efforts to compare clinical management recommendations among entire resources would be beneficial from a clinical perspective.

4.3. Implications and conclusions

It is reasonable to assume that the inclusion of clinically significant DDIs in DIRs would improve drug efficacy and reduce adverse reactions. There is, however, a balance to strike since the value of these tools could be diminished if too many minor or clinically insignificant DDIs are included in an effort to limit legal liability. 31 This leads to the phenomenon of alert fatigue where practitioners ignore the alerts provided by the system due to the sheer volume of generated alerts, 32 with important clinical consequences for patient safety.

The Evidence workgroup from the DDI CDS Conference Series has highlighted the importance and need for higher‐quality information related to DDIs and also suggested the establishment of systematic DDI search criteria in order to determine the existing evidence related to the information provided. 33 Our analysis also shows the need for consistency in the definitions of severity and evidence ratings provided by the various DIRs. The availability of DDI evidence in a standardised format with adequate literature support, where possible, can improve prescribing decisions by allowing the prescriber to refer to appropriate resources and use clinical judgement in case of doubt.

The inclusion of clinical management options for DDIs in CDS tools is also quite important and especially useful in the clinical setting, as there is no single response to a potential DDI. More focus on this aspect has been suggested in multiple studies, which advocate more detailed and actionable advice (i.e., what and when to monitor) and clear indications of the strength of the recommendation. 34 , 35 We recommend that, by providing a dedicated section for clinical management recommendations that contains clear, actionable recommendations, information retrieval in the clinic can be facilitated, and potentially improve individualised risk–benefit assessment of a specific DDI. In cases where the benefits of a drug combination outweigh its risks, strategies to mitigate potential adverse outcomes (e.g., therapeutic drug monitoring, vital signs, discontinuation of one of the drugs, etc.) should be provided and will improve the benefit–harm balance of the drug combination. In the future, information about specific patient risk factors for DDIs, such as genetic polymorphisms, could also be included to enhance DDI preventability.

The use of pharmacologic drug classes in Thesaurus to summarise DDIs might become a source of confusion for clinicians. In many cases, individual drugs from a drug class have different pharmacological profiles (e.g., excretion, metabolism, etc.), which contribute to a markedly different DDI risk when considering the same interacting drug. 34 Consequently, drug ingredient indexing may paradoxically impede searching rather than achieve the aim of providing effective DDI summaries.

In conclusion, there is a great deal of interest in clinical decision support systems providing information on DDIs to optimise medicines use so that the use of drug combinations that affect either efficacy and/or safety can be avoided. However, there is a lack of consistency and standardisation in the information provided by different DIRs. Our study, which has systematically compared three DIRs, shows that there is considerable variation in the DDI information provided in these resources. Such variability in information could have deleterious consequences for patient safety, and there is a need for harmonisation and standardisation.

COMPETING INTERESTS

E.K. receives a PhD studentship that is jointly funded by AstraZeneca and the EPSRC. She also worked on a fixed‐term employment contract for AstraZeneca when this article was prepared. A.B. is an employee of Ceva Santé Animale. M.P. has received partnership funding for the following: MRC Clinical Pharmacology Training Scheme (co‐funded by MRC and Roche, UCB, Eli Lilly and Novartis); and grant funding from Vistagen Therapeutics. He also has unrestricted educational grant support for the UK Pharmacogenetics and Stratified Medicine Network from Bristol‐Myers Squibb and UCB. He has developed an HLA genotyping panel with MC Diagnostics, but does not benefit financially from this. M.P. is part of the IMI Consortium ARDAT (www.ardat.org). B.D. was AstraZeneca's employee and shareholder when this article was prepared but has since ended his relationship with both. S.M. has no conflict of interest to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

M.P., S.M. and E.K. conceived the work and designed the analysis. M.P., S.M., E.K. and B.D. contributed to data interpretation. E.K. conducted the data extraction, performed the analysis and drafted the original manuscript. A.B. contributed to data analysis. M.P., S.M. and B.D. provided critical feedback. All authors contributed to revising the paper and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1. An overview of drug–drug interaction online resources

Figure S2. Pipeline for clinical recommendation labelling

Figure S3. Similarity matrix of the Jaccard index for all drug information resource severity ratings

Table S1. Performance metrics and applied thresholds of the selected sentence classifiers for Micromedex descriptions.

Table S2. Evaluation of selected classifiers using an independent validation subset in terms of positive predictive value (PPV), sensitivity and F1‐score metrics (%).

Table S3. Number and percentage of drug–drug interactions included in the DIR intersection list by advice label for each drug information resource.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Ms Angela Hall from the Library and Knowledge Service at the Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust for facilitating access to Micromedex. The authors would like to acknowledge Antoni Wisniewski and Isobel Anderson for providing feedback on this research.

E.K. is funded for her PhD through joint funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) (Project Reference: EP/R51231X/1) and AstraZeneca.

Kontsioti E, Maskell S, Bensalem A, Dutta B, Pirmohamed M. Similarity and consistency assessment of three major online drug–drug interaction resources. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(9):4067‐4079. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15341

Funding information Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Grant/Award Number: EP/R51231X/1; AstraZeneca

Contributor Information

Elpida Kontsioti, Email: e.kontsioti@liverpool.ac.uk.

Munir Pirmohamed, Email: munirp@liverpool.ac.uk.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data from the DIRs were derived from the following web sources: the BNF website (https://bnf.nice.org.uk/interaction/, available in the public domain); ANSM website (https://ansm.sante.fr/documents/reference/thesaurus-des-interactions-medicamenteuses-1, available in the public domain). Restrictions apply to the availability of Micromedex data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available at https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ with the permission of IBM Watson Health. The code that supports the web data extraction and analysis are available at: https://github.com/elpidakon/CRESCENDDI.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital. BMJ. 2004;329(7463):15‐19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Egger SS, Drewe J, Schlienger RG. Potential drug–drug interactions in the medication of medical patients at hospital discharge. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;58(11):773‐778. doi: 10.1007/s00228-002-0557-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health and Social Care . Good for You, Good for Us, Good for Everybody: A Plan to Reduce Overprescribing to Make Patient Care Better and Safer, Support the NHS, and Reduce Carbon Emissions; 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1019475/good‐for‐you‐good‐for‐us‐good‐for‐everybody.pdf. Published September 22, 2021. Accessed April 3, 2022.

- 4. Magro L, Moretti U, Leone R. Epidemiology and characteristics of adverse drug reactions caused by drug–drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11(1):83‐94. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2012.631910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bjornsson TD, Callaghan JT, Einolf HJ, et al. The conduct of in vitro and in vivo drug–drug interaction studies: a Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) perspective. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(7):815‐832. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.7.815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Romagnoli KM, Nelson SD, Hines L, Empey P, Boyce RD, Hochheiser H. Information needs for making clinical recommendations about potential drug–drug interactions: a synthesis of literature review and interviews. BMC Medical Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17(1):1–9, 21. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0419-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hansten PD. Drug interaction management. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25(3):94‐97. doi: 10.1023/A:1024077018902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vitry AI. Comparative assessment of four drug interaction compendia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):709‐714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02809.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fulda TR, Valuck RJ, Vander ZJ, Parker S, Byrns PJ. Disagreement among drug compendia on inclusion and ratings of drug–drug interactions. Curr Ther Res. 2000;61(8):540‐548. doi: 10.1016/S0011-393X(00)80036-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ayvaz S, Horn J, Hassanzadeh O, et al. Toward a complete dataset of drug–drug interaction information from publicly available sources. J Biomed Inform. 2015;55:206‐217. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Phansalkar S, Desai AA, Bell D, et al. High‐priority drug–drug interactions for use in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(5):735‐743. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vonbach P, Dubied A, Krähenbühl S, Beer JH. Evaluation of frequently used drug interaction screening programs. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(4):367‐374. doi: 10.1007/s11096-008-9191-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang LM, Wong M, Lightwood JM, Cheng CM. Black box warning contraindicated comedications: concordance among three major drug interaction screening programs. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(1):28‐34. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fung KW, Kapusnik‐Uner J, Cunningham J, Higby‐Baker S, Bodenreider O. Comparison of three commercial knowledge bases for detection of drug–drug interactions in clinical decision support. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(4):806‐812. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . BNF: British National Formulary. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/. Published 2018. Updated February 25, 2022. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- 16. Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé . Thésaurus des interactions médicamenteuses. https://ansm.sante.fr/documents/reference/thesaurus-des-interactions-medicamenteuses-1. Published 2019. Accessed October 10, 2020.

- 17. IBM Watson Health . Micromedex® (electronic version). https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/. Published 2018.

- 18. Avery T. A brief insight into the BNF. Prescriber. 2008;19(10):7‐8. doi: 10.1002/psb.241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ogden J. The British National Formulary: past, present and future. Prescriber. 2017;28(12):20‐24. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aakre CA, Pencille LJ, Sorensen KJ, et al. Electronic knowledge resources and point‐of‐care learning: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2018;93(11S):S60‐S67. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roblek T, Vaupotic T, Mrhar A, Lainscak M. Drug–drug interaction software in clinical practice: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71(2):131‐142. doi: 10.1007/s00228-014-1786-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Python Software Foundation . Python Language Reference. https://docs.python.org/3.6/reference/. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- 23. Cossin S. IMthesaurusANSM: Thesaurus des Interactions Medicamenteuses de l'ANSM. https://rdrr.io/github/scossin/IMthesaurusANSM/. Published 2016. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- 24. Nelson SJ, Zeng K, Kilbourne J, Powell T, Moore R. Normalized names for clinical drugs: RxNorm at 6 years. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(4):441‐448. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. RxNorm Extension: an OHDSI resource to represent international drugs. https://www.ohdsi.org/web/wiki/doku.php?id=documentation:international_drugs. Accessed February 26, 2020.

- 26. OHDSI Team . Usagi: an application to help create mappings between coding systems and the Vocabulary standard concepts. http://ohdsi.github.io/Usagi/. Published 2020. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- 27. Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). http://www.nltk.org/. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- 28. Corona G, Razzoli E, Forti G, Maggi M. The use of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors with concomitant medications. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31(9):799‐808. doi: 10.1007/BF03349261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baird R, Ickowicz A. Methylphenidate and the cytochrome P450 system [2] (multiple letters). Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(6):425‐426. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kollmannsberger C, Bjarnason G, Burnett P, et al. Sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: recommendations for management of noncardiovascular toxicities. The Oncologist. 2011;16(5):543‐553. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greenberg M, Ridgely MS. Clinical decision support and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2011;306(1):90‐91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Phansalkar S, van der Sijs H, Tucker AD, et al. Drug–drug interactions that should be noninterruptive in order to reduce alert fatigue in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(3):489‐493. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Scheife RT, Hines LE, Boyce RD, et al. Consensus recommendations for systematic evaluation of drug–drug interaction evidence for clinical decision support. Drug Saf. 2015;38(2):197‐206. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0262-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Horn JR, Gumpper KF, Hardy JC, McDonnell PJ, Phansalkar S, Reilly C. Clinical decision support for drug–drug interactions: improvement needed. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(10):905‐909. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tilson H, Hines LE, McEvoy G, et al. Recommendations for selecting drug–drug interactions for clinical decision support. Am J Heal Pharm. 2016;73(8):576‐585. doi: 10.2146/ajhp150565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. An overview of drug–drug interaction online resources

Figure S2. Pipeline for clinical recommendation labelling

Figure S3. Similarity matrix of the Jaccard index for all drug information resource severity ratings

Table S1. Performance metrics and applied thresholds of the selected sentence classifiers for Micromedex descriptions.

Table S2. Evaluation of selected classifiers using an independent validation subset in terms of positive predictive value (PPV), sensitivity and F1‐score metrics (%).

Table S3. Number and percentage of drug–drug interactions included in the DIR intersection list by advice label for each drug information resource.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the DIRs were derived from the following web sources: the BNF website (https://bnf.nice.org.uk/interaction/, available in the public domain); ANSM website (https://ansm.sante.fr/documents/reference/thesaurus-des-interactions-medicamenteuses-1, available in the public domain). Restrictions apply to the availability of Micromedex data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available at https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ with the permission of IBM Watson Health. The code that supports the web data extraction and analysis are available at: https://github.com/elpidakon/CRESCENDDI.